59th murderer executed in U.S. in 2005

1003rd murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

2nd murderer executed in California in 2005

12th murderer executed in California since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

| |

Stanley "Tookie" Williams B / M / 25 - 51 |

Albert Lewis Owens W / M / 26 Tsai-Shai Yang A / M / 76 Yen-I Yang A / F / 63 Ye Chen Lin A / F / 43 |

03-11-79 03-11-79 03-11-79 |

Shotgun Shotgun Shotgun |

None None None |

Summary:

In the early morning hours of February 28, 1979, Williams and three friends were riding around in two cars, smoking PCP-laced cigarettes, looking to "make some money." After making two unsuccessful restaurant and liquor store robbery attempts, they eventually went to a 7-Eleven store where 26 year old Army veteran and father of two, Albert Lewis Owens, was working the overnight shift and sweeping the parking lot. Armed with a shotgun, Williams led Owens to the back room of the store. While one of the companions emptied the cash register drawer and took $120, the defendant ordererd Owens to get on his knees and then shot him twice in the back with the shotgun. Williams said later that he did so to eliminate witnesses. One of his accomplices testified at trial that Williams later made fun of the noises made by Owens when he was shot, causing Williams to laugh hysterically.

Eleven days later, at about 5:30 a.m., Williams and another man broke down the door and entered the Brookhaven Motel at 10411 South Vermont Avenue in Los Angeles and shot to death 76-year old Thsai Shai Young, his 63-year old wife Yen-I Yang and their 43-year old daughter Ye Chen Lin. He took $50 in cash and left.

Williams and Raymond Washington co-founded the Crips, a street gang, in 1971. While incarcerated on Death Row, Williams gained notoriety by authoring children's books with an anti-gang message and promoting peace. In recent years, he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature and for Peace. He gained unparalelled support from celebrities and anti-death penalty activists, including Mike Farrell, Jesse Jackson, Jamie Foxx, and others who argued that his work and redemption on death row merited a reprieve from execution.

Citations:

In re Williams, 7 Cal.4th 572, 29 Cal.Rptr.2d 64 (Cal. 1994) (State Habeas).

People v. Williams, 44 Cal.3d 1127, 245 Cal.Rptr. 635 (Cal. 1988) (Direct Appeal).

Williams v. Woodford, 384 F.3d 567 (9th Cir. 2004) (Habeas).

Final Meal:

None.

Final Words:

None.

Internet Sources:

California Department of Corrections

Inmate: Williams, Stanley (CDC #C29300 )

Alias: Tookie

Race: Black

Date Received: April 20, 1981

Education: 12th Grade

Location: San Quentin

Marital Status: Single

County of Trial: Los Angeles

Offense Date: March 11, 1979

Sentence: Four counts of first-degree murder with special circumstances.

Date of Sentence: April 20, 1981

Case #: A194636

Children: Stanley Williams Jr. (Serving a 16-year sentence at High Desert State Prison for second-degree murder)

"DEATH WATCH AT SAN QUENTIN - Tookie Williams Is Executed; The killer of four and Crips co-founder is given a lethal injection after Schwarzenegger denies clemency. He never admitted his guilt," by Jenifer Warren and Maura Dolan. (2:18 AM PST, December 13, 2005)

Stanley Tookie Williams, whose self-described evolution from gang thug to antiviolence crusader won him an international following and nominations for a Nobel Peace Prize, was executed by lethal injection early today, hours after Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger refused to spare his life. His death was announced at 12:35 a.m.

During the execution, the inmate’s friend Barbara Becnel and other supporters mouthed "God bless you" and "We love you" and blew kisses to Williams. Williams also seemed to mouth statements to Becnel. The entire procedure took longer than usual. The execution team took about 12 minutes to find a vein in Williams’ muscular left arm. While the personnel were probing, Williams repeatedly lifted his head off the gurney, winced visibly, and at one point appeared to say: "Still can’t find it?" After Williams was pronounced dead, Becnel and two other supporters of Williams turned toward the media in the witness room and yelled in unison, "The state of California just killed an innocent man!" Lora Owens, murder victim Albert Owens’ stepmother, appeared shaken, and was embraced by another woman.

Outside the gates of San Quentin as midnight approached, speakers urged calm. There was a moment of tension when a Williams’ friend, Fred Jackson, told the crowd, "It’s all over." Angry shouts broke out. A woman sobbed on someone’s shoulder, and a man burned an American flag. As Jackson continued to urge calm, the crowd dispersed. Speaking outside the gates of San Quentin after the execution, Becnel, who is taking possession of Williams’ body, called Schwarzenegger a "cold-blooded murderer" and vowed to work for his defeat in the next election.

Despite persistent pleas for mercy from around the globe, the governor earlier in the day had said Williams was unworthy of clemency because he had not admitted his brutal shotgun murders of four people during two robberies 26 years ago. After the U.S. Supreme Court denied a request for a last-minute stay Monday evening, the co-founder of the infamous Crips street gang — who insisted he was innocent of the murders — became the 12th man executed by the state of California since voters reinstated capital punishment in 1978.

With its racial overtones and compelling theme — society’s dueling goals of redemption and retribution — the case provoked more controversy than any California execution in a generation, and became a magnet for attention and media worldwide. A long list of prominent supporters — as disparate as South African Bishop Desmond Tutu and rapper Snoop Dogg — rallied to Williams’ cause.

But in a strongly worded rejection of Williams’ request for clemency, Schwarzenegger said he saw no need to rehash or second-guess the many court decisions already rendered in the case, and he questioned the death row inmate’s claims of atonement. Williams, the governor said in a statement, never admitted guilt, plotted to kill law enforcement officers after his capture, and made little mention in his writings of the scourge of gang killings, which the statement called "a tragedy of our modern culture."

As night descended Monday, about 1,000 demonstrators who gathered on a tree-lined street leading to the gates of San Quentin State Prison endured frosty temperatures to protest the execution. Joan Baez sang "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot" as speakers urged participants to keep fighting. Small clumps of people in scarves and gloves held candles and sang hymns, while others wandered off alone, gazing into the bay. There were small, scattered protests around the state, including a candlelight vigil Monday night in Leimert Park.

A few death penalty supporters also turned out at San Quentin. Scuffles and shoving matches broke out on occasion, but no serious incidents were reported.

Behind the prison’s thick walls, Williams passed his dwindling hours quietly, visiting with friends and talking on the telephone while under constant watch by guards. An acquaintance described him sitting at a table, handcuffed, next to untouched turkey sandwiches, bidding goodbye to friends in an ordinary, everyday manner. A prison spokesman said Williams was calm and upbeat, though he ate nothing but oatmeal and milk all day, refusing the privilege of a special last meal. Williams also declined a spiritual advisor.

The Rev. Jesse Jackson said he met twice with Williams, and together with Becnel delivered the news that the governor had denied clemency. Williams smiled "as if he expected it," Jackson said. He said Williams again denied his guilt, and said that he thought "his baggage as a Crip was on trial more than for the four murders."

In recent statements, Williams had expressed a philosophical attitude about his own death. Fred Jackson, 67, who works with Internet Project for Street Peace, Williams’ gang intervention project, said the inmate struck that tone in a phone conference with an Oakland support group Sunday. "He said he doesn’t fear death — he doesn’t fear what he does not know," Jackson said.

At 6 p.m., Williams was strip-searched, given a set of clean clothes and placed in a holding cell steps from the death chamber under nonstop observation by a sergeant and two officers. Officials said he spent the evening watching TV and reading some of the roughly 50 letters that arrived Monday from as far as Italy and Israel — including some from schoolchildren. Many of them said they were praying for him. Nearby, the injection team began its final preparations in the prison’s converted gas chamber, ensuring that the required needles, tubes and chemicals were in place.

Williams’ son, Stanley Williams Jr., who is in High Desert State Prison serving a 16-year sentence for second-degree murder, will be notified in person of his father’s death by a chaplain and mental health specialist, prison officials said. The younger Williams is in isolation for disciplinary problems, and would not normally have access to any news source.

Five members of the murder victims’ families were at the prison, although it was not clear how many witnessed the execution. Williams, who earlier said he didn’t want to invite anyone to observe "the sick and perverted spectacle," had five witnesses, including Becnel and members of his legal team. Officials designated a total of 39 witnesses, including 17 media representatives.

Lora Owens said she did not expect the execution to end the ache over losing her red-haired stepson, Albert, who was killed with a shotgun at the age of 26 while working at a Pico Rivera 7-Eleven late one February night in 1979. But watching the killer take his last breath, she said, might help her "let it go" just a bit.

Advocates for clemency had argued that Williams had unmatched credibility as a messenger urging youths to say no to gangs. But law enforcement officials and victims’ rights leaders portrayed Williams as a fraud whose influence on would-be gangsters was overblown.

Prosecutors said the absence of a confession, and Williams’ refusal to formally cut ties with the Crips by sharing his knowledge of gang tactics with police, disproved his claim of rehabilitation. "What kind of message does that send to young children, when somebody like Mr. Williams, who supposedly has their attention, tells them, ‘Don’t snitch, don’t talk to police, don’t tell people who was involved in a crime?’." said John Monaghan, a Los Angeles County deputy district attorney.

As Schwarzenegger weighed his decision, attorneys for Williams spent the weekend hunting for a court that might issue a stay. On Sunday, the state Supreme Court turned back arguments that his trial was "fundamentally unfair" in part because prosecutors had failed to disclose that a key witness, Alfred Coward, was a violent ex-felon. The U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals and finally the U.S. Supreme Court followed suit Monday.

After the governor rejected clemency, lawyers asked Schwarzenegger for a stay on the basis of three witnesses who they said had come forward just this week with exculpatory information. But Schwarzenegger again delivered a rebuff. Just before 9:30 p.m., Williams lawyers filed another petition, citing a fourth purported witness who claimed other inmates tried to recruit him into a scheme to frame Williams. The governor denied that, too.

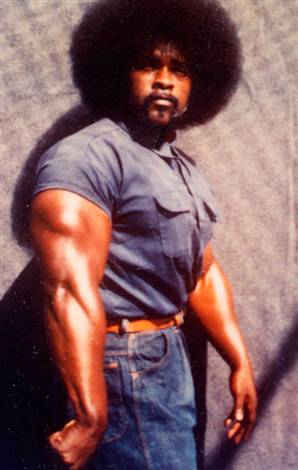

Born in New Orleans, Stanley Tookie Williams III was named for his father but raised by his mother. Hoping to escape poverty and crime in Louisiana, the family moved to South Los Angeles in 1959. He spent his youth as a delinquent, rebounding in and out of Central Juvenile Hall. In his writings, he admitted that he was a megalomaniac who beat, robbed and shot at the innocent. By the 1970s, Williams was viewed as one of the more menacing toughs in South Los Angeles, weighing 300 pounds with biceps measuring 22 inches. In a move he said he regretted more than any other, he helped launch the Crips — originally called the Cribs — and began terrorizing the streets.

On Feb. 27, 1979, he and three cohorts smoked cigarettes laced with PCP and, armed with a 12-gauge shotgun and a .22-caliber handgun, set out on a late-night search for a place to rob, according to court documents. They wound up at the 7-Eleven where Owens, a father of two and Army veteran, was working the overnight shift. Owens was shot twice in the back.

Less than two weeks later, Williams broke down the door at the Brookhaven Motel and killed the motel’s owners, Taiwanese immigrants Yen-I Yang, his wife, Tsai-Shai Chen Yang, and their daughter, Yu Chin Yang Lin, who was visiting. The two robberies netted $220.

In 1981, a jury in Torrance convicted Williams, landing him on death row. Initially his conduct was disruptive: "I gave this place hell," he acknowledged in an interview. While in solitary confinement, however, he began a transformation, Williams said. At first he read voraciously — the Bible, the dictionary, philosophy, black history — and struggled to understand his past.

By 1992, Williams was a changed man, he said, deeply remorseful for the bloody rampage the Crips had perpetrated across America — and for the gang life that lured in one of his two sons. In 1994, Williams left solitary confinement and declared himself a champion of peace.

With the help of Becnel, he wrote a series of books warning youths away from violence and brokered gang truces in Los Angeles and New Jersey. Last year, his life became the subject of a TV movie, "Redemption," starring Jamie Foxx, and his imposing appearance gradually gave way to a graying beard and spectacles. Reached by phone at her Los Angeles home as the execution was underway, Williams’ ex-wife, Bonnie Williams Taylor, said, "This is an awful time. I want to be with my family."

Earlier in the evening, dozens of people had gathered in Leimert Park in Los Angeles to oppose the execution. But the speakers who addressed them focused more on healing crime in black communities than on Williams’ plight. "We have to understand," said African American activist Eric Wattree, 53, speaking to a mostly black crowd early in the evening, "this is our failure taking place here."

Times staff writers Dan Morain and Steve Chawkins in San Quentin and Jill Leovy, Lisa Richardson, Greg Krikorian, Louis Sahagun and Carla Hall in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

"Warden: Williams frustrated at end; Crips gang co-founder put to death for 4 murders" (Dec 13, 2005)

SAN QUENTIN, California (CNN) -- Death did not come quickly for Stanley Tookie Williams, the co-founder of the violent Crips street gang who was executed by lethal injection early Tuesday for the 1979 robbery murders of four people in Los Angeles.

Witnesses and prison officials said Williams appeared to grow impatient as prison staffers searched for several minutes for a vein in his muscular left arm. Authorities began the process to administer the lethal injection at 12:01 a.m. (3:01 a.m. ET) in the execution chamber at San Quentin. His death was announced 34 minutes later. (Watch a bulletin of Williams' death -- :40) "He did seem frustrated that it didn't go as quickly as he thought it might," said San Quentin State Prison Warden Steven Ornoski.

Williams, 51, acknowledged a violent past but maintained he was innocent of the slayings. He became an anti-gang crusader while on death row. It was the second execution in California this year, and the 12th since the death penalty was reinstated in the 1970s. "He had a just punishment," said Lora Owens, stepmother of one of Williams' victims and a witness to the execution. "Now I just want to get on," she told CNN on Tuesday. (Watch victim's stepmother talk about execution -- 3:54)

Williams' case set off intense debate over capital punishment and redemption, with celebrities, activists and anti-death penalty advocates saying his initiatives and anti-gang message from behind bars meant his life was worth saving. Williams had been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize and the Nobel Prize in Literature by an array of college professors, a Swiss lawmaker and others.

Difficulty inserting needle

Seventeen reporters witnessed the execution and gave their accounts afterward. (Watch the witnesses describe Williams' last minutes -- 10:04)

They said inserting the IVs to administer the lethal chemicals took nearly 20 minutes, with staff having particular difficulty getting a needle into Williams' left arm. Witness Crystal Carreon of the Sacramento Bee said Williams was restless during the preparations. Another witness, Kim Curtis, a reporter for The Associated Press, said Williams appeared to say, "You doing that right?" as prison staffers searched for a vein. Los Angeles Times columnist Steve Lopez said Williams offered "no resistance," but raised his head several times and looked toward his supporters and the press gallery.

Some witnesses said Williams appeared to wince when the needle found its mark. Three of Williams' invited supporters shouted in unison, "The state of California just killed an innocent man," as they exited the gallery after his death. Minutes earlier, reporters said, at least one of the three had given Williams a raised fist salute.

Clemency, appeals denied

The execution went ahead as scheduled after the U.S. Supreme Court late Monday rejected a last-ditch appeal.

The high court's ruling followed California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger's decision to deny clemency for Williams.

"Based on the cumulative weight of the evidence, there is no reason to second-guess the jury's decision of guilt or raise significant doubts or serious reservations about Williams' convictions and death sentence," Schwarzenegger said in a five-page statement explaining his decision.

Before Williams went to the execution chamber, Owens said she felt "justice is going to be done tonight." "I had faith that when Governor Arnold (Schwarzenegger) looked at the facts of the case that he was going to decide not to do clemency," said Owens, whose stepson, Albert Owens, was shot to death in a convenience store holdup. "I don't like it being said it's a political decision," she added. "It was an evidence decision."

Williams had maintained his innocence since his arrest and conviction in the 1979 slayings. He denounced gang violence and wrote children's books with an anti-gang message, donating the proceeds to anti-gang community groups. One of his lawyers, Peter Fleming, called the governor's decision to deny clemency "wrongheaded." (Watch the lawyer's reaction -- 5:00) As Williams was being moved to a holding cell next to the death chamber Monday evening, his lead attorney, John Harris, had said the convict was "at peace."

Protesters outside the gates

A crowd of demonstrators gathered outside the gates of the prison Monday evening, with celebrities, activists and anti-death-penalty advocates pleading for Williams' life to be spared. (Watch the San Quentin protest -- 1:38)

"I am saddened that we are continuing to demean human life by pretending that we are God and making determinations to kill other individuals for what it is claimed they have done," former "M*A*S*H" star and death penalty opponent Mike Farrell told CNN.

Civil rights leader Jesse Jackson, who visited with Williams, said Schwarzenegger decided "to choose revenge over redemption and to use Tookie Williams as a trophy in the flawed system." "To kill him is a way of making politicians look tough," Jackson said. "It does not make it right. It does not make any of us safer. It does not make any of us more secure."

Sister Helen Prejean, a Roman Catholic nun and prominent death penalty opponent, compared the death penalty to "gang justice." "Gang justice is, if you kill a member of our gang, we kill you -- and don't tell me anything about how you changed your life or what you're going to do," she said. "You kill, and we kill you. And that's what the United States of America is doing with this."

But Schwarzenegger questioned the sincerity of Williams' conversion to nonviolence. "Is Williams' redemption complete and sincere, or is it just a hollow promise?" Schwarzenegger wrote. "Without an apology and atonement for these senseless and brutal killings there can be no redemption." He added: "In this case, the one thing that would be the clearest indication of complete remorse and full redemption is the one thing Williams will not do."

Barbara Becnel, the editor of Williams' books, pledged that his supporters would not give up their fight to prove Williams' innocence. "We are going to prove his innocence, and when we do, we are going to show that Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger is, in fact, himself a cold blooded murderer," Becnel said.

Prosecutor: Evidence 'rock solid'

Williams was sentenced to death in 1981 in the killing of Owens, a 26-year-old Los Angeles convenience store clerk. The clerk was shot twice in the back with a 12-gauge shotgun while face-down on the floor.

Less than two weeks after Owens' February 1979 slaying, jurors concluded, Williams killed an immigrant Chinese couple and their 41-year-old daughter while stealing less than $100 in cash from their motel. Robert Martin, one of the prosecutors who sent Williams to prison, said the courts "have scrutinized this from every angle and they've found that the evidence is rock solid."

He questioned whether there was any moral equivalence "between co-authoring some children's books and the senseless murder of four people in cold blood." "The books will live on," Martin told CNN. "We have many authors who have died, and their books are still in print. And if they have any good effect, that can continue. So I don't believe that that is a conclusive argument."

CNN's Ted Rowlands, Kareen Wynter and Bill Mears contributed to this report.

"WILLIAMS EXECUTED; Gang co-founder put to death for 1979 murders of 4 in L.A. area," by Stacy Finz, Peter Fimrite, Kevin Fagan. (Tuesday, December 13, 2005)

Stanley Tookie Williams, a gangster who became an anti-gang crusader in prison and the focus of a furious clash between advocates of punishment and redemption, was executed by lethal injection early today for four 1979 Los Angeles-area murders that he denied committing.

Williams, 51, was pronounced dead at 12:35 a.m. at San Quentin State Prison, where he had spent nearly half his life. His execution had been all but assured Monday when Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger denied clemency, saying, "The facts do not justify overturning the jury's verdict or the decisions of the courts in this case."

Williams offered no resistance as he was strapped to the gurney in the death chamber but appeared exasperated as prison officials hooked him up to the intravenous tubes that injected the poison, according to reporters who witnessed the execution. One reporter said it took 36 minutes from when Williams was brought into the chamber for him to be pronounced dead. At one point, Williams looked around and appeared to ask, "You doing that right?" said Kim Curtis of the Associated Press.

A total of 39 people watched Williams die, including a few he invited to be witnesses. Three of them raised their fists in salute as Williams looked at them and afterward yelled, "The state of California just killed an innocent man," said Chronicle reporter Kevin Fagan. Lora Owens, stepmother of one of Williams' murder victims, burst into tears at the outburst.

Williams spent his last hours in a 45-square-foot "death watch" cell, where he was given a new set of clothes -- jeans and a blue work shirt -- to change into before being escorted to the death chamber. While in the cell, Williams spoke by phone with his attorneys as the governor and courts rejected last-minute requests for a stay. He also had access to a television set, but wasn't watching, said Terry Thornton, a spokeswoman for the state Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

Outside the prison gates, about 2,000 death-penalty protesters prayed for a last-minute reprieve, while a few motorists shouted from their car windows, "Kill him." Inside, Williams remained composed, forgoing his final meal and opting only for a couple of small cartons of milk. "He has been very calm, very quiet and very respectful of the staff," said Todd Slosek, another spokesman for the prison.

Williams' morning started with a bowl of oatmeal, and during the day he met with his lawyers and six visitors, including the Rev. Jesse Jackson, who had publicly spoken out for him. The condemned man had his visitors brought into his cell one at a time and gave them "his formal goodbyes," Thornton said. "And after that, he gathered them all as a group and addressed them all. "Some of them looked close to tears and some of them looked angry," Thornton said, relaying what guards had said of the witnesses.

A prison chaplain was available to Williams if he had requested spiritual counsel, but he did not, Thornton said. He also did not request a sedative before the execution, though one was available, she said. Williams did, however, ask that five witnesses be present at his execution. Earlier he had said he didn't want anyone he knew to see him die, but apparently he had a change of heart.

Williams is the 12th person put to death in California since the state resumed executions in 1992 after a 25-year suspension because of court rulings. No capital case in the state had stirred such national and international attention since Caryl Chessman -- like Williams, an author of books from Death Row -- was executed in the gas chamber in 1960 for rape and kidnapping.

To his supporters, Williams was a man who had turned his life around in prison, writing eight children's books denouncing gang life. Last week Williams was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize for the sixth straight year, by a philosophy professor at Notre Dame de Namur University in Belmont who opposes the death penalty. Williams' books for children and young people have also been nominated four times for the Nobel Prize for literature.

But to others Williams was an archvillain who co-founded the violent Crips street gang and unleashed a crime wave that changed Southern California.

His lawyers tried frantically until the end to find a way to save him. Just two hours before Tuesday's execution, they pleaded with Schwarzenegger for a 60-day stay, arguing that in the 11th hour a witness had surfaced who could shed new light on the case. Earlier in the day, they said three jailhouse witnesses had come forward this week with evidence that could show Williams had been framed for the four shotgun murders that put him on Death Row.

But the governor, the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco and the U.S. Supreme Court rejected all the defense efforts to spare Williams' life. "Clemency cases are always difficult, and this one is no exception," Schwarzenegger wrote in a six-page statement rejecting Williams' bid to have his sentence commuted to life without the possibility of parole. "After studying the evidence, searching the history, listening to the arguments and wrestling with the profound consequences, I could find no justification for granting clemency. The facts do not justify overturning the jury's verdict or the decisions of the courts in this case."

Williams said he was a changed man and of value to society because of his anti-gang writings from behind bars. Schwarzenegger noted, however, that Williams had never apologized for the murders. Williams maintained he did not commit them. "Without an apology and atonement for these senseless and brutal killings, there can be no redemption," Schwarzenegger said. "In this case, the one thing that would be the clearest indication of complete remorse and full redemption is the one thing Williams will not do.''

A native of New Orleans who grew up in South Central Los Angeles, Williams started the Crips gang with a friend in 1971, when he was 16. According to state prison files, he had juvenile convictions for drugs and auto theft in 1970, was sent to a youth detention camp, quit high school in 1971 and later spent two years in junior college. At the time of the murders in 1979, he had no adult felony convictions.

The first victim, Albert Owens, 26, a clerk at a 7-Eleven store in Whittier, was ordered to lie on the floor and then was shot in the back during a $120 robbery on Feb. 28, 1979. One of the robbers, Alfred Coward, granted immunity from prosecution, testified that Williams had fired the fatal shots and laughed about it afterward. Williams reportedly told friends, "You should have heard the way he sounded when I shot him."

On March 11, 1979, Yen-I Yang, 76, and Tsai-Shai Yang, 63, owners of the Brookhaven Motel in Los Angeles, and their daughter, Yee-Chen Lin, 43, were shot to death during a $100 robbery. A sheriff's expert testified that a shell casing found at the scene matched Williams' shotgun. Other prosecution witnesses said Williams had admitted committing both crimes, and that he had referred to the motel victims as "Buddha-heads."

Williams, convicted and sentenced to death in 1981, maintained that he was railroaded by witnesses who lied in exchange for leniency in their own criminal cases, by a faulty ballistics test, and by a prosecutor who removed three African Americans from the jury and told jurors that seeing Williams in court was like observing a Bengal tiger in a zoo.

State and federal courts rejected each of his appeals, although federal judges described the evidence as less than airtight, and a three-judge federal panel said he might be a worthy candidate for clemency.

Williams, who was seen mouthing a threat to the jury after the guilty verdict, remained a violent man during his early years in prison, assaulting inmates and guards and spending six years in solitary confinement, from 1988 to 1994. But as he later described it, during that period he began reading widely and reflecting on his life, and resolved to prevent gang violence.

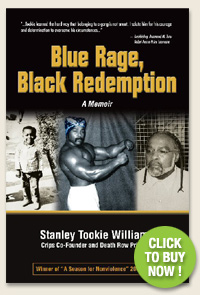

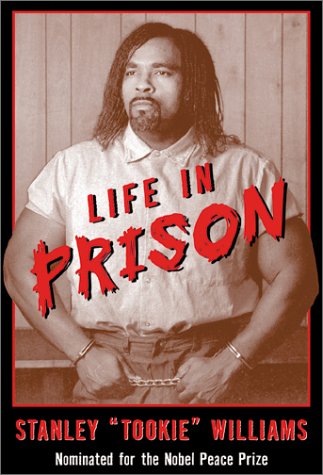

Williams taped a message from prison in April 1993 that was broadcast to Los Angeles gang members at a "peace summit.'' With the help of Barbara Becnel, a writer he met in prison who became his champion, he started work on eight books for children that were published in 1996 as a series called, "Tookie Speaks Out Against Gang Violence.'' He followed with "Life in Prison'' in 1998 and a memoir, "Blue Rage, Black Redemption,'' in 2004 and was working on two more books before his execution. He spoke regularly from prison to youths and educators, and posted a model "peace protocol'' for gangs, which supporters say was widely used, on his Web site in 2000. "Redemption,'' a television movie starting Jamie Foxx in a sympathetic portrayal of Williams, aired in 2004.

Assertions by Williams' supporters of success for his peacemaking efforts drew skepticism from some researchers, who found no decline in killings after gang peace summits. But individual testimonials abounded from youths who said Williams changed their lives.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"The only people who would have been happy with clemency were people who likely wouldn't support him anyway.'' -- Dan Schnur, a political consultant

Stanley Tookie Williams "feels any acts of violence would undermine his legacy of anti-violence. He wants to be remembered with dignity, as a social transformer." -- The Rev. Jesse Jackson

"This is less about Tookie and more about the criminal justice system. We spend so much energy on young men of color, while corporate criminals who ruin millions of lives go unchallenged." -- The Rev. Christopher Craethnenn, marching with anti-death penalty demonstrators

"Who's going to stop the killings now? Is (the governor) going to write some books? Is he going to go down to L.A. and get some help and hope to the kids in the Crips?" -- James Richards, San Francisco, a member of a group that works with young men in the Bayview neighborhood

"The ones who went from predators to peacemakers, they are the only guys who can talk to these kids and make them listen." -- Constance Rice, a civil rights lawyer and death penalty opponent

The governor "clearly focused on the main issue: Is this person guilty? Beyond that, the other issues seemed to be academic.'' -- Michael Rushford of the pro-death penalty Criminal Justice Legal Foundation, on Schwarzenegger's refusal of clemency

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Executions in California

Since the death penalty was reinstated in California in 1977, there have been 11 previous executions. Harris and Mason were put to death by gas chamber, the others by lethal injection.

NAME: Robert Alton Harris

DATE: April 21, 1992

AGE: 39

NUMBER OF VICTIMS: 2

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

NAME: David Edwin Mason

DATE: Aug. 24, 1993

AGE: 36

NUMBER OF VICTIMS: 5

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

NAME: William George Bonin

DATE: Feb. 23, 1996

AGE: 49

NUMBER OF VICTIMS: 4

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

NAME: Keith Daniel Williams

DATE: May 3, 1996

AGE: 48

NUMBER OF VICTIMS: 3

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

NAME: Thomas M. Thompson

DATE: July 14, 1998

AGE: 43

NUMBER OF VICTIMS: 1

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

NAME: Jaturun Siripongs

DATE: Feb. 9, 1999

AGE: 43

NUMBER OF VICTIMS: 2

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

NAME: Manuel Babbitt

DATE: May 4, 1999

AGE: 50

NUMBER OF VICTIMS: 1

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

NAME: Darrell Keith Rich

DATE: March 15, 2000

AGE: 45

NUMBER OF VICTIMS: 1

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

NAME: Robert Lee Massie

DATE: March 27, 2001

AGE: 59

NUMBER OF VICTIMS: 1

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

NAME: Stephen Wayne Anderson

DATE: Jan. 29, 2002

AGE: 48

NUMBER OF VICTIMS: 1

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

NAME: Donald Beardslee

DATE: Jan. 19, 2005

AGE: 61

NUMBER OF VICTIMS: 2

Sources: California Department of Corrections; Death Penalty Information Center

"Pope, many Europeans express outrage over execution of 'Tookie' Williams." (11:23:13 EST Dec 13, 2005)

VIENNA, Austria (AP) - The execution of convicted murderer Stanley (Tookie) Williams in California on Tuesday outraged many in Europe, who regard the practice as barbaric, and feelings ran particularly high in Austria, the homeland of Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger.

At the Vatican, Pope Benedict's top official for justice matters denounced the death penalty for going against redemption and human dignity. "We know the death penalty doesn't resolve anything," Renato Cardinal Martino told Associated Press Television News. "Even a criminal is worthy of respect because he is a human being. The death penalty is a negation of human dignity."

Capital punishment is illegal throughout the European Union, and many Europeans consider state-sponsored executions to be barbaric. Those feelings were amplified in the case of Williams, due to the apparent remorse they believe the Crips gang co-founder showed by writing children's books about the dangers of gangs and violence.

Leaders of Austria's pacifist Green party went as far as to call for Schwarzenegger to be stripped of his Austrian citizenship - a demand that was rejected by Chancellor Wolfgang Schuessel. "Whoever, out of political calculation, allows the death of a person rehabilitated in such an exemplary manner has rejected the basic values of Austrian society," said Peter Pilz, a Greens leader.

In Graz, Schwarzenegger's hometown, local Greens said they would file a petition to remove the governor's name from the southern city's Arnold Schwarzenegger Stadium. A Christian political group went even further, suggesting it be renamed the "Stanley Tookie Williams Stadium." "Mr. Williams had converted and, unlike Mr. Schwarzenegger, opposed every form of violence," said Richard Schadauer, the chairman of the Association of Christianity and Social Democracy.

Williams was executed Tuesday morning at California's San Quentin State Prison after Schwarzenegger denied Williams' request for clemency. Schwarzenegger suggested that Williams' supposed change of heart was not genuine because he had not shown any real remorse for killings committed by the Crips.

Criticism came quickly from many quarters, including the Socialist party in France, where the death penalty was abolished in 1981. "I am proud to be a Frenchman," party spokesman Julien Dray told RTL radio. "I am proud to live in France, in a country where we don't execute somebody 21 years later." "Schwarzenegger has a lot of muscles, but apparently not much heart," Dray added.

In Italy, the country's chapter of Amnesty International called the execution of Williams "a cold-blooded murder." "His execution is a slap in the face to the principle of rehabilitation of inmates, an inhumane and inclement act toward a person who, with his exemplary behaviour and his activity in favour of street kids, had become an important figure and a symbol of hope for many youths," the group said in a statement.

In Germany, Volker Beck, a leading member of the opposition Greens party, expressed disappointment. "Schwarzenegger's decision is a cowardly decision," Beck told the Netzeitung online newspaper.

From London, Clive Stafford-Smith, a human rights lawyer specializing in death penalty cases, called the execution "very sad." "He was twice as old as when they sentenced him to die, and he certainly wasn't the same person that he was when he was sentenced," Stafford-Smith said.

Rome Mayor Walter Veltroni, called it "a sad day" and said the city would keep Williams in its memory the next time it celebrated a victory against the death penalty somewhere in the world. Rome's Colosseum, once the arena for deadly gladiator combat and executions, has become a symbol of Italy's anti-death penalty stance. Since 1999, the monument has been bathed in golden light every time a death sentence is commuted somewhere in the world or a country abolishes capital punishment. "I hope there will be such an occasion soon," Veltroni said in a statement. "When it happens, we will do it with a special thought for Tookie."

"Tookie Williams elusive in death row debate," by Dan Whitcomb. (Mon Dec 12, 2005 8:58 PM ET)

LOS ANGELES (Reuters) - Is Stanley Tookie Williams a cold-blooded killer who has duped Hollywood with feigned innocence, phony assertions of redemption and embellished claims of his sway over gangland Los Angeles to escape execution?

Or is Williams, who is scheduled to die shortly after midnight, a wrongly convicted man who nevertheless devoted a quarter century in prison to troubled kids, saving 150,000 lives from behind bars in a campaign worthy of the Nobel Peace Prize?

The debate over the most discussed U.S. execution in recent memory hinges on the wildly divergent views of the 51-year-old man who sits on San Quentin's death row.

The transcripts of Williams 1981 trial paint a disturbing picture of the former Crips gang leader, who was convicted of shooting four people to death with a shotgun during two robberies, later boasting about the gurgling sounds convenience store clerk Albert Owens made as he died. During the trial, prosecutors say, Williams plotted to kill a sheriff's deputy and an accomplice who was expected to testify against him, then blow up a bus full of inmates with dynamite to escape in the resulting chaos.

After the jury read their guilty verdict Williams, according to transcripts, looked to jurors and mouthed: "I'm going to get each and every one of you motherf------." Williams supporters, who include film star Jamie Foxx and rapper Snoop Dogg, charge that there was no evidence linking him to the crimes, suggesting he was railroaded by a racist jury after three blacks were removed from the panel.

DOES TOOKIE MATTER?

Years later, even the composition of the jury pool is still in dispute. Williams supporters have said that it was all white, while prosecutors say that there was at least one black and one Hispanic on the panel.

Prosecutors say evidence showed Williams purchased the 12-gauge shotgun used in the crimes and point to testimony by an accomplice that Williams shot Owens. Two witnesses said he confessed to the murders. Williams declined to testify in his defense, calling his stepfather, girlfriend and two fellow inmates as witnesses.

Defenders say he found redemption in San Quentin, writing books urging children to reject violence and renouncing his gang life. He offered counseling by telephone to school kids. They say his stature as a "founder" of the notorious Crips gives him a unique ability to steer youth away from gangs and assert that he has saved 150,000 lives. He has been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize five times for his anti-gang work and four times for the literature prize by backers who include university professors from the United States and Europe.

But gang experts dispute Williams' claims to have founded the Crips and say he has little influence over teens. Los Angeles Police Chief Bill Bratton has said that few gang members had likely heard of Williams before press coverage of his execution.

Williams has said he now regrets his role in the Crips but has refused to debrief authorities on the gang, saying that doing so would brand him a "snitch." Others have said that Williams' books are a crass publicity campaign and have sold only a few hundred copies each. A spokesman for Williams' publisher, Power Kids Press, refused to give out sales figures for the eight books but said three were still in print. "Calif. executes former gang leader Tookie Williams." (Tue Dec 13, 2005 3:38 AM ET)

SAN QUENTIN, California (Reuters) - Former Crips gang leader Stanley Tookie Williams was executed by lethal injection early on Tuesday at California's San Quentin State Prison as punishment for murdering four people during 1979 robberies.

The execution in the high-profile case follows California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger's rejection of a clemency petition and the denial of last-minute legal appeals by top courts.

"The execution of Stanley Tookie Williams; Outside San Quentin prison Monday night, under the floodlights, death penalty opponents prayed, sang hymns and cursed the Terminator," by Adam Shemper and Jonathan Stein.

Dec. 13, 2005 | Stanley Tookie Williams was executed by lethal injection at California's San Quentin prison early Tuesday morning. He was 51 years old.

Williams walked into the execution chamber, a semioctagonal room with a padded green gurney and flooded with pale white light. He lay down. Guards strapped him in. A guard kept a hand on Williams' shoulder. A nurse had difficulty finding a vein in his left arm. She accidentally drew blood. It took 12 minutes to prepare the IVs. Williams held his head up. He looked at the press -- 17 journalists in all. He looked at his loved ones -- five of them present -- and mouthed words that journalists couldn't hear or understand.

At 12:21 a.m., the first drug, five grams of sodium pentothal to make Williams unconscious, was pumped into his arm. That was soon followed by injections of 50 cc's of pancuronium bromide to stop his breathing and 50 cc's of potassium chloride to stop his heart. After a few minutes, Williams' stomach begin to spasm and contract. Soon he was not moving. The roomful of witnesses sat in silence looking at Williams' unmoving body. Three of his passionate supporters, including Barbara Becnel, a former Los Angeles Times reporter, cried out, "The state of California just killed an innocent man."

A circular flap in a heavy metal door near Williams' body was opened by someone unseen. A piece of paper was slipped through and was unrolled by a female guard who made the final announcement. Stanley Tookie Williams was dead at 12:35 a.m.

Inside San Quentin's media center, journalists finally sprung into action. Most had been here over four hours. The décor was like that of an old library, with drab purple carpeting and bright halogen lighting. A trophy case stood next to instructional videos on what to do if taken hostage. A stage with a folding table and the American flag was at the front of the room. "It looks like they do plays here," one journalist had said earlier. "They could put on 'Annie.'"

As journalists waited, one guy sketched in a notebook. "Monday Night Football" played on a small TV. Others flipped through the press package prepared by the San Quentin Press. It opened with three pages of pictures of a young Albert Owens, followed by pictures of his dead body, lying in a pool of blood next to empty Pepsi cans. On another page that addressed Williams' Nobel Prize nomination, the booklet explained that over 140 nominations are submitted each year and that former nominees have included Hitler, Stalin and Mussolini.

But now journalists clutched their BlackBerrys, hoping to get the first e-mail from their colleague who witnessed the execution. They began tapping the heels of their polished shoes. A photographer took a picture of their faces lit up by their hand-held devices' blue glow. A TV cameraman walked up and started filming. When word broke out of the official time of death, a journalist got on his cell, "Hey, Joe, it's me. It's 12:35!" People ran to their camera stations.

People standing outside said prayers. They sang "We Shall Overcome," although a girl sitting on top of a trailer said, "I don't believe that. I'm not singin'." A Richmond, Calif., reverend began shouting through a megaphone: "I'm tired of singin'! I'm tired of talkin'! Do somethin'! Let's do somethin'!" He marched out to a chorus of amens, hollering and people following him. It was as if everyone decided to leave and follow the one person who was angry and ready for action.

A Native American man on the other side of the street held a large upside-down American flag with a white swastika painted in the blue field of stars. He was shouting at the "white maggots" who had defiled his land, who had oppressed and enslaved his people. He yelled at the blond news anchors below him, "You're all immigrants. This is my land you've been poisoning for the last 500 years." He lighted the flag on fire as a black woman told him he shouldn't do that, that he should have more pride in this nation. He responded that it was time for a "true indigenous people's revolution." Then the white picket fence he was holding onto broke and he fell down the small embankment. Then the people he'd been arguing with lifted him up and asked him if he was OK. "Yeah," he said. "I'm OK."

Williams' last chance had been clemency. But early in the afternoon on Monday, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger had made his decision. Williams had never apologized nor showed remorse for his victims, the governor's statement said, so there could be no clemency.

Williams had been convicted of murdering four people. He was found guilty of shooting Albert Owens during a 7-Eleven store robbery on Feb. 27, 1979, and shooting Yen-I Yang and Tsai-Shai Yang and their daughter, Yee-Chen Lin, 12 days later at a Los Angeles motel the family owned. He was sentenced to death in 1981. He maintained his innocence until the end.

Williams' last visitor on Monday was 67-year-old Richmond resident Fred Davis Jackson, who had been coming to see him since 1997. Williams wore his regular blue prison uniform and was in good spirits on Monday, according to Jackson. "This time I couldn't hug him like I wanted to. He was handcuffed; and he's so big, it's hard to get your arms around him." Williams had been on suicide watch, so a guard sat in the room with him. He had refused an official last meal. But there was turkey there, according to Jackson. "He didn't eat any, though," he said. "And I didn't have an appetite neither." The warden later reported that Williams only drank water and milk.

"We said goodbye, like we always do," Jackson said. That was at 6 p.m. It was dark out and getting colder. "I said, 'I'll see you later.' We acted like nothing was going to happen. I gave him a regular goodbye because his faith is so strong. And when I said that I'd see him tomorrow, I was saying that he would be with me no matter what." Soon after, Williams was moved and saw no more visitors.

Earlier Monday, Williams met with several friends and supporters, including the Rev. Jesse Jackson and Becnel. For 10 years, Becnel had helped Williams broker gang truces and carry his message to inner-city youth. She had helped him write a series of books for kids and teenagers. The intent of the books was to inform readers of the perils of gang life, which Williams, who co-founded the Crips gang in Los Angeles, had experienced firsthand.

In the afternoon, outside the prison's main gate, Jackson was harangued by conservative L.A. radio shock jocks John Ziegler and John Kobylt, who were pushing microphones in his face and yelling: "Name one of the victims! Name one." Jackson ignored them and tried to walk away. He never answered the question. "You don't know. Answer the question. You don't know, do you?" At one point, sheriff's deputies stepped in and pushed the men in opposite directions. Adjacent to the prison sits Point San Quentin Village, a town of 75 people living in quaint houses, condos and cottages nestled into the hill flush against the prison fences.

As night approached, floodlights shone down on Main Street. It looked like a movie set. Some residents had fled. The television and radio trucks were backed into their driveways, lawns and gardens. Reporters worked out of some of their houses, and NBC-TV broadcast from a balcony. Locals charged upward of $2,500 for the space -- the going rate for previous executions had been $1,000. News anchors and reporters were lined up one after the other in their spotlights, and were on every 30 minutes, as if they were doing a play by play.

Actor Mike Farrell -- well known for his role as B.J. Hunnicutt on "M*A*S*H" and as an advocate against the death penalty -- stood before a crowd of gathering protesters and a swarm of media and spoke out against Gov. Schwarzenegger's decision. He said Williams' lawyers met with the governor Dec. 8, then left and they didn't hear from him for 97 hours. "He left Stanley Williams to twist in the wind," Farrell said. "All of us are not only disappointed but are disgusted."

A California Highway Patrol officer told us there were possibly 4,000 people gathered. (More likely the number was closer to 2,000.) But the officer did not say that that number represented a diverse group of African-Americans, Native Americans, whites, nuns, ministers, Buddhists, Christians, Jews and members of the Nation of Islam.

The night wore on and six women -- who called themselves the "Threshold Choir" -- stood in a circle holding burning candles. They sang hymns and prayers. Their voices, almost whispers, were intermittently drowned out by helicopters flying overhead. Below them, people sitting on the beach looking out over the bay, which reflected the dark magenta and violet city light. No one seemed to be talking, as if they were lost in meditation and prayer. Joan Baez sang "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot."

In the San Francisco Bay Area, people had been gathering for days in support of Williams and in protest against the death penalty. On Sunday, at an American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California ceremony in downtown San Francisco, 700 people showed up to honor Sister Helen Prejean. She received the Chief Justice Earl Warren Civil Liberties' Award. Past winners have included Rosa Parks, Thurgood Marshall and Farrell, who was there moving through the crowd. But it was clear that Williams was on everyone's mind.

Dorothy Ehrlich, executive director of the ACLU-NC, said, "No one should be put to death without the world watching." Sean Penn introduced Sister Helen. They knew each other from working on "Dead Man Walking" together, the movie that starred Susan Sarandon and Penn, and depicted Sister Helen's experience ministering to Patrick Sonnier and watching him die in the electric chair in 1984 in the state penitentiary in Angola, La. At the ceremony she posed a question to the audience: "What if we put 1,000 condemned people in a stadium and shot them?" And then answered it sharply, "The whole world could see. We have killed 1,000 people and nobody saw."

Earlier that morning, members of the anti-capital-punishment group Death Penalty Focus met in Sausalito, Calif., for a fundraiser brunch. Executive director Lance Lindsey had helped organize it, and organization president Mike Farrell talked informally about Williams to a room of criminal attorneys, professors, business entrepreneurs, a vineyard developer, a private investigator and a psychologist. There were artists and writers. There were people with money. There were liberals who had worked in politics, fundraising and volunteering for various social causes and campaigns.

Farrell, who is tall and has watery blue eyes and white hair, said he met Williams five or six years ago. "He's very impressive. He's very calming, extraordinarily peaceful, given his circumstances," Farrell said. "The transformation -- from his perspective, redemption -- is visible. He's quiet. He speaks like an educated man, interestingly articulate. To use an odd word, he's sweet."

Farrell stood in front of a large fireplace. He had helped defend condemned inmates for more than 25 years, starting just after 1976, when the U.S. reinstated the death penalty. "We all have a finger in it," Farrell said. "We all have a finger in the execution of Stanley Williams." He wore a black coat and sweater, dark navy pants. "We must uphold the American principle that we all have human value, and I believe that issue starts with the death penalty." He articulated the issues, talking of the great inequalities in the system, how poor those on death row are, the discrimination, how most death sentences are carried out in the former slave states.

"People like Stanley, people on death rows across this country, I call them 'the invisible people,'" Farrell said, his hands speaking also, as if he were conducting. "The thinking goes that people who are invisible in our own lives can be dispensed with easily." He said he knew the pain of those who had lost family members. "I lost a loved one to murder, and I felt great pain, but it doesn't mean I'm going to stoop to the lowest part of my self."

"I spoke with a woman who lost her loved one in the Oklahoma City bombing," he continued. "She said she didn't want Timothy McVeigh to be executed. She said, 'No, I want him to be skinned alive.' She wanted him to be tortured every day for this rest of his life. Though I understand the feeling, we cannot, as a society, condone anyone acting on those feelings. Otherwise we might as well strap an inmate to a chair, and give the grieving family an ax and have them go out at them, and let there be blood on the walls." There was silence in the room. A woman with her legs folded beneath her on the couch looked as if she might cry.

After midnight on Monday, plenty of people were crying. Following the execution, people trickled down the dark street, and Penn was among them. We asked him how one could ultimately make an invisible person visible. "I feel the answer to your question is right here, among all these people, who came to say what's on their mind, what's in their hearts," he said. And why was he there walking among them, lost in the crowd in his black jacket and faded blue jeans, an unlit cigarette in hand? "For the same reasons these people are here. I'm here to abolish the death penalty."

"Thousands Rally as Tookie Dies; The scene at San Quentin as California executes its controversial inmate," by Karen Breslau. (Updated: 11:10 a.m. ET Dec. 13, 2005)

Dec. 13, 3005 - It was fitting somehow that a death row inmate so famous his life was made into a movie and whose appeal for mercy was rejected by a movie star turned governor was, until his final moments the center of a spectacle. Even as Stanley [Tookie] Williams lay on the execution table in San Quentin just after midnight Tuesday—with thousands rallying on his behalf outside the prison gates—he continued to generate drama. As prison technicians fumbled for 12 minutes trying to insert an intravenous line to introduce the poison that would stop his heart, witnesses reported that a frustrated Williams at one point raised his head and asked his executioners if they needed help finding a vein.

Minutes later, Williams, 51, the co-founder of the Crips street gang and convicted murderer of four, was dead, ending one of California's most dramatic death-penalty battles in decades. Williams's fate was sealed Monday afternoon at around 1 p.m. Pacific time, when Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger rejected Williams's petition for clemency in unusually harsh language. Schwarzenegger, who had remained largely silent as an ever-growing parade of celebrities called on him to commute Williams's death sentence in recognition of his anti-gang activism while in prison, instead issued a scathing rebuke of Williams's claim that his writings and Nobel peace prize nominations were proof that he had redeemed himself during 24 years on death row.

Schwarzenegger instead focused on Williams's refusal to express remorse for the four 1979 shotgun murders that resulted in his death penalty. "Is Williams's redemption complete and sincere, or is it just a hollow promise?" Schwarzenegger said in a written statement. "Without an apology and atonement for these senseless and brutal killings, there can be no redemption." Schwarzenegger even took a swipe at Williams's anti-gang literature, noting that one of his books was dedicated to George Jackson, an infamous prison activist charged with murder and mayhem at San Quentin in the 1970s.

As the afternoon went on, Williams's lawyers filed increasingly desperate appeals with the California Supreme Court, and on Monday evening, with the U.S. Supreme Court, claiming the emergence of new witnesses who could exonerate Williams in the shootings. Even as the legal manueverings were ongoing, a crowd was gathering outside the gates of San Quentin. As Williams met with his final visitors, read his last stack of mail and was prepared by prison officials for lethal injection, the crowd outside listened to anti-death penalty messages from the Rev. Jesse Jackson, folk singer Joan Baez, actors Mike Farrell and Sean Penn and scores of local leaders.

By Monday evening, the streets of Point San Quentin Village, a small seaside hamlet of 50 houses on the road leading to the prison, were packed with more than 2,000 people. The blazing white floodlights of the prison lit up the whole scene like a movie set. Some residents had rented their driveways to television satellite trucks for spot prices that ranged from $1,000 to $3,000 for the night. A portrait photographer, attended by a pair of assistants, had set up a street side studio where he was shooting demonstrators who posed in the lotus position against a white backdrop. "This is beautiful, absolutely beautiful," he said. Next to him, a small group of men were clustered around a banner that said "QUEERS AGAINST EXECUTION." A man selling hot chocolate was being pursued by a man with a "SAVE TOOKIE" sign, shouting "You fascist bastard."

The few anti-Tookie activists—a man carrying blow-ups of the victims' autopsy photos, a guy in a sandwich board saying "BELIEVE IN JESUS"—were quickly swarmed by the crowd, with chants of "Tookie is innocent." In places, the air was rich with the telltale sweet aroma of an illegal substance, suggesting the dozens of riot police standing by could have plenty of work—if they wanted it. A man who appeared to be high on something stumbled by with a sign reading: "My 85-year-old father lost his parents to Hitler and he calls the governor Arnold Hitler." Another sign featured a photomontage of Schwarzenegger's face superimposed by two huge crossed syringes and the words "Stop me before I kill again." A speaker from the San Francisco board of supervisors was on stage, calling Schwarzenegger "a roboton of rightwing mediocrity."

There were also poignant sights: a woman standing alone under a tree with a large photograph of a handsome young man. "My son was a murder victim," read her sign. "He opposed the death penalty. So do I." Small groups of demonstrators clutched candles and held each other tight against the chill wind of the San Francisco Bay. The huge prison complex where Williams was being readied for death glowed under white floodlights. Helicopters swirled overhead.

On a small plywood stage erected in front of the post office (San Quentin, California 94964) under a giant papier-mache figure of Mahatma Gandhi, speakers took turns praising the work of Williams, who authored several books while on death row warning young people against the gang lifestyle. At 10:30 p.m., less than two hours before the execution, a speaker announced that "Stan is in good spirits." At 11:15 p.m, a former gang member named Diego Garcia thanked Williams for saving him, by persuading him to turn his life around. A woman who claimed to be a descendant of Geronimo offered a chant in Cherokee. At 11:30, a small round of "All we are saying is give Tookie a chance" to the melody by John Lennon broke out.

Two minutes later, a speaker announced that Schwarzenegger had denied a second reprieve requested by Williams's lawyers. There is a slight gasp and strains of "We Shall Overcome" waft over the crowd. People started lighting candles. In an inexplicable moment of tastelessness, a local radio personality took the stage to promote a hip-hop CD for Williams. Young people reading passages from Williams's anti-gang books shared the stage with various adult speakers, one of whom compared Williams's struggle to that of civil rights icon Rosa Parks. Another invoked John F. Kennedy. It was one minute before midnight, just before the execution was to begin and many in the crowd were weeping. While most of the speakers on stage were young and African-American, the audience was predominately white and older. A friend of Williams took the stage to tell of his final moments that afternoon with Tookie. "He said 'whatever happens, I'm okay. My conscience is clear.'" A rabbi implored the crowd not to leave at 12:01 when the execution was scheduled to begin. "It can take 10 to 15 minutes until the execution is completed," he warned. "We have to see this through."

At 12:35 a.m. Stanley Tookie Williams was pronounced dead.

"Gang co-founder executed; Governor had rejected clemency for Williams," by Gordon Smith. (December 13, 2005)

SAN QUENTIN – Stanley "Tookie" Williams died by lethal injection early this morning, after Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger yesterday denied a plea for clemency by the convicted murderer and co-founder of the Crips street gang.

Williams, 51, whose case was raised to national prominence in recent weeks by death-penalty foes, black leaders, celebrities and others opposed to his execution, was rendered unconscious by sodium pentothal just after midnight, then injected with pancuronium bromide to stop his breathing and potassium chloride to stop his heart.

He had been on death row since being convicted in 1981 of four shotgun murders in the Los Angeles area. He was the 12th inmate put to death in California since the state's death penalty was reinstated in 1978. Williams steadfastly maintained he did not commit the four murders for which he was convicted, and his supporters – although often offering qualified opinions on his innocence – insisted Williams had been "redeemed" through his extensive anti-gang writings and other efforts during the past 13 years.

In a decision released less than 12 hours before the execution, Schwarzenegger said he was convinced that "cumulatively, the evidence demonstrating Williams is guilty of these murders is strong and compelling." "There is no need to rehash or second guess the myriad findings of the courts over 24 years of litigation," Schwarzenegger wrote in declining to commute Williams' death sentence to life in prison without the possibility of parole. Schwarzenegger noted that considering the countless murders committed by the Crips gang that Williams co-founded, "one would expect more explicit and direct reference to this byproduct of his former lifestyle in Williams' writings and apology for this tragedy, but it exists only through innuendo and inference."

In any case, "It is impossible to separate Williams' claim of innocence (of the four murders) from his claim of redemption," the governor wrote. "Without an apology and atonement for these senseless and brutal killings there can be no redemption." Jonathan Harris, one of Williams' lead attorneys, said Schwarzenegger apparently believed that "an innocent man had to confess in order to get clemency. I could not disagree with that more."

The California Legislature is scheduled to consider a bill in January that would create a moratorium on the state's death penalty until an independent commission can study how it is applied, Harris said. "It would be a sad, tragic and dishonorable day if Stanley Williams (was) the last inmate executed before this moratorium went into effect," he said. Officials with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which has taken up Williams' cause in recent weeks, called Schwarzenegger's decision political, and said they were disappointed and saddened by it.

"He's a first-term governor, he wants a second term, and he's going to make decisions that will appeal to the people who put him in office to get back in office," said NAACP president Bruce Gordon. Gordon said criminal justice in the United States is unequally applied to minorities. "There are too many (condemned inmates), more often black than white, who have been exonerated when all the evidence is presented," he said.

Earlier yesterday, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals denied a last-ditch motion by Williams' lawyers to reopen his case. The court said the claims in the motion were made, and denied, previously, and didn't offer "clear and convincing evidence of actual innocence." Last night, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to block the execution.

Williams, who was moved to the death watch cell adjacent to the death chamber about 6 p.m. was described by prison officals as calm, quiet, thoughtful and respectful of the prison staffers who interacted with him. He did not request a spiritual adviser or last meal. His only request after entering the cell was for a couple of cartons of milk.

The last California governor to grant clemency to a condemned inmate was Ronald Reagan, who commuted the sentence of brain-damaged Calvin Thomas in 1967.

In Los Angeles, police said they didn't expect violence to break out in response to Schwarzenegger's decision. Speaking shortly before the governor's decision was released, Police Chief William Bratton said that "Mr. Williams should not be the poster boy for dealing with the death penalty in this country. . . . He's been convicted of four murders, and God knows what else he's been involved in in his life. He's shown no remorse for those murders, and in recent times he's been discouraging working with the police to deal with murders that continue."

Williams co-founded the Crips street gang in 1971, when he was 18. It since has become one of the nation's most notorious gangs.

In 1981, he was convicted of murdering four people during two robberies: Albert Owens, a night clerk at a 7-Eleven convenience store, and motel owners Yen-I Chang, 76, and Tsai-Shai Yang, 63, and their daughter, Ye-Chen Lin, 43.

After 12 years on San Quentin's death row, Williams renounced his violent past and began writing books, including a series aimed at children warning of the dangers of gangs. Beginning in 2000, death-penalty foes nominated him repeatedly for Nobel prizes for peace and literature.

California Attorney General Bill Lockyer said Nobel Peace Prize nominations average more than 140 annually, and in the past have included Adolf Hitler and Josef Stalin. Criticizing Williams for refusing to take responsibility for the deaths he caused, Lockyer and other law-enforcement officials called the former gang leader an unrepentant killer who tried to avoid execution any way he could.

"Crips Gang Co-Founder Executed in California; Los Angeles Gang Co-Founder Stanley Tookie Williams Executed After Appeals Fail," by Kim Curtis. (AP December 13, 2005)

SAN QUENTIN, Calif. - Convicted killer Stanley Tookie Williams, the Crips gang co-founder whose case stirred a national debate about capital punishment versus the possibility of redemption, was executed Tuesday morning.

Williams, 51, died at 12:35 a.m. after receiving a lethal injection at San Quentin State Prison, officials said. Before the execution, he was "complacent, quiet and thoughtful," Corrections Department spokeswoman Terry Thornton said.

The case became the state's highest-profile execution in decades. Hollywood stars and capital punishment foes argued that Williams' sentence should be commuted to life in prison because he had made amends by writing children's books about the dangers of gangs and violence.

In the days leading up to the execution, state and federal courts refused to reopen his case. Monday, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger denied Williams' request for clemency, suggesting that his supposed change of heart was not genuine because he had not shown any real remorse for the killings committed by the Crips. "Is Williams' redemption complete and sincere, or is it just a hollow promise?" Schwarzenegger wrote. "Without an apology and atonement for these senseless and brutal killings, there can be no redemption."

Williams was condemned in 1981 for gunning down convenience store clerk Albert Owens, 26, at a 7-Eleven in Whittier and killing Yen-I Yang, 76, Tsai-Shai Chen Yang, 63, and the couple's daughter Yu-Chin Yang Lin, 43, at the Los Angeles motel they owned. Williams claimed he was innocent. Witnesses at the trial said he boasted about the killings, stating "You should have heard the way he sounded when I shot him." Williams then made a growling noise and laughed for five to six minutes, according to the transcript that the governor referenced in his denial of clemency.

Some execution witnesses said the nurse who delivered the injection appeared to have trouble finding a vein in Williams' muscular arm. At one point, he uttered something to the nurse and offered to help, said Steve Ornoski, the prison warden. He offered no other final words. "He did seem frustrated," Ornoski said.

After he was declared dead, his supporters shouted in unison: "The state of California just killed an innocent man," as they walked out of the chamber.

About 1,000 death penalty opponents and a few death penalty supporters gathered outside the prison to await the execution. Singer Joan Baez, M A S H actor Mike Farrell and the Rev. Jesse Jackson were among the celebrities who protested the execution. "Tonight is planned, efficient, calculated, antiseptic, cold-blooded murder and I think everyone who is here is here to try to enlist the morality and soul of this country," said Baez, who sang "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot" on a small plywood stage set up just outside the gates.

A contingent of 40 people who had walked the approximately 25 miles from San Francisco held signs calling for an end to "state-sponsored murder." But others, including Debbie Lynch, 52, of Milpitas, said they wanted to honor the victims. "If he admitted to it, the governor might have had a reason to spare his life," Lynch said.

Former Crips member Donald Archie, 51, was among those attending a candlelight vigil outside a federal building in Los Angeles. He said he would work to spread Williams' anti-gang message. "The work ain't going to stop," said Archie, who said he was known as "Sweetback" as a young Crips member. "Tookie's body might lay down, but his spirit ain't going nowhere. I want everyone to know that, the spirit lives."

Among the celebrities who took up Williams' cause were Jamie Foxx, who played the gang leader in a cable movie about Williams; rapper Snoop Dogg, himself a former Crip; Sister Helen Prejean, the nun depicted in "Dead Man Walking"; and Bianca Jagger. During Williams' 24 years on death row, a Swiss legislator, college professors and others nominated him for the Nobel Prizes in peace and literature.

"There is no part of me that existed then that exists now," Williams said recently during an interview with The Associated Press. "I haven't had a lot of joy in my life. But in here," he said, pointing to his heart, "I'm happy. I am peaceful in here. I am joyful in here."

Williams' statements did not sway some relatives of his victims, including Lora Owens, Albert Owens' stepmother. In the days before his death, she was among the outspoken advocates who argued the execution should go forward.

"(Williams) chose to shoot Albert in the back twice. He didn't do anything to deserve it. He begged for his life," she said during a recent interview. "He shot him not once, but twice in the back. ... I believe Williams needs to get the punishment he was given when he was tried and sentenced."

"Calif. killer turned anti-gang author executed," by Adam Tanner. (Tue Dec 13, 2005 4:37 AM ET)

SAN QUENTIN, Calif., Dec 13 (Reuters) - California prison officials executed Stanley Tookie Williams, 51, the ex-leader of the Crips gang who brutally killed four people in 1979, early on Tuesday after top courts and Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger rejected final appeals to spare his life. The time of death was 12:35 a.m. PST on Tuesday.

The execution by lethal injection at San Quentin State Prison north of San Francisco followed a frenzied but failed effort to reopen the case by supporters of Williams, who repudiated gang life during his 24 years on Death Row. The case has generated widespread interest and fierce debate over the death penalty in the United States because Williams has written a series of books warning young people against gangs.

Witnesses said guards struggled for about 12 minutes to place the needle in a vein in his left arm, frustrating Williams who occasionally spoke with the guards preparing his death, asking at one point: "Still can't find it?" After he was strapped down, he raised his head often, especially to look at Barbara Becnel, the editor of his books and foremost supporter who helped bring broad publicity to his case. After his death, Becnel and two other supporters broke the silence in the witness room, saying: "The state of California just killed an innocent man."

A relative of one of the victims wept as the prisoner's supporters made their defiant statement.

Becnel and other supporters said Williams' anti-gang work showed the inmate had changed fundamentally in the half of his life he has spent in prison. But Schwarzenegger and others said his continued protestations of innocence negated any claim that he had redeemed himself. "Stanley Williams insists he is innocent, and that he will not and should not apologize or otherwise atone for the murders of the four victims in this case," Schwarzenegger wrote on Monday in denying clemency. "Without an apology and atonement for these senseless and brutal killings there can be no redemption." "Based on the cumulative weight of the evidence, there is no reason to second guess the jury's decision of guilt or raise significant doubts or serious reservations about Williams' convictions and death sentence."

CROWDS PROTEST AT PRISON

Civil rights leader Rev. Jesse Jackson said he broke the news on Monday afternoon that Schwarzenegger had denied clemency as Williams met several supporters in prison. "He said 'Don't cry, let's remain strong,'" Jackson told Reuters. "He smiled, you know, with a certain strength, a certain resolve." "I think he feels a comfort in his new legacy as a social transformer," Jackson said.

"I am not the kind of person to sit around and worry about being executed," Williams told Reuters last month. "I have faith and if it doesn't go my way, it doesn't go my way."

Williams was convicted in 1981 of killing Albert Owens as he lay face down on the floor of a 7-Eleven convenience store in a $120 robbery. Two weeks later, Williams shot dead an elderly Taiwanese immigrant couple running a motel, as well as their visiting daughter. "In this case, the one thing that would be the clearest indication of complete remorse and full redemption is the one thing Williams will not do," Schwarzenegger wrote.

Prison officials said Williams was composed and cooperative and said he did not request a final meal after eating oatmeal and drinking milk earlier in the day.

Some 2,000 opponents of the death penalty gathered outside the gates of San Quentin, where Jesse Jackson addressed the crowd and folk singer Joan Baez sang spirituals. Some brought small children despite the late hour. "I wanted to show them we oppose the death penalty even if you are a murderer," said Christina Williams, 23, who held hands with her two young children and wore a "Save Tookie" button on his jacket. "He changed his life and deserves a second chance."

The nation's top courts disagreed. On Monday, the U.S. Supreme Court as well as the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals rejected final appeals to reconsider the case. Pondering their fifth habeas corpus petition on the case over the past quarter century, the state Supreme Court also rejected the petition on Sunday night. (Additional reporting by Michael Kahn)

"THE TOOKIE FILES," by Michelle Malkin· (November 26, 2005 03:33 PM)