Executed May 19, 2010 at 6:39 p.m. by Lethal Injection in Mississippi

20th murderer executed in U.S. in 2010

1208th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Mississippi in 2010

11th murderer executed in Mississippi since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

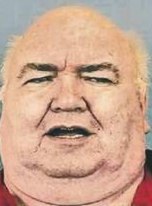

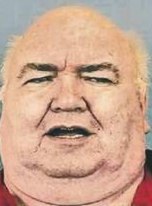

Paul Everette Woodward W / M / 38 - 62 |

Rhonda Crane W / F / 24 |

09-15-95 |

Citations:

Woodward v. State, 533 So.2d 418 (Miss. 1988). (Direct Appeal)

Woodward v. State, 635 So.2d 805 (Miss. 1993). (PCR)

Woodward v. State, 726 So.2d 524 (Miss. 1997). (Direct Appeal After Remand)

Woodward v. Epps, 580 F.3d 318 (5th Cir. 2009) (Habeas).

Final/Special Meal:

Hamburger (grilled, well done, seasoned with salt & pepper) on a real bun with mustard, mayonnaise, lettuce, tomato, onion and dill pickle, French fries with salt, fried onion rings, a bowl of chili without beans, a pint of vanilla ice cream and two 20oz. root beers.

Final Words:

"Thank you warden - I'm sorry, I mean commissioner. I would like to say the Lord's Prayer." Woodward invited others in the execution room to join in.

Internet Sources:

PARCHMAN — Before he died Wednesday evening, death row inmate Paul Everette Woodward asked witnesses to join him in reciting the Lord's Prayer, but he never publicly showed remorse for the 1986 kidnapping, rape and murder of Rhonda Holloman Crane, of Escatawpa.

Woodward, 62, was pronounced dead by lethal injection at 6:39 p.m. in the first of two back-to-back executions scheduled this week. Gerald Holland, 72, is scheduled for execution at 6:15 p.m. today. Like Woodward, he also has asked Gov. Haley Barbour for clemency. Barbour denied Woodward's request just hours before Wednesday's execution - Mississippi's first since 2008.

The execution followed more than two decades of legal battles over whether Woodward should be put to death for Crane's murder. A Hinds County jury convicted Woodward in 1987 after the case was moved from Perry County because of pretrial publicity. But he was resentenced six years later because of a technicality. Crane, 25, had been traveling on Mississippi 29 in Perry County to join her family for a camping trip when Woodward, then working as a logger, used his work truck to make her to stop. He forced her into his logging truck at gunpoint and took her to a secluded area, where he raped her. Woodward then shot Crane in the back of the head and left her to die.

"I thought this day would never come," said Crane's sister, Renee Lander, who witnessed the execution, speaking at a news conference after the execution. "We waited a long time to see him put to death. I'm very glad to have seen him take his last breath. I wish it could have been brutal like Rhonda's death."

Woodward did not know Crane."The scary part to me is that the victim could have been any young lady - any female," Corrections Commissioner Chris Epps said. According to court records, Woodward ultimately made written and videotaped confessions and admitted to his boss that he had killed Crane, who was a volunteer with the Jackson County Youth Court.

During the trial, Woodward's attorneys told the jury that Woodward had a "dark influence" over him and claimed to have conversations with the devil, court records show. Attorneys also disclosed that Woodward previously had been committed to the state mental hospital at Whitfield and had been arrested at least twice before. "One reason for admitting these prior bad acts was our defense theory that Paul had been 'troubled' all his life and had wrestled with good versus evil," his attorney, Terryl Rushing, wrote in an affidavit contained in his appeal to the Mississippi Supreme Court. "He had always striven to do the right thing but was overwhelmed at the time he killed Rhonda Crane."

Mississippi has executed 10 others since the U.S. Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty in 1976.

Described as active and talkative in his final hours, Woodward visited with spiritual adviser Buck Buchannan, and finished his last meal. He had a grilled hamburger - well done and seasoned with salt and pepper - dressed with mustard, mayonnaise, lettuce, tomato, onion and pickles; French fries with salt; fried onion rings; a bowl of chili without beans; a pint of vanilla ice cream and two 20-ounce root beers at about 5 p.m., while meeting with Mississippi State Penitentiary chaplain James Whisnet.

Epps said the 307-pound Woodward ate everything "except a few of his French fries." The inmate had been eating lightly earlier in the day. "He told me he was saving room for his last meal," Epps said. Woodward did not take a sedative before the execution.

Though he was believed to have had at least five children and 11 grandchildren, Woodward took no family visits in his final days and made no calls to relatives. "I think a reasonable person would assume he doesn't have close family ties," Epps said. Three protesters wearing shirts with anti-death penalty slogans stood at the Parchman entrance as a mix of sodium pentothal, saline, pavulon and potassium chloride was pumped into Woodward's veins. His body was released to the University of Mississippi Medical Center at his request.

Epps, who first met Woodward when he was admitted to Parchman in 1987, said the inmate always had been talkative and followed the rules. He had just two infractions - both in 1993 - in the 23 years he was imprisoned.

Mississippi now has 60 inmates on death row, including Holland, who is scheduled to die for the 1986 rape and murder of Krystal Dee King on her 15th birthday in Gulfport.

Epps noted the last time the state had back-to-back executions was 1961 - the year Epps was born.

"I have received word that we may be doing some more (executions) this year," he said.

Lander said her family had been disappointed by repeated delays in Woodward's execution. She said she thought it should have happened years ago.

"He had many, many appeals and he gave Rhonda none," she said.

Epps agreed 23 years is a long time for a prisoner to sit on death row.

"We talk about finance and expense ... I think it's also important that we think about the victims' family and what they have to go through," he said.

Lander said the delay of the execution created "anger" in her family.

"It made my father ... more bitter knowing he was still alive," she said.

WOODWARD TIMELINE

•July 23, 1986: Rhonda Crane is kidnapped, raped and murdered in Perry County.

Mississippi Department of Corrections 1 HOMICIDE- 04/29/1987 PERRY DEATH

Date: May 19, 2010

May 19, 2010 Execution of Paul E. Woodward - 7:00 p.m. News Briefing

Parchman, Miss. - The Mississippi Department of Corrections (MDOC) today conducted the mandated execution of state inmate Paul E. Woodward. Inmate Woodward was pronounced dead at 6:39 p.m. at the state penitentiary at Parchman.

MDOC Commissioner Christopher Epps said during a press conference following the execution that the evening marked the close of the Paul E. Woodward case. Woodward was convicted in 1987 for the crimes of capital murder (with the underlying crime of rape), kidnapping and sexual battery of Rhonda Crane in Perry County in 1986.

“It is our agency’s role to see that the order of the court is carried out professionally with dignity and decency. That has been done and justice was championed today,” said MDOC Commissioner Chris Epps. In this final chapter tonight, it is our heartfelt hope that the family of Rhonda Crane may now begin the process of healing. Our prayers go out to you as you continue life’s journey,” said Epps.

Epps concluded his comments by commending Deputy Commissioner of Institutions Emmitt Sparkman and the entire Mississippi State Penitentiary security staff for their professionalism during the process.

###

May 19, 2010 Scheduled Execution of Paul E. Woodward - 2:00 p.m. News Briefing

Parchman, Miss. - The Mississippi Department of Corrections (MDOC) will hold three news briefings today related to events surrounding the Wednesday, May 19th scheduled execution of death row Inmate Paul E. Woodward, MDOC #45981. The following is an update on Inmate Woodward’s recent visits and telephone calls, activities, last meal to be served, and the official list of execution witnesses.

Visits with Inmate Paul E. Woodward - Tuesday, May 18, 2010

Inmate Woodward did visit from 1:15 pm until 3:00 with attorneys C. Jackson Williams and Nina Rifkind.

Wednesday, May 19, 2010

Inmate Woodward has requested no visits with family.

Approved visitation list:

Activities of Woodward

This morning at 5:10 a.m., for breakfast, Inmate Woodward was offered 4oz oatmeal, 1 roll, ham, milk, 2 eggs, and syrup. Inmate Woodward did consume the roll, the syrup and the milk.

Inmate Woodward was offered lunch today consisting of 1 roll, 4oz pork, 4oz pinto beans, 1 square cake, 4oz steamed cabbage, 1 milk. Inmate Woodward did consume ˝ portion of cabbage, ˝ portion of pork, and the milk.

Inmate Woodward has access to a telephone to place unlimited collect calls to persons on his approved telephone list. He had access to the phone from 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. on Tuesday and will have access today, May 19th from 8:00 a.m. until 5:00 p.m.

2:00 p.m. News Briefing – Scheduled Execution of Paul E. Woodward

Inmate Woodward made no phone calls yesterday and has made no calls thus far today.

According to the MDOC correctional officers that are posted outside his cell, Inmate Woodward is observed to be active and talkative.

Inmate Woodward has requested that his body be released to the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

Inmate Woodward requested the following as his last meal: hamburger (grilled, well done, seasoned with salt & pepper) on a real bun with mustard, mayonnaise, lettuce, tomato, onion and dill pickle, French fries with salt, fried onion rings, a bowl of chili without beans, a pint of vanilla ice cream and two 20oz. root beers.

Inmate Woodward’s Collect Telephone Calls - Tuesday, May 18, 2010 No phone calls.

Execution Witnesses

Condemned Inmate Woodward requested no spiritual advisor witness the execution

INMATES EXECUTED IN THE MISSISSIPPI GAS CHAMBER

Gerald A. Gallego White Male Murder 03-03-55

PRISONERS EXECUTED BY LETHAL INJECTION

Tracy A. Hanson White Male Murder 07-17-02

Source: Mississippi Department of Corrections, Mississippi State Penitentiary

"Mississippi Executes Paul Everette Woodward, 305 Pound Killer, for '86 Rape-Slay of Rhonda Crane," by Edecio Martinez. (May 20, 2010)

PARCHMAN, Miss. (CBS/AP) Paul Everette Woodward said a prayer before being put to death by lethal injection Wednesday for the 1986 rape and murder of 24-year-old Rhonda Crane. "I would like to say the Lord's Prayer," Woodward said, inviting others in the execution room to join in.

After the prayer, the 62-year-old, who weighed 305 pounds, took a couple of heavy breaths, turned his head to the left and closed his eyes. He was pronounced dead at 6:39 p.m. by Sunflower County Coroner Heather Burton at the state penitentiary in Parchman.

Woodward was convicted of capital murder in 1987 for raping and killing Crane, a Jackson County Youth Court volunteer. Crane was driving in July 1986 to join her parents for a family camping trip when Woodward used his log truck to force her to stop on Mississippi Highway 29 south of New Augusta, prosecutors said. Woodward, who was 38 at the time, kidnapped and raped Crane, then shot her to death.

Woodward did not fight his execution beyond an appeal to Gov. Haley Barbour for clemency, which the governor denied Wednesday.

Renee Lander, the victim's sister, told reporters at a post-execution news conference that the family wasn't sure this day would come.

"We waited a long time to see him put to death. I am very glad to see him take his last breath," Lander said. "I wish it had been brutal like Rhonda's death."

"His last breath: Woodward executed," by Jack Elliott Jr. (Associated Press • May 20, 2010)

PARCHMAN — Paul Everette Woodward was put to death by lethal injection Wednesday for the 1986 rape and murder of a 24-year-old Escatawpa woman.

Woodward, clad in a red prison jumpsuit and sandals, was pronounced dead at 6:39 p.m. by Sunflower County Coroner Heather Burton at the state penitentiary in Parchman.

"I would like to say the Lord's Prayer," Woodward said, inviting others in the execution room to join in.

After the prayer, Woodward, a large man at 305 pounds, took a couple of heavy breaths, turned his head to the left and closed his eyes.

His attorney, C. Jackson Williams of Oxford, left the building without commenting. Woodward did not fight his execution beyond an appeal to Gov. Haley Barbour for clemency, which the governor denied Wednesday.

Renee Lander of Escatawpa, the victim's sister, told reporters at a post-execution news conference that the family wasn't sure this day would come.

"We waited a long time to see him put to death. I am very glad to see him take his last breath. I wish it had been brutal like Rhonda's death.

"There was never any question about his guilt. His death didn't change anything that happened. He lived 24 years longer than Rhonda," she said.

Woodward's execution was one of two set in as many days. Gerald James Holland is scheduled to be executed today at 6 p.m.

Woodward, 62, was convicted of capital murder in 1987 for raping and killing Rhonda Crane, a Jackson County Youth Court volunteer.

Crane was driving in July 1986 to join her parents for a family camping trip when Woodward used his log truck to force her to stop on Mississippi Highway 29 south of New Augusta, prosecutors said.

Woodward, who was 38 at the time, kidnapped and raped Crane, then shot her to death, prosecutors said.

Corrections Commissioner Christopher Epps said Woodward asked that his body be turned over to the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson.

He said Woodward asked for no family members to witness the execution.

Epps said Woodward appeared in a good mood as he prepared to die. His last meal was hamburger and fries and 2 20-ounce root beers.

"He never knew the victim. The scary part for me, having been in law enforcement, is that victim could have been any young lady," Epps said.

The Mississippi Supreme Court declined to halt the executions of Woodward and Holland.

Holland has also asked Barbour for clemency. No decision from the governor has been announced.

Holland, 72, was sentenced to death for raping and killing 15-year-old Krystal King of Gulfport in 1987. He is the oldest death-row inmate in Mississippi.

The Mississippi Supreme Court on Wednesday refused to stop Holland's execution based on the appeal of a lawsuit filed on behalf of 16 condemned inmates.

Woodward was not a party in that lawsuit.

The last back-to-back executions happened in 1961, according to Mississippi Department of Corrections records. Howard Cook was executed on Dec. 19, 1961, and Ellic Lee was put to death the following day.

AT A GLANCE

"Waiting a big part of this story," by Ed Kemp. (May 20, 2010)

The worst part is the waiting. I'm not talking about the day-long wait at the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman, in anticipation of the execution of death row inmate Paul Everette Woodward.

That was like a glorified high school study hall, as about 15 members from media outlets ranging from Greenville to the Associated Press to Mississippi Public Broadcasting were thrown together in a one-story inmate visitation room.

We tapped away at computers and fidgeted with cameras under signs reading "Shake Down Line Only" and "No Money Past this Point." In between, Mississippi Department of Corrections Commissioner Christopher Epps briefed us on Woodward's visitors; his eating habits; his signs, if any, of remorse.

No, I'm talking about the long wait in the MDOC van right before the scheduled 6 p.m. execution, as Clarion-Ledger reporter Rick Cleveland, WDAM broadcaster Mike McDaniel, Randy Bell of Clear Channel Radio and I were transported from the inmate visitation room across acres of farmland to the victim's execution observation room.

Thirty minutes? 40 minutes? It was hard to tell. Watches were forbidden, one of many security measures outlined by MDOC communications director Suzanne Singletary.

We were told later by Epps that the long wait was related to sticking the IV into Woodward's vein.

We passed the time chatting about deadlines. About the facts of the murder case. About the wait. And we did the required execution experience tally. Among McDaniel, Cleveland and me, it went like this:

"You ever been to an execution before?"

"No."

"Me neither."

Bell had us rookies beat, having seen four previous executions.

Then we disembarked and watched the execution from the well-air-conditioned observation room in what seemed an almost anti-climactic moment. Woodward recited the Lord's Prayer verbatim, thanked Epps and then, with a couple of faint chest heaves, slowly faded from life. He was pronounced dead at 6:39 p.m.

Waiting, of course, is a huge part of this story. Victim Rhonda Crane's sister Renee Ladner watched Woodward die from the observation room. She squeezed the hand of MDOC victim's service director Melinda Box, before sitting solemnly watching the last breaths of her sister's murderer.

Then later from the podium, she gave a statement to the media, as her daughter Kelli Belcher held up a photo of Crane that was taken when she was 18.

She used the word "bitterness" to describe how she and other family members felt that Woodward had lived 24 years after the murder he had committed, including 23 after first being sentenced to death.

"I think it needs to be swifter," she said of the death penalty.

She noted that Woodward had only given her sister one hour to live after he steered her car from the road that day in July.

"He had many appeals and he didn't give any to Rhonda," she said.

Absorbing the act of seeing Woodward die and Ladner's simmering grief was hard thing to do on a Wednesday night - my first witnessed execution.

In the end Woodrow Wilkins, longtime reporter for the Delta Democratic Times and current reporter with WXVT in Greenville who sat next to me at a table in the press room, may have summed it up best. He said this was the third execution he had covered and second witnessed.

"We're here to do a job. The corrections officers are here to do a job," he said. "I like to think that we're here to see that protocol is followed."

Rhonda’s automobile was left on the highway with the engine running, the driver’s door open and her purse on the car seat. A motorist traveling in a vehicle on the same highway saw a white colored, unloaded, logging truck moving away from the victim's vehicle, and notified the authorities. Additionally, a housewife residing on a bluff along the highway at the location of the car noted a logging truck with a white cab stop in front of her driveway. A white male exited and walked toward the back of his truck and returned with a blonde haired woman wearing yellow clothing. As he held her by her arm, the male yelled sufficiently loud for the housewife to hear the words “get in, get in,” and forced the blonde woman into the driver’s door of the truck and then drove off. The housewife investigated the scene on the highway in front of her house, discovered the abandoned car, and notified the authorities.

Law enforcement officers began an investigation to locate Rhonda Crane. The officers discovered that Paul Everette Woodward unloaded logs at a pulp mill and departed the yard at 11:36 a.m. in a white Mack log truck. Woodward arrived at his wood yard at approximately 12:45 to 1:00 p.m. The yard manager noted that he was late arriving at the yard and was wet from sweating. A drive from the mill to the wood yard takes approximately thirty minutes. A sheriff’s deputy stopped Woodward, who was driving a white Mack logging truck, around 2:00 p.m. on the afternoon of July 23, to ask if he had seen anything that would assist in the investigation of Rhonda Crane’s disappearance. Woodward replied that he had not seen anything.

Defendant was convicted in the Circuit Court, Hinds County, of capital murder, kidnapping, and sexual battery. Defendant appealed. The Supreme Court, Prather, J., held that: (1) crimes could be charged in single indictment; (2) kidnapping and sexual battery based on fellatio were not same offense for double jeopardy purposes as felony capital murder during forcible, sexual intercourse; and (3) search of defendant's truck for blue topped fountain pens after investigator had previously conducted valid consent search, seen pens in truck, learned of similar pen at crime scene, and realized significance of pens was reasonable whether it was conducted before or after arrest. Affirmed. Robertson, J., concurred by separate written opinion.

PRATHER, Justice, for the Court:

Paul Everette Woodward was convicted of the crimes of capital murder, kidnapping and sexual battery of Rhonda Crane, and sentenced to death. Venue was changed from Perry County to the Circuit Court of Hinds County. On appeal, Woodward presents the following issues for review:

AS TO THE GUILT/INNOCENCE PHASE

I. The multi-count indictment was prejudicial and should have been quashed by the trial court.

AS TO GUILT AND SENTENCE PHASE

VIII. Cumulative errors which took place during the course of the trial denied the appellant a fair trial:

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

Law enforcement officers identified the ownership of the Crane vehicle and its occupant and immediately began an investigation to locate Mrs. Crane. Their investigation developed the following facts. Paul Everette Woodward unloaded logs at the Leaf River Forest Products, a pulp mill, and departed the yard at 11:36 a.m. in a white Mack log truck. Woodward arrived at his wood yard, Walley Timber Company, at approximately 12:45 to 1:00 p.m. The yard manager noted that he was late arriving back at the yard and was wet from sweating. A drive from Leaf River to Walley takes approximately thirty minutes. A sheriff's deputy stopped Woodward, who was driving a white Mack logging truck, around 2:00 p.m. on the afternoon of July 23, to ask if he had seen anything that would assist in the investigation of Rhonda Crane's disappearance. Woodward replied that he had not seen anything.

Through the investigation, it was ascertained that Paul Everette Woodward was the only driver of a white colored logging truck operating at the nearby timber yards on that date. On the following date, the body of Rhonda Crane was located in the nearby wooded area by her father and a friend. She was wearing a yellow shirt and a blue topped fountain pen was found at the scene.

THE GUILT/INNOCENCE PHASE

After Woodward was indicted on September 8, 1986, he filed a demurrer and motion to quash the indictment contending that the muliple count indictment was prejudicial and denied him due process of law. The lower court entered an order overruling and denying the demurrer and motion to quash.

Woodward raises two issues in this assignment: (1) that he was prejudiced by assigning three felony crimes in a single indictment and (2) that under the merger doctrine there should be only one capital charge. Thus, this Court addresses the question.

In relevant part, the state legislature has defined capital murder as follows:

The killing of a human being without the authority of law by any means or in any manner shall be capital murder in the following cases: ...

(e) When done with or without any design to effect death, by any person engaged in the commission of the crime of rape, burglary, kidnapping, arson, robbery, sexual battery, unnatural intercourse with any child under the age of twelve (12), or nonconsensual unnatural intercourse with mankind, or in any attempt to commit such felonies....

Miss.Code Ann. § 97-3-19(2)(e) (Supp.1987).

The Legislature recently authorized the use of single multi-count indictments as follows:

(1) Two (2) or more offenses which are triable in the same court may be charged in the same indictment with a separate count for each offense if: (a) the offenses are based on the same act or transaction; or (b) the offenses are based on two (2) or more acts or transactions connected together or constituting parts of a common scheme or plan.

(2) Where two (2) or more offenses are properly charged in separate counts of a single indictment, all such charges may be tried in a single proceeding.

(3) When a defendant is convicted of two (2) or more offenses charged in separate counts of an indictment, the court shall impose separate sentences for each such conviction.

(4) The jury or the court, in cases in which the jury is waived, shall return a separate verdict for each count of an indictment drawn under subsection (1) of this section.

(5) Nothing contained in this section shall be construed to prohibit the court from exercising its statutory authority to suspend either the imposition or execution of any sentence or sentences imposed hereunder, nor to prohibit the court from exercising its discretion to impose such sentences to run either concurrently with or consecutively to each other or any other sentence or sentences previously imposed upon the defendant.

Miss.Code Ann. § 99-7-2 (Supp.1987). (Effective from and after July 1, 1986).

This Court has historically disapproved of a single multiple count indictment because of the possibility of the exact complaint that Woodward makes here, the pyramiding of multiple punishments growing out of the same set of operative facts. Thomas v. State, 474 So.2d 604 (Miss.1985). However, the cases relied upon by the defendant were decided before enactment of the multi-count indictment statute effective July 1, 1986.

The Legislature has now addressed the use of the single indictment containing multi-counts, and it has stated that as a matter of state policy no objection may be validly raised to an indictment containing multi-counts if the statute is otherwise followed. Thus, this Court holds that there is no error in the State's charging of three felony counts within a single indictment since this indictment was returned after the effective date of the statute and followed its dictates.

Secondly, Woodward argues that all three counts of the indictment arose out of the same incident. Under Miss.Code Ann. § 97-3-19, capital murder is murder committed during the commission of the crime of rape, kidnapping or sexual battery. The defendant contends he should have been charged in one single count of only capital murder because the provisions of the statute merged the crimes of kidnapping, sexual battery and rape into capital murder if murder was committed while the person was engaged in the commission of those underlying crimes.

The U.S. Supreme Court has held that the double jeopardy clause does not prohibit states from prosecuting an accused for multiple offenses in a single prosecution. Ohio v. Johnson, 467 U.S. 493, 500, 104 S.Ct. 2536, 2541, 81 L.Ed.2d 425, 434 (1984).

Woodward appeals to Justice Robertson's concurring statements in Dixon v. State, 465 So.2d 1092, 1099 (Miss.1985), and in Thomas v. State, 474 So.2d 604, 607-608 (Miss.1985), that a defendant may be convicted and sentenced for felony murder or the felony, but not both, due to the federal and state double jeopardy clauses and the common law merger rule. Faraga v. State, 514 So.2d 295, 312 (Miss.1987) (Robertson, J., concurring). However, the precise question here is whether the defendant may be convicted of both felony murder and another felony or felonies which were not used as a basis for the felony murder charge in a multi-count indictment arising out of the same transaction or occurrence. The courts have rarely touched on this question. However, numerous cases address the problem of a conviction for both capital murder and the underlying felony.

At the most, the double jeopardy clause is violated only if the charges for the felony murder and the underlying felony are tried separately:

When as here, conviction of a greater crime, murder, cannot be had without conviction of the lesser crime, robbery with firearms, the Double Jeopardy Clause bars prosecution for the lesser crime after conviction of the greater one. Harris v. Oklahoma, 433 U.S. 682, 97 S.Ct. 2912, 53 L.Ed.2d 1054 (1977) [ followed in Payne v. Virginia, 468 U.S. 1062, 104 S.Ct. 3573, 82 L.Ed.2d 801 (1984) ]. “In contrast to the double jeopardy protection against multiple trials, the final component of double jeopardy-protection against cumulative punishments-is designed to insure that the sentencing discretion of courts is confined to the limits established by the Legislature.” Ohio v. Johnson, 467 U.S. 493, 499, 104 S.Ct. 2536, 2540-2541, 81 L.Ed.2d 425, 433 (1984).

This Court has relied upon Blockburger v. United States, 284 U.S. 299, 304, 52 S.Ct. 180, 182, 76 L.Ed. 306 (1932) to support the position that a criminal defendant may be prosecuted for more than one statutory offense arising out of a basic set of facts. Harden v. State, 460 So.2d 1194, 1199 (Miss.1984).

In the instant case, it cannot be said that kidnapping or sexual battery is the same offense as capital murder in the commission of the crime of rape. Each offense requires proof of at least one element which the other does not contain. The kidnapping and sexual battery charges would not merge because they were acts separate and distinct from the act producing the death of Rhonda Crane. Based upon Woodward's confessions, the sexual battery with which he was charged was a separate crime from the rape. The rape charge requires proof of forcible, natural sexual intercourse, Miss.Code Ann. § 97-3-65 (Supp.1987), whereas the sexual battery charge requires proof of any sexual penetration, in this case fellatio, without the victim's consent, Miss.Code Ann. §§ 97-3-95 and 97-3-97(a) (Supp.1987). As seen in Woodward's confessions, in the indictment and in the instructions, the rape charge and the sexual battery charge were for two separate acts. Therefore, the underlying felony of rape has not been separately charged.

Any doubt as to the validity of the multi-count indictment should be dispelled by McFee v. State, 511 So.2d 130 (Miss.1987), wherein the defendant was originally indicted for capital murder of the rape victim, but the underlying felony used was burglary. The defendant pled guilty to simple murder, and afterwards, prosecution for the rape charge was commenced. This Court stated that nothing in the capital murder indictment suggested that the defendant committed rape and that the prosecution was well within its prerogatives in seeking an indictment and trial on the additional charge of rape. Id. at 132-133.

Finally, this Court has consistently rejected any claims that the underlying felony merges into the capital murder due to the language of the felony murder statute. The statutory provisions dealing with murder and the particular felonies are intended to protect different societal interests. Smith v. State, 499 So.2d 750, 753-54 (Miss.1986); Faraga v. State, 514 So.2d 295, 302-303 (Miss.1987). The trial court is affirmed in his denial of the motion to quash the indictment.

II. DID THE TRIAL COURT COMMIT REVERSIBLE ERROR IN EXCUSING FOR CAUSE VENIREPERSONS MARY MAGEE AND ELLA M. LEWIS?

At issue in the assigning of this error is whether the two venire persons were excused because of their views on the death penalty or because of their incompetence. The basis for this challenge arises under the holding of Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510, 88 S.Ct. 1770, 20 L.Ed.2d 776 (1968). The Witherspoon rule holds that the death penalty could not be imposed where “the jury that imposed or recommended it was chosen by excluding veniremen for cause simply because they voiced general objections to the death penalty or expressed conscientious or religious scruples against its infliction.” Witherspoon, 391 U.S. at 522, 88 S.Ct. at 1777, 20 L.Ed.2d at 785 (1968). In Adams v. Texas, 448 U.S. 38, 100 S.Ct. 2521, 65 L.Ed.2d 581 (1980), the Court reexamined Witherspoon and held that a juror could not be excluded for cause unless his views about capital punishment would prevent or substantially impair the performance of his duties as a juror in accordance with the court's instructions and his oath. This holding was reaffirmed in Wainwright v. Witt, 469 U.S. 412, 105 S.Ct. 844, 83 L.Ed.2d 841 (1985). See also Lockett v. State, 517 So.2d 1317, 1335 (Miss.1987); Wiley v. State, 484 So.2d 339 (Miss.1986); Fuselier v. State, 468 So.2d 45, 53-54 (Miss.1985).

To answer the issue of whether the venirepersons were excused because of their death penalty views or their incompetence can be answered by the facts of this record, which are as follows: The State challenged Mary Magee, who slept during the course of voir dire, at first, without the court noticing it. Once she snored; then subsequently while sleeping again, the court said something to her. The voir dire of prospective jurors lasted for three days. Mary McGee indicated that her drowsiness was caused from nervousness. She had not slept well the night before, but she answered that it would not interfere with her jury service. The court struck her for cause because of her incompetency.

The State next challenged Ella M. Lewis for cause because she had been disabled since the 1950's, was taking medication for various ailments and was a self-proclaimed genius. Her speech was slurred and she had difficulty responding appropriately to questions. The court had to admonish her on a couple of occasions when she approached the bench at inappropriate times. She was the individual who was one hour and five minutes late for voir dire on the third day. Lewis answered the question that she could serve as a juror, and indicated the reason for her tardiness was that she overslept.

The court added that her responses in chambers were at best incoherent, and she too was excused for cause.

On a questionnaire and at voir dire, Magee indicated some opposition to imposition of the death penalty. It took long and tedious questioning to qualify her for the jury under Witherspoon, supra, and its progeny. At voir dire, Lewis indicated that she had no conscientious scruples against the infliction of the death penalty when the law and the testimony authorized it in proper cases. However, on her questionnaire, she indicated “If it's necessary within the findings, okay.” She agreed that there was some difference in those two answers.

Woodward asserts that striking these two jurors who were opposed to capital punishment allowed the State to get around the Witherspoon test to save two of their challenges to strike other jurors who were also opposed to capital punishment. Thus, Woodward contends that he was prejudiced by denial of a fair and impartial jury in a death penalty case.

Generally, a juror removed on a challenge for cause is one against whom a cause for challenge exists that would likely affect his competency or his impartiality at trial. Billiot v. State, 454 So.2d 445, 457 (Miss.1984). Under Wainwright v. Witt, 469 U.S. 412, 105 S.Ct. 844, 83 L.Ed.2d 841 (1985), the U.S. Supreme Court held that deference must be paid to the trial judge who sees and hears the juror and that the trial judge's determination that a juror is biased will not be reversed where it is supported by the record.

“It is well founded that the trial judge has the discretion to excuse potential jurors for cause if the court believes the juror could not try the case impartially.” Burt v. State, 493 So.2d 1325, 1327 (Miss.1986). This Court will not lightly interfere with a finding of fact made by the trial judge in a criminal case, and it will reverse only when it is satisfied that the trial court has erred in holding a juror competent, when this Court is clearly of the opinion that he was not a competent juror. Dennis v. State, 91 Miss. 221, 44 So. 825 (1907). See also Norris v. State, 490 So.2d 839 (Miss.1986); Weaver v. State, 497 So.2d 1089, 1094 (Miss.1986) (a physical disability, such as deafness, is sufficient to support a challenge for cause).

It is this Court's opinion that the trial judge did not err in excusing the sleeping juror or the tardy juror who took numerous medications, and who gave incoherent and contradictory answers. These findings are sufficient and justifiable. This assignment is rejected.

III. DID THE TRIAL COURT ERR IN DENYING THE MOTION TO QUASH THE JURY PANEL BECAUSE OF THE PREJUDICIAL EFFECT OF THE STATE'S OPENING STATEMENT BEFORE VOIR DIRE EXAMINATION OF THE JURY?

After voir dire by the court as to the death penalty, the court stood in recess. Early on the second day of voir dire, the court told the prospective jury panel that the attorneys were always afforded an opportunity to make a brief opening statement prior to their engaging in voir dire examination. Such opening statements did not preclude opening statements on beginning their cases in chief.

After the State's voir dire examination, Woodward moved the court to quash the entire jury panel because of the district attorney's statements of what expected proof would be offered of the three crimes against this defendant. At least three or four jurors, possibly more, indicated that they had changed their position on capital punishment, as two of them phrased it, “from the evidence they had heard today.”

Both the court and district attorney had admonished the venirepersons several times that the district attorney's remarks were not evidence and that the State has the burden of proof.

The appellant argues that the court departed from established procedure in allowing the State to make an alleged inflammatory opening statement prior to voir dire. The defendant asserts that the departure from standard procedure caused the jury panel to be biased, prejudiced and unfair to the appellant and, therefore, constituted reversible error. Opening statements prior to voir dire were a regular practice of this trial court, and Woodward made no objection to the practice when it was announced. Most of those questioned indicated that their opinion had not actually changed, but only that they more clearly understood the proceedings and could vote for the death penalty if warranted. The court noted and overruled the motion to quash the jury panel.

Two rules of procedure in trying criminal cases supply guidance in this area. “The prosecuting attorney may make an opening statement to the jury, confining the statement to the facts he expects to prove.” Unif.Crim.R.Cir.Ct.Prac. 5.11. “Attorneys will direct remarks to the jury panel only during voir dire, opening and closing statements.” Unif.Crim.R.Cir.Ct.Prac. 5.05. Woodward argues that the word “jury” means the jury which has been impanelled and selected to try the case and not the prospective jury. Even so, the rule does not exclude some type of opening statement during voir dire. The crucial point is that the prosecuting attorney must confine his statement to the facts he expects to prove.

Finally, “the voir dire examination is largely a matter within the sound discretion of the trial judge....” Murphy v. State, 246 So.2d 920, 922 (Miss.1971). The appellant admits that there was no departure from statutory procedure, and it is this Court's opinion that the Uniform Criminal Rules of Circuit Court Practice were not violated by the opening statement. The opening statement was confined to the facts which the prosecuting attorney expected to prove, and the prosecuting attorney's remarks were within the permissible range of voir dire examination. The trial judge did not abuse his discretion in permitting such opening statement.

This Court has admonished “the trial judge [to] conduct his own independent examination of the jurors to determine whether they can follow the testimony, the instructions, and their juror's oath and return a verdict of guilty even though such a verdict could result in the imposition of the death penalty....” Williamson v. State, 512 So.2d 868, 881 (Miss.1987). See Gray v. State, 472 So.2d 409, 421 (Miss.1985), rev'd Gray v. Mississippi, 481 U.S. 648, 107 S.Ct. 2045, 95 L.Ed.2d 622 (1987). In the instant case, the trial judge did conduct his own independent examination and kept control of the voir dire examinations of the State and the defendant.

It is this Court's opinion that the trial court should be affirmed on this issue.

IV. DID THE TRIAL COURT ERR IN OVERRULING THE APPELLANT'S MOTION TO SUPPRESS THE PHYSICAL EVIDENCE CONSISTING OF A PACK OF RELIANCE INK PENS WHICH WERE REMOVED FROM THE APPELLANT'S VEHICLE?

Woodward filed a motion to suppress all of the physical evidence, but his argument specifically addresses several blue topped fountain pens. Initially it should be noted that the defendant came by the sheriff's office around 8:00 a.m. on July 24, and at that time he had a blue topped fountain pen in his shirt pocket. Arlon Moulds, investigator for the district attorney's office, testified that he talked with Woodward on July 24, 1986 about 12:15 or 12:30 p.m., prior to any arrest. Moulds asked Woodward to sign a waiver form allowing a search of his logging truck. Woodward signed the consent to search, which was received into evidence. When the investigating officers exchanged information, they realized that there was a blue topped fountain pen at the crime scene, one in Woodward's shirt pocket, and a partial packet of pens in his truck. Realizing this fact, Moulds later asked Woodward to return to the sheriff's office, which Woodward did. Moulds stated that Woodward was arrested prior to the time he signed the waiver of rights form, which was 2:30 p.m., and that Woodward's truck, its contents and a fountain pen from his pocket were seized after the arrest. The waiver form had “Time 2:30 p.m.” written at the top. On cross-examination Moulds testified that the arrest occurred about 2:30 p.m.

Julia James, a crime scene specialist with the Mississippi Crime Laboratory, testified at the suppression hearing that about lunch time, she searched the truck pursuant to Woodward's consent to search and seized certain items from it. At that time, she saw the pack of blue topped fountain pens. After finding a similar ink pen at the crime scene, she returned to the sheriff's office, where the truck had been seized, and collected the pack of ink pens at “approximately 2:30, 2:40.”

Later in the suppression hearing, Moulds testified that after the arrest he removed a similar pen from Woodward's shirt pocket at approximately 3:08 p.m. On cross, he agreed with defense counsel that the reason he arrested Woodward was “because of the pen,” which was the crucial evidence. He continued to assert that the arrest occurred at approximately 2:30.

The trial court overruled the motion to suppress, stating the following:

As far as the physical evidence is concerned, it is the finding of this Court beyond a reasonable doubt that the seizure of all items were performed after the execution of a valid consent form with the Defendant freely and voluntarily having waived his rights and consented thereto to the search of his truck, and that this was done without any threat, force, coercion or intimidation. That the seizure of all subsequent items were made subsequent to a lawful arrest, and that probable cause did in fact exist for any and all searches and subsequent seizures....

Woodward argues that the second search was pre-arrest, and being three hours after the first search, was not a part of the initial investigation. Woodward correctly notes that after the first consent search, he was allowed to take the truck and continue his daily work activities. He asserts that this intervening factor made any subsequent search unreasonable and illegal. The State contends that the second search was valid whether pre-arrest or post-arrest, with which this Court agrees.

The trial judge made a factual finding supported by the record, and this Court will not overturn a finding of fact made by a trial judge unless clearly erroneous. West v. State, 463 So.2d 1048, 1056 (Miss.1985). Further, this Court must give effect to all reasonable presumptions in favor of the ruling of the court below.

In Mississippi, where the police officer determines that it is necessary to leave the scene of the search in order to examine the body at the hospital, a 25 to 30 minute delay is not unreasonable. In Crum v. State, 349 So.2d 1059 (Miss.1977), this Court held:

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Tennessee quoted from United States v. Rabinowitz, 339 U.S. 56, 70 S.Ct. 430, 434, 94 L.Ed. 653 (1950), where it was said:

“What is a reasonable search is not to be determined by any fixed formula. The Constitution does not define what are ‘unreasonable’ searches and, regrettably, in our discipline we have no ready litmuspaper test. The recurring questions of the reasonableness of searches must find resolution in the facts and circumstances of each case.... Reasonableness is in the first instance for the District Court to determine.”

The Tennessee Court then said:

We cannot say that the second search of Voss' room was unauthorized and that the evidence tendered and admitted was the result of an unlawful search. It conclusively appears from the record before us that the arresting officers, having lodged their prisoners in jail, returned at once to make a further and more thorough search of the premises for evidence connecting them with the murder of Mr. Hutchinson. The time which elapsed between the arrest, the immediate search and this second search was of such short duration that we are justified in holding that the second search was merely a continuation of the first. It cannot be considered as unreasonable in any legal sense.

Id. at 1062.

Again, it is this Court's opinion that the trial court should be affirmed on this issue in his holding that the second search was authorized and reasonable, and that therefore the evidence was the result of a lawful search.

V. DID THE COURT ERR IN FAILING TO SUPPRESS THE CONFESSIONS OF THE DEFENDANT?

Where this Court is concerned in substantial part with a finding of fact, so long as the trial court applies the correct legal standards, this Court will not overturn a finding of fact made by a trial judge unless it be clearly erroneous. Neal v. State, 451 So.2d 743, 753 (Miss.1984). Further, a trial court's determination of voluntariness is considered a finding of fact that will not be reversed on appeal unless manifestly wrong, or contrary to the overwhelming weight of the evidence. Dedeaux v. State, 519 So.2d 886, 889-90 (Miss.1988).

A. THE WRITTEN CONFESSION

Woodward testified that there was no attorney present when he gave his written statement although he requested one prior to giving the statement. He further stated that he did not personally read the yellow legal pad or the typed statement which he signed. He also testified that Detective Rawls told him to sign or he and Moulds would “throw all the irons in the fire.”

On the contrary, Arlon Moulds testified that after arrest, Woodward was informed of his rights, that before giving the statement, he freely and voluntarily executed a waiver of rights, which was introduced into evidence, and that he never requested the services of a lawyer. Moulds further testified to the free and voluntary nature of the statement itself. The requisites of Agee v. State, 185 So.2d 671 (Miss.1966), were complied with, and there is no claim to the contrary as to any of the confessions.

Moulds stated that he wrote Woodward's statement out on a yellow legal pad, word for word, and would have to stop him periodically to catch up. After writing the statement in long hand, he carried it into the adjoining office, without affording Woodward an opportunity to examine it. Woodward did not ratify it in any way. Mrs. Elaine Davis typed the statements from the yellow sheets of paper.

The typed confession was admitted into evidence. Woodward had an opportunity to review and did in fact read the statement, and acknowledged that it was correct, except for some misspelled words, each of which Woodward initialled at Moulds' direction and in Moulds' presence.

Moulds never compared the typed statement with his notes, but threw the notes into the garbage can because he had a signed affidavit typed statement. Elaine Davis testified that she typed the statement verbatim from Moulds' notes.

Woodward moved to suppress the written confession because it was tainted by the State's failure to furnish him the original written statement as required by Unif.Crim.R.Cir.Ct.Prac. 4.06 and because the destruction of the original statement denied Woodward his rights to a fair and impartial trial and adequate defense as provided by the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

The trial judge found as follows:

This Court finds beyond a reasonable doubt that this statement was free and voluntary and was taken only after the defendant had been advised of all of his rights and after it was obvious that the Defendant understood his rights and intelligently waived his rights. This Court now specifically resolves, as a result of the evidentiary hearing, that this Defendant did not at any time request the services of an attorney, and that the oral statements made by this Defendant concerning the gun and the statement to Detective Rawls wherein the Defendant said, “I shot her” would be admissible. This Court finds that the Defendant did not ratify the written notes of Investigator Moulds but did have an opportunity to review the typed statement which the typist, Mrs. Elaine Davis, testified was typed verbatim from the handwritten notes of Investigator Moulds. It should be noted further that this Defendant even made corrections of the typographical errors which had been acknowledged by him and that the Defendant initialed the same. The case of Dickins v. State goes only to the weight and credibility of the issue. This Court rules that the written statements of the Defendant are free and voluntary, and therefore, are admissible.

Woodward relies upon the following portions of Rule 4.06:

(a) The prosecution shall disclose to each defendant or to his attorney, and permit him to inspect, copy, test, and photograph upon request and without further order the following:

(2) Copy of any recorded statement of the defendant's to any law enforcement officer; ...

(6) Copy of any exculpatory material concerning defendant.

The Fifth Circuit has held that there was no discovery violation as to an officer's notes, taken in the presence of witnesses, and destroyed in good faith.

Moore also asserts that his confession is inadmissible because FBI Agent Genakos was unable to produce for his examination the original notes taken at Moore's questioning. We deem this contention to be without merit. The summary made by Genakos contains the inculpatory statements allegedly made by Moore during his examination by the FBI agents and there is no doubt that under the Jencks Act, 18 U.S.C. § 3500(b), if the agents had the notes they would be required to produce them. However, Genakos' notes, taken in the presence of witnesses, were destroyed in good faith. There was no error here. Killian v. United States, 368 U.S. 231, 242, 82 S.Ct. 302 [308], 7 L.Ed.2d 256 (1961).

United States v. Moore, 453 F.2d 601, 603-604 (3rd Cir.1971). See United States v. Monroe, 397 F.Supp. 726, 732-3 (D.C.Cir.1975); People v. Nunez, 698 P.2d 1376, 1388 (Colo.App.1984); (rejecting a due process claim on a similar set of facts).

It is this Court's opinion that the trial judge properly admitted the written confession.

B. THE VIDEOTAPED CONFESSION

Moulds testified that on July 24, 1986 at approximately 6:45 p.m. (after the written confession), Woodward freely and voluntarily gave a videotaped confession in the district attorney's office, after being read his rights from a waiver of rights form. This form was received into evidence. Woodward signed only the portion acknowledging that he knew his rights, not the portion waiving his rights. However, Moulds testified that Woodward waived his rights and began the statement. On the video tape itself, which this Court viewed, Woodward was read his rights, stated that he understood them and that he wanted to sign the waiver, and did in fact sign the form.

The trial judge made the following finding:

We now turn the Court's attentions ... the videotaped statement. It is uncontradicted that this statement is free and voluntary, and this Court so rules. Prior to, at the time of the taking of this statement, and during the taking of same, it was done without any threats, coercion, intimidation or force to this Defendant. This Court specifically finds beyond a reasonable doubt that the Defendant waived his right to remain silent, and that after being administered his Miranda rights and warnings, that the Defendant acknowledged those rights and did then and there give a free and voluntary statement.

It is the further finding of this Court that there is no technical requirement that a written waiver be signed by the Defendant, and the State proved beyond a reasonable doubt, by a totality of the circumstances, and after this Court had the benefit of reviewing the videotape, that this Defendant, after being questioned by Investigator Moulds concerning his rights, that this Defendant did then and there acknowledge his rights and waived his rights and gave a statement, and then in fact, that statement was in his own words. This Court is of the opinion that this statement which is contained in that videotape is free and voluntary and finds at this time that the same would be admissible.

Woodward submits that the record does not show that he intelligently waived his rights after being advised of them and that his failure to sign the waiver clearly demonstrates, in this case, that he did not intend to waive his rights.

The U.S. Supreme Court has held that an express waiver of the defendant's rights is not always required, even where the defendant has refused to sign a waiver. North Carolina v. Butler, 441 U.S. 369, 99 S.Ct. 1755, 60 L.Ed.2d 286 (1979). Rather, the question of waiver turns on the particular facts and circumstances surrounding the case, including the background, experience and conduct of the accused. Id. at 374-75, 99 S.Ct. at 1758, 60 L.Ed.2d at 293 [quoting Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458, 464, 58 S.Ct. 1019, 1023, 82 L.Ed. 1461 (1938) ]. While refusal to sign a waiver may weigh against finding such a waiver, see McDonald v. Lucas, 677 F.2d 518 (5th Cir.1982); 2 W. Ringel, Searches & Seizures, Arrests & Confessions, § 28.3(b)(3) (2d Ed.1987), a failure to sign, by itself, does not weigh against such finding. There is no evidence that Woodward refused to sign the waiver. Rather, it appears that Woodward inadvertently failed to sign the form in question twice, and the officers failed to notice this.

It is this Court's opinion that the trial judge properly admitted the videotaped confession.

C. THE ORAL STATEMENT TO WOODWARD'S EMPLOYER

Moulds testified that he asked Woodward whether he would like to call anybody and he said he would like to call Mrs. Harrigill, his boss. Moulds then placed the call for Woodward because it was a long-distance, credit card call, from the secretary's office in the district attorney's office. Moulds, the sheriff and a deputy sheriff sat there listening and overheard Woodward's side of the conversation.

Susan Harrigill, owner of Harrigill Refuge Services, a trucking company, testified that she employed Woodward and owned the truck driven by Paul Woodward. On the evening of July 24, 1986, she received a telephone call, which she recounted as follows:

Someone said that there's someone here who wants to speak with you. Then Paul took the phone, and he said, “Hello.” And I said, “Paul, where are you?” He said, “Hattiesburg Jail.” I said, “What's happened?” He said, “They have charged me with capital murder.” I said, “Did you do it?” He said, “Yes, I did.”

....

... I said, “Why did you do it?” He said, “I don't know.” I said, “I didn't know you carried a gun.” He said, “Most people didn't”-either “most people” or “most folks”.

She stated that no law enforcement officer requested her to ask these questions of Woodward. She further stated that it was Moulds who said, “There's somebody here who wants to speak to you.” She testified that about ten days later, Moulds called her stating that he overheard her telephone conversation with Woodward. For that reason Moulds knew to contact Harrigill to testify.

The trial judge found as follows:

We shall now address the oral statement made to Mrs. Harrigill, the employer of the Defendant. This statement in the opinion of this Court does not fall within the criteria of Miranda under the following cases: McElroy v. State, Brown v. State, and McBride v. State. The phone call that was made was for the benefit of the Defendant, and this Court finds that there was no law enforcement officer on the phone with the Defendant and Mrs. Harrigill, and that the call was not done as a subterfuge to the interrogation by any law enforcement officer through Mrs. Harrigill. That this Court finds beyond a reasonable doubt that the statement of the Defendant in the form of a confession was for the benefit of the Defendant and was done by him to notify his mother and his employer concerning personal matters. The evidentiary hearing in this matter reveals that it is uncontradicted that the oral statement of the Defendant to Mrs. Harrigill is free and voluntary, and that there was no threats, force, coercion or intimidation of the Defendant. Mrs. Harrigill testified that there was no collusion between herself and any law enforcement official, and that she asked the Defendant questions out of her own curiosity, and that the Defendant spoke to her about his actions. There is absolutely no doubt that this oral statement is free and voluntary, and based thereon, it is the ruling of this Court that the same would be admissible.

Woodward submits that the telephone conversation constituted a custodial interrogation because the officers placed the call and that it should have been suppressed because of a failure to provide Woodward with the Miranda warnings.

In Arizona v. Mauro, 481 U.S. 520, 107 S.Ct. 1931, 95 L.Ed.2d 458, reh'g. denied, 483 U.S. 1034, 107 S.Ct. 3278, 97 L.Ed.2d 782 (1987), the U.S. Supreme Court held that the defendant, despite indicating that he did not wish to be questioned further without a lawyer present, was not subjected to the functional equivalent of police interrogation by permitting his wife to see and talk with him. In both Mauro and the instant case, no officers questioned the defendant, there is no evidence that the permission for the conversation was a psychological ploy, there is no evidence that the officers arranged the conversation for the purpose of eliciting incriminating statements; the presence of the police officer was known by the defendant; and merely allowing such conversations would not cause the defendant to feel that he was being coerced to incriminate himself. Further, the mere possibility of incrimination does not mean that an interrogation occurred. Mauro is entirely consistent with prior Mississippi case law. Dycus v. State, 440 So.2d 246, 256 (Miss.1983); Brown v. State, 293 So.2d 425, 427-28 (Miss.1974).

It is this Court's opinion that the trial judge properly admitted the oral statement to Woodward's employer. The trial judge is affirmed on admission of all confessions.

VI. SHOULD THE APPELLANT HAVE BEEN GRANTED A CIRCUMSTANTIAL EVIDENCE INSTRUCTION?

The court refused to give a circumstantial evidence instruction. For the instruction to be required, the prosecution must be without a confession and wholly without eye witnesses to the gravamen of the offense charged. Kniep v. State, 525 So.2d 385 (Miss.1988). The same is true where there is an admission by the defendant on a significant element of the offense. Mack v. State, 481 So.2d 793, 795 (Miss.1985).

The details of the crimes were described in both the written and the videotaped confessions. The mere fact that Woodward asserts that the confession indicates the voluntary nature of the sexual intercourse does not require a circumstantial evidence instruction even if the assertion is true, because the sexual intercourse is proved by the confession.

VII. DID THE STATE FAIL TO PROVE THE UNDERLYING FELONY OF RAPE?

At the conclusion of the State's case, Woodward moved the court for a directed verdict of not guilty of capital murder for failure of the State to prove the necessary elements of the underlying felony of rape. The court overruled the motion. Woodward asserts that the State failed to prove that the sexual intercourse was by force rather than voluntary.

The victim's husband testified that he had last had sexual relations with his wife two days prior to her death. Dr. Robert Cooke testified that he found no tears on her clothing and no lacerations or tears in the vagina area. He noted that the lack of lacerations does not prove that there was no legal rape because different people react differently when they are fearful of their life. Judy James, a crime lab expert, testified similarly. On appeal, Woodward argues that the circumstantial evidence actually indicates that the victim was killed during the course of robbery or grand larceny because James testified that she found two rings on the ground near the victim and a white beaded necklace in her left hand.

Larry Turner, a forensic serologist, testified that Woodward is a secretor with type A blood and that the seminal fluids present in the victim's vagina were from a person who is a secretor with type A blood.

The testimony from Woodward's confession certainly constitutes sufficient proof that sexual intercourse between Woodward and the victim occurred. However, the vaginal sexual intercourse occurred after the oral intercourse and, more importantly, was accompanied by threats of violence while Woodward had the pistol in his hand.

There may be sufficient proof of rape despite a complete absence of bruises or lacerations on the victim's body. Stewart v. State, 466 So.2d 906, 908 (Miss.1985). Stewart also states the following:

The well-settled rule is that in a prosecution for rape, physical force on the part of the assailant or physical resistance on the part of the victim is not necessary if the proof shows beyond a reasonable doubt that the victim surrendered because of fear arising out of a reasonable apprehension of great bodily harm. Clemons v. State, 460 So.2d 835 (Miss.1984); Davis v. State, 406 So.2d 795 (Miss.1981); Fields v. State, 293 So.2d 430 (Miss.1974)....

Id. at 909.

It is this Court's opinion that the evidence presented was sufficient to convince a rational factfinder of Woodward's guilt of the crime of rape beyond a reasonable doubt. Id.

* * *

There remains one multicount assignment which addresses principally the guilt phase, but which contains one incident during the sentence phase.

VIII. DID CUMULATIVE ERRORS DURING THE COURSE OF THE TRIAL DENY THE APPELLANT A FAIR TRIAL?

It is true that in capital cases, although no error, standing alone, requires reversal, the aggregate effect of various errors may create such an atmosphere of bias, passion and prejudice that they effectively deny the defendant a fundamentally fair trial. Stringer v. State, 500 So.2d 928, 939 (Miss.1986); Williams v. State, 445 So.2d 798, 814 (Miss.1984).

This Court must determine whether any prosecutorial misconduct, viewed in light of the entire trial, denied the defendant a fundamentally fair trial. Lockett v. State, 517 So.2d 1317, 1333 (Miss.1987).

The actions asserted by Woodward to be error for their cumulative effects are now considered individually.

A. THE STARE DOWN

Defense counsel also moved for a mistrial because during the majority of the victim's father's testimony he stared at the defendant. On leaving the witness stand, the victim's father stopped in front of the defendant and stared him down for a few brief seconds before the district attorney moved him past the defendant. This behavior was also noted in the defendant's motion for a new trial.

Woodward relies upon Fuselier v. State, 468 So.2d 45 (Miss.1985), wherein the victim's daughter conspicuously placed herself within the rail of the courtroom facing the jury box after her testimony. She also conferred on several occasions with the district attorney. In finding the daughter's behavior objectionable, this Court noted the following rule:

Only officers of the court, attorneys and litigants or one representative of a litigant in the case on trial will be permitted within the rail of the courtroom, unless authorized by court.

Unif.Crim.R.Cir.Ct.Prac. 5.01.

Of course, the action here falls far short of that in Fuselier. The testimony of the victim's father here was relevant, had probative value, and was admissible no matter how emotional his testimony became. Evans v. State, 422 So.2d 737, 743 (Miss.1982), cert. denied, 476 U.S. 1178, 106 S.Ct. 2908, 90 L.Ed.2d 994 (1986). See Booth v. Maryland, 482 U.S. 496, 107 S.Ct. 2529, 2535 n. 10, 96 L.Ed.2d 440, 451 n. 10, reh'g. denied, 483 U.S. 1056, 108 S.Ct. 31, 97 L.Ed.2d 820 (1987). Furthermore, the stare at the counsel table was very brief, and the victim's father did not remain within the rail of the courtroom. The trial court was in control of the proceedings at all times. Therefore, this portion of the assignment is without merit.

B. THE RABBIT TRAIL

On cross-examination and redirect examination of Woodward's employer, Mrs. Harrigill, she was questioned about problems relating to the high range gears on Woodward's truck and on the number of rounds made by Woodward on July 23. The district attorney finally warned against getting off on a rabbit trial in closing argument. Defense counsel moved for a mistrial based on the remark because it was made in the presence of the jury. The court overruled the motion for mistrial but instructed the jury to disregard any extraneous comments of the district attorney or any attorney which would not be within the framework of the trial of this case. It is well established in Mississippi law “that jurors are presumed to heed the trial judge's directive to disregard a question or statement or even an entire testimony.” White v. State, 520 So.2d 497, 500 (Miss.1988). Therefore, we now find that the warning by the trial judge was sufficient to cure any possible prejudice to the defendant.

C. AND D. THROWING THE PISTOL AND LOADING THE PISTOL

The record reflects that during the district attorney's closing argument, he picked up the defendant's pistol and threw it in the air, demonstrating the defendant's action when he was arrested. Defense counsel objected and argued that the demonstration was highly improper, prejudicial and had no place in a court of law. The court overruled the motion for mistrial and cautioned the district attorney. During the rebuttal closing argument, the district attorney loaded the empty shell that killed Rhonda Crane into the defendant's pistol. Defense counsel objected and moved for a mistrial. The court overruled this motion. On the motion for new trial, defense counsel stated that the district attorney had thrown the pistol in the air for 10 to 12 feet landing in front of the jury.

Woodward admitted in his confession that he had thrown the pistol out of the truck. Rickey Rawls testified that Woodward said he threw the pistol out about half way across a bridge and later showed authorities where he had thrown the pistol for its recovery.

The demonstration by the district attorney, although theatrical, was questionable conduct for a court of law. In Fuselier v. State, 468 So.2d 45, 53 (Miss.1985), this Court expressed the view that this Court strives for a verdict based on reason and rules rather than emotion. However, the occurrence here was properly handled by the trial court and constituted no reversible error. Therefore, this portion of the assignment must also fail.

E. THE IMPROPER ARGUMENT

In the district attorney's rebuttal closing argument during the sentencing phase, he stated, “You know, as bad as I hate to say it, what about prisoner's rights? What about those people in Parchman who are in there for drugs?” Defense counsel objected and moved for a mistrial and for an instruction to the jury to disregard the remark. The court sustained the objection and instructed the jury to disregard but overruled the motion for a mistrial.

Woodward's reliance on Hance v. Zant, 696 F.2d 940 (11th Cir.1983), is misplaced because Hance has been largely overruled. Davis v. Kemp, 829 F.2d 1522, 1526 (11th Cir.1987); Brooks v. Kemp, 762 F.2d 1383, 1398-99 (11th Cir.1985) (en banc), vacated on other grounds, 478 U.S. 1016, 106 S.Ct. 3325, 92 L.Ed.2d 732 (1986).

In Jurek v. Texas, 428 U.S. 262, 96 S.Ct. 2950, 49 L.Ed.2d 929 (1976), the Supreme Court held that the future dangerousness of a defendant is a proper consideration in imposing death. See Tucker, 762 F.2d at 1507; Bowen v. Kemp, 769 F.2d 672, 679 (11th Cir.1985). In the above quoted excerpt, the prosecutor dramatically illustrated this future dangerousness. In Brooks, the prosecutor brought this very matter home to the jury by asking, “Who's daughter will be killed next?” We found such an argument to be constitutional, concluding that: “A legitimate future dangerousness argument is not rendered improper merely because the prosecutor refers to possible victims.” Brooks, 762 F.2d at 1412. The argument made in this case is no more emotion laden than the imagery created by the prosecutor in Brooks.

Davis, 829 F.2d at 1528-29. Included in the prosecutor's argument in Brooks was the suggestion that the defendant may kill a guard or fellow prisoner. 762 F.2d at 1411 & n. 46. See also, Evans v. Thigpen, 809 F.2d 239, 243 (5th Cir.1987). The prosecutor's arguments were “directly relevant to the consideration of whether Brooks would remain a threat to society.” 762 F.2d at 1411. On the same day Brooks was decided, the eleventh circuit also specifically held in another case that an argument about the safety of prisoners and guards if the defendant were to receive a life sentence was an appropriate means of pointing out the possibility of the defendant's future dangerousness and did not call for a speculative inquiry into prison conditions. Tucker v. Kemp, 762 F.2d 1480, 1486 (11th Cir.1985), vacated, 474 U.S. 1001, 106 S.Ct. 517, 88 L.Ed.2d 452 (1985), on remand, 802 F.2d 1293 (11th Cir.1986), cert. denied, 480 U.S. 911, 107 S.Ct. 1359, 94 L.Ed.2d 529 (1987).

In light of these recent decisions, we conclude that this final portion of the assignment is without merit. We further conclude that the cumulative effect of these alleged errors do not merit reversal of either guilt or sentence phase of this case.

IX.

Following the guilt/innocence phase of this consolidation trial of Paul Woodward for the separate crimes of (1) capital murder, (2) kidnapping, and (3) sexual battery under a multi-count indictment, the jury returned three separate verdicts of guilty to all charges. The trial court deferred sentencing on kidnapping and sexual battery until after the bifurcated hearing on the capital murder charge.

At the sentencing trial, the State introduced all evidence from the guilt phase, with the reservations by the defendant of all former objections raised by him.

The defendant presented evidence of mitigating circumstances. Prior to trial, the defendant had been examined at Mississippi State Hospital and found to be competent to stand trial. Subsequently, the defendant gave notice to the State that he would offer a defense of insanity at the time of the alleged crime and moved the court to afford financial assistance for independent psychological testing and court attendance of the psychologist. The court ordered the same. Ake v. Oklahoma, 470 U.S. 68, 105 S.Ct. 1087, 84 L.Ed.2d 53, (1985). After the private testing, the defendant withdrew his insanity defense and gave notice to the State of his intent to introduce expert testimony related to a mental disease, defect or other mental condition. Such mitigating proof was offered by the defendant at the sentencing phase.

After conclusion of the sentencing phase proof, the court submitted the following aggravating circumstances to the jury for their consideration: (1) that the capital murder of Rhonda Crane was committed while Paul Woodward was engaged in the commission of rape; (2) that the capital murder of Rhonda Crane was especially heinous, atrocious or cruel; and (3) that the capital murder offense was committed for the purpose of avoiding or preventing a lawful arrest, or effecting an escape from custody. In addition, the State submitted an instruction of a definition of “especially heinous, atrocious, and cruel.” Maynard v. Cartwright, 486 U.S. 356, 108 S.Ct. 1853, 100 L.Ed.2d 372 (1988). Following its deliberation, the jury returned the following verdict:

We the jury, unanimously find from the evidence beyond a reasonable doubt that the following facts existed at the time of the commission of capital murder:

1. That the defendant actually killed Rhonda Crane;

2. That the defendant attempted to kill Rhonda Crane;

3. That the defendant intended that the killing of Rhonda Crane take place;

4. That the defendant contemplated that lethal force would be employed during the commission of the crime of felonious rape.

Additionally, the jury found that: (1) all three above aggravating circumstances existed; (2) the aggravating circumstances were sufficient to impose the death penalty; (3) there are insufficient mitigating circumstances to outweigh the aggravating circumstance(s); and unanimously found that the defendant should suffer death for capital murder.

The court entered three separate sentences, sentencing the defendant to thirty years in the Mississippi Department of Corrections for the crime of kidnapping and to thirty years in the Mississippi Department of Corrections for the crime of sexual battery, and that the sentences for these two crimes shall run consecutively with each other. After the jury verdict of death on capital murder, the court entered the order reflecting that verdict.

The court here on review affirms the guilt and sentencing phases of this trial.

X.

Miss.Code Ann. § 99-19-105(3)(c) (1972), as amended, directs this Court to consider in death penalty cases, in addition to the assigned errors, the punishment imposed, as follows:

(3) With regard to the sentence, the court shall determine:

(a) Whether the sentence of death was imposed under the influence of passion, prejudice or any other arbitrary factor;

(b) Whether the evidence supports the jury's or judge's finding of a statutory aggravating circumstance as enumerated in Section 99-19-101; and

(c) Whether the sentence of death is excessive or disproportionate to the penalty imposed in similar cases, considering both the crime and the defendant.

Having made a thorough review of this record, this Court holds that as to the above 3(a), the death penalty was not the result of passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor; that as to 3(b) the jury's finding of statutory aggravating circumstances is supported in the record; and that as to 3(c) the sentence of death is proportionate to the penalty imposed in similar cases, considering the defendant and the crime. (See Appendix). The Court, therefore, affirms the penalty of death.

CONVICTION AND SENTENCE TO THIRTY (30) YEARS IN THE MISSISSIPPI DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS FOR THE CRIME OF KIDNAPPING AFFIRMED, AND CONVICTION AND SENTENCE TO THIRTY (30) YEARS IN THE MISSISSIPPI DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS FOR THE CRIME OF SEXUAL BATTERY AFFIRMED, SAID SENTENCES TO RUN CONSECUTIVELY WITH EACH OTHER.

CONVICTION OF CAPITAL MURDER AND SENTENCE OF DEATH AFFIRMED. NOVEMBER 23, 1988, SET AS DATE FOR EXECUTION OF SENTENCE IN THE MANNER PROVIDED BY LAW.

ROY NOBLE LEE, C.J., HAWKINS and DAN M. LEE, P.JJ., and SULLIVAN, ANDERSON, GRIFFIN and ZUCCARO, JJ., concur.

ROBERTSON, J., concurs by separate written opinion.

Woodward v. State, 635 So.2d 805 (Miss. 1993). (PCR)

After affirmance of conviction of capital murder, kidnapping, and sexual battery, 533 So.2d 418, defendant sought postconviction relief. The Supreme Court, Prather, P.J., held that: (1) counsel's admission during guilt phase that defendant was guilty of simple murder, rather than capital murder, did not constitute ineffective assistance of counsel; (2) counsel's failure to offer all evidence they had in mitigation during penalty phase, combined with counsel's remarks that he could not ask jury to spare defendant's life, constituted ineffective assistance of counsel; and (3) instruction on aggravating factor of capital murder being especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel mandated remand for new sentencing hearing. Death sentence vacated and remanded for new sentencing hearing. Smith, J., concurred in part, dissented in part, and filed opinion in which Dan M. Lee, P.J., and James L. Roberts, Jr., J., joined.

PRATHER, Presiding Justice, for the Court:

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

Paul Everett Woodward was found guilty of capital murder and sentenced to death by the jury on April 29, 1987. On direct appeal, this Court affirmed Woodward's conviction. Woodward v. State, 533 So.2d 418 (Miss.1988). Woodward's Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Supreme Court was denied on April 17, 1989. Woodward v. Mississippi, 490 U.S. 1028, 109 S.Ct. 1767, 104 L.Ed.2d 202 (1989).