25th murderer executed in U.S. in 2000

623rd murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

3rd murderer executed in Virginia in 2000

76th murderer executed in Virginia since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

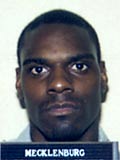

| Lonnie Weeks, Jr. W / M / 20 - 27 |

Jose M. Cavazos OFFICER H / M / 50 |

Summary:

Virginia State Trooper Jose Cavazos was assigned to traffic patrol in the Dale City area on Feb. 23, 1993. At around 12:40 a.m. Cavazos pulled over a speeding 1987 Volkswagen Jetta traveling from Washington, D.C., to North Carolina. Weeks was a passenger in vehicle driven by his uncle, Lewis Dukes. Trooper Cavazos approached and asked Weeks to get out and the North Carolina man complied. Weeks, carrying Glock 9 mm handgun loaded with armor piercing ammunition known as "man-stoppers", fired at least 6 bullets at Trooper Cavazos, two of which entered his body beside the right and left shoulder straps of the protective vest he was wearing. The car stopped by Trooper Casavos turned out to be stolen. Both Weeks and Dukes were captured within an hour of the crime, tracked by dogs to a nearby motel. Weeks testified at his 1994 trial: "And as I stepped out the car, it was like something had just took over me that I couldn't understand. . . well, to me, I felt like it was an evil - evil spirit or something."

Citations:

Weeks v. Com., 450 S.E.2d 379 (Va. 1994) (Direct Appeal).

Weeks v. Angelone, 176 F.3d 249 (4th Cir. 1999) (Habeas).

Weeks v. Angelone, 120 S.Ct. 727 (2000).

Internet Sources:

Virginians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty

BACKGROUND INFORMATION ABOUT LONNIE WEEKS, JR.

Lonnie grew up in South East Washington D.C. His father died when he was 10 years old. Shortly thereafter, his mother became addicted to drugs and began to steal. When Lonnie was 14 years old, Mrs.Weeks abandoned her children, leaving them with their grandmother in Fayetteville, North Carolina.

In Fayetteville, Lonnie grew up in an area notorious from crime and drugs. Nevertheless, Lonnie's grandmother, Ms. Evelyn Leach, had a strong influence on his life. Lonnie stayed out of trouble and was a well-behaved student. He was an active and enthusiastic member of his church. He held a part-time job. He was captain of his high school basketball team and was well liked by other students, his teachers and his coach. His talent at basketball earned him a scholarship to Mount Olive College.

However, the summer before Lonnie was to begin college, he fathered a child. Remembering the trauma of his own broken home, he gave up his scholarship so he could work to support his new family. Lonnie moved from one low-paying job to the next. Discouraged, he found it increasingly frustrating to work long hours in dead-end jobs while observing the nice lifestyles of others in his neighborhood. In his own words, he "took the easy way out." In April of 1992, Lonnie was arrested for selling marijuana. Because it was his first offense, he was put on probation, but his life continued to spiral. After Lonnie was assaulted and threatened by a local drug dealer, a neighbor gave him a handgun to carry for protection. In February of 1993, Lonnie and a long-time friend broke into the house of an acquaintance who was serving time in jail. Lonnie helped himself to the occupant's car - something he had never been able to afford – and decided to drive to Washington D.C. for a family gathering.

Traveling back from D.C. with his uncle, the car was pulled over for speeding by Trooper Jose Cavazos. When Trooper Cavazos asked Lonnie to step out of the passenger side, Lonnie panicked and shot him. When he was 21 years old, he was sentenced to death for this crime.

Without exception, Lonnie's family, his friends, his teachers, his coach, his minister, his employers — were shocked to learn what Lonnie had done. None could believe that this polite, soft-spoken young man, who had never shown the slightest propensity for violence, could have committed such a violent act. No one was more stunned than Lonnie himself.

Hours after the shooting, Lonnie Weeks expressed his profound remorse. As he confessed to shooting Trooper Cavazos, he told the officer, "I would rather for me to be dead than him." Since that time he has consistently expressed his deep sorrow for what he has done and the pain he has caused the Cavazos family. At his trial, Lonnie testified:

"I apologize for what I have done. I feel that I took an innocent man's life."

"I also know that what I have done, it was very – it's very wrong, is hurting, because I know what it feels like to lose somebody that you love."

"I've hurt my own family, as well as his family. Sometimes I actually feel like I can't live with myself, but that, now that I'm back with the Lord, He give me the strength."

"I pray for my family and his family every night."

"I feel very ashamed and low. . . . , every time I hear someone talk about Mr. Cavazos, I begin to cry because it hurts me. It hurts me so bad into my heart that sometimes I actually feel like I could die from that pain."

"I guess I felt like I didn't need [the Lord] any more, and so, to myself I say, well, I'm paying for – by my turning my back on Him, I obviously have an indecent mind."

Since his trial, two of Lonnie's jurors have explained that they did not want to sentence Lonnie to death, but the jury misunderstood the instructions they were given by the court. They have asked Governor James Gilmore to spare Lonnie's life.

PLEASE JOIN LESLIE AND TREVOR CAVAZOS IN THEIR REQUEST THAT GOVERNOR GILMORE SPARE THE LIFE OF THE MAN WHO SHOT THEIR FATHER

At 21 years of age, Lonnie Weeks was sentenced to death for shooting Virginia State Trooper Jose Cavazos. He is scheduled to be executed on March 16, 2000. The two surviving children of Trooper Cavazos have asked Governor Gilmore to spare Lonnie Weeks' life. Cavazos' daughter, Leslie, has written to the Governor:

"Please take into consideration the feelings my brother and I have in this matter. We have thought about this very carefully. In our hearts, we have forgiven all that has been done to our family. We want to set an example for society. We do not condone the act of taking the life of another human being in any way, or for any reason. It is below the level of an intelligent human being. This is not (capital punishment) the band aid that will heal society. It only creates a higher level of animosity in our lives."

Leslie's brother, Trevor, has also explained:

". . . I know what it [is] like to live with a tragic, violent death of a loved one. At the time of my father's death I personally would have loved to harm Lonnie Weeks, but that was pure hate, and I've grown up a lot since then. Now I know forgiveness is better than vengeance, and that love is better than hate. I never want to see anyone in my lifetime ever go through what I have, and currently the state is about to make another child fatherless. Yes, I mean Lonnie Weeks' children will never have the chance to make contact with their dad later in life, and later in life is when its so necessary. Take it from someone who knows. . . . Please, breakthis cycle of violence by sparing Lonnie Weeks' life."

Please join their request and urge the Governor to spare Lonnie Weeks' life because:

Lonnie has taken full responsibility for his actions and has constantly expressed extreme remorse for what he done and the pain he has caused. Realizing how far he had strayed from the Christian values instilled in him by his grandmother, Lonnie renewed his faith and finds strength in his relationship with God. Lonnie remains close to his family and, in spite of his situation, is a source of encouragement to his younger brother, D'Angelo, and his two sons, D'Angelo, 9, and Jamaiz, 8. He poses no threat to society. We should follow the example set by Leslie and Trevor Cavazos and show that we, as a community, value redemption and reconciliation over vengeance.

Lonnie Weeks was convicted of murdering a state trooper during a 1993 traffic stop in Dale City, Virginia. Weeks, 26, shot Trooper Jose Cavazos six times in the back, as he was walking away, with a Glock 9mm handgun, using hollow-point bullets known on the street as "man-stoppers." Weeks was a passenger in a car being driven by his uncle, Louis Dukes. The officer had pulled over the car for speeding on Interstate 95. Weeks and Dukes were captured within an hour of the crime, after being tracked by dogs to a nearby motel. Weeks was convicted of capital murder, grand larceny and illegal possession of a handgun.

One state trooper describes the upcoming execution as "an eye for an eye." Virginia State Trooper Jose M. Cavazos was assigned to traffic patrol in the Dale City area on Feb. 23, 1993, when he became the 45th state trooper killed in the line of duty. Senior state trooper Richard Powell, who worked the midnight shift along with Cavazos, was called to the scene at the Dale City exit ramp off Interstate 95 after learning his friend had been killed - the victim of hollow-tipped bullets known as "man-stoppers." He said the loss of an officer is always a hard reality to accept. "It's something that you accept when you take the job," Powell said Tuesday. "When it happens, I think, reality sets in." Cavazos, originally from Edinburg, Texas, began working for the state in 1969 with the Department of Motor Vehicles. After entering trooper training in 1985, Cavazos began patrolling Prince William County on July 18, 1986. He was promoted a year later. "He was a good man," Powell said. "He was the kind of person you want wearing a blue-and-gray uniform, out there enforcing the law." In 1993 at age 50, Cavazos could have retired, Powell said, but he wanted to earn money to put his children through college. That aspect of his life made his murder that much more senseless, Powell said. "Jose always had a smile on his face," Powell said. "He was easy-going; he really seemed to enjoy life. ... He was a big man. He was a very impressive figure in uniform. He demanded respect and authority when he walked up to someone."

According to court records, at around 12:40 a.m. the morning of the shooting, Cavazos pulled over a speeding 1987 Volkswagen Jetta traveling from Washington, D.C., to North Carolina. The car pulled over on the Dale City exit ramp in Prince William County just off the interstate. When Cavazos approached the Jetta, driven by Weeks' his uncle Lewis J. Dukes Jr., he asked Weeks to get out and the North Carolina man complied. Weeks, carrying a loaded Glock Model 17, 9 mm semi-automatic weapon, fired at least 6 bullets at Cavazos, 2 of which entered his body beside the right and left should straps of the protective vest the trooper was wearing, records state. The car stopped by Casavos turned out to be stolen. "And as I stepped out the car, it was like something had just took over me that I couldn't understand," Weeks testified at his 1994 trial. "It was like something - I felt like something - the best way I can describe it is like something - I can't say something. I knew what it - well, to me, I felt like it was evil - evil spirit or something."

Both of Cavazos' children, Leslie Susan Cavazos-Almagia, 26, of California, and Trevor Virgilio Cavazos, 23, of Virginia, have written letters to the governor asking that Weeks' life be spared. The trooper's wife, Linda Cavazos, has expressed her desire for the state's punishment to be carried out. Powell said that in a state agency with 1,500 troopers, it is impossible to know how everyone feels about the scheduled execution of Weeks. If the execution is carried out, he hopes it will act as a deterrent, he said. "To have someone just come out and shoot him because they were afraid to go to jail for a stolen car...," Powell said, pausing before adding, "For me personally, I feel like it's closure. We reap what we sow, I guess. Police put themselves out there every night so people can sleep at night. We have to have something that makes people think twice." Craig W. Floyd, chairman of the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund, a Washington, D.C.-based organization, said he remembers Cavazos' murder because the case was local, and the trooper's wife has attended several tributes at the D.C. memorial. "I remember how devastating it was, for (Linda Cavazos) in particular," Floyd said. "It shattered a life. A life of a family." He said he hopes Weeks' execution will bring "closure'' to Cavazos' wife. Floyd also spoke about the "solidarity and support" of fellow officers when one of their own is killed in the line of duty. He said officers from all over the country will travel when a fellow officer is killed, as was the case following the murders of Capitol police officers John Gibson and Jacob Chestnut in July 1998. "There is this amazing sense of brotherhood and sisterhood that comes from being a law enforcement officer," Floyd said. "Their mortality is very fragile and when an officer is gunned down in the manner Trooper Cavazos was ... it reminds all of these officers that it could happen to them at any time."

"Virginia Executes Trooper's Killer; Victim's Children Asked for Life Sentence."

(March 17, 2000) JARRATT, Va. (AP) -- A man who gunned down a Virginia state trooper has been executed by injection over the objections of the policeman's children. In a final statement, Lonnie Weeks Jr. said he was sorry "for everything I've done to the Cavazos family, my family, to everyone around the world -- and I just thank the Cavazos family for what they've tried to do for me. I love them." He had been condemned for the 1993 slaying of Trooper Jose M. Cavazos. His execution was opposed by the trooper's grown children, one of whom spoke with Weeks a week ago.

Weeks lost final appeal

Weeks, 27, was scheduled to be executed last September. But with about two hours remaining, the U.S. Supreme Court stayed the execution to hear Weeks' appeal, which argued that the Prince William County jury that convicted Weeks was confused by the sentencing instructions. The jury twice asked the judge for further instructions, and one juror said after the verdict that she didn't know she could opt for a lesser sentence. In a 5-4 decision in January, the justices ruled that the instructions were clear and that Weeks could be executed.

"Slain Trooper's Children Want His Killer Spared," by Robert Anthony Phillips.

(March 14, 2000) JARRAT, Va. (APBnews.com) -- The two surviving children of a state trooper murdered in 1993 have written letters to the governor asking him to spare the life of their father's killer. Lonnie Weeks Jr., 27, is scheduled to be executed by lethal injection Thursday at 9 p.m. for the 1993 murder of Trooper Jose Cavazos, 50. Weeks has admitted shooting Cavazos after he stopped the stolen car he was riding in on Interstate 95. However, while Linda Cavazos, the trooper's widow, reportedly wants Weeks to pay with his life, her two adult children, Leslie Cavazos-Almagia and Trevor Cavazos, have written letters to Gov. James Gilmore III asking that his sentence be commuted to life in prison. Two hours before Weeks was scheduled to die in September 1999, the U.S. Supreme Court stayed his execution.

The 'trauma of another killing'

Now, a new execution date has been set, and Timothy M. Richardson, one of Weeks' attorneys, has cited the slain officer's children in his updated clemency petition to Gilmore. "The adult children of Jose Cavazos want Lonnie Weeks, the man who murdered their father, to live," the petition states. "They believe that commuting his sentence to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole punishes Mr. Weeks sufficiently and appropriately while sparing them the trauma of another killing." In the petition, Richardson quotes extensively from the letters the Cavazos children have written. He also includes statements from two jurors who also are asking that Weeks be saved from lethal injection.

Trooper's daughter chats with inmate

Richardson said Cavazos-Almagia had a telephone conversation with Weeks last Thursday. He said he didn't know the specifics of the conversation, however. "I'm told that they discussed both their feelings and a desire for forgiveness," Richardson said. Neither Linda Cavazos nor her son could be reached for comment. Cavazos-Almagia wished not to speak to APBnews.com about the impending execution. In her August 1999 letter to Gilmore, Cavazos-Almagia said that executing Weeks will not bring her father back and could lead the killer's young children to follow in his footsteps. The condemned man has two children, ages 8 and 9, one of whom Richardson says visits Weeks on death row regularly. Cavazos-Almagia, 27, wrote, "But will his death bring my father back from the dead? Will it set the record straight? Will I, his child, feel less grief? The answer to these questions is 'no.' "I do not agree with the death penalty in this case. I worry that his children will suffer and be angry. Possibly, they will be more inclined to repeat their father's life out of anger and frustration."

From hate to forgiveness

Trevor Cavazos, who was 16 when his father was killed, echoed his sister's feelings in a letter to Gilmore. "I do not believe that executing Lonnie Weeks is just," Trevor Cavazos wrote. "At the time of my father's death, I personally would have loved to harm Lonnie Weeks, but that was pure hate, and I've grown up at lot since then," Trevor Cavazos said in the letter to Gilmore. "Now I know that forgiveness is better than vengeance, and that love is better than hate. "To put closure to this, all I can say is that everyday our society is fighting violence, or better yet the violent cycle of life. Please, break this cycle by sparing Lonnie Weeks life, and show the state is compassionate, kind, forgiving and truly loving, and not vengeful, hateful, inflexible, and above all that the state is not 'God.'" Although Linda Cavazos reportedly favors execution, she is said to respect her children's opinions.

State still wants Weeks to die

The revelation that the family was split over Week's execution first became public in 1999 when the Times-Dispatch of Richmond obtained a copy of the original clemency petition filed by Richardson, which included the letters by the Cavazos children. The fact that the slain trooper's children are asking for Weeks' life to be spared, however, isn't moving state prosecutors. "We are statutorily obligated to uphold the sentence of the court," said David Botkins, spokesman for the attorney general's office. "It is our opinion that the execution move forward. It was a brutal, heinous crime. All of law enforcement in Virginia shudders at the loss of one of their own." "It's unusual that the family split like that," said Paul Ebert, a Prince William Commonwealth attorney, who prosecuted Weeks and urged that he be sentenced to death. "The mother favors execution, and the two children oppose it. People have their own ideas."

Fate in the governor's hands

Richardson said he has filed no further court appeals and that the convicted cop killer's fate now lies with Gilmore. Richardson said he filed the second set of updated clemency petitions Friday, urging Gilmore to grant Weeks clemency because he has admitted responsibility and showed remorse. Richardson also said the jurors were confused into thinking they couldn't give Weeks a life sentence, and that former prison guards and a prison counselor are urging his life be spared. Police said that on Feb. 24, 1993, Cavazos was assigned to patrol Interstate 95 in Prince William County when he made a routine traffic stop near the southbound Potomac Mills exit ramp in Dale City. He had been a trooper since 1985. On probation for selling marijuana, Weeks was a passenger in a stolen car driven by his uncle, Louis Dukes. Weeks reportedly fired two 9 mm bullets at the trooper. Dukes was sentenced to life in prison plus 12 years but will become eligible for yearly parole review in 2005, according to the state Department of Corrections.

'The devil made me do it'

After he was found guilty of murder, Weeks testified in the mitigation aspect of the trial -- during which the jury had to decide whether to give him a death sentence. In explaining why he shot the officer, Weeks said it was as if an "evil spirit" willed him. "He basically said, 'The devil made me do it,'" Ebert said. Ebert said the gun Weeks used to kill Cavazos previously had been used to commit another murder and was given to Weeks to hold. "This case was every police officer's nightmare," Ebert said. "You pull someone over for a traffic violation and wind up being gunned down. Every officer can relate to that. This trooper was very understanding. He wasn't really a hard-nosed cop." In January, Weeks came within a vote of getting a new trial when the U.S. Supreme Court voted 5-4 to uphold the constitutionality of his conviction. Lawyers had argued that the judge's instructions to the jury were misunderstood, and that several jurors wanted to spare his life.

A remorseful killer?

Richardson is portraying Weeks as a remorseful man who has taken responsibility for the crime. He said Weeks, a former high school football star and "devout Christian," was at one time recruited for an athletic scholarship but instead chose not to go to college so he could support his then-pregnant girlfriend. The clemency petition submitted to Gilmore states that Weeks made a series of "awful decisions" that helped unravel his life and led to him stealing a car and killing the trooper. These included drug dealing and drug use. The National Black Police Association, a 35,000-member organization composed of minority law enforcement officers, also has called for Weeks' life to be spared.

Criminal Justice Legal Foundation - Amicus Briefs

CJLF Amicus Brief - Weeks v. Angelone (United States Supreme Court No. 99-5746)

QUESTIONS PRESENTED: In the penalty phase of a capital case (1) the trial judge gave a correct instruction which explained that the death sentence was not mandatory and that defendant's mitigating evidence must be considered, (2) a question form the jury indicated one ore more jurors did not understand, and (3) after giving defense counsel notice and an opportunity to be heard, the trial judge determined that the best clarification under the circumstances was to pinpoint the instruction and paragraph that answered the jury's question: (1) Is responding to the question in this manner within the trial judge's discretion?

"Weeks granted stay of execution; Ex-Seventy-First High Sports Star Killed a Virginia State Trooper." (Observer-Times Staff & Associated Press - Thursday, September 2, 1999)

The U.S. Supreme Court on Wednesday granted Lonnie Weeks Jr. of Fayetteville a stay of execution less than two hours before he was to be put to death for the murder of a Virginia state trooper. The court unanimously granted the stay shortly after 7 p.m.

Weeks, 27, a former basketball star at Seventy-First High School, was scheduled to die by injection at 9 p.m. for killing Trooper Jose M. Cavazos during a traffic stop on Feb. 24, 1993, along Interstate 95 in Prince William County. Weeks confessed hours later. The Rev. Bob West, Weeks’ minister, was with him at Greensville Correctional Center in Jarratt, Va., when he got word of the stay. Weeks was prepared to die, West said, but “he was ecstatic that he now can live to some point in time.”

The Supreme Court agreed to review just one question Weeks raised in his appeal: When jurors tell the judge they don’t understand instructions and ask whether they can consider a sentence less than death, even if one or more aggravating factors making a death sentence an option are found, does the Constitution require that the judge clarify that a death sentence is not mandatory and that mitigating factors also should be considered? The court likely will hear arguments in the case in December or January and issue a decision by late June. If Weeks prevails, he could get a new sentencing hearing. but his conviction would not be affected.

Cavazos’ two children had asked Gov. Jim Gilmore to spare Weeks’ life, putting them at odds with the trooper’s widow. Linda Cavazos said her adult children were entitled to their own views. “But I am strengthened by my husband’s memory and ... I want to see the punishment carried out,” she said. Attempts to reach Mrs. Cavazos after the ruling were unsuccessful. Correspondence between the Cavazos family and Weeks was attached to Weeks’ clemency petition to Gilmore. “Lonnie, I forgive you for what you have done. Unfortunately, your fate is out of my hands,” Leslie Cavazos-Almagia wrote Weeks in an Aug. 18 letter. In a 1998 letter to Mrs. Cavazos, Weeks wrote, “I am very sorry for all the pain I caused you and your family. I know sorry will not bring your husband back, but I truly am sorry and remorseful. (I) pray for you and your family every night.” The governor had not ruled on the petition when the high court granted the stay. Weeks’ lawyers could not be reached for comment.

Weeks was captain of his high school basketball team and won an athletic scholarship to Mount Olive College. He dropped out of school to support a son he had fathered the summer before his freshman year. In less than a year there was a second son. He began selling drugs and carrying a handgun. Weeks was returning home from a family gathering in Washington in a stolen car driven by his uncle when Cavazos, 50, pulled them over for speeding on southbound I-95 near Dale City. During his trial Weeks testified that “as I stepped out of the car, it was just like something just took over me that I couldn’t understand ... I felt like it was evil, evil spirit or something. That’s how I feel. That’s the way I describe it.” He shot Cavazos six times.

The gun used in the slaying was linked to the killing of a soldier in Cumberland County a month earlier. Norman Fletcher Howell Jr. pleaded guilty to the killing of George Mallet Jr. and an unrelated sexual assault. He was given two concurrent life sentences. Before Howell was arrested, he gave the murder weapon to his cousin. According to Fayetteville police reports, Howell’s cousin didn’t want it and gave it to Weeks.

Weeks v. Com., 450 S.E.2d 379 (Va. 1994) (Direct Appeal).

On February 24, 1993, Virginia State Trooper Jose M. Cavazos was shot and killed by defendant Lonnie Weeks, Jr., in Prince William County. Subsequently, defendant was indicted for the felonious, willful, deliberate, and premeditated homicide of the law enforcement officer, when such killing was for the purpose of interfering with the performance of the trooper's official duties. Code § 18.2-31(6). Defendant also was charged with grand larceny of a motor vehicle, Code § 18.2-95, and use of a firearm in the commission of murder, Code § 18.2-53.1.

Following several pretrial hearings, including a hearing on defendant's motion to suppress his confession, defendant was tried by a single jury during five days in October 1993. As the trial began, defendant pled guilty to the grand larceny and firearm charges. The court subsequently sentenced defendant to imprisonment for ten-year and three-year terms respectively on those charges.

The jury found the defendant guilty of the capital murder charge and, during the second phase of the bifurcated capital proceeding, the jury fixed the defendant's punishment at death for the capital offense based upon the vileness predicate of the capital murder sentencing statute. Code § 19.2-264.4. Later, the trial court considered a probation officer's report and heard testimony from the officer relevant to punishment. The court then sentenced the defendant to death for the capital murder. The death sentence is before us for automatic review under Code § 17-110.1(A), see Rule 5:22. As required by statute, we will consider not only the trial errors enumerated by the defendant but also whether the sentence of death was imposed under the influence of passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor, and whether the sentence is excessive or disproportionate to the penalty imposed in similar cases. Code § 17-110.1(C).

There is no conflict about any relevant fact in the case. In early February 1993, defendant, who was age 20, a North Carolina resident, and on probation for a 1992 drug conviction, participated in the burglary of a residence in the Fayetteville, North Carolina area. During the course of that crime, defendant obtained a set of keys to a 1987 Volkswagen Jetta automobile parked at the residence, and stole the vehicle. Later that month, defendant drove the vehicle to Washington, D.C., intending to sell it or trade it for drugs. Defendant carried in the vehicle a Glock Model 17, nine millimeter, semi- automatic pistol loaded with hollow-point bullets. According to the testimony, the bullets were designed for police use, not target practice or hunting; this type of bullet is referred to as a "man-stopper."

During the late evening of February 23, defendant was riding as a passenger in the vehicle being driven by his uncle, 21-year-old Lewis J. Dukes, Jr., a resident of the District of Columbia. The pair was travelling en route from Washington to Richmond southbound on Interstate Route 95. Around midnight, Trooper Cavazos was operating radar from his marked police vehicle parked in the highway medium monitoring southbound traffic. The Volkswagen driven by Dukes passed the trooper's position at a high rate of speed. The officer activated his vehicle's emergency lights and proceeded to chase the vehicle occupied by defendant. After travelling a brief distance, and passing other vehicles by driving on the right shoulder of the highway, Dukes brought the car to a stop on the Dale City exit ramp, in a dark, remote area.

The trooper pulled his patrol car to a stop behind the Volkswagen, which he approached on foot on the driver's side. Upon the officer's request, Dukes alighted and was standing toward the left rear of the Volkswagen when the trooper asked defendant to step out of the vehicle.

Defendant complied with the officer's request and alighted on the right side of the vehicle as the trooper was near the left side. As defendant left the vehicle he was carrying the fully loaded pistol. He then fired at least six bullets at the officer, two of which entered his body beside the right and left shoulder straps of the protective vest the trooper was wearing. The officer was immediately rendered unconscious and fell to the pavement, dying within minutes at the scene with his police weapon in its "snapped" holster.

Defendant, with Dukes as a passenger, then drove the Volkswagen from the scene and parked it on the lot of a nearby service station. Defendant returned to the scene of the crime on foot and retrieved Dukes' District of Columbia driver's license that had been dropped on the pavement. Defendant rejoined Dukes, and they were found by police shortly thereafter in the parking lot of a nearby motel.