Executed June 20, 2007 06:19 p.m. CST by Lethal Injection in Texas

24th murderer executed in U.S. in 2007

1081st murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

16th murderer executed in Texas in 2007

395th murderer executed in Texas since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

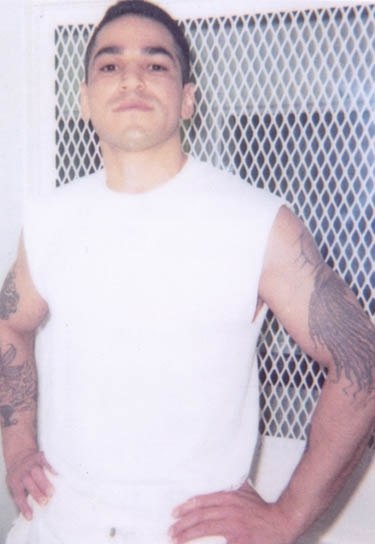

Lionell Gonzales Rodriguez H / M / 19 - 36 |

Tracy A. Gee Asian / F / 22 |

09-20-94 |

Citations:

Rodriguez v. Quarterman, 204 Fed.Appx. 489 (5th Cir. 2006) (Habeas).

Final/Special Meal:

Refused.

Final Words:

"You have every right to hate me. You have every right to want to see this. To you and my family, you all don't deserve to see this. It is the right thing to do. None of this should have happened. I've got a good family just like you're a good family. I couldn’t do this in a letter,” I had to do this face to face, eye to eye.” Rodriguez said he hoped that Gee's family could put aside any bitterness because of what he did. "I'm responsible. I'm responsible. I'm sorry to you all. This should have never happened." He thanked his relatives adding, "We'll see each other again." He muttered a brief prayer, mouthed them a kiss and closed his eyes as the lethal drugs began to take effect.

Internet Sources:

Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Executed Offenders (Lionell Rodriguez)

Inmate: Rodriguez, Lionell

Wednesday, June 13, 2007 - Media Advisory: Lionell Rodriguez scheduled for execution

AUSTIN – Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott offers the following information about Lionell Gonzalez Rodriguez, who is scheduled to be executed after 6 p.m. Wednesday, June 20, 2007.

After a second jury trial, a Harris County jury sentenced Rodriguez to death for killing Tracy Gee and stealing her car. Rodriguez’s first conviction was overturned because the jury cards were shuffled twice. Shuffling determines the order in which jurors are considered for the panel.

FACTS OF THE CRIME

On September 5, 1990, then nineteen-year-old Lionell Rodriguez, with a shotgun and automatic rifle he had stolen from his stepfather the day before, joined his cousin, James Gonzales, in driving around town looking for a place to rob.

At a stop light at the intersection of South Rice and North Braeswood, Rodriguez noticed a young woman sitting alone at the wheel of a car next to them. Rodriguez aimed the rifle at the woman and fired one time.

He jumped out of the vehicle and ran over, dumped the woman’s body on the street and drove off in her car.

The young woman was Tracy Gee, age 22. Tracy, the youngest in a big family, had been working a double shift that night, covering for her sister who was pregnant.

Rodriguez was arrested in Gee’s car four hours later in Fort Bend County. The interior of the car and Rodriguez’s pants were soaked in Tracy’s blood, and her bone, blood and brain matter was clotted throughout his hair. He confessed to killing Gee.

During the sentencing phase of trial, the State also presented evidence of Rodriguez’s lengthy criminal history, including the revocation of juvenile probation for offenses committed while on probation. In addition, several citizens testified about Rodriguez’s extremely violent and assaultive temper, including the motorist at whom Rodriguez fired several rounds on the night of the offense. Several witnesses testified about Rodriguez’s extremely violent behavior during his incarceration at the Harris County Jail.

Rodriguez’s codefendant, cousin James Gonzales, got 30 years for aggravated robbery.

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

05/23/91 -- Rodriguez was found guilty of capital murder.

05/29/91 --The trial judge sentenced Rodriguez to death.

12/15/93 -- The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals reversed the conviction because the jury was shuffled twice.

9/14/94 -- Rodriguez was found guilty of capital murder a second time.

9/20/94 -- The 185th state District Court judge sentenced Rodriguez to death.

9/01/95 -- Rodriguez filed a direct appeal raising 31 points of error.

2/5/97 -- The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed Rodriguez’s conviction and sentence.

3/27/98 -- Rodriguez filed an application for state writ of habeas corpus raising 13 issues.

10/8/01 -- State Writ denied..

10/23/02 -- The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals found the habeas court’s findings supported by the record and denied relief.

7/3/03 -- Rodriguez filed an amended federal habeas corpus petition raising 17 claims in a Houston U.S. district court.

03/24/04 -- The federal district court dismissed Rodriguez’s federal habeas petition.

04/23/04 -- Rodriguez filed notice of appeal in the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

5/29/05 -- The federal district court denied relief but granted certificate of appealability (“COA”) on one claim.

10/19/05 -- Rodriguez filed an application for additional COA to include six additional claims in the 5th Circuit Court.

9/11/06 -- The 5th Circuit Court denied Rodriguez’s motion for COA and affirmed the denial of habeas relief.

2/13/07 -- Rodriguez petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court for certiorari review of the 5th Circuit Court’s opinion.

4/16/07 -- The Supreme Court denied certiorari review.

"Convicted Houston carjacker executed Wednesday," by Michael Graczyk. (Associated Press June 20, 2007, 6:39PM)

HUNTSVILLE, Texas — Apologetic convicted killer Lionell Rodriguez was executed Wednesday evening for the fatal shooting almost 17 years ago of a Houston woman during a carjacking just three weeks after he had been paroled from prison. "You have every right to hate me. You have every right to want to see this. To you and my family, you all don't deserve to see this," Rodriguez told the relatives of Tracy Gee, as he looked directly at them as they watched through a window nearby. He said he did not write them a letter to apologize because he wanted to do it "face-to-face." "It is the right thing to do. None of this should have happened. I've got a good family just like you're a good family," he continued.

Rodriguez said he hoped that Gee's family could put aside any bitterness because of what he did. "I'm responsible. I'm responsible," he repeated. "I'm sorry to you all. This should have never happened." He thanked his relatives who watched through another window, adding, "We'll see each other again." He muttered a brief prayer, mouthed them a kiss and closed his eyes as the lethal drugs began to take effect. He was pronounced dead at 6:19 p.m., eight minutes later.

The execution of Rodriguez, 36, was the 16th this year and the first of two on consecutive evenings in the nation's most active death penalty state.

The U.S. Supreme Court two months ago refused to review Rodriguez's case, and his lawyers said there were no legal avenues left to try to spare him. "We did our best," attorney Alex Calhoun said. "Unfortunately, the courts didn't quite agree with our estimation of a lot of the facts."

Rodriguez was 19 and free after serving less than five months of a seven-year prison term for burglary and cocaine possession when he and a cousin decided to prowl Houston to act out fantasies they'd seen in the movies. They failed to hold up a gas station because there were too many people around the place. They shot at a motorist in Fort Bend County.

When they pulled up at a stoplight in Houston alongside a car driven by Gee, a 22-year-old who was almost home on her way back from her job at a tennis pro shop, Rodriguez wanted her car because theirs was running low on gas. His cousin, James Gonzales, slid back in the driver's seat to give Rodriguez a clear shot with a .30-caliber M-1 rifle he'd stolen from his stepfather, a Fort Bend County police officer.

The bullet shattered the passenger side window of Gee's car and struck her in the head, fatally wounding her. Rodriguez jumped into her car, pushed her body to the pavement and drove over her as he sped away.

Gonzales, still driving his own car, soon after tried to flee from an officer who was pulling him over for a broken taillight. Fearing he was being stopped for Gee's shooting, he told officers Rodriguez was the gunman. Police then tracked down Rodriguez near his home in Fort Bend County. When arrested, he was in Gee's car, the inside of it splattered with her remains.

"It's one of those things where there's not a whole lot of doubt about what happened and who did it," said Harris County District Attorney Chuck Rosenthal, who handled the case as an assistant prosecutor. "We had her brains and bone and blood in his hair and all over his body after he sat in the seat where he shot her." Rodriguez confessed. A Harris County jury convicted him of capital murder and decided he should die.

The blood evidence and the confession were insurmountable to his defense, said J.C. Castillo, Rodriguez's trial lawyer. "I'd like to think I tried everything," he said. "But when it comes down to the day being over, it's basically, 'Please spare his life, he's so young and there's room for improvement.' It didn't help." Gonzales received a 40-year prison term.

Rodriguez's conviction was overturned by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals in 1993 because of a procedural problem in jury selection. The following year, he was convicted a second time and again sentenced to death.

Another inmate, Gilberto Reyes, was to follow Rodriguez to the death chamber Thursday evening. Reyes, 33, was condemned for the 1998 rape-slaying of a former girlfriend, Yvette Barraz. She was abducted, beaten and strangled after leaving her job as a waitress in Muleshoe along the Texas-New Mexico state line.

"Man executed in shooting death of Fort Bend County woman," by Robbie Byrd. (June 21, 2007 12:28 a.m.)

Lionell Rodriguez apologized to the family of the woman he murdered some 17 years ago in downtown Houston before becoming the 16th inmate to be executed in Texas this year. But the family of Tracy Gee, 19 at the time of her brutal murder, had nothing to say and simply stared ahead at Rodriguez as he was executed.

Rodriguez was strapped to the gurney at 6:02 p.m. and was pronounced dead at 6:19 p.m., just 8 minutes after the lethal dose began to flow. “First off, you have every right to hate me and every right to want to see this,” he said, turning to look toward Gee’s two sisters and three brothers-in-law who came to witness the execution. “None of this should have happened.” Rodriguez apologized several times, not only for the crime but for not expressing his remorse until he lay on the execution gurney. “I couldn’t do this in a letter,” he said. “I had to do this face to face, eye to eye.”

Rodriguez told Gee’s family that he asked his family to contact them, hoping that the Gee family held no bitterness because “they did no wrong.” “I’m responsible, I’m responsible,” he said. “I’m sorry to you all. This never should have happened. To ... my family, you all don’t deserve to see this (but) it is the right thing to do.” Tearfully, Rodriguez’s brother waved goodbye, as other family members looked ahead.

Rodriguez’s father, Henry Rodriguez, held his hand on the glass seperating him from his son, removing it only once to comfort his other two sons and family friends who came to witness the execution. “We’ll see each other again,” Rodriguez said. Just moments before losing consciousness, Rodriguez spoke a quiet prayer, turned to his family, smiled and mouthed them a kiss.

The execution of Rodriguez, 36, was the first of two on consecutive evenings in the nation’s most active death penalty state.

The U.S. Supreme Court two months ago refused to review Rodriguez’s case, and his lawyers said there were no legal avenues left to try to spare him. “We did our best,” attorney Alex Calhoun said. “Unfortunately, the courts didn’t quite agree with our estimation of a lot of the facts.”

Rodriguez was 19 and free after serving less than five months of a seven-year prison term for burglary and cocaine possession when he and a cousin decided to prowl Houston to act out fantasies they’d seen in the movies. They failed to hold up a gas station because there were too many people around the place. They shot at a motorist in Fort Bend County.

When they pulled up at a stoplight in Houston alongside a car driven by Gee, a 22-year-old who was almost home on her way back from her job at a tennis pro shop, Rodriguez wanted her car because theirs was running low on gas. His cousin, James Gonzales, slid back in the driver’s seat to give Rodriguez a clear shot with a .30-caliber M-1 rifle he’d stolen from his stepfather, a Fort Bend County police officer.

The bullet shattered the passenger side window of Gee’s car and struck her in the head, fatally wounding her. Rodriguez jumped into her car, pushed her body to the pavement and drove over her as he sped away.

Gonzales, still driving his own car, soon after tried to flee from an officer who was pulling him over for a broken tail light. Fearing he was being stopped for Gee’s shooting, he told officers Rodriguez was the gunman. Police then tracked down Rodriguez near his home in Fort Bend County.

When arrested, he was in Gee’s car, the inside of it splattered with her remains. “It’s one of those things where there’s not a whole lot of doubt about what happened and who did it,” said Harris County District Attorney Chuck Rosenthal, who handled the case as an assistant prosecutor.

Rodriguez confessed. A Harris County jury convicted him of capital murder and decided he should die. The blood evidence and the confession were insurmountable to his defense, said J.C. Castillo, Rodriguez’s trial lawyer. “I’d like to think I tried everything,” he said. “But when it comes down to the day being over, it’s basically, ‘Please spare his life, he’s so young and there’s room for improvement.’ It didn’t help.” Gonzales received a 40-year prison term.

Rodriguez’s conviction was overturned by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals in 1993 because of a procedural problem in jury selection. The following year, he was convicted a second time and again sentenced to death.

Another inmate, Gilberto Reyes, was to follow Rodriguez to the death chamber this evening. Reyes, 33, was condemned for the 1998 rape-slaying of a former girlfriend, Yvette Barraz. She was abducted, beaten and strangled after leaving her job as a waitress in Muleshoe along the Texas-New Mexico state line.

Texas Execution Information Center by David Carson.

Lionell Gonzales Rodriguez, 36, was executed by lethal injection on 20 June 2007 in Huntsville, Texas for the murder and robbery of a 22-year-old woman at a traffic intersection.

On 5 September 1990, Rodriguez, then 19, and his cousin, James Gonzales, 18, were driving in Houston with a shotgun and .30-caliber rifle in their car. They pulled up next to another car that was stopped for a red light at an intersection. Rodriguez, who was in the passenger's seat, aimed the rifle across Gonzales while he leaned back in the driver's seat. Rodriguez then fired once at the driver of the other car. The bullet passed through the other car's passenger window and hit the driver, Tracy Gee, 22, in the right temple, killing her. Rodriguez then got out of his car, pushed Gee's body out onto the pavement, and drove away in her car, with Gonzales following.

Soon afterward, police officer Theron Runnels pulled Gonzales over for driving with no taillights. Gonzales exited his car and initially approached Officer Runnels, but then he ran. After a chase, a second officer, Randy West, arrested him. In the meantime, Runnels found the M-1 carbine rifle and the shotgun in his car. When West brought Gonzales back to the car, Gonzales blurted out, "I did not kill that girl. It was my cousin." Rodriguez was arrested four hours later in Fort Bend County while driving Gee's car. His pants and the interior of the car were soaked with blood, and he had bone and brain matter clotted in his hair.

Rodriguez gave a full confession. He said that earlier that night, he had a fight with his mother and sister. He then stole the rifle and shotgun from his stepfather. He and Gonzales then drove around Houston, looking for a place to rob. They contemplated robbing a gas station, but the station was too busy, and they lost their nerve. Rodriguez then became angry at another driver and fired several shots at him in a residential neighborhood. When he noticed a young woman sitting alone in her car, he decided to rob her. He said that he was aiming for the victim's shoulder, but shot her in the temple.

In addition to the above evidence and confession, police found gunpowder residue in Gonzales' car.

Rodriguez had prior convictions for burglary and cocaine possession. He served 3½ months of a 4-year sentence before receiving parole. (At the time, early release was common in Texas due to strict prison population caps imposed by U.S. District Judge William Wayne Justice.) He had been on parole for about three weeks when he killed Tracy Gee.

Other witnesses testified to Rodriguez's violent temper at his punishment hearing. The other driver who Rodriguez fired shots at on the night of the murder also testified against him, as did another witness who testified that Rodriguez once assaulted him and hit his car with a baseball bat. Deputies at the Harris County Jail testified that Rodriguez was classified as an escape threat and as "aggressive towards staff," and was always put in leg irons and handcuffs when being moved.

A jury convicted Rodriguez of capital murder in May 1991 and sentenced him to death. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals reversed his conviction in December 1993 because the jury cards - which determine the order in which potential jurors are considered for the panel - were shuffled twice. Rodriguez was tried again and in September 1994 was again found guilty of capital murder and sentenced to death. The TCCA affirmed this conviction and sentence in February 1997. All of his subsequent appeals in state and federal court were denied. James Gonzales was convicted of aggravated robbery and sentenced to 40 years in prison. He remains in custody as of this writing.

In an interview from death row the week before his execution, Rodriguez said that on the night of the murder, he and his cousin decided to go and act out some fantasies from the movies. After backing out on robbing a gas station and shooting at a motorist, they saw their car was running low on gas, and spotted Gee alone in her car. "It should've never happened," Rodriguez said in the interview. "Not only did I bring so much pain and heartache to the Gee family, but also to my family. I destroyed two families ... Of all the pain I caused, I'm ashamed." Rodriguez said he hoped that the victim's family could forgive him. He also said that he matured and became more spiritual over the past 17 years and did not want people to think of him as a monster. "Don't make me look any worse than I already do," he pleaded to a reporter.

At Rodriguez' second trial, jurors heard testimony from defense witnesses about how he had changed in the 2½ years since his first trial, but the jury nevertheless found that he was a continuing danger to society. "People on juries ... they actually believe we'll never change for the better." Rodriguez said. "They figure we're better off dead. But people change with time."

At his execution, Rodriguez, strapped to the gurney, craned his head to face the victim's family members who attended. "You have every right to hate me.. You have every right to want to see this," he said to them in his last statement. "I couldn't do this in a letter. I had to do this face to face, eye to eye. None of this should have happened." He said he hoped that the family could forgive him. "I'm responsible. I'm responsible. I'm sorry to you all. This never should've happened. To ... my family, you all don't deserve to see this [but] it is the right thing to do." Rodriguez also thanked his family members and told them, "We will see each other again." As the lethal injection was started, he whispered, "Lord Jesus, receive my spirit. Lord Jesus, receive my spirit." He was pronounced dead at 6:19 p.m.

Lionell Rodriguez confessed to the murder for which he was convicted. According to Rodriguez’s confession, he became physically abusive in an altercation with his mother and sister on the night of the murder. He then stole a shotgun and an automatic rifle from his stepfather and drove around with his cousin, Jaime Gonzalez, looking for a place to rob. Rodriguez unsuccessfully attempted to rob a gas station. While driving around, Rodriguez became angry at another driver and repeatedly fired shots at him. This occurred in a residential neighborhood. The other driver drove safely away and, at a distance, turned his car around to write down Rodriguez’s license plate number. Rodriguez jumped out of his car and fired another shot at the other driver.

Rodriguez and Gonzalez continued driving. While stopped at a stop light, Rodriguez noticed a young woman, Tracy Gee, sitting alone in her car. He decided to rob her and steal the car. He confessed to shooting at her one time with the rifle. The shot pierced the passenger side window and Gee’s head fell forward. Her car started rolling, and Rodriguez jumped out of his car and ran over to the other car. He managed to get into the car and pushed Gee out the driver side door onto the street. He then drove off in the stolen car.

Gonzalez drove away from the scene, and a police officer, Theron Runnels, pulled him over. Gonzalez exited the car and, after initially approaching the officer, began to run. After a chase, a second officer, Randy West, arrested Gonzalez for evading arrest. In the meantime, Runnels found a rifle and shotgun in the car. When West brought Gonzalez to Runnels so that the latter could identify him, Gonzalez shouted that he did not kill Gee but that his cousin did. Rodriguez was arrested in the victim’s car while fleeing the scene of the crime. His pants were stained with blood, and there was blood, bone, and brain matter inside the car. Rodriguez had brain matter in his hair.

Police also recovered a fired bullet from the victim’s car and found gunpowder residue in Gonzalez’s car. The gunpowder residue showed that a gun was fired from inside that car. An autopsy revealed a massive entrance gunshot wound to Gee’s right temple that had very large lacerations radiating around it, and an exit wound with extensive lacerations on the left forehead. Gee’s skull had massive fractures. Some of her brain extruded through the wounds. Gee lost some bone fragments from her skull when she was shot. The cause of death was the gunshot wound.

During Rodriguez’s sentencing, the State presented evidence that Rodriguez shot at the other driver. Officers Runnels and West testified that, when West brought Gonzalez to the scene of the crime where Runnels was performing inventory on Gonzalez’s car, Gonzalez stated that his cousin, Rodriguez, killed Gee. The State produced evidence that Rodriguez burglarized an elementary school in January 1990. Rodriguez received probation for the burglary, but his probation was later revoked. His probation officer testified that Rodriguez was physically abused by an alcoholic father during childhood. The probation officer characterized Rodriguez as having average to somewhat above average intelligence and having the potential to do something with his life.

The State introduced records from the Harris County Jail naming Rodriguez as an “escape threat” and as “aggressive towards staff,” instructing jail staff to use handcuffs and leg irons when moving Rodriguez from his cell. A Harris County Sheriff’s Deputy testified that, during Rodriguez’s incarceration at the Harris County Jail on the capital murder charge, there was a standing order that Rodriguez was to wear leg irons and handcuffs when he was out of his cell. Rodriguez became belligerent to a jail deputy while being brought to a visit with his mother. Upon returning to his cell, Rodriguez broke a window. There was also evidence that while at Harris County Jail, Rodriguez was frequently disruptive, and jail staff tried to perform a daily search of his cell for shanks or weapons. During one of these searches, deputies found a homemade shank.

Veronica Vinton and her father testified that, after Veronica refused Rodriguez’s request for a date, Rodriguez stalked her. Another witness testified that Rodriguez assaulted him and damaged his car with a baseball bat. Other witnesses testified that Rodriguez had a bad reputation for not abiding by the law. Gee’s sister Susan offered victim impact testimony. She testified that her mother’s health was affected by Tracy Gee’s death. She also described Tracy as a person of integrity, and one who loved children.

UPDATE: Apologetic convicted killer Lionell Rodriguez was executed for the fatal shooting almost 17 years ago of a Houston woman during a carjacking just three weeks after he had been paroled from prison. "You have every right to hate me. You have every right to want to see this. To you and my family, you all don't deserve to see this," Rodriguez told the relatives of Tracy Gee, as he looked directly at them as they watched through a window nearby. He said he did not write them a letter to apologize because he wanted to do it "face-to-face." "It is the right thing to do. None of this should have happened. I've got a good family just like you're a good family," he continued. Rodriguez said he hoped that Gee's family could put aside any bitterness because of what he did. "I'm responsible. I'm responsible," he repeated. "I'm sorry to you all. This should have never happened." He thanked his relatives who watched through another window, adding, "We'll see each other again." He muttered a brief prayer, mouthed them a kiss and closed his eyes as the lethal drugs began to take effect. He was pronounced dead at 6:19 p.m., eight minutes later. "It's one of those things where there's not a whole lot of doubt about what happened and who did it," said Harris County District Attorney Chuck Rosenthal, who handled the case as an assistant prosecutor. "We had her brains and bone and blood in his hair and all over his body after he sat in the seat where he shot her."

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

Lionel Rodriguez, TX, June 20

Do Not Execute Lionel Rodriguez!

On June 20, Texas is set to execute Lionel Rodriguez for the September 1990 murder of Tracy Gee.

The state of Texas should not execute Rodriguez for his role in this crime. Executing Rodriguez would violate the right to life as declared in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and constitute the ultimate cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment. Furthermore, Rodriguez suffered abuse as a child from his alcoholic father.

Please write to Gov. Rick Perry on behalf of Lionel Rodriguez!

Rodriguez v. Quarterman, 204 Fed.Appx. 489 (5th Cir. 2006) (Habeas).

Background: Following affirmance of his state court conviction of capital murder and sentence of death, and denial of his state court habeas application, petitioner sought federal writ of habeas corpus. The United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas denied petition and granted certificate of appealability (COA) in part. Petitioner appealed.

Holdings: The Court of Appeals held that:

(1) accomplice's out-of-court statement to police was admissible as excited utterance;

(2) such statement and defendant's jail disciplinary records were admissible under prevailing law at time petitioner's conviction became final;

(3) prospective juror who had previously been convicted of theft and who had successfully completed probation was subject to challenge for cause;

(4) claim of ineffective assistance of counsel in sentencing proceedings was not cognizable by petition for federal writ of habeas corpus; and

(5) defense counsel did not provide ineffective assistance at sentencing.

Affirmed; certificate of appealability denied.

PER CURIAM:

(Pursuant to 5th Cir. R. 47.5, the court has determined that this opinion should not be published and is not precedent except under the limited circumstances set forth in 5th Cir. R. 47.5.4.)

Treating the Petition for Rehearing En Banc as a Petition for Panel Rehearing, the Petition for Panel Rehearing is DENIED in part and GRANTED in part as reflected in the substitute opinion filed today. No member of the panel nor judge in regular active service of the court having requested that the court be polled on Rehearing En Banc (Fed. R.App. P. and 5th Cir. R. 35), the Petition for Rehearing En Banc is DENIED. We withdraw our previous opinion and substitute the following.

Lionel Gonzales Rodriguez was convicted in Texas state court for the murder of Tracy Gee. He now seeks habeas corpus relief from his sentence of death. After denying habeas relief on all claims, the district court granted Rodriguez a certificate of appealability (“COA”) on one issue: whether Rodriguez's death sentence violated his constitutional rights because he received ineffective assistance of counsel (“IAC”) in the punishment phase of his trial. We find that Rodriguez's claim is meritless and AFFIRM the denial of habeas relief. We DENY Rodriguez's request for a COA on all other issues.

I. These are the facts as recounted by the district court:

Rodriguez confessed to the murder for which he was convicted. According to Rodriguez's confession, he became physically abusive in an altercation with his mother and sister on the night of the murder. He then stole a shotgun and an automatic rifle from his stepfather and drove around with his cousin, Jaime Gonzalez, looking for a place to rob. Rodriguez unsuccessfully attempted to rob a gas station. While driving around, Rodriguez became angry at another driver and repeatedly fired shots at him. This occurred in a residential neighborhood. The other driver drove safely away and, at a distance, turned his car around to write down Rodriguez's license plate number. Rodriguez jumped out of his car and fired another shot at the other driver.

Rodriguez and Gonzalez continued driving. While stopped at a stop light, Rodriguez noticed a young woman, Tracy Gee, sitting alone in her car. He decided to rob her and steal the car. He confessed to shooting at her one time with the rifle. The shot pierced the passenger side window and Gee's head fell forward. Her car started rolling, and Rodriguez jumped out of his car and ran over to the other car. He managed to get into the car and pushed Gee out the driver side door onto the street. He then drove off in the stolen car.

Gonzalez drove away from the scene, and a police officer, Theron Runnels, pulled him over. Gonzalez exited the car and, after initially approaching the officer, began to run. After a chase, a second officer, Randy West, arrested Gonzalez for evading arrest. In the meantime, Runnels found a rifle and shotgun in the car. When West brought Gonzalez to Runnels so that the latter could identify him, Gonzalez shouted that he did not kill Gee but that his cousin did.

Rodriguez was arrested in the victim's car while fleeing the scene of the crime. His pants were stained with blood, and there was blood, bone, and brain matter inside the car. Rodriguez had brown matter in his hair. Police also recovered a fired bullet from the victim's car and found gunpowder residue in Gonzalez's car. The gunpowder residue showed that a gun was fired from inside that car.

An autopsy revealed a massive entrance gunshot wound to Gee's right temple that had very large lacerations radiating around it, and an exit wound with extensive lacerations on the left forehead. Gee's skull had massive fractures. Some of her brain extruded through the wounds. Gee lost some bone fragments from her skull when she was shot. The cause of death was the gunshot wound.

During Rodriguez's sentencing, the State presented evidence that Rodriguez shot at the other driver. Officers Runnels and West testified that, when West brought Gonzalez to the scene of the crime where Runnels was performing inventory on Gonzalez's car, Gonzalez stated that his cousin, Rodriguez, killed Gee.

The State produced evidence that Rodriguez burglarized an elementary school in January 1990. Rodriguez received probation for the burglary, but his probation was later revoked. His probation officer testified that Rodriguez was physically abused by an alcoholic father during childhood. The probation officer characterized Rodriguez as having average to somewhat above average intelligence and having the potential to do something with his life.

The State introduced records from the Harris County Jail naming Rodriguez as an “escape threat” and as “aggressive towards staff,” instructing jail staff to use handcuffs and leg irons when moving Rodriguez from his cell. A Harris County Sheriff's Deputy testified that, during Rodriguez's incarceration at the Harris County Jail on the capital murder charge, there was a standing order that Rodriguez was to wear leg irons and handcuffs when he was out of his cell. Rodriguez became belligerent to a jail deputy while being brought to a visit with his mother. Upon returning to his cell, Rodriguez broke a window. There was also evidence that while at Harris County Jail, Rodriguez was frequently disruptive, and jail staff tried to perform a daily search of his cell for shanks or weapons. During one of these searches, deputies found a homemade shank.

Veronica Vinton and her father testified that, after Veronica refused Rodriguez's request for a date, Rodriguez stalked her. Another witness testified that Rodriguez assaulted him and damaged his car with a baseball bat. Other witnesses testified that Rodriguez had a bad reputation for not abiding by the law. Gee's sister Susan offered victim impact testimony. She testified that her mother's health was affected by Tracy Gee's death. She also described Tracy as a person of integrity, and one who loved children.

Rodriguez's sister, Veronica Lopez, testified on Rodriguez's behalf. She testified that he became very angry and rude when he was on crack. She never saw Rodriguez get violent with anyone. She testified that Rodriguez changed dramatically in the time between the murder and his trial. He had adapted to being in prison and started a program creating pamphlets that he and other inmates would send to juvenile homes and churches so that young people could read about how the inmates wound up on death row and could avoid the same fate.

Rodriguez's uncle testified that he is a recovering alcoholic who became sober at age 23, the same age as Rodriguez at the time of his trial. He testified that he saw changes in Rodriguez, specifically in Rodriguez's desire to help others. Rodriguez's aunt testified that Rodriguez's father, Henry, abused drugs and alcohol and was extremely violent toward his wife and children. She also testified that Rodriguez changed and that he had a religious conversion while incarcerated. Rodriguez's great aunt corroborated that he experienced a religious conversion and that he was working to discourage kids from pursuing a path of crime.

Janie Warstler, Rodriguez's mother, testified that Henry was very abusive and an alcoholic. She also suspected that he was using drugs. Henry started taking Rodriguez to bars and giving him beer to drink when Rodriguez was six or seven years old. Rodriguez started using drugs in his early teens.

Henry threatened to kill Ms. Warstler on more than one occasion. He choked her and pushed her against a wall, threatened her with a knife, and tried to run her over. On one occasion, he used a shotgun to shoot down the door of Ms. Warstler's mother's house. He was also physically abusive to Rodriguez and his siblings, and once threatened Rodriguez's sister with a gun. He also abused the family pets and other animals.

When Rodriguez was fourteen, Janie left Henry, but Rodriguez insisted on staying with his father. Some time later, Rodriguez called his mother and told her that Henry was drunk all the time, was not buying groceries, and was not giving Rodriguez any lunch money. When Janie said she would come and get him, Rodriguez told her not to because he was afraid Henry would be there and would be violent. Janie sent her brothers to pick up Rodriguez.

Henry also testified and agreed with Janie's testimony. He also observed that Rodriguez has changed for the better during the time he has been in prison. Several other witnesses testified that Rodriguez has changed while in prison, experienced religious conversion, had no significant disciplinary problems, and was a positive influence on others.

The jury found that: (1) Rodriguez deliberately caused Tracy Gee's death and with the reasonable expectation that her death would occur; (2) there is a reasonable probability that Rodriguez would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society; and (3) there were not sufficient mitigating circumstances to warrant imposition of a sentence of life imprisonment rather than death. Accordingly, the Harris County jury convicted Rodriguez of capital murder and sentenced him to death on September 20, 1994.

II. On direct appeal, the Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed Rodriguez's conviction and sentence. Rodriguez v. State, No. 71,974 (Tex.Crim.App. Feb. 5, 1997). Rodriguez did not seek certiorari review in the Supreme Court of the United States. Instead, he timely filed a state habeas application on March 27, 1998. Rodriguez's application was denied by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals based on the trial court's findings of fact and conclusions of law. Ex parte Rodriguez, No. 50,773-01 (Tex.Crim.App. Oct. 23, 2002).

On July 3, 2003, Rodriguez timely filed an amended federal writ of habeas corpus.FN1 Rodriguez v. Dretke, No. H-03-317 (S.D.Tex.2005). On March 29, 2005, the district court ordered that all habeas relief be denied, and granted a COA on one claim. Rodriguez filed notice of appeal on May 19, 2005. Rodriguez appeals the denial of a COA on six claims and presents one claim on the merits.

FN1. Rodriguez filed a skeletal petition at first, and then, with leave of court, filed an amended application.

III. Because Rodriguez's habeas petition was filed in the district court after the effective date of the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (“AEDPA”), 28 U.S.C. § 2254, AEDPA governs his petition. See Lindh v. Murphy, 521 U.S. 320, 336, 117 S.Ct. 2059, 138 L.Ed.2d 481 (1997). We will consider Rodriguez's COA request first, followed by the issue for which the district court granted COA.

* * *

Rodriguez argues that reasonable jurists would find it debatable that: (1) the admission of Gonzalez's statement and Rodriguez's jail disciplinary records did not violate Rodriguez's Sixth Amendment right, (2) the challenge for cause of potential juror Anita Rodriguez did not violate Rodriguez's right to due process, and (3) the ineffective assistance of counsel he received with respect to each of the aforementioned alleged errors did not violate his Sixth Amendment right. Each claim will be addressed in turn.

1. Admission of Accomplice Statements and Jail Disciplinary Records

Rodriguez claims a COA should issue because reasonable jurists could debate whether his Sixth Amendment right was violated by the district court's admission of Gonzalez's statement implicating Rodriguez as Gee's murderer as an “excited utterance.” He also argues the admission of his jail disciplinary records and Gonzalez's statement violated the Sixth Amendment under Crawford v. Washington, 541 U.S. 36, 124 S.Ct. 1354, 158 L.Ed.2d 177 (2004).

a.

Rule 803(2) of the Texas Rules of Criminal Evidence FN2 states that an “excited utterance” is a “statement relating to a startling event or condition made while the declarant was under the stress of excitement caused by the event or condition.” Tex.R. Evid. 803(2). The “critical factor” for determining whether a statement is an excited utterance is “ ‘whether the declarant was still dominated by the emotions, excitement, fear, or pain of the event.’ ” Apolinar v. State, 155 S.W.3d 184, 186 (Tex.Crim.App.2005) (citing Zuliani v. State, 97 S.W.3d 589, 596 (Tex.Crim.App.2003)).

FN2. After Rodriguez's trial, the Texas Rules of Criminal Evidence changed its title to the Texas Rules of Evidence.

Reasonable jurists would not debate the district court's determination that Gonzalez's statement was an excited utterance, and that its admission did not violate the Sixth Amendment. In the district court, Rodriguez argued the facts are insufficient to show that Gonzalez's statement was spontaneous and unreflective, because of the period of time that had elapsed between Gonzalez's flight and his return to his vehicle. The district court concluded that Rodriguez's argument fails because an “excited utterance” is not defined by the period of time elapsed between the startling event and the statement made about it. See Zuliani, 97 S.W.3d at 596 (“[I]t is not dispositive that the statement is an answer to a question or that it was separated by a period of time from the startling event; these are simply factors to consider in determining whether the statement is admissible under the excited hearsay exception.”). The district court noted that: (1) Gonzalez blurted out his remarks concerning Tracy Gee's murder after fleeing a routine traffic stop, being chased by police officers, and being apprehended while weapons from within his vehicle were being inventoried by police, and (2) Gonzalez actually observed the events he described and his intervening actions, including hiding in a swimming pool and in someone's vehicle, and demeanor were known to the two officers. Rodriguez fails to make a substantial showing that he was denied his constitutional right.

b.

Rodriguez also argues that reasonable jurists could debate the district court's determination that the introduction of both Gonzalez's statement and the jail disciplinary records do not violate Crawford, FN3 541 U.S. 36, 124 S.Ct. 1354, 158 L.Ed.2d 177 (2004). See also U.S. Const. amends. VI, XIV. Rodriguez's arguments are barred by the non-retroactivity doctrine of Teague v. Lane. Lave v. Dretke, 444 F.3d 333, 337 (5th Cir.2006) (holding that the rule in Crawford is not to be applied retroactively); see also Teague v. Lane, 489 U.S. 288, 301, 109 S.Ct. 1060, 103 L.Ed.2d 334 (1989) (holding that, except in very limited circumstances, a federal habeas court cannot retroactively apply a new rule of criminal procedure).

FN3. Crawford v. Washington held that out-of-court testimonial statements are per se inadmissible against a criminal defendant unless the defendant has had a prior opportunity to cross examine the declarant. 541 U.S. 36, 68, 124 S.Ct. 1354, 158 L.Ed.2d 177 (2004).

Reasonable jurists would not debate the district court's determination that the state court admitted both Gonzalez's statement and the jail disciplinary records under prevailing law at the time that Rodriguez's conviction became final. The district court found that the officers' testimonies recounting Gonzalez's statement satisfied the Confrontation Clause because they qualified under a firmly-rooted hearsay exception. See White v. Illinois, 502 U.S. 346, 355 n. 8, 356, 112 S.Ct. 736, 116 L.Ed.2d 848 (1992). Rodriguez has not shown that a COA should be granted on this issue. See Teague, 489 U.S. at 301, 109 S.Ct. 1060. As to the jail disciplinary records, the district court determined that the trial court admitted the jail disciplinary records, over objection, under the business records exception to the general rule barring hearsay. The business records exception was applicable at the time of Rodriguez's trial and direct appeal. Tex.R.Crim. Evid. 803(6). Rodriguez fails to make a substantial showing that his constitutional right was denied by the admission of either of these pieces of evidence.

* * *

Rodriguez contends that trial counsel neither investigated nor presented evidence in relation to the etiological origins of his brain damage and the link between the damage to his brain's frontal lobes and his impulsive nature. Rodriguez's evidence consists of written statements found in the institutional records of the Orchard Creek Hospital, a psychiatric facility where Rodriguez was treated prior to his trial for Gee's murder, that were known to his counsel but were not presented at his trial. In addition, Rodriguez complains that his jury did not hear a neuro-psychologist's opinion that his abusive upbringing, lengthy drug addiction, and use of cocaine damaged his brain's frontal lobes. He argues that this unproffered evidence could have persuaded one juror to vote against the death penalty.

Rodriguez admitted that his counsel at his state habeas proceeding did not provide this claim to the state court. Pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2254(b)(1), Rodriguez should have fully exhausted remedies available to him in state court before proceeding to federal court; he should have presented the substance of his claim in the state court. Nobles v. Johnson, 127 F.3d 409, 420 (5th Cir.1997). “A habeas petitioner fails to exhaust state remedies ‘when he presents material additional evidentiary support to the federal court that was not presented to the state court.’ ” Kunkle v. Dretke, 352 F.3d 980, 988 (5th Cir.2003), cert. denied, 543 U.S. 835, 125 S.Ct. 250, 160 L.Ed.2d 56 (2004) (quoting Graham v. Johnson, 94 F.3d 958, 968 (5th Cir.1996)). See also Moore v. Quarterman, 454 F.3d 484, 491 (5th Cir.2006) (“Evidence is not material for exhaustion purposes if it supplements, but does not fundamentally alter, the claim presented to the state courts.”) (internal quotations and citation omitted) (emphasis in original).

In assessing the exhaustion of Rodriguez's IAC claim as it pertains to his counsel's failure to investigate Rodriguez's brain damage, we look to Rodriguez's diligence at the state habeas level: “[A] failure to develop the factual basis of a claim is not established unless there is a lack of diligence.... Diligence ... depends upon whether [petitioner] made a reasonable attempt, in light of the information available at the time, to investigate and pursue claims in state court....” Williams, 529 U.S. at 430-32, 435, 120 S.Ct. 1479.

Rodriguez claims that he could not present these pieces of evidence in the state habeas proceedings because he was not provided enough resources to conduct his investigation. However, the record shows that the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals granted Rodriguez $4000 for investigative services in connection with his state habeas proceeding.FN6 As noted by the district court, Rodriguez does not explain why he did not obtain at least some neurological or psychological tests with the funds granted him. It is unclear whether Rodriguez exercised sufficient diligence at the state habeas level.

FN6. In total, Rodriguez requested more than $11,000 for investigative services, almost half of which was requested just days before his petition for writ of habeas corpus was due.

However, even if Rodriguez had exhausted his state remedies, his claim for IAC fails. See 28 U.S.C. § 2254(b)(2) (“An application for a writ of habeas corpus may be denied on the merits, notwithstanding the failure of the applicant to exhaust the remedies available in the courts of the State.”) Again, Strickland governs Rodriguez's IAC claim. 466 U.S. 668, 104 S.Ct. 2052, 80 L.Ed.2d 674 (1984). In order to prevail, Rodriguez must meet both the deficiency and prejudice prongs of the Strickland test. Id. at 687, 104 S.Ct. 2052. As discussed, to prevail on the deficiency prong, Rodriguez must demonstrate that counsel's representation fell below an objective standard of reasonableness. Id. In order to prove prejudice, Rodriguez must show a reasonable probability that but for his counsel's deficient performance, the “additional mitigating evidence [was] so compelling that there is a reasonable probability that at least one juror could reasonably have determined that, because of [the defendant's] reduced moral culpability, death was not an appropriate sentence.” Neal v. Puckett, 286 F.3d 230, 241 (5th Cir.2002) (en banc), cert. denied, 537 U.S. 1104, 123 S.Ct. 963, 154 L.Ed.2d 772 (2003); see also Strickland, 466 U.S. at 695, 104 S.Ct. 2052 (“[T]he question is whether there is a reasonable probability that, absent the errors, the sentencer-including an appellate court, to the extent it independently reweighs the evidence-would have concluded that the balance of aggravating and mitigating circumstances did not warrant death.”).

“[C]ounsel has a duty to make reasonable investigations or to make a reasonable decision that makes particular investigations unnecessary.” Strickland, 466 U.S. at 691, 104 S.Ct. 2052 (emphasis added). “[A] particular decision not to investigate must be directly assessed for reasonableness in all the circumstances, applying a heavy measure of deference to counsel's judgments.” Id. “In assessing counsel's investigation, we must conduct an objective review of their performance, measured for reasonableness under prevailing professional norms, which includes a context-dependent consideration of the challenged conduct as seen from counsel's perspective at the time.” Wiggins v. Smith, 539 U.S. 510, 523, 123 S.Ct. 2527, 156 L.Ed.2d 471 (2003) (internal quotation marks and citations omitted); see Rompilla v. Beard, 545 U.S. 374, 381, 125 S.Ct. 2456, 162 L.Ed.2d 360 (2005) (noting that “hindsight is discounted by pegging adequacy to ‘counsel's perspective at the time’ investigative decisions are made”) (quoting Strickland, 466 U.S. at 689, 104 S.Ct. 2052).

The evidence does not support Rodriguez's contention that his trial counsel performed deficiently by not presenting evidence of his brain damage. Trial counsel pursued a mitigation case that described Rodriguez as a changed person. The jury heard abundant evidence lessening Rodriguez's moral culpability and humanizing him. They heard from witnesses who described Rodriguez as having reformed his conduct through religious studies following his incarceration in 1991 and that he had a good disciplinary record while incarcerated. It is a reasonable conclusion, and within trial counsel's purview of professional judgment, that evidence of brain damage to explain Rodriguez's violent behavior would counteract counsel's mitigation strategy. Evidence of Rodriguez's permanent brain damage presents the proverbial double-edged sword: it could bolster the State's case on future dangerousness without significantly reducing, if at all, Rodriguez's moral blameworthiness. See Martinez v. Dretke, 404 F.3d 878, 889 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, --- U.S. ----, 126 S.Ct. 550, 163 L.Ed.2d 466 (2005) (“As we have held, evidence of organic brain injury presents a ‘double-edged’ sword, and deference is accorded to counsel's informed decision to avert harm that may befall the defendant by not submitting evidence of this nature.”). Thus, trial counsel's decision not to introduce evidence of brain damage, given the availability of other, less damaging, mitigating evidence, falls within the bounds of sound trial strategy. See id. at 890.

Rodriguez insists that trial counsel's strategic decision not to introduce evidence of brain damage was unreasonable because trial counsel failed to investigate brain damage. In support of this failure to investigate claim, Rodriguez points to the institutional records of the Orchard Creek Hospital and a neuro-psychologist's opinion that his abusive upbringing, lengthy drug abuse, and use of cocaine damaged his frontal lobes.FN7 The state habeas court found: that trial counsel was aware of the institutional records at Orchard Creek Hospital but decided not to introduce them; that trial counsel objected to the State's attempt to admit the Orchard Creek Hospital records, “in part, because trial counsel did not want the jury informed of a diagnosis of sociopathy for [Rodriguez], and that trial counsel instead offered extensive evidence of [Rodriguez's] character change and his good deeds in prison to persuade the jury that [Rodriguez] would not be a future danger”; and that the institutional records were used by the State for the limited purpose of cross-examining Rodriguez's mother and that the records did not present the jury with a diagnosis of sociopathic behavior. The state habeas court further found that “trial counsel presented extensive testimony ... of [Rodriguez's] home life, his father's abuse, and its affect on [Rodriguez],” and that trial counsel presented evidence of Rodriguez's drug problem, including Rodriguez's anger when he used crack cocaine. Rodriguez has not rebutted the presumption of correctness of the state court's factual findings, and we defer to these findings in ruling on the merits. See 28 U.S.C. § 2254(e)(1).

FN7. Even though it is questionable whether Rodriguez exercised sufficient diligence at the state habeas level to exhaust his failure to investigate claim, we may still deny his writ of habeas corpus on the merits. See 28 U.S.C. § 2254(b)(2) (“An application for a writ of habeas corpus may be denied on the merits, notwithstanding the failure of the applicant to exhaust the remedies available in the courts of the State.”).

Most of the evidence that Rodriguez claims resulted in an unreasonable investigation by trial counsel was actually presented by trial counsel and heard by the jury. As found by the state court, the jury heard evidence of Rodriguez's home life, his father's abuse, his drug abuse, and the fact that he got angry when he used crack cocaine. The jury did not hear evidence of Rodriguez's institutional records at Orchard Creek Hospital. The decision not to introduce those records and to forego further investigation into those records probably was not unreasonable in light of other potentially conflicting mitigating evidence, what trial counsel knew at the time of Rodriguez's 1994 trial, what the State introduced into evidence, and the “heavy measure of deference” owed to counsel's investigative judgments. See Strickland, 466 U.S. at 691, 104 S.Ct. 2052; see also Wiggins, 539 U.S. at 523, 123 S.Ct. 2527. The only remaining evidence that Rodriguez proffers-the opinion of the neuro-psychologist in post-conviction proceedings-is irrelevant to determining the reasonableness of trial counsel's perspective (and thus investigation) in Rodriguez's 1994 trial. See Martinez, 404 F.3d at 886 (stating that testimony of experts and family members not involved in the defendant's 1989 trial proceedings is “irrelevant to counsel's perspective in 1989 ”); see also Rompilla, 545 U.S. at 381, 125 S.Ct. 2456.

Even if counsel's strategies in failing to further investigate or present evidence of brain damage could be described as deficient, they cannot form the basis of a constitutional ineffectiveness assistance of counsel claim because Rodriguez cannot affirmatively demonstrate prejudice. See Strickland, 466 U.S. at 695, 104 S.Ct. 2052. In other words, there is no evidence that trial counsel's strategies, even if they fell below professional norms, prejudiced Rodriguez or “ ‘permeated [his] entire trial with obvious unfairness.’ ” Martinez, 404 F.3d at 890 (quoting United States v. Jones, 287 F.3d 325, 331 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, 537 U.S. 1018, 123 S.Ct. 549, 154 L.Ed.2d 424 (2002)). “In assessing prejudice, we ‘must consider the totality of the evidence before the judge or jury.’ ” Id. (quoting Strickland, 466 U.S. at 695, 104 S.Ct. 2052).

In addition to the mitigation evidence presented by the defense, the jury had before it evidence of Rodriguez's execution of the crime of conviction. The jury heard evidence that on the night of the murder, Rodriguez stole a shotgun and an automatic rifle from his stepfather and was driving around looking for a place to rob. The jury heard that Rodriguez unsuccessfully attempted to rob a gas station, and that he repeatedly fired shots at another driver in a residential neighborhood before shooting Gee and stealing her car. The State produced evidence that Rodriguez burglarized an elementary school in 1990. The State also produced evidence of Rodriguez's Harris County Jail records depicting Rodriguez as an “escape threat” and “aggressive towards staff.” The jury found there was not sufficient mitigating evidence to warrant imposition of a life sentence in lieu of the death sentence. It is not reasonably probable that this outcome would change if, assuming arguendo, his counsel had not erred in investigating or presenting this additional evidence. See Strickland, 466 U.S. at 695, 104 S.Ct. 2052 (“[T]he question is whether there is a reasonable probability that, absent the errors, the sentencer-including an appellate court, to the extent it independently reweighs the evidence-would have concluded that the balance of aggravating and mitigating circumstances did not warrant death.”). The nature of the evidence against Rodriguez advises against a prejudice finding. Cf. Martinez, 404 F.3d at 890.

IV.

For the foregoing reasons, we DENY Rodriguez's request for a COA on all issues, and we AFFIRM the denial of habeas relief on Rodriguez's ineffective assistance of counsel claim for failure to investigate and present evidence of brain damage pertaining to the penalty phase of Rodriguez's trial. COA DENIED; Habeas Relief DENIED; Judgement of the district court is AFFIRMED.