Executed October 21, 2010 06:21 p.m. CDT by Lethal Injection in Texas

43rd murderer executed in U.S. in 2010

1231st murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

17th murderer executed in Texas in 2010

464th murderer executed in Texas since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(43) |

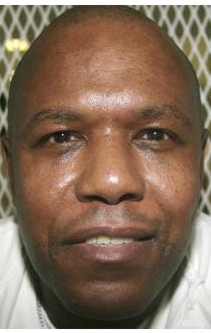

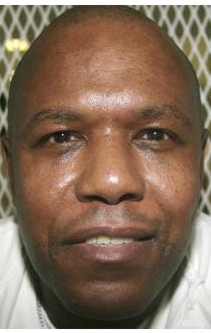

Larry Wayne Wooten B / M / 37 - 51 |

Grady Alexander B / M / 80 Bessie Alexander B / F / 86 |

Citations:

Wooten v. Thaler, 598 F.3d 215 (5th Cir. 2010). (Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

10 fried chicken legs, 10 chicken wings, mashed potatoes, greens, rice pudding, tea (very sweet) and banana pudding.

Last Words:

"I don't have nothing to say. You can go ahead and send me home to my heavenly father."

Internet Sources:

Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Executed Offenders (Wooten)

Wooten, Larry

Date of Birth: 12/10/58

DR#: 999269

Date Received: 5/21/98

Education: 12 years

Occupation: Building Maintenance

Date of Offense: 9/3/96

County of Offense: Lamar

Native County: Lamar

Race: Black

Gender: Male

Hair Color: Black

Eye Color: Brown

Height: 5' 05"

Weight: 183

Prior Prison Record: TDCJ #603454, received on 12/17/91 from Lamar County on a 12 year sentence for robbery; paroled 6/3/94.

Summary of incident: On September 3, 1996, Wooten murdered an 80-year-old black male and his 86-year-old wife. Wooten stabbed the victims and cut their throats. Also, the female victim was beaten with a pistol with such force that the grips and portions of the trigger mechanism of the pistol broke off. Wooten then robbed the couple of $500.00 to $600.00 in cash.

Co-Defendants: None.

Thursday, October 14, 2010

Media Advisory:Larry Wooten scheduled for execution

AUSTIN – Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott offers the following information about Larry Wayne Wooten, who is scheduled to be executed after 6 p.m. on October 21, 2010. A Lamar County jury sentenced Wooten to death for the 1996 murders of Grady and Bessie Alexander.

FACTS OF THE CRIME

On September 3, 1996, eighty-year-old Grady Alexander and his wife Bessie, eighty-six, were found dead in their home. They each had been stabbed several times and their throats had been cut. Grady had been hit over the head with an iron skillet, and Bessie had been hit in the head with the butt of a gun. Both Grady and Bessie had defensive wounds as well.

Before their deaths, the Alexanders lived a quiet life but depended on others for help at home and on errands. Wooten was among those people who helped the Alexanders manage their day-to-day life.

A pair of Wooten’s pants were found covered with blood from Grady Alexander.

During the trial, the state presented evidence that Wooten knew the Alexanders. He had been invited into their home and had, at one time, been married to their niece Ruby Black, who explained that Wooten would do odd jobs for the Alexanders. A motive for the killings was provided when Ruby testified that the Alexanders always had a large sum of cash at home. Ruby told the jury that Wooten would sometimes spend his entire paycheck on cocaine. She also admitted that she had loaned him money that he turned around and spent on cocaine. It was for this reason that she stopped loaning Wooten money. Ruby also encouraged the Alexanders not to loan him any more money.

The State established that on the Sunday night after Wooten had savagely murdered the Alexanders, he went on a cocaine binge with a woman who testified that when she encountered Wooten, he was wearing blue-striped overalls and that he took a “wad of money” out of the front pocket of those overalls. She testified further that there was blood on the overalls, and Wooten had blood on his hands and fingernails.

THE PENALTY PHASE EVIDENCE

Wooten’s first conviction came in 1982, when he pled guilty to a charge a burglary of a habitation with intent to rape a seventy-three-year-old woman in her Paris, TX, home. Police found Wooten in the elderly woman’s bed, asleep and naked. His driver’s license was found in his wallet, allowing the police to identify him. For this crime, Wooten was placed on seven years probation.

Just two years later, on December 2, 1984, Wooten was arrested after fleeing from police, having tried to break into the same elderly woman’s home. An officer found Wooten had a martial arts knife. A search of the woman’s home revealed that the telephone line had been cut; a window screen had been cut up and pulled off and the window behind it had been broken; the back door had been pulled off its hinges. While being booked into jail, Wooten threatened to kill the arresting officers when he was released. Wooten pled guilty, and he was sentenced to ten years probation. Wooten’s probation was revoked, however, in 1991, when he pleaded guilty to robbery; he was sentenced to 10 years in prison.

The State also offered evidence that Wooten could be violent in his relationships with women.

The State ended its case with the testimony of a forensic psychiatrist who said that the Alexander murders were particularly disturbing because of Wooten’s wholesale failure to express any remorse, the “overkill,” and the fact that Wooten knew his victims. The psychiatrist also found Wooten’s history of “impulsive criminality” to be disturbing, as well that Wooten “hasn’t mellowed out with age” Based on this, and considering Wooten’s chronic substance abuse problems and the fact that he apparently had no desire to stop using cocaine, the doctor concluded that Wooten would indeed be a future danger to society, both in prison and in the free world.

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

7/29/97 – Wooten was indicted for capital murder in Lamar County.

5/5/98 – The jury found Wooten guilty of capital murder.

5/12/98 – After a separate penalty hearing, Wooten was sentenced to death.

1/9/02 – The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed Wooten’s verdict and sentence.

10/14/02 – The Texas Supreme Court denied Wooten’s petition for certiorari review.

11/8/99 – Wooten filed an application for state writ of habeas corpus.

4/3/02 – Texas Court of Criminal Appeals denied habeas relief in an unpublished order.

10/2/03 – Wooten filed second application for state writ of habeas corpus, alleging retardation.

1/21/04 – Texas Court of Criminal Appeals remanded Atkins claim back to trial court.

4/12/06 – Wooten’s Atkins claim was denied.

4/12/06 – Wooten filed his federal habeas corpus petition in a U.S. district court.

10/18/07 – The district court denied relief.

11/7/07 – Wooten appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

3/2/10 – The Fifth Circuit affirmed the federal district court’s denial of habeas relief.

7/12/10 – Wooten filed a petition for certiorari review in the United States Supreme Court.

10/4/10 – The Supreme Court denied Wooten’s petition for certiorari review.

6/28/10 – The trial court signed the order setting Wooten’s execution date for October 21, 2010.

Texas Execution Information Center by David Carson.

Larry Wayne Wooten, 51, was executed by lethal injection on 21 October 2010 in Huntsville, Texas for the murder and robbery of an elderly couple in their home.

Grady Alexander, 80, and his wife, Bessie, 86, lived at home in Paris, in northeast Texas, with the help of others who would do odd jobs and errands for them. One such person was Larry Wooten, who was at one point married to their niece, Ruby Black.

On 3 September 1996, Wooten, then 37, stabbed Grady and Bessie in their home and cut both of their throats. He also hit Grady over the head with an iron skillet and hit Bessie on the head with the butt of a pistol. He also stole $500 to $600 from the couple.

At the trial, the prosecution presented blood evidence found on the victims' kitchen floor. A DNA analysis showed that it was Wooten's blood. Grady Alexander's blood was also found on a pair of Wooten's pants. In addition to the physical evidence, the state presented testimony from a woman who said that on 8 September, she went on a cocaine binge with Wooten. She said when she met up with him, he removed a "wad of money" out of the front pocket of some overalls he was wearing, and that the overalls had blood on them. Wooten also had blood on his hands, she said. Ruby Black testified that Wooten sometimes spent his entire paycheck on cocaine. She said that she stopped loaning him money because he would immediately use it to buy cocaine. She also urged the Alexanders not to loan Wooten money.

Wooten had three prior felony convictions. In 1982, he broke into a 73-year-old woman's house. He pleaded guilty to burglary of a habitation with intent to rape, and was sentenced to seven years' probation. Two years later, he was arrested for trying to break into the same woman's home. He pleaded guilty again and served six months in prison, but then was released on shock probation. (At the time, early release was common in Texas due to strict prison population caps imposed by U.S. District Judge William Wayne Justice.)

In 1991, Wooten was arrested for robbery. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to ten years in prison. He received parole in June 1994 after serving 2˝ years of his sentence.

A jury convicted Wooten of capital murder in May 1998 and sentenced him to death. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the conviction and sentence in January 2002. All of his subsequent appeals in state and federal court were denied.

According to former Lamar County district attorney Kerye Ashmore, who prosecuted Wooten's case, Wooten was also a person of interest in the slaying of another elderly woman in Paris, who was killed a couple of weeks before the Alexanders.

In an interview from death row about a month before his execution, Wooten claimed that he did not kill the Alexanders. He said he went to their home and found their bodies, then fled. "If I call the cops, they'll think I done it. I walked away. I didn't tell anybody. I thought they would pin it on me, and that's exactly what they did." Wooten's execution was attended by his two sisters. No one from the Alexander family attended.

"I don't have nothing to say," Wooten said in his last statement. You can go ahead an send me home to my heavenly father." Wooten cried when the lethal injection was started. He was pronounced dead at 6:21 p.m.

"Inmate executed for slayings of elderly Paris couple," by Juan A. Lozano. (AP Oct. 21, 2010)

HUNTSVILLE — A Texas man convicted for the slayings of an elderly couple found brutally beaten and stabbed in their home more than 14 years ago was executed Thursday. Larry Wooten was condemned to death for the 1996 murders of 80-year-old Grady Alexander and his 86-year-old wife, Bessie, in the northeast Texas town of Paris.

The Alexanders were beaten with a cast-iron skillet and a pistol, stabbed and had their throats slit and heads almost severed. Prosecutors said Wooten robbed the couple, taking their savings of $500 so he could buy cocaine. Wooten was the 17th inmate executed this year in the nation's most active death penalty state.

During his brief final statement, Wooten, 51, did not mention the Alexanders. "I don't have nothing to say. You can go ahead and send me home to my heavenly father," Wooten said. He cried as the drugs were administered and let out one final gasp as the lethal injection took effect. Nine minutes later, at 6:21 p.m. CDT, he was pronounced dead.

No family members of the Alexanders attended the execution. Wooten's two sisters, who witnessed the execution, cried and prayed. Between 10 to 15 anti-death penalty protesters stood about a block away outside the prison that the execution chamber is housed in, with one woman using a bullhorn to say, "The state of Texas has committed another murder."

Wooten had maintained that he didn't kill the couple, for whom he formerly worked doing odd jobs. He claimed he went to their home in Paris, located about 105 miles northeast of Dallas, found the bodies and fled. Wooten had at one time been married to the couple's niece. DNA evidence, including blood found on the Alexanders' kitchen floor and matched to Wooten, helped convict him. A pair of Wooten's pants stained with Grady Alexander's blood also was found near an area where Wooten had bought drugs around the time of the murders.

Wooten's attorneys exhausted their appeals after the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles on Tuesday rejected a plea to commute his sentence to life in prison. Earlier this month, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to consider Wooten's appeal.

Kerye Ashmore, a former Lamar County district attorney who prosecuted the case, called Wooten a "scary guy" with a history of violence, including a prior conviction for assaulting an elderly woman after breaking into her home. He also was a person of interest in the slaying of another elderly woman in Paris who was killed a couple of weeks before the Alexanders, Ashmore said. "If you are going to have a death penalty, this is the kind of people you want to have the death penalty for," said Ashmore, who is now the first assistant district attorney in nearby Grayson County.

In his appeal to the Supreme Court, Wooten's attorneys argued he wouldn't have turned down a plea bargain if he knew about additional DNA evidence that didn't become available until after his trial began. Wooten had turned down a plea agreement of life in prison after DNA experts working for his trial attorneys believed the blood evidence didn't reliably connect him to the crime. But after the trial began, additional lab results showed the DNA evidence was stronger than originally thought, Wooten's appeals said. Ashmore said he never misrepresented the strength of the DNA evidence.

The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in March that both sides are at risk in a plea offer and there's no constitutional right to a plea bargain. In prior appeals, Wooten had claimed he should not be executed because he is mentally retarded. But his claim was denied as tests put his IQ between 77 and 84. An IQ of 70 is considered the threshold for mental impairment.

The next execution in Texas is scheduled for Dec. 1, when Steven Staley is set to die for the 1989 slaying of a Fort Worth restaurant manager during a robbery.

"Texas executes killer of elderly Paris couple," by Tommy Davis. (Thu Oct 21, 2010, 11:31 PM)

HUNTSVILLE — Texas executed a 51-year-old handyman Thursday who was convicted in the 1996 slayings of an elderly couple who once employed him. Larry Wooten was convicted of murdering Bessie, 86, and Grady Alexander, 80, with the help of blood and DNA evidence found on the couple’s kitchen floor.

On hand to witness the execution in the Texas Death House, located within the Walls Unit in central Huntsville, were Wooten’s two sisters and three friends. There were no witnesses present for the victims’ family.

Wooten’s last words were, “Warden, warden, warden? Where is the warden at? I have nothing to say so you can send me home to my heavenly father.” Larry Wooten was pronounced dead at 6:21 pm. Wooten had requested a last meal of 10 fried chicken legs, 10 chicken wings, mashed potatoes, greens, rice pudding, tea (very sweet) and banana pudding. Wooten was the 17th inmate executed this year in the nation's most active death penalty state.

Prosecutors said the Alexanders were beaten with a cast iron skillet and a pistol, stabbed and had their throats slit and heads almost severed. Wooten robbed the couple, taking their savings of $500, so he could buy cocaine, they said.

Wooten said he didn't kill the couple, for whom he formerly worked doing odd jobs. He claimed he went to their home in Paris, located about 105 miles northeast of Dallas, found the bodies and fled. Wooten had at one time been married to the couple's niece.

But DNA evidence, including blood found on the Alexanders' kitchen floor and matched to Wooten, helped convict him. A pair of Wooten's pants stained with Grady Alexander's blood also were found near an area where Wooten had bought drugs around the time of the murders.

The U.S. Supreme Court earlier this month refused to consider Wooten's appeal. On Tuesday, the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles rejected a plea to commute his sentence to life in prison.

Kerye Ashmore, a former Lamar County district attorney who prosecuted the case, called Wooten a "scary guy" with a history of violence, including a prior conviction for assaulting an elderly woman after breaking into her home. He also was a person of interest in the murder of another elderly woman in Paris who was killed a couple of weeks before the Alexanders, Ashmore said. "If you are going to have a death penalty, this is the kind of people you want to have the death penalty for," said Ashmore, now the first assistant district attorney in nearby Grayson County.

In his appeal to the Supreme Court, Wooten's attorneys argued he wouldn't have turned down a plea bargain if he knew about additional DNA evidence that didn't become available until after his trial began. Wooten turned down a plea agreement of life in prison after DNA experts working for his trial attorneys believed the blood evidence didn't reliably connect him to the crime. But after the trial began, additional lab results showed the DNA evidence was stronger than originally thought, Wooten's appeals said. Ashmore said he never misrepresented the strength of the DNA evidence.

In prior appeals, Wooten had claimed he should not be executed because he is mentally retarded. But his claim was denied as tests put his IQ between 77 and 84. An IQ of 70 is considered the threshold for mental impairment.

Larry W. Wooten #999269

Polunsky Unit D.R.

3872 FM 350 South

Livingston, Texas 77351 U.S.A.

LarryWooten@deathrow-texas.com for a first contact or with Jpay.com to send e-mails, please leave a postal address for response. Thank You

SMILE

13.07.2004

Hallo, how are you doing on this wonderful day?

My name is Mr. Larry W. Wooten. My age is 45 and birthday is December 10, 1958. I am a black man my height is 5 feet 5 inch tall. I am on death row. I have been on the row for 6 years. I would like to find a pen pal.

Would like to write to women colour do not matter. I do not have family. Help me in here. I hope I could find someone to talk to. I don’t want to write to a woman that is already writing to someone on death row. I am a down to earth person, open minded, love to love and would love to love a under woman. I am a Christian.

Thank you

Larry Wooten

August, 2004

....It’s said that many strive to take all they can from life. That’s epitomized by my current circumstances in life. It’s also said that it’s best to give all to life. That’s epitomized by compassion, love and friendship. Giving the best I can to life is something I strive daily to achieve although I am confined within the “halls of death”. Because ones body is simply a visible part of one’s soul. A very small and insignificant aspect that’s merely able to reach so far in the complete realm of life, where we truly exist; Mind, spirit and soul is what should matter; sadly this isn’t apparent to those whom cage my body. However I realize that with compassion, love and friendship they will be awaken, just as I am. Once they are, they’ll understand why and how day after day and year after year I open my eyes in a steal and concrete world and smile. Something that may appear so simple is what has kept me going while facing great adversity. And it’s what I would love to share with the world. I would greatly love if you, whoever you are, would allow us to share this small but great aspect of life. This experience would be cherishable for the both of us… do you agree? If so, take a moment to write me and allow us the opportunity of our lifetime…

Thank you and be blessed!

Mr. Larry W. Wooten #999269

On September 3, 1996, Larry Wayne Wooten murdered 80-year-old Grady Alexander and his 86-year-old wife Bessie by stabbing each several times and cutting their throats. Trial testimony revealed that Grady had been hit over the head with an iron skillet and beaten with the butt of a gun. Bessie was beaten with a pistol with such force that the grips and portions of the trigger mechanism of the pistol broke off. Both were nearly decapitated.

Motive for Wooten’s crime was to rob the couple of less than $600 in cash. The Alexanders lived a quiet life but depended on others for help at home and on errands. Wooten, who was one of the people who helped the couple manage their lives, knew they kept cash in their home testimony revealed. On the Sunday night after Wooten had savagely murdered the Alexanders, he went on a cocaine binge with a woman who testified that when she encountered Wooten, he was wearing blue-striped overalls and that he took a ‘wad of money’ out of the front pocket of those overalls. She testified further that there was blood on the overalls, and Wooten had blood on his hands and fingernails. DNA evidence matched to Wooten, including blood found on the couple's kitchen floor. Police recovered Wooten's overalls that were stained with Grady Alexander's blood.

Evidence in the penalty phase of the trial showed Wooten was violent towards women. In 1982, he pled guilty of trying to rape a 73-year-old woman in Paris, Texas. In 1984 he tried it again with the same woman. He was also a person of interest in the murder of another elderly woman in Paris who was killed a couple of weeks before the Alexanders. UPDATE: Larry Wooten was executed with no mention of his victims during his brief final statement.

Wooten v. Thaler, 598 F.3d 215 (5th Cir. 2010). (Habeas)

Background: Following affirmance of his capital murder conviction and imposition of a death sentence, and the denial of his petition for state habeas relief, 2006 WL 950381, state inmate petitioned in federal court for writ of habeas corpus. The United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas, Leonard E. Davis, J., 2007 WL 3037057, denied the request but granted a certificate of appealability (COA), and inmate appealed.

Holding: The Court of Appeals, Patrick E. Higginbotham, Circuit Judge, held that defendant was not deprived of his due process rights by State's unintended delay in producing the full weight of its DNA evidence. Affirmed.

PATRICK E. HIGGINBOTHAM, Circuit Judge:

Larry Wayne Wooten was convicted of capital murder in Texas and sentenced to death. After his conviction and sentence were affirmed on direct review, Wooten unsuccessfully sought state habeas relief. A federal district court also denied habeas relief in full, though it granted Wooten a certificate of appealability. He complains that late-arriving DNA evidence strengthened the state's case; that had he known of this evidence he would not have gone to trial. Now on appeal, we too find no constitutional infirmity and so AFFIRM the district court's denial of Wooten's petition.

I

The relevant facts are essentially undisputed. In 1997, a Texas state indictment charged Wooten with capital murder. Central to the state's case was DNA analysis of blood evidence found at the murder scene and elsewhere that would be-if reliable-virtually conclusive of guilt. The trial court directed the prosecution to turn over all DNA analysis and evidence in its possession. The prosecution furnished a preliminary DNA report to defense counsel in May 1997 and a further accounting of DNA evidence in January 1998. Defense counsel obtained their own experts who, on the basis of the evidence proffered thus far, believed the prosecution's DNA evidence unreliable. It was at this point that the prosecution presented Wooten's attorney with a plea deal: if Wooten pled guilty, he would receive a life sentence; if not, he would remain eligible for the death penalty. With his experts telling him that the prosecution's DNA analysis was faulty, Wooten rejected the offer and his case proceeded toward trial.

Once jury selection was under way, however, additional data emerged from the DNA laboratory, which made it clear that the laboratory had unintentionally failed to turn over all available DNA evidence. This late-coming data also revealed the prosecution's DNA evidence to be significantly more reliable than initially apparent. Wooten's counsel moved for a continuance to permit their experts time to complete their evaluation. The trial *218 court denied that motion, jury selection ended, and Wooten's trial began.

Defense counsel still assumed that they would be able to attack the veracity of the DNA evidence, albeit less convincingly. But, after opening statements were made and some witnesses were called, yet more evidence came in from the laboratory that suggested even that tempered strategy was probably misguided. The district court granted a twelve-day continuance to permit a full analysis by the defense experts. That analysis indicated that any apparent evidentiary flaws were illusory or had been corrected. The jury found Wooten guilty and he was sentenced to death.

Wooten's case and subsequent habeas petition worked their way through the state court, and we now review the district court's denial of his federal habeas petition. The district court granted a certificate of appealability to answer two questions: (1) whether Wooten's right to the due process of law was violated by his being unintentionally misled, at the time of his plea negotiations and trial preparation, into believing that the DNA evidence against him was not as strong as it turned out to be; and (2) whether defense counsel's being misled rendered their assistance constitutionally ineffective.

II

Wooten's federal habeas petition is subject to the heightened standard of review set forth in the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA). When reviewing state proceedings, AEDPA proscribes federal habeas relief unless the state court's adjudication on the merits (1) “resulted in a decision that was contrary to, or involved an unreasonable application of, clearly established federal law, as determined by the Supreme Court of the United States” or (2) “resulted in a decision that was based upon an unreasonable determination of the facts in light of the evidence presented in the state court proceeding.”FN1 We review the district court's findings of fact for clear error and its conclusions of law de novo, “applying the same standards to the state court's decision as did the district court.”FN2 “A state court decision is ‘contrary to ... clearly established precedent if the state court applies a rule that contradicts the governing law set forth in [the Supreme Court's] cases.’ ”FN3 “A state-court decision will also be contrary to ... clearly established precedent if the state court confronts a set of facts that are materially indistinguishable from a decision of [the Supreme Court] and nevertheless arrives at a result different from [Supreme Court] precedent.”FN4 “A state-court decision involves an unreasonable application of [Supreme Court] precedent if the state court identifies the correct governing legal rule from [the] Court's cases but unreasonably applies it to the facts of the particular state prisoner's case.” FN5 Finally, AEDPA requires us to presume state-court findings of fact to be correct “unless the petitioner rebuts that presumption by clear and convincing evidence.”FN6

FN1. 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d). FN2. Harrison v. Quarterman, 496 F.3d 419, 423 (5th Cir.2007). FN3. Wallace v. Quarterman, 516 F.3d 351, 354 (5th Cir.2008) (quoting Williams v. Taylor, 529 U.S. 362, 405, 120 S.Ct. 1495, 146 L.Ed.2d 389 (2000)) (addition in Wallace). FN4. Taylor, 529 U.S. at 406, 120 S.Ct. 1495. FN5. Id. at 407, 120 S.Ct. 1495. FN6. Valdez v. Cockrell, 274 F.3d 941, 947 (5th Cir.2001) (citing 28 U.S.C. § 2254(e)(1)).

III

Wooten first contends that the prosecution's delay in producing the full weight of its DNA evidence violated his due process rights. No matter how Wooten chooses to characterize this claim, it ultimately “stems from the defendant's ‘legitimate interest in the character of the procedure which leads to the imposition of sentence’ of death.”FN7 That interest embraces a right to fair notice if the defendant's case proceeds to trial-one that ensures “[a] defendant's right to notice of the charges against which he must defend,”FN8 the right to “[n]otice of the issues to be resolved by the adversary process,”FN9 and the right to be free from the use of “secret testimony in the penalty proceeding of a capital case which the defendant has had no opportunity to consider or rebut.”FN10

FN7. Gray v. Netherland, 518 U.S. 152, 164, 116 S.Ct. 2074, 135 L.Ed.2d 457 (1996) (quoting Gardner v. Florida, 430 U.S. 349, 358, 97 S.Ct. 1197, 51 L.Ed.2d 393 (1977)). FN8. Id. at 168, 116 S.Ct. 2074 (citing In re Ruffalo, 390 U.S. 544, 88 S.Ct. 1222, 20 L.Ed.2d 117 (1968); Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U.S. 196, 68 S.Ct. 514, 92 L.Ed. 644 (1948)). FN9. Lankford v. Idaho, 500 U.S. 110, 126, 111 S.Ct. 1723, 114 L.Ed.2d 173 (1991). FN10. Gray, 518 U.S. at 164, 116 S.Ct. 2074 (citing Gardner, 430 U.S. at 362, 97 S.Ct. 1197).

The right to fair notice, however, falls short of imposing a constitutional duty on the state to disclose incriminating evidence, and of course does not require the prosecution to hand over its case on a silver platter. Fair notice of the charges leveled and the issues to be resolved is one thing; any claim to notice of state evidence “stands on quite a different footing”FN11 because “ ‘[t]here is no general constitutional right to discovery in a criminal case, and Brady,’ which addressed only exculpatory evidence, ‘did not create one.’ ”FN12 Implicit in this broad principle is the absence of any constitutionally-footed duty to disclose evidence made stronger by state investigative efforts that continue after the defendant's arrest, subsequent to any plea negotiation, or during trial. For example, in Weatherford v. Bursey, the Supreme Court considered the due process claim of a defendant who had been convicted with the aid of surprise testimony of an accomplice who was an undercover agent.FN13 Though the prosecution had not intended to introduce the agent's testimony, it reversed course the day of trial and put the agent on the stand.FN14 To maintain his cover, the agent had previously told the *220 defendant and his counsel that he would not testify against the defendant.FN15 The Court nonetheless declined to find a due process violation because any resulting “disadvantage” at trial, “was no more than exists in any case where the State presents very damaging evidence that was not anticipated.”FN16 As a result, the defendant “must have realized that in going to trial the State was confident of conviction and that if any exculpatory evidence or possible defenses existed it would be extremely wise to have them available. Prudence would have counseled at least as much.”FN17

FN11. Id. Compare id. (refusing to find a due process violation where the defendant received only a day's notice of new testimony, but “had the opportunity to hear the testimony ... in open court, and to cross-examine [the witnesses]”) with Gardner, 430 U.S. at 362, 97 S.Ct. 1197 (finding a due process violation “when the death sentence was imposed, at least in part, on the basis of information which [the defendant] had no opportunity to deny or explain”). “Gardner literally had no opportunity to even see the confidential information.” Gray, 518 U.S. at 168-69, 116 S.Ct. 2074 (distinguishing Gardner from the facts in Gray on that basis).

FN12. Id. (quoting Weatherford, v. Bursey, 429 U.S. 545, 559, 97 S.Ct. 837, 51 L.Ed.2d 30 (1977)); Wardius v. Oregon, 412 U.S. 470, 474, 93 S.Ct. 2208, 37 L.Ed.2d 82 (1973) (“[T]he Due Process Clause has little to say regarding the amount of discovery which the parties must be afforded.”). See also Weatherford, 429 U.S. at 559, 97 S.Ct. 837 (“It does not follow from the prohibition against concealing evidence favorable to the accused that the prosecution must reveal before trial the names of all witnesses who will testify unfavorably.”).

FN13. 429 U.S. 545, 97 S.Ct. 837, 51 L.Ed.2d 30 (1977). FN14. Id. at 549, 97 S.Ct. 837. FN15. Id. at 560, 97 S.Ct. 837. FN16. Id. at 561, 97 S.Ct. 837. FN17. Id.

Recognizing the difficulty of any notice-of-evidence due process claim, Wooten relies largely on Lankford v. Idaho, a bench trial of a capital case where the prosecution did not argue for death but the judge who had said nothing about a possible death sentence gave one anyway, with the observation that he thought the prosecutor too lenient.FN18 From Lankford, Wooten would extract a principle that “a defendant's critical decisions in a death penalty case are inconsistent with due process of law when based on misinformation furnished, or misimpressions fostered, by representatives of the government.” Foregoing any argument that “the State had a constitutional duty under any theory, Brady or otherwise, to disclose the DNA evidence in question,” Wooten claims that, under Lankford, “the State's incomplete disclosure of the DNA evidence under the trial court's discovery order was tantamount to a false representation that no other relevant DNA evidence existed.” He says this “misrepresentation” led him to reject the plea offer and derailed his defense strategy, which focused on attacking the DNA's reliability. FN18. 500 U.S. at 115-18, 111 S.Ct. 1723.

Lankford found a due process violation because defense counsel was misled as to the issue (and ultimate sentence) to be argued;FN19 in this case, Wooten was aware of all issues to be considered, but bases his claim on putative defects born in the prosecution's untimely disclosure of inculpatory evidence. That distinction means the world, as the Supreme Court's notice-of-evidence jurisprudence-including Weatherford-demonstrates. Nevertheless, Wooten's argument is not without some merit, for there is a line of authority that leaves open the possibility that a defendant who is deliberately misled as to the full weight and import of the state's evidence might have a cognizable due process claim. In Gray v. Netherland, for example, the Supreme Court remanded a defendant's claim that prosecutors misled defense counsel about evidence they intended to use at sentencing.FN20 While explaining that due process is not impinged when a prosecutor merely “change[s] his mind over the course of the trial” (as in Weatherford), the Court took seriously the notion that due process could be violated if a prosecutor knowingly and affirmatively acts to deceive the defendant by concealing inculpatory evidence. FN21 But, Gray and others like it-assuming they endorse a constitutional right in the first place-would fault only “deliberate” misrepresentationsFN22 and Wooten concedes that any *221 misrepresentation made by prosecutors in this case was unintentional. As a result, even if Gray's hint rises to the level of clearly established law sufficient to support a habeas petition on AEDPA review, it is of no help to Wooten. So long as the evidentiary “misrepresentation” was unintended as in Weatherford, there is no due process violation.

FN19. Id. at 126, 111 S.Ct. 1723. FN20. Gray, 518 U.S. at 165-66, 116 S.Ct. 2074.FN21. Id. (citing Mooney v. Holohan, 294 U.S. 103, 112, 55 S.Ct. 340, 79 L.Ed. 791 (1935)). FN22. See, e.g., id.; Weatherford, 429 U.S. at 560, 97 S.Ct. 837 (distinguishing Weatherford from a case involving “deliberate misrepresentation”).

Moreover, much unlike the unexpected testimony in Gray and Weatherford, the state's prerogative to analyze and reanalyze DNA evidence to ensure its reliability should have come as a surprise to no one. Defense counsel in this case were aware that the state had significant physical evidence, that the evidence contained blood specimens, and that if that blood evidence proved reliable, it would be virtually conclusive of the guilty party's identity. When it is the analysis of physical evidence, and not the physical evidence itself that is at issue, requiring a hold on its development would ignore the fact-well-known to prosecution and defense counsel alike-that the physical evidence is still out there, capable of providing additional blood samples for DNA work-ups. We do not apply a snapshot test to evidence. FN23 When the actual physical evidence is in full view, there is no constitutional demand that the prosecution warrant any analyses of that evidence as final-as the best and last attempts. As everyone knows, the continuing existence of physical evidence-and late-coming DNA analyses of that evidence-cuts both ways for those accused of crimes.

FN23. See Weatherford, 429 U.S. at 561, 97 S.Ct. 837; supra notes 11-17.

This is not to say that a finding of deliberateness would require direct evidence: Wooten makes no institutional arguments and puts forth no evidence of historical and persistent delays from which we could infer a deliberate aim to mislead defendants, or to so push their counsel off balance that any given defense attorney would be unable to tell when a prosecutor is presenting a plea deal based on a reasonably strong case, or a laughably weak one. He also has not argued that the state mismanaged its relationship with the DNA laboratory to the extent that the communication gap took on the color of deliberate action.

Even if his due process right to a fair trial was not disturbed, Wooten contends he must be given a chance to accept the prosecution's plea offer anew because his initial rejection was based on misinformation. Again, the Supreme Court's decision in Weatherford is instructive. There, the defendant alleged that the prosecution had “lulled [him] into a false sense of security and denied him the opportunity ... to consider whether plea bargaining might be the best course.”FN24 Like Wooten, he claimed he would have taken the prosecution's offer of a plea had he only known the full extent of the state's inculpatory evidence.FN25 The Weatherford Court nonetheless balked, reminding that because “there is no constitutional right to plea bargain ... [i]t is a novel argument that constitutional rights are infringed by trying the defendant rather than accepting his plea of *222 guilty.”FN26

FN24. See id., 429 U.S. at 559, 97 S.Ct. 837. FN25. Id. at 560-61, 97 S.Ct. 837. For the sake of analysis, we take as given that Wooten would have accepted the plea had he known the DNA analyses would turn out to be virtually conclusive and reliable. That fact is not certain, however. The plea deal sought by the prosecution would have required Wooten, in exchange for taking the death penalty off the table, to admit to another murder as well. He was unwilling at the time to admit to that crime. FN26. Id. at 561, 97 S.Ct. 837.

To hold otherwise in this case would be to ignore the stark fact that plea bargaining presents a choice captive to one particular moment in time; a defendant's decision to accept an offer risks the state's case getting worse. A rejection risks the case getting better. Wooten does not cite to any case that purports to allow a defendant to reclaim a rejected bargain once those risks-assessed by both sides at the time the bargain was made-are realized. To the point, this contention ignores the reality that the state's plea offer to take the death penalty off the table was made on the same earlier, presumably weaker case. Nothing suggests there would have been a plea offer had the prosecution known the strength of its hand.

IV

To the extent Wooten's complaint can be recast as an independent ineffective assistance of counsel claim, that claim is similarly without merit. To prevail on a Strickland claim, a petitioner must establish both that his counsel's performance fell below an objective standard of reasonableness and that, had counsel performed reasonably, there is a reasonable probability that the result in his case would have been different. FN27 Wooten's claim was adjudicated on the merits by the state court-and rejected-so the question here “ ‘is not whether a federal court believes the state court's determination’ under the Strickland standard ‘was incorrect but whether the determination was unreasonable-a substantially higher threshold.’ And, because the Strickland standard is a general standard, a state court has even more latitude to reasonably determine that a defendant has not satisfied that standard.”FN28 Our review is thus “doubly deferential.”FN29

FN27. Smith v. Spisak, --- U.S. ----, 130 S.Ct. 676, 684-85, ---L.Ed.2d ---- (2010) (quoting Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 688, 694, 104 S.Ct. 2052, 80 L.Ed.2d 674 (1984)). FN28. Knowles v. Mirzayance, --- U.S. ----, 129 S.Ct. 1411, 1420, 173 L.Ed.2d 251 (2009). FN29. Id.

Given this highly circumscribed standard of review and our due process analysis, which applies with full force here as well, Wooten's Strickland argument fails to convince. Rendering effective counsel means doing a reasonably competent job with the evidence of the case as it stands. There is no loss of effectiveness under the Sixth Amendment as the strength of the state's case grows, just a lessening of the defendant's chance to prevail.

V

Because we conclude that the state court proceedings were not infected with error, we AFFIRM the district court's denial of Wooten's habeas petition.