11th murderer executed in U.S. in 2005

955th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Oklahoma in 2005

76th murderer executed in Oklahoma since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

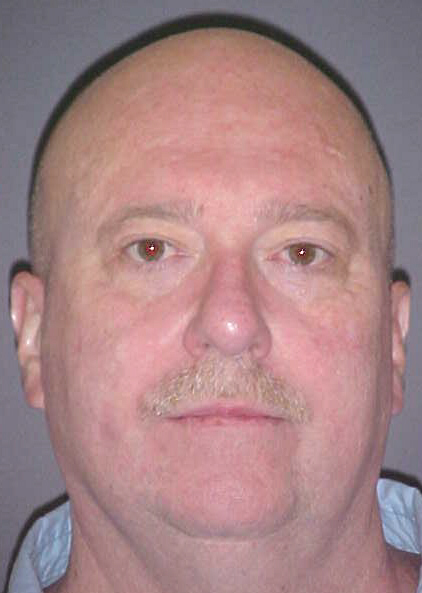

Jimmie Ray Slaughter W / M / 44 - 57 |

Melody Sue Wuertz W / F / 29 Jessica Rae Wuertz W / F / 1 |

Daughter |

Summary:

Slaughter was condemned to death for killing his former girlfriend, 29-year-old Melody Wuertz, and their daughter, Jessica Rae Wuertz. The infant was five days from her first birthday when she was shot twice in the head by a small caliber gun. Melody Wuertz was stabbed in the chest, shot two times and her body was mutilated. One of the marks carved into her abdomen had the appearance of the letter R. Prosecutors contend Slaughter shot and paralyzed Melody Wuertz before killing Jessica, then finished killing his former girlfriend. Slaughter maintained his innocence of the murders to the bitter end.

Citations:

Slaughter v. State, 2005 WL 562759 (Okl.Cr.App 2005) (3rd PCR).

Slaughter v. State, 105 P.2d 832 (Okl.Cr.App. 2005) (2nd PCR).

Slaughter v. State, 969 P.2d 990 (Okl.Cr. 1998) (PCR).

Slaughter v. State, 950 P.2d 839 (Okl.Cr. 1997) (Direct Appeal).

Slaughter v. Mullin, 68 Fed.Appx. 141, Slip Copy, 2003 WL 21300287 (10th Cir. 2003) (Habeas).

Final Meal:

Fried chicken, mashed potatoes, cole slaw, biscuits with honey butter, an apple pie, one pint of cherry ice cream and a large cherry limeade.

Final Words:

"I've been accused of murder and it's not true. It was a lie from the beginning. God knows it's true, my children who were with me know it's true and you people will know it's true someday. May God have mercy on your souls."

Internet Sources:

Oklahoma Department of Corrections

Inmate: JIMMIE R SLAUGHTER

ODOC# 229799

OSBI#:

FBI#: 186685PA2

Birthdate: 06/06/1947

Race: White

Sex: Male

Height: 6 ft. 01 in.

Weight: 240 pounds

Hair: Brown

Eyes: Brown

County of Conviction: Oklahoma

Location: Oklahoma State Penitentiary, Mcalester

Oklahoma Attorney General News Release

01/19/2005 News Release - W.A. Drew Edmondson, Attorney General

Slaughter Execution Date Set

The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals today set March 15 as the execution date for Oklahoma County death row inmate Jimmy Ray Slaughter.

Slaughter was convicted of the July 2, 1991, murders of his ex-girlfriend Melody Sue Wuertz, 29, and their one-year-old daughter Jessica Rae Wuertz. The murders were committed in Wuertz’s Edmond home. Melody Wuertz was shot in the head and neck and her body was stabbed and slashed multiple times. Jessica Wuertz was shot in the head.

By a unanimous vote of members present, the Oklahoma Pardon & Parole Board denied clemency for Jimmie Ray Slaughter, a death row inmate scheduled to be executed March 15. Board member and former Attorney General Susan Loving recused herself from the meeting.

Slaughter, 57, was condemned to death for the 1991 deaths of his former girlfriend, 29-year-old Melody Wuertz, and their daughter, Jessica Rae Wuertz. The infant was five days from her first birthday when she was shot twice in the head by a small caliber gun. Melody Wuertz was stabbed in the chest, shot two times and her body was mutilated. One of the marks carved into her abdomen had the appearance of the letter R. Prosecutors contend Slaughter shot and paralyzed Melody Wuertz before killing Jessica, then finished killing his former girlfriend.

"Slaughter knew what he was doing when he shot and paralyzed her," said Melody Wuertz' father, Lyle Wuertz. "I don't imagine she could speak, but in her mind she was screaming 'no, please no' when he killed her baby. It's time he was removed from this earth. He's not a man. He's an evil it and he must be destroyed. What this man has dumped into our lives is nothing short of a toxic bomb of evil."

Slaughter claims he is innocent of the crime, that he was shopping with his family in Topeka, Kan., when the mother and daughter were killed. But Assistant Attorney General Seth Branham told board members "nothing could be further from the truth. Facts inculpate Slaughter. These facts prove he's guilty." Prosecutors contend that at the time of the murders, Slaughter commonly went by his middle name, Ray, and that Jessica had been named after him. The R carved into Melody Wuertz's abdomen looked much like an R on a knife sheath of Slaughter's, Branham said. Prosecutors say Slaughter had left the Fort Riley military post early in the morning of July 2, 1991, driven to Edmond and killed the Wuertz family before returning to Kansas in time to meet his wife and two daughters at a Topeka store. In fact, Branham said, although some of the store clerks at Topeka stores remembered seeing Nicki Slaughter and the two girls, they did not remember Jimmie Slaughter.

Investigative reports indicate that although Slaughter had given Melody Wuertz money at various times, he did not want to pay her child support. In addition, one report indicates Melody Wuertz had told a friend she was afraid of Slaughter and that he still had a key to her house. Branham said Slaughter was furious after he was served child support papers and told several people that he would kill Melody Wuertz and the baby. As early as April 1991, Branham said, Slaughter talked about trying to place items at a crime scene to throw off investigators. A woman who worked with Slaughter at the Veterans Administration Health Center in Oklahoma City - another former girlfriend - told investigators she had mailed Slaughter a package containing soiled underwear and hairs from a black hospital patient. The underwear and hairs were found in Wuertz's home when her body was discovered. Defense attorneys conceded that Slaughter had received the items, Branham said.

A former investigator on the case, Dennis Dill, contends Melody and Jessica Wuertz were murdered much earlier than prosecutors said. That contention is based largely on the fact that noodles, peas and carrots were found in Jessica's stomach and her baby-sitter told investigators she had fed Jessica the meal the evening of July 1, 1991. No containers of noodles, peas and carrots were found in the Wuertz home or trash, according to investigative reports. But Branham said "peas, noodles and carrots don't amount to a hill of beans. The evidence makes clear the time of death was appropriate. Noodles, peas and carrots? I'll tell you when the baby ate that. It was about 11:30." Dill also said another officer in the case had asked him to falsify a police report and that a bag containing sexual aids had been lost or destroyed. Edmond police Capt. Theresa Pfeiffer said Dill's contention about the falsified reports was "a blatant lie. As for the trick bag, this is the first I've heard of it."

Robert Jackson, an attorney representing Slaughter, said that he's concerned there are too many questions about the case and asked the board to recommend clemency so the governor could look at it. Since clemency was denied by the board, the governor will not get that opportunity, Jackson said. Slaughter's case has been heard in state, as well as federal courts. Some of the evidence, such as a DNA test of a single hair found at the crime scene, was not admitted during Slaughter's appeals.

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

Jimmy Ray Slaughter - Oklahoma March 15, 2005

The state of Oklahoma is scheduled to execute Jimmie Ray Slaughter, a white man, March 15 for the 1994 murder of Melody Wuertz and his 11-month-old daughter Jessica Wuertz in Oklahoma County. Post-conviction developments now undermine the key evidence which was presented at trial. Slaughter maintains his innocence. He was convicted largely on what now consists of circumstantial evidence, and the testimony of prison informants and unreliable eye witness testimony.

Dennis Dill, a retired Edmond police office and initial lead investigator on the case,also concedes Slaughter may be innocent. He reportedly stated if the state were to carry out the execution, they will be killing an innocent man. “If they do this, they might just as well take him out and lynch him” Dill stated. He contends he was taken off the case because he didn’t feel the investigation was being conducted properly and that police had wrongly focused on Slaughter to the exclusion of other suspects.

An FBI scientist testified the manner the murder was carried out suggested the crime was an act of domestic violence. There was another suspect who had both a sexual history with the victim and a history of domestic violence. His alibi was shown to be false and he disappeared a few days after the crime. This lead was not further investigated.

The physical evidence which may have pointed to Slaughter at trial has since been refuted or called into question. During the trial, the prosecution argued that a hair found at the crime scene belonged to Vicki Mosley. However, DNA testing of the hair conducted by Mitotyping Techonologies, an independent lab hired by the defense, has shown it did not belong to her. The state appeals court did not allow this new DNA evidence to be added to Slaughter’s latest appeal because the deadline had passed.

Similarly, the technology used to establish that the bullets located at the crime scene came from the same batch found in Slaughter’s possession is now unreliable. The state used a process known as Comparative Bullet Lead Analysis to determine the origin of the bullet. Experts have called this type of analysis into question citing it as unreliable.

Slaughter also presented an alibi at his trial. He was stationed in Fort Riley, Kansas in the U.S. Army Reserve approximately a four hour drive from Edmond Oklahoma. Slaughter’s ex-wife, Nicki Bonner and her two daughters testified he was with them all day. A salesperson at a nearby shopping mall recalled seeing Slaughter buy a T-shirt. A receipt verified the purchase.

Slaughter’s attorneys are arguing that a new science called “brain fingerprinting “ proves Slaughter is innocent. This technology, while still in an experimental phase, shows Slaughter has no memory of vital information the person responsible for the murders would know.

The death penalty is always an inappropriate response to violence. However, it is particularly disturbing when “evidence” against a defendant is highly disputable and unclear. Please contact the state of Oklahoma requesting a halt the Jimmy Ray Slaughter’s execution.

"Oklahoman Executed Despite 'Brain Fingerprinting'" (Tue Mar 15, 2005 09:40 PM ET)

MCALESTER, Oklahoma (Reuters) - An Oklahoma man who tried to prove his innocence through a little-known procedure called "brain fingerprinting" was executed by lethal injection on Tuesday for the 1991 murder of a woman and her daughter.

Jimmy Ray Slaughter, 57, insisted he was not guilty even as the mix of lethal chemicals was injected into his arms at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester. "I've been accused of murder and it's not true. It was a lie from the beginning," he said while strapped to a gurney in the Oklahoma death chamber. "You people will know it's true some day. May god have mercy on your souls."

Slaughter sighed heavily as the chemicals flowed into his body and his face lost all color. He was pronounced dead in the first execution this year in Oklahoma.

Slaughter was condemned for the July 2, 1991, murders of his girlfriend Melody Wuertz, 29, and their 11-month-old daughter, Jessica, whom he killed in a fit of anger when Wuertz filed a paternity suit against him, prosecutors said.

Slaughter tried to get his conviction overturned by submitting to a "brain fingerprinting" test by Seattle-based neuroscientist Larry Farwell. In the procedure, which the Harvard-educated Farwell says is accurate but has yet to gain much legal acceptance, the suspect is fitted with a headband-like sensor device, then shown photographs and other evidence from the crime scene. Seeing something familiar is said to trigger brain waves of recognition, which the sensor detects and flashes on a computer screen. Farwell told the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board in February that test results indicated Slaughter had not committed the crime, but the board members refused to grant him clemency. His fate was sealed when U.S. Supreme Court rejected his appeal on Tuesday.

Slaughter's three daughters from an earlier marriage witnessed the execution and wept as they watched their father die. He raised his head before the chemicals took hold and tried to comfort them, saying, "It's OK, it's OK, I love you."

Slaughter was the 76th person executed in Oklahoma since the state resumed capital punishment in 1991, 15 years after the U.S. Supreme Court lifted a national death penalty ban.

For his final meal, he requested fried chicken, mashed potatoes, cole slaw, biscuits, apple pie and cherry limeade.

"Family's nightmare ends as murderer executed," by Doug Russell. (Wednesday, March 16, 2005 11:20 AM)

A family's 14-year nightmare ended Tuesday with the execution of a double murderer at Oklahoma State Penitentiary. Jimmie Ray Slaughter was pronounced dead at 6:19 p.m., ending a long period of torment for family members of murder victims Melody and Jessica Wuertz.

"This is the end of a nightmare," Wesley Wuertz said after the execution. "There's no more waiting for the next appeal, no more wondering if a technicality will get him off. Š What he got tonight was justice."

But the 57-year-old inmate never said he was sorry for what he had done. Instead, he continued to proclaim his innocence as his three daughters sobbed softly in the witness room of the state's execution chamber. "I've been accused of murder and it's not true," the 57-year-old inmate said. "It was a lie from the beginning. God knows it's true. My children who were with me know it's true. And you people will know it's true some day. "May God have mercy on your souls." He told each of his daughters and his fiancé, whom he had met while on death row, that he loved them and "I'll be seeing you soon."

Slaughter kept his head raised from the gurney to which he was strapped for almost a minute after the warden ordered the execution to begin, mouthing words at the women who sat crying in the front row of the witness chamber, then lowered his head as the first of three drugs took effect. A muffled "Daddy" and wracking sobs. There was no further sound.

Neither had there been any sound in the minutes leading up to the execution, when death row inmates typically bang on their cell doors, whistle and whoop as a kind of "last sendoff" for an inmate they like. Sometimes the banging and whistling is so loud it can be heard in the death chamber's witness room. Other times it's more muted, but can still be heard in the law library of H Unit, the portion of the prison that houses death row. At times the banging, whistling and whooping begins a half hour before the scheduled execution time and continues until long after the inmate is pronounced dead. But there was none of that Tuesday. Just silence.

Earlier the U.S. Supreme Court had rejected a request from Slaughter's attorneys for a stay of execution. The 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rejected an appeal on Monday and the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals had denied an appeal for Slaughter on Thursday.

Attorneys had argued that a hair found at the crime scene didn't fit the prosecution's theory of the crime, but appellate courts found that a mountain of other evidence did. In addition, Slaughter's attorneys said that bullet lead analysis, which was used to help identify the bullets used in the murders, was not as accurate as had been previously believed. They also said that a new technology called "brain fingerprinting" had indicated Slaughter didn't have knowledge of the crime, but Assistant Attorney General Seth Branham called the technology "junk science," adding that the brain waves of anyone who had sat through a trial and seen the crime scene photographs, as Slaughter had, should show they had some knowledge of the crime.

The Wuertz family's long nightmare began on July 2, 1991, when the family members learned the 29-year-old mother and her daughter, who was five days shy of her first birthday, had been murdered in Edmond.

Melody Wuertz was a strong woman who wouldn't let life get her down, even though she'd been diagnosed with epilepsy and put on anticonvulsants in the seventh grade. She took part in school plays, concerts and musicals, eventually earning a music degree in college. Still, when she packed her belongings into a moving van and drove to Oklahoma for a new job, the family members in Indiana and Kentucky were a little nervous.

That tension grew after she returned home for her 10th high school reunion in 1989. Her self esteem plummeted. While others in her class had families and had become successful, Melody "felt she had failed," said her mother, Susie Wuertz. That's when Jimmie Ray Slaughter entered the picture. "We were very disturbed about it," Susie Wuertz said. "He'd been married three times and was so much older than her."

The family had no way of knowing it at the time, but the psychiatric nurse and Army Reserve officer had a long history of befriending young women, then manipulating them into sexual relationships and trying to control them, according to police. Police say one female doctor with whom he'd had a 10-year relationship had seven abortions after becoming pregnant with Slaughter's children. But Melody refused to get an abortion and even stopped taking her anticonvulsants for fear they might hurt her baby.

When she learned Slaughter was married, she called his house, enraging him. That rage grew after Jessica was born and she went through the Department of Human Services to collect child support. Melody Wuertz grew afraid of Slaughter. Police records indicate she told several people she was worried he might try to hurt her or Jessica and that she was planning to change the locks on her doors because he still had a key. "She was right to be worried," Edmond police Capt. Theresa Pfeiffer said later.

Slaughter set up an elaborate plan to get rid of Melody and Jessica. He had another woman he'd manipulated get him a pair of soiled men's underwear and hair clippings from an African American patient at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Oklahoma City. "He was the predator, she was the prey," Susie Wuertz said Tuesday. "He manipulated her just like he had so many others in his life and, I feel, like he manipulated his own daughters tonight."

Slaughter had maintained he was in Kansas at the time of the murders, that he was shopping with his wife and daughters in Topeka. Police said that Slaughter's alibi didn't hold up, that store employees remembered Slaughter's wife and daughters on that day but not him.

Instead of shopping, prosecutors said, Slaughter drove from Fort Riley, Kan., where he had been stationed after being activated for the First Gulf War, to Edmond, killed Melody and Jessica Wuertz, then drove back to Kansas, leaving the hair and underwear at the scene. There was no forced entry, indicating to police the door had either been unlocked or that the person who committed the crime had a key.

Investigators began with a list of 10 suspects, but the more they investigated, the more the evidence pointed to Slaughter as the killer. For one thing, Slaughter kept trying to get police to investigate the possibility an African American had raped and killed Melody and mutilated her body, as well as killed Jessica. "We knew at the time it was a staged domestic homicide," prosecutor Richard Wintory said. "There were several important things that made it clear this crime wasn't done by a black guy or a lust murderer."

For his last meal, Slaughter ate fried chicken, mashed potatoes, cole slaw, biscuits with honey butter, an apple pie, one pint of cherry ice cream and a large cherry limeade.

"Man executed protesting his innocence." (Tuesday, March 15, 2005 8:47 PM EST)

MCALESTER, Oklahoma (Reuters) -- An Oklahoma man who tried to prove his innocence through a little-known procedure called "brain fingerprinting" was executed by lethal injection Tuesday for the 1991 murder of a woman and her daughter.

Jimmy Ray Slaughter, 57, insisted he was not guilty even as the mix of lethal chemicals was injected into his arms at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester. "I've been accused of murder and it's not true. It was a lie from the beginning," he said while strapped to a gurney in the Oklahoma death chamber. "You people will know it's true some day. May god have mercy on your souls." Slaughter sighed heavily as the chemicals flowed into his body and his face lost all color. He was pronounced dead in the first execution this year in Oklahoma.

Slaughter was condemned for the July 2, 1991, murders of his girlfriend Melody Wuertz, 29, and their 11-month-old daughter, Jessica, whom he killed in a fit of anger when Wuertz filed a paternity suit against him, prosecutors said.

Slaughter tried to get his conviction overturned by submitting to a "brain fingerprinting" test by Seattle-based neuroscientist Larry Farwell. In the procedure, which the Harvard-educated Farwell says is accurate but has yet to gain much legal acceptance, the suspect is fitted with a headband-like sensor device, then shown photographs and other evidence from the crime scene. Seeing something familiar is said to trigger brain waves of recognition, which the sensor detects and flashes on a computer screen.

Farwell told the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board in February that test results indicated Slaughter had not committed the crime, but the board members refused to grant him clemency. His fate was sealed when U.S. Supreme Court rejected his appeal Tuesday. Slaughter's three daughters from an earlier marriage witnessed the execution and wept as they watched their father die. He raised his head before the chemicals took hold and tried to comfort them, saying, "It's OK, it's OK, I love you."

Slaughter was the 76th person executed in Oklahoma since the state resumed capital punishment in 1991, 15 years after the U.S. Supreme Court lifted a national death penalty ban.

For his final meal, he requested fried chicken, mashed potatoes, cole slaw, biscuits, apple pie and cherry limeade.

"State executes Guthrie man for double murder," by Sean Murphy. (AP 3/15/05)

McALESTER, Okla. - When Melody Wuertz packed up her belongings in a moving truck and left Indiana for a new job in Oklahoma City, Lyle and Susie Wuertz were a little nervous about their daughter being on her own in a strange city. Their nervousness grew when they learned Melody was involved with Jimmie Ray Slaughter, a man who'd been married three times and was more than 10 years her senior. Their misgivings proved to be well founded.

Slaughter, who fathered a child with Melody Wuertz, was accused and ultimately convicted of shooting, stabbing and mutilating her and fatally shooting their daughter, Jessica, in their Edmond home in 1991.

On Tuesday, the Wuertzes traveled from Montgomery, Ind., to witness Slaughter's execution at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary. He was pronounced dead at 6:19 p.m. after receiving a lethal mixture of drugs. Strapped to a gurney that was positioned parallel to the window separating the death chamber from the witnesses, Slaughter tilted his head so that he could smile at his three grown daughters. "It's OK," he told them as they cried softly.

Slaughter maintained his innocence to the end. "I've been accused of murder and it's not true," Slaughter said as his fiancee, whom he met while on death row, and a death penalty opponent who befriended Slaughter in prison, also looked on. "It was a lie from the beginning. God knows it's true, my children who were with me know it's true and you people will know it's true someday. May God have mercy on your souls." Slaughter had maintained he was in Kansas with his family when the murders occurred. After his final statement, Slaughter exhaled deeply and closed his eyes. As the mixture entered his system through an IV in his left arm, the color left his face. His mouth and eyes were slightly open when he was pronounced dead.

"This is the end of a long nightmare," said Melody's brother Wes Wuertz, of Elizabethtown, Ky. "There's no more waiting for the next appeal. There's no wondering if a technicality will get him off."

The U.S. Supreme Court rejected a request by Slaughter's attorneys for a stay of execution earlier Tuesday. The 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals denied an appeal on Monday and the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals rejected an appeal for Slaughter on Thursday. His attorney, Robert Jackson, had argued recently that new DNA evidence conducted on a hair found on one of the victims didn't connect Slaughter with the crimes, a theory that prosecutors argued during Slaughter's original trial.

Jackson also disputed an analysis of bullets found in the victims that he says were linked to Slaughter through an outdated technology called comparative bullet lead analysis. A neuroscientist testified that Slaughter's brainwave patterns and recollection of the rooms where the bodies of Wuertz and her child were found were not consistent with someone who would have committed the crime.

Former Oklahoma County prosecutor Richard Wintory, who helped prosecute Slaughter at his original trial, discounted as nonsense the brain fingerprinting defense, calling it "snake oil." "This is not a close case on the facts," said Wintory, who traveled from Arizona to attend the execution. "Jimmie Ray Slaughter perpetrated one of the most evil crimes that has ever blotted the peace and dignity of my home state."

For his last meal, Slaughter ate fried chicken, mashed potatoes, cole slaw, biscuits with honey butter, an apple pie, one pint of cherry ice cream and a large cherry limeade, a prison spokeswoman said.

Slaughter v. State, 2005 WL 562759 (Okl.Cr.App 2005) (3rd PCR).

Background: After convictions and death sentences for capital murder were affirmed on direct appeal, 950 P.2d 839, denial of defendant's initial petition for post-conviction relief was affirmed, 969 P.2d 990, and defendant exhausted federal habeas claims, defendant filed second petition for post-conviction relief. The Court of Criminal Appeals, 105 P.3d 832, denied relief. Defendant filed third petition.

Holdings: The Court of Criminal Appeals, Lumpkin, V.P.J., held that:

(1) defendant was not entitled to successive post-conviction review of claim that new evidence of brain fingerprinting would demonstrate actual innocence;

(2) defendant was not entitled to successive post-conviction review of claim that recent DNA testing would demonstrate actual innocence;

(3) defendant was not entitled to post-conviction review of claim that comparative bullet lead analysis methodology was being challenged in relevant scientific community;

(4) defendant was not entitled to post-conviction relief on claims that direct appeal counsel was ineffective for failing to secure DNA testing of "single hair used to convict" him of murder while appeal was pending; and

(5) defendant was not entitled to post-conviction relief on claims that post-conviction statute and criminal appellate rule governing limitations periods were unconstitutional. Denied.

Lumpkin, Judge:

Petitioner Jimmie Ray Slaughter was convicted of two counts of First Degree Murder in the District Court of Oklahoma County, Case Number CF-1992-82. He was sentenced to death. [FN1] Petitioner appealed to this Court in Case No. F-1994-1312. We affirmed his convictions and sentences. Slaughter v. State, 1997 OK CR 78, 950 P.3d 839. Rehearing was denied on February 23, 1998. The United States Supreme Court denied certiorari review on October 5, 1998. Slaughter v. Oklahoma, 525 U.S. 886, 119 S.Ct. 199, 142 L.Ed.2d 163 (1998).

Petitioner filed his first post-conviction application, but we denied relief. Slaughter v. State, 1998 OK CR 63, 969 P.2d 990. The Federal District Court and 10th Circuit Court of Appeals denied habeas relief, and the U.S. Supreme Court denied certiorari. Slaughter v. Mullin, 541 U.S. 947, 124, S.Ct. 1681, 158 L.Ed.2d 374 (2004).

In March of 2004, Petitioner filed his second application for post-conviction relief. We denied relief in January of 2005. Slaughter v. State, 2005 OK CR 2, 105 P.3d 832. [FN2] Petitioner then filed this, his third application for post-conviction relief, on January 27, 2005, raising essentially the same issues raised in his second application for post-conviction relief.

* * * *

After carefully reviewing Petitioner's third application for post-conviction relief, motion for evidentiary hearing, motion for discovery, and motion for stay of execution, we find relief is not warranted, and therefore said application and motions are HEREBY DENIED.

Slaughter v. State, 105 P.2d 832 (Okl.Cr.App. 2005) (2nd PCR).

Background: Petitioner was convicted in the District Court, Oklahoma County, Thomas C. Smith, Jr., J., of first-degree murder of former girlfriend and their child and was sentenced to death. Petitioner appealed. The Court of Criminal Appeals, Lumpkin, V.P.J., 950 P.2d 839, affirmed. Petitioner filed a second petition for post-conviction relief.

Holdings: The Court of Criminal Appeals, Lumpkin, V.P.J., held that:

(1) affidavit and evidentiary materials based on "Brain Fingerprinting" did not warrant evidentiary hearing and were procedurally barred;

(2) claims relating to DNA testing were barred from review by failure to submit any supporting DNA evidence with original or second post-conviction applications; and

(3) request to supplement post-conviction application with an entirely new claim and supporting documentation to challenge bullet composition analysis was untimely. Denied.

LUMPKIN, Vice-Presiding Judge.

Petitioner Jimmie Ray Slaughter was convicted of two counts of First Degree Murder in the District Court of Oklahoma County, Case Number CF-1992-82, and sentenced to death. [FN1] He appealed his conviction to this Court in Case No. F-1994-1312. We affirmed his convictions and sentences. Slaughter v. State, 1997 OK CR 78, 950 P.2d 839. Rehearing was denied on February 3, 1998. The U.S. Supreme Court denied certiorari review on October 5, 1998. Slaughter v. Oklahoma, 525 U.S. 886, 119 S.Ct. 199, 142 L.Ed.2d 163 (1998).

FN1. Petitioner was also convicted of five counts of perjury in this case and sentenced to consecutive terms of two, four, five, three, and one years imprisonment.

Petitioner filed his first application for post-conviction relief on April 3, 1998. We denied relief. Slaughter v. State, 1998 OK CR 63, 969 P.2d 990. Thereafter, the Federal District Court and Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals denied habeas corpus relief, and the United States Supreme Court denied certiorari. See Slaughter v. Mullin, --- U.S. ----, 124 S.Ct. 1681, 158 L.Ed.2d 374, 2004 WL 194344 (U.S. March 22, 2004).

On March 19, 2004, Petitioner filed this, his second application for post-conviction relief, along with a motion for evidentiary hearing. The State filed its response to the second application for post-conviction relief on April 16, 2004.

* * *

Attached to the post-conviction application, Petitioner has presented Dr. Farwell's affidavit, indicating Dr. Farwell conducted Brain Fingerprinting testing on Petitioner on February 9-10, 2004. At that time, Dr. Farwell allegedly asked numerous details concerning "salient details of the crime scene that, according to [Petitioner's] attorneys and the records in the case, ... the perpetrator experienced in the course of committing the crime for which Mr. Slaughter was convicted." [FN3] According to Dr. Farwell, Petitioner's brain response to that information indicated "information absent." To Dr. Farwell, this reading indicates Petitioner does not have knowledge of these "salient features of the crime scene." Dr. Farwell indicates the statistical "confidence" of the Brain Fingerprinting test result is not less than 99%. He further indicates it is not possible to fake the results of the testing.

FN3. We have been provided no information, however, as to what those salient details may be, how or by whom they were formulated, or how they were communicated.

In his March 2004 affidavit, Dr. Farwell indicated he was preparing a comprehensive report detailing the nature of the test, the manner in which it was administered, and the results, which would be made available in the next few weeks. Six months have now passed, however, and this Court has received no such report.

Dr. Farwell makes certain claims about the Brain Fingerprinting test that are not supported by anything other than his *835 bare affidavit. He claims the technique has been extensively tested, has been presented and analyzed in numerous peer-review articles in recognized scientific publications, has a very low rate of error, has objective standards to control its operation, and is generally accepted within the "relevant scientific community." These bare claims, however, without any form of corroboration, are unconvincing and, more importantly, legally insufficient to establish Petitioner's post-conviction request for relief. Petitioner cites to one published opinion, Harrington v. State, 659 N.W.2d 509 (Iowa 2003), in which a brain fingerprinting test result was raised as error and discussed by the Iowa Supreme Court ("a novel computer-based brain testing"). However, while the lower court in Iowa appears to have admitted the evidence under non-Daubert circumstances, the test did not ultimately factor into the Iowa Supreme Court's published decision in any way.

Pursuant to Rule 9.7(D)(1)(a), Rules of the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals, Title 22, Ch. 18, App. (2004), affidavits and evidentiary materials filed in support of a post-conviction application are not part of the trial record but are only part of the capital post-conviction record. As such, those affidavits and evidentiary materials are not reviewed on their merits but are reviewed: [T]o determine if a threshold showing is met to require a review on the merits. If this Court determines that the requirements of Section 1089(D) of Title 22 have been met and issues of fact must be resolved by the District Court, it shall issue an order remanding to the District Court for a hearing on the merits of the claim raised in the application.

Furthermore, post-conviction petitioners seeking a review of their post-conviction affidavits are required to file an application for evidentiary hearing. Rule 9.7(D)(5), Rules of the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals, Title 22, Ch. 18, App. (2002). The application for evidentiary hearing and affidavits "must contain sufficient information to show this Court by clear and convincing evidence the materials sought to be introduced have or are likely to have support in law and fact to be relevant to an allegation raised in the application for post-conviction relief." Id. If this Court determines "the requirements of Section 1089(D) of Title 22 have been met and issues of fact must be resolved by the District Court, it shall issue an order remanding to the District Court for an evidentiary hearing." Rule 9.7(D)(6), Rules of the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals, Title 22, Ch. 18, App. (2002).

Here, we find these affidavits and evidentiary materials do not contain sufficient information to show this Court by clear and convincing evidence that the materials sought to be introduced have or are likely to have support in law and fact to be relevant to his claim of factual innocence. What we have are some interesting, indeed startling, claims that are not backed up with enough information for us to act on them.

First and foremost, we have been provided no concrete evidence of Petitioner's Brain Fingerprinting claim. No written report has been submitted to this Court. None of the testing details or results have been provided.

Secondly, beyond Dr. Farwell's affidavit, we have no real evidence that Brain Fingerprinting has been extensively tested, has been presented and analyzed in numerous peer-review articles in recognized scientific publications, has a very low rate of error, has objective standards to control its operation, and/or is generally accepted within the "relevant scientific community." The failure to provide such evidence to support the claims raised can lead to no other conclusion, for post-conviction purposes, but that such evidence does not exist.

Third, the post-conviction record actually refutes some of Petitioner's claims. While Petitioner claims Brain Fingerprinting was not available to anyone in the world before July 1, 1999, the State's exhibits and indeed some of Dr. Farwell's own published articles indicate the science has been around for many years, at least since 1995 and probably for more than a decade before that. [FN4] Furthermore, an October 2001 report from the United States General Accounting Office to U.S. Senator Charles E. Grassley, reveals Dr. Farwell's acknowledgement that "MERMER has not undergone independent peer review testing and is not well accepted in the scientific community."

FN4. The so-called "P-300" component of Brain Fingerprinting has apparently been recognized by the scientific community for many years, but Dr. Farwell's test also measures the "MERMER" effect.

Fourth, we find some merit in the State's argument that the "salient" facts of the crime were introduced at Petitioner's trial through a technical investigator and crime scene reconstruction expert. Petitioner, who was present during this testimony, and his alleged negative response to such information during Brain Fingerprinting testing is, at the very least, curious.

Therefore, based upon the evidence presented, we find the Brain Fingerprinting evidence is procedurally barred under the Act and our prior cases, as it could have been raised in Petitioner's direct appeal and, indeed, in his first application for post-conviction relief. We further find a lack of sufficient evidence that would support a conclusion that Petitioner is factually innocent or that Brain Fingerprinting, based solely upon the MERMER effect, would survive a Daubert analysis.

* * *

After carefully reviewing Petitioner's Application for post-conviction relief, motion for evidentiary hearing, and other filings we find Petitioner's Second Application for Post-Conviction Relief, Motion for Evidentiary Hearing, Motion to Hold Post-Conviction Case in Abeyance, and Requests to Supplement are DENIED.

Slaughter v. State, 969 P.2d 990 (Okl.Cr. 1998) (PCR).

After his conviction of first-degree murder and death sentence were affirmed on direct appeal by the Court of Criminal Appeals, 950 P.2d 839, petitioner filed application for postconviction relief. The Court of Criminal Appeals, Lumpkin, J., held that: (1) most claims were either waived by failure to raise them on direct review of barred by res judicata to extent they were raised; (2) ineffective assistance of counsel claims were either waived, barred or meritless, notwithstanding fact that petitioner had same counsel for trial and appeal; and (3) petitioner was not entitled to additional discovery. Application denied. Chapel, P.J., and Strubhar, V.P.J., concurred in results.

LUMPKIN, Judge:

Petitioner Jimmie Ray Slaughter was convicted of two (2) counts of First Degree Murder (21 O.S.1991, § 701.7) and five (5) counts of Perjury (21 O.S.1991, § 491), Case No. CF-92-82, in the District Court of Oklahoma County. The jury found the existence of one aggravating circumstance in Count 1 and two aggravating circumstances in Count 2 and recommended the punishment of death. In Counts 3-7, the perjury counts, Petitioner received sentences of two (2), four (4), five (5), three (3), and one (1) years imprisonment respectively. This Court affirmed the judgments and sentences in Slaughter v. State, 950 P.2d 839 (Okl.Cr.1997). Petitioner filed his Original Application for Post-Conviction Relief in this Court on December 1, 1997, in accordance with 22 O.S.Supp.1995, § 1089.

* * *

In Proposition II, Petitioner contends that law enforcement and the prosecution failed to disclose certain crucial evidence in violation of Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83, 83 S.Ct. 1194, 10 L.Ed.2d 215 (1963) . Specifically, Petitioner alleges the following:

1. the original crime scene log was lost by the Edmond Police Department and a reconstructed log given to defense counsel;

2. the multi-page "Dill Report" was lost and an OSBI report (the "Rickey Report") was substituted;

3. a letter and its contents written by Detective Dill to Edmond Police Chief Vetter was concealed;

4. a tape recorded interview of Detective Dill by Prosecutor Richard Wintory was concealed;

5. also concealed was information that a neighbor of Melody Wuertz identified a vehicle similar to that driven by Rick Gulloto outside the Wuertz home in the early morning hours of July 2, 1991 and that Gullotto had no alibi for the early morning hours of July 2, 1991.

As in Proposition I, this claim is based upon the argument that the above information did not come to light until Detective Dill's civil trial, therefore it could not have been raised on direct appeal.

* * * After carefully reviewing Petitioner's Application for post-conviction relief, we *1000 conclude: (1) there exists no controverted, previously unresolved factual issues material to the legality of Petitioner's confinement; (2) Petitioner could have previously raised collaterally asserted grounds for review; (3) grounds for review which are properly presented have no merit; and (4) the current post-conviction statutes warrant no relief. 22 O.S.Supp.1995, § 1089(D)(4)(a)(1), (2) & (3). Accordingly, Petitioner's Application for Post-Conviction Relief is DENIED.

Slaughter v. State, 950 P.2d 839 (Okl.Cr. 1997) (Direct Appeal).

Defendant was convicted in the District Court of Oklahoma County, Thomas C. Smith, Jr., J., of two counts of first degree murder for killing former girlfriend and their child, and was sentenced to death. Defendant appealed. The Court of Criminal Appeals, Lumpkin, J., held that: (1) filing bill of particulars six months before trial constituted a "reasonable time" and gave defendant notice of what State would use to seek death penalty; (2) evidence of occult was relevant as there was admissible evidence to indicate murder was ritualistic slaying; (3)testimony concerning telephone conversation by defendant's girlfriend following discovery that she was named as cooperating with authorities in newspaper article was admissible as excited utterance; (4) finding aggravating circumstance of causing great risk of death of more than one person on each murder count did not violate double jeopardy and was supported by evidence; (5) finding that murder of girlfriend was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel was supported by evidence that defendant shot her, leaving her paralyzed, and then killed child in front of her; (6) death penalty statutes do not violate state Constitution; (7) introduction of improper evidence against witness and improper comments, uninvited and invited, by prosecution were harmless error; and (8) statutory aggravating circumstances coupled with trial evidence sufficiently outweighed mitigating evidence and supported death sentences. Affirmed. Chapel, P.J., concurred in result and filed an opinion in which Lane, J., joined and concurred in result. Strubhar, V.P.J., concurred in result.

LUMPKIN, Judge.

Appellant Jimmie Ray Slaughter was tried by a jury in the District Court of Oklahoma County, Case No. CF-92-82, and convicted of two counts of Murder in the First Degree (21 O.S.1991, § 701.7(A)). [FN1] Trial commenced on May 16, 1994 and continued until October 7, 1994, when the jury returned its verdict on punishment. [FN2] The prosecution sought the death penalty, alleging in each count that (1) the murder was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel (21 O.S.1991, § 701.12(4); (2) there existed a probability the defendant would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society (21 O.S.1991, § 701.12(7)); and (3) the defendant knowingly created a great risk of death to more than one person (21 O.S.1991, § 701.12(2)). Before the jury began second-stage deliberations, the prosecution dismissed the allegation that the murder charged in Count I was especially heinous, atrocious. As to Count 1, the jury found only that Appellant knowingly created a great risk of death to more than one person; it did not find that Appellant would be a continuing threat to society. As to Count 2, the jury found that the murder was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel and that Appellant knowingly created a great risk of death to more than one person; the jury did not find continuing threat. The trial court followed the jury's recommendations and sentenced Appellant to death on each count. We affirm. [FN3]

FN1. Appellant was also convicted of Count 3, Perjury (21 O.S.1991, § 491) (two years); Count 4, Perjury (21 O.S.1991, § 491) (four years); Count 5, Perjury (21 O.S.1991, § 491) (five years); Count 6, Perjury (21 O.S.1991, § 491) (three years); Count 7, Perjury (21 O.S.1991, § 491) (one year). The jury found Appellant not guilty on an eighth count of perjury. It appears Appellant does not contest these judgments and sentences on appeal.

FN2. I agree with my colleagues this is a long opinion. However, it reviews an exceptionally long trial. The parties have a right to know this Court has thoroughly reviewed the voluminous record presented on appeal, adjudicated the propositions of error based on the totality of the record, and is enunciating a clear decision on each of those issues supported by the law and facts. Through this process, we ensure confidence that our decisions are based on the rule of law and are not merely result oriented.

FN3. Appellant's Petition in Error was filed in this Court on June 9, 1995. Appellant's brief was filed July 1, 1996, and the State's brief was filed October 29, 1996. The case was submitted to the Court October 30, 1996. Oral argument was held August 12, 1997.

At "right around noon" on July 2, 1991, Ginger Neal noticed that her pitbull dog, Ozie, was barking and acting strangely in the back yard. Ozie was somewhat skittish, more so around adults than with children. The dog was in such a hurry to get into the house that he practically ran over a child on his way to his place of refuge in the house. Ms. Neal was sufficiently concerned to glance out in the back yard to see if an intruder were present; she saw nothing. A few minutes later, she heard a noise, as if a car were backfiring or a firecracker had exploded. As Independence Day was only two days away, she thought nothing of the noise. Rhonda Moss, who lived in the same house as Ms. Neal, also heard the noise. At least one other neighbor also heard the backfiring noise. Neither Ms. Moss nor Ms. Neal *845 thought much about it until the bodies of Melody Wuertz and her 11- month-old daughter, Jessica, were found early that same evening in the house next door.

Melody was found on the floor in her bedroom. She had been shot once in the cervical spine and once in the head. In addition, she had been stabbed in the chest and in her genitalia; and there were carvings on her abdomen and breasts which authorities interpreted as symbols of some kind. A comb filled with Negroid hairs, some underwear containing Negroid head hairs, some unused condoms and some gloves were found near Melody's body. No seminal fluid was found in or on Melody. In the bathroom, Melody's curling iron was still plugged in. Baby Jessica was found in the hallway; just days shy of her first birthday, she had been shot twice in the head. The medical examiners who examined the bodies estimated time of death to be approximately between 9:30 a.m. and 12:15 p.m. on July 2.

The prosecution's theory was that Melody was surprised while in the bathroom as she was preparing for work (the evening shift at the Oklahoma City Veterans Administration Hospital); was then paralyzed (but not rendered unconscious) by the shot to the cervical spine; was forced to lie paralyzed and conscious as her child was killed; then was dragged to the bedroom, where she was killed by the shot to her head. The killer then planted the evidence in an attempt to throw investigators off the trail.

Appellant (a nurse at the VA Hospital) was a suspect from the very beginning. He and Melody had had a sexual relationship, the result of which Melody became pregnant. Appellant signed an affidavit acknowledging paternity on July 17, 1990, ten days after Jessica was born. Despite this acknowledgment, Appellant's support of the child was meager, a fact Melody mentioned more than once. Melody's insistence on getting Appellant to provide monetary support for her child irritated him. He once remarked to a co-worker at the hospital that Melody was getting "pushy," and if she continued to act that way, he would have to kill her. To another, he said Melody was causing him problems at work, and one day he would have to kill both Melody and Jessica. Appellant was concerned a paternity action by Melody could jeopardize his status as a reserve officer in the Army; additionally, Appellant was married, and his wife did not know about the affairs with Melody and other women. In the fall of 1990, Appellant was called to active duty during the Desert Storm military operation, and was stationed at Ft. Riley, Kansas. He remained on active duty there until mid-July, 1991. During this period, what scant payments Appellant had made to Melody stopped. This forced Melody to seek child support through the Department of Human Services, an action which enraged Appellant. Before her death, Melody expressed to several people her fear that Appellant would take action against her because she had initiated child support proceedings against him.

Appellant presented an alibi defense. He presented evidence purporting to show he was with his family shopping in Topeka, Kansas, at the time of the murders. Other facts will be presented as they become relevant.

* * *

We find that these statutory aggravating circumstances, coupled with all the evidence from both stages of trial, sufficiently outweigh the mitigating evidence presented by Appellant at trial. We examined the errors contained in the trial above, and find the sentence of death was not imposed under the influence of passion, prejudice or any other arbitrary factor.

Slaughter v. Mullin, 68 Fed.Appx. 141, Slip Copy, 2003 WL 21300287 (10th Cir. 2003) (Habeas).

State inmate, convicted on two counts of first-degree malice murder and sentenced to death, petitioned for writ of habeas corpus. The United States District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma denied the petition, and inmate appealed. The Court of Appeals, Murphy, Circuit Judge, held that: (1) inmate exhausted his state court remedies; (2) state procedural bar did not preclude federal habeas review; (3) trial counsel's representation was not deficient; (4) appellate counsel was not ineffective in failing to assert ineffective-trial-counsel claim; and (5) evidence was sufficient to support finding that victim's death was especially heinous, atrocious or cruel, as warranted imposition of two death sentences. Affirmed.

MURPHY, Circuit Judge.

Petitioner-appellant Jimmie Ray Slaughter, a state prisoner, appeals the district court's decision denying him habeas relief from his two Oklahoma first-degree malice murder convictions and death sentences. A jury convicted Slaughter of shooting, stabbing and mutilating his former girlfriend, Melody Wuertz (Wuertz), and shooting to death their eleven-month old-daughter, Jessica. [FN1] On appeal, Slaughter contends both that his trial attorneys' first-phase representation was constitutionally deficient because counsel did not try to implicate a different, alternate suspect and that there was insufficient evidence to support the jury's second-phase finding that his killing Wuertz was especially heinous, atrocious or cruel. This court affirms the denial of habeas relief under 28 U.S.C. § 2254.

FN1. The jury also convicted Slaughter on five counts of perjury, based on testimony he gave before the grand jury investigating these deaths. Slaughter does not challenge these perjury convictions in this proceeding.

I. FACTS

On July 2, 1991, Melody and Jessica Wuertz were each shot twice and killed. The killer also stabbed Wuertz and mutilated her body. Suspicion immediately centered on Slaughter, Jessica's father, who was at that time embroiled in a contentious paternity and child-support dispute with Wuertz.

Slaughter worked as a nurse at the Veterans' Administration (VA) Hospital in Oklahoma City. In approximately July 1989, Slaughter, who was married, began an extramarital affair with Wuertz, who also worked at the VA hospital. Slaughter, however, apparently never told Wuertz he was married. In July 1990, Wuertz gave birth to Jessica. Soon thereafter, Slaughter, who was an Army reservist, volunteered for active duty during the Gulf War. He was stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas, about a four-and-a-half-hour drive from Wuertz's home in Edmond, Oklahoma. Before leaving for active duty, Slaughter remarked to a co-worker that "he was actually glad to be leaving ... and that he was especially glad to get away from Melody because she was getting pushy, and if she kept pushing [him], [he'd] have to kill her." Trial tr., July 19, 1994, at 81. Slaughter further asserted that he could kill Wuertz without getting caught; "they would know who did it but they would never be able to prove it," id., July 21, 1994, at 122.

In late October 1990, Wuertz discovered Slaughter was married. In fact, she called Slaughter's wife to tell her about Slaughter's infidelity. Slaughter was furious with Wuertz for this, but managed to explain to his wife that this must have been a prank call, probably made by one of his former wives. Slaughter later told a co-worker in Kansas that "his wife did not know about" Jessica and "he would do anything to keep [her] from finding out." Id., Sept. 12, 1994, at 87. Although Wuertz had previously considered filing a paternity suit against Slaughter, she had not yet done so because she feared that this would drive him away and they would never marry, as she had hoped. Aware now that Slaughter was already married to someone else, Wuertz sought the Oklahoma Department of Human Services' (DHS) help in collecting child support from him. Slaughter, however, had previously told Wuertz that if she ever pursued such a child-support proceeding, he would kill both Wuertz and the baby. Numerous witnesses testified to Slaughter's rage stemming from Wuertz's commencing those proceedings. On at least one occasion, Slaughter told his then girlfriend in Kansas that he wished Wuertz were dead.

While still in Kansas, Slaughter was able to keep tabs on Wuertz's progress with the paternity proceedings through another of his paramours, Cecilia Johnson. Johnson was also a nurse at the Oklahoma City VA hospital, and Wuertz's apparent friend. Although having signed an affidavit soon after Jessica's birth admitting he was the child's father, Slaughter, in response to the paternity proceedings, denied paternity and submitted to blood tests. Those test results established that there was a 99.39% likelihood Slaughter was Jessica's father. Wuertz received those test results on June 19, 1990. Although DHS mailed those results to Slaughter at Fort Riley, via certified mail, and attempted to have the results served on Slaughter through the fort's Provost Marshal's office, Slaughter never officially received those test results. Nevertheless, Wuertz did share the test results with her co-workers. Slaughter testified that Cecilia Johnson, having heard the test results from Wuertz, probably did inform him of those results. Slaughter's grand jury testimony, Jan. 3, 1992, at 36 (played at trial, see Trial tr., Aug. 29, 1994, at 6). Slaughter called Wuertz during the early morning hours of Sunday, June 30, 1991, telling her there was no way that the baby was his, nor was there any way he was going to pay Wuertz anything. Minutes later, Johnson called Slaughter and they talked for over three and one-half hours. Wuertz was afraid to go home that night because she feared Slaughter would be there. The State theorized that Slaughter wanted to kill Wuertz and Jessica while he was still stationed in Kansas, so he could use that as an alibi. If so, he would soon run out of time to do so. Slaughter would be discharged from active duty within a week, and Wuertz and Jessica were to fly to her parents' home on July 3 for a two-week visit.

Wuertz and her daughter were killed July 2, 1991. The two medical examiners performing autopsies on the victims estimated they died somewhere between 10:00 a.m. and 2:00 p.m., and most likely around noon that day. Several of Wuertz's neighbors reported hearing what may have been gunshots sometime between 11:30 a.m. and 12:45 p.m. Additionally, neighbors living in the house right next door to Wuertz testified that, at around noon, their dog "went into chaos" and "went ballistic and [was] barking tremendously and was very scared." Trial tr., Aug. 2, 1994, at 118, 120. This was just before the neighbors heard what may have been a gunshot. The State theorized that the killer had hopped the fence to Wuertz's backyard, startling the neighbors' dog.

Wuertz's neighbors testified at trial that they had not seen any vehicles other than Wuertz's car at her home that morning. At 12:37 p.m., however, several young teenage boys walking down a street near the victims' home noticed a man fairly matching Slaughter's description, in a car parked away from the other houses, next to an open field. The boy walking closest to that car positively identified Slaughter as the man he saw, both in a photo lineup conducted soon after the murders and at Slaughter's trial, three years later. Further, a second boy also positively identified Slaughter at trial as the man he saw in the car.

Additionally, these two boys described the car they had seen as a bluish-gray, four-door vehicle which also generally matched Slaughter's car's description. And, although the second boy specifically identified the car he had seen as a Nissan, and Slaughter's car was, instead, a Dodge, both boys did pick Slaughter's car out of a photo lineup soon after the murders. Donald Stoltz, who had spent time with Slaughter in jail, corroborated the boys' identification, testifying Slaughter had told him that the kids who saw him, the day the murders occurred, mistakenly identified his car as a Japanese-made vehicle. According to Stoltz, Slaughter said he did not know why he had left his car window down; and that, if he had kept his tinted window raised, no one would have ever seen him.

The State's experts testified that the killer most likely entered Wuertz's home, using a key, and killed the victims in a "blitz-style attack." There was no sign of forced entry, yet Wuertz was very security conscious and always kept her house locked, even when she was inside. The confrontation between Wuertz and the killer appeared to have occurred solely in the hallway, rather than near the front door. Although Slaughter denied having a key to Wuertz's house, investigators found those keys in Slaughter's car the day after the murders.

Both victims had been shot twice with Eley brand .22 caliber long-rifle, subsonic, hollow-point bullets that had not been copper washed. This imported ammunition was quite rare, representing only one tenth of one percent of the total .22 caliber ammunition sold in the United States during 1990 and 1991. It could generally not be purchased in American gun shops, but instead had to be special ordered. Police found this same rare ammunition in Slaughter's gun safe in his Oklahoma home. Metallurgical tests indicated that the Eley ammunition in Slaughter's safe was elementally identical to the bullets that had killed the victims. According to the State's expert, this indicated that Slaughter's ammunition had been manufactured from the same piece of lead that produced the bullets that had killed the victims. Based on this information, the State argued the bullets that killed the victims had to come from the very same box of Eley ammunition found in Slaughter's gun safe.

Police could not use the bullets that had killed the victims to identify the murder weapon because those bullets were so badly damaged. According to the State's ballistics expert, this is a common phenomenon with .22 caliber ammunition. Slaughter, who collected guns, did own several .22 caliber weapons.

In addition to shooting each victim twice, the killer stabbed Wuertz once in the heart; deeply slashed both her breasts multiple times; scratched and cut her abdomen, including apparently inscribing a variation on the letter R; and inflicted a deep, nine-inch cut running from her vagina through her anal canal and lower back. The medical examiner testified that the killer had used a single-edged knife, at least six inches long and one-inch wide. Slaughter had a large collection of knives.

Although the killer planted evidence and arranged the crime scene to look like a sexual assault, police could find no physical evidence that a sexual assault had occurred. Nor did robbery appear to be a motive for the killings, as police found cash in plain sight near the bodies, and Wuertz's purse, with $140, had been left untouched. An FBI behavioral scientist testified that the manner in which the killer had carried out these murders suggested, instead, a domestic violence crime, carried out in a very controlled manner.

Evidence that the killer left at the crime scene included a comb, on which Negroid hairs had been bunched, and a pair of men's underwear. The comb was a type that was not generally available but sold for institutional use in such places as the Oklahoma City VA hospital and Fort Riley. Another Negroid hair was found on Wuertz's body. Cecilia Johnson admitted having collected these hairs, as well as the underwear, from a transient black man who had been a patient at the VA hospital the month before the murders. Johnson told a co-worker that she had collected these items at Slaughter's request and mailed them to him in Kansas. According to Johnson's co-worker, Slaughter "felt that he could confuse them at the scene" with these items. Trial tr., Aug. 16, 1994, at 74. There was evidence corroborating that Johnson had, in fact, mailed Slaughter a small package in early June 1991. After the murders, Slaughter, who disliked African-Americans, suggested to police and his co-workers that perhaps a black man or a black transient had killed the victims. At different times, Slaughter also suggested to police both that there had been a black man seen jumping fences in Wuertz's neighborhood and that Wuertz preferred to date African-American men. There was, however, no evidence to support either contention. Cecilia Johnson later suggested to a black co-worker, J.C. Sanders, that the planted evidence was actually meant to implicate Sanders in the murders.

On Wuertz's body, police also found a heavily-treated head hair, microscopically consistent with one of Slaughter's black co-workers at Ft. Riley. This co-worker, however, had never been to Oklahoma. Finally, two inmates, Dennis Hull and Lloyd Hunter, both testified that, while they were in jail with Slaughter, he confessed to them that he had killed the victims.

At trial, Slaughter propounded an alibi defense through his former wife, Nicki Bonner. Bonner, who was married to Slaughter at the time the murders occurred, testified that Slaughter had been in Kansas all day July 2, spending time with her and their two daughters, who were visiting him for the Fourth-of-July holiday. According to Bonner, on that day, Slaughter slept until 10:00 or 10:30 a.m. The family then ate lunch at the Country Kitchen restaurant, arriving between 12:30 and 1:00 p.m. The waitress there did recognize Bonner and her two daughters, and further testified that there was a man with them that day who looked similar to Slaughter. The waitress, however, never got a good enough look at the man's face to identify him. According to jailhouse informant Stoltz, Slaughter told him that maybe the waitress could not identify him because he was not at the restaurant that day. Rather, "it could have been a friend" eating with his family. Id. Aug. 4, 1994, at 79.

According to Bonner, the family drove around a nearby lake after lunch and then travelled an hour to Topeka to shop. A Walmart store clerk in Topeka remembered Slaughter buying his daughter a watch one afternoon, but could not pinpoint the exact date this had occurred. The sales clerk did remember that Slaughter had paid with a fifty dollar bill. Although Slaughter did not have the receipt for this purchase, the store's register tapes indicated that there was a sale of that particular type of watch at 3:26 p.m. on July 2, and that the customer had paid with a fifty-dollar bill. The defense argued that this must have been Slaughter's purchase.

The family also bought several other items at Walmart. The separate receipt for those items indicated that this second purchase occurred at 4:16 p.m. on July 2. The cashier who conducted this sale recognized Bonner and her older daughter, and she remembered there was a younger girl, too. The clerk, however, did not remember seeing a man with them that afternoon. Several other Kansas merchants, located in a mall near the Walmart, did remember seeing Slaughter later that afternoon, beginning just after 5:00 p.m. This, however, does not lend any further support to Slaughter's alibi. According to the parties' stipulation as to the mileage between the victims' home and this mall, if Slaughter had left Edmond soon after 12:30 p.m., he would have been able to drive from Edmond to the mall by 5:00 p.m.

At trial, Slaughter's attorneys supplemented his alibi defense by also arguing that it might have been Cecilia Johnson, acting on her own, who killed Wuertz and her baby. The trial court, nevertheless, instructed jurors that they could convict Slaughter of first-degree murder if they found that he had actually killed the victims or, alternatively, if they found, instead, that he had aided and abetted Cecilia Johnson in doing so. Jurors, then, convicted Slaughter of two counts of first-degree, malice-aforethought murder.

* * *

For these reasons, we, therefore, AFFIRM the district court's decision denying Slaughter federal habeas relief.