47th murderer executed in U.S. in 2005

991st murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Delaware in 2005

14th murderer executed in Delaware since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

| |

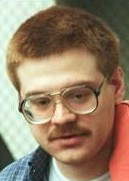

Brian D. Steckel W / M / 25 - 36 |

Sandra Lee Long W / F / 29 |

Summary:

Steckel met 29 year old Sandra Lee Long approximately one week before her murder. Steckel gained access to her apartment by asking to use her telephone. Once inside, he pretended to use the phone, then demanded sexual favors. When she refused, Steckel beat her and threw her onto a couch. During the struggle, Sandra, bit Steckel’s finger causing it to bleed. Steckel then strangled her with a pair of nylons then a sock, causing her to lose consciousness. Steckel then sexually assaulted her, first using a screw-driver he brought with him, and then by raping her anally. He then dragged her to the bedroom and set the bed on fire, then fled the scene. Later the same day, the News Journal received an anonymous phone call from a male who identified himself as the “Driftwood Killer.” The man named his next victim by name. The News 4 Journal contacted the police, and the police brought the woman into protective custody. The woman had previously reported to the police that she had been receiving harassing phone calls with a “very lurid, very sexual” content. The authorities had traced these calls to Steckel. Steckel was arrested in connection with an outstanding harassment warrant for the phone calls to the woman. During the interview, Steckel confessed in detail to his crimes against Sandra Long, as well as other murders.Although some portions of Steckel’s confession lacked credibility, many of the details were confirmed by subsequent investigation by the police, including the autopsy of Sandra, the fire department’s discovery of the points of origin of the fire, DNA testing of blood found on Sandra’s apartment door, which matched Steckel, and the discovery of the nylons, lighter and screwdriver used in the attack. During his trial, Steckel sent a copy of Sandra Long's autopsy to her mother, writing "Read it and weep. She's gone forever. Don't cry over burnt flesh."

Citations:

Steckel v. Carroll, Not Reported in F.Supp.2d, 2004 WL 825302 (Del. 2004) (Habeas).

State v. Steckel, 708 A.2d 994 (Del.Super. 1996).

Last Words:

He repeatedly apologized for his crimes, professed love for his family and supporters and said he accepted his punishment. ”I want to say I’m sorry for the cruel things I did. I’m not the same man I was when I came to jail. I changed. I’m a better man . . . I walked in here without a fight and I accept my punishment. It is time to go. I love you people.” He also told his cousin and a friend who were witnesses to his death to tell his 12-year-old daughter, “I said no excuses.”

Steckel’s execution seemed to take longer than usual, said witnesses who had seen previous executions in Delaware. Steckel spoke for nearly 12 minutes, whereas other executions have generally taken about three minutes. Twice, before he closed his eyes, he said “goodbye” and appeared to brace himself, only to look around and continue talking. At one point, he looked up at warden Thomas Carroll to say, “I didn’t think it would take this long.”

Last Meal:

Cheese steak, cole slaw and Pepsi.

Internet Sources:

Delaware Department of Correction

Inmate: Brian D. Steckel

DOB: 12/14/1968

Race: White Gender: Male

Offense: Murder 1st (3 Counts)

Sentenced to Death: 01/08/1997

Date of Offense: 09/02/1994

Broke into the home of Sandra Lee Long, raped and strangled her then set her on fire. He later gloated in letters to Long's mother.

Statement by Gov. Minner Following the Execution of Brian D. Steckel (Friday, Nov. 4, 2005)

Smyrna – “The State of Delaware this morning carried out Brian D. Steckel’s penalty for the murder of Sandra Lee Long. I pray that the completion of this sentence, recommended by a jury and imposed by a judge, will bring some amount of closure to Ms. Long’s family. May God have mercy on Mr. Steckel.”

"Murderer longed to kill, attorney says; Brian Steckel scheduled to die by injection on Friday," by Sean O'Sullivan. (10/31/2005)

Police and prosecutors say Brian "Red" Steckel was a serial killer who just never got the chance to kill again. Steckel apparently saw himself the same way. Before he raped Sandra Lee Long, then set fire to her apartment in 1994, he boasted to strangers that he'd killed people in other states and that his tattoos came from prison.

After his arrest, he confessed to several murders he had nothing to do with, even offering what appeared to be a signature detail -- bite marks on the buttocks. Authorities, however, were never able to connect Steckel to any other killings and eliminated him as the killer in many of the cases. Steckel is set to die Friday by lethal injection for Long's murder.

Former New Castle County detective John Downs, who investigated the case, said he believes Steckel "thought about committing a murder for a long time. We got him relatively early in his career. This was something he'd worked at." In interviews with Steckel, Downs, who is now a prosecutor, said he detected "a sense of excitement that he had done what he dreamed about." Even attorney Joseph Gabay, who defended Steckel at trial, said Steckel "had all the triggers, all the mechanisms" early in his life that turn a person violent. Gabay said Steckel seemed to like the attention his crimes brought, and his horrendous behavior was a twisted way of exercising control. "He liked people to be afraid of him."

If Steckel had not been caught, Gabay believes he would have killed again. Hours after he tortured Long and set fire to her unit in the Driftwood Club apartments in Prices Corner, Steckel called The News Journal to brag, giving himself the name "The Driftwood Killer." He also said he was going to kill again, and gave the newspaper a prospective victim's name -- which was given to police. Using that information, police focused on Steckel as the likely killer of Long and hours later, New Castle County police Patrolman Michael McGowan picked up Steckel, who was drunk, as he walked down Union Street in Wilmington.

Imposing size

Steckel is an imposing figure, standing 6 feet 3 inches tall and weighing a lean 195 pounds at the time of his arrest. He'd been a furniture mover and was quite strong. Several months before he killed Long, he got into a fight with a bartender on Union Street and flattened him with a single punch. Even though Steckel was clearly drunk, on Sept. 3, 1994, when the officer encountered him on Union Street, McGowan, now a lieutenant, said he was wary of approaching Steckel without backup. McGowan said he wasn't sure the man was Steckel until he saw a distinctive tattoo on his left forearm -- the name "Ashley" -- and he knew he had his man. McGowan convinced Steckel he was giving him a break on a public drunkenness charge and would give him a ride home. Instead, McGowan drove him to police headquarters, where he was booked for murder.

Once in custody, Steckel mailed more than 75 letters, some confessing to murders in other states and others bragging about the Long murder or making threats. In one, to Long's mother, Virginia Thomas, he included the autopsy report of his victim with a note in the margin, "Happy, Happy. Joy Joy. Read it and weep. She's gone forever. Don't cry over burnt flesh." He threatened court personnel and frightened his first team of attorneys, from the Public Defender's Office, off the case. He also spit on prosecutors.

Thomas Pedersen, who prosecuted Steckel and is now a private attorney, said it was "the most gruesome case I was ever involved with. ... If the death penalty is ever justified, Brian's case is probably the best candidate I can ever think of."

Specifics of what happened that day are difficult to know with certainty because Steckel has constantly changed his story. On the night he was arrested, an apparently remorseful Steckel asked the officers interrogating him, "Don't you get tired of dealing with people like me? ... Can't you see I'm worthless? I mean, why are you wasting time on me?" according to a transcript in court records. Downs responded, "We've got to find out what, what's going on with you." "I [expletive] killed somebody," Steckel shot back. "What the [expletive] do you mean 'What's going on?' "

Steckel then went on to say he met "Sandy" through a "sleazy thing in the neighborhood" and moments later objected to his own description saying, "She's not sleazy, man. I took her [expletive] life, man. She didn't deserve to die. ... There is something wrong with me inside of me and I ... I just go off the [expletive] handle man. And it's just not right, you know what I mean? I guess now I finally got stopped." During the interrogation, Steckel changed the details several times. At one point he said he killed Long because she refused to have sex with him. At another, he said they had had consensual sex several times in the days before the murder. Later, he said Long was pregnant, possibly with his child, and that she was demanding support payments.

Months later, in a prison interview with The News Journal, he denied he had any involvement at all. "I'm aware of what happened, but I'm not the one who committed the act," Steckel said, alleging it was a drug-using married man with children who killed Long. He is still changing his story, according to prosecutors at his Board of Pardons hearing on Friday. In the most recent version, told to a prison official this month, Steckel alleges Long started the fight by accusing him of stealing drugs and then attacking him with a frying pan.

On the day he was arrested, Steckel confessed to six other killings, four in Delaware and two in Pennsylvania. He claimed one victim was a 15-year-old paper carrier. He later would confess to other killings in Maine, Las Vegas, Florida and California. He told police, "I'm an animal. ... I hurt anybody, man. Been hurting people for a long time. If you let me walk out the door, I'd go do it again." Police checked out Steckel's stories and the next day confronted him with the fact that someone else had been arrested and convicted of killing the paper carrier. Steckel immediately recanted: "I was just shooting the breeze, man, and I was drunk ... when I was saying that ... I never killed anyone else," according to court records.

Unsolved case

Pennsylvania State Police, however, are interested in talking to Steckel one last time before he is executed. One of the murders he confessed to -- killing Fountain Hill, Pa., resident Frances Kiefer, a neighbor of his mother -- remains an unsolved missing person case. Kiefer hasn't been seen since 1994. At trial, prosecutors argued that Steckel didn't know Long either at all or very well. In police interviews, Steckel said he picked Long, who had long, dark hair, because he thought she was pretty and had a nice body.

Long was a divorced data-entry clerk who lived across the hall from the apartment where Steckel had been staying with friends for a few weeks. Long's family would not give interviews before the execution, but at legal proceedings have described her as a loving person who was close to her family and friends. She was the youngest of four children and also had worked as a waitress and a saleswoman. At Friday's Board of Pardons hearing, Long's mother said her daughter was a giving person who would offer help to whomever needed it. And on Sept. 2, 1994, Steckel went to her door around lunchtime asking to use her phone, according to the most consistent version of his confession. Other tenants said Steckel regularly asked to use people's phones, saying he needed a touch-tone phone to get his messages.

Prosecutors said Steckel knocked on Long's door intending to rape and murder her. He was carrying nylon stockings and a tube sock to bind her and a screwdriver. Once inside, Steckel unplugged the phone so Long couldn't call 911, then turned on the 29-year-old. He claimed to have punched her in the face and thrown her across the room. Long's body had marks on it indicating she attempted to fend off Steckel's attacks with the screwdriver and teeth marks on Steckel's finger indicate she bit him, drawing blood. Steckel said he used the nylons and the tube sock to strangle Long into unconsciousness, then sexually assaulted her and raped her with the screwdriver.

'I watched the flames'

Steckel then set fire to the bedspread and curtains, he told police, for "something different, man ... some excitement. ... I watched the flames and I walked out." Long woke up afterward, surrounded by flames and thick smoke, and cried out. Lane Randolph, a tree trimmer who was passing by and saw the flames, testified that when he arrived he heard weak calls of, "Help me, please." He kicked out a window of the basement apartment and called to Long, briefly grabbing her hand. He had it for 30 to 40 seconds but flames were burning him. "The room was totally black with smoke. Smoke and heat were pouring out. I pulled with all my might but I just couldn't pull her [to safety]," he said on the stand. A co-worker, John Hall, kicked in the apartment door, but flames also prevented him from getting to Long. "I felt like I was in total hell," Hall testified. After the fire was put out, Hall said he went back to look through the window and saw Long's body. "She was just folded like a flower in a microwave," he said.

Died of burns, smoke The medical examiner said Long died from severe burns over 60 percent of her body and smoke inhalation. In his initial confession, Steckel said he thought Long was pregnant. Long's family also believed she was four to five months pregnant. An autopsy report at trial that included information on an examination of Long's uterus showed no indication of pregnancy. Long's family members, however, wonder if Steckel's brutal attack and the fire eliminated evidence of a child. At trial, defense attorneys presented evidence that Steckel had suffered sexual abuse as a child and had emotional and mental problems as young as age 12. He'd also spent time in several juvenile facilities.

At Friday's Board of Pardons hearings, relatives testified that Steckel was not a heartless monster. One aunt, Nancy Renniger said, "You could not find a more gentle child." Steckel's brother Robert recalled ripping open Christmas presents with his younger sibling and playing together. At the time of the murder, Steckel had a daughter. Now 12, she left the Board of Pardons hearing in tears after her father spoke. While Steckel offered no excuses on Friday, relatives and attorneys Joseph Bernstein and John Deckers pointed to a history of mental problems. Gabay said Steckel was angry and had delusions of grandeur when he was young -- such as believing he would one day own a professional basketball team, though he dropped out of school after not doing well, and never held a job for very long. In one of his confessions to police, Steckel said he was a messed-up person. "I was a redhead. People taunted me. People did [expletive] to me. You know what I mean? Pushing me aside. Step on me. I got tired of that, man. I just fought back. ... My family loved me and now they're ... scared of me cause they made me this way. The family. The system. Society."

Seemed to want death

Gabay said that before and during trial, Steckel seemed intent on getting the death penalty. "You can explain some actions to a jury," Gabay said. Others, such as Steckel's taunting letters to the family of his victim, are impossible. Steckel also refused defense attorneys' attempts to have him evaluated for mental health problems, and he resisted attempts to show evidence that he was sexually abused as a child, things attorneys hoped a jury would see as mitigating factors. The jury, which convicted him, ultimately voted 11-1 that he should be put to death.

After the trial, Virginia Thomas said the death penalty was "most justly deserved." When Superior Court Judge William C. Carpenter Jr. sentenced Steckel to death in 1997, calling his crime "exceedingly depraved, cruel and vicious," Steckel smiled. Gabay said he believes Steckel isn't a threat behind bars. "Outside, he is a dangerous guy. Very dangerous," said Gabay. "He's just good at being in jail." Gabay said that outside, Steckel does not have the 24-hour-a-day structure that jail provides.

At the Board of Pardons hearing, defense attorneys and relatives argued Steckel had undergone a transformation, matured and was truly remorseful.

Sandra Jones, a death penalty opponent and an assistant professor of sociology at Rowan University, said she believes Steckel could make a contribution even behind bars. Jones has worked with Steckel and other Delaware death-row inmates for the past year for a book she is writing. Jones said she could not explain Steckel's crime or his early behavior, but said that now, "I think there is good reason to believe he could be OK on the outside," adding that she would not mind having him as a neighbor. Jones said that when she met him, from press accounts she expected Hannibal Lecter, the cannibalistic killer in the movie "Silence of the Lambs," but the reality "couldn't have been further from the truth." "He's a really neat guy," she said, adding that he was probably "the type of kid who tried too hard to get people to like him. A little awkward, sometimes obnoxious." She said he has a "playful and fun" sense of humor and is humble.

The Board of Pardons nonetheless refused to commute Steckel's sentence. He has one appeal left, to the U.S. Supreme Court. Gabay said he believes Steckel is remorseful and wants to die for his crimes, judging by his surprise address to the jury at the end of his trial.

Steckel told the jury, "I didn't know how to say I'm sorry. How do you tell someone's family you're sorry for strangling them? ... How do you do such a thing? I don't know. I ask you people to hold me accountable for what I did. I've gotten away with so much in my life that I stand here today ... I know I deserve to die for what I did to Sandy. ... I'm prepared to give up my life because I deserve to."

Brian D. Steckel was convicted of raping and strangling a pregnant 29-year-old woman. Steckel met Sandra Lee Long approximately one week before the murder. He stayed occasionally with Sandra’s neighbors. After Steckel witnessed a verbal dispute between Sandra Long and the wife of his friend, he commented, “I should rape the bitch.”

On September 2, 1994, the day of Sandra Lee Long’s murder, Steckel gained access to her Driftwood Club Apartment by asking her if he could use her telephone. Once inside, Steckel pretended to use the phone, but unplugged it from the wall. Steckel then demanded sexual favors from Sandra, and she refused. Steckel beat Sandra and threw her onto a couch pinning her beneath him. During the struggle, Sandra bit Steckel’s finger causing it to bleed. Steckel then attempted to strangle Sandra with a pair of nylons which he brought with him. When his attempts to strangle her with the nylons failed, Steckel grabbed a sock and continued to strangle her with the sock. Sandra eventually fell unconscious, and while unconscious Steckel sexually assaulted her, first using a screw-driver he brought with him, and then by raping her anally.

Sandra remained unconscious while Steckel dragged her to the bedroom and set the bed on fire using a black lighter which he had brought with him. Steckel also set fire to the curtain in Sandra’s bathroom. After setting the fires, Steckel departed to have a few beers with a former coworker. Steckel drove to the man's residence during lunch time. Although the man came home for lunch, he then returned to work, leaving Steckel alone with his wife. Steckel then asked the woman to drive him to a liquor store to purchase beer. The route she took to the liquor store went past the now burning apartment of Sandra Long. Upon passing the apartment, Steckel became visibly angry and slouched down in his seat. Steckel asked the woman why she went this way, and she said, “What’s the matter with you, you’re acting like you killed someone.” Steckel then denied killing anyone and instructed her to proceed to the liquor store. While driving, she noticed that Steckel’s finger was bleeding, but she dismissed the wound. After drinking several beers back at the woman’s home, Steckel requested another ride from her, and she dropped him off at a convenience store on Lancaster Avenue.

In the meantime, police, firefighters and passers-by responded to Sandra Long’s burning apartment building. Two men who worked as tree trimmers were driving past the apartments, saw the flames and stopped to render assistance. When they approached the building, they heard Sandra, who had regained consciousness, screaming for help. Lane Randolph testified at Steckel's trial that he heard Sandra cry out weakly, "Help me, please." He kicked out the window of the basement apartment, and was able to grasp her arm briefly, but he was driven back by the flames. His co-worker, John Hall, was able to kick in the door of the apartment, but could not reach Sandra through the flames. Sandra died in her apartment and over 60% of her body was badly burned.

Later the same day, the News Journal received an anonymous phone call from a male who identified himself as the “Driftwood Killer.” The man named his next victim by name. The News 4 Journal contacted the police, and the police brought the woman the caller had identified into protective custody. The woman had previously reported to the police that she had been receiving harassing phone calls with a “very lurid, very sexual” content. The authorities had traced these calls to Steckel. Based on the phone calls to the News Journal and the connection to the woman under protection, the authorities began to suspect Steckel of Sandra’s murder. Steckel was arrested in connection with an outstanding harassment warrant for the phone calls to the woman. Steckel was visibly intoxicated upon his arrest and agitated, so the police did not question him immediately. When Steckel awoke the next morning, he asked police, “So I killed her?”

The police advised Steckel of his Miranda rights and offered him breakfast. Steckel waived his rights and was then interviewed by the police. During the interview, Steckel confessed in detail to his crimes against Sandra Long. Steckel recounted his attempts to strangle Sandra, his rape of Sandra and the fires he set. Steckel told police he had taken the nylons, screw driver and lighter with him for use in the attack. Steckel also told police that he discarded the screwdriver in a nearby dumpster. Steckel further confessed to harassing the woman that police were protecting and calling the News Journal and threatening her. With Steckel’s permission, he was taken to a forensic dentist who examined the wounds on Steckel’s finger. The dentist opined that the wound had been caused within 24 hours by Sandra’s teeth. Although some portions of Steckel’s confession lacked credibility, many of the details were confirmed by subsequent investigation by the police, including the autopsy of Sandra, the fire department’s discovery of the points of origin of the fire, DNA testing of blood found on Sandra’s apartment door, which matched Steckel, and the discovery of the nylons, lighter and screwdriver used in the attack.

During his trial, Steckel sent a copy of Sandra Long's autopsy to her mother, writing "Read it and weep. She's gone forever. Don't cry over burnt flesh." The jury convicted Steckel of three counts of Murder First Degree, two counts of Burglary Second Degree, one count of Unlawful Sexual Penetration First Degree, one count of Unlawful Sexual Intercourse First Degree, one count of Arson First Degree and one count of Aggravated Harassment. Following a penalty hearing, Steckel was sentenced to death.

The victim's sister, Karen Thomas, said she does not know if she will attend the execution, but another family member may attend. "I don't care if he lives or dies, I just want people to remember Sandra. She was beautiful. An angel," she said.

Steckel's latest appeal to the Delaware Supreme Court, arguing that Delaware's death-penalty law was unconstitutional, was turned down in September. He had argued, unsuccessfully, that he had ineffective attorneys at trial. He admitted his crimes and told jurors during the penalty phase of his trial that he deserved to die. "I ask you to hold me accountable for what I did ... I know what I did was wrong: it was selfish [and] despicable," he said. Prosecutors also presented letters Steckel had written to the victim's mother, Virginia Thomas, that read: "I'm not sorry for what I did to your daughter. She deserved everything she got." Ten years ago, Steckel mailed a confession to Fountain Hill police claiming responsibility for the abduction and murder of 44-year-old Frances Kiefer. Steckel's former neighbor disappeared from her S. Hoffert Street home on March 22, 1994. Frances has never been found.

National Coalition to Abolish Death Penalty

Do Not Execute Brian Steckel!

DELAWARE - Brian Steckel - November 4, 2005

Brian Steckel, a white man, faces execution in Delaware on Nov. 4, 2005 for the Sept. 2, 1994 rape and murder of Sandra Lee Long. If executed, Steckel will be the first person executed in Delaware in four years.

There was one major problem with Steckel’s trial. The court had decided to admit an audio recording of Steckel’s interrogation on the condition that one question was taken out of the tape. Unfortunately that question was heard by the jury. The question was, “You told me yesterday that you killed others as well.” Although the trial judge then ruled the tape inadmissible and instructed the jury to disregard it, it is clear the effect that such a lapse could have on the jury. Trial counsel did not move for a mistrial at the time. Therefore, appellate courts ruled that they could not hear the new motion for retrial on appeal when the original court had not had the opportunity to rule on the motion.

Clearly such an admission as this warrants a mistrial regardless of when the claim is raised. Steckel was cooperative with authorities during interrogation. He suffers a history of alcohol and substance abuse. Steckel also suffered childhood sexual abuse, neglect, and emotional abuse. According to psychiatrist testimony at trial, Steckel has both Attention Deficit Disorder and Antisocial Personality Disorder. Finally, Steckel is a valued member of a loving family. Please write Gov. Ruth Ann Minner requesting that Brian Steckel’s sentence be commuted to life in prison without parole.

"Convicted killer’s last words express acceptance," by Sean O'Sullivan. (11/04/2005)

SMYRNA — The last words spoken by convicted killer Brian Steckel before a lethal mix of chemicals entered his bloodstream early today were, “I’m at peace.” Steckel, 36, was executed at the Delaware Correctional Center at 12:21 a.m. for the 1994 rape and murder of Sandra Lee Long.

Steckel, dressed in a white prison jumpsuit, was already strapped to a cross-shaped table with an intravenous tube in his arm when witnesses entered the execution chamber, known as Building 26, at the Smyrna prison. He repeatedly apologized for his crimes, professed love for his family and supporters and said he accepted his punishment.

”I want to say I’m sorry for the cruel things I did. I’m not the same man I was when I came to jail. I changed. I’m a better man … I walked in here without a fight and I accept my punishment. It is time to go. I love you people.” He also told his cousin and a friend who were witnesses to his death to tell his 12-year-old daughter, “I said no excuses.”

Steckel’s execution seemed to take longer than usual, said witnesses who had seen previous executions in Delaware. Steckel spoke for nearly 12 minutes, whereas other executions have generally taken about three minutes. Twice, before he closed his eyes, he said “goodbye” and appeared to brace himself, only to look around and continue talking. At one point, he looked up at warden Thomas Carroll to say, “I didn’t think it would take this long.”

Prison officials said there was no malfunction or problem with the execution. Carroll just allowed Steckel more time.

Long’s mother, Virginia Thomas, who witnessed the execution spoke briefly afterward to thank prosecutors, police and the courts for their assistance during this “terrible nightmare.” “Now, hopefully, we will have some peace and closure.”

Brian Steckel From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Brian David Steckel (December 14, 1968 – November 4, 2005) was a convicted murderer executed in the U.S. state of Delaware. On September 2, 1994, he was convicted of the rape and murder of 29-year-old Sandra Lee Long near Prices Corner, near Wilmington.

Crime

On September 2, 1994, Brian Steckel knocked on Long's door and asked if he could use her telephone. He then unplugged the telephone and demanded sex from her. After she refused he threw her onto a couch and attempted to strangle her with some pantyhose. The pantyhose broke, so he continued his attack with a sock. After she succumbed to the lack of oxygen, he penetrated her first with a screwdriver he had brought with him, and then sodomized her. He dragged her to a bedroom, where he set her and the bedroom curtains on fire.

Steckel left the scene and went to the home of a former co-worker for a few beers. The man left, and so Steckel got the man's wife to drive him to the liquor store. The route she chose took them past Long's apartment, which was now on fire. The woman said that Steckel became noticeably agitated and became angry when she jokingly said "you look like you've killed someone."

At the apartment, two men tried to rescue Long, who had since regained consciousness. They could not get into the burning apartment, however, and she died from smoke inhalation and burns to 60 percent of her body.

Within hours of the fire, a man called The News Journal saying he was the "Driftwood Killer" and named his next victim. This woman was put into protective custody by police, where she told them that she had been receiving phone calls that were "very lurid, very sexual." The calls to the newspaper and the woman were traced to Brian Steckel, and he was arrested over an outstanding harassment warrant. Steckel was intoxicated at the time of the arrest and so given the night to sleep it off. The next morning, after waiving his Miranda rights, he confessed to the attack on Long. A forensic dentist determined that a bite wound on Steckel's finger had been received in the last 24 hours, by Long's teeth.

Trial and imprisonment

He was convicted in New Castle County of three counts of first degree murder (one count of "intentional" murder and two counts of felony murder). After the separate penalty phase, he was sentenced to death on January 8, 1997, by a vote of 11-1. During the penalty phase he told the jurors that: "I ask you to hold me accountable for what I did … I know what I did was wrong: it was selfish [and] despicable."

Steckel was otherwise unrepentant for his crime. During his trial he sent Long's mother a copy of the autopsy report attached to a note that read "Read it and weep. She's gone forever. Don't cry over burnt flesh."

The sentence and conviction were affirmed by a Delaware Superior Court on May 22, 1998. Throughout 1998 and 1999, Steckel continued to appeal his conviction and sentences, claiming that he had ineffectual defense. This claim was rejected by the Superior Court on August 31, 2001, and by the Delaware Supreme Court on April 11, 2002. Other appeals for the writ of habeas corpus were denied by U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware and the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. Steckel also tried to challenge the constitutionality of the death penalty laws in place in Delaware at the time of his sentencing. On September 30, 2005, a Superior Court set an execution date of November 4.

Death

For his last meal he ordered cheesesteak, coleslaw and a Pepsi. During his last statement he said: "I want to say I'm sorry for the cruel things I did. I'm not the same man I was when I came to jail. I changed. I'm a better man. … I walked in here without a fight, and I accept my punishment. It is time to go. I love you people. … I'm at peace." He was pronounced dead at 00:21 hrs EDT on November 4, 2005 after being executed by lethal injection at the Delaware Correctional Center, near Smyrna.

Fordham University law professor Deborah Denno, a death penalty expert, said that descriptions of the execution seem to suggest that there were several failures in injecting the drugs. Witnesses said several audible clicks (from the lethal injection machine, which led to them getting rid of the computer) were heard during the twelve minutes after Steckel finished his last statement. During this time Steckel was still lucid and continued to make several comments to his family members and friends who witnessed the execution. She said it appears that the sedative and paralytic drugs failed to take effect as Steckel was seen to convulse. Delaware Department of Correction spokeswoman Beth Welch said that nothing went wrong with the execution and the length of time was just due to the Warden giving Brian Steckel more time for his statement.

"First-Hand Account Of Brian Steckel's Execution," by Nicole Vandeputte. (SMYRNA, DE - WMDT) 11/4/2005

Bells rang outside the Smryna prison in protest of the court-ordered execution of Brian Steckel. "I don't think it's a process that contributes to healing any of the things or making society safer or healing people's pain," said Kristin Froelich, who opposes the death penalty.

Just a few feet away were people who felt his death would bring justice, including April Walters. She has no pity for the man who tortured and killed her best friend 11 years ago. "This is justice for all the sick people out there that think they can do whatever they can and that they're God. He wanted to be God that day. He killed her, he took her life, he was trying to be God. He's not God," she said.

The protestors stood just a few feet from where I'm standing. I was actually inside. I served as an official media witness, which means I was present during the execution of Brian Steckel. Also there was a cousin and family friend; he looked at them the entire time, and didn't look at anyone else. He talked to them, apologized to them. He also apologized to his mother, and his 12 year old daughter. He even apologized to family of Sandra Long, her mother was also in the room, and at 12:21, Steckel was pronounced dead. "We want to thank everyone for their love and support, now hopefully we will have some peace and closure," said Virginia Thomas, Sandra Long's mother.

Closure won't come as easily to Steckel's family. "We lost a family member tonight, so now it's another family that has to go through our grieving. Is this gonna bring closure to anybody? I don't think so," said Mary Kolesnik, Steckel's cousin.

The only one who remained emotionless was Steckel. His last words were, "It's time to get out of here; the journey away begins," then looked at his family and said, "I'm at peace."

Governor Ruth Ann Minner issued a statement shortly after his execution. She said she prays the completion of this sentence, recommended by a jury and imposed by a judge, will bring some amount of closure to Ms. Long's family. She added, "May God have mercy on Mr. Steckel."

"Death penalty foes gather again, but see little progress; 'There must be other ways that you can punish people and do justice,'" by Esteban Parra and J.L. Miller. (11/04/05)

Brenda Lints knew as early as the 10th grade that she opposed capital punishment, a conviction influenced in part by her Catholic faith.

It was years before the Dover resident's brother, David Dawson, was found guilty of the 1986 murder of Madeline Marie Kisner, stabbed to death in her Kenton home. Dawson was executed in April 2001.

"I never knew I would be faced with it," said Lints, who joined about 50 protesters late Thursday outside the Delaware Correctional Center near Smyrna, where state officials were preparing to execute Brian D. Steckel for the 1994 rape and murder of Sandra Lee Long.

"I think they should stay in jail until they rot so that they can think of the person they murdered every day," Lints said. "Two wrongs don't make a right."

Inside the prison compound, in an area penned by posts and orange plastic chain-link fencing, she and other death-penalty protesters gathered around a bell that organizers planned to ring 50 times, one for each of the 14 inmates executed in Delaware since 1992 and 36 times for their victims. Many carried signs with slogans such as "Execution is No Solution" and "I Support a Moratorium."

Tom Eleuterio, president of Delaware Citizens Against the Death Penalty, said protesters hoped to show that they don't want the state to carry out an execution in their names.

Across a street from the protesters, in another penned area, a different group carried signs supporting the death penalty.

"He's still going to die," Dan Blevins, a friend of Long's family from Boca Raton, Fla., shouted as the bell began to toll. "He's going to hell."

Nicholas Long, the victim's stepson, held a sign with Long's photograph. "We're going to get some justice at 12 o'clock," he said. After the execution, Long's relatives planned to gather and celebrate, he said. "It's been 11 years. We need to get justice."

Definitions of justice differ.

"There must be other ways that you can punish people and do justice, not revenge," Dover resident Marion Boon said at a death-penalty protest outside Legislative Hall in Dover hours earlier.

Many of those who came have been there before, protesting earlier executions.

Veteran death penalty opponent Anne Coleman and Marian Harris, head of the House of Pride substance abuse and housing program, hugged each other and caught up on old times.

"It's been four years since we've been here, and I keep hoping it will be the last one. It makes no sense," Harris said.

Defense attorney Sandra Dean made her customary appearance at the protest, and although she decried the death penalty, she pointed to some incremental progress since Delaware's last execution.

Dean noted that the U.S. Supreme Court has banned the execution of people who were juveniles when they committed murder, and it has outlawed the execution of people who are "mentally retarded."

One of Dean's former clients, Gary W. Ploof, is awaiting execution for murdering his wife, Heidi.

The protest was one of four throughout the day. All were organized by Delaware Citizens Opposed to the Death Penalty and Because Love Allows Compassion; the first took place in St. Joseph's Church in Wilmington.

"It's important that we pray on a day like this," Wilmington lawyer Kevin J. O'Connell told 13 other death penalty opponents who gathered there. "It is a source of hope in a time that can seem to be hopeless."

The group prayed for Long's and Steckel's families and called for an end to the death penalty.

"So that we no longer seek to end violence with violence," said the Rev. Jay R. McKee, associate pastor of St. John the Baptist-Holy Angels Parish.

Melissa Weise, 23, of Wilmington, said she came to the service because she wanted to show her support for life. Death, she said, should be left "in God's hands."

A prayer service Thursday evening at Thomas More Oratory in Newark drew 13 people. Among them was Vince Fisher of Tea Neck, N.J., who said he opposes capital punishment.

"You have to model the behavior that you want and if you believe you want people to stop killing people, then you shouldn't kill people," said Fisher, a member of the Harlem chapter of the Campaign against the Death Penalty.

"Convicted Killer Executed In Delaware," by Randall Chase. (AP UPDATED: 8:27 am EST November 4, 2005)

SMYRNA, Del. -- Brian Steckel, who called a newspaper to boast about how he had raped and killed a Wilmington woman and warn that he would kill again, was executed by lethal injection early Friday.

Steckel, 36, was pronounced dead at 12:21 a.m. at Delaware Correctional Center. The execution was carried out after the U.S. Supreme Court refused without comment Thursday to consider a last-minute appeal, and Gov. Ruth Ann Minner declined to grant a reprieve.

"I just want to say I'm sorry for the cruel things I did," Steckel said as he lay strapped to a gurney waiting for the lethal drugs to course through his body. "... I'm not the same man I was when I came to jail. I'm a better person."

Steckel, who grew up in Fountain Hill, Pa., professed his love for his family, whom he had asked not to witness his death, and apologized to his mother for what he called "25 years of hell" that he put her through.

He also apologized to the family of Sandra Lee Long, a neighbor who burned to death in a fire Steckel set after asking if he could use her telephone, choking her into unconsciousness, raping and sodomizing her.

Reporter Witnesses Execution

Witnesses entered the execution chamber about seven minutes after midnight; Steckel was pronounced dead about 14 minutes later.

"Why is it taking so long?" Steckel said at one point, looking up at prison warden Thomas Carroll.

Despite the length of time for the execution, there were no technical difficulties, according to deputy warden Betty Burris.

"There is no set time required for a final statement," said Department of Correction spokeswoman Beth Welch. "The length of the final statement is at the discretion of the warden."

While waiting for the drugs to take effect, Steckel stared at the ceiling and continued talking with his cousin, Mary Kolesnik, and a friend, Sandra Jones, asking if they had received his mail and even joking with them.

"You have beautiful eyes," he said, looking at Jones. "You, too, Mary. You too, Deckers," he said, smiling at his attorney John Deckers.

About 12:18 a.m., Steckel took a deep breath, gave a raspy, snorting wheeze, puffed his cheeks and blew a breath out, then was still.

Shortly before he died, Steckel said, "It's time to get out of here. The journey away begins ... I'm at peace."

Steckel was the 14th inmate executed by Delaware since the state resumed executions in 1992. The execution was Delaware's first since 2001, when Abdullah T. Hameen, 37, was put to death for a 1991 drug-related murder.

"The state of Delaware this morning carried out Brian D. Steckel's penalty for the murder of Sandra Lee Long," Minner said in a prepared statement. "I pray that the completion of this sentence, recommended by a jury and imposed by a judge, will bring some amount of closure to Ms. Long's family. May God have mercy on Mr. Steckel."

Steckel was arrested within hours of Long's death after making several telephone calls to The (Wilmington) News Journal to brag about the vicious killing and to identify another woman as his next victim.

While awaiting trial in prison, Steckel sent more than 75 taunting and threatening letters to prosecutors, a judge and others involved in the case. In one of seven letters sent to Long's mother, Virginia Thomas, he enclosed a copy of an autopsy report on which he had scribbled, "Happy, happy, joy, joy ... Read it and weep. She is gone forever. Don't cry over burnt flesh."

After the execution, Thomas thanked judicial system officials for their help in what she described as "this terrible nightmare."

"Now, hopefully, we will have some peace and closure," she said.

Kolesnik, Steckel's cousin, said she doubted that his death will bring closure to anyone.

About 60 demonstrators staged rallies for and against the death penalty outside the prison. Among them was Johnny Hall, 43, one of two men who tried in vain to pull Long from her burning apartment.

Hall was carrying a sign that said, "I was there. I watched her die."

"I feel that this man needs to die, and I'm out here to make sure that my opinion is out here," he said.

"Killer's brutal, vindictive actions make it hard to oppose death penalty," by Al Mascitti. (Opinion 10/30/05)

In any ranking of Delaware's death-row criminals, Brian Steckel must be counted among the scum de la scum.

Everybody condemned to die since Delaware reinstituted the punishment has either committed or participated in at least one murder, so Steckel's brutal rape and slaying of Sandra Lee Long in 1994 doesn't make him unusual.

What marked him as a monster in the public mind was his cruelty.

In the days after Steckel killed his victim and set fire to her apartment, he called The News Journal and boasted to journalists about his handiwork. Once he was captured he showed no remorse, then caused widespread revulsion by writing the victim's mother, Virginia Thomas, from prison to taunt her.

During his trial he sent Thomas a copy of Sandra Long's autopsy along with a note that read, "Read it and weep. She's gone forever. Don't cry over burnt flesh." He wrote Thomas more letters, thankfully intercepted by officials, gloatingly recounting grisly details of the crimes.

His supporters say a decade in prison has changed the violent young man who committed those atrocities. Indeed, with his thick eyeglasses and lethargic demeanor, the Brian Steckel who appeared before the state Board of Pardons on Friday hardly fit the image of a violent predator.

He offered apologies to the family he once tortured via the U.S. mail, but it didn't change Thomas' desire for the punishment to be carried out. "I want to go on with life and know that justice was done," she said.

Death-penalty opponents might be dismayed at Delaware's chronically high execution rate (the state recently slipped to No. 2 per capita, behind Oklahoma), the product of a capital punishment law that makes almost every first-degree murder punishable by death.

But even if the ultimate punishment were reserved only for the most despicable cases, Steckel would surely qualify.

At some level, Steckel himself seems to recognize this. He voiced no protest about his fate Friday. "If I have to die on [Nov.] fourth, I am ready to die," he said, and he directed his family not to plead for his life.

Of course, that doesn't mean Steckel is without his supporters. The hard-core opponents of the death penalty have vowed to stand vigil as Steckel's date with the gurney approaches, concluding with a candlelight vigil Thursday night outside the Delaware Correctional Center trailer where his life is scheduled to end.

Considering all these circumstances -- Steckel's acceptance of his fate, the especially cruel nature of his crimes, the desire of his victim's family for final justice -- the people protesting his execution must be uncommonly dedicated to the principle that capital punishment is evil.

Like those who give so much of their time and effort to protest abortion, such people believe in a moral authority higher than human law, even if they haven't been nearly as vocal or involved in the choice of U.S. Supreme Court nominees as those on both sides of the abortion issue.

On Friday, while Steckel appeared before the Board of Pardons, another young man, James E. Cooke Jr., stood in a courtroom accused of brutally raping and killing University of Delaware student Lindsey Bonistall before setting fire to her apartment.

The state, of course, is seeking the death penalty.

State v. Steckel, 708 A.2d 994 (Del.Super. 1996).

Defendant who was convicted of first-degree murder moved to strike death penalty as potential punishment. The Superior Court, Carpenter, J., held that statutory aggravating circumstance allowing imposition of death penalty for murder of child 14 years old or younger if defendant is at least four years older than child victim was constitutional.

Motion denied.

CARPENTER, Judge.

FN1. On September 17, 1996 the Court issued an opinion disposing of two pre-trial defense motions: the Motion to Suppress and the Motion to Sever. See State v. Steckel, Del.Super., Cr. A. No. IN96-06-1760, Carpenter, J., 1996 WL 659483 (Sept. 17, 1996) (Mem.Op.). At the time

that opinion was issued, the Court believed the matters presented in this motion to have been resolved by the parties. Unfortunately, that agreement never materialized. Thus, the Court now rules on the motion since the defendant's conviction makes the issue ripe for decision.

I. Procedural Posture

Mr. Steckel was originally indicted on two counts of Burglary Second Degree, two counts of Assault Third Degree, one count of Attempted Murder First Degree, one count of Unlawful Sexual Penetration First Degree, one count of Unlawful Sexual Intercourse First Degree, one count of Arson First Degree, and five counts of Murder First Degree. He was then reindicted on the additional count of Aggravated Harassment. The entire indictment, except Count XIV, Aggravated Harassment, relates to the September 2, 1994 assault, rape and murder of Sandra Lee Long, and the burning of her Driftwood Club apartment. Count XIV relates to obscene phone calls received by Susan Gell, the defendant's self-proclaimed next victim, between August 2 and August 13, 1994. After extensive discussions with defense counsel, the State nolle prossed five counts of the indictment: counts III and V, charging Assault Third Degree; count IV, charging Attempted Murder First Degree; and two counts of Felony Murder, counts XII and XIII, alleging criminal negligence. Accordingly, Mr. Steckel was tried on two counts of Burglary Second Degree, one count of Unlawful Sexual Penetration First Degree, one count of Unlawful Sexual Intercourse First Degree, one count of Arson First Degree, three counts of Murder First Degree, and one count of Aggravated Harassment.

Jury selection in the case began on September 10, 1996 and continued until September 17, 1996. The trial commenced on September 18, 1996 and lasted until October 1, 1996. The jury deliberated for approximately six hours over the course of two days and delivered their verdict on October 2, 1996: guilty on all counts of the indictment. The penalty hearing began on Tuesday, October 8, 1996 and was completed on Wednesday, October 16, 1996. The jury returned its sentencing recommendation on Thursday, October 17, 1996 and found that the aggravating circumstances outweighed the mitigating circumstances by a vote of eleven to one.

II. Discussion

It is the three convictions for first degree murder which render Mr. Steckel eligible for the death penalty pursuant to 11 Del.C. §§ 636 and 4209(a). Consequently, the defendant has challenged the constitutionality of the death penalty statute as written and as applied to him in this case. The defendant offers several arguments in support of his motion. First, he contends that the Delaware statute provides for so many statutory aggravating circumstances that it fails to adequately narrow the class of persons eligible for the death penalty. As such, the defendant maintains that the State has inappropriately stacked the statutory aggravating circumstances where the death penalty may be imposed, and thus has reached a point where it is violative of the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Second, the defendant asserts that the statute is violative of both State and federal constitutional standards in that it fails to provide for any consideration of mercy. The defendant's contentions are without merit and will be addressed seriatim.

The defendant first contends that the present statute is violative of federal constitutional standards in that it fails to adequately narrow the class of individuals who may be subject to the death penalty. Thus, the defendant maintains, Delaware's statute is constitutionally infirm due to the litany of aggravating circumstances provided for in the statute which, he argues, qualifies most convicted first degree murderers for capital punishment. To appropriately consider the defendant's argument, a brief overview of the evolution of the present statute is necessary.

The Delaware death penalty statute has been amended several times in recent years, and faced constitutional challenges at every turn. [FN2] The basic constitutional framework for capital punishment was established by the United States Supreme Court in Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153, 96 S.Ct. 2909, 49 L.Ed.2d 859 (1976), when it approved the constitutionality of death penalty laws which limited the discretion of the sentencing jury, but invalidated several mandatory death penalty statutes, including the Delaware statute in place at that time. The laws which were upheld in Gregg included three common features: (1) a bifurcated trial; (2) a requirement that juries find the existence of specific aggravating circumstances and consider mitigating circumstances before imposing the death penalty; and (3) expedited appellate review of all jury impositions of death sentences. See Lawrie v. State, Del.Supr., 643 A.2d 1336, 1345 (1994), cert. denied, 513 U.S. 1048, 115 S.Ct. 646, 130 L.Ed.2d 551 (1994). It was these guidelines which formed the pattern for the Delaware death penalty statute enacted in 1977. See id. at 1346 ("The General Assembly modeled § 4209 after the Georgia statute which the United States Supreme Court sanctioned in Gregg, and thereby incorporated the three aspects delineated above into Delaware's death penalty procedure.")

FN2. See, e.g., Sullivan v. State, Del.Supr., 636 A.2d 931 (1994); State v. Cohen, Del.Supr., 604 A.2d 846 (1992); State v. Ferguson, Del.Super., Cr. A. No. IN91-10-0576, Gebelein, J., 1995 WL 862123 (Aug. 25, 1995); State v. Deputy, Del.Super., 644 A.2d 411 (1994).

In 1991, significant changes were made to Delaware's statutory scheme regarding the imposition of capital punishment. Prior to 1991, a unanimous jury verdict was required to impose the death penalty. However, the new statute disposed of the unanimous verdict requirement and placed the ultimate decision-making responsibility in the trial judge. See Shelton v. State, Del.Supr., 652 A.2d 1, 6-7 (1995). These revisions were drafted to emulate the Florida statute that was upheld in Proffitt v. Florida, 428 U.S. 242, 96 S.Ct. 2960, 49 L.Ed.2d 913 (1976). See 68 Del. Laws Ch. 181, Synopsis (stating "this bill generally follows the Florida statute as approved by the United States Supreme Court"). The revised law transformed the jury's role in a capital murder trial from the absolute sentencing authority to that of an advisory capacity. When the amended 1991 statute was tested in State v. Cohen, Del.Supr., 604 A.2d 846 (1992), the Delaware Supreme Court found "the new law valid in all respects." Id. at 848 (emphasis added). Thus, it is clear that the statute as amended in 1991 is constitutionally sound, and therefore, the Court need only address the most recent amendments to the statute.

In 1994, the General Assembly expanded the list of statutory aggravating factors by adding sections (s) through (u) to 11 Del.C. 4209(e)(1). [FN3]

FN3. The Court notes that since the State only sought to prove one

statutory aggravating circumstance, 11 Del.C. § 4209(e)(1)(j), Mr. Steckel is not subject to the additional factors added in 1994. However, the factors from the 1994 amendments became effective July 14, 1994 and would be applicable to this defendant if the facts of the case so warranted, since the murder of Sandra Lee Long occurred September 2, 1994.

They are:

Finally, in 1995, the General Assembly expanded the list of statutory aggravating circumstances to twenty-two by adding section (v) dealing with "hate crime" offenses. [FN4] Since this amendment was not effective until July 6, 1995, and because the Court believes the defendant has no standing to object to this amendment, the Court finds it inapplicable to the case at bar. Therefore, the Court will not consider the constitutionality of this amendment or its effect on the overall constitutionality of the statute. As a result, the Court's first task is to review the constitutionality of the 1994 amendments.

FN4. Section (v) states the following: The murder was committed for the purpose of interfering with the victim's free exercise or enjoyment of any right, privilege or immunity protected by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, or because the victim has exercised or enjoyed said rights, or because of the victim's race, religion, color, disability, national origin or ancestry. 70 Del. Laws Ch. 137 (codified at 11 Del.C. § 4209(e)(1)(v)).

The principle that statutory aggravating circumstances must genuinely narrow the class of persons eligible for the death penalty stems from the concern expressed by the United States Supreme Court in Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238, 92 S.Ct. 2726, 33 L.Ed.2d 346 (1972) that "the worst criminals or the criminals who commit the worst crimes are selected for this punishment." Id. at 294, 92 S.Ct. at 2754 (Brennan, J., concurring). Later, in Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153, 96 S.Ct. 2909, 49 L.Ed.2d 859 (1976), the United States Supreme Court expounded upon "the need for legislative criteria to limit the death penalty to certain crimes." Zant v. Stephens, 462 U.S. 862, 877- 78 n. 15, 103 S.Ct. 2733, 2742 n. 15, 77 L.Ed.2d 235 (1983). "The decision that capital punishment may be the appropriate sanction in extreme cases is an expression of the community's belief that certain crimes are themselves so grievous an affront to humanity that the only adequate response may be the penalty of death." Gregg, 428 U.S. at 184, 96 S.Ct. at 2930. This community expression is legislatively reflected by the establishment of statutory aggravating circumstances that would justify the imposition of death if found to exist.

It is thus required before capital punishment may be considered, that the defendant first be convicted of the crime of Murder First Degree, and that at least one of the statutory aggravating circumstances established by the General Assembly be applicable to the defendant's actions. This does not mean, however, that the inquiry comes to an end by the General Assembly's decision to enact certain statutory aggravating circumstances. To avoid imposing the death penalty in a "wanton or freakish manner," the discretion as to whether to impose the death penalty "must be suitably directed and limited so as to minimize the risk of wholly arbitrary and capricious action." Lewis v. Jeffers, 497 U.S. 764, 774, 110 S.Ct. 3092, 3099, 111 L.Ed.2d 606 (1990) (quoting Gregg, supra, 428 U.S. at 189, 96 S.Ct. at 2932). It is the task of the General Assembly to establish aggravating circumstances to "channel the sentencer's discretion by 'clear and objective standards' that provide specific and detailed guidance." Id. (quoting Godfrey v. Georgia, 446 U.S. 420, 428, 100 S.Ct. 1759, 1764-65, 64 L.Ed.2d 398 (1980)).

The United States Supreme Court recently reiterated the two requirements that must be established for an aggravating circumstance to be found constitutional in Tuilaepa v. California, 512 U.S. 967, 114 S.Ct. 2630, 129 L.Ed.2d 750 (1994).

First, the circumstance may not apply to every defendant convicted of a murder; it must apply only to a subclass of defendants convicted of murder. See Arave v. Creech, 507 U.S. 463, 473, 113 S.Ct. 1534, 1542, 123 L.Ed.2d 188 (1993) ("If the sentencer fairly could conclude that an aggravating circumstance applies to every defendant eligible for the death penalty, the circumstance is constitutionally infirm"). Second, the aggravating circumstance may not be unconstitutionally vague. Godfrey v. Georgia, 446 U.S. 420, 428, 100 S.Ct. 1759, 1764-1765, 64 L.Ed.2d 398 (1980); see Arave, supra, 507 U.S., at 471, 113 S.Ct., at 1541 (court " 'must first determine whether the statutory language defining the circumstance is itself too vague to provide any guidance to the sentencer' ") (quoting Walton v. Arizona, 497 U.S. 639, 654, 110 S.Ct. 3047, 3057-58, 111 L.Ed.2d 511 (1990)).

Tuilaepa, 512 U.S. at 972, 114 S.Ct. at 2635.

Our own Supreme Court has also articulated the constitutional criteria by which statutory aggravating circumstances must be judged. In State v. White, Del.Supr., 395 A.2d 1082 (1978), the Court was faced with several challenges to the 1977 death penalty statute, including a constitutional challenge to two statutory aggravating circumstances. There, the defendant alleged that the provisions of former sections (r) and (s) were unconstitutionally vague due to the fact that the terms "elderly" and "defenseless" were not legislatively defined. The Court agreed and held "the constitutionality of a death penalty statute rests upon the premise that the sentencing authority's discretion in imposing the death penalty is guided and channeled by clear and objective statutory standards." White, 395 A.2d at 1090. In striking down those provisions as unconstitutionally vague, the Court quoted from the Supreme Court of Georgia: "[w]henever a statute leaves too much room for personal whim and subjective decision-making without a readily ascertainable standard or minimal, objective guidelines for its application, it cannot withstand constitutional scrutiny." Id. (quoting Arnold v. State, 236 Ga. 534, 224 S.E.2d 386, 391 (1976)). The danger, said the Court, is that "by the use of such vague terminology, there is substantial risk that sentencing authorities will inflict the death penalty in an arbitrary and diversified manner." Id. at 1091.

In State v. Chaplin, Del.Super., 433 A.2d 327 (1981), aff'd, Del.Supr., 433 A.2d 325 (1981), the constitutionality of another statutory aggravating circumstance was examined. Former section (n) provided that "the murder was outrageously or wantonly vile, horrible or inhuman." Relying on the United States Supreme Court case of Godfrey v. Georgia, 446 U.S. 420, 100 S.Ct. 1759, 64 L.Ed.2d 398 (1980), the Court found that the language of this factor was unconstitutional because "[t]here is nothing in these few words standing alone that implies any inherent restraint on the arbitrary and capricious infliction of the death sentence." Chaplin, 433 A.2d at 329. [FN6]

FN6. Former section (e)(1)(n) was later amended to correct the infirmity by adding more specific language to the Code. The current version reads as follows: "The murder was outrageously or wantonly vile, horrible, or inhuman in that it involved torture, depravity of mind, use of an explosive devise or poison or the defendant used such means on the victim prior to murdering the victim." 11 Del.C. § 4209(e)(1)(l).

After carefully reviewing the statutory aggravating circumstances added in 1994, the Court finds that they are constitutionally permissible under the "clear and objective" standard of White, Chaplin, and the United States Supreme Court cases discussed above. Factor (e)(1)(s) clearly states that this statutory aggravating circumstance applies to cases where the victim is a child of age 14 or younger, and the defendant is at least four years older than the victim. See State v. Demby, Del.Supr., 672 A.2d 59 (1996) (interpreting section (s) and holding that the victim's age is an aggravating factor when the victim is under the age of 15). This aggravating factor reflects an appropriate legislative intent to harshly punish those who pray on the youth of our community. This section is clearly written, particularly now that the age issue was resolved in Demby, and is easily applied in a consistent and non-arbitrary fashion.

Factor (e)(1)(t) addresses the killing of informants in retaliation for providing information to the law enforcement community. The Court considers this aggravating circumstance to be a suitable response to violent and egregious conduct that undermines the foundation of the criminal justice system. Again, this factor is clearly defined and can be applied in a consistent and non-arbitrary manner.

Finally, factor (e)(1)(u) addresses the murder committed after substantial planning and aforethought. It is difficult to envision a more appropriate aggravating factor than the killing of another human being that is the result of a carefully planned, contemplated and executed strategy. While its application is highly dependent on the facts of each case, and by its nature it may be one of the more difficult factors to establish, this does not mean that the jury and court would be unable to carefully and consistently apply this aggravating factor in an objective manner. Again, the Court finds this aggravating factor to be clear, precise, and capable of being applied in a non-arbitrary fashion.

All of these aggravating factors present separate circumstances which may be applied in a "clear and objective" manner to a unique subclass of defendants as required under the law. Further, they are not written in a vague manner that would lead to the arbitrary or indiscriminate imposition of the death penalty. Therefore, the Court is not convinced that the statutory aggravating circumstances discussed above are inconsistent with the constitutional mandate set forth in Gregg, White, and their progeny; nor is the Court persuaded that the most recent amendments to the death penalty statute render it constitutionally infirm under either state or federal grounds. Accordingly, the Court finds the 1994 amendments to 11 Del.C. § 4209(e) constitutional.

While the Court has found each of the aggravating circumstances discussed above to be constitutional standing alone, it must now address the defendant's argument that the State has inappropriately stacked the statutory aggravating circumstances "so as to virtually eliminate the likelihood of any Murder First Degree defendant not being eligible for a death sentence." In other words, is there a point where the cumulative effect of the number of statutory aggravating circumstances renders the statute as a whole unconstitutional?

While the United States Supreme Court has not specifically examined this issue, the defendant's argument has some support in the language of the cases addressing other death penalty matters. For example, in Spaziano v. Florida, 468 U.S. 447, 104 S.Ct. 3154, 82 L.Ed.2d 340 (1984), the Court examined a defendant's challenge to the Florida statute which allows a judge to impose the death penalty even when the jury recommends a life sentence. There the Court stated, "[i]f a State has determined that death should be an available penalty for certain crimes, then it must administer that penalty in a way that can rationally distinguish between those individuals for whom death is an appropriate sanction and those for whom it is not." Id. at 460, 104 S.Ct. at 3162. In Zant v. Stephens, 462 U.S. 862, 103 S.Ct. 2733, 77 L.Ed.2d 235 (1983), the Court considered the sentencing implications for a defendant who was sentenced to death based on three aggravating circumstances, where one of those aggravators was subsequently held to be unconstitutional. Again, the Court emphasized, "an aggravating circumstance must genuinely narrow the class of persons eligible for the death penalty and must reasonably justify the imposition of a more severe sentence on the defendant compared to others found guilty of murder." Id. at 877, 103 S.Ct. at 2742.

Given the logic of the defendant's argument, a search was conducted of the 38 states which have the death penalty to see how Delaware compared in the number of aggravating circumstances in effect in each state. This search revealed that Delaware does have more statutory aggravating circumstances in sheer number than any other state. Those closest to Delaware include California with 19; Alabama with 18; Missouri, Pennsylvania and Utah with 17; and Illinois and Indiana with 15. Of the states listed above, California, Alabama and Missouri's statutes have reached the United States Supreme Court and been upheld. See Tuilaepa, supra; Harris v. Alabama, 513 U.S. 504, 115 S.Ct. 1031, 130 L.Ed.2d 1004 (1995); Bullington v. Missouri, 451 U.S. 430, 101 S.Ct. 1852, 68 L.Ed.2d 270 (1981). However, a pure mathematical calculation as to the number of aggravating circumstances can be misleading. A more thorough review reveals that the Delaware statute separately lists certain aggravating circumstances that are incorporated together as one in other states. Additionally, some factors found as aggravators in other states have not been included in the Delaware statute. At best, this information leads one to reasonably conclude that Delaware is not out of line, nor has it reached the point where the defendant's argument would perhaps have merit.

While the Court does not dispute that at first blush the defendant's argument appears logical, it is disturbed by the prospect of how one determines the point at which the number of aggravating circumstances causes the death penalty statute to be generally unconstitutional. Is the Court to engage in some mathematical calculation as to who might be covered by the statute and who is not; and if so, what would be reasonable and logical factors to include in the formula? Can the Court arbitrarily declare that fifty aggravating circumstances is too many but forty-nine is permissible? Even assuming one could ever create a tool that would measure the percentage of defendants eligible for capital punishment, where is the dividing line of constitutionality and who makes that decision?

The Court believes these questions demonstrate why the only appropriate, logical, practical and reasonable means to determine the constitutionality of aggravating circumstances in a death penalty statute is to only consider the parts of the statute applicable to the defendant and to the specific facts of each case, and not the statute relative to the universe of potential defendants. When one considers that seldom is a defendant ever alleged to be death-eligible because of more than a few aggravating circumstances, the logic of this limitation becomes apparent. In other words, is it reasonable for a defendant who has become eligible for the death penalty because he qualifies under one aggravating circumstance to become ineligible because of a number of other factors completely irrelevant and unrelated to his actions? The Court believes that such a result is not mandated by the Constitution nor would it serve the interest of assuring that justice has been performed.

In this case, the State only sought to prove a single statutory aggravating circumstance in the penalty phase. That is, that "the murder was committed while the defendant was engaged in the commission of, or attempt to commit, or flight after committing or attempting to commit any degree of rape, unlawful sexual intercourse, arson, kidnapping, robbery, sodomy or burglary." 11 Del.C. § 4209(e)(1)(j). This aggravating factor has previously been upheld as constitutional, and the Court's inquiry has been fulfilled.[ FN7]

FN7. The Court also notes that this case does not reflect any action by the prosecution to "stack" aggravating circumstances in an attempt to inappropriately influence either the jury or the Court. In fact, the State exhibited wise and prudent prosecutorial discretion in only arguing for one aggravating circumstance when the possibility existed for several others to also apply.

The fact that the legislature has set forth twenty-two specific statutory aggravating circumstances manifests society's concern that certain actions are so heinous as to be worthy of capital punishment. The Court believes that in promulgating this legislation, the General Assembly has done so with due regard for the gravity of the subject matter. Therefore, the defendant's challenge to the death penalty statute as articulated above is DENIED.

The defendant next contests the constitutionality of the death penalty statute based on the alleged failure of the statute to provide for any consideration of mercy. The identical issue was squarely addressed by this Court in State v. Ferguson, Del.Super., Cr. A. No. IN91-10-0576, Gebelein, J., 1995 WL 413269 (Apr. 7, 1995) (Mem.Op.) (discussing the merits of the argument despite the fact that it was procedurally barred under Rule 61). This Court is confident that the legislature has gone to great pains to draft a statute that complies with the constitutional requirements as discussed above. In dismissing Ferguson's argument, Judge Gebelein pointed out that those requirements include the mandate that the death penalty not be imposed with "unfettered sentencing discretion," nor must it be "meted out arbitrarily and capriciously." Id. (quoting Dougan v. State, Fla.Supr., 595 So.2d 1, 4 (1992)).

In guiding the jury's sentencing deliberations and recommendation in the penalty phase of a capital case, the Court is compelled to give an instruction that precludes the consideration of sentiment, conjecture, sympathy, passion, prejudice, or public feeling as both irrelevant and improper. See California v. Brown, 479 U.S. 538, 107 S.Ct. 837, 93 L.Ed.2d 934 (1987). Despite the significance of that instruction, the defendant is given the unlimited opportunity to present other valid mitigating evidence "as to any matter that the Court deems relevant and admissible to the penalty to be imposed." 11 Del.C. § 4209(c). That evidence frequently includes poignant and moving testimony from the defendant's family as to the contribution and value which a defendant may continue to have for his family; medical testimony regarding any psychological and cognitive defects with which a defendant may be afflicted; [FN8] and alcohol and substance abuse by a defendant. [FN9] These are just a few examples of commonly accepted mitigating circumstances which a jury may properly consider.

FN8. For cases acknowledging family background as a valid mitigating circumstance see Eddings v. Oklahoma, 455 U.S. 104, 102 S.Ct. 869, 71 L.Ed.2d 1 (1982) and Hitchcock v. Dugger, 481 U.S. 393, 107 S.Ct. 1821, 95 L.Ed.2d 347 (1987).

FN9. See Fead v. State, Fla.Supr., 512 So.2d 176 (1987) (recognizing alcohol abuse as a valid mitigating circumstance).

In addition to the guidance provided by our own legislature and judiciary, the United States Supreme Court has also frowned upon the consideration of such sentiment by jurors in death penalty proceedings. In Saffle v. Parks, 494 U.S. 484, 110 S.Ct. 1257, 108 L.Ed.2d 415 (1990), the Court held:

It is no doubt constitutionally permissible, if not constitutionally required, for the State to insist that "the individualized assessment of the appropriateness of the death penalty [be] a moral inquiry into the culpability of the defendant, and not an emotional response to the mitigating evidence."... It would be very difficult to reconcile a rule allowing the fate of a defendant to turn on the vagaries of particular jurors' emotional sensitivities with our longstanding recognition that, above all, capital sentencing must be reliable, accurate, and nonarbitrary. At the very least, nothing ... prevents the State from attempting to ensure reliability and nonarbitrariness by requiring that the jury consider and give effect to the defendant's mitigating evidence in the form of a "reasoned moral response," rather than an emotional one. The State must not cut off full and fair consideration of mitigating evidence; but it need not grant the jury the choice to make the sentencing decision according to its own whims or caprice.

Id. at 492-93, 110 S.Ct. at 1262-63 (citations omitted). To the extent that the jury desires to express its compassion for the defendant, it does so in its balancing of the aggravating and mitigating circumstances, and in its ultimate recommendation for a life sentence. Nothing more is required in order to achieve the defendant's goal of persuading the jury that it should be merciful to the defendant and reject a sentence of death. Therefore, the defendant's final challenge to the death penalty statute is DENIED.

III. Conclusion - For the foregoing reasons the defendant's Motion to Strike the Death Penalty as a potential punishment in this case is hereby DENIED.

IT IS SO ORDERED.

Steckel v. Carroll, Not Reported in F.Supp.2d, 2004 WL 825302 (Del. 2004) (Habeas).

FARNAN, J.

BACKGROUND

In September 1994, Petitioner was indicted by a grand jury on multiple counts of first degree murder and additional related offenses arising from the September 2, 1994 killing of Sandra Long. In October 1996, Petitioner, represented by Jerome M. Capone, Esquire and Joseph A. Gabay, Esquire, was tried before a jury. The evidence adduced at trial demonstrated that Petitioner met Ms. Long approximately one week before the murder. Petitioner stayed occasionally with Ms. Long's neighbors, Tammy and Robert Johnson. Petitioner witnessed a verbal dispute between Ms. Long and Mrs. Johnson, after which he commented, "[I] should rape the bitch." (Steckel I, A35-A38, B59-B61). [FN1]

FN1. The designations "A" and "B" refer to the appendices to the opening and answering briefs filed by Petitioner and the State, respectively, in Steckel v. State, 711 A.2d 5 (Del.1998) (Nos. 27 & 45, 1997) (Steckel I ) and Steckel v. State, 795 A.2d 651 (Del.2002) (No. 473, 2001) (Steckel III ).

On the day of Ms. Long's murder, Petitioner gained access to her Driftwood Club Apartment by asking her if he could use her telephone. (Steckel I, B3). Once inside, Petitioner pretended to use the phone, but unplugged it from the wall. (Steckel I, B64-B65). Petitioner then demanded sexual favors from Ms. Long, and she refused. Petitioner beat Ms. Long and threw her onto a couch pinning her beneath him. (Steckel I, B15-B18). During the struggle, Ms. Long bit Petitioner's finger causing it to bleed. (Steckel I, B6). Petitioner then attempted to strangle Ms. Long with a pair of nylons which he brought with him. When his attempts to strangle her with the nylons failed, Petitioner grabbed a sock and continued to strangle her with the sock. (Steckel I, B8, B79). Ms. Long eventually fell unconscious, and while unconscious Petitioner sexually assaulted her, first using a screw-driver he brought with him, and then by raping her anally. (Steckel I, B1-B26, B80).

Ms. Long remained unconscious while Petitioner dragged her to the bedroom and set the bed on fire using a black lighter which he had brought with him. Petitioner also set fire to the curtain in Ms. Long's bathroom. (Steckel I, B1-B26, B62-B66).