Executed June 16, 2011 06:24 p.m. CDT by Lethal Injection in Texas

21st murderer executed in U.S. in 2011

1255th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

5th murderer executed in Texas in 2011

469th murderer executed in Texas since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(21) |

Lee Andrew Taylor W / M / 20 - 32 |

Donta Green B / M / 22 |

Citations:

Taylor v. Thaler,397 Fed.Appx. 104 (5th Cir. 2010). (Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

A medium pizza with cheese, beef, black olives and mushrooms, four soft tacos, large bowls of fried okra and one pint of Blue Bell Ice Cream.

Last Words:

"There are 300 people on death row, and not every one of them is a monster. The state of Texas is carrying out a very inhuman and unjust situation. It's not right to kill anybody, not the way I did it, or the way it's being done to me. Everyone changes, right? Life is about experience, and people change." The condemned man then looked to the victim's family. "For all you people," I defended myself when I killed your family member. Prison is a bad place. I didn't set out to kill him. But he would not have been in prison if he was a saint. I hope y'all understand that. I hope you don’t find satisfaction in this, watching a human being die.” While Taylor continued talking to the victim's family, the lethal injection was started. As the drug was taking effect, he said, "I'm ready to teleport".

Internet Sources:

Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Executed Offenders (Taylor)

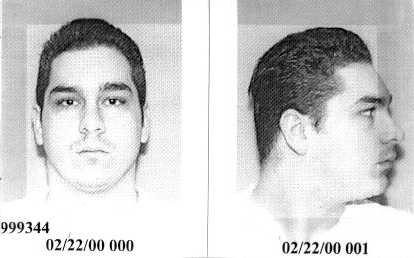

Taylor, Lee Andrew

Date of Birth: 01/08/1979

DR#: 999344

Date Received: 02/22/2000

Education: 9 years

Occupation: stocker, laborer

Date of Offense: 04/01/1999

County of Offense: Bowie

Native County: Galveston

Race: White

Gender: Male

Hair Color: Brown

Eye Color: Brown

Height: 5' 09"

Weight: 207

Prior Prison Record: #765153 on 10/29/96, Life sentence for 1 count Aggravated Robbery.

Summary of incident: On 04/01/99, during the daytime, at TDCJ-ID Telford Unit dayroom, Taylor fatally stabbed an adult black male offender multiple times with an 8" home-made weapon. Taylor and one co-defendant had engaged in a fight with the victim due to racial tension between Taylor and the victim. Taylor was a member of the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas (a recognized security threat group).

Co-Defendants: Richbourg, Daniel.

Friday, June 10, 2011

Media Advisory: Lee Taylor scheduled for execution

AUSTIN – Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott offers the following information about Lee Andrew Taylor, who is scheduled for execution after 6 p.m. on Thursday, June 16, 2011. Taylor, a prison inmate who was serving a life sentence for aggravated robbery that resulted in the death of an elderly man, was convicted and sentenced to death in a Bowie County state district court for the murder of another prison inmate, Donta Greene.

FACTS OF THE CRIME

During the evening hours of March 31, 1999, in the Barry Telford state prison in New Boston, property was stolen from the cell of inmate Daniel Richbourg. Inmate Donta Greene participated in the theft and took some of Richbourg’s property. During the night of March 31, 1999, Taylor and Richbourg made plans to seek revenge for the theft.

The next morning, in the early morning hours of April 1, 1999, the inmates were released from their cells to go to breakfast. When Taylor was released from his cell, he walked just past Greene, then turned and struck Greene with his fist. Taylor then grabbed Greene around the head, held him in a headlock, and repeatedly stabbed him in the chest with a rod-like shank—a prison-made stabbing device that resembled an ice pick. Afterwards, Taylor shouted at Greene, “That’s what you get for stealing....”

During the stabbing, Richbourg brandished his own shank—a plexiglass blade-like weapon—to chase away other inmates attempting to help Greene so Taylor could complete the murder. At no time did Greene himself ever have a weapon. After the stabbing, Taylor was euphoric and repeatedly bragged that he must have stabbed Greene twenty-five to thirty times. Taylor inflicted thirteen actual stab wounds and numerous scratches on Greene’s body. Several of the puncture wounds were fatal.

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

On November 4, 1999, Taylor was indicted by a Bowie County grand jury for capital murder in the death of Donta Greene. On Feb. 18, 2000, a jury found Taylor guilty of the capital murder and the court sentenced Taylor to death. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed Taylor’s conviction and sentence on December 11, 2002.

Taylor filed a state application for writ of habeas corpus in the trial court on November 30, 2001. The trial court entered findings of fact and conclusions of law recommending that Taylor be denied relief. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals adopted the trial court’s findings and conclusions and denied Taylor habeas relief on March 31, 2004.

Taylor filed a federal habeas petition in a U.S. district court on March 30, 2005. The court then issued a stay so that Taylor could exhaust a mental-retardation claim in state court. On July 11, 2008, Taylor’s attorney informed the court that a doctor determined Taylor was not mentally retarded. On July 28, 2008, the court lifted the stay. On August 31, 2009, the court denied Taylor federal habeas relief. Taylor appealed this decision to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. The Fifth Circuit court affirmed the federal district court’s decision on October 7, 2010. Taylor filed a petition for writ of certiorari in the U.S. Supreme Court on January 5, 2011. The Supreme Court denied the petition on April 18, 2011.

EVIDENCE OF FUTURE DANGEROUSNESS

Taylor was convicted of aggravated assault and sentenced to life imprisonment for a Nov. 17, 1995, incident in which a grandfather and his wife were beaten at their home. The grand father died a short time later in a hospital.

Texas Execution Information Center by David Carson.

Lee Andrew Taylor, 32, was executed by lethal injection on 16 June 2011 in Huntsville, Texas for the murder of a fellow prison inmate.

In November 1995, Taylor, then 16, beat an elderly man and woman during a robbery of their home. The man, 79-year-old John Hampton, subsequently died in the hospital. Taylor was convicted of aggravated robbery and sentenced to life in prison.

On 31 March 1999, in the Telford state prison in Bowie County, some property was stolen from the cell of inmate Daniel Richbourg, 29. Inmate Donta Greene participated in the theft. On 1 April, as some inmates were leaving their cells to go to breakfast, Taylor, then 20, walked past Greene, then turned around and struck him with his fist. Taylor then grabbed Greene and held him in a headlock, then stabbed him in the chest thirteen times with an 8" home-made weapon. Meanwhile, Richbourg brandished his own blade made from plexiglass to keep other inmates from coming to Greene's aid. Greene was unarmed. After the stabbing, Taylor shouted, "That's what you get for stealing ..."

The prosecution asserted that, in addition to the theft incident, Greene's killing was the product of racial tension. Taylor was a member of the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas, while Greene was black.

A jury convicted Taylor of capital murder in February 2000 and sentenced him to death. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the conviction and sentence in December 2002. All of his subsequent appeals in state and federal court were denied.

At the time of the killing, Daniel Joseph Richbourg Jr. was serving a 12-year sentence for burglary of a building. He was convicted of murder in Greene's case and was given a 48-year sentence. If he serves his term to completion, he will be 80 when he is discharged.

On a web site operated by opponents of the death penalty, Taylor admitted killing Greene, but stated that the killing was done in self-defense. "... on April 1st 1999 I fought off 8 black men with a shank," he wrote. "Defending myself against 8 men older and stronger, fighting for my life against a premeditated attack, I defended myself ... the result - I killed one of them."

Taylor began his last statement at his execution by protesting the Texas death penalty. "There are 300 people on death row, and not every one of them is a monster," he said. "The state of Texas is carrying out a very inhuman and unjust situation. It's not right to kill anybody, not the way I did it, or the way it's being done to me. Everyone changes, right? Life is about experience, and people change."

The condemned man then looked to the victim's family. "For all you people," he said, "I defended myself when I killed your family member. Prison is a bad place. I didn't set out to kill him. But he would not have been in prison if he was a saint. I hope y'all understand that." While Taylor continued talking to the victim's family, the lethal injection was started. As the drug was taking effect, he said, "I'm ready to teleport". He was pronounced dead at 6:24 p.m.

"Texas executes man for prison stabbing," by Corrie MacLaggan. (June 16, 2011 8:14pm EDT)

AUSTIN, Texas (Reuters) - A man convicted of fatally stabbing a fellow inmate in a state prison in 1999 was executed in Texas on Thursday evening by lethal injection.

Lee Taylor was to be the second man put to death in Texas this week. But on Wednesday, the U.S. Supreme Court stayed the execution of John Balentine, who fatally shot three teenagers in Amarillo in 1998. Balentine had raised an issue about whether he has a right to be represented by a lawyer in a post-conviction state hearing challenging the effectiveness of his lawyers at trial.

Taylor, 32, used an ice-pick-like weapon made in prison to stab fellow inmate Donta Greene multiple times in what the Texas Department of Criminal Justice describes as a fight stemming from racial tension. Taylor, who is white, was a member of the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas, according to the department. Greene was black.

Taylor said shortly before he died that he was acting in self-defense. "I am sorry that I killed him but he would not have been in prison if he was a saint," Taylor said, according to Jason Clark, a spokesman for the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Clark said that Taylor also talked about the death penalty itself, saying that not everyone on death row is "a monster." "I hope people understand the grave injustice by the state," Clark quoted Taylor as saying. "It's not right to kill anybody just because I killed your people. Everyone changes, right?"

At the time of the stabbing at the northeast Texas prison, Taylor was serving a life sentence for an aggravated robbery in which an elderly man died, according to the state attorney general's office.

Taylor was pronounced dead at 6:24 p.m. Thursday, Clark said. His last meal included pizza, soft tacos, fried jalapeno sticks, french fries, fried okra and ice cream, Clark said. One of the last things Taylor said was: "I'm ready to teleport," according to Clark.

Taylor was the fifth inmate executed in Texas this year. Alabama on Thursday executed a man for brutally murdering a 70-year-old woman in 1995. Those two executions brought to 22 the number of people put to death in the United States so far this year. Texas has executed more than four times as many people as any other state since the death penalty was reinstated in the United States in 1976, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. The next execution in Texas is scheduled for Tuesday.

"Convicted killer of fellow inmate executed Thursday," by Brandon Scott. (Thu Jun 16, 2011, 10:59 PM CDT) HUNTSVILLE — A member of the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas prison gang was put to death Thursday evening with few thoughts left unspoken. Lee Andrew Taylor, 32, spoke candidly to his witnesses before being pronounced dead by lethal injection at 6:24 p.m. Thursday.

“There are 300 people on death row and not every one of them is a monster,” said Taylor, who was sentenced to death for killing a fellow inmate in 1999. “The state of Texas is carrying out a very inhumane and unjust situation. It’s not right to kill anybody, not the way I did it or the way it’s being done to me. “Everyone changes right? Life is about experience and people change.” Taylor began serving a life sentence in 1996 for one count of aggravated robbery which resulted in one fatality.

Almost three years later, Taylor engaged in a fight with fellow inmate Donta Greene at the Telford Unit near Texarkana, in what the Texas Department of Criminal Justice referred to as an incident of racial tension. Taylor stabbed Greene 15 times in the heart with a homemade weapon. As lethal drugs were injected into his veins, Taylor looked to Greene’s family to plead his case. “For all you people, I defended myself when I killed your family member,” Taylor said. “Prison is a bad place. I didn’t set out to kill him. But he would not have been in prison if he was a saint. I hope ya’ll understand that.”

The Aryan Brotherhood is a white prison gang with roughly 19,000 members in and out of prison. Though the gang makes up less than one percent of the prison population, it is responsible for up to 21 percent of murders in the federal prison system, according to the FBI. Of the 469 inmates put to death since Texas resumed executions in 1982, Taylor was only the second white convict executed for killing a black person. The first was in 2003.

The victim’s family stood still as Taylor continued to speak until he was no longer able. Taylor’s mother cried repeatedly: “Oh my God, please don’t.”

The U.S. Supreme Court refused an appeal Thursday that claimed Taylor had poor legal help at his trial and in earlier appeals. The court voted 5-4 to reject the appeal just hours before Taylor was scheduled to die. State attorneys opposed the reprieve, saying Taylor had “brutally killed” people both in and out of prison.

For his final meal, Taylor requested a medium pizza with cheese, beef, black olives and mushrooms. In addition, Taylor ate four soft tacos, large bowls of fried okra and one pint of Blue Bell Ice Cream. Taylor’s final words before he lost consciousness were directed at the victim’s family, “I hope you don’t find satisfaction in this, watching a human being die.”

This was the fifth execution in Texas this year. At least eight more will follow.

"Texas man executed for killing fellow inmate," by Michael Graczyk. (AP Thursday, Jun. 16, 2011)

HUNTSVILLE -- Apologizing for killing a fellow inmate but insisting that he acted in self-defense, Lee Andrew Taylor was executed Thursday evening.

Taylor, 32, used his final statement to tell his mother and wife he loved them. Looking at relatives of Donta Greene, the inmate he fatally stabbed in 1999, Taylor said, "I defended myself when I killed your family member." "Prison is a bad place. There was eight against me. I didn't set out to kill him. I am sorry that I killed him, but he would not have been in prison if he was a saint. I hope y'all understand that." Standing at a death chamber window, Greene's family had no reaction. Taylor said the death penalty is inhuman and unjust and that not everyone on Death Row is a monster. "Everyone changes, right?" he said. "Life is about experience, and people change." Then he told the warden: "I'm ready to teleport."

As the drugs began taking effect, he again looked toward Greene's relatives. "I hope you don't find satisfaction in this, watching a human being die," he said.

He was pronounced dead at 6:24 p.m., the fifth inmate executed in Texas this year. Taylor's mother sobbed: "This is not right."

Taylor was among a few white convicts sent to Death Row in Texas for killing a black person. And of the 469 Texas inmates put to death since executions resumed in 1982, he's only the second to be executed for killing a black person. The first was in 2003.

Taylor's punishment was carried out almost two hours after the U.S. Supreme Court, in a 5-4 vote, rejected a last-day appeal. His lawyer argued that Taylor had poor legal help at his trial and in earlier appeals. It's an issue similar to the one used Wednesday by condemned Texas inmate John Balentine, who won a reprieve from execution.

"Lee Andrew Taylor's childhood was fraught with physical abuse, mental illness, neglect, instability, sexual abuse, substance abuse and exposure to traumatic violence," lawyer David Sergi told the court. "A reasonable investigation would have uncovered details of a childhood vastly different and more severe from the one presented to Taylor's jury."

State attorneys opposed the reprieve request. "He has brutally killed persons both in and out of prison," W. Erich Dryden, an assistant Texas attorney general, told the court. "He has proven beyond any doubt that he is a danger to any society." At the time of Greene's death at the Telford Unit near Texarkana, Taylor was already serving a life sentence for the fatal beating of a 79-year-old man during a robbery in Channelview, just east of Houston. The man's wife was also beaten but survived.

Taylor was 16. He pleaded guilty. "I did something real atrocious when I was a kid," Taylor, a Galveston native, said in a recent interview outside Death Row. "I lost my life and somebody lost their life in turn. "It was a very sad day for two individuals and myself."

He blamed the attack on the couple on a life of "drugs and sex and rock 'n' roll." Taylor's lawyers argued in earlier appeals that prosecutors improperly used that conviction -- when he was under 18 and ineligible for the death penalty -- as evidence to persuade jurors to send him to Death Row for the prison killing. "The state couldn't give me the death penalty when I was 16, so they got back at me," Taylor said.

Jeff Fletcher, one of his trial lawyers, said, "I felt like he was convicted for something he had done prior to the actual crime for which he was given the death penalty." Appeals courts disagreed, ruling that the death sentence was for the prison slaying. Evidence showed that Greene, serving six years for crimes in Dallas County, was stabbed 13 times with an 8-inch metal rod.

James Elliott, who prosecuted Taylor for the prison murder, said the case is an argument against life in prison as a better alternative to the death penalty. "It's pretty naive to expect there will be no murders in prison, especially by those who have committed a murder already," he said this week.

Prison records showed that Taylor belonged to the Aryan Brotherhood, a white prison gang. Taylor said he and David Richbourg, also convicted in the attack on Greene, were the only white inmates on their cellblock. Evidence showed that Richbourg used a sharpened piece of plastic to stab Greene and brandished his weapon to keep others at bay while Taylor made his attack. Richbourg got 48 years for his part in the melee.

Lee Andrew Taylor

Sex: Male

First I want to wish you all wonderful holidays. Everyone that is reading this, I hope that you are all well and in wonderful high spirits!

My name is Lee Andrew Taylor # 999344. I reside on Texas death row. I have been here since 2000. I have had many chances to have my name on a pen pal organization, but I have not been really ready to get involved. When coming here I did not know there was going to be a long process for the courts. I was thinking that I would come here then there would be a short period before the state killed me. The actual time period takes anywhere between 5-10 years now in Texas. Therefore I have become to realize that I DO need friends in here. It is starting to become really lonely. I am hoping that you will find something in this letter that strikes your interest in wanting to reach out and see what type of person I am.

There is no TV in Texas anymore. Therefore there is really nothing to do but sit and write. I have already started writing a book about my life. I am hoping that I will say something about the trials I have been through in this short life, which will help someone going through the same things that I had to go through on the streets. I am 24 years old. My birthday is January 8, 1979. I am from Huston, Texas. I have been on my own since the very young age of 13. I have been there and done that. I was arrested on arm robbery. There was a death involved, but I was only charged with arm robbery. I was sentenced to life in prison. There is a new law in Texas that says if one is in prison serving a life sentence and kills someone then that consists of capitol murder. And therefore given a death sentence. I will not go all off into the case. I am sure there is limited space on the site I am writing this for. I was in a riot there 5 white men, including myself and eight black men. I and my brother were jumped and we fought back until we could not fight anymore. We knew it was coming so we armed ourselves. In prison you don’t run to the “man” (officers) and tell on things like what was about to happen to me and my brother. Not unless you want to go through the rest of your time being a used and reused homosexual. That is reality here. (Sorry) so we fought. A black man was killed. and we were beat half to death by the remaining seven. You know what happens??? The district attorney plays the “race card”. It makes the jury feel sorry about racist people, and if they don’t give me the death sentence then THEY are racist too!

I am young and have a long time in here. I did the only thing I could do. I fought for my life, pride and respect. The three things you have to have here. All this was on video, but the judge would not allow the jury to see me and my friends getting the hell beat out of us. We had many other tapes (not shown) that showed whites being beat on in here. See the reality is that Texas prison population is 70% black. And the few whites that “stay down and fight everyday”. None of that was shown to the jury either. But I will tell you more if you write.

With all that said, I am not racist. I believe in same sex marriage, but other than that I hold not racial hate. I have many black friends in here even after I killed a black in population. You know why? Because they know how it is in here. They also respect who I am. I hope that when you are done reading this that you will want to know me for who I am. Not what I am in here for.

I will write to any of you that wish to correspond. I want to tell you though that the last grade that I finished in school was the 8th grade. Therefore I am not that good at spelling. When I was arrested I could not read or write. I have come along way on my own. I love to read. I try to learn about any subject possible. I have been locked up for 7 years now, since 1995. I came to death row in 2000.

I have dark brown hair, dark brown eyes, and 5” 10” 230lbs, but I am Not fat. My nick name in here is Tiny. (Smile) I could tell you a lot more about me, but like I said, I don’t know how much space I am allowed to use. If you want to write, I will write back

While serving a life sentence for aggravated robbery, Lee Andrew Taylor, a member of the white supremacist Aryan Brotherhood gang, stabbed another inmate to death in a racial fight.

On November 17, 1995, at the age of 16, Taylor robbed and brutally beat an elderly couple in their home in Channelview, Texas, near Houston. John and Mildred Hampton, both 79 years old, were savagely beaten during the robbery. Taylor used the money he got from robbing the couple to rent a motel room and throw a party. John Hampton was in a coma for most of the two months after the beating before finally succumbing to his injuries on January 13, 1996. Mildred had to have massive reconstructive surgeries to repair her broken jaw and other damage to her face. At the February 20, 1996 hearing held to determine whether to certify Taylor as an adult in this crime, John K. Hampton, the grandson of John and Mildred Hampton, testified. He said that he had traveled from Plano with his wife, half-brother and two young children to visit his grandparents in Houston on the day of the crime.

The next morning around 10:00 am they went to the home where his grandparents had lived for 10 years and knocked on the door. After not receiving an answer, he checked the garage to see if the couple's car was there. Mildred frequently left the garage door slightly elevated so their cats could enter and exit. After around ten minutes, Mildred made it to the door and opened it, revealing her battered face to her family. "Her head was about twice the size and her eyes were swollen shut. There was blood on her hands and all over her blouse." John K. Hampton sent his family back to their car and asked a neighbor to call 911, then went inside. His grandfather was lying on his side in a pool of blood and Mildred was in a state of shock, but was lucid enough to warn her grandson not to touch the phone because the attacker had touched it and there might be fingerprints. In any case, the phones were not working because the cords had been ripped from the wall. Jewelry boxes were emptied and John Hampton's wallet containing about $40 was stolen. After police questioned neighbors, they learned that someone named Lee had stayed at a nearby motel and had gone to a hospital after being involved in a fight during his party. Police obtained Taylor's full name at the hospital and matched it to the motel records. After they questioned Taylor, he confessed and showed them where he had thrown away John Hampton's wallet. Taylor was charged with capital murder and was to be tried as an adult. He subsequently accepted a plea bargain and was convicted of aggravated robbery and sentenced to a term of life imprisonment.

While he was serving that sentence, Taylor came into possession of a “shank” — a prison-made stabbing implement — which he used against Donta Green during the morning of March 31, 1999. Taylor stabbed Green 13 times and inflicted numerous other scratch wounds; Green later died as a result. Taylor was indicted for capital murder for intentionally or knowingly causing the death of an individual while serving a sentence of life imprisonment for aggravated robbery.

Following a jury trial, Taylor was convicted and sentenced to death. David Richbourg, a second prisoner who was convicted of the attack on Green received a 48-year sentence. Evidence showed that Richbourg used a sharpened piece of plastic glass to stab Green and then brandished his weapon to keep other inmates at bay while Taylor was making his attack. Medical evidence showed that Taylor's weapon was responsible for the fatal wounds.

Taylor v. Thaler,397 Fed.Appx. 104 (5th Cir. 2010) (Habeas)

Background: Defendant convicted of capital murder for intentionally or knowingly causing the death of an individual while serving a sentence of life imprisonment for aggravated robbery petitioned for a writ of habeas corpus. The United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas, 2009 WL 2833453, denied relief, and defendant appealed.

Holdings: The Court of Appeals held that: (1) using defendant's aggravated robbery conviction, for an offense he committed as a minor, as the predicate for his capital murder conviction was not constitute cruel and unusual punishment; (2) Texas's capital-sentencing scheme rationally narrowed the class of persons eligible for the death penalty; and (3) defendant's claim that his Confrontation Clause rights were violated by the admission of portions of his prison disciplinary record was barred by procedural default. Affirmed

PER CURIAM:

Texas death row inmate Lee Andrew Taylor appeals the district court's denial of habeas relief. For the following reasons, we affirm.

I. BACKGROUND

In 1995, at the age of 16, Taylor robbed an elderly couple in their home in Houston, Texas. He was subsequently convicted of aggravated robbery FN1 and sentenced to a term of life imprisonment. While he was serving that sentence, Taylor came into possession of a “shank”—a prison-made stabbing implement—which he used against Donta Green during the morning of March 31, 1999. Taylor stabbed Green 13 times and inflicted numerous other scratch wounds; Green later died as a result. (FN1. Under Texas law, aggravated robbery includes, inter alia, the commission of robbery if the defendant “causes bodily injury to ... or threatens or places ... in fear of imminent bodily injury or death, ... [a person] 65 years of age or older.” Tex. Penal Code Ann. § 29.03(a)(3)(A).)

Taylor was indicted for capital murder for intentionally or knowingly causing the death of an individual while serving a sentence of life imprisonment for aggravated robbery. See Tex. Penal Code Ann. §§ 19.02(b)(1), 19.03(a)(6)(B).FN2 Following a jury trial, Taylor was convicted and sentenced to death. On December 11, 2002, hearing the case on direct appeal, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (TCCA) affirmed. Taylor next sought post-conviction relief in the state trial court, which denied relief. On March 31, 2004, the TCCA, adopting the trial court's findings of fact and conclusions of law, similarly denied relief.

FN2. Section 19.02(b)(1) provides that a person commits murder by “intentionally or knowingly caus[ing] the death of an individual.” Tex. Penal Code Ann. § 19.02(b)(1). Section 19.03(a)(6)(B) provides that a person commits capital murder by “commit[ting] murder as defined under Section 19.02(b)(1) ... while serving a sentence of life imprisonment ... for an offense under Section ... 29.03.” Tex. Penal Code Ann. § 19.03(a)(6)(B).

Taylor next sought a writ of habeas corpus in federal district court. In his application under 28 U.S.C. § 2254, Taylor raised 14 issues that he claimed warranted relief. The district court dismissed all of Taylor's claims, see Taylor v. Thaler, No. 4:04–CV–150, 2009 WL 2833453 (E.D.Tex. Aug.31, 2009), but issued a certificate of appealability (COA) with respect to three of them. Those three claims raise essentially two issues: (1) whether using Taylor's aggravated robbery conviction—for an offense he committed as a minor—as the predicate for his capital murder conviction constitutes cruel and unusual punishment; and (2) whether admitting Taylor's prison disciplinary record during the sentencing phase of his capital murder trial violated his right to confront the witnesses against him.FN3 Taylor now appeals the denial of habeas relief on those three claims.

FN3. The three claims for which a COA was granted are articulated as follows: 1. Because he is actually innocent of the death penalty, his execution would constitute a miscarriage of justice and is therefore barred by the Eighth Amendment. 10. He was denied the right to confront witnesses by the trial court's admission of prison administrative records which contained testimonial hearsay. 11. Because Taylor was sixteen years old at the time he committed aggravated robbery, his death sentence, which was based in part on his conviction for that robbery, constitutes cruel and unusual punishment.

The district court concluded that Taylor's eleventh claim was “indistinguishable from Taylor's first claim” and denied it for the same reasons that it denied his first claim.

II. LEGAL STANDARDS

In an appeal from a district court's denial of habeas relief, we apply the same standards as the district court. Wooten v. Thaler, 598 F.3d 215, 218 (5th Cir.2010). Taylor's habeas proceeding is subject to the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA). See Pierce v. Thaler, 604 F.3d 197, 200 (5th Cir.2010). Under AEDPA, we may not grant habeas relief: with respect to any claim that was adjudicated on the merits in State court proceedings unless the adjudication of the claim— (1) resulted in a decision that was contrary to, or involved an unreasonable application of, clearly established Federal law, as determined by the Supreme Court of the United States; or (2) resulted in a decision that was based on an unreasonable determination of the facts in light of the evidence presented in the State court proceeding. 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d).

A state court decision is “contrary to” federal precedent if it applies a rule that contradicts the governing law set forth by the Supreme Court or if it involves a set of facts that are materially indistinguishable from a Supreme Court decision but reaches a result different from that Court's precedent. Woodfox v. Cain, 609 F.3d 774, 789 (5th Cir.2010) (citing Woodward v. Epps, 580 F.3d 318, 325 (5th Cir.2009)). “The relevant ‘clearly established federal law’ is the law that existed at the time the state court's denial of habeas relief became final.” Pierce, 604 F.3d at 200 (citing Abdul–Kabir v. Quarterman, 550 U.S. 233, 238, 127 S.Ct. 1654, 167 L.Ed.2d 585 (2007); Williams v. Taylor, 529 U.S. 362, 390–94, 120 S.Ct. 1495, 146 L.Ed.2d 389 (2000)).

III. DISCUSSION

As mentioned above, the district court granted Taylor a COA for each of three claims that he presented in his federal habeas petition. Two of those issues involve the Eighth Amendment's prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment, FN4 while the third involves the Sixth Amendment's Confrontation Clause. FN5 We first address the Eighth Amendment issues before turning to the Sixth Amendment issue. FN4. “Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.” U.S. Const. amend. VIII. FN5. “In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right ... to be confronted with the witnesses against him....” U.S. Const. amend. VI.

A. Cruel and Unusual Punishment

Taylor's Eighth Amendment arguments consist of two discrete theories. First, he claims that the Supreme Court's decision in Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551, 125 S.Ct. 1183, 161 L.Ed.2d 1 (2005), forecloses the use of his prior aggravated robbery conviction as the predicate elevating his homicide offense from non-capital to capital murder because he was a minor when he committed the aggravated robbery offense. Second, he claims that Texas's capital scheme impermissibly expands the class of persons eligible for the death penalty to include persons who commit murder while serving a sentence of life imprisonment for aggravated robbery. The State urges that both claims were procedurally defaulted and are, in any event, meritless. We pretermit discussing the procedural defaults, as Taylor's “claim[s] can be resolved more easily” on the merits. See Busby v. Dretke, 359 F.3d 708, 720 (5th Cir.2004).

1. Youthfulness

In Roper, the Supreme Court held that “[t]he Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments forbid imposition of the death penalty on offenders who were under the age of 18 when their crimes were committed.” 543 U.S. at 578, 125 S.Ct. 1183. Taylor urges that we should interpret Roper to reach the conclusion that his own “diminished moral culpability at 16 years of age, the time at which he committed aggravated robbery, should preclude use of that conviction and sentence as an aggravating factor thereby making him eligible for the death penalty.” FN6

FN6. We note that the TCCA entered a final denial of Taylor's state habeas petition on March 31, 2004, and that Roper was decided nearly a year later, on March 1, 2005. This raises the question whether Roper was “clearly established Federal law, as determined by the Supreme Court of the United States,” at the time of the relevant state court decision, such that Roper can provide Taylor with a foundation for relief under AEDPA. Neither party raised this issue on appeal. In any event, as Taylor's claim fails on its merits, we need not decide that question today.

We conclude that Taylor's claim must fail because Roper does not clearly establish that he is ineligible for the death penalty. The Roper Court held only that “[t]he age of 18 is ... the age at which the line for death eligibility ought to rest.” 543 U.S. at 574, 125 S.Ct. 1183. In reaching this conclusion, the Court identified three ways in which juvenile offenders differed from adult offenders: (1) lack of maturity and underdeveloped senses of responsibility; (2) vulnerability to negative influences and outside pressure; and (3) less developed characters. Id. at 569–70. According to the Court, “[t]hese differences render suspect any conclusion that a juvenile falls among the worst offenders.” Id. at 570. After recognizing “the diminished culpability of juveniles,” id. at 571, the Court then analyzed whether the two recognized social purposes—retribution and deterrence—were furthered by allowing the death penalty for offenders under 18 years of age, id. at 571–72. The Court noted that “[r]etribution is not proportional if the law's most severe penalty is imposed on one whose culpability or blameworthiness is diminished, to a substantial degree, by reason of youth and immaturity.” Id. at 571. It further determined that “the same characteristics that render juveniles less capable than adults suggest as well that juveniles will be less susceptible to deterrence.” Id. The Court concluded that “[w]hen a juvenile offender commits a heinous crime, the State can exact forfeiture of some of the most basic liberties, but the State cannot extinguish his life and his potential to attain a mature understanding of his own humanity.” Id. at 573–74.

While the Roper decision clearly establishes that the death penalty may not be imposed as punishment for an offense committed as a juvenile, it does not clearly establish that such an offense may not be used to elevate murder to capital murder. Here, Taylor is not being punished again for his earlier crime but is instead being punished for a murder that he committed as an adult. See Cannady v. Dretke, 173 Fed.Appx. 321, 329–30 (5th Cir.2006) (per curiam) (likening § 19.03(a)(6) to a constitutionally acceptable recidivist statute). Thus, the TCCA did not unreasonably apply federal law in concluding that Taylor's aggravated robbery conviction and corresponding life sentence rendered him eligible for the death penalty under § 19.03(a)(6)(B).

2. Overbreadth

Taylor also argues that Texas's capital-sentencing scheme fails to genuinely narrow the class of persons eligible for the death penalty. He contends that it is unconstitutional for Texas to authorize the death penalty in cases where a murder is committed by an inmate serving a life sentence for aggravated robbery but not where the same murder is committed by an inmate serving a life sentence for various other crimes. Taylor's argument is, essentially, that because there are other serious crimes that cannot serve as predicates for § 29.03(a)(3), the crime of aggravated robbery may not be so used.

“[T]he Constitution ‘does not mandate adoption of any one penological theory.’ ” Ewing v. California, 538 U.S. 11, 25, 123 S.Ct. 1179, 155 L.Ed.2d 108 (2003) (quoting Harmelin v. Michigan, 501 U.S. 957, 999, 111 S.Ct. 2680, 115 L.Ed.2d 836 (1991) (Kennedy, J., concurring)). Instead, the Supreme Court has emphasized its longstanding “tradition of deferring to state legislatures in making and implementing such important policy decisions.” Id. at 24, 123 S.Ct. 1179 (citing cases). This deference requires that the state have “a reasonable basis for believing” that an enhanced sentence “ ‘advances the goals of its criminal justice system in any substantial way.’ ” Id. at 28, 123 S.Ct. 1179 (alterations omitted) (quoting Solem v. Helm, 463 U.S. 277, 297 n. 22, 103 S.Ct. 3001, 77 L.Ed.2d 637 (1983)). Where the death penalty is involved, the Supreme Court has articulated the following rule: “If a State has determined that death should be an available penalty for certain crimes, then it must administer that penalty in a way that can rationally distinguish between those individuals for whom death is an appropriate sanction and those for whom it is not.” Spaziano v. Florida, 468 U.S. 447, 460, 104 S.Ct. 3154, 82 L.Ed.2d 340 (1984) (citing Zant v. Stephens, 462 U.S. 862, 873–80, 103 S.Ct. 2733, 77 L.Ed.2d 235 (1983); Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238, 294, 92 S.Ct. 2726, 33 L.Ed.2d 346 (1972) (Brennan, J., concurring)); accord Kansas v. Marsh, 548 U.S. 163, 173–74, 126 S.Ct. 2516, 165 L.Ed.2d 429 (2006) (“[A] state capital sentencing system must: (1) rationally narrow the class of death-eligible defendants; and (2) permit a jury to render a reasoned, individualized sentencing determination.... So long as a state system satisfies these requirements, our precedents establish that a State enjoys a range of discretion in imposing the death penalty ....” (internal citation omitted)).

Consistent with these principles, we addressed the constitutionality of Texas's capital-sentencing scheme in Sonnier v. Quarterman, 476 F.3d 349 (5th Cir.2007). We first noted that the distinction between the nine enumerated categories of capital murder, see Tex. Penal Code Ann. § 19.03(a), and other categories of murder, see Tex. Penal Code Ann. § 19.02(b), “is the initial narrowing of the class of persons who may potentially face the death penalty.” Sonnier, 476 F.3d at 366. This, in conjunction with the requirement that one or more statutory aggravating circumstances be found beyond a reasonable doubt by a unanimous jury, led us to “conclude that the Texas scheme ... is constitutionally valid ..., in that it rationally narrows the classes of defendants determined to be eligible and selected for the death penalty.” Id. at 366.

We conclude that our decision in Sonnier, by which we are bound, see United States v. Rose, 587 F.3d 695, 705 (5th Cir.2009) (per curiam), forecloses Taylor's argument. Moreover, it was not irrational for the State to authorize the death penalty only for those inmates whose life sentences were imposed for aggravated offenses. As the TCCA has explained, “inmates who have committed murder or other aggravated offenses have already shown a certain propensity for violence. Furthermore, the greater the sentence that the inmate received, the less he may have to lose by committing further offenses in prison.” Cannady v. State, 11 S.W.3d 205, 215 (Tex.Crim.App.2000) (footnote omitted); see also Cannady v. Dretke, 173 Fed.Appx. at 329 (“[T]he legislators' intent in passing the law was to deter inmates already serving long sentences from murdering other inmates.” (citing State v. Cannady, 913 S.W.2d 741, 743–44 (Tex.App.–Corpus Christi 1996, writ denied))). Nor is it constitutionally problematic that the earlier decision to charge an aggravated offense such as aggravated robbery rather than ordinary robbery rested within the discretion of the prosecutor. See Bordenkircher v. Hayes, 434 U.S. 357, 364, 98 S.Ct. 663, 54 L.Ed.2d 604 (1978) (“Within the limits set by the legislature's constitutionally valid definition of chargeable offenses, ‘the conscious exercise of some selectivity in enforcement is not in itself a federal constitutional violation’ so long as ‘the selection was not deliberately based upon an unjustifiable standard such as race, religion, or other arbitrary classification.’ ” (alteration omitted) (quoting Oyler v. Boles, 368 U.S. 448, 456, 82 S.Ct. 501, 7 L.Ed.2d 446 (1962))). We therefore hold that the state court's decision was neither “contrary to, [n]or involved an unreasonable application of, clearly established Federal law, as determined by the Supreme Court of the United States.” 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d)(1).

B. Confrontation Clause

Taylor next alleges that admission of portions of his prison disciplinary record during the sentencing phase of his trial violated his right to be confronted with the witnesses against him. During the sentencing phase of his trial, the State sought to introduce a copy of Taylor's prison disciplinary record, which contained reports of altercations with other inmates and threats made to prison guards. Taylor objected on the grounds that the reports contained inadmissible hearsay and violated his rights under the Confrontation Clause. The state trial court admitted the prison disciplinary record under the business records exception to the hearsay rule. See Tex.R. Evid. 803(6). On direct appeal to the TCCA, Taylor claimed that the record was erroneously admitted under the business records exception because it contained “matters observed by police officers and other law enforcement personnel.” Tex.R. Evid. 803(8)(B); see also Cole v. State, 839 S.W.2d 798, 810 (Tex.Crim.App.1990) (holding that evidence made inadmissible by Rule 803(8) may not be admitted under Rule 803(6)). However, because Taylor did not raise that objection at trial, the TCCA held that he “procedurally defaulted his Cole claim for appeal.” The TCCA further held that Taylor's Confrontation Clause claim, which was predicated on the Cole claim, was thus procedurally defaulted as well. FN7. The TCCA held in the alternative that any error was harmless.

In this appeal, Taylor has not attempted to argue that his procedural default on the Confrontation Clause claim is excused by cause and prejudice. Instead, he merely reurges his assertion that because he is actually innocent of the death penalty, any procedural default should be excused.FN8 We have already rejected, on the merits, Taylor's contentions that he is ineligible for the death penalty. As a result, his claim of actual innocence based on those contentions must also fail. Because Taylor offers no independent justification for us to reach the merits of his Confrontation Clause claim, we do not do so.

FN8. In the portion of his brief devoted to the issue, Taylor argues: As already stated, Petitioner contends that any procedural default should be excused in light of his “actual innocence” of the death sentence imposed on him as a result of the unconstitutional application of Tex. Pen.Code § 19.03(a)(6)(B) in which an offense committed when Petitioner was a juvenile was used to elevate the killing of a fellow inmate from simple murder to capital murder.

IV. CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment of the district court is AFFIRMED.