11th murderer executed in U.S. in 2006

1015th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

6th murderer executed in Texas in 2006

361st murderer executed in Texas since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

Robert Madrid Salazar Jr. H / M / 18 - 27 |

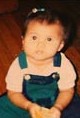

Adriana Gomez H / F / 2 |

Summary:

Raylene Blakeburn left her two-year-old daughter Adriana with her boyfriend Robert Salazar, while she went to work. When she returned home from work, she found Adriana in bed and unconscious, breathing abnormally with blood in her mouth. Salazar was not there because he and a friend had gone to buy beer. Returning from the store, Salazar and his friend saw an ambulance at his girlfriend’s house. They did not stop, but continued on to Salazar’s mother’s house to drink the beer they had purchased. Blakeburn called Salazar at his mother’s house, and he told her not to tell the police that he had been watching Adriana. Adriana died later that evening. Salazar later gave a written statement to the police admitting that he had been with Adriana while his girlfriend was at work. He claimed that while giving Adriana a shower, he became angry with her because she would not stop crying and he had used the back of his hand to push her down in the bathtub, causing her to fall down and hit her head. Salazar also claimed he had abandoned Adriana because he was scared. A pathologist testified that the back of Adriana’s head was caved in and there were also marks and bruises all over Adriana’s body. Adriana’s cause of death was multiple blunt force trauma obviously inconsistent with Salazar's story. Adriana’s chest injury surpassed what the pathologist had seen previously in automobile accident injuries; her heart was severely damaged; she suffered severe shaking injuries; several of her ribs were broken; and she suffered injuries consistent with some type of sexual penetration.

Citations:

Salazar v. State, 38 S.W.3d 141 (Tex.Crim.App. 2001) (Direct Appeal).

Salazar v. Dretke, 419 F.3d 384 (5th Cir. Tex. 2005) (Habeas).

In re Salazar, --- F.3d ----, 2006 WL 679018(5th Cir. 2006) (Successive Habeas).

Final Meal:

A dozen tamales, six brownies, refried beans with chorizo, two rollo candies, six hard shell tacos with lettuce, three big red sodas, ketchup, hot sauce, six jalapeno peppers, tomatoes, cheese, and extra ground beef.

Final Words:

"To everybody on both sides of that wall, I want you to know that I love you both. I am sorry that the child had to lose her life, but I should not have to be here. Tell my family I love them all and I will see them in heaven."

Internet Sources:

Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Executed Offenders (Robert Salazar)

Inmate: Salazar, Robert Jr.Date of Birth: 10/24/1978

TDCJ#: 999303

Date Received: 04/28/1999

Education: 9 years

Occupation: Laborer

Date of Offense: 04/23/1997

County of Conviction: Lubbock County

Race: Black

Gender: Male

Hair Color: Black

Eye Color: Brown

Height: 5 ft 07 in

Weight: 190

Texas Department of Criminal Justice

Texas Attorney General Media Advisory

MEDIA ADVISORY - Thursday, March 16, 2006 - Robert Salazar Scheduled For ExecutionAUSTIN – Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott offers the following information about Robert Madrid Salazar, who is scheduled to be executed after 6 p.m. Wednesday, March 22, 2006. A Lubbock County jury sentenced Salazar to death in March 1999 for murdering two-year-old Adriana Gomez.

FACTS OF THE CRIME

On the night of April 23, 1997, Raylene Blakeburn left her two-year-old daughter Adriana with her boyfriend Robert Salazar, while she went to work. When she returned home from work, she found Adriana in bed and unconscious, breathing abnormally with blood in her mouth. Salazar was not there because he and a friend had gone to buy beer. Returning from the store, Salazar and his friend saw an ambulance at his girlfriend’s house. They did not stop, but continued on to Salazar’s mother’s house to drink the beer they had purchased.

When paramedics arrived at the scene, they noted that the back of Adriana’s head was caved in. There were also marks and bruises all over Adriana’s body. Suspecting child abuse, the paramedics contacted the police. Adriana died later that evening.

Not long after discovering Adriana, Blakeburn called Salazar at his mother’s house, and he told her not to tell the police that he had been watching Adriana. Salazar later gave a written statement to the police. He admitted that he had been with Adriana while his girlfriend was at work. He claimed that while giving Adriana a shower, he became angry with her because she would not stop crying and he had used the back of his hand to push her down in the bathtub, causing her to fall down and hit her head. Salazar also claimed he had abandoned Adriana because he was scared.

A pathologist testified that Adriana’s cause of death was multiple blunt force trauma and that the manner of death was ruled a homicide. According to the pathologist, Adriana’s injuries were not consistent with Salazar’s version of the facts, but rather, indicated repeated blows of severe force to Adriana’s head, chest, and stomach. For instance, Adriana’s chest injury surpassed what the pathologist had seen previously in automobile accident injuries; her heart was so severely damaged that, had she lived, it would have ruptured; and she suffered such severe shaking injuries that would have been blind. The pathologist also testified that Adriana had bruising to her neck, that several of her ribs were broken, and that she suffered injuries consistent with some type of sexual penetration.

CRIMINAL HISTORY

During trial, the prosecution presented evidence that Salazar had committed a few minor thefts and had been involved in several assaults, including one on the mother of his two children. Soon after being placed in the Lubbock County Jail, Salazar threatened to kidnap someone and escape. He also threatened to commit suicide.

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

04/30/97 - A Lubbock County grand jury indicts Salazar for capital murder.

03/09/99 - Salazar is convicted of capital murder.

03/12/99 - The jury answered the special issues in a manner which results in Salazar being sentenced to death.

05/19/99 - The trial court denied Salazar’s motion for new trial.

10/13/00 - Salazar filed a state writ of habeas corpus application raising 6 claims.

01/17/01 - The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed Salazar’s conviction and sentence.

06/06/01 - The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals denied habeas relief.

10/01/01 - The U.S. Supreme Court denied certiorari review of the Texas court’s decision.

09/20/02 - Salazar petitioned a federal court for writ of habeas corpus relief raising 8 claims.

08/27/03 - The federal district court denied the writ and issues final judgment.

04/01/04 - Salazar applied to the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for a certificate of appealability.

11/30/04 - The 5th Circuit Court granted a COA on one claim, and orders additional briefing.

07/29/05 - The 5th Circuit Court affirmed the federal district court’s denial of habeas relief.

09/28/05 - Salazar’s petition for rehearing was denied by the 5th Circuit Court

10/28/05 - The trial court scheduled Salazar’s execution for Wednesday, March 22, 2006.

12/27/05 - Salazar petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court for certiorari review of the 5th Circuit’s opinion.

02/15/06 - Salazar filed a successive state writ application raising a claim that he is mentally retarded such that his execution is prohibited.

02/17/06 - Salazar amended his successive state writ application to raise a claim that he is entitled to an evidentiary hearing.

03/01/06 - Salazar petitioned for clemency with the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles.

03/06/06 - The U.S. Supreme Court denied certiorari review of the 5th Circuit Court’s affirmation of the district court’s denial of habeas relief.

03/09/06 - The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals dismissed Salazar’s successive habeas application.

03/10/06 - Salazar asked the Court of Criminal Appeals to reconsiders its decision.

03/17/06 - The 5th U.S. Circuit Court denied Salazar's motion for leave to file a successive federal habeas opinion.

03/20/06 - The Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles voted to deny Salazar's request for commutation and denied his request for a reprieve.

Pending – Salazar’s motion to the 5th Circuit Court for leave to file a successive federal habeas petition.

"Lubbock man executed for death of toddler." (Associated Press March 22, 2006, 6:39PM)

HUNTSVILLE — A Lubbock man was executed tonight for the April 1997 beating death of his girlfriend's 2-year-old daughter.

``To everybody on both sides of that wall, I want you to know that I love you both,'' Robert Salazar Jr., said in a final statement, acknowledging his family and Adriana Gomez's mother and other relatives who were there as witnesses. He looked toward his family during his remarks. ``I am sorry that the child had to lose her life, but I should not have to be here. Tell my family I love them all and I will see them in heaven. Come home when you can.''

Salazar was pronounced dead at 6:20 p.m., seven minutes after the lethal dose began to flow. Salazar, 27, was the sixth prisoner put to death this year in Texas and the second of four scheduled this month in the nation's busiest capital punishment state.

Salazar told police he just wanted Adriana, whom he was baby-sitting, to stop crying. So he pushed her with the back of his hand, causing her to fall down in a bathtub and hit her head. ``I did not mean to hurt Adriana,'' Salazar told police in a statement after his arrest for the girl's death in her Lubbock home. ``I don't want people to think I'm a bad person for what I did.'' But authorities said Salazar did more than push the toddler. In a violent rage, he inflicted injuries on Adriana that a pathologist who testified at his trial said were worse than those suffered by victims of auto accidents.

The Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles on Monday rejected requests to commute Salazar's sentence to life or halt the execution. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals and the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals turned down requests by Salazar's attorney, Michael Charlton, to stop the execution based on claims the inmate is mentally retarded. There were no appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Authorities said Salazar delivered at least three life-threatening injuries to the girl: a blow to the head that left it feeling like gelatin, a blow to her chest that left her heart on the verge of rupturing and a blow to her abdomen that pushed internal organs against her backbone. ``Salazar destroyed that little girl's body, just destroyed it,'' said Rusty Ladd, who helped prosecute the case for the Lubbock County District Attorney's Office.

Salazar began dating Adriana's mother, Raylene Blakeburn, in 1996. He took care of the toddler while her mother worked. Blakeburn told authorities Salazar had abused her daughter several other times. After beating her, Salazar left Adriana in the crib at her Lubbock home and went to his mother's house to drink beer with a friend. Adriana's mother found her when she got home from work and took her to a hospital, where she died a few hours later.

Salazar, 18 at the time of his crime, refused a request from The Associated Press for an interview in the weeks before his scheduled execution. Philip Wischkaemper, Salazar's defense attorney during his 1999 trial, said the inmate's mental retardation is behind his lack of remorse. He also said Salazar was severely abused and neglected as a child by his father. The mental retardation issue was not brought up during Salazar's trial. ``We know mentally retarded people have difficulty showing emotion,'' said Wischkaemper, who added tests have shown that Salazar's IQ is probably under 75. The threshold for mental retardation is 70.

In 2002, the Supreme Court barred executions of the mentally retarded, on grounds they violated the constitutional ban on cruel and unusual punishment. Wade Jackson, first assistant district attorney for Lubbock County, said other tests have shown that Salazar's IQ is as high as 102.

Wischkaemper said Salazar was condemned partly because jurors at his trial were misinformed by someone on the panel that he could have been released on parole in 20 to 25 years instead of the actual 40 if sentenced to life in prison.

Ladd, now a judge in Lubbock, said it was the brutal nature of the crime that ultimately determined the jury's decision. ``I've never shed tears over a victim the way I did over that little girl,'' Ladd said.

Next on the execution schedule is Raymond Martinez, condemned for the 1983 shooting death of a Houston bar owner during a robbery. He is set to be executed Tuesday.

"Robert Salazar Executed for 1997 Murder of Lubbock Toddler." (March 22, 2006)

After nine years, friends and family of 2-year-old Adriana Gomez say justice has finally been served. Just after 6pm on Wednesday, they watched the man who killed Adriana, die. Robert Salazar was executed in Huntsville Wednesday evening. He beat his girlfriend's daughter Adriana to death in their central Lubbock home in April of 1997. Court testimony claimed the severe injuries were comparable to those usually seen as a result severe car crash. Salazar filed a total of three appeals since his execution date was set last October. All were denied. NewsChannel 11's Cecelia Coy was in Huntsville to witness Salazar's execution and has this report.

According to state documents, Robert Salazar had continued to deny beating to death 2-year-old Adriana Gomez. We spoke to a friend of the family Erlinda Castro who witnessed the execution. She came here to hear Salazar finally confess to killing the toddler. "I just want to know why. How could he do this? Why won't he admit it. Even before he dies, I'd like to know why and would he admit to what he did," said Erlinda.

But that didn't happen. Salazar's last words were quote "everybody on both sides, I love you both. I'm sorry that child had to lose her life but I should not be here. I want to tell my family, I love them. I'll see you in heaven. I'm done. Again, I love you all."

You could hear crying in the other word from inmate side of the witness area, but Cecelia says she did not see any emotions from the witness side. She watched Salazar take a few heavy breaths. He closed his eyes and that was it. Salazar was put to death by lethal injection. A doctor announced him dead by 6:20pm Wednesday evening. A total of six people watched Salazar die, including Raylean Torres, Adriana's mother, who now lives in Minnesota.

A Texas Department of Criminal Justice spokesperson told us Salazar's mother is handling the burial. Salazar has been on death row since April of 1999.

Salazar's last meal included a dozen tamales, six brownies, refried beans with chorizo, two rollo candies, six hard shell tacos with lettuce, three big red sodas, ketchup, hot sauce, six jalapeno peppers, tomatoes, cheese, and extra ground beef.

Lubbock Man Executed For Murder of 2-Year-Old Child

The State of Texas has executed Robert Salazar. The Lubbock man received the death penalty for the April 1997 murder of his girlfriend's daughter, 2-year-old Adriana Gomez. Her mother found her in their Central Lubbock home with blood in her mouth and her head caved in. Salazar was supposed to be taking care of her at the time. Instead, prosecutors said he beat the little girl, then left her to die while he went out for a beer.

Adriana's mother has one family friend still living in Lubbock. She went to Huntstville to witness Salazar's execution. A paramedic testified 2-year-old Adriana Gomez was beaten so badly, the back of her head felt like jello. Her arm was broken and she had a bruised heart. District Attorney Matt Powell says the injuries were what you would see in a car crash. Erlinda Castro said she wants to hear Salazar's last words. She says, "Why won't he admit it? Even before he dies, I'd like to know why and would he admit to what he did."

Adriana and her mother Raylene were once two complete strangers to Erlinda. But because of circumstances in Raylene's life, Erlinda took the 17-year-old mother and toddler into her home. They lived with her for more than one year. During that time, Erlinda grew close to both girls. But when Raylene met Robert, she moved out of Erlinda's home. Erlinda says at that point, she started to see signs of abuse like bruises on the child's body. Erlinda said, "We tried telling the mother and nothing came of it. CPS went over but nothing was done about it."

Erlinda also noticed Adriana was scared of Robert. Erlinda says, "She would tell me, I don't want to see Robert. Please, I don't want to see Robert." Erlinda says she had no control of the situation at that point.

Nine years after the death of this little girl, Erlinda still thinks about Adriana. She says,"It's not that I forgot about her. I just don't always like to sit and look and think because it hurts for me to have to know that she dies. She was going to be very bright and very pretty. She didn't get a chance to do nothing or the things she should have been able to do." Erlinda hopes Adriana's soul can rest now that her killer is being put to death for what he did.. Erlinda says, "I know he's not going to suffer like she did."

A lethal injection consists of three doses. The first is a narcotic that causes the inmate fall into a coma. The second is a muscle relaxant that causes the collapse of the diaphragm and lungs. Finally a dose of potassium chloride is administered to stop the heart. The whole process takes about seven minutes.

"Man executed for killing crying toddler." (March 22, 2006)

HUNTSVILLE, Texas (AP) -- A man who beat his girlfriend's 2-year-old daughter to death because she was crying was executed Wednesday night. "I am sorry that the child had to lose her life, but I should not have to be here," Robert Salazar Jr., said in a final statement. "Tell my family I love them all and I will see them in heaven." Salazar, 27, was pronounced dead at 6:20 p.m., seven minutes after the lethal dose began to flow.

Adriana Gomez was killed in 1997. Salazar, of Lubbock, told police he pushed the girl with the back of his hand, causing her to fall down in a bathtub and hit her head. A pathologist, however, testified that Salazar, in a violent rage, inflicted injuries on Adriana that were worse than those suffered by victims of auto accidents. "I've never shed tears over a victim the way I did over that little girl," said Rusty Ladd, who helped prosecute the case for the Lubbock County District Attorney's Office.

The Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles on Monday rejected requests to commute Salazar's sentence to life or halt the execution. A state court and a federal appeals court turned down requests by Salazar's attorney to stop the execution based on claims the inmate was mentally retarded. There were no appeals to the Supreme Court.

Salazar was the sixth prisoner put to death this year in Texas and the second of four scheduled to die this month in the nation's busiest capital punishment state.

"Lubbock man set to be executed for brutal beating death of toddler." (AP March 22, 2006)

HOUSTON (AP) - Even though her mother found her alive, 2-year-old Adriana Gomez never could have survived the injuries suffered at the hand of her baby sitter. Robert Salazar Jr., who was also the boyfriend of the girl's mother, delivered at least three life-threatening injuries on April 23, 1997, because the girl wouldn't stop crying: a blow to the head that left it feeling like gelatin, a blow to her chest that left her heart on the verge of rupturing and a blow to her abdomen that pushed internal organs against her backbone.

Salazar left Adriana in the crib at her Lubbock home after the beating and went to his mother's house to drink beer with a friend. Adriana's mother found her and took her to a hospital, where she died a few hours later. Salazar told police he accidentally injured Adriana after pushing her in the bathroom. Salazar, 27, was convicted of capital murder and set to be executed by lethal injection tonight in Huntsville. He would be the sixth prisoner put to death this year in Texas and the second of four scheduled this month in the nation's busiest capital punishment state.

Salazar began dating Adriana's mother, Raylene Blakeburn, in 1996. He took care of the toddler while her mother worked. Blakeburn told authorities Salazar had abused her daughter several other times, including dislocating her shoulder less than four months before the child's death. "There is an expectation that grown-ups are going to take care of little kids, not destroy them," said Rusty Ladd, who helped prosecute the case for the Lubbock County Criminal District Attorney's Office.

The Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles on Monday rejected requests to commute Salazar's sentence to life or halt the execution. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals and the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals have turned down requests by Salazar's attorney, Michael Charlton, to stop the execution based on claims the inmate is mentally retarded. Charlton said he didn't plan to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Salazar, 18 at the time of his crime, refused a request from The Associated Press for an interview in the weeks before his scheduled execution. In a statement to police after his arrest, Salazar said he became angry with Adriana when she wouldn't stop crying while they took a shower. Salazar pushed the toddler, causing her to hit her head in the bathtub. "I did not mean to hurt Adriana," Salazar said. "I don't want people to think I'm a bad person for what I did."

Philip Wischkaemper, Salazar's defense attorney during his 1999 trial, said the inmate's mental retardation is behind his lack of remorse. He also said Salazar had been severely abused and neglected as a child by his father. "We know mentally retarded people have difficulty showing emotion," said Wischkaemper, who added that tests have shown that Salazar's IQ is probably under 75. The threshold for mental retardation is 70.

In 2002, the Supreme Court barred executions of the mentally retarded, on grounds they violated the constitutional ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

Wade Jackson, first assistant district attorney for Lubbock County, disputed Wischkaemper's claims, saying other tests have shown that Salazar's IQ is as high as 102.

Wischkaemper said Salazar was condemned partly because jurors at his trial were misinformed by someone on the panel that he could have been released on parole in 20 to 25 years instead of the actual 40 if sentenced to life in prison.

Ladd said it was the brutal nature of the crime that ultimately determined the jury's decision. "As a little child you are utterly dependent on the people that are your caretakers, and he was supposed to take care of her," Ladd said.

Next on the execution schedule is Raymond Martinez, condemned for the 1983 shooting death of a Houston bar owner during a robbery. He is set to be executed March 28.

A Lubbock County jury sentenced Richard Salazar to death in March 1999 for murdering two-year-old Adriana Gomez. On the night of April 23, 1997, Raylene Blakeburn left her two-year-old daughter Adriana with her boyfriend Robert Salazar, while she went to work. When she returned home from work, she found Adriana in bed and unconscious, breathing abnormally with blood in her mouth. Salazar was not there because he and a friend had gone to buy beer. Returning from the store, Salazar and his friend saw an ambulance at his girlfriend’s house. They did not stop, but continued on to Salazar’s mother’s house to drink the beer they had purchased.

When paramedics arrived at the scene, they noted that the back of Adriana’s head was caved in. There were also marks and bruises all over Adriana’s body. Suspecting child abuse, the paramedics contacted the police. Adriana died later that evening. Not long after discovering Adriana, Blakeburn called Salazar at his mother’s house, and he told her not to tell the police that he had been watching Adriana.

Salazar later gave a written statement to the police. He admitted that he had been with Adriana while his girlfriend was at work. He claimed that while giving Adriana a shower, he became angry with her because she would not stop crying and he had used the back of his hand to push her down in the bathtub, causing her to fall down and hit her head. Salazar also claimed he had abandoned Adriana because he was scared.

A pathologist testified that Adriana’s cause of death was multiple blunt force trauma and that the manner of death was ruled a homicide. According to the pathologist, Adriana’s injuries were not consistent with Salazar’s version of the facts, but rather, indicated repeated blows of severe force to Adriana’s head, chest, and stomach. For instance, Adriana’s chest injury surpassed what the pathologist had seen previously in automobile accident injuries; her heart was so severely damaged that, had she lived, it would have ruptured; and she suffered such severe shaking injuries that she would have been blind. The pathologist also testified that Adriana had bruising to her neck, that several of her ribs were broken, and that she suffered injuries consistent with some type of sexual penetration.

Texas Execution Information Center by David Carson.

Robert Madrid Salazar Jr., 27, was executed by lethal injection on 22 March 2006 in Huntsville, Texas for the murder of a 2-year-old girl.

On 23 April 1997, Raylene Blakeburn of Lubbock went to work, leaving her boyfriend, Robert Salazar, then 18, to babysit her 2-year-old daughter, Adrana Gomez. While her mother was gone, Adriana began crying, and Salazar could not maker her stop. Salazar beat the child repeatedly on the head, chest, and stomach. After Adriana lost consciousness, Salazar put her in her crib, then he and a friend went out to get beer.

Blakeburn returned home from work at about 5:00 p.m. and found her daughter unconscious, breathing abnormally, and bleeding from her mouth. She called paramedics. When the paramedics saw the extent of the child's injuries - bruises, twisted limbs, and a head that felt "like Jello" - they called the police. Adriana died in a hospital at about 7:45 that evening.

In a written statement to police, Salazar said that he was taking a shower with Adriana when she started crying and would not stop. (He said that he had babysat for Adriana before, and was aware that she did not like showering with him.) He stated that he became angry with her, and pushed her with the back of his hand, causing her to fall down and hit her head on the bathtub. He said that he abandoned her afterward because he was scared. "I did not mean to hurt Adriana," he stated. "I don't want people to think I'm a bad person for what I did."

At Salazar's trial, Roger Torres testified that at about 4:00 p.m., he was walking home from work when Salazar drove up to talk to him. Torres testified that Adriana was not with him. Salazar asked Torres to look at his fan belt. After looking at the car, the men drove to a nearby store to buy beer. Torres testified that he noticed that Salazar's shirt had a number of small stains, which appeared to be blood. When they returned from the store, they drove by Blakeburn's house and, seeing the ambulance, did not stop, but proceeded to Salazar's mother's house. Once at his mother's house, Salazar changed his shirt, and he and Torres drank beer. Salazar then received a phone call from Blakeburn. Torres testified that Salazar told Blakeburn not to tell the police that he had been watching Adriana. He also told Torres that the matter was none of his business and to be quiet about it.

A pathologist testified that Adriana suffered from multiple blunt force trauma wounds that were inconsistent with being pushed or falling in the bathtub. In addition to the back of her head being caved in, he testified that her chest injuries were worse than he had seen in any auto accident victim, that her eyes were injured from being struck or shaken - enough to blind her, had she lived - and that she had also been hit in the face. She also had bruises on her neck. The pathologist also testified that Adriana had vaginal injuries that were consistent with sexual penetration.

The prosecution also presented evidence that in January 1997, Adriana suffered either a broken collar bone or dislocated shoulder. When asked about the injury by a neighbor, Adriana replied that Salazar had done it. An analysis of a blood stain found on the pants Salazar was wearing that day showed that it contained Adriana's DNA.

A jury convicted Salazar of capital murder in March 1999 and sentenced him to death. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the conviction and sentence in January 2001. All of his subsequent appeals in state and federal court were denied.

Salazar refused requests for interviews with the media while on death row. His family and the victim's mother's family witnessed the execution, watching from separate observation rooms. "To everybody on both sides of that wall, I want you to know that I love you both," Salazar said in his last statement. "I am sorry that the child had to lose her life, but I should not have to be here." Salazar expressed love to his family again, and then the lethal injection was started. He was pronounced dead at 6:20 p.m.

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

Robert Salazar Jr., TX - March 22

Do Not Execute Robert Salazar Jr.!

Robert Salazar Jr., a Hispanic man, awaits execution for the murder of two-year-old Adriana Blakeburn in Lubbock County, Texas. Salazar began dating Raylene Blakeburn, Adrian’s mother, in the fall of 1996. On the morning of April 23, 1997 Blakeburn went to work and left her daughter, as she often did, in Salazar’s care. When she returned home at 5:00 she found Adriana in her bed unconscious and struggling for breath with Salazar nowhere to be found. Adriana died in a hospital roughly three hours later.

In a written statement to the police, Salazar said that he had become angry with Adriana when she would not stop crying while the two were showering together. In an attempt to get her to stop crying Salazar pushed Adriana with his back of his hand which caused her to fall down in the bathtub and hit her head. Salazar, frightened because Adriana was unconscious and bleeding, deserted the child and left the house. In contrast to Salazar’s statement to the police, the pathologist who performed the autopsy testified that Adriana’s death was a result of trauma from multiple blunt force injuries and therefore inconsistent with Salazar’s version of the events.

Salazar was sentenced to death despite evidence that he had been abused and neglected as a child. Moreover, it is alleged by Salazar that the jury who sentenced Salazar to death did so under the assumption that if sentenced to life in prison he would be eligible for parole in twenty years, when in reality, as provided by Texas state law, someone who is sentenced to life in prison is not eligible for parole “…until the actual calendar time the inmate has served, without consideration of good conduct time, equals 40 years.” Following the sentencing phase of his trial it was discovered—through a television reporter’s interviews with several jurors—that during jury deliberations one of the jurors, professing to know the law of parole, claimed as fact that Salazar would be out in 20 to 25 years. As a result, several jurors who were purportedly leaning towards sentencing Salazar to life in prison decided to sentence Salazar to death instead. Salazar maintains that the discussion by the jury of his possible parole denied him a fair trial and has appealed his sentence based on this issue on both the state and federal level, but has been denied a retrial or habeas corpus relief on each occasion.

Salazar’s case illustrates the need to provide juries with the option of life without parole as an alternative to a death sentence, as well as what has been termed “truth in sentencing.” As of Sept. 1, 2005 the option of life without parole was available to Texas jurors in the sentencing phase of capital trials. But because Salazar was sentenced in 1999, the jury that sentenced to Salazar to death was not given this choice. The jury that sentenced Salazar to death did so believing that if they didn’t Salazar would not serve the time they felt he deserved. Furthermore, if the jury had been informed by the court how long it would be before Salazar was eligible for parole ahead of time it is likely that Salazar would not have received the same sentence. In other words, due to the fact that juries often decide in favor of a death sentence because they assume that the time served for a non-death sentence will be too short, juries should be made aware before they make their decision how long a defendant will actually remain in prison.

Salazar’s execution is one of five scheduled by the State of Texas for the month of March.

Please write Gov. Rick Perry requesting that he stop the execution of Robert Salazar Jr.!

ALIVE - Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty (Voices From Inside)

Robert Salazar jr.

Hi, my name is Robert Salazar Jr.

I am a Mexican American on Texas Death Row. I have been here since 1999, but I was arrested in 1997. Being without friends or family for over 7 years is harsh. This is why I have this page. I wish to make friends with who ever is willing to give a chance.

I’m not adverse to accepting help legally or otherwise if that’s what you want. You can be of any nationality, sex or size. Your age or anything like that does not matter to me.

I am 26 years old and my birthday is October 29. 1978. I like to read, listen to sports, listen to all kinds of music, and play dungeons and dragons. The only languages that I can read, write and speak are English and Spanish. So if you want to lend a hand or just be friend, please do contact me. You’ll be greatly appreciated. By for now and thank you!

Robert Salazar jr.

# 999303

Polunsky Unit

3872 F.M. 350 South

Livingston, TX 77351 USA

Salazar v. State, 38 S.W.3d 141 (Tex.Crim.App. 2001) (Direct Appeal).

Defendant was convicted, following jury trial in a 72nd District Court, Lubbock County, J. Blair Cherry, J., of capital murder in connection with death of girlfriend's two-year-old daughter and was sentenced to death. On automatic direct appeal, the Court of Criminal Appeals, Meyers, J., held that: (1) evidence was legally sufficient to support jury's affirmative answer at penalty phase to special issue of "future dangerousness"; (2) denial of new trial motion that was predicated on allegations of juror misconduct during penalty deliberations was not abuse of discretion; (3) denial of motion for change of venue was not abuse of discretion; (4) probative value of photographs of internal organs removed from victim's body during autopsy was not substantially outweighed by danger of unfair prejudice; (5) evidence that victim, three months prior to charged murder, responded that "(defendant) did it" when neighbor asked who had caused injury to victim's shoulder was admissible under excited utterance exception to hearsay rule. Affirmed. Price, J., concurred in points of error 6-9 and otherwise joined opinion of the court. Womack, J., concurred in point of error 2 and otherwise joined opinion of the court.

MEYERS, J., delivered the opinion of the Court in which KELLER, P.J., HOLLAND, JOHNSON, KEASLER, HERVEY and HOLCOMB, JJ., join.

Appellant was convicted in March 1999 of a capital murder committed in April 1997. Tex.Penal Code Ann. § 19.03(a)(8). Pursuant to the jury's answers to the special issues set forth in Texas Code of Criminal Procedure Articles 37.071 §§ 2(b) and 2(e), the trial judge sentenced appellant to death. tex.Code Crim.Proc. Art. 37.071 § 2(g). Direct appeal to this Court is automatic. tex.Code Crim.Proc. Art. 37.071 § 2(h). Appellant raises fourteen points of error.

In point of error one, appellant claims the evidence is legally insufficient to support the jury's affirmative answer to the "future dangerousness" special issue. We review the evidence in the light most favorable to the jury's verdict to determine whether any rational trier of fact could have concluded beyond a reasonable doubt that "there is a probability that [appellant] would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society." Art. 37.071 § 2(b)(1). See Jackson v. Virginia, 443 U.S. 307, 319, 99 S.Ct. 2781, 61 L.Ed.2d 560 (1979); Barnes v. State, 876 S.W.2d 316, 322 (Tex.Crim.App.), cert. denied, 513 U.S. 861, 115 S.Ct. 174, 130 L.Ed.2d 110 (1994).

Appellant was charged with intentionally or knowingly causing the death of the two-year-old victim, who was the daughter of appellant's girlfriend. Viewed in a light most favorable to the verdict, the evidence shows that on April 23, 1997, appellant's girlfriend left the victim in appellant's care while she went to work. When appellant's girlfriend came home from work, she found the victim in bed and unconscious, breathing abnormally with blood in her mouth. Appellant was not there because he and a friend had gone to buy beer. Returning from the store, appellant and his friend saw an ambulance at his girlfriend's house. They did not stop, but continued on to appellant's mother's house to drink the beer they had purchased.

When paramedics arrived at the scene, they noted that the back of the victim's head was caved in and felt like "Jello." There were also marks and bruises all over the victim's body. Suspecting child abuse, the paramedics contacted the police. The victim died later that evening. Not long after discovering the victim, the victim's mother called appellant at his mother's house, and appellant told her not to tell the police that he had been watching the victim. Appellant later gave a written statement to the police. He admitted that he had been with the victim while his girlfriend was at work. He claimed that while giving the victim a shower he became angry with her because she would not stop crying and he had used the back of his hand to push her down in the bathtub, causing her to fall down and hit her head. Appellant also claimed he had abandoned the victim because he was scared.

The victim's autopsy revealed at least three life-threatening injuries and numerous non-life-threatening injuries. All of these injuries were "acute," meaning they had been inflicted within 48 hours of the victim's death. The pathologist testified that the victim's cause of death was multiple blunt force trauma and that the manner of death was ruled a homicide. The pathologist also testified that the injuries sustained by the victim were not consistent with appellant's version of the facts, but rather, indicated repeated blows of severe force.

According to the pathologist, the victim's life-threatening injuries were caused by hard blows to the victim's head, chest, and stomach. These injuries were "all high energy, high impact injuries." The blow to the head, consistent with having been slammed into something hard, fractured the victim's skull. A "major blow to the chest" bruised the victim's lungs, diaphragm and heart. The chest injury surpassed what the pathologist had seen previously in automobile accident injuries. The heart was so severely damaged that had the victim lived, it would have ruptured, which would have been "incompatible with continued life." The blow to the stomach pushed the victim's abdomen against her backbone, crushing the tissues in between.

Injury to the victim's tongue and mouth was indicative of a blow to the mouth. The victim also suffered such severe shaking injuries that, had she lived, she would have been blind. There was bruising to the victim's neck and some of her ribs had been broken. Finally, injury to the victim's vagina was consistent with some type of sexual penetration. During punishment, the prosecution presented evidence that appellant had committed a few minor thefts and had been involved in several assaultive offenses, including an assault on the mother of his two children. Soon after being placed in the county jail, appellant threatened to kidnap someone and escape. Appellant also threatened to commit suicide.

Appellant presented evidence that, if sentenced to life in prison, he would probably be placed in administrative segregation, which has a low incident rate because the inmates are closely monitored. He argued these circumstances lowered the risk that he would present a future danger. The prosecution presented rebuttal evidence that, although only 10-15% of the prison population is in administrative segregation, almost 40% of felony offenses committed within the prison are committed in administrative segregation. One of appellant's punishment witnesses also testified on cross-examination that, "left without any intervention" in the free world, appellant would commit criminal acts of violence in the future. This was based in part on appellant's lack of remorse for his actions as well as his tendency to minimize his involvement in the offense.

Appellant contends that based upon a consideration of all the evidence, particularly evidence that he presented showing he was abused and neglected as a child, no rational juror could have affirmatively answered the "future dangerousness" special issue. A juror may give any weight or no weight to a particular piece of evidence in determining the special issues. Soria v. State, 933 S.W.2d 46, 65 (Tex.Crim.App.1996). The evidence viewed in a light favorable to the jury's determination was sufficient to support an affirmative answer to the "future dangerousness" issue.

The circumstances of this offense were particularly heinous. See Barnes, 876 S.W.2d at 322-23 (facts of offense can be sufficient to support "yes" answer to "future dangerousness" special issue). Appellant inflicted numerous life-threatening injuries on the two-year-old victim and then left her alone while he went to buy beer. Appellant beat the victim so badly that the back of her head felt like "Jello," and he so severely shook her that she would have been blind had she survived. Appellant had a history of committing assaultive offenses, and one of appellant's own witnesses admitted that he is dangerous to free society. In addition, testimony from the State's witnesses indicated that appellant could still be a future danger even if placed in administrative segregation. See Collier v. State, 959 S.W.2d 621, 623 (Tex.Crim.App.1997), cert. denied, 525 U.S. 929, 119 S.Ct. 335, 142 L.Ed.2d 276 (1998) (jury considers free and prison society in determining whether defendant is dangerous).

On this record, we cannot say the jury's affirmative answer to the "future dangerousness" special issue is irrational. Point of error one is overruled.

In point of error two, appellant argues the evidence is insufficient to support the jury's negative answer to the mitigating evidence special issue. See tex.Code Crim.Proc. Art. 37.071, § 2(e)(1). Appellant claims that the mitigating evidence he presented "was such as to require the imposition of a life sentence rather than a death sentence" and that the only way to afford him "meaningful appellate review" is for this Court to review the sufficiency of the evidence to support the jury's negative answer to the mitigating evidence special issue.

We do not review the sufficiency of the evidence to support a jury's negative answer to the mitigating evidence special issue, and we have rejected the claim that this deprives a defendant of "meaningful appellate review." See McGinn v. State, 961 S.W.2d 161, 166 (Tex.Crim.App.1998), cert. denied, 528 U.S. 1163, 120 S.Ct. 1179, 145 L.Ed.2d 1086 (2000) (this Court does not conduct a sufficiency review of the mitigation special issue); Green v. State, 934 S.W.2d 92, 106-07 (Tex.Crim.App.1996), cert. denied, 520 U.S. 1200, 117 S.Ct. 1561, 137 L.Ed.2d 707 (1997) (sufficiency review of mitigating evidence not required under Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments); McFarland v. State, 928 S.W.2d 482, 498-99 (Tex.Crim.App.1996), cert. denied, 519 U.S. 1119, 117 S.Ct. 966, 136 L.Ed.2d 851 (1997) (constitutionality of Article 37.071 not contingent upon appellate review of mitigation issue). Point of error two is overruled.

* * *

The judgment of the trial court is affirmed. PRICE, J., concurs in points of error 6-9 and otherwise joins. WOMACK, J., concurs in point of error 2 and otherwise joins.

Salazar v. Dretke, 419 F.3d 384 (5th Cir. Tex. 2005) (Habeas)

Background: Defendant was convicted, following jury trial in a 72nd District Court, Lubbock County, J. Blair Cherry, J., of capital murder in connection with death of girlfriend's two-year-old daughter and was sentenced to death. On automatic direct appeal, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, Meyers, J., 38 S.W.3d 141, affirmed. Following denial of his state court petition for federal habeas relief, defendant filed federal habeas petition, which was denied by order of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas, Sam R. Cummings, J., and he appealed.

Holdings: The Court of Appeals, King, Chief Judge, held that:

(1) defendant's due process claims were adjudicated on merits by state habeas court; and

(2) state habeas court's decision, in rejecting federal due process claim which was grounded in allegedly erroneous speculation by jurors as to parole consequences of not imposing capital sentence and sentencing murder defendant to life in prison, that state evidentiary rule barred prisoner from introducing evidence of jury deliberations necessary to support his due process claim, and that rule did not itself violate prisoner's due process rights, was not contrary to, or an unreasonable application of, clearly established federal law.

Affirmed.

KING, Chief Judge:

Petitioner-Appellant Robert Madrid Salazar appeals the district court's dismissal of his 28 U.S.C. § 2254 habeas corpus application. For the following reasons, we AFFIRM the judgment of the district court.

I. FACTUAL AND PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND - A. The Trial: Conviction and Sentencing

On April 30, 1997, Salazar was indicted for the capital murder of his girlfriend's two-year-old daughter. He pleaded not guilty, and on January 11, 1999, his trial began. The evidence adduced at trial showed that Salazar began dating a woman named Raylene Blakeburn in the fall of 1996. On April 23, 1997, Blakeburn went to work in the morning, leaving her two-year-old daughter Adriana in Salazar's care as she often did. When Blakeburn came home from work at around 5:00 p.m., Salazar was not there. Blakeburn discovered Adriana in her bed, unconscious, breathing abnormally, and with blood in her mouth. With the assistance of a neighbor, Blakeburn called for an ambulance. When the paramedics arrived, they found Blakeburn standing outside of her house holding Adriana in a blanket. The paramedics were unable to bring Adriana back to consciousness, and they therefore placed her on a ventilator. One paramedic noticed that the back of Adriana's head had been caved in and that it felt like “Jello.” The paramedics also observed that one of Adriana's arms was twisted and deformed and that she had marks and bruises covering her neck, ankles, and chest. Suspecting child abuse, the paramedics contacted the police. Adriana died at roughly 7:45 p.m.

Roger Torres, one of Salazar's friends, testified that at around 4:00 p.m. that day, he was walking home when Salazar drove up to him and asked if he could take a look at Salazar's fan belt. According to Torres, Adriana was not with Salazar at the time. Shortly thereafter, Torres examined the fan belt, and a little after 5:00 p.m., the two men drove to a nearby store and purchased some beer. At around this time, Torres noticed that Salazar's shirt had on it a number of small stains, which appeared to be blood. When the two men returned from the store, they saw the ambulance outside of Blakeburn's residence. However, they did not stop, but rather drove by and continued on to Salazar's mother's house. Once at his mother's house, Salazar changed his shirt and the two men drank some of the beer. At this time, Blakeburn called Salazar at his mother's house and told him that Adriana was injured. Salazar told Blakeburn not to tell the police that he had been watching Adriana that day. He also told Torres to be quiet and that the matter was none of his business.

Salazar later gave a written statement to the police, in which he admitted that he had been watching Adriana while her mother was at work on the day in question. He stated that he and Adriana were taking a shower together and that he became angry because she would not stop crying.FN1 Salazar also stated that in order to stop her crying, he pushed her with the back of his hand, causing her to fall down in the bathtub and hit her head. Salazar stated that he became scared because Adriana was unconscious and bleeding, so he abandoned the child and left the scene. FN1. Salazar stated that Adriana generally did not like to take a shower with him when her mother was not there.

The pathologist who performed the autopsy testified that Adriana's death was caused by trauma from multiple blunt force injuries, and he ruled the manner of death a homicide. The pathologist stated that the injuries sustained by Adriana were inconsistent with Salazar's contention that she had fallen down and hit her head in the tub. Instead, Adriana's injuries indicated the infliction of repeated blows of severe force to her head, chest, and abdomen. The autopsy revealed that the two-year-old had suffered at least three life-threatening injuries. All of these injuries were “acute,” meaning they had been inflicted within forty-eight hours prior to the victim's death. One blow to her head resulted in a posterior basal skull fracture, consistent with her skull having been slammed into a hard surface. The location of several other smaller skull fractures was consistent with her being struck multiple times, and the injuries to her eyes were consistent with being shaken or struck so hard that she would have been blind had she survived. A major blow to the chest bruised Adriana's lungs, diaphragm, and heart. The pathologist testified that the injuries to the child's chest surpassed anything he had seen previously in cases of automobile accidents. More than one of Adriana's ribs had been broken, and her heart was so severely damaged that it would have ruptured had she lived much longer. The blow to her stomach had pushed her abdomen against her backbone, crushing the tissues in between. The injuries to her tongue and mouth were indicative of a blow to her face, and the injury to her vagina was consistent with sexual penetration.

The prosecution also presented evidence at trial that in January 1997, Adriana suffered either a broken collar bone or a dislocated shoulder. When asked about the injury by a neighbor, Adriana replied that Salazar had done it. Lab analysis of a blood stain on the pants that Salazar was wearing on the day in question revealed that the stain was consistent with Adriana's DNA. On March 9, 1999, the jury found Salazar guilty of capital murder.

At sentencing, the State and Salazar each presented evidence with respect to the special issues submitted to the jury pursuant to Tex.Code Crim. Proc. Ann. art. 37.071 (i.e., future dangerousness and mitigating circumstances). In an attempt to show mitigating circumstances, Salazar presented evidence that he had been badly abused and neglected as a child. The State countered with evidence that Child Protective Services had intervened on his behalf. Moreover, the prosecution argued in closing that Salazar's childhood did not provide sufficient mitigating circumstances in light of, inter alia: (1) the heinous and brutal nature of the crime, including the likelihood that sexual assault had occurred; (2) the vulnerability of the victim due to her age and his position of trust in relation to her; (3) his attempt to cover up the crime and his continuing lack of remorse; and (4) evidence that he had a history of violence against the child.

In an effort to show a low probability of future dangerousness, Salazar presented expert testimony of a clinical psychologist familiar with the Texas Department of Criminal Justice Institutional Division. The expert opined that if Salazar were sentenced to life in prison, he would be a candidate for administrative segregation, wherein he would pose a lesser danger to other inmates due to the increased level of supervision. However, the expert conceded that he could predict with near certainty that Salazar would commit additional violent offenses in the future if he were not imprisoned. The State also presented rebuttal evidence that although only 10-15% of the prison population is in administrative segregation, roughly 40% of the felony offenses committed in the prison occur in administrative segregation. In addition, the State presented evidence that Salazar had committed at least one minor theft and that he had been involved in a number of violent assault offenses, including an incident in which he choked the mother of his two children (a woman other than Blakeburn).

Salazar requested the trial court to instruct the jury that he would be eligible for parole after forty years if he received life in prison rather than death. At the time of Salazar's trial, Texas law provided that a criminal convict who is sentenced to life in prison will not be eligible for parole until he has served forty years. Tex. Gov't Code Ann. § 508.145(b) (Vernon 2003) (“An inmate serving a life sentence for a capital felony is not eligible for release on parole until the actual calendar time the inmate has served, without consideration of good conduct time, equals 40 calendar years.”). However, the trial court declined to give the instruction.FN2 After the close of evidence and argument, the jury deliberated and answered the two special issues in favor of the death penalty (i.e., that Salazar presented a continuing threat to society and that there were insufficient mitigating circumstances to warrant life in prison rather than death). Consequently, the trial court sentenced Salazar to death.

FN2. Thus, the trial court did not specifically instruct the jury not to consider the possibility of parole in its deliberations. However, at the beginning of trial, the trial court did instruct the jury that “[a]ll evidence must be presented in open Court, so that each side may question the witness and make proper objections” and that “[t]his prevents a trial based upon secret evidence.” Similarly, the jury charge instructed the jurors “not to refer to or discuss any matter or issue not in evidence before [them].”

B. Motion for New Trial

After sentencing, television reporters interviewed at least one of the jurors, who revealed that during deliberations the jury discussed the possibility of parole if Salazar were sentenced to life in prison rather than death. In light of this discovery, Salazar filed a motion for a new trial, arguing, inter alia, that he had been denied a fair and impartial trial because one of the jurors, who professed to know the law of parole, asserted as fact a misstatement about parole law, and that misstatement was relied upon by one of the other jurors, who for that reason changed her vote to a harsher sentence.FN3 In a separately numbered paragraph, Salazar's motion advanced a similar claim, without citing any authority, that he was deprived of a fair and impartial trial because the jury “improperly discussed the effect the Parole Laws would have on the release of Defendant if assessed a life sentence by the jury.”

On May 19, 1999, the state trial court conducted a hearing on Salazar's motion for a new trial. At the hearing, Salazar sought to present live testimony from four of the jurors at Salazar's trial. Before this evidence was introduced, however, the State informed the trial court that if any of the jurors were to testify as to discussions that occurred during the deliberations, it would object under Tex.R. Evid. 606(b).FN4 Defense counsel requested that he be allowed to present the evidence under a bill of exception in the event that the court sustained the State's objection. The trial court sustained the prosecution's objection, concluding that Rule 606(b) rendered inadmissible the jurors' testimony as to their statements and discussions during deliberations and as to the effect of those discussions on their thought processes and decisions.FN5 However, as defense counsel requested, the court allowed the jurors' testimony to be presented under a bill of exception.FN6 As discussed in detail by the Texas Criminal Court of Appeals (the “TCCA”), these jurors presented conflicting accounts as to what occurred during deliberations regarding their discussion of parole law.

* * *

[L]et it once be established that verdicts solemnly made and publicly returned into court can be attacked and set aside on the testimony of those who took part in their publication and all verdicts could be, and many would be, followed by an inquiry in the hope of discovering something which might invalidate the finding. Jurors would be harassed and beset by the defeated party in an effort to secure from them evidence of facts which might establish misconduct sufficient to set aside a verdict. If evidence thus secured could be thus used, the result would be to make what was intended to be a private deliberation, the constant subject of public investigation; to the destruction of all frankness and freedom of discussion and conference. Id.

In Tanner, the Supreme Court concluded that Fed.R.Evid. 606(b) rendered inadmissible jurors' testimony that other jurors had consumed alcohol and illegal drugs during the trial, and it noted that the rule “is grounded in the common-law rule against the admission of jury testimony to impeach a verdict and the exception for juror testimony relating to extraneous influences.” 483 U.S. at 121-26, 107 S.Ct. 2739. The Tanner Court reaffirmed the legal principle from McDonald in defense of the exclusion of the juror testimony:

There is little doubt that postverdict investigation into juror misconduct would in some instances lead to the invalidation of verdicts reached after irresponsible or improper juror behavior. It is not at all clear, however, that the jury system could survive such efforts to perfect it. Allegations of juror misconduct, incompetency, or inattentiveness, raised for the first time days, weeks, or months after the verdict, seriously disrupt the finality of the process. Moreover, full and frank discussion in the jury room, jurors' willingness to return an unpopular verdict, and the community's trust in a system that relies on the decisions of laypeople would all be undermined by a barrage of postverdict scrutiny of juror conduct. Id. at 120, 107 S.Ct. 2739 (internal citation omitted).

The Court concluded that the exclusion of the juror testimony did not violate the defendant's right to a fair and impartial trial in light of the “long-recognized and very substantial concerns support[ing] the protection of jury deliberations from intrusive inquiry.” Id. at 127, 107 S.Ct. 2739. Moreover, the Court reasoned that defendants' rights are sufficiently protected by a number of other safeguards in the trial process, including examination of the jurors during voir dire, the ability of jurors to report misconduct prior to rendering a verdict, and the evidence other than juror testimony. Id. at 127, 107 S.Ct. 2739. Thus, the Court held that the application of Fed.R.Evid. 606(b) to bar the jurors' testimony did not violate constitutional principles.

At oral argument in the present case, defense counsel contended that Tanner is not dispositive of Salazar's due process claim because Tanner relied upon the distinction between juror testimony of objective jury misconduct and testimony concerning the subjective thought processes of the jurors. Counsel stated that testimony relating to objective jury misconduct is always admissible under federal law to impeach a verdict, whereas testimony about the jurors' subjective thought processes is inadmissible under the federal rule. Defense counsel further contended that Tanner is inapposite because, unlike federal law, Texas law does not recognize this distinction between objective misconduct and subjective mental processes but rather excludes all juror testimony, whether it pertains to objective facts or subjective thought processes. Defense counsel's contention, however, is incorrect for a number of reasons. First, and most important, Tanner clearly did not turn on a distinction between objective misconduct and subjective juror thought processes.

In fact, Tanner dealt specifically with, and upheld the exclusion of, juror testimony concerning objective misconduct (i.e., the consumption of alcohol and illicit substances); it simply did not involve testimony concerning the jurors' subjective thought processes or the effect of anything on their decision in reaching their verdict. See id. at 118-20, 107 S.Ct. 2739. Contrary to defense counsel's argument, the Court made clear in Tanner that not all evidence of objective misconduct occurring during juror deliberations is admissible under Fed.R.Evid. 606(b), and it held that the exclusion of juror testimony about the jury's internal deliberations is not only constitutionally permissible but is also likely necessary to preserve the vitality of our jury system. Id. at 120, 126-27, 107 S.Ct. 2739; see also Anderson v. Miller, 346 F.3d 315, 325-26 (2d Cir.2003) (discussing the centrality of the jury to our justice system). Second, defense counsel misconstrued the difference between the federal rule and the Texas rule by stating that Texas law does not recognize the distinction made in federal law between juror testimony concerning objective misconduct and testimony concerning jurors' subjective thought processes. In fact, the Texas rule includes language virtually identical to the federal rule, providing that: “a juror may not testify as to ··· the effect of anything on any juror's mind or emotions or mental processes, as influencing any juror's assent to or dissent from the verdict or indictment.” Tex.R. Evid. 606(b). Thus, both Fed.R.Evid. 606(b) and Tex.R. Evid. 606(b) bar all juror testimony concerning the jurors' subjective thought processes.FN30 Accordingly, Salazar's attempt to distinguish Tanner fails, and we cannot say that the state habeas court's application of Texas Rule 606(b) to bar testimony by the jurors concerning their internal discussion of parole law during deliberations was contrary to, or an unreasonable application of, clearly established federal law as determined by the Supreme Court.

* * *

III. CONCLUSION

Given the relevant Supreme Court precedents discussed above, we conclude the state habeas court's adjudication of Salazar's due process claim did not result in a decision that was contrary to, or involved an unreasonable application of, clearly established federal law as determined by the Supreme Court. “[T]he Constitution entitles a criminal defendant to a fair trial, not a perfect one.” Delaware v. Van Arsdall, 475 U.S. 673, 681, 106 S.Ct. 1431, 89 L.Ed.2d 674 (1986). The state court in this particular case conducted a full hearing on the question, and it concluded that, in light of the conflicting evidence, Salazar failed to establish that he had been denied a fair and impartial trial. Regardless, the only evidence that Salazar presented in support of his claim of jury misconduct was the conflicting testimony of certain jurors that during deliberations one or more jurors may have made factually inaccurate statements about parole law. The state court's conclusion that this evidence was inadmissible under Tex.R. Evid. 606(b) was entirely consistent with the Supreme Court's holding in Tanner, which recognized the need to balance the defendant's interest in a post-verdict inquiry with the substantial interest in protecting the finality of judicial proceedings, full and frank discussions in the jury room, jurors' willingness to return an unpopular verdict, and the community's trust in the jury system. Accordingly, Salazar has not satisfied the standard set forth in § 2254, and we therefore AFFIRM the judgment of the district court denying his habeas petition.

In re Salazar, --- F.3d ----, 2006 WL 679018(5th Cir. 2006) (Successive Habeas)

Background: Death-row inmate, following affirmance of his murder conviction, 38 S.W.3d 141, and exhaustion of his initial state and federal habeas claims, moved for authorization to file successive petition for writ of habeas corpus in federal district court.

Holding: The Court of Appeals held that inmate's mental retardation claim lacked sufficient possible merit to warrant grant of authorization to file successive habeas petition.

PER CURIAM:

In March 1999, death-row inmate Robert Madrid Salazar was convicted of capital murder for the 1997 beating death and sexual assault of his girlfriend's two-year-old daughter. Having exhausted his initial state and federal habeas claims, Salazar faces execution, scheduled for March 22, 2006.

On February 14, 2006, Salazar filed a subsequent state application for writ of habeas corpus with the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals based on Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304, 122 S.Ct. 2242, 153 L.Ed.2d 335 (2002), which categorically bars the execution of mentally retarded persons. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals dismissed his application as an abuse of the writ, rejecting Salazar's assertion that he is mentally retarded and therefore exempt from execution under Atkins. Ex parte Salazar, No. WR-49,210-02 (Tex.Crim.App. Mar. 9, 2006) (per curiam).

Salazar, maintaining that he is mentally retarded, now moves in this court pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2244(b)(3)(A) for authorization to file a successive application for writ of habeas corpus with the United States District Court based on the new constitutional rule announced in Atkins. Salazar also moves for a stay of execution. Because we hold that Salazar has failed to establish a prima facie case of mental retardation, we DENY his motions.

* * *

II. PRIMA FACIE CASE OF MENTAL RETARDATION

While the Supreme Court in Atkins categorically barred the execution of mentally retarded persons, it declined to announce a uniform definition of mental retardation, noting that “[n]ot all people who claim to be mentally retarded will be so impaired as to fall within the range of mentally retarded offenders about whom there is a national consensus.”536 U.S. at 317, 122 S.Ct. 2242. The Court therefore left “to the State[s] the task of developing appropriate ways to enforce the constitutional restriction upon [their] execution of sentences,” id., but cited with approval the American Association on Mental Retardation (“AAMR”) definition of mental retardation. Id. at 309 n. 3, 122 S.Ct. 2242.

Since the Atkins decision, Texas courts addressing Atkins claims have followed the definition of mental retardation adopted by the AAMR and the almost identical definition contained in section 591.003(13) of the Texas Health & Safety Code. Under this standard, an applicant claiming mental retardation must show that he suffers from a disability characterized by “(1) ‘significantly subaverage’ general intellectual functioning,” usually defined as an I.Q. of about 70 or below; “(2) accompanied by ‘related’ limitations in adaptive functioning; (3) the onset of which occurs prior to the age of 18.” Ex parte Briseno, 135 S.W.3d 1, 7 (Tex.Crim.App.2004); see alsoTex. Health & Safety Code § 591.003(13) (Vernon 2003) (defining “mental retardation” as “significantly subaverage general intellectual functioning that is concurrent with deficits in adaptive behavior and originates during the developmental period”); Morris v. Dretke, 413 F.3d 484, 490 (5th Cir.2005) (applying the AAMR standard adopted in Briseno to a federal habeas claim based on Atkins). To state a successful claim, an applicant must satisfy all three prongs of this test. See Hall v. Texas, 160 S.W.3d 24, 36 (Tex.Crim.App.2004) (en banc).

We are convinced that Salazar's Atkins claim does not have sufficient possible merit to warrant further exploration by the district court. Salazar offers no affirmative evidence tending to show that he suffers from significantly subaverage general intellectual functioning or that any such intellectual functioning has been accompanied by related limitations in adaptive functioning. Specifically, he provides no proof in the form of test scores, school records, doctor reports, affidavits from teachers or family members, or any similar documentation indicating that he has ever been suspected of being mentally retarded, diagnosed with any other disability, or placed in a special needs program. In fact, the only two professionals ever personally to evaluate Salazar have concluded that he is not mentally retarded, and his scores on two separate I.Q. tests are above the cutoff for mental retardation, which Texas recognizes as a score of 70 or below. See Briseno, 135 S.W.3d at 7 n. 24 (noting that “[s]ignificantly subaverage intellectual functioning is defined as an IQ of about 70 or below (approximately 2 standard deviations below the mean)”).

In 1978, Salazar, who was eight years old at the time, scored a 102 on a Slosson Intelligence Test administered by Dr. Michael Ratheal. Dr. Ratheal, who administered several other tests to Salazar and performed a lengthy psychological evaluation, noted that Salazar's I.Q. score “suggests functioning in the Average range of intelligence.” Ratheal Report at 2. Although Salazar did receive low scores on the Vineland Adaptive Behavior test administered during the same session, Dr. Ratheal noted that the “scores indicate extremely low functioning in the areas of adaptive behavior, especially in consideration of Robert's average intellectual ability.” Ratheal Report at 5. Based on the totality of her examination, Dr. Ratheal did not conclude that Salazar was mentally retarded. Moreover, in 1999, while Salazar was twenty years old and awaiting trial for capital murder, he scored an 87 on the WAIS-R intelligence test administered by Dr. Antolin Llorente, who spent two days examining Salazar and administering a total of twenty-five tests. Like Dr. Ratheal, Dr. Llorente did not conclude that Salazar was mentally retarded based on his examination, noting in his report that Salazar's scores indicated that Salazar was “currently functioning within the upper end of the Low Average to low end of the Average range of intelligence.” Llorente Report at 5.

Attempting to cast doubt on the reliability of these assessments, Salazar offers the lone statement of Dr. Richard Garnett, a frequent expert witness in Texas capital cases who has experience in diagnosing and working with people with mental retardation. Dr. Garnett, who reviewed Salazar's medical records and I.Q. scores at the request of Salazar's attorney, asserts that the Slosson Test “should not be considered a valid indicator of Mr. Salazar's intellectual functioning” and that the test results “must be followed by a more formal and in-depth evaluation and diagnosis.” Garnett Report at 3. However, Dr. Garnett fails to note in his analysis that, in addition to administering the Slossen Test, Dr. Ratheal did perform an in-depth evaluation of Salazar, and her nine-page psychological evaluation report never suggested that Salazar might be mentally retarded, instead describing him as “a bright youngster” and “functioning in an average range of intellectual ability.” Ratheal Report at 6.

Dr. Garnett also posits that Salazar's later score of 87 on the WAIS-R test might have been artificially inflated because of a phenomenon called the “Flynn Effect.” This theory attributes the general rise of I.Q. scores of a population over time to the use of outdated testing procedures, emphasizing the need for the repeated renormalization of I.Q.-test standard deviations over time. Although Dr. Garnett describes the effect of this phenomenon on the average I.Q. score in the general population, he does not indicate what effect it would have had on Salazar's score in particular or even whether it is appropriate to adjust an individual's score based on this theory.FN1

Finally, Dr. Garnett emphasizes that Salazar scored poorly on the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Test administered by Dr. Ratheal and that these scores could be indicative of mental retardation. Although this fact, standing alone, might be troubling, the definition for mental retardation adopted by the AAMR and by the state of Texas requires us to consider the data in context. Thus, Dr. Ratheal's note that Salazar's adaptive behavior “scores indicate extremely low functioning in the areas of adaptive behavior, especially in consideration of Robert's average intellectual ability” indicates that, while Salazar might have suffered from limitations in adaptive behavior as a child, it was not accompanied by the significantly subaverage general intellectual functioning required under the definition. Ratheal Report at 5 (emphasis added); seeTex. Health & Safety Code § 591.003(13) (defining mental retardation as subaverage general intellectual functioning that is “concurrent with” deficits in adaptive behavior); Hall, 160 S.W.3d at 36 (requiring that all three prongs of the definition be satisfied for a successful claim of mental retardation). In short, no professional who has ever personally evaluated Salazar has labeled him mentally retarded, and Salazar offers no support for his claim other than the statement of Dr. Garnett, who never personally evaluated or tested Salazar. Dr. Garnett's statement, without more, “is simply insufficient to suggest that further development of [Salazar's] claim has any likelihood of success under the Atkins criteria.” In re Johnson, 334 F.3d 403, 404 (5th Cir.2003) (denying a motion for authorization to file a successive habeas application based on Atkins where the applicant offered only two letters from psychologists and a seventh-grade transcript showing poor grades); In re Campbell, 82 Fed.Appx. 349, 350 (5th Cir.2003) (denying a motion for authorization where the applicant did not provide any evidence of mental impairment or cognitive dysfunction). Because Salazar has failed to state a prima facie case of mental retardation, we cannot grant his motion for authorization to file a successive habeas application in district court. FN2

III. CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, we DENY Salazar's motion for authorization to file a successive habeas application based on Atkins. His motion for a stay of execution is also DENIED.

FN1. Even assuming that the Flynn Effect is a valid scientific theory and is applicable to Salazar's individual I.Q. score-and we express no opinion as to whether this is actually the case-Salazar's score readjusted to account for score inflation is still above the cutoff for mental retardation. Dr. Garnett explains that, under the Flynn Effect theory, the passage of time has inflated test scores by approximately one-third to two-thirds of a point per year since the normalization of the particular test in question. Therefore, one can establish a range of estimated score inflation by taking the number of years that has [sic] passed since the standardization norms were established and the date of test admission, and then multiply .3 and .6 to get the range of inflation. Those amounts are subtracted from the IQ score to obtain the range of effect. Garnett Report at 5. Salazar took his WAIS-R test in 1999, twenty-one years after it was normalized; thus, using the above equation, his readjusted score would range from 80.7 to 74.4, both of which are above the cutoff score of 70.

FN2. We also note that, even if we were to grant Salazar's motion for authorization to file a successive habeas application, his application would be time barred in district court under the AEDPA one-year limitations provision unless equitable tolling were deemed appropriate. See28 U.S.C. § 2244(d)(1)(C) (limiting the period for filing a successive habeas application based on a new rule of retroactively applicable constitutional law to one year from “the date on which the constitutional right asserted was initially recognized by the Supreme Court”). The Supreme Court issued its decision in Atkins on June 20, 2002; therefore, the AEDPA limitations period expired on June 20, 2003, more than two and a half years ago. See Hearn, 376 F.3d at 455 n. 11.

The state urges us to deny Salazar's motion solely on the ground that the successive application would be time barred under § 2244(d)(1)(C) without addressing whether Salazar has made a sufficient prima facie showing as required for authorization under 28 U.S.C. § 2244(b)(3)(C). However, we need not make this determination-or answer the open question of whether, in our role as “gatekeeper” under § 2244(b)(3)(C), we have the statutory authority to deny a motion for authorization solely on the basis of timeliness under § 2244(d)(1)(C)-because we hold that Salazar has failed to make a prima facie showing that the application satisfies the requirements of § 2244(b). Cf. In re Wilson, --- F.3d ----, 2006 WL 574273 (5th Cir.) (granting a motion for authorization to file a successive habeas application based on Atkins after holding that the applicant had made a prima facie case of mental retardation and determining that equitable tolling would apply to save his application from being untimely in the district court under § 2244(d)(1)(C)); In re Elizalde, No. 06-20072 (5th Cir. Jan. 31, 2006) (denying a similar motion on the ground that the applicant had failed to establish a prima facie case of mental retardation and also noting in dicta that his application would likely be time barred in district court).