21st murderer executed in U.S. in 1996

334th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Indiana in 1996

4th murderer executed in Indiana since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

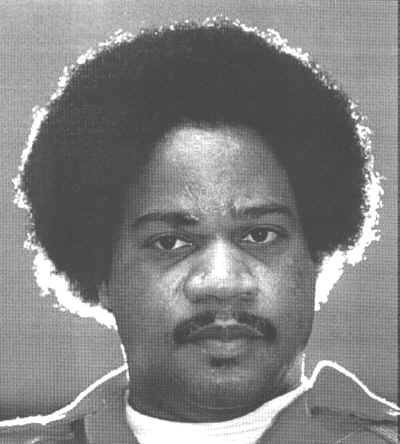

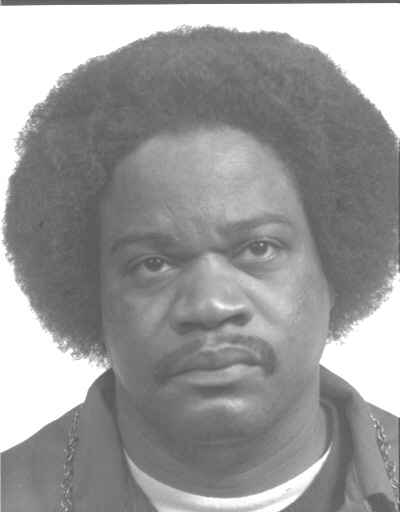

Tommie J. Smith B / M / 26 - 42 |

Jack Ohrberg W / M / 44 |

Summary:

On December 11, 1980 at 5:30 a.m., Indianapolis Police Sergeant Jack Ohrberg and other officers went to 3544 North Oxford in Indianapolis attempting to serve papers on persons believed to be at that location. Ohrberg banged on the door several times and identified himself as a police officer. Two other officers on the front porch were in uniform. After the next door neighbor told officers that there was noise from inside the apartment, Ohrberg crouched and pounded with his shoulder on the door, which began to open. Officers saw furniture blocking the door, and saw 2 or 3 muzzle flashes from two different locations inside. Ohrberg was shot and collapsed on the porch. Officers took cover and saw a man come out onto the porch, point a rifle, and fire at least 2 additional shots into Ohrberg. Officers took cover and returned fire. Shots continued to come from inside the house. After a few minutes, Gregory Resnover came out, threw down an AR-15 rifle and surrendered. Earl Resnover followed, laying down an AR-15 and a pistol. Ohrberg's business card was found in Earl's wallet. Two women then came out, leaving wounded Smith inside. An AR-15 which was recovered next to Smith was found to be the murder weapon. An arsenal of weapons and ammunition was recovered inside the apartment. Accomplice Resnover was also sentenced to death and executed December 8, 1994.

Citations:

Smith v. State, 465 N.E.2d 1105 (Ind. July 24, 1984) (Direct Appeal).

Smith v. Indiana, 116 S. Ct. 2581 (1996) (Cert. denied).

Smith v. State, 516 N.E.2d 1055 (Ind. 1987) (PCR.

Smith v. State, 613 N.E.2d 412 (Ind. 1993) (PCR).

Smith v. Indiana, 114 S. Ct. 1634 (1994) (Cert. denied).

Smith v. Farley, 873 F.Supp. 1199 (N.D.Ind. 1994) (Habeas).

Smith v. Farley, 59 F.3d 659 (7th Cir. 1995) (Habeas).

Smith v. Indiana, 116 S. Ct. 935 (1995) (Cert. denied).

Smith v. Parke, 116 S. Ct. 2518 (1996) (Stay).

Smith v. Parke, 116 S.Ct. 2581 (1996) (Habeas).

Internet Sources:

Clark County Prosecuting Attorney (Tommie J. Smith)

EXECUTED BY LETHAL INJECTION 07-18-96 1:23 AMDOB: 02-06-1954

DOC#: 4330 Black Male

Marion County Superior Court

Special Judge Jeffrey V. Boles

Originally venued to Hendricks County.

By agreement, returned to Marion County, with Hendricks Circuit Judge Jeffrey V. Boles presiding)

Prosecutor: J. Gregory Garrison, David E. Cook (Stephen Goldsmith)

Defense Attorney: Richard R. Plath

Date of Murder: December 11, 1980

Victim(s): Jack Ohrberg W/M/44 (Indianapolis Police Officer)

Method of Murder: shooting with AR-15 rifle

Conviction: Murder, Conspiracy to Commit Murder (Class A Felony)

Sentencing: July 23, 1981 (Death Sentence, 50 years imprisonment)

Aggravating Circumstances: law enforcement victim

Mitigating Circumstances: None

Direct Appeal:

Smith v. State, 465 N.E.2d 1105 (Ind. July 24, 1984)

Conviction Affirmed 5-0 DP Affirmed 5-0

Pivarnik Opinion; Hunter, Debruler, Givan, Prentice concur.

Smith v. Indiana, 116 S. Ct. 2581 (1996) (Cert. denied)

PCR:

Smith v. State, 516 N.E.2d 1055 (Ind. 1987)

(Appeal of PCR denial by Judge Patricia J. Gifford)

Conviction Affirmed 5-0 DP Affirmed 5-0

Pivarnik Opinion; Shepard, Debruler, Givan, Dickson concur.

Smith v. State, 613 N.E.2d 412 (Ind. 1993)

(Appeal of 2nd PCR summary dismissal by Judge Patricia J. Gifford)

Conviction Affirmed 5-0 DP Affirmed 5-0

Krahulik Opinion; Shepard, Givan, Dickson, Debruler concur.

Smith v. Indiana, 114 S. Ct. 1634 (1994) (Cert. denied)

Habeas:

Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus filed 11-25-88 in U.S. District Court, Northern District of Indiana.

Writ denied 10-31-94 by U.S. District Court Judge Allen Sharp.

Smith v. Farley, 873 F.Supp. 1199 (N.D.Ind. 1994) (Petition for Habeas Writ Denied)

Smith v. Farley, 59 F.3d 659 (7th Cir. 1995) (Appeal of Denial of Habeas Writ)

Affirmed 3-0; Judge Richard A. Posner, Judge William J. Bauer, Judge Joel M. Flaum.

Smith v. Indiana, 116 S. Ct. 935 (1995) (Cert. denied)

Smith v. Parke, 116 S. Ct. 2518 (1996)

(Stay of execution granted until disposition of Writ of Certiorari)

Smith v. Parke, 116 S.Ct. 2581 (1996)

(Petition for Writ of Certiorari dismissed; Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus denied)

Smith v. Indiana, 117 S.Ct. 1 (1996)

(Application for Stay denied)

Smith v. Farley, 949 F.Supp. 680 (N.D.Ind. 1996). (Approval of $32,316.91 claim at $125 per hour for attorneys fees in habeas action to Professor F. Thomas Schornhorst of Indiana University School of Law.)

SMITH WAS EXECUTED BY LETHAL INJECTION ON 07-19-96 AT 1:23 AM EST. HE WAS THE 74TH CONVICTED MURDERER EXECUTED IN INDIANA SINCE 1900, AND THE 4TH SINCE THE DEATH PENALTY WAS REINSTATED IN 1977. HE WAS THE FIRST CONVICTED MURDERER EXECUTED IN INDIANA BY LETHAL INJECTION.

July 3, 1996

Dear Governor Bayh,

Fifteen years ago Tommie Smith was convicted of murder and sentenced to death because the state convinced a judge and a jury that as Sgt. Ohrberg was lying wounded and helpless on the porch, Tommie Smith then leaned from the doorway and deliberately pumped two shots into his back at point-blank range in cold blood. Deputy Prosecutor Garrison urged the jury to convict Smith of murder in the following language:

Now, what about Tommie. Tommie signed his name for us and we owe him a debt of gratitude. Because Tommie couldn't be satisfied with tearing Jack's guts apart [with] that first shot. Oh, no. He's got to play super-fly [sic] and come out here and blow holes in a man who is lying dying on the sidewalk.

Stephen Goldsmith, who was the Prosecutor, cited this "execution on the porch" as the principal reason for asking for the death penalty. (In fact, Goldsmith was being less than forthcoming, because he carefully avoided the physical evidence, no doubt recognizing that it would tear his case apart.)

Years later evidence came to light that shows the theory of the execution on the porch to be IMPOSSIBLE. This evidence was the physical evidence, available all along, but not examined until the post-conviction hearing. For various technical reasons, NO COURT HAS EVER EXAMINED THIS PHYSICAL EVIDENCE THAT SHOWS THE THEORY WRONG.

The Parole Board has been discredited by Chairman Raymond Justak's June 13th letter to the editor of the Indianapolis Star. In that letter he justified Smith's pending execution by a totally new theory: that Smith fired eight shots before Ohrberg fired his single shot. THAT THEORY IS INCOMPATIBLE WITH THE THEORY ON WHICH SMITH WAS CONVICTED AND SENTENCED TO DEATH. Thus, the Parole Board does not believe the theory of the "execution on the porch" and was therefore bound to recommend clemency. What is even more astonishing, however, is that Justak's new theory shows that the Parole Board DID NOT UNDERSTAND THE FACTS OF THE CASE, for the record does not show whether Ohrberg fired first or Smith fired first, and there is evidence that shows that it is impossible that Smith fired eight shots before Ohrberg fired. [N.b., Justak's letter claimed that the record shows that Smith fired first.] The Parole Board has shown itself biassed and incapable of evaluating the physical evidence or the facts in the case.

I know that you want Tommie Smith's factual claims addressed fairly. I

know that you do not want Indiana to unjustly execute a man. Therefore you

should order the Indiana State Police to evaluate the physical evidence and

the facts in the case. They have earned a reputation for competence,

integrity, and professionalism.

Tekla Lewin, Visiting Professor of Mathematics, Earlham College

Tommie J. Smith, also known as Ziyon I Yisrayah, initially filed a petition

for clemency from his capital sentence imposed for the murder of

Detective Sergeant Jack Ohrberg in 1980. Mr. Smith subsequently

amended his request, asking only that he receive a reprieve from his

scheduled execution pending re-examination of some of the facts

surrounding his case. Pursuant to his request, I have carefully

considered whether the delay he seeks

is necessary to ensure that justice is preserved and fairness is

observed.

1. The Facts. Tommie J. Smith is a multiple murderer and a

career criminal. This case began over fifteen years ago, when Smith

and his confederate, Gregory Resnover, ambushed Detective Sergeant

Ohrberg as he attempted to serve arrest warrants on Smith, Gregory

Resnover and Earl Resnover on charges of murder and armed robbery.

In December of 1980, Smith was already well known to the

Indianapolis, Police Department, for he had been in and out of juvenile

and adult correctional facilities continuously since the age of fifteen.

Smith had been under investigation by Ohrberg for several months in

connection with at least two major crimes in Indianapolis: a murder in the

course of an armed robbery of American Fletcher National Bank and the

murder and armed robbery of a Brink's guard, William Sieg, Sr. (Smith

was later tried and convicted for murdering and robbing Sieg). Evidence

at trial indicated Smith had contemplated killing Ohrberg to prevent him

from pursuing his investigation. Referring to Ohrberg, Smith told a friend

a few days before the murder that "[i]f the dude keep on goin' at it like

he's goin' at it he's gonna come up missin'."

At 5:30 a.m. on December 11, 1980, Ohrberg and several other

police officers went to a duplex where they believed Smith to be staying.

Ohrberg pounded on the door, with both his fist and his police radio, and

shouted #police,# but no one answered. Smith told a newspaper reporter

(who testified at trial) that Smith was sleeping in the front room and was

awakened by the pounding on the door.

Meanwhile, Ohrberg went to the other side of the duplex to ask a

neighbor whether anyone was inside the home where Smith was

suspected to be. When the neighbor confirmed that on the night before

she had heard people next door, Ohrberg decided to return and forcibly

enter the house. At this point, the neighbor heard "runnin" and thumpin"

or something." Most important, she heard a male voice from inside shout

"It's the mother f---in" police."

Ohrberg attempted to open the door, but initially was unable to do

so because it had been barricaded with a piece of furniture. Waiting on

the other side of the door were Smith and Gregory Resnover, each

armed with AR-15 semiautomatic military assault rifles. After Ohrberg

managed to pry the door partially open with his shoulder, Smith and

Resnover opened fire on him.

Smith hit Ohrberg in the abdomen, causing him to collapse on the

porch. The other officers scrambled for cover as several more rounds

of gunfire were directed toward them out the door and though the

windows, shattering the glass. When the gunfire subsided, a black male

matching Smith's description leaned out the door onto the porch and,

according to testimony, appeared to fire more shots at Ohrberg's

downed body.

In all, at least sixteen rounds were fired at the police -- eight

from

Smith's weapon and eight from Resnover's -- and one of the weapons

was reloaded. Ohrberg was struck three times, once in the abdomen

and twice in his left side. At some point during the melee, Ohrberg

managed to fire one shot, which wounded Smith in his leg. According to

Smith, he was hit as he retreated inside the house after stepping onto

the porch.

2. The Legal Proceeding. Smith and Resnover were charged

with the murder of Ohrberg and conspiracy to murder Ohrberg. They

were tried together in Marion Superior Court before a special judge, the

Honorable Jeffrey Boles. Following the trial limited to the issue of the

defendants' guilt, the jury convicted Smith and Resnover on both

charges. As required by law, the court then conducted a separate

proceeding on whether the death penalty should be imposed. Rather

than requesting mercy from the jury and the court, Smith and Resnover

boycotted the proceeding, choosing not to testify on their own behalf.

The jury unanimously recommended that Smith and Resnover be

sentenced to death. Accepting this recommendation, Judge Boles

imposed the death penalty on each.

Over the next fifteen years, Smith's case has been the subject of

searching review by our courts, state and federal. The Indiana Supreme

court reviewed Smith's case at least four times, the United States

Supreme Court reviewed it five times, the United States Court of Appeals

for the Seventh Circuit reviewed it twice, the trial court reviewed it twice

and the federal district court reviewed it as well. Each of these courts

found, without exception, that Smith's trial was fair and his sentence

appropriate. A summary of the legal prceedings is appended to this

statement.

3. Proceedings Before the Parole Board. The Parole Board,

like the courts, thoroughly reviewed Smith's case. Indeed, the Board did

so twice. The Board examined the record of the original trial, the records

of the post-conviction proceedings, the orders and written opinions of

the courts, and the voluminous and well-presented materials submitted

by Smith's attorneys in connection with the clemency

proceedings. The Board also reviewed matters never considered by the

courts. For instance, the Board considered oral testimony from Smith's

family and friends members of the community, and experts in criminal law

and death penalty litigation. The Board heard testimony from four of

Smith's fellow death-row inmates, who discussed Smith's character and

conduct while he has been incarcerated. Of particular significance, on

two different occasions the Board heard the testimony of Smith himself,

something neither the jury nor any court had the opportunity to evaluate.

Having examined this information, the Board concluded unanimously that

a reprieve of Smith's execution was unwarranted and clemency was

unjustified.

4. The Governor's Deliberation. On two prior occasions, I

have elaborated the principles that guide my discretion in considering

clemency petitions in capital cases. I developed these principles through

many hours of reflection, recognizing that an error of judgment in this

area is without remedy. There is no issue which, as governor, I have

devoted more attention to -- intellectual, moral and spiritual -- than the

disposition of these petitions. Still, each petition raises its own

complexities. Smith's petition is no exception.

Because I have previously explained in detail my approach to

clemency petitions in capital cases, I will briefly summarize that approach

here. In my view, the principal purpose of clemency is to prevent a

gross miscarriage of justice. My first foucs, therefore, is to ensure that

the State does not execute an individual who is innocent of the crime or

undeserving of the penalty. To that end, I look for new, pivotal evidence

proving actual innocence. Second, I examine whether some fundamental

defect in the legal proceedings prevented meaningful judicial review.

The judiciary, not the executive, provides the forum uniquely well suited

to ensuring that an inmate is accorded the full range of rights --

substantive and procedural -- that, in the end, provide us with

confidence in the outcome. Third, I look to whether the petitioner has

engaged in some act of extraordinary moral virtue that would cause the

community and the state to conclude that captial sentence would no

longer be just. Finally, I am also mindful of the nature and circumstances

of the crime, the petitioner's criminal history, his institutional conduct

and

his degree of remorse. What I do not believe is appropriate is for me

simply to serve as another layer of judicial-type review, retrying the case

or reweighing contested facts. With these principles as my guide, I have

reviewed Smith's petition.

5. Smith's Claims and Request for Relief. Smith stresses

he is not seeking clemency. Rather, he is asking that his execution be

delayed so that another fact finder, either an executive body or a judicial

body, may review evidence he claims has been ignored by, or has never

been presented to, the courts. According to Smith, the ballistic evidence,

the testimony of the officers, and the autopsy report demonstrate that

Smith did not shoot Ohrberg in his back as he laid wounded on the porch.

The "execution on the porch," as Smith calls it, is an impossibility in his

view, yet the prosecution relied on that version of events to obtain a

capital sentence. Had the jury and trial judge known, Smith argues, that

the "execution on the porch" did not occur, Smith may have been

acquitted or at least may have avoided the death sentence, particularly

when combined with his allegation that he believed Ohrberg was an

intruder whom he shot in self-defense, not a police officer attempting to

arrest him. Thus, Smith asserts that if given another opportunity to

establish this evidence regarding the events on the porch, it would

constitute new, pivotal evidence demonstrating his innocence. As Smith

himself stated, he "is not asking for mercy, only fairness."

I find Smith's contentions uncompelling for two independent

reasons. First, Smith's factual assertions, even if true, do not establish

he is innocent of murder. Indeed, facts Smith does not contest point

decidedly toward his guilt. The record demonstrates that Smith opened

fire and, at a minimum, shot Ohrberg in the abdomen as Ohrberg forced

open the barricaded door -- all facts Smith himself concedes. According

to the trial testimony of the forensic pathologist who performed the

autopsy on Ohrberg, that particular bullet "perforated Ohrberg's

abdominal wall and external iliac artery and completely severed his iliac

vein...there were 600 milliliters of blood in Ohrberg's abdominal cavity."

The record also demonstrates that Smith knew the individual pounding on

the door was a police officer. The neighbor testified she heard a male

inside the house yell "It's the mother f---in" police. And Smith himself

admitted he was awakened by Ohrberg's pounding. Wholly apart from

the facts surrounding the "execution on the porch," overwhelming and

irrefutable evidence shows that Smith knowingly and intentionally

ambushed a police officer who was attempting to arrest him. Smith is

left to argue that he intended to mortally wound Ohrberg only once, not

three times. Thus, Smith's contentions, whatever their merit, fail to

establish that Smith's execution would result in a gross miscarriage of

justice.

Second, Smith's contentions not only fail to establish his

innocence, they are not even new. Smith's factual assertions regarding

the events on the porch have been afforded exhaustive review by the

courts. Smith presented these contentions, in meticulous detail, to the

trial court, to the federal district court, to the federal court of appeals,

twice to the Indiana Supreme Court, and twice to the United States

Supreme Court. In other words, every court that could have reviewed

these contentions has done so. Each of these courts concluded that

these contentions do not cast doubt on the fairness of the proceedings

or the reliability of the outcome. Contrary to Smith's claims, his

arguments were not ignored, mischaracterized or misrepresented by the

courts. His arguments were fully considered and, in the end, rejected.

Given that Smith's contentions are neither new nor exculpatory, I

do not believe that another delay in order to allow another fact finder to

conduct another review of evidence that, as the Seventh Circuit

explained, is "contestable and peripheral" is necessary to ensure justice.

Smith v. Farley, 59 F.3d 659, 667 (7th Cir. 1995).

6. Smith's Moral Character and Conduct. In the past, I have

explained that even where a petitioner's guilt is clear and the legal

proceedings were fair, exceptional circumstances relating to the

petitioner's moral character or conduct may make clemency appropriate.

I have used as a hypothetical example of such exceptional

circumstances an inmate saving the life of a prison guard.

In his hearing conducted at the prison, one of Smith' fellow

inmates, Charles E. Roche, testified that he had attacked a prison guard

with the intent to kill him, and would have done so but for the intervention

of Smith. The records of the Department of Correction, however, which

include Roche's contemporaneous account of the event and the

statements of several witnesses, make no mention of Smith, much less

his claim that he saved the life of the guard. In addition, Roche's account

of the event before the Parole Board is at considerable variance with his

statement at the time of the incident. Finally, Smith's version before the

Parole Board was also at odds with that of Roche. According to Smith,

prior to the attack, Roche informed Smith of his intent to kill the guard.

Smith asserts that he recommended to Roche that he merely stab the

guard, but that he not kill him. Even if Smith's assertions were true, his

conduct would not provide a basis for a reprieve.

Since Smith has raised the issue of his conduct and character, I

believe it appropriate for me to note that Smith has not demonstrated

remorse for his actions nor regret to the families of his victims. Before

the Parole Board, Smith described himself as a victim of an unfair judicial

process. Smith also suggested to the Parole Board that the only reason

his home contained an arsenal of military assault weapons was because

he was a sportsman, interested in rabbit hunting. Thus, Smith refuses to

acknowledge he was prepared to and did engage in heinously criminal

conduct which has caused suffering that is immeasurable and continual.

7. The Role of Clemency or Reprieve. In reviewing Smith's

request for a reprieve, I have attempted to consider not only Smith's

interests, but also those of his victims and the community. Over the past

fifteen years, Smith's crimes have received special attention by the

public, and with good reason, for it is sobering when our law

enforcement officers -- those on which we rely to keep us safe -- are

themselves unsafe. This is a crime that disturbs our confidence that we

can live as a civilized people under the rule of law.

The families of Sergeant Ohrberg and William Sieg will never be

made whole, and we do not deceive ourselves that the execution of

Smith will compensate for their loss. But, his execution is just. And that

is all we can expect. On earth, justice is an imperfect remedy for an

imperfect people. While it is my deepest hope that the closure of this

case will offer some comfort to the Ohrbergs and Seigs, some renewal

of their faith in the criminal justice process for which Sergeant Ohrberg

selflessly gave his life, I know that complete healing must wait.

As governor, I have attempted, to the best of my ability, to

discharge the responsibilities vested in me by the citizens of Indiana, to

uphold the Constitution and to faithfully execute the laws of this State.

That is what I have endeavored to do here, reinforced by the many

police officers, prosecutors, judges, and members of the Parole Board,

all of whom have likewise been guided by our Constitution and law, and

with His presence, I reach my decision.

Smith's petition for a reprieve is denied.

Evan Bayh

July 15, 1996

APPENDIX

Judicial Proceedings in the Tommie J. Smith Case

1. On June 29, 1981, Tommie J. Smith was convicted by a jury in

Marion Superior Court of murder and conspiracy to commit murder. On

June 30, 1981, the jury returned a sentence recommendation of death.

On July 23, 1981, the Honorable Jeffrey Boles sentenced Smith to death

for murder, and 50 years in prison for conspiracy to commit murder. On

July 24, 1981, Judge Boles issued a warrant for Smith's execution to

take place on November 1, 1981.

2. On September 21, 1981, Smith filed a Motion to Correct Errors.

After a hearing on October 22, 1981, the trial court denied the motion.

3. On October 23, 1981, Judge Boles issued an order staying the

execution previously set for November 1, 1981.

4. On November 25, 1981, Smith filed a petition to stay the

execution set for December 1, 1981. Judge Boles granted the stay on

November 30, 1981, pending perfection of an appeal to the Indiana

Supreme Court.

5. On July 24, 1984, the Indiana Supreme Court unanimously

affirmed Smith's conviction and sentence. Smith v. State, 465 N.E.2d

1105 (Ind. 1984).

6. On October 12, 19984, the Indiana Supreme Court stayed the

execution previously set for October 18, 1984, by Judge Boles. On

December 4, 1984, the Indiana Supreme Court vacated the stay of

execution.

7. On December 10, 1984, Judge Boles ordered Smith to be

executed on January 10, 1985. Smith obtained a stay of the order

pending his pursuit of post-conviction relief.

8. On August 2, 1985, Smith filed an Amended Petition for

Post-Conviction Relief in state trial court. Evidentiary hearings were held

on December 5-6, 1985. Judge Patricia Gifford denied the petition on

September 29, 1986.

9. On October 8, 1986, Judge Boles issued an order setting an

execution date of November 10, 1986.

10. On October 24, 1986, the Indiana Supreme Court granted

Smith's Petition for a Stay of Execution pending a decision on appeal of

the denial of post-conviction relief to the Indiana Supreme Court or a

decision on a Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Supreme

Court.

11. On December 16, 1987, the Indiana Supreme Court

unanimously affirmed the denial of the post-conviction relief petition.

Smith v. State, 516 N.E.2d 1055 (Ind. 1987), cert. denied, 488 U.S. 934

(1988).

12. On October 31, 1988, the United States Supreme Court

denied Smith's Petition for Writ of Certiorari on the denial of

post-conviction relief. Smith v. State, 488 U.S. 934 (1988).

13. On November 4, 1988, Judge Boles set an execution date of

December 11, 1988.

14. On November 25, 1988, Smith filed a Petition for Writ of

Habeas Corpus in the United States District Court for the Northern District

of Indiana.

15. On November 29, 1988, the United States District Court

granted a stay of execution pending disposition of the habeas petition.

16. On March 29, 1989, Chief Judge Allen Sharp of the U.S.

District Court heard arguments on the habeas petition.

17. On May 19, 1989, Chief Judge Sharp stayed the habeas

proceedings at Smith's request pending the filing and disposition of a

second post-conviction relief petition.

18. On October 3, 1990, Smith filed his second Petition for

Post-Conviction Relief. The state trial court dismissed the petition on

November 14, 1991.

19. On May 12, 1993, the Indiana Supreme Court affirmed the

dismissal of the second post-conviction relief petition and remanded the

matter to the trial court to set a date for Smith's execution. Smith v.

State,

613 N.E.2d 412 (Ind. 1993). On October 4, 1993, the Indiana Supreme

Court denied rehearing.

20. On April 25, 1994, the United States Supreme Court denied

Smith's Petition for Writ of Certiorari. Smith v. State, 114 S. Ct. 1634

(1994).

21. On October 14, 1994, the United States District Court heard

oral arguments on the habeas petition. On October 31, 1994, Chief

Judge Sharp denied Smith's habeas petition and request for an

evidentiary hearing. Smith v. Farley, 873 F. Supp. 1199 (N.D. Ind. 1994).

22. On July 5, 1995, the United States Court of Appeals for the

Seventh Circuit affirmed the district court's denial of habeas corpus relief

after arguments in May of 1995. Smith v. Farley, 59 F.3d 659 (7th Cir.

1995).

23. On July 18, 1995, Smith filed a petition with the United States

Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit for rehearing with a suggestion

for rehearing en banc on the habeas petition. On August 1, 1995, the

Seventh Circuit denied rehearing.

24. On February 20, 1996, the United States Supreme Court

denied Smith's Petition for Writ of Certiorari from the denial of the habeas

petition. Smith v. Parke, 116 S. Ct. 935 (1996).

25. On February 26, 1996, Smith filed with the United States

Supreme Court a Notice of Application for Stay of the Order Denying

Certiorari. On February 27, 1996, the Supreme Court denied Smith's

motion to stay the certiorari denial.

26. On March 25, 1996, Smith filed a Verified Tender for

Successive Petition for Post-Conviction Relief, asking the Indiana

Supreme Court to authorize the filing of a third post-conviction relief

petition and requesting oral argument. On April 24, 1996, the Indiana

Supreme Court issued an order denying Smith's request to authorize the

filing of a successive petition for post-conviction relief and denying oral

argument. The court ordered that Smith be executed on June 14, 1996.

Smith v. State, No. 49S00-9603-SD-246. (Ind. Apr. 24, 1996).

27. On May 3, 1996, Smith filed a Motion for Modification and

Correction of Order Denying Leave to File a Successive Post-Conviction

Petition with the Indiana Supreme Court. On May 8, 1996, the court

denied the motion. Smith v. State, No. 49S00-9603-SD-246. (Ind. May 8,

1996).

28. On May 13, 1996, Smith filed a Petition for Clemency before

the Indiana Parole Board.

29. On May 14, 1996, Smith filed before the United States Court

of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit a Motion to Recall the Mandate and For

Leave to File a Second Petition for Rehearing with Suggestion for

Rehearing En Banc. On May 20, 1996, the Seventh Circuit denied Smith's

motion.

30. On May 28, 1996, the Parole Board conducted a hearing at

the State Prison regarding Smith's clemency petition.

31. On June 3, 1996, the Parole Board conducted a public

hearing at the Indiana Government Center regarding Smith's clemency

petition.

32. On June 4, 1996, the Parole Board unanimously

recommended that Smith's petition for clemency or reprieve be denied.

33. On June 6, 1996, Smith filed a Motion for an Order

Authorizing the District Court to Consider a Second Habeas Corpus

Application with the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh

Circuit. On June 10, 1996, the Seventh Circuit denied the motion. 34.

On

June 10, 1996, Smith filed with the United States Supreme Court a Petition

for Writ of Certiorari from Denial of Relief from the Seventh Circuit, a

Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus and a Petition for Stay of Execution.

On June 13, 1996, the Court granted a stay pending review of Smith's

Petition for Writ of Certiorari. Smith v. Parke, No. 95-9261, 64 U.S.L.W.

3834 (U.S. June 13, 1996).

35. On July 1, 1996, the Supreme Court denied Smith's Petition for

Writ of Certiorari from Denial of Relief from the Seventh Circuit, dismissed

the Petition for a Writ of Habeas Corpus and pursuant to its earlier order,

automatically dissolved the stay of execution. Smith v. State, No.

95-9264, 64 U.S.L.W. 3868 (U.S. July 1, 1996).

36. On July 3, 1996, the Indiana Supreme Court ordered that

Smith be executed on July 18, 1996. Smith v. State, No. 49S00-9603-246

(Ind. July 3, 1996).

37. On July 5, 1996, Smith filed a subsequent petition for

clemency or reprieve with the Indiana Parole Board.

38. On July 9, 1996, the Parole Board conducted a hearing at the

State Prison regarding Smith's clemency petition.

39. On July 9, 1996, Smith filed a motion with the Indiana

Supreme Court for stay of execution pending the resolution of his Petition

for a Writ of Habeas Corpus from the United States Supreme Court. On

July 10, 1996, the court denied the motion. Smith v. State, No.

49S00-9603-SD-246 (Ind. July 10, 1996).

40. On July 10, 1996, Smith filed a Petition for a Writ of Habeas

Corpus in the United States Supreme Court.

41. On July 10, 1996, the Parole Board conducted a public

hearing regarding Smith's clemency petition. After hearing testimony, the

Board unanimously recommended that Smith's petition for clemency or

reprieve be denied.

ABOLISH Archives (Indianapolis Star) INDIANAPOLIS (May 14, 1996) -- Condemned murderer and Death Row

inmate Tommie J. Smith asked the Indiana Parole Board on Monday to

consider giving him clemency, but he made it clear he expects no

compassion. Unlike two other recent clemency hearings for Death

Row inmates, Smith's petition does not ask the five-member panel

to consider his background and upbringing as reasons to set aside

his June 14 execution.

The clemency petition, filed an hour before the deadline,

instead argues that there is a purely legal reason that Smith, 42,

should not be executed -- he was acting in self-defense when he

fired a rifle at Indianapolis Police Detective Jack Ohrberg in

1980. Ohrberg and other police officers had come to Smith's

apartment at 5:30 a.m. to arrest him and two other men suspected

of robbing two banks and slaying Brink's armored car driver William

E. Sieg Sr.

Smith's attorney, Andrew Maternowski of Indianapolis, says he

can prove to the Parole Board that it would have been

physically impossible for Smith to have fired the two other shots

that struck Ohrberg as he was attempting to kick in the door.

Maternowski believes the other shots likely were fired by police

officers when a gunfight erupted. In the clemency petition, Smith

insists he did not know Ohrberg was a police officer.

"In defense of my life from what I thought was an intruder, I

grabbed a nearby rifle and fired one shot," Smith said. He claims

he could not have fired another shot because Ohrberg fired at him,

disabling his AR-15 assault rifle and wounding him in the leg.

Smith concedes that if he had walked out on his porch and fired two

more shots at Ohrberg -- as the prosecution claims -- he would

deserve the death penalty.

Maternowski said Smith has never been allowed to raise that issue

in his many appeals since his original conviction. The clemency

hearing is Smith's last hope to avoid becoming the first Hoosier

executed by lethal injection. Maternowski said that after Smith

saw what happened to Gary Burris in his clemency hearing last

November, he decided not to bother with making his upbringing an

issue.

Much of the hearing for Burris, who was sentenced to die for

killing an Indianapolis cab driver, focused on how he was abandoned

as a toddler in a trash can, raised in a house of prostitution and

abused repeatedly. Despite that, the Parole Board and Gov. Evan

Bayh refused to commute his sentence, which was later stayed by a

federal appeals court in Chicago. "It is my client's position that

after the board refused to consider the horrendous background of

Gary Burris, there is no compassion in the board or the governor,"

Maternowski said.

Bayh refused to commute the sentence of Smith's co-defendant, Gregory Resnover, who was electrocuted in December 1994.

The Parole Board scheduled a public hearing on Smith's clemency

request to begin at 1 p.m. June 3 in Indiana Government Center

South. Family, friends and his attorneys will be allowed to speak

on his behalf.

The board will vote publicly on its recommendation June 4. It then

goes to Bayh, who can accept or reject it any time before the

scheduled execution.

Post-Furman Botched Executions by Michael L. Radelet

Botched Executions - July 18, 1996 - Indiana - Tommie Smith

Smith was not pronounced dead until an hour and 20 minutes after the execution team began to administer the lethal combination of intravenous drugs. Prison officials said the team could not find a vein in Smith's arm and had to insert an angio-catheter into his heart, a procedure that took 35 minutes. According to authorities, Smith remained conscious during that procedure.

.

Indiana Coalition Against the Death Penalty Bob Hammerle decided he would look.

Despite advice that he simply glance away, Hammerle would keep his eyes focused on Gregory Resnover as 2,300 volts of electricity surged through the convicted man's body -- jolting it up in the wooden chair against straining leather straps, sending a flash of flame and a wisp of smoke up from his head, and permeating the room with the sickly sweet scent of burnt flesh.

As Resnover's heart stopped, Hammerle's heart pounded.

As Resnover's life ended, Hammerle's life was wrenched.

Resnover's eyes were hidden by a black hood, and Hammerle couldn't turn his eyes away.

Now, 6 years later, the criminal defense attorney's opposition to the death penalty remains strong -- intellectually, philosophically, emotionally and morally. But he can't do the legal work anymore.

He cannot represent a client who faces the death penalty.

Not since Resnover.

"I can't deal with it when somebody's life's on the line," he said, furiously wiping away tears after recounting the last minutes of Gregory Resnover's life. "Because you can't have this happen.

"I mean, you've got to stay detached, and I can't anymore."

Hammerle had been involved with only a few death penalty cases before Resnover's and was on the Resnover case for only 7 months, when lawyers had exhausted all court appeals.

He had long been a passionate voice against capital punishment, however, and joined Resnover's legal team for the final rounds of the battle for Resnover's life. Hammerle was brought on board to argue for clemency before the parole board and to be the point-person for the media. He became as close to Resnover as the rest of the team, and continues to argue even now that Resnover was executed based on a court record filled with errors.

His passion about the Resnover case is something he believes even Jack Ohrberg would have understood, he said, recalling a difficult case in which Ohrberg, by testifying truthfully, hurt the prosecution's case.

Ohrberg was a man of integrity, and the law mattered to him, Hammerle said. That's why he could reconcile his grief for the slain officer while he worked on behalf of Resnover.

"It was what Jack Ohrberg would have expected me to do," Hammerle said.

When all of Resnover's appeals were gone and an execution date loomed, it was Hammerle who was chosen to watch -- to ensure that Resnover knew an advocate was with him, and to be a witness should something go wrong. It was a role no one on the legal team wanted, but all agreed someone had to see through.

It's not unusual for attorneys who watch their clients be executed to never take a death penalty case again, said George Kendall, staff attorney with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in New York.

"It asks too much of people," said Kendall, who has witnessed 4 executions. "It's the worst experience I've ever had."

It was Kendall who advised Hammerle, in a long distance call from New York to the car that was taking Hammerle to Michigan City's Indiana State Prison, to look away for the 1st jolt.

Kendall had been there, and he wanted to spare Hammerle the horror.

Instead, Hammerle absorbed the execution completely. It would give him nightmares, leave him weeping whenever he recounted it and send him to therapy.

And the day after Resnover was executed, the legal team made a decision that would haunt Hammerle in another way -- they drove Resnover's body back to Indianapolis and paraded it in a caravan around the governor's residence. Then-Gov. Evan Bayh was serving as host of a Christmas party and many of the guests were friends of Hammerle's.

The caravan was a protest, one that seemed logical to the frustrated and heart-broken attorney at that time, but it left him ostracized from the Democratic "in" group, which didn't appreciate the timing or the tone of the demonstration. For Hammerle, a social man who thrives on human interaction and conversation, the long-term fallout was devastating.

Even today, while he won't actually say he regrets the decision to take Gregory Resnover to crash the governor's Christmas party -- he remains loyal to the cause and devoted to his colleagues -- it's the one aspect of his advocacy for Resnover that gives him pause.

"I'm tormented by the possibility that somehow, I tarnished the whole thing," he said. "I was fearful of that."

Still, friendships were lost. Over the long term, the stress also contributed to strain on his marriage to Monica Foster, his law partner at the time and a leader of Resnover's legal team. Their divorce is now pending.

Foster and Rhonda Long-Sharpe, who also was on the Resnover team and part of Hammerle's Indiana Avenue law practice, have left to open their own firm. They will concentrate on the kind of legal work that Hammerle has left behind -- capital punishment.

In the days, months and years since the execution, Hammerle has endured symptoms of post-traumatic stress syndrome similar to the battle-fatigue of war veterans and others who have been traumatized.

"He would wake up in the middle of the night screaming, and that was something he never did before,'' said Foster, who remains close to Hammerle.

Foster was at a nearby motel during the execution, but she wasn't left unscathed by it.

"I didn't get out of bed for 2 months," she said. "When I finally did get up, I seriously questioned whether I was going to go back to work."

Eventually, she did -- and she credits Resnover with helping her do so.

Foster also still can't get through a discussion about Resnover without choking up, which she did as she recounted her last visit with him. He told and Long-Sharpe that their efforts had given him dignity.

"He said, 'Keep fighting for these guys.' And we said, 'That is the one thing that we cannot promise you.' He said, 'Give it a couple of days or a couple of weeks. If you feel the strength to represent people back here, then you will know that I will be helping hold you up.'"

At first, Hammerle tried to do more death penalty work, too. He took one case within a year or two of Resnover's execution, but had to be excused because he had once represented a witness for the state. But during the time he was on the case, Hammerle said, he realized he was hoping to be removed from the case.

For the realization that he can no longer represent clients facing the death penalty, he offers this baseball metaphor:

A batter who has been beaned by a fastball might never be a reliable hitter again, because he flinches.

A defendant who faces the death penalty, Hammerle says, can't afford an attorney who flinches.

Smith v. State, 465 N.E.2d 1105 (Ind. July 24, 1984) (Direct Appeal).

Defendant was convicted in the Superior Court, Marion County, Jeffrey V. Boles, Special Judge, of murder and conspiracy to commit murder, and he appealed. The Supreme Court, Pivarnik, J., held that: (1) the death penalty statute is constitutional; (2) there was no violation of the defendant's rights in excusing jurors who unequivocally stated that they could not, under any circumstances, vote for the death penalty; (3) the defendant was not entitled to reversal on the ground that the jury panel included only persons who were not black; (4) any error in denying a motion for a change of venue was invited; (5) the defendant did not receive ineffective representation of counsel; (6) it was proper for the defendant to be tried jointly with his codefendant and to have presented to the same jury in the same trial both charges of murder and conspiracy to commit murder; (7) the trial court's evidentiary rulings were proper; (8) the trial court could properly conclude that the defendant did not have standing to challenge a search of the apartment in which the shooting occurred; (9) the defendant could be tried, convicted and sentenced for both murder and conspiracy to commit murder; (10) the evidence was sufficient to sustain the convictions; and (11) the death penalty was not arbitrarily or capriciously imposed.

Affirmed.

PIVARNIK, Justice.

Many of the issues presented to us here were the same issues in the appeal presented by Resnover and have already been decided in that case. There are also several issues raised here that pertain only to Defendant Smith. The issues that are presented concern:

1. constitutionality of Indiana's death penalty statute, Ind. Code § 35-50- 2-9;

2. questions concerning the jury selection;

3. denial of change of venue because of pre-trial publicity;

4. denial of investigators to aid in the defendant's defense;

5. ineffective representation and incompetency of counsel;

6. refusal by the trial court to sever the charges of the defendant and sever the defendant's trial from that of his co-defendant;

7. evidentiary rulings by the trial court;

8. evidence obtained by improper search and seizure;

9. refusal by the trial court to give instructions on lesser-included offenses;

10. permitting the jury to have instructions and exhibits in the jury room during deliberations;

11. the question of double jeopardy in the defendant's conviction of murder and conspiracy to commit murder;

12. prejudicial statements by the trial court; and,

13. sufficiency of the evidence.

The evidence most favorable to the State was presented in Resnover, supra, at 926-27, and we adopt that recitation and make it part of this opinion as follows:

The evidence adduced during trial showed that at approximately 3:00 a.m. on December 11, 1980, Indianapolis Police Sergeant Jack Ohrberg met Sergeant Lewis J. Christ to serve papers on certain individuals believed to be at 3544 North Oxford Street in Indianapolis. Sergeant Ohrberg and Christ subsequently were joined by other officers before arriving at the duplex residence at 3544 North Oxford at approximately 5:30 a.m. With Officers Schneider and Harvey standing watch in the rear, Ohrberg, Christ and Officers Ferguson and Foreman proceeded to the porch and front door. Foreman and Ferguson were in uniform. Ohrberg knocked loudly several times and identified himself as a police officer. He then went to 3546 North Oxford, the adjacent other half of the double residence, and checked with Sandra Richardson to ascertain whether any persons were known to be inside the 3544 address. Richardson told Ohrberg that she had heard noise come from 3544.

Ohrberg returned to 3544 and again pounded on the front door and announced himself as a police officer. Ohrberg then assumed a crouched position and started to use his right shoulder to batter the door which, after a few hits, began to open. Ohrberg continued to hit the door placing his body partially inside the door. Foreman was shining a flashlight over Ohrberg's head since it was dark inside the residence and Foreman wondered why the front door would not fully open. Looking inside the house, Foreman saw some furniture blocking the door. Sergeant Christ also saw the furniture. As Foreman looked inside, he suddenly saw a burst of muzzle flashes and heard two, possibly three, shots in quick succession. The simultaneous muzzle blasts came from two separate locations approximately eight to ten feet apart. Christ also heard shots emanate from inside the residence. Ohrberg said: "Oh, no, I've been shot" or "I've been hit" and then stepped back two steps, sank to his knees and collapsed on the porch.

Taking cover, Christ saw a person with an "Afro" type hairstyle emerge from the dark doorway onto the porch and fire at least two additional shots into Sergeant Ohrberg. Shots also were being rapidly fired from within the residence. When Christ returned the gunfire, the man on the porch quickly retreated inside the building. Ferguson also saw the person stand over Ohrberg and fire his rifle into Ohrberg. Ferguson specifically testified that he could see the muzzle flash as the rifle was fired. Ferguson fired at the gunman and then ran around the corner of the house where gunfire continued to be directed at him. After more shooting, a man identifying himself as "Gregory" called from inside the house and said "Let's talk." "Gregory" stated that there was an injured man inside and offered to send out the two women occupants. Christ refused to accept the women and ordered "Gregory" outside. "Gregory" then said that he would come out whereupon he stepped to the door, threw a weapon out into the front yard and walked onto the front porch with his hands raised. Christ identified this man as Appellant Gregory Resnover and identified an AR-15 rifle as similar to the weapon Appellant threw into the front yard. Ferguson also identified the man as Gregory Resnover. Earl Resnover subsequently followed Appellant out onto the front porch where he laid down an AR-15 rifle and a Smith and Wesson revolver. Two women lastly walked out of the house leaving wounded Tommy Smith alone in the building. Foreman testified that the four came out of the house approximately ten to fifteen minutes after the initial burst of gunfire.

Forensic pathologist Dr. James A. Benz performed an autopsy on the body of Jack Ohrberg. Benz testified that Ohrberg died as a result of multiple gunshot wounds. He specifically testified that one bullet perforated Ohrberg's abdominal wall and external iliac artery and completely severed his iliac vein. Another shot lodged in the soft tissues of Ohrberg's back after fracturing parts of two vertebrae. A third shot entered his left side, fractured his tenth rib and bruised his lung. There were 600 mililiters of blood in Ohrberg's abdominal cavity.

The weapons thrown into the front yard or left on the front porch were collected by Russell Bartholomew, a crime lab technician. Bartholomew testified that the weapon thrown down by Appellant was an AR-15 automatic rifle with live rounds. The weapons on the porch were another loaded AR-15 and a loaded .38 caliber Smith and Wesson revolver. Evidence technician Cosmos Raimondi recovered weapons, ammunition clips, bullets and shell fragments from inside the house after it was secured by police. Raimondi testified that he found:

--one AR-15 rifle without clip but with one live round chambered; the rifle clip was located nearby damaged but containing twenty-five live rounds;

--one .30 caliber Universal carbine with one round chambered and a clip containing twenty-five rounds;

--one rifle clip concealed in a bathroom light fixture;

--one Mauser 7.65 automatic pistol recovered from underneath the front room sofa with one round chambered and one five round clip;

--fifteen spent shell casings recovered from the front room and kitchen;

--twelve live Smith and Wesson rounds for a .38 caliber Special pistol;

--one .223 ammunition clip with twenty-five live bullets discovered hidden underneath the front sofa;

--another .223 ammunition clip with twenty-six live bullets;

--one ammunition pouch with seven live automatic bullets found underneath a cushion on the front sofa;

--fifteen Smith and Wesson Specials and one WW .38 Special found lying loose on a coffee table;

--one Memorex casette box with fifteen live .38 caliber bullets;

--one AR-15 clip with thirty live .223 caliber bullets discovered in the rear bedroom; and

--one black shaving case containing one knife, one empty Colt AR-15 clip, one ammunition clip possibly for a M-1 carbine and two hearing protectors.

The AR-15 recovered from the front porch bore Appellant's fingerprints on the ammunition clip. Although this gun had fired eight of the recovered shell casings, it did not fire the bullet recovered from Ohrberg's body. The AR-15 found inside the house with its broken clip located nearby fired the bullet retrieved from Ohrberg's body. The broken clip appeared to have been dented by a bullet.

Crime lab technician Robert McCurdy testified that he performed atomic absorption tests on swabbings taken from the arms of Appellant and Tommy Smith. Appellant's right arm had significantly higher amounts of barium and antimony, components of modern ammunition primer, indicating his handling or firing of a gun. The tests conducted on the swabbings taken from Appellant's left arm were inconclusive. McCurdy also recovered from Earl Resnover a billfold containing Sergeant Ohrberg's business card." Atomic absorption tests on swabbings taken from the arms of Tommie Smith also indicated his handling or firing of a gun.

* * *

Defendant also had witnesses he requested brought to his defense who apparently would testify they witnessed Sgt. Ohrberg attempt to kick down doors before he announced that he was present and requested to be admitted. It was counsel's consideration that this would be a choice of strategy that would work against the interest of Defendant rather than to his benefit. In the first place, counsel had serious question whether such testimony would be admissible in view of the strong direct evidence that Sgt. Ohrberg and other police here did announce their presence and that their presence was acknowledged by the defendants inside the apartment before entry was attempted. Furthermore, these witnesses coming on the stand would reveal themselves as friends and associates of Defendant and would also reveal the fact that they had many times themselves been involved in criminal activities. Counsel therefore determined the wisest choice was to refrain from attempting to present this defense. We again can see no showing of incompetence on the part of counsel in making such a decision. Nelson v. State, (1980) 272 Ind. 692, 401 N.E.2d 666.

Defendant attempted several times to file motions pro se, raising questions that he insisted be raised when counsel refused to do so. The court finally advised Defendant he was not permitted to file motions on his own but should file them through his attorney. Many of these motions were on issues we have already discussed here and all of them were based on the fact that he adamantly insisted on certain matters being raised even though counsel advised him it would be to his detriment to do so. Because of some of these conflicts, Defendant at various times moved to dismiss his attorney and obtain a better one. The court told him he saw no reason to remove the attorney and that if Defendant wished to hire other counsel on his own he was free to do so. Defendant never asked to proceed pro se and never offered to bring in another attorney. He stated he could not afford to hire another attorney but felt he wanted one who would do his bidding. At one point, counsel offered to withdraw if the court would permit him to do so and expressed to the court that he was making such an offer to give Defendant every opportunity to receive the best possible defense. Counsel advised the court that there was no serious conflict between himself and Defendant personally but that there were choices of strategy in which they differed. The trial court stated he saw no reason to remove counsel and made a finding that counsel was doing a sound and professional job in defending Defendant.

* * *

Finally, Defendant claims there was insufficiency of evidence to be found guilty of murder and conspiracy to commit murder beyond a reasonable doubt. On such an issue we neither weigh the evidence nor judge the credibility of witnesses. We determine only whether there is sufficient evidence of probative value from which the fact finder could make its findings beyond a reasonable doubt. If there is evidence of probative value to support the conclusion of the jury in the trial court, the conviction will not be overturned. Napier v. State, (1983) Ind., 445 N.E.2d 1361, The only interpretation that can be given Defendant's argument on this issue is that he asks us to reweigh the evidence and the credibility of the witnesses. This, of course, we will not do.

There was more than sufficient evidence to justify the jury in finding the defendant guilty of both charges beyond a reasonable doubt. We have already set out the facts showing that the defendants knew there were police officers outside demanding entry and, in fact, some strong inferences that they knew it was Sgt. Ohrberg. When the police tried to enter, they found the door blocked with a piece of heavy furniture and when Ohrbert attempted to force the door and enter he was shot from two different points in the room. There was further evidence that Earl Resnover and two women who were in the residence were locked in another room or at least were confined there because the door was stuck. The evidence indicated that Smith and Gregory Resnover were the two firing from the room at Ohrberg. One of the bullets fired by Ohrberg struck Smith and he was found in that position after the firing ceased. At least one of the bullets found in Sgt. Ohrberg's body came from an AR-15 rifle that was found near the position of Tommie Smith in the room. An autopsy revealed that Ohrberg had been hit at least three times and that the cause of his death was multiple gunshot wounds.

There is, therefore, no merit to Smith's contention that there is a lack of evidence that he was the "triggerman" who killed Ohrberg. Gregory Resnover, in his appeal, Resnover, 460 N.E.2d at 934 (Issue VIII), raised the same question Smith raises, that there is no proof that he was the "triggerman", and cites us to United States Supreme Court case of Enmund v. Florida, (1982) 458 U.S. 782, 102 S.Ct. 3368, 73 L.Ed.2d 1140. As we pointed out in Resnover, supra, defendant Enmund was a getaway car driver whose confederates robbed and killed an elderly farm couple. Defendant Enmund apparently never left the car and therefore was not present when the victims were actually confronted or when the plan to rob the elderly couple led to their being murdered. The Supreme Court held that since the record did not show that the defendant intended to participate in or facilitate a murder, his culpability for the murder perpetrated by his confederates was different than that of his confederates.

In this case the jury could have found that defendant Smith was, in fact, the trigger man or one of the trigger men who directly caused Ohrberg's death as both Smith and Gregory Resnover were firing at Ohrberg at the time he fell. After Ohrberg fell, a person who appeared to be Gregory Resnover stepped out on the porch and fired two more shots into Ohrberg's body. Later, when Gregory Resnover surrendered, he carried out an AR-15 rifle but shots from that rifle were not the ones that killed Sgt. Ohrberg. The gun that killed Sgt. Ohrberg was lying in the room near Tommie Smith and also near the position occupied by Gregory Resnover during the shooting. Tommie Smith's position then is not different than Resnover's in that it cannot be said that either of them neither took a life, attempted to take a life, nor intended to take a life. Unlike Enmund, supra, Defendant's criminal culpability was equal to that of Resnover's as one or both of them caused Ohrberg's death and Smith clearly fired on Detective Ohrberg with every intention of taking his life. Under these circumstances there need be no actual proof as to which of these participants actually caused the death of Sgt. Ohrberg. Smith is equally guilty with Resnover and the jury was therefore justified in finding that he was either the trigger man or one of the trigger men who directly caused Ohrberg's death. Defendant Smith therefore presents no showing of reversible error on this issue.

Having considered all of the issues raised by Defendant and finding no error, we now examine whether the death sentence imposed by the court is appropriate in Defendant's case. The trial judge made detailed and written findings pursuant to Ind.Code § 35-50-2-9 (Burns Supp.1984) to facilitate our review. The trial judge found that the State had proven beyond a reasonable doubt the aggravating circumstance that the victim of this murder was a law enforcement officer acting in the course of his duty. He then indicated it was his duty to determine any mitigating circumstance in the case. He then specifically considered each mitigating circumstance set out in the above statute. He indicated he was doing this from reviewing all the evidence in the case, the arguments of counsel, the law as presented to him by counsel, and the pre-sentence investigation as submitted to the court by the probation department. He found that Defendant had a significant history of prior criminal conduct and detailed these involvements in his findings, concluding that mitigation was not proven in that regard. He found there was no evidence of mitigating circumstance with regard to the question of whether defendant Smith might have been under the influence of extreme mental or emotional disturbance when he committed this murder by finding that there was no evidence in the record whatsoever that Defendant was, in fact, under any mental or emotional disturbance at the time of the crime.

He further found beyond a reasonable doubt that there was no indication whatsoever that the victim in this case participated in or consented to Smith's conduct against him. He further considered the mitigating circumstance of whether or not the murder was committed by another person and the participation of this defendant was relatively minor. The judge then found that by the words of the defendant himself, he indicated that his participation was direct. He further found that he searched the record to determine whether or not defendant Smith had acted under the substantial domination of another person and found beyond a reasonable doubt that there was no such domination by anyone else but that this was a conscious act by defendant Smith that he chose. He then directly found that there was no evidence to indicate that the defendant did not appreciate the criminality of his conduct or conform his conduct to the requirements of law because of being substantially impaired by mental disease or defect or intoxication. He found there were no facts whatsoever presented to indicate this. The trial judge therefore found that there were no mitigating circumstances.

The trial judge then found that the felony committed by defendant Smith resulted in the death of Sgt. Ohrberg and involved the threat of death and great bodily harm to other people. He found that Defendant knowingly directed gunfire toward Sgt. Ohrberg while he was in the performance of his duties as a police officer. He found this conduct caused and threatened to cause serious bodily harm to other people. He then found from considering all the circumstances in the case that Defendant contemplated this act by the knowing use and collection of especially deadly weapons. He found there was no provocation whatsoever for Defendant's acts and no grounds existed that he could find in the cause to excuse the conduct intentionally engaged in by Defendant on the night of the murder. The judge then found that Defendant played a major role in the commission of this offense and that he made no good faith effort whatsoever to compensate or explain his actions to the victim in this case. He further found that the age of the defendant was not a factor in the case. The trial judge then concluded that the proper sentence for Smith was death by electrocution.

The record supports all of the findings by the trial judge and does show that Defendant took a direct and substantial part in all of the incidents involving the shooting at police officers which resulted in Sgt. Jack Ohrberg's death. The record clearly shows that Smith knowingly and intentionally participated in this criminal activity knowing that Sgt. Ohrberg was acting in an official capacity as a police officer and causing the death of Sgt. Ohrberg while he was serving in an official capacity as a police officer. We therefore find and now hold that the death penalty as provided for by our statutes was not arbitrarily or capriciously imposed upon defendant Smith and is reasonable and appropriate in his case.

The trial court is affirmed in all things, including its imposition of the death penalty upon defendant Smith. This cause is accordingly remanded to the trial court for the sole purpose of setting the date when Defendant's death sentence is to be carried out.

GIVAN, C.J., and DeBRULER, HUNTER and PRENTICE, JJ., concur.

RE: TOMMIE J. SMITH'S PETITION FOR CLEMENCY OR REPRIEVE

Defendant-Appellant Tommie Smith was convicted of Conspiracy to Commit Murder, Ind. Code §§ 35-41-5-2 and 35-42-1-1(1) (Burns Repl.1979), and Murder, Ind. Code § 35-42-1-1 (Burns Repl.1979), at the conclusion of a jury trial in Marion Superior Court on June 29, 1981. The trial court sentenced Defendant Smith to fifty (50) years imprisonment for conspiracy and to death for murder. Smith now appeals his convictions and sentences. This is a companion case to Resnover v. State, (1984) Ind., 460 N.E.2d 922, reh. denied. Defendants Smith and Resnover were tried jointly and given the same penalty.