32nd murderer executed in U.S. in 2012

1309th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in South Dakota in 2012

2nd murderer executed in South Dakota since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(32) |

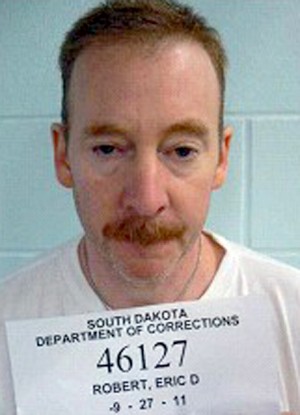

Eric Donald Robert W / M / 49 - 50 |

Ron “R.J.” Johnson OFFICER W / M / 63 |

Summary:

On July 24, 2005, while posing as police officer, Robert pulled over an 18-year-old woman and forced her into the trunk of his car. After driving to a remote location, Robert flees after he hears her talking to someone on her cell phone. In 2006, he was convicted and sentenced to 80 years imprisonment. Maintained in "high security" at the South Dakota State Penitentiary after a lock is found cut in his working area, Robert and accomplice Rodney Berget attempt an escape, beating 62 year old corrections officer Ronald “R.J.” Johnson with a pipe and covering his head in plastic wrap, killing him. They take his uniform, but are spotted and captured before they can escape. Robert pled guilty and waived all appeals. Accomplice Berget also pleaded guilty and was sentenced to death. Accomplice Michael Nordman received a life sentence for providing materials used in the slaying.

Berget &

Nordman

Nordman

Citations:

State v. Robert, 820 N.W.2d 136 (S.D. 2012). (Direct Appeal)

Final/Special Meal:

Robert fasted in the 40 hours before his execution, consuming his last meal on Saturday: Moose Tracks ice cream.

Final Words:

“In the name of justice and liberty and mercy, I authorize and forgive Warden Douglas Weber to execute me for my crimes. It is done.”

Internet Sources:

South Dakota Department of Corrections

Office of Gov. Dennis Daugaard500 E. Capitol Ave.

Pierre,S.D.57501

www.sd.gov

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Monday, Oct. 15, 2012

“This is a sad day for South Dakota. Executions are rare in our state, and they are warranted only with extreme forethought and certainty. In this case, Eric Robert admitted to his crime and requested that his punishment not be delayed. I hope this brings closure to “RJ” Johnson’s family and all those who loved him. I also commend Warden Weber and others in the state Department of Corrections who planned this very difficult task in a professional and careful manner.”

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: October 12, 2012

Execution Date, Time Set For Inmate Eric Robert

PIERRE, S.D. - In accordance with South Dakota Codified Law 23A-27A-17, Doug Weber, Director of Prison Operations and Warden of the South Dakota State Penitentiary, has set the date and time for the execution of inmate Eric Robert as Monday, Oct. 15, 2012, at about 10 p.m. CDT.

State law allows judges in capital punishment cases to appoint a week for the executions to occur. The exact date and time of the execution is left to the warden's discretion. The warden is required by state law to publicly announce the scheduled day and hour of the execution not less than 48 hours prior to the execution.

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Friday, Aug. 24, 2012

Warrant of Execution For Eric Robert Issued

PIERRE, S.D - Attorney General Marty Jackley announced today that the warrant of execution for Eric Donald Robert has been issued by Second Circuit Court Judge Bradley Zell. Robert is scheduled to be executed between the hours of 12:01 a.m. and 11:59 p.m. during the week of Sunday, Oct. 14, 2012, through Saturday, Oct. 20, 2012, inclusive, at a specific time and date to be selected by the warden of the State Penitentiary. Pursuant to South Dakota law, the warden will announce to the public the scheduled day and hour within 48 hours of the execution.

South Dakota law further provides that for the execution, the warden is to request the presence of the attorney general, the trial judge who oversaw the conviction or the judge’s successor, the state’s attorney and sheriff of the county where the crime was committed, representatives of the victims, at least one member of the media, and a number of reputable adult citizens to be determined by the warden.

"Execution: South Dakota delivers Eric Robert his death wish," by Steve Young. (2:08 AM, Oct 16, 2012)

Eric Robert, whose botched attempt for freedom from the state penitentiary resulted in the murder of a prison guard, finally escaped Monday night from the bitter life behind bars he loathed — this time through the execution chamber. Robert, 50, died by lethal injection at 10:24 p.m. for his role in the April 12, 2011, murder of officer Ron “R.J.” Johnson on the same penitentiary grounds where the inmate was put to death Monday.

Asked by Warden Doug Weber before the execution if he had any last statement, Robert began by saying, “In the name of justice and liberty and mercy, I authorize and forgive Warden Douglas Weber to execute me for my crimes. It is done.” Robert’s lawyer, Mark Kadi of Sioux Falls, said it was important for Robert to forgive the warden. “It may seem like a minor, odd point for everybody else,” Kadi said. “But from the perspective of a man who’s got seconds left, the last thing he wanted to do was forgive the individual who was causing the execution, causing his death.”

Speaking afterward in the prison training academy that was renamed for her husband on the one-year anniversary of his death, Johnson’s widow, Lynette, said the family understands that Robert’s death won’t bring their loved one back. Still, “we, Ron’s children and I, want everyone please, do not forget how kind, how wonderful and caring Ron Johnson is,” Lynette Johnson said. “We know this execution tonight is not going to bring back my husband to me. It’s not going to bring our children’s father back to them. ... our six grandchildren’s ‘Papa’ to them. But we know that the employees of the Department of Corrections and the public in general will be just a little bit safer now.”

Corrections spokesman Michael Winder said Robert was removed from his holding cell at 9:31 p.m. and placed on the table in the execution chamber at 9:32 p.m. The first intravenous line was started in his right arm five minutes later, and the second IV line, in his left arm, at 9:41 p.m. After the witnesses were escorted to the viewing rooms, Weber ordered the curtains opened at 9:59 p.m. Robert gave his last statement at 10:01, and the injections were completed at 10:04. Media witness Dave Kolpack of The Associated Press said Robert appeared to be clearing his throat as the lethal drug was being administered. “He began to make some heavy gasps, and then started snorting. That lasted about 30 seconds,” Kolpack said.

Dressed in a white T-shirt and orange prison pants, with a sheet pulled up to about the middle of his chest, Robert appeared to stop moving at about 10:03 p.m., said John Hult of the Argus Leader, the second media witness to the execution. After the clearing of his throat, “there was no movement,” Hult said. “I didn’t see his chest move at all after that.” Coroners checked for a pulse in his neck and chest for several minutes before he was finally declared dead. Hult said the inmate’s eyes remained open the entire time, even after an assistant coroner tried to close them. By the time he was declared dead, his skin color had turned purple, witnesses said.

One controversial drug

Unnamed correctional officers on the execution team administered a single drug, pentobarbital — a powerful barbituate that stopped Robert’s respiration and created blood pressure changes that caused his heart to give out. Attorney General Marty Jackley said he never considered bringing in executioners from outside South Dakota’s penitentiary system, even though the murdered guard was one of their own. “From everything that I witnessed, Corrections staff were exceptionally professional,” the attorney general said. “They carried out a humane sentence. I saw no need to have another entity.”

The protocol for Robert’s execution was different from that used five years ago, when Elijah Page was put to death for his role in the 2000 murder of Chester Allan Poage near Spearfish. Back then, South Dakota used a three-drug procedure that started with an injection of sodium thiopental to knock him unconscious and numb the pain of the other two drugs — pancuronium bromide to collapse the lungs and potassium chloride to stop the heart. But a shortage of those execution drugs in recent years led to controversy and delays nationwide, and prompted South Dakota and states such as Georgia, Ohio, Arizona, Idaho and Texas to make the switch to the single drug. After South Dakota decided on pentobarbital, federally appointed public defenders for death row inmate Donald Moeller challenged the quality of the chosen barbituate, saying its plan to mix the drug from powder posed a serious risk of contamination that could lead to pain and suffering.

But Moeller, sentenced to die for the 1990 rape and murder of 9-year-old Rebecca O’Connell, told a judge Oct. 4 that he had no interest in pursuing that challenge and delaying his scheduled execution two weeks from now. And Robert had long nixed any appeals on his behalf, saying he could kill again if left to a life in prison. In a prepared statement, Gov. Dennis Daugaard called Monday’s execution “a sad day for South Dakota.” “Executions are rare in our state, and they are warranted only with extreme forethought and certainty,” the governor said.

'Calm and reserved'

On Saturday evening, Robert consumed his last meal — Moose Tracks ice cream. Kadi said Robert chose to fast during his last 40 hours before his execution. Kadi said Robert considered the fast to be religious in nature and a metaphor for the 40-day fast of Christ in the Bible. From 6:30 p.m. to 8 p.m. Monday, the inmate “was actually calm and reserved,” Kadi said, adding that the actual execution itself “was so antiseptic and peaceful that it masks what was actually being done to the person.”

Robert never denied his role in the escape attempt that resulted in the death of Johnson on April 12, 2011 — the correctional officer’s 63rd birthday. From the beginning, Robert took responsibility for the crime, asking for and receiving the death penalty and eschewing all appeals — thus the relative quickness in which he was adjudicated and executed. Johnson, a 20-year veteran at the prison, had volunteered for a shift in the Pheasantland Industries building on the penitentiary grounds the morning that Robert and fellow inmate Rodney Berget walked into the building with a load of laundry. Even though both inmates were classified as maximum security risks, their jobs afforded them the freedom of movement.

Each man testified that they had hid and waited for Johnson, then snuck up on him, struck him in the head with a metal pipe, then wrapped his head in plastic to stop him from screaming. Robert put on Johnson’s uniform. Berget climbed into a box atop a wheeled cart. They never made it out of the penitentiary before being caught. A third inmate, Michael Nordman, 47, was given a life sentence for providing materials used in the slaying.

Execution: Key dates in Eric Robert's life

May 31, 1962: Born in Massachusetts, later moves to Hayward, Wis., with mother and younger sister

1980: Graduates 18th in his class at Hayward High School

1987: Graduates from University of Wisconsin-Superior

1988: Working as chemist for Murphy Oil in Superior

1992: Returns to Hayward, begins coaching youth baseball, later joins volunteer EMT service

1994-99: Works in Cable, Wisconsin for wastewater treatment plant, builds house in Drummond.

1999-2000: Works for Bayfield County, Wis., Zoning Office

2000-2004: First manages, then consults for, wastewater treatment plant in Superior

2005: Moves to Piedmont, S.D., to help a friend

July 24, 2005: Posing as police officer, pulls over and kidnaps an 18-year-old woman.

Jan. 3, 2006: Sentenced to 80 years for kidnapping

2007: Classified as “high security” at South Dakota State Penitentiary

2009: Attempted sentence reduction fails, Robert denied transfer to prison closer to Wisconsin

April 12, 2011: With Rodney Berget, kills corrections officer during an escape attempt.

Sept. 16, 2011: Pleads guilty to frst-degree murder

Oct. 19, 2011: Asks for a death sentence from Judge Bradley Zell

Oct. 20, 2011: Zell sentences Robert to death

Aug. 2012: South Dakota Supreme Court upholds death sentence.

Oct. 12, 2012: Warden Doug Weber announces that Robert will be put to death at 10 p.m. Oct. 15

Oct. 15, 2012: 9:31 p.m. Robert removed from his holding cell

9:32 p.m. Robert transferred to the execution table

9:35 p.m. Restraints are secured

9:37 p.m. First IV started in the right arm

9:41 p.m. Second IV is started

9:46 p.m. Staff begins to escort witnesses to the viewing rooms

9:59 p.m. With all witnesses present, warden orders the curtains open

10 p.m. Secretary of Corrections informs warden he is clear to proceed with execution

10:01 p.m. Last statement: “It is done”

10:04 p.m. Injections are completed

10:24 p.m. Time of death

"Eric Robert: From model citizen to death row; Man headed to death chamber tonight had seemingly normal, productive life before turning to crime," by John Hult. (October 15, 2012)

SIOUX FALLS — Eric Robert’s life bears little resemblance to that of his peers on death row. Most condemned killers have troubling personal stories and long criminal histories. Donald Moeller was beaten, demeaned and made to watch his biological mother’s drug use and sexual behavior. Elijah Page, executed in 2007, moved from house to house with substance-abusing parents then bounced from foster home to foster home in several states. Rodney Berget suffered with an alcoholic father and abuse, and was first sent to the adult prison system at age 15. His brother, Roger, was executed in 2003 in Oklahoma, eight years before Rodney Berget and Robert would commit a capital crime in the murder of Corrections Officer Ron Johnson. Robert’s life looked nothing like Berget’s. He will be put to death at 10 p.m. today.

Robert was the child of a single mother who helped raise his younger sister in his home state of Wisconsin. He had a stellar academic record, put himself through college and had a successful career in wastewater treatment. He was an emergency medical technician and frequent community volunteer who once helped erect a monument to a murdered sheriff. He grew close to his longest-term love interest through her son, whom Robert coached on a Little League team.

In 2005, before he was sentenced to 80 years in prison for a Meade County kidnapping, his sister told the judge that her brother “has done more good in his life than many people in this world.” This week, the state of South Dakota intends to put Robert to death by lethal injection for the brutal, premeditated killing of Johnson on April 12, 2011.

The rage that fueled the killing was a measure of how far he’d fallen from the life he once had. Robert said so himself in court one year ago. He’d refused to let his lawyer mention his good deeds. “To be honest with you, the good acts that I’ve done in my life were not mentioned here, because they are irrelevant to these proceedings,” Robert said. “That person who did good things no longer exists.”

Last week, through his lawyer Mark Kadi, Robert reiterated his reasoning for staying quiet about his prior kind acts during sentencing for the Johnson murder. “My client feels that none of the good things he’s done justify the killing of Ron Johnson,” Kadi said.

Early life

Eric Robert was born May 31, 1962, in Massachusetts. His father was gone by the time he was 6 months old. Robert, his mother and younger sister moved to Hayward, Wis., when he still was young. His sister, Jill Stalter, declined to comment for this story but testified on her brother’s behalf in 2005.

She said then that Robert was the father figure in their house as their mother worked three jobs and studied to earn a college degree. “My brother took care of everything. He took out the trash, he made sure dinner was on the table, he even did grocery shopping. He got me my first dog. He did everything. He even shoveled snow, and in Hayward, it’s a lot of snow,” Stalter said. “He put himself through college by working weekends and during summer breaks. He didn’t take a penny from my mother because she was putting herself through college.”

He was a good student, as well, graduating 18th in his class at Hayward High School in 1980. He returned to Hayward after earning a biology degree with a chemistry minor at the University of Wisconsin-Superior. In 2000, he applied for a job as the wastewater treatment supervisor for the city of Superior. On his job application, released as part of a records request by the Argus Leader, Robert wrote that he hadn’t missed a day of work in 10 years. He got along well with co-workers. Frog Prell, the city attorney, started work for the city in 2000, just a few months after Robert, whom family and friends knew as “Ranger.”

Robert used to drop by the office to joke around, quiz Prell about small towns in Wyoming, which is Prell’s home state. The short interactions left an impression on Prell, who didn’t know Robert was on death row until the records request came across his desk this month. “If you’d have asked me what I thought about Eric Robert before this, I’d have said he seemed like a pretty cool guy,” Prell said. Dan Romans, the wastewater administrator for Superior, called Robert a “natural-born leader” who accomplished more in 18 months on the job than others had for decades.

‘Aggressive, mean’

Robert eventually lost his job in Superior, though, because he failed to comply with a city residence requirement, but he continued to consult with the city afterward. He was living in a home in the rural community of Drummond, more than an hour southeast of Superior.

It was in Hayward, almost a decade before, where he met the woman with whom he’d later build the house in Drummond. That woman, who testified at Robert’s pre-sentence hearing last year in Sioux Falls but declined to comment for this story, said there was an undercurrent of anger in him even then — one most people didn’t see. “He was an aggressive, mean person who didn’t like other people and had to be in control,” she said the woman, whom the Argus Leader is not identifying because she is a victim. She’d gone to high school with Robert but didn’t know him well at the time. They got reacquainted in 1992, when he was coaching her son’s baseball team. Robert soon was living with the woman and her two children.

“We got along fine at first,” she said, but then “he showed me his true colors.” She recounted three specific incidents in court from their decade-long romance. They rented an apartment in Cable, Wis., as they built their house, she said. One day, as they sat on the couch together, Robert backhanded her over an offhand remark. She hit him back, she said, then recoiled when she realized that he was sure to retaliate. “He punched me in the mouth so hard it pushed my bottom teeth through my lip,” she said.

Robert, who knew most of the employees in the local ER through his work as an EMT, told the doctors and nurses she’d slipped on icy steps while carrying in groceries. He had similar explanation for her appearance at the ER with a broken foot years later. She called police on him after a separation, when he showed up at her house drunk and started a fight that ended with him pulling her around the yard by her hair. She dropped the charges for fear he’d hurt her again. She lived with a lot, she told Judge Zell. He’d force her to come to bed without clothing and beat her until she relented and submitted to sex. “I told myself because I rolled over and said ‘fine’ that it wasn’t rape,” she said. Another former girlfriend accused Robert of rape in 2002 in Brule County but never filed charges. She was granted a protection order against Robert, however, after telling a judge there that Robert had held her against her will after a day of searching for apartments in Chamberlain.

80-year sentence

The crime that would land Robert in the penitentiary in South Dakota took place in 2005, a few months after he moved to Piedmont to help a friend with her business. On July 24, 2005, Robert followed an 18-year-old woman on a rural road near Black Hawk and turned on his pickup’s spotlights to pull her over about 2 a.m. In court one year ago in Sioux Falls, the victim recounted her story. She said Robert told her he was an undercover police officer and asked her to perform field sobriety tests. “He didn’t have any form of identification; he had maybe just a T-shirt on and jeans. Had some facial hair, an unshaven look,” she said.

She was suspicious, she said, but went along with it when Robert asked her to empty out the trunk of her car. That’s when Robert scooped her up and stuffed her in the trunk. “I remember hearing the vehicle that was behind my car leaving, so I thought he had just left me there,” she said. She had a cellphone and called a friend to tell them what had happened. Meanwhile, Robert drove his truck to a lot just down the road, then returned to the location of the stop and drove her car to the lot. Robert disappeared shortly after parking her car, as the victim frantically described her situation to the Pennington County Sheriff’s department.

When detectives found Robert and his pickup days later, he no longer matched the description of the suspect. He’d shaved his head and face and initially denied any involvement. In the back of his truck, detectives found a bed, an ax, rope and pornography. He eventually admitted to pulling the victim over and was arrested. Prosecutors said the items were evidence that Robert planned to rape the victim, but Robert denied that.

The friend he was working for in Piedmont said “Ranger” would sleep in his truck to avoid hotel fees. She said he’d never shown any interest in young girls. At his sentence hearing in 2005, she said he’d been working for her all summer for no pay, and that she couldn’t believe the allegations against him at first. “It’s unbelievable that he would do that, or that he did that. It’s nothing of the man I know. He was incapable of doing that,” Cheryl Williamson said.

Another friend of Robert, Bob Lang, an EMT from Cable, Wis., also testified on his behalf. Robert volunteered his time for the ambulance service, he said, but also volunteered around the region in other ways. When a former Bayfield County Sheriff Richard Parquette was killed in a domestic dispute, Lang decided that the ambulance service ought to erect a memorial to him. Robert, who met Lang shortly after the sheriff’s death and never knew Parquette personally, put in hours of time raising funds for the memorial. “I didn’t understand it,” Lang said. “He didn’t know Officer Parquette. He didn’t really know me at the time. He just said he wanted to do what was right.”

Lang and others did say Robert could be very aggressive when drinking alcohol, but they also said he had given up drinking alcohol on his own as a way to keep a lid on the aggression. Robert was given an 80-year prison sentence, based in part on his suspected intentions. In pronouncing sentence, Judge Warren Johnson said it was too difficult to square Robert’s life in northern Wisconsin with the man who committed the Meade County crime. “It certainly sounds like the Wisconsin Eric Robert is a totally different person from the South Dakota Eric Robert,” Johnson said. “It’s the South Dakota Eric Robert I’m dealing with today.”

Prison life

Prison further hardened Robert. He spent years battling the DOC and court system over a variety of issues. He successfully fought an effort by the DOC to classify him as an unconvicted sex offender based on the allegations made by the women he’d known in Wisconsin, Chamberlain and his victim in Piedmont. In 2007, he was accused of attempting to escape by tampering with a lock on the door of a shower room where he worked. He argued unsuccessfully that he’d been set up by other inmates. Two other appeals consumed him during his incarceration, according to testimony from DOC employees at his sentencing last year. He first fought for a shot at a sentence reduction. When that failed in 2009, he asked for a transfer to a facility in Wisconsin, so he could be closer to his mother. That failed, as well.

Soon thereafter, Robert’s rage metastasized until he came to view himself as a soldier in a “war” against his oppressors. “On April 12, 2011, RJ (Johnson) became a victim in Robert’s war,” Judge Brad Zell wrote in his ruling on the death penalty. “As Robert stated in court, anyone who stood in his way as an oppressor would have died on that day.” Johnson wasn’t even scheduled to work that day, which was his 63rd birthday. He’d agreed to come in to cover a shift for a co-worker, who’d called in sick.

The 20-year veteran in the prison showed up and took up his post in the Pheasantland Industries building that morning at 7:30. Three hours later, Robert and his co-defendant, Rodney Berget, walked into the building with a load of laundry. Even though both men were classified as maximum security risks, their jobs afforded them freedom of movement. Each man testified that they hid and waited for Johnson, then snuck up on him, bashed him in the head with a metal pipe then wrapped his head in plastic to stop him from screaming. Robert put on Johnson’s uniform. Berget climbed into a box atop a wheeled cart.

Robert pushed the cart through one of the double doors in the sally port at the prison’s west gate, where he was intercepted and questioned by Officer Matthew Freeburg. When Freeburg asked the officer in the control booth to call for backup, Berget sprang from the box and both inmates began to beat the officer as a security alert went out through the penitentiary. In September, when Robert pleaded guilty to first-degree murder, his lawyer, Mark Kadi, told Judge Zell that his client wanted to plead guilty the next day.

"South Dakota Executes Inmate Who Killed Prison Guard," by Dave Kolpack and Kristi Eaton. (10/16/12)

SIOUX FALLS, S.D. — A South Dakota man who beat a prison guard with a pipe and covered his head in plastic wrap to kill him during a failed escape attempt was put to death Monday, in the state's first execution since 2007. Eric Robert, 50, received lethal injection and was pronounced dead at the state penitentiary in Sioux Falls at 10:24 p.m. He is the first South Dakota inmate to die under the state's new single-drug lethal injection method, and only the 17th person to be executed in the state or Dakota Territory since 1877.

Robert had no expression on his face. Asked if he had a last statement, Robert said: "In the name of justice and liberty and mercy, I authorize and forgive Warden Douglas Weber to execute me for the crimes. It is done." As the drug was administered, the clean-shaven Robert, wearing orange inmate pants with a white blanket wrapped around his upper body, appeared to be clearing his throat and then began gasping heavily. He then snored for about 30 seconds. His eyes remained opened throughout and his skin turned pale, eventually gaining a purplish hue.

Robert was put to death in the same prison where he killed guard Ronald "RJ" Johnson during an escape attempt on April 12, 2011. Robert was serving an 80-year sentence on a kidnapping conviction when he tried to break out with fellow inmate Rodney Berget, 50. Johnson's widow, Lynette, said after the execution that she knows Robert's death will not bring back her husband, her children's father or her grandchildren's grandfather. "But we do know that the employees of the Department of Corrections and the public in general will be just a little bit safer now," Lynette Johnson said. "We need to have more attention and focus on the safety of all of the correctional officers in the state of South Dakota. Ron, none of you will ever know how great he is and is missed. We stand proud for Ron." Lynette Johnson, her two children and their spouses all witnessed the execution. No one from Robert's family was in attendance.

Robert ate his last meal of ice cream with his lawyer, Mark Kadi, on Saturday night before fasting for 40 hours for religious reasons. After the execution, Kadi said the execution was very "orderly and polished." "The problem was it was too orderly. It was so antiseptic and peaceful that it masked what was being done to the person," Kadi said. "If more people were able to see the events, there would be fewer of them."

Johnson was working alone the morning of his death – also his 63rd birthday – in a part of the prison known as Pheasantland Industries, where inmates work on upholstery, signs, custom furniture and other projects. Authorities said the inmates beat Johnson with a pipe, covered his head in plastic wrap and left his body on the floor. Robert then put on Johnson's pants, hat and jacket and approached the prison's west gate. With his head down, he pushed a cart loaded with two boxes. Berget was hidden in one of the boxes, according to a report filed by a prison worker after the slaying. Other guards became suspicious as the men got closer to the gate. When confronted, Robert beat one guard; other guards quickly arrived and detained both inmates.

Months later, Robert told a judge his only regret was that he hadn't killed more guards. He pleaded guilty to Johnson's slaying and asked to be sentenced to death, telling a judge last October that he would otherwise kill again. He never appealed his sentence and even tried to bypass a mandatory state review in hopes of expediting his death. Berget also has pleaded guilty in the killing but has appealed his death sentence. A third inmate, Michael Nordman, 47, was given a life sentence for providing materials used in the slaying.

Robert's execution could be the first of two in as many weeks. Donald Moeller is scheduled to be put to death the week of Oct. 28 for the 1990 kidnapping, rape and murder of a 9-year-old girl. Robert had been on death row only for about a year, Moeller has been there for more than two decades. Only three other inmates currently are on the state's death row.

South Dakota's last execution before Monday took place in 2007, and that was the first in the state for 60 years. "You have few people on death row, few executions, and then you have this coincidence of cases coming all at once," said Richard Dieter, executive director of the nonprofit Death Penalty Information Center. "When people waive appeals, their cases start to move more quickly."

"Eric Robert Writes Letter to AG Marty Jackley," by Jennifer Hudspeth. (October 16, 2012 9:21 PM)

Just one day following his execution, KDLT News has learned Eric Robert wrote a 3-page letter to Attorney General Marty Jackley. Robert was put to death on Monday by lethal injection for the murder of Correctional Officer Ronald Johnson. In the handwritten note, Robert asks Jackley to take action during the next legislative session. Robert states in the letter he has an idea that could make sure victims and their families get “swift justice.”

In a letter dated October 8, 2012; exactly one week before he would die by lethal injection, Robert begins by saying “thank you.” In some of his final words, he commends the prosecutor for his professionalism during the case and says they agreed on the main focus; his actions deserved the death penalty. Robert goes on to write, “I do not want or desire to die, instead I deserve to die; this I have always stated.” As the letter continues, Robert’s thoughts are poured out on paper.

He tells Jackley he does not have Jackley’s expertise of the law, but says as a “layman,” he feels changes need to be made to the death penalty statute. In the letter Robert talks about the mandatory review of the case which was conducted by the Supreme Court. The letter states he was not happy with how long the process took, a sentiment he shares with his attorney Mark Kadi. "There were times I think he was a little tense when the Supreme Court was doing things to delay things for sentencing reasons. But then once that was over, he was back to being calm, cool, and collective," said Mark Kadi, Robert's attorney.

Robert did not appeal his sentence, and in the letter he says he felt his review was handled in the same way as an appeal. Instead Robert proposes new language he feels would speed up the process. Robert concludes his letter by writing, “It’s not about me or any future killers, it is about ensuring that in contested cases that the victims and their families get their intended and needed swift justice. Perhaps you could allow Lynette Johnson to propose this ‘R.J. Johnson Amendment’ to the legislature.” He signed “Sincerely, Eric Robert.” Jackley says because the letter is the thought process of Eric Robert, he does not plan to comment any further.

Yankton Daily Press and Dakotan

"Our View: The Death Penalty And The Moral Fog." (Published: Wednesday, October 17, 2012 1:06 AM CDT)Deep down, it’s hard for many of us to know what to think. The execution Monday night of convicted murderer Eric Robert brought a quick end to what is usually an interminable procession of appeals. Robert was convicted, along with another prisoner, of killing prison guard Ronald Johnson during an escape attempt from the South Dakota State Penitentiary just last year. Robert never sought to avoid the fate that our system of justice said he had coming to him, declaring he would kill again if he wasn’t put to death. On Monday night, he met that fate — an eye for an eye, according to Exodus 21:24, not to mention state codified law.

But the morality of such matters is never so comfortably clear for some people. That was demonstrated in vigils of protest such as one conducted in Yankton Monday night while a lethal injection was swimming through Robert’s veins in Sioux Falls. The main counter-argument the protesters put forth was simple: One of the Ten Commandments that our Christian society professes to revere declares: Thou shall not kill. And yet, the state carried out a killing to atone for a killing, as a judgment on another human being.

There is no question that Robert’s crime was abhorrent. He deserved to be punished for his action; no one argued otherwise. And Robert’s willingness to die was clear: In a letter he sent to Attorney General Marty Jackley earlier this month, but not made public until Tuesday, Robert wrote, “... my actions deserved the penalty of death.” He added, “I do not want to or desire to die, instead I deserve to die. ... The victim’s family deserves their justice swiftly to begin their healing.” That’s a powerful argument, albeit from a flawed source.

But opponents of the death penalty say it is not the place of a government to dictate life and death on such terms, and they viewed the state’s execution of Robert as assisting with his suicide. Also, the death penalty removes any hope for atonement — not forgiveness, by any means, but an opportunity for a soul, if you will, to turn itself around and reclaim some measure of lost goodness.

This is an extraordinary dialogue of conscience that will probably never settle anything. There will be those people who will always believe that murderers deserve to die. And if you do believe that, Robert certainly got what he deserved. And there will always be people who will proclaim that the state must not, as they see it, commit the very same crime that we condemn others for doing. It is a genuine dilemma for some people.

Meanwhile, we must also recognize that there are other problems with capital punishment that lurk in the moral fog. The danger of executing an innocent person is always a possibility. Thanks to improved DNA techniques, at least 15 people in this country who were condemned to death for crimes have been exonerated since 1992. There have also been a handful of individuals who have been executed and were later believed to have been innocent. That is unforgivable — and uncorrectable.

Perhaps, then, what is important is that the dialogue of conscience continues with each case, as it seems to do in South Dakota, where executions are rare. The last thing we can afford to do is to take these matters for granted and allow the use of the death penalty to become an ordinary thing, as opposed to an extraordinary punishment.

The debate may indeed never be settled, at least in the U.S. — although 51 percent of the countries on the planet have settled it and abolished the practice, according to the United Nations. But perhaps the debate can serve a purpose, and it may one day change public opinion here on the subject. Until then, we can only ask the questions — of our society and ourselves. Because all things considered, it’s truly hard to know what to think.

"Eric Robert executed in South Dakota." (Tue Oct 16, 2012 2:21am EDT)

(Reuters) - South Dakota on Monday executed an inmate convicted of beating a prison guard to death during a failed escape attempt, in the state's first execution in five years. Eric Robert, 50, was put to death by lethal injection at the state prison in Sioux Falls. He was pronounced dead at 10:24 p.m. (11:24 p.m. EDT), the corrections department said. Robert's execution came 18 months after authorities say he and fellow inmate Rodney Berget beat guard Ronald Johnson to death with a lead pipe and attacked other officers in an escape attempt on Johnson's birthday in April 2011.

Johnson's widow, Lynette Johnson, witnessed the execution. She said afterward that her family did not want people to forget "how kind, how wonderful and caring" her husband was. "We know this execution tonight is not going to bring back my husband to me, it is not going to bring our children's father back to them, our six grandchildren's 'papa' back to them but we do know that the employees of the department of corrections and the public in general will be just a little bit safer now," she said.

Robert pleaded guilty to first-degree murder in the killing of Johnson, waived a jury for sentencing, told the judge during sentencing that he would kill again if he did not receive the death penalty and opposed efforts to halt his execution. Corrections officials said his last words were: "In the name of justice and liberty and mercy I authorize and forgive Warden Douglas Weber to execute me for my crimes. It is done."

According to court records, Robert was five years into an 80-year sentence for kidnapping a young woman when he and Berget planned their escape from the prison in Sioux Falls. The men entered an area of the prison they were not allowed to be in and attacked Johnson with a lead pipe. Robert then put on the guard's pants, shoes, jacket and baseball cap and Berget hid on a cart, court documents show. Robert tried to push the cart with Berget inside through a prison exit, but was challenged by an officer, setting off a fight with several guards before they surrendered, they show.

Robert had a last meal of ice cream on Saturday night, then fasted, said attorney Mark Kadi.

Executions have been rare in South Dakota - there have only been two since 1913. "In this case, Eric Robert admitted to his crime and requested that his punishment not be delayed," South Dakota Governor Dennis Daugaard said in a statement. But the state might have a second execution in October. South Dakota is scheduled to execute Donald Moeller for the 1990 rape and murder of 9-year-old Becky O'Connell the week of October 28 to November 3. The prison warden schedules the specific date and time.

Before Robert's execution, 31 prisoners had been executed in the United States in 2012, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

"S. Dakota executes inmate who killed prison guard." (AP Tuesday, October 16, 2012 9:39 am)

SIOUX FALLS, S.D. (AP) — A South Dakota man who beat a prison guard with a pipe and covered his head in plastic wrap to kill him during a failed escape attempt was put to death Monday, in the state’s first execution since 2007. Eric Robert, 50, received lethal injection and was pronounced dead at the state penitentiary in Sioux Falls. He is the first South Dakota inmate to die under the state’s new single-drug lethal injection method, and only the 17th person to be executed in the state or Dakota Territory since 1877.

Robert was put to death in the same prison where he killed guard Ronald “RJ” Johnson during an escape attempt on April 12, 2011. Robert was serving an 80-year sentence on a kidnapping conviction when he tried to break out with fellow inmate Rodney Berget, 50.

Johnson was working alone the morning of his death — also his 63rd birthday — in a part of the prison known as Pheasantland Industries, where inmates work on upholstery, signs, custom furniture and other projects. Authorities said the inmates beat Johnson with a pipe, covered his head in plastic wrap and left his body on the floor. Robert then put on Johnson’s pants, hat and jacket and approached the prison’s west gate. With his head down, he pushed a cart loaded with two boxes. Berget was hidden in one of the boxes, according to a report filed by a prison worker after the slaying. Other guards became suspicious as the men got closer to the gate. When confronted, Robert beat one guard; other guards quickly arrived and detained both inmates.

Months later, Robert told a judge his only regret was that he hadn’t killed more guards. He pleaded guilty to Johnson’s slaying and asked to be sentenced to death, telling a judge last October that he would otherwise kill again. He never appealed his sentence and even tried to bypass a mandatory state review in hopes of expediting his death. Berget also has pleaded guilty in the killing, but has appealed his death sentence. A third inmate, Michael Nordman, 47, was given a life sentence for providing materials used in the slaying.

Robert’s execution could be the first of two in as many weeks. Donald Moeller is scheduled to be put to death the week of Oct. 28 for the 1990 kidnapping, rape and murder of a 9-year-old girl. Robert had been on death row only for about a year, Moeller has been there for more than two decades. Only three other inmates currently are on the state’s death row.

South Dakota’s last execution before Monday took place in 2007, and that was the first in the state for 60 years. “You have few people on death row, few executions, and then you have this coincidence of cases coming all at once,” said Richard Dieter, executive director of the nonprofit Death Penalty Information Center. “When people waive appeals, their cases start to move more quickly.”

"South Dakota murderer executed by lethal injection for beating to death prison guard with pipe during botched escape. (Associated Press UPDATED: 23:49 EST, 15 October 2012)

A South Dakota man who beat a prison guard with a pipe and covered his head in plastic wrap to kill him during a failed escape attempt was put to death on Monday, in the state's first execution since 2007. Eric Robert, 50, received lethal injection and was pronounced dead at the state penitentiary in Sioux Falls at 10.24 pm. He is the first South Dakota inmate to die under the state's new single-drug lethal injection method, and only the 17th person to be executed in the state or Dakota Territory since 1877.

Robert had no expression on his face. Asked by the Warden if he had a last statement, Robert said: 'In the name of justice and liberty and mercy, I authorize and forgive Warden Douglas Weber to execute me for the crimes. It is done.' As the drug was administered, the clean-shaven Robert, wearing orange inmate pants with a white blanket wrapped around his upper body, appeared to be clearing his throat and then began to make heavy gasps. He started snoring for about 30 seconds. His eyes remained opened throughout and his skin turned pale, eventually gaining a purplish hue.

Robert was put to death in the same prison where he killed guard Ronald 'RJ' Johnson during an escape attempt on April 12, 2011. Robert was serving an 80-year sentence on a kidnapping conviction when he tried to break out with fellow inmate Rodney Berget, 50.

Johnson was working alone the morning of his death - also his 63rd birthday - in a part of the prison known as Pheasantland Industries, where inmates work on upholstery, signs, custom furniture and other projects. Authorities said the inmates beat Johnson with a pipe, covered his head in plastic wrap and left his body on the floor. Robert then put on Johnson's pants, hat and jacket and approached the prison's west gate. With his head down, he pushed a cart loaded with two boxes. Berget was hidden in one of the boxes, according to a report filed by a prison worker after the slaying. Other guards became suspicious as the men got closer to the gate. When confronted, Robert beat one guard; other guards quickly arrived and detained both inmates.

Months later, Robert told a judge his only regret was that he hadn't killed more guards. He pleaded guilty to Johnson's slaying and asked to be sentenced to death, telling a judge last October that he would otherwise kill again. He never appealed his sentence and even tried to bypass a mandatory state review in hopes of expediting his death. Michael Nordman, 47, was given a life sentence for providing materials used in the murder of Ronald Johnson Berget also has pleaded guilty in the killing but has appealed his death sentence. A third inmate, Michael Nordman, 47, was given a life sentence for providing materials used in the slaying.

Robert's execution could be the first of two in as many weeks. Donald Moeller is scheduled to be put to death the week of October 28 for the 1990 kidnapping, rape and murder of a nine-year-old girl.

Only three other inmates currently are on the state's death row. South Dakota's last execution before Monday took place in 2007, and that was the first in the state for 60 years. 'You have few people on death row, few executions, and then you have this coincidence of cases coming all at once,' said Richard Dieter, executive director of the nonprofit Death Penalty Information Center. 'When people waive appeals, their cases start to move more quickly.'

For religious reasons, Roberts spent his final 40 hours fasting and as a result his last meal was on Saturday night when he ate Moose Track ice cream – vanilla ice cream with peanut butter cups and Moose Track Fudge. According to his lawyer, Mark Kadi, the fast is religious in nature with 40 hours serving as a metaphor for the 40-day fast of Christ in the Bible.

Opponents of the death penalty held a vigil outside the prison at 8pm. Any last-minute appeal or stay of execution is unlikely, as Gov. Dennis Daugaard announced last week that he would not intervene. Warden Doug Weber accompanied Robert into the execution chamber this evening. The Minnehaha County coroner was present to declare Robert dead.

None of Robert's friends or family were scheduled to attend, said Kadi.

Eric Donald Robert was incarcerated at the State Penitentiary in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, serving an 80-year sentence for a kidnapping conviction. In that case, an 18-year-old woman told police a man posing as a plainclothes police officer pulled over her car near Black Hawk, told her he needed to search it and then forced her into the trunk. She used her cell phone to call for help, and she was found unharmed.

Robert, who most recently was head of a city's water treatment department and had previously been a chemist with the Environmental Protection Agency, had more than $200,000 in assets and no debt when he was arrested on the kidnapping charges in 2005. Robert contends he was drunk and trying to rob the 18-year-old girl of $200, not sexually assault her. He was sentenced to 80 years in prison and would not have been eligible for parole until he was 83.

On April 12, 2011, in Minnehaha County, Robert and co-defendant Rodney Berget killed State Corrections Officer Ronald Johnson with a metal pipe. The pair attacked the prison guard, wrapped his head in plastic shrink wrap and left him to die before using his uniform to sneak past security in an unsuccessful escape attempt. Ronald Johnson was working alone in a part of the Sioux Falls prison known as Pheasantland Industries, where inmates work on upholstery, signs, custom furniture and other projects. Robert put on Johnson's brown pants, hat and lightweight jacket before approaching the prison's west gate with his head down, pushing a cart with two boxes wrapped in packing tape, according to an investigator's affidavit. Berget was hidden inside one of the boxes.

Another corrections officer opened an inner gate and allowed Robert to wheel the cart into a holding area, but became suspicious when Robert didn't swipe his electronic ID card. Robert claimed he forgot his badge and said main control was out of temporary cards. The officer then asked Cpl. Matthew Freeburg if he recognized the guard, and Freeburg said no. When the officer called for a supervisor, Robert started kicking and beating Freeburg and Berget jumped out of the box to join in. More officers arrived to find Berget still beating Freeburg. Robert had climbed the outer gate, reaching the razor wire on top. Both inmates were apprehended before leaving the grounds and taken to a jail in Sioux Falls. Freeburg was taken to a hospital, but returned to work the next day. Johnson, who had worked at the penitentiary for more than 23 years, was a father of two and grandfather of six.

He died on his birthday, said his son, Jesse Johnson. "He loved to relax and play with his grandkids," Jesse Johnson told the Argus Leader. "He never had a bad thing to say about anybody." Jesse Johnson said his father, known to friends and family as R.J., had lived through a riot at the penitentiary in 1993 and knew the danger of his job but never dwelled on it. At the sentencing hearing for Robert, a witness who responded to the "code 5" call for help testified, "I saw the sergeant pulling the saran wrap off of RJ's head, I knew it was RJ." Lynette Johnson, Ronald Johnson's widow, said she has a hard time responding when one of her six grandchildren ask about their papa.

Rodney Berget was also sentenced to death. Berget has been in and out of South Dakota's prison system since the mid-1980s and is serving life sentences for attempted murder and kidnapping. He was convicted of escaping from the penitentiary in 1984. In 1987, he and five other inmates again broke out of the same facility on Memorial Day by cutting through bars in an auto shop. He was caught in mid-July of that year.

"S. Dakota executes inmate who killed prison guard." (October 15, 2012 11:42 pm • Associated Press)

A South Dakota man who beat a prison guard with a pipe and covered his head in plastic wrap to kill him during a failed escape attempt was put to death Monday, in the state's first execution since 2007. Eric Robert, 50, received lethal injection and was pronounced dead at the state penitentiary in Sioux Falls at 10:24 p.m. He is the first South Dakota inmate to die under the state's new single-drug lethal injection method, and only the 17th person to be executed in the state or Dakota Territory since 1877.

Robert had no expression on his face. Asked if he had a last statement, Robert said: "In the name of justice and liberty and mercy, I authorize and forgive Warden Douglas Weber to execute me for the crimes. It is done." As the drug was administered, the clean-shaven Robert, wearing orange inmate pants with a white blanket wrapped around his upper body, appeared to be clearing his throat and then began gasping heavily. He then snored for about 30 seconds. His eyes remained opened throughout and his skin turned pale, eventually gaining a purplish hue.

Robert was put to death in the same prison where he killed guard Ronald "RJ" Johnson during an escape attempt on April 12, 2011. Robert was serving an 80-year sentence on a kidnapping conviction when he tried to break out with fellow inmate Rodney Berget, 50.

Johnson's widow, Lynette, said after the execution that she knows Robert's death will not bring back her husband, her children's father or her grandchildren's grandfather. "But we do know that the employees of the Department of Corrections and the public in general will be just a little bit safer now," Lynette Johnson said. "We need to have more attention and focus on the safety of all of the correctional officers in the state of South Dakota. Ron, none of you will ever know how great he is and is missed. We stand proud for Ron." Lynette Johnson, her two children and their spouses all witnessed the execution. No one from Robert's family was in attendance.

Robert ate his last meal of ice cream with his lawyer, Mark Kadi, on Saturday night before fasting for 40 hours for religious reasons. After the execution, Kadi said the execution was very "orderly and polished." "The problem was it was too orderly. It was so antiseptic and peaceful that it masked what was being done to the person," Kadi said. "If more people were able to see the events, there would be fewer of them."

Johnson was working alone the morning of his death _ also his 63rd birthday _ in a part of the prison known as Pheasantland Industries, where inmates work on upholstery, signs, custom furniture and other projects. Authorities said the inmates beat Johnson with a pipe, covered his head in plastic wrap and left his body on the floor. Robert then put on Johnson's pants, hat and jacket and approached the prison's west gate. With his head down, he pushed a cart loaded with two boxes. Berget was hidden in one of the boxes, according to a report filed by a prison worker after the slaying. Other guards became suspicious as the men got closer to the gate. When confronted, Robert beat one guard; other guards quickly arrived and detained both inmates.

Months later, Robert told a judge his only regret was that he hadn't killed more guards. He pleaded guilty to Johnson's slaying and asked to be sentenced to death, telling a judge last October that he would otherwise kill again. He never appealed his sentence and even tried to bypass a mandatory state review in hopes of expediting his death. Berget also has pleaded guilty in the killing but has appealed his death sentence. A third inmate, Michael Nordman, 47, was given a life sentence for providing materials used in the slaying.

Robert's execution could be the first of two in as many weeks. Donald Moeller is scheduled to be put to death the week of Oct. 28 for the 1990 kidnapping, rape and murder of a 9-year-old girl. Robert had been on death row only for about a year, Moeller has been there for more than two decades. Only three other inmates currently are on the state's death row. South Dakota's last execution before Monday took place in 2007, and that was the first in the state for 60 years. "You have few people on death row, few executions, and then you have this coincidence of cases coming all at once," said Richard Dieter, executive director of the nonprofit Death Penalty Information Center. "When people waive appeals, their cases start to move more quickly."

State v. Robert, 820 N.W.2d 136 (S.D. 2012). (Direct Appeal)

Background: Following defendant's guilty plea to first-degree murder for the death of a state penitentiary guard, and his waiver of his right to have a jury determine his sentence, the Circuit Court, Second Judicial Circuit, Minnehaha County, Bradley G. Zell, J., sentenced defendant to death. Defendant waived his right to appeal his death sentence.

Holdings: On mandatory sentence review, the Supreme Court, Gilbertson, C.J., held that: (1) death sentence was not imposed under the influence of passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor; (2) evidence supported findings of aggravating circumstances; and (3) death sentence imposed on defendant was not excessive or disproportionate to the penalty imposed in similar cases, considering both the crime and defendant. Affirmed.

GILBERTSON, Chief Justice.

[¶ 1.] Eric Robert pleaded guilty to first-degree murder for the death of penitentiary guard Ronald Johnson, a 23–year veteran correctional officer at the South Dakota State Penitentiary in Sioux Falls. Robert waived his right to a jury's determination of whether the death sentence would be imposed. The circuit court conducted a pre-sentence hearing and imposed the death penalty. Subsequent to pleading guilty, Robert has consistently sought imposition of the death penalty and that the execution be expedited. Even though Robert waived his right to appeal the death sentence, this Court is statutorily mandated to conduct a review of the death sentence. SDCL 23A–27A–9.

Facts

[¶ 2.] Robert was convicted of kidnapping in Meade County in January 2006. The Meade County Circuit Court sentenced him to 80 years in prison. This conviction resulted in Robert being incarcerated in the South Dakota State Penitentiary beginning in January 2006.

[¶ 3.] On April 12, 2011, Robert and Rodney Berget, also an inmate at the South Dakota Penitentiary, entered the Pheasantland Industries' building FN1 in the penitentiary complex.FN2 Because of their maximum security classifications, neither inmate was authorized access to this building. On this date, Johnson was working in the Pheasantland Industries' building. Robert and Berget assaulted Johnson by striking him with a lead pipe which they had acquired earlier specifically for that purpose. Johnson was repeatedly struck on the face and head with the lead pipe. An expert testified that the blows to the head continued after Johnson was on the ground. The attack fractured Johnson's skull in at least three locations and exposed a portion of his brain. He also suffered defensive wounds to his hands and arms. After immobilizing Johnson with the pipe, Robert and Berget wrapped Johnson's head in plastic wrap which prevented him from crying out and also from breathing. The inmates dragged Johnson's body behind a large crate to conceal him.

FN1. Pheasantland Industries is an enterprise within the walls of the State Penitentiary. FN2. A separate appeal is currently pending in this Court in regard to Berget. See State v. Berget, # 26318. We limit our factual review in this case to the record contained herein. See also n. 13.

[¶ 4.] Robert then dressed himself in Johnson's uniform and Berget climbed into a box placed on a four-wheel cart. Robert, dressed as Johnson, pushed the cart toward the west gate of the penitentiary. After observing that Robert did not swipe an ID badge, Correctional Officer Jodi Hall confronted Robert about his identity. When Robert's explanation did not satisfy her, Hall notified Officer Matt Freeburg. Freeburg told Hall to call the Officer in Charge. At this time, Berget sprang from the box and he and Robert began assaulting Freeburg. The inmates used Johnson's radio to beat Freeburg. Hall issued a distress call “Code Red—Code 3” on her radio. While Berget continued the assault on Freeburg, Robert attempted to scale the exterior gate of the penitentiary but became entangled in razor wire. Robert then attempted to grab a gun from the responding officers. When that did not work, Robert and Berget tried to bait the officers into shooting them. Unsuccessful and surrounded, Robert shook Berget's hand and the pair surrendered.

[¶ 5.] Because Robert was wearing Johnson's uniform, penitentiary staff began to search for Johnson. His body was discovered behind the crate in the Pheasantland Industries' building. His face was badly disfigured and swollen from the beating and asphyxiation. The correctional officer who found Johnson attempted CPR. Life-saving efforts continued after medical personnel arrived and on the way to the hospital, but all efforts proved futile. Johnson was declared dead at the hospital.

Procedural History

[¶ 6.] On September 16, 2011, Robert pleaded guilty to first-degree murder in violation of SDCL 22–16–1(1), 22–16–4(1), 22–16–12, and 22–3–3. Robert waived his right to a jury sentencing. The circuit court found Robert competent, that he was represented by competent counsel, and that the plea and jury waiver were entered voluntarily, knowingly, and intelligently.

[¶ 7.] Pursuant to South Dakota's statutes, a death penalty prosecution is conducted in two phases. See SDCL 23A–27A–2. The first phase adjudicates the defendant's guilt or innocence. Id. If a guilty verdict is returned, the trial is resumed “to hear additional evidence in mitigation and aggravation of punishment.” Id. Because Robert pleaded guilty, there was no trial on the guilt phase. Moreover, because he waived his right to jury sentencing, the penalty phase was tried to the circuit court.

[¶ 8.] In order for the death penalty to be considered, the State must prove at least one of the aggravating circumstances enumerated in SDCL 23A–27A–1 FN3 beyond a reasonable doubt. SDCL 23A–27A–6.FN4 Should at least one aggravating circumstance be proven, the death penalty can be considered. Id. At the pre-sentence hearing, defendants are allowed to present whatever relevant mitigating evidence they can muster. SDCL 23A–27A–2.

FN3. This section provides: Pursuant to §§ 23A–27A–2 to 23A–27A–6, inclusive, in all cases for which the death penalty may be authorized, the judge shall consider, or shall include in instructions to the jury for it to consider, any mitigating circumstances and any of the following aggravating circumstances which may be supported by the evidence: (1) The offense was committed by a person with a prior record of conviction for a Class A or Class B felony, or the offense of murder was committed by a person who has a felony conviction for a crime of violence as defined in subdivision 22–1–2(9); (2) The defendant by the defendant's act knowingly created a great risk of death to more than one person in a public place by means of a weapon or device which would normally be hazardous to the lives of more than one person; (3) The defendant committed the offense for the benefit of the defendant or another, for the purpose of receiving money or any other thing of monetary value; (4) The defendant committed the offense on a judicial officer, former judicial officer, prosecutor, or former prosecutor while such prosecutor, former prosecutor, judicial officer, or former judicial officer was engaged in the performance of such person's official duties or where a major part of the motivation for the offense came from the official actions of such judicial officer, former judicial officer, prosecutor, or former prosecutor; (5) The defendant caused or directed another to commit murder or committed murder as an agent or employee of another person; (6) The offense was outrageously or wantonly vile, horrible, or inhuman in that it involved torture, depravity of mind, or an aggravated battery to the victim. Any murder is wantonly vile, horrible, and inhuman if the victim is less than thirteen years of age; (7) The offense was committed against a law enforcement officer, employee of a corrections institution, or firefighter while engaged in the performance of such person's official duties; (8) The offense was committed by a person in, or who has escaped from, the lawful custody of a law enforcement officer or place of lawful confinement; (9) The offense was committed for the purpose of avoiding, interfering with, or preventing a lawful arrest or custody in a place of lawful confinement, of the defendant or another; or (10) The offense was committed in the course of manufacturing, distributing, or dispensing substances listed in Schedules I and II in violation of § 22–42–2.

FN4. This section provides: In nonjury cases the judge shall, after conducting the presentence hearing as provided in § 23A–27A–2, designate, in writing, the aggravating circumstance or circumstances, if any, which he found beyond a reasonable doubt. Unless at least one of the statutory aggravating circumstances enumerated in § 23A–27A–1 is so found, the death penalty shall not be imposed.

[¶ 9.] Robert's pre-sentence hearing began on October 24, 2011, and lasted four days. Following the hearing, the circuit court entered extensive findings of fact and conclusions of law. The circuit court found that the State proved beyond a reasonable doubt the existence of two aggravating circumstances: “the offense was committed against a law enforcement officer, employee of a corrections institution, or firefighter while engaged in the performance of such person's official duties,” and “the offense was committed by a person in, or who has escaped from, the lawful custody of a law enforcement officer or place of lawful confinement.” SDCL 23A–27A–1(7), (8). Although evidence had been presented regarding several other aggravating circumstances, the circuit court found it unnecessary to make further findings regarding any other aggravating circumstances. Because at least one of the enumerated aggravating circumstances had been proven, the circuit court concluded that consideration of the death penalty was appropriate.

[¶ 10.] The circuit court then turned to its consideration of the aggravating and mitigating evidence presented. See SDCL 23A–27A–2.FN5 The court began this analysis by noting Robert's intent and desire to die. The court concluded that such a wish is not an aggravating circumstance appropriately considered in the determination of whether the death penalty should be imposed. The court also noted that Robert had instructed his counsel not to present mitigating evidence on his behalf. However, the court indicated that it considered all mitigating evidence contained in the record. This mitigating evidence included Robert's acceptance of responsibility and mitigating evidence from the Meade County kidnapping file, of which the court took judicial notice. After considering both the aggravating and mitigating evidence, the court concluded that “the only effective and reasonable retribution or punishment under the totality of the circumstances in this matter is the imposition of the death penalty.”

FN5. This section provides: In all cases in which the death penalty may be imposed and which are tried by a jury, upon a return of a verdict of guilty by the jury, the court shall resume the trial and conduct a presentence hearing before the jury. Such hearing shall be conducted to hear additional evidence in mitigation and aggravation of punishment. At such hearing the jury shall receive all relevant evidence, including: (1) Evidence supporting any of the aggravating circumstances listed under § 23A–27A–1; (2) Testimony regarding the impact of the crime on the victim's family; (3) Any prior criminal or juvenile record of the defendant and such information about the defendant's characteristics, the defendant's financial condition, and the circumstances of the defendant's behavior as may be helpful in imposing sentence; (4) All evidence concerning any mitigating circumstances.

[¶ 11.] The circuit court entered a Judgment of Conviction and Warrant of Execution on November 10, 2011. On November 16, 2011, Robert filed a Waiver of Appeal, waiving his right to appeal his conviction. This waiver acknowledged his right to appeal, acknowledged discussing his waiver with counsel, and stated that the waiver was free and voluntary. The waiver was signed by Robert and was notarized.

[¶ 12.] Regardless of Robert's waiver of appeal, this Court is obligated to review each death sentence imposed in South Dakota. “If the death penalty is imposed, and if the judgment becomes final in the trial court, the sentence shall be reviewed on the record by the South Dakota Supreme Court.” SDCL 23A–27A–9. This Court conducts this review whether or not the defendant appeals the sentence. When the defendant appeals, this Court's statutorily obligated sentence review is consolidated with the direct appeal. Id. This Court obtained jurisdiction to conduct this sentence review when the circuit court clerk transmitted the record, transcripts, a prepared notice of the clerk, and report of the trial judge to this Court.FN6 See id.

FN6. Robert's position in this matter raised procedural issues as of yet unique to this State's death penalty procedure. Pursuant to SDCL 23A–27A–9, the circuit court clerk is to transmit the entire record and transcript to this Court in order to effectuate the mandatory sentence review. The time for transmittal of the record from the circuit court to this Court hinges upon completion of the transcripts. Because Robert chose not to appeal, he did not order transcripts in connection with his notice of appeal. However, transcripts needed to be ordered and completed both to effectuate this Court's sentence review and to commence the time for transmittal of the record from the circuit court to this Court. The circuit court, appropriately relying on SDCL 23A–32–1, issued an order directing the court reporters involved to prepare transcripts and charge the expense to the County. Completion and filing of the transcripts provided this Court with a complete record on which to conduct this mandatory sentence review and triggered the procedural mechanism for initiating that review when no notice of appeal was filed by Robert.

[¶ 13.] Upon obtaining jurisdiction, Robert's position raised with this Court an issue of first impression. It was clear to the Court that Robert had instructed his appointed counsel to make no argument against imposition of the death penalty. This Court is aware of society's interest in the constitutional imposition of the death penalty. See Commonwealth v. McKenna, 476 Pa. 428, 383 A.2d 174, 181 (1978). This interest exists independent of the State's interest in punishing Robert for his crimes. Aware that Robert's instructions prevented his appointed counsel from arguing against imposition of the death penalty and that the State would be arguing for imposition of the death penalty, this Court appointed an experienced criminal trial attorney as amicus curiae to identify and raise any potential issues not presented due to the respective positions of Robert and the State.FN7

FN7. Given Robert's position of seeking the death penalty, this Court concluded it was appropriate to appoint an amicus curiae to act as an independent “friend of the Court” to call to this Court's attention any issues which are relevant to its statutory and constitutional independent review of this case. The amicus did appropriately function in this manner. [T]he term “amicus curiae” literally means “a friend of the court.” It ordinarily implies the friendly intervention of counsel to call the court's attention to a legal matter which has escaped or might escape the court's consideration. The right to be so heard is entirely within the court's discretion.... He cannot be partisan. Neither can he be a party nor assume the functions of a party to an action. Matter of Estate of Ohlhauser, 78 S.D. 319, 322–3, 101 N.W.2d 827, 829 (1960).

[¶ 14.] Additionally, Robert's position called into question his competency—especially his competency to waive presentation of mitigating evidence at the pre-sentence hearing and urge his own execution. The record revealed that Dr. Manlove, a psychiatrist, had evaluated Robert for the purpose of determining his competency to stand trial.FN8 While it was clear that Dr. Manlove concluded Robert was competent to stand trial, Robert had prevented either the State or the circuit court from reviewing Dr. Manlove's report. At that point, Robert had sole access to the report and refused to release it to the circuit court or to the State. Given the gravity of the issues and potential outcome, this Court, sua sponte, requested the parties address the issue of Robert's competency. Specifically, this Court requested the parties' analysis of the appropriate competency standard, and whether Robert gave any indication of failing that standard. All parties, including the amicus curiae, agreed that the record revealed no concern as to Robert's competency. The circuit judge had found Robert competent, and Robert's in-court statements throughout the circuit court proceedings were those of a competent, intelligent man. Nevertheless, out of an abundance of caution, this Court accepted Robert's offer to review in-camera the Manlove report completed after Robert chose to plead guilty. The contents of this report, which remain under seal, alleviate our concerns regarding Robert's competency. FN8. Dr. Manlove had also evaluated Robert in connection with the Meade County proceedings.

[¶ 15.] With amicus appointed and Robert's competency settled, this Court entered an order setting a briefing schedule. Further, we ordered Robert's execution stayed until such time as this sentence review was completed. Robert strenuously objected to the briefing schedule and the resultant delay of his execution, arguing that this Court was without jurisdiction to stay his execution absent a direct appeal. We addressed Robert's objections in an earlier opinion. State v. Robert, 2012 S.D. 27, 814 N.W.2d 122. We determined that this Court has jurisdiction to stay Robert's execution pending our review. Id. This Court having received the briefs of Robert, the State, and amicus curiae, now proceeds to review Robert's sentence. FN9. Robert and the State both waived oral argument in this matter. As the parties' respective briefs illustrated no difference in their positions on the statutorily mandated areas of inquiry, we accepted the waiver and review Robert's sentence on the record presented. This should not be understood as rendering our review of Robert's death sentence cursory. As we have recognized: “This is in keeping with the mandate of the Supreme Court that we must review carefully and with consistency death penalty cases and not engage in ‘cursory’ or ‘rubber stamp’ type of review.” State v. Piper, 2006 S.D. 1, ¶ 83, 709 N.W.2d 783, 815 (quoting Arizona v. Watson, 129 Ariz. 60, 628 P.2d 943, 946 (1981)). See also Piper v. Weber ( Piper II ), 2009 S.D. 66, ¶ 6, 771 N.W.2d 352, 355 (“ ‘The penalty of death is qualitatively different from a sentence of imprisonment, however long. Death, in its finality, differs more from life imprisonment than a 100–year prison term differs from one of only a year or two.’ Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280, 305, 96 S.Ct. 2978, 2991, 49 L.Ed.2d 944 (1976). ‘The qualitative difference of death from all other punishments requires a correspondingly greater degree of scrutiny of the capital sentencing determination.’ California v. Ramos, 463 U.S. 992, 998–99, 103 S.Ct. 3446, 3452, 77 L.Ed.2d 1171 (1983)”).

Analysis

[¶ 16.] Regardless of whether a direct appeal is filed by a defendant, this Court is obligated to review each sentence of death imposed in this state. “If the death penalty is imposed, and if the judgment becomes final in the trial court, the sentence shall be reviewed on the record by the South Dakota Supreme Court.” SDCL 23A–27A–9. This Court is required to make certain enumerated inquiries regarding each death sentence. With regard to the sentence, the Supreme Court shall determine: (1) Whether the sentence of death was imposed under the influence of passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor; and (2) Whether the evidence supports the jury's or judge's finding of a statutory aggravating circumstance as enumerated in § 23A–27A–1; and (3) Whether the sentence of death is excessive or disproportionate to the penalty imposed in similar cases, considering both the crime and the defendant. SDCL 23A–27A–12. We address each inquiry in turn.

[¶ 17.] (1) Whether the sentence of death was imposed under the influence of passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor.

[¶ 18.] The pre-sentence verdict illustrates the circuit court's thought process in reaching its sentencing conclusion. The conclusion was based on appropriate considerations including: Robert's future dangerousness, including his threat to kill again; his violent history, including the 2005 kidnapping; his ability to be rehabilitated; and the severity and depravity of the crime. The court also considered any mitigating evidence it could find, despite Robert's desire that no such evidence be presented. None of the considerations articulated as factoring into the sentencing decision evidence the influence of passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor.

[¶ 19.] Perhaps the obvious manner in which Robert fights so vigorously for his execution calls us to review the propriety of it. Robert's passion toward this end generates an examination of the manner in which the sentence was imposed. Robert's persistent efforts to hasten his own death necessitate intense scrutiny to guarantee his desire to die was not a consideration in the sentencing determination. We do not participate in a program of state-assisted suicide. “The State must not become an unwitting partner in a defendant's suicide by placing the personal desires of the defendant above the societal interests in assuring that the death penalty is imposed in a rational, non-arbitrary fashion.” Grasso v. State, 857 P.2d 802, 811 (Okla.Crim.App.1993) (Chapel, Judge, concurring). Indeed, had the sentencing determination been based in any degree on Robert's desire to die, the sentence may have been impermissibly imposed based on a non-statutory arbitrary factor—Robert's suicide wish. See Lenhard v. Wolff, 444 U.S. 807, 815, 100 S.Ct. 29, 33, 62 L.Ed.2d 20 (1979) (Marshall, J., dissenting). If that were the case, and the record revealed that the circuit court based its decision on Robert's desire to die, this Court would be obligated to reverse the sentence of death and remand for resentencing. See SDCL 23A–27A–13. It is not a statutory aggravating circumstance to invoke the death penalty. See SDCL 23A–27A–1. However, the circuit court went out of its way to make it clear that the sentencing decision was based in no part on Robert's desire to die. This Court can affirm the constitutional imposition of the death penalty imposed in accordance with our statutes; it will not sanction state-assisted suicide.