Executed June 15, 2010 06:10 p.m. CDT by Lethal Injection in Texas

28th murderer executed in U.S. in 2010

1216th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

13th murderer executed in Texas in 2010

460th murderer executed in Texas since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(28) |

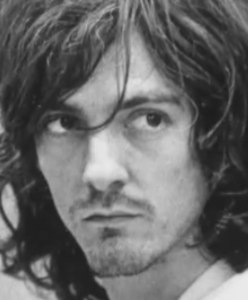

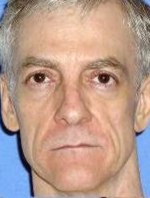

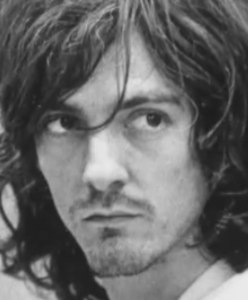

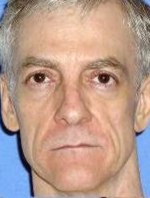

David Lee Powell W / M / 27 - 59 |

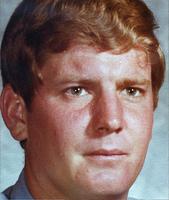

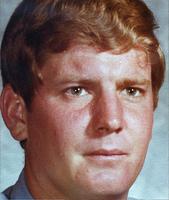

Ralph Ablanedo OFFICER H / M / 26 |

Machine Gun |

11-21-91 03-06-99 |

Powell's background was different from most other capital murder defendants. He graduated from high school a year early and was both the valedictorian and "most likely to succeed" of his small rural school class. He was accepted into the honors program at the University of Texas. While there, he became an anti-war protester and began using drugs. He never finished college. By 1978, he was a heavy user and dealer of methamphetamine. Powell was one of only twelve prisoners remaining on Texas' death row who committed their capital offenses in the 1970's. He was the longest-serving inmate executed in Texas since the state resumed carrying out executions in 1982.

Citations:

Powell v. State, 742 S.W.2d 353 (Tex.Crim.App. 1987). (Direct Appeal)

Powell v. Texas, 492 U.S. 680, 109 S.Ct. 3146 (1989). (Direct Appeal - Reversed)

Powell v. State, 897 S.W.2d 307 (1994). (Direct Appeal - Reversed)

Powell v. Quarterman, 283 Fed.Appx. 186 (5th Cir. 2008). (Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

Four eggs, four chicken drumsticks, salsa, four jalapeno peppers, lettuce, tortillas, hashbrowns, garlic bread, two pork chops, white and yellow grated cheese, sliced onions and tomatoes, a pitcher of milk and a vanilla shake.

Last Words:

None.

Internet Sources:

Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Executed Offenders (Powell)

Powell, David Lee

Date of Birth: 1/13/51

DR#: 612

Date Received: 10/6/78

Education: 16 years

Occupation: Laborer

Date of Offense: 5/18/78

County of Offense: Travis

Native County: Brazos

Race: White

Gender: Male

Hair Color: Brown

Eye Color: Brown

Height: 5' 10"

Weight: 140

Prior Prison Record: None.

Summary of incident: Powell was convicted and sentenced to die for the May 18, 1978 machine gun slaying of police officer Ralph Ablanedo, 26. Ablanedo, who had stopped a car for a traffic violation was struck at least four times by bullets from a Russian AK-47 machine gun. Though mortally wounded, Ablanedo reached his radio in time to call for help and describe his assailant. He died shortly afterward in a hospital.

Co-Defendants: None.

Tuesday, June 8, 2010

Media Advisory: David Lee Powell scheduled for execution

AUSTIN – Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott offers the following information about David Lee Powell, who is scheduled to be executed after 6 p.m. on Tuesday, June 15, for the 1978 slaying of Austin police Officer Ralph Ablanedo.

FACTS OF THE CRIME

On the evening of May 17, 1978, Austin police Officer Ralph Ablanedo stopped a car and issued a citation to the driver for failing to display a driver’s license. Ablanedo asked the dispatcher to check for local warrants on the driver and passenger David Lee Powell. The dispatcher found no warrants on the driver.

As the car pulled away, Ablanedo learned from the dispatcher that there was a possible warrant on Powell for misdemeanor theft. Ablanedo stopped the vehicle again, and as the officer approached the driver, Powell shot at the officer through the car’s back window with an AK-47, knocking him to the ground. The weapon was set to semi-automatic mode, which required him to pull the trigger more than once. Powell switched to automatic mode and fired at Officer Ablanedo again, knocking the officer to the ground a second time. The car then left.

Meanwhile, the dispatcher on learning that there was a possible arrest warrant on Powell, had sent another police officer to check on Ablanedo. When the officer arrived at the scene a few minutes later, he found Ablanedo lying on the ground. Ablanedo told the officer that he had no chance to pull his weapon. Although Ablanedo had been wearing a bullet-proof vest, it was not designed to withstand fire from an automatic weapon. Ablanedo suffered ten gunshot wounds and died on arrival at the hospital.

Other police officers tracked Powell’s car to an apartment complex parking lot. Powell fired on the officers with his AK-47 from inside the vehicle and threw a live hand grenade in the direction of the officers and then fled from the car. The hand grenade did not explode because Powell had not removed all of the safeties.

Police arrested Powell in the early morning hours in some bushes on the grounds of a nearby school. They also discovered a .45 caliber automatic pistol hidden under shrubs on the grounds as well as Powell’s backpack, containing seven packages of high-grade methamphetamine. Further investigation revealed that Powell had fired at least twenty-three rounds of ammunition, and police uncovered fifteen live rounds in Powell’s car. Police also retrieved from Powell’s car a book entitled Book of Rifles, tabbed at pages discussing a Soviet AK-47 rifle. The book contained loose notes in Powell’s handwriting about different types and models of weapons and notes referring to other books on weapons. Books and notes regarding guerrilla warfare and a pair of handcuffs were also found in the car.

A search of Powell’s residence led to the discovery of another hand grenade, additional weapons and ammunition, more books and manuals on weaponry and combat, the components of a methamphetamine lab, and three vials of methamphetamine.

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

On September 28, 1978, Powell was convicted and sentenced to death by a Travis County jury for capital murder.

On July 8, 1987, The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed his conviction and sentence on direct appeal.

On June 30, 1988, the U.S. Supreme Court vacated the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals’ judgment and remanded the case.

On January 11, 1989, The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals once again affirmed Powell’s conviction and death sentence.

On July 3, 1989, The United States Supreme Court reversed Powell’s conviction.

On November 21, 1991, Powell was convicted and sentenced to death a second time,

On December 7, 1994, The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the conviction on direct appeal, but vacated the death sentence.

On Oct 2, 1995, Powell’s petition for writ of certiorari to the U.S. Supreme Court, appealing the affirmation of his conviction was denied.

On March 6, 1999, after a third punishment trial, Powell was again sentenced to death.

On January 16, 2002, Powell’s death sentence was affirmed by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals on direct appeal

On November 4, 2002, The U.S. Supreme Court denied certiorari review.

On September 25, 2002, The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals also denied Powell’s application for writ of habeas corpus.

On April 16, 2008, the U.S. District Court denied a federal petition for writ of habeas corpus.

On July 16, 2008 the U.S. Court of Appeals granted a certificate of appealability, but affirmed the denial of habeas relief.

On March 23, 2009, The U.S. Supreme Court denied Powell’s subsequent petition for writ of certiorari on March 23, 2009.

On September 30, 2009 a second application for state habeas was dismissed by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals.

PRIOR CRIMINAL HISTORY

Powell’s capital murder conviction is his only conviction. However, he was previously arrested for the following offenses: auto theft in Travis County; auto theft and possession of dangerous drugs in Travis County; obscenity in New Orleans, Louisiana; and petty theft in Travis.

Texas Execution Information Center by David Carson.

David Lee Powell, 59, was executed by lethal injection on 15 June 2010 in Huntsville, Texas for killing a police officer at a traffic stop.

On the evening of 17 May 1978, Austin police officer Ralph Ablanedo, 26, pulled over a vehicle for not displaying a rear license plate. The driver, Sheila Meinert, 27, got out of the car and approached him. She told him she had lost her driver's license, but she showed him her passport. The officer asked the dispatcher by radio to check Meinert and her passenger, David Powell, 27, for outstanding warrants. The dispatcher informed Ablanedo that the computers were not functioning properly, but that there were no local warrants for Meinert. Ablanedo issued Meinert a citation for the license plate and allowed her to drive away. As she was pulling out, however, the dispatcher told Ablanedo that Powell had a possible warrant for misdemeanor theft. The dispatcher called for officer Bruce Mills, Ablanedo's partner, to go out to back up Ablanedo.

Ablanedo stopped the vehicle again. As he was approaching the car, and Meinert was walking toward him, Powell shot at the officer through the back window with an AK-47 machine gun. Initially, the weapon was set to semiautomatic mode. Ablanedo tried to get up, but Powell switched the weapon to full automatic mode fired at him again. The car then left.

Officer Mills arrived a few minutes later. Ablanedo had been shot ten times. Despite the fact that he was wearing a bulletproof vest, it was not designed to withstand fire from automatic weapons. Ablanedo told Mills what happened and said he had no chance to draw his weapon. He died on the operating table of the hospital about an hour after he was shot. Officers tracked Powell's car to an apartment complex parking lot. Powell fired on them from inside the vehicle, but no one was hit. Meinert was arrested in the parking lot.

Police arrested Powell in the early morning in some bushes on the grounds of a nearby school. They discovered a .45-caliber semiautomatic pistol and a backpack containing 2 and 1/4 ounces of high-grade methamphetamine hidden under some shrubs. In the car, police discovered a book entitled "Book of Rifles". Pages discussing the AK-47 were tabbed down, and the book contained notes in Powell's handwriting about different types of weapons and other books on weapons. Also in the car were a pair of handcuffs, some ammunition, and books and notes regarding guerrilla warfare.

Back at the apartment complex, officers found a live hand grenade on the ground, about ten feet away from the driver's door of one of the police cars. The grenade did not detonate because, although the pin was pulled out, the safety clip was still in place. A search of Powell's residence uncovered another hand grenade, more guns and ammunition, books on weapons and combat, a methamphetamine lab, and three vials of methamphetamine.

Powell's background was different from most other capital murder defendants. He graduated from high school a year early and was both the valedictorian and "most likely to succeed" of his small rural school class. He was accepted into the honors program at the University of Texas. While there, he became an anti-war protester and began using drugs. He never finished college. By 1978, he was a heavy user and dealer of methamphetamine, and had an arrest record for auto theft, petty theft, and drug possession. He was wanted for passing over 100 bad checks to merchants in the Austin area and had begun carrying around loaded weapons out of paranoia. He had no criminal convictions at the time of the murder.

On the day of Powell's arrest, the trial court, at the state's request, ordered a psychiatric examination to determine his sanity at the time of the offense and competency to stand trial. Dr. Richard Coons and Dr. George Parker conducted the evaluation and determined that Powell was sane and competent.

Bobby Bullard testified that he witnessed Ablanedo's shooting as he was driving home from work. He saw shots fired from the Mustang that knocked out the back windshield. He saw a man sitting in the middle of the front seat, leaning into the back seat. Bullard's description of the man he saw shooting matched Powell's appearance at the time of his arrest. However, Bullard, Officer Mills, others who arrived at the scene, and the doctors who treated Ablanedo all testified that Ablanedo repeatedly said "that damn girl". Witness testimony was also contradictory as to whether Powell or Meinert threw the grenade in the direction of the police car at the apartment parking lot.

In order to impose a death sentence, juries must find not only that the defendant is responsible for capital murder, but also that he poses a future danger to society. At Powell's punishment hearing, Drs. Coon and Parker testified as to his future dangerousness, based on the examination they conducted when evaluating his sanity and competence. A jury convicted Powell of capital murder in September 1978 and sentenced him to death. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the conviction and sentence in July 1987.

Sheila Margaret Meinert was convicted of attempted capital murder for her part in the incident at the apartment parking lot. She was sentenced to 15 years in prison. She was paroled in June 1989. With no arrests after her parole, she was discharged from her sentence in January 2000.

In 1988, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Satterwhite v. Texas that the Fifth and Sixth Amendments guarantee criminal defendants the right to be told in advance that a psychiatric evaluation may be used to determine their future dangerousness, that they have the right to remain silent, and that their counsel must be informed that the evaluation is taking place. Because of the similarities between Satterwhite's case and Powell's, the Supreme Court sent Powell's case back in June 1988 to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals for reconsideration in light of this recent decision.

On review, the Texas court held that Powell waived his right to object to the testimony of Dr. Coons and Parker when his lawyers used psychiatric testimony to argue for an insanity defense. Such an argument, the court reasoned, entitles the state to present psychiatric evidence in refutation. The Court of Criminal Appeals reaffirmed Powell's guilty verdict and death sentence in January 1989. The case then went back to the Supreme Court, which found that while the Court of Criminal Appeals dealt with the Fifth Amendment issue - the right to remain silent - it failed to answer the Sixth Amendment issue - the right to counsel. In July 1989, the Supreme Court vacated Powell's death sentence.

For most of his 32 years on death row, Powell declined interview requests from reporters, while his lawyers attempted with each new hearing to shift as much of the blame for Ablanedo's murder as possible to Sheila Meinert. In December 2009, however, as his appeals began to run out, Powell wrote a letter to the victim's family. "I am infinitely sorry that I killed Ralph Ablanedo," he wrote. "I shot Officer Ablanedo and I take responsibility for his death. In a few frightful seconds, I stole from you and the world the precious and irreplaceable life of a good man ... There is no excuse for what I did."

The week before his execution, Powell's attorneys filed appeals asking that the death sentence be reduced to life in prison. They claimed that in his more than 30 years on death row, Powell was a model inmate who exhibited "exemplary and humane behavior", contradicting the jury's finding that he posed a future danger to society. Prosecutors countered that the juries in 1991 and 1999 considered evidence of Powell's good behavior in prison and still sentenced him to death. State and federal courts rejected the appeals. The Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles also unanimously declined his request for a reduced sentence.

Bruce Mills eventually married Ablanedo's widow, Judy, and adopted their two sons. They and other family members were escorted by Austin police officers to attend the execution.

Powell kept his eyes locked on the victim's family as the execution was being administered, but he did not acknowledge the warden's invitation to make a last statement. He was pronounced dead at 6:10 p.m.

In 1972, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the death penalty law in every state was unconstitutional. Texas commuted the sentences of every death row prisoner and passed a new death penalty statute in 1973. When Powell arrived on death row in 1978, no one had yet been executed under the new law. Since then, 459 prisoners have been executed before him. About half that many have had their sentences commuted or overturned, and 36 have died from other causes. Powell was one of only twelve prisoners remaining on Texas' death row who committed their capital offenses in the 1970's.

Before Powell, the longest time a prisoner served on death row before being executed was 24 years. Robert Excell White killed a store owner and two customers in a robbery in 1974, and was executed in 1999.

Five prisoners have been on death row longer than Powell. Two of them, Raymond Riles and Clarence Jordan, are considered mentally incompetent and ineligible for execution. Ronald Chambers and Anthony Pierce both had their death sentences vacated by the federal courts in 2008, and the state is seeking to have them reimposed. No recent information on the fifth, Harvey Earvin, was available for this report.

"Convicted killer executed in slaying of Austin police officer." by Michael Graczyk. (Associated Press June 15, 2010, 6:56PM)

HUNTSVILLE — A former drug dealer convicted of using an assault rifle to kill an Austin police officer during a traffic stop 32 years ago was executed Tuesday evening.

David Lee Powell, 59, received lethal injection about 30 minutes after the U.S. Supreme Court refused to halt his punishment Tuesday evening.

He was the longest-serving inmate executed in Texas since the state resumed carrying out executions in 1982. He’s also one of the longest-imprisoned in the nation to die. In 2008, a prisoner in Georgia was executed after spending more than 33 years on death row.

Powell’s attorneys had argued unsuccessfully his exemplary behavior on death row over the past three decades showed jurors were wrong when they decided he would be a continuing danger and should die for killing 26-year-old Ralph Ablanedo.

Asked by a warden if he had a final statement, Powell gave no response.

As the drugs began flowing into his arms, he gasped slightly, began snoring quietly, then showed no movement. Nine minutes later, at 6:19 p.m. CDT, he was pronounced dead.

Some 150 retired and active police officers from Austin traveled 135 miles east to Huntsville and waited outside the downtown prison in the 90-plus-degree heat as the punishment was carried out. Several officers in the group knew Ablanedo.

“We’re not here to gloat or to celebrate a death,” Austin Police Department Chief Art Acevedo said. “We’re here to celebrate a life, and that is the life of Officer Ablanedo.”

"Powell executed for 1978 slaying of police officer; Family of Ralph Ablanedo expresses relief after 32-year wait; David Lee Powell makes no final statement," by Tony Plohetski and Chuck Lindell. (Updated: 12:46 a.m. Wednesday, June 16, 2010)

HUNTSVILLE — Declining to make a final statement, David Lee Powell was executed Tuesday for killing an Austin police officer 32 years ago as seven members of his victim's family watched silently from a nearby window.

Strapped to the execution gurney with intravenous lines already inserted, Powell kept his eyes locked on members of officer Ralph Ablanedo's family but did not acknowledge Warden Charles O'Reilly's invitation to speak.

His head still turned toward the window, Powell half closed his eyes as the lethal combination of drugs began flowing at 6:10 p.m.

Powell's death concluded a 32-year case that featured three trials and multiple appeals, agonizing Ablanedo's family but providing Powell's friends and supporters with the slim hope that his execution could be avoided.

One late appeal, filed last week, argued that jurors mistakenly labeled Powell a continuing threat to society, a requirement for imposing the death sentence.

Supporters argued that it was unconstitutional to kill Powell based on information shown to be incorrect after he spent three decades as a model inmate — helping illiterate prisoners learn to read and counseling others on death row.

Travis County prosecutors responded by reminding the courts that jurors in two retrials — ordered after successful appeals in 1991 and 1999 — had already considered evidence of Powell's good behavior and still sentenced him to death.

Texas courts rejected that appeal Monday, as did the U.S. Supreme Court on Tuesday, shortly before Powell's execution.

In addition, Powell lawyer Richard Burr filed an execution-day appeal accusing Travis County District Attorney Rosemary Lehmberg of providing false statements to the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles. The board this month considered Powell's request to have his death sentence reduced to a life term.

The Court of Criminal Appeals denied that claim in the early afternoon, before prosecutors could file arguments denying the allegation.

About 150 current and former Austin police officers traveled to Huntsville for the execution — meeting for lunch in a local hotel to watch a video about Ablanedo's life. Most retired officers were wearing black "Journey to Justice" T-shirts. Some wiped tears from their eyes.

After being escorted to the prison by Huntsville police, the Austin officers assembled in seven lines —those who had worked with Ablanedo stood at the front — to serve as an honor guard for the slain officer's family.

The officers stood at attention and saluted as Bruce and Judy Mills; Ablanedo's 87-year-old mother, Betsy; and other family members were greeted and given hugs by Austin Police Chief Art Acevedo.

Acevedo said later that Ablanedo's relatives were overwhelmed by the display of support.

"They were very touched," he said, adding that the encounter was emotional for him as well.

"When you see his widow and Bruce Mills and his mother start to cry it's hard not to feel their pain," the chief said. "A mother should never have to bury her child."

Once the prison doors closed, the officers broke ranks and milled around.

Suddenly, nearby protesters fired up their microphone: "We are here because in one hour the State of Texas is going to murder David Lee Powell," a voice loudly proclaimed — greeted by cheers from many of the police officers.

"David Powell the 27-year-old drug addict is not the same person as the sober and remorseful 59-year-old man who is being executed today," Nell Warnes, who had visited with Powell since 2004, told protesters later. "From my long-term interaction with David, I am certain that he is no longer a threat to our society."

When it became apparent that Powell was going to be executed, the four dozen protesters, kept about 100 yards from the officers, stood silently.

Powell spent his final day packing personal property — much of it bound and loose papers — into about 10 orange mesh bags for delivery to Huntsville's Hospitality House. Friends can pick up the items there for delivery to his relatives, who were not present in Huntsville.

"Crime and punishment: After 32 years, has Powell's execution lost its meaning?" by Chuck Lindell and Tony Plohetski. (June 15, 2010)

Heavily armed, deeply paranoid and strung out on drugs, David Lee Powell was a nightmare personified in 1978.

Sitting in a car that had been pulled over on a dark Austin side street, Powell sighted his AK-47 through the rear window. Police radios caught officer Ralph Ablanedo's scream as the first bullet penetrated his bulletproof vest. Nine more shots found their mark.

The well-liked father of two young sons died shortly after the 12:30 a.m. attack .

Barring the unexpected, Powell will be executed for that crime on June 15 — 32 years, three weeks and five days after Ablanedo was buried with honors.

Texas has never executed a man after so much time has passed, giving rise to a question that speaks to a basic concept of punishment and justice: Has Powell's execution been robbed of its meaning and purpose?

The clean-cut 59-year-old man who will be strapped to the Huntsville gurney to receive a trio of lethal drugs is nothing like the nightmare from another era. Powell's time in prison long ago removed the methamphetamine taint that helped turn a promising honors student into a jittery, lank-haired killer, and a fiercely loyal group of supporters insists that putting him to death now would be a travesty.

"He's the old David Powell" — intelligent, compassionate, articulate and thoughtful — and no longer poses a danger to society, said attorney David Van Os, who befriended Powell in 1968. "This is not how the death penalty was intended to be used."

But for those most touched by Ablanedo's murder, Powell's execution remains a meaningful — and desired — goal.

Irene Ablanedo, Ralph's sister, plans to stand at the window in the Huntsville death chamber to watch Powell die from five feet away. She will be thinking about her brother, what he meant to his family and how he was taken away too early. The pain of loss still burns.

"I can't wait for that bastard to take his last breath," she said. "That is what he deserves."

For some officers, Powell's death is a matter of fairness — an eye for an eye — that validates their service in a dangerous profession and adds a measure of protection by sending a clear message: If you kill a cop, you die.

More than 100 current and retired Austin police officers — including Ablanedo's friends and some who weren't even born when he died — will drive or take a chartered bus for an execution-day trip to Huntsville, which they're calling the Journey to Justice. Those who can't make it will toast Ablanedo in a downtown Austin bar at 6 p.m., the time set for Powell's execution.

"It is a matter of unfinished business," said retired police Lt. George Vanderhule, who helped Ablanedo's widow plan his funeral. "This has gone on for 32 years, and he has managed to evade justice."

But defense lawyer Richard Burr argues another perspective. Powell, he said, has led an exemplary life in the harsh conditions of death row — teaching illiterate inmates to read, defusing guard-prisoner tensions and offering true friendship to many in the "free world."

"Powell is someone who contributes much more to life than his execution would contribute to the symbolic goal of retribution 32 years after the murder of Ralph Ablanedo," Burr wrote to the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles in hopes of getting Powell's sentence reduced to life in prison.

Speaking recently from death row, Powell said he wants to live. "I think I still have something to offer in this life," he said. But he's also begun preparing for an execution that appears increasingly likely.

Saying he is horrified to have caused Ablanedo's murder, Powell has tried to apologize to the officer's family and to express regret for the pain he caused by "an act that was a betrayal of everything I believed in and aspired to be."

"I had wanted to do it for decades," Powell said of his December 2009 letter to Ablanedo's family. "Although it was obviously too little too late, it seemed like the right thing to do. It seemed like a small, tentative first step towards healing the tear in the social fabric that was caused" by the murder.

'You'll be all right'

It was shortly after midnight on May 18, 1978.

Powell — carrying an automatic rifle with 38 rounds in the clip, a .45-caliber handgun, a hand grenade and $5,000 in methamphetamine — was on his way to Killeen for a drug deal. Girlfriend Sheila Meinert was driving his red Mustang, which was missing its rear license tag.

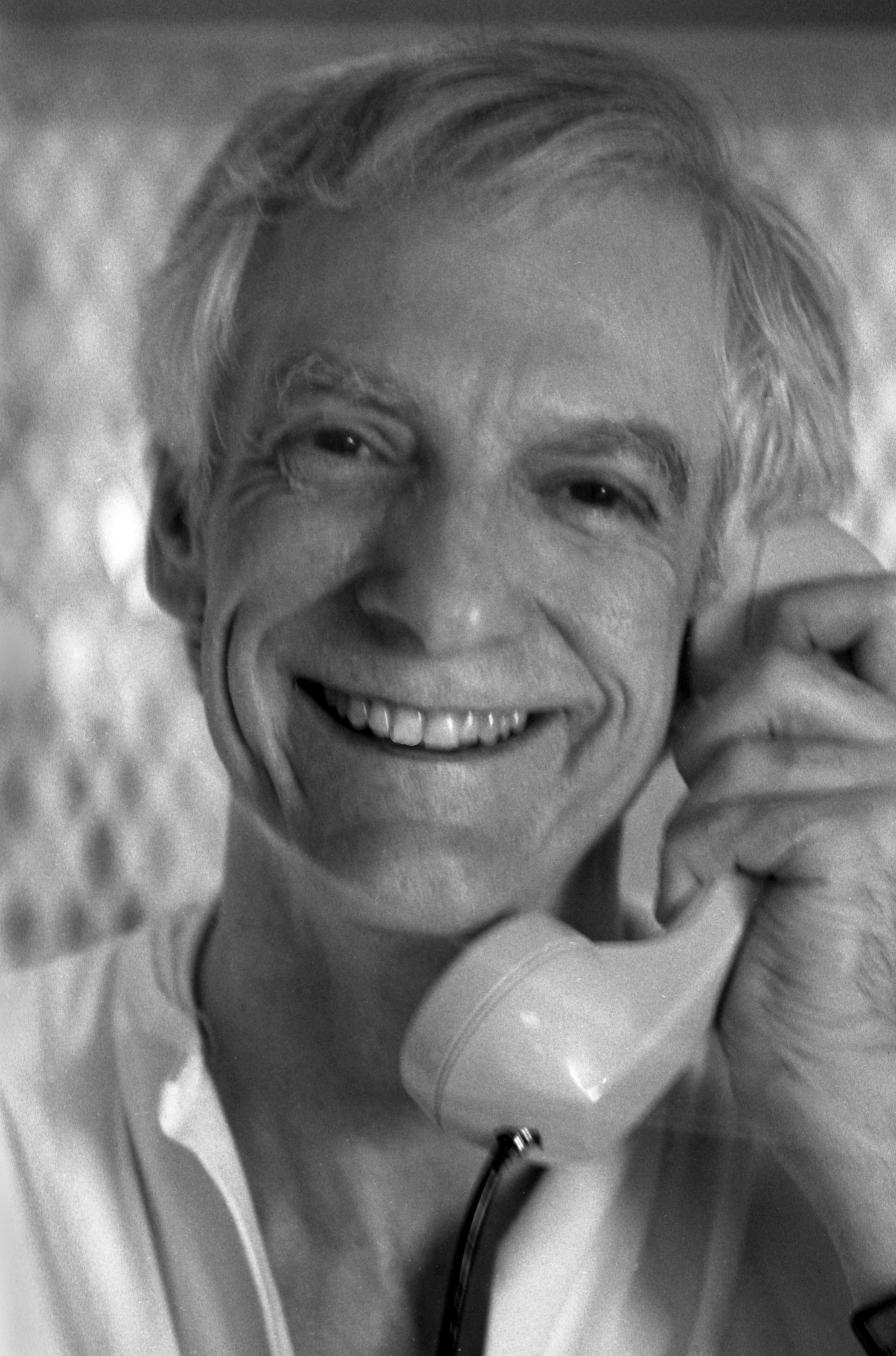

Ablanedo — a five-year officer who loved fishing, married his high school sweetheart and had two boys, ages 5 and 1½ — was patrolling South-Central Austin. He pulled the Mustang over on Live Oak Street and ticketed Meinert. Computer trouble prevented dispatchers from checking on Powell, so the officer let them go.

But before the Mustang had traveled half a block, the computer sprang to life and revealed that Powell was wanted for theft and writing bad checks to dozens of Austin merchants. Ablanedo again signaled Meinert to pull over as the dispatcher alerted officer Bruce Mills to provide routine backup.

Mills heard a scream over the police radio — it sounded like Ablanedo, but he wasn't sure — and arrived a short time later to find his friend bleeding on the street.

"He got me with a shotgun. He got me," Ablanedo told Mills, also describing the weapon as a machine gun.

Trying to sit up, Ablanedo asked how badly he was hurt. Running a hand over his stomach, he felt blood and lay back down.

You'll be all right, Mills replied.

As paramedics arrived, other officers cornered Powell in the parking lot of a nearby apartment complex. Somehow, nobody was hurt in the shootout that followed or when the grenade with a 16-foot kill radius, its pin pulled but a safety device still engaged, failed to explode after being thrown near police.

Meinert was quickly arrested. She served four years of a 15-year sentence for being a party to attempted capital murder. (Now living near Seattle, she hung up on a reporter who recently contacted her by phone.)

Powell ran. Police, believing they had him boxed into a wooded area, sent in six officers and two bloodhounds. Everyone else was told to stay out; anything moving would be considered a target.

About the same time, Ablanedo, 26, died on a hospital operating room table.

Powell, only one year older than Ablanedo, was found hiding in bushes at Travis High School about 4 a.m. and arrested without incident. His capital murder conviction four months later prompted this line in the American-Statesman: "Given the long, complex appeal process that is automatic upon conviction of capital murder, Powell probably will remain in a cell for several years."

It was a lot longer than that. Powell's appeals resulted in two new trials, in 1991 and 1999. Both times, Powell was returned to death row after jurors concluded he still posed a threat to society.

'Not a troublemaker'

Before the death penalty can be imposed — today and when Powell was first convicted in 1978 — jurors must find beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant will probably commit future acts of violence that pose a "continuing threat" to society. Powell's supporters say it's absurd to believe the gentle, intelligent man of 2010 poses any such risk.

While on death row, Powell was disciplined a few times, but only for minor rules infractions such as having too many prison-issued socks or refusing to remove a poster from his cell wall, prison officials said. Four guards and a supervisor, testifying at Powell's 1999 retrial, called the inmate respectful and nonviolent.

"He was very quiet, always well-mannered," Mark Morrow, a 14-year guard, testified. "Not a troublemaker, by any means."

Psychiatrist Seth Silverman of Houston has concluded that Powell poses "virtually no risk" of future violence.

Powell has no history of violence beyond that one horrific act in 1978, understands the string of bad choices that led to Ablanedo's murder and displays a superior intellect that allows him to learn from past mistakes, said Silverman, an expert in addiction and forensic psychiatry, in an affidavit supplied by defense lawyers.

In addition, Powell's age adds an element of safety, Silverman said, pointing to research showing that arrest rates fall 90 percent from age 20 to 60.

Silverman began treating Powell about three years ago when the inmate became convinced that voices from androidlike robots were telling him to commit suicide. Aided by his intellect and ability to form healthy relationships, Powell quickly responded to psychotherapy, and the symptoms disappeared within several months, Silverman said.

Longtime friend Genevieve Hearon of Austin said Powell has kept a remarkably even temperament and displayed consistent concern for others despite living in harsh conditions, including confinement in a 60-square-foot cell since death row moved into new quarters in the Polunsky Unit in 1999.

Hearon's nonprofit, Capacity for Justice, works on behalf of prisoners with disabilities and presented Powell with its first Brothers' Keeper Humanitarian Award in 2008. Powell, she said, helped speed accommodations for deaf and wheelchair-using prisoners at the Travis County Jail, where he was held during his retrials, and worked to connect disabled death row inmates with outside help.

"In all of my contact with him, he's been helping other prisoners," Hearon said.

Van Os, who befriended Powell when they were University of Texas freshmen in 1968, believes Powell could safely be released from prison.

"Everything that is known about David Powell demonstrates that the horrific act of violence that he perpetrated against officer Ablanedo and the Ablanedo family is an anomaly in his life. He is a very peaceful, nonviolent person," said Van Os, a former Austin lawyer who now practices in San Antonio.

"I'm not trying to excuse what he did. I don't excuse it. It was a murder, and it was horrible," Van Os said. "But the death penalty is supposed to be imposed only on a person who's a continuing danger to society and in his case, that is being made into a farce."

'Just really scary'

With details of Ablanedo's murder still fresh in 1978, Travis County prosecutors had little trouble arguing that Powell posed a lasting threat. And during the 1991 and 1999 retrials, with defense lawyers presenting evidence that Powell had appeared to reform while behind bars, prosecutors never wavered.

"I want you to picture the blood of Ralph Ablanedo seeping through his bulletproof vest," prosecutor Robert Smith told jurors in 1991. "David Powell is here because of a character disorder that cannot be rectified."

Lead prosecutor Terry Keel placed Powell's handgun on a table in front of Powell and asked jurors: "Does this make you feel safe? The death penalty is society's self-defense. You have a very manipulative, very dangerous individual here."

Jurors in the 1991 trial deliberated for 10 hours. Nine of those hours were spent on Powell's dangerousness, said Charles Carsner, the jury foreman who still lives in Austin.

The turning point was a psychologist's notes discussing Powell's vision or dream "where he was driving at night on a lonely road, and a cop pulls him over, and he kills the cop," Carsner recalled recently. "It was just really scary."

After jurors in the 1999 retrial came to the same conclusion, Powell's appeals argued that his death sentence was unconstitutional because there is no evidence that he still posed a danger. U.S. Magistrate Judge Andrew Austin disagreed.

"Powell contends that he was 'a different person' when he was retried in 1999. Regardless of whether this court might agree with that statement, the jury was not compelled to accept that contention, and it plainly did not," Austin wrote in 2005, adding that a federal appeals court has "explicitly rejected the argument that improving oneself after committing a heinous crime prevents a jury from concluding that one is a future danger."

Powell supporters remain convinced that such a legalistic argument ignores Powell's character, contributions and contrition.

But Ronnie Earle, the former Travis County district attorney who prosecuted Powell in 1978, is unconvinced.

"There was never any doubt about the applicability of the law and the appropriateness of the sentence. It was an ambush totally out of nowhere," Earle said. "His soul is between him and his own personal higher power. His actions are between him and the law."

'He was a genius'

Powell was a fish out of water when he arrived at UT for the fall 1968 semester.

Described as shy and naive, he came to Austin from his family's 80-acre dairy farm near Campbell, a town of fewer than 500 about 60 miles northeast of Dallas. He had been voted most likely to succeed at Campbell High School and was valedictorian of his 15-member graduating class even after skipping his junior year.

"He was the class nerd; he was a very bright man," former classmate Karen Hair testified at Powell's 1999 trial. "We thought he was a genius. He had very thick glasses, and he walked around with a smile on his face all the time."

His SAT scores were almost perfect, and officials with Plan II, UT's honors program, were excited to have him, UT adviser Donette Moss testified in 1999.

After initial trouble adjusting, Powell's grades and schoolwork improved — but trouble arose during his sophomore year, Moss said. Powell got involved in the anti-war movement and began experimenting with drugs. He dropped out of UT in 1970 and slid deeper into addiction over the next eight years.

In the years before Ablanedo's death, Powell's family was alarmed to find the calm, responsible boy replaced by a flighty, fast-talking man with paranoid delusions. Former friends had trouble recognizing him in his thin, disoriented, disheveled state.

"He called me once and said he had to be careful talking to me because the CIA was after him," uncle Clem Struve said.

"I've had mental illness in my family, and I thought he was having a nervous breakdown," Marjorie Powell, his mother, said recently from her Dallas home. "I called a psychiatrist, different people for help."

Powell, however, disappeared. No amount of searching could turn him up, Struve said.

Then came the phone call from Austin about Ablanedo's death. "I remember screaming. Nobody could stop me from screaming," Marjorie Powell said. "It destroyed me, really. I love him with all my heart, of course. And I have never stopped loving him."

Marjorie Powell spent her life savings on lawyers and sat through emotionally wrenching trials, crying out in anguish when her son was sentenced to death, again, in 1991. She and her husband divorced, and Bill Powell died in 2007.

If there has been any silver lining, Marjorie Powell said, it has been watching her son regain the sweet disposition he had as a child.

"He tries to help anybody that's around him, even the guards. One guard talked to me and said he was all for David, that David seemed like a wonderful person — and that's a guard," she said. "I've had mothers of different cellmates call to say how David has been so kind to their sons."

'What a hero'

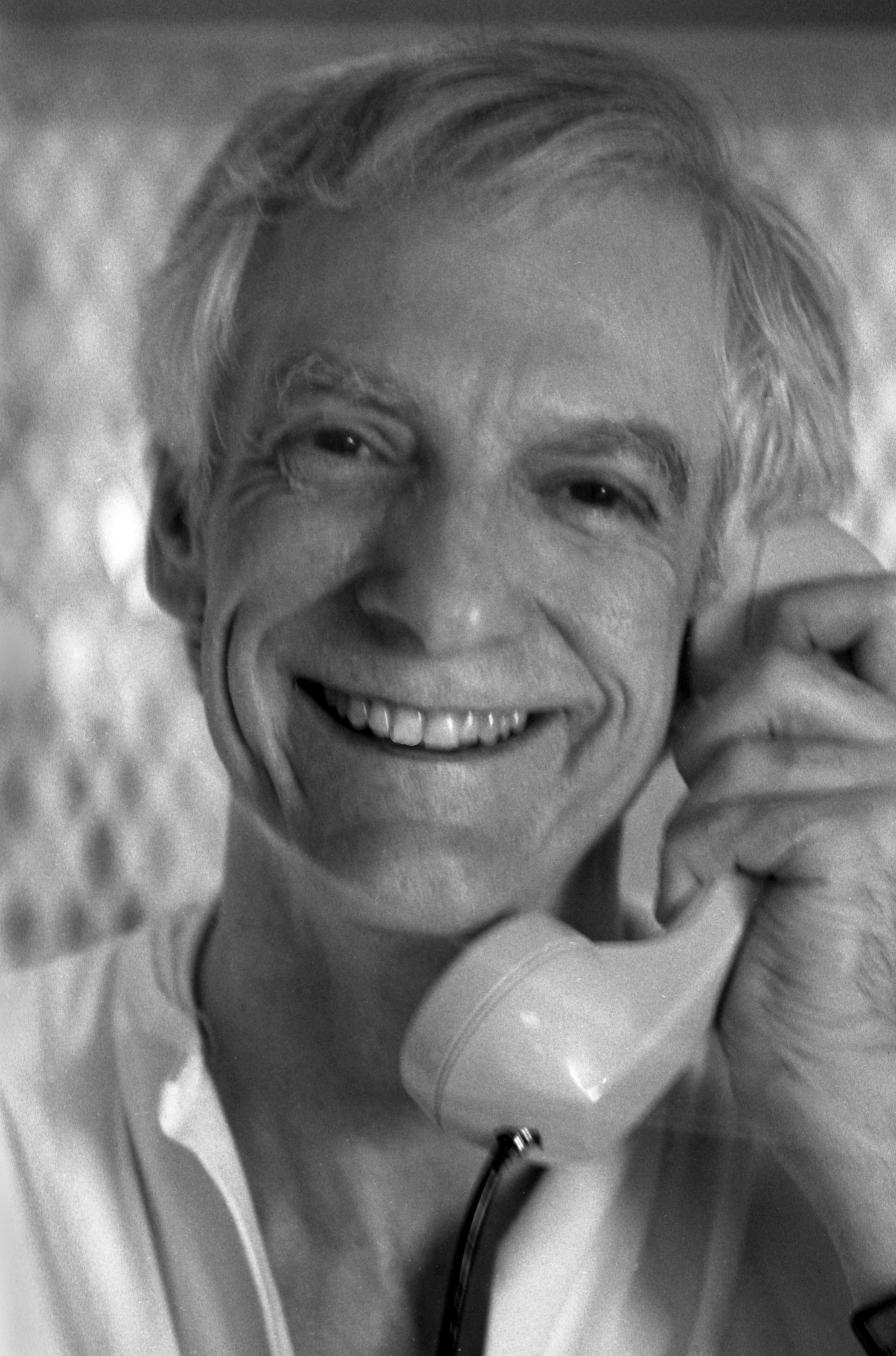

Before he reported to duty for his final patrol shift, Ralph Ablanedo spent a few minutes sitting with his wife, Judy, on the front porch of their South Austin home. He was sniffling from spring allergies but eager to work, Judy recalled.

"He was absolutely the model that you would want a police officer to be," said former Austin police Sgt. Sam Cox, who was Ablanedo's supervisor. "He had an even temperament, a great family, a supportive wife and a bright future, and he loved what he was doing. He was just a good, decent human being."

Soon after her husband drove away, Judy Ablanedo put their children to bed. Several hours later, she was awakened by pounding on the front door.

The officer at the door had already summoned a neighbor to care for the Ablanedo children, and he whisked Judy to the hospital in his patrol car.

How bad is it? she asked.

It's serious, he told her.

They were at the hospital only a few minutes before Police Chief Frank Dyson and a doctor walked into the waiting room. Judy sank into a chair and sobbed.

"Nobody had to say anything," she said. "It was written on everyone's face."

Mills was already there, having ridden in the ambulance with his friend and patrol partner. Together, he and Judy took on the grim task of telling Ablanedo's parents, who had moved to Austin in 1964, that their son was dead.

Over the next two years, Judy Ablanedo and Mills spent a lot of time together. He'd listen to her anger and sadness in late-night phone calls. A relationship bloomed, and they married in October 1980.

David Ablanedo, only 17 months old when his dad was killed, has learned about the man through stories shared by other family members, from reading scrapbooks of newspaper clippings and from photographs. One of his favorite photos hangs on a wall at the Austin Police Department. He had seen it while visiting Bruce Mills, whose last name he assumed.

"You think about, 'Who was my dad?'" David Mills said. "Naturally, you want to know who he was."

Over the years, he has thought of his father as a hero, not just because of what happened that night, but because of his devotion to his family and desire to make the world a better place.

"He died in the line of duty serving the city, and as a boy, you look up to your dad," he said. "You look to Ralph and say, 'What a hero.'"

'Nobody wins'

For years, Ablanedo's family has watched in frustration as Powell's case, which they viewed as clear-cut, prompted new trials and appeals.

With Powell's execution now days away, they are making plans for their own journey to justice.

David, who works in the San Francisco area for a human resources consulting firm, is flying in for the execution. His older brother, Steve, a 911 dispatcher in Boston, also will attend.

Ralph's sister Irene, his brother Armand and their 87-year-old mother, Betsy, are driving to Huntsville a day early to make sure nothing comes between them and the execution witness room. Ablanedo's father died of natural causes in 1981.

They predict relief will be the prevailing emotion when the death sentence is carried out — mostly because it will mark the end of any legal proceeding.

"But it is one of those things where nobody wins," Judy Mills said. "He will be put to death, and Ralph will still be gone. It's not about feeling better. There is nothing to feel good about."

In recent months, Bruce Mills has pondered the death penalty and Powell's execution. He thinks that in this instance, part of the purpose of the execution has lost its meaning.

"I don't think it is about deterrent," he said. "It is about retribution."

Judy Mills said, "If it had been done in a timely fashion, it might have been a deterrent, but when you can play the system for that many years, I don't think it is."

But Bruce Mills said the passage of three decades doesn't make Powell's execution any less deserved. He said he supports Powell's rights, including his ability to appeal, but said the legal course that wound through 30 years has been unfair.

"That is the injustice to the family and what the death penalty was meant for," Bruce Mills said.

'Terribly sorry'

Hands cuffed behind his back and a guard at each shoulder, Powell is led into a cramped booth in the Polunsky Unit's visitor lounge. The cuffs are unlocked through a hole in the metal door behind him, and he smiles widely as he picks up the phone to begin his first-ever interview with newspaper reporters.

Powell at 59, his hair gone silver and his gaze steady, is a far cry from the dazed, unkempt man who appeared in photos after his arrest.

He pauses often to collect his thoughts, which tend toward the philosophical.

"Thirty-two years ago, I was responsible for an enormously evil act, and it must have affected most or all people who lived in Austin and their level of comfort, the way they saw themselves and their neighbors," he said. "And no apology I could give would be powerful enough to express my regret for that.

"But every person is more than the worst thing they have ever done, and I am no exception."

Powell's lawyers always advised him to avoid contact with Ablanedo's family and the media, but with his appeals exhausted, he is free to try to explain himself.

He's also free to pursue a goal he knows will be elusive: redemption.

Powell's letter to the Ablanedo family — the first time he publicly took responsibility for the officer's death — was meant to let them "know how terribly sorry I was." Powell also offered to meet with anybody who feels they might be helped by the conversation, but Ablanedo's family wasn't interested.

"I guess the question I'm asking myself is how much pain is sufficient to achieve redemption in the aftermath of irreparable damage. And I don't guess you can ever achieve redemption in this," he said.

"I hope I'm a better person now than I was then. But the truth is, most of my life I was a better person than what you know of me. Time has allowed my true character to re-emerge and show itself. That's how I understand it."

With his execution looking more and more likely, Powell said he hopes to "connect with family and loved ones outside family — let them know what they've meant to me, apologize for my departure and say goodbye."

Inmates can have up to five people at the execution chamber, where they gather in a separate room from the one holding the victim's family. Powell said he has tried to discourage family and friends from watching, fearing they "will be damaged by what they witness."

"I have encouraged everybody to stay away, to be honest. Nonetheless, there will be some there."

An indelible impact

Today, Ralph Ablanedo Drive runs more than a half-mile through a South Austin neighborhood.

The officer's name is read aloud at an annual ceremony commemorating fallen officers.

And sometime soon, a 5-foot-tall gray granite memorial will mark the site, near Live Oak Street and Travis Heights Boulevard, where Ablanedo was shot.

Powell has spent more of his life on death row than in freedom. Friends and supporters continue to rally on his behalf, primarily through the website letdavidlive.org, but his appeals are over. His lawyer, Burr, has compiled an extensive application asking the parole board for clemency, knowing that only five of 58 such petitions have been granted over the past four years.

The governor can accept or reject the recommendation of the parole board, which has not yet acted on the request.

However it ends for Powell, his case has left an indelible impact on Austin.

Carsner, the jury foreman from Powell's second trial, recalls several jurors crying and others shaking their heads as they voted by rising from their chairs.

"Nobody verbalized, 'Let's get rid of this guy; he needs to die,' or anything like that," he said. "I was voting my own thoughts about the matter, and thinking about the community and how they felt about a police officer's death."

As for Powell, Carsner said he walked away disappointed in the man.

"It looked like he really could've made something of himself. He just really screwed up, and it didn't happen to him all at once," Carsner said. "He got into drugs, selling and using more, then got interested in guns.

"He was just going down this trail, and there didn't seem to be any way back for him."

Lives interrupted

Since Powell's first conviction in 1978, Texas has executed 459 inmates, including six from Travis County.

Of the 322 inmates on death row, only five have been there longer than Powell.

If executed, Powell will be the state's longest-serving member of death row to receive lethal injection. Excell White was executed in 1999 after 24 years, three months.

"Drug dealer executed for 1978 slaying of Austin cop," by Mary Rainwater.

HUNTSVILLE — After 32 years on Texas’ death row, David Lee Powell was executed Tuesday for the shooting of an Austin police officer during a routine traffic stop in 1978.

Powell, 59, became the longest serving inmate executed in Texas since the state began carrying out executions again in 1982, and was the 13th death row inmate to be executed in the state this year.

When given the chance, Powell gave no last statement to witnesses, but — except for a quick gasp and soft snoring — quietly succumbed to the lethal drug cocktail released into his body.

He was pronounced dead nine minutes later, at 6:19 p.m.

While all was silent inside the walls of the Huntsville Unit, the grounds outside the prison facility were bustling with activity.

Both pro- and anti-death penalty activists stood outside the taped off area of the site, as television crews and other media lined the sidewalk to capture witnesses making their way to and from the unit.

At another area, some 150 retired and active police officers from Austin waited outside the prison as the punishment was carried out. They stood at attention as Ablanedo's family left the prison.

“While we do not take lightly today's events, there is a sense of relief ... as the passage of time has allowed for healing,” said Wayne Benson, president of the Austin Police Officers Association. “However, no amount of time will relieve the sadness.”

Powell was executed about 30 minutes after the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear his appeal. His attorneys had argued unsuccessfully that his exemplary behavior on death row over the past three decades showed jurors were wrong when they decided he would be a continuing danger and should die for killing 26-year-old Ralph Ablanedo.

In May 1978, Ablanedo pulled over a car driven by Powell's girlfriend because it had no rear license plate. A background check showed Powell, riding in the passenger seat, was wanted for theft and passing bad checks. Powell shot the officer 10 times with a Chinese version of a Soviet-made AK-47.

He was sentenced to death three times, most recently in 1999. The Supreme Court overturned his original conviction from 1978, and the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals threw out his death sentence from a 1991 retrial.

“I am infinitely sorry that I killed Ralph Ablanedo,” Powell said in a December 2009 letter, intended for the officer's family and kept in the inmate’s court file. “In a few frightful seconds, I stole from you and the world the precious and irreplaceable life of a good man.”

Bruce Mills, an officer who was Ablanedo's backup the night of the slaying and accompanied his mortally wounded partner to the hospital, eventually married Ablanedo's widow and adopted their two sons.

The family watched the execution from the viewing area. Mills had said earlier that it was time for the sentence to be carried out.

“I'm a big believer in due process,” he said. “He's had every single T crossed and I dotted to have this reviewed and that reviewed and reviewed again.”

Powell stared at the family as they entered the viewing area but said nothing. He was not a typical criminal. He grew up on a dairy farm near Campbell in Hunt County, graduated a year early as valedictorian from his small high school and went into the honors program at the University of Texas at Austin.

He was majoring in physics and math and aspiring to be a doctor when he got hooked on methamphetamines and never finished college.

Powell was on his way to a drug deal when Ablanedo pulled over the car, said authorities, who later found .45-caliber handgun and about $5,000 worth of illegal drugs in the vehicle.

The next scheduled execution is that of Jonathan Marcus Green on June 30. Green was convicted in 2002 for the kidnapping, rape and murder of a 12-year-old Montgomery County girl in June of 2000.

David Lee Powell was valedictorian and “most likely to succeed” in his high school class. After graduating from high school a year early, he was accepted into the Plan II Honors Program at the University of Texas. While there, he became an anti-war protester and began using drugs. He never finished college. By 1978, when he was 28 years old, he had become a heavy user of methamphetamine and was also selling it. He was wanted by the police for misdemeanor theft and for passing over 100 bad checks to merchants in the Austin area. He had become so paranoid that he had begun carrying around loaded weapons, including a .45 caliber pistol, an AK-47, and a hand grenade.

On May 17, 1978, Powell asked his former girlfriend, Sheila Meinert, to drive him from Austin to Killeen, Texas. They went in Powell’s car, a red Mustang. Powell had the .45, the AK-47, and the hand grenade with him, as well as a backpack containing about 2 1/4 ounces of methamphetamine. Officer Ralph Ablanedo was on duty in his marked patrol car when he spotted the Mustang and noticed that it did not have a rear license tag. He pulled the vehicle over. Meinert got out of the car and approached Ablanedo. She told him that she had lost her driver’s license, but showed him her passport. Ablanedo also checked Powell’s driver’s license and asked the dispatcher to run a warrant check on Meinert and Powell. The dispatcher informed Ablanedo that the computers were not functioning properly, but that there were no local warrants for Meinert. Ablanedo gave Meinert a ticket for failing to display a driver’s license and allowed her and Powell to leave.

Moments later, the dispatcher told Ablanedo that Powell had a “possible wanted” for misdemeanor theft. Ablanedo signaled for Meinert to pull over again. Meinert testified that she got out of the car and as she was approaching the officer, she heard a very loud noise and ran back to the car. As Ablanedo approached the Mustang, Powell shot him with the AK-47, in semi-automatic mode, through the car’s back window, knocking Ablanedo to the ground. As Ablanedo tried to get up, Powell fired at him again, after switching the AK-47 to automatic mode. Dr. John Blewett, an emergency room physician, and Austin Police Officer Roger Napier, testified that they, too, heard Ablanedo say “that damn girl” when he was in the emergency room prior to his death.

Bobby Bullard, who happened to be driving by on his way home from work, witnessed the shooting of Ablanedo. He testified at trial that he saw shots fired from the Mustang that knocked out the back windshield. He saw a man sitting in the middle of the front seat, lying on top of the console, sort of into the back seat. He said that the man who fired the shots had long hair and was wearing a white t-shirt, and at trial he identified Powell as the man he saw that night. Edward Segura, who lived in the area, heard what he thought sounded like machine gun fire. When he went outside, he saw a red Mustang driving away. Segura testified that Ablanedo said that he had been shot. When Segura asked, “who was it,” Ablanedo replied, “a girl.”

When the dispatcher learned that there was a possible warrant for Powell, as a matter of routine, she sent Officer Bruce Mills to assist Ablanedo. When Mills arrived at the scene a few minutes later, he found Officer Ablanedo lying on the ground. Although Ablanedo wore a bullet-proof vest, it was not designed to withstand automatic weapon fire. Ablanedo suffered ten gunshot wounds and died on the operating table at the hospital, about an hour after he was shot. Bullard, his wife Velma, who came outside after seeing the lights from the police car, Segura, and Officer Mills all attempted to aid Ablanedo while waiting for the ambulance to arrive. All of them testified that Ablanedo said, repeatedly, “that damn girl” or “that Goddamn girl.” Mills testified that Ablanedo told him that a girl and a guy were in the car, and that they were armed with a shotgun or machine gun. Mills said that Ablanedo told him, twice, that “He got me with the shotgun.” Apparently one of the shots fired by Powell flattened one of the Mustang’s rear tires.

Meinert drove the car into the parking lot of a nearby apartment complex. Officer Villegas, who was en route to the scene and who had heard a description of the Mustang in the dispatcher’s broadcast, spotted the vehicle in the apartment complex parking lot and pulled in. He immediately came under automatic weapon fire. He testified that a male with medium length hair and no shirt was firing at him. More police officers arrived, and a shoot-out ensued. Miraculously, no one was shot. Sheila Meinert testified that Powell handed her a hand grenade in the apartment complex parking lot and told her to remove the tape from it. She said that she started peeling tape off the grenade, but was hysterical and shoved it back at him and she did not know what he did with it.

Officer Bruce Boardman testified that the shooting in the apartment complex parking lot came from a person at the passenger side of the Mustang. He said that he saw that person appear again, making “a throwing motion” over the top of the Mustang, and simultaneously, a female at the driver’s side of the Mustang ran away from the car, screaming hysterically and flailing her arms. The person at the passenger’s side (Powell), after making the “throwing motion,” began running away from the scene toward the grounds of a high school across the street. Later, officers found a live hand grenade about ten feet away from the driver’s door of Officer Villegas’s car that was parked in the same parking lot. The pin for the grenade was discovered outside the passenger side of the Mustang where the person making the throwing motion had been. The grenade, which had a kill radius of 16 feet and a casualty radius of 49 feet, did not explode because the safety clip had not been removed. The State presented evidence that it was likely that only someone who had been in the Army (Powell had not) would have been familiar with the concept of a safety clip (also known as a jungle clip), which was added to the design during the Vietnam War to keep grenades from exploding accidentally if the pin got caught on a branch.

Meinert was arrested in the apartment complex parking lot. She was later convicted as a party to the attempted capital murder of Officer Villegas. Powell was arrested a few hours later, around 4:00 a.m. on May 18, after he was found hiding behind some shrubbery on the grounds of the high school. Powell’s .45 caliber pistol was found on the ground near where he was hiding, and his backpack containing methamphetamine with a street value of approximately $5,000 was found hanging in a tree. Law enforcement officers searched the Mustang and recovered handcuffs, a book entitled “The Book of Rifles”, handwritten notes about weapons, cartridge casings, the AK-47, a shoulder holster, and a gun case. Following a search of Powell’s residence, officers seized another hand grenade, methamphetamine, ammunition, chemicals and laboratory equipment for the manufacture of methamphetamine, and military manuals. In September 1978, Powell was convicted and sentenced to death for the capital murder of Officer Ablanedo.

UPDATE: In his first comments to the family of an Austin police officer he fatally shot more than 30 years ago, Texas death row inmate David Lee Powell took responsibility in a hand-written letter and apologized for “the evil I have done. I am infinitely sorry that I killed Ralph Ablanedo,” wrote Powell, who shot Ablanedo 10 times with an AK-47, according to court records. “I stole from you and the world the precious and irreplaceable life of a good man.” Powell, whose execution date could be set within days, said he has no excuse for what happened May 18, 1978, in the 900 block of Live Oak Street near Travis High School in South Austin, but wrote that his actions happened “in a few frightened seconds.” He said that he wrote the four-page letter, dated Dec. 31, after years of consideration and that he wanted to address the enormity of his action. “I felt a spiritual need and a moral obligation to offer you whatever little I could,” Powell wrote.

“I’m skeptical of the sincerity at this late date,” said Bruce Mills, who was Ablanedo’s patrol partner and later married his widow and adopted his two sons. “His taking responsibility or apologizing doesn’t change anything for me.” In the letter to Ablanedo’s family, Powell addressed Ablanedo’s mother, siblings, widow, two sons and Mills. Powell told Betsy Ablanedo that “in your son’s place, I left a deep and enduring sorrow. I know this because I left a different, but related sorrow in what had been my place in my mother’s life.” He wrote to Irene and Armand Ablanedo that they must miss their brother each day: “I placed an empty chair at the family table forever.” In his comments to Judy Mills, Powell said, “because of me, you had to explain to your sons that their father would never come home again. Because of me, you had to overcome the sorrow of your bereavement while starting life over as a single parent.” Powell told David and Steve Mills, Ablanedo’s sons, that “I stole from you a hero.” David Mills said Wednesday that “it was a good gesture to at least acknowledge to the family that he admits guilt, that he is apologetic. I guess I hope that maybe it was something that would bring him some closure as well.” But to Mills, the letter doesn’t change the facts of his father’s death or his opinion that Powell’s death sentence should be carried out.

"After 32 years on death row, Powell put to death." (June 15, 2010)

David Lee Powell was pronounced dead by prison officials at 6:19 p.m. Tuesday in Huntsville, Texas.

Powell was given a lethal mixture of drugs, after the U.S. Supreme Court refused to grant him a last-minute reprieve. He died nine minutes after the lethal dose began.

Powell has been tried three times for capital murder. The first two trials were overturned in the appeal process. A third trial required the sentencing portion to be heard. Each case ended with the jury assessing the death penalty.

The story begins in 1978, when Austin Police Officer Ralph Ablanedo pulled over a 1966 red Ford Mustang near Downtown Austin with no rear license plate. After making the traffic stop, the officer issued driver Sheila Meinert a ticket, then proceeded with a routine check on the passenger.

At the time, the computer system to check warrants was down, letting the occupants of the Mustang go. Moments later, Ablanedo received notice, that the passenger, David Lee Powell, was wanted for misdemeanor warrants of theft and passing bad checks.

Ablanedo pulled over the vehicle again.

The investigation shows Powell grabbed an AK-47 and opened fire, shooting through the rear window of the Mustang. Ablanedo was hit 10 times, gunshots ripping through his bullet proof vest. Later, he was pronounced dead at Brackenridge Hospital.

Ablanedo was 26-years-old and a father of two. Ablanedo's partner, Bruce Mills, married Ablanedo’s widow two years after the shooting death.

Retired Austin Police Sergeant Sam Cox was Ablanedo’s supervisor in 1978. He vividly remembers the day the noise of the shooting consumed police radio frequency, saying, "Later on in the evening, that's when it all broke loose. You know, you hear the screams on the radio, and a call for help.”

When asked what was heard on scanner traffic that indicated there was a serious problem Cox said, "Oh geez, officer down."

Now, 32 years later, Powell was put to death for killing Officer Ablanedo.

The death by lethal injection made Powell the longest-serving condemned inmate executed in Texas and one of the longest-serving in the nation put to death.

Members of Ablanedo's family and more than 100 current and former police officers attended the execution to see the legal process through.

One of those in attendance was an officer involved in the manhunt and arrest of Powell for the murder.

"In this process, the wheels of justice have flat fallen off the cart. Millions of dollars have been spent. It never was a question of guilt or innocence, ever. It was about trying to get his life saved," Cox said.

Austin Police Union President Wayne Vincent spoke for the Albanedo family to members of the media, issuing thanks to all the community for their support in a lengthy 32 year process.

"While we do not take lightly today's events, there is a sense of relief ... as the passage of time has allowed for healing," said Wayne Vincent, "However, no amount of time will relieve the sadness."

Anti-death penalty activities were also in Huntsville Tuesday. They protested the execution.

Rest in peace David Lee Powell

We love you and will never forget you. Your fight is over, but you have given it over to us, and we will honor that struggle until the death penalty is gone. There will never be another you.

Home

David's story

Powell v. State, 742 S.W.2d 353 (Tex.Crim.App. 1987). (Direct Appeal)

Defendant was convicted in the 167th Judicial District Court, Travis County, Tom Blackwell, J., of capital murder, and was sentenced to death. He appealed. The Court of Criminal Appeals, McCormick, J., held that defendant, by presenting insanity defense in guilt-innocence phase of capital murder trial, waived his Fifth Amendment privilege as to testimony by prosecution mental health experts on issue of future dangerousness in punishment phase of trial. Affirmed. Duncan, J., concurred in results. Onion, P.J., filed dissenting opinion in which Clinton, and Teague, JJ., joined. Teague, J., filed dissenting and concurring opinion.

McCORMICK, Judge.

Appellant was convicted of the capital murder. The jury assessed his punishment at death.

Shortly after midnight on May 18, 1978, Austin police officer Ralph Ablanedo, was on duty. At 12:41 a.m. Polly Bittick, the police radio dispatcher on duty, received a call from Ablanedo requesting a check through the National Criminal Information center (NCIC) on a person named Sheila Margaret Meinert, to determine if she was wanted for any offense. Ablanedo stated that he was in the 900 block of Live Oak Street. He also gave a vehicle identification number (VIN), and asked for a computer check to determine if the vehicle bearing that number was stolen. Bittick called back to advise that the vehicle inquiry was still pending, and that Meinert was not wanted by local authorities. At 12:46 a.m., Ablanedo radioed a request for a check on David Lee Powell, the appellant. Bittick's computer check showed a “possible wanted” on Powell, and she dispatched officer Bruce Mills to assist Ablanedo. This she stated was normal procedure when a computer check determined that a person was a “possible wanted.” Ablanedo called back to ask what Bittick had on appellant, and she told him, “... a possible misdemeanor theft.” Shortly thereafter, Bittick heard something like a scream over the radio, and then the voice of Mills calling for more patrol units. Mills then advised that he needed an ambulance, and stated there was an officer “down.” Mills stated that there was a red Mustang involved, going eastbound, and that the occupants were armed.

Other witnesses who resided in the 900 block of Live Oak Street described seeing a red Mustang automobile stopped in that block, with a police car behind it. The police car had its flashing lights on. A police officer and a female were seen standing between the two cars. Then there was the sound of gunshots, and the Mustang drove rapidly away. Appellant was identified as having been sitting in the back seat of the Mustang as the shots were fired, with another person sitting in the driver's seat. The Mustang stopped further up the street, and appellant moved to the front passenger side.

Officer Joe Villegas heard the radio description of the red Mustang, and concluded that a particular apartment complex nearby on Oltorf Street would be a likely hiding place. Checking the parking lot of the complex with his spotlight, Villegas saw a red Mustang with two occupants. As he pulled into the parking lot, he was met with a hail of automatic weapon fire coming from the right rear of the Mustang. He stopped, jumped out of his car, and returned the fire. Shortly thereafter, he saw a man running in a crouched position from the Mustang, south toward Travis High School. The man turned back and looked at Villegas from a distance of 15 or 20 yards, and Villegas later identified the man as appellant. Appellant disappeared around the corner of the high school.

Sergeant Darrell Gambrell joined Villegas during the firing at the apartment complex and saw a person get out of the Mustang and lie down next to it as the other person was running toward the high school. Gambrell and Officer Tommy Foree reached the person lying down, handcuffed her and searched her for weapons. The person was Sheila Meinert, appellant's companion. Inside the Mustang, the officers found an AK-47 automatic rifle, which was still hot to the touch from recently having been fired. It was later shown that Ablanedo had been shot with a Chinese version of a Russian AK-47 automatic rifle.

Officer Bruce Boardman came upon the apartment complex as the firing was going on. He saw a person with long hair come up and make a throwing motion toward Officer Villegas and those with him. An unexploded hand grenade was later found about ten feet from Villegas' patrol car. The safety pin had been removed. An officer found a pin similar to the type used in such grenades lying on the ground approximately three feet from the passenger door of the Mustang. At dawn appellant was found under a bush at Travis High School by a school patrolman. He offered no resistance.

After the State rested, appellant raised the defense of insanity at the time of the offense. See V.T.C.A., Penal Code, Section 8.01. His evidence on this issue came chiefly from Dr. Emanuel Tenay, a psychiatrist. Dr. Tenay testified that he had conducted lengthy interviews with appellant, members of his family, and his friends and acquaintances, and had reviewed a sizeable amount of appellant's personal writings. In Tenay's opinion, appellant had been insane on May 18, 1978, at the time officer Ablanedo was shot and killed. He believed that on that occasion appellant was suffering from paranoid schizophrenia, a form of psychosis. Dr. Tenay believed that this condition was largely the result of prolonged use of psychoactive drugs such as amphetamine and methamphetamine. There was other evidence that appellant had been heavily involved in the sale and perhaps manufacture of amphetamines, or “speed.”

The State sought to rebut this defensive theory through the testimony of Dr. Richard Coons, a psychiatrist, and Dr. George Parker, a psychologist. Dr. Coons met with and examined appellant on four occasions: on May 18, 1978, some 12 hours after the shooting, and again on May 23, May 29 and June 4, 1978. The first meeting occurred pursuant to an order signed by the trial court on the morning of the shooting. This order provided that appellant undergo examination and testing by Dr. Coons and a practicing psychologist of his choice to determine appellant's competency to stand trial and sanity at the time of the alleged offense. This order was made upon the motion of the State. Dr. Coons testified that based on his several examinations of appellant, there was no indication that appellant had been insane on May 18, 1978. He specifically disclaimed having observed any evidence that appellant was suffering from paranoid schizophrenia.

Dr. George Parker, a clinical psychologist practicing in Austin, testified that he had met with appellant on June 25 and July 2, 1978, at the Travis County jail. Each meeting lasted two to two and a half hours. He administered several standardized psychological tests to appellant, to determine intelligence, to detect the presence of any organic neurological disorders, and to examine personality functions. He was able to detect no organic difficulties. He found appellant to be very intelligent and articulate, with an IQ of 128. He characterized appellant's personality as impulsive, high-energy, rebellious, non-conforming, immature and somewhat egocentric. He stated the opinion that on May 18, 1978, appellant had been sane under Texas law, and that the testing showed no indication of paranoid schizophrenia. The jury's verdict at the guilt stage of the trial obviously indicates that it found the State's evidence more persuasive on the insanity issue.

At the penalty stage of the trial the State put on evidence that in January 1978, after having been evicted from an apartment for nonpayment of rent and having had the personal property therein impounded in December of 1977 by the landlord, George Sandlin, appellant had broken into Sandlin's storage facility to remove his belongings. Lee Ramos, a maintenance employee who was driving a Sandlin truck, happened upon this apparent burglary and stopped his truck. Appellant advanced upon him with a knife, and when Ramos fled in his truck, appellant chased him all the way home and then tried to get him to come outside. Ramos declined.

Also admitted as punishment evidence was testimony that a search of appellant's house the day after the shooting revealed a hand grenade, two cannisters of ether, a box of .45 caliber ammunition, a box of 7.62 mm Russian ammunition, and a set of die used in processing ammunition for an AK-47 Russian automatic rifle. Also found in the kitchen and seized were various beakers, chemicals and paraphernalia. A photograph of these items as they appeared in the kitchen was admitted into evidence. The police conducting the search also seized three small vials containing methamphetamine, with a total weight of approximately one gram.

Drs. Coon and Parker were called by the State and permitted, over objection, to testify on the issue of future dangerousness based on their examinations, interviews and testings of appellant. Both testified that in their opinion there was a “high” probability appellant would commit future acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society.

Appellant called Ronnie Earle, the Travis County district attorney, who testified that appellant through his counsel had volunteered the information that there was a hand grenade in his house. Edith Roberts, one of appellant's counsel, also testified to the voluntary surrender of the grenade.

In his first point of error appellant complains that prospective juror Catherine Simmons was improperly excused for cause in violation of Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510, 88 S.Ct. 1770, 20 L.Ed.2d 776 (1968), and Adams v. Texas, 448 U.S. 38, 100 S.Ct. 2521, 65 L.Ed.2d 581 (1980). Since appellant failed to object to the exclusion for cause of prospective juror Simmons, error, if any, has been waived. Modden v. State, 721 S.W.2d 859 (Tex.Cr.App.1986); Mann v. State, 718 S.W.2d 741 (Tex.Cr.App.1986); Stewart v. State, 686 S.W.2d 118 (Tex.Cr.App.1984).

In his second point of error appellant contends that Dr. Coons and Dr. Parker were improperly permitted by the court, over objection, to testify for the State at the penalty stage of the trial and to express their opinion on the issue of future dangerousness. Appellant relies upon Estelle v. Smith, 451 U.S. 454, 101 S.Ct. 1866, 68 L.Ed.2d 359 (1981) and Battie v. Estelle, 655 F.2d 692 (5th Cir.1981).

The Supreme Court, in Estelle v. Smith, supra, speaking through Chief Justice Burger, held that where prior to the in-custody psychiatric examination ordered by the court to determine the defendant's competency to stand trial the defendant had not been warned that he had the right to remain silent, and that any statement made could be used against him at the sentencing proceeding, admission at the penalty stage of a capital felony trial of a psychiatrist's damaging testimony on the crucial issue of future dangerousness violated the Fifth amendment privilege against compelled self-incrimination because of a lack of appraisal of rights and a knowing waiver thereof, the death penalty imposed could not stand.

The Court further held that the Sixth Amendment's right to counsel was violated where defense counsel was not notified in advance that the psychiatric examination would encompass the issue of future dangerousness and there was no affirmative waiver of the right to counsel.

In Estelle, the Dallas County district judge, on his own motion, appointed Dr. James Grigson to examine the defendant on the issue of his competency to stand trial. Article 46.02, V.A.C.C.P. Dr. Grigson examined the defendant without giving any warnings regarding his Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination and did not notify the defense counsel that the psychiatric examination would encompass the issue of the defendant's future dangerousness, nor was the defendant accorded the assistance of counsel in determining whether to submit to such examination, etc. After the examination, Dr. Grigson reported to the court that Smith was competent to stand trial. The case went to trial with no issue being raised as to the defendant's competency to stand trial or as to the defensive issue of insanity at the time of the alleged offense. After Smith was convicted at the guilt stage of the bifurcated trial of the capital murder, Dr. Grigson was called by the State at the penalty stage of the trial to testify that, based upon his examination, he considered the defendant Smith a severe sociopath who would commit violent acts in the future “if given the opportunity to do so.” The jury subsequently returned affirmative answers to the special issues submitted under Article 37.071(b), V.A.C.C.P., and the trial court assessed the death penalty.

In the instant case appellant was taken before a magistrate on the day of his arrest and warned of the accusation against him. A complaint was filed five days later on May 23, 1978, and the first indictment was presented on the same date. A second indictment was returned on June 29, 1978. Shortly after appellant's apprehension on May 18, 1978, Steve Edwards, assistant district attorney, filed a motion requesting the court to order a psychiatric examination, claiming he had information which raised questions of the appellant Powell's mental competency to stand trial and his sanity at the time of the commission of the offense. The same day the trial court ordered a psychiatric examination of appellant to be made by Dr. Richard Coons and a psychologist of his choice. As noted above, this examination was for the purpose of determining both appellant's competency to stand trial and his sanity at the time of the offense. On May 18, 1978, one of appellant's counsel, Edith Roberts, was appointed. On May 23 and 24, 1978, Roberts had telephone conversations with Dr. Coons who obtained her permission for Dr. Parker to do some psychological testing of appellant. The record reflects that at no point in time did Coons or Parker inform appellant or his attorneys that they were asked to or had examined appellant on the issue of future dangerousness. Nor did Coons or Parker give appellant, who was in custody, Miranda warnings.