6th murderer executed in U.S. in 2014

1365th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Missouri in 2014

71st murderer executed in Missouri since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(6) |

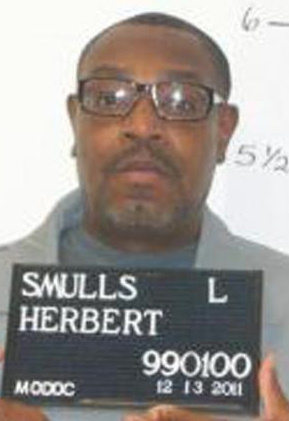

Herbert L. Smulls B / M / 33 - 56 |

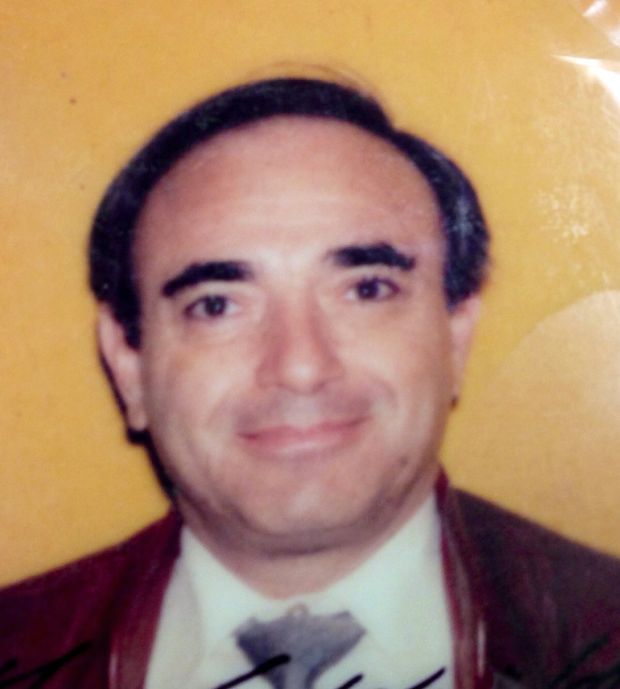

Stephen Honickman W / M / 51 |

Summary:

Smulls and Norman Brown followed another customer into a jewelry store owned by Stephen and Florence Honickman. Florence Honickman was unable to show any jewelry at that time but suggested she might be able to help them later. Smulls and Brown returned to the store that evening. After viewing some diamonds, Smulls and Brown went into a hallway, purportedly to discuss the diamond prices. A short time later, Florence looked up and saw Smulls aiming a pistol at her. She then ran and hid behind a door. Smulls fired three shots at her, striking her arm and side. Smulls then fired several shots at Stephen Honickman, who was struck three times. Smulls and Brown stole jewelry worn by Florence and other items in the store, then fled. Stephen died from his wounds and Florence suffered permanent injuries from the attack. A short time after the robbery, police stopped Smulls and Brown for speeding. While Smulls was standing at the rear of his car, the police officer heard a radio broadcast describing the men who robbed the Honickmans store. Smulls and Brown fit the descriptions. The officer ordered Smulls to lie on the ground. Smulls then ran from his car but was apprehended while hiding near a service road. The police found jewelry and other stolen items from the store in the car and in Brown's possession. Accomplice Brown was convicted and is serving two life sentences without parole, plus 90 years.

Citations:

State v. Smulls, 71 S.W.3d 138 (Mo. 2002). (PCR)

Smulls v. Roper, 535 F.3d 853 (8th Cir. Mo. 2008). (Federal Habeas)

Final Meal:

Fried chicken, steak, collard greens, macaroni and cheese, candied yams, corn bread, chocolate cake, and cola.

Final Words:

None.

Internet Sources:

"Missouri executes man for jeweler's 1991 death," by Jim Salter. (January 29, 2014 11:02 pm)

A Missouri who killed a jeweler during a 1991 robbery was executed for the crime late Wednesday, marking the state's third lethal injection in as many months. Herbert Smulls was executed by a lethal injection of pentobarbital at the state prison in Bonne Terre, and pronounced dead at 10:20 p.m. Smulls showed no outward signs of distress. The 56-year-old had been convicted of killing Stephen Honickman and badly injuring his wife, Florence, during a robbery at their jewelry shop in suburban St. Louis on July 27, 1991.

Smulls' attorney filed numerous appeals challenging the state's refusal to disclose where it obtained its execution drug. The U.S. Supreme Court granted a stay late Tuesday, shortly before the scheduled 12:01 a.m. execution, and eventually cleared all appeals on Wednesday night _ even the one Smulls' attorney filed less than 30 minutes before he was pronounced dead; that denial of a stay of execution came about 30 minutes after his death.

Defense attorneys argued that the state's refusal to name the compounding pharmacy supplying the pentobarbital made it impossible to know whether the drug could cause pain and suffering during the execution. The state maintained that the company was part of the execution team, so its name was protected from public disclosure. Attorney General Chris Koster said in a statement after the execution: "My thoughts and prayers are with Florence Honickman and the family and friends of Stephen Honickman."

Prosecutors said the defense's arguments were simply a smoke screen aimed at sparing a murderer's life. "It was a horrific crime," St. Louis County prosecutor Bob McCulloch said on Tuesday. "With all the other arguments that the opponents of the death penalty are making, it's simply to try to divert the attention from what this guy did, and why he deserves to be executed."

Smulls had already served time in prison for robbery when he went to F&M Crown Jewels in Chesterfield and told the Honickmans, who owned the store, that he wanted to buy a diamond for his fiancee. But Smulls planned to rob the couple, and took 15-year-old Norman Brown with him. "They planned it out, including killing people, whoever was there," McCulloch said. Smulls began shooting inside the shop, and he and Brown took rings and watches _ including those that Florence Honickman was wearing. She was shot in the side and the arm, and feigned death while lying in a pool of her own blood. Florence Honickman identified the assailants. Brown was convicted in 1993 of first-degree murder and other charges, and sentenced to life without parole. Smulls got the death penalty.

Smulls' execution was the state's third since it began using pentobarbital as its lethal injection drug. Missouri and other states had used a three-drug execution method for decades, but pharmaceutical companies stopped selling the drugs in recent years for use in executions. Missouri eventually switched to pentobarbital, which was used to execute serial killer Joseph Paul Franklin in November and Allen Nicklasson in December. Neither inmate showed outward signs of distress. The state said it obtained its supply of the drug from a compounding pharmacy, which custom-mix drugs for individual clients. They are not subject to oversight by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, though they are regulated by states.

Smulls' attorney, Cheryl Pilate, said she and her defense team used information obtained through open records requests and publicly available documents to determine that state obtained its drugs from The Apothecary Shoppe, a compounding pharmacy based in Tulsa, Okla. In a statement, the company would neither confirm nor deny that it made the Missouri drug. Compounding pharmacies custom-mix drugs for individual clients and are not subject to oversight by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, though they are regulated by states. Pilate said the possibility that something could go wrong persists, citing recent trouble with execution drugs in Ohio and Oklahoma. She also said that previous testimony from a prison official indicates Missouri stores the drug at room temperatures, which experts believe could taint the drug, Pilate said, and potentially cause it to lose effectiveness. Missouri Senate Democratic Leader Jolie Justus introduced legislation this week that would create an 11-member commission responsible for setting the state's execution procedure. She said ongoing lawsuits and secrecy about the state's current lethal injection method should drive a change in protocol.

"Missouri executes killer after top court denies appeals." (Thu Jan 30, 2014 3:31am EST)

KANSAS CITY, Missouri - (Reuters) - Missouri late on Wednesday executed a man convicted of killing a jewelry store owner during a robbery after the U.S. Supreme Court denied last-minute appeals that in part challenged the drug used in the execution. Herbert Smulls was pronounced dead at 10:20 p.m. local time at a state prison in Bonne Terre after receiving a lethal dose of pentobarbital, a fast-acting barbiturate, Missouri Department of Corrections spokesman Mike O'Connell said.

Smulls, 56, did not make a final statement, but asked which way he should look from the gurney to see his witnesses and nodded at them before being declared dead nine minutes after being injected with the drug, O'Connell said. Smulls was the sixth person executed in the United States in 2014 and the third in Missouri since November.

The U.S. Supreme Court on Wednesday lifted a temporary stay of execution for Smulls, denying last-minute appeals. The top court late Wednesday also vacated a stay from the Eighth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals that had prevented the execution. Lawyers for Smulls filed another request with the Supreme Court on Wednesday evening, but Missouri went ahead with the execution before the midnight expiration of the state's death warrant. O'Connell said the state followed procedures to ensure it was clear of all legal impediments to the execution. Lawyers for Smulls did not respond to requests for comment.

Smulls was convicted of shooting Stephen Honickman while robbing his jewelry store in July 1991. Honickman's wife Florence, who was also shot during the attack, sustained permanent injuries. Smulls was originally scheduled to die after 12:01 a.m. Central Time on Wednesday and so had his final meal of fried chicken, steak, collard greens, macaroni and cheese, candied yams, corn bread, chocolate cake, and cola on Tuesday afternoon.

'UNDUE SUFFERING'

Lawyers for Smulls had sought to block his execution on multiple grounds, arguing in part that the compound drug Missouri used to kill him might not be as pure and as potent as it should be, which could cause undue suffering. Missouri and several other states have turned to compounding pharmacies, which are not regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, to prepare drugs for executions after an increasing number of pharmaceutical manufacturers objected to their drugs being used in capital punishment. The increasing use of in some cases untested compounded drugs has revived the debate over the death penalty in the United States.

In Oklahoma, an inmate said he felt burning through his body when the drugs used to kill him were injected during an execution in early January. Later in the month, an Ohio man gasped and convulsed during his execution with a two-drug mix never before used in the United States. In the Smulls case, the Eighth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals found on Friday that his lawyers did not propose a feasible or more humane alternative than pentobarbital or showed that Missouri sought to cause him unnecessary pain by using the drug. The Eighth Circuit had separately granted a stay until the U.S. Supreme Court decided whether to hear the case.

The Supreme Court granted Smulls the temporary stay late Tuesday, hours before his execution was to be carried out, to consider his lawyer's arguments that prosecutors had improperly eliminated a black woman as a possible juror, leaving him with an all-white jury at trial. On Wednesday afternoon, the Supreme Court vacated the temporary stay and denied the request for a stay or to hear the appeal on the jury selection issue.

(Reporting by Carey Gillam and Kevin Murphy in Kansas City, Lawrence Hurley in Washington, and Heide Brandes in Oklahoma City; Writing by David Bailey and Eric M. Johnson; Editing by Eric Walsh, John Stonestreet)

Inmate: Herbert L. SmullsDate of Birth: 11/28/57

Received: 12/21/92

County: St. Louis

Executed: 01/29/14

State of Missouri v. Herbert L. Smulls

935 S.W.2d 9 (Mo.banc 1996)

Case Facts: Stephen and Florence Honickman owned and operated a jewelry store. Typically, customers would make an appointment to examine the jewelry for sale. In early July 1991, a person identifying himself as “Jeffrey Taylor” called the Honickmans and made an appointment to buy a diamond. “Jeffrey Taylor” was later identified as Herbert Smulls. On July 22, 1991, Smulls and Norman Brown went to the Honickmans’ store. After viewing several diamonds, Smulls and Brown left the store without making a purchase.

On the afternoon of July 27, 1991, Smulls and Brown followed another customer into the store. Florence Honickman was unable to show any jewelry at that time but suggested she might be able to help them later. Smulls and Brown returned to the store that evening. After viewing some diamonds, Smulls and Brown went into a hallway, purportedly to discuss the diamond prices. A short time later, Florence looked up and saw Smulls aiming a pistol at her. She then ran and hid behind a door. Smulls fired three shots at her, striking her arm and side. Smulls then fired several shots at Stephen Honickman, who was struck three times.

Smulls and Brown stole jewelry worn by Florence and other items in the store. After the two men left the store, Florence contacted the police. Stephen died from his wounds and Florence suffered permanent injuries from the attack. (This entry was posted in Current Death Row Inmates on December 4, 2008 by smays) P>

"Smulls execution a travesty,” by Bob Priddy. (AUDIO) (January 30, 2014)One of those who watched the state execute prison inmate Herbert Smulls late last night calls the execution “a travesty of justice.” The person making that charge is not one of Smulls’ supporters. It’s one of his victims. Herbert Smulls died 253 months aafter getting his death sentence for killing Chesterfield jeweler Stephen Honickman during a 1991 robbery. Although Honickman’s wife, Florence, was shot twice, she survived by playing dead. She says waiting more than twenty years to execute a murderer while the state spends millions of dolalrs on the inmate is a travesty of justice for her and her family. She says the state has not paid for any of her expenses to attend the execution.

She says there should be no reason, in a “just and a rational legal system” why appeals should continue longer than ten years. She says she and her family are the ones who have suffered cruel and unusal punishent; by having to wait so long for justice to be done. She says the system needs to spend more time thinking of the victims and less about the murderers.

AUDIO: post-execution news conference "Herbert Smulls to be executed by lethal injection Jan. 29," by Jessica Machetta. (12-09-13)

The Supreme Court has issued an execution date for Herbert Smulls, 56, who was sentenced to death for the 1991 shooting of Stephen and Florence Honickman at a St. Louis County jewelry store they owned and operated. The Supreme Court has issued an execution warrant, allowing the state to execute Smulls by lethal injection Jan. 29, 2014.

Typically, customers would make an appointment with the Honickmans to examine jewelry for sale. In July, 1991, a person identifying himself as Jeffrey Taylor called the Honickmans and made an appointment to buy a diamond. “Jeffrey Taylor” was later identified as Herbert Smulls. July 22, 1991, Smulls and Norman Brown went to the Honickmans’ store. After viewing several diamonds, Smulls and Brown left the store without making a purchase. On the afternoon of July 27, 1991, Smulls and Brown followed another customer into the store. Florence Honickman was unable to show any jewelry at that time but suggested she might be able to help them later.

Smulls and Brown returned to the store that evening. After viewing some diamonds, Smulls and Brown went into a hallway, purportedly to discuss the diamond prices. A short time later, Florence looked up and saw Smulls aiming a pistol at her. She then ran and hid behind a door. Smulls fired three shots at her, striking her arm and side. Smulls then fired several shots at Stephen Honickman, who was struck three times. Smulls and Brown stole jewelry worn by Florence as she lie on the floor with serious injuries, and then took other items in the store. After the two men fled, Florence called police. Stephen died from his wounds; Florence suffered permanent injuries from the attack. Brown remains in prison on two life sentences without the possibility of parole, plus 90 years. Brown is 37 years old.

"Missouri executes man for jeweler's 1991 death," by Jim Salter. (AP January 29, 2014)

BONNE TERRE, Mo. — A Missouri man who killed a jeweler during a 1991 robbery was executed for the crime late Wednesday, marking the state's third lethal injection in as many months. Herbert Smulls, 56, was executed by a lethal injection of pentobarbital at the state prison in Bonne Terre. He was convicted of killing Stephen Honickman and badly injuring his wife, Florence, during a robbery at their jewelry shop in suburban St. Louis on July 27, 1991.

Smulls did not have any final words. The process was brief, Smulls mouthed a few words to the two witnesses there for him, who were not identified, then breathed heavily twice and shut his eyes for good. He showed no outward signs of distress. He was pronounced dead at 10:20 p.m., nine minutes after the process began.

Florence Honickman spoke to the media after the execution, flanked by her adult son and daughter. She questioned why it took 22 years of appeals before Smulls was put to death. "Make no mistake, the long, winding and painful road leading up to this day has been a travesty of justice," she said.

Smulls' attorney, Cheryl Pilate, had filed numerous appeals challenging the state's refusal to disclose where it obtained its execution drug, pentobarbital, saying that refusal made it impossible to know whether the drug could cause pain and suffering during the execution. The U.S. Supreme Court had granted a stay late Tuesday, shortly before the scheduled 12:01 a.m. Wednesday execution, but the high court cleared numerous appeals on Wednesday night — even the one Pilate filed less than 30 minutes before Smulls was pronounced dead, though the final denial came about 30 minutes after his death.

When asked about the time between the appeal and the execution, Missouri Department of Corrections spokesman Mike O'Connell said, "I'm not familiar that." The state had maintained that the company was part of the execution team, so its name was protected from public disclosure.

Attorney General Chris Koster said in a statement after the execution: "My thoughts and prayers are with Florence Honickman and the family and friends of Stephen Honickman." Prosecutors said the defense's arguments were simply a smoke screen aimed at sparing a murderer's life. "It was a horrific crime," St. Louis County prosecutor Bob McCulloch said on Tuesday. "With all the other arguments that the opponents of the death penalty are making, it's simply to try to divert the attention from what this guy did, and why he deserves to be executed." Smulls had already served time in prison for robbery when he went to F&M Crown Jewels in Chesterfield and told the Honickmans, who owned the store, that he wanted to buy a diamond for his fiancee. But Smulls planned to rob the couple, and took 15-year-old Norman Brown with him.

"They planned it out, including killing people, whoever was there," McCulloch said. Smulls began shooting inside the shop, and he and Brown took rings and watches — including those that Florence Honickman was wearing. She was shot in the side and the arm, and feigned death while lying in a pool of her own blood. "I felt pain and terror while I lay on the floor playing dead while the murderers ransacked our office," Florence Honickman said Wednesday night. She was the one to identify the assailants. Brown was convicted in 1993 of first-degree murder and other charges, and sentenced to life without parole. Smulls got the death penalty.

Smulls' execution was the state's third since it began using pentobarbital as its lethal injection drug. Missouri and other states had used a three-drug execution method for decades, but pharmaceutical companies stopped selling the drugs in recent years for use in executions. Missouri eventually switched to pentobarbital, which was used to execute serial killer Joseph Paul Franklin in November and Allen Nicklasson in December. Neither inmate showed outward signs of distress.

Honickman's daughter, Mindy Wilner, was critical of the media questioning whether the drug could cause suffering for Smulls, saying it was the victims who suffered. The state said it obtained its supply of the drug from a compounding pharmacy, which custom-mix drugs for individual clients. They are not subject to oversight by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, though they are regulated by states.

Pilate said she and her defense team used information obtained through open records requests and publicly available documents to determine that state obtained its drugs from The Apothecary Shoppe, a compounding pharmacy based in Tulsa, Okla. In a statement, the company would neither confirm nor deny that it made the Missouri drug. Compounding pharmacies custom-mix drugs for individual clients and are not subject to oversight by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, though they are regulated by states. Pilate said the possibility that something could go wrong persists, citing recent trouble with execution drugs in Ohio and Oklahoma. She also said that previous testimony from a prison official indicates Missouri stores the drug at room temperatures, which experts believe could taint the drug, Pilate said, and potentially cause it to lose effectiveness.

Missouri Senate Democratic Leader Jolie Justus introduced legislation this week that would create an 11-member commission responsible for setting the state's execution procedure. She said ongoing lawsuits and secrecy about the state's current lethal injection method should drive a change in protocol.

Stephen and Florence Honickman owned and operated a jewelry business, F & M Crown Jewels in a basement level store below the American Bank building. Typically, customers would make an appointment to examine the jewelry for sale.

In early July 1991, a person identifying himself as Jeffrey Taylor called the Honickmans and made an appointment to buy a diamond. Jeffrey Taylor was later identified as Herbert L. Smulls. On July 22, 1991, Smulls and Norman Brown went to the Honickmans store. After viewing several diamonds, Smulls and Brown left the store without making a purchase. On the afternoon of July 27, 1991, Smulls and Norman Brown followed another customer into the store. Florence Honickman was unable to show them any jewelry at that time but suggested she might be able to help them later.

Smulls and Brown returned to the store late that evening. After viewing some diamonds, Smulls and Brown went into a hallway, purportedly to discuss the diamond prices. A short time later, Florence Honickman looked up and saw Smulls aiming a pistol at her. Stephen Honickman pleaded with them not to shoot but to take whatever they wanted from the store. Florence ran and hid behind a door. Smulls fired three shots at her, striking her arm and side. Stephen again yelled at them, "Stop shooting, you can have anything you want!" Smulls then fired several shots at Stephen Honickman, who was struck three times. Smulls and Brown stole a bracelet, necklace and ring worn by Florence Honickman as she pretended to be dead and other items from under the glass counters in the store. Florence said she heard her husband moaning but didn't move at first for fear they were still in the store. After she was sure the two men left the store, Florence Honickman called the police. Stephen Honickman was taken to the hospital but died from his wounds around 1:00 am. Florence Honickman suffered permanent injuries from the attack.

A short time after the robbery, police stopped Smulls and Brown for speeding. While Smulls was standing at the rear of his car, the police officer heard a radio broadcast describing the men who robbed the Honickmans store. Smulls and Brown fit the descriptions. The officer ordered Smulls to lie on the ground. Smulls then ran from his car but was apprehended while hiding near a service road. The police found jewelry and other stolen items from the store in the car and in Brown's possession.

The following morning police found a pistol on the shoulder of the road on which Smulls drove prior to being stopped for speeding. Bullets test fired from the pistol matched bullets recovered from the store and Stephen Honickman. Roy Post, a neighbor and business associate of Stephen Honickman, said Stephen was president of STG Electrosystem, Inc. and had worked on a military contract to design radar systems for aircraft. The family had lived in Chesterfield for at least 17 years, neighbors said. Honickman ran the jewelry store as a sideline, Post said. He had set up the store for his wife and daughter, he said. Police said they had no reports of earlier robberies. The store had just opened in December of 1990. ''I never expected anything like this to happen, '' Post said. ''It was out of the blue, a hell of a shock.''

Smulls declined to take the stand at his retrial, and he presented no testimony in his defense. The jury found Smulls guilty as charged of first degree murder, first degree assault, first degree robbery and two counts of armed criminal action. In the punishment phase, the State presented evidence of Smulls's eleven prior felony convictions for robbery, stealing and operating a vehicle without the owner's consent, as well as evidence that Smulls had committed a prior robbery in a manner similar to that employed by him in the robbery and shooting of the Honickmans.

Smulls adduced testimony from a psychologist and from several persons acquainted with or related to him in purported mitigation of punishment. Thereafter, the jury returned a sentence of death upon Smulls for his murder of Stephen Honickman, finding three statutory aggravating circumstances as a basis for consideration of capital punishment. Smulls was sentenced as a prior, persistent and class X offender to five concurrent life terms for his remaining offenses.

Missourians to Abolish the Death Penalty

Missourians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty

State v. Smulls, 71 S.W.3d 138 (Mo. 2002). (PCR)

Defendant moved for postconviction relief after he was convicted of first-degree murder and other crimes and was sentenced to death. The Circuit Court, St. Louis County, William M. Corrigan, J., denied relief, and defendant appealed. The Supreme Court, 935 S.W.2d 9, reversed and remanded in part. On remand, the trial court again denied postconviction relief, and defendant appealed. The Supreme Court, 10 S.W.3d 497, reversed. On remand, the Circuit Court, St. Louis County, Emmett O'Brien, J., overruled motion for postconviction relief, and defendant appealed. The Supreme Court, Limbaugh, C.J., held that: (1) successor judge could impartially hear postconviction relief motion; (2) evidence offered to establish racial bias of hearing judge was not admissible; and (3) trial counsel was not ineffective for failing to discover judge's alleged racial bias. Affirmed. Wolff, J., concurred and filed separate opinion. Laura Denvir Stith, J., concurred in part, dissented in part, and filed separate opinion in which White, J., concurred.

LIMBAUGH, Chief Justice.

Herbert Smulls was convicted in the Circuit Court of St. Louis County of first-degree murder and other crimes and was sentenced to death. On appeal, his convictions and sentence were affirmed, but the judgment on his Rule 29.15 post-conviction motion was reversed. State v. Smulls, 935 S.W.2d 9 (Mo. banc 1996), cert. denied, 520 U.S. 1254, 117 S.Ct. 2415, 138 L.Ed.2d 180 (1997). On remand, his post-conviction motion was overruled, but again the judgment was reversed on appeal. Smulls v. State, 10 S.W.3d 497 (Mo. banc 2000). On the latest remand, the post-conviction motion was again overruled. This Court has jurisdiction. Mo. Const. art. V, sec. 10. The judgment is affirmed.

I. Background

In 1991, Smulls was charged with first-degree murder, first-degree assault, two counts of first-degree robbery, and two counts of armed criminal action. The jury convicted Smulls of robbery but could not come to a verdict on the other charges. On retrial, Smulls was convicted on all the remaining counts. Judge William Corrigan presided at both trials. The facts surrounding the offenses, as reported in this Court's original opinion, are as follows: Stephen and Florence Honickman owned and operated a jewelry business. Typically, customers wold make an appointment to examine the jewelry for sale. In early July 1991, a person identifying himself as “Jeffrey Taylor” called the Honickmans and made an appointment to buy a diamond. “Jeffrey Taylor” was later identified as defendant. On July 22, 1991, defendant and Norman Brown went to the Honickmans' store. After viewing several diamonds, defendant and Brown left the store without making a purchase.

On the afternoon of July 27, 1991, defendant and Norman Brown followed another customer into the store. Florence Honickman was unable to show them any jewelry at that time but suggested she might be able to help them later. Defendant and Brown returned to the store that evening. After viewing some diamonds, defendant and Brown went into a hallway, purportedly to discuss the diamond prices. A short time later, Florence Honickman looked up and saw defendant aiming a pistol at her. She then ran and hid behind a door. Defendant fired three shots at her, striking her arm and side. Defendant then fired several shots at Stephen Honickman, who was struck three times. Defendant and Brown stole jewelry worn by Florence Honickman and other items in the store. After the two men left the store, Florence Honickman contacted the police. Stephen Honickman died from his wounds, and Florence Honickman suffered permanent injuries from the attack.

A short time after the robbery, police stopped defendant and Brown for speeding. While defendant was standing at the rear of his car, the police officer heard a radio broadcast describing the men who robbed the Honickmans' store. Defendant and Brown fit the descriptions. The officer ordered defendant to lie on the ground. Defendant then ran from his car but was apprehended while hiding near a service road. The police found jewelry and other stolen items from the store in the car and in Brown's possession. The following morning police found a pistol on the shoulder of the road on which defendant drove prior to being stopped for speeding. Bullets test fired from the pistol matched bullets recovered from the store and Stephen Honickman. State v. Smulls, 935 S.W.2d at 13.

In penalty phase, the jury found the existence of three statutory aggravating factors: [T]he murder of Stephen Honickman was committed while defendant was engaged in the attempted unlawful homicide of Florence Honickman; the defendant murdered Stephen Honickman for the purpose of defendant receiving money or any other thing of monetary value from Stephen Honickman; and, the murder of Stephen Honickman was committed while defendant was engaged in the perpetration of a robbery. Id. at 24. Additionally, the state introduced evidence of non-statutory aggravating circumstances including Smulls' eleven prior felony convictions. In affirming the judgment imposing the death sentence, this Court determined 1) that the sentence was not imposed under the influence of passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor, 2) that the jury's finding of the statutory aggravating circumstance was supported by the record, and 3) that the sentence was not excessive or disproportionate to similar cases.

Despite the fact that Smulls' convictions and death sentence were affirmed, this Court held that certain comments Judge Corrigan made during a Batson hearing at voir dire provided “an objective basis upon which a reasonable person could base a doubt about the racial impartiality of the trial court.” Id. at 26. These comments, coupled with allegations of pre-trial out-of-court misconduct and Judge Corrigan's status as a potential witness on those allegations, required his disqualification from Smulls' Rule 29.15 hearing. Id. at 27. Accordingly, Judge Corrigan's denial of Rule 29.15 relief was reversed, and the case was remanded for a new hearing. On remand, Judge Emmett O'Brien, another member of the St. Louis County Circuit Court, was assigned to hear the motion. Smulls filed motions to voir dire and disqualify Judge O'Brien and all other past and present St. Louis County judges. Judge O'Brien overruled those motions and denied the Rule 29.15 motion on the merits. On appeal, this Court held that statements in a deposition taken of Judge Corrigan indicated that prior to taking the case, Judge O'Brien may have discussed the case with Judge Corrigan and should possibly have recused himself from the 29.15 hearing. Smulls v. State, 10 S.W.3d at 504. This Court remanded for determination of the recusal issue, but with the following proviso: [I]f ... the hearing court finds no basis for disqualification of Judge O'Brien, the Rule 29 proceedings may be reassigned to Judge O'Brien for re-entry of his judgment. Id. at 505.

On remand, the case was assigned to Judge James Hartenbach, yet another member of the St. Louis County Circuit Court, who, after an evidentiary hearing, determined that the motion to disqualify Judge O'Brien was properly overruled. Pursuant to this Court's directive, Judge Hartenbach ordered the case reassigned to Judge O'Brien, and Judge O'Brien then re-entered his judgment overruling Smulls' Rule 29.15 motion. Smulls now appeals the determination that Judge O'Brien could properly hear the motion as well as Judge O'Brien's denial on the merits of his Rule 29.15 motion.

II. Smulls' Motion to Disqualify All St. Louis County Judges

After the 1996 remand, Smulls filed a motion to disqualify all current and former judges of the St. Louis County Circuit. That motion was overruled. The issue was briefed on the second appeal to this Court and denied. Smulls v. State, 10 S.W.3d at 499–500. Smulls now attempts to raise the issue again. However, this Court's earlier resolution of the issue on the merits is the law of the case and the issue may not be raised again. Williams v. Kimes, 25 S.W.3d 150, 153–54 (Mo. banc 2000).

III. Motion to Disqualify Judge O'Brien

A. Exclusion of Evidence

Smulls first claims that Judge Hartenbach erred in excluding certain evidence from the hearing that pertained to Judge O'Brien's alleged bias: (1) the testimony of two judges from St. Louis City expressing concern that a campaign was being waged by other judges in favor of Judge Corrigan and against the author of this Court's first opinion; (2) letters sent to this Court by other judges on Judge Corrigan's behalf asking this Court to rehear Smulls' case; and (3) certain newspaper articles from the St. Louis Post–Dispatch harshly critical of Judge Corrigan. Smulls contends the evidence is relevant because it would engender sympathy for Judge Corrigan and pressure Judge O'Brien to vindicate his fellow judge. Additionally, Smulls points to this evidence to establish that Judge O'Brien was influenced by extra-judicial factors, giving rise to an appearance of impropriety. See State v. Hunter, 840 S.W.2d 850, 866 (Mo. banc 1992).

Judge Hartenbach rejected this evidence because it was irrelevant. This Court agrees. Smulls did not show that Judge O'Brien had been exposed to any of the specific evidence in question, nor did Smulls attempt to ask Judge O'Brien about it during O'Brien's testimony at the hearing before Judge Hartenbach. Although Judge O'Brien testified that he was generally aware of newspaper articles on the issue, he could not recall the content of any of them. As for the concern from the two St. Louis City judges and the letters to this Court, Judge O'Brien testified that he was not aware of any effort by the legal community to influence this Court's opinion. Because he had no knowledge of the rejected testimony, letters, and articles, they could not have influenced him. Even if Judge O'Brien had been aware of the evidence, this alone would not require his disqualification because judges are presumed to be able to set such evidence aside in deciding a case. See State v. Taylor, 929 S.W.2d 209, 220 (Mo. banc 1996).

B. Judge O'Brien's Impartiality

Smulls next claims Judge Hartenbach erred in his determination that Judge O'Brien could impartially hear Smulls' Rule 29.15 motion on remand. The basis of the claim, from Smulls' point relied on, is that “O'Brien was with Corrigan when Corrigan condemned this Court's calling him ‘a racist’ and O'Brien may have participated in criticizing language that produced lobbying against this Court thereby creating an appearance of impropriety....” This claim arises against the backdrop of this Court's revision of its original opinion in Smulls I by deleting certain language that was highly critical of Judge Corrigan. See Smulls v. State, 10 S.W.3d at 506, n. 2 (Limbaugh, J., dissenting).

The Due Process Clause of the United States and Missouri Constitutions guarantee a criminal defendant an impartial tribunal, permitting any litigant to remove a biased judge. State v. Taylor, 929 S.W.2d at 220. Canon 3(D)(1) of the Missouri Code of Judicial Conduct, Rule 2.03, requires a judge to recuse in a proceeding where a “reasonable person would have a factual basis to doubt the judge's impartiality.” Id. This standard does not require proof of actual bias, but is an objective standard that recognizes “justice must satisfy the appearance of justice.” Liljeberg v. Health Servs. Acquisition Corp., 486 U.S. 847, 865, 108 S.Ct. 2194, 100 L.Ed.2d 855 (1986). Under this standard, a “reasonable person” is one who gives due regard to the presumption “that judges act with honesty and integrity and will not undertake to preside in a trial in which they cannot be impartial.” State v. Kinder, 942 S.W.2d 313, 321 (Mo. banc 1996). In addition, a “reasonable person” is one “who knows all that has been said and done in the presence of the judge.” Haynes v. State, 937 S.W.2d 199, 203 (Mo. banc 1996). Finally, as to due process challenges, the Supreme Court has made clear that “only in the most extreme of cases would disqualification on this basis be constitutionally required.” Aetna Life Ins. Co. v. Lavoie, 475 U.S. 813, 821, 106 S.Ct. 1580, 89 L.Ed.2d 823 (1986); see also State v. Jones, 979 S.W.2d 171, 177 (Mo. banc 1998).

In view of the allegations raised by Smulls, two cases are particularly helpful. In State v. Nunley, 923 S.W.2d 911, 918 (Mo. banc 1996), an issue presented was whether a resentencing judge from the same circuit as the original judge could “set aside his feelings for the original trial judge” and come to an independent sentencing determination. Similarly, in State v. Taylor, 929 S.W.2d at 220, the defendant argued that due to the collegial relationship between the resentencing judge and the original judge, the resentencing judge would want to “give[ ] the original judge a vote of confidence” by imposing the same sentence. In both Nunley and Taylor, this Court held that disqualification was not required absent evidence of a special relationship between the judges that might create an appearance of impropriety. Id.; Nunley, 923 S.W.2d at 918. Here, Smulls has failed to establish that such a special relationship existed.

More particularly, there is no basis for establishing that special relationship, much less an appearance of impropriety, through the allegation that O'Brien knew Corrigan condemned this Court for calling him “a racist,” and that O'Brien, himself, may have criticized this Court's original opinion. In that regard, the record of Judge O'Brien's interaction with Judge Corrigan shows the following: Judge Corrigan testified that he discussed this Court's decision with many judges on the St. Louis County Circuit bench; some of those judges criticized this Court's opinion, and he and Judge O'Brien discussed the case at some point between the issuance of this Court's original and modified opinions; however, Judge Corrigan was not sure whether his discussion with Judge O'Brien was superficial or even whether Judge O'Brien was one of the judges who criticized the opinion.

Judge O'Brien testified that he did not recall overhearing Judge Corrigan express any specific disagreement, including any specific disagreement with language used in this Court's original opinion. When asked if he and Judge Corrigan discussed the racial bias claim in Smulls, Judge O'Brien stated, “I've heard statements made by Judge Corrigan, none of which were after the modified opinion came out ... I don't think any of them dealt with specific issues within the opinion. I think it was just an overall displeasure with the opinion.” Judge O'Brien also testified that he did not have any contact with Judge Corrigan after the modified opinion was issued, and he avoided contact with anyone discussing the case because he knew it was possible that he would be assigned to hear the case. At most, he presumed the opinion “was not Judge Corrigan's favorite,” because it was critical of Judge Corrigan's fitness for the bench.

Finally, there is no evidence that Judge O'Brien “participated in criticizing language that produced lobbying against this Court,” nor, as noted, is there evidence that Judge O'Brien even knew of allegations to that effect. In fact, his only criticism on this record was that this Court's comments regarding Judge Corrigan's fitness for the bench was a matter better suited for the Commission on Retirement, Removal and Discipline. That criticism does not establish disqualifying bias, if for no other reason than that the criticism was validated when this Court deleted the comments regarding Judge Corrigan's fitness. In sum, Smulls failed to prove, either through the existence of a special relationship between Judge O'Brien and Judge Corrigan or through Judge O'Brien's comments and actions themselves, that a reasonable person would have reason to doubt Judge O'Brien's impartiality.

IV. Denial of Rule 29.15 Claims with Evidentiary Hearing

The effect of this Court's determination that Judge O'Brien could hear Smulls' Rule 29.15 hearing is that Judge O'Brien's denial on the merits is reinstated. Smulls' amended motion contained twenty-six claims. All but five were dismissed without an evidentiary hearing. An evidentiary hearing was granted on the five claims, as well as several from Smulls' pro se motion. These include ineffective assistance of counsel claims for (a) failure to move for Judge Corrigan's disqualification, (b) failure to present the results of gunshot residue tests performed on Smulls and his accomplice, (c) failure to present certain mitigating factors in penalty phase, and (d) discouraging Smulls from testifying at his second trial. All of these claims were denied. The standard of review is as follows: This Court's review is limited to determining whether the motion court clearly erred in its findings and conclusions. The findings and conclusions of the motion court are clearly erroneous only if, after a review of the entire record, the appellate court is left with the definite impression that a mistake has been made. Rousan v. State, 48 S.W.3d 576, 581 (Mo. banc 2001) (citations omitted).

A. Failure to Move for Judge Corrigan's Disqualification

The principal claim of this appeal is that Smulls' trial counsel was ineffective for failing to discover evidence of Judge Corrigan's racial bias and move for his disqualification. This claim is based essentially on the same allegations and conduct this Court considered in disqualifying Judge Corrigan from hearing the Rule 29.15 motion: 1) that prior to the case, Judge Corrigan told a racist joke to a group of judges, that judgment had been entered against him for sexual harassment, and that he discriminated against African–American defendants in the disposition of criminal cases; and 2) that during the case, he made racially insensitive comments at the Batson hearing.

Although the circumstances of the Batson hearing were reported extensively in the first Smulls opinion, they bear repeating here: The defendant noted that Ms. Sidney was the only remaining black venireperson and requested a Batson hearing. When the prosecutor stated his reasons for striking Ms. Sidney, Smulls' counsel claimed the reasons were pretextual and requested a mistrial. The court denied defendant's request. The next day, Smulls' counsel renewed the Batson challenge and stated for the record that Judge Corrigan would have been aware the victims were white and the defendant was black because he presided over the first trial. Judge Corrigan stated he did not remember who was black and who was white, but that he would accept the defendant's statement. He then reiterated his denial of the Batson claim. When the defendant again noted that Ms. Sidney was the last black venireperson, Judge Corrigan stated that he did not know what it meant to be black, that he never takes judicial notice of a person's race without direct evidence, and that it is counsel's responsibility to establish who is black and who is not. In this regard, he added: There were some dark complexioned people on this jury. I don't know if that makes them black or white. As I said, I don't know what constitutes black. Years ago they used to say one drop of blood constitutes black. I don't know what black means. Can somebody enlighten me of what black is? I don't know; I think of them as people.

1. Exclusion of Evidence

Initially, Smulls assigns error to Judge O'Brien's exclusion of certain evidence regarding Judge Corrigan's racial prejudice.

a. Unofficial Transcript

During the original 29.15 proceedings, Smulls directed a request for admissions to the prosecuting attorney seeking to establish that the defendant was black, the victims were white, and the jury panel selected was all white. Following longstanding custom and practice for non-evidentiary motion hearings in civil cases, Judge Corrigan did not provide the court's official reporter. Therefore, Smulls brought a private court reporter to the hearing who recorded and transcribed the following statements from Judge Corrigan:

This Court won't take the position that people are white or black. It is the Court's position that you can't look at people and determine what their race is .... If the lawyers don't want to ask the jurors whether the people are white or black or ask a witness if he's white or black, then I don't think that I—I can ask the parties to make that admission. At the 29.15 remand hearing before Judge O'Brien, Smulls tried to admit this transcript, arguing that the transcript demonstrates Judge Corrigan's professed inability to acknowledge a person's race. Smulls also wished to present testimony and an affidavit from his original 29.15 counsel that Judge Corrigan made statements indicating he could recognize a person's race when he so chose.

On objection by the state, Judge O'Brien properly excluded the transcript on the basis that the reporter was not the official court reporter, the reporter did not appear at the hearing to attempt to authenticate the transcript, and the transcript was not self-proving. In addition, Rule 57.03(f) states that after a deposition is taken and transcribed, it must be submitted to the deponent for his reading and signature. This was not done. Subsection (g) then provides for the signature of the officer transcribing the deposition, but in the absence of the signature of the deponent, that attestation does not guarantee the accuracy of the transcript. Coffel v. Spradley, 495 S.W.2d 735, 738 (Mo.App.1973). For all of these reasons, the transcript was inadmissible. Regardless, given the similarities between this transcript and Judge Corrigan's statements during the Batson hearing already in evidence, the transcript would have been cumulative.

b. Counsel's Race–Recognition Testimony

Smulls' former counsel attempted to testify via affidavit that during the initial Rule 29.15 hearing, Judge Corrigan referred to the woman who years before sued him for sexual discrimination as “white.” The state objected to the testimony on several grounds, including relevancy, and Judge O'Brien sustained the objection. Although the testimony was offered to show Judge Corrigan's possible bias or untruthfulness about race-recognition, it is irrelevant to show counsel's ineffectiveness for failing to discover that bias or untruthfulness. For this evidence to be relevant to that claim, the evidence must have been known to counsel or discoverable during reasonable investigation. White v. State, 939 S.W.2d 887, 895–96 (Mo. banc 1997). However, Judge Corrigan's statement was not made to counsel until the initial Rule 29.15 hearing, after trial. Smulls' counsel could not have presented this evidence in a motion to disqualify before or during trial, many months before the statement was made.

c. “ Barbecue Joke” Evidence

A Post–Dispatch article published in 1983 reported that Judge Corrigan said during a meeting of judges that, “We can't have a barbecue because we don't have a black judge to do the cooking.” Smulls claims he offered this article not to establish whether there were in fact any black judges in the St. Louis County Circuit, but to establish that Judge Corrigan was biased and that his bias was public knowledge. He claims his counsel knew or should have discovered this alleged evidence of bias, and that that contributed to counsel's ineffectiveness in failing to file a motion to disqualify Judge Corrigan. Judge O'Brien ruled the article was hearsay.

“A hearsay statement is any out-of-court statement that is used to prove the truth of the matter asserted and that depends on the veracity of the statement for its value.” Rodriguez v. Suzuki Motor Corp., 996 S.W.2d 47, 59 (Mo. banc 1999). To the extent that the article was offered to prove bias, it was inadmissible. Contrary to defendant's position, the truth of the matter asserted is not that they could not have a barbecue because there were no black judges available, but that Judge Corrigan said they could not have a barbecue because there were no black judges available. See 3 STEPHEN A. SALTZBURG, ET AL., FEDERAL RULES OF EVIDENCE MANUAL 1466 (7th ed.1998). On the other hand, the article was admissible to show that the allegation that Judge Corrigan was biased was a matter of public knowledge, and, in fact, Judge O'Brien admitted the testimony for that limited purpose. Smulls also offered the deposition testimony of Judge Campbell, who related that he personally overheard Judge Corrigan making the joke. Judge O'Brien disallowed this evidence on hearsay grounds, but the state has made no effort in its brief to defend the ruling. Assuming the testimony should have been admitted, it is much less probative of what Smulls' counsel knew or should have discovered about the matter than the newspaper article. To the extent Judge O'Brien disallowed or discounted this evidence, Smulls was not prejudiced.

d. Gender Discrimination Suit Evidence

Smulls next claims the motion court erred in excluding certain evidence related to a 1982 gender discrimination suit against Judge Corrigan that resulted in a judgment against him as reported in Goodwin v. Circuit Court of St. Louis County, 729 F.2d 541 (8th Cir.1984). The evidence consisted of: 1) an affidavit from the plaintiff in that case to the effect that Judge Corrigan accurately identified her as “white,” and 2) docket sheets reflecting that the case was heard by an African–American judge. The purported relevancy of this evidence was that it tended to show that Judge Corrigan could identify the race of a party when he so chose, and “demonstrat[ed] and prove[d] why Corrigan approximately one year later told the barbecue joke.” These matters were not pled as part of the Rule 29.15 motion, and the evidence was properly excluded for that reason. Even if those matters were properly pled, the relevancy of the evidence is tenuous, especially in light of this Court's holding in the original Smulls opinion that the gender discrimination suit in question did not disqualify Judge Corrigan from hearing gender- Batson claims. State v. Smulls, 935 S.W.2d at 16–17.

e. Exclusion of Dr. Galliher's testimony

Smulls called Dr. John Galliher, a professor of sociology who had reviewed Judge Corrigan's conduct during various trials in order to establish racial bias. Judge O'Brien excluded the evidence for a variety of reasons, ultimately concluding that the testimony was not credible. On appellate review, such a determination will rarely be overturned because a trial court is in the best position to assess the credibility and usefulness of expert testimony. Rousan v. State, 48 S.W.3d at 589. In an offer of proof, Dr. Galliher discussed at length the existence and effect of unconscious racial bias in our society, that people with such bias falsely claim not to be able to recognize race and will tell jokes to express their feelings, and that there is a correlation between gender bias and racial bias. He also commented on excerpts from Smulls' trial and several of Judge Corrigan's other cases. He concluded that “Judge Corrigan's behaviors viewed together were inconsistent with adhering to Batson's spirit and were relevant to Smulls' ability to have Batson fairly decided.”

Judge O'Brien rejected this testimony in part because it did not satisfy the Frye test that an expert opinion must be based upon a valid and accepted scientific methodology and assist the trier of fact in the determination of an issue. Callahan v. Cardinal Glennon Hosp., 863 S.W.2d 852, 860 (Mo. banc 1993); Frye v. United States, 293 F. 1013, 1014 (D.C.Cir.1923). Dr. Galliher admitted that his opinions were not based upon a random sampling of Judge Corrigan's cases or any first-hand observation of any of Judge Corrigan's cases. He testified that Judge Corrigan berates black defendants in a manner not found in cases with white defendants, but admitted that he did not look beyond the nine cases selected by Smulls (out of hundreds heard), and that the defendants were black in only six of those nine cases. The circumstances of these cases prove the point: In one case, Judge Corrigan referred to the defendant as an “animal,” but the defendant had been convicted of the brutal beating and rape of an elderly woman; in another case, Judge Corrigan called the defendant a “mad dog;” but the defendant was a serial rapist; in another case, he called the defendant a “flim-flam man,” but the defendant had been found guilty of forgery and defrauding his employer. The other cases are comparable. This is hardly proof of a pattern of racial bias. Moreover, Dr. Galliher was not able to identify any prejudice in the actual imposition of sentences and noted Judge Corrigan consistently followed the jury's recommendation. For these reasons, Judge O'Brien did not abuse his discretion in rejecting Dr. Galliher's testimony.

f. Smulls' Affidavits from Defense Attorneys

Next, Smulls complains that Judge O'Brien improperly excluded “evidence about an alleged policy of racial discrimination by St. Louis County prosecutors in voir dire.” This evidence was offered by way of affidavits from three local criminal defense lawyers and was designed to show that Smulls' counsel should have disqualified Judge Corrigan to avoid the combination of a biased prosecutor and a biased judge. This claim fails because it was determined in the initial appeal that no error occurred in deciding the merits of the Batson challenge. State v. Smulls, 935 S.W.2d at 14–16.

2. Stay of Judge O'Toole's Deposition

Smulls subpoenaed Judge Daniel O'Toole, claiming Judge O'Toole also heard Judge Corrigan tell the “barbecue joke.” At the state's request, Judge O'Brien stayed the deposition until he determined Smulls was entitled to an evidentiary hearing on the ineffective assistance of counsel claim to which the deposition related. Judge O'Brien lifted the stay on January 5, 1998, but he denied Smulls' motion for a continuance of the evidentiary hearing until the deposition could be taken. Nonetheless, he assured Smulls that additional time would be provided as necessary. Smulls scheduled the deposition for March 9, 1998, but Judge O'Toole died on that very day after an extended bout with cancer. Smulls first claims that the state had no standing to request the stay. Smulls is mistaken. The rules of civil procedure apply to Rule 29.15 motions. Rule 29.15(a). Rule 56.01(c) permits any party to file a motion for a protective order. A request for a stay order falls within that rule.

Smulls next claims that the trial court's stay of the deposition was improper because Smulls was denied access to a witness who had useful information. “Trial courts have broad discretion in administering rules of discovery, which this Court will not disturb absent an abuse of discretion.” State ex rel. Crowden v. Dandurand, 970 S.W.2d 340, 343 (Mo. banc 1998). As noted, the basis of the state's motion was that the deposition was premature and unduly burdensome until the motion court determined whether Smulls was entitled to an evidentiary hearing. The stay was proper under Rule 56.01(c), which permits the trial court to make “any order which justice requires to protect a party or person from annoyance, embarrassment, oppression, or undue burden or expense.” Smulls' citation to Rule 56.01(b)(1), which states that parties are entitled to discovery on any relevant matter, does not address the issue. Judge O'Brien's ruling was not a determination that Smulls was not entitled to the discovery. The stay was in place only until he granted an evidentiary hearing and was lifted three months prior to Judge O'Toole's death. There was no abuse of discretion. See State v. Ferguson, 20 S.W.3d 485, 504 (Mo. banc 2000).

Smulls also argues that Judge O'Brien improperly refused to continue the evidentiary hearing until Judge O'Toole could be deposed. Smulls filed a motion requesting a continuance or, “at minimum,” that the court “hold open the evidence” until the deposition could be taken. In response, Judge O'Brien denied the motion, but stated he would grant a continuance at the close of Smulls' evidence if the deposition had not yet been secured. It is well settled that “[t]he decision to grant or deny a request for a continuance ... rests within the trial court's discretion and will not be reversed absent a clear showing of abuse of discretion.” State v. Barton, 998 S.W.2d 19, 27 (Mo. banc 1999). Because the court was willing to grant a continuance if Judge O'Toole's deposition was not taken by the time Smulls rested his case, there was no abuse of discretion.

3. Admission of Judge Corrigan's Character Witnesses

Smulls objected to the relevancy of the state's presentation of five prominent criminal defense attorneys who know Judge Corrigan and testified to his reputation as being free of bias when judging cases involving African–Americans. Smulls concedes that character evidence is relevant when put in issue by the nature of the proceeding, and his real complaint seems to be that character evidence has no bearing on racial bias. However, an inquiry into a judge's alleged racial bias cannot be conducted without an inquiry into the judge's character because the presence or absence of racial bias is part of a judge's character. Where, as here, a party has opened the door by introducing evidence of bad character as manifested by racial bias, the other party may introduce evidence of good character as manifested by the lack of racial bias. Citing Clemmons v. State, 785 S.W.2d 524, 531 (Mo. banc 1990), Smulls also argues that the character and reputation witnesses were not competent to testify because their testimony relates solely to “issues the motion court must decide.” It is clear from their testimony, however, that the witnesses were testifying not as experts on a matter of law, but as persons familiar with Judge Corrigan's judicial temperament. In Clemmons, the attorneys were impermissibly testifying regarding ineffective assistance of counsel, an issue of law. Id. In contrast, the witnesses here testified regarding bias, a factual determination. See State v. Kinder, 942 S.W.2d at 334 (Mo. banc 1996); State v. Thomas, 596 S.W.2d 409, 413 (Mo. banc 1980).

4. Analysis of the Evidence of Racial Bias

To succeed on the claim that trial counsel should have disqualified Judge Corrigan on the ground of racial bias, Smulls must show that there was evidence of such disqualifying bias that his trial counsel knew of or could have discovered with a reasonable amount of investigation. White v. State, 939 S.W.2d at 895–96; State v. Twenter, 818 S.W.2d 628, 640 (Mo. banc 1991). Smulls has not done so. Most of the pre-trial, out-of-court evidence that purportedly indicated Judge Corrigan's racial bias should not be considered because it was properly excluded from evidence at the Rule 29.15 hearing before Judge O'Brien. In particular, the newspaper article about the racist joke was hearsay, and the report from Dr. Galliher on Judge Corrigan's allegedly disparate treatment of black defendants was not based on scientific study and lacked credibility otherwise.

Even if that evidence had been properly admitted, it is not evidence that trial counsel knew of or could have discovered with a reasonable amount of investigation. To uncover evidence that Judge Corrigan allegedly told a single racist joke to an informal group of judges some ten years before trial, even when the joke was reported in the newspaper, is not required as part of any reasonable investigation. This is especially true considering trial counsel has only limited resources and must necessarily be given deference as to the target and scope of such investigation. See State v. Clay, 975 S.W.2d 121, 143 (Mo. banc 1998). This conclusion applies all the more to the kind of investigation conducted by Dr. Galliher. More importantly, counsel would not know the need to conduct these investigations until the allegedly racially insensitive remarks were made during the Batson hearing after the trial had commenced. Only then did the issue of Judge Corrigan's racial prejudice clearly present itself.

Furthermore, even had counsel conducted the kind of pre-trial investigation that Smulls, in hindsight, now claims was required, the investigation would have likely turned up as much evidence that Judge Corrigan was not biased as evidence that he was biased. The five criminal defense lawyers who practice regularly before Judge Corrigan testified unequivocally that their African–American clients had been treated fairly, and even Judge Campbell, who testified that he overheard the racist joke years ago, qualified his statement by then testifying that during the many years he had served with Judge Corrigan, he had never heard of a claim or allegation of racial bias made against him. Under these circumstances, counsel cannot be faulted for failing to move for Judge Corrigan's disqualification before trial. Whether counsel should have moved to disqualify Judge Corrigan after his comments at the Batson hearing is perhaps another question, and ultimately, the issue to be resolved is whether counsel should have attempted to disqualify Judge Corrigan on the basis of his comments during the Batson hearing alone. Although this Court determined in the first Smulls opinion that those comments were racially insensitive, State v. Smulls, 935 S.W.2d at 26, Judge Corrigan's disqualification from the Rule 29.15 proceeding was required because those comments were coupled with the several allegations of pre-trial, out-of-court misconduct and the likelihood that Judge Corrigan, himself, would be a witness for those allegations. Id. at 27.

The decision to disqualify a judge is a matter of trial strategy. State v. Ayers, 911 S.W.2d 648, 652 (Mo. banc 1995); see also Wilson v. State, 626 S.W.2d 243, 248–49 (Mo. banc 1982). As with all matters of trial strategy, appellate courts are properly deferential to trial counsel's decisions. Lyons v. State, 39 S.W.3d 32, 36 (Mo. banc 2001). In that regard, it may well be that trial counsel perceived that Judge Corrigan's Batson comments were made innocuously. Further, counsel acknowledged that there was at least one important strategic reason to keep Judge Corrigan on this case: Judge Corrigan believed that the jury instruction that permitted the judge to impose the death penalty if the jury could not agree on punishment, MAI–CR3d 313.48B, was unconstitutional, and Judge Corrigan stated that he would have an extremely difficult time imposing the death penalty if the jury did not. On this record, counsel cannot be convicted of being ineffective for failing to disqualify Judge Corrigan.

Finally, hindsight shows that the decision not to disqualify Judge Corrigan did not result in prejudice. Smulls cannot point to any judicial decision that evidences Judge Corrigan's alleged bias or in which Judge Corrigan's alleged bias produced an unjust result. This Court expressed concern in its 1996 decision that Judge Corrigan's refusal to acknowledge race raises “serious questions about his willingness to do what Batson requires,” Smulls, 935 S.W.2d at 26, and this Court wrote: “The trial court cannot add subtle burdens to the Batson process by refusing to take note of race where trial counsel properly places it at issue.” Id. However, a careful review of the record shows that Smulls' Batson challenge was heard not once, but twice, and at the first hearing, Judge Corrigan did not dispute that Ms. Sidney was African–American. Indeed, the controversy did not arise until the second hearing on the second day when Judge Corrigan's memory had faded and Ms. Sidney and the other jurors who were not selected were no longer present. Ultimately, this Court determined in the original appeal that the prosecutor's peremptory strike of Ms. Sidney was not pretextual and that Judge Corrigan correctly denied the Batson challenge. Id. at 14–16. Smulls advances no evidence indicating otherwise. The simple fact is that Judge Corrigan's skepticism at Smulls' Batson hearing, whether honest or obstinate, did not prevent Smulls' claims from being heard and did not prove that the outcome of that hearing or the trial as a whole was the product of the judge's bias.

B. Disqualification Because of Retention Vote

Smulls next claims that his counsel was ineffective for failing to have Judge Corrigan disqualified because Judge Corrigan was worried about his upcoming retention vote in the 1992 general election. Smulls explains that given that concern, Judge Corrigan would be unwilling to consider a life sentence instead of the death penalty because a willingness to consider a life sentence might erode support at the polls. This claim is frivolous. The 1992 general election was held before Smulls' trial.

C. Failure to Present Gunshot Residue Evidence

Gunshot residue tests were performed on Smulls and his accomplice. No residue was detected on Smulls, and the test on his accomplice was inconclusive. During the first trial, the state's expert, Dr. Rothove, was unavailable, and the parties agreed to a short stipulation regarding the test results. At the second trial, Smulls' counsel subpoenaed Rothove, but did not call him, having just learned that he would not support the theory that the accomplice fired the shots. As we understand it, Smulls' claim is that counsel did not interview Rothove in time to adjust strategy and that counsel was ineffective for failing to present the stipulation. Smulls now concedes that the stipulation was not available on retrial and claims his counsel should have obtained an independent expert. This claim was not pled. Nevertheless, Smulls attempted to present the testimony of Donald Smith, a criminologist. Judge O'Brien gratuitously reviewed the claim, but rejected Smith's testimony because Smith could not identify which of the two suspects was the shooter, did not sufficiently duplicate the state's test, and was not otherwise credible.

Smulls must establish that his counsel was ineffective in failing to obtain an independent expert and that it is reasonably probable that the deficiency affected the outcome. White v. State, 939 S.W.2d at 895–96; State v. Twenter, 818 S.W.2d at 640. Smith testified that either one of the defendants could have been the shooter. However, in conducting his own tests, Smith did not attempt to obtain the same weapon used in the crime, and he admitted that different weapons of the same make and model can “kick off” different residues. In addition, Smith was not certain he and the state used the same machine to conduct the tests. He also was unaware that Smulls struggled in wet grass with the police and continuously wiped his hands, which can remove residue. See Wainwright v. Lockhart, 80 F.3d 1226, 1230 (8th Cir.1996). Based upon these factors it cannot be said that it was clear error for the motion court to find Smith's evidence lacking in credibility. See State v. Hall, 982 S.W.2d 675, 687–88 (Mo. banc 1998); Wainwright, 80 F.3d at 1230

D. Failure to Present Mitigating Circumstances

Smulls claims Judge O'Brien clearly erred in denying his claim that his counsel was ineffective for failing to interview and present certain mitigating witnesses during penalty phase. These witnesses would allegedly have testified that he was nonviolent, amicable, abandoned at childhood, impoverished, cared for his children, and that he was helpful to friends and relatives.

While counsel is required to investigate possible mitigating circumstances, Nunley, 923 S.W.2d at 924, there is no absolute duty to present mitigating evidence. State v. Shurn, 866 S.W.2d 447, 472 (Mo. banc 1993). Furthermore, “[c]ounsel is not ineffective for not putting on cumulative evidence.” Skillicorn v. State, 22 S.W.3d 678, 683 (Mo. banc 2000). Smulls presented five witnesses during the penalty phase: Dr. Wells Hively, a psychologist; Smulls' pastor, who had known him since he was a child; a supervisor and a corrections officer at the jail where Smulls was incarcerated; and Smulls' adopted father, who had raised him since he was a year and a half old. Dr. Hively explained that Smulls is depressed, has a dependent personality, and is not violent unless he is coerced. The pastor testified that Smulls is polite, respectful and not violent. The corrections supervisor and guard testified that he was a good worker and that he did not cause trouble. His father testified that Smulls was abandoned as a child and did not finish high school, and that he still cared for Smulls as he would his own blood.

Most of the witnesses and testimony Smulls claims his counsel should have presented would be cumulative of testimony that had already been presented. In addition, the motion court, which is in the best position to evaluate credibility, found that a number of these witnesses were not credible. They include Randy Edwards and Dennis Brown, who both arrived in court to testify with a list of typed questions with parenthetical answers; Crispin Smith, who had a “close relationship” with Smulls but supposedly did not know he was on parole; Maggie Cain, who knew Smulls only from church; and Patricia Lee, who knew him only in passing. The motion court's findings on this matter were not clearly erroneous. Rousan v. State, 48 S.W.3d at 589. Furthermore, in light of the aggravating factors found by the jury, Smulls has not shown that the additional mitigating testimony would have produced a different result had it been presented at trial.

E. Smulls' Decision Not to Testify

Smulls claims his counsel was ineffective for not advising him to testify. Smulls testified at his first trial, and the jury could not reach a verdict on the murder count. He claims this gives rise to a “reasonable probability” that he would not have been convicted had he testified at his second trial. See Rousan v. State, 48 S.W.3d at 581–82. “Advice of counsel that a defendant not testify, without more, is not incompetent when it might be considered sound trial strategy.” State v. Powell, 798 S.W.2d 709, 718 (Mo. banc 1990). Smulls has an extensive criminal history, which was a subject of cross-examination during the first trial and a probable subject of cross-examination during the second trial. This would have undercut his theory that he was not the ringleader of the robbery. In addition, the trial court discussed with him his decision not to testify. The argument that his testimony at the first trial caused the hung jury is speculative, and he has not demonstrated that his counsel's decision was anything other than sound trial strategy. See State v. Chambers, 891 S.W.2d 93, 112 (Mo. banc 1994).

V. Denial of Rule 29.15 Claims Without an Evidentiary Hearing

In post-conviction relief motions, [a]n appellant is entitled to an evidentiary hearing only if his motion meets three requirements: (1) the motion must allege facts, not conclusions, warranting relief; (2) the facts alleged must raise matters not refuted by the files and records in the case; and (3) the matters of which movant complains must have resulted in prejudice. Morrow v. State, 21 S.W.3d 819, 823 (Mo.2000).

A. Prosecutor's Motive to Seek the Death Penalty

Smulls claims his trial counsel was ineffective for failing to investigate and challenge the prosecutor's motive to seek the death penalty. Again, to establish ineffective assistance, Smulls must describe the information his attorney failed to discover, allege that a reasonable investigation would have uncovered the information, and prove the information would have aided his position. White v. State, 939 S.W.2d at 895–96; State v. Twenter, 818 S.W.2d at 640. Further, “[t]o show that the prosecutor sought the death penalty for racially discriminatory reasons,” defendant must prove that the prosecutor's decision had “a discriminatory effect” on defendant and that the decision was “motivated by a discriminatory purpose.” Morrow v. State, 21 S.W.3d at 825. Finally, movant “must offer clear proof of discrimination in his own case.” State v. Brooks, 960 S.W.2d at 499.

Smulls' motion alleged that: (1) he is an economically disadvantaged African–American, (2) his victims were Caucasian and the crime occurred in an affluent Caucasian suburb, (3) evidence would be presented that in factually similar homicide cases with Caucasian defendants the state did not seek the death penalty, (4) the death penalty was sought in his case because he is African–American, (5) reasonably competent counsel would have investigated and raised this matter, and (6) he was prejudiced. Smulls claims that fear of African–American males because they are “causally linked to crime” motivated the prosecutor to seek the death penalty. Smulls' evidence in support of these allegations consisted of a “Task Force Report on the Status of the African–American Male in Missouri” attached to his pleadings, which purportedly showed in capital cases a “glaring racial difference” that “results from the discretionary decisions of prosecutors.” This evidence fails to prove purposeful discrimination specific to his case. Morrow v. State, 21 S.W.3d at 825. Furthermore, where, as here, the facts of the case strongly support the existence of statutory aggravating factors, not to mention Smulls' extensive criminal history, the likely motivation for seeking the death penalty is the strength of the prosecution's case. See id.; State v. Brooks, 960 S.W.2d at 499–500. The record does not warrant an evidentiary hearing, much less a finding of ineffective assistance of counsel.

Smulls also takes issue with the motion court's refusal to allow interrogatories on this claim. Because the determination to deny the claim without an evidentiary hearing was properly made solely on “the motion and the files and records of the case,” discovery before the determination of which claims warrant an evidentiary hearing would be premature. See State v. Ferguson, 20 S.W.3d at 504. Discovery after denial of such a claim is unwarranted because the discovery is no longer “relevant to the subject matter involved in the pending action.” Id.

B. Dr. Hively's Testimony

Smulls claims his counsel erred in calling Dr. Wells Hively during penalty phase because Dr. Hively was not the author of Smulls' psychological report, which was prepared as evidence in mitigation. The expert who prepared the report was unavailable, and Dr. Hively, who worked with the expert on the case, was called as a replacement. Counsel cannot be faulted because she had little choice but to call another witness familiar with the report. In addition, trial counsel's testimony to the contrary notwithstanding, it is unlikely that Smulls suffered prejudice from counsel's choice to present a different expert than the one who prepared the report. Doctor Hively testified that his entire office, including himself, was involved in the preparation of the report, that he examined Smulls four times, and that his opinion was based upon those examinations as well as the results of psychological tests and police reports. The motion court's denial of this claim was not clearly erroneous. Smulls also alleges that instead of calling Dr. Hively, his counsel should have called a “comprehensive mental health expert.” Counsel is not ineffective for failing to shop around for additional experts. Lyons v. State, 39 S.W.3d at 41.

C. Penalty Phase Opening Statement

Smulls claims his counsel was ineffective for commenting, during opening statement in penalty phase, that Smulls could not find a job because of a disability and turned to a life of crime as an easy way out. Smulls' eleven prior felony convictions were admissible to impeach his credibility if he took the stand and admissible regardless as an aggravating factor in penalty phase. It is a common and proper defense strategy to mention convictions first in order to soften the blow. See Richardson v. State, 577 S.W.2d 653, 655 (Mo. banc 1979). Counsel was not ineffective in this regard.

D. Failure to Object to Instructions

Smulls claims his counsel was ineffective for failing to object to allegedly confusing punishment phase instructions and to present survey data on the accuracy of juror comprehension. Smulls concedes that this Court has recently rejected such a claim in State v. Deck, 994 S.W.2d 527, 542–43 (Mo. banc 1999). The claim is denied on that basis.

E. Voir Dire

Smulls claims his counsel was ineffective for failing to object when the trial court stated that, “theoretically” speaking, the defendant does not have the burden to prove that he should not be put to death. The record reflects an extensive dialogue with the juror in question, during which the trial court made it clear that the state bore the burden. Taken in context, and considering the person did not serve on the jury, the court's explanation did not misallocate the burden, and any claim the jury was tainted is speculative.

VI. Claims Denied on Direct Appeal

Smulls' motion also raises a number of ineffective assistance of counsel claims in which the underlying issues were denied by this court on direct appeal: (1) failure to prove the prosecutor's reasons for striking Ms. Sidney were pretextual, State v. Smulls, 935 S.W.2d at 14–16; (2) failure to move to quash the entire venire because a juror who had been stricken was permitted to stay and answer questions, id. at 19; (3) failure to present as a mitigating factor that the accomplice admitted to shooting the victims, id. at 20–21; (4) failing to move for a mistrial when the jury expressed concern for its safety in notes sent to the court during guilt phase deliberations, id. at 22. Counsel cannot be ineffective for failing to raise non-meritorious claims.

VII. Conclusion