45th murderer executed in U.S. in 2006

1049th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Mississippi in 2006

8th murderer executed in Mississippi since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

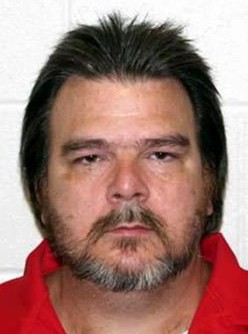

Bobby Glen Wilcher W / M / 19 - 43 |

Katie Belle Moore W / F / 47 Velma Odell Noblin W / F / 52 |

06-15-94 |

Summary:

Wilcher met Katie Belle Moore and Velma Odell Noblin at a Scott County bar and at closing time persuaded the women to take him home. Under this pretext, he directed the women down a deserted service road in the Bienville National Forest where he robbed and brutally murdered the women by stabbing them a total of 46 times. Thereafter, Wilcher was stopped for speeding by the Forest Police Department between 1:00 and 2:00 a.m. He was alone and was driving victim Noblin's car. The victims' purses and one victim's brassiere were on the back seat. Wilcher was covered in blood; he had a bloody knife in his back pocket that had flesh on the blade. Wilcher explained his condition by telling the policeman that he had cut his thumb while skinning a possum. The officer followed Wilcher to the hospital, where Wilcher's wound was cleaned and covered with a band-aid. Another officer was called to the hospital to observe Wilcher, the knife, the car, the purses, and the brassiere. The officers left the hospital on an emergency call. Wilcher went home. The next morning, he abandoned Noblin's car at an apartment complex. Wilcher also threw the victims' purses and some of the victims' clothing in a ditch. He was arrested later that day. The victims' jewelry was subsequently found in Wilcher's bedroom.

Citations:

Wilcher v. State, 448 So.2d 927 (Miss. 1984) (Direct Appeal - Noblin Victim).

Wilcher v. State, 455 So.2d 727 (Miss. 1984) (Direct Appeal - Moore Victim).

Wilcher v. State, 479 So.2d 710 (Miss. 1985) (PCR).

Wilcher v. State, 635 So.2d 789 (Miss. 1993) (PCR After Remand).

Wilcher v. State, 697 So.2d 1123 (Miss. 1997) (Direct Appeal After Remand).

Wilcher v. State, 863 So.2d 719 (Miss. 2003) (PCR).

Wilcher v. State, 863 So.2d 776 (Miss. 2003) (PCR).

Wilcher v. Hargett, 978 F.2d 872 (5th Cir. Miss. 1992) (Habeas).

Final/Special Meal:

Two dozen jumbo fried shrimp with tarter sauce and ketchup, two large orders of fried onion rings and french

fries, one raw regular onion, six pieces of garlic bread, two cold 32 oz. Cokes, two 32 oz. strawberry milkshakes.

Final Words:

Declined.

Internet Sources:

Mississippi Department of Corrections - Death Row

NEWS RELEASEOctober 18, 2006 Execution of Bobby G. Wilcher

7:00 p.m. News Briefing

Parchman, Miss. - The Mississippi Department of Corrections (MDOC) today conducted the mandated execution of state inmate Bobby Glenn Wilcher. Inmate Wilcher was pronounced dead at 6:42 p.m. at the state penitentiary at Parchman.

MDOC Commissioner Christopher Epps said during a press conference following the execution that the evening marked the close of the Bobby Glenn Wilcher case. It involved 24 years of appeals on death row in the capital murders of Katie Belle Moore and Velma Odell Noblin in Scott County. Epps said, “It is our agency’s role to see that the order of the court is carried out with dignity and decorum. That has been done. Over the course of 24 years, state death row inmate Bobby Glenn Wilcher was afforded his day in court and in the finality, his conviction was upheld all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. The cause of justice has championed over wrong.”

A“In this final chapter tonight, it is our fervent hope that the families of Ms. Moore and Ms. Noblin may now begin the process of healing. Our prayers go out to you as you continue life’s journey,” said Epps. Epps concluded his comments by commending Deputy Commissioner of Institutions Emmitt Sparkman, MSP Superintendent Kelly and the entire Mississippi State Penitentiary security staff for their professionalism during the process.

Date: October 18, 2006

Contact: Tara Booth

Phone: (601) 359-5701, MSP Media Center (662) 745-6148

Fax: (601) 359-5738

October 18, 2006 Scheduled Execution of Bobby G. Wilcher

4:45 p.m. News Briefing

Parchman, Miss. - The Mississippi Department of Corrections (MDOC) today briefed members of the news media of death row Inmate Bobby G. Wilcher’s activities from 2:00 p.m. to approximately 4:30 p.m., including telephone calls and visits.

Update to Inmate Wilcher’s Collect Telephone Calls

Wednesday, October 18, 2006

Inmate Wilcher made telephone calls today to Lindy Wells (friend) and Cliff Johnson (attorney).

Update to Inmate Wilcher’s Visits

Visitors left Unit 17 at 4:00 p.m.

• Lindy Lou Wells (friend)

• Cliff Johnson (attorney)

• Angela Parnell (paralegal)

• Stan Wilson (spiritual advisor)

Activities of Inmate Wilcher:

Inmate Wilcher ate his last meal at approximately 12:45 p.m. today and took a shower at 4:15

p.m. He has requested no sedative and has chosen not to participate in communion. Inmate

Wilcher remains under observation. As reported earlier, Wilcher is somber and quiet.

October 18, 2006 Scheduled Execution of Bobby G. Wilcher

2:00 p.m. News Briefing

Parchman, Miss. - The Mississippi Department of Corrections (MDOC) will hold three news briefings today related to events surrounding the October 18th scheduled execution of death row Inmate Bobby G. Wilcher, MDOC #34602. The following is an update on Inmate Wilcher’s recent visits and telephone calls, activities, last meal to be served, and the official list of execution witnesses.

Visits with Inmate Bobby G. Wilcher

Tuesday, October 17, 2006 Attorney Cliff Johnson and paralegal Angela ParnellWednesday, October 18, 2006 Allowed visits with attorneys, spiritual advisor and friends from 1:00 p.m. until 4:00 p.m.

Currently visiting with Inmate Bobby G. Wilcher:

• Lindy Lou Wells (friend)

• Cliff Johnson (attorney) 2pm

• Angela Parnell (paralegal) 2pm

Activities of Wilcher

• This morning for breakfast, Inmate Wilcher was offered coffee, biscuits and jelly, milk, sausage, and

boiled eggs. He declined all but the coffee.

• Inmate Wilcher was offered lunch today consisting turkey meat, two slices of bread, english peas, rice,

cheese, two cups of tea, and two oranges. Inmate Wilcher ate two oranges.

• Inmate Wilcher has access to a telephone to place unlimited collect calls to persons on his approved

telephone list. He had access to the phone from 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. on Tuesday and will have access today,

October 18th, from 8:00 a.m. until 5:00 p.m.

• According to the MDOC correctional officers that are posted outside his cell, Inmate Wilcher is observed

to be in a quiet mood.

Approved Telephone List

Lindy Lou Wells (friend), Sister Patricia Tallent (friend), James H. Wilcher (half-brother), Randy Wilcher

(nephew), Jan Wilcher (spouse of Randy), Cliff Johnson (attorney of record), Angela Parnell (paralegal), Van

Williams (friend), Tomika Harris (friend), Charles Press, Debra Saba-Press (friends), Bill May (friend), Ken

Rose (friend), Camille Evans (friend), Robert Brooks (friend), Kendra Lee-Lindsey (friend), Jane Hicks (friend),

and Iva Nell Wilcher (sister-in-law), Danny Wilcher (brother), Penny Easterling (sister), Craig Trueblood

(spiritual advisor), Joseph Stan Wilson (spiritual advisor).

Wilcher’s Remains

Inmate Wilcher has requested that his body be released to Colonial Funeral Home, Forest, Mississippi.

Last Meal

Inmate Wilcher requested the following as his last meal:

Two dozen jumbo fried shrimp with tarter sauce and ketchup, two large orders of fried onion rings and french

fries, one raw regular onion, six pieces of garlic bread, two 32 oz. cold Cokes, two 32 oz. strawberry milkshakes.

Inmate Wilcher’s Collect Telephone Calls

Tuesday, October 17, 2006

Phone calls were made by Inmate Wilcher to Lindy Wells (friend), Bill May (friend) and Van Williams (friend).

Wednesday, October 18, 2006

Phone calls thus far today made by Inmate Wilcher to Lindy Wells (friend) and Cliff Johnson (attorney).

Execution Witnesses

Attorneys for the condemned Angela Parnell (paralegal) and Cliff Johnson (attorney)

No member of the condemned’s family At Inmate Wilcher’s request.

Two members of each of the victims’ family Noblin Family: Billy Sessions (brother) and Stacey Boyd (granddaughter)

Moore Family: Tommy Moore (son) and Joe Rigby (nephew)

Sheriffs Harold Jones, Scott County Deputy Sheriff and

James Haywood, Sunflower County Sheriff

Governor’s Witness C. Daryl Neely, Policy Advisor

8 Members of the Media Jack Elliot, Jr., Associated Press

Sidney L. Salter, The Clarion-Ledger

Chris Allen Baker, The Scott County Times

Robert H. Smith, The Cleveland News Leader

Melissa Faith Payne, WJTV

Gregory M. Flynn, WAPT

Jason Law, WXVT

Andrea "Andi" Peterson, Miss. News Network

"Executed: Bobby Glen Wilcher: 11 minutes conclude 24-year ordeal," by Jimmie E. Gates. (October 19, 2006)

PARCHMAN — Family members of two Scott County women brutally murdered by Bobby Glen Wilcher hugged corrections officials after Wilcher was executed Wednesday evening at the Mississippi State Penitentiary. It took 24 years for Wilcher's execution to be carried out, but it took only about 11 minutes for him to die by lethal injection for the 1982 slayings of Katie Bell Moore and Velma Odell Noblin. Both mothers were stabbed more than 20 times each.

"He didn't want to be executed. He was acting like the other seven executions I have been involved in," Mississippi Department of Corrections Commissioner Chris Epps said. Wilcher, 43, did not expect another stay, corrections officials said. The U.S. Supreme Court, about 90 minutes before the scheduled 6 p.m. execution, refused to consider his emergency stay request. He was pronounced dead at 6:42 p.m.

In July, Wilcher received a last-minute reprieve from the U.S. Supreme Court after the court said it needed more time to consider the case. He voluntarily gave up his federal appeals in June but later tried to have them reinstated. When asked in the death chamber if he wanted to make a statement, Wilcher said, "I have none." But earlier Wednesday, Wilcher told Epps, "I messed up a good thing, and now I can't do anything about it." Epps said Wilcher made the comment when he asked him about killing the women.

Wilcher killed Moore and Noblin after meeting them at a Forest bar. He persuaded them to drive him home and diverted them down a deserted road where he killed them. Wilcher never apologized for the slayings.

For the families of the victims, there finally is closure. "The families are relieved. It was long overdue," said Moore's nephew, Joe Rigby, who was Scott County's coroner in 1982. He is now the circuit clerk. Wilcher said before his execution that he didn't want a sedative but changed his mind as the time neared. Epps said Wilcher indicated he got only an hour of sleep Tuesday night because he was writing goodbye letters.

Wilcher's attorney, Cliff Johnson, who witnessed the execution, said Wilcher spent his entire adult life in dehumanizing conditions but maintained the capacity to care deeply for other people, to show kindness and to demonstrate forgiveness and understanding. "He was my friend, and I will miss him," Johnson said. About eight anti-death penalty activists gathered on the penitentiary grounds before the execution.

Wilcher was visited Wednesday by Lindy Wells, a Yazoo City woman with whom he had become friendly. Also, Johnson and his paralegal, as well as a spiritual adviser and prison chaplains, visited Wilcher in his cell, which was 19 steps from the execution chamber. Wilcher also made collect calls to Wells before her visit and to others.

Epps said Wilcher explained that it was Wells who got him interested in fighting to have his appeals reinstated. Epps said Wilcher told him Wells was a jury member in one of his trials. He had been tried separately for each slaying. The Clarion-Ledger attempted to contact Wells but was told by a female who answered the telephone late Wednesday after the execution that she wasn't at home.

Wilcher's last meal request was for two dozen shrimp, two large orders of fried onion rings, two orders of fries, one raw onion, six pieces of garlic bread, two cold, 32-ounce Cokes and two strawberry shakes. He wanted to share the food with prison personnel, Epps said. Wilcher had a similar meal request in July.

This time, Wilcher's last meal was served at 12:45 p.m. instead of the traditional 4 p.m. Epps said it was moved for logistical purposes to allow more time for things such as a haircut for Wilcher. "It was better to get it out of the way," Epps said of the earlier time for the meal. Epps said it's a change he probably will continue.

Wilcher's body was released to Colonial Funeral Home in Forest. He requested that his personal items be given to his attorney. At his request, none of Wilcher's family attended his execution. But Wilcher talked Tuesday by telephone to his mother, who is incarcerated in the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility on a drug conviction. His father recently died, Epps said. Epps said if there is any lesson to be learned from Wilcher's case, it is that "crime doesn't pay."

Bobby Glen Wilcher declined breakfast and drank only coffee. He had his last meal at 12:45 p.m. From 1-4 p.m., he visited with attorney Cliff Johnson, friend Lindy Lou Wells, paralegal Angela Parnell and spiritual adviser Stan Wilson. At 4:15 p.m. he took a shower

Final minutes find killer with nothing to say," by Sid Salter. (October 18, 2006)

PARCHMAN — After more than 24 years on death row, Bobby Glen Wilcher simply went to sleep Wednesday evening. The last sight I saw from the execution chamber door was a purple sunset dropping behind the cotton fields on the wide Delta horizon - before the barbiturates and paralyzing agents were pumped into Wilcher's tattooed left arm at 6:31 p.m.

It was in this building - Unit 17, the old death row that is now used only for executions - that I interviewed Wilcher in 1985 and again in 1988. In this decaying old building 18 years ago he told me he stabbed Velma Odell Noblin and Katie Bell Moore on a deserted U.S. Forest Service road on a rainy night in 1982 because "it felt good."

I thought of those words as I watched him dying. But Wilcher said only three words during the final 11 minutes of his life. Offered a chance to make a final statement, he said: "I have none." He never glanced at the victims' family members, who were standing less than five feet from him, behind a glass in a viewing room. Those family members - Stacey Boyd, victim Noblin's granddaughter; Billy Sessions, Noblin's brother; Joe Rigby, Moore's nephew; and Tommy Moore, Moore's son - stood close to the glass, peering intently at Wilcher. Rigby, Boyd and Moore linked arms during the execution while Sessions stood close behind. None of the family witnesses uttered a word during the final minutes of Wilcher's life. When Wilcher was pronounced dead by state Medical Examiner Steven Hayne and Sunflower County Coroner Doug Carr, the four left the room.

Wilcher was strapped to a gurney roughly shaped like a cross with nine wide, tan leather straps. He was dressed in a red prison jumpsuit and white socks. A big man who weighed between 315 and 345 pounds, according to prison officials, Wilcher's long dark hair was clean and combed, his goatee streaked with white. Wilcher was almost perfectly still on the gurney, his eyes closed, throughout most of the execution. His breathing was shallow, and it was clear he had been sedated. The most visible sign of Wilcher's execution was the inexorable turn of his skin from the pasty white of prison life to the pale gray cyanosis of death. Death came at 6:42 p.m.

Mississippi Department of Corrections Commissioner Chris Epps said Wilcher asked for and received a Valium shortly before the execution began, reversing a decision earlier Wednesday to go without one. Rigby was the coroner of Scott County at the time of the murders and the first one to identify the bodies and see the carnage of the multiple stab wounds that claimed their lives.

After the execution, Rigby said: "All I could think about was when I first saw what he'd done to those ladies on the end of that government road. He died such a peaceful death compared to what they endured, to what my aunt endured."

Moore said watching his mother's killer be executed would help him move on with life. "My emotions are better now because it's finally over," Moore said. "We don't have to focus on it all the time. But it just looks to me like he died too peaceful a death compared to the crime he committed."

Leaving the execution chamber, I could not help but remember the wiry, threatening young man I interviewed years ago and the corpulent, middle-aged man on that gurney. The memory and the reality were almost unrecognizable as the same man.

"Convicted Killer Bobby Glen Wilcher Executed." (Oct 18, 2006 07:57 PM EDT)

(AP) Convicted killer Bobby Glen Wilcher was executed by lethal injection Wednesday for the brutal killings of two women in Mississippi in 1982. Wilcher's 6:42 p.m. death at the state penitentiary came two hours after the U.S. Supreme Court declined to intervene as it did on Wilcher's first execution date in July. Corrections Commissioner Chris Epps said Wilcher was in a "quiet mood" throughout the day before being strapped to the death chamber gurney.

"Despite the needless delay caused by the U.S. Supreme Court, justice has finally been rendered for these horrible crimes," Gov. Haley Barbour said in a news release. "The real tragedy in this case is that justice was delayed for more than two decades."

The 43-year-old Wilcher had spent his final hours visiting with his attorney, a spiritual adviser and one friend. "He's not as playful or joyful as he was ... all of that is gone. He's very serious. He feels he will be executed today," Epps said during a mid-afternoon briefing.

Epps said Wilcher on Wednesday asked for a conjugal visit with a woman who had been a juror in one of his trials, but the request was denied. Wilcher and the woman had developed a friendship, Epps said. She was allowed a non-contact visit with Wilcher, along with his attorney Cliff Johnson of Jackson and a paralegal. Wilcher's last meal of shrimp, onion rings, garlic bread, sodas and strawberry milkshakes had been moved to 12:40 p.m. to allow him to spend more time with his visitors, Epps said.

Wilcher was sentenced to death for killing Katie Belle Moore and Velma Odell Noblin in Scott County. After meeting them at a Forest bar, Wilcher persuaded the women to drive him home and diverted them down a deserted road. Their blood-soaked bodies were found sprawled along the muddy banks of the dirt road. Authorities said each woman had been stabbed and slashed more than 20 times.

Wilcher's case has gone through two trials, two re-sentencing hearings and countless appeals, in a legal saga that has spanned more than two decades. He came within minutes of death on July 11 before the Supreme Court ordered a stay. But, the court declined without comment to hear the case on Oct. 2, and his attorney began pushing the case back through the lower courts.

U.S. District Judge Henry Wingate declined stop the execution on Saturday. Wilcher in May had asked Wingate to stop his appeals and go forward with the execution. Wingate granted the request but about a month later Wilcher asked that his appeals be reinstated. Wingate declined, saying he would not allow his court to be held "hostage" by a death row inmate. Wilcher appealed to the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, but the court on Tuesday refused to stop the execution. On Wednesday, Johnson asked the U.S. Supreme Court to again intervene. The court declined.

Epps said Wilcher did not request that any of his family members witness the death. His father is deceased and his mother is imprisoned at the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility in Rankin County for drug possession, Epps said. Wilcher's witnesses for the execution were to include his attorney and a paralegal.

Barbour denied Wilcher clemency before the first scheduled execution. After the July execution was halted, Barbour said in a statement that the "only injustice here is that 24 years have already passed since this murderer earned the death penalty." Mississippi's most recent execution was in December, when John B. Nixon Sr. died by lethal injection for the 1985 contract killing of Virginia Tucker of Brandon.

"Death row execution; Convicted killer Wilcher put to death," by Jack Elliott Jr. (AP Posted on Thu, Oct. 19, 2006)

PARCHMAN, Miss. - Convicted killer Bobby Glen Wilcher was executed by lethal injection Wednesday for the brutal killings of two women in Mississippi in 1982, ending a legal saga that stretched over more than two decades. Wilcher's 6:42 p.m. death at the state penitentiary came two hours after the U.S. Supreme Court declined to intervene as it did on Wilcher's first execution date in July. "I have none," Wilcher, 43, said when he was asked if he had any final words.

Wilcher took two deep breaths and then closed his eyes. Dressed in a red prison jumpsuit, the 5-foot-10, 315-pound inmate stared at the ceiling. He did not look in the direction of either viewing room - one that held the families of his victims and the other his attorney, Cliff Johnson, who had visited with Wilcher most of the day. Corrections Commissioner Chris Epps said Wilcher was in a "quiet mood" throughout the day before being strapped to the death chamber gurney. "Despite the needless delay caused by the U.S. Supreme Court, justice has finally been rendered for these horrible crimes," Gov. Haley Barbour said in a news release. "The real tragedy in this case is that justice was delayed for more than two decades."

Wilcher had spent his final hours visiting with his attorney, a spiritual adviser and one friend. "He's not as playful or joyful as he was... all of that is gone. He's very serious. He feels he will be executed today," Epps said during a midafternoon briefing. Epps said Wilcher on Wednesday asked for a conjugal visit with a woman who had been a juror in one of his trials, but the request was denied. Wilcher and the woman had developed a friendship, Epps said. She was allowed a non-contact visit with Wilcher, along with his attorney and a paralegal. Johnson said Wilcher did not ask for a conjugal visit.

"The woman about whom Commissioner Epps spoke is married and is enrolled in seminary studying to be a minister," Johnson said. "She has been a good friend to Bobby during this most difficult time, and any suggestion by Commissioner Epps or anyone else that there was anything inappropriate about their relationship is shameful." Johnson confirmed that the woman was a juror in one of Wilcher's resentencing trials in 1994. He said Wilcher sought a "contact" visit with the woman, which means they could speak in the same room. "This is very different from a conjugal visit, which clearly has sexual connotations," Johnson said. "Commissioner Epps knows the difference."

Wilcher's last meal of shrimp, onion rings, garlic bread, sodas and strawberry milkshakes had been moved to 12:40 p.m. to allow him to spend more time with his visitors, Epps said.

Wilcher was sentenced to death for killing Katie Belle Moore and Velma Odell Noblin in Scott County. After meeting them at a Forest bar, Wilcher persuaded the women to drive him home and diverted them down a deserted road. Their bodies were found sprawled along the banks of the dirt road. Authorities said each woman had been stabbed and slashed more than 20 times.

Wilcher's case has gone through two trials, two resentencing hearings and countless appeals. He came within minutes of death on July 11 before the Supreme Court ordered a stay. But, the court declined without comment to hear the case on Oct. 2, and his attorney began pushing the case back through the lower courts. U.S. District Judge Henry Wingate on Saturday declined to stop the execution. Wilcher in May had asked Wingate to stop his appeals and go forward with the execution. Wingate granted the request, but about a month later Wilcher asked that his appeals be reinstated. Wingate declined, saying he would not allow his court to be held "hostage" by a death row inmate. Wilcher appealed to the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, but the court on Tuesday refused to stop the execution. On Wednesday, Johnson asked the U.S. Supreme Court to again intervene. The court declined.

Epps said Wilcher did not request that any of his family members witness the death. His father is deceased and his mother is imprisoned at the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility in Rankin County for drug possession, Epps said. Wilcher's witnesses for the execution were to be his attorney and a paralegal.

Barbour denied Wilcher clemency before the first scheduled execution. After the July execution was halted, Barbour said in a statement that the "only injustice here is that 24 years have already passed since this murderer earned the death penalty."

Mississippi's most recent execution was in December, when John B. Nixon Sr. died by lethal injection for the 1985 contract killing of Virginia Tucker of Brandon.

In 1994, a resentencing trial was held that resulted in Bobby Glenn Wilcher's second death sentence for the 1982 murder and robbery of Katie Belle Moore, 45. The case arises out of the gruesome double murder and robbery of Velma Odell Noblin and Katie Belle Moore. The evidence reflects that Bobby Glenn Wilcher, age nineteen, met his two female victims at a Scott County bar on the night of March 5, 1982. When the bar closed at midnight, Wilcher persuaded the women to take him home. Under this pretext, he directed the women down a deserted service road in the Bienville National Forest--where he robbed and brutally murdered the women by stabbing them a total of forty-six times. Thereafter, Wilcher was stopped for speeding by the Forest Police Department between 1:00 and 2:00 a.m. He was alone and was driving victim Noblin's car. The victims' purses and one victim's brassiere were on the back seat. Wilcher was covered in blood; he had a bloody knife in his back pocket that had flesh on the blade. Wilcher explained his condition by telling the policeman that he had cut his thumb while skinning a possum. The officer followed Wilcher to the hospital, where Wilcher's wound was cleaned and covered with a band-aid. Another officer was called to the hospital to observe Wilcher, the knife, the car, the purses, and the brassiere. The officers left the hospital on an emergency call. Wilcher went home. The next morning, he abandoned Noblin's car at an apartment complex. Wilcher also threw the victims' purses and some of the victims' clothing in a ditch. He was arrested later that day. The victims' jewelry was subsequently found in Wilcher's bedroom.UPDATE: Just 27 minutes after the appointed hour that Bobby Glen Wilcher was scheduled to receive a lethal injection, the U.S. Supreme Court stopped the execution for further review. News of the order was received at 6:27 p.m. Tuesday, 53 minutes after the Supreme Court placed the execution on hold as Wilcher waited in his holding cell next to the execution chamber. Corrections officials said Wilcher would be placed on suicide watch and returned him to his previous residence on Death Row, where he lived for 24 years since the murders of his two victims in 1982. A brief two-paragraph order faxed to the Mississippi State Penitentiary did not specify the court's reason for granting the stay. U.S. Associate Justice Antonin Scalia, who initially received Wilcher's final appeal, referred Wilcher's case to the entire court, which voted 6-3 to grant the stay. Justices Scalia, Samuel Alito and Chief Justice John Roberts voted against the stay. The Associated Press in Washington, D.C., reported moments later that the Supreme Court would review the case later in the fall, the earliest being in October when oral arguments could be heard. If the U.S. Supreme Court allows the execution to proceed, the Mississippi Supreme Court will set a new execution date.

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

Bobby Wilcher, MS - October 18

Do Not Execute Bobby Wilcher!

Bobby Glen Wilcher, a 44-year-old white man, was convicted of the robbery and double murder of 47-year-old Katie Belle Moore and 52-year-old Velma Odell Noblin on the night of March 5, 1982. Wilcher, 19 years old at the time, met these two women at a bar that night in Scott County, Mississippi. When the bar closed, Moore and Noblin agreed to drive Wilcher home, per his request. While in Noblin’s brown 1978 Datsun, Wilcher diverted the women down a service road, where he stabbed and killed them. Bobby Glen Wilcher was found guilty in two separate trials in 1982.

Although Wilcher was tried twice and in two different counties (even though the crime was one single incident), Judge Marcus D. Gordon presided over both of these trials. While this may be considered standard in some cases, in this case there is reason to believe that Judge Gordon was bias and should have recused himself. First, one of Wilcher’s numerous appeals states that, during a period between Judge Gordon’s resignation and reelection to the bench, he was listed as an attorney representing Sheriff Glenn Warren, who was charged with extortion. Coincidentally, this was the same sheriff whose testimony provided a bulk of the evidence against Wilcher. Disturbingly, the judge deemed none of this information—the extortion charge or the prior professional relationship—admissible in court. Second, Wilcher’s appeals further discredit Judge Gordon by pointing out that the judge was biased, as demonstrated by one-sided contact, judicial comments, and a jury selection process that resulted in a tainted jury. The Supreme Court of Mississippi denied this appeal solely because these issues should have been brought out during trial or through a direct appeal. Although the Supreme Court of Mississippi did not assert that Judge Gordon was in fact biased, the court did claim that Wilcher’s argument that the judge should have recused himself “may have merit.”

Wilcher also appealed in an attempt to demonstrate in effective assistance of counsel, claiming that his lawyers failed to present mitigating psychological evidence of troubled childhood. Although a psychological and psychiatric evaluation by two state doctors determined that Wilcher was not under extreme psychological or emotional duress during the crime, Wilcher’s counsel was not present during this evaluation. Additionally, no cross examination of the two state-appointed professionals was ever conducted, and no testimony from other mental health professionals was ever presented. The Mississippi Supreme Court claims that even if these factors were altered during the course of the trial, Wilcher cannot show that the outcome would have been different.

Wilcher originally dropped his appeals and is “volunteered’ to be executed. Against the advice of his attorneys, Wilcher requested and won a federal court’s approval to dismiss any further appeals on his case. However, he is now starting up the appeals process.

Please write to Gov. Haley Barbour on behalf of Bobby Wilcher!

"24 years: Killer's appeals 'run out'; Convicted murderer scheduled to die by lethal injection at 6 p.m.," by Jimmie E. Gates (October 18, 2006)

Bobby Glen Wilcher will die today by lethal injection for the 24-year-old murder of two Scott County women unless the U.S. Supreme Court, which refused last week to hear the case, intervenes.

On Tuesday, the 5th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals denied a request to reinstate Wilcher's federal appeals. "I think his appeals have run out," state Attorney General Jim Hood said late Tuesday. "I expect the execution will take place tomorrow at 6 p.m." Wilcher's attorney, Cliff Johnson, said he will file an emergency appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court at 9 a.m. or 9: 30 a.m. today. "We are down to the short road," he said. "We hope there won't be an execution."

Mississippi Department of Corrections Commissioner Chris Epps said he met with Wilcher on Tuesday and he was less jovial and playful than he was in July, when he initially was scheduled to be executed. Epps said Wilcher told him, "I just realized I have something to live for, but it's too late."

The Court of Appeals affirmed U.S. District Court Judge Henry T. Wingate's decision Saturday to deny Wilcher's attempt to reinstate his appeals after he voluntarily waived them in June. "We conclude that petitioner's claims do not merit reinstatement of his petition ... or any other relief before this court," the Court of Appeals' decision reads. Wilcher received a reprieve from death 30 minutes before his scheduled execution July 11, when the U.S. Supreme Court said it needed more time to consider the case on an emergency appeal from Johnson.

Among the issues Johnson raised were whether Wilcher's due process rights were violated because his primary attorney didn't receive adequate notice of the hearing as well as Wilcher's competency to waive his federal appeals since he has a bipolar disorder. But the Supreme Court last week declined to hear an appeal from Wilcher's attorney, leading to a new execution date for Wilcher. On Oct. 9, the state Supreme Court wrote: "After due consideration, this court finds that no impediment exists to setting an execution date."

Epps said two practice executions were conducted Tuesday in preparation for carrying out today's execution. A female friend of Wilcher, Lindy Wells of Yazoo City, will be allowed to visit him today, Epps said. Also, Wilcher's spiritual adviser, MDOC chaplains, Johnson and his paralegal will be visitors.

Wilcher request for his final meal is similar to what he ordered in July. Wilcher said his plan is to share the meal with prison personnel, but Epps said he won't allow that. Wilcher's last meal request is for two dozen shrimp, two orders of fried onion rings and two orders of fries, one raw onion, six pieces of garlic bread, two 32-ounce cold Coke drinks and two strawberry shakes.

Wilcher, 43, was sentenced to death for killing Katie Belle Moore and Velma Odell Noblin in 1982. After meeting them at a Forest bar, Wilcher persuaded the women to drive him home and diverted them down a deserted road. Each woman was stabbed and slashed more than 20 times, according to authorities.

"Granddaughter's lament echoes north to Death Row," by Sid Salter.

As the clock ticks away what are likely the remaining hours and seconds of Bobby Glen Wilcher's life today at the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman, the granddaughter of one of his victims is awaiting closure in the only form that she believes it can come for her and her family. Registered nurse Stacey Boyd, 34, of Forest is the granddaughter of Mrs. Odell Noblin of Forest, who along with Mrs. Katie Bell Moore was on March 6, 1982, lured down a U.S. Forest Service road in Scott County by Wilcher. It was there, Wilcher would later tell me during two chilling interviews on Death Row, that he robbed and stabbed the two women to death and that "it felt good."

The murder was a crime of considerable rage and brutality. Each woman was stabbed more than 20 times. Wilcher left their bodies along a muddy ditch bank in the rain - then drove back to Forest in Mrs. Noblin's brown 1978 Datsun.

Boyd - who was 10 when her "Mamaw" was slain - says of the crime that took her grandmother's life: "As vindictive as it may sound to the bleeding hearts, Bobby Wilcher must die in order for my family to find closure and open a new chapter in our book of life. "On a softer side, our sincere wish is that Wilcher die peacefully in his sleep before the U. S. Supreme Court has a chance to destroy what little faith and trust we have remaining in our justice system. If justice is served when the punishment fits the crime, justice in this case can never be obtained. Let it end."

Boyd remembers her grandmother clearly and fondly. "Mamaw was a small, petite, but feisty soft-spoken lady," said Boyd. "Always eager to assist anyone in need, she never met a stranger. Communication with family and friends was important to her. "At her untimely death, she had 10 children, numerous siblings, and countless nieces, nephews, and grandchildren. The role she was playing at any given time, whether aunt, sister, mom, grandmother, or friend, she poured her heart and soul into it with attentive devotion. "She would have you convinced that you were the most important person in her life and all the world revolved around you. My sister and I spent many days and nights at Mamaw's house. As a child, her home is where I learned peace, love, and harmony," Boyd said.

As Wilcher waits at Parchman, Boyd's lament of pain and loss for her grandmother echoes north from the pine thickets of Scott County to the flat Delta fields surrounding the Parchman prison. Boyd is scheduled to witness Wilcher's execution, along with three other members of the victims' families.

Bobby Thomas of Forest, a retired merchant who was foreman of one of the original two Scott County juries that convicted Wilcher of the murders in 1982, said "there was just no doubt whatsoever" of Wilcher's guilt in the crimes. Thomas also said he has no problems living with the approach of Wilcher's execution as one of those who found him guilty. "Even as a devout Catholic, I find biblical justification for the death penalty and I believe that penalty is justified in this case," said Thomas. "The prosecution made their case. Wilcher has admitted his guilt on numerous occasions and I'm at peace about it."

The Wilcher case is one of only a handful of violent crimes in Scott County over the last three decades that have drawn statewide attention. The case still stirs long conversations in the gas stations, bank lobbies and coffee shops in Forest and the surrounding communities.

Today is not a day of rejoicing for Boyd and the rest of the members of the families of the women Wilcher murdered. Both families have steadfastly expressed their concern for Wilcher's family and acknowledge their pain. Such are small-town relationships. But these Scott County families covet closure. They're searching for a reckoning for the violence on that muddy road long ago. That reckoning appears to be at hand.

Bobby Glen Wilcher was laid to rest in Leake County Thursday after being put to death by lethal injection Wednesday night at Parchman. At the execution, reporters learned about a relationship between Wilcher and a former juror from one of his trials, but the exact nature of their relationship is being disputed.

Lindy Lou Wells was on the jury that sentenced Wilcher to death in 1994, but as time passed the former juror from Yazoo City decided to befriend the convicted killer. "She sought out our office ultimately to find out how to get in contact with Bobby," said Wilcher's attorney Cliff Johnson.

Johnson said it was a spiritual calling that led Wells to support Bobby. She spent time with him just hours before his execution. That's when corrections commissioner Chris Epps made this remark about just how close the two became. "So close that he asked me, could they have a conjugal visit," said Epps.

Johnson says the statement devastated Wells, who is a married grandmother studying to become a minister. He said there was never a formal request for a conjugal visit, only a contact visit. "A contact visit, being in the same room with someone, is very different than a conjugal visit, which clearly means you'll be having sexual relations with someone," Johnson said.

Johnson said Wells is deeply hurt by Epps' remarks, her reputation destroyed as she mourns the death of a close friend. But he said he doesn't believe that was the commissioner's intention and is awaiting a retraction.

"If Chris Epps is the man I think he is, I think he will recognize he made a mistake and apologize, and I think he should," Johnson said. However, contacted by phone, Epps is standing by his remark that Wilcher did request a conjugal visit.

Mississippi Department of Corrections Media Kit (12/14/05)

Contents of Syringes for Lethal Injection

• Anesthetic - Sodium Pentothal – 2.0 Gm.

• Normal Saline – 10-15 cc.

• Pavulon – 50 mgm per 50 cc.

• Potassium chloride – 50 milequiv. per 50 cc.

48 Hours Prior to Execution The condemned inmate shall be transferred to a holding cell adjacent to the execution room.

24 Hours Prior to Execution Institution is placed in emergency/lockdown status.

1030 Hours Day of Execution Designated media center at institution opens.

1500 Hours Day of Execution Inmate’s attorney of record and chaplain allowed to visit.

1600 Hours Day of Execution Inmate is served last meal and allowed to shower.

1630 Hours Day of Execution MDOC clergy allowed to visit upon request of inmate.

1730 Hours Day of Execution Witnesses are transported to Unit 17.

1800 Hours Day of Execution Inmate is escorted from holding cell to execution room.

Witnesses are escorted into observation room.

1900 Hours Day of Execution A post execution briefing is conducted with media

witnesses.

2230 Hours Day of Execution Designated media center at institution is closed.

HISTORY

Since Mississippi joined the Union in 1817, several forms of execution have been used. Hanging was

the first form of execution used in Mississippi. The state continued to execute prisoners sentenced to

die by hanging until October 11, 1940, when Hilton Fortenberry, convicted of capital murder in

Jefferson Davis County, became the first prisoner to be executed in the electric chair. Between 1940

and February 5, 1952, the old oak electric chair was moved from county to county to conduct executions.

During the 12-year span, 75 prisoners were executed for offenses punishable by death.

In 1954, the gas chamber was installed at the Mississippi State Penitentiary, in Parchman, Miss. It replaced the electric chair, which today is on display at the Mississippi Law Enforcement Training Academy. Gearald A. Gallego became the first prisoner to be executed by lethal gas on March 3, 1955. During the course of the next 34 years, 35 death row inmates were executed in the gas chamber. Leo Edwards became the last person to be executed in the gas chamber at the Mississippi State Penitentiary on June 21, 1989.

On July 1, 1984, the Mississippi Legislature partially amended lethal gas as the state’s form of execution in § 99-19-51 of the Mississippi Code. The new amendment provided that individuals who committed capital punishment crimes after the effective date of the new law and who were subsequently sentenced to death thereafter would be executed by lethal injection. On March 18, 1998, the Mississippi Legislature amended the manner of execution by removing the provision lethal gas as a form of execution.

INMATES EXECUTED IN THE MISSISSIPPI GAS CHAMBER

Name Race-Sex Offense Date Executed

Gerald A. Gallego White Male Murder 03-03-55

Allen Donaldson Black Male Armed Robbery 03-04-55

August Lafontaine White Male Murder 04-28-55

John E. Wiggins White Male Murder 06-20-55

Mack C. Lewis Black Male Murder 06-23-55

Walter Johnson Black Male Rape 08-19-55

Murray G. Gilmore White Male Murder 12-09-55

Mose Robinson Black Male Rape 12-16-55

Robert Buchanan Black Male Rape 01-03-56

Edgar Keeler Black Male Murder 01-27-56

O.C. McNair Black Male Murder 02-17-56

James Russell Black Male Murder 04-05-56

Dewey Towsel Black Male Murder 06-22-56

Willie Jones Black Male Murder 07-13-56

Mack Drake Black Male Rape 11-07-56

Henry Jackson Black Male Murder 11-08-56

Minor Sorber White Male Murder 02-08-57

Joe L. Thompson Black Male Murder 11-14-57

William A. Wetzell White Male Murder 01-17-58

J.C. Cameron Black Male Rape 05-28-58

Allen Dean, Jr. Black Male Murder 12-19-58

Nathaniel Young Black Male Rape 11-10-60

William Stokes Black Male Murder 04-21-61

Robert L. Goldsby Black Male Murder 05-31-61

J.W. Simmons Black Male Murder 07-14-61

Howard Cook Black Male Rape 12-19-61

Ellic Lee Black Male Rape 12-20-61

Willie Wilson Black Male Rape 05-11-62

Kenneth Slyter White Male Murder 03-29-63

Willie J. Anderson Black Male Murder 06-14-63

Tim Jackson Black Male Murder 05-01-64

Jimmy Lee Gray White Male Murder 09-02-83

Edward E. Johnson Black Male Murder 05-20-87

Connie Ray Evans Black Male Murder 07-08-87

Leo Edwards Black Male Murder 06-21-89

PRISONERS EXECUTED BY LETHAL INJECTION

Name Race-Sex Offense Date Executed

Tracy A. Hanson White Male Murder 07-17-02

Jessie D. Williams White Male Murder 12-11-02

MISSISSIPPI STATE PENETENTIARY

• The Mississippi State Penitentiary (MSP) is Mississippi’s oldest of the state’s three institutions

and is located on approximately 18,000 acres in Parchman, Miss., in Sunflower County.

• In 1900, the Mississippi Legislature appropriated $80,000 for the purchase of 3,789 acres known

as the Parchman Plantation.

• The Superintendent of the Mississippi State Penitentiary is Lawrence Kelly.

• There are approximately 1,239 employees at MSP.

ABOLISH ARCHIVES (12/14/05)

MISSISSIPPI:

The families of Katie Belle Moore and Velma Odell Noblin are now waiting for the next step in a long legal battle with the killer of the 2 women. The Mississippi Supreme Court ruled last week that Bobby Glen Wilcher was no longer allowed post-conviction appeals. An assistant attorney general said it could be 2 to 7 years before the court will set an execution date.

The Wilcher Case File

The following is a chronological and factual glimpse at Bobby Glen

Wilcher's life, the events that led up to the murder of Katie Belle Moore

and Velma Odell Noblin, and the legal battle that has taken place since

Wilcher's arrest.

BACKGROUND AND YOUTH

*Bobby Glen Wilcher was born on Nov. 15, 1962, in Jackson, the son of

Eugene and Mildred Wilcher.

*Wilcher was 1 of 4 children: Danny, a brother; Ronald, a brother who died

at the age of 6 months; and Penny, a sister.

*The family moved to Scott County while Wilcher was a young boy prior to

his entering grade school.

*From 1969 to 1977, Wilcher attended Lake Attendance Center from grades 1

through 8.

*Wilcher was admitted to Columbia Training School and Oakley Training

School. Records do not reflect dates of time served.

*Convicted of grand larceny in Hinds County on Sept. 19, 1979. Wilcher was

sentenced to 5 years with 3 years suspended. He served one year in the

Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman and was released on Oct. 3,

1980.

*Wilcher was married in Smith County on Nov. 7, 1980. He later divorced.

*Wilcher and his wife gave birth to a daughter in 1981.

The murders of Moore and Noblin

*Family members last saw Noblin and Moore on Friday, March 5, 1982, when Noblin picked Moore up from her house. The 2 friends were going to Robert's Drop-In, a popular night spot in Forest.

*According to later testimony, Noblin, Moore and Wilcher are seen leaving Robert's Drop-In together in Noblin's car. According to testimony, Wilcher reportedly asked Moore for a ride home. Moore agreed since she knew Wilcher from her time babysitting him.

*According to a published interview in the Nov. 6, 1985, edition of The Times with former Times Editor Sid Salter, Wilcher says he led the women to the deadend road as if he was giving them directions to his house.

Wilcher says in the interview that he and Noblin "went off a few feet" and got into an argument. Wilcher says it was not until after they were out of the car and in an argument that he drew a knife. Wilcher told Salter he cannot remember what Noblin said to make him angry.

Wilcher, according to the interview, stabbed Noblin one time. Noblin then broke free from Wilcher and began to run. Moore, Wilcher says, came around the car to confront him. "It was just too late to turn back then so I killed her right there," Wilcher said in the interview with Salter.

Wilcher said he then chased after Noblin, who by this time had escaped to a nearby intersection down the road from where the car was parked. "She got up the road and stopped and looked back. When she looked back, I was there," Wilcher told Salter in the interview. Wilcher said Noblin fought with him as he killed her. Wilcher said she tried to beat him away with her shoes.

THE MORNING AFTER

*According to later trial testimony, Wilcher was pulled over for speeding by then Forest Police Officer Henry Williams Jr. at 1:40 a.m. on Saturday, March 6, 1982. Wilcher tells Williams he was speeding because he cut himself and was trying to get to Lackey Hospital. Wilcher asks Williams to follow him to the hospital. Hospital personnel tell Wilcher that he has only a small cut and does not need medical attention.

Williams calls then-Forest Police Officer William Wilkerson to the hospital to help interview Wilcher. Williams reports that he noticed two purses on the seat of the car Wilcher was driving and that Wilcher's clothes are soaked in blood.

Wilcher shows the police officers the knife he used to kill Noblin and Moore but tell them that he cut himself with it while cleaning an opossum. Wilcher is released. According to his interview with Salter, Wilcher said the officers were called to another call and he left after that.

*Later that same morning, Wilcher is arrested by Forest police and charged

with larceny of a pistol.

*Authorities are alerted by the families of Moore and Noblin that the two

women are missing.

*That afternoon, 3 teenagers find the murdered bodies of Moore and Noblin.

They alert the authorities.

*On the afternoon of March 6, 1982, Wilcher is arrested by then Sheriff

Glenn Warren for the murders of Moore and Noblin. He is held without bail.

*On March 8, 1962, jewelry belonging to the slain women is discovered in

Wilcher's parents' home.

THE TRIALS

*In March, 1982, Circuit Judge Marcus Gordon calls a special session of circuit court to hear all matters before the court. This paves the way for Wilcher's trial. If the special session had not been called, it would have been November of that month before the trial would have taken place.

*On July 27, 1982, testimony begins in the trial for Wilcher's murder of Noblin. Wilcher has already plead not guilty.

Wilcher testifies on July 29, 1982, that he did not kill Noblin and that in fact a fourth person was in the car. He said a man by the name of Gene Milton killed the women while Wilcher was passed out in the backseat after drinking and taking drugs at the nightclub. Wilcher testifies he awoke to find Milton standing at the intersection over Noblin's body. Wilcher says he took the knife from Milton and then drives him to a gas station where he let Milton out.

When asked by prosecutors why he had never mentioned Milton prior to his testimony, Wilcher said he was scared of Milton seeking revenge on him. Wilcher later confesses in the Salter interview that Milton was not with him.

*On July 30, 1982, after just an hour of deliberation, a jury finds

Wilcher guilty of capital murder in the slaying of Noblin.

*On July 31, 1982, the jury sentences Wilcher to die by the death chamber.

*On Sept. 13, 1982, testimony begins in Harrison County in the trial

against Wilcher for Moore's murder. He is found guilty and sentenced to

death.

FIRST ROUND OF APPEALS

*Wilcher appealed his conviction to the Mississippi Supreme Court. On March 10, 1984, the Mississippi Supreme Court affirmed the conviction and an execution date of April 11, 1984, was set.

*On March 14, 1984, the state Supreme Court stayed Wilcher's execution to allow him an appeal before the U.S. Supreme Court.

*Barely a year later, on March 4, 1985, the nation's highest court refused to hear Wilcher's appeal, thus allowing the death sentence to stand.

*Wilcher's attorneys filed an appeal to the state Supreme Court on the grounds of ineffective counsel. The appeal was denied on Oct. 30, 1985.

VACATING THE SENTENCE AND RESENTENCING

*In October, 1993, the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals vacates the sentencing of Wilcher and 16 other death row inmates in Mississippi on technicalities of wording used by judges in instructions to jurors.

*On March 17, 1994, the Mississippi Supreme Court denies Wilcher a rehearing. This leads to his resentencing in June, 1994. In 2 separate trials, Wilcher is once again sentenced to death for the murders of Moore and Noblin.

*On Oct. 2, 2003, the state Supreme Court rules Wilcher is not warranted any more post-conviction appeals. Legal avenues still exist for Wilcher, meaning his execution could be 2 to 7 years away. (sources: Archives from The Scott County Times, Mississippi Attorney General's Office, Scott County Circuit Court records, Mississippi Attorney General's Office, Smith County Circuit Clerk's Office, Mississippi Department of Corrections, Rankin County Circuit Clerk's Office)

Wilcher v. State, 448 So.2d 927 (Miss. 1984) (Direct Appeal - Noblin Victim).

Defendant was convicted of capital murder in the Circuit Court, Scott County, Marcus D. Gordon, J., and was sentenced to death. Defendant appealed. The Supreme Court, Hawkins, J., held that: (1) confessions and certain tangible evidence resulting therefrom were properly admitted; (2) defendant's confession sustained submission of kidnapping issue to the jury, and evidence other than confession established corpus delicti of the statutory crime of kidnapping; (3) where objection to district attorney's reference to defendant as a “butcher” was properly sustained by circuit judge, there was no abuse of discretion in overruling motion for mistrial; and (4) in view of ambiguity of reference by defense counsel to arguments “that the Defendant is going to present,” trial judge would not be faulted for failing to interpret remarks by defense counsel as request that defendant personally argue his case. The Supreme Court, Prather, J., held that: (5) in sentencing phase, court properly sustained State's objection to defense counsel's description of conditions of gas chamber which counsel had personally viewed as a student; and (6) defense counsel's statement that a juror would have to sign death certificate, if taken literally, was inaccurate, and there was no error in trial judge's sustaining objection to such reference by defense counsel. Affirmed as to guilt and as to sentencing. Dan M. Lee and Robertson, JJ., specially concurred as to guilt phase. Hawkins, J., dissented and filed opinion as to sentence. Dan M. Lee and Robertson, JJ., specially concurred as to sentencing phase.

EN BANC.

Part I, HAWKINS, Justice, for the Court - GUILT PHASE

Bobby Glen Wilcher appeals from his conviction of the Capital Murder of Velma Odell Noblin and sentence of death. We affirm the guilt phase of the trial. We likewise affirm the sentencing phase. The numerous issues raised on this appeal are discussed in order.

FACTS

Two Scott County ladies were brutally murdered on a dead-end rural road in a remote area of Scott County. They were requested by Wilcher to drive him to his parents home from a honky-tonk in Scott County and after he got into the car with them he persuaded them to drive to this area in the pretext of carrying him home.

* * *

BACKGROUND Around 10:00 o'clock in the morning of Saturday, March 6, 1982, Bobby Easterling made an affidavit before Robert G. Wilkerson, a justice court judge of Scott County, charging that Bobby Wilcher did unlawfully “take and carry away 1-.38 cal. Colt with Guard over the Hammer”. Judge Wilkerson then issued a warrant for the arrest of Wilcher on a charge of “Larceny”, and delivered it to Mike Bennett, a deputy sheriff of that county. Bennett had other official duties at the time, and took the warrant to the sheriff's office, notifying the personnel there that “if anybody saw him, to pick him up”. No one else executed the warrant, and later in the day Bennett upon inquiry learned the location of the Gene Wilcher home, and went there and arrested Wilcher around 3:00 p.m. En route to the jail, Wilcher asked Bennett what “larceny was”, and Bennett told him he did not know. When Wilcher was brought to jail, Bennett handed him a copy of the warrant.

Almost simultaneously to their arrival at the jail, two girls and a boy came into the sheriff's office and reported seeing two bodies. Bennett took Wilcher to a cell and went to the location of the bodies.

It so happened in the early morning hours of that March 6, Bobby Wilcher was stopped for speeding by a police officer. He was driving a car belonging to one of the victims. The officer observed two (2) women's purses on the front seat and a black bra on the back seat. Wilcher told the officer that he was hurrying to the hospital for treatment of a cut finger and requested that the officer escort him. Wilcher was covered with blood. The officer followed but radioed another policeman to meet him at the hospital. Upon arrival at the emergency room at 2:00 a.m., Wilcher gave the officers a blood-covered knife. This knife was kept by the hospital security guard until turned over to police the evening of March 6. Wilcher's nicked thumb was treated with a band-aid and he was released. After receiving this information implicating Wilcher, Glen L. Warren, sheriff of that county, and Otis Kelly, a deputy, took Wilcher from the jail to the sheriff's office shortly after 7:00 p.m. that Saturday evening. Wilcher was given the conventional Miranda warnings, which were read to him on a form and signed by him at 7:19 p.m. Wilcher declined to make any statement at the time.

Wilcher requested to see his parents, and the officers took him to the Gene Wilcher home. They stood in another room while Wilcher talked with his parents a short while, and then returned with Wilcher to the sheriff's office. Wilcher was then presented with another Miranda warning which was read to him, and signed by him at 9:14 p.m. He then gave a statement which was written by Sheriff Warren and signed by Wilcher. This statement admitted killing both the victims with a knife.

The sheriff wanted to question him further shortly after 10:00 p.m. that evening. Another Miranda warning was given and Wilcher signed another standard form at 10:22 p.m., but declined to make any further statement. Wilcher was nineteen years of age, married with one child, and separated from his wife. He moved from Louisiana into the home of his parents in the latter part of February, 1982, and had been living there about a week and a half before March 5. The residence was under the control of the father, Gene Wilcher. No rent was charged Wilcher by his father, and he was provided a bedroom occupied only by himself. There was no lock on the bedroom door, however, and other than the fact that only Wilcher slept in the bedroom, there was nothing about the room setting it separate and apart from the Gene Wilcher household.

Gene Wilcher telephoned the sheriff's office on Monday, March 8, for permission to talk with his son. Otis Kelly answered the telephone and while they were waiting for a response to this request, a conversation was had between Kelly and Gene Wilcher. In that conversation it developed that in the house there was some tangible property of importance to the law enforcement officers.FN1

FN1. According to Gene Wilcher, when he telephoned the sheriff's office, Kelly asked him if he had found any jewelry in the house, and Wilcher replied that he had. Kelly then asked Wilcher to bring it to the sheriff's office, and Wilcher replied (according to him) that he wanted nothing to do with it, and for Kelly to come and get it.

According to Kelly, Gene Wilcher telephoned and told him that he needed to come out to the house, there was something Kelly needed to see. Upon the invitation of Gene Wilcher, Kelly and Albert Harkey, a constable of that county, went to the Gene Wilcher home. Gene Wilcher escorted them to the bedroom, pointed to a styrofoam container on the top of a chest-of-drawers, and said, “It's in here.” The officers took the container, and in it were a watch, two rings and a necklace belonging to the murdered victim Velma Odell Noblin. After retrieving this jewelry, Warren and Kelly again attempted to talk with Wilcher that evening in the sheriff's office. At 8:54 p.m. Wilcher was again read the standard Miranda form, which he signed, but he declined to give any further statement to the officers.

On Thursday following, March 11, Warren and Kelly questioned Wilcher again, and again he was given a standard Miranda form beforehand. Upon this occasion, however, the sheriff did not read the form aloud to Wilcher, but Wilcher read it himself and signed it. Following this, he accompanied the officers, and at Wilcher's direction, they drove several miles out into rural Scott County onto a county unpaved road. At a certain point Wilcher pointed to a certain location in a ditch, and the sheriff got out and picked up two purses and a brassiere.

On their way back to the jail, Wilcher again requested permission to visit his mother, and the sheriff took him by the Gene Wilcher home where he had a short visit with his mother. Upon their return to Forest, Wilcher gave a more detailed statement, written down by the sheriff and signed by Wilcher, in which he again admitted the savage murder of these two ladies in order to rob them. According to Wilcher's confession after the ladies consented to drive him home from a night spot in that county, he had tricked them into driving down an isolated road, presumably in search of the location of his father's home. In a remote spot he stabbed them both to death.

COMPETENCY OF CONFESSIONS

Over defense counsel's objection, both statements, as well as the two purses and the brassiere, were introduced into evidence as part of the state's case in chief. Upon this appeal the Defendant challenges the validity of the confessions, and the competency of the physical evidence, claiming his arrest was illegal, and that in obtaining the confessions the officers violated his Sixth Amendment right to counsel, and also that they were not free and voluntary, but resulted from coercion and promise of leniency.

The claim of illegal arrest arises from Miss.Code Ann. § 99-3-7, the pertinent part of which reads: Any law enforcement officer may arrest any person on a misdemeanor charge without having a warrant in his possession when a warrant is in fact outstanding for that person's arrest and the officer has knowledge through official channels that the warrant is outstanding for that person's arrest. In all such cases, the officer making the arrest must inform such person at the time of the arrest the object and cause therefor. If the person arrested so requests, the warrant shall be shown to him as soon as practicable. [Emphasis added] There was a sufficient compliance with the statute under the facts of this case when officer Bennett informed Wilcher he was being arrested for larceny, and gave him a copy of the warrant as soon as they reached the jail. See Boyd v. State, 406 So.2d 824 (Miss.1981); and Torrence v. State, 283 So.2d 595 (Miss.1973).

Wilcher does not contend there was no probable cause for his arrest on the charge of larceny, and the mere fact officer Bennett did not have all the information pertaining to the circumstances resulting in the issuance of the warrant at the time he apprehended Wilcher certainly does not vitiate the legality of his arrest. There is no statutory requirement for an arresting officer under the circumstances of this case to do more than Bennett did in effecting the arrest and subsequent thereto. In this day and age it would place an insuperable burden on arresting officers, when notified by responsible law enforcement agencies that a warrant is outstanding for a particular person, to require the arresting officer to also know the background and circumstances resulting in the warrant. There is no such constitutional or statutory requirement. This is not a case of a person being arrested on some vague suspicion, never told anything, and being held incommunicado for some period of time. Nor is this a case in which an officer either wilfully or through gross ineptitude failed to perform a duty of disclosing the reasons for the arrest.

Probable cause existing, and a lawful warrant having been issued, this Court is not going to adopt some strained view of whether an arresting officer has sufficiently disclosed the reason he is making the arrest when there has been absolutely no prejudice or harm done the accused, in any event. Finally, the arrest in this case was for an offense totally unrelated to the murder charge, as yet unreported when the arrest was made. To address the remaining contention of the invalidity of the evidence, it is necessary to set forth the various witnesses' versions of the circumstances prior to the officers' conduct. The circuit judge conducted a hearing out of the presence of the jury on the validity of the confessions. Officers Warren and Kelly testified the statements were made after complete Miranda warnings were given, there was no threat of any kind made, and no promise of reward or leniency was offered.

Wilcher testified he repeatedly made demand for an attorney, beginning with the first day when he was arrested. This was positively denied by Warren and Kelly. Bennett said he had no recollection of anything being said on the way to the jail except being questioned by Wilcher as to what larceny was, and he did not recall being asked anything about an attorney. Bennett arrested Wilcher upon the warrant for larceny, and had nothing to do with questioning him on the murder charge. Wilcher testified Kelly threatened him by making menacing gestures towards him, likewise specifically denied by Kelly and Warren.

Finally, Wilcher testified the sheriff told him if he would cooperate, he could see his family every Tuesday night. Officer Kelly did recall the sheriff telling Wilcher he could see his parents on Tuesday night if he would cooperate. Even if this remark were given the full import as argued by defense counsel, it hardly amounts to any promise of leniency. It is extremely difficult for us to perceive how such a limited promise could cause Wilcher to confess to such grave crimes, and indeed he makes no contention that he gave the statements as a result of this statement by the sheriff. See: Harrison v. State, 285 So.2d 889 (Miss.1973); Brister v. State, 211 Miss. 365, 51 So.2d 759 (1951). The sheriff's testimony puts the remark in an entirely different perspective. Warren testified Gene Wilcher came to see him following his son's indictment and after all questioning had been concluded, requested that he be permitted to see his son in private. After this conversation with the father, Sheriff Warren testified that on either that day or the day following he talked with Wilcher:

Well, I asked Bobby-I told Bobby that I would-if he would cooperate with me in jail, while he was up there in jail, and behave himself, that I would let him see his mother and daddy during the week at night for two or three weeks, so they could have some time to talk to each other in private, because on Sunday afternoon during visiting hours, and at that time our visiting hours were only one hour, and it was a large crowd of people always in the jail, and there was no place that they could have any privacy at all in the jail. The sheriff's version was not refuted by Gene Wilcher. It also negates the claim that the sheriff's offer to let Wilcher's parents see them privately on non-visiting nights had anything to do with an offer of leniency to secure a confession.

Following the hearing out of the presence of the jury, the trial court ruled the confessions and the tangible objects recovered in the ditch were admissible evidence. It is the function and duty of a trial judge to make a preliminary determination whether a confession was freely given by an accused, and this Court must respect his finding where the evidence is conflicting. See, Harrison v. State, 285 So.2d 889, p. 891 (1973). In this case the weight of the evidence strongly supports the ruling by the circuit judge that the confessions were voluntary and therefore competent evidence. The tangible objects recovered in the ditch as a result of Wilcher's confession were likewise admissible evidence.

* * *

DISTRICT ATTORNEY REFERRING TO DEFENDANT AS A “BUTCHER”

During the guilt phase of the trial, in closing the District Attorney argued: “Was he denied his rights? How can you treat a butcher any better than that?” (Vol. VIII, P. 1432) Objection to this remark was promptly sustained by the circuit judge, who then overruled the motion for a mistrial. Circuit judges are vested with discretion to determine whether a mistrial should be granted for an unnecessary inflammatory statement made by the prosecution in closing argument. We do not find any abuse of discretion in overruling the motion for a mistrial under the facts of this case. There were over twenty (20) wounds on the body of the victim. AFFIRMED AS TO GUILT PHASE. PATTERSON, C.J., WALKER and BROOM, P.JJ., BOWLING, DAN M. LEE, PRATHER and ROBERTSON, JJ., concur. DAN M. LEE and ROBERTSON, JJ., specially concur. ROY NOBLE LEE,FN3 J., not participating.

FN3. The homicide occurred in the home county of Justice Roy Noble Lee who is acquainted with the parties.

ON SENTENCE PHASE

PROPRIETY OF JURY INSTRUCTIONS

Error is assigned on the granting at the conclusion of the sentencing phase Instructions S-1, S-2 and S-5 to the state, and in refusing Instructions D-14, D-15 and D-16 requested by the Defendant.

Chapter 458, Laws 1977 Miss.Code Ann. § 97-3-21, in effect at the time of the commission of the crime and the trial, provides in pertinent part:

The Defendant's first complaint about Instruction S-1 and S-2 is that since the jury in the guilt phase of the trial had already determined beyond a reasonable doubt that he had murdered while committing the crimes of robbery and kidnapping, authorizing the same jury to again consider the same facts in the sentencing phase was placing him on trial twice for the same offense, and violated the double jeopardy proscription of the Fifth Amendment.FN4

* * *

CLOSING ARGUMENT IN THE SENTENCE PHASE

The facts of the first portion of this assignment can best be understood with a recital of the pertinent portion of the argument, as follows:

BY MR. SMITH: (Defense Counsel)

Six years ago when I was a senior in law school, I had a class trip. They carried us over to Parchman. Catch a bus in front of the law school about 7:00 o'clock in the morning, drive through the Delta, and you go over and visit the camps. You go in the front gate. We go through the camps, and one of the places they carried us was the maximum security camp and death row.

Now, we weren't allowed to go in and see the inmates on death row for security reasons, however, we were allowed to go around and view the gas chamber. I want to tell y'all about the gas chamber. (Emphasis added).

BY MR. HUNTER: (District Attorney)

I am going to object to Mr. Smith's argument about the gas chambers, Your Honor. It's not an issue in this case, and it is not in evidence.

BY THE COURT:

Do you propose to argue to the jury the conditions of the chamber you viewed there in Parchman?

BY MR. SMITH:

I beg your pardon?

BY THE COURT:

Do you propose to argue to the jury the details of the gas chamber you viewed there on your Parchman?

BY MR. SMITH:

Some of the details, Your Honor.

BY THE COURT:

Objection sustained.

The first objection sustained by the court dealt with testimony of the conditions of the gas chamber at Parchman which the attorney had personally viewed as a student. The court properly sustained the state's objection to such description as not being supported in the evidence.

The appellant relies upon Gray v. State, 351 So.2d 1342 (Miss.1977) as authority for the admission of facts judicially known to the court, but this reliance upon counsel's observations as a judicially known fact was misplaced. Counsel cannot state facts which are not in evidence, and which the court does not judicially know. Gray v. State, supra. A similar argument was advanced in Johnson v. State, 416 So.2d 383 (Miss.1982). This Court in Johnson stated:

Defense counsel should not be unduly restrained in his closing argument at the punishment stage because this stage of the trial is for the purpose of determining whether a defendant will live or die. We reaffirm our previous holdings that counsel may draw upon literature, history, science, religion and philosophy for material for his argument; however, we refrain from deciding whether argument is limited to mere facts in evidence adduced at this stage of the trial.

The scope of appellant's argument in the case sub judice clearly exceeded the legitimate field of closing argument···· (416 So.2d at 392).

We hold that this attempted argument exceeded the legitimate field of closing argument. The sustaining of the objection was not reversible error.

The defense argument continues:

BY MR. SMITH:

The State of Mississippi has placed a terrible burden on you people. A terrible burden. Right now, I want each of you to look down at your hands. Right now. This very minute. Each of you. Look down at your hands. Hold your hands open and look down at them, just like this (indicating). The State of Mississippi wants to put blood on those hands.

BY MR. SMITH:

I object to that statement, Your Honor, and ask that the jury be instructed to disregard it.

BY THE COURT:

I will not sustain your objection at this time. I will let him continue.

Of course, you will have the right to renew your objection. You may proceed.

BY MR. SMITH:

One of the Scriptures that I am familiar with involves the death of Jesus Christ. After Pontius Pilate condemned Jesus to die, he went out and washed his hands of the matter. He washed his hands. How much good do you think that handwashing did? How much good do you think Pilate received from washing his hands? Soap and water didn't cleanse that. It was symbolic, but there was no cleansing.

There is no way that you can ever get over what the State of Mississippi is asking you to do to this man here today. No way. The State of Mississippi is asking you to take a human life.

BY MR. HUNTER:

Object to that statement and ask that the jury be instructed to disregard it.

BY THE COURT:

Over-ruled.

BY MR. SMITH:

They have a man who is hired to come and execute the sentence, if you will, of the jury. This man is paid by the State of Mississippi to execute the sentence, and yet, I still don't think this man has the blood on his hands of another man. The burden is right here, right now. It is placed squarely on the shoulders of you people here in front of me. One of you is going to have to sign the verdict. One of you is going to have to sign his name to this man's death certificate. I don't know which one it is. (Emphasis added)

BY MR. HUNTER:

I object to that and ask the jury to be instructed to disregard it.

BY THE COURT:

I am going to let this jury be escorted to the jury room.

WHEREUPON, THE JURY WAS RETURNED FROM THE COURTROOM, AND THE FOLLOWING PROCEEDINGS WERE HAD OUT OF THE PRESENCE OF THE JURY:

BY THE COURT:

I am aware of my responsibility in this case. My responsibility is to rule fairly upon the evidence, to instruct the jury on the law to the very best of my ability. It is a position that I do not enjoy in a case of this type, to be called upon to rule on matters of fact and matters of law, when the ultimate decision could result in death.

I am also very mindful of the fact that at this stage of the trial of this case, that this Defendant is presenting a matter to the jury that based upon their decision, he could suffer death.

Therefore, the attorneys who argue the case, for a person charged with a crime such as this, is given more leeway to make that argument in the interest of his client.

In the trial of this case, as well as all cases, the State is entitled to a fair trial, as well as the Defendant. Under our law, if the State should make an error, of if this Court should make an error in its ruling, then there is a new trial, but the law also is that a Defendant can say and do anything under the sun, and there is no such thing as reversible error. He can walk up here and slap the Judge, shoot the Sheriff, run out the door, and there is no reversible error. Walk up there and spit in the face of the jury, and there is no reversible error.

But, still and all, we have rules of law, and one rule of law is that you cannot abuse the jurors.

I am ever mindful also, of a case that was recently decided by the Mississippi Supreme Court from your county, Leake County, that I tried. All Judges of the Supreme Court affirmed that conviction, except there was one dissenting Judge, who felt that in the argument of this stage of the trial, the attorneys could say anything that they wanted to.

However, I do not believe that it is in a sense of fairness to the people, and even of this Defendant, to accuse-which the law requires. The law requires whoever returns the death penalty, for someone to sign that verdict. We didn't write the law. The Legislature wrote the law, and it is a requirement. Someone has got to sign it. Someone has got to be designated, not by this Court, but chosen from among themselves, to sign that.

I certainly don't think it is fair to tell them they are signing a death certificate.

Therefore, I sustain that objection, and I am informing you not to say it again. You say it again, and you will suffer the wrath of this Court. (Emphasis added).

Now, bring in the jury.