Executed February 8, 2012 at 6:21 p.m. by Lethal Injection in Mississippi

3rd murderer executed in U.S. in 2012

1280th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Mississippi in 2012

16th murderer executed in Mississippi since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(3) |

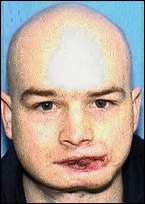

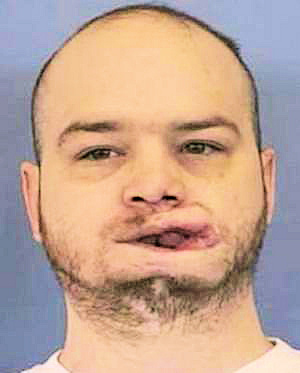

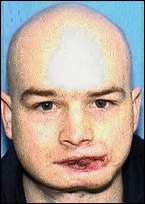

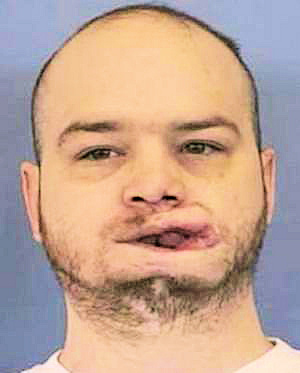

Edwin Hart Turner W / M / 22 - 38 |

Eddie Brooks B / M / 37 Everett Curry B / M / 38 |

Turner tried to commit suicide when he was 18 by putting a rifle in his mouth and pulling the trigger. His face was left severely disfigured.

Citations:

Turner v. State, 732 So.2d 937 (Miss. 1999). (Direct Appeal)

Turner v. State, 953 So.2d 1063 (Miss. 2007). (PCR)

Turner v. Epps, Slip Copy, 2010 WL 653880. (N.D. Miss. 2010) (Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

Porterhouse steak-medium rare, fried shrimp with cocktail sauce, Texas toast-2 slices, side salad with Russian dressing, 1 pack of red Twizzlers candy, and sweet tea.

Final Words:

None.

Internet Sources:

PARCHMAN — A man who twice sought to take his own life and then took the lives of two others died here Wednesday with no last words and without discussing his crimes. Edwin Hart Turner, 38, was pronounced dead at 6:21 p.m. at the State Penitentiary at Parchman, executed by lethal injection for the 1995 slayings of store clerk Eddie Brooks and prison guard Everett Curry during two alcohol-and drug-fueled robberies.

Curry's brother, Roy Curry, said afterward the pain of losing his brother was just as strong now as it was 16 years ago. He said Turner and accomplice Paul Stewart had never made any effort at apology or explanation. "One of the perpetrators of this evil act recently sought a pardon from the outgoing governor, yet Everett was robbed of the possibility of ever requesting a pardon for his life," he said. "May God have mercy on their souls."

Four family members of the victims sat quietly as Turner breathed his last. Asked if he had any last words, Turner replied, "No." Turner, wearing the red jumpsuit for death row inmates, was strapped down as the lethal cocktail flowed into his system. He exchanged brief words with people in the execution chamber, nodded twice and closed his eyes. MDOC Commissioner Chris Epps said at one point Turner asked, "What are we waiting on?"

Media witnesses Keith Hill of the Mississippi News Network and Charlie Smith of the Greenwood Commonwealth noted the lethal drugs began to take hold fairly quickly. Turner soon was lying motionless, mouth open, and seemed to be in a deep sleep. Both witness rooms were quiet during the execution. No discernable reaction was given by the families of Turner's victims.

Turner had requested his family not be present for the execution. His attorney, Lori Bell, whom Epps said Turner left his possessions, and his spiritual adviser, Tim Murphy, were among the witnesses. Turner's remains were released to his mother, LaDonna Turner, and his arrangements will be handled by Williams and Lord Funeral Home in Greenwood.

Curry said he hopes his family now can begin the healing process. "I don't think we'll ever have complete closure because a void will always exist in our hearts," he said. "At least we'll have some consolation in knowing the person who committed this cowardly and senseless act is finally gone. We pray that God would give us the faith and courage and strength to move on with our lives."

Turner's attorneys had sought to stop the execution, arguing he was mentally ill. Turner tried to commit suicide when he was 18 by putting a rifle in his mouth and pulling the trigger. His face was left severely disfigured. His attorney, Jim Craig, also has said Turner had spent three months in the State Hospital at Whitfield after slitting his wrists in another suicide attempt in 1995 - prior to the killings.

U.S. District Judge Carlton Reeves on Monday had granted a temporary stay until Feb. 20. But the 5th Circuit Court vacated the stay Wednesday. Gov. Phil Bryant also declined to step in on Turner's behalf. And the U.S. Supreme Court also refused to halt the execution.

On Dec. 12, 1995, Turner and Paul Stewart had been drinking beer and smoking marijuana while joy riding in Stewart's car when they decided to rob some Carroll County convenience stores. They first drove to Mims Truck Stop, but left it after finding it was too crowded. Their next stop was Mims Turkey Village Truck Stop, about four miles down the road. The two entered the stores carrying rifles and wearing masks. Turner shot Brooks, in the chest. Turner and Stewart tried to open the cash register by force and by shooting it. Then Turner shot Brooks in the head from only inches away. The two then went back to Mims Truck Stop, and while Stewart went inside the store, Turner robbed Curry, who was pumping gas outside. He shot Curry in the head.

Stewart proceeded to rob the store, and Turner came in, pointing his gun at the people in the store. Stewart testified he told Turner since he had the money, there was no need to kill anyone else. The next day, police found the weapons used in the murders inside Turner's home, and the masks used during the robberies in the back of Turner's car. Stewart pleaded guilty on July 19, 1996, to two counts of capital murder and testified against Turner.

Before Wednesday's execution, Rodney Gray, 38, was the last inmate put to death. He was one of two inmates executed in May. State officials predicted last year that at least three more executions could happen this year. Turner's was one of them. William Gerald Mitchell and Larry Matthew Puckett are the other two inmates whose petitions have been turned down by the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans. There are 56 inmates still on death row in Mississippi, including two females. The youngest is 26 and the oldest is 65.

Inmates William Gerald Mitchell and Larry Matthew Puckett likely are next to run out of appeals. Mitchell, 61, was sentenced to death in 1998 in Harrison County for killing 38-year-old store clerk Patty Milliken on Nov. 21, 1995. Prosecutors said Mitchell took Milliken from the store to a bridge, where he beat her and drove his car over her body. Puckett, 35, was sentenced to death in 1996 in Forrest County. He was convicted of capital murder and sexual assault in the 1995 death of Rhonda Griffis of the Sunrise community. Authorities said Griffis died from blows to the head.

Mississippi Department of Corrections

Inmate: EDWIN HART TURNERSentences:HOMICIDE (2 COUNTS) - 02/14/1997 FORREST COUNTY DEATH

Mississippi Department of Corrections

Death Row Inmate Edwin Hart Turner, MDOC #67290Factual Background of the Case

On December 12, 1995, Edwin Hart Turner (MDOC #67290) and another individual, Paul Stewart (MDOC #65682), were drinking beer and smoking marijuana while driving around in Stewart’s car. Eventually, Turner and Stewart decided to rob convenience stores in Carroll County, Mississippi. They first drove to Mims Truck Stop, but left after finding it too crowded. They then drove to Mims Turkey Village Truck Stop, about four miles away. At around 2:00 a.m. on December 13th, the two entered the store wearing masks and carrying rifles. Turner shot the store clerk, Eddie Brooks, in the chest. Turner and Stewart then tried to open the cash register, and at one point, both men shot at the register. After their unsuccessful attempts to open the register, Turner placed the barrel of his rifle inches from Eddie Brooks’ head and shot him.

Turner and Stewart then drove back to Mims Truck Stop. While Stewart went inside the store, Turner approached Everett Curry, who was pumping gas outside. Turner ordered Curry to the ground, robbed him, and shot him in the head. Meanwhile, inside the store, Stewart grabbed some of the store’s cash. Turner then came into the store and pointed his gun at the people inside. Stewart testified at trial that he told Turner there was no need to kill anyone else because Stewart already had the money from the cash register. The pair left the store and returned to Turner’s home. The next morning, police officers arrived at Turner’s home and found the two guns used in the crimes inside. They also found the hockey mask Stewart used during the robberies in the backseat of Turner’s car.

After the two were arrested, Stewart gave a full confession and pleaded guilty to two counts of capital murder. As part of his plea, Stewart agreed to testify against Turner. The jury ultimately found Turner guilty of two counts of capital murder while engaged in an armed robbery and imposed the death penalty. The convictions and death sentence were affirmed on direct appeal.

State Inmate Paul M. Stewart, MDOC #65682

White Male

DOB—06/14/1978

Entered MDOC on December 13, 1995

On July 19, 1996, Paul M. Stewart was convicted of two counts of capital murder in the Circuit Court of Carroll County and sentenced to two consecutive life sentences for the murders of Eddie Brooks and Everett Curry.

Execution by Lethal Injection

In 1998, the Mississippi Legislature amended Section 99-19-51, Mississippi Code of 1972, as follows: 99-19-51. The manner of inflicting the punishment of death shall be by continuous intravenous administration of a lethal quantity of an ultra short-acting barbiturate or other similar drug in combination with a chemical para-lytic agent until death is pronounced by the county coroner where the execution takes place or by a licensed physician according to accepted standards of medical practice.

Contents of Syringes for Lethal Injection

Anesthetic - Pentobarbital – 2.0 Gm.

Normal Saline – 10-15 cc.

Pavulon – 50 mgm per 50 cc.

Potassium chloride – 50 milequiv. per 50 cc.

Lethal Injection History

Lethal injection is the world’s newest method of execution. While the concept of lethal injection was first pro-posed in 1888, it was not until 1977 that Oklahoma became the first state to adopt lethal-injection legislation. Five years later in 1982, Texas performed the first execution by lethal injection. Lethal injection has quickly be-come the most common method of execution in the United States. Thirty-five of thirty-six states that have a death penalty use lethal injection as the primary form of execution. The U.S. federal government and U.S. mili-tary also use lethal injection. According to data from the U.S. Department of Justice, 41 of 42 people executed in the United States in 2007 died by lethal injection.

While lethal injection initially gained popularity as a more humane form of execution, in recent years there has been increasing opposition to lethal injection with opponents arguing that instead of being humane it results in an extremely painful death for the inmate. In September 2007 the United States Supreme Court agreed to hear the case of Baze v. Rees to determine whether or not Kentucky’s three drug-protocol for lethal injections amounts to cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment to the United State Constitution. As a result of the Supreme Court’s decision to hear this case, executions in the United States came to a brief halt in late September 2007. On April 16, 2008, the Supreme Court ruled in Baze holding that Kentucky’s three-drug protocol for administering lethal injections does not violate the Eighth Amendment. The result of this ruling was to lift the de facto moratorium on executions in the United States. The State of Georgia became the first state to carry out an execution since the Court’s Baze decision when William Earl Lynd was executed by lethal injection on May 6, 2008.

Chronological Sequence of Events of Execution

48 Hours Prior to Execution The condemned inmate shall be transferred to a holding cell.

24 Hours Prior to Execution Institution is placed in emergency/lockdown status.

1200 Hours Day of Execution Designated media center at institution opens.

1500 Hours Day of Execution Inmate’s attorney of record and chaplain allowed to visit.

1600 Hours Day of Execution Inmate is served last meal and allowed to shower.

1630 Hours Day of Execution MDOC clergy allowed to visit upon request of inmate.

1730 Hours Day of Execution Witnesses are transported to Unit 17.

1800 Hours Day of Execution Inmate is escorted from holding cell to execution room.

1800 Witnesses are escorted into observation room.

1900 Hours Day of Execution A post execution briefing is conducted with media witnesses.

2030 Hours Day of Execution Designated media center at institution is closed.

Death Row Executions

Since Mississippi joined the Union in 1817, several forms of execution have been used. Hanging was the first form of execution used in Mississippi. The state continued to execute prisoners sentenced to die by hanging until October 11, 1940, when Hilton Fortenberry, convicted of capital murder in Jefferson Davis County, became the first prisoner to be executed in the electric chair. Between 1940 and February 5, 1952, the old oak electric chair was moved from county to county to conduct execu-tions. During the 12-year span, 75 prisoners were executed for offenses punishable by death. In 1954, the gas chamber was installed at the Mississippi State Penitentiary, in Parchman, Miss. It replaced the electric chair, which today is on display at the Mississippi Law Enforcement Training Academy. Gearald A. Gallego became the first prisoner to be executed by lethal gas on March 3, 1955. During the course of the next 34 years, 35 death row inmates were executed in the gas cham-ber. Leo Edwards became the last person to be executed in the gas chamber at the Mississippi State Penitentiary on June 21, 1989.

On July 1, 1984, the Mississippi Legislature partially amended lethal gas as the state’s form of execu-tion in § 99-19-51 of the Mississippi Code. The new amendment provided that individuals who com-mitted capital punishment crimes after the effective date of the new law and who were subsequently sentenced to death thereafter would be executed by lethal injection. On March 18, 1998, the Mississippi Legislature amended the manner of execution by removing the provision lethal gas as a form of execution.

Mississippi State Penitentiary in Parchman, Mississippi

The Mississippi State Penitentiary (MSP) is Mississippi’s oldest of the state’s three institutions and is located on approximately 18,000 acres in Parchman, Miss., in Sunflower County. In 1900, the Mississippi Legislature appropriated $80,000 for the purchase of 3,789 acres known as the Parch-man Plantation. The Superintendent of the Mississippi State Penitentiary and Deputy Commissioner of Institutions is E.L. Sparkman. There are approximately 868 employees at MSP.

MSP is divided into two areas: AREA WARDEN UNITS - Area I - Warden Earnest Lee Unit 29, Area II - Warden Timothy Morris Units 25, 26, 28, 30, 31, and 42. The total bed capacity at MSP is currently 4,648. The smallest unit, Unit 42, houses 56 inmates and is the institution’s hospital. The largest unit, Unit 29, houses 1,561 minimum, medium, close-custody and Death Row inmates. MSP houses male offenders classified to all custody levels and Long Term Segregation and death row.

All male offenders sentenced to death are housed at MSP. All female offenders sentenced to death are housed at the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility in Pearl, Miss. The majority of the farming activity involving Agricultural Enterprises takes place at MSP. Programs offered at MSP include alcohol and drug treatment, adult basic education, inmate legal assistance, pre-release, therapeutic recreation, religious/faith programs and vocational skills training.

Mississippi Prison Industries operates a work program at the MSP and utilizes more than 296,400 inmate man-hours in its textile, metal fabrication and wood working shops. On a monthly average, 190 inmates work in these shops.

Death Row Executions

Since Mississippi joined the Union in 1817, several forms of execution have been used. Hanging was the first form of execution used in Mississippi. The state continued to execute prisoners sentenced to die by hanging until October 11, 1940, when Hilton Fortenberry, convicted of capital murder in Jefferson Davis County, became the first prisoner to be executed in the electric chair. Between 1940 and February 5, 1952, the old oak electric chair was moved from county to county to conduct execu-tions. During the 12-year span, 75 prisoners were executed for offenses punishable by death.

In 1954, the gas chamber was installed at the Mississippi State Penitentiary, in Parchman, Miss. It replaced the electric chair, which today is on display at the Mississippi Law Enforcement Training Academy. Gearald A. Gallego became the first prisoner to be executed by lethal gas on March 3, 1955. During the course of the next 34 years, 35 death row inmates were executed in the gas cham-ber. Leo Edwards became the last person to be executed in the gas chamber at the Mississippi State Penitentiary on June 21, 1989.

On July 1, 1984, the Mississippi Legislature partially amended lethal gas as the state’s form of execu-tion in § 99-19-51 of the Mississippi Code. The new amendment provided that individuals who com-mitted capital punishment crimes after the effective date of the new law and who were subsequently sentenced to death thereafter would be executed by lethal injection. On March 18, 1998, the Mississippi Legislature amended the manner of execution by removing the provision lethal gas as a form of execution.

Mississippi Death Row Demographics

Youngest on Death Row: Terry Pitchford, MDOC #117778, age 25

Oldest on Death Row: Richard Jordan, MDOC #30990, age 64

Longest serving Death Row inmate: Richard Jordan, MDOC #30990 March 2, 1977: Thirty-Four Years

The Mississippi State Penitentiary (MSP) is Mississippi’s oldest of the state’s three institutions and is located on approximately 18,000 acres in Parchman, Miss., in Sunflower County. In 1900, the Mississippi Legislature appropriated $80,000 for the purchase of 3,789 acres known as the Parch-man Plantation. The Superintendent of the Mississippi State Penitentiary and Deputy Commissioner of Institutions is E.L. Sparkman. There are approximately 921 employees at MSP. All male offenders sentenced to death are housed at MSP. All female offenders sentenced to death are housed at the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility in Pearl, Miss.

INMATES EXECUTED IN THE MISSISSIPPI GAS CHAMBER

Name Race-Sex Offense Date Executed

Gerald A. Gallego White Male Murder 03-03-55

Allen Donaldson Black Male Armed Robbery 03-04-55

August Lafontaine White Male Murder 04-28-55

John E. Wiggins White Male Murder 06-20-55

Mack C. Lewis Black Male Murder 06-23-55

Walter Johnson Black Male Rape 08-19-55

Murray G. Gilmore White Male Murder 12-09-55

Mose Robinson Black Male Rape 12-16-55

Robert Buchanan Black Male Rape 01-03-56

Edgar Keeler Black Male Murder 01-27-56

O.C. McNair Black Male Murder 02-17-56

James Russell Black Male Murder 04-05-56

Dewey Towsel Black Male Murder 06-22-56

Willie Jones Black Male Murder 07-13-56

Mack Drake Black Male Rape 11-07-56

Henry Jackson Black Male Murder 11-08-56

Minor Sorber White Male Murder 02-08-57

Joe L. Thompson Black Male Murder 11-14-57

William A. Wetzell White Male Murder 01-17-58

J.C. Cameron Black Male Rape 05-28-58

Allen Dean, Jr. Black Male Murder 12-19-58

Nathaniel Young Black Male Rape 11-10-60

William Stokes Black Male Murder 04-21-61

Robert L. Goldsby Black Male Murder 05-31-61

J.W. Simmons Black Male Murder 07-14-61

Howard Cook Black Male Rape 12-19-61

Ellic Lee Black Male Rape 12-20-61

Willie Wilson Black Male Rape 05-11-62

Kenneth Slyter White Male Murder 03-29-63

Willie J. Anderson Black Male Murder 06-14-63

Tim Jackson Black Male Murder 05-01-64

Jimmy Lee Gray White Male Murder 09-02-83

Edward E. Johnson Black Male Murder 05-20-87

Connie Ray Evans Black Male Murder 07-08-87

Leo Edwards Black Male Murder 06-21-89

PRISONERS EXECUTED BY LETHAL INJECTION

Name Race-Sex Offense Date Executed

Tracy A. Hanson White Male Murder 07-17-02

Jessie D. Williams White Male Murder 12-11-02

John B. Nixon, Sr. White Male Murder 12-14-05

Bobby G. Wilcher White Male Murder 10-18-06

Earl W. Berry White Male Murder 05-21-08

Dale L. Bishop White Male Murder 07-23-08

Paul E. Woodward White Male Murder 05-19-10

Gerald J. Holland White Male Murder 05-20-10

Joseph D. Burns White Male Murder 05-20-10

Benny Joe Stevens White Male Murder 05-10-11

Rodney Gray Black Male Murder 05-17-11

Source: Mississippi Department of Corrections, Mississippi State Penitentiary

"Mississippi man executed for 1995 robbery spree killings." (Associated Press 9:51 p.m. February 8, 2012)

PARCHMAN, Miss. — A Mississippi man was put to death Wednesday evening for killing two men in a December 1995 robbery spree after the courts declined to stop the execution based on arguments that the inmate was mentally ill at the time. Edwin Hart Turner, 38, died at 7:21 p.m. EST after receiving a chemical injection at the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman, authorities said.

Turner was convicted of capital murder in the deaths of Eddie Brooks and Everett Curry, who were slain at two gas stations a few miles apart that were targeted by Turner and another armed friend in a spree that netted them about $400. Brooks was shot to death first while working at one of the gas stations and Curry at the other while pumping gas when the pair went there next, toting rifles. Turner's accomplice testified against him and was sentenced to life in prison.

Wearing a red prison jumpsuit as he lay strapped on a gurney, Turner said, "No" when asked if he had a last statement. When the lethal chemicals began flowing, he closed his eyes, took a deep breath and appeared to fall asleep. The sister and a cousin of victim Eddie Brooks watched the execution. The brother and son of his other victim, Everett Curry, also did.

One of Curry's other brothers read a family statement afterward. "I don't think we will ever have complete closure because a void will always exist in our hearts," said Roy Curry, who did not watch the execution. "At least we will have some consolation in knowing that the person who committed this cowardly and senseless act is finally gone." Turner had requested that none of his family watch the execution, though his attorney and a pastor were present.

There was little dispute that Turner killed the two men while robbing gas stations, then went home and had a meal of shrimp and cinnamon rolls before going to sleep. But his lawyers had tried to block the execution in various state and federal courts based on the argument that Turner was mentally ill at the time of the crimes. The lawyers had hoped the U.S. Supreme Court would outlaw executions of the mentally ill as it has done with people considered mentally retarded.

The nation's highest court allowed the execution to go forward Wednesday when it rejected petitions to stop it. Earlier in the day, Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant had refused to grant a reprieve, saying after a review of the case, "I have decided not to grant clemency for his violent acts." Turner's lawyers had argued in the petition to the U.S. Supreme Court that he inherited a serious mental illness. They argued that his father is thought to have committed suicide by shooting a gun into a shed filled with dynamite and his grandmother and great-grandmother both spent time in the state mental hospital.

Turner's attorneys say he was severely disfigured during a suicide attempt at 18 by putting a rifle in his mouth and pulling the trigger. He had been released from a mental hospital just weeks before killing the two men, his lawyers said. Attorney General Jim Hood has said recently that Turner's mental health claims had been "fully addressed."

Richard Bourke, director of the Louisiana Capital Assistance Center that represented Turner, said after the execution in an emailed statement that he lamented the "tragic and senseless" killings. He also said Mississippi's mental health care system failed Turner, describing him as "a seriously mentally ill and tortured man" with no criminal history before those slayings.

Bourke's statement added Mississippi was among a handful of states that provide the least protection for the seriously mentally ill in their criminal justice systems. "This needs to change. At the very least, seriously mentally ill offenders whose illness contributed directly to their crimes should not be subjected to the death penalty," the statement added.

"Man executed for 1995 killings." (AP Wed, Feb. 08, 2012)

PARCHMAN -- Mississippi inmate Edwin Hart Turner was put to death Wednesday evening for killing two men in a 1995 robbery spree after the courts declined to stop the execution based on arguments that he was mentally ill. Turner, 38, was administered a lethal injection and died at 6:21 p.m. at the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman, authorities said. The inmate was convicted of killing the two men while robbing gas stations with his friend Paul Murrell Stewart in a spree that netted about $400. Stewart, 17 at the time, testified against Turner and was sentenced to life in prison.

Turner, wearing white shoes and one of the red prison jumpsuits issued to death row inmates, was strapped on a gurney. When a microphone was lowered to his mouth, he said, “no” when asked if he had a final statement. Then the chemicals began flowing through tubes into his body. He closed his eyes, took a deep breath and had the appearance of falling asleep.

Turner was convicted of capital murder in the deaths of Eddie Brooks and Everett Curry. Brooks was shot to death while working at Mims Turkey Village Truck Stop in Carroll County. Curry was shot to death while pumping gas at the nearby Mims One Stop.

The sister and a cousin of victim Eddie Brooks watched the execution. The brother and son of his other victim, Everett Curry, also witnessed it. One of Curry’s other brothers read a statement for the family afterward. “I don’t think we will ever have complete closure because a void will always exist in our hearts,” said Roy Curry, who did not watch the execution. “At least we will have some consolation in knowing that the person who committed this cowardly and senseless act is finally gone.” Turner had requested that none of his family watch the execution, though his attorney and a pastor were present.

There was little dispute that Turner killed two men while robbing gas stations, then went home and had a meal of shrimp and cinnamon rolls then went to sleep before deputies arrived. But his lawyers had tried to block the execution in various state and federal courts based on the argument that he was mentally ill. They had hoped the U.S. Supreme Court would outlaw executions of the mentally ill as it has done with people considered mentally retarded. The nation’s highest court allowed the execution to go forward Wednesday when it rejected petitions to stop it. Earlier in the day, Gov. Phil Bryant had refused to grant a reprieve, saying after a review of the case, “I have decided not to grant clemency for his violent acts.”

Turner’s lawyers had argued in the petition to the U.S. Supreme Court that he inherited a serious mental illness. They argued that his father is thought to have committed suicide by shooting a gun into a shed filled with dynamite and his grandmother and great-grandmother both spent time in the state mental hospital. Turner’s attorneys say he was severely disfigured during a suicide attempt at 18 by putting a rifle in his mouth and pulling the trigger. He had been released from a mental hospital just weeks before killing the two men, his lawyers said.

Turner’s lawyers had objected to the pace of events in the scheduling of the execution. “Execution was set in this case with only 13 days’ notice -- a procedure that would be illegal in most other states. Mississippi has created a time crunch and forced both the courts and the Governor to respond to this most serious of cases with inadequate time and consideration,” said Richard Bourke, director of the Louisiana Capital Assistance Center.

Corrections Commissioner Chris Epps said Turner was talkative during the day Wednesday but declined to discuss the crimes for which he was sentenced to death. Asked if Turner seemed mentally ill, Epps said of his visit with the prisoner in those final hours: “No, not to me. He appears to be on the ball.” Attorney General Jim Hood has said Turner’s mental health claims had been “fully addressed.”

Turner was convicted of killing the two men while robbing gas stations with Stewart, in a spree that netted about $400.

The 37-year-old Brooks was working at Mims Turkey Village Truck Stop on Mississippi’s U.S. Highway 82 when he was shot in the head and chest, but the pair left empty handed when they couldn’t get the register open even by shooting at it, according to court records. The two drove down the road to Mims One Stop, where Curry, a 38-year-old prison guard, was pumping gas. Stewart went inside to rob the store while Turner forced Curry to the ground at gunpoint. “As Curry was pleading for his life, Turner shot him in the head,” the records said.

"Mississippi: Edwin Hart Turner's execution temporarily halted by federal judge." (February 8, 2012)Edwin Hart Turner

A federal judge on Monday temporarily halted the scheduled execution of a convicted murderer in Mississippi in order to allow attorneys to argue whether the state has improperly kept him from getting a psychiatric evaluation. Edwin Hart Turner, 38, who was convicted of murdering two people during convenience store robberies in 1995, was set to die by lethal injection on Wednesday.

In an order on Monday, U.S. District Court Judge Carlton W. Reeves postponed Turner's execution until at least February 20. Last week, Turner's attorney filed a court brief accusing the Mississippi Department of Corrections of improperly preventing a psychiatrist from evaluating Turner.

Attorney James Craig of the Louisiana Capital Assistance Center said in the court filing that important information that related to Turner's mental health wasn't presented during his trial. Craig said Turner had a "long and extensive" history of mental illness. The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that executing mentally retarded people is cruel and unusual punishment. Turner is asking the Supreme Court to extend that ruling to the mentally ill.

Turner was sentenced to death for killing Eddie Brooks and Everett Curry in 2 separate incidents in Carroll County, Mississippi on the same day in 1995. Before the murders, a suicide attempt had left Turner's face disfigured. Witnesses identified him at 1 of the crime scenes by a towel he wore around his head to hide his disfigurement.

An accomplice, Paul M. Stewart, confessed to the crimes and testified against Turner. Stewart was convicted of 2 counts of capital murder and sentenced to 2 consecutive life terms in prison. A spokeswoman for Attorney General Jim Hood said he had not yet reviewed the court order postponing the execution and would only comment on the case through court filings.

(Source: Reuters, Feb.7, 2012)

Mississippi execution is temporarily blocked by judge

A federal judge on Monday temporarily blocked the execution of a Mississippi inmate who killed two men during a robbery spree in 1995. The man's attorneys asked for the order, not arguing guilt or innocence, but that Edwin Hart Turner is mentally ill and should not be executed. Condemned inmate Edwin Hart Turner has asked a federal judge to halt his scheduled Feb. 8 execution until he can get a mental examination. U.S. District Judge Carlton Reeves will conduct a hearing Friday in Jackson on Turner's request.

U.S. District Judge Carlton Reeves ordered the Mississippi Department of Corrections to allow Turner to be seen by a psychiatrist of his choosing. James Craig with the Louisiana Capital Assistance Center argues that a Mississippi Department of Corrections policy prohibited Turner from getting tests that could prove he's mentally ill. Craig said the policy, which dates to the 1990s, violates prisoners' rights to have access to courts and other materials that can help them develop evidence.

The policy requires court orders for medical experts or others to visit and test inmates. Craig said the right tests would show Turner is mentally ill. Mississippi Attorney General Jim Hood has said Turner's lawyers are bringing up old arguments that have been rejected by the courts before. "We argue that his mental health claims have been fully addressed, and that this present action is nothing more than an attempt to re-litigate a claim that has been properly adjudicated at every turn," Hood said in a statement.

Mississippi is 1 of 10 states that permit someone who suffered from serious mental illness at the time of the offense to be executed, according to a petition filed with the U.S. Supreme Court. Turner's lawyers want the Court to prohibit the execution of mentally ill people the way it did inmates considered mentally retarded.

There's little dispute that Turner killed the men then went home and had a meal of shrimp and cinnamon rolls before going to sleep. He's scheduled to die by injection Wednesday. His attorneys have filed 2 separate petitions that seek to stop the execution, 1 with the U.S. Supreme Court and the other 1 in federal court in Jackson. Turner's lawyers argue that Turner inherited a serious mental illness. His father is thought to have committed suicide by shooting a gun into a shed filled with dynamite and his grandmother and great-grandmother both spent time in the state mental hospital.

Craig said in a telephone interview Monday that Turner had spent 3 months in the Mississippi State Hospital at Whitfield after slitting his wrists in 1995. He had been out about 6 weeks before the killings occurred.

Turner, 38, was convicted of killing the 2 men while robbing gas stations with his friend, Paul Murrell Stewart, in a spree that netted about $400. Stewart, who was 17 at the time, testified against Turner and was sentenced to life in prison. Craig said Turner was diagnosed with depression that year and given the antidepressant medication Prozac. Craig believes Turner was misdiagnosed and that Prozac compounded his problems. "If the folks at Whitfield knew then what we know now, I feel confident they wouldn't have released him with 40 milligrams of Prozac," Craig said.

(Source: Associated Press, Feb. 7, 2012)

"Edwin Hart Turner Executed In Mississippi Despite Claims He Was Mentally Ill." (02/8/12 09:46 PM)PARCHMAN, Miss. -- A Mississippi man was put to death Wednesday evening for killing two men in a December 1995 robbery spree after the courts declined to stop the execution based on arguments that the inmate was mentally ill at the time. Edwin Hart Turner, 38, died at 7:21 p.m. EST after receiving a chemical injection at the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman, authorities said.

Turner was convicted of capital murder in the deaths of Eddie Brooks and Everett Curry, who were slain at two gas stations a few miles apart that were targeted by Turner and another armed friend in a spree that netted them about $400. Brooks was shot to death first while working at one of the gas stations and Curry at the other while pumping gas when the pair went there next, toting rifles. Turner's accomplice testified against him and was sentenced to life in prison.

Wearing a red prison jumpsuit as he lay strapped on a gurney, Turner said, "No" when asked if he had a last statement. When the lethal chemicals began flowing, he closed his eyes, took a deep breath and appeared to fall asleep.

The sister and a cousin of victim Eddie Brooks watched the execution. The brother and son of his other victim, Everett Curry, also did. One of Curry's other brothers read a family statement afterward. "I don't think we will ever have complete closure because a void will always exist in our hearts," said Roy Curry, who did not watch the execution. "At least we will have some consolation in knowing that the person who committed this cowardly and senseless act is finally gone." Turner had requested that none of his family watch the execution, though his attorney and a pastor were present.

There was little dispute that Turner killed the two men while robbing gas stations, then went home and had a meal of shrimp and cinnamon rolls before going to sleep. But his lawyers had tried to block the execution in various state and federal courts based on the argument that Turner was mentally ill at the time of the crimes. The lawyers had hoped the U.S. Supreme Court would outlaw executions of the mentally ill as it has done with people considered mentally retarded.

The nation's highest court allowed the execution to go forward Wednesday when it rejected petitions to stop it. Earlier in the day, Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant had refused to grant a reprieve, saying after a review of the case, "I have decided not to grant clemency for his violent acts." Turner's lawyers had argued in the petition to the U.S. Supreme Court that he inherited a serious mental illness. They argued that his father is thought to have committed suicide by shooting a gun into a shed filled with dynamite and his grandmother and great-grandmother both spent time in the state mental hospital.

Turner's attorneys say he was severely disfigured during a suicide attempt at 18 by putting a rifle in his mouth and pulling the trigger. He had been released from a mental hospital just weeks before killing the two men, his lawyers said. Attorney General Jim Hood has said recently that Turner's mental health claims had been "fully addressed."

Richard Bourke, director of the Louisiana Capital Assistance Center that represented Turner, said after the execution in an emailed statement that he lamented the "tragic and senseless" killings. He also said Mississippi's mental health care system failed Turner, describing him as "a seriously mentally ill and tortured man" with no criminal history before those slayings.

Bourke's statement added Mississippi was among a handful of states that provide the least protection for the seriously mentally ill in their criminal justice systems. "This needs to change. At the very least, seriously mentally ill offenders whose illness contributed directly to their crimes should not be subjected to the death penalty," the statement added.

Turner v. State, 732 So.2d 937 (Miss. 1999). (Direct Appeal)

Defendant was convicted in the Circuit Court, Forrest County, of two counts of capital murder while in commission of armed robbery and sentenced to death after change of venue from the Circuit Court, Carroll County, C.E. Morgan, III, J. Defendant appealed. The Supreme Court, Pittman, P.J., held that: (1) warrantless arrest was legal; (2) defendant was not entitled to lesser included offense instruction on simple murder; and (3) death sentence was not excessive or disproportionate to other capital cases. Affirmed.

PITTMAN, Presiding Justice, for the Court:

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

¶ 1. The case at bar is an appeal from the Circuit Court of Forrest County, Mississippi, after a change of venue from Carroll County, Mississippi, First Judicial District. Turner was indicted by the Grand Jury of Carroll County, Mississippi, First Judicial District, on May 20, 1996, in a two count indictment charging him in Count I with the December 13, 1995, capital murder of Eddie Brooks during the commission of an armed robbery in violation of Miss.Code Ann. § 97–3–19(2)(e) and in Count II with the December 13, 1995, capital murder of Everett Curry during the commission of an armed robbery in violation of Miss.Code Ann. § 97–3–19(2)(e). Turner was tried, and the jury, after deliberation, found him guilty of capital murder on both Counts I and II on February 13, 1997. The jury then heard evidence in aggravation and mitigation of sentence. After deliberation, on February 14, 1997, the jury returned the following verdicts in proper form sentencing Turner to death on both Counts I and II.

¶ 2. The Count I verdict states: We, the Jury, unanimously find from the evidence beyond a reasonable doubt that the following facts existed at the time of the commission of the capital murder charged in Count I of the indictment: 1. That the defendant actually killed Eddie Brooks. 2. That the defendant attempted to kill Eddie Brooks. 3. That the defendant intended that the killing of Eddie Brooks take place. 4. That the defendant contemplated that lethal force would be employed. Next, we the jury, unanimously find that the aggravating circumstances of: The capital offense was committed for pecuniary gain during the course of an armed robbery. exists beyond a reasonable doubt and is sufficient to impose the death penalty and that there are insufficient mitigating circumstances to outweigh the aggravating circumstances, and we further find unanimously that the defendant should suffer death as to Count I of the indictment.

/s/Earl J. McGehee

Foreman of the Jury

¶ 3. The Count II verdict states: We, the Jury, unanimously find from the evidence beyond a reasonable doubt that the following facts existed at the time of the commission of the capital murder charged in Count II of the indictment: 1. That the defendant actually killed Everett Curry. 2 That the defendant attempted to kill Everett Curry. 3. That the defendant intended that the killing of Everett Curry take place. 4. That the defendant contemplated that lethal force would be employed. Next, we the jury, unanimously find that the aggravating circumstances of: The capital offense was committed for pecuniary gain during the course of an armed robbery. exists beyond a reasonable doubt and is sufficient to impose the death penalty and that there are insufficient mitigating circumstances to outweigh the aggravating circumstances, and we further find unanimously that the defendant should suffer death as to Count II of the indictment.

/s/Earl J. McGehee

Foreman of the Jury

¶ 4. After the sentence of death was imposed by the jury, the trial court set an execution date of March 28, 1997. Turner's motion for new trial was denied on March 25, 1997.FN1 Turner perfected his appeal on April 24, 1997. Turner presently awaits the outcome of this appeal in the Maximum Security Unit of the State Penitentiary at Parchman, Mississippi.

FN1. The order denying Turner's motion for new trial is dated July 10, 1997. However, the motion was orally denied on March 25, 1997, at the conclusion of the hearing on the motion for new trial.

¶ 5. Turner has raised thirteen (13) assignments of error for review by this Court: I. THE ARREST OF TURNER WAS ILLEGAL PURSUANT TO MISS. CODE ANN. § 99–3–7 AND SUBSEQUENT SEARCH AND SEIZURE VIOLATED THE FOURTH AND FOURTEENTH AMENDMENTS TO THE UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION AND THEIR MISSISSIPPI CONSTITUTIONAL COUNTERPARTS. II. COUPLING A VAGUE INDICTMENT WHICH DID NOT FAIRLY APPRISE THE DEFENDANT WITH NOTICE OF WHICH UNDERLYING FELONY WOULD BE PURSUED ALONG WITH A DUPLICITOUS JURY INSTRUCTION VIOLATED THE SIXTH, EIGHTH AND FOURTEENTH AMENDMENTS. III. THE LOWER COURT ERRED IN DENYING TURNER'S PROPOSED LESSER INCLUDED OFFENSE INSTRUCTION. IV. THE PROSECUTOR ENGAGED IN WHOLLY IMPROPER CROSSEXAMINATION OF SENTENCING PHASE WITNESSES SOLELY FOR THE PURPOSE OF INJECTING PREJUDICE TO INFLAME THE JURY. V. THE TRIAL COURT ERRED IN EXCLUDING RELEVANT MITIGATION EVIDENCE IN VIOLATION OF THE FEDERAL AND STATE CONSTITUTIONS AND STATE LAW. VI. THE LOWER COURT ERRED IN LIMITING CONSIDERATION OF MENTAL CAPACITY MITIGATING CIRCUMSTANCE TO “SUBSTANTIAL IMPAIRMENT.” VII. THE INSTRUCTIONS TO THE JURY AND THE INTRODUCTION OF THE GUILT PHASE EVIDENCE AT THE SENTENCING PHASE VIOLATED STATE LAW AND THE FEDERAL AND STATE CONSTITUTIONS. VIII. THE LOWER COURT ERRED IN REFUSING TO INSTRUCT THE JURY THAT THERE IS A PRESUMPTION THAT NO AGGRAVATING CIRCUMSTANCES EXIST. IX. THE LOWER COURT ERRED IN INSTRUCTING THE JURY AT SENTENCING IT COULD CONSIDER “THE DETAILED CIRCUMSTANCES OF THE OFFENSE.” X. THE LOWER COURT VIOLATED THE EIGHTH AMENDMENT AND STATE LAW BY INSTRUCTING THE JURY TO DISREGARD SYMPATHY IN REACHING ITS SENTENCING DECISION. XI. THE EIGHTH AMENDMENT AND STATE LAW WERE VIOLATED WHEN THE LOWER COURT ALLOWED IN ESSENCE BOTH THE ROBBERY AND PECUNIARY GAIN AGGRAVATING CIRCUMSTANCES TO BE CONSIDERED BY THE JURY. XII. THE STATE'S MISCONDUCT IN THE CLOSING ARGUMENT WARRANTS REVERSAL OF THE DEATH SENTENCE. XIII. THE STATE IMPROPERLY ARGUED STATUTORY AGGRAVATING CIRCUMSTANCE WHEN IT HAD PREVIOUSLY ON THE RECORD ELECTED TO ONLY PROCEED WITH THE PECUNIARY GAIN AGGRAVATOR AND HAD NOT SOUGHT TO PROCEED WITH THE HEINOUS, ATROCIOUS AND CRUEL AGGRAVATOR IN THE SENTENCING INSTRUCTION.

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

¶ 6. On the night of December 12, 1995, Appellant Edwin Hart Turner (hereinafter Turner) and Paul Murrell Stewart (hereinafter Stewart) had been drinking beer and smoking marijuana while driving around Leflore and Carroll Counties in Stewart's automobile. Around midnight the vehicle veered off the gravel road and became stuck in a ditch. Turner and Stewart walked to the nearby home of Doyle Carpenter, a friend of Turner's. Carpenter carried the pair to Turner's home when the trio were unable to free the automobile from the ditch. Once back at Turner's house, Turner and Stewart decided to rob some place. The crimes at issue in the present case occurred at two separate convenience stores approximately four miles apart on U.S. Highway 82 in Carroll County, Mississippi.

¶ 7. The crime spree began at Mims Turkey Village Truck Stop. Turner and Stewart went into the store wearing masks and carrying high-powered rifles. Turner used a 6mm rifle, while Stewart carried a .243 rifle with a scope attached. Turner and Stewart walked into the store and then Turner shot Eddie Brooks, the store clerk, in the chest. Eddie Brooks slumped behind the counter and fell to the floor.

¶ 8. Turner and Stewart went behind the counter to the cash register but could not get it to open. The two men became angry when they could not open the cash register. Stewart shot the cash register, but it still would not open. Turner, in a rage, struck the butt of his rifle on the cash register. Turner then shot at the cash register to no avail. Turner then became enraged. Turner placed the barrel of his gun inches from Eddie Brooks' head and pulled the trigger, killing Mr. Brooks.

¶ 9. Unsuccessful in their attempt to get any money, the two men immediately drove to Mims One Stop. Everett Curry was standing next to a gas pump outside. There were several people inside. Stewart went inside the store to rob it while Turner made Everett Curry get on the ground by threatening him with his 6mm rifle. As Curry was pleading for his life, Turner shot him in the head, killing him. Meanwhile, Stewart was ordering the clerk to fill a paper bag with money.

¶ 10. After killing Everett Curry, Turner then ran into the store and ordered everyone to get down. Turner then pointed a gun at a man in the store. Stewart urged Turner not to kill anyone else since they already had the money that they came for. Turner and Stewart then left the store and returned to Turner's house.

¶ 11. Turner and Stewart put the guns inside Turner's house. Stewart left his white hockey mask on the back seat of Turner's car. Stewart then counted the money (about $400.) which they then split, while Turner prepared shrimp and cinnamon rolls which the two then ate. Turner and Stewart awoke later that morning to several law enforcement officers knocking on the door. The officers discovered two high-powered rifles in Turner's house. Turner and Stewart were then arrested and brought to Carroll County Sheriff C.D. Whitfield. Stewart gave a full confession outlining the above events. The Sheriff then got a search warrant for Turner's house.

¶ 12. Turner was tried and found guilty of two counts of capital murder while in the commission of armed robbery. The jury then imposed the death penalty for both counts of capital murder. This appeal followed.

DISCUSSION OF THE ISSUES

I. THE ARREST OF TURNER WAS ILLEGAL PURSUANT TO MISS. CODE ANN. § 99–3–7 AND SUBSEQUENT SEARCH AND SEIZURE VIOLATED THE FOURTH AND FOURTEENTH AMENDMENTS TO THE UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION AND THEIR MISSISSIPPI CONSTITUTIONAL COUNTERPARTS.

A. WARRANTLESS ARREST

¶ 13. Turner argues forcefully that the information possessed by the law enforcement officers at the time that they went to Turner's home, handcuffed both Turner and Stewart, and drove them away in police cars from the Turner home was insufficient to establish the requisite probable cause needed to arrest Turner without a warrant. Turner argues that the law enforcement officers knew the following: 1. They knew first of all that two persons were dead and that they had met their end by use of a deadly weapon. There was however nothing connected to the dead bodies that signaled Hart Turner's involvement. 2. They recovered from the scenes hulls and casings presumably ejected from the deadly weapons. There was nothing unique about the physical evidence that signaled Hart Turner's involvement. 3. They knew at the first murder scene that no eyewitnesses observed the killing or the perpetrators, nor gave a description of the offender's vehicle. Nothing signaled Hart Turner's involvement. 4. They knew at the second murder scene that no eyewitness could identify the perpetrators as their faces were concealed with masks. No one recognized the masks [as] belong[ing] to Hart Turner and no one got a view of the getaway vehicle license plate which again did not signal Hart Turner's involvement. In fact the best anyone ever came up with was a gray or silver car and Turner owned a dark blue car. 5. They discovered a wallet, purportedly of the victim of the second homicide, yet no fingerprint analysis was done to manifest Hart Turner's involvement. 6. No fingerprint evidence linked Turner to either of the homicides. 7. No one identified Hart Turner's voice as having been behind the mask. The perpetrators did not leave any of their own blood evidence to connect them nor had they left behind any other physical evidence demonstrating they had been there, eg. footprints, tire tracks. 8. No one recognized the rifles used in the killings. 9. At this time, roughly 2:15a.m. they had obviously not had the benefit of Paul Stewart's admissions and confessions, nor any other confidential informant information alerting them to Hart Turner. 10.They knew that the perpetrators were white males and one was taller than the other.

¶ 14. Conversely, the State argues that the law enforcement officers had a great deal of evidence linking Turner to the two capital murders. In the present case, the officers knew that two murders a few miles apart on Highway 82 had taken place. Two eyewitnesses remembered that two white males of average height, one taller than the other, had perpetrated these crimes. The night manager saw one white male with a gun holding up a patron of his store who was outside pumping gas, and another white male enter the store with a gun wearing a white hockey mask. What the white male standing outside the gas station at the second crime scene was (or was not) wearing is the subject of much contention and debate in the trial record and for that reason will not be assumed by this Court.

¶ 15. Both sides cite Rome v. State, 348 So.2d 1026 (Miss.1977), for support of their position as to this issue. In Rome, the facts were as follows: The Stone County Courthouse was burglarized at night and almost $2000.00 was stolen. Id. at 1027. A policeman on foot patrol in the area heard a noise coming from the courthouse area and spotted two men at which time he made his presence known and ordered them to halt. Id. The two men split up—one was apprehended and the other got away. Id. Officer Griffin was called in for assistance by the arresting officer. Id.

¶ 16. Officer Griffin, after assisting the arresting officer, went in his patrol car back to the same area of the courthouse and began patrolling it. Id. At this time, Officer Griffin did not know that the courthouse had been burglarized, only that two men had been spotted in the area acting suspiciously and one had run when the police officer ordered them to halt and had gotten away. Id.

¶ 17. This Court found that, [T]he record is devoid of any proof that Officer Griffin, at the time he arrested Rome, had any reasonable ground to ‘suspect and believe’ that Rome had committed the ‘felony’ as required by Miss.Code Ann. § 99–3–7.[ ]. According to Griffin, he did not know that the courthouse had been burglarized when he took Rome to the police station.... Based upon the totality of the circumstances of this case, we cannot hold that Griffin had sufficient evidence to believe that Rome had committed a felony.... To uphold the arrest would lay down the unacceptable rule that law officers may arrest any stranger deemed by them to be suspect of having committed an unknown crime, and then hunt a crime to be charged against such a citizen. Id. at 1028–29.

¶ 18. While Rome is good law and is very instructive, the facts in the present case do not support a similar finding of reversal as was the decision in Rome. This Court in Rome stated the correct test which we are to apply to arrests without a warrant. Id. at 1027. This Court stated, “[p]robable cause means more than bare suspicion, but does not necessarily require sufficient evidence to support a criminal conviction.” (quoting Powe v. State, 235 So.2d 920 (Miss.1970)).

¶ 19. Here, two white males in a Toyota with a Georgia plate, tag number FGZ–818, had evaded Leflore County authorities the night before the early morning killings. Leflore County Sheriff Ricky Banks obtained a John Doe arrest warrant for the two white males. High powered rifle hull casings were found at the scene of the crime. Doyle Carpenter told authorities that he gave Turner and another white male a ride to Turner's home when the Toyota with a Georgia plate, tag number FGZ–818 they were riding in, became stuck in the ditch earlier in the evening. Sheriff Whitfield remembered Hart Turner as a white male who had a history of violence.

¶ 20. The Toyota stuck in the ditch had a Pillow Academy bumper sticker on it which was traced to Stewart, a young white male. There was a trail of footprints leading from the abandoned vehicle to a house up the gravel road that belonged to Doyle Carpenter. Doyle Carpenter described the two men to the law enforcement officers and told them that he had carried them to Turner's residence that night when the three of them could not dislodge the car from the ditch. Sheriff Whitfield asked his deputies to drive to Turner's residence and tell the two men he wanted to talk to them. When Deputy R.W. Miller and Milton Smith arrived at Turner's home, they looked in the window of Turner's Honda Accord. They observed a white hockey mask (consistent with the one described by the witnesses at the second crime scene) lying on the back seat of the car and noticed a live rifle cartridge lying on the car's floorboard.

¶ 21. The officers knocked on the door at Turner's house. Turner opened the door at which time boxes of rifle shells were visible lying on the floor inside the house. Turner then asked the law enforcement officers inside. Once inside, the officers asked Turner whether anyone else was in the house to which Turner replied that his buddy was in the back bedroom. Turner started back towards that bedroom but was stopped by the law officers who then went back to the bedroom themselves. They found Stewart in the bed and observed two rifles lying on two couches in that bedroom.

¶ 22. Then both Turner and Stewart were handcuffed, wearing nothing but their underwear. Turner and Stewart were Mirandized according to the arresting officer, and Turner refused to talk. The question is were they under arrest at this time when they were handcuffed and led away to the police patrol cars?

¶ 23. This Court in Riddles v. State, 471 So.2d 1234 (Miss.1985), outlined the test to be used here. If the potential arrestee “could not have believed under such circumstances that he was free to leave,” then the arrestee is in fact under arrest. Given the facts of the present case, Turner and Stewart could not reasonably have believed that they were free to leave. Therefore, they were under arrest when they were handcuffed at Turner's house by the law enforcement officers and carried away in police cars. [2]

¶ 24. The issue then becomes, was this an illegal arrest since the officers had no arrest warrant at this time? Mississippi Code Ann. § 99–3–7(1) (Supp.1998), regulates when arrests may be made without a warrant:

An officer or private person may arrest any person without warrant, for an indictable offense committed, or a breach of the peace threatened or attempted in his presence; or when a person has committed a felony, though not in his presence; or when a felony has been committed, and he has reasonable ground to suspect and believe the person proposed to be arrested to have committed it; or on a charge, made upon reasonable cause, of the commission of a felony by the party proposed to be arrested. And in all cases of arrests without warrant, the person making such arrest must inform the accused of the object and cause of the arrest, except when he is in the actual commission of the offense, or is arrested on pursuit. .... (emphasis added).

¶ 25. According to Stewart's testimony at the trial, the police officers told them that morning that they were under arrest and then sat them down in the living room and began asking them questions after being handcuffed. Stewart testified the police wanted them to sign a piece of paper (presumably a waiver of rights form). Turner and Stewart refused to sign it. Importantly, the record does not reflect that either Turner or Stewart requested to speak with an attorney. The officers told Turner and Stewart at that time that they suspected them of having been involved in the tragic deaths of the two victims in this case, Curry and Brooks.

¶ 26. The officers in the present case complied with the statute, Miss.Code Ann. § 99–3–7, in arresting Turner without an arrest warrant. First, a felony had been committed. Two men had been slain in the process of two separate armed robberies. Secondly, a large body of evidence was known at the time of the arrest, including: 1) an abandoned vehicle which fit the description down to the exact license tag number of Stewart's Toyota which had been driven recklessly in Leflore County the night before the early morning killings which had resulted in two John Doe arrest warrants for two young white males; 2) a trail of footprints from that abandoned vehicle which led to Doyle Carpenter's house; 3) Doyle Carpenter having told the officers that he had carried Turner and a friend of Turner's to Turner's house around midnight December 12, 1995; 4) upon the officers arriving at the Turner house, they noticed a white hockey mask lying on the back seat of Turner's vehicle as well as a live rifle round lying on the floorboard in plain view—viewed through the window of the car; 5) upon knocking on the door and Turner opening it, a box of rifle shells were seen in plain view; 6) Turner invited the officers into the house and upon entering the house more shells were visible in plain view lying on the floor; 7) when asked if Turner was alone, Turner replied that his buddy was in the back bedroom, and upon going to the back bedroom to find this person, Stewart was found in the bed and two rifles were seen in plain view lying on two couches in the bedroom.

¶ 27. All of this evidence, coupled with the knowledge that two murders had occurred in the early morning hours of that same day with a high-powered rifle, perpetrated by two young white males (one wearing a white hockey mask) amounted to “reasonable ground[s] to suspect and believe the person proposed to be arrested to have committed it [the felony]....” Miss.Code Ann. § 99–3–7(1) (Supp.1998). Therefore, Turner's arrest without a warrant was legal. This result is properly reached even disregarding the much contested evidence concerning whether Turner was wearing a white towel around his neck during the murders in the early morning hours of December 13, 1995, as testified to by some witnesses.

¶ 28. Furthermore, even had the arrest been found improper (which it has not), that error would have been harmless since no evidence flowed from that arrest which was crucial to the conviction.

B. SEARCH WARRANT

¶ 29. Having determined that the arrests were legal, the next issue is whether the seizure of the evidence by means of a search warrant later that same day was proper. Turner argues that since the police had no probable cause to arrest him that morning, it follows that any evidence derived as a result of the illegal arrest is tainted. At the time that the officers restrained Turner's and Stewart's movement in the house they were under arrest. Riddles v. State, 471 So.2d 1234 (Miss.1985). At that moment, the officers would have been justified in seizing the evidence which was in plain view. However, out of an abundance of caution they did not seize or even touch the items of evidence in the house.

¶ 30. Turner's argument fails due in large part to the fact that his arrest was legal. Therefore, the evidence discovered as a result of that arrest was not tainted. Furthermore, by the time the affidavit for a search warrant was presented to the magistrate more evidence had been obtained, not the least of which was the confession of Stewart, Turner's partner in crime.

¶ 31. This Court stated in Fisher v. State, 690 So.2d 268, 274 (Miss.1996), that “[a] trial judge enjoys a great deal of discretion as to the relevancy and admissibility of evidence. Unless the judge abuses this discretion so as to be prejudicial to the accused, the Court will not reverse this ruling.” In Branch v. State, 347 So.2d 957, 958 (Miss.1977), this Court stated, “the burden is on the appellant to demonstrate some reversible error to this Court. It is the appellant's duty to see that all matters necessary to his appeal, such as exhibits, witnesses' testimony, and so forth, are included in the record, and he may not complain of his own failures in that regard.”

¶ 32. The trial judge, in regard to Turner's Motion to Suppress Evidence, concluded: [T]he Sheriff went to the, went and prepared an affidavit and search warrant together with the underlying facts and circumstances. He has testified here today. The Court has examined the underlying facts and circumstances and finds no material contradiction between the facts, underlying facts and circumstances in the affidavit, accompanying the affidavit, or with what Sheriff Whitfield testified to today. Although the Court finds it's not necessarily material as to whether or not those statements were true, the question is were the facts presented to the Magistrate sufficient for her to have probable cause to issue the warrant. I find the material facts are true though, and I find that the underlying facts and circumstances presented to the Magistrate are more than adequate to give her probable cause to issue the warrant. And therefore, the Motion to Suppress is overruled.

¶ 33. The trial judge allowed Turner's counsel ample opportunity to cross-examine the State's witnesses about the events surrounding the discovery of the rifles and the clothing. Turner failed to establish any fault with the law enforcement officers' work. For these reasons, the arrest of Turner was legal pursuant to Miss.Code Ann. § 99–3–7 (Supp.1998), and the subsequent search and seizure pursuant to a search did not violate the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution and their Mississippi Constitutional counterparts.

II. COUPLING A VAGUE INDICTMENT WHICH DID NOT FAIRLY APPRISE THE DEFENDANT WITH NOTICE OF WHICH UNDERLYING FELONY WOULD BE PURSUED ALONG WITH A DUPLICITOUS JURY INSTRUCTION VIOLATED THE SIXTH, EIGHTH AND FOURTEENTH AMENDMENTS.

¶ 34. The indictment in the present case is as follows: The Grand Jurors of the State of Mississippi, taken from the body of good and lawful citizens of said [Carroll] County, elected, summoned, empaneled, sworn and charged to inquire in and for the county aforesaid, at the term aforesaid of the Court aforesaid, in the name and by the authority of the State of Mississippi, upon their oath present that

Count I - Edwin Hart Turner late of the First Judicial District of Carroll County, Mississippi, on or about the 13 th day of December, 1995, in the county, judicial district, and state aforesaid, and within the jurisdiction of this Court, while acting in concert with and/or aiding, abetting, or assisting one Paul M. Stewart, did unlawfully, wilfully, feloniously, and either with or without the deliberate design to effect death, kill and murder Eddie Brooks, a human being, by shooting him with a rifle, while engaged in the commission of the felony crime of armed robbery in violation of Miss.Code Ann. Section 97–3–79 and Section 97–3–19(2)(e) (as amended) and constituting a series of related acts or transactions or a common scheme or plan, and against the peace and dignity of the State of Mississippi.

Count II - Edwin Hart Turner late of the First Judicial District of Carroll County, Mississippi, on or about the 13 th day of December, 1995, in the county, judicial district, and state aforesaid, and within the jurisdiction of this Court, while acting in concert with and/or aiding, abetting, or assisting one Paul M. Stewart, did unlawfully, wilfully, feloniously, and either with or without the deliberate design to effect death, kill and murder Everett Curry, a human being, by shooting him with a rifle, while engaged in the commission of the felony crime of armed robbery in violation of Miss.Code Ann. Section 97–3–79 and Section 97–3–19(2)(e) (as amended) and constituting a series of related acts or transactions or a common scheme or plan, and against the peace and dignity of the State of Mississippi.

¶ 35. Turner's argument on this issue centers on the premise that on Count II, he is unaware (based upon the indictment) whether the death of Everett Curry was effected during the armed robbery of Everett Curry or of the gas station where Curry was outside pumping gas. At trial, Turner contends the State introduced evidence of two separate armed robberies: one of Curry and one of the gas station. Turner argues that since the proof at trial went to two separate armed robberies at the scene where Everett Curry was killed, and since the indictment does not apprise Turner of which alleged armed robbery is the basis of the underlying felony, it cannot be said with any certainty that he had fair notice with which to prepare his defense. For support of this argument, Turner relies heavily upon State v. Berryhill, 703 So.2d 250 (Miss.1997).

¶ 36. Berryhill is readily distinguishable from the facts in the instant case. In Berryhill, Anthony Berryhill was indicted for capital murder while engaged in the commission of a burglary. Id. at 252. In Berryhill, this Court held that “capital murder indictments that are predicated upon the underlying felony of burglary must assert with specificity the felony that comprises the burglary.” Id. at 258. However, this Court in Berryhill also distinguished capital murder cases predicated upon burglary from all other capital cases:

Simply put, the level of notice that would reasonably enable a defendant to defend himself against a capital murder charge that is predicated upon burglary must, to be fair, include notice of the crime comprising the burglary. Burglary is unlike robbery and all other capital murder predicate felonies in that it requires as an essential element the intent to commit another crime. While it is true that the general rule finds indictments that track the language of the criminal statute to be sufficient, Ward v. State, 479 So.2d 713, 715 (Miss.1985)(charging aggravated assault), the fairer rule in case of capital murder arising out of burglary is that which we intimated in Moore, and would require the indictment to name the crime underlying the burglary in addition to tracking the capital murder statute.... Id. at 256. (emphasis added).

¶ 37. This Court in Berryhill very clearly addressed Turner's issue here. Only in capital murder cases predicated upon the felony of burglary will this Court require a more detailed indictment: to the extent of noticing the defendant with what felony was intended in the burglary. This is a capital case with the predicate felony being armed robbery. The indictment certainly put Turner on notice of this fact and was, therefore, adequate.

¶ 38. A more analogous case to the present one is Mackbee v. State, 575 So.2d 16 (Miss.1990). In that case, Mackbee's capital murder indictment allge[d] that the murder of Montgomery was committed while Mackbee was ‘engaged in the commission of the crime of robbery’.... Mackbee argue[d] that the capital murder indictment was void for failure to specify overt facts committed during the course of the robbery.... Mackbee contend[ed] the lack of notice concerning the underlying felony render [ed] his conviction void. Id. at 34–35.

¶ 39. This Court held that “[o]n the merits, Mackbee's argument ... fails because the indictment further read, ‘contrary to and in violation of § 97–3–19(2)(e) of the Mississippi Code of 1972’ which is the statutory provision for capital murder.” Id. at 35. Similarly, in the present case, the indictment contains the important “in violation of ... § 97–3–19(2)(e)” language. Id. Furthermore, as in Mackbee, since Turner failed to raise this issue at the trial level, it is barred under Miss.Code Ann. § 99–7–21(Rev.1994), which states: All objections to an indictment for a defect appearing on the face thereof, shall be taken by demurrer to the indictment, and not otherwise, before the issuance of the venire facias in capital cases, and before the jury shall be impaneled in all other cases, and not afterward. The court for any formal defect, may, if it be thought necessary, cause the indictment to be forthwith amended, and thereupon the trial shall proceed as if such defect had not appeared.

¶ 40. Not only is Turner's argument barred since he failed to raise any objection at the trial level, but it also fails on the merits.

III. THE LOWER COURT ERRED IN DENYING TURNER'S PROPOSED LESSER INCLUDED OFFENSE INSTRUCTION.

¶ 41. Turner argues that the jury should have been given a lesser included offense instruction on simple murder. Turner contends, based on the testimony of Stewart as to Count I of the indictment, that the clerk was shot prior to any robbery or attempted robbery. The moment that Turner entered the store was when the shot was fired. Turner claims that whether or not an armed robbery occurred after that time is not the issue.

¶ 42. Similarly, Turner contends that a lesser included offense instruction of simple murder should also have been given as to Court II. Turner again relies on Stewart's testimony that before Stewart could even make his way into the store and brandish his weapon, Turner had killed Everett Curry, a non-employee pumping gas outside the store. Turner argues that it is plausible that the jury could have found that Everett Curry was not killed in furtherance of a robbery of him or the store.

¶ 43. The State contends that this issue is totally without merit. The State points to the fact that the trial judge heard extensive arguments from both sides as to whether this lesser included offense instruction should be given, and he found that the record was devoid of any proof which would warrant such an instruction.

¶ 44. This Court in Ormond v. State, 599 So.2d 951, 960–61 (Miss.1992), stated [a] lesser included offense instruction is proper only if the record supports finding an evidentiary basis for the instruction. Mease v. State, 539 So.2d 1324, 1330 (Miss.1989); Lee v. State, 469 So.2d 1225, 1230 (Miss.1985); Ruffin v. State, 44[444] So.2d 839, 840 (Miss.1984). Such instructions should not be indiscriminately granted, Mease, 539 So.2d at 1330, nor should they be based upon pure speculation, Fairchild v. State, 459 So.2d 793, 801 (Miss.1984); Mease, 539 So.2d at 1330. Under the appropriate standard: a lesser included offense instruction should be granted unless the trial judge—and ultimately this Court—can say, taking the evidence in the light most favorable to the accused and considering all reasonable favorable inferences which may be drawn in favor of the accused from the evidence, that no reasonable jury could find the defendant guilty of the lesser included offense (and conversely not guilty of at least one essential element of the principal charge). Mease, 539 So.2d at 1330 ( quoting Harper v. State, 478 So.2d 1017, 1021 (Miss.1985)).

¶ 45. Applying these criteria to the facts in the present case, no error was committed by the trial judge in denying the lesser included offense charge of simple murder. The facts from the record simply do not support that theory of the case. The testimony of Stewart—the same testimony Turner relies upon as the basis of his argument for the lesser included offense of simple murder instruction—clearly details how the intent and purpose of Turner in the early morning hours of December 13, 1995, was to rob a store.

¶ 46. This testimony from Stewart as to intent was uncontradicted by any other testimony. Therefore, taking this uncontradicted testimony as true, it was Turner's specific intent throughout the events of those early morning hours, up to and including the times of both murders, to commit armed robbery.

¶ 47. Furthermore, Turner's argument fails on this issue because Mississippi recognizes the “one continuous transaction rationale” in capital cases. West v. State, 553 So.2d 8 (Miss.1989). There this Court stated: In Pickle v. State, 345 So.2d 623 (Miss.1977), we construed our capital murder statute and held that ‘the underlying crime begins where an indictable attempt is reached....’ 345 So.2d at 626; see also Layne v. State, 542 So.2d 237, 243 (Miss.1989); Fisher v. State, 481 So.2d 203, 212 (Miss.1985); and Culberson v. State, 379 So.2d 499, 503–04 (Miss.1979).... An indictment charging a killing occurring ‘while engaged in the commission of’ one of the enumerated felonies includes the actions of the defendant leading up to the felony, the attempted felony, and flight from the scene of the felony. West v. State, 553 So.2d at 13.

¶ 48. Applying one continuous transaction rationale to the evidence in the present case, the actions of Turner were all related to, and motivated by his desire to rob someone in those early morning hours of December 13, 1995. Therefore, the time of death of Eddie Brooks and Everett Curry—be it before or after the money was taken—is irrelevant. It is clear that these two innocent men died during the commission of armed robberies perpetrated by Stewart and Turner. For these reasons, this issue is without merit.

IV. THE PROSECUTOR ENGAGED IN WHOLLY IMPROPER CROSS–EXAMINATION OF SENTENCING PHASE WITNESSES SOLELY FOR THE PURPOSE OF INJECTING PREJUDICE TO INFLAME THE JURY.

¶ 49. Turner argues that during the sentencing phase, the State, on cross-examination of Turner's witnesses, brought up instances of Turner's conduct of which he was never convicted solely for the improper purpose of inflaming and prejudicing the jury. Specifically, according to Turner, the prosecutor sought to elicit responses from the witnesses concerning Turner's alleged beating of his mother, threats to kill his stepfather, and the contacting of local law enforcement officers in response to these alleged threats and other uncharged alleged misconduct. By failing to object to this questioning of these witnesses, Turner has waived the issue for appeal.

¶ 50. Nevertheless, addressing the merits of the claim, Turner placed his character into evidence in the sentencing phase of the trial. The State was entitled to ask the mitigating witnesses questions that would rebut their testimony that he was the victim of abuse, not the abuser. The State is allowed to rebut mitigating evidence through cross-examination, introduction of rebuttal evidence or by argument. Bell v. State, 725 So.2d 836, 1998 WL 334709 (Miss.1998); Davis v. State, 684 So.2d 643, 655 (Miss.1996).

¶ 51. The trial judge allowed Turner to put on witnesses who testified as to what a wonderful child he was and as to how this heinous crime was everyone's fault but Turner's. In response to this, on cross-examination, the State then is allowed to bring up the not so favorable instances from Turner's past, such as his threats of abuse towards his mother and step-dad. Therefore, Turner's arguments on this issue are meritless.

V. THE TRIAL COURT ERRED IN EXCLUDING RELEVANT MITIGATION EVIDENCE IN VIOLATION OF THE FEDERAL AND STATE CONSTITUTIONS AND STATE LAW.

¶ 52. Turner argues that during the sentencing phase of the trial, the defense attempted to elicit testimony from three mitigation witnesses related to the defendant's upbringing and relationship with his mother. The prosecution objected on the grounds of hearsay, and the trial court sustained the objections. Turner claims that in light of Green v. Georgia, 442 U.S. 95, 97, 99 S.Ct. 2150, 60 L.Ed.2d 738 (1979) (per curiam), the action by the trial court in sustaining the objections was erroneous.

¶ 53. This Court in Ballenger v. State, 667 So.2d 1242, 1263 (Miss.1995) cert. denied, 518 U.S. 1025, 116 S.Ct. 2565, 135 L.Ed.2d 1082 (1996), held that it was too broad an interpretation of Green to say merely that a state evidentiary rule cannot operate to exclude otherwise relevant mitigating evidence. This Court has held that Green v. Georgia does not open the door to just any type evidence in mitigation; “unique circumstances” must exist to overcome the evidentiary rule against hearsay. Ballenger, 667 So.2d at 1262–63.

¶ 54. Turner has not pointed out what special or unique circumstances make the hearsay he wanted to introduce in mitigation admissible. He points to three instances in the sentencing phase where the trial court sustained objections to hearsay by the prosecution. These came during the testimony of Marsha Sanders Shaw, Turner's aunt, Pamela Sanders Crestwell, Turner's aunt, and Kenneth Crestwell, Turner's uncle.