Executed February 17, 2011 10:34 a.m. by Lethal Injection in Ohio

7th murderer executed in U.S. in 2011

1241st murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Ohio in 2011

42nd murderer executed in Ohio since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(7) |

Frank G. Spisak Jr. W / M / 30 - 59 |

Rev. Horace T. Rickerson B / M / 57 Timothy Sheehan W / M / 50 Brian Warford B / M / 17 |

08-27-82 08-30-82 |

Spisak was arrested in September for firing his gun out of his apartment window, but was released on bail. Police then received an anonymous phone call telling them to check the gun, a .22-caliber pistol. The gun was linked to the Warford murder and Spisak admitted to the other shootings. At trial Spisak pled insanity, saying that the one-man war was launched under direct orders from God. Tim Sheehan's son Brendan Sheehan grew up to become a prosecutor and was seated as a trial court judge in Cuyahoga County in 2009. His father was murdered on Brendan's 15th birthday.

Citations:

State v. Spisak, Not Reported in N.E.2d, 1984 WL 13992 (Ohio App. 1984). (Direct Appeal)

Smith v. Spisak, 130 S.Ct. 676, 130 S.Ct. 676, 175 L.Ed.2d 595 (2010). (Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

Spaghetti with tomato sauce, a salad, chocolate cake and coffee.

Final Words:

For his final statement, Spisak recited Biblical verses from the book of Revelations. In German, he read the first seven verses of the 21st chapter of Revelations. The passage deals with the end of the world, the return of Christ and the elevation of everyone to heaven. Interestingly, Spisak's final statement included the first seven verses of the 21st chapter of Revelations, but did not include the eighth verse which mentions "the abominable, and murderers, ... and all liars, shall have their part in the lake which burneth with fire and brimstone." At the end of his statement Spisak said, "Heil Herr," which is roughly translated to English as "Praise God."

Revelation 21 - A New Heaven and a New Earth - 1 Then I saw "a new heaven and a new earth," for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and there was no longer any sea. 2 I saw the Holy City, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride beautifully dressed for her husband. 3 And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, "Look! God's dwelling place is now among the people, and he will dwell with them. They will be his people, and God himself will be with them and be their God. 4 'He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death' or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away." 5 He who was seated on the throne said, "I am making everything new!" Then he said, "Write this down, for these words are trustworthy and true." 6 He said to me: "It is done. I am the Alpha and the Omega, the Beginning and the End. To the thirsty I will give water without cost from the spring of the water of life. 7 Those who are victorious will inherit all this, and I will be their God and they will be my children. (New International Version, 2010)

Internet Sources:

Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction

Name: Frank Spisak

Number: A175-472

Date of Birth: 06/06/1951

Gender: Male Race: White

Admission Date: 06/16/1993

County of Conviction: Cuyahoga

Convictions: AGG MURDER, ORC: 2903.01; ATT MURDER, AGG ROBBERY (2 COUNTS), ATT MURDER

Executed: 02/17/2011

On February 17, 2011, Frank Spisak was executed for the 1982 aggravated murders of Reverend Horace Rickerson, Timothy Sheehan, and Brian Warford.

Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction (Clemency Report)

Inmate#: OSP #A175-472

Inmate: Frank W. Spisak Jr.

DOB: June 6, 1951

County of Conviction: Cuyahoga County

Date of Offense: 02-01-1993

Case Number: CR181411, CR176651B

Date of Sentencing: February 1, 1982, August 27, 1982, August 30, 1982

Presiding Judge: James J. Sweeney

Prosecuting Attorney: Doinald Nugent

Institution: Ohio State Penetentiary

Convictions: AGG MURDER, ORC: 2903.01; ATT MURDER (7-25 YEARS), AGG ROBBERY (2 COUNTS) (7-25 YEARS)

"Ohio executes murderer who 'hunted' blacks," by Alan Johnson. (Thursday, February 17, 2011 08:51 AM)

LUCASVILLE, Ohio -- When Frank Spisak was going on "hunting parties" targeting blacks in Cleveland, Ronald Reagan was president, a stamp cost 20 cents and the Cincinnati Bengals played in the Super Bowl XVI. More than 10,000 days later, Spisak, 59, a triple murderer, was executed today at the Southern Ohio Correctional Facility near Lucasville. The time of death was 10:34 a.m. The 27 years between the murders on the Cleveland State University campus in 1982 and Spisak's final punishment was the longest gap in Ohio's 42 executions since 1999.

As Spisak's IV's were being hooked up, Jeffrey Duke, the brother of one of Spisak's victims, said: "They ought to hook him up to a generator. If I could get to him, that's what I'd do. A person like him, thinking he could go around killing people because he didn't like the color of their skin or their religion. I'm sorry, that's just the way I feel."

Before the lethal chemical began flowing, Spisak recited -- in German -- the first seven verses from the 21st chapter of from the Book of Revelation. He had trouble reading the passage, which had to be moved closer to him. He apparently did not read the eighth verse, which says: "But the cowardly, the unbelieving, the vile, the murderers, the sexually immoral, those who practice magic arts, the idolaters and all liars -- they will be consigned to the fiery lake of burning sulfur. This is the second death."

In a written statement handed out after the execution, Cora Warford, the mother of the youngest victim, said: "In memory of my baby boy, Brian Warford, I can finally say justice has been served. If one can this brings closure, I can say it is peace of mind for me and my family."

Among the witnesses was John Hardaway, who survived despite being shot seven times by Spisak. Spisak, who blamed mental illness for his hatred of gays, blacks and Jews, was the last person in Ohio to be lethally injected with sodium thiopental. The state will no longer use the drug because the sole U.S. manufacturer stopped making it. Beginning with the execution of Johnnie Baston on March 10, the state will use pentobarbital, a fast-acting barbiturate that is more readily available.

Between February and August of 1982, Spisak shot and killed the Rev. Horace Rickerson, 57; Timothy Sheehan, 50; and Brian Warford, 18. He said he was going on "hunting parties" and hoped to spark a race war in Cleveland. He shot Hardaway and shot at but missed a woman on the urban university campus.

Spisak was an admirer of Nazi leader Adolf Hitler. He carried a copy of Mein Kampf and grew a Hitler mustache during his 1983 trial.

Spisak suffered from bipolar disorder and had a lifelong struggle over his sexual identity. He referred to himself as Frances and in 1999 sued the state for "keeping her locked up on Death Row in an all-male prison environment where she cannot receive appropriate hormonal and surgical treatment for her physical and mental defects."

Spisak lost all his appeals, including the last one to the U.S. Supreme Court in which he argued that he should not be executed because of Ohio Supreme Court Justice Paul E. Pfeiffer's comments about the unevenness of the death penalty's application.

Gov. John Kasich agreed with the Ohio Parole Board's unanimous recommendation against granting clemency for Spisak.

Spisak's "last meal" yesterday consisted of spaghetti with tomato sauce, a salad, chocolate cake and coffee.

"Frank Spisak executed for 1982 slayings of three people at Cleveland State University," by Joe Guillen. (Friday, February 18, 2011, 4:23 AM)

LUCASVILLE, Ohio - Frank Spisak, a self-proclaimed Nazi who killed three people at Cleveland State University nearly 30 years ago in a racism-fueled rampage, was executed by injection Thursday morning.

Spisak expressed no remorse for his crimes when given a chance to say his final words. Instead, he read a handwritten note -- in German -- with verses one through seven of Chapter 21 in the Bible's Book of Revelations.

Spisak, who wore a Hitler-style mustache and saluted the Nazi leader during his 1983 trial, struggled at times to read the note clearly, complaining that the words were blurry. "Heil herr," Spisak concluded.

He was pronounced dead at the Southern Ohio Correctional Facility at 10:34 a.m. Spisak, 59, was the 42nd Ohio inmate executed since 1999 and the first executed this year. He spent more than 27 years on death row.

Over the course of several months in 1982, Spisak, driven by his Nazi beliefs, killed three people at CSU - the Rev. Horace Rickerson; CSU student Brian Warford; and Timothy Sheehan, an assistant superintendent for buildings and grounds at the university. Spisak also shot John Hardaway, a factory worker, and Coletta Dartt, a CSU employee. Spisak would go on "hunting parties" and targeted Rickerson, Warford and Hardaway because they were black, according to his parole records.

Relatives of Sheehan and Warford witnessed the execution, along with Hardaway, U.S. District Judge Don Nugent, who prosecuted Spisak, and Jim Oliver, a retired law enforcement officer who investigated the shootings.

Jeffrey Duke, Warford's brother, became upset as he waited for Spisak to enter the execution chamber. A monitor in the witness viewing area -- separated from the execution chamber only by a window -- showed medical staff in a nearby room preparing Spisak's veins to receive the injection of sodium thiopental. Duke said he would prefer that Spisak be connected to a "generator" or "batteries." "A person like that, thinking he could just kill people because he didn't like the color of their skin or religion," Duke said.

Spisak -- clean-shaven with dark colored boots on his feet -- then walked into the chamber and was strapped to a bed. He looked up and waved to his lawyers, Michael Benza and Alan Rossman, and Bill Kimberlin, a Lorain Community College psychology professor who befriended Spisak while researching death row inmates.

Warden Donald Morgan then put a microphone to Spisak's face and asked him if he would like to say any last words. "Yes, I would," Spisak said. "I would like to read from the Holy Bible."

A prison staffer held up Spisak's handwritten note as he recited the Bible verses in German. A spokesman for the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction provided reporters with copies of the note before the execution. But Spisak struggled to read his own words, drawing some amused chuckles from the victim's relatives. "It's too far away," Spisak said. "I can't read it. It's blurry."

"Speak English, you fool," said Eric Barnes, another brother of Warford's. Barnes held a piece of paper with two pictures of his brother, one as a baby and the other as a young man. Warford was 17 when Spisak shot him.

As Spisak stammered through his statement, Cathy Sheehan Daly, Timothy Sheehan's daughter, leaned over to Duke and said, "He's making it up." Spisak finished his five-minute statement and the injection began to flow. He let out a few deep inhalations, making a snoring sound. He was pronounced dead 10 minutes later.

Spisak claimed he no longer was sympathetic to the Nazi movement in an interview with the Ohio Parole Board on Jan. 4, yet he told the board he was reading a biography of Hitler at the time. Spisak claimed to be a more tolerant person. The relatives of victims and others who witnessed the execution declined to be interviewed afterward.

In a statement, the Sheehan family said they will continue to celebrate Timothy Sheehan's life. Brendan Sheehan, Timothy's son and now a Cuyahoga County Common Pleas judge, and other family members who did not witness the execution were at a nearby church Thursday morning. "Today, we chose to celebrate the life of husband and father, Timothy Sheehan, not the death of Frank Spisak," the statement said. "We are grateful that the justice system has worked and appreciate those in the criminal justice system whose diligent efforts have helped bring this matter to a final resolution."

Cora Warford, Warford's mother, said in a statement: "In memory of my baby boy Brian Warford, I can finally say justice has been served. If one can say this brings closure, I can say it is peace of mind for me and my family. Spisak will have to stand before a higher court one day as we all will and may God have mercy on his soul."

Spisak's lawyers had tried to delay the execution. They pleaded with the Ohio Parole Board and Gov. John Kasich to spare his life because he is mentally ill with a bipolar disorder. But the board decided, and Kasich agreed, the nature of Spisak's crimes outweighed concerns about his mental health. An appeal filed with the U.S. Supreme Court earlier this week also was denied. Last year, the Supreme Court upheld his death sentence, reversing a previous ruling that Spisak's sentencing hearing was unconstitutional.

Before his conviction, Spisak experimented with cross-dressing and was confused about his gender, preferring to be called Frances Anne. Numerous mental-health professionals evaluated Spisak, who pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity, before his trial. He was deemed competent when he killed.

After the execution, Spisak's lawyers lamented the state's killing of a mentally ill man. "We know what the media is going to say about Frances Spisak. But the truth is Frances was seriously mentally ill and committed the crimes because of this mental illness, not because of hate," Benza and Rossman said in a statement. "Maybe some day we will see executions of mentally ill people for what it is: barbaric."

Judge Sheehan, reached after the execution, said Spisak knew what he was doing when he killed his father. He said Spisak's final words in German only cemented that belief. "He showed his true colors in the execution," Sheehan said. Spisak's will be Ohio's last execution using the drug sodium thiopental. The drug's maker objected to its use in executions and said it would stop production, so Ohio will be the first state with a one-drug injection process using pentobarbital, a sedative used during heart surgery.

"As Nazi sympathizer Frank Spisak prepares for execution, a surviving victim recalls his attack nearly 30 years ago," by Joe Guillen. (Wednesday, February 16, 2011, 11:11 AM)

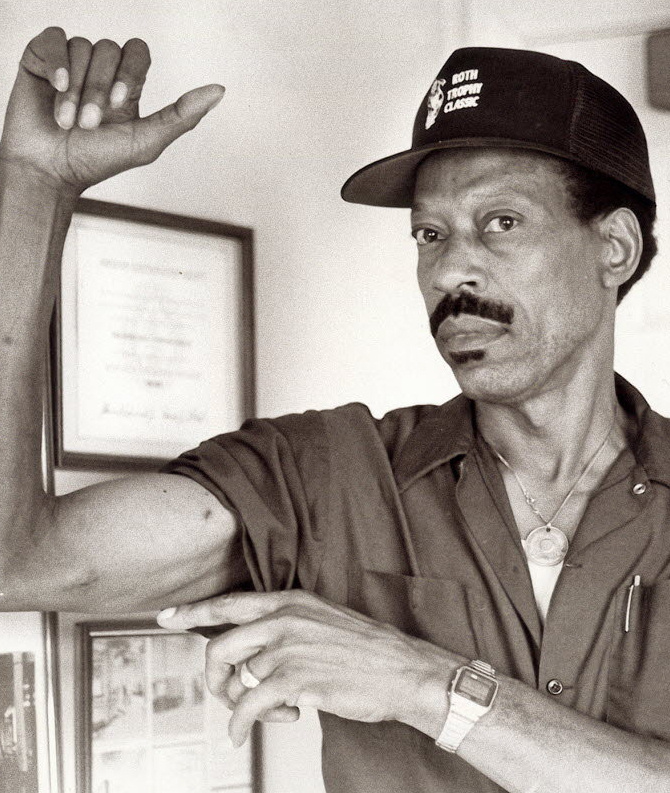

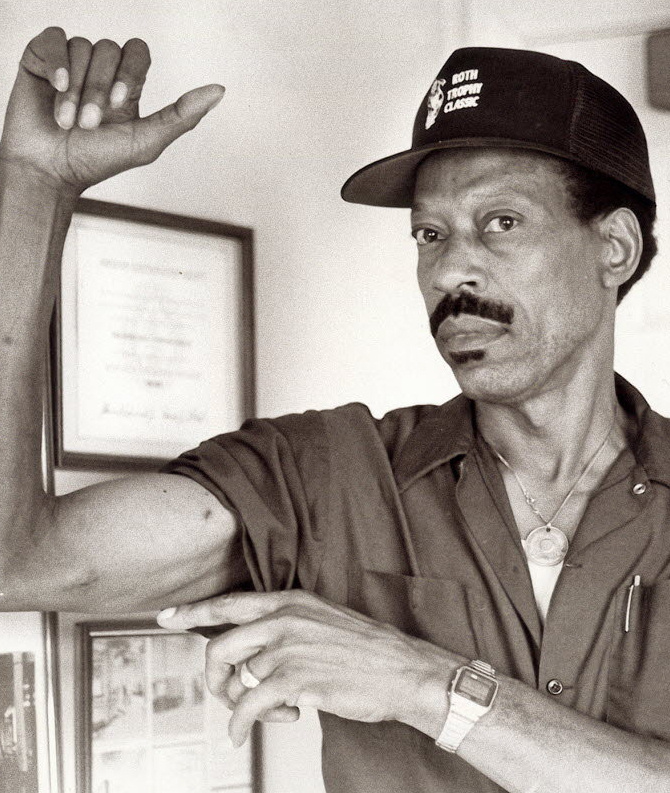

COLUMBUS, Ohio — Nearly 30 years ago, John Hardaway was heading home from work when Frank Spisak, a self-proclaimed modern-day Nazi, ambushed him at a rapid-transit station and shot him seven times in his arm and right torso, leaving Hardaway for dead on the platform. Hardaway survived, but the shooting left him with chronic pain in his right hand and the vivid memory of an attack that characterized the senseless and brutal nature of Spisak's 1982 killing spree on Cleveland State University's campus.

Spisak is set to die Thursday for his rampage, which claimed the lives of three people at CSU -- the Rev. Horace Rickerson; CSU student Brian Warford; and Timothy Sheehan, CSU's assistant superintendent for buildings and grounds. Prosecutors said he targeted Hardaway, whom Spisak had never met, Rickerson and Warford because they were black. Sheehan was a potential witness in Rickerson's killing, prosecutors said.

"I can still see the night he was shooting me," Hardaway, 83, said in a recent interview at his one-bedroom apartment on Cleveland's East Side. "He was squatting down, pulling that trigger. That will never go away. It ain't as bad as it was, but it hits me hard sometimes. Why would he do a person like that?"

Spisak's execution, after he spent more than 27 years on death row, will be the first of Gov. John Kasich's term. Spisak, 59, is among the longest-serving Ohio inmates on death row.

But recent comments from an Ohio Supreme Court justice have given new life to Spisak's attempts to avoid execution. Justice Paul Pfeifer, a Republican, called this year for an end to the death penalty law because he said it is not being applied as originally intended. Based on these comments, Spisak's lawyers have asked to delay the execution until the constitutionality of Ohio's death penalty is decided in court. The 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals denied the request on Tuesday. Alan Rossman, Spisak's federal public defender, said Tuesday evening that he intends to file the same request with the U.S. Supreme Court.

Despite the last-ditch attempt to delay the execution, Hardaway said he is relieved Spisak is headed for the execution chamber at the Southern Ohio Correctional Facility in Lucasville. He feared Spisak would outlive him as the appeals process carried on and on. "I'll go down on my knees, on the side of my bed every night, to pray and see if I would be able to live," Hardaway said. "I didn't know if I'd be living this long after all that happened."

The U.S. Supreme Court denied what was thought to be Spisak's final legal appeal in January 2010. Earlier this year, Spisak's lawyers asked the Ohio Parole Board and Kasich to spare their client's life, saying he is severely mentally ill with a bipolar disorder. The Parole Board was not convinced the mental illness outweighed the nature of his crimes. The board unanimously recommended that Kasich, a Republican, deny Spisak's clemency request. Last week, Kasich followed the recommendation.

"Spisak killed three people, tried to kill at least one other and shot a fifth in his admitted plan to kill as many African-Americans as possible and start a race war in Cleveland," the board said in its report to Kasich. "A recommendation for mercy is not warranted in this case." Spisak said he committed the killings because he was a follower of Adolf Hitler and was in a war for survival "of the Aryan people," according to court records.

Numerous mental-health professionals evaluated Spisak, who pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity, before his 1983 trial. He was deemed competent when he killed. Aside from the violence he carried out, Spisak's life also was marked by socially bizarre behavior. He experimented with cross-dressing and was confused about his gender, preferring to be called Frances Anne. During his trial, he wore a Hitler-style mustache and saluted the Nazi leader in court. His lawyers still refer to him as Frances.

The lawyers, Rossman and Michael Benza, are among those scheduled to witness Spisak's death by injection. Other witnesses include Warford's brother and sister, Sheehan's daughter and Judge Donald Nugent, who prosecuted the case.

Cuyahoga County Common Pleas Judge Brendan Sheehan, whose legal career was inspired by his father's murder, said neither he nor his family would comment before Thursday's execution.

Hardaway said he would like to see Spisak die but does not have the means to travel to Lucasville. A former Georgia sharecropper who arrived in Cleveland at age 26, Hardaway was a factory worker at Production Finishing Co. on Cleveland's West Side the night he was shot.

It was about 11 p.m. when Hardaway walked up the transit station's stairs to catch his train. He had just cashed his paycheck, and about $40 fell to the ground as he was shot. Yet Spisak never said anything to him and didn't take the money, Hardaway said.

Hardaway was losing consciousness as he lay on the station's platform. A train operator soon found him and called for help. He was hospitalized for about a month, then returned to work. "He was shot seven times and was back a month later," said Jim Kelly, whose uncle supervised Hardaway. "He's a survivor. He got to see this guy's face while he was putting bullets through him and live through it."

In 1984, Hardaway sued Spisak and his accomplice, Ronald Reddish, who assisted Spisak before the shooting. Hardaway sought $1 million, citing emotional distress due to the attack. A judge granted a default judgment in Hardaway's favor, but Spisak and Reddish, who was convicted of the attempted murder of Hardaway, already had been convicted and had no assets to satisfy the judgment, Hardaway's lawyer, William White, said on Tuesday. "It's very frustrating -- you can't make a recovery," White said. "It's not unusual, it's just painful."

Hardaway expressed hope that the publicity surrounding Spisak's execution would somehow help him recover some of the money he asked for in the lawsuit. He said he needs a new hearing aid.

In some respects, Hardaway, who has two grown children, has come to terms with the assault at the rapid station. He no longer carries in his wallet the old newspaper clipping of Spisak's face, complete with Hitler mustache. He said putting the shooting behind him has allowed him to keep a level head. "White people was always good to me. Even in the country, in the South, there were some good ones and some bad ones," Hardaway said. "I never had no hard feelings toward white people at all, even after the shooting happened to me. I can't live with no hate."

Killed in shootings

• Tim Sheehan, 50, CSU employee

• The Rev. Horace Rickerson, 57, pastor

• Brian Warford, 17, CSU student

Survived shootings

• John Hardaway, factory worker

• Coletta Dartt, CSU employee

The Wacky World of Murder (Frank Spisak)

Frank G. Spisak Jr

VICTIMS : 3

"My aim was pretty good."

Frank Spisak's neighbours knew him as 'Frankie Ann Spisak.' He was a frizzy-haired transvestite who was looking forward to having a sex-change operation. They didn't know about Spisak's other side, a side that eventually took over his personality. Spisak eventually decided he no longer wanted to be a woman, but instead he wanted to be Hitler. He stopped wearing frocks and make-up, and changed to silly suits, slicked back hair and a toothbrush moustache. I'm not sure which gathered the most amount of laughs, but either way Spisak was serious about this new style.

In February 1982, Spisak launched his first "seek and destroy mission" in which he was attempting to "clean up the city". He walked onto the Cleveland State University and shot a black minister, Rev. Horace Rickerson, in a men's room. The Reverend died. Four months later he shot another black, John Hardaway, 55, only wounding this one.

During August Spisak struck three times. The first was Timothy Sheehan, 50, also at Cleveland State University. Sheehan was Caucasian but Spisak suspected that he may have been Jewish. He then gunned down 17-year-old Brian Warford, another black, at a bus stop near the campus. His next attack failed, narrowly missing another CSU employee.

Spisak was arrested in September for firing his gun out of his apartment window, but was released on bail. Police then received an anonymous phone call telling them to check the gun, a .22-caliber pistol. The gun was linked to the Warford murder and Spisak admitted to the others.

At the trial Spisak pled insanity, saying that the one-man war was launched under direct orders from God, his "immediate superior." He also blamed his transvestite period on the Jews saying that they "seized control of my mind when I wasn't looking". No one fell for this crap and Spisak was sentenced to death on August 10, 1983. "Even though this court may pronounce me guilty a thousand times, the higher court of our great Aryan warrior God pronounces me innocent. Heil Hitler!" - Or so Spisak thought after the trial.

After Spisak was sentenced to death the Social Nationalist Aryan Peoples Party stepped forward to claim him as a dues-paying lieutenant. The party's leader, ex-con Keith Gilbert, announced that Spisak was "acting under direct orders of the party" when he murdered the three victims in Cleveland. The orders, according to Gilbert: "Kill niggers until the last one is dead."

MY OPINION

This pathetic little man is a constant source of amusement for me. There is nothing funnier than a little transvestite Nazi that claims the Jews stole his mind while he wasn't looking. I love the little picture of him at the trial. He looks so cute with his little Hitler moustache. Anyway I don't think I can add anything to this sad story, so I'll leave it at that.

"Killer used his 1983 trial ‘to spout his Nazi beliefs’," by Tom Beyerlein. (February 14, 2011)

The first victim was the Rev. Horace T. Rickerson, found dead with seven gunshot wounds on a restroom floor at Cleveland State University on Feb. 1, 1982. Four months later, John Hardaway was waiting for a train when he saw a man walk onto the platform. The man shot Hardaway seven times, but he survived.

Coletta Dartt left a restroom stall at Cleveland State on Aug. 9, 1982, only to encounter a gunman, who ordered her back into the stall. She shoved him aside and ran away as he shot at her. Like Rickerson, Timothy Sheehan, a Cleveland State employee, was found dead on a campus restroom floor on Aug. 27. Three days later, CSU student Brian Warford was shot to death while waiting for a bus.

For months, the Cleveland State shootings horrified a city. The terror ended on Sept. 4, 1982, when Cleveland police responding to a report of a man firing shots out of a window arrested Frank G. Spisak Jr. At his apartment, police found newspaper clippings of the murders and Nazi and white-supremacist paraphernalia. Ballistics confirmed Spisak’s weapons were used in the shootings, and Sheehan’s pager was found in Spisak’s suitcase.

More than 28 years later, his appeals exhausted, Spisak is to die by lethal injection Thursday at the Lucasville prison.

“We’re happy the law is being followed,” said Brendan Sheehan, who was to celebrate his 15th birthday the day that Spisak killed his father. Brendan Sheehan went on to become an assistant Cuyahoga County prosecutor and is now a Cuyahoga County common pleas judge. He said his family is reserving further comment until after the execution.

Spisak unsuccessfully pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity. At his 1983 trial, he sported a Hitler mustache and, in the words of a clemency report, “used his trial to spout his Nazi beliefs, (and) blamed African-Americans, Jews and homosexuals for his own shortcomings in life.” Interviewed by the Ohio Parole Board on Jan. 4, Spisak said that at the time, he and a co-defendant “thought they would create a better world by eliminating the people that were not like them. He stated they thought it would be a safer world if it were all white.”

Spisak’s victims were black, except for Sheehan. Spisak told the parole board he killed Sheehan because he was a possible witness to Rickerson’s shooting and because Spisak thought he was “a Jewish professor perverting youth.” Sheehan was an Irish-born Catholic.

Spisak was sentenced to death after a jury convicted him of aggravated murder, attempted murder and aggravated robbery. During his 27 years in prison, he has chalked up a significant disciplinary record for infractions including spitting at a chaplain, performing oral sex on another inmate, indecent exposure, possession of intoxicating substances, and possession of weapons or contraband. He unsuccessfully has sued the state for a sex-change operation and now calls himself “Frances.”

In its clemency report, the parole board wasn’t moved by Spisak’s insanity claims, noting that he planned the killings and tried to avoid detection. The board’s unanimous decision: “Spisak’s contention that he is not the ‘worst of the worst’ is not well taken.”

But Spisak’s attorney, federal Public Defender Alan Rossman, who has requested a stay of execution in federal court, said it’s inhumane to put a mentally ill killer to death. “The failure of leadership to move the state of Ohio past the point where it is acceptable to execute the severely mentally ill is another opportunity lost,” Rossman said. “Maybe someday we will have a better alternative to dealing with mentally ill defendants than killing them.”

On February 1, 1982, the body of the Reverend Horace T. Rickerson was discovered by a fellow student on the floor of a restroom on the Cleveland State University campus. Horace had been shot seven times by an assailant from a distance of more than eighteen inches. Four spent bullet casings were recovered from the scene.

On the evening of June 4, 1982, John Hardaway was shot seven times while waiting for an RTA train at the West 117th Rapid Station in Cleveland. He observed a man walking up the platform steps and had turned away when the man opened fire on him. Hardaway survived the shooting, and was later able to identify his assailant as Frank G. Spisak, Jr. Three pellets and seven shell casings were recovered from the scene.

At approximately 5:00 p.m. on August 9, 1982, Coletta Dartt, an employee of Cleveland State University, left her office to use the restroom. Upon exiting the stall, she encountered Spisak, holding a gun, who ordered her back into the stall. Instead, Coletta shoved Spisak out of the way and ran down the hallway. Spisak shot at her, but missed. A pellet was later removed from a wall in the hallway. Coletta Dartt identified Spisak as her assailant.

On August 27, 1982, the body of Timothy Sheehan, an employee of Cleveland State University, was discovered in a restroom at the university by a security guard. The guard had been searching for Sheehan after his office reported that he had failed to answer his beeper page. Timothy had been shot four times, and two pellets were retrieved from the scene.

On the morning of August 30, 1982, the body of a young student, Brian Warford, was discovered in a bus shelter on the campus of Cleveland State University. Brian died from a single gunshot wound to the head, although five spent.22 caliber casings were recovered from the scene.

On September 4, 1982, Cleveland police answered a call that a man was firing shots from a window at 1367 East 53rd Street. The police were directed to Spisak's apartment and Spisak, after admitting he had fired one shot, invited the officers inside. A shotgun and a .22 caliber automatic pistol were observed in the room. Spisak made a suspicious move toward the couch but was stopped by one of the officers who discovered a loaded .38 caliber handgun and a two-shot derringer under the couch cushions. Spisak was arrested for possession of unregistered handguns and discharging firearms within city limits, but was later released on bond. The weapons, however, were confiscated.

Early the next day, an anonymous caller told police that the confiscated weapons had been used in the Cleveland State University shootings. Ballistics tests confirmed the tip. A warrant was obtained, and the police returned to Spisak's apartment, confiscating several items including newspaper clippings of the homicides and Nazi-White Power paraphernalia. Spisak was later arrested, hiding in the basement of a friend's house. During a brief search of Spisak's suitcase at the scene, police discovered the beeper pager belonging to Timothy Sheehan. Spisak later admitted to shooting Horace Rickerson for allegedly making a homosexual advance toward him; to killing Tim Sheehan as a possible witness to the Horace Rickerson shooting. The prosecution suggested it was the other way around, with Spisak making the overture and being rejected. Spisak also admitted to killing Brian Warford while on a "hunting party" looking for a black person to kill; and finally, to shooting at Coletta Dartt and to shooting John Hardaway. He also told police he had replaced the barrel of the .22 caliber handgun in order to conceal the murder weapon.

More information on the victims in this case can be found here. Tim Sheehan's son Brendan Sheehan grew up to become a prosecutor and was seated as a trial court judge in Cuyahoga County in 2009. His father was murdered on Brendan's 15th birthday.

Issue Date: May 2007 Issue

"The Long Goodbye"

All his victims were people who had changed courses in life, seeking a second chance. Now, 25 years after Frank Spisak’s serial murders terrified Cleveland State University, the death-row inmate gets a second chance at avoiding execution. In a courtroom, survivors and lawyers will return to 1982 and confront his crimes. A jury will decide his fate. John Hyduk

He attacked five people, killing three. He would have killed more if his aim were better. Their bodies and lives were torn by the tumbling slugs from a .22-caliber automatic.

Now, 25 years after Frank Spisak wandered the city streets with a pistol popping like the devil snapping his bubble gum, he will walk again in the minds of his victims and their families. Old case files will be reopened. Healed wounds will be torn apart. Spisak, convicted of a series of 1982 murders and sentenced to death, has fought hard to live. The state of Ohio - navigating a gauntlet of court appeals - has tried just as hard to kill him.

Last October, three federal appeals court judges struck down Spisak’s death sentence and ordered him resentenced. The judges said Spisak’s lawyer had been ineffective and that the judge had given the jury improper instructions during his 1983 sentencing. Although Spisak’s guilty verdict still stands, a new jury may deliver a sentence as early as this summer. Spisak’s lawyer plans to argue that he killed because he was insane and should be spared from death.

Raised by emotionally distant parents, Frank Spisak was beset by gender issues from childhood. He blamed “an extremely strict mother who humiliated and hit him when he displayed sexual behavior,” says one court document. She “taught him to hate people of color and others whom she deemed to be ‘undesirable’ or ‘repulsive.’ ”

Even as Spisak married, he took female hormones, anticipating a sex-change operation that would never happen. He used his quick and inquisitive mind to mentally rebuild the Third Reich, joining the National Socialist White People’s Party and fancying himself a storm trooper. He collected guns.

Today Spisak’s world is a prison cell at the Mansfield Correctional Institution. Inside it he lives as a woman, corresponding through prison pen-pal Web sites, trolling for “very special girlfriends.” He signs his letters Frances Ann, under “With love” or “Every best wish.” And no one - not even his psychiatrists - can say with certainty where the invented Frank ends and the real Frank Spisak begins.

The story of Spisak and those he killed and tried to kill is a morality play with the moral still to be written. At first, the victims seem like random choices. Separated by age and race and gender and class, they would not have found themselves side by side on the same city bus. But what they had in common was this: They were all strivers after something better, people who had changed courses in life, seeking another chance. And Cleveland is a city built on second chances.

The city we live in was born that summer. Four years after default, and after 13 years of burning river jokes, we declared ourselves back on track. As The Cleveland Press closed and Halle’s department store faded, Time magazine pronounced us one of the country’s most desirable cities and the “CBS Evening News” reported we were on the road to recovery.

We did not feel like a city under siege. As crime scene investigators were pulling slugs from a campus wall, Duran Duran was opening for Blondie a few blocks away at the Agora. As another victim lay bleeding, moving vans emptied the Williamson and Cuyahoga buildings on Public Square for demolition before the building of the new Standard Oil Tower. Everywhere, the 19th century was making way for the 21st.

Second chances seemed very real then. Now, Frank Spisak has a simple request: Give me a second chance. Twelve jurors will decide how far second chances extend. On one side of the courtroom, those who hope that justice will finally be done and a verdict carried out will gather. On the other side will stand a man who believes that true mercy cannot be strained, even if is stretched thin over a quarter century.

A gavel will bang like a pistol shot. Suddenly it will be 1982 all over again. “I’m on death row for killing three men. … Although I’ve been locked up a long time, I still feel like I am young and have a lot of life left in me to live; I don’t want to have to waste it rotting in some prison! … I devote all my energies toward trying to win my appeal and get me out of here before it is too late for me to have a real second chance in succeeding in life.” Frank Spisak, in prison letters posted on the Web site mansonfamilypicnic.com.

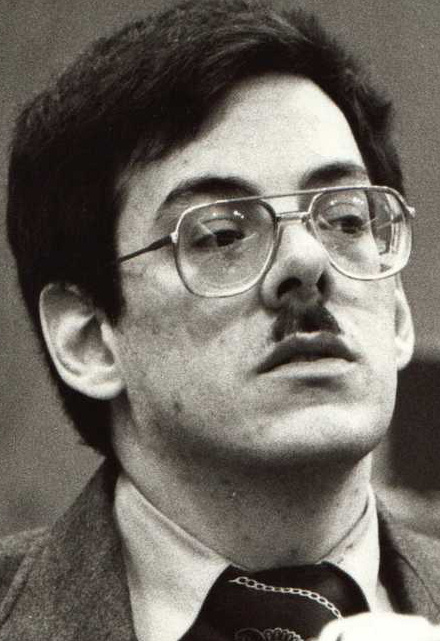

After the cops and the coroners finish their work, the flattened slugs and photographs of spent bodies go into a fat manila folder in the Cuyahoga County Prosecutor’s Office. The folder lands on the desk of a young assistant prosecutor named Donald Nugent. He is an ice pick in a nice suit. He is 34, with a diploma from Xavier University and a Cleveland Marshall law degree folded neatly around a stint in the Marine Corps. He is halfway through a career that would see him try 50 murder cases and prosecute at least that many rapes. The graying prosecutors in the office have dubbed him “Jack Armstrong,” like the “All-American Boy” of old radio shows, and he is golden.

It is 1983, and Nugent reaches into a manila folder. He looks at pictures of what seems like half of Cleveland, bleeding.

Here is the Rev. Horace T. Rickerson, dead, shot seven times on Feb. 1, 1982. “Four spent bullet casings were recovered from the scene,” a court document reads in the same flat prose that lists ingredients on a cereal box. The pastor of the Open Door Missionary Baptist Church, Rickerson had looked at its cramped home on East 83rd Street and dreamed, because dreams not only turned into classrooms and towers, but into spires and pulpits, too. In December 1975, a ground-breaking ceremony was held, and in March 1977, Rickerson dedicated the brand-new church on Woodland Avenue, just up the street from the borrowed room above a laundromat where the congregation had started 50 years before.

A weekly radio show called “Heart to Heart” on WJMO carried Rickerson’s sermons. His last broadcast, aired the night before he died, was titled “How to Know You Are Saved.” Rickerson left to research a sermon at Cleveland State’s library and never returned. He went home. That’s the way church people say it: He went home. That August, Rickerson’s congregation gathered without him for a ceremony to burn the paid-off mortgage.

Here is John Hardaway, a working man. He had spent his young life looking at the world from inside a bottle. He battled alcohol’s demons and wrestled them to a draw, remaining sober for 17 years. “It was really a tribute to John that he stayed with it,” Nugent says now, remembering. “Every Friday night he’d go to the Black Horse Tavern and have two little cans of orange juice, cash his paycheck, and walk over and take the Rapid home.”

Hardaway was shot seven times on the evening of June 4, 1982, while waiting for an RTA train at the West 117th Street Rapid station. His one quirk, for jewelry, saved his life: A medallion he wore on his chest deflected the killing bullet aimed at his heart. “Three pellets and seven shell casings were recovered,” the court document reads. “Just imagine the Rapid driver,” says Nugent. “She pulls up to the stop at 11:30 at night and she sees Hardaway there, bleeding. And then she calls police.”

Here is Coletta Dartt, a Cleveland State University employee, who at 5 p.m. on Aug. 9, 1982, left her office to use the restroom. Exiting the stall, she encountered Spisak, holding a gun, who ordered her back into the stall. Dartt - a black belt in karate - shoved him out of the way and ran down the hallway. Spisak fired a shot as she fled. “A pellet was later removed from a wall in the hallway.”

Here are Timothy Sheehan, Cleveland State University’s assistant superintendent of buildings and grounds, and CSU student Brian Warford. Sheehan had crossed an ocean and Warford had ridden a city bus to end up at the school. There they ran afoul of a man on a different career path, and both died.

Sheehan, dead at 50, was discovered by a campus security guard on Aug. 27, 1982. He had been “shot four times, and two pellets were retrieved from the scene.” Warford was found three days later at a Euclid Avenue bus stop, dead at 17 of a “single gunshot wound to the head, although five spent .22-caliber casings were recovered from the scene.” “This was not some random spree,” Nugent says now. “Here was a guy who was a pervert right from the beginning. And who had a gun. And the gun gave him power.”

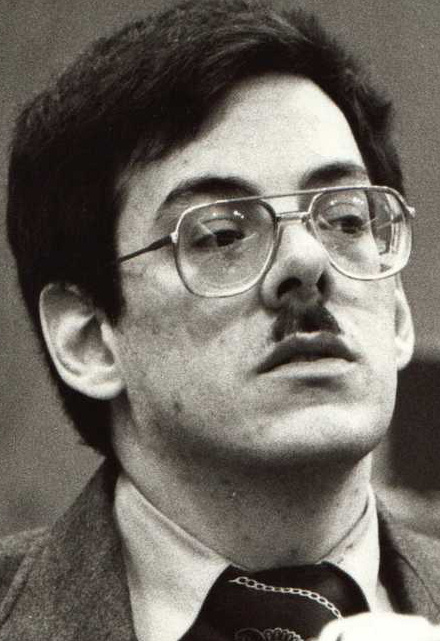

It’s June 1983, the day of trial. The court-appointed defense team huddles at the table across the aisle from Nugent. The accused squints through Coke-bottle glasses from behind a belly-warmer tie. The Sheehan family survivors watch from the back. And here comes Judge James Sweeney in his black robe. As the bailiff calls, “All rise,” the courtroom stirs.

The people in the folder do not move. “

The Brendan I saw was a frightened, devastated young man surrounded by his three sisters and his mom, not knowing what to make of the fact his dad, his best friend, was gone. And then trying to take his dad’s place and not knowing really how to do it.”

“He loved his yard, his garden,” says Brendan Sheehan, Timothy’s son. “It’s funny: A few weeks prior to my dad’s death, my sister had graduated high school. For a graduation present, my sister wanted to go to Ireland, and she and my dad went. He had said, ‘Brendan, you stay home and make sure the lawn is cut,’ stuff like that. “He came back, and it was, ‘OK, here’s the thing - you didn’t cut the lawn right; here’s how you work the hedger.’ It’s kind of ironic, like he was preparing me.”

Tim’s own college career had been full of bicycle rides across ancient lawns with professors. Born in County Cork, Sheehan attended Maynooth College, west of Dublin. Now Sheehan was an American, with a mortgage to prove it. He got up at 5 or 6 in the morning to catch the bus to work and returned at 6 in the evening. Nothing ever happened on his shady street in Fairview Park, and people worked themselves woozy to keep it that way.

The day someone decided to kill Tim Sheehan, the family planned to celebrate Brendan’s 15th birthday with dinner at a restaurant. At 2 p.m., Sheehan left his briefcase, glasses and coat at his desk, hustled off to check a report of a faulty door lock and vanished. Beeper pages went unanswered. Four hours later and a city away, a Fairview police cruiser pulled into the Sheehan driveway.

Bad news flooded the family room. “It was surreal,” Brendan remembers. “You’re looking at your mom. You’re thinking, ‘He died? How’d he die?’ He was murdered. Who would do that?” “I like classical music and games like chess. I used to enjoy collecting stamps - ‘the quiet hobby’ it is called.”- Frank Spisak “He is a coward. When you hide in darkness and in-wait for an unsuspecting person, and you have a gun and they don’t know what’s happening, and you ambush them - which is what he did to everybody - that shows he’s a coward.” Donald Nugent

“Slayings end myth of CSU as urban oasis” (Plain Dealer headline, Sunday, Sept. 5, 1982)

He was a little man in search of a soapbox. Frank Spisak dressed sharp, drove a candy-apple-red Mustang and considered himself a self-taught student of history. At Midpark High School, Class of ’69, he had been a scrawny library aide, singing in the choir and glee club. He liked to talk race hate and fascist politics, using words that hit like fists.

“After graduation from high school I had planned to study history in college,” Spisak wrote from his cell, “but went to work in a factory instead because I wanted money to buy myself a car and do other things.” He entered Cleveland State in 1969 but dropped out after 40 credit hours. By 1972, he was working at a factory on Cleveland’s East Side. Spisak courted a co-worker, Laverne Lampert, with flowers and Elvis Presley records. They married within a year and had a daughter.

By 1977 or 1978, after a car accident that Laverne thought had “messed his mind up,” Frank started wearing dresses during neighborhood strolls. He listened to albums of Hitler speeches. After he brought home another cross-dressing man and slept with him, Laverne walked out. They briefly reconciled two years later, but then he confided that he had always wanted to become a woman. Hormone treatments would be great, he said. Be a man, she said. She left again.

Spisak took a job that year as a machinist at the Edward Daniel Co. on St. Clair, with a Teamsters Local 507 card in his wallet and $220 every payday. He collected guns, dressed as a woman on weekends and discussed the finer points of Nazism and gay porn with any co-worker who’d listen. He took home men and partied with a black prostitute, substituting firearms for payment when he was short of cash. “Hunting parties,” Spisak called his forays out to rob and kill. Spisak stalked his victims in the city’s lonely corners. He hunted where he felt most comfortable. He returned to Cleveland State to wander the campus and study Nazi history in the university library.

And there was Brian Warford, waiting.

If good luck were pocket change, Warford would not have had bus fare. Two years before, in 1980, he had dropped out of Collinwood High as a sophomore. He’d been kicked out of the house after he stole his father’s van and his credit cards. “A loner who lacked discipline,” his father growled. Brian went to live with a sister.

But at 17, Warford saw that his life needed to come around, or he would die on the streets. Warford enrolled in an alternative education program offered at CSU, and suddenly his GED was not just a pretty thought. After late classes, he waited at a bus stop on Euclid Avenue. A pistol barked and Brian Warford fell to the sidewalk.

They found him sprawled on the cold pavement, on his right side. A single bullet rested in Warford’s head. In his trouser pockets were two lottery tickets; both tickets were losers.

“Instead of defending the mentally ill and standing up for their civil rights (rights to which they are entitled as American citizens), the lawyers in our communities have joined prosecutors and tough minded ‘hard-on-crime’ judges in sending mentally ill persons to prison and death row - treating us like we are habitual criminals!” Frank Spisak “First he’s trying to say he didn’t do it. And when he came to the point when he realized the gig was up, that’s when - for the first time - he turns to this White Power BS, this Nazi stuff. Which he had an interest in. But that wasn’t why he was killing. The reason he was doing these killings was that he was a pervert and was looking for his own self-gratification.” Donald Nugent

On Sept. 4, 1982, two Cleveland patrolmen climbed the stairs to a second-story walk-up at 1367 E. 53rd St. Labor Day weekend had just begun, and here was a call about shots fired from an apartment window, proof that when you mix alcohol and gunpowder, you get handcuffs. The resident said he had nothing to hide. Which was true: A shotgun and a 22-caliber pistol were clearly visible. The cops found a loaded .38 revolver and a two-shot Derringer buried under the sofa cushions. Frank Spisak was booked for possession of unregistered handguns and for discharging firearms within city limits. He posted bond and walked.

Two days later, the street swarmed with bulletproof vests. Two tips had told police that the gun used in the CSU murders was already in their possession. Ballistics tests linked Spisak’s .22 to Sheehan’s and Warford’s murders. Inside the apartment police found newspaper clippings detailing the killings, but no Spisak. He was pulled later that day from a friend’s basement, crouching next to a getaway suitcase. Detectives pawed through the contents: Inside was Tim Sheehan’s beeper.

Reporters barreled down I-71 to Midpark High, where old yearbooks were mined. One ex-classmate remembered the argumentative glee clubber, the library geek who talked himself into trouble and thought he could talk his way out again. He didn’t know why Spisak would murder, but “I suspect Frank has a logical explanation.”

Spisak told court-appointed psychiatrists “he tried to kill Coletta Dartt because he became angry when he heard people making fun of the White People’s Party,” a court document reads. “He decided to teach her a lesson and intended to ‘slap the shit out of her and rob her’ when she came out of the ladies’ room at Cleveland State.”

He said he “felt good” about shooting Warford. His biggest worry was “getting back across to the other side of the campus” to his car, according to one psychiatrist. “I figured in the early morning hours it was so quiet, somebody was bound to hear all the shots.” He admitted he was worried about getting caught after the first murder. “He shot Hardaway on the other side of town away from Cleveland State, where the other shootings had taken place, because ‘he didn’t want the police to link the two shootings together and link it to [him],’ and he ‘didn’t want to get caught.’ ”

After murdering Sheehan, he said, he “picked up the brass casings from his gun because the brass is worth money and also because ‘it’s sloppy to leave it laying around.’ ” “Spisak has come to a deep and intelligent understanding of the mental illness and gender identity disorders that drove his unfortunate and painful actions. The understanding underlies his deep remorse. ” defense attorney Alan C. Rossman

“Twenty-five years later, to somehow say, ‘Well, he’s got some mental problems …’ The jury heard all that. And the jury said he was responsible.”

At the trial, Fank Spisak never said he was sorry. To the families, he offered no apology. The monthlong trial began on Monday, June 13, 1983, in the common pleas courtroom of Judge James J. Sweeney. “Part of the job that you’ve undertaken is going to be sitting in judgment of a sick and demented mind that spews forth a philosophy that will offend each and every one of you,” defense lawyer Thomas M. Shaughnessy told the jury. “Make no mistake about that, you will be offended.”

Spisak grew a Hitler mustache for the trial. He greeted his lawyers with a Nazi salute. He answered Judge Sweeney’s questions with a German “jawohl” instead of “yes.” On the stand, he spoke of race war and of killing “the enemy” - Rickerson, Warford and Hardaway were black, and Sheehan “looked like a Jew professor,” Spisak said.

Faced with ballistics evidence linking Spisak to the murders and eyewitness identification from the survivors, Shaughnessy bet his client’s life on an insanity defense. But on July 11, Dr. Oscar B. Markey, the only psychiatrist called by the defense, testified that Spisak was the victim of several known mental disorders - none of which could be characterized as mental illness. Judge Sweeney asked Markey for clarification. Was Spisak mentally ill when he committed the crimes he was accused of? Was Spisak mentally ill now? “No,” Markey said. “No.”

Sweeney then instructed the jury not to consider Markey’s testimony in its deliberations. Two days later, he ruled that Spisak knew right from wrong and understood the consequences of his actions, so he could not plead “not guilty by reason of insanity.”

Resigned to a guilty verdict, Spisak’s defense looked ahead toward finding mercy in the sentencing part of the trial. “In this segment of the trial, the defense has no defense,” Shaughnessy told the jury in summation. He would see them again, he promised, during the penalty phase. After 60 witnesses and 250 exhibits, the jurors concluded, beyond a reasonable doubt, that Frank Spisak did murder and rob, propelling bullets into the bodies of his victims. This took just over five hours.

A reporter asked Spisak if he could think of any reason he shouldn’t be electrocuted. “Not offhand; can you?” Spisak said. Then he grinned. During the penalty phase, a line of psychiatrists took the stand for the defense. “Mentally unwell,” Dr. Oscar B. Markey called Spisak. “He lacks finer feelings. He is governed by fear, by anger, by circumstance, and not by remorse, by tenderness, or feelings of modesty.”

Dr. Sandra B. McPherson, a clinical psychologist, said Spisak detailed the killings to her matter-of-factly, showing no remorse. “It was like,” she testified, “discussing what I had for breakfast.” She was visibly shaken as she recalled Spisak’s inkblot test - Spisak, she said, saw only bloodstains and body parts. But none of the experts could pronounce Spisak legally insane. “Troubled” and “unwell” would not save his life.

The back of the courtroom had already reached a decision. “He’s a cold-blooded killer, and he’s no good,” a recovering John Hardaway told reporters. “He was killing people for no good reason, and he should be electrocuted.” Even Spisak’s defense attorney seemed eager to help throw the switch. As his client’s life hung in the balance, Shaughnessy’s summation murdered each victim again. “Every one of us who went through this trial, we know we can feel that cold day [and] see Horace Rickerson dead on the cold floor,” Shaughnessy said. “And we can all know the terror that John Hardaway felt when he turned and looked into those thick glasses and looked into the muzzle of a gun that kept spitting out bullets.”

Shaughnessy did argue that Spisak was mentally ill, but soon undermined his own argument. “Don’t look to him for sympathy, because he demands none,” Shaughnessy said. “He is sick, he is twisted. He is demented, and he is never going to be any different.” Summing up, Shaughnessy told the jury, “Whatever you do, we are going to be proud of you.”

After five hours of weighing testimony and balancing death against life with the possibility of parole, the jury voted with John Hardaway, for a death sentence. Judge James J. Sweeney thanked the jury. Spisak rocked in his chair.

Spisak’s final address to the court was the soapbox he’d lusted after for 32 years. “Even though this court may pronounce me guilty a thousand times, the higher court of our great Aryan warrior god pronounces me innocent,” he shouted. “Heil Hitler!”

Asked about his victims’ families afterward, Spisak was bitter. “If it makes them happy, if it makes the whole city of Cleveland happy, if they’re going to dance and celebrate my death, then let them dance and celebrate because today I die and tomorrow it will be them.” But he would not run to the electric chair. “Now [my lawyers] are going through the appeals process … until they no doubt exhaust all the different options open to them.”

He expected to buy time, but not a second chance. The appeals might win him “a year, two years, or maybe 10.” Then, Spisak said, it would be time to ride “old blunderbolt.” Instead, Frank Spisak would outlive his lawyer and the memory of most of the city.

For 25 years, Spisak has lived on prison food and court appeals. In a series of colorful filings, Spisak has argued that since transsexualism is considered a “mental defect” under Ohio case law, the state of Ohio should pay for a sex-change operation for him. He has also asked to be allowed to resume collecting stamps and corresponding with other collectors - a request denied when he mentioned, “My specialty is collecting old German postage stamps, especially those from Nazi Germany.”

Last year a three-judge panel of the U.S. Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals went into the fat folder filled with bodies and shells and balled-up crime scene tape, and hope sprung again in a cell in the Mansfield Correctional Institution. The judges upheld Spisak’s conviction, but ordered the case back for a new sentencing proceeding. They cited improper instructions given to the jury that suggested they needed to decide between life and death unanimously. Actually, only a death sentence must be unanimous. One dissenting juror can spare a defendant and force a life sentence instead.

The judges also hammered the late Thomas Shaughnessy for representing Spisak ineffectively. They criticized him for graphically recounting the crimes in his closing argument, expressing hostility and disgust for his own client and saying very little to offset either. Much of his argument “could have been made by the prosecution,” noted one judge dryly, “and if it had, would likely have been grounds for a successful prosecutorial misconduct claim.”

A new jury has to resentence Spisak - weighing “mitigating factors” such as his mental state. The Ohio Attorney General’s Office is considering an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, but it’s a long shot. Most likely, Cuyahoga County Prosecutor Bill Mason will have to argue all over again that Spisak deserves to die. Attorney Alan C. Rossman now represents Spisak. For Rossman, the “mitigating factors” are clear: We should not execute the mentally ill, and Frank Spisak is mentally ill. “The Nazism was very much a part of the identity disorder,” says Rossman. “What attracted him to the White People’s Party was the uniform and the structure - and the identity. It was a symptom of his illness as opposed to a driving force.”

Rossman calls the first trial “a circus,” in part because Shaughnessy let Spisak portray himself as a Nazi. “When reviewing the trial record, there was no question in my mind that his trial counsel had nothing but contempt for him,” Rossman says.

Rossman passed the bar in 1981. He was still hanging his law degree during that summer of 1982. He’s worked on several capital punishment cases. Each is a mental challenge for him. “You never divorce yourself from the victims,” he says. But when he tries to “understand the human side” of his clients, he realizes “how broken they are.” “The difficult thing is to suspend judgment and get beyond the fangs and talons that are being portrayed, and find out how they got to where they are. Which is not to condone anything that’s happened.”

The girl’s feet do not touch the floor. She’s wearing Dora the Explorer socks in SpongeBob tennis shoes and sitting in a too-big chair. The littlest victim stares past the framed photos in the Cuyahoga County Prosecutor’s Office lobby - full of old men in stiff collars and Herbert Hoover haircuts - to the TV. A cartoon aardvark named Arthur soars over his troubles in a magic plane. She and her mother have come to see Brendan Sheehan.

An assistant county prosecutor, Sheehan is director of the Internet Crimes Against Children division. When the investigators are through, everything - the pedophiles and abuse and monsters that swallow childhood - goes into a fat folder that lands on his desk. “Right now I have 40 pending cases on my docket,” he says, motioning at an office the size of a generous chimney.

A small man can cross a courtroom in a few steps. It took Brendan Sheehan 25 years to do it. After Sheehan graduated from Baldwin-Wallace College, Don Nugent pointed him toward a bailiff job and law school. Being a prosecutor, Sheehan says, is “my dream job.”

Frank Spisak is an almost-forgotten nightmare. “I’ve always prided myself on the fact our family doesn’t talk about Frank Spisak, doesn’t think about Frank Spisak,” Sheehan says. Now he will.

It will be left to Sheehan’s co-workers, his fellow prosecutors, to try this case. But he plans to be there, “sitting in the back of the courtroom, like I did 25 years ago.” As the surviving head of the Sheehan clan, sworn to protect his mother and sisters, how can he not?

He believes that keeping Spisak on death row is not impossible, but resentencing him will be tricky. “How do you recapture what was said 20-some years ago to a jury on how this guy deserves the death penalty?” Sheehan asks. “Times have changed.”

Donald Nugent is now U.S. District Judge Nugent, presiding over a courtroom in the federal courthouse on Huron Road and an office the size of the 14th green at Firestone Country Club. Spisak’s name comes up, and suddenly we are talking about marriage chapels. “I’ve gone to every one of Brendan’s sisters’ weddings and his wedding,” Nugent says, “and in the Irish tradition they have a father’s prayer. Well, he’s not there. And they always have someone say the father’s prayer in place of Tim. That comes home to Kathleen and the kids. In the happiest moment of their lives, the Sheehans are reminded of the butchering of Spisak and the loss of their father.”

No matter how the case ends, Nugent says, “All of the victims’ families will know that the police, the prosecutors and everyone who was charged of representing them did everything that was legal and proper and appropriate to see that justice was done. And the fact that someone, maybe, didn’t was not something they had control over.”

If he weren’t a judge, would Nugent like another crack at prosecuting Spisak? You do not ask a barber if you need a haircut. “In a minute,” Nugent says. “And I would be his worst nightmare.” Sometime soon, perhaps this summer, another jury will be handed a fat folder filled with spent slugs and bleeding bodies and crime scene tape. They will weigh whether a damaged man deserves a second chance, though he took such chances away from three others.

Cuyahoga County Prosecutor William Mason will seek another death penalty for Frank Spisak. He has promised to deliver his office’s lead arguments himself.

A gavel will bang like a pistol shot, and Spisak will live or die. Another judge will enter a courtroom as the bailiff calls, “All rise.” Regardless, the people in the folder will not move.

"Cheating Death "A cross-dressing Nazi murdered a prosecutor's dad 25 years ago. He's back." by Jared Klaus.

"The buses kept coming. As each slowed to a stop, Brendan Sheehan scanned the glowing windows for his father. But he only saw strangers. His dad, the maintenance supervisor at Cleveland State, was never late. And he surely wouldn't be tonight. It was Brendan's 15th birthday, and Tim Sheehan was taking the family to dinner.

Brendan, his worried mother at his side, thought about this as he choked back diesel fumes. Another bus came, emptied, grumbled away. Then another. "The buses kept coming," remembers Brendan. "My dad never got off."

Then a police car rolled around the corner into the Sheehans' quiet, flag-waving Fairview Park neighborhood, and into the driveway of their two-story home. The officer sat his mother down in the family room. Your husband's been killed. "Every time I walk into that room in my mom's house," says Sheehan, "I remember that conversation."

His next vivid memory is sitting in court -- "the green, ugly cloth chairs" -- looking into the eyes of the man who murdered his father. He was a puny loser named Frank Spisak, who dressed as a woman and fantasized he was a Nazi, killing black men in the name of Hitler. Tim Sheehan, an Irish immigrant, had simply gotten in the way.

Spisak sat proudly on the stand wearing a Hitler mustache, presenting an odd visage of the master race, cavalierly chatting about his killings as acts of God. But he found a superior nemesis in bad-ass prosecutor Don Nugent. Nugent patiently baited Spisak with his own vanity, spun him into a corner, then exposed him as nothing more than a punk, a coward, a Nazi wannabe, and dime-store thief.

Spisak was sentenced to death. The prosecutor became Sheehan's hero, justice personified.

Twenty-five years later, Sheehan has taken Nugent's place. He's now the toast of the Cuyahoga County Prosecutor's Office, handling more than twice the caseload of the average prosecutor and trying murder cases of his own. It's as if that moment in court more than two decades ago never left him.

"It's almost like he's on a mission," says Assistant Prosecutor Dan Kasaris. "He's a bulldog."

The walls of Sheehan's closet-like office are papered with mementos from his cases -- exhibits, crayon drawings from young victims of molestation, and pictures of his three young children. Strangely absent are any pictures of his father. He's never really talked about his dad's murder. Not even his wife Michelle knows the details.

But now Tim Sheehan's brutal killing is about to be splashed across front .ages again. Frank Spisak, still alive 25 years after his death sentence, finally found a sympathetic ear last month. A federal appeals court ruled that his lawyer had committed misconduct and struck down his death sentence. He'll likely be returning to the Justice Center, right by Sheehan's office, where the whole charade will play out again.

Now the prosecutor must do something he never prepared for: explain to his daughters, ages six and eight, that their grandpa was killed by a piece of shit. His eight-year-old is already so paranoid from overhearing her parents talk about the real-life monsters of Sheehan's work that she locks all the doors and windows in the family's home at eight o'clock every night.

But Sheehan says the hardest part was telling his mother and sisters "that this nightmare is creeping its way back."

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Frank Spisak Jr. was a nobody until he started killing.

In high school, he was just an awkward dork who liked to draw swastikas. His dad, a factory worker who played the trumpet in a polka band, had packed up his family and fled their neighborhood near Buckeye Road to escape black migration, moving to Middleburg Heights when Frank was young. Spisak, a member of the chess club, was just a nerd looking for attention.

He enrolled at Cleveland State, but dropped out the following year when he could no longer afford tuition. So he made a curriculum of his own at a downtown bookstore, where he worked the stock room, mostly feeding his bizarre appetite for everything Hitler. He read so much that he eventually wore his eyes out, requiring thick, jar-bottom glasses.

At 22, he married a woman named Laverne. They had a daughter, Sally Ann, and Spisak found work at a string of dead-end factory jobs, once making casket parts at a shop on Madison Avenue. Laverne found the whole Nazi thing a bit off-putting, but it wasn't enough to make her leave. Even when her husband blasted taped speeches by Rudolf Hess, Hitler's deputy, Laverne just tried to shut her ears.

But after three years of marriage, things started getting really weird. Spisak suffered a head injury in a car accident that "messed his mind up," Laverne would later testify. Her husband started expressing dark desires and dressing like a woman. At night, he'd go out on the corner and get paid to turn tricks for guys looking for a lady with a little extra equipment.

Laverne told her husband he was "sick in the head" and that he needed help. Spisak ignored her pleas. Then things got even more bizarre. One night, Spisak came through the door of their East 53rd Street home with a transvestite, walked by his wife, who was sleeping on the couch, and went into the bedroom to have sex with the man. "I told Frank it's either me or that thing," Laverne said later. Her husband picked the latter.

Laverne packed up their daughter and left, taking everything -- even the refrigerator and stove. Spisak was left with little more than a hot plate and a coffeepot.

He started dressing like a woman full-time, and had the license bureau change his name to Frankie Ann. He saw a psychologist about getting a sex change, and even began taking hormone treatments. But he couldn't afford the surgery, and he made an ugly woman. With his bad makeup and frizzed-out hair, he looked like Little Orphan Annie gone disco. The guys in the neighborhood would whistle caustically from their porches as Spisak walked by.

Frank, too, seemed to loathe Frankie Ann, and his fascination with Hitler grew into an obsession. He started collecting Nazi memorabilia, swords, framed pictures of Hitler. Neighbors would hear him blasting the Führer's speeches in German on his stereo, as Spisak marched back and forth across his living room, dressed in military garb. He developed an obsession with guns and ammunition, and started stockpiling.

Strangely, he also began dating a black female prostitute. Even as a Nazi, Spisak failed. Then God saved him, he would later recall for a jury.

On the morning of February 1, 1982, he was at the Cleveland State library on the first floor of Rhodes Tower, reading a 1930s book of Nazi propaganda, when he got up to go to the bathroom.

Inside, Spisak saw two feet underneath the door of one of the stalls. He went to the next toilet and put his eye up to a hole bored in the wall -- it was a black man, the Reverend Horace Rickerson. Accounts of what happened next are fuzzy, but the prosecution later claimed that Spisak had asked the reverend for sex but was rejected.

Spisak then pulled a pistol from his pocket, stuck the nose through the hole, aimed at Rickerson's torso, and squeezed until there were no more bullets.

As the preacher slumped to the floor, Spisak fled to the library snack bar. He felt "pretty good" about the killing, he would say later. So good, he sat down and enjoyed a cup of coffee. But curiosity got the better of him, and he returned downstairs to watch a crowd gathering around the bathroom. There, he locked eyes with the campus maintenance man. Something in his eyes spooked Spisak, some hint of recognition -- as if the man knew he was looking at the killer. Tim Sheehan had no idea that his life had just been set on a timer.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Love brought Tim Sheehan across the Atlantic. He was working as a policeman in England when he met his wife, Kathleen, an Irish ex-pat living in America. He followed her back, and they started a family in the melting-pot suburb of Fairview Park.

He got work where he could, first managing the warehouse at Higbee's, eventually working his way up to overseeing maintenance at CSU. Every night, neighbors would see him walking home from the bus stop, briefcase in hand, young Brendan clipping at his heels. "I think they were very, very close," says longtime neighbor Stephanie Gamery. "All the girls were good, but Brendan was kind of standout."

The Sheehans were true Irish. Gamery remembers Kathleen sending over warm soda bread, and Brendan and his sister performing a traditional dance at one of her ladies' club meetings. "They were just charming," says Gamery, in a crackly grandmother's voice. "They literally stole our hearts."

Yet not far from Fairview Park, Cleveland had become gripped by violence. The summer of '82 was a bloody one. The city was averaging four dead bodies a week. Gang killings were rampant. People fled downtown each night, afraid to be caught there after dark. Police didn't know yet that a serial killer was in their midst. Murdering the preacher had put a taste in Spisak's mouth. It felt as if he had "accomplished something," he would claim.

He'd also befriended another loner and Nazi wannabe, Ron Reddish. Together, they'd cruise the streets in Reddish's Buick LeSabre, looking for black men. "Hunting parties" is what Spisak called them. He found his second victim late one hot June night. John Hardaway walked into the Black Horse Café on Madison and West 117th, just as he had every payday for 17 years. The bartender cashed his check as he drank a glass of tomato juice. Then he left to catch the Rapid at the station across the street.

As Hardaway waited for the train, he glanced over to see a man standing with his legs spread apart, arms extended, squeezing the trigger of a .22-caliber semi-automatic pistol. Five bullets riddled Hardaway's body. He crumpled to the ground, crawling away on numb limbs as he faded out of consciousness. Four days later, he awoke in a hospital bed. One of the bullets had struck a gold medallion hanging from his neck, saving his life.

A couple months later, Spisak returned to CSU. Coletta Dartt, who worked in the chemistry lab, was just getting off work at five o'clock when she stopped to use the bathroom. When she opened the stall door, she was staring down the barrel of a gun. "Get back!" Spisak demanded. Dartt pushed him away and ran into the hallway. Spisak chased after her and fired a round down the hallway, but missed. A frantic crowd poured from the classrooms. But Spisak was gone. Panic gripped the campus. Rewards were offered for information on the bathroom shooter. But police were without a solid lead. The attacks seemed so random.

Still, Spisak was paranoid. He kept thinking of the maintenance man outside the bathroom the day he killed Rickerson. So he began to follow the man around campus, prosecutors would later speculate. One day he walked past Tim Sheehan intentionally, just to see if he could notice a look of recognition on the man's face. He was sure that he did.

On the morning of August 27, 1982, Kathleen Sheehan gave her husband $10 and waved goodbye. Tim was cutting out of work early that day to play golf, then coming home for Brendan's birthday. With the summer session concluded, Rhodes Tower was eerily empty. As Tim stood at the urinal, feet shuffled in behind him. He turned around to see Spisak pointing a pistol at his forehead. The two men locked eyes in silence. Then two bullets blew out the side of Tim's face. One pierced his neck. Another hammered into his chest. Tim fell face down in a pool of blood and urine. As the last twitches of life left Sheehan's body, Spisak rustled around in the man's pants and took out his wallet, which held the $10 Sheehan's wife had given him. Spisak went home and waited for the hysteria to hit TV news.

He would claim he felt that God had made him invisible, "stuffing the ears of everybody." So he went hunting again the next night. Seventeen-year-old Brian Warford, waiting at a bus shelter on Euclid outside campus, died instantly from a perfectly placed shot to the head.

A week later, police actually had Spisak in custody. He was arrested after getting drunk and shooting his gun out the window of his house. But the cops had no idea he was the Cleveland State killer, and Spisak was allowed to post bond.

For the moment, he was invisible. But God couldn't protect Spisak from his own mouth. He'd bragged about the murders not only to his ex-wife, but also to his girlfriend. Then police received an anonymous call, telling them to take a second look at the guns they'd confiscated from Spisak's house. The weapons matched those used in the killings.

Spisak was driving home one day when he saw squad cars lining his street. He drove to Reddish's house, but a neighbor tipped police. They found Spisak crouched in a basement crawl space. The CSU killer was behind bars. For the first time in months, the city could sleep.

Spisak proudly admitted to the murders, even autographing his swastika T-shirt for detectives. He came to court with his head held high, sporting the Hitler mustache he'd grown in jail, carrying a copy of Mein Kampf, and greeting Judge James Sweeney with a "Heil Hitler" salute. Yet he didn't seem to grasp the contradiction that a member of the master race was pleading insanity.

Defense attorney Tom Shaughnessy could do little except paint his client as crazy as he seemed. He put Spisak on the stand, egging him into casually admitting to killing in the name of God and Hitler, whom he regarded as a Jesus figure. Blacks were overpopulating the world, Spisak argued, and he was helping cull the herd. "There's a lot of work to be done. Unfortunately, there's not enough people to get it done," he announced, his chin up in the air like a duke.

Lying in wait was Assistant Prosecutor Don Nugent, a lady-killer with the jurors, with piercing eyes and a poker-room swagger. "Nugent presents a very strong image, where lightning's going to flash from the heavens if you do wrong," says longtime defense attorney Richard Drucker. Nugent asked Brendan's mom to take the stand and do the unthinkable: stare down the man who gunned down her husband. Kathleen refused, terrified. Brendan pleaded with Nugent not to force her. "He was trying to be strong and take his dad's place," says Nugent.

But the prosecutor was stronger. Kathleen tearfully testified to the morning she said goodbye to her husband for the last time. In exchange, Nugent promised an eye for an eye. "That's a big responsibility," says Nugent. "If they put their trust in you, you better live up to it."

Brendan had envisioned his father's killer as a frightening monster. But what he found in court was a skinny, effeminate creep. "I think, 'Who is this punk, this squirrelly-looking punk guy?'" Sheehan remembers.

Spisak coldly recalled how he shot Tim Sheehan. "When I saw him go down, I knew I hit him," he testified. Shaughnessy showed him a crime-scene photo of Tim's body. "I thought I did a good job," Spisak said. Then Nugent came in for the cross-examine.

When Spisak proudly claimed he shot Hardaway at the Rapid station as "blood of atonement" for the recent Flats slaying of a white woman by a black man, Nugent pointed out that the killing hadn't been made public until a day after Hardaway was shot. Spisak had committed the crime for no more noble purpose than his own sick pleasure, Nugent told the jury. "Like your hero, Adolf Hitler, you got a yellow streak all the way down your back," Nugent taunted the enraged Nazi.

The prosecutor found Spisak's weaknesses and used them to humiliate him, calling him by his female name, Frankie. "The name is Frank to you, buddy," Spisak shot back. "The name is whatever I want to call you," Nugent replied. "I was overwhelmed by what [Nugent] was doing," Brendan remembers. He was "aggressive, prepared."

Not even the defense's own psychiatrist could help Spisak. In a shocking moment, the doctor testified that Spisak suffered a personality disorder -- not legal insanity.

Spisak was convicted for all the murders, and was as good as sitting in the electric chair. Asked by a reporter afterward if he could think of any reason why he shouldn't be fried, Spisak smiled and responded, "Not offhand, can you?" The jury agreed, sentencing Spisak to die. He left the courtroom with a rousing "Heil Hitler!"

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Sheehan never forgot the cowboy prosecutor. In his junior year of high school, he volunteered by passing out yard signs for Nugent's judicial campaign. Nugent, who won, was used to keeping in touch with the victims, but Sheehan would regularly call for advice. Nugent became his mentor, even steering him toward his alma mater, the Cleveland Marshall College of Law.