Executed March 15, 2012 06:11 p.m. CDT by Lethal Injection in Oklahoma

9th murderer executed in U.S. in 2012

1286th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

2nd murderer executed in Oklahoma in 2012

98th murderer executed in Oklahoma since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(9) |

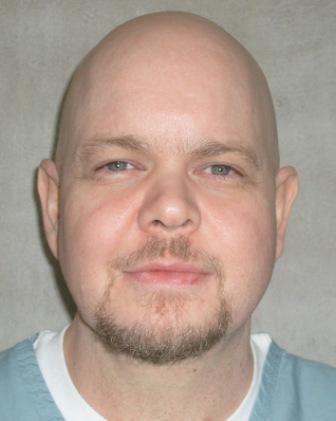

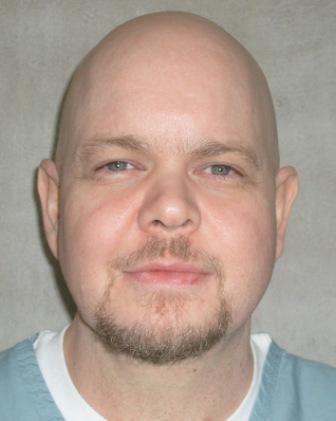

Timothy Shaun Stemple W / M / 34 - 46 |

Trisha Jane Ruddick Stemple W / F / 30 |

Run Over With Truck |

Citations:

Stemple v. State, 994 P.2d 61 (Okla.Crim. App. 2000). (Direct Appeal)

Stemple v. Workman, 418 Fed.Appx. 732 (10th Cir. 2011). (Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

A large stuffed-crust pizza with extra cheese, half pepperoni and half Canadian bacon, and a 2-liter bottle of orange soda with ice.

Final Words:

None.

Internet Sources:

Oklahoma Department of Corrections

Inmate: TIMOTHY S STEMPLE

ODOC# 261686

Birth Date: 04/09/1965

Race: White

Sex: Male

Height: 5 ft. 08 in.

Weight: 180 pounds

Hair: Blond

Eyes: Blue

County of Conviction: TULSA

Case#: 96-5169

Date of Conviction: 02-13-98

Convictions: Murder In The First Degree (Death); Attempted Murder In The First Degree (22 years); Conspiracy To Commit Murder In The First Degree (10 years).

Location: Oklahoma State Penitentiary, Mcalester

"Oklahoma executes man for wife's 1996 slaying," by Katie Fretland. (March 15, 2012)

McALESTER, Okla. (AP) — An Oklahoma man convicted of killing his wife with help from a relative of his mistress to collect insurance money was put to death by injection Thursday. Timothy Shaun Stemple shook his head no when asked if he had any last words, as members of his family and his wife's sat separately from each other watching the condemned man through glass. The 46-year-old Stemple gasped for about 20 seconds, his eyes opened and he groaned. He then laid still with closed eyes and his face turned pale. He was pronounced dead at 6:11 p.m.

His family had asked the governor to stay the execution so that medical testimony disputing his accomplice's account of the 1996 attack on Trisha Stemple could be heard in court. Stemple's mother, his 21-year-old daughter and his sisters held each other by their hands and arms as he was being put to death. One of his sisters held his crying daughter's face close to hers.

Afterward, Trisha Stemple's sister, Deborah Ruddick-Bird, said the day was not about Timothy Stemple. She said it was "about justice, finality and closure for my gorgeous sister, Trisha, and my family." "Today we put a period at the end of the chapter that held us captive for far too long," Ruddick-Bird told reporters. "Today we breathe again. Today we move forward and move on."

Trisha Stemple, 30, was beaten with a plastic-covered baseball bat and run over by a pickup truck Oct. 24, 1996, along a Tulsa highway. Her husband maintained his innocence throughout the trial and appeals process. And at a clemency hearing last month, he declined to address Pardon and Parole Board members. The board denied his plea for clemency.

"The state of Oklahoma murdered an innocent man today," his mother, Lia Stemple, told The Associated Press by phone after the execution. "I don't want vengeance but I want the truth to be known so this doesn't happen to another family. My son was a noble man."

The New York-based Innocence Project also urged Gov. Mary Fallin to stay the execution and called for additional DNA testing to be done. Human blood was found on the plastic that was on the bat, but it was too deteriorated to determine whose it was, prosecutors said. His family hoped advances in DNA testing could help exonerate him.

Stemple's execution at the state prison in McAlester is the first of three scheduled over the next two months in Oklahoma. Last month, Department of Corrections officials said the state has four doses left of the lethal injection drug pentobarbital, an anesthetic that manufacturers have objected to selling for use in executions. It was among the drugs used to execute Stemple.

Stemple's accomplice, Terry Hunt, told the AP during a prison interview Sunday that he was disappointed Stemple didn't confess when given the opportunity at the clemency hearing. "I'm not innocent and Shaun is not innocent," said Hunt, who's in prison in Hominy serving a life sentence. Hunt is the cousin of Dani Wood, who was having an affair with Timothy Stemple. Hunt's testimony that the crime was brutal, with Trisha Stemple being conscious during much of the attack, was a factor that helped prosecutors secure the death penalty for Stemple.

Hunt struck the woman with a bat twice and her husband hit her in the back of the head about 20 to 30 times, according to Hunt's testimony. Hunt said Stemple tried to drive over his wife's head with the pickup truck. Hunt tried to place a wheel on her chest. Following the initial attack, she managed to drag herself onto grass along the highway after they drove away. In his testimony, Hunt said they returned and struck her with the truck, traveling about 60 mph.

A forensic expert consulted by Timothy Stemple's family said the wife's injuries were consistent with being hit by a vehicle and run over but that there's no evidence she was beaten. The medical examiner first thought she died after being hit by a car, but there was "no primary point of impact below the knees as is usual in the typical auto-pedestrian collision," according to prosecutors' report in the case.

"Tulsa County killer Shaun Stemple executed for wife's 1996 murder ," by Cary Aspinwall. (3/16/2012)

McALESTER - The state executed Timothy Shaun Stemple on Thursday evening for the 1996 murder of his wife, Trisha Stemple, of Jenks. He was pronounced dead at 6:11 p.m. at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary. He took a few short gasps and briefly opened his eyes after the lethal injection began at 6:05 p.m. He had declined to give any last words.

His daughter, Lauren Stemple, who was not quite 6 when her mother was killed 15 years ago, witnessed the execution along with her father's parents and two sisters. She sobbed quietly on her aunt's shoulder as her father took his final breaths. A last-minute campaign this week by Shaun Stemple's family and anti-death penalty groups failed to convince Gov. Mary Fallin to grant Stemple, now 46, a stay of execution.

In 1997, a jury convicted Stemple of brutally beating to death his wife of 11 years and running over her with a pickup, aided by a teenage accomplice. Investigators said he planned his wife's killing to collect on a $950,000 insurance policy.

Several of Trisha Stemple's family members also witnessed the execution, along with retired Tulsa Police Department Homicide Detective Mike Huff and Tulsa County Sheriff Stanley Glanz. Trisha Stemple's youngest sister, Deborah Ruddick-Bird, offered a statement on behalf of her family after the execution: "Today is not about Shaun. It's about justice, finality and closure for my gorgeous sister Trisha and my family." On Thursday, Ruddick-Bird said, her family "put a period at the end of a chapter that held us captive for far too long."

Stemple's final meal request was a large stuffed-crust pizza with extra cheese, half pepperoni and half Canadian bacon, and a 2-liter bottle of orange soda with ice. He was the second Oklahoma inmate to be executed this year.

Stemple and his family contended that he was innocent and that Trisha Stemple, 30, died as a result of an automobile-pedestrian collision. They mounted a campaign based on their belief that he was wrongly convicted, using analysis from forensic firms they hired to bolster their case. The Innocence Project and the Norwegian foreign minister lobbied for Fallin to stay Stemple's execution.

According to court testimony, Shaun Stemple hired a teenage accomplice, Terry Hunt, to wait in the woods alongside U.S. 75 between 81st and 91st streets, and Stemple, who had feigned pickup trouble at a preselected spot nearby, returned to the spot in a car with his wife. Stemple and Hunt then took turns beating her with a cellophane-wrapped baseball bat, and he ran over her body with a pickup, Hunt testified at Stemple's trial.

Hunt said Trisha Stemple tried to get up after her husband tried to drive the truck's tires over her head, and then Stemple got out of the truck, walked over to her and said: "Don't worry, Trish. The ambulance is on its way." Stemple then grabbed the bat again and hit her in the back of the head eight to 12 more times, Hunt testified. Trisha Stemple's skull, neck bone and pelvis were crushed and 17 ribs were broken. A hole was drilled into one of Trisha Stemple's car tires to make it appear that she'd had car trouble, according to testimony. Her body was found alongside the highway after Shaun Stemple reported her missing.

Her death was originally investigated as a hit-and-run auto-pedestrian collision, but investigators began to suspect foul play as they examined the evidence. Hunt, the cousin of Shaun Stemple's then-girlfriend, is serving a life sentence for first-degree murder.

Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt issued a statement Thursday before Stemple's execution, reiterating that a jury of Stemple's peers examined the evidence and sentenced him to death 14 years ago. "My thoughts are with Trisha Stemple's family and what they have endured," Pruitt said.

"Oklahoma executes man who killed wife for insurance," by Steve Olafson. (Mar 15, 2012 9:38pm EDT)

(Reuters) - An Oklahoma man was executed on Thursday by lethal injection for murdering his wife, who prosecutors say was beaten with a baseball bat and repeatedly run over with a pickup truck, to collect nearly $1 million in insurance benefits. Timothy Shaun Stemple died at 6:11 p.m. local time, prison spokesman Jerry Massie said. Stemple, 47, requested pizza and an orange soda for his last meal but did not offer a final statement, Massie said.

Stemple killed his wife Tricia in 1996. His plan to cash in on her death unraveled quickly at his trial the following year, when the 16-year-old nephew of his girlfriend testified he was promised a share of the insurance benefits to help in the killing. The teenager was spared a possible death penalty in exchange for testifying for the prosecution and is serving a life prison term.

Tricia Stemple's body was found by the side of a highway in Tulsa County the day after her husband reported her missing. She died from blunt force head trauma and had fractures to her arm, ribs, pelvis, vertebrae and skull. The 30-year-old woman's car was parked near her body with its hood raised to make it appear she had been attacked after her vehicle was disabled by a flat tire, but trial evidence revealed the tire had been deliberately punctured with a drill.

Stemple is the second man executed in Oklahoma this year and the 98th person since capital punishment was resumed in 1977, the Oklahoma Department of Corrections said. He is the ninth prisoner executed in the United States in 2012, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Two more execution dates have been set in Oklahoma in April and May.

In October 1996, Trisha Stemple’s body was found near Highway 75 in Tulsa County, Oklahoma. Her death was briefly investigated as a hit-and-run accident, but as the investigation progressed, the Tulsa Police Department began to suspect that Timothy Shaun Stemple had orchestrated the death of his wife.

Stemple was ultimately charged in her death with First Degree Malice Aforethought Murder, Conspiracy to Commit First Degree Murder, and Attempted First Degree Murder. At trial, the prosecution put forth evidence that Stemple concocted a plan to murder his wife, mother of his two children, then ages 11 and 6, and collect the proceeds of her life insurance policy, worth almost $1,000,000.

Stemple was having an extra-marital affair with Dani Wood. Dani Wood had a sixteen year old cousin, Terry Lee Hunt. According to Hunt, Stemple offered him $25,000 to $50,000 to help kill Trisha (if they collected the insurance money). Hunt recruited another person, Nathanial Helm to assist in the plan. Helm and Hunt went to Wal-Mart where they purchased a baseball bat and plastic wrap. The plastic wrap was wrapped around the bat to keep the bat from getting bloody. On October 10, 1996, Hunt and Helm went to the designated location on highway 75 and waited for Stemple and his wife to arrive. A while later Stemple drove up and told Helm and Hunt that Trisha was ill and he could not get her to accompany him.

Two weeks later, Stemple arranged for Hunt to drive Stemple's pickup to a particular location on highway 75 and leave the hood up. Stemple and Trisha arrived in their black Nissan Maxima. Stemple began working on the truck and Trisha stood next to the truck. Hunt came up behind Trisha and hit her in the head with the bat. The blow did not render Trisha unconscious, so Stemple took the bat and hit her several more times. Stemple and Hunt then placed Trisha's head in front of the front tire of the pickup and attempted to run over her head, however, the tire would not roll over Trisha's head so her head was pushed along the pavement. After this, Trisha tried to get up. Stemple grabbed the bat and hit her several more times. The pair then placed Trisha's body under the truck and drove over her chest.

After this Trisha rose up on her elbows, so Stemple hit her again several times with the bat. Stemple then went back to the black Nissan and drilled a hole in the front tire to make it look as if Trisha's car had a flat. One expert testified that the hole in the tire had spiral striations consistent with drilling. Stemple and Hunt left in the pickup, but decided to turn around to make sure Trisha was dead. When they got back to the spot where they left Trisha, they noticed that she had crawled into the grass beside the road. Stemple then sped up and ran over Trisha as she lay in the grass. Trisha's body was found later that morning, after Stemple called reporting that she was missing.

The autopsy evaluation revealed that Trisha had fractures to her arm, ribs, pelvis, vertebrae and skull. The medical examiner concluded that Trisha died from blunt force trauma to the head. While in the Tulsa County jail awaiting trial, Stemple made numerous notes including confessions, lists of witnesses, etc. Inmates testified that Stemple tried to get them to arrange the death of several witnesses. The inmates also testified that Stemple gave them a copy of his confession. Included in these writings were sample letters for witnesses Terry Hunt and Dani Wood, detailing their involvement and exculpating him from the crime. Hunt and Wood were to be coerced into rewriting and signing the letters by persons hired by the other inmates.

Stemple claimed that he was at home when Trisha left during the middle of the night. Stemple testified that he believed that Wood was responsible for the murder of Trisha. Additionally, the prosecutor introduced a five-minute long videotape of an interview Tulsa police officers conducted with Stemple prior to his arrest, during which Stemple stated that he knew “how ugly this looks for me,” summarized the evidence which he believed the police would use against him, and eventually invoked his right to counsel.

Ultimately, the jury convicted Stemple on all three counts. During the separate penalty-phase proceeding, the jury found the existence of two aggravating circumstances: (1) Stemple committed the murder for remuneration or the promise of remuneration; and (2) the murder was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel. The jury therefore recommended that Stemple be sentenced to death on the murder conviction. The trial court sentenced him in accordance with the jury’s recommendations. Hunt pled guilty to first-degree murder and was sentenced to life in prison with the possibility of parole.

"Wife-killer is executed," by Rachel Petersen. (March 15, 2012)

McALESTER — Oklahoma death row inmate and convicted wife-killer Timothy Shaun Stemple, 46, was executed by lethal injection Thursday evening in the death chamber at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary. When the execution procedure began at 6:04 p.m., and the blinds covering the window between the execution chamber and the viewing area were raised, OSP Warden Randy Workman asked Stemple if he had a last statement. Stemple, with his eyes closed, simply nodded his head from left to right, indicating he would have no last words. At 6:05 p.m. Workman said, “Let the execution begin.”

Stemple’s time of death was announced by an attending physician at 6:11 p.m. His execution was witnessed by seven members of the media; members from the Oklahoma Attorney General’s Office; Tulsa Police Chief Chuck Jordan; Sheriff Glands from Tulsa; OSP and Oklahoma Department of Corrections staff; Stemple’s mother and father, his two sisters and his daughter; and 12 members of the victim’s family. Other victim’s family members were present, however, they watched the execution via live video feed outside of the execution chamber.

Stemple was denied clemency in February by a 4-1 vote by the Oklahoma State Pardon and Parole Board. The Associated Press reported that his accomplice, Terry Hunt, said he was disappointed that Stemple didn’t confess when given the opportunity at his clemency hearing.

Stemple received his death sentence for the Oct. 24, 1996, murder of his 30-year-old wife Trisha J. Stemple.

Trisha Stemple’s sister, Deborah Ruddick-Bird, made a statement to the media following the execution. “Today is not about Shaun,” she said. “Today is about justice, finality and closure for my beautiful sister Trisha. ... Today we say it is finished.”

A written statement was provided by Michael Steen on behalf of Trisha Stemple’s father, Morris Ruddick, who was unable to attend the execution as he is out of the country on a missionary assignment. “The media often speaks of closure during tragic events such as those witnessed today,” the statement reads. “I think it more appropriate to say we think of this as a foreclosure. The State has collected his body and his mind as compensation for his transgressions. Before the judgment seat of Christ, the Lord will determine the eternal outcome for his soul.”

According to court records from the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals, Stemple “concocted a plan to terminate the life of his wife, Trisha Stemple, and to collect her life insurance proceeds. Stemple was having an extra-marital affair with Dani Wood. Hunt, Stemple’s accomplice, was Dani Wood’s sixteen year old cousin. According to Hunt, Stemple offered him $25,000 to $50,000 to help kill Trisha (if they collected the insurance money).” “(Timothy) Stemple arranged for Hunt to drive Stemple’s pickup to a particular location on highway 75 and leave the hood up,” court documents state. “Stemple and Trisha arrived in their black Nissan Maxima. Stemple began working on the truck and Trisha stood next to the truck. Hunt came up behind Trisha and hit her in the head with the bat. The blow did not render Trisha unconscious, so Stemple took the bat and hit her several more times.

“Stemple and Hunt then placed Trisha’s head in front of the front tire of the pickup and attempted to run over her head, however, the tire would not roll over Trisha’s head so her head was pushed along the pavement. After this, Trisha tried to get up. Stemple grabbed the bat and hit her several more times. The pair then placed Trisha’s body under the truck and drove over her chest. After this Trisha rose up on her elbows, so Stemple hit her again several times with the bat. “Stemple then went back to the black Nissan and drilled a hole in the front tire to make it look as if Trisha’s car had a flat. One expert testified that the hole in the tire had spiral striations consistent with drilling. Stemple and Hunt left in the pickup, but decided to turn around to make sure Trisha was dead. When they got back to the spot where they left Trisha, they noticed that she had crawled into the grass beside the road. Stemple then sped up and ran over Trisha as she lay in the grass.

“Trisha’s body was found later that morning, after Stemple called reporting that she was missing ... Stemple claimed that he was at home when Trisha left during the middle of the night. Stemple testified that he believed that Wood was responsible for the murder of Trisha.” The court document continues by stating that the “type of injuries sustained and the description of the attack show that Trisha Stemple suffered great physical pain before she died.”

Stemple’s co-defendant Terry L. Hunt, now 31 years old, testified for the prosecution during Timothy Stemple’s hearing and is currently in custody at the R.B. Dick Conner Correctional Center in Hominy. He is serving a life sentence, according to the Oklahoma Department of Corrections website at www.doc.state.ok.us.

Stemple continued to maintain his innocence of this crime and claimed he was at home when his wife was killed. Stemple has been housed on death row inside OSP’s H-unit since Feb. 23, 1998.

The last death row inmate to be executed at OSP was Gary R. Welch, 49, who received his death sentence for the 1994 slaying of 35-year-old Robert Dean Hardcastle and was executed on Jan. 5, 2012. Welch’s execution was the first in the United States in the year 2012. Oklahoma death row inmate Garry Thomas Allen was scheduled to be executed on Feb. 16 until Gov. Mary Fallin granted a 30-day stay so her legal team could have more time to consider a 2005 recommendation by the Oklahoma State Pardon and Parole Board to commute his sentence to life. On Tuesday, Fallin denied granting Allen clemency and he is now scheduled to be executed April 12 at OSP. Allen received his death sentence for the 1986 murder of his wife, Lawanna Gail Titsworth. Allen was convicted of gunning down Titsworth just days after she moved out of their home with their two sons, who were ages 6 and 2 at the time.

Oklahoma Attorney General (News Release)

02/24/2012

Timothy Shaun Stemple Clemency Denied

OKLAHOMA CITY – The Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board today voted 4-1 to deny clemency for Tulsa County death row inmate Timothy Shaun Stemple, Attorney General Scott Pruitt said. Stemple, 46, is scheduled to be executed March 15, for the murder of his wife, Trisha J. Stemple, on Oct. 24, 1996. The U.S. Supreme Court denied Stemple’s final appeal on Jan. 9.

According to the autopsy report, Trisha Stemple died from blunt force trauma to the head. She had fractures to her arm, ribs, pelvis, vertebrae and skull. The evidence showed the victim was hit multiple times with a baseball bat and repeatedly run over with Stemple’s pickup. The victim was left along a Tulsa County highway and her car was disabled to make it appear as though she had experienced car trouble. Trisha Stemple’s body was found later that day after Timothy Stemple reported his wife missing.

Timothy Stemple devised a plan to kill his wife and collect $950,000 from a life insurance policy. He recruited an accomplice – his girlfriend's 16-year-old cousin Terry Hunt – and offered him a portion of the insurance money once the victim was killed and the money received. Hunt testified for the prosecution and is serving a life sentence. Stemple was sentenced to death in 1997.

01/20/2012

Stemple Execution Date Set for March

OKLAHOMA CITY – The Court of Criminal Appeals today set March 15, 2012, as the execution date for Tulsa County death row inmate Timothy Shaun Stemple, 46.

Stemple was convicted and sentenced to death for the murder of his wife, Trisha J. Stemple, 30, on Oct. 24, 1996, along a highway. Evidence showed the victim had been hit multiple times with a baseball bat and repeatedly run over with Stemple’s pickup. The victim died from blunt force trauma to the head and also had fractures to her arm, ribs, pelvis, vertebrae and skull. Attorney General Scott Pruitt requested the execution date on Jan. 9, after the United States Supreme Court denied the inmate’s final appeal.

01/09/2012

Execution Date Requested for Timothy Shaun Stemple

OKLAHOMA CITY – Attorney General Scott Pruitt today filed a request for the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals to set an execution date for Tulsa County death row inmate Timothy Shaun Stemple, 46. The U.S. Supreme Court denied the inmate’s final appeal on January 9, 2012.

Stemple was convicted and sentenced to death for the first degree murder of his wife, Trisha J. Stemple, 30, on Oct. 24, 1996. According to the autopsy report, the victim died from blunt force trauma to the head. She had fractures to her arm, ribs, pelvis, vertebrae and skull. The evidence showed the victim was hit multiple times with a baseball bat and repeatedly run over with Stemple’s pickup. Pruitt asked the court to set the date “sixty days after January 9, 2012, or the earliest date the court deems fit.”

“Timothy Shaun Stemple has exhausted all of his appeals in a court of law,” Pruitt said. “After an in-depth review of this case, my office has found it is appropriate to proceed with requesting an execution date, and that the execution of Timothy Shaun Stemple should be carried out.”

###

Wikipedia: Oklahoma Executions

A total of 98 individuals convicted of murder have been executed by the State of Oklahoma since 1976, all by lethal injection:

1 Charles Troy Coleman 10 September 1990 John Seward

2 Robyn Leroy Parks 10 March 1992 Abdullah Ibrahim

3 Olan Randle Robinson 13 March 1992 Shiela Lovejoy, Robert Swinford

4 Thomas J. Grasso 20 March 1995 Hilda Johnson

5 Roger Dale Stafford 1 July 1995 Melvin Lorenz, Linda Lorenz, Richard Lorenz, Isaac Freeman, Louis Zacarias, Terri Horst, David Salsman, Anthony Tew, David Lindsey

6 Robert Allen Brecheen [1][2][3] 11 August 1995 Marie Stubbs

7 Benjamin Brewer 26 April 1996 Karen Joyce Stapleton

8 Steven Keith Hatch 9 August 1996 Richard Douglas, Marilyn Douglas

9 Scott Dawn Carpenter 7 May 1997 A.J. Kelley

10 Michael Edward Long 20 February 1998 Sheryl Graber, Andrew Graber

11 Stephen Edward Wood 5 August 1998 Robert B. Brigden

12 Tuan Anh Nguyen 10 December 1998 Amanda White, Joseph White

13 John Wayne Duvall 17 December 1998 Karla Duvall

14 John Walter Castro 7 January 1999 Beulah Grace, Sissons Cox, Rhonda Pappan

15 Sean Richard Sellers 4 February 1999 Paul Bellofatto, Vonda Bellofatto, Robert Bower

16 Scotty Lee Moore 3 June 1999 Alex Fernandez

17 Norman Lee Newsted 8 July 1999 Larry Buckley

18 Cornel Cooks 2 December 1999 Jennie Elva Ridling

19 Bobby Lynn Ross 9 December 1999 Steven Mahan

20 Malcolm Rent Johnson 6 January 2000 Ura Alma Thompson

21 Gary Alan Walker 13 January 2000 Eddie O. Cash, Valerie Shaw-Hartzell, Jane Hilburn, Janet Jewell, Margaret Bell Lydick, DeRonda Gay Roy

22 Michael Donald Roberts 10 February 2000 Lula Mae Brooks

23 Kelly Lamont Rogers 23 March 2000 Karen Marie Lauffenburger

24 Ronald Keith Boyd 27 April 2000 Richard Oldham Riggs

25 Charles Adrian Foster 25 May 2000 Claude Wiley

26 James Glenn Rodebeaux 1 June 2000 Nancy Rose Lee McKinney

27 Roger James Berget 8 June 2000 Rick Lee Patterson

28 William Clifford Bryson 15 June 2000 James Earl Plantz

29 Gregg Francis Braun 10 August 2000 Gwendolyn Sue Miller, Barbara Kchendorfer, Mary Rains, Pete Spurrier, Geraldine Valdez

30 George Kent Wallace 10 August 2000 William Von Eric Domer, Mark Anthony McLaughlin

31 Eddie Leroy Trice 9 January 2001 Ernestine Jones

32 Wanda Jean Allen 11 January 2001 Gloria Jean Leathers

33 Floyd Allen Medlock 16 January 2001 Katherine Ann Busch

34 Dion Athansius Smallwood 18 January 2001 Lois Frederick

35 Mark Andrew Fowler 23 January 2001 John Barrier, Rick Cast, Chumpon Chaowasin

36 Billy Ray Fox 25 January 2001

37 Loyd Winford Lafevers 30 January 2001 Addie Mae Hawley

38 Dorsie Leslie Jones, Jr. 1 February 2001 Stanley Eugene Buck, Sr.

39 Robert William Clayton 1 March 2001 Rhonda Kay Timmons

40 Ronald Dunaway Fluke 27 March 2001 Ginger Lou Fluke, Kathryn Lee Fluke, Suzanna Michelle Fluke

41 Marilyn Kay Plantz 1 May 2001 James Earl Plantz

42 Terrance Anthony James 22 May 2001 Mark Allen Berry

43 Vincent Allen Johnson 29 May 2001 Shirley Mooneyham

44 Jerald Wayne Harjo 17 July 2001 Ruther Porter

45 Jack Dale Walker 28 August 2001 Shely Deann Ellison, Donald Gary Epperson

46 Alvie James Hale, Jr. 18 October 2001 William Jeffery Perry

47 Lois Nadean Smith 4 December 2001 Cindy Baillee

48 Sahib Lateef Al-Mosawi 6 December 2001 Inaam Al-Nashi, Mohamed Al-Nashi

49 David Wayne Woodruff 21 January 2002 Roger Joel Sarfaty, Lloyd Thompson

50 John Joseph Romano 29 January 2002

51 Randall Eugene Cannon 23 July 2002 Addie Mae Hawley

52 Earl Alexander Frederick, Sr. 30 July 2002 Bradford Lee Beck

53 Jerry Lynn McCracken[10] 10 December 2002 Tyrrell Lee Boyd, Steve Allen Smith, Timothy Edward Sheets, Carol Ann McDaniels

54 Jay Wesley Neill 12 December 2002 Kay Bruno, Jerri Bowles, Joyce Mullenix, Ralph Zeller

55 Ernest Marvin Carter, Jr. 17 December 2002 Eugene Mankowski

56 Daniel Juan Revilla 16 January 2003 Mark Gomez Brad Henry

57 Bobby Joe Fields 13 February 2003 Louise J. Schem

58 Walanzo Deon Robinson 18 March 2003 Dennis Eugene Hill

59 John Michael Hooker 25 March 2003 Sylvia Stokes, Durcilla Morgan

60 Scott Allen Hain 3 April 2003 Michael William Houghton, Laura Lee Sanders

61 Don Wilson Hawkins, Jr. 8 April 2003 Linda Ann Thompson

62 Larry Kenneth Jackson 17 April 2003 Wendy Cade

63 Robert Wesley Knighton 27 May 2003 Richard Denney, Virginia Denney

64 Kenneth Chad Charm 5 June 2003 Brandy Crystian Hill

65 Lewis Eugene Gilbert II 1 July 2003 Roxanne Lynn Ruddell

66 Robert Don Duckett 8 July 2003 John E. Howard

67 Bryan Anthony Toles 22 July 2003 Juan Franceschi, Lonnie Franceschi

68 Jackie Lee Willingham 24 July 2003 Jayne Ellen Van Wey

69 Harold Loyd McElmurry III 29 July 2003 Rosa Vivien Pendley, Robert Pendley

70 Tyrone Peter Darks 13 January 2004 Sherry Goodlow

71 Norman Richard Cleary 17 February 2004 Wanda Neafus

72 David Jay Brown 9 March 2004 Eldon Lee McGuire

73 Hung Thanh Le 23 March 2004 Hai Hong Nguyen

74 Robert Leroy Bryan 8 June 2004 Mildred Inabell Bryan

75 Windel Ray Workman 26 August 2004 Amanda Hollman

76 Jimmie Ray Slaughter 15 March 2005 Melody Sue Wuertz, Jessica Rae Wuertz

77 George James Miller, Jr. 12 May 2005 Gary Kent Dodd

78 Michael Lannier Pennington 19 July 2005 Bradley Thomas Grooms

79 Kenneth Eugene Turrentine 11 August 2005 Avon Stevenson, Anita Richardson, Tina Pennington, Martise Richardson

80 Richard Alford Thornburg, Jr. 18 April 2006 Jim Poteet, Terry Shepard, Kevin Smith

81 John Albert Boltz 1 June 2006 Doug Kirby

82 Eric Allen Patton 29 August 2006 Charlene Kauer

83 James Patrick Malicoat 31 August 2006 Tessa Leadford

84 Corey Duane Hamilton 9 January 2007 Joseph Gooch, Theodore Kindley, Senaida Lara, Steven Williams

85 Jimmy Dale Bland 26 June 2007 Doyle Windle Rains

86 Frank Duane Welch 21 August 2007 Jo Talley Cooper, Debra Anne Stevens

87 Terry Lyn Short[4] 17 June 2008 Ken Yamamoto

88 Jessie Cummings 25 September 2008 Melissa Moody

89 Darwin Brown 22 January 2009 Richard Yost

90 Donald Gilson 14 May 2009 Shane Coffman

91 Michael DeLozier 9 July 2009 Orville Lewis Bullard, Paul Steven Morgan

92 Julius Ricardo Young 14 January 2010 Joyland Morgan, Kewan Morgan

93 Donald Ray Wackerly II 14 October 2010 Pan Sayakhoummane

94 John David Duty 16 December 2010 Curtis Wise

95 Billy Don Alverson 6 January 2011 Richard Kevin Yost

96 Jeffrey David Matthews 11 January 2011 Otis Earl Short Mary Fallin

97 Gary Welch 5 January 2012 Robert Dean Hardcastle

98 Timothy Shaun Stemple 15 March 2012 Trisha Stemple

Stemple v. State, 994 P.2d 61 (Okla.Crim. App. 2000). (Direct Appeal)

Defendant was convicted in the District Court of Tulsa County, B.R. Beasley, J., of first degree malice murder, attempted murder, and conspiracy to commit murder, and was sentenced to death for murder, 22 years' imprisonment for attempted murder, and 10 years' imprisonment for conspiracy. Defendant appealed. The Court of Criminal Appeals, Lile, J., held that: (1) defendant was not denied his right to be present at every critical stage of proceeding; (2) additions of detail to testimony between preliminary hearing and trial were not subject to state's continuing duty to disclose; (3) admission of videotape of defendant's statements to police did not rise to level of plain error; (4) admonishments to jury were sufficient to cure prosecutorial errors; (5) evidence did not establish overt act toward commission of murder required to support conviction for attempted murder; (6) defendant did not receive ineffective assistance of counsel; (7) evidence supported findings of aggravating circumstances of murder for remuneration and especially heinous, atrocious or cruel murder; (8) jury properly weighed aggravating circumstances and mitigating evidence; and (9) cumulative error did not deprive defendant of fair trial.

Affirmed in part; reversed and remanded in part. Strubhar, J., concurred in part and concurred in result in part. Chapel, J., concurred in part and dissented in part.

LILE, Judge:

¶ 1 Timothy Shaun Stemple was convicted by jury of first degree malic murder, 21 O.S.1991, § 701.7 (count one), conspiracy to commit first degree murder, 21 O.S.1991, § 421 (count two), and attempted first degree murder, 21 O.S.1991, § 42 (count three), in Tulsa County District Court, Case Number CF–96–5169, the Honorable B.R. Beasley, Associate District Judge, presiding. After the sentencing stage, the jury found the existence of two aggravating circumstances: “the person committed the murder for remuneration or the promise of remuneration, or the person employed another to commit the murder for remuneration or promise of remuneration;” and “the murder was especially heinous, atrocious or cruel.” 21 O.S.1991, § 701.12(3) & (4). The jury set punishment at death on count one, ten years on count two and twenty-two years on count three.

FACTS

¶ 2 Stemple concocted a plan to terminate the life of his wife, Trisha Stemple, and to collect her life insurance proceeds. Stemple was having an extra-marital affair with Dani Wood. Dani Wood had a sixteen year old cousin, Terry Hunt. According to Hunt, Stemple offered him $25,000 to $50,000 to help kill Trisha (if they collected the insurance money).

¶ 3 Hunt recruited another person, Nathanial Helm to assist in the plan. Helm and Hunt went to Wal–Mart where they purchased a baseball bat and plastic wrap. The plastic wrap was wrapped around the bat to keep the bat from getting bloody.

¶ 4 On October 10, 1996, Hunt and Helm went to the designated location on highway 75 and waited for Stemple and his wife to arrive. A while later Stemple drove up and told Helm and Hunt that Trisha was ill and he could not get her to accompany him.

¶ 5 Two weeks later, Stemple arranged for Hunt to drive Stemple's pickup to a particular location on highway 75 and leave the hood up. Stemple and Trisha arrived in their black Nissan Maxima. Stemple began working on the truck and Trisha stood next to the truck. Hunt came up behind Trisha and hit her in the head with the bat. The blow did not render Trisha unconscious, so Stemple took the bat and hit her several more times.

¶ 6 Stemple and Hunt then placed Trisha's head in front of the front tire of the pickup and attempted to run over her head, however, the tire would not roll over Trisha's head so her head was pushed along the pavement. After this, Trisha tried to get up. Stemple grabbed the bat and hit her several more times. The pair then placed Trisha's body under the truck and drove over her chest. After this Trisha rose up on her elbows, so Stemple hit her again several times with the bat.

¶ 7 Stemple then went back to the black Nissan and drilled a hole in the front tire to make it look as if Trisha's car had a flat. One expert testified that the hole in the tire had spiral striations consistent with drilling. Stemple and Hunt left in the pickup, but decided to turn around to make sure Trisha was dead. When they got back to the spot where they left Trisha, they noticed that she had crawled into the grass beside the road. Stemple then sped up and ran over Trisha as she lay in the grass.

¶ 8 Trisha's body was found later that morning, after Stemple called reporting that she was missing. The autopsy evaluation revealed that Trisha had fractures to her arm, ribs, pelvis, vertebrae and skull. The medical examiner concluded that Trisha died from blunt force trauma to the head.

¶ 9 While in the Tulsa County jail awaiting trial, Stemple made numerous notes including confessions, lists of witnesses, etc. Inmates testified that Stemple tried to get them to arrange the death of several witnesses. The inmates also testified that Stemple gave them a copy of his confession. Included in these writings were sample letters for witnesses Terry Hunt and Dani Wood, detailing their involvement and exculpating him from the crime. Hunt and Wood were to be coerced into rewriting and signing the letters by persons hired by the other inmates.

¶ 10 Stemple claimed that he was at home when Trisha left during the middle of the night. Stemple testified that he believed that Wood was responsible for the murder of Trisha.

JURY SELECTION ISSUES

¶ 11 Stemple complains, in proposition four, that he was deprived of his right to be present at every critical stage of the proceeding by being absent from an in camera hearing regarding comments made by a spectator to venire member Heffernan. Heffernan indicated, during voir dire, that a spectator had stated an opinion about the case to him. Heffernan indicated that the statement did not taint him in any way. Heffernan was not removed by either side, nor by the court.

¶ 12 The next day an in camera hearing was held. The spectator, Marita Ries said that she was sitting next to Heffernan and possibly said that “this is a terrible case.” Ries was admonished to keep her opinions to herself. Stemple was not present at this hearing and his attorney advised the trial court that he waived his client's right to be present.

¶ 13 First, we note that this in camera hearing was not part of the voir dire and Ries was not a part of the jury pool. Therefore, cases which discuss the absence of a defendant from voir dire are distinguishable. See Darks v. State, 1998 OK CR 15, ¶ 35, 954 P.2d 152, 162 (“There is no way to assess the extent of prejudice, if any, a defendant might suffer by not being able to advise his attorney during jury selection.”)

¶ 14 Stemple was present during the voir dire of Heffernan and he was aware that a spectator had stated an opinion to Heffernan. Ries' admission during the in camera hearing did not add anything to the voir dire. In actuality, her statement did not indicate any bias whatsoever. Regardless, of the guilt or innocence of Stemple, all present could agree that this was a terrible case.

¶ 15 We find that the absence of Stemple during this in camera hearing was not prejudicial to his case. It certainly was not an instance where a fair and just trial was thwarted by his absence. Kentucky v. Stincer, 482 U.S. 730, 745, 107 S.Ct. 2658, 2667, 96 L.Ed.2d 631 (1987); Gregg v. State, 1992 OK CR 82, 844 P.2d 867, 876. Therefore, there was no error here.

FIRST STAGE ISSUES

¶ 16 Stemple argues in proposition two that the State failed to comply with basic rules of discovery when prosecutors failed to inform him that Terry Hunt had changed his story. The Oklahoma Discovery Code requires that the State disclose, upon request of the defense, “the names ... of witnesses which the state intends to call at trial, together with their relevant, written or recorded statement, if any, or if none, significant summaries of any oral statement ...;” 22 O.S.Supp.1998, § 2002(A)(1)(a), and “any written or recorded statements and the substance of any oral statements made by ... a codefendant.” 22 O.S.Supp.1998, § 2002(A)(1)(c). The Discovery Code also requires that the State provide exculpatory evidence, regardless of a request by the defense. 22 O.S.Supp.1998, § 2002(A)(2). The State is under a continuing duty to disclose discoverable material. 22 O.S.Supp.1998,§ 2002(C). Stemple filed a motion for discovery; therefore, he triggered the requirements of Sections 2002(A) and 2002(C).

¶ 17 The State disclosed recorded statements made by Hunt, and Hunt testified at preliminary hearing. Hunt's preliminary hearing testimony was not interrupted or cut short by the magistrate. In fact, trial counsel admitted that he thoroughly cross-examined Hunt at preliminary hearing. Stemple argues that Hunt materially changed his testimony at trial, and because of the change, the State had a duty to inform him about changes of which the State had knowledge prior to trial.

¶ 18 At trial, Hunt testified that Stemple's first plan involved a kill switch on the Nissan Maxima. Stemple and his wife would drive to a location where Stemple would kill the car. Stemple and his wife would get out and Hunt would come out of hiding and hit Trisha with the baseball bat. Stemple objected to this testimony, stating that this is the first time he had heard these details. The prosecutor admitted that, before testifying, Hunt indicated that this conversation had taken place. The trial court sustained Stemple's objection and the jury was admonished to disregard the testimony. Regarding this testimony, we find that any perceived error was cured by the admonishment to the jury. Patton v. State, 1998 OK CR 66, ¶ 68, 973 P.2d 270, 292–93, cert. denied, 528 U.S. 939, 120 S.Ct. 347, 145 L.Ed.2d 271 (a trial court's admonishment usually cures any error).

¶ 19 Later, Hunt testified that he drove by Nathaniel Helm's residence before driving out to the location of the murder. Again, Stemple objected stating that this was the first time he had heard this story. Obviously, the State knew about this information because they talked about it in opening statement. The State argued that this testimony was a minor deviation from the discovery materials and preliminary hearing testimony. Stemple also objected to Hunt's testimony wherein he said that he acted like the assault was a “car jacking” and told them to “get down.” The trial court overruled the objections.

¶ 20 Hunt's own desire or need to make it sound like he was a “car jacker” did nothing to change the substance of his testimony against Stemple. There is no evidence that the State knew that Hunt was going to testify that he was acting like it was a car jacking. Hunt obviously was trying to make Trisha believe that her husband was not involved in the attack.

¶ 21 Obviously, the State did not turn over the substance of all of the oral statements made by Hunt leading up to trial. The State defended themselves by saying that Hunt was made available to the defense for questioning. On appeal, the State argues that the change in testimony did not amount to a materially significant change and that Stemple was not prejudiced by the more detailed testimony at trial.

¶ 22 We find that the failure to disclose this information was not fatal to this case. First, the additional information did not substantially change the evidence against Stemple. Whether or not Hunt went by Helm's residence before going to the scene of the crime is inconsequential. Therefore, the trial court did not abuse its discretion in allowing the evidence to be introduced.

¶ 23 Hunt's testimony regarding the desire to make the assault look like a “car jacking” was not a substantial change in his earlier testimony. At preliminary hearing Hunt stated that the plan was, first, to make it look like a robbery, and later, Stemple decided to make it look like a hit and run.

¶ 24 Stemple also complains about Hunt's testimony when he states that he tried to run over her chest. The discovery materials apparently stated that “they tried to run over her.” The trial court decided that this was substantially the same. Stemple lastly complains about testimony concerning the disposal of the keys of the Maxima. During preliminary hearing, Hunt did not mention any of these details. These were not changes in testimony sufficient to trigger the State's continuing duty to disclose (if the State had prior knowledge of the change). This was inconsequential testimony and did not constitute the substance of the case.

¶ 25 In this case there was no complete failure to disclose evidence as there was in Skelly v. State, 1994 OK CR 55, 880 P.2d 401. In the present case, the prosecutor did turn over all written and recorded statements. But the State did not disclose the substance of Hunt's oral statements made just before testifying. Stemple cites the Florida case of Evans v. State, 721 So.2d 1208 (Fla.App.1998) for support of this proposition. However in Evans the witness's testimony changed from “I didn't see anything” to “I saw the defendant shoot the victim.” Such a material change in testimony did not occur in this case.

¶ 26 The Supreme Court of Florida has stated that, “When testimonial discrepancies appear, the witness' trial and deposition testimony can be laid side-by-side for the jury to consider. This would serve to discredit the witness and should be favorable to the defense. Therefore, unlike failure to name a witness, changed testimony does not rise to the level of a discovery violation....” Bush v. State, 461 So.2d 936, 938 (Fla.1984), cert. denied, 475 U.S. 1031, 106 S.Ct. 1237, 89 L.Ed.2d 345 (1986). The same can be said of the case at bar. Stemple had the opportunity and did question Hunt regarding the discrepancies in his trial testimony versus his preliminary hearing testimony and his recorded statements. These discrepancies served to discredit Hunt and made him somewhat less believable.

¶ 27 The State is not required to give a script of its case in chief. However, the State is under a continuing duty to disclose additional evidence or material discovered prior to or during trial. 22 O.S.Supp.1998,§ 2002(C). Such failure to disclose may be error when this evidence is material, would change the theory of the case or would cause the defendant to change his strategy. However, in this case, the State did not violate the letter or the spirit of the Discovery Code by failing to inform Stemple of the discrepancies in Hunt's testimony.

¶ 28 Also in this proposition, Stemple argues that the State attempted to introduce testimony from James Johnson that was not provided in discovery. Stemple objected to the testimony at trial. His objections were sustained and the evidence was excluded. The State provided a written statement by Johnson. That is all that is required in the Oklahoma Discovery Code. The State is required to disclose a witness's “relevant, written or recorded statements, if any, or if none, significant summaries of any oral statement,....” 22 O.S.Supp.1998, § 2002(A)(1)(a). There was no violation of the discovery code here.

¶ 29 Stemple, lastly complains about the testimony of William Compion regarding insurance scams. He claims he was not advised that Compion would testify about these alleged scams. Stemple's objection to William Compion's testimony was sustained. Stemple did not ask that the jury be admonished. Therefore, reversal is not required. Shepard v. State, 1988 OK CR 97, ¶ 7, 756 P.2d 597, 600 (where objection was sustained and no request was made to have the jury admonished and no motion for a mistrial or other relief was made, reversal was not required).

¶ 30 In proposition three, Stemple complains that the introduction of a videotape, State's exhibit number 87, showing that he exercised his right to remain silent and his right to consult an attorney violated his due process rights. Trial counsel never filed a written motion to exclude the tape or to excise any portion of the tape. At trial the trial court asked defense counsel, “Do you want an exception?,” and counsel replied in the affirmative. The trial court later stated that “State's exhibit 87 was admitted and an exception has been allowed the defendant.”

¶ 31 “Failure to object with specificity to errors alleged to have occurred at trial, thus giving the trial court an opportunity to cure the error during the course of trial, waives that error for appellate review unless the error constitutes fundamental error, i.e. plain error....” Simpson v. State, 1994 OK CR 40, ¶ 2, 876 P.2d 690, 693; See 12 O.S.1991, § 2104(A)(1)(“Error may not be predicated upon a ruling which admits or excludes evidence unless a substantial right of a party is affected, and...a timely objection or motion to strike appears of record, stating the specific ground of objection, if the specific ground was not apparent from the context....”); See also Dunham v. State, 1988 OK CR 211, 10–11, 762 P.2d 969, 972 (error not preserved by general objection).

¶ 32 In Wolfe v. State, 1987 OK CR 80, ¶ 4, 736 P.2d 546, 547, this Court held that trial counsel's general objection “for purposes of appeal” were insufficient to preserve error in the introduction of tape recorded statements. On appeal the appellant claimed that “the statement was made during plea negotiations with the prosecutor, and was coerced by law enforcement officials.” This Court reasoned that “12 O.S.1981, § 2104(A)(1) requires that objections to the admission of evidence must be both specific and timely, in order for merits of the objection to be considered on appeal.” Id. In Mornes v. State, 1988 OK CR 78, ¶ 12, 755 P.2d 91, 95, this Court held that a general objection is insufficient when portions of evidence are admissible. In Mornes, the appellant made a general objection to the introduction of a pen pack. He failed to request that the trial court excise improper portions of the pen pack.

¶ 33 The case at bar is similar to both Wolfe and Mornes. Portions of this tape were admissible, but the introduction of some portion of the tape could be construed as error. Stemple's general objection to this tape was not sufficient because portions of the tape were admissible and it is not clear upon what grounds Stemple based his objection. Because trial counsel did not make a more specific objection and because he did not request the redaction of objectionable material, we will review for plain error only.

¶ 34 On the video tape Stemple begins by saying, “I feel as though I should have an attorney ... because how ugly this looks on me.” Stemple says that he fears that the police are going to try and pin the murder on him because he had plenty of motive; the large insurance policy and the extramarital affair. He also explains that he knows that a red pickup was seen in the area of the crime and he recently owned a red pickup. He knows people saw him out there because he was out there in the area that night. Stemple states that he wants to help but he does not want to “screw” himself. He says that he will be selective in the questions that he answers.

¶ 35 The officers assured Stemple that they were not going to arrest him, but they read the MirandaFN1 warning to him anyway. They asked him if he wanted to answer questions or if he wanted an attorney and Stemple said, “I better get an attorney.” He says again that he wants to help and asks if he can make an appointment for a later time. The detectives tell him that will be up to him and his attorney. They tell him “you know what happened.” And Stemple replies, “I do.” Then Stemple says “I'm gonna get an attorney.” At that time the interview ended. All of this was on the video shown to the jury. FN1. Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 86 S.Ct. 1602, 16 L.Ed.2d 694 (1966)

¶ 36 Stemple claims in this appeal that he requested counsel at the beginning of the tape, therefore, this video taped statements was admitted in violation of his right to counsel. In Davis v. United States, 512 U.S. 452, 459, 114 S.Ct. 2350, 2355, 129 L.Ed.2d 362 (1994), the Court held that if a suspect makes a request for counsel that is ambiguous or equivocal in that a reasonable officer in light of the circumstances would have understood only that the suspect might be invoking his right to counsel, Supreme Court precedents do not require that questioning cease. The Court stated that if it were to require questioning to cease if a suspect makes a statement that might be a request for an attorney, the clarity and ease of application necessary for effective law enforcement would be lost. Id. at 461, 114 S.Ct. at 2356. The portion of the tape, before Stemple was read the Miranda warning, was admissible. Stemple did not unequivocally invoke his rights. Therefore, questioning did not need to cease.

¶ 37 Stemple was still not clear that he wanted an attorney when he commented about counsel right after the reading of Miranda. He continued to say I want to talk, “can I make an appointment for later.” Even if this was an unequivocal request for counsel, the conversation introduced after this did not rise to the level of plain error. “Plain error denies the accused a constitutional or statutory right, and goes to the foundation of the case.” McGregor v. State, 1994 OK CR 71, ¶ 34, 885 P.2d 1366, 1383, cert. denied, 516 U.S. 827, 116 S.Ct. 95, 133 L.Ed.2d 50 (1995).

¶ 38 Stemple's statement indicating that he knew what happened was incriminating. An argument can be made that the comment was made after an unequivocal request for counsel in response to a comment by police that they should know was reasonably likely to elicit an incriminating response. See Rhode Island v. Innis, 446 U.S. 291, 299–300, 100 S.Ct. 1682, 1688–89, 64 L.Ed.2d 297 (1980). Stemple explained on the tape why he was reluctant to talk to officers. He was looking out for his best interests and the interests of his children and he didn't want to get himself into trouble. Even though there may have been a violation of Stemple's Fifth Amendment right, the introduction of the comment did not go to the foundation of the case.

¶ 39 Stemple complains that the prosecutor used his silence and request for counsel during this interview against him. In Jenkins v. Anderson, 447 U.S. 231, 239–40, 100 S.Ct. 2124, 2129–30, 65 L.Ed.2d 86 (1980), the Supreme Court held that once a defendant is informed that he has a right to remain silent, any attempt to impeach the defendant by his subsequent silence and invocation of the right to counsel is error. The Court reasoned that once a person is given the Miranda warnings, he is informed, “at least implicitly, that his subsequent decision to remain silent cannot be used against him.” Jenkins, 447 U.S. at 240, 100 S.Ct. at 2130. Further, due process requires that the prosecution not be allowed to call attention a defendant's silence and insist that, because he chose not to talk, when he has been told that he has a right to remain silent, an unfavorable inference might be drawn regarding the credibility of his trial testimony. Id.

¶ 40 The Fifth Amendment right to counsel is a prophylactic right designed to protect a person from the compelling pressures of custodial interrogation. McNeil v. Wisconsin, 501 U.S. 171, 176, 111 S.Ct. 2204, 2208, 115 L.Ed.2d 158 (1991); Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 86 S.Ct. 1602, 16 L.Ed.2d 694 (1966). The purpose of the Fifth Amendment right to counsel is to protect “the suspect's ‘desire to deal with the police only through counsel,’ ” McNeil, 501 U.S. at 178, 111 S.Ct. at 2209, quoting, Edwards v. Arizona, 451 U.S. 477, 484, 101 S.Ct. 1880, 1884, 68 L.Ed.2d 378 (1981).

¶ 41 In White v. State, 1995 OK CR 15, ¶ 22, 900 P.2d 982, 992, this Court stated, Any comment on a defendant's exercise of his right to remain silent is error. However, error may be harmless where there is overwhelming evidence of guilt and the defendant is not prejudiced by the error. Error may also be “cured” where the trial court sustains the defendant's objection and admonishes the jury.[footnotes omitted].

¶ 42 The prosecutor in this case insisted on using Stemple's desire to remain silent as a means of convincing the jury that he was guilty. The prosecutor first questioned Stemple's failure to call the police. However, there was no objection to this questioning. Therefore, we will review for plain error only. Stemple also complains about the prosecutor's mentioning of the videotape during closing. The prosecutor's comments said nothing about Stemple's right to remain silent. He merely commented on the portion of the tape which was admissible.

¶ 43 This Court held in Dungan v. State, 1982 OK CR 152, ¶ 6, 651 P.2d 1064, 1065, that comments on a defendant's exercise of his right to remain silent after he has received his Miranda warnings may be prejudicial to the extent that they constitute fundamental error. However, whether these comments rise to the level of fundamental error depends on the particular facts and circumstances of each case. Based on the fact that Stemple admitted to the murder in notes he wrote in jail and the overwhelming evidence establishing guilt, we find that the questioning and comments by the prosecutor did not rise to the level of plain error.

¶ 44 In propositions six and seven, Stemple complains about other comments made by the prosecutor. At one point, the prosecutor asked Stemple if he left Oregon because he was “run out of town because you were abusive with children.” The defendant's objection was sustained and the jury was admonished to disregard the comment. In viewing the entire record in this case, we believe that the admonishment to the jury was sufficient to cure the error committed by the prosecutor. Patton, 1998 OK CR 66, ¶ 68, 973 P.2d at 292–93.

¶ 45 Stemple also complains that the prosecutor improperly vouched for the testimony of Terry Hunt and Rahmon Macon. At no time did defense counsel object to the comments of which Stemple now complains. Therefore, Stemple has waived review for all but plain error. We find that none of the comments rise to the level of plain error.

¶ 46 Stemple claims that the prosecutor cast aspersions on defense counsel. No objections were made to these comments; thus, we can review for plain error only. There was no plain error here. Next, Stemple complains that the prosecutor accused Stemple of fabricating a defense and lying. Of the comments made, defense counsel only objected to one of them. This objection was sustained and the jury was admonished to disregard the comment. The admonishment cured the error. The other comments did not rise to the level of plain error.

¶ 47 Stemple complains about the prosecutor's demonstration with the baseball bat during closing argument. The record does not reflect how the prosecutor was handling the bat during closing argument. Stemple tries to equate the prosecutor's action to the stabbing of a picture of the victim. See Brewer v. State, 1982 OK CR 128, ¶ 5, 650 P.2d 54, 57, cert. denied, 459 U.S. 1150, 103 S.Ct. 794, 74 L.Ed.2d 999 (1983). However the record does not support such analogy. We find no error here.

¶ 48 Stemple complains about cross examination regarding the failure to call witnesses. Stemple's objection at trial was sustained and the jury was admonished. The trial court's actions cured any error. Stemple complains about the prosecutor asking Stemple if the other witnesses are lying. Of the seven incidents cited by Stemple, only one question drew an objection. This type of cross examination did not amount to error. Asking the defendant whether other witnesses were lying was a method used to impeach the defendant's testimony. Ross v. State, 1978 OK CR 136, ¶ 7, 588 P.2d 1269, 1270 (“While this technique is not desirable, we find no error in his cross-examination.”).

¶ 49 Stemple complains about the prosecutor's improper cross examination of witness Tyler Ferrell regarding pending charges. An objection was sustained and the jury was admonished to disregard. The admonition cured any error.

¶ 50 In propositions ten and eleven, Stemple argues that the introduction of certain evidence was error. Stemple first argues that the evidence of his past insurance claims was inadmissible. The evidence was relevant to show motive and knowledge. First, the insurance claims were relevant to show that Stemple was familiar with the insurance claim process, whether or not the claims were valid. Second, the insurance claims, which may have been dubious, were relevant to corroborate the testimony of jail inmates, who testified that Stemple told them about past insurance scams.

¶ 51 Stemple makes the claim that the papers he prepared while in the county jail were prepared for his attorney in preparation for trial. Stemple cites no authority for this proposition. In fact the witnesses called during the Jackson v. DennoFN2 hearing stated that Stemple willingly shared this information with them. Therefore, he waived any alleged privilege. We find that the trial court did not abuse its discretion in allowing the introduction of this evidence during trial. Dunham v. State, 1988 OK CR 211, ¶ 10, 762 P.2d at 972. FN2. 378 U.S. 368, 84 S.Ct. 1774, 12 L.Ed.2d 908 (1964).

¶ 52 In proposition eight, Stemple claims that there was insufficient evidence to support the attempted murder charge. We agree. The State alleged that the attempted murder took place on October 10, 1996, the night Trisha was too ill to accompany Stemple to the planned murder site.

¶ 53 In order to be guilty of an attempted crime three elements must be met: “the intent to commit the crime; the performance of some act toward its commission (commonly called the commission of some overt act); and the failure to complete or consummate the crime. It is equally settled that the overt act must be more than mere preparation or planning the crime....” “It must be such act or acts as will apparently result, in the usual and natural course of events, if not hindered by extraneous causes, in the commission of the crime itself.” Rosteck v. State, 1988 OK CR 11, 749 P.2d 556, 559, quoting, Dunbar v. State, 75 Okl.Cr. 275, 131 P.2d 116, 122 (1942); See 21 O.S.1991, § 44 (definition of attempt).

¶ 54 What we have in this case is mere preparation for the commission of the offense. Hunt and Helm were stationed at the planned location in preparation to attack; however, there was no overt act toward the commission of murder. Therefore, Stemple's conviction for attempted murder must be reversed and remanded with instructions to dismiss.

¶ 55 In a related claim, proposition nine, Stemple claims that the convictions for attempted murder and conspiracy to commit murder violate the principles of double jeopardy. Because we have decided that the attempted murder conviction must be dismissed, this proposition is moot.

¶ 56 In proposition five, Stemple raises claims of ineffective assistance of counsel occurring during the first stage of trial. In order to show ineffective assistance of counsel, Appellant must meet the two-pronged test set out in Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 104 S.Ct. 2052, 80 L.Ed.2d 674 (1984). Lewis v. State, 1998 OK CR 24, ¶ 48, 970 P.2d 1158, 1173, cert. denied, 528 U.S. 892, 120 S.Ct. 218, 145 L.Ed.2d 183. First Appellant must show that trial counsel's performance was deficient (trial counsel was not functioning as the counsel guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment). Second, he must show he was prejudiced by the deficient performance (counsel's errors deprived him of a fair trial with a reliable outcome). Strickland, 466 U.S. at 687, 104 S.Ct. at 2064.

¶ 57 We are to accord a strong presumption that counsel was at least constitutionally competent. Strickland, 466 U.S. at 689, 104 S.Ct. at 2065.We will judge counsel's challenged conduct on the facts of the particular case, viewed as of the time of counsel's conduct, and ask if the conduct was professionally unreasonable. Hooper v. State, 1997 OK CR 64, ¶ 57, 947 P.2d 1090, 1111, cert. denied, 524 U.S. 943, 118 S.Ct. 2353, 141 L.Ed.2d 722 (1998).

¶ 58 An error must be so egregious that it indicates deficient performance by counsel, falling outside the wide range of reasonable professional assistance. Strickland, 466 U.S. at 687–89, 104 S.Ct. at 2064–65. Many significant errors will not meet this highly demanding standard. Kimmelman v. Morrison, 477 U.S. 365, 381–82, 106 S.Ct. 2574, 2586, 91 L.Ed.2d 305 (1986). Those errors that require reversal do so because they reflect performance by counsel that has “so undermined the proper functioning of the adversarial process that the trial cannot be relied on as having produced a just result.” Strickland, 466 U.S. at 686, 104 S.Ct. at 2064.

¶ 59 Stemple claims that his trial counsel was ineffective for failing to object to the cross-examination of Stemple and the closing argument by the prosecutor regarding Stemple's assertion of his right to counsel. We believe that the failure to object to the cross-examination did not deprive Stemple of a fair trial. The failure to object to the closing argument did not rise to the level of deficient performance, as the comments were properly based on admissible evidence.

¶ 60 Stemple claims that counsel was ineffective for waiting to give opening statement at the start of his case in chief. This choice is a legitimate strategy. Counsel cannot be faulted for waiting to make an opening statement at the start of his case in chief. This strategic choice does not rise to the level of deficient performance. Hammon v. State, 1995 OK CR 33, ¶ 107, 898 P.2d 1287, 1310.

¶ 61 Stemple also claims that counsel was ineffective for failing to present expert testimony regarding the inconsistencies between the crime scene and Hunt's testimony. Stemple does not show what the inconsistencies were, how they are relevant to his trial or what the expert testimony would have been. Therefore, we cannot review this claim.

SECOND STAGE ISSUES

¶ 62 Stemple complains that improper remarks by the prosecutor during the sentencing stage violated his due process rights and denied him a fair sentencing proceeding. All of the comments Stemple now complains about were met with contemporaneous objections and the jury was admonished to disregard the comments. We find that the admonitions by the trial court were sufficient to cure any conceivable error. Patton, 1998 OK CR 66, ¶ 68, 973 P.2d at 292–93.

¶ 63 Stemple alleges, in proposition thirteen, that the evidence was insufficient to support the jury's verdict regarding the aggravating circumstances. Stemple also argues that the mitigating evidence outweighed the aggravating circumstances.

¶ 64 The jury found the existence of two aggravating circumstances: “the person committed the murder for remuneration or the promise of remuneration, or the person employed another to commit the murder for remuneration or promise of remuneration,” 21 O.S.1991, § 701.12(3); and “the murder was especially heinous, atrocious or cruel.” 21 O.S.1991, § 701.12(4). On appeal, the standard of review is “whether there was any competent evidence to support the State's charge that the aggravating circumstance existed.” Bryson v. State, 1994 OK CR 32, ¶ 52, 876 P.2d 240, 259, cert. denied, 513 U.S. 1090, 115 S.Ct. 752, 130 L.Ed.2d 651 (1995).

¶ 65 Stemple claims that the only evidence of a murder for remuneration or employing another to commit the murder for remuneration is the uncorroborated testimony of Hunt. However, Hunt's testimony was corroborated. Stemple's own written words corroborated Hunt's testimony. Further, circumstantial evidence can be adequate to corroborate the accomplice's testimony. Pierce v. State, 1982 OK CR 149, ¶ 6, 651 P.2d 707, 709. The existence of a large insurance policy, the fact that Hunt admitted his involvement, and the fact that the murder was set up to look like an accident all corroborate Hunt's testimony that the murder was done for remuneration.

¶ 66 The other aggravating circumstance, the murder was especially heinous, atrocious or cruel, is also supported by the evidence. This aggravating circumstance must be supported by evidence of conscious serious physical abuse or torture prior to death. This may include the infliction of either great physical anguish or extreme mental cruelty. Cheney v. State, 1995 OK CR 72, ¶ 15, 909 P.2d 74, 80.

¶ 67 The evidence showed that Trisha Stemple was struck by a baseball bat and run over by a pickup. She tried to get up, so she was struck again with the baseball bat. Later, she crawled from the road, onto the grass, where she was struck by the pickup. The fact that Trisha Stemple was conscious during the attack is shown by her ability to move herself from the pavement on to the grass on the side of the road after being beaten by a baseball bat and run over by the pickup. The type of injuries sustained and the description of the attack show that Trisha Stemple suffered great physical pain before she died. This evidence is sufficient.

¶ 68 The mitigating evidence included testimony from Stemple's son who asked that his father's life be spared. The mitigating factors were outlined in an instruction to the jury. As well as Stemple's relationship with his children and extended family, the mitigating factors included his lack of a prior criminal history; his high probability of rehabilitation; his religious beliefs; his past history of working with and coaching children in soccer; his education, young age and a listing of positive things he has done in his life.

¶ 69 We believe that the jury properly weighed all of the mitigating evidence against the aggravating circumstances. We will not disturb the jury's findings that the aggravating circumstances outweighed the mitigating factors.

HARMLESS ERROR AND CUMULATIVE ERROR REVIEW

¶ 70 Stemple argues in his initial proposition of error that the errors in this case were too egregious to be called harmless. Stemple claims that his credibility was on the line in this case. He claims that the errors occurring at trial damaged his credibility in such a way as to deprive him of a fair trial.

¶ 71 This proposition rests on the premises that the key witnesses against him were all yoked with the presumption of not being credible. The jurors were instructed that the codefendant's testimony and the “jail house snitches' testimony” were all to be judged more critically.

¶ 72 Stemple claims that he should not have been yoked with this presumption. He claims that the errors that occurred at trial improperly created this yoke for him to bear. A yoke that should not have been placed upon him in front of the jury. He claims that this yoke created, in the jury's mind, an improper and unconstitutional burden on his credibility which affected the outcome of the case. Therefore, Stemple claims, the errors cannot be called harmless.

¶ 73 The United States Supreme Court has held that only errors which create a situation where “a criminal trial cannot reliably serve its function as a vehicle for determination of guilt or innocence ....” can escape harmless error review. Rose v. Clark, 478 U.S. 570, 577–78, 106 S.Ct. 3101, 3106, 92 L.Ed.2d 460 (1986). Even Constitutional errors are subject to the Harmless Error doctrine. Id. at 576, 106 S.Ct. at 3105. The United States Supreme Court has repeatedly stated, “the Constitution entitles a criminal defendant to a fair trial, not a perfect one.” Id. at 579, 106 S.Ct. at 3105; See Lutwak v. United States, 344 U.S. 604, 620, 73 S.Ct. 481, 490, 97 L.Ed. 593 (1953). “[I]f the defendant had counsel and was tried by an impartial adjudicator, there is a strong presumption that any other errors that may have occurred are subject to harmless-error analysis.” Rose v. Clark, 478 U.S. at 579, 106 S.Ct. at 3106.

¶ 74 Stemple does not claim that the errors in this case are not subject to harmless-error analysis. He merely claims that the errors, placed in the context of this case, support the notion that the errors were not harmless and justify a reversal of his conviction and sentence.

¶ 75 We disagree with this notion. The trial in this case was not perfect, however, viewing the errors in the context of this case, the errors did not deprive Stemple of a fair trial. Many of the errors of which Stemple complains in his brief, were not properly preserved at trial. We found that these errors did not rise to the level of plain error beca se the error did not go to the foundation of the case.

¶ 76 Of the errors properly preserved at trial, we found numerous errors which were cured by the trial court by admonition to the jury. We find that these errors, viewed cumulatively, do not warrant reversal. We found numerous allegations that did not rise to the level of plain error. Even looking at these allegations in a cumulative fashion, we find that they do not rise to the level of plain error. Finally, our analysis of all of the errors combined do not rise to the level of reversible error in this case.

MANDATORY SENTENCE REVIEW

¶ 77 Title 21 O.S.1991, § 701.13, requires this Court to determine “[w]hether the sentence of death was imposed under the influence of passion, prejudice or any other arbitrary factor; and whether the evidence supports the jury's or judge's finding of statutory aggravating circumstance.” Sufficient evidence existed to support the finding of the two statutory aggravating circumstances, as discussed in proposition thirteen. After reviewing the entire record in this case, we find that the sentence of death was not imposed because of any arbitrary factor, passion or prejudice. The facts of this case simply warranted the penalty of death.

¶ 78 We have found that Stemple's conviction for attempted murder must be reversed and remanded with instructions to dismiss. We find no error warranting reversal of the convictions or sentences for the remaining counts; therefore, the Judgment and Sentence on the remaining counts is AFFIRMED.

STRUBHAR, P.J., concurs (Count III), concurs in result (Counts I & II). LUMPKIN, V.P.J., and JOHNSON, J., concur. CHAPEL, J., concurs in part/dissents in part.

Stemple v. Workman, 418 Fed.Appx. 732 (10th Cir. 2011). (Habeas)

Background: Following affirmance on direct appeal of petitioner's state court convictions for first-degree murder and other offenses and death sentence, 994 P.2d 61, he filed petition for writ of habeas corpus. The United States District Court for the Northern District of Oklahoma, Gregory K. Prizzel, J., 2009 WL 1561566, denied the petition. Petitioner appealed.

Holdings: The Court of Appeals, Deanell Reece Tacha, Senior Circuit Judge, held that: (1) petitioner was not “in custody,” for Miranda purposes, at time of his unwarned videotaped interview with police, and (2) petitioner's Fourteenth Amendment claim was procedurally barred. Affirmed.

ORDER AND JUDGMENT

FN* This order and judgment is not binding precedent except under the doctrines of law of the case, res judicata and collateral estoppel. It may be cited, however, for its persuasive value consistent with Fed. R.App. P. 32.1 and 10th Cir. R. 32.1.

DEANELL REECE TACHA, Senior Circuit Judge.

Timothy Shaun Stemple was sentenced to death upon his conviction for the murder of his wife. After his conviction and sentence were affirmed on appeal, Mr. Stemple petitioned for a writ of habeas corpus pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2254. The district court denied his petition but granted a certificate of appealability on two issues involving the admission of evidence at trial. We take jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1291 and § 2253(c) and AFFIRM.

I. BACKGROUND

The following facts, which are not disputed here, are taken from the opinion of the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals (“OCCA”) resolving Mr. Stemple's direct appeal. See Stemple v. State, 994 P.2d 61 (Okla.Crim.App.2000). In October 1996, Mrs. Stemple's body was found near Highway 75 in Tulsa County, Oklahoma. Her death was briefly investigated as a hit-and-run accident, but as the investigation progressed, the Tulsa Police Department began to suspect that Mr. Stemple had orchestrated the death of his wife. Mr. Stemple was ultimately charged in her death with First Degree Malice Aforethought Murder, Conspiracy to Commit First Degree Murder, and Attempted First Degree Murder.

At trial, the prosecution put forth evidence that Mr. Stemple was having an extra-marital affair with Dani Wood and that he concocted a plan to murder his wife and collect the proceeds of her life insurance policy. Sixteen year-old Terry Hunt, Mr. Stemple's co-defendant and Ms. Wood's cousin, testified that Mr. Stemple hired him to assist with the murder, promising to pay him $25,000 to $50,000 if they collected the insurance proceeds. Mr. Hunt further testified that he and Mr. Stemple killed Mrs. Stemple by beating her with a baseball bat wrapped in plastic wrap and running over her numerous times with Mr. Stemple's pickup truck.

Additionally, the prosecutor introduced a five-minute long videotape of an interview Tulsa police officers conducted with Mr. Stemple prior to his arrest, during which Mr. Stemple stated that he knew “how ugly this looks for me,” summarized the evidence which he believed the police would use against him, and eventually invoked his right to counsel. The prosecutor also introduced a handwritten jailhouse confession by Mr. Stemple; other jailhouse documents created by Mr. Stemple, including a witness list; and testimony from Mr. Stemple's fellow inmates that he had asked them to arrange the death of several witnesses, given them a copy of his confession, and sought their assistance in hiring people to coerce exculpatory statements from Mr. Hunt and Ms. Wood. Ultimately, the jury convicted Mr. Stemple on all three counts.

During the separate penalty-phase proceeding, the jury found the existence of two aggravating circumstances: (1) Mr. Stemple committed the murder for remuneration or the promise of remuneration; and (2) the murder was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel. The jury therefore recommended that Mr. Stemple be sentenced to death on the murder conviction. The trial court sentenced him in accordance with the jury's recommendations.

On direct appeal, the OCCA affirmed Mr. Stemple's convictions and sentences for the murder and conspiracy charges but reversed his conviction for attempted murder. The United States Supreme Court denied his petition for a writ of certiorari. Stemple v. Oklahoma, 531 U.S. 905, 121 S.Ct. 247, 148 L.Ed.2d 178 (2000). Mr. Stemple did not file an application for post-conviction relief in state court.