Executed October 9, 2013 7:11 p.m. CDT by Lethal Injection in Texas

30th murderer executed in U.S. in 2013

1350th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

14th murderer executed in Texas in 2013

506th murderer executed in Texas since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(30) |

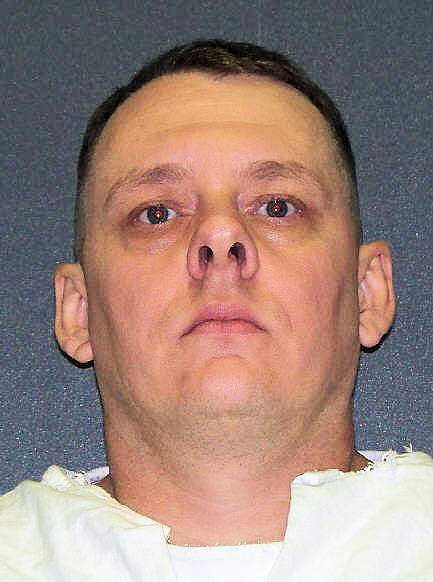

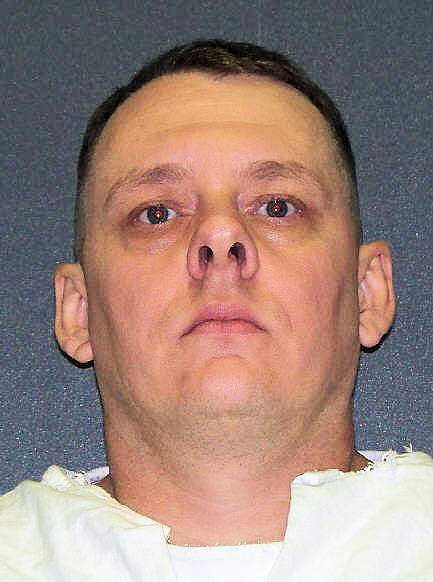

Michael John Yowell W / M / 29 - 43 |

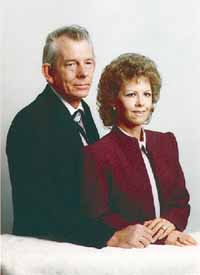

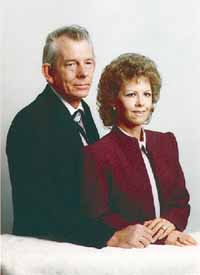

Johnny Yowell W / M / 55 Carol Nichols W / F / 53 Viola Davis W / F / 89 |

Strangulation With Cord Gas Explosion |

Mother Grandmother |

Citations:

Yowell v. Thaler, 442 Fed. Appx. 100 (5th Cir. Tex. 2011). (Federal Habeas)

Yowell v. Thaler, 2013 U.S. App. LEXIS 7663 (5th Cir. Tex. Apr. 16, 2013). (Federal Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

Texas no longer offers a special "last meal" to condemned inmates. Instead, the inmate is offered the same meal served to the rest of the unit.

Final/Last Words:

“I love you. To Gerald, you’re a zero. I love you Mandy. Tiffany, I love you, too. Punch the button."

Internet Sources:

Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Executed Offenders

Yowell, Michael J.

Date of Birth: 01/25/1970

DR#: 999334

Date Received: 11/23/1999

Education: 12 years

Occupation: Steel Fabrication, Cook, Laborer

Date of Offense: 05/09/1998

County of Offense: Lubbock

Native County: Lubbock

Race: White

Gender: Male

Hair Color: Brown

Eye Color: Hazel

Height: 5' 09"

Weight: 188

Prior Prison Record: #505775, 8-year sentence for 1 count of Possession of a Controlled Substance; 06/16/89 released on Pre-Parole; 09/19/89 release on Parole; 02/22/97 received Clemency Discharge.

Summary of Incident: On 05/19/98 in Lubbock, Texas, Yowell shot his father, strangled his mother with a cord, and set fire to their house. The victim's grandmother died several days later from injuries sustained because she was disabled and unable to get out of the house. Co-Defendants: None.

Wednesday, October 2, 2013

Media Advisory: Michael Yowell scheduled for execution

AUSTIN – Pursuant to a court order by the 140th District Court of Lubbock County, Texas, Michael John Yowell is scheduled for execution after 6 p.m. on Wednesday, Oct. 9, 2013. On Oct. 4, 1999, a Lubbock County jury convicted Yowell of the capital murder of his parents, Johnny and Carol Yowell. Following two days of punishment phase proceedings, on Oct. 6, 1999, the convicting court sentenced Yowell to death.

FACTS OF THE CRIME

The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit described the murders of Johnny and Carol Yowell as follows: In 1998, Yowell shot and killed his father, strangled his mother, and opened a natural gas line in the kitchen. When his grandmother, who was living in his parents’ house at the time, opened her bedroom door, it caused the gas to combust, fatally injuring his grandmother and charring the remains of his parents. Two days later, Yowell confessed to shooting his father, who had caught Yowell trying to steal his wallet to buy drugs, and to struggling with his mother before bludgeoning her and strangling her. Yowell said that afterwards, in a panic, he ran to the kitchen and opened a gas jet.

PRIOR CRIMINAL HISTORY

Under Texas law, the rules of evidence prevent certain prior criminal acts from being presented to a jury during the guilt-innocence phase of the trial. However, once a defendant is found guilty, jurors are presented information about the defendant’s prior criminal conduct during the second phase of the trial – which is when they determine the defendant’s punishment.

During the punishment phase of Yowell’s capital murder trial, the prosecution presented evidence establishing Yowell’s felony convictions for burglary of a building and possession of a controlled substance. Yowell’s probation officer testified that Yowell was released from prison to a halfway house, had attempted various programs over the years for drug treatment and mental disorders, and had been recently reported to be in violation of the terms of his parole based on new offenses in March 1998 (two months before the capital offense) including forgery, stolen checks, and illegal use of credit cards. The jurors also learned that Yowell, a convicted felon, had used his mother’s credit card to purchase prohibited firearms from three different stores and falsified information in order to purchase or pawn the weapons. Finally, five days before the capital crime, Yowell signed a statement admitting that he stole from his mother by forging checks and illegally used her credit cards.

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

On July 23, 1998, a Lubbock County grand jury indicted Yowell for the May 9, 1998, Mother's Day weekend capital murder of Johnny and Carol Yowell. Yowell was also charged with the felony murder of his grandmother, Viola Davis.

On Oct. 4, 1999, a Lubbock County jury convicted Yowell of capital murder for having intentionally and knowingly shot his father to death during the same criminal episode in which he strangled his mother with an electrical cord.

Following a separate punishment hearing, on Oct. 6, 1999, the jury answered affirmatively the special sentencing issue on future dangerousness and answered negatively the issue on mitigation. In accordance with the jury’s answers, the trial court sentenced Yowell to death.

On Feb. 13, 2002, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed on direct appeal.

On July 25, 2001, Yowell filed a state habeas corpus application raising 10 claims.

On March 13, 2005, the trial court commenced an evidentiary hearing on Yowell’s claims.

On Nov. 22, 2006, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals denied habeas corpus relief.

On Sept. 10, 2007, Yowell filed a federal habeas petition.

On Aug. 26, 2010, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas conditionally granted punishment-phase relief for a claim of ineffective assistance of counsel, declined to rule on two claims, and denied the remaining claims for lack of merit. Final judgment was issued the same day vacating Yowell’s sentence and remanding for re-sentencing or imposition of a life sentence.

On Sept. 12, 2011, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit reversed the grant of habeas corpus relief and remanded the case for consideration of the two pretermitted claims.

On remand, on Oct. 3, 2012, the federal district court denied both claims on the merits, dismissed Yowell’s habeas petition with prejudice, denied Yowell a certificate of appealability (COA), and entered final judgment.

On April 16, 2013, the Fifth Circuit court denied Yowell a certificate of appealability.

On July 12, 2013, Yowell petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court for certiorari review.

On October 1, 2013, attorneys for Michael Yowell, and two other death row inmates, Thomas Whitaker and Perry Williams, filed a class action lawsuit in Houston U.S. district court, challenging the constitutionality of Texas' execution protocol.

On October 5, 2013, a U.S. Houston U.S. district court denied a stay of execution.

On October 7, 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court denied Yowell's petition for certiorari review.

On Oct. 8, 2013, Yowell filed an appeal in the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, asking that his execution be stayed pending adjudication of the means the state plans to use to carry out his execution.

On Oct. 8, 2013,the Fifth Circuit court affirmed the injunctive relief and denied Yowell’s a stay.

On Oct. 9, 2013, Yowell petitioned the Fifth Circuit court for certiorari review and a stay of execution.

Texas Execution Information Center by David Carson.

Michael John Yowell, 43, was executed by lethal injection on 9 October 2013 in Huntsville, Texas for the murder of his parents and grandmother in their home.

On 19 May 1998, Yowell, then 28, was in his parents' house in Lubbock. Yowell's father, Johnny, 55, caught him trying to steal money from his wallet. Yowell then fatally shot his father. He then beat his mother, Carol, 53, and strangled her with an electrical cord. He then opened a natural gas line in the kitchen and fled. Yowell's 89-year-old grandmother, Viola Davis, who was living in the home at the time, was disabled and was unable to get out of the home. She was injured when the house exploded. She died from her injuries several days later.

Yowell confessed to the crime two days later. He said he was stealing from his father to support his $200-a-day drug habit. He admitted killing his parents and opening the gas jet. The gun was found in the crawl space of his friend's house.

At trial, the defense argued that Yowell was insane at the time of the offense and was unaware that killing his parents was wrong. His lawyers put a psychologist, Philip Davis, on the witness stand to read Yowell's extensive history of psychological treatment and his treatment for drug addiction. Yowell's attorneys did not allow Davis to personally examine Yowell, for that would have invited the state to conduct an examination with one of their own expert witnesses.

Yowell had previous convictions for burglary of a building and possession of a controlled substance for separate 1988 offenses. He was first sentenced to 10 years' probation on the burglary conviction. He was subsequently sentenced to 8 years in prison on the drug conviction. He served 4 months of that sentence in 1989, then was released on parole. (At the time, early release was common in Texas due to strict prison population caps imposed by U.S. District Judge William Wayne Justice.) Yowell had also stolen from his mother by forging checks and illegally using her credit cards. He purchased firearms from stores using falsified information and his mother's credit cards and then pawned them for cash.

After the state presented its evidence for the punishment phase of the trial, Yowell's attorney announced that the defense would not offer any mitigating evidence, because Yowell had instructed him not to. The attorney told the court that Yowell told him "he doesn't want us to take any action that would result in the possibility of a life sentence. He wants a death sentence."

The judge advised Yowell to allow his lawyers to defend him, but Yowell said he disagreed with his attorney's plan to play his recorded confession again. The judge decided to allow the attorney to present his defense. The attorney then played Yowell's confession and asked the jury to impose a 40-year sentence in prison in light of the "genuine remorse" Yowell expressed in the recording.

A jury found Yowell guilty of capital murder in October 1999 and sentenced him to death. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the conviction and sentence in February 2002.

In August 2010, a federal district court vacated Yowell's death sentence based on his claim that his attorney's performance during the punishment phase of his trial was ineffective. While the attorney did present evidence giving a sympathetic depiction of Yowell during the guilt/innocence phase of the trial, that evidence was not presented again during the punishment phase. The U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed this decision in September 2011, however. The appeals court found that all of the evidence Yowell had wanted the attorney to present was presented during the guilt/innocence phase, and it was not necessary to present it again during the punishment phase. All of Yowell's other appeals in state and federal court were denied.

Yowell expressed love to his family at his execution. He then told the warden, "Punch the button." The lethal injection was then started. He was pronounced dead at 7:11 p.m.

"Michael Yowell Executed For Killing Parents In Texas," by Michael Graczyk. (AP 10/09/13 08:24 PM ET EDT)

HUNTSVILLE, Texas -- HUNTSVILLE, Texas (AP) — A Texas man was put to death Wednesday evening for killing his parents at their Lubbock home 15 years ago during a drug-influenced rampage that also left his 89-year-old grandmother dead. Michael Yowell, 43, told witnesses, including his daughters and his ex-wife, that he loved them. "Punch the button," he told the warden. He took several deep breaths, then began snoring. Within about 30 seconds, all movement stopped. He was pronounced dead 19 minutes later at 7:11 p.m. CDT.

Yowell tried to delay his execution, the 14th this year in the nation's most active death penalty state, by joining a lawsuit with two other condemned prisoners that challenged Texas prison officials' recent purchase of a new supply of pentobarbital for his scheduled lethal injection. The U.S. Supreme Court rejected the appeal minutes before Yowell was taken to the Texas death chamber Wednesday evening.

The prisoners argued use of the sedative could cause unconstitutional pain and suffering because the drug, replacing a similar inventory that expired at the end of September, was made by a compounding pharmacy not subjected to strict federal scrutiny. Texas, like other death penalty states, has turned to compounding pharmacies that custom-make drugs for customers after traditional suppliers declined to sell to prison agencies or bowed to pressure from execution opponents.

The lawsuit sought an injunction to delay the execution and gain more time to ensure "the integrity and legality" of the drug and be certain its use was within constitutional protections. Attorneys for the inmates took the case to the U.S. Supreme Court after lower federal courts ruled that the drug appeared adequate and that the Texas Department of Criminal Justice did nothing wrong in acquiring it. "Our baseline contention is we, the public, have to be concerned about transparency and accountability by a state agency that's carrying out the gravest of all possible duties," Maurie Levin, one of the inmates' attorneys, said.

Yowell's parents, John, 55, and Carol, 53, were found dead in the wreckage of their home following an explosion on Mother's Day weekend in 1998. Yowell's 89-year-old grandmother, Viola Davis, who was staying there, died days later of injuries suffered in the blast. Yowell already was on probation for burglary and drug convictions. He was arrested on federal firearms charges and charged with his parents' slayings after authorities determined his mother had been beaten and strangled and his father was shot. Prosecutors showed John Yowell was killed when he caught his son stealing his wallet. Yowell then attacked his mother, opened a gas valve and fled. The home blew up.

"At some point he's looking his mom in the face, beating her and wrapping a lamp cord around her neck," Lubbock County District Attorney Matt Powell, who prosecuted the case, recalled Tuesday. "I think always there are some unanswered questions. You want to know how somebody is capable of doing that to their parents." Evidence showed Yowell had a $200-a-day drug habit he supported by stealing. Evidence also showed he burned some of his bloody clothes and hid a blood-stained jacket and the murder weapon in the crawl space of a friend's house. Defense attorneys unsuccessfully tried to show Yowell was insane. On Monday, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to review appeals that contended Yowell received shoddy legal help at his 1999 trial and in the early stages of his appeals.

"Yowell tells executioner: 'Punch the button'; Lubbock man convicted of murdering his parents executed Wednesday in Huntsville," by Walt Nett. (October 9, 2013)

HUNTSVILLE — Michael Yowell, who killed his parents more than 15 years ago while trying to steal money from his father to buy drugs, died by lethal injection at 7:11 p.m., Wednesday, Oct. 9. He made a brief last statement: “I love you. To Gerald, you’re a zero. I love you Mandy; Tiffany, I love you, too.” He paused for a moment, then said: “Punch the button. We are ready.” Yowell, 43, was the 14th inmate the state of Texas has executed this year, and the second from Lubbock County.

Mandy and Tiffany referred to his daughters, who attended the execution. Gerald may have been in reference to a witness, Gerald Harder, who attended the execution with the daughters and Yowell’s ex-wife, Amanda Weathers.

Yowell was taken from a holding cell at 6:42 p.m., shortly after the U.S. Supreme Court rejected one final attempt to block the execution pending the outcome of a lawsuit filed last week challenging the state prison system’s use of the drug pentobarbital obtained from a compounding pharmacy. Yowell and two other prisoners argued use of the sedative could cause unconstitutional pain and suffering because the drug, replacing a similar inventory that expired at the end of September, was made by a compounding pharmacy not subjected to strict federal scrutiny. Texas, like other death penalty states, has turned to compounding pharmacies that custom-make drugs for customers after traditional suppliers declined to sell to prison agencies or bowed to pressure from execution opponents.

The lethal dose of pentobarbital, also known as Nembutal, was injected into the intravenous catheters at 6:52 p.m. Shortly after that, Yowell appeared to struggle for breath several times before settling into sleep, inhaling and snoring eight times before his audible breathing stopped. Yowell, 43, became pale. A prison physician checked for pulse and breathing and made the pronouncement of death.

Yowell’s reaction to the drug was similar to the 23 other Texas inmates put to death since last year when the state began using pentobarbital as the lone lethal drug for executions. Yowell’s lawyers said the execution was a disappointment and characterized the use of compounded drugs as “a dramatic change from prior practice — making the need for oversight, now and in the future — that much more important.” “Surely this is not the way we want our government to carry out its most solemn duty,” Maurie Levin and Bobbie Stratton said in a statement. Yowell was convicted in 1999 of killing his parents, John and Carol Yowell. No witnesses attended on their behalf.

He told investigators he initially planned to take a few cigarettes when he entered his parents’ bedroom early on the morning of May 9, 1998 — the day before Mother’s Day. He shot his father in the head, then beat his mother before strangling her with a lamp cord.

Yowell already was on probation for burglary and drug convictions. He was arrested on federal firearms charges and charged with his parents’ slayings after authorities determined his mother had been beaten and strangled and his father was shot. “At some point he’s looking his mom in the face, beating her and wrapping a lamp cord around her neck,” Lubbock County District Attorney Matt Powell, who prosecuted the case, recalled Tuesday. “I think always there are some unanswered questions. You want to know how somebody is capable of doing that to their parents.”

Evidence showed Yowell had a $200-a-day drug habit he supported by stealing. Evidence also showed he burned some of his bloody clothes and hid a blood-stained jacket and the murder weapon in the crawl space of a friend’s house. Defense attorneys unsuccessfully tried to show Yowell was insane. After murdering his parents, Yowell then shut his grandmother, Viola Davis, in her bedroom before going to the kitchen and opening a gas jet. The house later exploded, and Davis was fatally injured, dying 12 days later of burns and complications from smoke inhalation.

The execution drew national attention because of the lawsuit over buying pentobarbital from a compounding pharmacy. Compounding pharmacies are not regulated by the federal Food and Drug Administration, a situation that has prompted concerns about the possibility the drugs might be less effective. Texas and other states that use pentobarbital as the execution drug have looked for other sources after the drug’s Danish manufacturer ceased selling it to U.S. prisons for use as an execution drug.

According to a death watch timetable distributed by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, Yowell spent his final days talking with friends, his ex-wife and his daughters. His breakfast, served shortly after 3 a.m., was fried eggs, country gravy, cereal and applesauce. He took photographs with his daughters and friends who visited in the morning.

"Texas executes Lubbock man who killed parents," by Michael Graczyk. (AP Wed Oct 09, 2013, 10:24 PM CDT)

HUNTSVILLE — A Texas man was put to death Wednesday evening for killing his parents at their Lubbock home 15 years ago during a drug-influenced rampage that also left his 89-year-old grandmother dead. Michael Yowell, 43, told witnesses, including his daughters and his ex-wife, that he loved them. “Punch the button,” he told the warden. He took several deep breaths, then began snoring. Within about 30 seconds, all movement stopped. His daughters and ex-wife hugged as they watched through a window in the death chamber. Yowell was pronounced dead 19 minutes later at 7:11 p.m. CDT.

Yowell tried to delay his execution, the 14th this year in the nation’s most active death penalty state, by joining a lawsuit with two other condemned prisoners that challenged Texas prison officials’ recent purchase of a new supply of pentobarbital for his scheduled lethal injection. The punishment was delayed briefly until the U.S. Supreme Court, in a brief ruling, rejected the appeal. The prisoners argued use of the sedative could cause unconstitutional pain and suffering because the drug, replacing a similar inventory that expired at the end of September, was made by a compounding pharmacy not subjected to strict federal scrutiny. Texas, like other death penalty states, has turned to compounding pharmacies that custom-make drugs for customers after traditional suppliers declined to sell to prison agencies or bowed to pressure from execution opponents. The lawsuit sought an injunction to delay the execution and gain more time to ensure “the integrity and legality” of the drug and be certain its use was within constitutional protections.

Attorneys for the inmates took the case to the U.S. Supreme Court after lower federal courts ruled that the drug appeared adequate and that the Texas Department of Criminal Justice did nothing wrong in acquiring it. Yowell’s reaction to the drug was similar to the 23 other Texas inmates put to death since last year when the state began using pentobarbital as the lone lethal drug for executions. Yowell’s lawyers said the execution was a disappointment and characterized the use of compounded drugs as “a dramatic change from prior practice — making the need for oversight, now and in the future — that much more important.” “Surely this is not the way we want our government to carry out its most solemn duty,” Maurie Levin and Bobbie Stratton said in a statement.

Yowell’s parents, John, 55, and Carol, 53, were found dead in the wreckage of their home following an explosion on Mother’s Day weekend in 1998. Yowell’s 89-year-old grandmother, Viola Davis, who was staying there, died days later of injuries suffered in the blast. Yowell already was on probation for burglary and drug convictions. He was arrested on federal firearms charges and charged with his parents’ slayings after authorities determined his mother had been beaten and strangled and his father was shot.

Prosecutors showed John Yowell was killed when he caught his son stealing his wallet. Yowell then attacked his mother, opened a gas valve and fled. The home blew up. “At some point he’s looking his mom in the face, beating her and wrapping a lamp cord around her neck,” Lubbock County District Attorney Matt Powell, who prosecuted the case, recalled Tuesday. “I think always there are some unanswered questions. You want to know how somebody is capable of doing that to their parents.”

Evidence showed Yowell had a $200-a-day drug habit he supported by stealing. Evidence also showed he burned some of his bloody clothes and hid a blood-stained jacket and the murder weapon in the crawl space of a friend’s house. Defense attorneys unsuccessfully tried to show Yowell was insane. On Monday, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to review appeals that contended Yowell received shoddy legal help at his 1999 trial and in the early stages of his appeals.

In 1998, after being caught trying to steal money to buy drugs, Michael John Yowell shot and killed his father, strangled his mother, and opened a natural gas line in the kitchen. When his grandmother, who was disabled, opened her bedroom door, it caused the gas to combust, injuring his grandmother and charring the remains of his parents. His grandmother died several days later from her injuries.

Two days after the murders, Yowell confessed to shooting his father, who had caught Yowell trying to steal his wallet to buy drugs, and to struggling with his mother before bludgeoning her and strangling her to death. Yowell said that afterwards, in a panic, he ran to the kitchen and opened a gas jet. He told investigators he initially planned to take a few cigarettes when he entered his parents’ bedroom early on the morning of May 9, 1998 — the day before Mother’s Day. Then he saw his father's wallet and tried to grab it, waking his mother. He claimed that when she grabbed his arm, the gun in his pocket went off and struck his father. He told investigators that he did not recall what he had done to his mother but he remembered hearing her gurgle. Police believe that after he shot his father in the head, he intended to shoot his mother but the gun malfunctioned. Instead he beat his mother before strangling her with a lamp cord.

Yowell already was on probation for burglary and drug convictions. He was arrested on federal firearms charges and charged with his parents’ slayings after authorities determined his mother had been beaten and strangled and his father was shot. “At some point he’s looking his mom in the face, beating her and wrapping a lamp cord around her neck,” Lubbock County District Attorney Matt Powell, who prosecuted the case, recalled just before the execution. “I think always there are some unanswered questions. You want to know how somebody is capable of doing that to their parents.”

Evidence showed Yowell had a $200-a-day drug habit he supported by stealing. Evidence also showed he burned some of his bloody clothes and hid a blood-stained jacket and the murder weapon in the crawl space of a friend’s house. Defense attorneys unsuccessfully tried to show Yowell was insane. After murdering his parents, Yowell then shut his grandmother, Viola Davis, who owned the home, in her bedroom before going to the kitchen and opening a gas jet. The house later exploded, blowing out one wall and buckling others and collapsing the roof. Neighbors Charles McMillan and Greg Songer charged into the rubble and pulled Viola Davis out. She would die a dozen days later in a hospital from burns and injuries she received in the blast. Two other bodies, burned beyond recognition, were removed from the ruins — John Yowell’s body so badly burned that, according to reports in the Avalanche-Journal, his gender wasn’t readily apparent.

Police weren’t sure who they were at that point, but neighbors insisted the pair were John and Carol Yowell. John was 55 years old, his wife, two years younger. An autopsy would find a bullet wound in John Yowell’s head. Carol Yowell was Viola’s daughter and her body was found face down, a lamp cord around her neck and the lamp on her back. When Michael John Yowell, then 28 years old, went on trial in September 1999 for the double murder, prosecutor Matt Powell told the jury that 2114 39th St. “looked like a war zone.”

At the time of the incident, Yowell was nowhere to be found. Two days later, he approached the police at the wreckage of the house and was arrested on a federal warrant of being a felon in possession of a firearm. After the guilt phase of the trial, the jury took only 45 minutes to find Yowell guilty and Yowell told his attorneys not to present a case in the punishment phase. The judge refused this edict and the defense argued against the death penalty, however the jury returned a death sentence in two and a half hours.

UPDATE: More than 15 years after murdering his parents and grandmother, a man was executed in Texas. Prior to his execution, Michael Yowel, 43, made a brief last statement, saying, “I love you. To Gerald, you’re a zero. I love you Mandy; Tiffany, I love you, too.” He paused for a moment, then said: “Punch the button. We are ready.” Mandy and Tiffany referred to his daughters, who attended the execution. Gerald may have been in reference to a witness, Gerald Harder, who attended the execution with the daughters and Yowell’s ex-wife, Amanda Weathers. According to the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, Yowell spent his final days talking with friends, his ex-wife and his daughters. ,

Yowell v. Thaler, 442 Fed. Appx. 100 (5th Cir. Tex. 2011). (Federal Habeas)

PROCEDURAL POSTURE: Respondent state appealed from the judgment of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas, which granted habeas corpus relief to petitioner under 28 U.S.C.S. § 2254.

OVERVIEW: The district court failed to give sufficient Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 deference to the state court's factual finding that petitioner's proferred mitigation evidence was cumulative. The state court conducted a lengthy evidentiary hearing on the matter and determined that even if the additional evidence had been introduced during the punishment phase, it was not significant in light of its similarity to the other evidence the defense had already presented during the guilt/innocence phase. Because the defense had introduced mitigating evidence during trial, the court had to assume, as the state habeas court did, that the jury considered it during the punishment phase, especially in light of the fact that petitioner's attorney referred to the medical records during his closing statement. The court deferred to the state habeas court's determination that petitioner had failed to show the necessary prejudice under Washington, and the court reversed the habeas relief on petitioner's claim of ineffective assistance.

OUTCOME: The judgment of the district court was reversed and remanded for the district court to address only the pretermitted issues.

JERRY E. SMITH Circuit Judge:

The state appeals a judgment granting habeas corpus relief to Michael Yowell under 28 U.S.C. § 2254. Because the district court did not sufficiently defer to the state habeas court's findings, we reverse and remand.

I.

In 1998, Yowell shot and killed his father, strangled his mother, and opened a natural gas line in the kitchen. When his grandmother, who was living in his parents' house at the time, opened her bedroom door, it caused the gas to combust, fatally injuring his grandmother and charring the remains of his parents. Two days later, Yowell confessed to shooting his father, who had caught Yowell trying to steal his wallet to buy drugs, and to struggling with his mother before bludgeoning her and strangling her to death. Yowell said that afterwards, in a panic, he ran to the kitchen and opened a gas jet.

II.

Yowell was charged with capital murder. At trial, his attorney argued that he was "legally insane" at the time of the offense and unaware that his conduct was wrong. The lawyer relied on Yowell's extensive medical record that documented, in over 800 pages spanning many years, Yowell's ongoing mental illness, psychiatric problems, drug and chemical dependency, self-medication, suicidal and homicidal ideation, and criminal activity. Philip Davis, a psychologist, testified for the defense for approximately two hours about Yowell's mental health records. He read entries from the records describing that, inter alia,

• Yowell was a patient at Lubbock Regional Mental Health Mental Retardation Center as early as 1988 when he sought treatment for drug addiction;

• he was neglected as a child and had violent thoughts;

• he attempted suicide in 1991;

• he was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder, bipolar disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and schizoid and sadistic personality disorder traits;

• he was diagnosed as suicidal and with polysubstance dependence based on his using cocaine, methamphetamine, acid, LSD, marihuana, beer, liquor, and prescription Darvon, Demerol, and Dysoxin; by 1992, he was hospitalized at Big Spring State Hospital, where he experienced long periods of depression, brief periods of manic bizarre behavior, and some delusional thinking;

• beginning in 1993, doctors diagnosed him with antisocial personality disorder;

• he had serious thoughts of committing homicide and tried to collect money by beating someone with a bat;

• he reported having blackouts, daydreaming about abusing his then one-year-old and three-year-old daughters, and fantasizing about sexually molesting children and committing mass murder;

• he had two years of sobriety from 1994 to 1996, but the suicidal thoughts and mental health problems returned;

• he reported having racing thoughts, extreme anger, potential for violence, and hearing voices telling him to hurt others; and

• he was hospitalized in 1997 and 1998 for polysubstance abuse, drug-induced psychosis, and bipolar disorder.

Although Davis testified at length regarding what was in Yowell's records, he was not allowed to give his own opinions or interpretations, because he had not personally examined Yowell, nor had he been designated as such a witness by Yowell. 1 At the conclusion of Davis's testimony, the defense rested.

1 That was a strategic decision. One of Yowell's attorneys stated to the trial court, "Based on my experience in the past, there's probably no way on God's green earth that we're going to do anything to allow the State to examine our client with one of their own experts. If that's an indication of what our intent is, then so be it."

The jury found Yowell guilty of capital murder, then the trial moved to the punishment phase. 2 Before beginning its case, the defense informed the court that "we're going to rest. We're not going to call anybody." Outside the jury's presence, Yowell's attorney stated that he needed to "put something on the record," and informed the court that [d]uring the recess, while the Court was revising the Court's Charge, I had a consultation with my client. And he has instructed me, Your Honor, not to argue the case. I intend to go ahead and do it. But I wanted to make sure that he had an opportunity to tell the Court that.

Following that representation, the court admonished Yowell that he should follow his attorney's advice. Yowell replied, Judge, sir, the way they are going about it is the way that—it's not to argue my case. I don't want the argument in the context of the way that they want to argue it, which is playing [my recorded confession]. . . . I see no point in going over something that's, to me, in my own words, as brutal as what went on. Having those people hear that again is not going to help me in any way. The court told Yowell it would take a brief recess for Yowell to confer with his attorneys.

2 In Texas, capital murder cases are tried under a bifurcated model separating the guilt/innocence phase from the punishment phase. Tex. Code Crim. Proc. Ann. art. 37.071 § 2(a)(1) (Vernon 2006).

After the recess, but before Yowell returned to the courtroom, the defense informed the court: I don't know if this needs to be on the record since [Yowell is] not here. He has told me—or us, in no uncertain terms, that he doesn't want us to take any action that would result in the possibility of a life sentence. He wants a death sentence. The attorney further stated that he planned to "go ahead, and argue the case, whether [Yowell] wants me to or not. I don't think I have much choice." The court agreed.

The defense proceeded to play the hour-long tape recording of Yowell's confession for the jury, then argued as follows: It was necessary that I play the entire tape for you so that people won't think we were taking things out of context. And it's taken my entire time. But I thought it was important to show each of you that I think there is some genuine remorse on the behalf of [Yowell] in this case. Between that evidence, the evidence of the medical records and the background, I think, I think that that's sufficient cause to step back, to take that one step back from the death penalty. Forty years is plenty. Forty years maximum. And I'm asking you to step back. The jury sentenced Yowell to death.

After exhausting his direct appeals, Yowell applied for a state writ of habeas corpus raising ten claims, one of which was ineffective assistance of counsel regarding the punishment phase. He alleged that his counsel "ineffectively failed to investigate and present compelling mitigation evidence at the punishment stage in an effort to convince the jury to impose a life sentence rather than a death sentence." He denied that he had ever told his attorneys to accept the death penalty and argued that they should have pursued and presented "more compelling" evidence in the medical health records and from other sources, such as the testimony of friends and family.

Yowell supported the claim with affidavits from a defense investigator and nine witnesses. Yowell said that his attorneys should have elicited evidence from those individuals that, inter alia, his father was a workaholic and an alcoholic gambler who abused his children and his wife; that Yowell loved his mother; that he was a drug abuser; and that his older brother was domineering, physically abusive, and perhaps sexually-abusive. Yowell also alleged that the jury did not understand the mitigating effect of the mental health records, because Davis was not allowed to interpret them.

The state habeas trial court conducted an evidentiary hearing and considered all the evidence. It determined that, under Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 104 S. Ct. 2052, 80 L. Ed. 2d 674 (1984), Yowell had failed to show both that his counsel's performance was objectively deficient and that, even if it was deficient, it prejudiced his defense. The state court found that his attorneys' investigation was "reasonable and thorough" and that the defense had presented a sympathetic picture of Yowell's background during the guilt/innocence stage through the medical records. The court also found that counsel "were instructed by [Yowell] not to take any action that would result in the possibility of a life sentence as [Yowell] wanted a death sentence."

The court concluded that the attorneys had "performed competently and provided constitutionally effective assistance" and that Yowell had failed to prove sufficient prejudice: [Yowell] contends that trial counsel should have elicited potential mitigating evidence. . . . [However Yowell's] attorneys did investigate and put on evidence concerning [Yowell's] background. Trial counsel established [Yowell]'s abused childhood and drug usage through the introduction of voluminous records—more than [800] pages. In addition, these records were highlighted to the jury for approximately two hours in live testimony. This evidence addressed [Yowell]'s home environment and drug usage in voluminous detail. Additionally, the evidence addressed most, if not all, of [Yowell]'s contentions concerning his home life. Consequently, [Yowell] is unable to show that, if the newly profferred mitigation evidence had been presented, that there is a reasonable probability the result of the sentencing phase would have been different.

Moreover, after reviewing the complained-of additional mitigation evidence presented in the Application for Writ of Habeas Corpus, testimony at the writ hearing, and supporting affidavits, this Court concludes that the additional mitigation evidence is not significant due to the similarity to evidence introduced at trial. After evaluating the totality of the available mitigation evidence—both that adduced at trial and the evidence adduced in the habeas proceeding—this Court finds that [Yowell] is unable to show [that], if the newly proffered evidence had been presented and explained, . . . there is a reasonable probability that the result of the sentencing phase would have been different. Yowell appealed to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, which affirmed the trial court's denial of relief and adopted it's findings of fact and conclusions of law.

Having exhausted his state remedies, Yowell filed a federal habeas petition, raising many of the same arguments as in his state habeas proceedings, including ineffective assistance. The district court granted habeas relief on several grounds, pretermitted two issues, and granted habeas relief for ineffective assistance. The court determined that although the state court correctly compared the mitigation evidence presented at the habeas hearing with the mitigation evidence presented at the actual punishment stage of trial but failed to note that . . . defense counsel rested without presenting any evidence during the punishment phase of trial; indeed, he did not even re-offer any of the evidence presented during the guilt/innocence phase, not the 850 pages of medical records or the testimony of Dr. Davis. Moreover, defense counsel, over his client's vocal objections, used his entire time for closing argument at punishment to replay the audio recording of Yowell's statement and confession to law enforcement. Thus, the state court erroneously concluded that "the complained of additional mitigation evidence [. . .] is not significant due to the similarity to evidence introduced at trial" because defense counsel introduced no evidence at the punishment phase.

The federal district court agreed with the state habeas court that "defense counsel presented a sympathetic picture of [Yowell's] background to the jury during trial," but "[u]nfortunately, none of this evidence was presented to the jury during the punishment phase of trial." The court concluded that the mitigating evidence might have influenced the jury, so Yowell suffered prejudice. The court summarily discounted the attorneys' arguments that their decision not to re-offer the trial evidence was a strategic decision, and the court thus determined that Yowell had received ineffective assistance. In a footnote, it ignored the state trial court's finding that the attorneys "were instructed by [Yowell] not to take any action that would result in the possibility of a life sentence as [Yowell] wanted a death sentence," and it decided that Yowell had made no such statement.

III.

In appeals of habeas relief for ineffective assistance of counsel, we review the district court's findings of fact for clear error but decide issues of law de novo. Richards v. Quarterman, 566 F.3d 553, 561 (5th Cir. 2009). A finding of fact is clearly erroneous "when, although there is enough evidence to support it, the reviewing court is left with a firm and definite conviction that a mistake has been committed." Myers v. Johnson, 76 F.3d 1330, 1333 (5th Cir. 1996). We must also consider the heightened standard of review imposed by the Antiter-rorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 ("AEDPA)", which states in 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d) that a federal court may not grant habeas relief after an adjudication on the merits in a state court proceeding unless the adjudication of the claim (1) "resulted in a decision that was contrary to, or involved an unreasonable application of, clearly established Federal law, as determined by the Supreme Court of the United States" or (2) "resulted in a decision that was based on an unreasonable determination of the facts in light of the evidence presented in the State court proceeding." Richards, 566 F.3d at 561 (quoting § 2254(d)).

Under the "unreasonable application" prong of § 2254(d)(1), a federal habeas court may grant the writ only "if the state court identifies the correct governing legal principle from [Supreme Court] decisions but unreasonably applies that principle to the facts" of the petitioner's case. Williams v. Taylor, 529 U.S. 362, 413, 120 S. Ct. 1495, 146 L. Ed. 2d 389 (2000). AEDPA provides that state court factual findings are presumptively correct and that the petitioner carries the burden of rebutting that presumption by clear and convincing evidence. § 2254(e)(1). The district court failed to give sufficient AEDPA deference to the state court's factual finding that Yowell's proferred mitigation evidence was cumulative. The state court conducted a lengthy evidentiary hearing on the matter and determined that, as we described above, even if the additional evidence had been introduced during the punishment phase, it was not significant in light of its similarity to the other evidence the defense had already presented during the guilt/innocence phase.

In Texas, "[t]here is no requirement that evidence admitted at guilt/innocence be re-offered to be considered at punishment." Buchanan v. State, 911 S.W.2d 11, 13 (Tex. Crim. App. 1995) (citing Ex parte Kunkle, 852 S.W.2d 499, 502 (Tex. Crim. App. 1993)). In Buchanan, the defendant argued that he should not have had to present evidence during punishment that, for a charge of aggravated kidnaping, he released the victim alive and in a safe place, where he had already presented that evidence during the guilt/innocence stage. Id. The state district court "concluded that the evidence to raise the issue of safe release must be presented at punishment because it would be unreasonable to expect our [triers of fact] to recall minute details from the guilt phase of trial." Id. at 14 (internal quotation marks omitted). The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals disagreed, saying that it is reasonable "to expect or require the trier of fact, whether the jury or the trial court, to consider the evidence admitted at guilt/innocence when assessing the punishment." Id.

The district court here did not give enough weight to that facet of Texas law. Had it done so, it would not have determined that the state court "erroneously concluded that 'the complained of additional mitigation evidence [. . .] is not significant due to the similarity to evidence introduced at trial' because defense counsel introduced no evidence at the punishment phase" or that "[u]nfortunately, none of this [mitigating] evidence was presented to the jury during the punishment phase of trial." Because the defense introduced mitigating evidence during trial, we must assume, as the state habeas court did, that the jury considered it during the punishment phase, especially in light of the fact that Yowell's attorney referred to the medical records during his closing statement. Thus, Yowell has failed to show by clear and convincing evidence that the state habeas court's factual findings were incorrect, and the district court clearly erred in determining that the state court unreasonably applied Washington, 466 U.S. at 691-92, to the facts.

We defer to the state habeas court's determination that Yowell has failed to show the necessary prejudice under Washington, and we reverse the habeas relief on Yowell's claim of ineffective assistance. Because the district court pre-termitted its consideration of two other grounds 3 for relief, we REVERSE and REMAND for the court to address only those pretermitted issues. 3 Namely grounds 2 and 6(a) as set forth in the district court's opinion.

Yowell v. Thaler, 2013 U.S. App. LEXIS 7663 (5th Cir. Tex. Apr. 16, 2013). (Federal Habeas)

PROCEDURAL POSTURE: Petitioner inmate was granted a writ of habeas corpus, which the court of appeals reversed and remanded for consideration of two pretermitted claims. On remand, the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas denied the claims and denied a certificate of appealability (COA). The inmate requested a COA from the court of appeals.

OVERVIEW: The inmate had been convicted of murder and was sentenced to death. At trial, a psychologist who testified as a defense witness was allowed to highlight information in medical records but was not allowed to give an opinion as to whether the inmate was insane at the time of the murders. The inmate claimed that his trial counsel rendered ineffective assistance by failing to elicit the psychologist's expert opinion via hypothetical questions. A state habeas court found that the inmate established neither deficient performance nor prejudice. The district court found that the state court's determination was reasonable and consistent with federal law, as the inmate's assertions regarding hypothetical questions were conclusional and speculative. The court of appeals held that the inmate was not entitled to a COA pursuant to 28 U.S.C.S. § 2253(c)(2) because the district court's conclusion was not reasonably debatable. The inmate also claimed that trial counsel should have re-offered the psychologist's testimony during the punishment phase, but because the mitigating evidence was introduced during trial, the jury was assumed to have considered it during the punishment phase.

OUTCOME: The request for a COA was denied.

PER CURIAM:

Michael Yowell was convicted of murder and sentenced to death. 1 We reversed a grant of habeas corpus relief and remanded for consideration of two pretermitted claims that had been rejected on the merits in state habeas proceedings. 2 On remand, the district court denied and dismissed with prejudice both claims and denied a certificate of appealability ("COA"). Yowell seeks a COA from this court. We deny his request.

1 The background facts, procedural history, and standards are set forth in this court's previous opinion. See Yowell v. Thaler, 442 F. App'x 100 (5th Cir. 2011). 2 Id. at 106 (remanding "for the court to address only those pretermitted issues").

I.

A COA is appropriate only if Yowell "has made a substantial showing of the denial of a constitutional right." 28 U.S.C. § 2253(c)(2). Because the district court rejected Yowell's claims on the merits, he "must demonstrate that reasonable jurists" would find the district court's decision "debatable or wrong." Slack v. McDaniel, 529 U.S. 473, 484, 120 S. Ct. 1595, 146 L. Ed. 2d 542 (2000). Where, as here, both claims were denied on the merits in state habeas proceedings, the proper question is "whether reasonable jurists could debate the district court's denial of habeas relief under the deferential standard of review mandated by § 2254(d) and (e)." Feldman v. Thaler, 695 F.3d 372, 377 (5th Cir. 2012). Under § 2254(d), the district court should have denied habeas relief unless the state court's adjudication (1) "resulted in a decision that was contrary to, or involved an unreasonable application of, clearly established Federal law, as determined by the Supreme Court of the United States" or (2) "resulted in a decision that was based on an unreasonable determination of the facts in light of the evidence presented in the State court proceeding." 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d). To meet that difficult standard, Yowell was required to show that the state habeas court's decision was "not only erroneous, but objectively unreasonable." Yarborough v. Gentry, 540 U.S. 1, 5, 124 S. Ct. 1, 157 L. Ed. 2d 1 (2003).

II. A.

At trial, the defense entered over 800 pages of medical records into evidence and called Dr. Philip Davis, a psychologist, to highlight important information regarding Yowell's mental health history. The court did not allow Davis to interpret those records or give an opinion as to Yowell's legal insanity at the time of the murders. According to Yowell, the court excluded the testimony as hearsay. He alleged in his habeas petition that his trial counsel rendered ineffective assistance in failing to elicit the doctor's expert opinion via unobjectionable hypothetical questions. The state habeas court found that Davis was unable to render an opinion as to whether Yowell was insane at the time of the murders and that Davis was not an expert on future dangerousness. Davis testified for two hours, highlighting the most important information in the medical records for the jury, as he had discussed with defense counsel before trial. Because Yowell failed to set forth what hypothetical questions should have been asked or what the answers would have been, the state court denied habeas relief; Yowell failed to establish either deficient performance or prejudice.

The district court held that that conclusion was reasonable and consistent with federal law. Yowell's assertions regarding hypothetical questions continued to be conclusional and speculative. Also, Davis testified that he could not render an opinion as to Yowell's sanity. Yowell could not, therefore, demonstrate prejudice from counsels' failure to ask hypothetical questions. Furthermore, the state court limited Davis's testimony not because of hearsay but because Davis had not examined Yowell and had not been designated as such an expert witness, which was a fully informed strategic decision by counsel. Yowell, 442 F. App'x at 102 & n.1. On appeal, Yowell does not criticize the district court's conclusion that failing to ask hypothetical questions was not ineffective assistance. Instead, he attempts to resurrect a previously dismissed argument, which he did not appeal, that his counsel were ineffective in failing to give notice of Davis's testimony. As the state points out, that claim is not properly before us, because it is beyond the scope of our limited remand. Yowell's failure to obtain a COA on the issue when it was dismissed precludes us from considering it now. 3 See Carty v. Thaler, 583 F.3d 244, 266 (5th Cir. 2009) (citing 28 U.S.C. § 2253(c); Sonnier v. Johnson, 161 F.3d 941, 946 (5th Cir.1998)).

The district court's conclusion—that the state court's adjudication was not objectively unreasonable—is not reasonably debatable. We have consistently held that conclusional and speculative allegations of ineffective assistance are not grounds for habeas relief. 4 Furthermore, it is not reasonably debatable that Davis's "admi[ssion] at trial that he was unable to render an opinion as to Yow-ell's sanity" would "preclude[] any prejudice regarding counsel's alleged failure" to elicit such an opinion through hypothetical questions.

4 E.g., Kinnamon v. Scott, 40 F.3d 731, 734-35 (5th Cir. 1994) (refusing to grant relief on conclusional and speculative claims of ineffective assistance); Barnard v. Collins, 958 F.2d 634, 642 n.11 (5th Cir. 1992) (holding that conclusional allegations of ineffective assistance were without merit "[i]n the absence of a specific showing of how these alleged errors and omissions were constitutionally deficient, and how they prejudiced his right to a fair trial").

Yowell also asserted in his petition that his trial counsel were ineffective in failing to re-offer Davis's testimony at the punishment phase. The state habeas court found that the medical records, highlighted by Davis during the guilt/innocence stage, presented a sympathetic portrait of Yowell's background. Trial counsel did not render ineffective assistance, the state court concluded, in failing to present similar evidence during the punishment phase, nor did their failure prejudice Yowell. The district court held that the state habeas court's determination was not objectively unreasonable. "In Texas, '[t]here is no requirement that evidence admitted at guilt/innocence be re-offered to be considered at punishment.'" 5 "Because the defense introduced mitigating evidence during trial, we must assume, as the state habeas court did, that the jury considered it during the punishment phase, especially in light of the fact that Yowell's attorney referred to the medical records during his closing statement." Id. The district court's conclusion is not reasonably debatable.

5 Yowell, 442 F. App'x at 105 (quoting Buchanan v. State, 911 S.W.2d 11, 13 (Tex. Crim. App. 1995) (second alteration in original)).

B.

In his petition, Yowell also argued that he was entitled to relief because his appellate counsel was ineffective in failing to raise on appeal his trial counsels' failure to elicit Davis's opinion through hypothetical questioning. The state habeas court denied relief, because Yowell had failed to establish why appellate counsel acted as he did or to demonstrate that Yowell would have prevailed on appeal. The district court denied relief because (1) Yowell had failed to show that the state court's determination was objectively unreasonable and (2) because he could not demonstrate that, had appellate counsel raised his claim on appeal, the conviction would have been reversed, much less that counsel's failure resulted in the proceedings' being fundamentally unfair or unreliable. See Goodwin v. Johnson, 132 F.3d 162, 174 (5th Cir. 1997).

Yowell fails to mention this issue in his request for COA and accompanying brief, so he has abandoned it as a ground for a COA. See Trevino v. Johnson, 168 F.3d 173, 181 n.3 (5th Cir. 1999). Furthermore, because appellate counsel was under no obligation to raise every nonfrivolous claim, see Jones v. Barnes, 463 U.S. 745, 753-54, 103 S. Ct. 3308, 77 L. Ed. 2d 987 (1983), the district court's conclusion is not reasonably debatable.

The request for a COA is DENIED.