Executed July 1, 2010 06:17 p.m. CDT by Lethal Injection in Texas

30th murderer executed in U.S. in 2010

1218th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

14th murderer executed in Texas in 2010

461st murderer executed in Texas since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(30) |

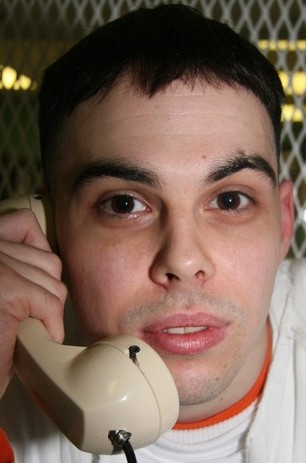

Michael James Perry W / M / 19 - 28 |

Sandra Stotler W / F / 50 |

Citations:

Perry v. State, 158 S.W.3d 438 (Tex.Crim.App. 2004). (Direct Appeal)

Perry v. Quarterman, 314 Fed.Appx. 663 (5th Cir. 2009). (Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

Three bacon,egg, cheese omelets. In addition three chicken cheese enchiladas and 3 each of Pepsi, Coke and Dr. Pepper.

Last Words:

“I want to start off by saying I want everyone to know that’s involved in this atrocity that they are forgiven by me.” He sobbed briefly, then whispered, “Mom, I love you. I’m coming home, Dad. I’m coming home.”

Internet Sources:

Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Executed Offenders (Perry)

Perry, Michael James

Date of Birth: 04/09/1982

DR#: 999444

Date Received: 03/03/2003

Education: 12 years

Occupation: Laborer

Date of Offense: 10/24/2001

County of Offense: Montgomery

Native County: Harris

Race: White

Gender: Male

Hair Color: Brown

Eye Color: Brown

Height: 5' 09"

Weight: 132

Prior Prison Record: None.

Summary of incident: On 10/24/2001, in Montgomery, Texas, Perry, and one co-defendant fatally shot a 50 year old white female, a 17 year old white male and and 18 year old white male with a shotgun. A vehicle was also stolen from the residence of two of the victims.

Co-Defendants: Jason Aaron Burkett.

Thursday, June 24, 2010

Media Advisory: Michael Perry scheduled for execution

AUSTIN – Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott offers the following information about Michael James Perry, who is scheduled to be executed after 6 p.m. on Thursday, July 1, 2010. A Texas jury sentenced Perry to death for the murder of Sandra Stotler.

FACTS OF THE CRIME

In October 2001, Michael Perry and a friend, Jason Burkett, decided they needed to get one or two vehicles, so On Oct. 24, they went to the Montgomery home of Sandra Stotler, where Perry entered the house through the garage. Perry shot Sandra Stotler with a shotgun and the two men dumped her body, which was found floating in Montgomery County’s Crater Lake.

Perry and Burkett then returned to the gated community where Sandra Stotler lived and waited outside the gate until the dead woman’s son, Adam Stotler, and his friend, 18-year-old Jeremy Richardson arrived. Perry and Burkett lured the teens to a wooded area and killed Adam Stotler and Richardson. Perry and Burkett, driving the Isuzu Rodeo Adam Stotler had been using, went back to Sandra Stotler’s home and stole her Camaro.

On Tuesday morning, October 30, 2001, a Montgomery County Sheriff’s corporal found Perry, Burkett, and another man in the white Isuzu Rodeo at a truck stop. The vehicle hit the corporal in the course of fleeing, but the officer managed to shoot out the back passenger tire. The vehicle crashed into a nearby store. Perry and Burkett, toting a shotgun, climbed a fence and ran to a nearby apartment complex where police arrested them.

After giving him the Miranda warning, a detective took a statement from Perry in which he admitted to the crime.

EVIDENCE OF FUTURE DANGEROUSNESS

Evidence showed that the night before his arrest, Perry pointed a loaded shotgun at Jason Burkett’s girlfriend’s head and said, “I have already killed somebody, it’s not going to hurt me to kill anyone else.”

On May 22, 2001, police arrested Perry for deadly conduct after he shot at a house.

At the end of first grade, when he was eight years old, Perry was diagnosed as having attention deficit disorder (ADD). At the end of the seventh grade, Perry was diagnosed with “oppositional defiant disorder.” At the end of the eighth grade, Perry was diagnosed with “conduct disorder.” “Antisocial personality disorder” is the adult form of these disorders. Although he was twice admitted to a mental hospital, Perry tested negative for bipolar disorder and did not qualify as learning disabled for special education classes in elementary school.

In junior high, Perry stopped going to school. He ran away from home and came back when he felt like it. Perry stole his mother’s jewelry and tried to pawn it, stole his parents’ van and ran it into a mailbox, and broke into a neighbor’s home and tore the wallpaper and whittled the moldings. During this same time period, Perry received counseling from psychologists and psychiatrists.

After Perry was “kicked out” of an “outbound class” in Florida, Perry’s parents filed charges against Perry, and he was ordered by a court to attend a long-term facility for health care. In September 1997, Perry was sent to Father Flanagan’s Boys Town in Nebraska. Three months after his arrival, Perry threatened his house parent, “You know, you people work here. I don’t know why you work here. People like me who are going to rape or kill your kids, you know.” Perry was promptly sent to the locked facility at Boys Town for four months. Perry did not have the level of depression or any DSM-IV disorder to warrant the mental health care provided at the facility.

Perry’s parents, fearing that they would not be able to control Perry, sent him to Casa by the Sea, a secured high school campus in Mexico. Perry graduated from high school, but not from the program at Casa by the Sea, leaving on his eighteenth birthday.

Except for four to six months in the Job Corps, four months in Houston, and a brief stay with his parents, Perry was essentially homeless after leaving Casa by the Sea. Perry stayed for short periods with acquaintances and in shelters. Moreover, except for four to six months in the Job Corps, laying tile in Houston, and a month at Wal-Mart , Perry remained jobless after leaving Casa by the Sea. To support himself and procure alcohol and pills, Perry stole and sold pills as wells as other items. On October 2, 2001, police arrested Perry for presenting a fake prescription for 100 pills of Xanax. Evidence showed that while in the Montgomery County Jail awaiting trial, Perry was unruly. Perry became belligerent, had to be restrained, and tried to bite an officer who was restraining him.

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

10/24/01 - Perry killed Sandra Stotler.

01/15/02 - A Montgomery County grand jury indicted Perry for capital murder.

02/24/03 - A Montgomery County jury convicted Perry of capital murder.

02/28/03 - In accordance with the verdict, the trial judge sentenced Perry to death.

12/15/04 - The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed Perry’s conviction and sentence.

12/29/04 - Perry filed an original application for a state writ of habeas corpus.

10/11/05 - The U.S.Supreme Court refused Perry’s petition for a writ of certiorari.

03/26/06 - The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals denied state habeas relief.

03/28/07 - Perry filed a petition for a federal writ of habeas corpus.

02/22/08 - A U.S. district court denied habeas relief and issued final judgment.

03/11/09 - The U.S. Court of Appeals (5th Circuit) affirmed the denial of habeas relief.

08/06/09 - Perry filed a petition for certiorari review with the U.S. Supreme Court.

11/09/09 - The Supreme Court denied Perry’s petition for certiorari review.

12/16/09 - The trial court scheduled Perry’s execution for Thursday, July 1, 2010.

06/22/10 - Perry filed a motion in state district court for stay.

06/22/10 - Perry filed in the Texs Court of Criminal Appeals for postconviction relief.

06/23/10 - Perry filed a motion in the state trial court to reset the execution date.

06/24/10 - The trial court denied Perry’s motions to vacate or modify execution date.

06/24/10 - The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals dismissed Perry's successive application.

Texas Execution Information Center by David Carson.

Michael James Perry, 28, was executed by lethal injection on 1 July 2010 in Huntsville, Texas for the murder and robbery of three people.

On 24 October 2001, Perry, then 19, and Jason Burkett, 19, went to the Montgomery home where Sandra Stotler, 50, lived with her 17-year-old son, Adam. As Perry later confessed, he and Burkett decided that they needed one or two new vehicles. They knew that Adam Stotler's parents had "a lot of money" as well as "a newer Camaro and Isuzu Rodeo." They devised a plan to ask to spend the night at the Stotlers and then steal the Camaro while they were asleep. Driving Burkett's girlfriend's truck, they went to the home at about 7 p.m. Mrs. Stotler told them that Adam would not be home until around 9 p.m.

They started driving away, but then decided to go back and steal the car while only Mrs. Stotler was home. They parked the pickup down the street and walked back to the house. Burkett knocked on the door and asked to use the phone while Perry snuck into the house through the garage, with the shotgun. Perry hid in the laundry room and knocked on the back door. When Mrs. Stotler came to answer the door, he shot her with the shotgun. She fell to the floor. When he saw that she moved, as if trying to get up, he shot her again. He and Burkett then grabbed some blankets and sheets off the bed to cover thee body. Burkett ran down the street and got the truck and loaded the body into it with the blankets and sheets. Perry wanted to steal the Camaro, but was unable to find the keys. They drove away in the truck, disposed of the body at Crater Lake, then drove to Conroe and picked up Burkett's girlfriend, Kristen Willis.

The group drove back to the Stotler's gated community. They didn't know the code to open the gate, but they knew Adam would be coming home soon. While they were waiting, they devised a plan to tell Adam that a friend of theirs had shot himself while they were hunting squirrels, and they needed his help. Adam then arrived in the Isuzu Rodeo with his friend, Jeremy Richardson, 18. After Perry and Burkett asked Adam for help, they drove out to a wooded area, while Adam and Jeremy followed in the Rodeo. The four boys got out of their vehicles and walked into the woods while Willis stayed in her truck. Adam then suggested that they look for the friend from a different road, so he and Perry drove away in the Rodeo while Burkett and Richardson stayed in the woods.

According to Perry's confession, Adam parked the Rodeo, and the two of them got out. Burkett then approached them with the shotgun, alone. Burkett asked them if they heard gunshots, for he fired his shotgun several times to signal his location to them. Burkett told Adam he would take him to where the others were. Perry walked back to the Rodeo while Adam went with Burkett. Perry saw Burkett shoot Adam, then he covered his eyes and heard another shot. He uncovered his eyes and saw Burkett shoot Adam a third time. Perry then walked over to Adam's body and pulled his car keys out of his pocket. Burkett and Perry drove the Rodeo back to where Willis was waiting. She became upset with them and drove home. Burkett drove Perry back to the Stotlers. Perry grabbed Adam's wallet from the Isuzu and took the keys to the Camaro off of his key ring. He then drove the Camaro away. The boys then went home, smoked some cigarettes, got cleaned up, and went out to a club.

On the morning of 26 October, Perry was driving the stolen Camaro when police spotted him committing traffic violations. After a high speed chase, Perry wrecked the Camaro and fled on foot. He was apprehended and booked as Adam Stotler, whose wallet he was still carrying. He was then released on bond.

On 27 October, Sandra Stotler's body was found in Crater Lake at 4:30 p.m.

On 30 October, a Montgomery County sheriff's corporal spotted the stolen Rodeo at a truck stop, with three occupants. The vehicle struck the corporal in the course of fleeing, but the officer was able to shoot out a rear tire. The vehicle crashed. Perry and Burkett fled on foot, carrying a shotgun. They climbed a fence and ran to a nearby apartment complex, where police arrested them and recovered the shotgun. Perry, who had a deep cut on his arm from the crash, was taken to a hospital for treatment. Officers questioned him at the hospital and obtained the confession related above.

At his trial, Perry claimed that police coerced the confession from him and ignored his request for a lawyer. "I had a gun shoved in my face," he testified. "At the time, there was quite a bit of excitement. I was under the influence. My arms hurt pretty bad and I was real scared ... my condition in my mind state was that I am going to tell [the detective] anything he wants to hear to get him away from me, to get out of this situation, and that's what I did."

Perry had been diagnosed with personality and conduct disorders as a schoolchild. He ran away from home while in junior high school and became a drifter. He supported himself by stealing and selling pills and other items.

A jury convicted Perry of the capital murder of Sandra Stotler in February 2003 and sentenced him to death. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the conviction and sentence in December 2004. All of his subsequent appeals in state and federal court were denied.

Jason Aaron Burkett was convicted of capital murder and sentenced to life in prison. He remains in custody as of this writing.

On a web site set up on his behalf, Perry claimed he was innocent. He stated that "it has now clearly been proven, that the crime actually happened between the 26th and the 27th, at times I was in jail." He emphasized the evidence against Jason Burkett. He also implied that Kristen Willis could have been responsible. "At trial, Kristen stated, that she was afraid of Jason," Perry wrote. "So afraid that she'd do anything for him? Even murder??" He further implied that Willis was given full immunity because her father was a police officer in Montgomery County.

Regarding the circumstances of his arrest on the 26th, Perry only stated that he was taken in for "traffic violations and evading arrest" and omitted any mention of whose car he was driving or whose wallet he used for identification.

Sandra Stotler's mother and daughter and Jeremy Richardson's brother attended Perry's execution and watched it from a viewing room. Perry's mother watched from another viewing room.

"I want to let everyone here who is involved in this atrocity know they're forgiven by me," Perry said in his last statement at his execution. He sobbed briefly, then mouthed "I love you" to his mother. He twice whispered, "I'm coming home, Dad." The lethal injection was then started. He was pronounced dead nine minutes later at 6:17 p.m.

"Inmate executed for nurse's murder; Says he didn't kill Conroe woman," by Mike Tolson. (Associated Press July 1, 2010)

HUNTSVILLE — Condemning his execution as an "atrocity," Michael James Perry was put to death Thursday night for the shotgun murder of a Conroe woman during an alcohol and drug-fueled binge almost a decade ago.

Perry had steadily proclaimed he was innocent of the murder of 50-year-old Sandra Stotler in her fashionable home near Lake Conroe in October 2001. Although he confessed following his arrest several days later, he quickly recanted, claiming he was coerced and physically intimidated into implicating himself. "I want to let everyone here who is involved in this atrocity know they're forgiven by me," Perry said in his final statement, still not acknowledging his role in the woman's death. He sobbed briefly, teared up, mouthed "I love you" to his mother in the witness room, then twice whispered, "I'm coming home, Dad."

Making some peace

Perry, 28, gasped four times before falling silent. He was pronounced dead at 6:17, nine minutes after the lethal injection was administered. He is the 14th inmate to be executed in Texas this year.

"We can get on with our lives now and have peace," said Stotler's mother, Mary Ann Bockwich. Stotler's daughter, Lisa Stotler Balloun, said the day "was not a good day no matter what anyone says" and expressed sympathy for Perry's family. But she said his last statement validated the jury's death sentence. "I needed to look into his eyes and see if he was the monster I had made him out to be, because he was just a 19-year-old kid at the time," Balloun said. "When he said that, I knew that he was. I knew that justice had been served."

Points finger at friend

Perry confessed to authorities that he killed Stotler, a nurse, in her home in the Bentwater subdivision near Conroe on Oct. 24, 2001, then later recanted. He claimed to have been in jail on an unrelated traffic charge at the time that the state's medical examiner pinpointed the time of death - Oct. 26 - and thus could not be the killer. He blamed his former friend and co-defendant, Jason Aaron Burkett, for the shotgun shooting of Stotler and later Stotler's son, Adam, and Adam's friend, Jeremy Richardson. Burkett is serving a life sentence in connection with the boys' deaths.

"Burkett should be up there, too, on the gurney with him," said Charles Richardson, Jeremy's brother, one of the witnesses. "This was friends stabbing friends in the back."

Prosecutors said there was ample evidence supporting Perry's confession and that much of the information he provided could only have come from someone involved in the killings. The time of death was not a real issue, Bill Delmore, an appellate specialist with the Montgomery County District Attorney's Office, has said. He said the forensic evidence did not place an upper limit on how long Stotler, whose body was found in a nearby lake on Oct. 27, had been dead.

Perry's lawyers have claimed Burkett, convicted of capital murder in the boys' deaths but given a life sentence by a jury, was also behind the woman's murder and brought the car to Perry. They produced an affidavit from a jail inmate who claimed Burkett had bragged to him that he had killed all three. "There's no doubt he was making bad decisions at the time," appeals lawyer Jessica Mederson said in an earlier interview. "It does not mean he was guilty of murdering someone."

Stotler's family said Perry's claim of innocence, amplified by a well-produced website, was "just asinine."

"Perry put to death," by Nancy Flake. (Updated: 07.02.10)

HUNTSVILLE – When Michael James Perry said he forgave everyone involved in the “atrocity” of his execution Thursday evening, the daughter of the woman he killed said she knew “justice had been served today.” Perry, 28, was executed by lethal injection just after 6 p.m. Thursday in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice’s Walls Unit for the October 2001 murder of Sandra Stotler, 51, a nurse at Conroe Regional Medical Center.

Perry shot Stotler twice in the back as he lay in wait for her in the laundry room of her Lake Conroe-area home. Taking her red Camaro, he and his accomplice, Jason Burkett, then dumped her body in Crater Lake near Grangerland. Perry and Burkett then went back to her home and lured Stotler’s 16-year-old son Adam and his friend Jeremy Richardson, 18, to a nearby wooded area, where they shot and killed both of them and stole Adam Stotler’s SUV.

Burkett is serving a life sentence for all three murders. Perry was charged only with the murder of Sandra Stotler.

Laying on a gurney, where the combination of three drugs began flowing through his veins at 6:03 p.m., Perry gave his final statement. “I want to start off by saying and letting everyone involved in this atrocity know they’re all forgiven by me.” Looking at his adoptive mother, Gayle Perry, he said, “Mom, I love you,” with his voice breaking. “I’m coming home, Dad.” Perry’s adoptive father died in June. He gave four audible gasps and his breathing slowed, while one tear rolled from his right eye down his cheek. Family members of the Stotlers and Richardson watched quietly and intently, while some wiped away tears. Perry was pronounced dead at 6:17 p.m.

“I felt sorry for his family,” said Lisa Stotler Balloun, Sandra Stotler’s daughter and Adam’s sister. “It’s not a good day for anyone. When he said he forgave us, I knew justice had been served today. I needed to see if he’s a monster – and apparently he is. “I just wish Jason Burkett and Kristin Willis were here sitting beside him.” Willis was Burkett’s girlfriend at the time of the murders and was present in the wooded area when Adam Stotler and Jeremy Richardson were shot, with blood left on the shirt she was wearing, according to trial testimony. She testified against Burkett in his October 2003 trial.

Before the execution, Montgomery County District Attorney Brett Ligon personally reviewed all the evidence, he wrote in a statement Thursday night. “Ethics prevented me from commenting on the ridiculous accusation that Mr. Perry’s confession was somehow coerced and the evidence in his criminal case was flawed,” Ligon stated. “The reality is that Mr. Perry laughed throughout his legal and voluntary confession in which he related gruesome details about the murders of his innocent victims. The remainder of the evidence in the case was as overwhelming as it was disturbing. “Mr. Perry’s last words reflected the way he lived his life: full of hatred, bile and narcissism. I do not relish in the execution of his sentence, but I do not mourn his death. May the victim’s families finally have the peace they deserve.”

Neither Perry nor any of his family members ever reached out to the victims’ families, Lisa Balloun said. “Never. Not once,” she said. “He’s been blaming and pointing fingers since day one. It just infuriates me; we were the ‘bad guys’ in this situation.”

Perry sought a commutation of his death sentence in recent days, claiming, based on a medical examiner’s testimony about Sandra Stotler’s time of death, he was in the Montgomery County Jail and couldn’t have killed her. But the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals and the U.S. Supreme Court didn’t agree, clearing the way for Perry’s execution.

Balloun tells her daughters – one was 3 years old and the other 10 months old when Sandra Stotler was murdered – about “what a wonderful woman she was” and how Adam was “the best uncle in the world,” she said. “Our family is crushed.” For Rosemary Jeffery, Jeremy Richardson’s mother, Perry’s death has not yet brought the closure she seeks. “It won’t be over until Burkett is gone,” she said. “Then ... our family can have some rest.”

But that closure finally seems to have come for the family of Sandra and Adam Stotler. “I’m glad to say this is over,” said Mary Ann Bockwich, Sandra Stotler’s mother and Adam’s grandmother. “We can all have peace now.”

"Killer of Houston-area nurse executed," by Mary Rainwater. (July 1, 2010)

HUNTSVILLE — Texas inmate Michael Perry, 28, was executed Thursday for the slaying of a 50-year-old Conroe-area woman nine years ago. Perry’s last words were full of emotion as he said good-bye to his family and friends witnessing his death. “I want to start off by saying I want everyone to know what’s involved in this atrocity that they are forgiven by me,” he said from the death chamber gurney, his remaining statement almost muted by his sobs. “Mom, I love you. I’m coming home, Dad. I’m coming home.”

As the drugs took effect, his eyes fluttered and he hiccupped four times. A single tear ran down his right cheek, prompting quiet sobs from his mother and an aunt and friends. The victim’s relatives gasped and motioned to each other. Perry was pronounced dead just nine minutes later, at 6:17 p.m., making his the 14th execution to take place in the state this year.

The U.S. Supreme Court, about 90 minutes before the lethal injection, rejected a last-day appeal from Perry’s lawyers. They unsuccessfully argued they had new evidence showing Perry was already in jail when 50-year-old Sandra Stotler was murdered in 2001. They also contended a co-defendant and friend of Perry’s killed Stotler. Prosecutors said a “mountain of evidence” pointed to Perry — most notably that he was seen driving Stotler’s stolen car and bragged about the killing before his arrest.

Holding a photo of Stotler, her daughter Lisa Balloun said she was glad she watched Perry die. “Going in I thought it would be worse,” she said. “And I felt sorry for the family — it is not a good day for anybody. “When we said he forgave us, I knew justice had been served,” she added. “I needed to see if he was the monster I built him up to be. Apparently, he is.”

Perry was convicted of shooting Stotler twice in the back at her home and stealing her red Chevrolet Camaro convertible. Testimony showed Perry and a friend, Jason Burkett, then dumped her body in a lake and returned to her Lake Conroe subdivision to wait for her son, Adam. Prosecutors said Perry and Burkett lured Adam Stotler, 16, and his friend, Jeremy Richardson, 18, to a nearby wooded area, shot them dead and stole Adam Stotler’s SUV.

Two days later, Perry crashed the Camaro after a police chase. He was arrested and released on bond under Adam Stotler’s name because he had Stotler’s wallet and ID. Sandra Stotler’s body was found the next day. Police then arrested Perry and Burkett in Stotler’s SUV after a shootout. Inside the truck, officers found the 12-gauge shotgun used to kill Sandra Stotler.

Perry never was charged with the two other slayings. Burkett is serving a life sentence for his role. A Montgomery County jury deliberated two hours to convict Perry; jurors took another six hours to send him to death row. Among evidence against Perry was his DNA on a cigarette butt beneath one of the victims. Perry also argued on appeal that a fellow jail inmate said Burkett took credit for the slayings. State lawyers said other courts had rejected the argument as self-serving for Perry and “rank hearsay.”

On Wednesday, Jonathan Green, 42, was spared from execution for abducting, raping and strangling a 12-year-old Montgomery County girl, Christina LeAnn Neal, a decade ago. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals said it needed more information about his claims of mental incompetence.

The next execution, scheduled for July 20, is that of Derrick Jackson for the September 1988 slaying of two Houston men.

Michael James Perry was convicted of brutally murdering 50 year old Sandra Stotler in the course of burglarizing her house. According to Perry's confession, he and his friend Jason Burkett decided to steal two cars. They identified two cars, a Camaro and Isuzu Rodeo, that belonged to the parents of another friend, Adam Stotler. Perry and Burkett made a plan to spend the night at the Stotler house and steal a car in the middle of the night.

On October 24, 2001, Perry and Burkett drove to the Stotler house with a 12-gauge shotgun in a blue Chevy truck belonging to Burkett's girlfriend, Kristin Willis. Sandra Stotler, Adam's mother, told Perry and Burkett that Adam would not be home until 9 pm. They returned to their truck and drove several blocks before deciding that it would be easier to steal the car when only one person was home. When they arrived back at the house, Burkett knocked on the front door and asked to use the phone. Perry then went into the house through the back door in the garage with the shotgun and hid in the laundry room. Perry knocked on the back door. When Sandra Stotler went to the back door, Perry came out of the laundry room and shot her in her side. Sandra Stotler fell, then tried to get up, and Perry shot her again.

At this point, Perry and Burkett wrapped her in bedsheets and blankets and loaded her into the back of the truck. As they could not find the keys to the Camaro, both Perry and Burkett left in Willis's truck. Burkett drove the car to nearby Crater Lake. At first, Burkett and Perry opened the tailgate and tried backing up to the lake, hoping that Sandra Stotler's body would slide out. When that did not work, they grabbed her body and rolled her into the water. They covered her body with the sheets, sticks, and brush.

Burkett and Perry drove to pick up Willis from work and returned to the Stotler house. When 16 year old Adam Stotler arrived back at his house with his friend 18 year old Jeremy Richardson, Burkett and Perry convinced them that a friend had been shot in the woods and needed their help. Adam and Jeremy followed Willis's truck in Adam's Isuzu. When they arrived in the woods, Perry and Burkett led Adam and Jeremy into the woods. According to Perry, Burkett shot Jeremy and then Adam. Perry removed the car keys and wallet from Adam's pocket. Burkett and Perry returned to the truck. Willis asked what had happened, became upset, and left in her truck. Burkett and Perry stole the Camaro and Isuzu.

Perry ended his confession by stating that they returned home, cleaned up, and went to a bar. Two days later, Perry attempted to evade police who had tried to stop him for traffic violations. The high speed chase ended when Perry wrecked the Camaro and fled on foot. He was eventually apprehended with Adam Stotler's wallet. He was booked and released on bond as Adam Stotler. The next day, Sandra Stotler's body was found in Crater Lake.

Several days later, while in the stolen Isuzu, Perry and Burkett ran into a deputy sheriff's vehicle while trying to escape arrest. The vehicle crashed into a nearby store. Burkett and Perry were arrested hiding in a neighboring apartment complex; the shotgun used to kill Sandra Stotler was also found there. Forensic evidence found near Crater Lake, in the woods, and at the Stotler residence matched Perry's confession.

Perry was tried for Sandra Stotler's murder. During his trial, Perry took the stand in his defense and claimed that his confession had been untrue. Perry, however, had made several subsequent statements that implicated him in the murder.

At the sentencing phase, the defense presented extensive evidence about Perry's family history and upbringing. An adopted child, Perry had been diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder ("ADD") at 8 years old. He was later diagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder. A year after that, he was diagnosed with conduct disorder. Perry twice tested negative for bipolar disorder after being admitted to a mental hospital. He never qualified for special education classes in elementary school, had an IQ of 97, and was by all accounts an average student.

Perry often ran away from home. He stopped going to school in junior high. He stole his mother's jewelry and the family car. He broke into a neighbor's home and destroyed the moldings. Perry's parents filed charges and had him committed to a long-term facility for mental health care. He was sent to Boys Town in Nebraska, but after threatening his house parents, he was moved to a locked facility within the program. Perry's problems did not qualify him for any mental health care provided by the facility. When he was expelled from Boys Town, his parents moved him to a secured high school campus in Mexico called Casa by the Sea. After high school, Perry was essentially homeless and jobless. He had a brief stint in the Job Corps, laying tile, and at Wal-Mart. Perry also stole and sold prescription pills to support his indulgence in alcohol and pills.

The defense presented testimony from Perry's biological mother who testified that she used drugs and alcohol until a month or two before Perry was born. Despite this, Perry was full weight and healthy when born. Although no biological relatives had committed murder, Perry's mother testified to a family history of depression, alcoholism, drug use, and thievery. Dr. Gilda Kessner, a clinical psychologist with a forensics background, interviewed Perry and testified that Perry's youthfulness was his greatest risk factor for recidivism. After serving time in prison, Dr. Kessner testified, the likelihood of Perry's becoming violent would drop to zero. The jury found Perry guilty of capital murder. During the sentencing phase, the jury found that Perry posed a continuing threat to society and that there were not sufficient mitigating circumstances to warrant a life sentence. The trial court sentenced Perry to death.

Montgomery County Police Reporter

"One of Montgomery County's Worst Murderers Executed in Huntsville," by Scott Engle. (July 2, 2010)

Michael James Perry, age 28 was executed just after 6p.m. Thursday night for the October 24, 2001 murder of Conroe Regional Hospital nurse Sandra Stotler, age 50. Also murdered that night were Stotlers step-grandson who she adopted at six-months old and raised as a son, James and his friend Jeremy Richardson.

Michael Perry was actually pulled over in Stotler’s red Camaro and arrested a few days later. He however told police his name was James Stotler and was released on bond. The very next day a fisherman was at Crater Lake in Grangerland when they snagged a blanket containing Sandra Stotler’s body. The body had been taken there by Perry and Burkett after they murdered Sandra Stotler in her home and used Burkett’s girlfriends truck.

Since Stotler was not known to be missing, police started the task of attempting to identify her. The next morning a co-worker notified officials that Sandra Stotler had not been at work for several days, as deputies checked her home they found blood. Having other information the Sheriff’s Department now starts a manhunt for Jason Burkett and Michael Perry and a Isuzu Rodeo that was also owned by the Stotler’s.

The following day, October 30, 2001 the Rodeo was ispotted behind Ronnies Truck Stop near the Harris/Montgomery County line on Interstate 45 south. As the two tried to flee they hit a deputy and ran into the building as shots were exchanged using the murder weapon, a shotgun stolen from a Conroe resident. Burkett was shot in the exchange but both suspects then fled on foot to the Wildwood Forest Apartments around the corner where Burkett lived and were taken into custody.

Burkett told police where the bodies of Sandra Stotler’s son James age 16 is and also his friend Jeremy Richardson age 18 were and lead them to the Montgomery Trace Subdivision. It was determined the motive for the murders was they wanted Sandra Stotlers Camaro.

In 2003 when Burkett came to trial, his girlfried Kristen Willis testified that Perry and Burkett picked her up at work in her pickup which they had been driving that day. They then went to Sandra Stotler’s gated community of Highland Ranch and not having the gate code waited for James and Jeremy to arrive. When they did Perry got out to talk to them a short time then had them follow them to a dirt road off Honea-Egypt and all four males got out to talk. There was a single shot and Perry and Burkett returned to the truck. At this point she left them as they drove the Rodeo. Deputies later found Sandra Stotlers blood in the truck.

Perry was only convicted of Sandra Stotlers death, the jurors never heard of the other two murders until the punishment phase of the trial.

Burkett’s trial consisted of the jury hearing and seeing the evidence on all three murders. He received life in prison in which he could parole in 40 years. Steve Jackson who defended Burkett commented after the trial that a Supreme Court opinion said one person could not be given life and the other death and felt Perry had a chance to appeal his death sentence. Jackson felt that since he represented Burkett and got a life sentence it was a victory being this was the biggest murder case in Montgomery County.

Perry’s last meal request consisted of three bacon,egg, cheese omelets. In addition three chicken cheese enchiladas and 3 each of Pepsi, Coke and Dr. Pepper.

At 6:02 Perry was strapped to the gurney and at 6:03 the solution started to flow. Then at 6:08 he gave his final statement, “I want to start off by saying and letting everyone involved in this atrocity know they’re all forgiven by me.” Looking at his mother said, “Mom, I love you.” He then said to the warden,”I am ready to go.” “Coming home dad, coming home dad.” The lethal dose was then started and continued until 6:12. He was pronounced dead at 6:17p.m.

“I felt sorry for his family,” said Lisa Stotler Balloun, Sandra Stotler’s daughter and Adam’s sister. “It’s not a good day for anyone. When he said he forgave us, I knew justice had been served today. I needed to see if he’s a monster – and apparently he is. “I just wish Jason Burkett and Kristin Willis were here sitting beside him.”

My Personal Thoughts

I do a lot of thinking & writing, sitting here on death row.

I've asked my friend to put these on my web site.

If nothing else, I hope they cause you to do some thinking, too.

Sincerely, Michael Perry

False Confessions Background Reading:

Executed On A Technicality by Professor David Dow and The Social Psychology Of False Confessions by Saul M. Kassin and Katherine L. Kiechel

Ask yourself a question, if you would. When you hear that someone has confessed to a crime, then they take their confession back and claim that they are innocent, what is the first thing that comes to your mind? Is it that he/she is guilty? I’m willing to bet that 8 out of every 10 people that are asked this question answered that way. But, why is this? Is it because you do not wish to take the time to see if there are other circumstances that might dictate he confessed? Or is it because you just do not care?…

Because so many have the mind-set that if a person confesses, they are guilty. Innocent people are not just in prison doing time for a crime they did not do, but are being murdered as well. At least 123 people have been released from prison due to actual innocence, and many of those individuals confessed to the crimes.

In New Jersey, a man confessed to kidnapping an 8-year-old girl, only to later be released, after DNA and fingerprints analysis proved that it was another man. When asked why he confessed, his answer was “"I don’t know."… and neither do we. What we DO know, without a doubt, is that people for various reasons do confess to crimes that they did not commit. In the following I hope to show some of those reasons, and also give an example.

In 1989, the “Central Park Jogger” case became famous for the brutality of the crime that 5 kids all under the age of 17 committed. They were charged and convicted of the brutal rape and murder of a young white investment banker. And they all confessed on video tape. Here is parts of their interview:

(14 year-old Raymond Santana): Questioner: "When you went into the park that night, why did you go into the park?" Raymond Santana: "Cause I thought we were going to beat people up, take bikes and get money." Questioner: "You went into the park to beat people up, to take bikes, and..." Raymond Santana: "Rob people and get money."

(Here is what 16-year-old Kharey Wise had to say about the crime.): Kharey Wise: "Oh man, blood was scattered all over the place. I couldn't look at it no more. Like I said, I did it not just to prove myself because I don't prove myself for nobody. I just did it because we went to the park." Questioner: "To do what?" Kharey Wise: "For trouble. We went to the park for trouble and got trouble, a lot of trouble. That's what they wanted and I guess that's what I wanted. When I was doing it, that's what I wanted too. I can't apologize because it's too late. Now we got to pay for what we did."

And that's exactly what they did. They paid for being young, they paid for being scared, confused, manipulated, tired. They paid with years of their life that can never be replaced. In this case there were two crimes committed. The crime of murder and the crime of making innocent children serve time for a crime they never committed. The system failed these children. Antron McCray, who was only 16 at the time, had this to say on tape after 22 hours of questions: Questioner: "What happened when she came closer?" Antron McCray: "That's when we all charged her." Questioner: "Did you charge her?" Antron McCray: "Mm-hmm." Questioner: "And who else charged her?" Antron McCray: "Everybody. Everybody that was there." Questioner: "What happened when you charged her?" Antron McCray: "We charged her. She was on the ground. Everybody stomping and everything."

Antron McCray, who had an I.Q. of 87, served 6 years; Kevin Richardson, then 14, served 6 years and 6 months in prison; Yusef Salaam, then 15, also served 6 and a half years; Kharey Wise, the only one who was charged as an adult, spent 11 and a half years in prison and Raymond Santana served 8 years in prison. Everyone, including these five, thought that was the end of it, until Mathias Reyes, a convicted murderer and serial rapist, confessed. He says, he and he alone raped and beat the victim. Here he is in an interview with ABC News correspondent Cynthia McFadden: Cynthia McFadden: "Did you do it alone?" Mathias Reyes: "Mm-hmm, absolutely." Cynthia McFadden: "Did you rape her?" Mathias Reyes: "Yes." Cynthia McFadden: "Did you beat her?" Mathias Reyes: "Mm-hmm." Cynthia McFadden: "Did you leave her for dead?" Mathias Reyes: I thought I left her for dead."

Reyes's DNA matched that found on the jogger's clothing. Besides for this, after the the D.A. re-opened the case, he found troubling discrepancies in the video- taped confessions. Kevin Richardson said in his taped confession that the victim screamed "help" and "stop" a lot, and that nobody gagged her. He also said that nobody tied up her hands. However, the record shows that when the jogger was found, here hands were bound and the was gagged with her own t-shirt.

Studies show that when a person confesses to a crime, they actually feel that they will be allowed to go home if they do so. But why is that? Since childhood you are taught that if you did not do anything wrong there is nothing you have to worry about. Many confess with the belief that since they did not do it, the proof will show this and they will go home.

Barry Scheck, in an interview in 2002, said that there are 122 post- conviction exonerations revolving around DNA, and in 35 of those cases there were false confessions. That's 35 people out of 122 who were innocent of the crime, but confessed to it anyway! Yet, people still choose to believe automatically that when someone confesses, they are guilty...

To further prove that false confessions occur, here are some facts taken from a research article by Saul M. Kassin and Katherine L. Kiechel, entitled The Social Psychology Of False Confessions.

In this article, the authors speak of a psychological experiment involving students working in pairs supervised by a teacher. One student of every pair sat in front of a computer while their partner called out letters for them to type. At the beginning of the experiment, the teacher warned the students NOT to press the ALT key, because doing so would cause the program to crash and data to be lost. What the students did not know was that some of the computers had been manipulated in a way that they would crash after 60 seconds WITHOUT anyone even getting near the ALT key. The teacher, who had previously been instructed to accuse students of not following his instructions, would reprimand the typing student of a pair. When he/she professed their innocence, the teacher would sometimes turn to the partner and ask if he/she had seen anything. On occasion, pre-arranged, some of them would admit seeing their partner push the ALT key. For those students who had their partner claim they had seen them doing it, the teacher wrote out a confession that said "I hit the ALT key and caused the program to crash. Data was lost." The "guilty" students then were asked to sign the confession, the consequence of which would be a phone call from the principal investigator. If the student refused, the request was asked a second time.

When the teacher and the subject of this experiment left the room to go to his office, they were met by another student who had yet to go through this experiment. When the teacher went inside his office he left the two outside to talk. Their conversation was secretly recorded. The new student asked the one who had come with the teacher "What happened?". And the subject responded "I hit the wrong button and ruined the program." In some of the experiments the student was heard to say "I hit a button I wasn't supposed to." Even though no one hit a wrong button, they just "confessed" to it. Had this been a murder, they would find themselves getting arrested and sentenced... In their recorded conversations in front of the teacher's office 96% out of 79 students "confessed" they had touched the wrong button although none of them actually had. After this phase of the experiment, the teacher would bring the accused subjects back to the computer and asked them if they could reconstruct how or when they hit the ALT key. Many said "Yes, here, I hit it with the side of my hand right after the "a" was called out." In this part of the experiment, all 79 students were able to show the teacher where they had pushed the ALT key. Once again, none of them had.

Overall, 69% of the students signed a confession. None of these students had pushed the button, so why did they confess? The teacher specifically used certain techniques used by the police when interviewing witnesses to see the effects they had. As we can see, the effects are false confessions. The teacher studied the manual the police use to train their detectives and used exactly the same techniques that they use.

Now imagine how many people sit behind bars because of these techniques. Some of these wrongly accused "confessors" have been murdered, others are awaiting death. Yet many people are still content with believing that because someone confessed, they are guilty... What a humane society we live in!

Let me give you yet another example: In Texas, in the case of Cesar Fierro, his parents lived in Mexico, but he was in El Paso. Cesar was suspect in a murder, he would not confess, so his parents were dragged to the police station in Mexcio, where they were beaten and tortured. Cesar was put on the phone and "allowed" to listen to his mother's cries of agony and pain, as they hit her with clubs, kicked her with steel-capped boots... Even worse, his father had a chacharra, a device similar to an electric cattle prod, placed on his genitals, while his son was made to listen to his screams. Cesar ended up confessing because he wanted his parents' agony to stop. Now he is on Texas Death Row and has lost his mind. I, personally, have been his cell neighbor, and listened to him mumble to himself, howl at the moon, scream, spit, cry, kick the door, wall, etc. He does not understand what people are trying to tell him, he cannot hold a conversation. The system has not only failed this man, it has ruined him...

I could go on forever about false confessions, site research and cases, to help prove my message, but the bottom line is, are YOU willing to believe? If you are closed to the subject, no amount of proof will change your mind. You must be willing to open your eyes and realize that our system is broken, and in some places, like the death penalty, beyond repair. Are you open??

I was falsely accused and sentenced for murder. The police beat, choked and pistol- whipped a confession out of me. But I do not ask anyone to simply believe my words, rather the FACTS that surround my case. They speak for themselves. Once a person is able to see through the propaganda, the truth is as bright and clear as the sun. So, put on your shades and join the fight, join a cause that will make a difference, that will save a life. My name is Michael Perry, I am 24 and I have been locked up in a cage since I was 19... I do not wish to die. Will you help??

Michael James Perry #999444

Inhumanity in a Humane Society By Michael Perry

What else is there to do? What else can "we" say? What is it going to take for "us" to project what is going on in Texas? Is there anything "we" can do? Is there anything "we" can say? Do "we" waste our words, so in turn, your time? Regardless, I continue the fight. "We" continue the fight for justice...that wonderful word that all Americans are entitled to. That word that separates this country from so may others. That word "we" (in here) can only dream about. When referring to Justice you will see that I refer to it as a word, rather than a thing or action. This is because until I see true Justice being done, I can only speak about it.

Who is "we" you may ask. "We" are the many incarcerated falsely. The many that face execution as a result of overzealous prosecution, and at the hands of the state, for a crime they never committed. This is who "we" are...the innocent.

I have sat at this concrete desk on countless occasions with pen in hand and legal papers spread out all over my tiny 7 x 10 cage, doing exactly what I am doing now...as have many others imprisoned here. The difference, this time, is I am finished speaking with big words or legal terms. I am done speaking in that language that, at times, baffles even the smartest of people. I know it has had me scratching my head on several occasions. I am here now trying to speak in the universal language, the language of humanity.

Let me define this great word: Humanity: the quality or state of being human or humane; the branches of learning, dealing with human concerns (as philosophy), as opposed to natural processes (as in physics). Humane: marked by compassion, sympathy, or consideration for others.

So, now what am I talking about? How does this apply? Many in Texas and across the world take the attitude that since it does not directly concern them, why get involved? With this attitude comes different definitions. Inhumanity - the quality or state of being cruel or barbarous; a cruel or barbarous act. Inhumane: not humane, inhuman. In theory, to not get involved is not to care and that falls close to the definition of inhumanity! Something to think about...

Yes, I will probably offend some people with this article. Some might even get angry. Good! At least I will be getting some response! You tell me, who should be more angry? You or the innocent man or woman that has been taken from their family? Someone who has basically had their lives taken from them, been locked in this tiny cage, treated like an animal. Then years later, strapped to a gurney and shoved full of chemicals that have been found to be cruel to give an animal!

Now, don't get me wrong. In no way do I feel that all or even a big percentage of Death Row prisoners are innocent. I have been here 31 months and I might have met 3 people I feel are actually innocent. I've met many who probably do belong behind bars and some will tell you so. But NONE belong here. The Ultimate Punishment, death, is for God and God alone to hand out. I know that the "powers that be" in Texas sometimes confuse themselves with God, but that does not make it right. They, too, will be judged someday. Believe that...

Isn't one person executed, later found out to be innocent, too many? How many will it take to get YOU involved? Do I have to be "murdered" first? Isn't that what you call the taking of an innocent life? It has been PROVEN that they have executed innocent people, yet it continues to be accepted. Brian Roberts says it best when he says, "The death penalty in America is not merely flawed. It is broken and beyond repair. For every eight people that have been executed in the U.S. during the past three decades, one person has been found to be ACTUALLY INNOCENT. The 112 people found to be actually innocent were not released due to what some might call a legal technicality - flawed jury instruction, for example - but because THEY ACTUALLY DID NOT DO THE CRIME!"

People tend to forget, Jesus was an Innocent man on Death row and was executed. These are quotes and information from Brian Roberts, the Executive Director of the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty. He states that ten people were freed from death row, due to "actual innocence" in 2003. So, is it possible to be an innocent on death row? Yes, of course! I AM!!!

To get back on track, I am strictly speaking about the innocent people here on death row. Some will tell you this cannot happen, but it is not only possible, it has and is happening. How? That should be the question people are asking. And what can we do to stop it? Well...

When you have a county where the entire crime lab is shut down due to faulty evidence, and other counties where the sheriff is under investigation for covering up a rape that one of his lieutenants was reportedly involved in, it is easy to believe. It is even easier to believe when you have prosecutors themselves coming out in public and admitting they lied and put up false evidence to get a conviction. How could you not believe there are innocent people on death row? Then you sit back and say, "Hey, that's what the appeals process is for - right?" Do you even know about the appeals process? Here are some quotes you may find interesting...

The Court of Criminal Appeals (CCA), headed by Chief Justice of Executions Sharon Kellar, was asked in the filming of a controversial debate, how could a person prove their innocence in her court? This question came after her court refused to accept the result of a DNA test which conclusively proved a defendant's innocence. Her response? "I don't know." If she doesn't know, who does? How about this quote from Chuck Rosenthal, District Attorney for Harris County, after the closing of the crime lab. "There has been no Harris County cases where a defendant has been executed and there was possible faulty evidence." Isn't shutting down your entire crime lab an admittance of faulty evidence?

This is the most important quote I want to bring to your attention. This highlights everything we have been trying to get across to the public. "Let's say you have a video tape which conclusively shows the suspect is innocent. Is it a Federal Constitutional Violation to execute this person?" United States Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy asked Texas Assistant Attorney General Margaret Griffey, as she argued the case of Texas Death Row inmate Leonell Herrera, shortly before he was executed. "NO! It would not be violative of the Constitution," she sternly replied.

How then, may I ask, can we expect justice? If the Chief Justice of Executions in the CCA states that she doesn't know how one can prove their innocence, and a Texas Assistant Attorney General states that even if a crime was caught on tape, and the tape shows a man did not do it, they can still execute that man, does that make any sense to anyone?

If we life in a society that can allow the murder of innocent people, then how can we expect any type of justice? How can we call ourselves aHumane Society? I am an innocent man on death row. I do not belong here. And because people judge me for where I am, because politics - and not justice - runs the system, I might lose my life.

This is my petition for help, for support, for a friend. I am no monster, like the court would have you believe. I am a poet, an artist, a loving and caring son to some amazing people I'm blessed to call Mom and Dad. I invite you into our lives, our world. There is nothing I will not disclose. I have no fear of the truth. You may ask me anything and I will make all documents available. I will refer you to other cases that I feel are under this Actual Innocence claim., You may talk to my attorneys, my parents, my friends, and other supporters. I am as normal as you are. I only differ in the fact that I live in fear that you, the public, might not support me in my fight for True Justice. I am asking to live...is that so much to have a wrong made right?

I ask that you put yourself in my shoes for a moment. If you do nothing else, do this. Picture yourself as an innocent man, sitting inside a cold, lonely 7 x 10 cage. Guards constantly harass and taunt you, being forced to eat food not suitable for your pets. Picture yourself here, what would you do? How would you feel? Especially when you know you are innocent? Your friends and family know you're innocent. You can even prove that you are innocent, but the courts tell you that innocence has"no place in the appeals process" and they send you down the line...

This is my CRY FOR HELP! I don't want to die. I'm only 23 years old, locked up since I was 19. My life has been taken away from me, stolen, ruined! Help me save my life...reach out a hand.

My name is Michael James Perry. I am a 23 year old loving, caring son of God. I am innocent on Death Row. Will you help me? In heart and struggle, I remain

Michael James Perry #999444

"It is better for a leader to make a mistake in forgiving than to make a mistake in punishing" (Al-Trimidhi, Hadith 1011) If you had a chance to save someone from being murdered, to what extent would you go, to help save that person? And if a man was condemned for a crime which he did not commit, would you still want to stop his murder? Is there a difference?? How can we call ourselves a humane society, when we so easily turn our backs when the innocent are murdered? Can you sleep easily at night, with the knowledge that another human being is being "murdered"? And possibly for a crime they did not commit?? And if you can, what does that say about a person's morales??... With this, comes a question... if I may... How do you stand on the "Death Penalty"? And, what knowledge of it, did you bring to the table, in order to make a decision? For sadly I find that many today, "judge a book by its cover", so to speak, and don't take the time or effort, to see the truth of the situation... And considering how black and white it has become, this is disturbing...

I would like to take some time to explain what I am speaking of, so that you may have a better understanding of the situation... Unfortunately, I am very new to this, and am not the best when it comes to expressing myself, so please bear with me...

There are many out there, I feel, that are unaware of that is really going on, and therefore are "unenlightened" to what the death penalty is really about. They see our fight as a last chance to save our lives and nothing more... Sadly, some might even believe some [people on death row are] actually innocent, but "bad" people anyway, so good riddance... But should one be "MURDERED" for a false image, created through propaganda?? And even those that profess to be against the death-penalty, are more often than not confused as to what exactly they can do for a person in our situation, sitting on death row, trying to find "justice" in a system where the odds are already stacked against us.

However, this is for all of those people out there that are unaware to the injustice that has crept its way into our system... Texas alone executed 24 people in 2003. A small number when looked at alone. But what some don't realize, is that that represents almost 40% of all the executions in the U.S.! In Texas alone!? In 2003, we also saw more corruption in the use of the Death Penalty, than ever before, and the revelations of corruption only continue... to stack up.

In January of 2003, "Governor Ryan" exonerated 4 people from Illinois Death Row, after discovering evidence that led him to believe that they were "beat" into giving confessions. Beat and tortured by the same people paid to protect and serve. The Police....! He commuted 167 death sentences to life! On January 11th, 2003, he stated: "The facts I have seen in reviewing each and every one of these cases raised questions. Not only about the innocence of people on Death Row, but about the fairness of the death penalty as a whole. The legislature couldn't reform it, I must act. Our capital system is haunted by the demon of error, error in determining who among the guilty deserves to die. Because of all these reasons today, I am commuting the sentences of all death row inmates..."

This is part of a speech made by a U.S. Governor who recognized the severe faults in the system, and took the bold step to do something about it. If only people of Power in Texas were as bold...

Yet, this isn't even the beginning... On March 12th, 2003, Delma Banks, was given a "stay" 10 minutes before he was to be executed. Evidence has come about that 2 key witnesses lied at his trial. One was promised that previous drug charges would be dropped, if he would testify to what the D.A. wished?! The other was paid to lie at Banks' trial!? But, do you truly understand how serious this really is?? They found that the D.A.'s office KNEW about this... They in fact set this up?! The prosecutor has come clean in admitting his faults... Banks now has the support of former FBI Director William Sessions, ex Judges, and prosecutors, yet the "STATE of Texas" refuses to admit fault, and continues to try and MURDER this man?? Law dictates he be given a new trial, or released, yet Texas once again refuses...? I can only imagine how the Attorney General, the highest seat of Law in a state, can continue to pursue this, when his own prosecutor admits fault?? We can only pray for Mr. Banks, and hope that Justice wins in his case...

The list goes on... You would think, that in a state that has been severely criticized for providing ineffective counsel to its defendants, that they would learn, and move to fix the problem. You would hope... Not in Texas... Once again, there arises a case there a attorney fell asleep while in hearing?? On August 15th, George McForland had a evidentory hearing, where it was proven that his attorney did nothing, while waiting for the other-one to wake-up!? These are the attorneys "appointed" to defend us? And we are expected to prove our innocence, with a sleeping attorney?

What's even more disturbing, is the fact that after one inmate won a new trial, and eventually a life sentence, because of the fact that his attorney fell asleep, the Attorney Generals office challenged this? So what exactly is the state of Texas trying to say, that it's OK for our attorneys to fall asleep?...Justice...?

Then on September 26th, Howard Guidry was given a new trial order, after it was proven that detectives in his case refused to let him speak to his attorney...(So much for "rights"). Not only did the detectives refuse him his right, they lied to him... After hearing him repeatedly request for an attorney, they left and when they returned, they told him his attorney called and said for him to talk to the detectives!? And once again the Attorney General's office is fighting this ruling?? So, are they saying it's ok to lie to us, and refuse us our rights??... America... home of the free?? So we once believed.

Then there is the case where Walter Bell, who is mentally retarded, was completely manipulated. When Mr. Bell first went to trial, the D.A. office used the fact that he was mentally retarded to secure a death sentence... But now that it has been made unconstitutional to execute someone who is mentally retarded, they have changed their story, and now say that he is not retarded?? These are the people who have been elected to uphold "truths"?... Justice...?

Then comes some extremely disturbing news... According to Brian Roberts, Executive Director of the NCADP, 10 people were released in 2003 due to actual innocence... This fact alone should prove that there are some major problems and flaws in our system. Yet the murders continue... "The death penalty in America is not merely flawed, it is broken and beyond repair," says Brian. "For every eight people that have been executed in the U.S. during the past three decades, one person has been found actually innocent. The 112 people found to be innocent were not released due to what some might call a legal technicality- flawed jury instruction, for example-but because they actually did not do the crime."

Another fact that I have found disturbing, is that many people don't even realize what can get you on Death Row... if asked, most will say murder.. But Texas is one of the few states that MURDERS its prisoners under what is called the "Law of Parties." Under this, knowledge alone can put you here with me, on Death Row... In my case, my co-defendant, Jason Aaron Burkett, was convicted of killing 3 people, yet he is in population, and I am to be murdered??...

Then, there's Arroyo vs. State, in his case, he asked some neighborhood thieves to look out for a part of his car... A month or so later, they found it... But killed someone to get it... Yet, Arroyo sits on Death Row, and the people who killed a man, sit in population??... Justice...?

So those who believe in, "Eye for an Eye..." I ask what about those of us that were simply at the wrong place at the wrong time? And, got brought down under Texas Law of Parties?... And if we were to follow Eye for an Eye, how many today would be free or alive? After all that was done in the "Slave Years"... Eye for an Eye? Or only when it benefits those in power?...

To be continued...

A "Higher Law"

Through this past year, I have learned a man can have knowledge and the world at his fingertips, but if he has no morals, he will only self-destruct. If he has no love, he will only wither away. If he has no desire or purpose, he will only make excuses for his failings... I have recently read the Life of Martin Luther King, Jr. to give myself a full range of knowledge. While reading, I realized that the heart of our problems are the problems of our hearts. Martin Luther King, Jr. once proclaimed, "I have seen too much hate to want to hate." As I sit back and reflect on this, from my tiny "cage" on Texas Death Row, I have to agree...

There's a higher law - a law of love - on the other side of the law. How others see us is never the true depiction of us, but it is how we see others... When I think of Tookie Williams, the original founder of the notorious gang "The Crips," being nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize for his writings of childrens books from a California Death Row cell...or Sonny Ray Jeffries, scribbling poems, shedding light and creativity from a Florida death row cell...I understand the Higher Law of love. Higher than the Laws of the State...

I often compare Death Row to falling deep into the ocean, then rising slowly to the surface, to tell the story of how you almost drowned. Instead, you tell a story of all the hidden treasure you found that no one knew was down there. Like Dr. King, I have seen too much hate to want to hate. I've seen too many give up on me to want to give up on others. And I have seen and been through too much pain in my life to want to see others in pain...

I was talking to someone I consider my "mentor" the other day. And he told me a story of the Higher Law that affected me. He told me that after he was found guilty, after he was labled a "cold-blooded killer," and defamed by the media, he was led back to his "cage," where he dropped to his knees, and slowly flooded the cell with his tears... The guard, seeing this, went and got his family, breaking ALL rules, and probably a couple of "laws," let his family in the cell to have one last visit. My friend told me that he will never forget about that guard, allowing him that precious last visit. And I will never forget the story.

There will always be the "Higher Law" of Love higher than the Laws of State. I have lived by that "higher love" on the other side of the law, where mercy triumphs over judgement...

The state judges us, believing judgement is greater than mercy. When in reality, judgement isn't theirs to hand out. The death penalty needs to be abolished. NO SUBSTITUTES. But if, regardless of my innocence, I am to be executed, I am ready, if it will help others today, change what others of the past, have put in place. If I don't humble myself, my life is in vain, and over already. There's nothing worse for a man's heart than living in vain or dying in vain. But, if we love today, we will never hate tomorrow...

I have seen too much hate, to want to hate... And not enough love, to want to love...

Perry v. State, 158 S.W.3d 438 (Tex.Crim.App. 2004). (Direct Appeal)

Background: Defendant was convicted in the District Court, Montgomery County, Suzanne Stovall, J., of capital murder and was sentenced to death. Defendant appealed.

Holdings: The Court of Criminal Appeals, Hervey, J., held that: (1) evidence of intoxication and injury did not raise any constitutional voluntariness issues regarding confession, and (2) instruction that the State is required to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the capital sentencing jury should answer “no” to the mitigation special issue is not warranted. Affirmed.

HERVEY, J., delivered the opinion of the Court in which KELLER, PJ., MEYERS, PRICE, WOMACK, KEASLER, HOLCOMB, and COCHRAN, JJ., joined.

A jury convicted appellant of capital murder. The trial court sentenced appellant to death pursuant to the jury's answers to the special issues submitted at the punishment phase. Appellant raises seven points of error in his original brief and another point of error in a supplemental brief. We affirm.

Appellant does not challenge the sufficiency of the evidence to support his conviction. The evidence shows that appellant murdered the victim by shooting her with a shotgun while appellant and another person were burglarizing her home. Later that night appellant was involved in the murder of this victim's son and another person. Appellant was arrested about a week later in an apartment where he had fled following a high-speed car-chase with the police during which appellant injured his arm, and one of the other occupants in the car was shot by the police in an exchange of gunfire. The injury to appellant's arm was serious enough to require treatment at a hospital. The police obtained a written confession from appellant at the hospital.

Appellant was charged and tried only for the murder of the mother during the burglary of her home. Appellant testified at the guilt/innocence phase that he was not involved in this murder and that his confession was not true. The following portion of appellant's confession was admitted into evidence at the guilt/innocence phase:

Last week, the week of October 22-26, my friend, Jason Burkett, and I decided we needed to get a vehicle, or two vehicles. We both know a younger white male [the burglary victim's son], known to us as Adam Stotler whose parents have a lot of money. They also have a newer Camaro and Isuzu Rodeo.

On Wednesday 10-24-01 Jason and I made a plan that we were going to ask to spend the night with Adam at his house, and we were going to take the Camaro in the middle of the night while Adam and his mom was [sic] sleeping. We went to Adam's house at about 7 pm on Wednesday 10-24-01. Jason was driving his girlfriend, Kristen Ranel's, blue Chevy truck, and I was riding in the passenger seat. We had a 12 gauge shotgun with us. Jason and I got to Adams [sic] house, and his mom told us that Adam was not home, that he was at the skate park and would be home around 9 pm.

Jason and I left in the truck, but before we got out of the subdivision, Jason said that it would be easier to get the car with only one person home. Jason and I then made a plan that Jason would knock on the front door, and I would sneak in the back door, through the garage with the shotgun. We went to Adam's house on foot and left Kristen's truck down the road. I walked around to the side of the house through the garage, and Jason knocked on the front door and asked to use the phone. When I heard Jason talking on the phone, I went into the house through the back door in the garage. Once in the house, I hid in the laundry room between the kitchen and garage. I then knocked on the back door, and when Adam's mom came to the back door, I shot her one time in the side near her back with the shotgun. She fell to the floor, and I dropped the shotgun.

She then moved or tried to get up or something, and I grabbed the shotgun and shot her one more time. She fell to the floor in front of the laundry room and garage, back door. Jason freaked out and ran to the front door and opened the door. We calmed down a little and grabbed the blankets and sheet off of the bed in the bedroom near the kitchen and put the blankets and sheet over her because we did not want to look at her. Jason ran and got Kristen's truck and brought it back to Adam's house. Jason backed the truck into the garage, and we dragged Adam's mom's body and the blankets out into the garage, where we loaded her into the back of the truck with the blankets and sheet. I could not find the keys to the Camaro, and I remembered that the inspection sticker was expired, and Adam's mom never drove it.

Jason then got into the drivers [sic] side of the truck and I got in the passenger seat, and Jason drove to an area he called Crater Lake. I did not know where Crater Lake was, but I remember driving down a dirt road, then going across a big bump and seeing some type of pipeline or something. We then drove down a cleared road and saw an old stripped out truck blocking the road. The road to what Jason called Crater Lake was off to the left of the stripped truck. Jason turned the truck around and first tried to open the tailgate, speed backwards toward the pond, and try to slam on the brakes to get the body to slide out. He did that I think twice, but it would not work so we grabbed her body, and we rolled her down into the water. Jason and I then threw sheets into the water on top of her and covered her up with some sticks and brush we found near by. It was about 8:20-8:30 pm by that time, and we drove to pick up Kristen, where she works at Big Dog Sports at the Outlet Mall in Conroe.

I jumped the fence and ran to Adam's house. I got in the Camaro, which was parked in the garage and drove it out of the garage. I pressed the button to close the garage door, but it would not close so I drove off. I drove out of the gate, met Jason, and we left to go to our trailer. Jason drove the white Isuzu with the shotgun in it, and I drove the red Camaro. We went home, smoked several cigarettes, and then got cleaned up and went to Nite Life.

The rest of appellant's confession was admitted into evidence at the punishment phase of the trial.

We picked up Kristen and drove back to Adam's subdivision. Jason drove, Kristen sat in the middle, and I sat on the passenger's side. We still had the shotgun with us. When we got to the subdivision, we could not get in, because we did not know the gate code. We knew that Adam would be home soon so we waited at the gate, and Adam pulled up in the white Isuzu Rodeo with another guy I know as Jeremy in the passenger seat. While Jason, Kristen, and I waited at the gate for Adam, we agreed on a story to tell Adam. Jason and I told Adam and Jeremy that a friend of ours had shot himself while we were all hunting squirrels, and we needed their help to get him.

We left the front of the subdivision and turned right onto the road in front of the subdivision. We were still in the truck, and Adam and Jeremy followed us in the Isuzu Rodeo. We then came to a stop sign and turned right. We then took the first left off that road and crossed the railroad tracks. We drove down a dark, winding road and stopped at I think was the first dirt road on the left. We all parked there, and Jason, Jeremy, Adam, and I started walking back into the woods off the dirt road. Kristen sat in her truck. After we walked awhile, Adam realized where we were and said that he knew an easier way to get to our friend.

Adam and I went back to Adams [sic] Isuzu, and Jason and Jeremy stayed in the woods. Adam drove me in his Isuzu to the 1st subdivision on the left off of the same road we were on. Adam said that there was a road that went into the area we had earlier walked to. I think we turned onto the first road on the left in that subdivision and stopped at a cul-de-sac.

Adam and I got out of the Isuzu and we saw Jason walking toward us with the shotgun. Jason asked if we heard the gunshots and said that he was trying to let us know where he was. I told him that I had heard two to three shots. Adam then walked toward Jason, who did not have Jeremy with him, and Jason told him that he (Jason) would take Adam to where the others supposedly were. I walked back to get my cigarettes, and I saw Jason shoot Adam in the left side. I then covered my eyes. I heard a second gunshot and uncovered my eyes. I then saw Jason lean in close to Adam and fire a third shot at close range. I walked over to Adams [sic] body and got his car keys out of his pocket.

Jason and I then went to the Isuzu, and Adam [sic] got in the drivers [sic] side with me in the passenger side. We went back to where Kristin [sic] was waiting, and Kristen asked Jason, “What happened” and then said, “Never mind I don't want to know.” Jason then said, “You're right, you don't want to know.” Kristen's sister called, and Kristen was upset and said she was going home. Kristen left in her truck, and Jason drove me back to Adam's subdivision.

I took the keys to the Camaro off of Adam's key ring for the Isuzu, and I jumped the fence and ran to Adam's house. I got in the Camaro, which was parked in the garage and drove it out of the garage. I pressed the button to close the garage door, but it would not close so I drove off. I drove out of the gate, met Jason, and we left to go to our trailer. Jason drove the white Isuzu with the shotgun in it, and I drove the red Camaro. We went home, smoked several cigarettes, and then got cleaned up and went to Nite Life.

The shotgun we used came from a burglary that Jason and I did on Ave. E by the Salvation Army. Jason and I both know the homeowner, and he drives a green Ford Ranger. We took a Glock .40 and a 12 gauge defender out of the house. The 12 gauge defender is the shotgun we used to kill Adam's mom, Adam Stotler, and Jeremy. I also took Adam's wallet out of his Isuzu with his driver's license.