Executed June 17, 2014 11:56 p.m. by Lethal Injection in Georgia

21st murderer executed in U.S. in 2014

1380th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Georgia in 2014

54th murderer executed in Georgia since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(21) |

Marcus A. Wellons B / M / 44 - 58 |

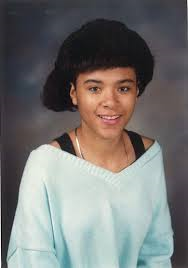

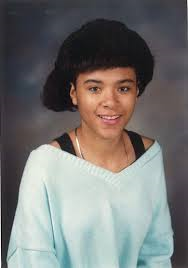

India Roberts B / F / 15 |

Citations:

Final/Special Meal:

Wellons declined to request a special last meal and instead was offered the institution’s meal tray, consisting of shepherd's pie, mashed potatoes, red beans, cabbage relish salad, corn bread, sugar cookies and fruit punch.

Final Words:

Wellons apologized to the family of his victim and said: "I ask and hope that you will find peace with my death." His final words were: "I'm going home to be with Jesus."

Internet Sources:

"Marcus Wellons executed," by Rhonda Cook and Bill Rankin. (June 17, 2014)

Georgia inmate Marcus Wellons was put to death late Tuesday for the 1989 rape and murder of a Cobb County teenager in the state’s first execution where the source of its lethal-injection drug was cloaked in secrecy.

Wellons’ execution received heightened scrutiny because it was the first one in the country to be carried out since a botched execution occurred in Oklahoma seven weeks ago. That incident ratcheted up the debate over the lethal-injection process and the use of made-to-order drugs produced by undisclosed compounding pharmacies. Even a federal appeals court judge who declined to halt the execution Tuesday cited what happened in Oklahoma as a reason why Georgia should not have a lethal-injection secrecy law.

Wellons, 58, was pronounced dead at 11:56 p.m. after his final appeals were denied by the U.S. Supreme Court. Wellons apologized to the family of India Roberts the teenager he was convicted of killing and said, “I ask and hope they will find peace in my death.” He thanked his family and friends for their love and prayers and added, “I’m going home to be with Jesus.” Wellons hummed as prayer was being said and as the warden read the death warrant. Otherwise there was little movement visible as he lay on the gurney. He was seen to exhale a couple of times before his body seemed to quiver and then there was no more movement. Three minutes before Wellons was declared dead a nurse standing to his left was seen asking one of the corrections officers if he was ok, just before the officer fainted.

In 1993, a Cobb County jury sentenced Wellons to death for the rape and murder of 15-year-old India Roberts in the Vinings townhouse of Wellons’ girlfriend. Wellons was supposed to be moving out of the townhouse when he abducted India as she was walking to her school bus stop the morning of Aug. 31, 1989. She was believed to have been strangled with a telephone cord. Wellons’ trial became a focus of national attention in 2010 when the U.S. Supreme Court ordered a hearing because one of Wellons’ jurors gave a penis-shaped chocolate to the judge and another juror gave breast-shaped chocolates to the courthouse bailiff shortly after the verdict. After a review, the federal appeals court said that while the gifts were “tasteless and inappropriate,” Wellons did not deserve a new trial because they played no part in the jury’s deliberations.

This week, Wellons’ case was in the spotlight again because he was to become the first Georgia inmate put to death with a compounded sedative made specifically for his execution. A state law passed last year shields the public — and even the courts — from knowing the identity of the compounding pharmacy, the qualifications of the execution team and details about the lethal-injection drug, pentobarbital. Wellons’ execution was set just days after the state Supreme Court rejected a challenge to the secrecy law in a 5-2 decision issued last month. Wellons’ attorneys had argued that the recently botched execution in Oklahoma and the lack of oversight of compounding pharmacies presented real risks that Wellons could suffer significant pain during his execution.

On April 29, condemned Oklahoma inmate Clayton Derrell Lockett writhed, gasped and struggled to lift his head after he had been declared unconscious on the lethal-injection gurney. Prison officials tried to stop the execution, but Lockett died of a massive heart attack. A preliminary report released last week concluded that the IV line that was supposed to deliver the drugs had been improperly placed. The doctor who did the autopsy has asked for additional information to complete his report but was denied because of Oklahoma’s secrecy law regarding lethal injections.

Georgia has argued that it needs to protect the identities of lethal-injection drug providers to ensure the Department of Corrections can carry out executions. Public pressure has led pharmaceutical companies worldwide to refuse to sell such drugs to states for executions. Georgia initially used a three-drug cocktail but it had to change its protocols to using only one — a massive dose of pentobarbital, a sedative also used to euthanize animals. The state then had to make another change, turning to a compounding pharmacy, when it was still unable to obtain the drug.

On Tuesday, a three-judge panel of the federal appeals court in Atlanta unanimously declined to stop Wellons’ execution. The court said Wellons failed to clear a legal threshold by showing that the lethal-injection protocol to be used in his execution created a “demonstrated risk of severe pain that is substantial when compared to the known alternatives.” But Judge Charles Wilson, writing separately, expressed concern over the state’s secrecy law. How could Wellons, the judge asked, show that he faced a risk of needless pain and suffering “when the state has passed a law prohibiting him from learning about the compound it plans to use to execute him?”

Wilson questioned the need to keep information about the lethal-injection process concealed from the public and the courts, “especially given the recent much-publicized botched execution in Oklahoma.” “Unless judges have information about the specific nature of a method of execution,” Wilson wrote, “we cannot fulfill our constitutional role of determining whether a state’s method of execution violates the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment before it becomes too late.”

"I'm going home to be with Jesus: Last words of killer who raped and murdered 15-year-old as he becomes the first US execution since botched lethal injection; Georgia inmate Marcus Wellons the first execution since April," by Snejana Farberov. (AP June 18, 2014)

A Georgia inmate who raped and murdered a 15-year-old girl in 1989 became the first person on death row to be executed since the botched lethal injection of Oklahoma killer Clayton Lockett in late April. Marcus Wellons, 59, received a lethal injection late Tuesday in Jackson, Georgia, after last-minute appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court were denied. A prison guard fainting shortly before he was pronounced dead at 11:56 p.m, more than an hour after the procedure began.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, which witnessed the execution, said Mr Wellons apologized for the 1989 rape and murder of his 15-year-old neighbor India Roberts in suburban Atlanta. Wellons reportedly apologized to the family of his victim and said: 'I ask and hope that you will find peace with my death'. His final words were: 'I'm going home to be with Jesus.'

The Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles on Monday denied clemency to Wellons, leaving his fate in the hands of the courts. Only five minutes after Wellons was pronounced dead, Missouri authorities commenced the lethal injection of John E. Winfield at 12.01am. He was pronounced dead at 12.10am. Winfield, 46, was put to death for shooting three St. Louis County women in the head in 1996, killing two.

Wellons was served Shepherd's Pie, mashed potatoes and red beans as a final meal although it was unclear if he ate it, according to Death Penalty Info. The same feed also said that Winfield declined to have a final meal. The executions were the first since the botched April 29 in Oklahoma raised new concerns about lethal injection.

Nine executions nationwide have been stayed or postponed since late April, when Oklahoma prison officials halted the execution of Clayton Lockett after noting that the lethal injection drugs weren't being administered into his vein properly. Lockett's punishment was halted and he died of a heart attack several minutes later. 'I think after Clayton Lockett's execution everyone is going to be watching very closely,' Fordham University School of Law professor Deborah Denno, a death penalty expert, said of this week's executions. 'The scrutiny is going to be even closer.'

Marcus Wellons' execution in Georgia was scheduled for 7pm, but was delayed pending the outcome of a U.S. Supreme Court appeal. Just before 11pm Eastern Time, the decision came down from the justices refusing to grant Wellons, 59, a last-minute reprieve, clearing the way for his execution an hour later. Georgia and Missouri both use the single drug pentobarbital, a sedative. Florida uses a three-drug combination of midazolam hydrochloride, vecuronium bromide and potassium chloride. Despite concerns about the drugs and how they are obtained, death penalty supporters say all three convicted killers are getting what they deserve.

Wellons was convicted in the 1989 rape and murder of India Roberts, his 15-year-old neighbor in suburban Atlanta. Soon after the girl left for school, another neighbor heard muffled screams from the apartment where Wellons was living. Later that day, a man told police he saw a man carrying what appeared to be a body in a sheet. Police found the girl's body in a wooded area. She had been strangled and raped.

Wellons was the first Georgia inmate executed since February 2013 and just the second since 2011.

Georgia Department of Corrections

Inmate: Marcus A. Wellons

Forsyth - The Cobb County Superior Court has ordered the execution of convicted murderer Marcus A. Wellons. The court ordered the Georgia Department of Corrections to carry out the execution June 17-24. Commissioner Brian Owens has set the date for Tuesday, June 17, 2014 at the Georgia Diagnostic & Classification Prison in Jackson at 7pm.

Wellons was sentenced to death for the August 1989 murder of 15-year-old India Roberts in Cobb County. If executed, Wellons will be the 31st inmate put to death by lethal injection.

Media interested in a picture of Wellons and a listing of his crimes may go to the GDC website (www.dcor.state.ga.us).

The GDC has one of the largest prison systems in the U.S. and is responsible for supervising nearly 55,000 state prisoners and over 160,000 probationers. It is the largest law enforcement agency in the state with approximately 12,000 employees. For more information on the GDC call 478-992-5247 or visit http://www.dcor.state.ga.us.

Wellons Execution Media Advisory - Inmate’s Last Meal

Forsyth - Condemned murderer Marcus Wellons is scheduled for execution by lethal injection at 7:00 p.m. on Tuesday, June 17, 2014, at Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Prison in Jackson. Wellons was sentenced to death in the 1989 murder of 15 year-old India Roberts in Cobb County.

Media witnesses for the execution are: Kate Brumback, The Associated Press; Jon Gillooly, The Marietta Daily Journal; Rhonda Cook, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution; Scott Kimbler, WYAY-FM – News Radio 106.7; and Adam Ragusea, Georgia Public Broadcasting.

Wellons declined to request a special last meal and instead will be offered the institution’s meal tray, consisting of shepherd's pie, mashed potatoes, red beans, cabbage relish salad, corn bread, sugar cookies and fruit punch.

There have been 53 men executed in Georgia since the U.S. Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty in 1973. If executed, Wellons will be the 31st inmate put to death by lethal injection. There are presently 91 men and one woman on death row in Georgia.

The Georgia Diagnostic & Classification Prison is located 45 minutes south of Atlanta off Interstate 75. From Atlanta, take exit 201 (Ga. Hwy. 36), turn left over the bridge and go approximately ¼ mile. The entrance to the prison is on the left. Media covering the execution will be allowed into the prison’s media staging area beginning at 5:00 p.m. on Tuesday.

PRESS ADVISORY

Execution Date Set for Marcus A. Wellons, Convicted of Raping and Murdering Cobb County Girl

Georgia Attorney General Sam Olens offers the following information in the case against Marcus A. Wellons, who is currently scheduled to be executed on June 17, 2014, at 7:00 p.m. for the rape and murder of 15 year old India Roberts.

Scheduled Execution

On May 28, 2014, the Superior Court of Cobb County filed an order setting the seven-day window in which the execution of Marcus A. Wellons may occur to begin at noon, June 17, 2014 and ending seven days later at noon on June 24, 2014. Wellons has concluded his direct appeal proceedings and his state and federal habeas corpus proceedings.

Wellons’ Crime (1989)

The Georgia Supreme Court summarized the facts of the case as follows: Throughout the summer of 1989, Wellons lived with his girlfriend, Gail Saunders, in her townhouse apartment in Cobb County. Early that summer, Saunders' 14-year-old son Tony also lived in the apartment. Tony and the victim [India Roberts], who lived in a neighboring apartment with her mother, were friends. The victim occasionally visited Tony inside Saunders' apartment, where the two youths would watch television or play Nintendo. Wellons encouraged Tony to date the victim, remarking several times that she was a good looking girl. At some point during the summer, Tony moved to Chattanooga to live with his grandparents. The victim continued to spend time with Saunders occasionally. Saunders described herself as the victim's "play mommy" with whom the victim shared confidences.

Wellons and Saunders had become acquainted at the hospital where both worked, Wellons as a counselor in the psychiatric ward. Wellons moved in with Saunders on the pretense that he owned a home but was unable to occupy it, because an ex-girlfriend had moved there with her two young daughters, and he could not in good conscience turn them out. Over the summer Wellons proposed marriage to Saunders. However, by then Saunders had become wary of Wellons, who was increasingly hostile and abusive. She verbally accepted his proposal out of fear, all the while seeking an escape from her predicament.

On the evening of August 30, 1989, Saunders told Wellons that their relationship was over and that he must move out of her apartment. Wellons, who had recently been fired from his job, purchased a one-way ticket to Miami for a flight departing on the evening of August 31. Fearing to be alone with Wellons the night before his departure, Saunders told Wellons that she was going to Chattanooga to spend the night with her parents and enroll Tony in school. Instead, Saunders went to the home of a female friend.

That evening, Wellons began making desperate attempts to reach Saunders by telephone. He called her mother in Chattanooga repeatedly, only to be told that Saunders had not arrived. Wellons then called Saunders' friends, but no one knew or revealed her whereabouts. He called his mother and told her he suspected that Saunders was with another man. Wellons became increasingly angry and began drinking. He ransacked Saunders' apartment. He overturned potted plants and furniture, threw flour onto the floor, and poured bleach over all of Saunders' clothes, carefully sparing his and Tony's belongings in the process. After the apartment was demolished, Wellons began attempts to cover up his deed. He broke a window, from the inside out, cutting his hand in the process and smearing blood around the apartment. He stacked electronic equipment by the door. He then called 911 at approximately 3:00 a.m. on August 31 to report a burglary. When a police officer arrived, Wellons told the officer that he had come home to find the apartment ransacked, although no items were missing. Wellons explained to the officer that he cut his hand while struggling to uncover a stash of money to determine if it had been taken. Sometime after the officer left, Wellons wrote a racial slur across the wall in Saunders' bedroom.

Several hours later, at approximately 8:00 a.m., the victim said goodbye to her mother and walked from her apartment, past Saunders' door, toward the school bus stop. Shortly thereafter, Saunders' next door neighbor heard muffled screams from inside Saunders' apartment.

The apartment building was close to a wooded area, beyond which was a grocery store. At approximately 2:00 p.m., Wellons approached an acquaintance who was employed at the grocery store and asked to borrow a car. The acquaintance refused. Wellons told the acquaintance that when he (Wellons) returned home the previous night, he encountered two white men who were burglarizing the apartment. Wellons said that he successfully fought off the intruders but explained that he had in the process sustained the injuries to his hand.

About half an hour later, Theodore Cole, a retired military police officer, was driving near the wooded area behind the apartment complex. He spotted in the distance a person carrying what appeared to be a body wrapped in a sheet. He distinctly saw feet dangling from the bottom of the sheet. Cole drove on but then returned for a second look. He drove around in the parking lot of the apartment complex and saw nothing. As he was driving away, however, he saw a man in his rear view mirror walk along the road and throw a sheet into the woods. Cole drove directly to the grocery store, where he called 911. Police officers arrived quickly and began a search of the woods.

The police first discovered sheets, clothing and notebooks bearing Tony's name. Then, upon close inspection of a pile of tree branches near where he had seen the man carrying the sheet, Cole spotted the body of India Roberts. When the branches were removed, the officers discovered that the victim was completely unclothed, with cuts on one side of her face and ear and bruises on her neck.

During the search of the woods, Cole spotted a black man with a bundle under his arm near the apartment building and identified him as the man Cole had seen carrying the sheet. Cole and an officer chased the man, but as they approached the building, the man turned the corner and Cole and the officer heard a door shut. The officer learned from a passerby which apartment was occupied by a man fitting the description given by Cole. He knocked on Saunders' door and announced his presence, but there was no answer. He returned to join the other officers, who were investigating the scene in full force, with helicopters overhead.

Wellons, now trapped inside Saunders' apartment with residual evidence of his crime, gave up his attempt to dispose of the evidence in the woods. He first tried to clean the apartment and his clothes. He then abandoned that project, changed into swim wear, grabbed an old, yellowed newspaper and a cup of wine, partially barricaded and locked the door, and headed for the pool. On his way, Wellons caught sight of a police officer and stopped abruptly. The officer began questioning him. Initially evasive, Wellons did ultimately tell officers that the injuries to his hand, and new scratches to his face, were sustained during a scuffle with two men whom he had caught burglarizing Saunders' apartment.

While investigating the scene, officers had asked Cole whether either of two black males was the man Cole had seen carrying the sheet. Cole immediately ruled out each of the men. Then, while officers were questioning Wellons, one officer standing at a distance from the questioning asked Cole whether Wellons was the man he had seen. Cole said that although Wellons was wearing different clothing from the man he had seen carrying the sheet, and whom he had again seen near the complex, Cole was 75 to 80 percent certain that Wellons was the same man.

Later that day, officers searched Saunders' apartment. Inside, they found numerous items of evidence including the victim's notebooks and earrings. In Tony's room, they discovered the victim's panties. They also found blood on Tony's mattress and box springs. The mattress had been flipped so that the bloody portion was facing downward, and the bed had been remade.

The autopsy revealed that the victim died from manual strangulation, which in itself would have taken several minutes. The autopsy also showed that Wellons had attempted to strangle the victim with a ligature, possibly a telephone cord, and that he had bruised her and cut her face and ear with a sharp object. The evidence suggested that Wellons had dragged or otherwise forcibly moved the victim from the kitchen up the stairs to Tony's bedroom. Finally, the autopsy revealed a vaginal tear and copious amounts of what appeared to be seminal fluid within the victim's vagina. She had defensive wounds to her hands, and her blouse was stained with her own blood. Wellons v. State, 266 Ga. at 78-81 (1995).

The Trial (1990-1993)

Wellons was indicted in the Superior Court of Cobb County, Georgia on April 5, 1990, for the rape and murder of India Roberts. On June 5, 1993, a jury found Wellons guilty of rape and murder. The jury’s recommendation of a death sentence was returned on June 8, 1993.

The Direct Appeal (1995-1996)

The Georgia Supreme Court affirmed Wellons’ convictions and sentences on November 20, 1995. Wellons v. State, 266 Ga. 77 (1995). The United States Supreme Court denied Wellons’ request to appeal on October 7, 1996. Wellons v. Georgia, 519 U.S. 830 (1996).

State Habeas Corpus Proceedings (1997-2001)

Wellons, represented by Michael McIntyre and Carol Michel, filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus in the Superior Court of Butts County, Georgia on May 27, 1997. An evidentiary hearing was held on February 4, 1998. On July 20, 1998, the state habeas corpus court entered an order denying Wellons state habeas relief. The Georgia Supreme Court denied Wellons’ appeal. The United States Supreme Court denied Wellons’ request to appeal on October 29, 2001. Wellons v. Turpin, 534 U.S. 1001 (2001).

Federal Habeas Corpus Proceedings (2001-2007)

Wellons, represented by attorneys from the Federal Defender Program, Inc., filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Georgia on May 18, 2001. Wellons filed amendments to his petition for writ of habeas corpus on September 30, 2002 and March 19, 2004. On February 20, 2007, the district court denied Wellons federal habeas corpus relief.

11th Circuit Court of Appeals (2008-2009)

Wellons’ case was appealed to the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals in 2008. The case was orally argued before the Eleventh Circuit on July 11, 2008. On January 5, 2009, the Eleventh Circuit denied relief. Wellons v. Hall, 554 F.3d 923 (11th Cir. 2009).

United States Supreme Court (2009-2010)

Wellons requested to appeal to the United States Supreme Court on July 31, 2009. On January 19, 2010, the United States Supreme Court granted Wellons’ petition for writ of certiorari, vacated the judgment of the appellate court and remanded the case to the Eleventh Circuit for further consideration regarding a claim of alleged juror misconduct.

Remand Proceedings (2010-2013)

On April 19, 2010, the Eleventh Circuit remanded the case to the federal district court for further proceedings. Wellons was allowed to conduct extensive discovery on the claim of juror misconduct. Thereafter, the federal district court denied Wellons’ claim of juror misconduct on August 5, 2011. Wellons appealed to the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals in January of 2012. On September 19, 2012, the Eleventh Circuit denied relief. Wellons v. Warden, GDCP, 695 F.3d 1202 (11th Cir. 2012).

United States Supreme Court (2013)

Wellons requested to appeal to the United States Supreme Court, which was denied October 7, 2013. Wellons v. Humphrey, 134 S.Ct. 177 (2013).

"Man who raped, killed teen executed," by Kate Brumback. (Associated Press Wednesday, June 18, 2014 5:09am)

JACKSON, Ga. — In the first lethal injection since a botched execution in Oklahoma nearly two months ago, a Georgia death row inmate convicted in 1993 of raping and murdering his 15-year-old neighbor was executed just before midnight Tuesday. Marcus Wellons, 59, was executed by injection after several last-minute appeals were denied. He was pronounced dead shortly before midnight. The execution seemed to go smoothly with no noticeable complications . . . .

"Georgia inmate put to death, first since Oklahoma's botched execution," by David Beasley. (Wed Jun 18, 2014 1:25am EDT)

ATLANTA (Reuters) - A man convicted of the 1989 rape and strangulation of a teenage girl in Georgia was executed on Tuesday, the first U.S. inmate to be put to death since a botched lethal injection in Oklahoma in April renewed a national debate over capital punishment.

Marcus Wellons, 58, was executed by lethal injection at a prison inmate intake facility that also houses Georgia's death row and was pronounced dead at 11:56 pm local time, shortly after the U.S. Supreme Court denied his 11th-hour bid for a reprieve.

State corrections spokeswoman Gwendolyn Hogan said Wellons' execution went smoothly, without complications. She said he issued a statement of apology and recited a brief prayer before he was put to death.

Two more inmates were slated for execution elsewhere in the United States on Wednesday, one each in Missouri and Florida. On Tuesday, the Supreme Court cleared the way for the Missouri execution to proceed as scheduled, rejecting a request for a stay by convicted double-murderer John Winfield, 43.

Wellons was the first inmate put to death since condemned Oklahoma killer and rapist Clayton Lockett died on April 29, suffering an apparent heart attack about 30 minutes after prison officials there had halted his execution because of problems in administering the lethal injection.

The case reignited national scrutiny of the death penalty, and even the White House criticized the botched execution as failing to adhere to humane standards.

Wellons was convicted of killing his 15-year-old neighbor, India Roberts, whom he abducted as she was walking to a school bus stop.

In his appeal to the Supreme Court, Wellons' attorneys cited the Oklahoma case to bolster their argument that Georgia had not provided enough detail about the state's execution protocol. However, the high court denied three separate applications for a stay of execution without comment.

On Monday, the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles turned down the inmate's request for clemency. Wellons became the 21st person executed in the United States this year, according to Richard Dieter, executive director of the non-profit Death Penalty Information Center.

He also was the first inmate executed in Georgia since the state's Supreme Court upheld a new law in May shielding the identity and methods of compounding pharmacies that formulate lethal injection drugs.

Wellons and Gail had become acquainted at the hospital where both worked, Wellons as a counselor in the psychiatric ward. Wellons moved in with Gail on the pretense that he owned a home but was unable to occupy it, because an ex-girlfriend had moved there with her two young daughters, and he could not in good conscience turn them out. Over the summer Wellons proposed marriage to Gail. However, by then Gail had become wary of Wellons, who was increasingly hostile and abusive. She verbally accepted his proposal out of fear, all the while seeking an escape from her predicament.

On the evening of August 30, 1989, Gail told Wellons that their relationship was over and that he must move out of her apartment. Wellons, who had recently been fired from his job, purchased a one-way ticket to Miami for a flight departing on the evening of August 31. Fearing to be alone with Wellons the night before his departure, Gail told Wellons that she was going to Chattanooga to spend the night with her parents and enroll Tony in school. Instead, Gail went to the home of a female friend.

That evening, Wellons began making desperate attempts to reach Gail by telephone. He called her mother in Chattanooga repeatedly, only to be told that Gail had not arrived. Wellons then called Gail's friends, but no one knew or revealed her whereabouts. He called his mother and told her he suspected that Gail was with another man. Wellons became increasingly angry and began drinking. He ransacked Gail's apartment. He overturned potted plants and furniture, threw flour onto the floor, and poured bleach over all of her clothes, carefully sparing his and Tony's belongings in the process. After the apartment was demolished, Wellons began attempts to cover up his deed. He broke a window, from the inside out, cutting his hand in the process and smearing blood around the apartment. He stacked electronic equipment by the door. He then called 911 at approximately 3:00 a.m. on August 31 to report a burglary. When a police officer arrived, Wellons told the officer that he had come home to find the apartment ransacked, although no items were missing. Wellons explained to the officer that he cut his hand while struggling to uncover a stash of money to determine if it had been taken. Sometime after the officer left, Wellons wrote a racial slur across the wall in Gail's bedroom.

Several hours later, at approximately 8:00 a.m., India said goodbye to her mother and walked from her apartment, past Gail's door, toward the school bus stop. Shortly thereafter, Gail's next door neighbor heard muffled screams from inside Gail's apartment. The apartment building was close to a wooded area, beyond which was a grocery store. At approximately 2:00 p.m., Wellons approached an acquaintance who was employed at the grocery store and asked to borrow a car. The acquaintance refused. Wellons told the acquaintance that when he (Wellons) returned home the previous night, he encountered two white men who were burglarizing the apartment. Wellons said that he successfully fought off the intruders but explained that he had in the process sustained the injuries to his hand.

About half an hour later, Theodore Cole, a retired military police officer, was driving near the wooded area behind the apartment complex. He spotted in the distance a person carrying what appeared to be a body wrapped in a sheet. He distinctly saw feet dangling from the bottom of the sheet. Cole drove on but then returned for a second look. He drove around in the parking lot of the apartment complex and saw nothing. As he was driving away, however, he saw a man in his rear view mirror walk along the road and throw a sheet into the woods. Cole drove directly to the grocery store, where he called 911. Police officers arrived quickly and began a search of the woods. The police first discovered sheets, clothing and notebooks bearing Tony's name. Then, upon close inspection of a pile of tree branches near where he had seen the man carrying the sheet, Cole spotted the body of India Roberts. When the branches were removed, the officers discovered that the victim completely unclothed, with cuts on one side of her face and ear and bruises on her neck.

During the search of the woods, Cole spotted a black man with a bundle under his arm near the apartment building and identified him as the man Cole had seen carrying the sheet. Cole and an officer chased the man, but as they approached the building, the man turned the corner and Cole and the officer heard a door shut. The officer learned from a passerby which apartment was occupied by a man fitting the description given by Cole. He knocked on Gail's door and announced his presence, but there was no answer. He returned to join the other officers, who were investigating the scene in full force, with helicopters overhead. Wellons, now trapped inside Gail Saunders' apartment with residual evidence of his crime, gave up his attempt to dispose of the evidence in the woods. He first tried to clean the apartment and his clothes. He then abandoned that project, changed into swim wear, grabbed an old, yellowed newspaper and a cup of wine, partially barricaded and locked the door, and headed for the pool. On his way, Wellons caught sight of a police officer and stopped abruptly. The officer began questioning him. Initially evasive, Wellons did ultimately tell officers that the injuries to his hand, and new scratches to his face, were sustained during a scuffle with two men whom he had caught burglarizing Gail's apartment.

While investigating the scene, officers had asked Cole whether either of two black males was the man Cole had seen carrying the sheet. Cole immediately ruled out each of the men. Then, while officers were questioning Wellons, one officer standing at a distance from the questioning asked Cole whether Wellons was the man he had seen. Cole said that although Wellons was wearing different clothing from the man he had seen carrying the sheet, and whom he had again seen near the complex, Cole was 75 to 80 percent certain that Wellons was the same man.

Later that day, officers searched Gail's apartment. Inside, they found numerous items of evidence including India's notebooks and earrings. In Tony's room, they discovered India's panties. They also found blood on Tony's mattress and box springs. The mattress had been flipped so that the bloody portion was facing downward, and the bed had been remade. The autopsy revealed that India Roberts had died from manual strangulation, which in itself would have taken several minutes. The autopsy also showed that Wellons had attempted to strangle India with a ligature, possibly a telephone cord, and that he had bruised her and cut her face and ear with a sharp object. The evidence suggested that Wellons had dragged or otherwise forcibly moved India from the kitchen up the stairs to Tony's bedroom. Finally, the autopsy revealed a vaginal tear and copious amounts of what appeared to be seminal fluid within the victim's vagina. She had defensive wounds to her hands, and her blouse was stained with her own blood. Although a not guilty plea was entered for Wellons, he did not dispute his participation in the crimes. Instead, he urged the jury to return a verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity or guilty but mentally ill.

UPDATE: After several hours of delays while appeals were considered and rejected by the US Supreme Court, Marcus Wellons was executed by lethal injection. Wellons apologized for his crime. “I ask and hope that you will find peace with my death. I’m going home to be with Jesus.”

Georgians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty

Jack Edward Alderman, 45, was sentenced to death in June 1975 by a Chatham County jury for killing his wife, Barbara Jean Alderman, 27, on Sept. 21, 1974. His sentence was overturned on a federal appeal in 1980, but in April 1984, he was again sentenced to death. A co-defendant, John Arthur Brown, pleaded guilty for a life sentence and told investigators Mr. Alderman wanted to kill his wife for the insurance money. Mr. Brown was paroled in 1987. The state appeal concerning the fairness of Mr. Alderman's second trial has been pending in Mr. Alderman's case since December 1994.

Stanley Edward Allen, 42, was sentenced to death in Elbert County in July 1981. Mr. Allen and an accomplice, Woodrow Davis, 18, were convicted in the Jan. 5, 1981, break-in of the home of Susie C. Rucker, 72. Both men raped the woman, and she was strangled to death. Mr. Davis was sentenced to life in prison. Mr. Allen's death sentence was overturned by the Georgia Supreme Court in January 1982, but he was resentenced to death in October 1984. Mr. Allen had previously been sentenced to 10 years in prison for rape in 1975. Since September 1991, Mr. Allen has been awaiting a new sentencing trial on the issue of mental retardation.

James Douglas Andrews, 28, was sentenced to death on Oct. 16, 1992, in Muscogee County for rape, robbery and murder. Investigators say that on July 23, 1990, he broke into the home of Viola Hick, 78. His first appeal to the state Supreme Court hasn't been filed.

Joseph Martin Barnes, 27, was sentenced to death in Newton County in June 1993 for the robbery and shooting death of Prestiss Lamar Wells, 57, on Feb. 13, 1992. Although Mr. Barnes was sentenced to death four years ago, his first appeal hasn't been filed yet.

Norman Darnell Baxter, 45, was sentenced to death in Henry County in November 1983 for the murder of Kathryn June "June Bug" Brooks, 22. Her nude body bound feet, wrists and neck was found a week after she was reported missing in July 1980. Mr. Baxter, who spent time in state mental hospitals, had prior criminal convictions. A new sentencing trial has been pending since February 1995.

Jack Alfred Bennett, 68, was sentenced to death in Douglas County for killing his 55-year-old wife four days after they were married on June 24, 1989. As she lay sleeping, Mr. Bennett stabbed her more than 100 times and caved in the left side of her head with a claw hammer. His state appeal challenging the fairness of his trial has been pending since December 1995.

Billy Sunday Birt, 60, and Bobby Gene Gaddis, 56, were sentenced to death in Jefferson County for the Dec. 22, 1973, torture and killing of Lois and Reed Oliver Fleming, ages 72 and 75. Three other men, including the man who arranged the robbery-killings, were granted immunity. A third man, Charles Reed, was sentenced to life in prison. Four years after Mr. Birt and Mr. Gaddis were sentenced to death for killing the white couple, their sentences were overturned by a state judge reviewing the fairness of their trials. Nothing has been done since and this year the Department of Corrections moved Mr. Birt and Mr. Gaddis off death row.

Joshua Daniel Bishop, 22, was sentenced to death in Baldwin County on Feb. 13, 1996, for the robbery and beating death of Leverett Lewis Morrison, 44, who refused to turn over his jeep keys. Mr. Bishop helped beat to death another man and that evidence was used against him in his capital murder trial. His first appeal is pending.

Roy Willard Blankenship, 41, was sentenced to death in April 1980 in Chatham County for beating, raping and killing Sara Bowen, 78, for whom he had done work in the past. Ms. Bowen actually died from a heart attack brought on by trauma including being bitten, scratched and stomped. Mr. Blankenship has been sentenced to death three times, the last time in June 1986, following the reversal of his sentence. A state appeal challenging the fairness of his trial has been pending since March 1994.

Kenneth Dan Bright, 36, was sentenced to death in Muscogee County for the Oct. 30, 1989, robbery and murder of his grandparents, R.C. Mitchell, 74, and Fannie Monroe Mitchell, 69, less than eight months after being released from a mental hospital. Mr. Bright was a crack addict on parole at the time of the killings. His sentence was overturned by the state Supreme Court in March 1995. He's still awaiting retrial.

Ward Anthony Brockman, 25, was sentenced to death March 12, 1994. He and three others killed a service station attendant during an attempted robbery on June 27, 1990. Mr. Brockman, who was the triggerman, and his accomplices had pulled a number of armed robberies, and he was arrested after a chase in Phenix City, Ala. His first appeal to the state Supreme Court hasn't been filed yet.

James Willie Brown, 48, was sentenced to death in Gwinnett County in July 1981 after he had been hospitalized for nearly six years. Mr. Brown, who had a history of mental illness and convictions for an attempted rape and robbery, killed Brenda Sue Watson, 19, on May 12, 1975, after the two went out for dinner and dancing. A federal court reversed Mr. Brown's death sentence in 1988. He was sentenced to death a second time in February 1990.

Raymond Burgess, 38, was sentenced to death on Feb. 25, 1992, in Douglas County. During a robbery spree with co-defendant Norris Young. Mr. Burgess shot and killed Liston Chunn, 44, eight months after he was paroled from a life sentence for another robbery-killing. Mr. Burgess was also convicted in 1977 of armed robbery and sexual assault. Mr. Young was sentenced to life in prison. Mr. Burgess' state appeal challenging the fairness of his trial has been pending since August 1995.

David Loomis Cargill, 38, was sentenced to death in Muscogee County in July 1985 for the robbery and murder of a couple with four children under age 10. Cheryl Williams, 29, and Danny Williams, 41, were at a service station when Mr. Cargill and his brother, Tommy, robbed it the night of Jan. 22, 1985. The couple was forced to lie on the floor where David Cargill shot both twice in the head. Tommy Cargill received a life sentence. David Cargill's federal appeal challenging the fairness of his trial is pending.

Timothy Don Carr, 26, was sentenced to die in Monroe County in October 1992. He and his girlfriend were partying the night of Oct. 8, 1992, with Keith Patrick Young, 18, whom Mr. Carr stabbed numerous times, slit his throat and bashed his head with a baseball bat. Mr. Carr, who was on probation, and his girlfriend stole Mr. Young's car and $120. The girlfriend was sentenced to life in prison plus 20 years. Mr. Carr's first appeal to the state Supreme Court was denied in February. Mr. Carr's execution was set in August. Since Mr. Carr had no attorneys, a deadline to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court passed in May. The state Supreme Court and U.S. Supreme Court rejected the Attorney General's attempt to lift the stay of execution.

Roddy Elroy Childress, 49, was sentenced to death in May 1994 in Glynn County for the shooting deaths of his half-sister's husband, Patrick Kappus, 40, and her daughter, Emma Kappus, 15, on May 1, 1989. Mr. Childress' conviction and sentence were overturned in March 1996, however, because Mrs. Kappus violated the rules of sequestration during the trial by talking to other witnesses about testimony. Mr. Childress is awaiting a new trial.

Scott Lynn Christenson, 26, was sentenced to death in Harris County in March 1990 for the robbery and murder of Albert L. Oliver III, 31. Mr. Oliver gave Mr. Christenson a ride on July 6, 1989. His body, with five gunshot wounds, was found later that day. Mr. Christenson, then 18, had a juvenile record of burglaries and thefts and adult convictions for forgery, burglary and car thefts. His state appeal challenging the fairness of his trial has been pending since October 1995.

Michael Anthony Cohen, 40, was sentenced to death in Glynn County in December 1986. Mr. Cohen, who had a history of burglary convictions, had been out of prison about a month when he started burglarizing homes again, stealing a handgun Oct. 13, 1985. The next day, Auzzie Douglas Sr., 55, a disabled man, was shot to death inside his home. His case has been sent back to Glynn County on the issue of mental retardation.

Robert Lewis Collier, 49, was convicted in Catoosa County in August 1978 for shooting to death a sheriff's investigator, Baxter Shavers, 24. Investigator Shavers was investigating a robbery call April 14, 1978, when shot. Investigator Shavers, the youngest chief deputy in state history at the time, was married with one son. Jeremy Shavers followed in his father's footsteps and now is a sheriff's deputy in Catoosa County. Mr. Collier's second federal appeal challenging the fairness of his conviction is pending in the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Roger Collins, 38, was sentenced to death in Houston County on Feb. 17, 1978, for the rape and murder of Deloris Luster, 17. On Aug. 6, 1977, he and a friend offered Ms. Luster a ride. The teen was raped, then Mr. Collins killed her with a car jack. William Durham was sentenced to life in prison. Mr. Collins' case was returned to the Houston County trial court in March 1991 on the issue of mental retardation.

Robert Dale Conklin, 36, was sentenced to death in June 1984 in Fulton County. Mr. Conklin was having an affair with attorney George Grant Crooks, 27, when the two got into an argument on March 28, 1984, and Mr. Conklin stabbed the other man in the ear with a screw driver. Mr. Conklin said he panicked afterward because he was on parole at the time. So he drained the blood from Mr. Crook's body and cut it up into nine pieces. Mr. Conklin's appeal is pending in federal court.

John Wayne Conner, 40, was sentenced to death in July 1982 in Telfair County. Six months before, Mr. Conner was drinking with his friend, James T. White, 29, when he became enraged and started beating Mr. White with his fist, a whiskey bottle and a stick. In the most recent appeal action, Mr. Conner's state appeal challenging the fairness of his trial was denied in December. That decision is being appealed to the state Supreme Court.

Eddie A. Crawford, 50, was sentenced to death in Spalding County in March 1984 for the kidnapping, rape and murder of his 29-month old niece, Leslie Michelle English, on Sept. 25, 1983. The toddler was strangled to death, bruised and raped. He told police he remembered the toddler had been in his car and remembered carrying her out of the car. He was sentenced to death twice. He was on probation when he killed the girl.

Samuel David Crowe, 36, was sentenced to death in Douglas County in November 1989. The former church deacon was convicted of the robbery and murder of his former boss, Joe Pala, 39. Mr. Pala was knocked to the floor of Wickes Lumber Co., shot, hit with a paint can and crowbar, and covered in paint the night of March 2, 1988. Mr. Crowe had no criminal record before the killing. His first appeal to the state Supreme Court was denied in June 1995, and the U.S. Supreme Court rejected hearing the case on appeal in March 1996.

George Bernard Davis Jr., 39, was sentenced to death in Elbert County in February 1985. He was convicted of robbing and shooting to death Richard L. Rice, 63. The garage owner was found dead in his tow truck Feb. 13, 1984. His wallet had been stolen along with more than $800. Mr. Davis had argued with Mr. Rice over payments for car repairs. Davis, who had no major felony convictions before the killing, has been awaiting a trial court decision on the issue of mental retardation since April 1990.

Troy Anthony Davis, 28, was sentenced to death in Chatham County in September 1991 for killing an off-duty police officer, Mark Allen MacPhail, 27. Officer MacPhail was trying to break up a fight between Mr. Davis and another man when Mr. Davis shot him. He was wearing a bullet-proof vest, but as Mr. Davis stood over the officer and shot him again, the bullet pierced his side. Mr. Davis' state appeal challenging the fairness of his trial has been pending since March 1994.

Andrew Grant DeYoung, 22, was sentenced to die in October 1995 in Cobb County. He and a friend, David Michael Haggerty, 28, stabbed to death his parents and little sister Gary Wayne, 42, Kathryn, 41, and Sarah, 14, on July 15, 1993. Mr. DeYoung had no prior criminal record. Mr. Haggerty was sentenced to life in prison in July 1996. An appeal hasn't been filed yet for Mr. DeYoung.

Wilbur Wiley Dobbs, 48, was sentenced to death in Walker County in May 1974 for the shotgun slaying of Roy L. Sizemore, 50. The grocery store owner was killed Dec. 14, 1973, when Mr. Dobbs and two others robbed the store. A salesman visiting the store was also shot but survived, as did a female customer who suffered a skull fracture after she was hit with a gun butt. Mr. Dobbs' co-defendants were sentenced to life in prison. In May, a federal judge ordered a new sentencing hearing for Mr. Dobbs, ruling his trial attorney was ineffective.

Leonard Maurice Drane, 37, was sentenced to death in Elbert County in September 1992 for killing Linda Renee Blackmon, 27, on June 13, 1990, while he was on probation for other crimes. The trial was moved from Spalding County to Elbert County. She had been raped and shot. Her throat was cut. Co-defendant David Robert Willis was sentenced to life in prison. Three years ago, the state Supreme Court sent Mr. Drane's case back to the trial court for a ruling on appeal issues.

Eric Lynn Ferrell, 34, was sentenced to death in September 1988 in DeKalb County for the robbery and murder of his 72-year-old grandmother and 15-year-old cousin. The bodies were found Dec. 30, 1987. Both had been shot twice in the head at close range. Mr. Ferrell was on probation at the time. At the time of his grandmother's and cousin's killings, two of his uncles had killed a man and police initially thought the double homicide was revenge for that homicide. When arrested, police found four spent .22-caliber casings in Mr. Ferrell's pockets, along with $600. The murder weapon was later found at his home. A state appeal challenging the fairness of his trial and sentence has been pending since July 1995.

Eddie William Finney Jr., 40, was sentenced to death in Jones County in November 1977 about three months after the bodies of Thelma Kalish, 69, and Ann Kaplan, 60, were found in their home. On Sept. 22, 1977, the women were robbed, raped and beaten to death. Mr. Finney and Johnny Mack Westbrook, who had both done yard work for the women, were convicted and sentenced to death. The Georgia Supreme Court reversed Mr. Westbrook's death sentence because the judge sent the jury back into the deliberation room when it first voted for life. Mr. Westbrook died of heart disease in prison in 1993. Mr. Finney's case was returned to the trial court in April 1991 for a decision on the issue of mental retardation.

Son Fleming, 66, was sentenced to death in January 1978 in Lanier County for the murder of Ray City Police Chief Ed Giddens, 29. The officer stopped a speeding car in February 1976, not knowing the men inside had just pulled an armed robbery. It was Chief Giddens' last day on the job he had intended to move to Florida. Mr. Fleming's brother was sentenced to life in prison. Henry Willis III, 36, was sentenced to death, too, and he was executed May 18, 1989. Mr. Fleming was the test case for the 1988 mental retardation exception for the death penalty. He was returned to Lanier County in March 1991 for a new sentencing trial.

Melbert Ray Ford Jr., 36, was sentenced to death in Newton County in October 1986. Seven months before, Mr. Ford shot to death his former girlfriend, Martha Chapman Matich, 31, and her 11-year-old niece, Lisa Renee Chapman. Although prosecutors contended Mr. Ford killed the woman and child in revenge for a romantic breakup, Mr. Ford also robbed the store where Ms. Matich was working that night. His attorneys are currently appealing the denial of his first appeal challenging the fairness of his trial and sentence.

Timothy Tyrone Foster, 29, was sentenced to death in Floyd County in May 1987. Mr. Foster confessed that on the night of Aug. 27, 1986, he broke into the home of Queen Madge White, 79. Her jaw was broken, she had gashes on the top of her head and she had been sexually assaulted and strangled. Mr. Foster had a juvenile record including armed robbery. In July 1991, his case was sent back to the trial court on the issue of mental retardation.

Wallace Marvin Fugate III, 47, was sentenced to death in Putnam County in April 1992 for killing his estranged wife, Pattie Fugate, 40. On May 4, 1991, he broke into his wife's home and waited for her. When she came in, he grabbed Ms. Fugate and dragged her outside to his vehicle, pistol whipped her about 50 times and then shot her in the forehead. Their son, who witnessed the killing and testified against his father, was the victim of a homicide the next year. One of the men who beat his son to death is now on Death Row too. Mr. Fugate's attorney has appealed the denial of his first appeal, challenging the fairness of his trial and sentence in October 1996.

Kenneth E. Fults, 28, was sentenced to death in May in Spalding County for killing a neighbor, 19-year-old Cathy Bonds, after breaking into her home on Jan. 30, 1996. Mr. Fults smothered her with a pillow and then shot her before stealing her car. Mr. Fults had a history of mental illness but no prior felony convictions. A direct appeal hasn't been filed yet.

Carlton Gary, 46, was sentenced to death in Muscogee County in August 1986. Between Sept. 11, 1977, and April 19, 1978, eight elderly women in Columbus were raped and strangled in their homes. One survived. In 1984, a gun stolen in the same neighborhood as the killing spree was found in Michigan in the possession of Mr. Gary's cousin. Mr. Gary's fingerprints were then matched to some left in the homes of four of the homicide victims. He was convicted of murdering three women. Mr. Gary had been accused of the rape and murder of an 89-year-old New York woman in 1970 and an additional rape, but he blamed another man who was tried and acquitted. Mr. Gary's second state appeal challenging the fairness of his trial and sentence was denied in December 1995. On May 27, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected an appeal on the same grounds.

Johnny Lee Gates, 41, was sentenced to death in Muscogee County in September 1977. On Nov. 30, 1976, Mr. Gates posed as a gas company employee to get into the home of 19-year-old Katharina Wright, whom he robbed, raped and then shot in the head. Mr. Gates was on parole at the time. He was arrested on unrelated charges Jan. 31, 1977, and confessed. Between Mrs. Wright's killing and his arrest, Mr. Gates also committed two other armed robberies and voluntary manslaughter. In 1992, Mr. Gates' case was sent back to Muscogee County for a new sentencing trial on the question of mental retardation.

Exzavious Lee Gibson, 25, was sentenced to death in Dodge County in June 1990. He was convicted of robbing and stabbing to death 46-year-old Douglas Coley at the Eastman convenience store where Mr. Coley was working Feb. 2, 1990. Mr. Gibson, who was covered in Mr. Coley's blood when arrested shortly after the robbery-slaying, was convicted four months later. This year, Augusta Judicial District Superior Court Judge J. Carlisle Overstreet denied Mr. Gibson's state appeal challenging the fairness of his trial, although Mr. Gibson had no legal counsel.

Fred Marion Gilreath Jr., 59, was sentenced to death in Cobb County in March 1980 for the killing of his estranged wife and her father. On May 11, 1979, Linda Gilreath, 28, and Gerrit W. VanLeevwen, 57, were shot to death she had been shot five times with a rifle, and then shot in the face at close range with a 12-gauge shotgun, he was shot with a rifle, shotgun and handgun. Mr. Gilreath's federal appeal challenging the fairness of his trial was denied in April 1996.

Daniel Greene, 30, was sentenced to death in December 1992 in Clayton County where the venue was changed from Taylor County. He committed a violent crime spree the night of Sept. 27, 1991, when he walked into a Reynolds convenience store and pulled a clerk into the back room, demanded money and stabbed her. He then stabbed customer Bernard Walker, 20, in the heart, killing him. A short time later, he forced his way into the home of an elderly couple he knew and stabbed both and stole their car. He then went to a convenience store in Warner Robins where he robbed and stabbed the clerk. In May, the state Supreme Court let the conviction and sentence stand.

Dennis Charles Hall, 41, was sentenced to death in August 1990 in Barrow County for the shotgun killing of his 10-year-old son, Adrian Hall. Police had been called to the Hall home numerous times before Jan. 7, 1990, when they found a drunken Hall and the dead child. His wife and two daughters told police Mr. Hall became enraged at Adrian for being noisy. The girls tried to hide Mr. Hall's gun, but he found it and shot the boy. He told a neighbor afterward, " I couldn't learn him nothing by beating him with a belt. So I guess I learned him something this time." His state appeal challenging the fairness of his trial has been pending since December 1995.

Willie James "Bo" Hall, 40, was sentenced to death in DeKalb County in February 1989 for killing his estranged wife, Thelma Hall, 23, who moved out of the family home just six days before her murder. On July 11, 1988, Ms. Hall made a frantic call to 911, and the dispatcher heard the sound of breaking glass and screams. Police arrived in minutes but, Mr. Hall had stabbed her 17 times. The day before, Mr. Hall told his sister-in-law that he would kill his wife and wouldn't get more than 10 years in prison for it. His state appeal was denied.

Emanuel Fitzgerald "Demon" Hammond, 30, was sentenced to die in Fulton County in March 1990 for the kidnapping, robbery, rape and murder of 27-year-old Julie Love. She was last seen by her boyfriend the night of July 11-12, 1988, when she left his apartment for home. A year later, in August 1989, Janice Weldon filed assault charges against Mr. Hammond after he tried to strangle her. Ms. Weldon told police that he and his cousin Maurice Porter killed Ms. Love. Mr. Porter confessed and took police to Ms. Love's remains near a trash pile. Ms. Love was kidnapped at gunpoint, Mr. Porter told police. Ms. Love was raped by Mr. Porter and beaten. Then the men tried to strangle her by wrapping a coat hanger around her neck and pulling the opposite ends. When that didn't work, Mr. Hammond shot her. Mr. Hammond had carjacked three other women stabbing one and leaving her to die on a trash pile, and he also broke into a woman's home and raped her. As a juvenile, he raped, robbed and kidnapped a woman and slit her throat, and he raped and sodomized another. While awaiting trial, he bragged to a deputy that he also had raped Ms. Love. His state appeal challenging the fairness of his trial was filed in December 1995.

George Russell Henry, 28, was sentenced to death in Cobb County in November 1994 for shooting to death a police officer. Officer Robert Ingram, a two-year police veteran, was shot in the face and behind his left ear while he was investigating a report of a suspicious person. Mr. Henry had previously been convicted of burglaries and forgery and was on probation at the time of the murder. His first appeal to the state Supreme Court hasn't been filed yet.

Robert Karl Hicks, 40, was sentenced to death in January 1986 in Spalding County for the kidnapping, rape and murder of 28-year-old Toni Strickland Rivers. On July 13, 1985, Ms. Rivers was waiting for a friend at a public park when she disappeared. That night, two men driving down a country road heard a scream and saw a man making stabbing motions. Ms. Rivers bled to death. Mr. Hicks had previously been convicted of rape. At his trial, doctors testified yes and no that Mr. Hicks was mentally ill. The denial of his state appeal challenging the fairness of his trial was upheld by the state Supreme Court in November 1995.

Jose Martinez High, 38, was sentenced to death in December 1978 in Tallaferro County for the kidnap and murder of 11-year-old Bonnie Bulloch who was kidnapped along with his father in July 1976. Judson Ruffin and Nathan Brown also were convicted and sentenced to death for Bonnie's murder, but their cases were reversed on appeal. They were resentenced to life in prison. A fourth man with the gang when Bonnie and his father were kidnapped and shot, Alphonso Morgan, was convicted and sentenced to die in Richmond County for another abduction and murder in the gang's crime spree. His sentence, however, also was overturned and he's now serving a life sentence. A second federal appeal challenging the fairness of Mr. High's trial is pending.

John W. Hightower, 53, was sentenced to death in Morgan County in May 1988 for killing his wife and two stepdaughters. Mr. Hightower's trial was moved from Baldwin County, where on July 12, 1987, the bodies of Dorothy Hightower, 42, Sandra Reaves, 22, and Evelyn Reaves, 19, were found at their home. Each had been shot. Mr. Hightower was arrested hours later in his wife's car, a bloody handgun inside. He bought the murder weapon the day before the slayings. A federal appeal challenging the fairness of his trial has been pending since November.

Floyd Ernest Hill, 60, was sentenced to death in July 1981 in Cobb County for shooting to death Austell Police Officer Gregory Mullinax. On Feb. 8, 1981, Officer Mullinax was sent to a trailer park on a domestic disturbance call. Officer Mullinax became the target of the battling couple when Mr. Hill got into the fray and shot the officer, and the officer shot and killed another person in the fight. Mr. Hill's death sentence was overturned on federal appeal in December.

Warren Lee Hill, 36, was sentenced to death in September 1991 in Lee County for beating to death fellow inmate Joseph Handspike, 34, with a nail-embedded board on Aug. 17, 1990. At the time, Mr. Hill was serving time for a 1985 murder. Mr. Hill's state appeal challenging the fairness of his trial has been pending since April 1994.

Travis Clinton Hittson, 26, was sentenced to death in Houston County in March 1993 for killing 20-year-old Conway U. Herbeck, a fellow sailor. On April 3, 1993, Mr. Hittson, Edward Vollmer and the victim left Pensacola, Fla., where they were stationed, and drove to Mr. Vollmer's parent's home in Warner Robins. Mr. Vollmer wanted to kill Mr. Herbeck and gave Mr. Hittson a baseball bat to use on April 5, 1992. Mr. Hittson hit the victim in the head several times with the bat and then shot him. They cut up Mr. Herbeck's body, buried the torso in Houston County and the rest in Pensacola. Mr. Vollmer was sentenced to life in prison. Mr. Hittson had never been convicted of a felony before the killing. A state appeal challenging the fairness of his trial has been pending since December 1995.

Dallas Bernard Holiday, 34, was sentenced to death in November 1986 in Jefferson County for killing 66-year-old Leon Johnson Williams on March 11, 1986. Mr. Williams went on his usual early morning walk when Mr. Holiday attacked him, hitting him in the head at least seven times and shooting him. Mr. Holiday had broken into a home the night before and stolen the murder weapon. Mr. Holiday had prior felony convictions. His case was returned to the trial court on the issue of mental retardation in June 1990.

Robert Wayne Holsey, 31, was sentenced to death on Feb. 13, 1997, in Morgan County where his trial was moved. In December 1995, he shot to death Baldwin County Sheriff's Deputy Will Robinson, 26. The officer had stopped Mr. Holsey's vehicle after an armed robbery. At the time, Mr. Holsey had been out on parole less than a year following convictions for assault and armed robbery.

Tracy Lee Housel, 38, was sentenced to death in February 1986 in Gwinnett County for the rape and murder of 46-year-old Jean D. Drew. Ms. Drew was in the habit of stopping at a truck stop for a snack after her ballroom dancing lessons. On the night of April 7, 1985, she met Mr. Housel at the restaurant. Her body was found the next day, and he was arrested about a week later in Daytona Beach, Fla., after using her credit cards. He confessed to killing Ms. Drew, killing a man in Texas, and trying to kill two others in Illinois and Texas. He also confessed to murders in California and Tennessee. A decision is pending from the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals on Mr. Housel's federal appeal challenging the fairness of his trial.

Carl J. Isaacs, 43, was sentenced to death in Seminole County in 1974 and again in Houston County at a retrial in 1988. In May 1973 when he was 19 years old, he escaped from a Maryland prison and took off for Florida with his brother Billy, half brother Wayne Coleman and friend George Dungee. On May 14, 1973, they ran out of gas in Seminole County and stopped to burglarize a trailer. Within hours, they had shot to death Jerry Alday, Ned Alday, Jimmy Alday, Chester Alday and Aubrey Alday in addition to raping Mary Alday and then killing her. They were arrested in West Virginia with the murder weapons and items belonging to the Alday family. Billy Isaacs, 15 years old at the time of the killings, received a 40-year sentence. He was taken to Maryland in 1993 to serve a life sentence there for murder. At the 1988 retrial, Mr. Coleman and Mr. Dungee received life sentences.

Jonathen Jarrells, 40, was sentenced to death in March 1988 in Walker County for the robbery and murder of Gertie E. Elrod, a 77-year-old woman. On Aug. 24, 1987, Ms. Elrod and her sister, Lorraine Elrod, were attacked in their home by Mr. Jarrells. He stabbed both with scissors, tied their hands and feet and beat them with an iron. Lorriane survived the attack although she lost the sight in one eye and her hearing in one ear. When arrested in Hazard, Ky., he had items belonging to the Elrod sisters in his possession. In May 1991, Mr. Jarrell's case was sent back to the trial court on the issue of mental retardation.

Lawrence Joseph Jefferson, 42, was sentenced to death in March 1986 in Cobb County for the robbery and killing of his construction job supervisor Edward Taulbee, 37. On May 1, 1985, they went fishing at Lake Allatoona. Later, Mr. Jefferson arrived home in the victim's vehicle and told a neighbor, "My fat little buddy is dead." Mr. Taulbee's body was found the next day; he had been beaten with a stick and then his skull was crushed with a 40-pound tree trunk. In 1979, Mr. Jefferson had pleaded guilty in Louisville to armed robbery and burglary. His first appeal to the state Supreme Court and next state appeal challenging the fairness of his trial have been denied.

Larry L. Jenkins Jr., 21, was sentenced to death in Wayne County for the robbery and killing of the owner of a laundry and her 15-year-old son. Mr. Jenkins accosted Terry Ralston, 37, and her son Michael on Jan. 8, 1993. He kidnapped the mother and son and shot them both to death in a rural area. Although sentenced to death in September 1995, his first appeal to the Georgia Supreme Court hasn't been filed yet.

Ashley Lyndol Jones, 23, was sentenced to death in June 1995 in Coffee County. On March 31, 1993, in Ware County, Mr. Jones and co-defendant Allen Brunner were drinking and driving in a stolen vehicle when it developed car trouble. Mr. Jones knocked on the door at Carlton Keith Holland's home and asked for help. As Mr. Holland, 39, leaned over the engine and his wife watched through the window, Mr. Jones slammed a wrench and later a sledgehammer on Mr. Holland's head. Mr. Brunner was sentenced to life without parole. In March, the state Supreme Court affirmed Mr. Jones' conviction and death sentence.

Brandon Aston Jones, 54, was sentenced to death in October 1979 in Cobb County. On June 17, 1979, he and Van Roosevelt Solomon were arrested at a service station after an officer who just happened to drive up heard gunshots. In the storeroom, the officer found 29-year-old Roger Tackett, the station manager, who had been shot in the legs and arms and beaten before the fatal contact shot was fired behind his left ear. Mr. Solomon also was sentenced to death and he was executed on Feb. 20, 1985. In 1989, a U.S. District Court judge reversed Mr. Jones' sentence, ruling it was unfairly imposed considering the prosecutor's Bible quoting. Mr. Jones is still awaiting a new sentencing trial. In September 1996, the Department of Corrections transferred him off death row and into the general prison population.

Ronald Leroy Kinsman, 39, was sentenced to death April 18, 1987, in Muscogee County for the robbery and murder of a Hardee's manager. Bruce Keeter, 29, was found shot to death the morning of Sept. 14, 1984. About $400 was stolen from the restaurant safe, and Mr. Keeter's car was later found abandoned. Two years later, a friend of Mr. Kinsman's told police Mr. Kinsman had admitted to the murder. In 1976, Mr. Kinsman had been convicted of another robbery-murder and was paroled not long before Mr. Keeter was murdered. A state appeal challenging the fairness of his trial has been pending since December 1995.

J.W. Ledford Jr., 25, was sentenced to death in Murry County with a jury selected from Gordon County in November 1992 for the murder of a neighbor he had known all his life, Dr. Harry Johnston Jr., 73. On Jan. 31, 1992, Mr. Ledford went to the Johnston home and asked his wife, Antoinette, to speak to Mr. Johnston. He forced his way into the home at knife point, demanding money and guns. Mr. Johnston's body was found later, his head nearly cut off and a knife in his back. Mr. Ledford's state appeal challenging the fairness of his trial has been pending since December 1995.

James Allyson Lee, 22, was sentenced to death in June by a Charlton County Superior Court jury. On Nov. 17, 1996, he shot his 43-year-old stepmother, Sharon Varnadore Chancey, to death. Although Mr. Lee pleaded with the jury to spare him because he wasn't the same man who committed murder, when first questioned by police, Mr. Lee said killing was so easy it would be easy to do again.

Larry Lee, 36, was sentenced to death in November 1987 in Wayne County for the robbery and killing of a couple and their 14-year-old son. Clifford and Nina Murray Jones Sr., both 48, and Clifford Jones Jr. were killed April 26, 1988 all had been shot, stabbed and beaten. Mr. Lee's brother Bruce Lee was reportedly also involved in the triple homicide, but he died while committing a burglary two months after the Jones family killings. Mr. Lee's state appeal challenging the fairness of his trial was denied, but the judge was ordered to reconsider it in June 1995 because of new case law.

William Anthony Lipham, 33, was sentenced to death in Coweta County in February 1987 for the rape, robbery, burglary and murder of a 79-year-old woman, Kate Furlow. Mr. Lipham was seen in Ms. Furlow's home on Dec. 4, 1985. The next day, her nude body was found at home with a .25-caliber bullet wound in her head. Mr. Lipham confessed but said he had sex with the elderly woman after she was dead. A state appeal challenging the fairness of his trial has been pending since 1989.

William Earl Lynd, 42, was sentenced to death in February 1990 for killing his girlfriend three days before Christmas 1988. Mr. Lynd was living with 27-year-old Virginia "Ginger" Moore when they got into an argument and he shot her in the face and went outside. Ms. Moore followed him outside where he shot her again and put her in the trunk of his car. When he heard noise from the trunk, he stopped the car and shot her a third time. After burying her body, Mr. Lynd drove to Ohio where he shot and killed another woman. He returned to Georgia and surrendered to police on New Year's Eve. Mr. Lynd had numerous convictions for prior assaults on women. His state appeal challenging the fairness of his trial has been pending since December 1995.

James Mathis, 51, was sentenced to death in Douglas County in May 1991 for killing J.L. Washington and his wife Ruby Washington, both 69. On Thanksgiving Day 1980, Mr. Mathis was seen in the back seat of the Washington's vehicle as they drove through their apartment complex. Their bodies were found in a wooded area. Both had been beaten, stabbed and shot. In 1989, a U.S. District judge reversed Mr. Mathis' death sentence because of ineffective counsel, but in 1992 the 11th Circuit sent the case back to the federal judge to explain the ruling.

Mark Howard McClain, 30, was sentenced to death in Richmond County in September 1995 for the robbery and murder of a Domino's Pizza store manager. In November 1994, Mr. McClain, who had previously been convicted of armed robbery, forced his way into the closed Domino's store and robbed Kevin Brown, 28. As Mr. McClain turned to leave he shot and killed Mr. Brown, an eyewitness testified. The witness got the license tag number off the getaway car and police traced the vehicle to Mr. McClain's girlfriend. Earlier this year, the state Supreme Court affirmed Mr. McClain's conviction and sentence, and in June, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to consider an appeal of that decision.

James R. McDaniel, 23, was sentenced to death in June by a Butts County Superior Court jury. He was convicted of murdering his grandparents Erner and Eugene Barkley, ages 70 and 75, and his 10-year-old stepbrother, Justin Davis. Family members of the victims, also Mr. McDaniel's family, opposed the death penalty for the young man with a history of commitments to mental hospitals and crack addition. Police said Mr. McDaniel robbed his grandfather to buy crack.

Kim Anthony McMichen, 39, was sentenced to death in Douglas County in July 1993 for the shooting deaths of his estranged wife and her boyfriend. On Nov. 16, 1990, he shot Luan McMichen, 27, and Jeff Robinson, 27, and then walked his 8-year-old daughter past the bodies. Ms. McMichen's friends told police he had harassed her since she left him in January 1990 and that he had raped her. Mr. McMichen had no prior criminal convictions. His first appeal to the Georgia Supreme Court hasn't been filed.

Jimmy Fletcher Meders, 36, was sentenced to death in April 1989 in Glynn County for the robbery and murder of a convenience store clerk. Don Anderson, 47, was shot twice as he lay on the floor after being robbed of $38 the night of Oct. 14, 1987. Police say two men with Mr. Meders weren't involved in the killing and they weren't prosecuted. Mr. Meders' current attorneys claims just the opposite that the other two men did the robbery and killing while a drunken Mr. Meders was in the back of the store. All three men had prior felony convictions. Mr. Meders state appeal challenging the fairness of his trial has been pending since April 1993.

Michael Miller, 34, was sentenced to death in November 1988 in Walton County for the robbery and killing of 35-year-old Larry Judson Sneed. On Oct. 29, 1987, Mr. Sneed was driving along a Walton County road when shots were fired at his vehicle and he was forced off the road. Mr. Sneed got out and ran but he was shot in the back and bled to death. Two days before, Mr. Miller and another man had kidnapped a man during a burglary. In January 1995 his case was sent back to the trial court on the issue of mental retardation.

Terry Mincey, 37, was sentenced to death in August 1982 in Bibb County for the robbery and killing of a store clerk, the mother of two small children. On April 12, 1982, Paulette Riggs was working at a convenience store when Mr. Mincey and two others decided to rob it. After making Ms. Riggs hand over the money, he walked her outside where Russell Peterman was pumping gas into his car. Mr. Mincey shot Mr. Peterman in the chest and when he fell, Mr. Mincey shot him again in the face. Ms. Riggs tried to run away, but Mr. Mincey shot her and after she fell, he shot her in the face. Mr. Peterman survived but lost 40 percent of his vision in one eye and lives with a bullet lodged near his spine. Mr. Mincey, a preacher's son, had at least three prior armed robbed convictions in 1977. His two co-defendants in the 1989 killing received life sentences. In September 1996, his federal appeal challenging the fairness of his trial was filed.

Nelson Earl Mitchell, 34, was sentenced to death in January 1990 in Early County for killing Iron City Police Chief Robert Cunningham, 51, during a routine traffic stop. Mr. Mitchell, who had prior convictions for larceny and theft, testified that the white police chief used racial slurs and the gun went off during a struggle. One issue the defense may raise on appeal is an allegation that the jury foreman's husband was sitting in the courtroom and allegedly signaled his wife to vote for death by drawing his finger across his throat. Although it's been more than seven years since his conviction, the first appeal to the Georgia Supreme Court hasn't been filed.

William Mark Mize, 40, was sentenced to death in Oconee County in December 1995 after demanding the jury sentence him to death. The Klansman ordered the killing of William Eddie Tucker, 34, because he was angry Mr. Tucker had messed up an arson job on a crack house in October 1994. Mr. Mize had prior convictions for escape, theft, arson, and being a felon in possession of a firearm. Co-defendants Christopher Hattrup and Mark Allen received life sentences.

Stephen Anthony Mobley, 31, was sentenced to death in Hall County in February 1994. During a Feb. 17, 1991, robbery of a Domino's store, he shot and killed 24-year-old John Copeland Collins. Mr. Mobley had been convicted of burglary and forgery, but he didn't get into violent crimes until 1991 when he began a robbery spree that ended in Mr. Collins' death. While awaiting trial, Mr. Mobley raped his cellmate and had Domino's tattooed on his chest. His state appeal challenging the fairness of his trial has been pending since March 1996.

Larry Eugene Moon, 52, was sentenced to death in Catoosa County in January 1988 for killing 34-year-old Ricky Callahan who had driven to a convenience store to buy his wife some aspirin on Nov. 24, 1984. At the time Mr. Callahan was murdered, Mr. Moon was hiding out in Georgia after committing a Tennessee murder. After killing Mr. Callahan, Mr. Moon drove back to Chattanooga and on Dec. 1, 1984, he robbed an adult book store and kidnapped a female impersonator whom he raped. The next day, he killed another man in Gatlinburg, Tenn., and shot at a woman; then on Dec. 7, 1984 he robbed a Chattanooga convenience store. He was arrested Dec. 14, 1984 in Oneida, Tenn., in another stolen car containing a number of guns, including Mr. Callahan's murder weapon. Mr. Moon's prior record included seven burglaries, three aggravated assaults and escape. Mr. Moon's federal appeal challenging the fairness of his trial was filed in April 1996.

Carzell Moore, 45, was sentenced to death in January 1977 in Monroe County for the Dec. 12, 1976 rape, robbery and murder of 18-year-old Teresa Carol Allen, an honors college student. Mr. Moore met up with Roosevelt Greene the day before the killing. Mr. Greene had just escaped from prison. On Feb. 12, 1976, they robbed the store where Ms. Allen worked, taking her, $466 and her vehicle. Both men raped Ms. Allen and Mr. Moore shot her. Mr. Green was arrested in South Carolina driving Ms. Allen's car. He was sentenced to death and executed Jan. 9, 1985, at the age of 28. Mr. Moore's sentence was overturned once but he was resentenced to death. It was overturned a third time, and a new sentencing trial has been pending since August 1992. Mr. Moore, who has a Web site, was transferred to the general prison population last September.