10th murderer executed in U.S. in 2005

954th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in North Carolina in 2005

35th murderer executed in North Carolina since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

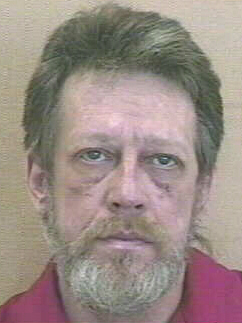

William Dillard Powell W / M / 45 - 58 |

Mary Gladden W / F / 54 |

Summary:

A veteran who had no prior criminal record, seeking cash to support a cocaine addiction, attempted to rob a convenience store in Shelby unarmed on Halloween in 1991. When the clerk, 54 year old Mary Gladden, resisted, Powell picked up a tire iron kept under the counter and beat Gladden to death. Powell was later identified by another customer and upon arrest confessed to the murder.

Citations:

Powell v. Lee, 282 F.Supp.2d 355 (4th Cir. 2003). (Habeas)

State v. Powell, 459 S.E.2d 219 (N.C. 1995). (Direct Appeal)

Final Meal:

At 5:30 p.m. Thursday night he had his last meal: A medium, thin-crust pizza with pepperoni, mushrooms and Canadian bacon, and a hamburger with mustard, chili and onions and a 20-ounce Pepsi.

Final Words:

None.

Internet Sources:

Powell, William Dillard

DOC Number: 0329098

DOB: 09-25-46

RACE: WHITE

SEX: MALE

DATE OF SENTENCING: 04-29-93

COUNTY OF CONVICTION: CLEVELAND COUNTY

North Carolina Department of Correction (Chronology / Press Release)

William Powell - Chronology of Events

3/11/2004 - William Powell executed at 2 a.m. Powell is pronounced dead at 2:09 am.

3/10/2004 - Governor Michael Easley denies clemency.

3/10/2004 - U.S. Supreme Court denies application for stay of execution and petition for writ of certiorari.

3/9/2004 - Powell's petition for writ of certiorari and petition for writ of habeas corpus, along with the application for stay of execution were denied by the Supreme Court of North Carolina

3/9/2004 - Witnesses named for Powell execution.

1/24/2005 - Correction Secretary Theodis Beck sets an execution date of March 11, 2005

1/10/2005 - U.S. Supreme Court denies Powell's petition for a writ of certiorari.

7/28/1995 - North Carolina Supreme Court affirms Powell's conviction and sentence of death.

4/29/1993 - William Dillard Powell sentenced to death in Cleveland County Superior Court for the first degree murder of Mary Gladden.

GOV. EASLEY DENIES CLEMENCY IN POWELL CASE Release: IMMEDIATE - Raleigh - Gov. Michael F. Easley today denied the clemency petition filed by William Dillard Powell, a convicted murderer scheduled for execution at 2:00 a.m. on Friday, March 11, 2005.

Powell is on death row for the October 31, 1991 beating death of Mary Gladden, a Cleveland County resident. Powell was also convicted of robbery with a dangerous weapon. “Having carefully reviewed the clemency petition, I conclude that there are no compelling reasons to invalidate the sentence recommended by the jury and affirmed by the courts,” Easley said.

North Carolina Department of Correction

For Release: IMMEDIATE

Contact: Pamela Walker

Date: March 9, 2005

Phone: (919) 716-3700

Witnesses selected for William D. Powell execution

RALEIGH- Witnesses have been named for the execution of William D. Powell, who is scheduled to die by lethal injection March 11 at 2 a.m. at Central Prison in Raleigh. Powell was convicted in Cleveland County and sentenced to death for the 1991 murder of Mary Gladden.

Official Witnesses

William C. Young – District Attorney, Cleveland County

Richard L. Shaffer – Assistant District Attorney, Cleveland County

Lt. Rick Beaver – Cleveland County Sheriff’s Office

Lt. David Frank Crow – Cleveland County Sheriff’s Office

Keith Carroll – Victim’s family member

Ricky Carroll – Victim’s family member

Media Witnesses

Bill Holmes – Associated Press

Tracey Early – News 14 Carolina, Raleigh

Amelia Townsend – The Shelby Star

For Release: IMMEDIATE

Contact: Pamela Walker

Date: January 24, 2005

Phone: (919) 716-3700

Execution date set for William Dillard Powell

RALEIGH - Correction Secretary Theodis Beck has set March 11, 2005 as the execution date for inmate William Dillard Powell. The execution is scheduled for 2:00 a.m. at Central Prison in Raleigh.

Powell, 58, was sentenced to death April 29, 1993 in Cleveland County Superior Court for the Oct. 31, 1991 murder of Mary Gladden.

Central Prison Warden Marvin Polk will explain the execution procedures during a media tour scheduled for Monday, March 7 at 10:00 a.m. Interested media representatives should arrive at Central Prison’s visitor center promptly at 10:00 a.m. on the tour date. The session will last approximately one hour.

The media tour will be the only opportunity to photograph the execution chamber and deathwatch area before the execution. Journalists who plan to attend the tour should contact the Department of Correction Public Affairs Office at (919) 716-3700 by 5:00 p.m. on Friday, March 4.

ATTENTION EDITORS: A photo of William Dillard Powell (#0329098) can be obtained by using the "Offender Search" function on the Department of Correction Web site at www.doc.state.nc.us. For more information about the death penalty, including selection of witnesses, click on “The Death Penalty” link.

"N.C. man is executed for '91 murder; Clemency denied in beating death," by Andrea Weigl. (March 11, 2005)

RALEIGH, N.C. -- A Shelby man was executed early today for the Halloween 1991 slaying of a convenience store clerk. William Dillard "Bugsy" Powell, 58, had been sentenced to death by lethal injection for the beating death of Mary Gladden. Gov. Mike Easley denied a petition for clemency Thursday evening, after the U.S. Supreme Court had rejected a stay of execution.

In 1991, Gladden, who worked at The Pantry in Shelby, tried to stop an unarmed Powell from robbing the store. She was hit over the head with what is thought to have been a tire iron, which was kept in the store but never recovered afterward. Powell's motive for the robbery was to get money to buy cocaine. He was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death after a 1993 trial.

Powell's lawyers tried to prevent his execution by questioning the fairness of a death sentence for what they see as a less egregious murder. They also wanted a hearing on whether prosecutors violated Powell's rights at trial by failing to reveal a deal to dismiss a felony against a key witness. The alleged prosecutorial misconduct was discovered only a few weeks ago and was not evaluated by a judge. Those arguments did not persuade the Supreme Court.

Neither Cleveland County District Attorney Bill Young nor Gladden's relatives returned calls asking for comment. Young, two of Gladden's relatives, Keith and Ricky Carroll, and several investigators planned to witness the execution, scheduled for 2 a.m. at Central Prison in Raleigh.

For his last meal, Powell drank a 20-ounce Pepsi and ate a hamburger with mustard, chili and onions and a medium thin crust pizza with pepperoni, mushrooms and Canadian bacon.

Before the 1991 slaying, Powell had been honorably discharged from the Army and served as a volunteer with the rescue squad of the Shelby Fire Department, his lawyers say. He was an excellent caregiver to his autistic son and even helped the PTA at his son's school, they say. However, his lawyers say, Powell's life took a downward turn as he succumbed to drug and alcohol abuse. On the night of the killing, Powell was high on cocaine and Xanax, an anti-anxiety drug, they say.

Prior to his decision, Easley had heard a request for clemency from Peter Bearman, chairman of the sociology department at Columbia University. In 1997, Bearman, then a professor of sociology at UNC-Chapel Hill, analyzed more than 100 death penalty cases across the state between 1978 and 1995. Based on factors identified by the N.C. Supreme Court, he evaluated -- in layman's terms -- whether the sentences fit the crimes. Bearman decided that Powell's sentence didn't seem to fit, or that other murder cases with similar facts resulted in life sentences.

Until a month ago, Bearman had no connection to Powell's case. Powell was featured in Bearman's report, but the professor had been hired by another lawyer who hoped the analysis would help another death row inmate. After learning Powell was set to be executed, Bearman came to Raleigh to ask Easley to grant clemency.

William Powell was convicted of the first-degree murder of Mary Gladden, an employee of The Pantry on Charles Road in Shelby, and sentenced to death. The State's evidence tended to show that Mary Gladden was killed on October 31, 1991 while on duty at The Pantry.

Scott Truelove testified that he bought five dollars' worth of gasoline there between 3:15 and 3:30 a.m. At the counter he stood near a rough-looking man with unkempt, shoulder-length hair, facial hair, and a tattoo on his left forearm. The next morning Truelove read about the murder and gave a description of the man to Captain Ledbetter of the Shelby Police Department. On November 16, 1991 Truelove identified Powell as the man by picking him out of a photographic lineup.

On October 31, 1991 Clarissa Epps stopped at The Pantry to buy gasoline at approximately 4:15 a.m. She went in to pay for her purchase. After waiting in vain for a clerk to appear, Epps called out but received no answer. Epps then turned and saw Mary lying in blood behind the counter. Epps drove home and called the police. Officer Mark Lee of the Shelby Police Department arrived at The Pantry at 4:26 a.m. in response to a radio dispatch. Lee first ensured that all customers had left the store and then found Mary behind the counter. She was lying on her back in a pool of blood with her head toward the cash register and her hands at her sides. Lee noticed injuries to Mary's left eye and ear as well as other injuries to her head. He also saw a one-dollar bill on the floor near her left foot and another on the counter. Dr.

Stephen Tracey, who performed the autopsy, testified that Mary had numerous lacerations on her head and that her skull was fractured in several places. Additionally, her nose was broken and her left eye had been displaced by a fracture to the bone behind it. Mary's brain had hemorrhaged, was bruised and lacerated in several places, and contained skull fragments. Tracey determined that blunt trauma to the head caused Mary's death and that she died from the trauma before she lost a fatal amount of blood. He also concluded that human hands had not inflicted the wounds; he surmised from their size and shape that the perpetrator used a lug-nut wrench, a tire wrench, or possibly a pipe.

Mark Stewart, an employee of The Pantry, testified that he worked on October 27 and November 1, 1991. On October 27 Stewart saw a tire tool behind the counter to the side of the cash register. The tool had lain there for approximately one year. It was curved on one end with a round hole for a lug nut and was split on the other end for hubcap removal. Stewart noticed that the tool was missing when he worked on November 1, the day after the murder. Thomas Tucker, a district manager of The Pantry, testified that he arrived at The Pantry sometime after 6:00 a.m. on October 31 . He examined the cash register tape for that morning; it showed, among other transactions, a gasoline sale of five dollars at 3:29 a.m. and a no-sale at 3:35 a.m. The cash register enters a no-sale when it is opened but no purchase is made. According to the tape, no transaction occurred between the five-dollar purchase and the no-sale. Tucker opened the register at 6:22 a.m. at the direction of Captain Ledbetter to determine whether any money had been taken during the homicide. He concluded that approximately forty-eight dollars were missing.

On November 16, 1991 Lieutenant Mark Cherka and Officer David Lail drove to Anthony's Trailer Park to find Powell and bring him to the police station for questioning. Powell came out of a trailer and allowed Cherka to take four photographs of him. Powell agreed to accompany Cherka and Lail to the police station for questioning as a possible suspect in the murder. Powell was not under arrest at that time; the officers told him he did not have to leave with them. They arrived at the police station at approximately 4:00 p.m., and Cherka began to question Powell. Powell refused to allow Cherka to tape record the interview, so Cherka made notes of what transpired shortly after the interview ended. Powell stated that he had gone to sleep at around 4:00 a.m. on 31 October after drinking with Don Weathers and Powell's girlfriend, Lori Yelton. Later that morning Yelton and Powell took Weathers to the hospital because he had cut himself at some point during the previous night.

Cherka left the interview room and related Powell's statement to Ledbetter. While Cherka had been questioning Powell, Truelove had identified Powell from a lineup containing thirty-two photographs as the man he saw in The Pantry on 31 October. Ledbetter informed Cherka of the identification and then accompanied Cherka back into the interview room. Powell again indicated he did not want to be tape recorded, and Ledbetter complied. Ledbetter told Powell about Truelove's identification and asked Powell if he wanted an attorney. Powell stated that he had not killed anyone and did not want an attorney. Ledbetter advised Powell of his Miranda rights, and Powell signed a waiver of those rights. Powell continued to deny involvement in the murder. Ledbetter then told him he knew he had killed the woman and asked, "Why did you kill her?" Powell hung his head and answered, "[S]he slapped me and I went off on her." Powell then asked to speak to Ledbetter alone; Cherka left the room. Ledbetter again asked Powell why he had killed Mary. Powell stated that she had slapped him, he had panicked, he had not intended to harm her, and he merely wanted the money from the cash register. Powell then indicated that he wanted to speak to Ledbetter off the record and asked Ledbetter to tear up the Miranda waiver form, which Ledbetter did. Powell related additional details about the crime, including information about the weapon he had used, after Ledbetter ripped the form into four pieces.

At about 6:00 p.m. Powell asked for a lawyer, and one was contacted for him. Powell was arrested and taken into custody after he conferred with his lawyer. Powell testified that he did not read the Miranda waiver form, but signed it because he felt "agreeable" from cocaine he had ingested. He further testified that Ledbetter suggested they talk off the record. On cross-examination he admitted he had given Miranda warnings during his tenure in law enforcement; he recited the warnings on the witness stand. He also admitted he had not mentioned in his pretrial affidavit that Ledbetter proposed that they talk off the record.

Billy Joe Sparks testified that sometime after the murder he had a conversation with Paul Barnard, who called himself Rambo. During the conversation Rambo sniffed glue and both men drank beer. Rambo told Sparks he had killed a woman at a supermarket by beating her to death. Rambo died before Powell's trial; Sparks did not tell the police about Rambo's statement until after Rambo's death. Johnny Smith, the operator of a local entertainment center, testified that he had spoken to Truelove about the murder. Smith stated that Truelove told him he had seen a man with red hair in The Pantry on the day of the murder. In rebuttal the State recalled Truelove. He testified that he knew Rambo and that the lineup from which he identified Powell contained a photograph of Rambo. Truelove never picked Rambo as the person he saw at The Pantry on 31 October. Truelove also testified that he remembered having a conversation with Smith about becoming an uncle, not about the murder. Truelove and his sister both have red hair, and his sister had recently given birth to a baby with red hair.

The State also called Officer James Glover of the Shelby Police Department in rebuttal. Glover testified that Rambo claimed to be a Vietnam veteran and to have a black belt in karate; neither claim was true. Before his death Rambo had telephoned Glover and told him he had lied to Sparks about committing the murder. Rambo told Sparks he had killed a woman only to maintain his street image. At sentencing the State relied on the evidence it presented at the guilt/innocence phase. Powell's evidence showed that Powell was raised in a loving family, had worked as a jailer and with the fire department, and was well-liked and not violent.

Dr. Terrence Onischenko, an expert in psychology and neuropsychology, testified that he performed comprehensive testing of Powell on 22 November 1992. The results showed that Powell's memory, problem-solving skills, and motor functions are impaired. Powell scored in the average range on other tests. Dr. Onischenko also testified that Powell has an increased chance of developing Alzheimer's disease as well as other organic diseases. Powell's abuse of cocaine and alcohol probably caused his brain dysfunctions. Powell has an average IQ and normal concentration skills, language functions, sensory ability, and visual ability. Powell also presented evidence showing that he took good care of his son, who is profoundly mentally retarded and autistic. Powell implemented the programs devised for his son's development and served on the advisory council of the parent-teacher organization at his son's school.

Two jailers at the Cleveland County jail testified that Powell had adjusted well to life as an inmate and had caused no problems. The jury found Powell guilty of first-degree murder under the felony murder rule, with robbery with a dangerous weapon as the underlying felony. At sentencing the jury found one aggravating circumstance, that the murder was committed for pecuniary gain, and no mitigating circumstances. It unanimously recommended that Powell be sentenced to death; the trial court sentenced Powell accordingly.

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

William Powell - North Carolina - March 11, 2005

The state of North Carolina is scheduled to execute William Dillard Powell on March 11, 2005 for the 1991 murder of Mary Gladden in Cleveland County.

While under the influence of cocaine, Powell entered a convenience store with the intent of robbing the store. He was unarmed when he entered the store and maintains he did not plan to harm anyone. When Gladden attempted to impede the robbery Powell picked up a heavy tool from behind the counter and used it to beat her to death.

Powell’s life had been taken over by his addictions to cocaine and alcohol, leaving him unable to hold a steady job to support himself. It also caused him to suffer from brain dysfunctions that impaired his memory, problem-solving skills, and motor skills. His condition worsened when he was under the influence of cocaine or alcohol, as he was when the murder of Gladden occurred.

Before becoming addicted to cocaine, he was the sole caretaker for his son who was profoundly retarded and autistic. He was very involved in his son’s care and development and even served on the advisory council for the Parent Teacher Organization at his son’s school. Powell also served in the U.S. Army, was a member of the Shelby Fire Department, and volunteered with the rescue squad.

Powell’s defense argued that his trial was unfair for several reasons. The defense was not entitled to individual voir dire during jury selection. Voir dire allows either attorney to challenge a perspective juror if he or she says or expresses a bias against the attorney’s case. The judge determined this was justified because he wanted to avoid the alleged domino effect of group voir dire, whereby one juror learns which answers will help him/her avoid jury duty.

However, the defense maintained they should have been allowed the privilege of voir dire. The jurors were not given peremptory instructions on mitigating circumstances in the penalty phase of the trial, which the defense feels should have occurred. The defense also argues that the confession Powell made after his Miranda waiver was destroyed should not have been admissible. The defense was also prohibited from alerting the jurors of some important statutory mitigating circumstances. For instance, the defense could not tell the jurors that Powell had no significant history of prior criminal activity.

The defense was not allowed to tell jurors that he had been a model prisoner while incarcerated. Lastly, the defense contends the prosecution belittled the sentencing process when they informed the jurors to focus on the crime instead of the mitigating evidence.

Please take a moment to urge Governor Easley to stop the execution of William Dillard Powell!

"Convenience-store clerk killer executed by injection." (AP Friday, March 11, 2005)

RALEIGH, N.C. - The killer of a convenience-store clerk was executed by injection early Friday despite arguments from death penalty opponents that his crime would receive a less severe punishment in 40 other states.

William Dillard Powell, 58, was sentenced to death in 1993 for killing Mary Gladden as he tried to rob her for drug money. Powell was high on cocaine and beat the 54-year-old Gladden to death with a tire iron he found in the Cleveland County store because she fought back, his lawyers said. Powell was pronounced dead at 2:09 a.m., said correction system spokeswoman Pam Walker. He declined to make a final statement and in the minutes before the lethal drugs were injected, Powell told his sister that he loved her. Execution witnesses were separated from Powell by a thick glass window.

The execution came after the U.S. Supreme Court declined late Thursday to review the case. Gov. Mike Easley denied clemency. "Having carefully reviewed the clemency petition, I conclude that there are no compelling reasons to invalidate the sentence recommended by the jury and affirmed by the courts," Easley said in a release.

Ken Rose, director of the Center for Death Penalty Litigation in Durham, which is assisting Powell's attorneys, said Powell does not deserve to be executed because he did not premeditate his killing and the only legally aggravating factor is attempted robbery. Forty other states would not allow an execution in such a case, Rose argued.

The state Supreme Court rejected a defense argument Wednesday that the courts had not adequately considered a recently lodged complaint claim of prosecutorial misconduct during Powell's trial. Attorneys said Cleveland County District Attorney Bill Young, who prosecuted the case, failed to reveal a deal with Powell's girlfriend, Lori Yelton Donohue, in exchange for her testimony at the 1993 trial. Prosecutors are required to tell the defense about any promises made to witnesses.

Powell was moved Wednesday to the death watch area at Central Prison in Raleigh, a spokeswoman for the state Department of Correction said. At mid-afternoon Thursday he had met with his lawyers, spokeswoman Pam Walker said. Powell's sister also was scheduled to visit.

At 5:30 p.m., he had his last meal: A medium, thin-crust pizza with pepperoni, mushrooms and Canadian bacon; a hamburger with mustard, chili and onions and a 20-ounce Pepsi. Powell was the first person executed in North Carolina this year and the 35th since capital punishment was reinstated in 1977. No other executions are currently scheduled.

Death row in North Carolina is home to 178 men and four women. That includes four defendants who committed their crimes as 17-year-olds whose death sentences were thrown out last week by the U.S. Supreme Court.

"Execution unfair for unintentional murder; Powell's case shows that sometimes the system simply doesn't work," by David Teddy. (Posted on Wed, Mar. 09, 2005)

(RALEIGH) - David Teddy has practiced law in Shelby since 1988. He was recently appointed to represent William Powell as a result of the death of Powell's former attorney, Tony Lynch, who died of a brain tumor.

I want to express my sincere sympathy to Mary Gladden's family. Her tragic death should never have occurred. My remarks are in no way intended to minimize the pain and sorrow her family has been forced to endure by the loss of their loved one. My plea, instead, involves our state's responsibility to dispense punishment fairly and evenhandedly -- a responsibility even more demanding when the punishment is the ultimate, irreversible sentence of death.

This Friday at 2 a.m. our state is scheduled to execute William Dillard Powell Jr. If the execution proceeds, our state will have the unfortunate distinction of executing a man with no history of violence other than the unintentional killing for which he was sentenced to death. Gov. Mike Easley has the power to stop this execution by granting clemency, a decision that would be entirely consistent with the two other occasions when he decided to spare individuals from a death by lethal injection.

Powell was sent to death row despite the fact that a seasoned and experienced trial judge ruled that he had no intention of killing Mary Gladden during a convenience store robbery. Only a minority of states even permit the execution of persons who do not intend to kill, and very few states actually execute persons convicted of unintentional murders. That he did not intend to kill is not the only reason a death sentence for Powell is excessive. While every murder is horrific, there have been far worse murders in Cleveland County -- premeditated killings committed by persons with violent histories -- that did not result in a death penalty. In fact, press reports indicate the last execution from Cleveland County occurred in 1935.

Justice requires that similar persons committing similar crimes receive similar punishments. That is not so in this case. Powell is the only person on death row in North Carolina for unintentional murder. Why haven't these issues been addressed by the court system? The answer is that in this case the courts have failed.

All death penalty cases in our state are subjected to a proportionality review by the N.C. Supreme Court. A comprehensive study of the court's proportionality review process found that Powell's case represents the single most egregious failing of that review. This study was undertaken by a law professor who was attempting to help another inmate, not Powell, but the professor identified Powell's case as the one that stood out among all others as a chilling example of how the criminal justice system can fail in a case involving the ultimate punishment of death.

Should North Carolina execute a man whose punishment is so grossly disproportionate to other cases? Central to the U.S. Supreme Court's application of the death penalty is the notion it should be reserved for the worst offenders who commit the worst crimes. Justice Anthony Kennedy, in last week's decision on juveniles, echoed that sentiment when he wrote, "Capital punishment must be limited to those offenders who commit `a narrow category of the most serious crimes' and whose extreme culpability makes them `the most deserving of execution.' "

Powell, a former volunteer firefighter and Army veteran who had no history of violent acts and was the loving, devoted father of a severely autistic and mentally retarded boy, surely does not fit that description. His life spiraled out of control when he became addicted to alcohol and began using crack cocaine. On the night of the crime back in 1991, in a desperate act to obtain money to buy drugs, he entered a Shelby convenience store. He was unarmed. During the robbery he panicked. Prosecutors said he killed the clerk, Mary Gladden, with a heavy tool he found in the store. The trial court judge found that there was no premeditation in the fatal act.

There's no question he should be severely punished for her unintended death. But should he be executed? Is Powell really the "worst of the worst"?

Sometimes defendants get caught up in a criminal justice system that does not always treat people equally. Sometimes, on second glance, the punishment handed out by a jury or judge just doesn't look right. Sometimes a defendant simply needs a safety net to ensure that his case does not slip through the cracks, especially when the penalty is death. Powell's case is a powerful demonstration for the governor and legislators that sometimes the system simply doesn't work. This is precisely the reason the governor was given the power to grant clemency.

As his execution draws near, William Powell is standing at the door of death, anxiously awaiting word from the governor. It is my sincere hope and earnest prayer that Gov. Easley will close the door on this terrible tragedy by granting clemency -- a decision that will allow Powell the opportunity to die a natural death in prison, not a death hastened by poison pumped into his veins.

"State executes Shelby woman's killer," by William Holmes. (AP Updated: 3/11/2005 5:00 PM)

RALEIGH, N.C. -- A man convicted of beating a convenience-store clerk to death with a tire iron was executed early Friday after the courts rejected arguments that his crime didn't meet the legal standard for the death penalty.

William Dillard Powell, 58, died by injection at 2:09 a.m., said corrections spokeswoman Pam Walker. He was convicted in 1993 of killing Mary Gladden, 54, after he tried to steal money to buy drugs. He was high on cocaine at the time of the robbery attempt.

Powell declined to make a final statement. He told his sister, Lavonda Camp, through the double-paned glass in the death chamber that he loved her minutes before his execution started at 2 a.m. He turned quickly toward the back of the room and spoke with his executioners as they began to administer the lethal injection. He then began to count down from 99. His lips stopped moving about the time he reached 95. Gladden's sons, Keith Carroll and Ricky Carroll, watched without any apparent emotion. Camp sobbed as one of her brother's attorneys, Marilyn Ozer, hugged her around her shoulders. Ozer drew her closer as the prison warden pronounced Powell's death.

Powell should not have been executed because the killing was not premeditated and because the only aggravating factor was attempted robbery, the same charge used to bolster the murder count to felony murder and make Powell eligible for execution, Ken Rose of the Center for Death Penalty Litigation in Durham argued. Forty other states would not allow an execution in such a case, Rose said.

The Supreme Court declined late Thursday to review Powell's case and Gov. Mike Easley denied his request for clemency later in the evening. The state Supreme Court rejected a defense argument Wednesday that the courts had not adequately considered a recent claim of prosecutorial misconduct during Powell's trial. Powell's lawyers said Cleveland County District Attorney Bill Young failed to reveal a deal with Powell's girlfriend, Lori Yelton Donohue, in exchange for her testimony against their client. Prosecutors are required to tell the defense about any promises made to witnesses.

Powell was moved Wednesday to the death watch area at Central Prison in Raleigh. He spent most of his last day with his lawyers, Ozer, James Glover and William Massengale. His sister visited him about 10 p.m. and spent about an hour with him, state Department of Correction spokeswoman Pam Walker said. Powell's sister also was scheduled to visit. At 5:30 p.m., he had his last meal: A medium, thin-crust pizza with pepperoni, mushrooms and Canadian bacon; a hamburger with mustard, chili and onions and a 20-ounce Pepsi.

Powell was the first person executed in North Carolina this year and the 35th since capital punishment was reinstated in 1977. No other executions are currently scheduled. Death row in North Carolina is home to 178 men and four women. That includes four defendants who committed their crimes as 17-year-olds whose death sentences were thrown out last week by the U.S. Supreme Court.

People of Faith Against the Death Penalty

William Dillard Powell is scheduled to be executed by North Carolina March 11, 2005.

He was sentenced to death in 1993 for the murder of Mary Gladden in Cleveland County. She died during William Powell's attempt to rob the convenience store where she worked.

William never intended to kill, or even hurt, anyone. In fact, he was unarmed when he entered the store. The trial judge specifically found that there was no evidence of premeditation, and that the killing was not the result of premeditation on William's part.

William Powell was a loving and caring father. When his ex-wife gave up custody of their autistic and mentally retarded son Bobby in 1988, he assumed custody, becoming very involved and dedicated to Bobby's care and development. He served on the advisory council for the Parent Teacher Organization at North Shelby School, Cleveland County's school for students with physical or mental disabilities.

Professionals who worked with Bobby described William's relationship with his son as "very, very close and very, very intense and tight ... and that [Bobby] really derive[ed] benefit from his daddy's involvement with him."

William's life was devastated by alcohol and drug abuse. The addictions took over and destroyed his life, leaving him incapable of gainful and productive employment. On Oct. 31, 1991, high on cocaine and Xanax, William robbed a convenience store for crack money for his girlfriend. A heavy tool kept behind the counter became the murder weapon. A neuropsychologist found that William suffered from longstanding brain dysfunctions which impaired his judgment, reasoning and logic. The impairments worsened when he was under the influence of drugs and alcohol, as he was the night of the crime.

Before Powell's life deteriorated, he served our country with honor as a sergeant in the U.S. Army. He served his community as a member of the Shelby Fire Department, volunteer with the rescue squad, and in other roles. Prior to receiving the death penalty, William had no history of violence. Since being on death row, he has had an exemplary disciplinary record.

Mr. Powell's case is not one of the "worst of the worst." To execute William Powell would violate the important principle that the death penalty is reserved for those whose offenses are the most blameworthy.

The information above was provided by William Powell's legal defense team.

Take Action!

URGE YOUR CONGREGATION AND YOUR MINISTER TO GET INVOLVED. Meet with your congregation's pastor, rabbi or leader. Ask him or her to preach against this execution and against the death penalty, even if you are sure he or she would not want to do so.

Write an article for the bulletin and announce the protests against the death penalty. Announce the actions (listed below) people can take. Ask your minister or rabbi to write a letter to Gov. Easley.

Urge your congregation to pass a resolution for a moratorium on executions.

CONTACT NC GOV. MIKE EASLEY at:

North Carolina Coalition for a Moratorium

"Lawyers make appeal for Cleveland County man scheduled for execution," by Barry Smith. (Shelby Star 3/3/05)

RALEIGH — Saying the murder William Dillard Powell Jr. committed doesn’t deserve the death penalty, lawyers for and supporters of the condemned killer asked Gov. Mike Easley on Wednesday to grant their client clemency.

Calling the case “aberrant,” Columbia University sociologist Peter Bearman said that other people committing crimes similar to what Powell committed didn’t get the death penalty. “It’s chillingly clear,” Bearman said. “The cases most similar to it are cases that juries returned a sentence of life.” Bearman made the statements at a press conference Wednesday afternoon following the clemency hearings at the state Capitol earlier in the day.

“The death penalty in this rare and unique case does not represent equal justice under the law,” said Shelby lawyer David Teddy, helping the defense team.

Powell is scheduled to die by lethal injection at 2 a.m. March 11 in the state’s death chamber at Central Prison for the Oct. 31, 1991, beating death of convenience store clerk Mary Gladden.

Defense attorney Bill Massengale said Powell was tried for first-degree murder under the felony murder law. That law allows a defendant to be tried for first-degree murder even if there is no premeditation if the murder occurred during the commission of a felony. In the Powell case, the felony involved was the robbery at the Pantry at Charles and Dellinger roads in Shelby. The sole aggravating factor was pecuniary gain — or money, he said

Cleveland County District Attorney Bill Young attended the clemency hearing but refused to comment afterward. Two retired Shelby police detectives — Dale Ledbetter and Preston Cherka — also attended the hearing. “In my 27 years with the city of Shelby, it’s the most heinous crime I’ve investigated,” Ledbetter said. Cherka said that Powell killed Ms. Gladden with a tire tool. “He went in to rob to get money for a girl he was seeing to get drugs,” Cherka said.

Some members of Ms. Gladden’s family were also at the Capitol Wednesday. However, they did not meet with Easley. They also declined comment.

Supporters of Powell painted a picture of a good person before he encountered substance abuse problems. They said Powell enlisted in the Army at 17 and had also worked as an emergency medical technician and a firefighter. “Before he got touched with cocaine, he was really a fine person,” Massengale said. Sharon Gensch, who taught Powell’s autistic son Bobby, said Powell did a lot to help his son. “I knew Mr. Powell to be a very loving and very devoted father to Bobby,” she said. “He helped us with the Special Olympics.” She said she feared that if Powell is executed, the news of the execution could cause Bobby, now 21, to regress.

Defense lawyers also cast doubt over a recording of a phone call between Powell and the woman he was seeing at the time of the murder, Lori Yelton. Teddy said that Ms. Yelton’s credibility could have been challenged if attorneys had known that she was in line to receive help for her role in taping the call. He said that a firearm larceny charge was dismissed within a few months of Powell’s murder trial.

Teddy said he was impressed with the exchange defense attorneys had with Easley during the clemency procedure. “He was very engaged with us,” he said.

Easley has made no ruling on whether he will grant clemency to Powell. Typically, Easley rules on such requests on the day before an execution is scheduled to take place.

State v. Powell, 459 S.E.2d 219 (N.C. 1995) (Direct Appeal).

Defendant was convicted in the Superior Court, Cleveland County, Robert E. Gaines, J., of first-degree felony murder and was sentenced to death. Defendant appealed. The Supreme Court, Whichard, J., held that: (1) any error in admitting statements made by defendant after Miranda waiver form was destroyed was harmless; (2) conversations of defendant taped by third parties were admissible; (3) rulings on voir dire of jurors were proper; (4) testimony of witnesses as to defendant's motive was admissible; (5) error in not allowing defendant's character evidence was harmless; (6) defendant was not entitled to mistrial after outburst of spectators when verdict was read; (7) instructions were correct; (8) prosecutors statements were not grossly improper; (9) prospective jurors were properly dismissed for cause; and (10) imposition of death sentence was not disproportionate. Affirmed.

WHICHARD, Justice.

Defendant was convicted of the first-degree murder of Mary Gladden, an employee of The Pantry on Charles Road in Shelby, and sentenced to death. He appeals from his conviction and sentence. We conclude that defendant received a fair trial, free of prejudicial error, and that the sentence of death is not disproportionate.

The State's evidence tended to show that the victim was killed on 31 October 1991 while on duty at The Pantry. Scott Truelove testified that he bought five dollars' worth of gasoline there between 3:15 and 3:30 a.m. on 31 October. At the counter he stood near a rough-looking man with unkempt, shoulder-length hair, facial hair, and a tattoo on his left forearm. The next morning Truelove read about the murder and gave a description of the man to Captain Ledbetter of the Shelby Police Department. On 16 November 1991 Truelove identified defendant as the man by picking him out of a photographic lineup. On 31 October 1991 Clarissa Epps stopped at The Pantry to buy gasoline at approximately 4:15 a.m. She went in to pay for her purchase. After waiting in vain for a clerk to appear, Epps called out but received no answer. Epps then turned and saw the victim lying in blood behind the counter. Epps drove home and called the police.

Officer Mark Lee of the Shelby Police Department arrived at The Pantry at 4:26 a.m. on 31 October in response to a radio dispatch. Lee first ensured that all customers had left the store and then found the victim behind the counter. She was lying on her back in a pool of blood with her head toward the cash register and her hands at her sides. Lee noticed injuries to the victim's left eye and ear as well as other injuries to her head. He also saw a one-dollar bill on the floor near her left foot and another on the counter.

Mark Stewart, an employee of The Pantry, testified that he worked on 27 October and 1 November 1991. On 27 October Stewart saw a tire tool behind the counter to the side of the cash register. The tool had lain there for approximately one year. It was curved on one end with a round hole for a lug nut and was split on the other end for hubcap removal. Stewart noticed that the tool was missing when he worked on 1 November, the day after the murder.

Thomas Tucker, a district manager of The Pantry, testified that he arrived at The Pantry sometime after 6:00 a.m. on 31 October. He examined the cash register tape for that morning; it showed, among other transactions, a gasoline sale of five dollars at 3:29 a.m. and a no-sale at 3:35 a.m. The cash register enters a no-sale when it is opened but no purchase is made. According to the tape, no transaction occurred between the five-dollar purchase and the no-sale. Tucker opened the register at 6:22 a.m. at the direction of Captain Ledbetter to determine whether any money had been taken during the homicide. He concluded that approximately forty-eight dollars were missing.

On 16 November 1991 Lieutenant Mark Cherka and Officer David Lail drove to Anthony's Trailer Park to find defendant and bring him to the police station for questioning. Defendant came out of a trailer and allowed Cherka to take four photographs of him. Defendant agreed to accompany Cherka and Lail to the police station for questioning as a possible suspect in the murder. Defendant was not under arrest at that time; the officers told him he did not have to leave with them.

They arrived at the police station at approximately 4:00 p.m., and Cherka began to question defendant. Defendant refused to allow Cherka to tape record the interview, so Cherka made notes of what transpired shortly after the interview ended. Defendant stated that he had gone to sleep at around 4:00 a.m. on 31 October after drinking with Don Weathers and defendant's girlfriend, Lori Yelton. Later that morning Yelton and defendant took Weathers to the hospital because he had cut himself at some point during the previous night. Cherka left the interview room and related defendant's statement to Ledbetter. While Cherka had been questioning defendant, Truelove had identified defendant from a lineup containing thirty-two photographs as the man he saw in The Pantry on 31 October. Ledbetter informed Cherka of the identification and then accompanied Cherka back into the interview room.

Defendant again indicated he did not want to be tape recorded, and Ledbetter complied. Ledbetter told defendant about Truelove's identification and asked defendant if he wanted an attorney. Defendant stated that he had not killed anyone and did not want an attorney. Ledbetter advised defendant of his Miranda rights, and defendant signed a waiver of those rights. Defendant continued to deny involvement in the murder.

Ledbetter then told him he knew he had killed the woman and asked, "Why did you kill her?" Defendant hung his head and answered, "[S]he slapped me and I went off on her." Defendant then asked to speak to Ledbetter alone; Cherka left the room. Ledbetter again asked defendant why he had killed the victim. Defendant stated that she had slapped him, he had panicked, he had not intended to harm her, and he merely wanted the money from the cash register.

Defendant then indicated that he wanted to speak to Ledbetter off the record and asked Ledbetter to tear up the Miranda waiver form, which Ledbetter did. Defendant related additional details about the crime, including information about the weapon he had used, after Ledbetter ripped the form into four pieces. At about 6:00 p.m. defendant asked for a lawyer, and one was contacted for him. Defendant was arrested and taken into custody after he conferred with his lawyer.

Defendant testified that he did not read the Miranda waiver form, but signed it because he felt "agreeable" from cocaine he had ingested. He further testified that Ledbetter suggested they talk off the record. On cross-examination he admitted he had given Miranda warnings during his tenure in law enforcement; he recited the warnings on the witness stand. He also admitted he had not mentioned in his pretrial affidavit that Ledbetter proposed that they talk off the record.

Billy Joe Sparks testified that sometime after the murder he had a conversation with Paul Barnard, who called himself Rambo. During the conversation Rambo sniffed glue and both men drank beer. Rambo told Sparks he had killed a woman at a supermarket by beating her to death. Rambo died before defendant's trial; Sparks did not tell the police about Rambo's statement until after Rambo's death.

Johnny Smith, the operator of a local entertainment center, testified that he had spoken to Truelove about the murder. Smith stated that Truelove told him he had seen a man with red hair in The Pantry on the day of the murder.

In rebuttal the State recalled Truelove. He testified that he knew Rambo and that the lineup from which he identified defendant contained a photograph of Rambo. Truelove never picked Rambo as the person he saw at The Pantry on 31 October. Truelove also testified that he remembered having a conversation with Smith about becoming an uncle, not about the murder. Truelove and his sister both have red hair, and his sister had recently given birth to a baby with red hair.

The State also called Officer James Glover of the Shelby Police Department in rebuttal. Glover testified that Rambo claimed to be a Vietnam veteran and to have a black belt in karate; neither claim was true. Before his death Rambo had telephoned Glover and told him he had lied to Sparks about committing the murder. Rambo told Sparks he had killed a woman only to maintain his street image.

At sentencing the State relied on the evidence it presented at the guilt/innocence phase. Defendant's evidence showed that defendant was raised in a loving family, had worked as a jailer and with the fire department, and was well-liked and not violent. Dr. Terrence Onischenko, an expert in psychology and neuropsychology, testified that he performed comprehensive testing of defendant on 22 November 1992. The results showed that defendant's memory, problem-solving skills, and motor functions are impaired. Defendant scored in the average range on other tests. Dr. Onischenko also testified that defendant has an increased chance of developing Alzheimer's disease as well as other organic diseases. Defendant's abuse of cocaine and alcohol probably caused his brain dysfunctions. Defendant has an average IQ and normal concentration skills, language functions, sensory ability, and visual ability.

Defendant also presented evidence showing that he took good care of his son, who is profoundly mentally retarded and autistic. Defendant implemented the programs devised for his son's development and served on the advisory council of the parent-teacher organization at his son's school. Two jailers at the Cleveland County jail testified that defendant had adjusted well to life as an inmate and had caused no problems.

The jury found defendant guilty of first-degree murder under the felony murder rule, with robbery with a dangerous weapon as the underlying felony. At sentencing the jury found one aggravating circumstance, that the murder was committed for pecuniary gain, and no mitigating circumstances. It unanimously recommended that *686 defendant be sentenced to death; the trial court sentenced defendant accordingly.

* * *

We thus cannot conclude that the death sentence was aberrant, capricious, or disproportionate.

NO ERROR.

Powell v. Lee, 282 F.Supp.2d 355 (4th Cir. 2003). (Habeas)

Following affirmance of his first-degree murder conviction and death sentence on direct appeal, 340 N.C. 674, 459 S.E.2d 219, and denial of state post-conviction relief, petitioner sought writ of habeas corpus. The District Court, Thornburg, J., held that: (1) counsel did not render deficient performance during capital murder sentencing hearing; (2) petitioner was not entitled to peremptory instruction on certain mitigating factors, and thus counsel was not deficient in failing to request instruction; (3) death sentence based on aggravating factor that murder was committed for pecuniary gain did not violate Eighth Amendment; (4) state's pretrial disclosures satisfied Brady rights; and (5) any error in admitting statements allegedly made "off the record" was harmless beyond reasonable doubt.

Petition denied.

THORNBURG, District Judge.

I. PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND

On April 29, 1993, the sentence of death was imposed on the Petitioner by the same jury that two days earlier had found him guilty of first degree murder under the felony murder rule. On direct appeal, the North Carolina Supreme Court concluded "that defendant received a fair trial, free of prejudicial error, and that the sentence of death is not disproportionate." State v. Powell, 340 N.C. 674, 682, 459 S.E.2d 219, 222 (1995). Petitioner's petition for a writ of certiorari to the United States Supreme Court was denied in January 1996. Powell v. North Carolina, 516 U.S. 1060, 116 S.Ct. 739, 133 L.Ed.2d 688 (1996).

On April 22, 1997, the Petitioner filed a motion for appropriate relief (MAR). During that proceeding, litigation occurred concerning discovery from the State and the scope thereof. In June 1997, the Petitioner's motion for discovery was denied and an order was entered summarily denying the MAR. On September 30, 1997, the North Carolina Supreme Court temporarily stayed the Petitioner's execution date and the dismissal of his MAR. On July 29, 1998, the state Supreme Court granted the petition for writs of certiorari and supersedeas for the limited purpose of remanding the case for reconsideration of the MAR. State v. Powell, 348 N.C. 697, 511 S.E.2d 654 (1998). The State's response to this remand was a request for a ruling without an evidentiary hearing and summary dismissal. On October 15, 1998, that motion was granted and the Petitioner moved to vacate the dismissal. On July 1, 1999, the state court vacated the October 1998 order of dismissal and found the Petitioner was entitled to an evidentiary hearing. The State's petition to the North Carolina Supreme Court for a writ of certiorari was denied in October 1999. State v. Powell, 540 S.E.2d 745 (N.C.1999).

Discovery hearings were conducted in February, March and April of 2000. On March 27, 2000, the Petitioner amended his MAR and an evidentiary hearing was conducted in June 2000. On June 27, 2001, both the MAR and amended MAR were denied. Petitioner's petition for a writ of certiorari was denied by the State Supreme Court on December 19, 2002. State v. Powell, 356 N.C. 621, 575 S.E.2d 520 (2002). This action was filed three days later.

II. STATEMENT OF FACTS AT TRIAL

Mary Gladden was the evening shift clerk at The Pantry on Charles Road, Shelby, North Carolina, on October 31, 1991. Powell, 340 N.C. at 682, 459 S.E.2d at 222. Scott Truelove (Truelove) purchased gasoline from the store around 3:15 a.m. that morning. Id. While paying at the counter, he stood near "a rough-looking man with unkempt, shoulder-length hair, facial hair, and a tattoo on his left forearm." Id. That same morning, Clarissa Epps stopped to buy gasoline from the store around 4:15 a.m. Id. After waiting to pay inside the store, she called out but no one answered. Id. Epps then saw the victim lying behind the counter. Id. Epps drove home and called the police. Id.

The investigating officer found the victim lying on her back "in a pool of blood" with injuries to head and left eye and ear. Id. An autopsy revealed that her skull had been fractured in several places, her nose was broken, and her left eye had been displaced by a fracture to the bone behind it. Id. Death had been caused by blunt trauma and she died from that trauma before she lost a fatal amount of blood. Id.

On November 16, 1991, the Petitioner voluntarily accompanied officers to the police station for questioning despite being told he was not under arrest and did not have to go with them. Id., at 683, 459 S.E.2d at 223. The Petitioner signed a Miranda [FN1] waiver during the interview. When the interviewing officer asked, "Why did you kill her?," the "Defendant hung his head and answered, '[S]he slapped me and I went off on her.' " Id., at 684, 459 S.E.2d at 223. Petitioner also stated that he had not intended to hurt her; he had only come in to rob the store. Id.

Don Weathers (Weathers) testified that on the evening before the victim was murdered, he, the Petitioner and the Petitioner's girlfriend, Lori Yelton (Yelton), were at his apartment and had been drinking "quite a bit." Respondents' Exhibit B4, at 1328. Sometime after midnight, he was cut with a knife so badly that he had to have stitches. Id.

Yelton testified that she began living with the Petitioner in April 1991. Id., at 1395. At that time, and throughout the time she lived with the Petitioner, Yelton used a gram of cocaine each day. Id., at 1397. However, neither she nor the Petitioner worked during this time and the Petitioner's only source of income was disability income received on behalf of his son. Id., at 1402. This income stopped in August 1991 when the child began living with his mother. Id. In September and October 1991, the electricity in Petitioner's apartment was disconnected due to nonpayment and Yelton and the Petitioner would often stay at Weathers' apartment. Id., at 1403. During this time period, Yelton and the Petitioner used cocaine together every day. Id., at 1405. On the evening of October 30, 1991, she and the Petitioner used cocaine all day until about 9:00 or 10:00 p.m. when they exhausted their supply, Id., at 1407.

During the sentencing phase of the trial, defense counsel presented the testimony of Dr. Terrence Onischenko, an expert in psychology and neuropsychology, who opined that the Petitioner's abuse of cocaine and alcohol had caused organic brain dysfunction. Powell, 340 N.C. at 685, 459 S.E.2d at 224; Respondents' Exhibit B5, at 1773, 1776. Dr. Onischenko also testified that Petitioner's history of cocaine and alcohol abuse could "impair judgment, reasoning and logic[.]" Id., at 1776. "He has a brain dysfunction and in combination with any kind o[f] alcohol or substance abuse, the tendency is for these people to be more confused, impaired and dysfunctional." Id., at 1777. He testified that the Petitioner was within the normal range on some of the tests that evaluated elements of judgment and reasoning; however, in other areas of neuropsychological skills, he was grossly impaired. Id., at 1786. When asked how long the Petitioner had experienced this condition, the doctor responded that although it was "hard to say," it was something which had chronically developed; "it's not something that happened overnight or recently." Id., at 1787. Evidence was also presented that the Petitioner had been a good care-giver to his profoundly retarded and autistic son. Powell, 340 N.C. at 685, 459 S.E.2d at 224 .Despite this evidence, the jury found no mitigating factors and concluded the murder had been committed for pecuniary gain. Id.

A witness named Billy Joe Sparks testified "that sometime after the murder he had a conversation with Paul Barnard, who called himself Rambo." Id., at 684, 459 S.E.2d at 223. While the two men drank, Rambo "told Sparks he had killed a woman at a supermarket by beating her to death." Id. Rambo died before the Petitioner's trial. Id. Officer James Glover of the Shelby Police Department testified on rebuttal that Rambo was known for fabricating a story that he was a Vietnam veteran with a black belt in karate. Id., at 685, 459 S.E.2d at 224. The officer further testified that Rambo had called him prior to his death and admitted that he "had lied to Sparks about committing the murder [in order] to maintain his street image." Id.

Commander Dale Ledbetter (Ledbetter) of the Shelby Police Department testified during the Petitioner's trial. On November 3, 1991, he prepared a photographic line-up at the police station which was admitted into evidence at trial as State's Exhibit 2. [FN2] Respondents' Exhibit B4, at 1154. The photograph placed in position number 3 was of Michael Bailey, a man who had been corresponding with the deceased victim by mail. Id., at 1155. The purpose of the photographic array, which *360 was shown to Truelove, was to eliminate Bailey as a suspect. Id. Truelove saw the array, which did not contain the Petitioner's photograph, at about 3:00 p.m., on November 3, 1991, and he did not make any identification. Id., at 1155-56. Because Bailey was in custody in another state and had not been identified by Truelove, his photograph in slot number 3 was removed.

FN2. Ledbetter testified that Exhibit 2 appeared exactly as it had on the date that Truelove saw it except that the photograph in slot number 3 had been removed after Truelove's inspection. Id., at 1155.

On November 16, 1991, Ledbetter asked Truelove to view another photographic array which was introduced at trial as State's Exhibit 3. Id., at 1156. This array contained 32 photographs, including that of the Petitioner which was in slot number 14. Id. The positions of each of the photographs in Exhibit 3 as admitted at trial were exactly the same as on the day that Truelove saw the array. Id., at 1157. Truelove pointed to number 14 and stated that it was that person who looked the most like the person in The Pantry on the evening of the murder. Id. Another officer asked if Truelove was sure and he replied, "I'm 100% sure that's the man that was in The Pantry that night that I purchased gas." Id., at 1158. Truelove did state that some of the individuals in the array had similarities to the person he had seen in the store. Id., at 1166. Weathers was among the individuals whose photographs were in the array. Id., at 1164.

In addition to the November 3 and 16, 1991, line-ups, Truelove was shown a third array on November 2, 1991. Id., at 1165, 1250. That array, which was compiled by Officer Larry Linnens, contained eight photographs including one of the Petitioner which had been taken in 1977. Id., at 1250-51. When shown the array, Truelove stated that no one in any of the photographs looked like the man he had seen in the store. Id., 1253.

During the pretrial proceedings, Petitioner's defense attorneys were shown the November 16, 1991, line-up at the police station. Id., at 1182-83. By mistake, the line-up shown to defense counsel contained both photographs of the Petitioner; however, the line-up actually identified by Truelove contained only the photograph taken of the Petitioner on November 16, 1991, at his trailer park before he accompanied the officers to the police station. Id., at 1183.

During the trial, Truelove made an in-court identification of the Petitioner. Id., at 1269. He also reviewed State's Exhibit 3 and testified that the photograph in slot number 14 was the photograph which he identified on November 16, 1991, as the Petitioner. Id., at 1274-75. Truelove testified that it did not take him any time to recognize the Petitioner and he told the officers that he was "100% sure that was the man I s[aw] in The Pantry that night." Id., at 1276-77. Truelove also testified that the man he saw that night had a tattoo on his left forearm. Id., at 1312-13. The Petitioner had a tattoo on his left forearm. Id., at 1314.

Commander Ledbetter also testified during a suppression hearing held in April 1993 prior to the trial. He spoke to the Petitioner on November 16, 1991, around 5:00 p.m., after the Petitioner accompanied other officers to the police station. Respondents' Exhibit A1, at 90, 92. Before he began speaking with the Petitioner, Ledbetter had learned that Truelove had identified the Petitioner from a photographic array. Id., at 95. Ledbetter told the Petitioner that he had been identified as being at the store around the time of the murder and that as a result, he "needed to advise him of his constitutional rights." Id., at 97. The Petitioner volunteered that he had not killed anyone. Id. Ledbetter began reading the Miranda rights to the Petitioner. Id. After reading it to the Petitioner, Ledbetter slid it toward the Petitioner and he signed it, although Ledbetter struck out the word "accused" and left the word "suspect" open. Id., at 99. Lieutenant Cherka witnessed the signatures. Id., at 100. At that time, Ledbetter said, "Bugs [FN3], I know you killed this woman. Why did you do it? That's all I want to know is why? He dropped his head, mumbled a few words, looked up at me and sa[id], "I slapped her. She slapped me, and I went off on her." Id., at 101-02 (footnote added). After making this statement, the Petitioner said he wanted to go off the record and asked if he could speak with Ledbetter alone. Id., 102-03. The Petitioner then said that "Ms. Gladden slapped him; that he panicked and just wanted to get out of there and he did not intend to hurt the lady; all he wanted was the money." Id. Cherka then left. Id., at 102. The Petitioner then asked Ledbetter to tear up the Miranda warning and he did so. Id., at 104.

FN3. This was apparently a nickname for the Petitioner.

Mr. Powell indicated that he had taken Mr. Weathers' truck and had driven it down to The Pantry for the purpose of getting money; that he went inside The Pantry. He remembers a person coming in there; he does not know the person's name nor what he looks like, but he does remember a person coming in there while he was there purchasing gas. That he went behind the counter in an attempt to get the money and the lady fought him over the money. The he picked up something from behind the counter and began to hit this lady. [A]ll he wanted to do was get out of there but she kept holding on with him and he panicked and just went off on her.

Id., at 104-05. The Petitioner then told him where he had thrown the murder weapon on his way back to Weathers' apartment. Id. "Right at the last is when he said, 'Do you think I need an attorney?' I said, 'I think you do.' " Id., at 106. Ledbetter testified repeatedly that the Petitioner was sober during the interview, understood the questions and knew what he was doing.

III. STATEMENT OF FACTS AT THE MAR HEARING

Dr. Onischenko also testified at the hearing on the Petitioner's motion for appropriate relief (MAR). Respondents' Exhibit KK1, at 10-80. In his opinion, at the time the capital felony was committed, the Petitioner had a pattern of neuropsychological dysfunction caused by alcohol and cocaine abuse. Id., at 46-47. He also testified that if, in fact, the Petitioner had been abusing those substances on the day of the crime, he would be more prone to act impulsively and angrily. Id., at 51-52. In addition, the Petitioner's ability to appreciate the criminality of his conduct and to conform his conduct would have been impaired. Id., at 55-56. Nonetheless, Dr. Onischenko had told defense counsel during the trial that he "was not in any position to make a comment about this individual on that day of a conduct of the alleged criminal act and what his mental status [was] at that time. Obviously, it would depend on a lot of factors including how much alcohol and/or cocaine was consumed, et cetera." Id., at 50.

Dr. Roy Matthew, a psychiatrist with a specialty in addiction, performed an evaluation of the Petitioner in connection with the MAR. Id., at 101. At the time of the offense, the Petitioner had an addiction to multiple drugs and was, in Dr. Matthew's opinion, on a cocaine binge. Id., at 104. The crime occurred at the end of a three-day cocaine binge during which the Petitioner had been taking cocaine intravenously. Id., at 106. When a person is on such a binge, he can only focus on obtaining more cocaine. Id., at 110. Cocaine *362 makes an abuser very irritated, suspicious, and paranoid. Id., at 111. This situation was worsened by the fact that the Petitioner was also a Xanax abuser and had taken two milligrams of Xanax before the crime occurred. Id., at 112. Xanax removes a person's normal inhibitions. Id.

Ali Paksoy, one of the Petitioner's trial attorneys, testified at the MAR hearing that, although he could not specifically recall, he may not have asked Dr. Onischenko about mitigating factors by using the statutory language. Id., at 80, 193-94. It was, however, his recollection that he requested the submission to the jury of those mitigating factors. Id. In addition to his trial testimony, Dr. Onischenko had been retained to testify at the suppression hearing

to show the effects of cocaine abuse and alcohol abuse on his ability to make an intelligent, understandingly voluntary statement to police and how it would affect that. We also wanted to present evidence of his cocaine addiction or cocaine use and how it affected his mental capacity[,] his capacity to appreciate what he did and his condition at the time and his mental or emotional disturbance. We felt all along and as part of our strategy that "Bugs"--throughout his life[,] we had no indication that he had ever been a violent person until he got mixed up with cocaine and with this Lori Yelton. And we felt he made a very bad, serious mistake but he wasn't a bad person and we wanted to show, we wanted to show the cocaine use; we wanted to show his life history up to the point of having been a police officer and all the good he had done, especially for his handicapped child. And this mistake, although bad, shouldn't lead to his death but to life in prison. And we wanted to show his cocaine use but we really wanted to avoid showing that he had voluntarily used cocaine over a nine month period and show that, I think Dr. Onischenko's testimony was that it would tend to make him violent. And we kind of wanted to stay away from that in front of the jury. We didn't really feel how the voluntary use of cocaine and alcohol over this period would be seen. We wanted to show how it affected his mental state. But I did[ ] want to stay away from the violent aspect of it and focus on his life and all the good he had done.

Id., at 196-97.

The Petitioner's second trial counsel, Ralph Gilbert, also testified at the MAR hearing that, "We were dancing around the issue of [the Petitioner's] cocaine--his voluntary cocaine use and the--as we understood it, his propensity, when he was using cocaine, to be violent."

* * *

Petitioner's petition for a writ of habeas corpus is hereby DENIED.

THIS MATTER is before the Court on the Petitioner's petition for a writ of habeas corpus pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2254. Respondents have filed both a motion for summary judgment and a response to the petition. The parties have submitted portions of the record for review as well as legal briefs. The undersigned concludes the record is adequate and finds an evidentiary hearing is unnecessary. Rule 8(a), Rules Governing Section 2254 Cases in the United States District Courts. For the reasons stated herein, the petition is denied.