27th murderer executed in U.S. in 2014

1386th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

7th murderer executed in Missouri in 2014

77th murderer executed in Missouri since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(27) |

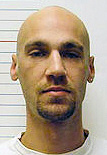

Michael Shane Worthington W / M / 24 - 43 |

Melinda “Mindy” Griffin W / F / 24 |

Summary:

Worthington pled guilty, confessing that he cut open a window screen to break into the condominium of his neighbor, 24-year-old college student Melinda “Mindy” Griffin. Worthington admitted he choked Griffin until she was unconscious, then raped her. When she awoke and fought back, Worthington strangled her to death. He stole her car keys and jewelry, along with credit cards he used to buy drugs. On the morning after the murder Worthington was pulled over while driving Griffin’s vehicle. He was wearing a fanny pack containing jewelry that belonged to Griffin. He was taken into custody and threatened to commit suicide. DNA testing of semen found on Griffin’s body also tied Worthington to the crimes.

Citations:

State v. Worthington, 8 S.W.3d 83 (Mo. 1999). (Direct Appeal)

Worthington v. State, 166 S.W.3d 566 (Mo. 2005). (PCR)

Worthington v. Roper, 631 F.3d 487 (8th Cir. Mo. 2011). (Federal Habeas)

Final Meal:

A cheeseburger, french fries, a rib-eye steak, and onion rings.

Final Words:

Worthington issued a final statement before his execution, including no apology for the crimes. He said, “Thank you, I will finally get to live in peace with my true Father. I’ll no longer have to suffer. It’s really my beloved friends and family that will suffer. May God forgive those who call this justice. When in truth, it’s truly about politics and revenge. Amen and peace to unto you all.”

Internet Sources:

"Missouri inmate executed for killing Lake Saint Louis neighbor in 1995," by Jim Suhr. (AP August 06, 2014)

BONNE TERRE • A Missouri inmate was put to death Wednesday for raping and killing a college student in 1995, making him the first U.S. prisoner put to death since an Arizona lethal injection went awry last month. The Missouri Department of Corrections said Michael Worthington was executed by lethal injection at the state prison and was pronounced dead at 12:11 a.m. He is the seventh Missouri inmate executed this year.

Worthington had been sentenced to death for the attack on 24-year-old Melinda "Mindy" Griffin during a burglary of her Lake Saint Louis condominium. Before the execution began, while strapped to a gurney and covered with a sheet, Worthington spoke with his witnesses — some of them his relatives — through the glass, raising his shaved head. When the drugs began flowing, his head lowered back to the pillow and he appeared to breathe heavily for about 15 seconds before closing his eyes. Some of his witnesses began crying after he fell unconscious.

The U.S. Supreme Court and Missouri's governor had declined on Tuesday to block the execution. Worthington, 43, had predicted that the nation's high court and Gov. Jay Nixon would not spare him, insisting in a telephone interview with The Associated Press that he had accepted his fate. "I figure I'll wake up in a better place tomorrow," Worthington, formerly of Peoria in central Illinois, had said Tuesday. "I'm just accepting of whatever's going to happen because I have no choice. The courts don't seem to care about what's right or wrong anymore."

Worthington's attorneys had pressed the Supreme Court to put off his execution, citing the Arizona execution and two others that were botched in Ohio and Oklahoma, as well as the secrecy involving the drugs used during the process in Missouri.

Those three executions in recent months have renewed the debate over lethal injection. In Arizona, the inmate gasped more than 600 times and took nearly two hours to die. In April, an Oklahoma inmate died of an apparent heart attack 43 minutes after his execution began. And in January, an Ohio inmate snorted and gasped for 26 minutes before dying. Most lethal injections take effect in a fraction of that time, often within 10 or 15 minutes. Arizona, Oklahoma and Ohio all use midazolam, a drug more commonly given to help patients relax before surgery. In executions, it is part of a two- or three-drug lethal injection.

Texas and Missouri instead administer a single large dose of pentobarbital — often used to treat convulsions and seizures and to euthanize animals. Missouri changed to pentobarbital late last year and since has carried out executions during which inmates showed no obvious signs of distress. Missouri and Texas have turned to compounding pharmacies to make versions of pentobarbital. But like most states, they refuse to name their drug suppliers, creating a shroud of secrecy that has prompted lawsuits.

In denying Worthington's clemency request, Nixon called Worthington's rape and killing of Griffin "horrific," noting that "there is no question about the brutality of this crime — or doubt of Michael Worthington's guilt."

Worthington was sentenced to death in 1998 after pleading guilty to Griffin's death, confessing that in September 1995 he cut open a window screen to break in to the college finance major's condominium in Lake Saint Louis. Worthington admitted he choked Griffin into submission and raped her before strangling her when she regained consciousness. He stole her car keys and jewelry, along with credit cards he used to buy drugs. DNA tests later linked Worthington to the slaying.

Worthington, much as he did after his arrest, insisted to the AP on Tuesday from his holding cell near the death chamber that he couldn't remember details of the killing and that he was prone to blackouts due to alcohol and cocaine abuse. He said a life prison sentence would have been more appropriate for him. "In 20 years, no one's seen or heard from me," he said. "If I'm the one who did it, what do they think life without parole is — a piece of cake?

Before the execution, Griffin's 76-year-old parents anticipated witnessing Worthington die. Her mother, Carol Angelbeck, said she was disappointed to learn that the glass in the room where she will view the execution is one way and Worthington wouldn't be able to see her. “I wanted him to know that I was there, that even though I wasn’t there to protect my daughter, I was there to see this done,” she told the Post-Dispatch.

Angelbeck said she wasn't sure how she would feel when the execution was over, but hoped it would bring some peace. “I won’t have to think about what he did to her any more,” she said. “I can just remember my Mindy; she’ll always be in my heart.” Worthington, when asked what he would say to Griffin's parents, directed his comments to her mother. "If my life would bring her peace and bring Mindy back, I'd be fine with that. But it won't," he said. "It doesn't bring peace or closure. She's still going to have her broken heart."

"Missouri killer executed, scrutiny high after Arizona," by Carey Gillam and Eric M. Johnson. (Aug 6, 2014)

(Reuters) - Missouri officials executed convicted killer Michael Worthington on Wednesday despite calls for caution after a problematic execution in Arizona last month, when a condemned prisoner took more than an hour to die. The Missouri execution was the first since the July 23 execution in Arizona of Joseph Wood, who some witnesses said gasped and struggled for breath for more than 90 minutes as he was put to death at a state prison complex.

The 43-year-old Worthington was pronounced dead at 12:11 a.m. CDT (0511 GMT) at a prison facility in Bonne Terre, said Missouri Department of Corrections spokesman Mike O'Connell. He was convicted of murder for the 1995 rape and strangling of a university student in the St. Louis area.

The U.S. Supreme Court on Tuesday denied two different stay applications filed by Worthington's attorneys that had asked the high court to prohibit Missouri from executing Worthington until more scrutiny is given to what happened in Arizona and to secrecy in Missouri about the lethal injection drugs being used. "It seems like it would be a reasonable request. The Arizona case ... gives us some additional ammunition," said attorney Kent Gibson, who is representing Worthington.

Missouri Governor Jay Nixon said on Tuesday that he had denied Worthington's clemency petition, calling the rape and murder of 24-year-old Melinda 'Mindy' Griffin a "horrific killing." "DNA evidence and his possession of items stolen from her home reinforced his confession and guilty pleas to murder, rape and burglary," Nixon said in a statement. Griffin was finishing her final year of study at University of Missouri-St. Louis "when her promising life was cut short," state Attorney General Chris Koster said by e-mail.

The complications in the Arizona execution came after two other lethal injections went awry this year in Ohio and Oklahoma. The American Civil Liberties Union on Monday called for a national suspension of executions due to what it has called a string of "botched" executions, citing a need for states to provide more transparency and accountability. Lethal injection drugs have been the subject of mounting controversy and court challenges as many states have started using drugs supplied by lightly regulated compounding pharmacies because traditional suppliers have backed away from the market. Several states, including Missouri, have refused to provide details about where they are getting the drugs.

Missouri said on Tuesday there is no need to suspend executions. The state uses pentobarbital, not the two-chemical combination used in Arizona, and its execution procedure is proper, Koster's office said. Worthington was one of more than a dozen death row prisoners who are challenging Missouri's lethal injection protocols in a federal lawsuit. A hearing in that case is set for Sept. 9 in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit in St. Louis.

Classification: MurdererCharacteristics: Rape - Robbery

Number of victims: 1

Date of murder: September 30, 1995

Date of arrest: Next day (suicide attempt)

Date of birth: January 30, 1971

Victim profile: Melinda Griffin (his neighbor)

Method of murder: Ligature strangulation

Location: St. Charles County, Missouri, USA

Status: Sentenced to death on January 4, 1999

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Missouri Supreme Court

Worthington Brief - State Brief - Worthington Reply Brief

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

State of Missouri v. Michael Shane Worthington

Missouri Supreme Court Case Number: SC81356

Case Facts: On September 29, 1995, appellant, Worthington, and a friend from work, Jill Morehead, were at his condominium in Lake St. Louis, watching television. At about 4:00 p.m., they left to pick up their paychecks from their employer, a local supermarket. They returned to the condo and had dinner and drinks. They then went to a nightclub where each had three drinks. After about two hours, Worthington and Morehead drove to Jennings where Worthington told Morehead he had to pick up money owed to him by a friend. Worthington testified he actually went to pick up drugs. Morehead stayed in her vehicle, while Worthington was in the house for about 15 minutes. They drove back to his condo where he left Morehead. Morehead left the condo when Worthington did not return after about 45 minutes.

Later that night, Worthington saw that the kitchen window was open in the condominium of his neighbor, Melinda Griffin. Worthington had seen Ms. Griffin around the condominium complex. He got a razor blade and gloves, and when he returned to her condo, he saw that a bathroom light had been turned on. Worthington cut through the screen. He confronted Ms. Griffin in the bedroom. He covered her mouth to stop her screams and strangled her until she became unconscious. Worthington began to rape her and she regained consciousness. Ms. Griffin fought Worthington, and he beat her and strangled her to death. The wounds on her neck showed that Worthington used a rope or cord in addition to his hands to strangle her. He stole her jewelry, credit cards, mobile phone, keys, and her car.

The next morning, September 30, 1995, a police officer pulled Worthington over. Worthington was driving Ms. Griffin's car. The officer noticed a woman's items in the car such as make-up and shoes, but the car had not been reported stolen. The next day, October 1, a neighbor discovered Ms. Griffin's body. When police arrived, they found the screen in the kitchen window had been cut to gain entry. They found Ms. Griffin's body lying bruised, bloody, and unclothed at the foot of the bed, with a lace stocking draped across it. All the bedroom drawers had been pulled open. DNA testing later established that semen found on Ms. Griffin's body came from Worthington.

Police officers found Worthington that evening, but when he saw the police, he pulled out a knife, held it to his throat, and threatened to commit suicide. Police officers convinced him to put the knife down and brought him into custody. Worthington was wearing a fanny pack containing jewelry and keys belonging to Ms. Griffin.

At the police station, Worthington relayed his story of four days of drinking and getting high. After being presented with the evidence against him, Worthington confessed to the killing but could not remember the details since, he said, he was prone to blackouts when using alcohol and cocaine. At the time the offenses occurred, Worthington said he was extremely high on Prozac, cocaine, marijuana, and alcohol. Worthington also said that two friends, Darick and Anthony, helped him with the burglary. However, this story was inconsistent with the physical evidence and with subsequent statements made by Worthington.

Worthington pleaded guilty to the crimes charged. The judge imposed the death penalty for the murder conviction, as well as the prison terms for the other offenses. Worthington does not challenge the plea and sentences on the other offenses; his appeal here concerns only the death penalty.

"Investigators: ‘no doubt’ executed Missouri inmate Worthington was guilty," by Mike Lear. (VIDEO)

Michael Shane Worthington spent 19 years in custody after the burglary, rape and murder of 24-year-old Melinda Griffin of Lake St. Louis. He was sentenced to death after confessing to those crimes, and his execution was carried out early Wednesday morning at the prison in Bonne Terre. Worthington spent much of those 19 years attempting to cast doubt on his guilt. He claimed that his attorney at the time of the trial convinced him to plead guilty, and that he actually had no memory of the crimes due to drug and alcohol use that night. He also suggested that two other men had likely committed the murder as part of a burglary.

“There’s never been a doubt in my mind that Michael Worthington murdered Mindy Griffin,” says Lake St. Louis Police Department Chief Mike Force. Force witnessed the execution, having worked Griffin’s case. “19 years is a long time, and certainly across those 19 years you’d have plenty of time to imagine this story or that story or the other story,” says Force. “I think Mr. Worthington did a good job of imagining those. They changed constantly.”

Retired Lake Saint Louis Police detective Don Bolen agrees. He doesn’t recall that Worthington ever apologized for the crimes against Griffin. “The only thing he was sorry about was being caught and being tried, and that he confessed,” says Bolen. Both men have worked numerous cases including other murders, but felt the need to see this case through to the end. Bolen says Griffin was a vibrant person that was instantly liked by anyone who met her. “I never met her, but I came to know her through other folks,” says Bolen. “She’s a wonderful person.”

Force says it was the people involved in the case that made it stick out. “This is a wonderful family, a loving family. Mindy Griffin was an inspirational young lady who was doing great things in her life. She was young, beautiful, just on the brink of flowering in life. She was finishing up school, she was a volunteer for a lot of good causes – just a good person,” says Force. “To see that life wasted that way and the impact that it’s had on this family is a horrible thing.” Chief Force and Detective Bolen (ret.) discuss the impact the Griffin case had on them:

Both men say the Department’s major case squad deserves recognition for its role in the case. “They had a lot of feet on the ground very quickly. I think we had him in custody in a day and a half,” says Force. Griffin was attacked in her own condominium. Force is asked whether such cases should leave people wondering if they are safe anywhere. “I talk to citizens groups all the time,” says Force. “I try to impress upon them the importance of never living in fear, but always living with awareness. I think if we make ourselves just a little more aware, I think we become safer.” “In Mindy’s case I don’t think she could have done anything differently,” says Bolen. “Michael forced his way into her house, he hid in the closet. She had no reason to suspect anything was going on, anything was wrong … it’s just sad.”

Griffin’s family say there was no doubt of Worthington’s guilt from his first day at the Lake Saint Louis Police Department. They invited Force and Bolen to be among the witnesses to Worthington’s execution, along with members of the prosecution team and victims’ advocates, who they say helped the family deal with her death and the two decades that have followed. "No delays as Missouri executes Michael Shane Worthington," by Mike Lear. (August 6, 2014)

Missouri has executed convicted killer Michael Shane Worthington 16 years after he pled guilty to the 1995 rape and murder of a Lake Saint Louis woman. 6 witnesses for Worthington watched the execution including relatives, his step-mother and a girlfriend, and he never looked away from them. He was speaking to them when the curtain on the witness rooms opened, and while 5 grams of pentobarbital were administered at 12:01 a.m. He appeared to quit talking to his family by 12:02 and appeared to quit breathing at 12:03. The Department of Corrections places the time of death at 12:11.

Worthington died with a Bible on his chest. Worthington issued a final statement before his execution, including no apology for the crimes. He said, “Thank you, I will finally get to live in peace with my true Father. I’ll no longer have to suffer. It’s really my beloved friends and family that will suffer. May God forgive those who call this justice. When in truth, it’s truly about politics and revenge. Amen and peace to unto you all.” He is the ninth inmate executed by Missouri since November.

The execution was carried out as scheduled after the U.S. Supreme Court declined to consider his appeals. Governor Jay Nixon (D) then denied Worthington clemency, allowing the Department of Corrections to carry out the lethal injection. The execution has drawn additional attention for being the first in the nation since Arizona inmate Joseph Rudolph Wood III took more than 90 minutes to die in an execution there last month. Missouri uses a different, one-drug procedure to carry out lethal injections than the one Arizona used that involved a combination of drugs.

Worthington, who was 43, confessed in 1999 to breaking into the condominium of his neighbor, 24-year-old Melinda “Mindy” Griffin, choking her until she was unconscious, raping her, and when she awoke and fought back, strangling her to death. On the morning after the murder Worthington was pulled over while driving Griffin’s vehicle. He was wearing a fanny pack containing jewelry that belonged to Griffin. He was taken into custody after threatening to commit suicide. DNA testing of semen found on Griffin’s body also tied Worthington to the crimes. The facts that he committed the murder in connection with the rape and burglary were considered aggravating factors in his sentencing.

Missouri is next scheduled to execute convicted inmate Leon Taylor September 10, for the 1994 murder of Robert Newton in Independence. Watch Missourinet.com for more details following the execution of Michael Shane Worthington.

"MO Attorney General issues statement on Worthington execution," by Mike Lear. (August 6, 2014)

Missouri Attorney General Chris Koster issued a brief statement upon the execution of Michael Shane Worthington, carried out early Wednesday morning. Koster writes, “Mindy Griffin’s parents waited for nearly two decades for justice for their daughter. She was just 24-years old, finishing the final year of her studies at UMSL when her promising life was cut short. Tonight, Michael Worthington paid the price for his callous brutality.” "No clemency for Worthington," by Bob Priddy. (August 5, 2014)

One more door has been closed for prison inmate Michael Worthington, due to be executed just after midnight. Governor Nixon has denied clemency. Earlier this evening, the U. S. Supreme Court refused to take up Worthington’s latest appeal. The Governor’s statement says: “Today, my counsel provided me with a final briefing on the comprehensive review of the petition for clemency from convicted murderer and rapist Michael Worthington. Each request for clemency is considered and decided on its own merit and set of facts, and this is a process and a power of the Governor I do not take lightly. After due consideration of the facts, I am denying this petition.

There is no question about the brutality of this crime – or doubt of Michael Worthington’s guilt. Melinda “Mindy” Griffin, only 24 years old, was viciously raped and killed in her own home by Worthington. DNA evidence and his possession of items stolen from her home reinforced his confession and guilty pleas to murder, rape and burglary. My denial of clemency upholds the court’s decision to impose the death penalty for this horrific killing. I ask that the people of Missouri remember Mindy Griffin, and keep her and her family in their thoughts and prayers.”

"SCOTUS refuses to hear Worthington appeal," by Bob Pridyy. (August 5, 2014)

The U. S. Supreme Court has refused to hear another appeal from prison inmate Michael Worthington, who is scheduled to be executed just after midnight tonight. Worthington has been convincted of killing a Lake St. Louis woman in 1995. Worthington claims drugs and alcohol robbed him of his memories of that night, but also claims drugs and alcohol make it unlikely he committed the crime.

"Woman near end of 19-year wait for killer's execution," by Susan Weich. (August 05, 2014 12:15 am)

LAKE SAINT LOUIS • Carol and Jack Angelbeck headed straight to the cemetery from the airport Monday. They’re back in town because Michael Worthington, the killer of Carol Angelbeck’s daughter, is scheduled to be executed just after midnight Tuesday. Melinda “Mindy” Griffin, who loved horses, is buried in the Cemetery of Our Lady, not far from the National Equestrian Center in Lake Saint Louis.

“From the time she could talk, she said horse; that’s all she ever wanted,” Carol Angelbeck said. The Angelbecks raised Clydesdales on their farm in Troy, Mo. Griffin helped take care of the animals and drove them in shows around the country. She also was a full-time finance student at the University of Missouri-St. Louis and worked at two restaurants to support herself. The Angelbecks now live in Ocala, Fla., where they continue to raise draft horses.

Angelbeck said the nearly 19-year wait to carry out the death sentence has been too long. And she is worried about a last-minute stay because of problems with a recent execution in Arizona. Worthington’s attorney, Kent Gipson of Kansas City, said he is hoping for a stay on those grounds. In the Arizona case, the state used a two-drug cocktail including a Valium-like drug, midazolam, that is often given to patients before surgery, and an opioid, hydromorphone, which in high doses stops respiration. Missouri uses a single heavy dose of the sedative pentobarbital. Angelbeck said the stay request should be rejected because Missouri does not use the same drugs as Arizona. “Besides, this case is cut and dried,” she said.

Worthington pleaded guilty to murdering Griffin, 24, in her Lake Saint Louis condominium on Sept. 30, 1995. He said he had spent the day drinking and using drugs before he broke in. He strangled Griffin to get her to be quiet and then started raping her. When Griffin regained consciousness and began to fight back, Worthington said he strangled her until she stopped breathing. “I only listened to a half a minute of it before I asked the judge if I could leave,” Angelbeck said, “but I read the transcripts. He said it matter of fact, like he was reading a book.”

Worthington, who also was 24 at the time of the murder, was captured a few days later in Jennings. He was in Griffin’s car and had some of her jewelry and other belongings. Worthington entered the plea in front of then-Circuit Court Judge Grace Nichols in the hopes of getting life in prison, but Nichols gave him the death penalty.

His attorneys argued unsuccessfully that mitigating circumstances warranted the lesser penalty. Worthington of Peoria, Ill., had an abusive childhood. His father taught him to steal and take drugs before he was 13. His mother was a crack addict and later turned to prostitution. Worthington would be the seventh person executed in Missouri this year. The state Supreme Court recently scheduled an execution for Sept. 10 for the killer of a service station attendant in Independence, Mo.

Angelbeck, now 76, said for the first five years after her daughter’s death, she prayed every day for God to let her die. “I couldn’t live with the pain,” she said. “It was a pain that I don’t even know if it was in my head or my stomach or what. I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t sleep, I couldn’t do anything.” Angelbeck waited until Worthington was sentenced before she ordered a marker for her daughter’s grave because she couldn’t bear to see Griffin’s name and date of death in stone.

Mindy Griffin, 24, was murdered Sept. 30, 1995, at her condominium in Lake Saint Louis. She is pictured here outside her condo with her dog, Baron. Her killer, Michael Shane Worthington, is scheduled to be executed at 12:01 a.m. on Aug. 6, 2014. Over the years, the Angelbecks coped by starting a local chapter of Parents of Murdered Children. They established a scholarship fund in their daughter’s name at UMSL and a trophy for Best Lady Driver in her name with a national Clydesdale association.

On Monday, the Angelbecks went to the grave with Griffin’s older sister, Debbie Selecky, and her husband Jim, who live in Chesterfield. Lake Saint Louis Police Chief Mike Force and Assistant Chief Chris DiGiuseppe, arrived a short time later. Jim Selecky used a shovel to dig a small hole near Griffin’s headstone to bury the ashes of Baron, her Newfoundland. The dog was five months old when Griffin was murdered, and neighbors recalled seeing her walking the puppy around the complex. Griffin’s black granite tombstone is etched with a picture of her driving a cart pulled by a Clydesdale and a quote from “The Little Prince” about living in the stars. Angelbeck worried that the drawing was fading, and Griffin’s dress no longer looked red. She placed a single red rose in the ground with a note that read, “My precious Mindy, I miss you so much.” Afterward, family members sat on a bench the Angelbecks had put in under a tree.

Force said he comes to the grave a couple of times a week, sits on the bench and reflects. He didn’t know Griffin before her death but became close to the family during the trial and subsequent appeals. The murder was the first in Lake Saint Louis. At the sentencing, Force testified about the impact Griffin’s death had on the residents, especially the women, of the quiet community. “When I learned Mindy’s background and what she did in life and what she did to help other people, her murder was so senseless,” he said.

Force, along with then-prosecutor Tim Braun, victims advocates and friends of the Angelbecks will be with the Angelbecks at the execution, set for 12:01 a.m. Wednesday at the state prison in Bonne Terre. Angelbeck said she was disappointed to learn that the glass in the room where she will view the execution is one way — Worthington won’t be able to see her. “I wanted him to know that I was there, that even though I wasn’t there to protect my daughter, I was there to see this done,” she said.

Angelbeck said some people have asked her if it would have been easier on her if the judge had sentenced Worthington to life in prison. She said it wouldn’t have been. “The only way they can guarantee me that Worthington will never rape or kill another human being is to execute him, and that’s why I believe in the death penalty,” she said.

Until the Missouri Supreme Court set Worthington’s execution date, Angelbeck said she didn’t think about him much, but her daughter has remained the first thing on her mind in the morning and the last thing at night. With the execution looming, she said she has relived everything they went through. “I’ve asked God many times to be with me and show me the way,” she said. “I know that you’re supposed to be able to forgive them, but I don’t know that I can ever forgive him for taking my daughter’s life like he did.” Angelbeck is not sure how she’ll feel when it’s over, but she is hoping, finally, for peace. “I won’t have to think about what he did to her any more,” she said. “I can just remember my Mindy; she’ll always be in my heart.”

• 'I will wake up in a better place tomorrow' Missouri man who raped and killed student is executed.

• Secrecy over what drugs were used after botched lethal injection scandals

• Michael Worthington had appealed to supreme court to delay execution

• He cited a botched execution in Arizona where inmate gasped 600 times

• Two other bungled injections have also renewed debate over drugs used

By Simon Tomlinson. (01:50 EST, 6 August 2014)

A Missouri inmate has been put to death for raping and killing a college student, making him the first U.S. prisoner put to death since the Arizona lethal injection went horrendously awry last month. The Missouri Department of Corrections said Michael Worthington was executed by lethal injection at the state prison and was pronounced dead at 12.11am yesterday. He is the seventh Missouri inmate to be executed this year. Worthington had been sentenced to death for the attack on 24-year-old Melinda 'Mindy' Griffin during a burglary of her Lake St Louis condominium in 1995.

Before the execution began, while strapped to a gurney and covered with a sheet, Worthington spoke with his witnesses — some of them his relatives — through the glass, raising his shaved head. When the drugs began flowing, his head lowered back to the pillow and he appeared to breathe heavily for about 15 seconds before closing his eyes. Some of his witnesses began crying after he fell unconscious. A Bible had been placed on his chest at his request, and he left a six-sentence written statement offering no apology.

The U.S. Supreme Court and Missouri's governor had declined on Tuesday to block the execution. Worthington, 43, had predicted that the nation's high court and Governor Jay Nixon would not spare him, insisting in a telephone interview with The Associated Press news agency that he had accepted his fate. 'I figure I'll wake up in a better place tomorrow,' Worthington, formerly of Peoria in central Illinois, had said Tuesday. 'I'm just accepting of whatever's going to happen because I have no choice. The courts don't seem to care about what's right or wrong anymore.'

Worthington's attorneys had pressed the Supreme Court to put off his execution, citing the Arizona execution and two others that were botched in Ohio and Oklahoma as well as the secrecy involving the drugs used during the process in Missouri. Those three executions in recent months have renewed the debate over lethal injection. In Arizona, the inmate gasped more than 600 times and took nearly two hours to die. In April, an Oklahoma inmate died of an apparent heart attack 43 minutes after his execution began. And in January, an Ohio inmate snorted and gasped for 26 minutes before dying. Most lethal injections take effect in a fraction of that time, often within 10 or 15 minutes.

Arizona, Oklahoma and Ohio all use midazolam, a drug more commonly given to help patients relax before surgery. In executions, it is part of a two- or three-drug lethal injection. Texas and Missouri instead administer a single large dose of pentobarbital — often used to treat convulsions and seizures and to euthanize animals.

Missouri changed to pentobarbital late last year and since has carried out executions during which inmates showed no obvious signs of distress. Missouri and Texas have turned to compounding pharmacies to make versions of pentobarbital. But like most states, they refuse to name their drug suppliers, creating a shroud of secrecy that has prompted lawsuits.

In denying Worthington's clemency request, Nixon called Worthington's rape and killing of Griffin 'horrific,' noting that 'there is no question about the brutality of this crime — or doubt of Michael Worthington's guilt.' Worthington was sentenced to death in 1998 after pleading guilty to Griffin's death, confessing that in September 1995 he cut open a window screen to break in to the college finance major's condominium in Lake St. Louis, just west of St. Louis.

Worthington admitted he choked Griffin into submission and raped her before strangling her when she regained consciousness. He stole her car keys and jewelry, along with credit cards he used to buy drugs. DNA tests later linked Worthington to the slaying. Worthington, much as he did after his arrest, insisted to the AP on Tuesday from his holding cell near the death chamber that he couldn't remember details of the killing and that he was prone to blackouts due to alcohol and cocaine abuse.

He said a life prison sentence would have been more appropriate for him. 'In 20 years, no one's seen or heard from me,' he said. 'If I'm the one who did it, what do they think life without parole is — a piece of cake?

On Tuesday, Griffin's 76-year-old parents anticipated witnessing Worthington die. 'It's been 19 years, and I feel like there's going to be a finality,' Griffin's mother, Carol Angelbeck said after flying to Missouri from their Florida home. 'I won't have to ever deal with the name Michael Worthington again. I'm hoping for my family's sake, my sake, that we can go there (to the prison) and get this over with.' 'In this case, there is no question in anyone's mind he did it, so why does it take 18 or 19 years to go through with this?' added Jack Angelbeck, Griffin's father. 'This drags on and on. At this point, it's ridiculous, and hopefully it's going to end.'

Worthington, when asked what he would say to Griffin's parents, directed his comments to her mother. 'If my life would bring her peace and bring Mindy back, I'd be fine with that. But it won't,' he said. 'It doesn't bring peace or closure. She's still going to have her broken heart.'

"Missouri execution was quick and quiet," by Frances Burns. (Aug. 6, 2014 at 2:15 PM)

BONNE TERRE, Mo., Aug. 6 (UPI) -- Missouri put Michael Shane Worthington to death quickly and quietly Wednesday -- a contrast to the most recent U.S. execution, which took more than 90 minutes. Worthington was pronounced dead at 12:11 a.m. He spent his last conscious moments talking to his stepmother, girlfriend and relatives. Democratic Gov. Jay Nixon denied a request for clemency after the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear Worthington's final appeals.

Worthington, 43, was sentenced to death for raping and killing a neighbor, Melinda "Mindy" Griffin, in 1995. He did not apologize to her family in a last statement. "Thank you, I will finally get to live in peace with my true Father. I'll no longer have to suffer. It's really my beloved friends and family that will suffer," he said. "May God forgive those who call this justice. When in truth, it's truly about politics and revenge. Amen and peace to unto you all." Worthington had a Bible on his chest as he was put to death.

On July 23, Joseph Rudolph Wood III was put to death in Arizona using a two-drug protocol. While most executions by lethal injection take about 10 minutes, Wood was not pronounced dead for almost two hours, and some witnesses said he appeared to be gasping for air for much of that time. Missouri, which has carried out nine executions since last November, uses a single-drug protocol. The apparently botched executions of Wood and of Clayton Lockett in Oklahoma have raised questions about the way the death penalty is carried out. Death-penalty states have turned to compounding pharmacies for execution drugs, as pharmaceutical companies refuse to supply them.

On September 29, 1995, Michael Worthington and a friend from work, Jill Morehead, were at his condominium in Lake St. Louis, watching television. At about 4:00 p.m., they left to pick up their paychecks from their employer, a local supermarket. They returned to the condo and had dinner and drinks. They then went to a nightclub where each had three drinks. After about two hours, Worthington and Morehead drove to Jennings where Worthington told Morehead he had to pick up money owed to him by a friend. Worthington testified he actually went to pick up drugs. Morehead stayed in her vehicle, while Worthington was in the house for about 15 minutes. They drove back to his condo where he left Morehead. Morehead left the condo when Worthington did not return after about 45 minutes.

Later that night, Worthington saw that the kitchen window was open in the condominium of his neighbor, Melinda Griffin. Worthington had seen Melinda around the condominium complex. He got a razor blade and gloves, and when he returned to her condo, he saw that a bathroom light had been turned on. Worthington cut through the screen. He confronted Melinda in the bedroom. He covered her mouth to stop her screams and strangled her until she became unconscious. Worthington began to rape her and she regained consciousness. Worthington raped Melinda with such force that he bruised the inside of her vagina, tore both labia minora, and made a large, deep tear between her vagina and anus. Melinda fought Worthington, and he beat her and strangled her to death. The wounds on her neck showed that Worthington used a rope or cord in addition to his hands to strangle her.

He stole her jewelry, credit cards, mobile phone, keys, and her car. The next morning, September 30, 1995, a police officer pulled Worthington over. Worthington was driving Melinda's car. The officer noticed a woman's items in the car such as make-up and shoes, but the car had not been reported stolen. The next day, October 1, a neighbor discovered Melinda's body. When police arrived, they found the screen in the kitchen window had been cut to gain entry. They found Melinda's body lying bruised, bloody, and naked at the foot of the bed, with a lace stocking draped across it. All the bedroom drawers had been pulled open.

DNA testing later established that semen found on Melinda's body came from Worthington. Police officers found Worthington that evening, but when he saw the police, he pulled out a knife, held it to his throat, and threatened to commit suicide. Police officers convinced him to put the knife down and brought him into custody. Worthington was wearing a fanny pack containing jewelry and keys belonging to Melinda. At the police station, Worthington relayed his story of four days of drinking and getting high. After being presented with the evidence against him, Worthington confessed to the killing but could not remember the details since, he said, he was prone to blackouts when using alcohol and cocaine. At the time the offenses occurred, Worthington said he was extremely high on Prozac, cocaine, marijuana, and alcohol.

Worthington also said that two friends, Darick and Anthony, helped him with the burglary. However, this story was inconsistent with the physical evidence and with subsequent statements made by Worthington. Worthington pleaded guilty to the crimes charged. The judge imposed the death penalty for the murder conviction, as well as the prison terms for the other offenses.

Missourians to Abolish the Death Penalty

Missourians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty

Meet the 36 men Missouri has executed since 2000 (Slideshow)

Last week, Michael Worthington became the 36th man to be executed by the state of Missouri since Jan. 1, 2000. All of the descriptions of their crimes have been taken from court records and police reports.

A total of 77 individuals convicted of murder have been executed by the state of Missouri since 1976. All were by executed by lethal injection. All executions in Missouri were suspended between June 26, 2006, and June 4, 2007, due to a federal court ruling. Executions resumed on May 20, 2009.

1. George Mercer January 6, 1989 Karen Keeton

2. Gerald Smith January 18, 1990 Karen Roberts

3. Winford L. Stokes, Jr. May 17, 1990 Pamela Brenda

4. Leonard Marvin Laws May 17, 1990 John Seward

5. George Clifton Gilmore August 21, 1990 Mary Luella Watters

6. Maurice Oscar Byrd August 23, 1991 Judy Cazaco, James Wood, Edna Ince, and Carolyn Turner

7. Ricky Lee Grubs October 21, 1992 Jerry Thornton

8. Martsay Bolder January 27, 1993 Theron King

9. Walter Junior Blair July 21, 1993 Kathy Jo Allen

10. Frederick Lasley July 28, 1993 Janie Tracy

11. Frank Joseph Guinan October 6, 1993 John McBroom

12. Emmitt Foster May 3, 1995 Travis Walker

13. Larry Griffin June 21, 1995 Quintin Moss

14. Robert Anthony Murray July 26, 1995 Jeffrey Jackson and Craig Stewart

15. Robert T. Sidebottom November 15, 1995 Mary Sidebottom.

16. Anthony Joe Larette November 29, 1995 Mary Fleming

17. Robert Earl O'Neal December 6, 1995 Arthur Dale.

18. Jeffrey Paul Sloan February 21, 1996 Jason Sloan

19. Doyle James Williams April 10, 1996 A. H. Domann

20. Emmett Clifton Nave July 31, 1996 Geneva Roling

21. Thomas Henry Battle August 7, 1996 Birdie Johnson

22. Richard Oxford August 21, 1996 Harold Wampler and Melba Wampler

23. Richard Steven Zeitvogel December 11, 1996 Gary Wayne Dew

24. Eric Adam Schneider January 29, 1997 Richard Schwendeman and Ronald Thompson

25. Ralph Cecil Feltrop August 6, 1997 Barbara Ann Roam

26. Donald Edward Reese August 13, 1997 James Watson, Christopher Griffith, John Buford, and Don Vanderlinden

27. Andrew Wessel Six August 20, 1997 Kathy Allen

28. Samuel Lee McDonald, Jr. September 24, 1997 Robert Jordan

29. Alan Jeffrey Bannister October 24, 1997 Darrell Ruestman

30. Reginald Love Powell February 25, 1998 Freddie Miller and Arthur Miller

31. Milton Vincent Griffin-El March 25, 1998 Jerome Redden

32. Glennon Paul Sweet April 22, 1998 Missouri State Trooper Russell Harper

33. Kelvin Shelby Malone January 13, 1999 William Parr (he was also sentenced to death by the state of California)

34. James Edward Rodden, Jr. February 24, 1999 Terry Trunnel and Joseph Arnold

35. Roy Michael Roberts March 10, 1999 Correctional officer Tom Jackson

36. Roy Ramsey, Jr. April 14, 1999 Garnett Ledford and Betty Ledford

37. Ralph E. Davis April 28, 1999 Susan Davis

38. Jessie Lee Wise May 26, 1999 Geraldine McDonald

39. Bruce Kilgore June 16, 1999 Marilyn Wilkins

40. Robert Allen Walls June 30, 1999 Fred Harmon

41. David R. Leisure September 1, 1999 James A. Michaels, Sr

42. James Henry Hampton March 22, 2000 Frances Keaton

43. Bart Leroy Hunter June 28, 2000 Mildred Hodges and Richard Hodges

44. Gary Lee Roll August 30, 2000 Sherry Scheper, Randy Scheper and Curtis Scheper

45. George Bernard Harris September 13, 2000 Stanley Willoughby

46. James Wilson Chambers November 15, 2000 Jerry Lee Oestricker Roger B. Wilson

47. Stanley Dewaine Lingar February 7, 2001 Thomas Scott Allen

48. Tomas Grant Ervin March 28, 2001 Mildred Hodges and Richard Hodges

49. Mose Young, Jr. April 25, 2001 Kent Bicknese, James Schneider and Sol Marks

50. Samuel D. Smith May 23, 2001 Marlin May

51. Jerome Mallett July 11, 2001 Missouri State Trooper James F. Froemsdorf

52. Michael S. Roberts October 3, 2001 Mary L. Taylor

53. Stephen K. Johns October 24, 2001 Donald Voepel

54. James R. Johnson January 9, 2002 Deputy Sheriff Leslie B. Roark, Pam Jones, Charles Smith, Sandra Wilson

55. Michael I. Owsley February 6, 2002 Elvin Iverson

56. Jeffrey Lane Tokar March 6, 2002 Johnny Douglass

57. Paul W. Kreutzer April 10, 2002 Louise Hemphill

58. Daniel Anthony Basile August 14, 2002 Elizabeth DeCaro

59. William Robert Jones, Jr. November 20, 2002 Stanley Albert

60. Kenneth Kenley February 5, 2003 Ronald Felts

61. John Clayton Smith October 29, 2003 Brandie Kearnes and Wayne Hoewing

62. Stanley L. Hall March 16, 2005 Barbara Jo Wood

63. Donald Jones April 27, 2005 Dorothy Knuckles

64. Vernon Brown May 17, 2005 Janet Perkins Synetta Ford

65. Timothy L. Johnston August 31, 2005 Nancy Johnston

66. Marlin Gray October 26, 2005 Julie Kerry and Robin Kerry

67. Dennis James Skillicorn May 20, 2009 Richard Drummond

68. Martin C. Link February 9, 2011 Elissa Self

69. Joseph Paul Franklin November 20, 2013 Gerald Gordon

70. Allen L. Nicklasson December 11, 2013 Richard Drummond

71. Herbert L. Smulls January 29, 2014 Stephen Honickman

72. Michael Anthony Taylor February 26, 2014 Ann Harrison

73. Jeffrey R. Ferguson March 26, 2014 Kelli Hall

74. William Rousan April 23, 2014 Charles and Grace Lewis

75. John Winfield June 18, 2014 Shawnee Murphy and Arthea Sanders

76. John Middleton July 16, 2014 Randy "Happy" Hamilton, Stacey Hodge, Alfred Pinegar

77. Michael Shane Worthington August 6, 2014 Melinda “Mindy” Griffin

State v. Worthington, 8 S.W.3d 83 (Mo. 1999). (Direct Appeal)

Defendant was convicted pursuant to guilty plea in the Circuit Court, St. Charles County, Grace M. Nichols, J., of first-degree murder, first-degree burglary, and forcible rape, and was sentenced to death for the murder. Defendant appealed. The Supreme Court, Wolff, J., held that: (1) there was evidence beyond a reasonable doubt that defendant committed first-degree murder for monetary gain and that it occurred during perpetration of forcible rape and burglary, to support imposition of death sentence based on either of these two aggravating circumstances in light of all the evidence; (2) any failure of state to give notice that it intended to introduce, during penalty phase, evidence of defendant's prior bad conduct was not prejudicial to defendant; (3) defendant was precluded from complaining that he was compelled to testify against himself and that he was denied his right to counsel by introduction of psychologist's statements into evidence; and (4) defendant's affirmative response to questions by the plea court as to whether he understood the charges and elements thereof was sufficient to show that his guilty plea to charge of first-degree murder was informed and voluntary. Affirmed.

MICHAEL A. WOLFF, Judge.

Michael S. Worthington pleaded guilty on August 28, 1998, to one count of first degree murder, one count of first degree burglary, and one count of forcible rape. After finding him to be a prior and persistent offender, the court sentenced Worthington to death for the murder charge, 30 years on the burglary charge, and life imprisonment on the forcible rape charge, to be served consecutively. Because the trial court imposed the death penalty, this Court has jurisdiction of his appeal. Mo. Const. art. V, sec. 3. Ordinarily, appellate review of guilty pleas is extremely narrow. However, Sec. 565.035.2 FN1 requires this Court in death penalty cases to consider the punishment and “any errors enumerated by way of appeal.” We affirm. FN1. References to statutes are to RSMo 1994 unless otherwise noted.

Facts

On September 29, 1995, appellant, Worthington, and a friend from work, Jill Morehead, were at his condominium in Lake St. Louis, watching television. At about 4:00 p.m., they left to pick up their paychecks from their employer, a local supermarket. They returned to the condo and had dinner and drinks. They then went to a nightclub where each had three drinks. After about two hours, Worthington and Morehead drove to Jennings where Worthington told Morehead he had to pick up money owed to him by a friend. Worthington testified he actually went to pick up drugs. Morehead stayed in her vehicle, while Worthington was in the house for about 15 minutes. They drove back to his condo where he left Morehead. Morehead left the condo when Worthington did not return after about 45 minutes.

Later that night, Worthington saw that the kitchen window was open in the condominium of his neighbor, Melinda Griffin. Worthington had seen Ms. Griffin around the condominium complex. He got a razor blade and gloves, and when he returned to her condo, he saw that a bathroom light had been turned on. Worthington cut through the screen. He confronted Ms. Griffin in the bedroom. He covered her mouth to stop her screams and strangled her until she became unconscious. Worthington began to rape her and she regained consciousness. Worthington raped Ms. Griffin with such force that he bruised the inside of her vagina, tore both labia minora, and made a large, deep tear between her vagina and anus. Ms. Griffin fought Worthington, and he beat her and strangled her to death. The wounds on her neck showed that Worthington used a rope or cord in addition to his hands to strangle her. He stole her jewelry, credit cards, mobile phone, keys, and her car.

The next morning, September 30, 1995, a police officer pulled Worthington over. Worthington was driving Ms. Griffin's car. The officer noticed a woman's items in the car such as make-up and shoes, but the car had not been reported stolen. The next day, October 1, a neighbor discovered Ms. Griffin's body. When police arrived, they found the screen in the kitchen window had been cut to gain entry. They found Ms. Griffin's body lying bruised, bloody, and naked at the foot of the bed, with a lace stocking draped across it. All the bedroom drawers had been pulled open. DNA testing later established that semen found on Ms. Griffin's body came from Worthington. Police officers found Worthington that evening, but when he saw the police, he pulled out a knife, held it to his throat, and threatened to commit suicide. Police officers convinced him to put the knife down and brought him into custody. Worthington was wearing a fanny pack containing jewelry and keys belonging to Ms. Griffin.

At the police station, Worthington relayed his story of four days of drinking and getting high. After being presented with the evidence against him, Worthington confessed to the killing but could not remember the details since, he said, he was prone to blackouts when using alcohol and cocaine. At the time the offenses occurred, Worthington said he was extremely high on Prozac, cocaine, marijuana, and alcohol. Worthington also said that two friends, Darick and Anthony, helped him with the burglary. However, this story was inconsistent with the physical evidence and with subsequent statements made by Worthington. Worthington pleaded guilty to the crimes charged. The judge imposed the death penalty for the murder conviction, as well as the prison terms for the other offenses. Worthington does not challenge the plea and sentences on the other offenses; his appeal here concerns only the death penalty.

Was the Death Sentence Disproportionate?

Worthington contends that the trial court erred in that: (1) the statutory aggravating circumstances found by the trial court were unconstitutional because they were duplicative and did not narrow the class of persons eligible for the death penalty, (2) the trial court did not consider evidence that supported statutory mitigating circumstances, and (3) the victim impact evidence was improper. Worthington also contends that his sentence is disproportionate to similar cases.

(1) Are the Statutory Aggravating Circumstances Unconstitutional?

a. Are Statutory Aggravating Circumstances Duplicative?

Defense counsel did not attack the constitutionality of the statutory aggravating circumstances; therefore, the issue is not subject to review except for plain error. State v. Tokar, 918 S.W.2d 753, 769–70 (Mo. banc 1996), cert. denied, 519 U.S. 933, 117 S.Ct. 307, 136 L.Ed.2d 224 (1996). In this appeal, Worthington requests plain error review on numerous points. Under the plain error rule, “Appellant must make a demonstration that manifest injustice or a miscarriage of justice will occur if the error is not corrected.” Id. Worthington contends that the state submitted “in the course of a felony” aggravating circumstance as two circumstances and as such it is duplicative. This allowed the judge to count the same conduct twice and, therefore, the balance between aggravating and mitigating circumstances was skewed toward death.

Under section 565.032, in cases where the death penalty is imposed, the jury, or in this case where the jury is waived, the judge must determine whether a statutory aggravating circumstance is established beyond a reasonable doubt. Where there is a finding of one valid aggravating circumstance beyond a reasonable doubt, we will affirm the death sentence. State v. Jones, 979 S.W.2d 171, 185 (Mo. banc 1998), cert. denied, 525 U.S. 1112, 119 S.Ct. 886, 142 L.Ed.2d 785 (1999); State v. Smith, 944 S.W.2d 901, 921 (Mo. banc 1997), cert. denied, 522 U.S. 954, 118 S.Ct. 377, 139 L.Ed.2d 294 (1997). Here, the judge found two statutory aggravating circumstances beyond a reasonable doubt, and the record supports these findings: (1) Worthington committed the offense of murder for the purpose of receiving money or any other thing of monetary value from the victim of the murder, and (2) the murder was committed while Worthington was engaged in the perpetration of forcible rape and burglary. See section 565.032.2(4)(11). Appellant stated at his guilty plea hearing that he murdered Ms. Griffin while in the process of burglarizing her house and raping her, and that he took her money and other property afterward. Other evidence of these findings includes: Worthington was pulled over by a police officer while driving Ms. Griffin's car. He was wearing a fanny pack containing Ms. Griffin's jewelry and credit cards at the time of his arrest. Further, Ms. Griffin had been violently raped and Worthington's DNA matched that of the semen found on her body.

The finding of a statutory aggravating circumstance serves the purpose of determining which defendants are eligible for the death penalty. Tokar, 918 S.W.2d at 771. See also, State v. Brooks, 960 S.W.2d 479, 497 (Mo. banc 1997), cert. denied, 524 U.S. 957, 118 S.Ct. 2379, 141 L.Ed.2d 746 (1998). Once the judge finds at least one aggravating circumstance beyond a reasonable doubt, then the judge can decide whether to impose the death penalty. Id. At this point, the judge no longer considers individual statutory aggravating circumstances but, rather, “all the evidence” in aggravation or mitigation of punishment in order to determine whether to sentence the defendant to death. Section 565.032.1(2); State v. Shaw, 636 S.W.2d 667 (Mo. banc 1982), cert. denied, 459 U.S. 928, 103 S.Ct. 239, 74 L.Ed.2d 188 (1982). State v. Morrow, 968 S.W.2d 100, 116–117 (Mo. banc 1998), cert. denied, 525 U.S. 896, 119 S.Ct. 222, 142 L.Ed.2d 182 (1998); State v. Clemons, 946 S.W.2d 206, 232 (Mo. banc 1997), cert. denied, 522 U.S. 968, 118 S.Ct. 416, 139 L.Ed.2d 318 (1997); State v. Hall, 955 S.W.2d 198, 209 (Mo. banc 1997), cert. denied, 523 U.S. 1053, 118 S.Ct. 1375, 140 L.Ed.2d 523 (1998). Here, the judge found at least one statutory aggravating circumstance, and that is sufficient to support imposition of the death penalty, if after reviewing all of the evidence, the judge determines that is the appropriate punishment.

b. Do Statutory Aggravating Circumstances Fail to Narrow Class to which They Apply?

Worthington contends that the duplication of the statutory aggravating factors did not channel and limit the judge's discretion to minimize the risk of arbitrary and capricious sentencing, relying on Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238, 92 S.Ct. 2726, 33 L.Ed.2d 346 (1972). We have already addressed the duplication issue above, noting that Missouri weighs all the evidence to determine if the death penalty is an appropriate sentence, thus minimizing the risk of capriciousness. The record supports both aggravating circumstances found by the judge.

In addition, Worthington contends there does not exist a principled means to distinguish those who are made subject to the death penalty from those who are not. He essentially claims that his crime is no different than felony murder in which death would not be imposed. We disagree. Felony murder is distinguishable in that felony murder does not require deliberation. Section 565.021.1(2). Further, Worthington pleaded guilty and was sentenced by a judge, thus the judge properly considered in the sentencing phase the aggravating circumstance of murder during a robbery. See State v. Hunter, 840 S.W.2d 850 (Mo. banc 1992), cert. denied, 509 U.S. 926, 113 S.Ct. 3047, 125 L.Ed.2d 732 (1993). For a statutory aggravating circumstance to narrow the class of persons to whom the death penalty may be applied, that circumstance must satisfy two tests: (1) it may not apply to every defendant convicted of murder, and (2) the circumstance must not be unconstitutionally vague. Tuilaepa v. California, 512 U.S. 967, 972, 114 S.Ct. 2630, 129 L.Ed.2d 750 (1994). Here, Worthington does not assert that the aggravating circumstance applies to all who commit murder, since not all murderers kill for money or while committing rape. Moreover, Worthington does not assert that the aggravating circumstance was vague. His argument fails.

(2) Were the Mitigating Circumstances Ignored?

Worthington contends that the trial court's findings were erroneous because they were against the weight of the evidence and the court did not follow the law since the judge did not consider the statutory mitigating circumstances submitted and supported by the evidence. Worthington presented the following as mitigating circumstances pursuant to subsection 3 of section 565.032:(1) the murder was committed while the defendant was under the influence of extreme mental or emotional disturbance; (2) the defendant acted under extreme duress; (3) the defendant's age at the time of the offense; and (4) his capacity was substantially impaired due to drug and alcohol intoxication. Evidence presented supporting these factors was that he was 24 years old at the time he committed the offense, and he testified that he drank all day, went to a bar with a friend, and took drugs. He testified that his friends, Anthony and Darick, proposed the burglary. Worthington also presented non-statutory mitigating circumstances that he was abused and neglected as a child and he suffers from chemical dependency. The record does not support Worthington's contention that the trial judge did not consider the mitigating factors:

THE COURT: ... The Court has considered all of the non-statutory mitigating circumstances and factors that have been offered to this court, and any other facts or circumstances which may be found from the evidence presented, and finds that defendant was raised in a dysfunctional family, and was neglected and abused as a child and further, that the defendant is a long-term drug abuser. Having considered all of the evidence and the aggravating and mitigating circumstances, the Court finds beyond a reasonable doubt that the aggravating circumstances outweigh the non-statutory mitigating circumstances ... While the judge's comment quoted above does not mention statutory mitigating circumstances, it is clear from the entire record that the trial court did consider all of the evidence in imposing the death penalty. Worthington's claim is without merit.

(3) Was the Victim Impact Evidence Improper?

Worthington contends the victim impact evidence was unduly inflammatory and violated his state and federal constitutional rights to due process, to a fundamentally fair trial to confront the witnesses against him, and to be free from cruel and unusual punishment. No objection was raised regarding this evidence and plain error review is requested.FN2 Rule 30.20. FN2. During this phase, defense counsel recited “no objection” to all of the exhibits and the majority of the testimony. Counsel did object three times to testimony that showed a preference for or recommended death. One of the statements objected to and preserved for review was “I believe this man has caused enough chaos and I ask he be fairly punished for what he has done.” This does not recommend a specific sentence. The trial court did not abuse its discretion in overruling the objection. See State v. Roll, 942 S.W.2d 370 (Mo. banc 1997), cert. denied, 522 U.S. 954, 118 S.Ct. 378, 139 L.Ed.2d 295 (1997) (Judges presumed not to consider improper evidence when sentencing a defendant, thus Roll failed to show prejudice that constituted fundamental unfairness.) The other two objections were sustained by the trial court and not considered in sentencing. We disagree with Worthington that the evidence violated his constitutional rights by being unduly prejudicial. See Payne v. Tennessee, 501 U.S. 808, 111 S.Ct. 2597, 115 L.Ed.2d 720 (1991); State v. Roberts, 948 S.W.2d 577, cert. denied, 522 U.S. 1056, 118 S.Ct. 711, 139 L.Ed.2d 652 (1998).

Victim impact evidence is designed to show each victim's uniqueness as an individual human being. It is simply another form or method of informing the court about the specific harm caused by the crime in question, evidence of a general type long considered by sentencing authorities. See Payne and Roberts, supra; State v. Knese, 985 S.W.2d 759 (Mo. banc 1999), cert. denied, 526 U.S. 1136, 119 S.Ct. 1814, 143 L.Ed.2d 1017 (1999). During the penalty phase, thirteen witnesses FN3 read prepared statements and asked that a message be sent to the community and that “justice” be served through the sentence imposed. Pictures of Ms. Griffin and her family, as well as awards and other evidence about her life were introduced at the hearing. This Court has rejected the notion that the state is only allowed to present a “brief glimpse” of the victim's life. State v. Knese, 985 S.W.2d 759. No manifest injustice occurred in allowing the judge, who was sentencing Worthington, to hear this victim impact evidence. FN3. Two witnesses had prepared statements read to the judge by Ms. Griffin's mother.

Was Worthington Prejudiced by a Debler Violation?

Worthington contends that the state did not give notice to the defense that it intended to introduce evidence of his bad conduct in jail; his behavior in school; his burglaries with his father; misconduct with friends and associates and evidence from a Ms. Peroti of an alleged sexual assault, theft of her car, and assault of her son as evidence of non-statutory aggravating circumstances. The issue was not properly preserved for review, thus plain error review is requested.FN4 Rule 30.20. FN4. Worthington contends that he specifically objected to some of the evidence being introduced and requests plain error review for the remainder. The record does not reflect a specific objection based on lack of notice. See Thomas v. Wade, 361 S.W.2d 671 (Mo. banc 1962) (unless there is a specific objection to evidence which contains proper ground for its exclusion, nothing is preserved for review).

In general, both the state and the defense are allowed to introduce evidence regarding “any aspect of defendant's character.” State v. Debler, 856 S.W.2d 641 (Mo. banc 1993). The decision to impose the death penalty, whether by a jury or a judge, is the most serious decision society makes about an individual, and the decision-maker is entitled to any evidence that assists in that determination. Id. at 656. This Court has interpreted Debler to mean that evidence of non-conviction misconduct is inadmissible where the state does not provide the defendant with notice that it intends to introduce the evidence. See State v. Ervin, 979 S.W.2d 149 (Mo. banc 1998); State v. Kreutzer, 928 S.W.2d 854 (Mo. banc 1996), cert. denied, 519 U.S. 1083, 117 S.Ct. 752, 136 L.Ed.2d 689 (1997); State v. Chambers, 891 S.W.2d 93 (Mo. banc 1994).

From the Debler line of cases, the failure of the state to provide notice of this evidence is error. However, the question remains whether the lack of notice and the admission of this evidence was plain error constituting manifest injustice. See State v. Thompson, 985 S.W.2d 779 (Mo. banc 1999). Under the totality of circumstances surrounding this evidence, the prejudice that would arise from such evidence as explained in Debler does not exist in this case.FN5 Worthington pleaded guilty to these crimes and a judge determined Worthington's sentence. See State v. Roll, 942 S.W.2d 370 (Mo. banc 1997), cert. denied, 522 U.S. 954, 118 S.Ct. 378, 139 L.Ed.2d 295 (1997). Additionally, the record reflects that defense counsel stipulated to the evidence admitted, except for the testimony of Ms. Peroti. As to Ms. Peroti's testimony, the state had endorsed her two years before the penalty phase. Defense counsel was prepared to cross-examine her on the details of her failure to report the burglary and assault to police. Absent objection, there is no basis under a plain error analysis for concluding that the admission of the evidence was prejudicial to Worthington.

FN5. The potential for prejudice that exists, without the notice required by Debler, is that since “no jury or judge has previously determined a defendant's guilt for uncharged criminal activity, such evidence is significantly less reliable than evidence related to prior convictions. To the average juror, however, unconvicted criminal activity is practically indistinguishable from criminal activity resulting in convictions, and a different species from other character evidence.” Id. at 65 7.

Chapter 552 Examination Used to Prove Aggravating Circumstances

Worthington contends the trial court committed plain error in letting the state use his statements to Dr. Max Givon, made during a chapter 552 competency evaluation, to prove the statutory aggravating circumstances. He also claims that the admission of his statement violated his right to remain silent and his right to an attorney. Dr. Givon's report and testimony were stipulated to at trial. Thus, plain error review is requested.

Dr. Givon's Testimony Used to Prove Statutory Aggravating Circumstances

Worthington fails to demonstrate manifest injustice or a miscarriage of justice by the admission of Dr. Givon's testimony. Dr. Givon, a psychologist, evaluated Worthington to determine if he was competent to stand trial and to assist his attorney and to determine if he suffered from a mental disease or defect. He diagnosed appellant as cocaine and alcohol dependent and as having anti-social personality disorder. Dr. Givon also said Worthington was malingering, which is the intentional production of false or grossly exaggerated psychological or physical symptoms for an external reward. Missouri statutes divide the guilt phase of trial from the penalty phase of trial in order to allow the admission of all relevant evidence in the penalty phase without fear of prejudicing the defendant in the guilt phase. Section 565.030.2.FN6 Here, Worthington's guilt had already been established. Although Dr. Givon's diagnosis may have been internally inconsistent and his examination perhaps not as thorough as the other doctors who had previously seen Worthington, it was not plain error for the court to allow it as evidence during the penalty phase. See State v. Copeland, 928 S.W.2d 828, 839 (Mo. banc 1996), cert. denied, 519 U.S. 1126, 117 S.Ct. 981, 136 L.Ed.2d 864 (1997). FN6. The distinction between the guilt phase and penalty phase is observed in section 552.020.14, RSMo Supp.1997, which provides as follows: No statement made by the accused in the course of any examination or treatment pursuant to this section and no information received by any examiner or other person in the course thereof, whether such examination or treatment was made with or without the consent of the accused or upon his motion or upon that of others, shall be admitted in evidence against the accused on the issue of guilt in any criminal proceeding then or thereafter pending in court, state or federal. (emphasis added).

Did Use of Statements Violate the Right to Remain Silent and Right to Counsel?

Worthington claims that the admission of his statements to Dr. Givon violated his right to remain silent and his right to an attorney, relying on Estelle v. Smith, 451 U.S. 454, 101 S.Ct. 1866, 68 L.Ed.2d 359 (1981). This reliance is misplaced. Estelle stands for the proposition that a “criminal defendant who neither initiates a psychiatric evaluation nor attempts to introduce any psychiatric evidence may not be compelled to respond to a psychiatrist if his statements can be used against him at a capital sentencing proceeding.” 451 U.S. at 468, 101 S.Ct. 1866; State v. Copeland, 928 S.W.2d at 839. Here, Worthington, through counsel, requested the evaluation pursuant to section 552.020 and put his mental condition in controversy. Thus, since Worthington initiated the examination, he was not compelled to testify against himself, nor was his right to counsel violated.

Guilty Plea Did Not Extinguish Right to Remain Silent FN7

FN7. Worthington is correct in noting that under Mitchell v. United States, 526 U.S. 314, 119 S.Ct. 1307, 143 L.Ed.2d 424 (1999), a defendant who pleads guilty does not waive his rights against self-incrimination as to sentencing, but the transcript does not reflect whether this was the judge's basis in overruling the motion in limine. The transcript reflects defense counsel correctly presented the court with the correct rule of law. In any event, the basis for a trial court's decision is not critical on appeal. See State v. Bradley, 811 S.W.2d 379, 383 (Mo. banc 1991).

Worthington contends that the trial court erred in overruling the defense motion in limine to preclude the state from exceeding the scope of his proposed direct examination. The trial court ruled that if Worthington chose to testify he would be subject to full cross-examination. Worthington did not take the stand during the penalty phase.

Here, Worthington wanted to testify and limit his examination to “his sorrowness, his remorse and his apology to the family” and the feelings he had upon hearing the victim impact evidence. Defense counsel asked the court to limit the scope of cross-examination to those issues only and specifically not let the state examine him on his background or the circumstances of the homicide itself.FN8 The scope of cross-examination of a criminal defendant (and spouse) is limited to those matters elicited on direct examination. Section 546.260; State v. Gardner, 8 S.W.3d 66 (Mo. banc 1999), (discussing rule for non-defendant witnesses). This Court has long held that cross-examination of a criminal defendant “need not be confined to a categorical review of the matters stated in direct examination, but may cover any matter within the fair purview of the direct examination.” State v. Knese, 985 S.W.2d at 770.FN9 A defendant, in a single proceeding, may not testify voluntarily about a subject and then invoke a privilege against self-incrimination when questioned about the details. Mitchell v. U.S., 526 U.S. 314, 119 S.Ct. 1307, 1311–12, 143 L.Ed.2d 424 (1999). The scope of cross-examination is a matter primarily within the trial court's discretion. State v. Knese, supra, at 770. Here, the circumstances of the crime would be relevant to determine the appropriate punishment.

FN8. The transcript reflects that defense counsel noted that Worthington's decision to testify was against his advice, “knowing the scope of cross-examination of my client.” FN9. See also, State v. Barnett, 980 S.W.2d 297, 307 (Mo. banc 1998); State v. Gray, 887 S.W.2d 369, 386 (Mo. banc 1994); State v. Mayo, 487 S.W.2d 539, 540 (Mo.1972); State v. Harvey, 449 S.W.2d 649, 652 (Mo.1970); State v. Dalton, 433 S.W.2d 562, 564 (Mo.1968); State v. Moser, 423 S.W.2d 804, 806 (Mo.1968); State v. Scown, 312 S.W.2d 782, 786–87 (Mo.1958); State v. Brown, 312 S.W.2d 818, 821 (Mo.1958); State v. Hartwell, 293 S.W.2d 313, 317 (Mo.1956); State v. Dill, 282 S.W.2d 456, 463 (Mo.1955); State v. Shilkett, 356 Mo. 1081, 204 S.W.2d 920, 924 (1947); State v. Tull, 333 Mo. 152, 62 S.W.2d 389, 393 (1933); State v. Glazebrook, 242 S.W. 928, 931 (Mo.1922); State v. Cole, 213 S.W. 110, 113 (Mo.1919).

Knowing, Intelligent and Voluntary Plea: Were the Warnings Defective?

Worthington asserts that his guilty plea was unknowing, unintelligent and involuntary because he was not informed of the meaning of deliberation, his possible defenses and range of punishment. He specifically argues that there was no record evidence that he was aware of the meaning of “deliberation,” an essential element of the offense of first-degree murder. While the record does not contain detailed explanations, the record does not support Worthington's contention that he was uninformed or that his plea was involuntary.

Court: Has your attorney explained to you the nature of each charge and any lesser included charges, and also the possible defenses you might have in this case? Worthington: Yes, ma‘am. Court: Have you had adequate opportunity to consult with them both as to the charge and effect of entering a plea of guilty to the charge? Worthington: Yes, ma‘am.... Court: Okay. Are you suffering from any mental disease or defect other than what you have just testified to? Worthington: No, ma‘am. Court: Are you mentally prepared to proceed with proposed plea of guilty? Worthington: Yes, ma‘am. Court: At the time of the crimes with which you are charged, did you know the difference between right and wrong? Worthington: Yes, ma‘am.... Court: Have you discussed the nature of the charges and the essential elements of the charges with the defendant? Mr. Rosenblum: Yes. Court: Mr. Worthington, do you understand the nature and essential elements of each and every charge to which you are entering a plea of guilty? Worthington: Yes, ma‘am.... Court: Have you been forced, threatened or coerced in any way to induce you to plead guilty? Worthington: No, ma‘am. Court: Are you entering you plea of guilty here today freely and voluntarily on your part? Worthington: Yes, ma‘am.

Worthington's reliance on Wilkins v. Bowersox, 145 F.3d 1006 (8 th Cir.1998), cert. denied, 525 U.S. 1094, 119 S.Ct. 852, 142 L.Ed.2d 705 (1999), is misplaced. Wilkins concerns whether a defendant voluntarily waived his right to counsel. The court must inquire whether a defendant is competent to proceed pro se, and part of the inquiry is whether the defendant understands the nature of the charges, lesser included offenses, the range of punishment, and possible defenses to the charge. State v. Funke, 903 S.W.2d 240, 243 (Mo.App.1995). Neither the federal nor state constitution requires the plea court to define legal words used in the court's questions and statements. State v. Shafer, 969 S.W.2d 719, 732 (Mo. banc 1998), cert. denied, 525 U.S. 969, 119 S.Ct. 419, 142 L.Ed.2d 340. The court is not required to discuss in detail all possible defenses, lesser included offenses, and ranges of punishment before accepting a guilty plea when a defendant is represented by counsel. This is required of the court in pro se proceedings but only because there is no counsel to explain the charges, offenses, and punishment to the defendant. The record reflects that the court asked Worthington if he had understood the charges and elements thereof and he responded in the affirmative. In the circumstances, the information given to Worthington was adequate.

Proportionality of Sentence

Although not constitutionally required, section 565.035.3 requires this Court to conduct an independent review of a defendant's death sentence. The Court must decide whether the death sentence is excessive and disproportionate to other similar cases, whether the evidence supports the judge's findings of an aggravating circumstance, and whether the sentence was not imposed under the influence of passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor.

After careful review of the record and transcript, this Court finds that the sentence of death imposed on Mr. Worthington was not imposed under the influence of passion, prejudice or any other arbitrary factor. In this case, the judge found two aggravating circumstances: 1) murder for monetary gain, and 2) murder in perpetration of forcible rape. The evidence, particularly Worthington's own words, supports the findings. Considering the crime, the strength of the evidence, and the defendant, this Court finds the facts of this case are consistent with death sentences affirmed wherein victims were murdered in course of a robbery and murdered in perpetrating a rape. See State v. Knese, 985 S.W.2d 759, cert. denied, 526 U.S. 1136, 119 S.Ct. 1814, 143 L.Ed.2d 1017 (1999); State v. Clemons, 946 S.W.2d 206, 233 (Mo. banc 1997), cert. denied, 522 U.S. 968, 118 S.Ct. 416, 139 L.Ed.2d 318 (1997); State v. Kinder, 942 S.W.2d 313 (Mo. banc 1996), cert. denied, 522 U.S. 854, 118 S.Ct. 149, 139 L.Ed.2d 95 (1997); State v. Tokar, 918 S.W.2d 753 (Mo. banc 1996) cert. denied, 519 U.S. 933, 117 S.Ct. 307, 136 L.Ed.2d 224 (1996); State v. Copeland, 928 S.W.2d 828 (Mo. banc 1996) cert. denied, 519 U.S. 1126, 117 S.Ct. 981, 136 L.Ed.2d 864 (1997); and State v. Kreutzer, 928 S.W.2d 854 (Mo. banc 1996), cert. denied, 519 U.S. 1083, 117 S.Ct. 752, 136 L.Ed.2d 689 (1997). At the time Worthington entered his plea on the murder charge, he knew that the death penalty was one of only two options available to the trial judge—a sentence of death or life imprisonment without parole. There is nothing in the record to support the notion that the trial judge's choice was improper or inappropriate under the law. The judgment of the trial court is affirmed. All concur.

Worthington v. State, 166 S.W.3d 566 (Mo. 2005). (PCR)