Executed September 28, 2011 07:14 p.m. EST by Lethal Injection in Florida

37th murderer executed in U.S. in 2011

1271st murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Florida in 2011

70th murderer executed in Florida since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(37) |

|

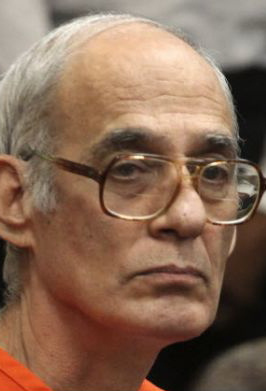

Manuel Valle H / M / 27 - 61 |

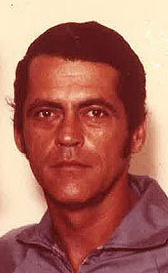

Louis Pena OFFICER H / M / 41 |

08-04-81 03-16-88 |

Citations:

Valle v. State, 394 So.2d 1004 (Fla. 1981) (Direct Appeal-Reversed).

Valle v. State, 474 So.2d 796 (Fla. 1985) (Direct Appeal-Affirmed).

Valle v. State, 581 So.2d 40 (Fla. 1991) (Direct Appeal-Affirmed).

Valle v. State, 778 So.2d 960 (Fla. 2001) (PCR).

Valle v. Secretary, 459 F.3d 1206 (11th Cir. 2006) (Habeas).

Final / Special Meal:

Fried chicken breast, white rice, garlic toast, peach cobbler and a Coca-Cola.

Final Words:

None.

Internet Sources:

Florida Department of Corrections

DOC#: Number: 853220Current Prison Sentence History:

Offense Date: 11/04/71

Offense: Forgery / Uttering (2 Counts)

Sentence Date: 04/25/78

County: Miami

Case No.: 7109555

Prison Sentence Length: 5 YR

Offense Date: 08/29/77

Offense: Grand Theft Notor Vehicle

Sentence Date: 05/12/78

County: Miami

Case No.: 7805281

Prison Sentence Length: 5 YR

Offense Date: 04/02/78

Offense: First Degree Murder

Sentence Date: 05/12/78

County: Miami

Case No.: 7805281

Prison Sentence Length: DEATH

Offense Date: 04/02/78

Offense: Attempted Murder

Sentence Date: 05/12/78

County: Miami

Case No.: 7805281

Prison Sentence Length: 30 YR

Offense Date: 04/02/78

Offense: Possession of Illegal Weapon

Sentence Date: 05/12/78

County: Miami

Case No.: 7805281

Prison Sentence Length: 5 YR

"Manuel Valle executed, 33 years after killing police officer," by Jackie Alexander. (September 28, 2011 at 10:01 pm)

RAIFORD — The doctor checked the man's pulse. Execution team warden Timothy Cannon then nodded and picked up the phone. “The sentence of the State of Florida versus Manuel Valle was carried out at 7:14 p.m.,” Cannon said. More than 33 years after being convicted of killing a Coral Gables police officer, Manuel Valle, 61, was executed Wednesday night, despite a last-minute appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States.

Jeneane Skeen and Lisa Pena hugged and cried after the brown curtain to the death chamber closed. They're daughters of Louis Pena, who was shot and killed by Valle on April 2, 1978, during a traffic stop. Valle underwent several trials and execution dates before Wednesday.

Skeen said her family endured trial after trial stoically — “because the murderer has rights.” “This is not justice,” she said. “For 33 years, people have asked us if the death penalty will give us closure … We finally got revenge on the low-life piece of human waste that murdered our father.” Skeen was 13 years old when her father was killed. She and Lisa Pena wore pins bearing their father's face. “We wanted him to look out and see we haven't forgotten,” she said. “We've been there since day one of the hearing and we'll be there to the end.”

Valle, who had been on death watch since Gov. Rick Scott signed a death warrant on June 30, was “very calm” and “polite and compliant” leading up to his execution, said Department of Corrections spokeswoman Gretl Plessinger. Valle ate a final dinner of fried chicken breast, white rice, garlic toast, peach cobbler and a Coca-Cola.

He did not open his eyes while laying on a gurney with a white sheet draped over him. Cannon asked if he had last words. “No, I don't,” Valle said. Soon after the administration of the first drug, Valle looked to Cannon. His words were not audible to the witnesses, but Plessinger reported that he asked, “Do I need to start counting backwards again?” Several minutes later, he laid with his mouth slack-jawed while Cannon periodically checked his breathing. Valle was then pronounced dead by the doctor nearly 20 minutes after the start of the procedure.

Valle was the first Florida prisoner executed using a new lethal mix of drugs. Previously, officials had used sodium thiopental for executions. Now, executions are administered using pentobarbital, even though concerns have been voiced that pentobarbital prolongs the death process and causes pain. According to a letter sent to Gov. Scott by Department of Corrections Secretary Kenneth Tucker, the drug is “compatible with evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society, the concepts of the dignity of man, and advances in science, research, pharmacology and technology.”

Benetta Standly, director of the Northeast Florida region of the American Civil Liberties Union, disagreed. “We oppose the death penalty, because we believe it's a violation of the Eighth Amendment of cruel and unusual punishment,” she said. “I'm here to stand with Floridians and say it's not the state's right to take a person's life.”

Plessinger said 397 inmates are on Death Row at two different facilities. Several inmates have been on Death Row longer than Valle, including Norman Parker, who has been there since 1967. According to the department, the average length of stay on Death Row is nearly 13 years. Both the Florida Supreme Court and the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals denied claims earlier this month that the new drug amounted to cruel and unusual punishment.

Earlier Wednesday, there was confusion outside the prison after the Miami Herald inadvertently published premature news of Valle's death. Valle, family members of Pena and media waited for three hours before the death sentence was carried out. Just after 6:30 p.m., news was delivered that the Supreme Court decided not to intervene.

Victor Cabrera, a member of the Coral Gables police department, said the wait was another inconvenience in a long process. “We had no doubt that it was going to happen,” he said. Skeen said she was willing to wait for her father's rights to be restored with the death of Valle. “I would have waited all night until they got it done,” she said.

"Florida executes Manuel Valle for the killing of a Coral Gables police officer in 1978," by Patricia Mazzei. (9/28/11)

STARKE -- Manuel Valle was executed by lethal injection Wednesday at Florida State Prison for fatally shooting a Coral Gables police officer and wounding another one 33 years ago during a traffic stop. His execution had been scheduled for 4 p.m., but the U.S. Supreme Court delayed it for almost three hours to review — and ultimately reject — Valle’s last-ditch petition to block it.

Valle was convicted in 1978 for murdering Officer Louis Pena, who had pulled Valle over for running a red light. Valle, then 27 years old and driving a stolen Camaro, shot Pena, 41, in the neck and backup Officer Gary Spell in the back before fleeing. He was caught two days later.

Amid retrials and repeated hearings, Valle spent more than three decades on Death Row, one of the longest-serving condemned inmates in Florida. Gov. Rick Scott signed Valle’s death warrant — the governor’s first — on June 30. But the courts delayed it twice, pushing back the execution by eight weeks.

When Valle was declared dead at 7:14 p.m. Wednesday, two of Pena’s daughters, Jeneane Skeen of Fort Myers and Lisa Pena of Miami, tearfully hugged in the front row center of the witness chamber. “At this point, it’s beyond closure and it’s beyond justice,” Skeen, surrounded by a dozen relatives and now-retired Gables cops, told reporters after the execution. “We finally got revenge on the lowlife piece of human waste that murdered our father.” Valle’s family, which did not witness the execution, declined to speak to reporters through his lawyers. One of his lawyers and a Catholic chaplain did sit in the witness chamber, next to Pena’s daughters.

Valle became the first Florida inmate executed using pentobarbital, a sedative, as the first of three drugs in the state’s lethal injections. His lawyers had questioned the drug change from the previous anesthetic, sodium thiopental, saying pentobarbital was untested to render an inmate unconscious.

For Valle, the day began when he awoke at 5:32 a.m. He visited through a glass barrier with three sisters, two nieces, a brother-in-law, and his daughter, Rebecca, who was 2 years old when her father was arrested. Later, Rebecca, one of Valle’s sisters and a niece spent an hour with him — with physical contact. By noon, Valle was alone. He showered and dressed in black trousers and a white shirt. He ate most of his last meal: fried chicken breast, white rice, garlic toast and peach cobbler. He drank a Coke. He met with the chaplain. He took diazepam to ease his nerves. And then he sat in his cell and waited.

About 3:30 p.m., the nation’s high court issued its delay to consider an appeal from Valle’s lawyers, who argued Valle did not receive an appropriate shot at clemency and should be granted a stay of execution. After almost three hours, the court denied the stay. The execution was rescheduled for 6:55 p.m. When the brown curtain of the execution chamber went up at 6:56 p.m., Valle, who refused a second anti-anxiety drug, lay still with his eyes closed, occasionally adjusting his feet and legs. His arms, about 45 degrees from his body, were restrained by brown straps. A white sheet covered him from the neck down. The warden, Timothy Cannon, asked Valle whether he had any last words. “No, I don’t,” Valle said.

The execution began at 6:58 p.m. After the pentobarbital was administered, Valle opened his eyes wide, shifted his feet, turned to the warden and said something inaudible to the witnesses. Valle then tilted his head slightly to the left and closed his eyes. For a few moments, he blew air out his mouth as his lips quivered. By 7:01 p.m., Valle no longer appeared to be moving. His mouth, initially parted on the right side, slowly opened. The witness chamber remained silent. At 7:13 p.m., a man in a white coat with a red stethoscope around his neck entered the room, listened for Valle’s heartbeat and checked his eyes. The warden spoke briefly into a telephone on the wall, which had maintained an open line to the governor’s office since 3:25 p.m. “The sentence of the state of Florida vs. Manuel Valle was carried out at 7:14 p.m.,” Warden Cannon told the witness room. The brown curtain came down.

Valle executed for killing Coral Gables police officer. (Associated Press Updated: September 28, 2011 - 9:37 PM)

RAIFORD -- A man convicted of killing a Coral Gables police officer during a traffic stop 33 years ago has been executed at the Florida State Prison. Manuel Valle, 61, was given a lethal injection and pronounced dead at 7:14 p.m. Wednesday, the governor's office reported.

The process began at 6:56 p.m. when a curtain opened, allowing family members of slain officer Louis Pena and others in a witness room to see Valle with a white sheet placed over him. His arms and face were exposed. He appeared calm and relaxed. When the first drug was administered, Valle raised his feet, turned his head toward the team warden and said something that could not be heard in the witness room. He then yawned, placed his head back down, closed his eyes and made movements with his mouth as if he was snoring. At 7:04 p.m. the team warden, Timothy Cannon, lightly tapped Valle. A doctor walked into a room at 7:13 p.m. and examined Valle. By 7:14 p.m., the team warden was informed that Valle was dead.

Jeneane Skeen, who was 13 when her father was killed, sat in the front row, occasionally blinking rapidly and tightened her lips as she watched Valle. Once Valle was pronounced dead, Skeen held back tears as she smiled and hugged her sister, Lisa Pena. Other relatives consoled each other. Afterward, Skeen read a statement criticizing the process that allowed Valle to remain alive 33 years after the killing, saying Valle's rights were put before her father's. “This is not justice, for 33 years people have asked us if the death penalty will really bring us closure, at this point it's beyond closure and it's beyond justice. We finally got revenge on the lowlife piece of human waste that murdered our father. Officer Louis Pena finally got his rights.”

Valle was the first Florida inmate to be executed using the state's newly revised mix of lethal drugs, a concoction that faced legal challenges which twice delayed carrying out the death sentence.

Valle fatally shot Pena on April 2, 1978, after Pena stopped Valle for a traffic violation while driving a stolen car, according to court records. He also shot fellow officer Gary Spell, who survived and then testified against Valle in court. Spell testified that when he arrived the day of the shooting, Valle was seated in Pena's patrol car. As Pena was checking the license plate of the car Valle had been driving, Valle walked back to the car, reached inside and then walked back and fired a single shot at Pena, the records indicate. He then fired two shots at Spell, who was saved by his bulletproof vest, the records show. Valle fled and was arrested two days later.

A 4 p.m. EDT execution was initially planned, but Gov. Rick Scott's office said it was delayed by an unsuccessful late bid before the U.S. Supreme Court. Southern prisons had seen a series of executions in recent days. On Sept. 21, Georgia executed Troy Davis for the 1989 shooting death of a policeman, despite an international outcry and claims he was innocent. The same day, Texas executed white supremacist Lawrence Russell Brewer for the 1998 dragging death of James Byrd Jr., a black man. A day later, Alabama executed Derrick O. Mason for the shooting death of a store clerk in a 1994 robbery.

Pena's son, also named Louis Pena, stood outside the Florida prison hours before the execution and spoke of his reaction to the unfolding events. “It means finally, my dad's soul is put to rest after 33 years,” said Pena, who was 19 when his father died and is now 53. “He killed a cop in cold blood … He killed a cop and lived 33 years. This man lived another lifetime after taking a life,” Pena added. Inside Skeen and Lisa Pena were wearing buttons with their father's face and name on them. “We wanted him to look out and see him,” Skeen said of Valle. “We really hope he saw us.”

Valle was initially sentenced to die in 1981, but the state Supreme Court ordered a new trial that year. He was again convicted and sentenced to die, but the U.S. Supreme Court vacated that death sentence in 1986. Another jury recommended the death sentence anew in 1988.

Since Scott signed Valle's death warrant, the original Aug. 2 execution date has been delayed twice — once by the Florida Supreme Court and then by the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Atlanta. Both courts later rejected arguments by Valle's lawyers that the new drug mix would cause him pain and constitute cruel and unusual punishment. The state previously used sodium thiopental to render condemned prisoners unconscious before the second and third drugs, pancuronium bromide and potassium chloride, were injected. But sodium thiopental is no longer made in the US and now Florida and other states are substituting it with pentobarbital, marketed as Nembutal. Eighteen people have been executed nationwide using pentobarbital as a replacement anesthetic since Oklahoma became the first last year.

Valle's warrant was the first Scott signed as governor. It comes in a year when there have been an unusually high number of police officers killed in Florida. Six officers have been fatally shot in 2011, according to the Officer Down Memorial Page, a website that tracks officer deaths nationally. That's already more than each of the last three years and one shy of the seven officers killed by gunfire in 2007.

"Florida executes man for 1978 police killing," by Michael Peltier. (Thu Sep 29, 2011 10:44am EDT)

TALLAHASSEE, Fla (Reuters) - Florida on Wednesday executed a man convicted of killing a Coral Gables police officer in 1978, the first inmate put to death since the state changed its lethal injection procedure. Manuel Valle, 61, was pronounced dead by Department of Corrections officials at 7:14 p.m. local time, shortly after being administered a series of lethal drugs at Florida State Prison near Starke.

Valle, who spent 30 years on Florida's death row, was the first inmate executed since Republican Governor Rick Scott took office in January. Florida's governor signs the death warrant for a condemned inmate. Valle was the 37th person put to death in the U.S. this year. His execution was delayed for about three hours on Wednesday as his attorney petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court for a stay, arguing unsuccessfully that executing Valle after three decades on death row was both cruel and unusual.

A corrections spokeswoman said Valle was served a last meal of fried chicken, white rice, garlic toast, peach cobbler and a Coke. He did not make a final statement, but the deceased officer's wife issued one. "Even though I believe this execution was just, I don't believe I will ever have complete closure," said Lana Pena Kemmerer.

The Cuban-born Valle was 27 when he shot and killed Coral Gables Officer Louis Pena after being pulled over for running a red light in a stolen car in April 1978. As the officer checked the license tag, Valle retrieved a gun from the stolen vehicle and fatally shot Pena in the neck. When a backup officer arrived, Valle shot him too. Protected by a bulletproof vest, Officer Gary Spell survived and testified at Valle's trial.

Convicted and first sentenced to death in 1981, Valle avoided execution for decades due to numerous appeals, reversals and re-hearings that wound all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. This was his third death warrant.

Valle was scheduled to die on August 2, but the execution was again postponed to allow for a hearing on his concerns about the use of a new sedative by the state. Earlier this year, Florida prison officials substituted one of the drugs used in the three-drug lethal injection protocol after its Dutch manufacturer stopped making the product to protest its use in executions.

In late August, the Florida Supreme Court unanimously rejected arguments by Valle's attorneys that the substitution of pentobarbital into the procedure would allow their client to remain conscious, thus subjecting him to undue pain and suffering when the next two drugs were administered. In an opinion that cleared the way for future executions using pentobarbital, the court said it found no credible evidence that administering the drug at 10 times the normal sedation dosage would allow Valle to remain conscious. By itself, the drug is considered lethal at the dosage used by the Department of Corrections. It is followed by other medications that paralyze the lungs and cause a heart attack.

Valle was the 70th inmate executed in Florida since the reinstatement of the death penalty in 1976 and the first since February 2010.

Florida Commission on Capital Cases

VALLE, Manuel (H/M)

DC # 853220

DOB: 05/21/50

Eleventh Judicial Circuit, Dade County, Case #78-5281-A

Sentencing Judge, Trial I: The Honorable Ellen J. Morphonios

Sentencing Judge, Trial II: The Honorable James R. Jorgenson

Sentencing Judge, Resentencing: The Honorable Norman S. Gerstein

Attorneys, Trial I: David Goodhart & Vance Carr

Attorneys, Trial II: Elliot Scherker & Leonard Rosenbaum – Assistant Public Defenders

Attorneys, Resentencing: Michael Zelman & Elliot Scherker – Assistant Public Defenders

Attorneys, Direct Appeal I: Elliot Scherker & Karen Gottlieb – Assistant Public Defenders

Attorney, Direct Appeal II: Michael Zelman – Assistant Public Defender

Attorneys, Direct Appeal, Resentencing: Louis Jepeway & Michael Mello

Attorney, Collateral Appeals: Suzanne Myers – CCRC-S

Date of Offense: 04/02/78

Date of Sentencing, Trial I: 05/10/78

Date of Sentencing, Trial II: 08/04/81

Date of Resentencing: 03/16/88

Circumstances of Offense:

Manuel Valle was convicted and sentenced to death for the murder of Officer Louis Pena of the Coral Gables Police Department. Officer Gary Spell, who was at the scene, recalled the following events at trial: On 04/02/78, Officer Louis Pena pulled over Manuel Valle and his codefendant, Felix Ruiz, for a traffic violation. Upon arriving at the scene, Officer Spell observed Valle sitting in the patrol car with Officer Pena. When Officer Pena initiated a registration check on the stolen car that Valle was driving, Valle exited the patrol car and walked back over to his own vehicle. Valle retrieved a gun from his car, returned to the patrol car, and fired one shot at Officer Pena, killing him. Valle then turned and fired two shots at Officer Spell before fleeing the scene. Valle was apprehended two days later in Deerfield Beach.

Codefendant Information: Codefendant Felix Ruiz was charged as an accessory after the fact and sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment on 06/20/78.

Prior Incarceration History in the State of Florida:

Offense Date: 11/04/71

Offense: Forgery / Uttering (2 Counts)

Sentence Date: 04/25/78

County: Miami

Case No.: 7109555

Prison Sentence Length: 5 YR

Offense Date: 08/29/77

Offense: Grand Theft Notor Vehicle

Sentence Date: 05/12/78

County: Miami

Case No.: 7805281

Prison Sentence Length: 5 YR

Trial I Summary:

04/04/78 Defendant arrested.

04/13/78 Defendant indicted on the following:

Count I: First-Degree Murder

Count II: Attempted First-Degree Murder

Count III: Possession of a Firearm/Convicted Felon

Count IV: Grand Theft Auto

04/14/78 Defendant arraigned by the trial court of Dade County, 11th Circuit.

05/10/78 The jury found the defendant guilty on Counts I, II, & III.

05/10/78 The jury voted by majority for the death penalty.

05/10/78 At Trial I, the defendant was sentenced as follows:

Count I: First-Degree Murder - Death

Count II: Attempted First-Degree Murder – 30 years

Count III: Possession of a Firearm/Convicted Felon – 15 years

02/26/81 The Florida Supreme Court reversed Valle’s convictions and sentence and remanded for a new trial.

Trial II Summary:

07/31/81 At Trial II, Valle was convicted on all counts charged in the indictment.

08/01/81 The jury, by a 9 to 3 majority, voted for the death penalty.

08/04/81 At Trial II, the defendant was sentenced as follows:

Count I: First-Degree Murder - Death

Count II: Attempted First-Degree Murder – 30 years

Count III: Possession of a Firearm/Convicted Felon – 5 years

01/05/87 The Florida Supreme Court remanded for resentencing before a new jury.

Resentencing Summary:

02/29/88 The jury, by an 8 to 4 majority, voted for the death penalty.

03/16/88 The defendant was resentenced as follows:

Count I: First-Degree Murder - Death

Count II: Attempted First-Degree Murder – 30 years

Count III: Possession of a Firearm/Convicted Felon – 5 years

Appeal Summary:

Florida Supreme Court – Direct Appeal (Trial I)

FSC #54,572 394 So. 2d 1004

07/07/78 Appeal filed.

02/26/81 FSC reversed Valle’s convictions and sentence and remanded for a new trial.

Florida Supreme Court – Direct Appeal (Trial II)

FSC #61,176 474 So. 2d 796

09/23/81 Appeal filed.

07/11/85 FSC affirmed the convictions and sentence of death.

09/17/85 Rehearing denied.

United States Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Certiorari

USSC #85-6063 476 U.S. 1102

12/06/85 Petition filed.

05/05/86 Certiorari granted in light of Skipper v. South Carolina, regarding the admissibility of model prisoner testimony.

Florida Supreme Court – Direct Appeal (On Remand from USSC)

FSC #61,176 502 So. 2d 1225

05/05/86 Certiorari granted by the USSC and remanded to the FSC.

01/05/87 FSC reversed the death sentence and remanded for a new sentencing hearing before a new jury.

Florida Supreme Court – Direct Appeal (Resentencing)

FSC #72,328 581 So. 2d 40

04/27/88 Appeal filed.

05/02/91 FSC affirmed the convictions and sentence of death.

07/05/91 Rehearing denied.

08/05/91 Mandate issued.

United States Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Certiorari

USSC #91-5974 502 U.S. 986

10/01/91 Petition filed.

12/02/91 Petition denied.

State Circuit Court – 3.850 Motion (I)

CC #78-5281

04/05/93 Motion filed.

08/19/93 Motion dismissed without prejudice in order to file a legally sufficient motion.

State Circuit Court – 3.850 Motion (II)

CC #78-5281

12/01/93 Motion filed.

08/31/94 Motion denied.

Florida Supreme Court – 3.850 Appeal

FSC #88,203 705 So. 2d 1331

06/07/96 Appeal filed.

12/11/97 FSC affirmed in part, reversed in part, and remanded regarding Valle’s IC claim.

State Circuit Court – 3.850 Motion (On Remand from FSC)

CC #78-5281

12/11/97 FSC remanded the motion for an evidentiary hearing regarding Valle’s claim of ineffective assistance of counsel.

10/19/98 Motion denied.

Florida Supreme Court – 3.850 Appeal

FSC #94,754 778 So. 2d 960

01/25/99 Appeal filed.

01/18/01 FSC affirmed the denial of Valle’s 3.850 Motion.

03/12/01 Rehearing denied.

04/17/01 Mandate issued.

Florida Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

FSC #01-2865 837 So. 2d 905

12/31/01 Petition filed.

08/29/02 Petition denied.

11/12/02 Rehearing denied.

Florida Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

FSC #03-298 859 So.2d 516

02/19/03 Petition filed.

06/24/03 Petition denied.

10/15/03 Rehearing denied.

United States District Court, Southern District – Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

USDC# 03-20387

02/21/03 Petition filed.

09/13/05 Petition denied.

United States Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Certiorari

USSC #03-8609 124 S. Ct. 1720

01/13/04 Petition filed.

03/29/04 Petition denied.

United States Court of Appeals, 11th Circuit – Habeas Appeal

USCA# 05-15724 459 F. 3d 1206

10/11/05 Appeal filed.

08/11/06 USCA affirmed the denial of the petition.

02/27/07 Mandate issued.

United States Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Certiorari

USSC# 07-5505 459 F.3d 1206

07/16/07 Petition filed.

10/01/07 Petition denied.

Factors Contributing to the Delay in the Imposition of the Sentence:

The execution of Valle’s death sentence has been delayed by the numerous remands in his appellate history. His case was first remanded for retrial following a three-year Direct Appeal. Following his retrial and the affirmation of his convictions and sentence by the Florida Supreme Court during his Direct Appeal, the United States Supreme Court granted certiorari. The Florida Supreme Court then remanded the case for resentencing before a new jury in 1987. In 1997, 10 years later, the State Circuit Court denied Valle’s second 3.850 Motion; however, the Florida Supreme Court remanded the motion on appeal for an evidentiary hearing regarding Valle’s claim of ineffective assistance of counsel.

Case Information:

Manuel Valle filed a Direct Appeal in the Florida Supreme Court on 07/07/78. In that appeal he argued that his Sixth and Fourteenth Amendment rights had been violated by the expedited nature of his trial. Valle contended that his right to adequate preparation time and right to effective assistance of counsel were violated when his case went to trial only 24 days after his arraignment. Florida Supreme Court agreed and stated:

We find that requiring this appellant to go to trial within twenty-four days after arraignment resulted in a denial of effective assistance of counsel where defense counsel, even though diligent, had no opportunity to make proper inquiry into the appellant’s mental condition or to despose twenty-four of that fifty-nine witnesses named by the state pursuant to the Florida criminal discovery rules.

The Florida Supreme Court also found that the trial judge’s decision to allow Valle’s case to proceed so hurriedly was an abuse of discretion. As such, the high court reversed the convictions and sentence of death, and remanded for a retrial.

Valle was again convicted of the murder of Officer Louis Pena and sentenced to death on 08/04/81. He filed a Direct Appeal in the Florida Supreme Court arguing that his confession should have been suppressed because it was obtained in violation of his Miranda rights, that the trial court erred in allowing under-representation of minorities in the jury selection and that a mistrial should have been granted when the prosecutor for the State prejudicially commented on Valle’s right to remain silent. Regarding the penalty phase of the trial, Valle contended that the trial judge erred in excusing a prospective juror for cause and that the court erred in allowing the prosecutor for the State to make improper comments during closing arguments. Valle also challenged the instruction, consideration, and application of aggravating and mitigating circumstances in his case. Specifically, Valle argued that the trial court erred in omitting mitigating evidence that he would be a model prisoner if spared the death penalty. The Florida Supreme Court affirmed Valle’s convictions and sentence of death on 07/11/85.

Valle then filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari in the United States Supreme Court, which was granted on 05/05/86. The Supreme Court vacated the death sentence and remanded to the Florida Supreme Court for further consideration of Valle’s case under the dictates of Skipper v. Carolina[1].

On remand from the United States Supreme Court, the Florida Supreme Court found that testimony regarding Valle’s potential future behavior as a model prisoner should have been considered by the jury during the penalty phase of the trial. As such, the Florida Supreme Court remanded for resentencing before a new jury on 01/05/87.

Valle was resentenced to death on 03/16/88, after which he filed a Direct Appeal in the Florida Supreme Court. In that appeal, he argued the improper cross-examination of defense experts who were testifying as to Valle’s prison behavior. The defense’s presentation of Skipper testimony regarding the admissibility of model prison behavior, gave the prosecution the opportunity to scrutinize Valle’s prison behavior on cross-examination. Valle also challenged the application of the aggravating factor that the victim was a law enforcement officer engaged in his official duties and the application of the cold, calculated, and premeditated (CCP) aggravating factor. He also argued that the prosecutor improperly presented victim impact evidence. The Florida Supreme Court affirmed Valle’s death sentence on 05/02/91. Valle then filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari in the United States Supreme Court, which was denied on 12/02/91.

Valle next filed a Motion to Vacate Judgment and Sentence (3.850) in the State Circuit Court, which was subsequently dismissed without prejudice in order to file a legally sufficient motion. Valle then filed a second 3.850 Motion in the State Circuit Court, which argued 20 claims. Following a Huff hearing, the judge denied Valle’s 3.850 Motion without an evidentiary hearing. He steadfastly filed an appeal of that decision in the Florida Supreme Court. In that appeal, Valle claimed he received ineffective assistance of counsel. Valle argued that his counsel was ineffective for failing to move for the disqualification of his resentencing judge. Judge Norman Gerstein allegedly kissed the victim’s widow in an offer of sympathy and fraternized with the victim’s friends in front of the jury. Valle also contended that his counsel was ineffective for presenting Skipper evidence during his resentencing proceedings, which allowed the State to bring up that Valle had attempted an escape from prison between the time his death sentence was reversed and the resentencing. Valle claimed that his counsel erroneously presented the Skipper evidence because they thought they had to, since his earlier sentence reversal was based on the exclusion of such evidence. Valle contended that without the defense’s presentation of the Skipper evidence, the State would have been unable to present rebuttal evidence of his escape attempt, and the jury may not have recommended death. The Florida Supreme Court affirmed the denial of Valle’s 3.850 Motion in part, reversed the denial in part, and remanded to the State Circuit Court for an evidentiary hearing on Valle’s claims of ineffective assistance of counsel.

Following an evidentiary hearing on Valle’s claims of ineffective assistance of counsel, the State Circuit Court again denied his 3.850 Motion. Valle then filed an appeal in the Florida Supreme Court. The high court noted that Valle’s defense did know that they were not required to present Skipper evidence. They chose to present evidence of present non-violent prison behavior, instead of past or future behavior as a tactical move in the hopes of preventing the State from presenting rebuttal evidence about Valle’s past prison misconduct. As such, the Florida Supreme Court affirmed the denial of Valle’s 3.850 Motion.

Valle next filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus in the Florida Supreme Court on 12/31/01, which was denied on 08/29/02. Valle filed another Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus in the Florida Supreme Court on 02/19/03, which was denied on 06/24/03. Rehearing was denied on 10/15/03. On 02/21/03, Valle filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus to the United States District Court, Southern District. The petition was denied on 09/13/05 Valle filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari with the United States Supreme Court on 01/13/04. The petition was denied on 03/29/04.

On 10/11/05, Valle filed a Habeas Appeal in the United States Court of Appeals, 11th Circuit. The USCA affirmed the denial of Valle’s Petition of Writ of Habeas Corpus on 08/11/06, and a mandate was issued on 02/27/07. On 07/16/07, Valle filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari with the United States Supreme Court. This petition was denied on 10/01/07.

On April 2, 1978, Officer Louis Pena of the Coral Gables Police Department was on patrol when he stopped Manuel Valle and Felix Ruiz for running a red light. The car was stolen. The events that followed were witnessed by Officer Gary Spell, also of the Coral Gables Police Department. Officer Spell testified that when he arrived at the scene, Valle was sitting in the patrol car with Officer Pena. Shortly thereafter, Spell heard Pena use his radio to run a license check on the car Valle was driving. According to Spell, Valle then walked back to his car and reached into it, approached Officer Pena and fired a single shot at him, which resulted in his death. Valle also fired two shots at Spell and then fled. He was picked up two days later in Deerfield Beach. Valle provided a detailed confession of killing Officer Pena and shooting at Officer Spell.

Following his jury trial, Valle was also found guilty of the attempted first-degree murder of Spell and after a non-jury trial, he was found guilty of possession of a firearm by a convicted felon. Louis Pena had been on the police force for 12 years and was married with four children; a son and three daughters.

2. Robert Sullivan, 36, died in the electric chair Nov. 30, 1983, for the April 9, 1973, shotgun slaying of Homestead hotel-restaurant assistant manager Donald Schmidt.

3. Anthony Antone, 66, executed Jan. 26, 1984, for masterminding the Oct. 23, 1975, contract killing of Tampa private detective Richard Cloud.

4. Arthur F. Goode III, 30, executed April 5, 1984, for killing 9-year-old Jason Verdow of Cape Coral March 5, 1976.

5. James Adams, 47, died in the electric chair on May 10, 1984, for beating Fort Pierce millionaire rancher Edgar Brown to death with a fire poker during a 1973 robbery attempt.

6. Carl Shriner, 30, executed June 20, 1984, for killing 32-year-old Gainesville convenience-store clerk Judith Ann Carter, who was shot five times.

7. David L. Washington, 34, executed July 13, 1984, for the murders of three Dade County residents _ Daniel Pridgen, Katrina Birk and University of Miami student Frank Meli _ during a 10-day span in 1976.

8. Ernest John Dobbert Jr., 46, executed Sept. 7, 1984, for the 1971 killing of his 9-year-old daughter Kelly Ann in Jacksonville..

9. James Dupree Henry, 34, executed Sept. 20, 1984, for the March 23, 1974, murder of 81-year-old Orlando civil rights leader Zellie L. Riley.

10. Timothy Palmes, 37, executed in November 1984 for the Oct. 19, 1976, stabbing death of Jacksonville furniture store owner James N. Stone. He was a co-defendant with Ronald John Michael Straight, executed May 20, 1986.

11. James David Raulerson, 33, executed Jan. 30, 1985, for gunning down Jacksonville police Officer Michael Stewart on April 27, 1975.

12. Johnny Paul Witt, 42, executed March 6, 1985, for killing, sexually abusing and mutilating Jonathan Mark Kushner, the 11-year-old son of a University of South Florida professor, Oct. 28, 1973.

13. Marvin Francois, 39, executed May 29, 1985, for shooting six people July 27, 1977, in the robbery of a ``drug house'' in the Miami suburb of Carol City. He was a co-defendant with Beauford White, executed Aug. 28, 1987.

14. Daniel Morris Thomas, 37, executed April 15, 1986, for shooting University of Florida associate professor Charles Anderson, raping the man's wife as he lay dying, then shooting the family dog on New Year's Day 1976.

15. David Livingston Funchess, 39, executed April 22, 1986, for the Dec. 16, 1974, stabbing deaths of 53-year-old Anna Waldrop and 56-year-old Clayton Ragan during a holdup in a Jacksonville lounge.

16. Ronald John Michael Straight, 42, executed May 20, 1986, for the Oct. 4, 1976, murder of Jacksonville businessman James N. Stone. He was a co-defendant with Timothy Palmes, executed Jan. 30, 1985.

17. Beauford White, 41, executed Aug. 28, 1987, for his role in the July 27, 1977, shooting of eight people, six fatally, during the robbery of a small-time drug dealer's home in Carol City, a Miami suburb. He was a co-defendant with Marvin Francois, executed May 29, 1985.

18. Willie Jasper Darden, 54, executed March 15, 1988, for the September 1973 shooting of James C. Turman in Lakeland.

19. Jeffrey Joseph Daugherty, 33, executed March 15, 1988, for the March 1976 murder of hitchhiker Lavonne Patricia Sailer in Brevard County.

20. Theodore Robert Bundy, 42, executed Jan. 24, 1989, for the rape and murder of 12-year-old Kimberly Leach of Lake City at the end of a cross-country killing spree. Leach was kidnapped Feb. 9, 1978, and her body was found three months later some 32 miles west of Lake City.

21. Aubry Dennis Adams Jr., 31, executed May 4, 1989, for strangling 8-year-old Trisa Gail Thornley on Jan. 23, 1978, in Ocala.

< 22. Jessie Joseph Tafero, 43, executed May 4, 1990, for the February 1976 shooting deaths of Florida Highway Patrolman Phillip Black and his friend Donald Irwin, a Canadian constable from Kitchener, Ontario. Flames shot from Tafero's head during the execution.

23. Anthony Bertolotti, 38, executed July 27, 1990, for the Sept. 27, 1983, stabbing death and rape of Carol Ward in Orange County.

24. James William Hamblen, 61, executed Sept. 21, 1990, for the April 24, 1984, shooting death of Laureen Jean Edwards during a robbery at the victim's Jacksonville lingerie shop.

25. Raymond Robert Clark, 49, executed Nov. 19, 1990, for the April 27, 1977, shooting murder of scrap metal dealer David Drake in Pinellas County.

26. Roy Allen Harich, 32, executed April 24, 1991, for the June 27, 1981, sexual assault, shooting and slashing death of Carlene Kelly near Daytona Beach.

27. Bobby Marion Francis, 46, executed June 25, 1991, for the June 17, 1975, murder of drug informant Titus R. Walters in Key West.

28. Nollie Lee Martin, 43, executed May 12, 1992, for the 1977 murder of a 19-year-old George Washington University student, who was working at a Delray Beach convenience store.

29. Edward Dean Kennedy, 47, executed July 21, 1992, for the April 11, 1981, slayings of Florida Highway Patrol Trooper Howard McDermon and Floyd Cone after escaping from Union Correctional Institution.

30. Robert Dale Henderson, 48, executed April 21, 1993, for the 1982 shootings of three hitchhikers in Hernando County. He confessed to 12 murders in five states.

31. Larry Joe Johnson, 49, executed May 8, 1993, for the 1979 slaying of James Hadden, a service station attendant in small north Florida town of Lee in Madison County. Veterans groups claimed Johnson suffered from post-traumatic stress syndrome.

32. Michael Alan Durocher, 33, executed Aug. 25, 1993, for the 1983 murders of his girlfriend, Grace Reed, her daughter, Candice, and his 6-month-old son Joshua in Clay County. Durocher also convicted in two other killings.

33. Roy Allen Stewart, 38, executed April 22, 1994, for beating, raping and strangling of 77-year-old Margaret Haizlip of Perrine in Dade County on Feb. 22, 1978.

34. Bernard Bolander, 42, executed July 18, 1995, for the Dade County murders of four men, whose bodies were set afire in car trunk on Jan. 8, 1980.

35. Jerry White, 47, executed Dec. 4, 1995, for the slaying of a customer in an Orange County grocery store robbery in 1981.

36. Phillip A. Atkins, 40, executed Dec. 5, 1995, for the molestation and rape of a 6-year-old Lakeland boy in 1981.

37. John Earl Bush, 38, executed Oct. 21, 1996, for the 1982 slaying of Francis Slater, an heir to the Envinrude outboard motor fortune. Slater was working in a Stuart convenience store when she was kidnapped and murdered.

38. John Mills Jr., 41, executed Dec. 6, 1996, for the fatal shooting of Les Lawhon in Wakulla and burglarizing Lawhon's home.

39. Pedro Medina, 39, executed March 25, 1997, for the 1982 slaying of his neighbor Dorothy James, 52, in Orlando. Medina was the first Cuban who came to Florida in the Mariel boat lift to be executed in Florida. During his execution, flames burst from behind the mask over his face, delaying Florida executions for almost a year.

40. Gerald Eugene Stano, 46, executed March 23, 1998, for the slaying of Cathy Scharf, 17, of Port Orange, who disappeared Nov. 14, 1973. Stano confessed to killing 41 women.

41. Leo Alexander Jones, 47, executed March 24, 1998, for the May 23, 1981, slaying of Jacksonville police Officer Thomas Szafranski.

42. Judy Buenoano, 54, executed March 30, 1998, for the poisoning death of her husband, Air Force Sgt. James Goodyear, Sept. 16, 1971.

43. Daniel Remeta, 40, executed March 31, 1998, for the murder of Ocala convenience store clerk Mehrle Reeder in February 1985, the first of five killings in three states laid to Remeta.

44. Allen Lee ``Tiny'' Davis, 54, executed in a new electric chair on July 8, 1999, for the May 11, 1982, slayings of Jacksonville resident Nancy Weiler and her daughters, Kristina and Katherine. Bleeding from Davis' nose prompted continued examination of effectiveness of electrocution and the switch to lethal injection.

45. Terry M. Sims, 58, became the first Florida inmate to be executed by injection on Feb. 23, 2000. Sims died for the 1977 slaying of a volunteer deputy sheriff in a central Florida robbery.

46. Anthony Bryan, 40, died from lethal injection Feb. 24, 2000, for the 1983 slaying of George Wilson, 60, a night watchman abducted from his job at a seafood wholesaler in Pascagoula, Miss., and killed in Florida.

47. Bennie Demps, 49, died from lethal injection June 7, 2000, for the 1976 murder of another prison inmate, Alfred Sturgis. Demps spent 29 years on death row before he was executed.

48. Thomas Provenzano, 51, died from lethal injection on June 21, 2000, for a 1984 shooting at the Orange County courthouse in Orlando. Provenzano was sentenced to death for the murder of William ``Arnie'' Wilkerson, 60.

49. Dan Patrick Hauser, 30, died from lethal injection on Aug. 25, 2000, for the 1995 murder of Melanie Rodrigues, a waitress and dancer in Destin. Hauser dropped all his legal appeals.

50. Edward Castro, died from lethal injection on Dec. 7, 2000, for the 1987 choking and stabbing death of 56-year-old Austin Carter Scott, who was lured to Castro's efficiency apartment in Ocala by the promise of Old Milwaukee beer. Castro dropped all his appeals.

51. Robert Glock, 39 died from lethal injection on Jan. 11, 2001, for the kidnapping murder of a Sharilyn Ritchie, a teacher in Manatee County. She was kidnapped outside a Bradenton shopping mall and taken to an orange grove in Pasco County, where she was robbed and killed. Glock's co-defendant Robert Puiatti remains on death row.

52. Rigoberto Sanchez-Velasco, 43, died of lethal injection on Oct. 2, 2002, after dropping appeals from his conviction in the December 1986 rape-slaying of 11-year-old Katixa ``Kathy'' Ecenarro in Hialeah. Sanchez-Velasco also killed two fellow inmates while on death row.

53. Aileen Wuornos, 46, died from lethal injection on Oct. 9, 2002, after dropping appeals for deaths of six men along central Florida highways.

54. Linroy Bottoson, 63, died of lethal injection on Dec. 9, 2002, for the 1979 murder of Catherine Alexander, who was robbed, held captive for 83 hours, stabbed 16 times and then fatally crushed by a car.

55. Amos King, 48, executed by lethal inection for the March 18, 1977 slaying of 68-year-old Natalie Brady in her Tarpon Spring home. King was a work-release inmate in a nearby prison.

56. Newton Slawson, 48, executed by lethal injection for the April 11, 1989 slaying of four members of a Tampa family. Slawson was convicted in the shooting deaths of Gerald and Peggy Wood, who was 8 1/2 months pregnant, and their two young children, Glendon, 3, and Jennifer, 4. Slawson sliced Peggy Wood's body with a knife and pulled out her fetus, which had two gunshot wounds and multiple cuts.

57. Paul Hill, 49, executed for the July 29, 1994, shooting deaths of Dr. John Bayard Britton and his bodyguard, retired Air Force Lt. Col. James Herman Barrett, and the wounding of Barrett's wife outside the Ladies Center in Pensacola.

58. Johnny Robinson, died by lethal injection on Feb. 4, 2004, for the Aug. 12, 1985 slaying of Beverly St. George was traveling from Plant City to Virginia in August 1985 when her car broke down on Interstate 95, south of St. Augustine. He abducted her at gunpoint, took her to a cemetery, raped her and killed her.

59. John Blackwelder, 49, was executed by injection on May 26, 2004, for the calculated slaying in May 2000 of Raymond Wigley, who was serving a life term for murder. Blackwelder, who was serving a life sentence for a series of sex convictions, pleaded guilty to the slaying so he would receive the death penalty.

60. Glen Ocha, 47, was execited by injection April 5, 2005, for the October, 1999, strangulation of 28-year-old convenience store employee Carol Skjerva, who had driven him to his Osceola County home and had sex with him. He had dropped all appeals.

61. Clarence Hill 20 September 2006 lethal injection Stephen Taylor Jeb Bush

62. Arthur Dennis Rutherford 19 October 2006 lethal injection Stella Salamon Jeb Bush

63. Danny Rolling 25 October 2006 lethal injection Sonja Larson, Christina Powell, Christa Hoyt, Manuel R. Taboada, and Tracy Inez Paules

64. Ángel Nieves Díaz 13 December 2006 lethal injection Joseph Nagy

65. Mark Dean Schwab 1 July 2008 lethal injection Junny Rios-Martinez, Jr.

66. Richard Henyard 23 September 2008 lethal injection Jamilya and Jasmine Lewis

67. Wayne Tompkins 11 February 2009 lethal injection Lisa DeCarr

68. John Richard Marek 19 August 2009 lethal injection Adela Marie Simmons

69. Martin Grossman 16 February 2010 lethal injection Margaret Peggy Park

70. Manuel Valle 28 September 2011 lethal injection Louis Pena

Valle v. State, 394 So.2d 1004 (Fla. 1981) (Direct Appeal-Reversed).

Defendant was convicted in the Circuit Court, Dade County, Ellen J. Morphonios, J., of first-degree murder of a police officer, attempted murder in the first degree, and possession of a firearm by a convicted felon. Defendant appealed. The Supreme Court held that: (1) where, with expedited trial date and resulting abbreviated trial preparation, defense counsel, even though diligent, was unable to interview 24 of 59 witnesses listed by State pursuant to discovery rules, was denied opportunity to investigate defendant's mental condition and was denied opportunity to present evidence concerning pretrial motions, prejudice to defendant was clear from record; (2) asserted overwhelming evidence against defendant in trial phase did not override his Sixth and Fourteenth Amendment rights to adequate preparation time and effective assistance of counsel; and (3) trial which commenced only 36 days after police officer's murder, 34 days after defendant's arrest, 24 days from date of arraignment and 21 days from date of first discovery information furnished by State denied defendant fair trial, under circumstances of case. Judgment and sentence vacated, and case remanded for new trial. Adkins, J., dissented.

Valle v. State, 474 So.2d 796 (Fla. 1985) (Direct Appeal-Affirmed).

After remand, 394 So.2d 1004, defendant was convicted in the Circuit Court, Dade County, James R. Jorgenson, J., of first-degree murder, and sentenced to death, and he appealed. The Supreme Court, Adkins, J., held that: (1) defendant's confession was admissible; (2) defendant failed to establish that venire selection process substantially underrepresented Latin Americans, blacks, or women; (3) juror was properly excluded for cause for statements that her feelings concerning capital punishment would impair her ability to follow the the law as the judge instructed her; and (4) prosecutor's remarks on closing argument concerning defendant's possibility for parole, and concerning victim's family, were not reversible error. Affirmed. Ehrlich, J., filed concurring opinion in which Overton, J., concurs. Shaw, J., concurred in result only.

ADKINS, Justice.

Appellant, Manuel Valle, appeals his conviction for first-degree murder and his sentence of death. We have jurisdiction. Art. V, § 3(b)(1), Fla. Const. We affirm the conviction and the death sentence.

On April 2, 1978, Officer Louis Pena of the Coral Gables Police Department was on patrol when he stopped appellant and a companion for a traffic violation. The events that followed were witnessed by Officer Gary Spell, also of the Coral Gables Police Department. Officer Spell testified that when he arrived at the scene, appellant was sitting in the patrol car with Officer Pena. Shortly thereafter, Spell heard Pena use his radio to run a license check on the car appellant was driving. According to Spell, appellant then walked back to his car and reached into it, approached Officer Pena and fired a single shot at him, which resulted in his death. Appellant also fired two shots at Spell and then fled. He was picked up two days later in Deerfield Beach. Following his jury trial, appellant was also found guilty of the attempted first-degree murder of Spell and after a non-jury trial, he was found guilty of possession of a firearm by a convicted felon.

CONVICTION

Appellant makes several challenges to his conviction. Specifically, he challenges (1) the admission of his confession to this murder, (2) the method of selection of the grand and petit jury venires, and (3) the trial court's refusal to grant a mistrial on the basis of the prosecutor's alleged comments on his constitutional right to remain silent.

Appellant argues that his confession, which was admitted at trial, should have been suppressed because it was allegedly obtained in violation of his Miranda ( Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 86 S.Ct. 1602, 16 L.Ed.2d 694 (1966)), rights. Shortly after appellant was arrested he was informed of his rights to remain silent and to have counsel present during questioning and the record shows that he waived those rights. Nonetheless, appellant argues that certain events following this initial free and voluntary waiver indicate that he subsequently invoked his Miranda rights. We do not agree. The record reveals that pursuant to their established procedure, the Deerfield Beach Police Department contacted a public defender who spoke with appellant on the telephone. Later, when the interrogating officers arrived and informed appellant that they were there to conduct an interview, appellant stated that he had spoken with an attorney and she had advised him not to sign anything nor to answer any questions. The officer then stated that it was appellant's constitutional right to refuse to speak to him, that he did not have to speak if he did not want to, and that he had come to Deerfield Beach hopefully to talk with him.

Even assuming that appellant's statement was somehow an invocation of his Miranda rights, it was at most an equivocal one, and interrogating officers are permitted to initiate further communications for the purpose of clarifying the suspect's wishes. Thompson v. Wainwright, 601 F.2d 768 (5th Cir.1979); Nash v. Estelle, 597 F.2d 513 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, 444 U.S. 981, 100 S.Ct. 485, 62 L.Ed.2d 409 (1979). Thus, when the officer responded that “that was his constitutional right” and that he was there “hopefully to speak with him,” he was not conducting further interrogation within the meaning of Rhode Island v. Innis, 446 U.S. 291, 100 S.Ct. 1682, 64 L.Ed.2d 297 (1980), but was simply trying to determine whether or not the appellant wished to talk. Cf. Cannady v. State, 427 So.2d 723 (Fla.1983) ( “I think I should call my lawyer” held to be an equivocal request for counsel); Waterhouse v. State, 429 So.2d 301 (Fla.) (interrogation does not have to cease when accused states “I think I want to talk to an attorney before I say anything else” because he did not express a desire to deal with the police only through counsel), cert. denied, 464 U.S. 977, 104 S.Ct. 415, 78 L.Ed.2d 352 (1983). The right to counsel during questioning can be waived. Witt v. State, 342 So.2d 497 (Fla.), cert. denied, 434 U.S. 935, 98 S.Ct. 422, 54 L.Ed.2d 294 (1977). After the officer's innocuous reply, appellant's next statement that he had had several experiences with police officers in the past and that he had cooperated in the past and was willing to do so at that time, clearly shows that he voluntarily waived his Miranda rights. Even if he had previously asserted his rights, the law accords a defendant the opportunity to voluntarily change his mind and talk to police officers. Witt, 342 So.2d at 500. This statement, combined with the previous oral waiver, a later express written waiver, and the fact that at not time before, during, or after questioning did appellant request an attorney, convinces us that he made a voluntary, knowing and intelligent waiver of his Miranda rights. Edwards v. Arizona, 451 U.S. 477, 101 S.Ct. 1880, 68 L.Ed.2d 378 (1981); Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458, 58 S.Ct. 1019, 82 L.Ed. 1461 (1938). The trial judge was correct in admitting appellant's confession.

Appellant also contends that because the public defender instructed the Deerfield Beach officers not to question appellant and they agreed, that amounted to an invocation of his right to counsel. That is simply not true. The determination of the need of counsel is the defendant's prerogative. State v. Craig, 237 So.2d 737 (Fla.1970). Thus, just as his attorney would have no right to waive appellant's right to counsel, without his consent, she likewise would have no right to unilaterally invoke that right.

Appellant argues next that his rights to due process and equal protection of the law were violated by substantial underrepresentation of Latin Americans, blacks, and women on the grand and petit jury venires. Appellant's grand jury was selected in accordance with chapters 70–1000, 57–550, and 57–551, Laws of Florida. Pursuant to these laws, circuit judges of the Eleventh Judicial Circuit of Florida submit the names of approximately five hundred individuals believed to be morally fit for jury service. A venire of ninety persons is then formed by a random selection.

This method of grand jury selection and the legislation authorizing grand jury selection have been consistently upheld by this Court as both constitutional and effective. See Dykman v. State, 294 So.2d 633 (Fla.1973); Rojas v. State, 288 So.2d 234 (Fla.1973), cert. denied, 419 U.S. 851, 95 S.Ct. 93, 42 L.Ed.2d 82 (1974); Seay v. State, 286 So.2d 532 (Fla.1973), cert. denied, 419 U.S. 847, 95 S.Ct. 84, 42 L.Ed.2d 77 (1974); Calvo v. State, 313 So.2d 39 (Fla. 3d DCA 1975), cert. denied, 330 So.2d 15 (Fla.), cert. denied, 429 U.S. 918, 97 S.Ct. 309, 50 L.Ed.2d 283 (1976). However, this method is constitutional only if there is a random selection of jurors by the circuit judges. As we stated in State v. Silva, 259 So.2d 153, 160 (Fla.1972):

The tradition of trial by jury, considered in connection with either criminal or civil proceedings, necessarily contemplates an impartial jury drawn from a cross-section of the community. This does not mean, however, that every jury must contain representatives of all the economic, social, religious, racial, political and geographical groups of the community, for such complete representation would frequently be impossible. But it does mean that prospective jurors must be selected at random by the proper selecting officials without systematic and intentional exclusion of any of these groups. (emphasis in original).

Appellant claims that the venire selection process used to select the grand jury which indicted him and prior grand juries was not random with regard to Latin Americans. The Supreme Court of the United States has stated that “in order to show that an equal protection violation has occurred in the context of grand jury selection, the defendant must show that the procedure employed resulted in substantial underrepresentation of his race or of the identifiable group to which he belongs. Casteneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482, 494, 97 S.Ct. 1272, 1280, 51 L.Ed.2d 498 (1977).

Appellant, by his characterization of himself as a Latin American, has failed to prove that he belongs to an identifiable group. “The first step is to establish that the group is one that is a recognizable, distinct class, singled out for different treatment under the laws, as written or as applied.” Id. The term “Latin American” encompasses people from too many different countries and different cultural backgrounds and attitudes to constitute a single cognizable class for equal protection analysis. Accord, United States v. Rodriguez, 588 F.2d 1003 (5th Cir.1979). See also United States v. Duran de Amesquita, 582 F.Supp. 1326 (S.D.Fla.1984) (holding that “hispanics” do not constitute a recognizable class). Appellant also urges a due process violation in the grand jury selection process. The first prong of the test for a due process violation requires that defendant show “that the group alleged to be excluded is a ‘distinctive’ group in the community....” Duren v. Missouri, 439 U.S. 357, 364, 99 S.Ct. 664, 668, 58 L.Ed.2d 579 (1979). For the same reason, appellant has failed to prove that Latin Americans are a “distinctive” group in the community.

Appellant has also failed to prove that this method of grand jury selection was anything other than random with respect to blacks and women. In this case, the petit jury venire was randomly selected by computer from Dade County's voter registration list. Appellant argues that although section 40.01, Florida Statutes (1981), requires that all jurors be registered voters, it is nonetheless impermissible to rely exclusively upon voter lists as the source for random selection of veniremen. However, this Court has repeatedly upheld the constitutionality of section 40.01 against the argument that the selection of juries solely from voter lists was defective. See, e.g., Bryant v. State, 386 So.2d 237 (Fla.1980); Johnson v. State, 293 So.2d 71 (Fla.1974); Reed v. State, 292 So.2d 7 (Fla.), cert. denied, 419 U.S. 995, 95 S.Ct. 307, 42 L.Ed.2d 268 (1974); Jones v. State, 289 So.2d 385 (Fla.1974). Appellant has failed to overcome the presumptive fairness of the source of the petit jurors.

Finally, we find no basis for quashing the indictment or setting aside appellant's conviction based on his challenge to the selection of the grand jury foreperson for the same reasons which we expressed in Andrews v. State, 443 So.2d 78 (Fla.1983).

Appellant's final challenge to his conviction concerns testimony by the interrogating officer that when he asked the appellant the name of his employer during questioning appellant replied, “I'd rather not say.” Appellant contends that this was an impermissible comment by the prosecutor on his exercise of his right to remain silent.

In Donovan v. State, 417 So.2d 674 (Fla.1982), this Court reaffirmed the holding in Bennett v. State, 316 So.2d 41 (Fla.1975), that it is reversible error to comment on an accused's exercise of his right to remain silent. However, we stated in Donovan that “[f]or Bennett to apply, the accused must have exercised his right to remain silent.” 417 So.2d at 675. Appellant refused to answer one question of the many that were asked of him after he had been given his Miranda warnings and had freely and voluntarily waived them. Similarly, in Ragland v. State, 358 So.2d 100 (Fla. 3d DCA), cert. denied, 365 So.2d 714 (Fla.1978), the accused declined to answer one question of many. The court reasoned:

While we are fully aware of the restrictions placed upon prosecutors on commenting upon a defendant's exercise of his or her constitutional right to remain silent, Doyle v. Ohio, 426 U.S. 610 [96 S.Ct. 2240, 49 L.Ed.2d 91] (1976); Bennett v. State, 316 So.2d 41 (Fla.1975), the record before us conclusively demonstrates that appellant never invoked his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. Rather, the record reveals that after being given his Miranda warnings, appellant freely and voluntarily conversed with the police. During this post- Miranda lengthy conversation, appellant refused to answer one question of many. We do not believe that comment upon the failure to answer a single question was violative of appellant's constitutional right, when said constitutional right was not invoked. Id. at 100 (citations omitted).

We agree with this reasoning and find it to be particularly applicable to this case. We, therefore, approve the holding in Ragland and find that appellant did not invoke his Miranda rights when he refused to answer one question. Again, the trial judge was correct in not granting a mistrial.

SENTENCE

Appellant also makes several challenges to his sentence. These are: 1) that the trial judge erred by excluding a prospective juror, for cause, 2) that death may not be imposed where mitigating character evidence that appellant would be a model prisoner was excluded, 3) that the prosecutor made impermissible comments during closing arguments, 4) that the jury was not properly instructed on mitigating and aggravating circumstances, 5) that the trial court improperly found this murder to be especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel and 6) that the trial court refused to find certain statutory mitigating circumstances.

First, appellant argues that the sentence of death should be vacated because a juror who had serious reservations about the death penalty was excluded for cause in violation of Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510, 88 S.Ct. 1770, 20 L.Ed.2d 776 (1968). Nearly half of the venire at Witherspoon's trial was eliminated by challenges for cause under the authority of an Illinois statute which provided:

In trials for murder it shall be a cause for challenge of any juror who shall, on being examined, state that he has conscientious scruples against capital punishment, or that he is opposed to the same. 391 U.S. at 512, 88 S.Ct. at 1772. The jury in the state of Illinois at the time was given unlimited discretion to decide whether or not death was the “proper penalty” in a particular case. Id. at 519, 88 S.Ct. at 1775. The Supreme Court held that “a sentence of death cannot be carried out if the jury that imposed or recommended it was chosen by excluding verniremen for cause simply because they voiced general objections to the death penalty or expressed conscientious or religious scruples against its infliction.” Id. at 522, 88 S.Ct. at 1777 (footnote omitted).

After the Witherspoon decision, the Supreme Court and lower courts, this Court included, began to refer to language in footnotes 9 and 21 of Witherspoon as setting the standard for excluding jurors who were opposed to capital punishment. E.g., Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 U.S. 262, 265, 90 S.Ct. 1578, 1580, 26 L.Ed.2d 221 (1970); Boulden v. Holman, 394 U.S. 478, 482, 89 S.Ct. 1138, 1140, 22 L.Ed.2d 433 (1969); Stewart v. State, 420 So.2d 862, 864 (Fla.1982), cert. denied, 460 U.S. 1103, 103 S.Ct. 1802, 76 L.Ed.2d 366 (1983); King v. State, 390 So.2d 315, 319, cert. denied, 450 U.S. 989, 101 S.Ct. 1529, 67 L.Ed.2d 825 (Fla.1980). In footnote 21, the Court noted that jurors may be excluded for cause if they make it unmistakably clear (1) that they would automatically vote against the imposition of capital punishment without regard to any evidence that might be developed at the trial of the case before them, or (2) that their attitude toward the death penalty would prevent them from making an impartial decision as to the defendant's guilt. Id. 391 U.S. at 522 n. 21, 88 S.Ct. at 1777 n. 21. Similar language in footnote 9 provided:

Unless a venireman states unambiguously that he would automatically vote against the imposition of capital punishment no matter what the trial might reveal, it simply cannot be assumed that that is his position. Id. 391 U.S. at 515 n. 9, 88 S.Ct. at 1773 n. 9. The Witherspoon test has recently been rejected by the United States Supreme Court, however. In Wainwright v. Witt, 469 U.S. 412, 105 S.Ct. 844, 83 L.Ed.2d 841 (1985), a Florida case, the Court clarified the “general confusion surrounding the application of Witherspoon.” It held that the proper standard for excluding jurors opposed to capital punishment was set forth in a later case, Adams v. Texas, 448 U.S. 38, 100 S.Ct. 2521, 65 L.Ed.2d 581 (1980). In Adams the Court discussed its prior opinions dealing with juror exclusion and, in doing so, it noted the Witherspoon language in footnote 21. However, it did not apply the Witherspoon test; rather, the Adams Court concluded:

This line of cases establishes the general proposition that a juror may not be challenged for cause based on his views about capital punishment unless those views would prevent or substantially impair the performance of his duties as a juror in accordance with his instructions and his oath. The State may insist, however, that jurors will consider and decide the facts impartially and conscientiously apply the law as charged by the Court. 448 U.S. at 45, 100 S.Ct. at 2526 (emphasis added).

The Court noted a number of reasons why the Adams test is preferable over Witherspoon, among them, present-day capital sentencing juries are no longer invested with unlimited discretion in choice of sentence, the statements in the Witherspoon footnotes were dicta, and the Adams standard is in accord with the traditional reasons for excluding jurors. 105 S.Ct. at 851.

Applying the Adams standard of whether the juror's views would “prevent or substantially impair the performance of his duties as a juror in accordance with his instructions and his oath” to the facts of this case, we conclude that juror Ladd was properly excluded for cause. An examination of the voir dire record in this case reveals that Ms. Ladd, the excluded juror, came forward after the initial voir dire was completed, and told the bailiff that she would like to say something that she was too nervous to say before. The following colloquy then occurred:

THE BAILIFF: Miss Ladd wants to say something that she had forgotten about before.... MISS LADD: I don't know, but I was up here, I was like really nervous, and I was thinking of all the questions that you asked me. I wanted to say, like when I heard about the capital punishment and all that, I believe in it, I just don't know if I could do it. What you are saying about the second half of the trial and as far as could I make a decision and everything like that, I just don't believe that I personally could sentence anyone to death, and I just, since you were asking so many questions about the second part, I thought you might want to know that.... MISS LADD: You get so nervous. MR. ADORNO: Are you calm now or do you want a couple of more minutes? MISS LADD: I am as calm as I am going to be. MR. ADORNO: Please tell me what your opinion is as far as your concern? Are you concerned about the second phase? MISS LADD: Well, like I say, I believe in capital punishment, okay, and there's no problem there, but when I am really in here in seeing the defendant and everything and knowing what he looks like, I don't know if I personally could sentence anyone to death. MR. ADORNO: You believe in it, but you do not want to be a party to someone who potentially could be sentenced to death? That is basically what you are trying to tell me? MISS LADD: Basically. MR. ADORNO: This feeling that you have that you have expressed to us, is it of such a degree that first of all that it might affect you from the first part? In other words, we only get to the second part after the first part. MISS LADD: No, I don't think so. MR. ADORNO: So you could give me, on behalf of the State, a fair trial on the first part? MISS LADD: Yes. MR. ADORNO: Even though that is the first prerequisite? In other words, only if he is convicted of first degree murder is there the potential to have a jury recommend and the Court to sentence him to death. MISS LADD: Yes, the first part, you know, I can handle. MR. ADORNO: Let us go to the second part. Is it your feeling to such an extent that if I get up here in front of the twelve members of the jury and you are number twelve and I am telling you what I believe the evidence has shown and what the law is and what I believe is the appropriate recommendation as being death under the facts of the case, am I really only arguing to eleven? ... MISS LADD: I couldn't do it. MR. ADORNO: So you are telling me that there is no way I am going to be able to present to you by way of evidence anything that will get you to recommend anything other than life and make you consider to vote for a recommendation of death? MISS LADD: I can't say there is nothing, you couldn't do, but I mean, you would have a lot to overcome before you would be able to convince me. MR. ADORNO: Okay.... MR. ROSENBERG: What I am asking you is if you went through the guilt or innocence phase and you on the jury voted guilty and go to the second phase and in the second phase what the Court is seeking from you is a recommendation, and that recommendation is between life or death, and the Court instructs you that there are other factors to take into consideration in returning that recommendation and the Court instructs you that the recommendation is to be made by a majority of you, the jury, and the Court instructs you that the recommendation is advisory only, that the Court may not follow that in the final sentence and judgment, but that the Judge may do what he wishes, would you be able to follow those instructions? MISS LADD: No, because I would still see it as me. MR. ROSENBERG: Are there any circumstances under which you would be able to return or recommend to the Court the death penalty? MISS LADD: You know, I can't think there are none, but offhand I can't think of anything. You know, I mean I don't know about the case or anything like that, but I just don't know if I could do it.

On at least six separate occasions juror Ladd stated that her feelings concerning capital punishment would impair her ability to follow the law as the judge instructed her. While the question and answer session may not reach the point where her bias was made “unmistakably clear,” (although we think it did), it did reach a point where the trial judge could have concluded her views would substantially impair her ability to act as an impartial juror. Further, we pay great deference to the trial judge's findings because he was in a position to observe the juror's demeanor and credibility, unlike we as a reviewing court. This is in accord with the Supreme Court's holding in part III of Witt. Although the Witt Court was concerned with the deference to be paid a state trial court's finding in a petition for federal habeas corpus, the same applies on direct review. See 105 S.Ct. at 854.

In conclusion, we hold that the trial judge, aided by his ability to observe the demeanor and clarity of Ms. Ladd's responses, was properly entitled to exclude her for cause.

Appellant's next point on appeal concerns certain character evidence offered by him for the purpose of mitigation. This character evidence consisted of the proffered testimony of certain corrections consultants and prison psychiatrists who would testify that if appellant were given a sentence of life imprisonment rather than death, he would be a “model prisoner.” Appellant relies on our decision in Simmons v. State, 419 So.2d 316 (Fla.1982), to sustain his position that this testimony should have been admitted. That reliance is misplaced, however. In Simmons, the proffered testimony was that of a psychiatrist who stated that unlike some violent criminals with more severe character disorders, appellant had the capacity to be rehabilitated. Id. at 317–18. We held that the trial judge erred in not allowing this testimony before the jury. Unlike the proffered testimony in Simmons, there was no testimony by the expert witnesses here that appellant had the capacity to be rehabilitated, only that he would be a model prisoner while in prison. It does not necessarily follow that if one behaves while he is in prison that he will behave outside of prison.

Competent evidence of this same type had already been heard by the jury. Eurvie Wright, special administrator of the Dade County Corrections and Rehabilitation Department, was a bureau supervisor of the Dade County Stockade in 1975 when appellant was an inmate there. Wright, who was a rehabilitation officer, testified that during the time appellant was in prison, he was a model prisoner and was rehabilitated.

The arguments presented here are similar to those which this Court considered and rejected in Stewart v. State, 420 So.2d 862 (Fla.1982), cert. denied, 460 U.S. 1103, 103 S.Ct. 1802, 76 L.Ed.2d 366 (1983). In Stewart, there was evidence from three psychiatrists that the defendant was competent to stand trial. On the day the sentencing proceedings began, defense counsel moved for a continuance and appointment of a psychiatrist and psychologist, claiming their testimony was necessary to demonstrate certain mitigating circumstances set forth in section 921.141(6)(b), (e), and (f), Florida Statutes (1981). Stewart argued on appeal that the trial court's denial of the motion prevented the unlimited consideration of mitigating evidence as mandated by Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S. 586, 98 S.Ct. 2954, 57 L.Ed.2d 973 (1978). We found that another psychiatric examination would be merely cumulative and the trial court in no way limited the presentation or consideration of mitigating evidence. We then held that the trial court did not abuse its discretion by refusing to grant the continuance. Id. 420 So.2d at 864. We believe, then, that there was substantial, competent evidence presented to the jury on the issue of appellant Valle's rehabilitation; thus, as in Stewart, any other evidence on this issue was merely cumulative.

As for appellant's contention that the trial court erred in not finding the statutory mitigating circumstances set forth in sections 921.141(6)(b) and (f), neither the jury nor the trial court is compelled to find mitigating circumstances as long as they consider them. Hargrave v. State, 366 So.2d 1 (Fla.1978), cert. denied, 444 U.S. 919, 100 S.Ct. 239, 62 L.Ed.2d 176 (1979).

Appellant also contends that the prosecutor made several comments during his closing arguments that amounted to fundamental error, specifically, that the appellant might be paroled if sentenced to life imprisonment, and that a life sentence would be unfair to the victim's family. The record shows that, during closing argument, the prosecutor made the following remarks:

It seems the argument is going to be that 25 years is a real long time. Think about it. If you multiply that by the hours, by the days, by 25 years, that he will be there, he won't be out until he is 55. Well, think about that argument. At least he has hope, even at 55, to get out. His wife, his child, they all have hope that some day they will see him again. Alana Pena will never see Lou Pena again, nor his parents, nor his children. They will never spend a 55th birthday with Lou Pena, and if Mr. Rosenberg comes up and he begins to describe electrocution to you, I agree it is not very pleasant, but if he does, and you should consider that, which I believe you should not, and he describes the last meal and the last walk down the hallway to the room, think about it. This man has had a chance to prepare, to make his peace with his family and with God. Not on April 2nd, 1978, did Lou Pena ever get a chance to do this. When he left his home on that day, I am sure he did not think that that would be the last time he ever left, and I am sure when he kissed his wife and children good-bye, I am sure he did not think that would be the last one.