Executed May 4, 2007 1:35 a.m. CDT by Lethal Injection in Indiana

17th murderer executed in U.S. in 2007

1074th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Indiana in 2007

18th murderer executed in Indiana since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

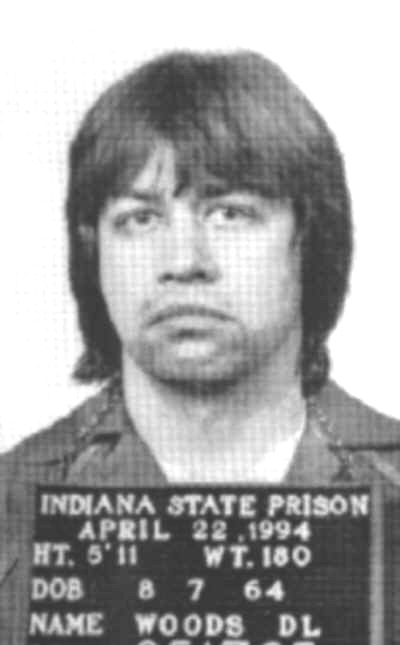

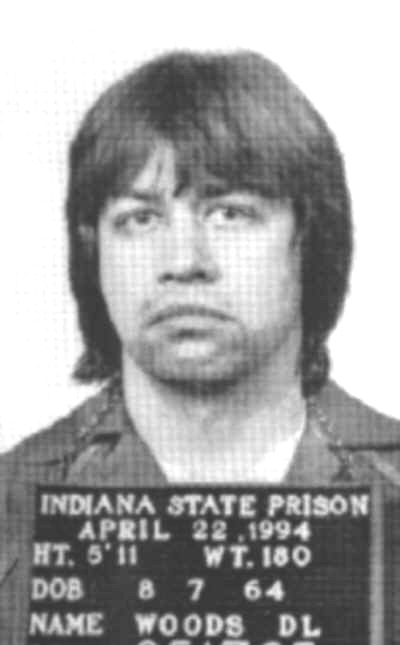

David Leon Woods W / M / 19 - 42 |

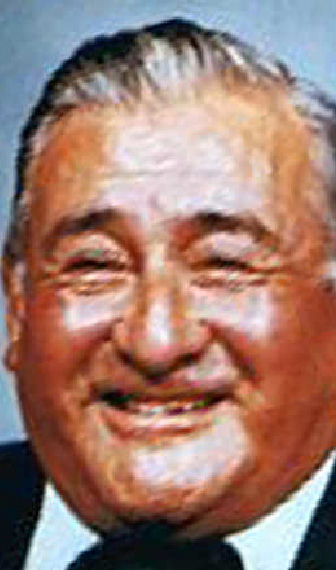

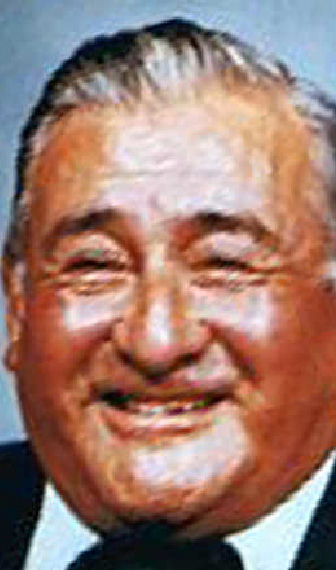

Juan Placencia H / M / 77 |

Final Words:

"I want Juan's family to know I truly am sorry, and I do have remorse. I want everybody to know that I do have peace, and it’s through Jesus Christ that I have this peace.

Citations:

Direct Appeal:

Woods v. State, 547 N.E.2d 772 (Ind. November 28, 1989) (885-S-343)

Conviction Affirmed 5-0 DP Affirmed 5-0

Debruler Opinion; Shepard, Givan, Pivarnik, Dickson concur.

For Defendant: David P. Freund, Deputy Public Defender (Carpenter)

For State: Cheryl L. Greiner, Deputy Attorney General (Pearson)

Woods v. State, 557 N.E.2d 1325 (Ind. November 23, 1990) (On Rehearing)

Affirmed 5-0; Debruler Opinion; Shepard, Givan, Pivarnik, Dickson concur.

For Defendant: David P. Freund, Deputy Public Defender (Carpenter)

For State: Cheryl L. Greiner, Deputy Attorney General (Pearson)

Woods v. Indiana>, 111 S.Ct. 2911 (1991) (Cert. denied)

PCR:

PCR Petition filed 05-06-94. Amended PCR filed 06-21-94.

State’s Answer to PCR Petition filed 07-25-94.

PCR Hearing 01-06-96, 01-17-96, 01-18-96, 01-19-96.

Special Judge David Ault

For Defendant: David C. Stebbins, Columbus, OH, Joe Keith Lewis, Marion

For State: Eugene Bosworth

04-15-96 PCR Petition denied.

Woods v. State, 701 N.E.2d 1208 (Ind. November 3, 1998) (06S00-9403-PD-224)

(Appeal of PCR denial by Special Judge David Ault)

Affirmed 5-0; Boehm Opinion; Shepard, Dickson, Sullivan, Selby concur.

For Defendant: David C. Stebbins, Columbus, OH, Joe Keith Lewis, Marion

For State: James D. Dimitri, Deputy Attorney General (Modisett)

Woods v. Indiana, 120 S.Ct. 150 (1999) (Cert. denied)

Habeas:

04-14-99 Notice of Intent to File Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus filed.

12-02-99 Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus filed in U.S. District Court, Northern District of Indiana.

David Leon Woods v. Rondale Anderson, Superintendent (IP 99-C- 0520-M/S)

Judge Larry J. McKinney

For Defendant: William Van Der Pol, Jr., Martinsville, Teresa Harper, Bloomington

For State: Michael A. Hurst, Stephen R. Creason, Deputy Attorneys General (S. Carter)

04-27-00 Respondent’s Return and Memorandum filed in opposition to Writ of Habeas Corpus.

03-31-03 Petitioner’s Reply and Memorandum filed in support of Writ of Habeas Corpus.

02-02-04 Writ of Habeas Corpus denied.

Woods v. Anderson, 302 F.Supp.2d 915 (S.D. Ind. February 2, 2004) (IP99-0520-C-M/S)

(Order of U.S. District Court Judge Larry J. McKinney, Southern District of Indiana, denying Writ of Habeas Corpus.)

For Defendant: William Van Der Pol, Jr., Martinsville, Teresa Harper, Bloomington

For State: Thomas D. Perkins, Deputy Attorney General (S. Carter)

Woods v. McBride, 430 F.3d 813 (7th Cir. November 30, 2005) (04-1776)

(Appeal of denial of Writ of Habeas Corpus)

Affirmed 3-0; Opinion by Circuit Judge Michael S. Kanne .

Judge William J. Bauer and Judge Terence T. Evans concur.

For Defendant: William Van Der Pol, Jr., Martinsville, Teresa Harper, Bloomington

For State: Thomas D. Perkins, Deputy Attorney General (S. Carter)

Internet Sources:

Clark County Prosecuting Attorney

ON DEATH ROW SINCE 03-28-85

DOB: 08-07-1964

DOC#: 851765

White Male

Sentencing Judge: Boone County Superior Court Judge Donald R. Peyton

Venued from DeKalb County

Trial Cause #: SCR-84-160 (Dekalb County) S-7007 (Boone County)

Prosecutor: Paul R. Cherry, Ora A. Kincaid, III

Defense: Allen F. Wharry, Douglas E. Johnston, Charles C. Rhetts

Date of Murder: April 7, 1984

Victim(s): Juan Placencia H / M / 77 (Neighbor of Woods)

Method of Murder: stabbing with knife 21 times

Trial: Information/PC for Murder filed (04-09-84); Amended Information for DP filed (04-12-84); Amended DP Information (04-26-84); Motion for Change of Venue (05-09-84, 05-31-84, 07-31-84); Change of Venue Granted (08-06-84); Amended Information filed (08-15-84); Voir Dire (02-19-85, 02-21-85, 02-22-85); Jury Trial (02-22-85, 02-23-85, 02-25-85, 02-26-85, 02-28-85, 03-01-85, 03-02-85); Verdict (03-02-85); DP Trial (03-04-85); Verdict (03-04-85); Court Sentencing (03-28-85).

Conviction: Murder, Robbery (A Felony)

Sentencing: March 28, 1985 (Death Sentence, 50 years)

Aggravating Circumstances: b (1) Robbery

Mitigating Circumstances: no prior criminal record, 19 years old at the time of the murder, mistreated as a child, raised in foster homes, personality disorder

"David Leon Woods executed for 1984 murder." (Associated Press May 3, 2007)

MICHIGAN CITY, Ind. — David Leon Woods was executed by lethal injection early Friday for killing a 77-year-old man during a 1984 burglary. Woods, 42, was pronounced dead at 12:35 a.m. Central Daylight Time, officials at the Indiana State Prison said.

The U.S. Supreme Court rejected requests that Woods' execution be stayed Thursday, as did the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals. Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels also denied clemency for Woods on Thursday. The state Parole Board had earlier unanimously recommended against granting clemency. Woods' attorneys had tried to stop the execution on the grounds that Indiana's lethal injection protocol constitutes cruel and unusual punishment. He also disputed the state court's method of determining whether he was mentally retarded, which could have rendered him ineligible for the death penalty. Federal courts won't stop execution

The U.S. Supreme Court today turned down two requests from David Leon Woods to block his execution, The Associated Press reported. Woods had challenged with the high court the state Supreme Court's method of determining whether he is mentally retarded. Separately, the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Chicago today denied the second of two requests for intervention. Today's federal court actions appeared to leave no further legal options for Woods.

Daniels won't grant clemency

Gov. Mitch Daniels today said he will not grant clemency to David Leon Woods, who is set to be executed by lethal injection early tomorrow in a 1984 murder.

Daniels said he based his decision on the parole board’s recommendation, which unanimously recommended against it, and on the wishes of the victim's family.

Barring court intervention, Woods will be put to death at the Indiana State Prison in Michigan City sometime before dawn Friday.

Woods was convicted of fatally stabbing Juan Placencia in April 1984.

Aside from his clemency bid, Woods has asked the U.S. Supreme Court to block his execution, challenging the state Supreme Court’s method of determining whether he is mentally retarded. His lawyer, Linda Wagoner, said she planned to appeal a federal court’s ruling denying a preliminary injunction to delay the execution. Should it go through, Placenia’s family will be the first to view an execution since Indiana changed its law last year giving relatives of murder victims the right to watch executions.

Sen. Tom Wyss, R-Fort Wayne, said he proposed the change after meeting with the prison warden and discovering victims’ families had to get permission from the person being put to death if they wanted to watch the execution. “The person being executed already has caused these people harm. Obviously, they’ve lost a loved one in some way, and they have to ask his permission if they feel they want to watch?” Wyss said. “It just seemed like the state was giving them another slam.”

Prison spokesman Barry Nothstine said he could recall only one execution where a victim’s family member watched. That was two years ago when Kevin A. Conner allowed relatives of three men he killed in Indianapolis to witness his death. Nothstine said Gregory Scott Johnson invited a relative of 82-year-old Ruby Hutslar of Anderson to watch his execution two years ago, but that person did not attend.

The victim’s son, Gene Placencia, who lives in Ridgecrest, Calif., said he wants to watch the execution to show support for the system. “I won’t be there because I’m bitter. I won’t be there because I hate him — I don’t care for the person, but I don’t hate him,” he said. “We’re going to be there because we need to support our courts and we need to support the laws that have been set forth.”

Placencia said not all his siblings want to watch the execution. “Some of them wanted to deal with it in another way and didn’t want to be present,” he said.

Juan Placencia’s granddaughter, Tonya Hoeffel, who was 20 when he was killed, is not eligible to watch the execution. Only spouses, parents, siblings, children and grandparents can view an execution, and all must be at least 18 years old. A maximum of eight people are allowed. Hoeffel said she would not have wanted to view Woods’ death anyway. “I don’t take any joy in knowing that someone may die on Friday,” she said. “I’m just going to support my family.”

Wyss said that was his intent when he proposed the law. “If nobody wants to go, fine. But no one should have to go before the victimizer and ask permission,” he said. Under the new law, the person being executed can have up to five people watch, down from 10 previously. To accommodate the change, the prison built a separate room for family members of the victim. Woods will be able to see the people he invited and the victim’s family members, Nothstine said.

Hoeffel’s mother, Catherine Placencia, said she has no qualms about watching the execution. “I’ve waited for this to happen for 23 years,” she said. “I’m good with it.”

"Victim's family to witness execution," by Tom Coyne. (Associated Press May 3, 2007)

SOUTH BEND, Ind. — Gene Placencia hopes to find closure by watching the man who fatally stabbed his father 23 years ago die by lethal injection early Friday. “I know because of the length of time it’s taken it will give me some closure to be there,” Placencia said. “Hopefully it will be the same for all of the family.”

Barring court intervention, Placencia and four of his 12 siblings will be at the Indiana State Prison in Michigan City early Friday for the execution of David Leon Woods, who was convicted of fatally stabbing Juan Placencia in April 1984. They will be the first to view an execution since Indiana changed its law last year giving relatives of murder victims the right to watch executions.

Sen. Tom Wyss, R-Fort Wayne, said he proposed the change after meeting with the prison warden and discovering victims’ families had to get permission from the person being put to death if they wanted to watch the execution. “The person being executed already has caused these people harm. Obviously, they’ve lost a loved one in some way, and they have to ask his permission if they feel they want to watch?” Wyss said. “It just seemed like the state was giving them another slam.”

Prison spokesman Barry Nothstine said he could recall only one execution where a victim’s family member watched. That was two years ago when Kevin A. Conner allowed relatives of three men he killed in Indianapolis to witness his death. Nothstine said Gregory Scott Johnson invited a relative of 82-year-old Ruby Hutslar of Anderson to watch his execution two years ago, but that person did not attend.

Placencia, who lives in Ridgecrest, Calif., said he wants to watch the execution to show support for the system. “I won’t be there because I’m bitter. I won’t be there because I hate him — I don’t care for the person, but I don’t hate him,” he said. “We’re going to be there because we need to support our courts and we need to support the laws that have been set forth.”

Woods has asked the U.S. Supreme Court to block his execution, challenging the state Supreme Court’s method of determining whether he is mentally retarded. His lawyer, Linda Wagoner, said she plans Thursday to appeal a federal court’s ruling denying a preliminary injunction to delay the execution. Woods also is waiting for Gov. Mitch Daniels to decide whether to grant him clemency. The state Parole Board unanimously recommended against it.

Placencia said not all his siblings want to watch the execution. “Some of them wanted to deal with it in another way and didn’t want to be present,” he said. Juan Placencia’s granddaughter, Tonya Hoeffel, who was 20 when he was killed, is not eligible to watch the execution. Only spouses, parents, siblings, children and grandparents can view an execution, and all must be at least 18 years old. A maximum of eight people are allowed. Hoeffel said she would not have wanted to view Woods’ death anyway. “I don’t take any joy in knowing that someone may die on Friday,” she said. “I’m just going to support my family.”

Wyss said that was his intent when he proposed the law. “If nobody wants to go, fine. But no one should have to go before the victimizer and ask permission,” he said. Under the new law, the person being executed can have up to five people watch, down from 10 previously. To accommodate the change, the prison built a separate room for family members of the victim. Woods will be able to see the people he invited and the victim’s family members, Nothstine said.

Hoeffel’s mother, Catherine Placencia, said she has no qualms about watching the execution. “I’ve waited for this to happen for 23 years,” she said. “I’m good with it.”

"Murderer apologized before he was executed. (May 5, 2007)

Michigan City -- Gene Placencia wanted David Leon Woods to look him in the eye before Woods was put to death by injection for killing Placencia's father 23 years ago. He settled for watching Woods die. "My dad's spirit can rest now," Placencia said. "My father was taken from us in 1984. When we had his funeral, he didn't rest in peace. I would say today I would put a little date on there of May 4th, 2007, as when his spirit will rest."

Woods, 42, died at 12:35 a.m. Friday. He was executed for killing Juan Placencia, a 77-year-old neighbor, in Garrett, about 10 miles north of Fort Wayne. Woods stabbed Placencia 21 times during a burglary.

Woods apologized before his execution. "I want Juan's family to know I truly am sorry, and I do have remorse," Woods said.

Placencia and four siblings were the first to watch an execution under a new law that gives up to eight spots to immediate family members of murder victims. The Placencias said they were glad they attended the execution. "Like my brother Gene said, I feel closure," said Rick Placencia, Garrett.

"Judge refuses to block execution," by Jon Murray. (May 2, 2007)

Attorneys for a Death Row inmate facing execution this week plan to appeal a court ruling rejecting his claim he would suffer unnecessarily as he dies. U.S. District Judge Richard L. Young on Tuesday denied David Leon Woods' request for a preliminary injunction in a lawsuit challenging Indiana's lethal injection procedures. He and two other inmates argue those constitute cruel and unusual punishment. "Woods has not shown the existence of irreparable harm through the mere possibility that some unforeseen complication will result in a lingering death causing Woods to suffer unnecessary pain," Young wrote in a 12-page ruling. Woods, 42, faces execution early Friday for the 1984 stabbing death of his 77-year-old neighbor, Juan Placencia, in Garrett, north of Fort Wayne.

Linda Wagoner, one of Woods' attorneys, said she was disappointed with the ruling and planned to file an appeal today with the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Chicago. Woods' attorneys also have asked that court and the U.S. Supreme Court to review rulings in other cases. Young issued a separate ruling Tuesday denying the Indiana attorney general's request for a summary judgment. Staci Schneider, the attorney general's spokeswoman, declined to comment.

Gov. Mitch Daniels has not announced a clemency decision, though the state Parole Board unanimously recommended against it last week.

"Peace, remorse mark murderer’s final day," by Angela Mapes. (May 5, 2007)

MICHIGAN CITY – David Leon Woods spent the day leading up to his execution in a calm mood, Indiana State Prison officials said. “He told me this morning that he’s going to a better place, and he stayed that way throughout the day,” prison spokesman Barry Nothstine said late Thursday as prison officials prepared for Woods’ execution.

Woods, 42, was pronounced dead by lethal injection at 1:35 a.m. Fort Wayne time Friday, his sentence for the 1984 slaying of 77-year-old Juan Placencia of Garrett served after more than two decades.

Woods shared a last meal of birthday cake and pizza with his family Wednesday. Prison officials had him on a liquid diet Thursday. His pet cat – a recent allowance for death-row inmates – was willed to a family member and had been taken from the prison Thursday afternoon, Nothstine said.

Five of Placencia’s children watched the execution. Three of his sons spoke with reporters and protesters in the chilly, dark parking lot outside the prison after Woods died. Gene Placencia of Ridgecrest, Calif., who bears a resemblance to his father, said he’d hoped Woods would see his face before he died. Woods didn’t, but the execution still gave Gene Placencia closure, he said.

Woods acted as “judge, jury and executioner” when he stabbed Juan Placencia 21 times while breaking into the older man’s apartment but was given fair treatment by the state of Indiana, Gene Placencia said. The Placencia family now can begin a years-delayed healing process now that Woods has been punished for his crime, he said. “We’re not here because we hate this guy,” he said.

Gene Placencia said he will mark May 4, 2007, as the date that his father’s spirit finally rested in peace. But other Placencia family members still struggled with their anger, said son David Placencia, who said he hasn’t forgiven Woods.

Attorney William Van Der Pol Jr. spoke on behalf of Woods’ family after the execution. “Tonight should not be about retribution for the past, but hope for the future,” he said.

In a final statement, Woods said he had remorse for the killing and apologized to Placencia’s family. “I want everybody to know that I do have peace, and it’s through Jesus Christ that I have this peace,” he said. Gov. Mitch Daniels on Thursday denied clemency for Woods after the parole board unanimously recommended against clemency.

Woods was the first Indiana inmate put to death since January 2006.

"Executions set record pace under Daniels," by Niki Kelly. (Posted on Fri, May. 04, 2007)

INDIANAPOLIS – David Leon Woods’ death would be the seventh execution since Mitch Daniels became governor in January 2005 – a historic pace after three years in office. His term so far includes five executions in 2005 and one in 2006.

Former Gov. Frank O’Bannon – who died in 2003 – oversaw seven executions during his roughly seven years in office. Former Govs. Evan Bayh and Robert Orr each supervised two executions each during their eight-year terms. Joe Kernan did not go through an execution during his year in office, although he commuted two death sentences.

Daniels has also commuted one sentence – Arthur Baird II in 2005.

With the recent decision by a federal court to throw out Joseph Corcoran’s death sentence, Woods is the last northeast Indiana man on death row. Corcoran’s case is being appealed by the state, though.

It’s unclear who the next man who might be executed is, but Norman Timberlake had his 2007 date stayed by a federal judge pending a U.S. Supreme Court decision on executing the mentally ill. Michael Allen Lambert has also joined Timberlake’s suit and is near the end of his appeals.

"Indiana death row actions." (Associated Press Posted on Fri, Jan. 27, 2006)

Six Indiana death row inmates have been executed since Gov. Mitch Daniels took office in January 2005. Last year's five executions were the most since the state re-instituted the death penalty in 1977. Daniels blocked the execution of another condemned inmate:

Executed:

_ Donald Ray Wallace, March 10, 2005, for the 1980 slayings of Patrick and Theresa Gilligan of Evansville and their two children.

_ Bill J. Benefiel, April 21, 2005, for the 1987 torture-slaying of 18-year-old Dolores Wells of Terre Haute.

_ Gregory Scott Johnson, May 25, 2005, for the 1985 beating death of 82-year-old Ruby Hutslar of Anderson during a burglary of her home. Johnson had sought a reprieve from Daniels in order to donate his liver to his sister.

_ Kevin A. Conner, July 27, 2005, for the 1988 murders of three Indianapolis men following an argument.

_ Alan L. Matheney, Sept. 28, 2005, for killing his ex-wife, Lisa Bianco, outside her Mishawaka home in 1989 while he was free from prison on an eight-hour pass.

_ Marvin E. Bieghler, Jan. 27, 2006, for the 1981 shooting deaths of Tommy Miller and his pregnant wife, Kimberly Jane Miller, at their Russiaville home. Commuted to life in prison:

_ Arthur P. Baird II, convicted for 1985 murders of his wife, who was seven months pregnant, and his parents in Montgomery County, granted clemency by Daniels on Aug. 29, 2005.

"Woods executed for 1984 murder of neighbor," by Tom Coyne. (AP Friday, May 4, 2007 9:39 AM CDT)

MICHIGAN CITY, Ind. - Gene Placencia wanted David Leon Woods to look him in the eye before he was put to death by injection for killing Placencia's father 23 years ago. He settled for watching Woods die. "My Dad's spirit can rest now," Placencia said. "My father was taken from us in 1984. When we had his funeral, he didn't rest in peace. I would say today I would put a little date on there of May 4, 2007, as when his spirit will rest."

Woods, 42, died at 12:35 a.m. Friday. He was executed for killing Juan Placencia, a 77-year-old neighbor, in Garrett, about 10 miles north of Fort Wayne. Woods stabbed Placencia 21 times during a burglary.

People who saw Woods on Thursday said he was at peace. Prison spokesman Barry Nothstine said Woods was just the second condemned inmate he had dealt with who showed no sign of worry or trepidation that he was about to die. "He was very calm, pleasant, relaxed," Nothstine said. "He expressed many times that he's found religion. He told me ... he was going to a better place."

Woods displayed his faith in his final statement. "I want everybody to know that I do have peace and it's through Jesus Christ that I have this peace," he said. Woods also apologized. "I want Juan's family to know I truly am sorry and I do have remorse," Woods said.

David Placencia, from Bakersfield, Calif., said he can't forgive Woods for his father's slaying. "I'm not one to forgive," he said. Gene Placencia, who lives in Ridgecrest, Calif., said Woods' death gives him peace. "I have closure. I can finally get on with my life, raise my kids, run my business and love my family," he said.

Placencia and four siblings were the first to watch an execution under a new law that gives up to eight spots to immediate family members of murder victims. In the past, victim's family members would have to ask the condemned inmate for permission to attend. The Placencias said they were glad they attended the execution. "Like my brother Gene said, I feel closure," said Rick Placencia of Garrett.

Woods' attorneys had tried to stop the execution on the grounds that Indiana's lethal injection protocol constitutes cruel and unusual punishment. Woods also disputed the state court's method of determining whether he was mentally retarded, which could have rendered him ineligible for the death penalty.

Woods' attorney, William Van Der Pol, Jr., spoke on behalf of Woods' family. "Tonight should not be about retribution for the past but hope for the future," he said. "Society should not take great solace or great glee in David's passing this evening."

Three of Woods' family members were among about 25 people who protested against the death penalty Thursday night outside the prison. Woods' brother-in-law, Tommy Yeager, said Woods hopes the Placencia family will forgive him. "David is not mad at them at all," Yeager said. "He understands their sorrow, and he hopes someday they can forgive him."

Woods was the first person put to death in Indiana since Marvin Bieghler on Jan. 27, 2006. Before that, the state executed five people in seven months in 2005. That was the most in one year in Indiana since 1938, when eight men were electrocuted over nine months.

"Board rejects condemned inmate's clemency request," by Emily Udell. (AP Monday, April 23, 2007 5:37 PM CDT) Post a Comment | Email this story | Print this story

INDIANAPOLIS | The Indiana Parole Board on Monday refused to recommend clemency for a man set to be executed next week in the stabbing death of his 77-year-old neighbor.

David Leon Woods, 42, was sentenced to death in March 1985 for the slaying of Juan Placencia in the northeastern Indiana town of Garrett 11 months earlier. After listening to about three hours of testimony, the Parole Board unanimously recommended to Gov. Mitch Daniels that Woods' life not be spared. "Testimony and evidence provided concerning Mr. Woods' horrible childhood and appalling living conditions is merely an attempt to place blame where blame should not lie," board member Thor Miller said

Daniels plans to review the board's recommendation and other information on the case before making a decision on whether to allow the execution to proceed as scheduled on May 4 at the Indiana State Prison, said Jane Jankowski, the governor's spokeswoman. He can choose to accept or reject the board's recommendation.

William Van Der Pol Jr., an attorney for Woods, said he was disappointed by the board's vote. "It seems sad that we're going to execute a fundamentally flawed and injured individual who committed a crime when he was 19 years old," Van Der Pol said

Woods' relatives, attorneys and others who knew him asked the board to recommend clemency, describing Woods' childhood as one marred by abuse, neglect and stints in foster care. "David had absolutely zero love in his life," said Wanda Callahan, Woods' pastor on death row. "He told me time and time again that he didn't feel safe until he was on death row." Woods attorneys also said he suffered brain disfunction and had not adequate legal representation.

Members of the Placencia family, wearing buttons with Juan Placencia's picture, said they believed Woods deserved execution. "Nobody forced David Woods to stab my grandfather 21 times while he pleaded for help," said Glenn McDonald, who was 14 at the time of the murder.

According to testimony Monday, Woods stabbed Placencia repeatedly in the face, neck and torso after forcing his way into Placencia's home. He took $130 from Placencia's wallet and a television that he later sold for $20. Woods told the Parole Board during a hearing Friday at the state prison in Michigan City that he went to Placencia's home to retrieve some items his mother had left at her former boyfriend's house. He said she told him no one would be home.

Woods said he had been drinking and using drugs before going to Placencia's house where he stabbed the man once in the stomach and then again when a friend told him to silence him. Woods apologized to his family and to Placencia's on Friday and told the Parole Board that he found religion while in prison.

Woods' attorneys also have asked a federal judge to delay the execution, contending that the state Department of Correction's lethal injection protocol constitutes cruel and unusual punishment. A preliminary injunction hearing is scheduled for that case on Thursday, Van Der Pol said.

Indiana governors have commuted three death sentences in the past 50 years -- all three in the past three years. Six inmates have been executed since Gov. Mitch Daniels took office in January 2005.

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

David Woods, May 4, IN

Do Not Execute David Woods!

Indiana is scheduled to execute David Woods on May 4 for the April 1984 murder and robbery of Juan Placencia in Garrett, IN.

The state of Indiana should not execute David Woods for his role in this crime. Executing Woods would violate the right to life as declared in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and constitute the ultimate cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment. Furthermore, Woods was 19 years old at the time of the crime without a prior criminal record. He was raised in foster homes and suffers from a personality disorder.

Please write to Gov. Mitch Daniels on behalf of David Woods!

"Doctor: Lethal injections are 'catastrophically flawed'; But state prison officials testify inmates will be fully sedated before execution," by Jon Murray. (April 27, 2007)

A doctor testifying Thursday in a lawsuit challenging Indiana's use of lethal injections in death penalty cases called state practices "catastrophically flawed." But officials from the Indiana State Prison in Michigan City said they are confident that David Leon Woods, one of three Death Row inmates challenging the state's system, will be fully sedated May 4 before another chemical is injected into him to stop his heart. With Woods' execution looming, U.S. District Judge Richard L. Young is expected to rule soon on Woods' request for a preliminary injunction. Young heard testimony during Thursday's daylong hearing.

The lawsuit, filed by fellow inmate Norman Timberlake in December, argues that the procedures and chemicals used in Indiana executions don't guard against unnecessary pain, constituting cruel and unusual punishment. During the hearing, Linda Wagoner, one of Woods' attorneys, also questioned the qualifications of the three-person team that injects the sequence of chemicals that sedate, paralyze and finally kill the prisoner.

Woods, 42, was convicted in the 1984 stabbing death of 77-year-old neighbor Juan Placencia in Garrett, north of Fort Wayne. Prison Superintendent Ed Buss, who stands at the foot of the gurney for all executions, said he and others who participate take their roles seriously. They aren't doctors, but they train monthly, with sessions twice a week leading up to an execution and a dress rehearsal just hours before.

Doctors don't take active roles in executions because of ethical concerns voiced by national medical associations. But during Indiana's executions, Buss said, a physician watches 7 feet away from the gurney, behind a window, and can intervene if there is a problem.

The inmates' attorneys countered with testimony from Dr. Mark Heath, an anesthesiologist at Columbia University in New York, who has testified in about 10 death penalty cases. He said the three-drug combination used by nearly every state with lethal injection -- including Indiana -- is poorly calibrated, increasing the risk that the anesthetic won't take hold or other problems will crop up. Heath also questioned whether Buss and others viewing the execution are trained to judge whether a prisoner is adequately sedated.

Officials have recently changed execution plans. For Woods, they plan to double the dose of anesthetic and will place an ammonia tablet under his nose to verify that he's sedated. "We looked at experts' testimony in other states," Buss said, and decided the new amount, 5 grams of sodium pentothal, was certain to be effective. "It's an increased safety margin," Heath said of the higher dose. "But in the absence of verifying the anesthetic depth in a meaningful way, it doesn't matter."

Heath said the second paralyzing drug -- used to keep the inmate from convulsing -- could prevent one who isn't adequately sedated from grimacing or showing other signs of consciousness. Concerns about lethal injection have prompted 11 states to suspend executions, by court order or on their own. But Buss and other officials defend Indiana's procedures.

State attorneys argued that Woods had not filed a prison grievance complaint about the execution procedures before he and inmate Michael Allen Lambert asked to join Timberlake's lawsuit in March. Woods filed a grievance Wednesday. Woods' attorneys continue to seek delays in his execution. But earlier this month, the inmate expressed resignation. He received a letter from prison officials that summarized a meeting in which they had explained the events of the coming weeks to him. At the bottom, he scrawled: "Done deal."

WHAT'S NEXT

David Leon Woods is scheduled to be executed May 4 at the Indiana State Prison in Michigan City.

• Courts: Woods' attorneys are seeking a delay from a judge hearing a lawsuit challenging Indiana's lethal injection procedures. They also have asked the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Chicago and the U.S. Supreme Court to review lower-court rulings against Woods.

• Clemency: Earlier this week, the Indiana Parole Board unanimously recommended that Gov. Mitch Daniels reject Woods' application for clemency. Daniels has not announced a decision.

"Lawyers question execution change; Adding more anesthetic won't matter, they say," by Jon Murray. (April 20, 2007)

Convicted killer David Leon Woods will be given twice as much anesthetic as other inmates Indiana has put to death when he is executed by injection next month. The change in the three-drug execution cocktail could ensure he won't feel pain, but it has puzzled attorneys for Woods and other Death Row inmates suing over Indiana's lethal-injection procedure.

The issue of proper drug dosing is one of several threatening to make Indiana executions inhumane and cruel, argues the federal lawsuit, filed in December by fellow Death Row inmate Norman Timberlake. Woods and Michael Lambert joined the suit this month. Such concerns have led 11 states, by court order or on their own, to suspend lethal injections. The attorneys said Indiana's adjustment would make little difference. "My understanding is that the most frequent problem is leaking or collapsing veins, and there have been some flow problems," said Linda Wagoner, one of Woods' two attorneys. "Increasing the dosage of the particular drug does not address either of those concerns."

Woods, 42, faces execution May 4 for the 1984 stabbing death of a 77-year-old neighbor, Juan Placencia, in Garrett, a town north of Fort Wayne. Woods requested a preliminary injunction this week, asking U.S. District Judge Richard L. Young to suspend his execution until Indiana adjusts its procedures.

State attorney Thomas Quigley disclosed the recent change to execution protocol April 13 during a telephone conference with Wagoner and the judge. According to a court document summarizing the discussion, the Indiana State Prison in Michigan City has increased the amount of sodium pentothal -- the first chemical injected -- to 5 grams from 2.5 grams. The barbiturate serves as a sedative. Two substances are then injected, to paralyze the muscles, then to stop the heart. Woods' attorneys have asked the state to explain in writing why the dose was changed and whether evidence backs up its effectiveness.

Java Ahmed, a spokeswoman for the Indiana Department of Correction, attributed the change to a recent review of the protocol. Officials regularly look at staffing, procedures and equipment "to ensure that the department is implementing the best available practices," she said in an e-mail. Many states already use Indiana's new dose of the drug, though others have given inmates a smaller amount than Indiana's old dose.

Little input on the drugs, their use or dosages has come from medical doctors. They often refuse to take part in executions out of ethical concerns in a profession that aims to protect the health of patients. Critics of lethal-injection procedures nationally point out that the same sequence of drugs has been used for decades, simply passing from state to state without a complete medical review. "It's close to a medical procedure, and it's being performed by nonmedical personnel," said Richard Dieter. He is the executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center in Washington, which is critical of how states carry out lethal injections. Brent Westerfeld, Timberlake's attorney, said Indiana's decision to change one drug dose showed arrogance when other states have halted executions to thoroughly review all procedures.

PAROLE BOARD INTERVIEW TODAY

David Leon Woods has applied for clemency as his May 4 execution nears.

• Clemency: The state Parole Board will interview Woods at Indiana State Prison today. The board will hear testimony Monday at the Indiana Government Center South in Indianapolis before voting on its recommendation to the governor.

• Lawsuit: Woods has joined another Death Row inmate's federal lawsuit challenging how Indiana carries out lethal injections. If the judge grants a preliminary injunction, Indiana would not be able to execute Woods until it revamps its execution procedures.

• Petition: Woods has asked for another appeal and a stay of execution pending the outcome of a U.S. Supreme Court case dealing with mentally ill inmates.

Sources: Electronic court records, Indiana Department of Correction

"My Dad’s spirit can rest now," by Bob Wellinski. (Posted Online: 5-4-2007)

MICHIGAN CITY -- Gene Placencia wanted David Leon Woods to look him in the eye before he was put to death by injection for killing Placencia’s father 23 years ago. He settled for watching Woods die. “My Dad’s spirit can rest now,” Placencia said. “My father was taken from us in 1984. When we had his funeral, he didn’t rest in peace. I would say today I would put a little date on there of May 4, 2007, as when his spirit will rest.”

Woods, 42, died at 12:35 a.m. Friday. He was executed for killing Juan Placencia, a 77-year-old neighbor, in Garrett, about 10 miles north of Fort Wayne. Woods stabbed Placencia 21 times during a burglary.

People who saw Woods on Thursday said he was at peace. Prison spokesman Barry Nothstine said Woods was just the second condemned inmate he had dealt with who showed no sign of worry or trepidation that he was about to die. “He was very calm, pleasant, relaxed,” Nothstine said. “He expressed many times that he’s found religion. He told me ... he was going to a better place.”

Woods displayed his faith in his final statement. “I want everybody to know that I do have peace and it’s through Jesus Christ that I have this peace,” he said. Woods also apologized. “I want Juan’s family to know I truly am sorry and I do have remorse,” Woods said.

Woods’ mother, Mary Lou Pilkington, spoke to the media shortly before her son’s execution. “I’m gonna miss my son very much,” she said. “We love him.” Mary Anne Pilkington-Yeager, Woods’ sister, said she would miss her brother, whom she called her spiritual guide. “I know for a fact that (Juan Placencia) would not have wanted this,” she said.

David Placencia, from Bakersfield, Calif., said he can’t forgive Woods for his father’s slaying. “I’m not one to forgive,” he said. Gene Placencia, who lives in Ridgecrest, Calif., said Woods’ death gives him peace. “I have closure. I can finally get on with my life, raise my kids, run my business and love my family,” he said.

Placencia and four siblings were the first to watch an execution under a new law that gives up to eight spots to immediate family members of murder victims. In the past, victim’s family members would have to ask the condemned inmate for permission to attend. The Placencias said they were glad they attended the execution.

Woods’ attorneys had tried to stop the execution on the grounds that Indiana’s lethal injection protocol constitutes cruel and unusual punishment. Woods also disputed the state court’s method of determining whether he was mentally retarded, which could have rendered him ineligible for the death penalty.

Woods’ family members, including his mother, sister and brother-in-law, Tommy Yeager, were among about 25 people who protested against the death penalty Thursday night outside the prison. Yeager said Woods hopes the Placencia family will forgive him. “David is not mad at them at all,” Yeager said. “He understands their sorrow, and he hopes someday they can forgive him.”

Woods’ last meal was pizza, according to Nothstine.

Woods was the first person put to death in Indiana since Marvin Bieghler on Jan. 27, 2006. Before that, the state executed five people in seven months in 2005. That was the most in one year in Indiana since 1938, when eight men were electrocuted over nine months.

Indiana Parole Board Rejects Clemency

The Honorable Mitchell E. Daniels, Jr., Governor.

State of Indiana

Room 206, State House

Indianapolis, Indiana 46204

April 23, 2007

Dear Governor Daniels,

The hearing process required by statute as a result of the filing of a Petition forClemency by David Leon Woods, DOC 851765, has been completed. Mr. Woods'petition seeks a reprieve and/or commutation of the sentence of death resulting from hisconviction by a jury in Boone County Superior Court of the murder by multiple stabwounds of Juan V. Placencia, 77, neighbor and friend of the petitioner.

The petition submitted on behalf of Mr. Woods focuses primarily on two issues which compels him to seek clemency. The first issue is the potential that the petitioner may be classified as suffering from mental retardation warranting a review of the appropriateness of this sanction of death. The second issue is the professional incompetence of his legal counsel at both the trial and appellate levels.

On Friday, April 20, 2007, the Indiana Parole Board convened in session at the Indiana State Prison in Michigan City, Indiana to personally interview David LeonWoods. Mr. Woods indirectly responded to the first issue of his petition for clemency concerning his mental capacity as he presented a very verbal person who not only responded quite appropriately and sufficiently to questions but led the discussion as necessary. He was not only able to assist in this inquiry without any assistance or even any apparent need for assistance but was very intellectual and philosophical about his life and the presenting event. His level of understanding, his introspection, and his assessment of others in his life leads me to believe that Mr. Woods' mental capacity is more than sufficient not only to understand the correlation between his actions and logical consequences but he also appears to be a person who holds a personal peace after significant, in-depth, and introspective review of his life's situations.

No testimony offered this date significantly altered my assessment of Mr. Woods based upon his interview. Following the completion of the interview of April 20, 2007 and today's presentation, it appeared that the second issue has been fully addressed as well. The adequacy of Mr. Woods' legal counsel may have been assessed by some as potentially insufficient. Yet, still others believe that such is not the case. Competent legal counsel is essential to avoid any occurrence of any person being sanctioned in any form for an act that was accomplished by anyone other than the accused. However, if one were qualified to sit in judgment on the competency of the legal counsel in question, they would also have to be learned enough to dignify the result of this trial and appeals process as appropriate.

Ultimately, this trial process yielded a decision that reflected the most basic of legal concerns—the truth was accurately discovered in this case. David Leon Woods attempted to break into the home of Juan V. Placencia. Upon being surprised by Mr.Placencia, Mr. Woods stabbed Mr. Placencia in the abdomen with the approximate four inch knife that he had brought with him from his home. While Mr. Placencia fell backinto his chair with a potentially mortal wound pleading with Mr. Woods to now help him, Mr. Woods began to steal items from Mr. Placencia's home. When satisfied with his thefts, Mr. Woods returned to Mr. Placencia but not to help despite the elderly man's pleas but to stab him 20 additional times leaving him for dead.

After great deliberation, I find no compelling reason to request that the existing sentence of death imposed by ajury be altered due to the nature and circumstances of this crime. I recommend that the Petition for Clemency be denied.

Sincerely,

Christopher E. Meloy, Chairman

Woods v. State, 547 N.E.2d 772 (Ind. November 28, 1989) (Direct Appeal).

Following a jury trial, the Boone Superior Court, Donald R. Payton, J., convicted defendant of knowing and intentional killing, robbery, and serious bodily injury. Following another jury trial, the Court ordered death on the murder charge and 50 years on the robbery and bodily injury charges. Defendant appealed. The Supreme Court, DeBruler, J., held that: (1) possible seizure of defendant by police was justified by probable cause; (2) prosecutor's arguments to the jury did not constitute cause for mistrial or undermine the reliability of the jury's death sentence recommendation; (3) finding that defendant had intentionally killed victim while in the course of a robbery, for purposes of proving an aggravating circumstance to impose death penalty, was supported by the evidence; (4) imposition of death penalty was appropriate in that aggravating circumstance of stabbing and killing victim in the course of a robbery outweighed the mitigating circumstances; (5) instruction on jury's duty was proper in the penalty phase of the murder trial; (6) defendant's right to trial by jury before a jury selected from a fair cross section of the community was not violated by exclusion of persons who had served as jurors within preceding year; (7) trial court's finding that murder defendant was competent to stand trial was supported by the evidence; (8) trial court's allowance of testimony of accomplice of defendant was not error; (9) trial court did not abuse its discretion in refusing defendant's request for a psychiatric examination; (10) trial court's decision to appoint only one of defendant's two trial counsel to prepare motion to correct errors was reasonable; (11) incorporation of evidence from guilt phase of murder prosecution to penalty phase did not create danger of arbitrariness or capriciousness; and (12) conviction of defendant for robbery and intentional killing in course of robbery violated double jeopardy, requiring sentence of 50 years for robbery to be vacated. Convictions of robbery and murder affirmed, imposition of sentence of death affirmed.

DeBRULER, Justice.

Appellant was charged in Count I pursuant to I.C. 35-42-1-1(1) with the knowing and intentional killing of Juan Placencia, *778 and in Count II pursuant to I.C. 35-42-5-1 with the robbery and serious bodily injury of the same victim, a Class A felony. In a separate request for a sentence of death, the prosecution alleged pursuant to I.C. 35-50-2-9(b)(1) the aggravating circumstance that appellant committed an intentional killing while committing robbery.

A trial by jury resulted in verdicts of guilty as charged in Counts I and II. Judgments were then entered on the verdicts. Two days later, the jury reconvened for the penalty phase of the trial. Following the presentation of evidence, the jury retired and then returned a verdict recommending the death penalty.

The cause then came on for sentencing. The trial court expressly found that the State proved beyond a reasonable doubt that appellant intentionally killed the victim while committing robbery. The court further concluded that the mitigating circumstances were outweighed by the single aggravating circumstance and ordered death on Count I and fifty years on Count II.

The evidence adduced at the trial viewed most favorably to the verdict shows that the following events transpired. At approximately 4:00 a.m. on April 7, 1984, appellant David Woods, along with Greg Sloan and Pat Sweet, proceeded to the apartment of the victim, Juan Placencia, to steal a television. This occurred in Garrett, Indiana, a small town. Placencia was a seventy-seven-year-old man who had medical problems with a knee. Woods, nineteen years old at the time, was armed with a knife and told Sloan and Sweet that he was going to scare Placencia with it.

Sweet stayed in the yard. Appellant Woods and Sloan approached the door of the apartment and rang the bell. Placencia answered the door, whereupon appellant Woods immediately jumped in and stabbed him several times with the knife. Placencia fell back into a chair, directed them to his money, and began to make noise, asking for help. Woods took the money from Placencia's wallet and then stabbed him again repeatedly. Placencia died from three wounds which pierced his heart. Woods and Sloan carried out the television and hid it in a trash bin. Later they picked it up and sold it. They also washed their clothes and threw the knife and other items in a creek.

We are presented with twenty-nine issues in this appeal.

The first appellate claim is that the trial court committed error when overruling appellant's motion to suppress and trial objections to the admission of his confession, the statements of certain witnesses, and certain items of physical evidence, all of which are asserted to be the direct product of his illegal arrest and detention. The Fourth Amendment requires that an arrest or detention for more than a short period be justified by probable cause. Probable cause to arrest exists where the facts and circumstances within the knowledge of the officers or of which they have reasonably trustworthy information are sufficient to warrant a belief by a person of reasonable caution that an offense has been committed and that the person to be arrested has committed it. Brinegar v. United States, 338 U.S. 160, 69 S.Ct. 1302, 93 L.Ed. 1879 (1949). Limited investigatory seizures or stops on the street involving a brief question or two and a possible frisk for weapons can be justified by mere reasonable suspicion. Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1, 88 S.Ct. 1868, 20 L.Ed.2d 889 (1968). There is no seizure and thus no requirement of justification when a suspect freely and voluntarily accompanies police officers or shows up at the police station in response to an invitation and is questioned without restraint. Oregon v. Mathiason, 429 U.S. 492, 97 S.Ct. 711, 50 L.Ed.2d 714 (1977); Dillon v. State (1983), Ind., 454 N.E.2d 845; Barber v. State (1981), Ind.App., 418 N.E.2d 563.

At approximately 9:45 a.m. on the same morning, responding to the report of a man needing help, Officer Kleeman of the Garrett police went to Palencia's apartment building and discovered appellant Woods there on a porch crying and incoherent, mumbling something on the order of “Why did it have to be him.” Kleeman had no idea what the problem was. Another person appeared and led Kleeman to the Placencia apartment. Kleeman told appellant to stay on the porch. After Kleeman entered the apartment and saw the body, he reported in and returned to the porch to question Woods about why he had been at the apartment. Woods responded that he had gone to the apartment to use the phone, had discovered the body, and had run from the apartment yelling for help.

Within a few minutes, Kleeman asked appellant to go to a police car away from the onlookers, including relatives of Placencia who had gathered, for further questioning. Appellant was given his Miranda rights; he said that he understood them and wanted to waive them. He said that he would talk to police and that he would be more than glad to help them in any way. Appellant was questioned for about a half hour in the car, essentially describing his discovery of the body and adding that he had been with Sloan and Sweet the night before. He was not arrested or physically restrained in any manner.

While appellant was being questioned in the police car, his mother appeared at the scene and told the police that she felt her son had been involved in the killing. She said he had been in and out of their house during the previous night asking for dark clothes and gloves and that he talked nervously about needing money and killing someone. He had talked about killing a woman who lived above Placencia in the same apartment house. She made this statement at about 10:20 a.m. and was transported to the police station where, at 10:40 a.m., she added to her previous statement that appellant had gone to the basement and awakened his brother and that at 7:00 a.m., he had come into the house again and seemed to be troubled about something. She signed a consent to search her house.

In the meantime, at the crime scene at 10:50 a.m., appellant was left alone in the police car after having been cooperative. Within five minutes, appellant, without being arrested or restrained, but without being told that he was free to go, was driven by another officer to the Garrett police station two blocks away. An officer testified that if appellant had sought to leave, he probably would not have grabbed hold of him, but would have asked him to stay until he had conferred with other officers.

Appellant arrived at the police station at about 10:52 a.m. and was escorted by the driver, who was in plain clothes, into the office of the chief. The driver was under instructions to stay with appellant and not engage him in any conversation or permit any one else to engage him in conversation. Appellant was permitted to go into an adjoining toilet and read a newspaper until Officer Kleeman arrived at about 11:50 a.m. He was again given his Miranda rights and signed a waiver of rights and a consent to search his residence. He was asked to and did empty his pockets. He had two black pills and a wallet containing $160.00. His wallet and money were returned to him, but the pills were not. Appellant permitted the officer to examine his arms and torso. During this interrogation, appellant asked no questions, was not hesitant, and posed no opposition to anything that was taking place. It was not announced that he was under arrest, and he was not restrained by handcuffs or other devices. He was not told that he was free to go at any time nor was he told that he was not free to go. Appellant basically repeated his former claim of having discovered the body and was left in the office with yet another officer at a few minutes after noon.

At 12:55 p.m., a search of the residence of appellant and his mother produced a knife sheath and a stained towel, among other items. At 1:00 p.m., another person in appellant's residence confirmed that appellant had spoken and acted the night before in the manner attributed to him by his mother in her statement. At 1:20 p.m., one Krotzer gave a statement to police that appellant and Greg Sloan had appeared at his house at 5:00 a.m. and asked to borrow his car to haul a television.

At 4:45 p.m., appellant was still being held in the chief's office and was again interrogated after having again been read his Miranda rights and making an explicit waiver. As new pieces of evidence were worked into the interrogation, appellant's story began to change. A lie detector test was scheduled at the state police post for 8:00 p.m. Appellant was transported in handcuffs to the post where, while answering general questions in preparation for being attached to the machine, he broke down, confessing that he had gone with Sloan to the Placencia apartment to steal a television, had knocked on the door, and had stabbed Placencia as he answered the door and again inside the apartment. Appellant was returned to the county jail where he was formally arrested.

The evidence brought out during the hearing on the motion to suppress, which distinguishes this case from those in which a seizure of the person was held invalid because of the absence of probable cause, was appellant's status as the first person to discover a homicide, appellant's presence at the crime scene shortly after the crime, and the incriminating statements of appellant's mother to the officers at the crime scene and at the police station. In Dunaway v. New York, 442 U.S. 200, 99 S.Ct. 2248, 60 L.Ed.2d 824 (1979), the police received a tip from an informant and a statement from a jail inmate that Dunaway was implicated in a crime which had occurred four months before. The police simply took him into custody, drove to police headquarters, and gave him his Miranda rights, which he waived. He then made an incriminating statement later admitted at trial. In Brown v. Illinois, 422 U.S. 590, 95 S.Ct. 2254, 45 L.Ed.2d 416 (1975), Brown was arrested in his own apartment for murder a week after the crime because he was on a list of names of acquaintances of the victim. In Davis v. Mississippi, 394 U.S. 721, 89 S.Ct. 1394, 22 L.Ed.2d 676 (1969), a rape victim described her assailant as a Negro youth, and appellant, a Negro youth who had occasionally done yard work for the victim, was picked up on the street, taken to headquarters, fingerprinted, interrogated, and released. In none of these cases were there facts and circumstances known to the officers which would have caused a person of ordinary caution to believe that the suspect had committed the crime under investigation. Here, by contrast, the officers heard from the mother that appellant had planned to rob and kill a woman the night before, discussing different ways of doing so and collecting the means for doing so. It was his habit to be up and about at night and to sleep in the daytime. She then heard him in the basement attempting to wake up his brother. At 7:00 a.m., he returned home again and appeared troubled and told his mother to wake up the children, although it was not a school day. He also said he wanted to go over to Juan Placencia's to use the phone. The mother also supplied information from which the police could infer that Placencia's television had been taken in the attack, and thus that one of the motives in the attack was theft, the motive which appellant had revealed the night before. This information, coming as it did from appellant's mother, who lived in the victim's neighborhood in this small town and knew the victim and appellant well, was the sort of report which in common experience is regarded as having a reliable quality. Whiteley v. Warden, 401 U.S. 560, 91 S.Ct. 1031, 28 L.Ed.2d 306 (1971). When her report is considered together with appellant's presence and behavior at the crime scene shortly after the killing, the body of information as a whole was such that from it, a person of ordinary caution would be led to believe that appellant had been involved in the criminal activity at that apartment house resulting in the death of Mr. Placencia.

Assuming therefore, without explicitly deciding, that appellant was seized when transported from in front of the apartment house to the police station for further intensive interrogation, such seizure was justified by probable cause. Appellant points out that the police did not attempt at the suppression hearing or at trial to justify their conduct by claiming probable cause and that it would not therefore be proper to sustain their conduct on such ground on appeal. The hearing did focus on the facts and circumstances of which the police were aware at the time of the alleged illegal seizure and therefore provided a rational basis upon which to apply the legal theory of justification by probable cause, despite the reliance of the police on the justification that there had been no seizure. Smith v. State (1971), 256 Ind. 603, 271 N.E.2d 133.

Appellant next contends that the trial prosecutor sought to improperly influence the jury's sentence recommendation by urging consideration of inflammatory and irrelevant matter. In the separate hearing at which the jury decides whether or not to recommend the death penalty to the judge, it is improper for the prosecutor to attempt to inflame the passions and prejudices of jurors on a false basis, or to minimize the role of the jury to the point of encouraging a neglect of duty, or to imply that the prosecution or the police have some inside or special knowledge which would support the imposition of the death penalty. Burris v. State (1984), Ind., 465 N.E.2d 171, cert. denied, 469 U.S. 1132, 105 S.Ct. 816, 83 L.Ed.2d 809 (1985). Under the federal Constitution, a sentence of death must be vacated where the trial prosecutor engages in misconduct before a sentencing jury which is so unfair and improper as to undermine the reliability of the sentencing decision. Caldwell v. Mississippi, 472 U.S. 320, 105 S.Ct. 2633, 86 L.Ed.2d 231 (1985); California v. Ramos, 463 U.S. 992, 103 S.Ct. 3446, 77 L.Ed.2d 1171 (1983). Indeed, whenever irrelevant and highly inflammatory material is injected at a sentencing hearing, an arbitrariness violative of the Eighth Amendment may result. Booth v. Maryland, 482 U.S. 496, 107 S.Ct. 2529, 96 L.Ed.2d 440, reh'g denied, 483 U.S. 1056, 108 S.Ct. 31, 97 L.Ed.2d 820 (1987).

Prosecution witness Furnish lived in the house with appellant and appellant's mother and other children. Furnish testified on direct that on the evening before the crime, appellant showed him a lockblade knife with a brown handle and that Furnish then told appellant that “if he did it, he was liable to get the electric chair,” and asked appellant “why don't [you] just wait a little, you know, for a couple of days for [your] tax return check to come in.” Appellant's part of this conversation was not provided, but on cross-examination the witness said there had been no talk about Juan Placencia.

In final summation to the jury at both the guilt and sentencing phases, the trial prosecutor urged the jury to draw the inference from Furnish's testimony that appellant intended to rob and kill Placencia as early as that evening. In this argument, the prosecutor outlined the source from the testimony upon which he urged the inference of intent be made. It was therefore an interpretation of the evidence, and as such it was within the confines of ethical and proper conduct. There was no claim of special or personal knowledge. Swope v. State (1975), 263 Ind. 148, 325 N.E.2d 193, cert. denied, 423 U.S. 870, 96 S.Ct. 135, 46 L.Ed.2d 100. There was no improper reference to the possible existence of other crimes or to any future risk to others if the defendant was not put to death. Tucker v. Francis, 723 F.2d 1504 (11th Cir.1984), cert. denied, 478 U.S. 1022, 106 S.Ct. 3340, 92 L.Ed.2d 743 (1986). This was no blatant attempt to stir up the passions and prejudice of the jury by referring to irrelevant considerations or sensational materials. See Drake v. Francis, 723 F.2d 1504 (11th Cir.1984), cert. denied, 478 U.S. 1020, 106 S.Ct. 3333, 92 L.Ed.2d 738 (1986). There was no attempt to minimize the jury's role in deciding whether to recommend the death penalty. Indeed, here the comment was the type which jurors can understand and deal with completely. It did not approach the improper and inflamatory character of the victim impact statement condemned in Booth v. Maryland, 482 U.S. 496, 107 S.Ct. 2529, 96 L.Ed.2d 440, reh'g denied, 483 U.S. 1056, 108 S.Ct. 31, 97 L.Ed.2d 820 (1987).

In final summation at the guilt phase of the trial, the trial prosecutor called for the jury to engage in the fight against crime and for justice and to strike a blow against evil and for the sanctity of the home. An argument of this sort, claiming that the jury owes it to the community to recommend the death penalty, amounts to misconduct. Bieghler v. State (1985), Ind., 481 N.E.2d 78, cert. denied, 475 U.S. 1031, 106 S.Ct. 1241, 89 L.Ed.2d 349 (1986). The danger of this type of argument is that it can be misunderstood by the jury as calling for the jury to convict the accused regardless of his guilt. Oricks v. State (1978), 268 Ind. 680, 377 N.E.2d 1376. Although this argument did pose such a danger, it was not such as to place appellant in a position of grave peril. Given the strength of the prosecution's evidence and the general nature of the patriotic remarks, the degree of impropriety and the probable persuasive effect on the jury's decision was no more than minimal.

The statements made by the trial prosecutor concerning the testimony of the witness Furnish and the duty of the jurors did not constitute cause for mistrial or undermine the reliability of the jury's death sentence recommendation contrary to the requirements of the Eighth Amendment.

The claim is next made that the death penalty is not appropriately applied in this instance. Appellant asserts that the aggravator alleged and found by the jury and court does not outweigh the overriding mitigating circumstances of his life history. Review by this Court of every death sentence is automatic and mandatory. The level of scrutiny is more intensive than for other criminal penalties, and the Rules for Appellate Review of Sentences apply as guides and not as limitations. Cooper v. State (1989), Ind., 540 N.E.2d 1216; Spranger v. State (1986), Ind., 498 N.E.2d 931, cert. denied, 481 U.S. 1033, 107 S.Ct. 1965, 95 L.Ed.2d 536 (1987).

The jury recommended that the death penalty be imposed. The judge declared in his sentencing order that the State proved beyond a reasonable doubt that appellant intentionally killed while robbing. The evidence manifestly proves this aggravating circumstance to a moral certainty beyond a reasonable doubt.

The judge also declared in his sentencing order that the State proved beyond a reasonable doubt that the several mitigating circumstances he found to exist were outweighed by the single aggravating circumstance. The mitigating circumstances found by the court were:

a. Appellant had no history of criminal activity as an adult, but this mitigator was lessened in weight by misconduct while a juvenile.

b. Appellant had a mental makeup which included diagnosed borderline personality disorders with aggressive behavior, tempered by a limited capacity to cope so as to do no harm to others.

c. Appellant was nineteen years of age. He lived as a child in an unstable environment. He lacked guidance, was mistreated, and did not have the social and learning skills to perform well in school. He was removed by court order from his home at fourteen and was kept in foster homes and institutions for four and a half years before rejoining his mother's household as an adult. This history was lessened in mitigating value by his failure to live up to household rules while living with others and by his proven ability to restrain his own aggression and hostility by taking walks.

On behalf of appellant, it is extensively argued that where a person's dangerous propensities are the product of his lack of care while growing up and not of his own conscious choices, such person is less deserving of the death penalty. Most would accept this proposition and the proposition that appellant's turbulent childhood is a significant mitigating circumstance. The trial judge did so, and we do likewise. The ultimate question for the judge and jury was, and for this Court now is, whether, upon the statutory assumption that the death penalty can be appropriate for homicide, the mitigating circumstances here, namely, the lack of prior criminal conduct, a turbulent childhood, and borderline personality disorders, are outweighed by the aggravating circumstance here, namely, the intentional stabbing and killing of Juan Placencia in the course of robbing him. This judgment need not be made to a moral certainty beyond a reasonable doubt. Moore v. State (1985), Ind., 479 N.E.2d 1264, cert. denied, 474 U.S. 1026, 106 S.Ct. 583, 88 L.Ed.2d 565. Upon review, we find that all mitigating circumstances were properly and accurately determined and evaluated and that they are outweighed by the lone aggravating circumstance, which was also properly and accurately determined and evaluated. The sentence is not arbitrary or capricious and is not manifestly unreasonable.

In instructing the jury at the penalty phase of trial, the court gave the following as Final Instruction No. 5: Neither sympathy nor prejudice for or against the victim or the defendant in this case should be allowed to influence you in whatever recommendation you may make. Appellant objected and was overruled, and the instruction was read. Appellant tendered his own instruction which would have authorized the jury to be governed by sympathy and sentiment in arriving at their recommendation on the sentence.

This instruction is to be judged upon the basis of whether it “excludes from consideration in fixing the ultimate punishment of death the possibility of compassionate or mitigating factors stemming from the diverse frailties of humankind.” Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280, 304, 96 S.Ct. 2978, 2991, 49 L.Ed.2d 944, 961 (1976). It must not impermissibly restrain the jury in its statutory and Eighth Amendment function of determining and evaluating mitigating circumstances and making an individualized assessment of the appropriateness of the death penalty. California v. Brown, 479 U.S. 538, 107 S.Ct. 837, 93 L.Ed.2d 934 (1987). There are two considerations which render this instruction correct. First, it operates well so as to restrain the use of responses based purely upon emotion, prejudice or bias to the detriment of the defendant. Second, its restraint upon the consideration by the jury of compassionate factors to the benefit of the defendant would be understood by the jury as applying only to the extreme reaches of the human inclination for sympathetic response in light of the specific call of other instructions to the jury to consider mitigating circumstances such as emotional disturbance, minor participatory conduct, and impairment by mental defect, all of which circumstances have compassionate elements. It was not error to give this instruction. It was balanced and did not undermine the reliability of the jury's recommendation. It is also to be noted that this instruction was given to a jury which does not sentence but only recommends and that the trial judge's findings reflect a full appreciation of the impact of appellant's misfortune as a child upon his moral blameworthiness.

Appellant claims next that the trial court erred in denying several challenges to the manner and time of filing amended charges of murder and robbery and an amended request for the death sentence. The amended charges and death request upon which appellant was ultimately tried reached their final and quiescent state six months before the commencement of the trial. Both the original and amended requests for the death sentence were based upon the intentional killing during the course of a robbery, pursuant to I.C. 35-50-2-9(b)(1), and were essentially the same. Both the two original and the two amended substantive counts were for the murder and robbery of the victim, Placencia. The original murder charge claimed a felony murder, charging that Placencia had been killed during a robbery, whereas the amended murder charge alleged outright intentional murder. The original robbery charge claimed a repeated stabbing of Placencia, whereas the amended robbery charge alleged a repeated stabbing resulting in serious bodily injury. Under these circumstances, and to the extent that the filing of these amended pleadings was achieved without an initial hearing in conjunction with it, written notice to the defendant, court permission, or other requirements of the governing statute, I.C. 35-34-1-5, there is no likelihood that substantial rights were prejudiced in light of the similarity of the pleadings and the ample opportunity of the defense to reckon with them. To the extent that there is a purpose behind the governing procedures to protect the due process interests of the defendant, that purpose was satisfied despite any irregularity in the process.

Appellant also claims that the amended criminal charges were filed in the DeKalb Superior Court after the court granted a change of venue from the county. The record supports this claim; however, the record also discloses that the filing occurred during the period of time granted by the court for opposing counsel to agree upon a new county and before preparation of the transcript for dispatch. The general rule is that a court is divested of jurisdiction after granting a change of venue. 29 I.L.E. Venue § 18 (1960). Here the filing did not entail any exercise of jurisdiction by the DeKalb Superior Court. There is no authority to which our attention is directed declaring a filing of this sort a nullity.

Appellant also claims that a written death penalty request must be refiled each time the underlying murder charge is amended. Here, the existing amended death penalty request was not refiled with or after the filing of the amended murder and robbery counts. The death statute requires only that a page kept separate from the balance of the charging instrument allege at least one of the aggravating circumstances. There is no authority for a requirement such as appellant proposes, and we can envisage no legitimate interest of the appellant to be served by such a requirement.

It is next claimed on appeal that the court erred in refusing to give eight penalty phase final instructions tendered by the defense. The first is a quotation of Article I, § 18 of the Indiana Constitution. The others cover the subjects of the use by the jurors of their own experiences and their beliefs concerning the death penalty, the requirement that the recommendation must be based upon a conviction that aggravators outweigh mitigators, the prosecution's burden of proof, the restriction of the consideration to the lone aggravator, the definition of mitigating circumstances and addition of a list of facts which, if found to exist, would be proper mitigators, the discretion of the jury in determining and evaluating mitigating circumstances, and the use of sentiment and sympathy for appellant.

In considering whether any error results from the refusal of a tendered instruction, we must determine: (1) whether the instruction correctly states the law, (2) whether there is evidence in the record to support the giving of the instruction, and (3) whether the substance of the instruction is covered by other instructions which are given. Davis v. State (1976), 265 Ind. 476, 355 N.E.2d 836.

Article I, § 18 provides: The penal code shall be founded on principles of reformation, and not of vindictive justice. This Court held in Adams v. State (1971), 259 Ind. 64, 271 N.E.2d 425, by a vote of three to two, that the death penalty for murder was not violative of this provision. In Emory v. State (1981), Ind., 420 N.E.2d 883, the Court held that this provision did not foreclose a criminal system based on punishment. It does instead “reveal an underlying concern ... that, notwithstanding society's valid concerns with protecting itself and providing retribution for serious crimes, the State criminal justice system must afford an opportunity for rehabilitation where reasonably possible.” Fointno v. State (1986), Ind., 487 N.E.2d 140, 144. In Denson v. State (1975), 263 Ind. 315, 330 N.E.2d 734, this Court held that it was not error to refuse this instruction, despite the fact that it was a correct statement of law, since the provision seems to be addressed to lawmaking bodies and would likely mislead or confuse a jury. That rationale would apply with greater force in the penalty phase of a capital case than it would in the guilt phase since the jury is being called upon to decide the propriety of a sentence which forecloses all possibility of reforming the defendant. There was no error in refusing the tendered instruction quoting this provision.

Appellant's tendered instruction on the use of sentiment and sympathy provided as follows: A decision to grant David Leon Woods mercy does not violate the law. The law does not forbid you from being influenced by pity for David Leon Woods and you may be governed by mere sentiment and sympathy for David Leon Woods in arriving at a proper penalty in this case.

You need not find the existence of any mitigating fact or circumstance in order to return a recommendation against death. This instruction was an incorrect statement of the law. It is contrary to the statute which requires the recommendation of death to be based upon the relative weight of aggravating circumstances and mitigating circumstances. I.C. 35-50-2-9(e)(2).

The substance of the remaining penalty phase instructions rejected by the trial court was adequately covered by the court's Instruction No. 10, which defined reasonable doubt, and by the court's Instructions Nos. 8 and 11, which tracked the statutes and pleadings and enumerated the statutory categories of mitigating circumstances, including the final general category of “any other circumstances appropriate for consideration.” I.C. 35-50-2-9(c)(8).

In its order changing the venue of this case from the DeKalb Superior Court to the Boone Superior Court, the judge included the following in his order:

The Court now has a telephone conference with The Hon. Paul H. Johnston [sic], Jr. of the Boone Superior Court, and ... he accepts the said request. The Court finds that the Prosecuting Attorney and Defendant have stipulated that the Hon. Paul H. Johnston [sic], Jr. shall remain as Judge and will agree upon him as Special Judge for any proceedings which might take place after January 1, 1985 in the event that the Hon. Paul H. Johnston [sic], Jr. would not be reelected to the Boone Superior Court.

Judge Johnson assumed jurisdiction on change of venue, but was not reelected. His successor, Judge Peyton, assumed jurisdiction over the case over appellant's objection. An interlocutory appeal was sought but did not result in a ruling on this matter.

The general rule is that the jurisdiction over cases filed in any given court, or coming into any given court from another county on a change of venue, is in that court. I.C. 35-36-6-2; Ind.R.Tr.P. 78. It is also a general rule that when a judicial office is vacated and a new judge assumes the office, such new judge assumes jurisdiction over all matters that were pending in the court before the former judge sitting as the regular judge. Cf. Ind.R.Tr.P. 79(15). Here, Judge Johnson had jurisdiction over this pending case as the regular judge of the Boone Superior court. Since he was serving over this case as regular judge when he vacated the office, no occasion arose for the selection and appointment of a special judge pursuant to the stipulation of the parties. Judge Peyton had jurisdiction over this case from the moment he took office and was correct in retaining it despite the order of the DeKalb Superior Court.