Executed December 4, 2012 06:07 p.m. CDT by Lethal Injection in Oklahoma

41st murderer executed in U.S. in 2012

1318th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

10th murderer executed in Oklahoma in 2012

102nd murderer executed in Oklahoma since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(41) |

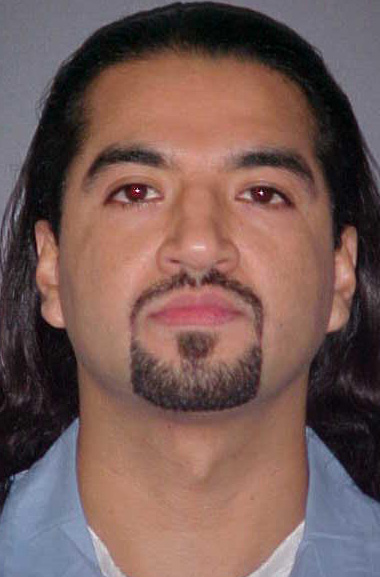

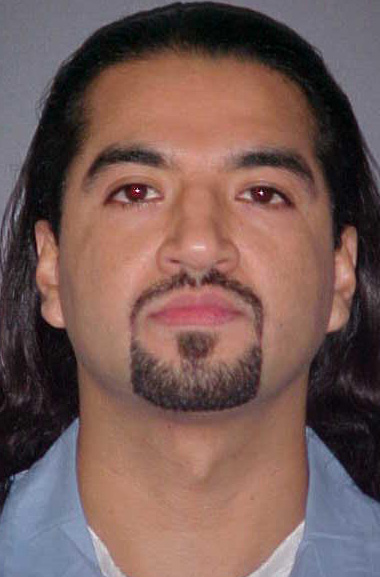

George Ochoa H / M / 21 - 38 |

Francisco Morales H / M / 38 Maria Yanez H / F / 35 |

Citations:

Ochoa v. State, 963 P.2d 583 (Okla.Crim. App. 1998). (Direct Appeal)

Ochoa v. State, 136 P.3d 661 (Okla.Crim. App. 2006). (PCR)

Ochoa v. Workman, 451 Fed.Appx. 718 (10th Cir. 2011). (Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

A large meat lover’s pizza and a large Coke.

Final Words:

“I’m innocent."

Internet Sources:

Oklahoma Department of Corrections

Inmate: GEORGE OCHOA

Alias: Juan Lopez, Jorge Salaises

ODOC# 243148

Birth Date: 08/06/1974

Race: Hispanic

Sex: Male

Height: 5 ft. 09 in.

Weight: 150 pounds

Hair: Black

Eyes: Brown

Convictions:

CASE# County Offense Conviction Term Start

93-4302 OKLA Murder In The First Degree 03/21/1996 DEATH Death 04/01/1996

"Oklahoma death row inmate’s last words: 'I’m innocent'" by Rachel Petersen. (December 4, 2012

McALESTER — Death row inmate George Ochoa, 38, was the sixth inmate to be executed this year in Oklahoma. His death sentence was carried out by prison officials this evening in the death chamber at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary. Department of Corrections Director Justin Jones told prison officials inside the execution chamber to proceed with the execution process. At 6:01 p.m., the blinds covering windows between the witness room and the death chamber were raised. Ochoa raised his head from the death gurney briefly and looked into the witness room.

OSP Deputy Warden Art Lightle asked Ochoa if he had any last words. “I’m innocent,” Ochoa said. Ochoa spoke no other words other than those. At 6:02 p.m. Lightle said, “Let the execution begin.” After the lethal dose was administered to Ochoa, his eyes blinked multiple times. He chewed slightly on his lower lip. Then he lifted his head slightly. His head then came to rest back on the death gurney and his eyes closed. By 6:06 p.m., color had drained from Ochoa’s face and at 6:07 p.m., the attending physician pronounced Ochoa’s time of death.

Witnessing the execution were two media representatives, 10 Department of Corrections officials and 19 members of the victims’ family. Twelve of those 19 were in the witness chamber and the remaining witnesses watched the execution via video tele-feed from one floor below the execution chamber. Although there were five members of Ochoa’s family scheduled to witness his execution, none of those five were in the witness room when he was executed. Ochoa requested for his last meal a large meat lover’s pizza and a large Coke, which was served to him at around noon Tuesday, according to prison officials.

“Ochoa was convicted and sentenced to death for the first-degree murders of Francisco Morales, 38, and wife, Maria Yanez, 35,” said Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt in an earlier press release. “According to the report, Morales suffered 12 gunshot wounds and Yanez suffered 11 gunshot wounds while in their bedroom ... The victim’s children were in the home at the time of the murders.” According to court records, Morales and Yanez were shot and killed in their bedroom in the early morning hours of July 12, 1993. The sound of gunfire woke Yanez’s 14-year-old daughter, court records state, and she called 911 before looking out her bedroom door. “(She) saw two men,” court records state. The young girl at first denied knowing the men, but eventually identified them as Ochoa and Osvaldo Torres, court records state. The young girl’s 11-year-old step-brother saw one of the men shoot his father, court records state. Ochoa and Torres were arrested “a short distance from the homicide,” court records state. “A short time before the shootings, Torres and Ochoa parked their car at a friend’s house,” court records state. “A witness observed one of the men take a gun from the trunk of the car and put the gun in his pants.”

Both Torres and Ochoa were tried and sentenced to death for the murders. “However, in 2004, former Gov. Brad Henry commuted Torres’ sentence to life in prison without the possibility of parole,” Pruitt continues in his press release. During his 2004 clemency hearing, Torres admitted that he had planned to burglarize Morales’ and Yanez’s home. “I never killed anyone. And I never knew George was going to kill anyone.” Ochoa had been in custody with the Oklahoma Department of Corrections since April 1, 1996, less than two weeks after he was convicted in Oklahoma County of first degree murder.

"Oklahoma executes man for 1993 shootings," by Sean Murphy. (December 5, 2012 at 12:12 am)

McALESTER — A death row inmate was executed Tuesday for the 1993 shooting deaths of an Oklahoma City couple. George Ochoa, 38, was given an injection of lethal drugs at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary at McAlester. He was pronounced dead at 6:07 p.m. The punishment came less than a month after the state Pardon and Parole Board rejected Ochoa’s request that it recommend Gov. Mary Fallin reduce his death sentence to life in prison.

Ochoa is one of two men convicted of first-degree murder in the shooting deaths of Francisco Morales, 38, and Maria Yanez, 35. Investigators say Morales was shot 12 times and Yanez 11 times in their bedroom on July 12, 1993. The couple’s three children were inside the house at the time of the shootings.

Ochoa claimed he had been shocked and suffered injuries during his incarceration, but prosecutors said his claims of hallucinations and harm were likely an attempt to feign mental incompetence. Courts prohibit the execution of people who do not understand why they are being punished. Officials said earlier psychological evaluations showed no evidence of delusions or hallucinations, and that claims about such didn’t start until he was charged.

Ochoa lost a late attempt at having his execution postponed when the U.S. Supreme Court on Tuesday denied his request for a stay. A federal appeals court on Monday rejected arguments that Ochoa was mentally unfit to be executed and a challenge to the state’s procedure for determining sanity.

Prosecutors said there was little evidence to suggest a motive for the killing, but no doubt that Ochoa and his co-defendant, Osbaldo Torres, 37, were responsible. Ochoa and Torres were stopped by police near the crime scene and were described by police as “sweating and nervous,” court records show. Torres, a Mexican citizen, was also convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death in the shootings, but his sentence was reduced by then-Gov. Brad Henry in 2004. Henry imposed a sentence of life without parole after Mexican government officials raised concerns that Torres was not given a chance to speak with the Mexican consulate after being accused, as required by international conventions.

"Oklahoma to execute inmate for 1993 home-invasion killings," by Steve Olafson. (Dec 4, 2012 2:19pm EST)

OKLAHOMA CITY | (Reuters) - A man convicted of killing a couple in their bed in 1993 was scheduled to be executed on Tuesday, despite claims by his attorney that he should be spared because he is insane.

Federal courts in Oklahoma and Denver refused on Monday to stop the execution of George Ochoa, 38. He and Osbaldo Torres were convicted of first-degree murder in the shooting deaths of Francisco Morales and Maria Yanez in Oklahoma City. Ochoa would be the sixth person executed in Oklahoma in 2012 and the 41st in the United States this year if his lethal injection is carried out as scheduled at 6 p.m. CST (7 p.m. EST) at a state prison in McAlester.

U.S. District Judge David Russell of the Western District of Oklahoma and the U.S. 10th Circuit of Appeals in Denver denied last-minute claims that Ochoa's mental health had deteriorated so greatly that he should not be executed. Ochoa's appeals have focused on his mental state since the 2002 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that mentally incompetent people cannot be put to death. His attorney, James Hankins of Oklahoma City, has said in court documents that Ochoa has become so irrational that he can no longer communicate with him.

Authorities never determined a motive for the slayings, which occurred while three children were in the home. Ochoa has maintained his innocence. Torres, a Mexican also convicted and sentenced to death, had his sentence commuted to life in prison without parole in 2004.

The ruling led the federal appeals court in Denver to order a new trial to determine Ochoa's mental competency at the time of the killings. A jury in 2005 decided he was not mentally retarded.

Oklahoma Coalition to Abolish Death Penalty

During the early morning hours of July 12, 1993, Francisco Morales and his wife, Maria Yanez, were shot and killed in the bedroom of their Oklahoma City home. The sound of gunfire woke Yanez's daughter Christina, who was 14 years old in the summer of 1993. Christina called 911 and told the operator that she believed her step-father, Morales, may have been firing the gun. After hanging up the telephone, she looked out her bedroom door. A light was on in the living room; Christina saw two men. One man was wearing a white t-shirt and the other man was wearing a black t-shirt. Christina stated the man in the black t-shirt had something in his hand, but she did not know what it was.

Christina initially denied knowing the two men, but eventually identified Ochoa as the man in the black t-shirt and Torres as the man in the white t-shirt. The shooting also awakened Christina's step-brother, Francisco, who was eleven years old in the summer of 1993. Francisco saw the man in the black t-shirt shoot his father. He could not identify the gunman.

The police quickly responded to Christina's 911 call. While en route to the Yanez/Morales home, Officer Coats arrested Torres and Ochoa, who were walking together a short distance from the homicide. The men were sweating and nervous, and Coats claimed he observed blood on the clothing of the men. A short time before the shootings, Torres and Ochoa parked their car at a friend's house. A witness observed one of the men take a gun from the trunk of the car and put the gun in his pants. This gun was different from the gun used in the murders. The witness stated one of the men was Ochoa. She could not identify the other man, but asserted that it was the other man-and not Ochoa-who put the gun in his pants.

Another witness testified that the man with Ochoa was Torres. The jury convicted Ochoa and Torres on all counts and the case proceeded to the capital sentencing phase of trial. The State argued that Ochoa and Torres posed a continuing threat to society based on the circumstances of the murders and the defendants' membership in the Southside Locos, a local gang. To show that Ochoa created a risk of death to more than one person, the State offered the death of the two victims and the presence of three children in the home at the time of the murders. The defense presented in mitigation Ochoa's personal history, his history of mental illness, his borderline mental retardation and pleas of mercy from his family. The jury found the existence of both aggravating circumstances. After weighing the aggravating and mitigating evidence, the jury imposed the death penalty.

Oklahoma Attorney General (News Release)

News Release

12/04/2012

George Ochoa - 6 p.m. Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester

Name: George Ochoa

DOB: 08/06/1974

Sex: Male

Age at Date of Crime: 18

Victim(s): Francisco Morales, 38 Maria Yanez, 35

Date of Crime: 07/12/1993

Date of Sentence: 03/21/1996

Crime Location: Victim’s home in Oklahoma City

Judge: Charles Owens

Prosecuting: Robert Macy and Susan P. Caswell

Defending: Kurt Geer and Bert Richard

Circumstances Surrounding Crime:

Ochoa was convicted and sentenced to death for the first-degree murders of Francisco Morales and Maria Yanez. The murders occurred in the early morning hours of July 12, 1993. Ochoa and an accomplice broke into the Morales home while the family was asleep. Ochoa immediately entered the bedroom where Morales and Yanez were sleeping and shot both victims. Morales and Yanez each suffered a minimum of nine gunshot wounds.

The victim’s three children were in the home at the time of the murders and were awakened by the sounds of gunshots. Yanez’s daughter initially denied knowing the two men, but eventually identified Ochoa as the man in her home wearing a dark shirt. Morales’s son, although unable to see a face, saw the man in the dark shirt, Ochoa, shoot his father. En route to the crime scene, police stopped Ochoa and his accomplice who were walking nearby. The men, who matched the description given by the victim’s children, appeared nervous and sweaty.

In October 1995, Ochoa was tried for two counts of murder and burglary in the first degree. During deliberations, the jury was unable to reach a verdict and the court declared a mistrial. In March 1996, Ochoa was retried and found guilty of all counts and sentenced to death for the two murder counts. Ochoa also was given 20 years for burglary.

Statement from Attorney General Scott Pruitt:

“George Ochoa was found guilty by a jury of his peers and given the death sentence for ending the lives of Francisco Morales and Maria Yanez,” Attorney General Scott Pruitt said. “My thoughts are with the family, especially Francisco and Maria’s children, for what they have endured for the past 19 years.”

Wikipedia: Oklahoma Executions

A total of 98 individuals convicted of murder have been executed by the State of Oklahoma since 1976, all by lethal injection:

1. Charles Troy Coleman 10 September 1990 John Seward

2. Robyn Leroy Parks 10 March 1992 Abdullah Ibrahim

3. Olan Randle Robinson 13 March 1992 Shiela Lovejoy, Robert Swinford

4. Thomas J. Grasso 20 March 1995 Hilda Johnson

5. Roger Dale Stafford 1 July 1995 Melvin Lorenz, Linda Lorenz, Richard Lorenz, Isaac Freeman, Louis Zacarias, Terri Horst, David Salsman, Anthony Tew, David Lindsey

6. Robert Allen Brecheen [1][2][3] 11 August 1995 Marie Stubbs

7. Benjamin Brewer 26 April 1996 Karen Joyce Stapleton

8. Steven Keith Hatch 9 August 1996 Richard Douglas, Marilyn Douglas

9. Scott Dawn Carpenter 7 May 1997 A.J. Kelley

10. Michael Edward Long 20 February 1998 Sheryl Graber, Andrew Graber

11. Stephen Edward Wood 5 August 1998 Robert B. Brigden

12. Tuan Anh Nguyen 10 December 1998 Amanda White, Joseph White

13. John Wayne Duvall 17 December 1998 Karla Duvall

14. John Walter Castro 7 January 1999 Beulah Grace, Sissons Cox, Rhonda Pappan

15. Sean Richard Sellers 4 February 1999 Paul Bellofatto, Vonda Bellofatto, Robert Bower

16. Scotty Lee Moore 3 June 1999 Alex Fernandez

17. Norman Lee Newsted 8 July 1999 Larry Buckley

18. Cornel Cooks 2 December 1999 Jennie Elva Ridling

19. Bobby Lynn Ross 9 December 1999 Steven Mahan

20. Malcolm Rent Johnson 6 January 2000 Ura Alma Thompson

21. Gary Alan Walker 13 January 2000 Eddie O. Cash, Valerie Shaw-Hartzell, Jane Hilburn, Janet Jewell, Margaret Bell Lydick, DeRonda Gay Roy

22. Michael Donald Roberts 10 February 2000 Lula Mae Brooks

23. Kelly Lamont Rogers 23 March 2000 Karen Marie Lauffenburger

24. Ronald Keith Boyd 27 April 2000 Richard Oldham Riggs

25. Charles Adrian Foster 25 May 2000 Claude Wiley

26. James Glenn Rodebeaux 1 June 2000 Nancy Rose Lee McKinney

27. Roger James Berget 8 June 2000 Rick Lee Patterson

28. William Clifford Bryson 15 June 2000 James Earl Plantz

29. Gregg Francis Braun 10 August 2000 Gwendolyn Sue Miller, Barbara Kchendorfer, Mary Rains, Pete Spurrier, Geraldine Valdez

30. George Kent Wallace 10 August 2000 William Von Eric Domer, Mark Anthony McLaughlin

31. Eddie Leroy Trice 9 January 2001 Ernestine Jones

32. Wanda Jean Allen 11 January 2001 Gloria Jean Leathers

33. Floyd Allen Medlock 16 January 2001 Katherine Ann Busch

34. Dion Athansius Smallwood 18 January 2001 Lois Frederick

35. Mark Andrew Fowler 23 January 2001 John Barrier, Rick Cast, Chumpon Chaowasin

36. Billy Ray Fox 25 January 2001

37. Loyd Winford Lafevers 30 January 2001 Addie Mae Hawley

38. Dorsie Leslie Jones, Jr. 1 February 2001 Stanley Eugene Buck, Sr.

39. Robert William Clayton 1 March 2001 Rhonda Kay Timmons

40. Ronald Dunaway Fluke 27 March 2001 Ginger Lou Fluke, Kathryn Lee Fluke, Suzanna Michelle Fluke

41. Marilyn Kay Plantz 1 May 2001 James Earl Plantz

42. Terrance Anthony James 22 May 2001 Mark Allen Berry

43. Vincent Allen Johnson 29 May 2001 Shirley Mooneyham

44. Jerald Wayne Harjo 17 July 2001 Ruther Porter

45. Jack Dale Walker 28 August 2001 Shely Deann Ellison, Donald Gary Epperson

46. Alvie James Hale, Jr. 18 October 2001 William Jeffery Perry

47. Lois Nadean Smith 4 December 2001 Cindy Baillee

48. Sahib Lateef Al-Mosawi 6 December 2001 Inaam Al-Nashi, Mohamed Al-Nashi

49. David Wayne Woodruff 21 January 2002 Roger Joel Sarfaty, Lloyd Thompson

50. John Joseph Romano 29 January 2002

51. Randall Eugene Cannon 23 July 2002 Addie Mae Hawley

52. Earl Alexander Frederick, Sr. 30 July 2002 Bradford Lee Beck

53. Jerry Lynn McCracken[10] 10 December 2002 Tyrrell Lee Boyd, Steve Allen Smith, Timothy Edward Sheets, Carol Ann McDaniels

54. Jay Wesley Neill 12 December 2002 Kay Bruno, Jerri Bowles, Joyce Mullenix, Ralph Zeller

55. Ernest Marvin Carter, Jr. 17 December 2002 Eugene Mankowski

56. Daniel Juan Revilla 16 January 2003 Mark Gomez Brad Henry

57. Bobby Joe Fields 13 February 2003 Louise J. Schem

58. Walanzo Deon Robinson 18 March 2003 Dennis Eugene Hill

59. John Michael Hooker 25 March 2003 Sylvia Stokes, Durcilla Morgan

60. Scott Allen Hain 3 April 2003 Michael William Houghton, Laura Lee Sanders

61. Don Wilson Hawkins, Jr. 8 April 2003 Linda Ann Thompson

62. Larry Kenneth Jackson 17 April 2003 Wendy Cade

63. Robert Wesley Knighton 27 May 2003 Richard Denney, Virginia Denney

64. Kenneth Chad Charm 5 June 2003 Brandy Crystian Hill

65. Lewis Eugene Gilbert II 1 July 2003 Roxanne Lynn Ruddell

66. Robert Don Duckett 8 July 2003 John E. Howard

67. Bryan Anthony Toles 22 July 2003 Juan Franceschi, Lonnie Franceschi

68. Jackie Lee Willingham 24 July 2003 Jayne Ellen Van Wey

69. Harold Loyd McElmurry III 29 July 2003 Rosa Vivien Pendley, Robert Pendley

70. Tyrone Peter Darks 13 January 2004 Sherry Goodlow

71. Norman Richard Cleary 17 February 2004 Wanda Neafus

72. David Jay Brown 9 March 2004 Eldon Lee McGuire

73. Hung Thanh Le 23 March 2004 Hai Hong Nguyen

74. Robert Leroy Bryan 8 June 2004 Mildred Inabell Bryan

75. Windel Ray Workman 26 August 2004 Amanda Hollman

76. Jimmie Ray Slaughter 15 March 2005 Melody Sue Wuertz, Jessica Rae Wuertz

77. George James Miller, Jr. 12 May 2005 Gary Kent Dodd

78. Michael Lannier Pennington 19 July 2005 Bradley Thomas Grooms

79. Kenneth Eugene Turrentine 11 August 2005 Avon Stevenson, Anita Richardson, Tina Pennington, Martise Richardson

80. Richard Alford Thornburg, Jr. 18 April 2006 Jim Poteet, Terry Shepard, Kevin Smith

81. John Albert Boltz 1 June 2006 Doug Kirby

82. Eric Allen Patton 29 August 2006 Charlene Kauer

83. James Patrick Malicoat 31 August 2006 Tessa Leadford

84. Corey Duane Hamilton 9 January 2007 Joseph Gooch, Theodore Kindley, Senaida Lara, Steven Williams

85. Jimmy Dale Bland 26 June 2007 Doyle Windle Rains

86. Frank Duane Welch 21 August 2007 Jo Talley Cooper, Debra Anne Stevens

87. Terry Lyn Short[4] 17 June 2008 Ken Yamamoto

88. Jessie Cummings 25 September 2008 Melissa Moody

89. Darwin Brown 22 January 2009 Richard Yost

90. Donald Gilson 14 May 2009 Shane Coffman

91. Michael DeLozier 9 July 2009 Orville Lewis Bullard, Paul Steven Morgan

92. Julius Ricardo Young 14 January 2010 Joyland Morgan, Kewan Morgan

93. Donald Ray Wackerly II 14 October 2010 Pan Sayakhoummane

94. John David Duty 16 December 2010 Curtis Wise

95. Billy Don Alverson 6 January 2011 Richard Kevin Yost

96. Jeffrey David Matthews 11 January 2011 Otis Earl Short Mary Fallin

97. Gary Welch 5 January 2012 Robert Dean Hardcastle

98. Timothy Shaun Stemple 15 March 2012 Trisha Stemple

99. Michael Bascum Selsor 1 May 2012 Clayton Chandler

100. Michael E. Hooper 14 August 2012 Cynthia Jarman, Timothy Jarman, Tonya Jarman

101. Garry T. Allen 06 November 2012 Gail Titsworth

102. George Ochoa 04 December 2012 Francisco Morales, Maria Yanez

Ochoa v. State, 963 P.2d 583 (Okla.Crim. App. 1998). (Direct Appeal)

Defendant was convicted in the District Court, Oklahoma County, Charles L. Owens, J., of two counts of first-degree murder with malice aforethought and one count of first-degree burglary, and was sentenced to death. Defendant appealed, and the Court of Criminal Appeals, Chapel, P.J., held that: (1) evidence supported determination that defendant was competent to stand trial; (2) defendant validly waived jury trial on competency; (3) defendant and accomplice were properly required to share peremptory challenges; (4) challenge for cause to juror who was former deputy sheriff was properly denied; (5) limitations on investigation of crime scene by defendant, while improper, did not warrant relief; (6) State's destruction of fingerprints was not in bad faith; (7) denial of continuance was not an abuse of discretion; (8) severance of trials was not required, as defendant and accomplice did not have mutually antagonistic defenses; (9) admission of photographs of victims was within trial court's discretion; (10) evidence supported convictions; (11) improper comments by prosecutor did not create plain error; (12) evidence was insufficient to establish continuing threat aggravating circumstance; but (13) offenses established aggravator of great risk of death to more than one person, and warranted death sentence. Affirmed. Strubhar, V.P.J., concurred in the result and filed opinion. Lumpkin, J., concurred in the result and filed opinion. Lane, J., concurred in the result.

CHAPEL, Presiding Judge.

¶ 1 George Ochoa was tried jointly with Osbaldo Torres by a jury in Oklahoma County District Court, Case No. CF–93–4302. Ochoa was convicted of two counts of First Degree Murder with Malice Aforethought, in violation of 21 O.S.1991, § 701.7(A) and one count of First Degree Burglary, in violation of 21 O.S.1991, § 1431.FN1 At the conclusion of the capital sentencing phase of the trial, the jury found the existence of two aggravating circumstances: (1) there existed the probability that Ochoa would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society,FN2 and (2) Ochoa knowingly created a great risk of death to more than one person.FN3 The jury recommended Ochoa be sentenced to death for both murders and to twenty (20) years imprisonment for burglary.FN4 The Honorable Charles L. Owens sentenced Ochoa accordingly. Ochoa appealed his conviction and sentence to this Court.FN5

FN1. Torres was also convicted of two counts of first degree malice murder and burglary. See Torres v. State, 1998 OK CR 40. FN2. 21 O.S.1991, § 701.12(7). FN3. 21 O.S.1991, § 701.12(2). FN4. Torres was also sentenced to death for both murders and to twenty (20) years imprisonment for burglary. FN5. Ochoa also filed a motion for a new trial, request to supplement the record and a request for an evidentiary hearing. Since this motion was not filed timely, it is denied. 22 O.S.1991, § 953, Rule 2.1, Rules of the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals, Title 22, Ch. 18, App.

Facts

¶ 2 During the early morning hours of July 12, 1993, Francisco Morales and his wife, Maria Yanez, were shot and killed in the bedroom of their Oklahoma City home. The sound of gunfire woke Yanez's daughter Christina, who was 14 years old in the summer of 1993. Christina called 911 and told the operator that she believed her step-father, Morales, may have been firing the gun. After hanging up the telephone, she looked out her bedroom door. A light was on in the living room; Christina saw two men. One man was wearing a white t-shirt and the other man was wearing a black t-shirt. Christina stated the man in the black t-shirt had something in his hand, but she did not know what it was. Christina initially denied knowing the two men, but eventually identified Ochoa as the man in the black t-shirt and Torres as the man in the white t-shirt.

¶ 3 The shooting also awakened Christina's step-brother, Francisco, who was eleven years old in the summer of 1993. Francisco saw the man in the black t-shirt shoot his father. He could not identify the gunman.

¶ 4 The police quickly responded to Christina's 911 call. While en route to the Yanez/Morales home, Officer Coats arrested Torres and Ochoa, who were walking together a short distance from the homicide. The men were sweating and nervous, and Coats claimed he observed blood on the clothing of the men.

¶ 5 A short time before the shootings, Torres and Ochoa parked their car at a friend's house. A witness observed one of the men take a gun from the trunk of the car and put the gun in his pants. This gun was different from the gun used in the murders. The witness stated one of the men was Ochoa. She could not identify the other man, but asserted that it was the other man—and not Ochoa—who put the gun in his pants. Another witness testified that the man with Ochoa was Torres.

¶ 6 The jury convicted Ochoa and Torres on all counts and the case proceeded to the capital sentencing phase of trial. The State argued that Ochoa and Torres posed a continuing threat to society based on the circumstances of the murders and the defendants' membership in the Southside Locos, a local gang. To show that Ochoa created a risk of death to more than one person, the State offered the death of the two victims and the presence of three children in the home at the time of the murders. The defense presented in mitigation Ochoa's personal history, his history of mental illness, his borderline mental retardation and pleas of mercy from his family. The jury found the existence of both aggravating circumstances. After weighing the aggravating and mitigating evidence, the jury imposed the death penalty.

Competence to Stand Trial

¶ 7 The first issue Ochoa raises on appeal is whether he was competent to stand trial in 1996. Ochoa argues his case should be reversed because the determination that he was competent to stand trial was made under the old “clear and convincing evidence” standard, which the Supreme Court ruled infirm in Cooper v. Oklahoma.FN6 The State contends that if the Court finds error, the case should not be reversed but remanded for a retrospective competency hearing. Although the question of Ochoa's competency was decided under the infirm “clear and convincing evidence” standard, the case need not be reversed nor remanded for a retrospective competency hearing.

FN6. 517 U.S. 348 116 S.Ct. 1373, 134 L.Ed.2d 498 (1996). In Cooper, the Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional Oklahoma's standard for determining whether a defendant is competent to stand trial. The statute, 22 O.S.1991, § 1175.4(B), provided that a defendant in a criminal prosecution is presumed competent to stand trial unless he proves his incompetence by clear and convincing evidence. The Supreme Court ruled that the “clear and convincing evidence” standard placed too high a burden of proof on the defendant and struck down this standard of proof. In response to Cooper, this Court determined the new burden of proof to be applied in competency determinations is preponderance of the evidence. Cooper v. State, 924 P.2d 751, 752 (Okl.Cr.1996). See 22 O.S.Supp.1996 § 1175.4(B) (“The court, at the hearing on the application, shall determine, by a preponderance of the evidence, if the person is incompetent.”)

¶ 8 Ochoa waived jury trial on the issue of competency. When a defendant waives a jury competency trial and the hearing is held before the trial court, this Court will review de novo the question of whether the record supports a finding that the defendant is competent to stand trial under the new “preponderance of the evidence” standard.FN7 A defendant's competency to stand trial is defined as “the present ability of a person arrested for or charged with a crime to understand the nature of the charges and proceedings brought against him and to effectively and rationally assist in his defense.” FN8 As a corollary, Oklahoma statutes define incompetency as “the present inability of a person arrested for or charged with a crime to understand the nature of the charges and proceedings brought against him and to effectively and rationally assist in his defense.” FN9

FN7. See Smith v. State, 932 P.2d 521, 528 (Okl.Cr.1996), cert. denied, 521 U.S. 1124, 117 S.Ct. 2522, 138 L.Ed.2d 1023 (1997). FN8. 22 O.S.Supp.1992, § 1175.1 (emphasis added). See Dusky v. United States, 362 U.S. 402, 402, 80 S.Ct. 788, 789, 4 L.Ed.2d 824 (1960); Miller v. State, 751 P.2d 733, 736–37 (Okl.Cr.1988). FN9. 22 O.S.Supp.1992, § 1175.1.

¶ 9 Here, in a proceeding before the trial court, Ochoa, through counsel, stipulated to Dr. Warren Smith's report in which Dr. Smith found (1) Ochoa appreciated the nature of the charges against him although “he cannot remember the event for which he is alleged responsible,” FN10 and (2) Ochoa could consult with his lawyer and rationally assist in his defense. Ochoa offered no other evidence. Based on Dr. Smith's report, the court found Ochoa “able to appreciate the charges against him,” FN11 and “able to consult with his lawyer and rationally assist in the preparation of his defense.” FN12 The court ordered the proceedings to resume.

FN10. May 31, 1995 Tr. at State's Ex. 1. FN11. Id. FN12. Id.

¶ 10 This evidence supports the finding that Ochoa was competent to stand trial under the “preponderance of the evidence” standard. Dr. Smith's report is the only evidence in the record. There is nothing in the report to suggest that Ochoa would be incompetent under the lower burden of proof. On appeal, Ochoa argues that Dr. Murphy, who testified on Ochoa's behalf during sentencing, would have provided testimony that Ochoa was not competent to stand trial under the now-lower burden of proof. A review of Murphy's testimony does not support this claim. Based on the record below, we find that Ochoa was competent to stand trial and defense counsel failed to show, based on a preponderance of evidence, that he was incompetent.

¶ 11 Ochoa also argues that trial counsel was ineffective for failing to challenge the competency determination.FN13 Because we find, based on a de novo review of the record, that Ochoa would have been deemed competent to stand trial under a preponderance of the evidence standard, Ochoa was not prejudiced by trial counsel's actions. Counsel was not ineffective. FN13. Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 104 S.Ct. 2052, 80 L.Ed.2d 674 (1984).

¶ 12 In his reply brief, Ochoa also argues that when a defendant waives a jury trial on competency the Court should impose a waiver standard similar to the one imposed in Brewer v. State,FN14 which dealt with the procedure to be followed when a defendant stipulates to an aggravating circumstance. This Court already recognizes that the post-examination competency jury trial may be affirmatively waived FN15 and the Brewer standard is not appropriate here. Moreover, the record shows that Ochoa knowingly, intelligently and affirmatively waived jury trial on the issue of competency. Indeed, the trial court explained to Ochoa several times what a jury trial on competency would entail and advised Ochoa that it would hold the jury trial if Ochoa wished. Ochoa stated he understood his rights, he understood what a competency jury trial was, and he wished to proceed to trial. Ochoa's attorney also stated that Ochoa understood the function of the jury trial, that Ochoa wanted to stipulate to the competency report, which is discussed above, and that Ochoa wished to proceed to trial on the merits. This exchange and waiver are adequate.FN16 Error did not occur and relief is not warranted.

FN14. 650 P.2d 54, 63 (Okl.Cr.1982), cert. denied, 459 U.S. 1150, 103 S.Ct. 794, 74 L.Ed.2d 999 (1983). FN15. Lillard v. State, 852 P.2d 756, 757 (Okl.Cr.1993) (citing Kiser v. State, 782 P.2d 405, 408–09 (Okl.Cr.1989)). FN16. Kiser v. State, 782 P.2d 405, 408 (Okl.Cr.1989) (defendant affirmatively waived post-examination competency hearing by a jury when he withdrew motion for hearing and requested case proceed to preliminary hearing).

Jury Selection

¶ 13 In his sixth proposition of error, Ochoa complains that procedural and substantive error occurred during the jury selection process depriving him of his right to a constitutionally impaneled jury. In making this claim, Ochoa presents three arguments.

¶ 14 First, Ochoa claims error occurred when the trial court required him and Torres to share their nine peremptory challenges and denied defense requests that each defendant be allotted nine separate challenges. Section 655 of Title 22 provides, in pertinent part: “if two or more defendants are tried jointly they shall join in their challenges; provided, that when two or more defendants have inconsistent defenses they shall be granted separate challenges for each defendant as hereinafter set forth.” Consistent with this statute, this Court has stated “when the defenses of codefendants are inconsistent, they should not be required to share peremptory challenges.” FN17 The Court has put some parameters on “inconsistent defenses.” In Neill v. State, the Court stated “in some cases, the ‘inconsistency’ goes to the level of culpability while in other cases the ‘inconsistency’ goes to guilt or innocence. Where the issue is restricted to the level of each co-defendant's culpability, co-defendants may be required to share peremptory challenges.” FN18

FN17. Woodruff v. State, 825 P.2d 273, 276 (Okl.Cr.1992). See Neill v. State, 827 P.2d 884, 891 (Okl.Cr.1992) (“[c]o-defendants tried jointly who have inconsistent defenses shall be granted separate peremptory challenges”). The Constitution does not require that defendants tried together be granted separate peremptory challenges. Stilson v. United States, 250 U.S. 583, 586, 40 S.Ct. 28, 30, 63 L.Ed. 1154 (1919). FN18. 827 P.2d at 891 (citing Fox v. State, 779 P.2d 562, 568 (Okl.Cr.1989); Fowler v. State, 779 P.2d 580, 582 (Okl.Cr.1989), cert. denied, 494 U.S. 1060, 110 S.Ct. 1537, 108 L.Ed.2d 775 (1990)).

¶ 15 Ochoa and Torres did not have inconsistent defenses. The defense of both men was that they did not kill Yanez and Morales. Since Ochoa and Torres' defenses were not inconsistent, the court did not err in denying the request for separate peremptory challenges.

¶ 16 Second, Ochoa claims that the trial court erred in failing to sua sponte dismiss Juror Harris for cause. Juror Harris told the court and counsel that he had served as a deputy sheriff in Kern County, California for seventeen and a half years, but that he was now retired. Harris also stated he could be fair. Neither Ochoa nor Torres moved to strike Harris for cause. Eventually Ochoa used a peremptory challenge to remove Harris; Torres objected to the removal.

¶ 17 At issue here is the provision in 38 O.S.1991, § 28, which states that “[s]heriffs or deputy sheriffs” are not qualified to serve on a jury. However, since Juror Harris was a retired, as opposed to active, deputy sheriff he does not fall under the statutory disqualification. FN19 Moreover, Juror Harris made clear he could be impartial and he would properly consider the death penalty. The court did not err in failing to sua sponte strike Harris for cause. FN19. Nickell v. State, 885 P.2d 670, 676 (Okl.Cr.1994) (former FBI agent who knew district attorney was not disqualified from jury service under 38 O.S.1991, § 28); Coats v. State, 56 Okl.Cr. 26, 33, 32 P.2d 955, 958 (1934) (former deputy sheriffs not disqualified from jury service).

¶ 18 Finally, Ochoa complains the court erred when it overruled certain motions regarding voir dire. Ochoa complains the trial court erred in denying a motion for individual voir dire. This Court has repeatedly stated individual voir dire is not required and the decision to allow individual voir dire is left to the sound discretion of the trial court. FN20 The trial court did not abuse its discretion. Ochoa further maintains that the court erred in denying a motion that it ask certain death-qualifying questions and a motion challenging the death-qualifying nature of voir dire. Although the trial court refused to ask certain questions requested by the defense, the questions the trial court posed to the jury comported with Witherspoon v. Illinois FN21 and Morgan v. Illinois. FN22 The trial court did not commit error in its questioning of the jury. Moreover, trial counsel was not inhibited in his questioning of jurors on the death penalty. Ochoa has failed to show prejudice under this proposition and relief is denied.

FN20. Malone v. State, 876 P.2d 707, 711 (Okl.Cr.1994) (“decision to allow individual voir dire of potential jurors is also committed to the sound discretion of the trial court and is not a right guaranteed a defendant”). FN21. 391 U.S. 510, 88 S.Ct. 1770, 20 L.Ed.2d 776 (1968). FN22. 504 U.S. 719, 112 S.Ct. 2222, 119 L.Ed.2d 492 (1992).

First Stage of Trial

¶ 19 Ochoa raises a number of propositions of error concerning the first stage of trial. In the second proposition of his brief, Ochoa argues he was denied due process because the prosecution denied his investigators independent access to the crime scene. For the reasons stated below, we deny this proposition.

¶ 20 Ochoa and Torres were originally tried in October 1995, but the case ended in mistrial. Before the second trial, Ochoa moved the trial court to order the person now living in the victims' house to allow defense investigators into their home to investigate the crime scene. Apparently the person who was living in the Yanez/Morales home refused to allow defense investigators into the house. The trial court stated it was without authority to order a third party to allow defense investigators into the home and overruled the motion. FN23. Ochoa does not challenge this ruling.

¶ 21 Shortly before the second trial, Ochoa learned that the prosecution intended to re-investigate the crime scene. The assistant district attorney agreed to permit defense investigators to accompany the State's investigators on their re-examination of the crime scene. Defense counsel sent a letter to the assistant district attorney confirming that his investigators would accompany the State investigators to the crime scene. In a handwritten note at the bottom of the letter, the assistant district attorney wrote: It is agreed that neither [defense investigators] will not take photographs or measurements of the interior of the home or interfere w/ the technical investigator. FN24. Vol. III O.R. at 521. According to defense counsel, the addendum was a last minute addition and was not part of the original deal. Defense counsel stated that nonetheless they thought it better to go to the house with that condition than not to go at all. Defense investigators accompanied the police and observed the measurements and the investigation taken by the officers. Defense investigators were not allowed an independent investigation and were not allowed to confirm the correctness of the police measurements. As a result of the new investigation, the prosecution produced a new diagram of the interior of the house that differed in certain respects from the diagram offered at the first trial. The trial court found the differences were minor.

¶ 22 On appeal, Ochoa argues that denying his investigators the ability to take independent measurements deprived him of due process. In making this argument, Ochoa relies on Brady v. Maryland FN25 and other cases addressing the State's withholding of exculpatory evidence. These cases are not on point because the State did not withhold exculpatory evidence from Ochoa. Similarly, Ochoa's analogy to cases dealing with the State's presentation of false evidence FN26 are not on point because there is no reason to believe the State presented false evidence. More apropos is Ochoa's argument that the State's restrictions precluded him from putting on his defense thus depriving him of due process and a fair trial. In support of this argument, Ochoa cites several out-of-state cases. Although these cases are not binding on this Court, the cases indicate how other courts have treated similar problems.

FN25. 373 U.S. 83, 83 S.Ct. 1194, 10 L.Ed.2d 215 (1963). See also Kyles v. Whitley 514 U.S. 419, 115 S.Ct. 1555, 131 L.Ed.2d 490 (1995); State v. Munson, 886 P.2d 999 (Okl.Cr.1994). FN26. United States v. Young, 17 F.3d 1201 (9th Cir.1994).

¶ 23 In People v. Davis,FN27 a New York trial court granted a motion to allow the defendant access to the crime scene and harshly criticized the district attorney for trying to limit the defendant access to the scene. The court stated (1) the district attorney had no possessory interest in the property, (2) the district attorney had no statutory authority to limit defendant's access to the scene, and (3) any effort by the district attorney to do so was improper. In Henshaw v. Commonwealth of Virginia,FN28 the defendant wished access to a crime scene which was in the possession of a third party. The court found that denial of access to the crime scene may deprive the defendant of due process and fundamental fairness. Relying on the state constitution, the court found that although the trial court should have ordered access to the crime scene, the error was harmless.FN29

FN27. 169 Misc.2d 977, 647 N.Y.S.2d 392 (N.Y.Co.Ct.1996). FN28. 19 Va.App. 338, 451 S.E.2d 415 (1994). FN29. Ochoa also cites State v. Davenport, 696 So.2d 999 (La.1997), which is simply a one sentence order and we cannot determine how or why the court issued that particular order.

¶ 24 Here, the restrictions the State placed on Ochoa's investigators are petty, unjustified and improper. The State contended that the restrictions were necessary to prevent interference with the State's investigation, but this argument is spurious. We are dismayed that the State would place such unnecessary and inappropriate barriers in front of a defendant's legitimate and proper attempt to prepare his defense. Nonetheless, Ochoa has failed to show that these restrictions curtailed his defense or deprived him of his right to due process. Although Ochoa claims that the two diagrams—the one used in the first trial and the one used in this trial—differ significantly from one another, he has not shown what these significant differences are or how they affected his defense. In contrast, the trial court noted that the differences were only slight. Accordingly, we find the State's improper action did not harm Ochoa and neither reversal nor modification of sentence is an appropriate remedy.

¶ 25 Ochoa also argues, under this proposition of error, that relief ought to be granted because the State destroyed latent fingerprints that were unusable but which might have contained sufficient ridge information to be of exculpatory value. In Arizona v. Youngblood,FN30 the Supreme Court held “unless a criminal defendant can show bad faith on the part of the police, failure to preserve potentially useful evidence does not constitute a denial of due process of law.” FN31 This Court adopted the Youngblood standard in Hogan v. State.FN32 Ochoa has not shown that the State acted in bad faith when it destroyed the latent prints, and relief is not warranted.

FN30. 488 U.S. 51, 58, 109 S.Ct. 333, 337, 102 L.Ed.2d 281 (1988). FN31. Id. FN32. 877 P.2d 1157, 1161 (Okl.Cr.1994), cert. denied, 513 U.S. 1174, 115 S.Ct. 1154, 130 L.Ed.2d 1111 (1995).

¶ 26 Ochoa raises a related complaint in Proposition VIII arguing that the trial court should have instructed the jury that they could draw a negative inference from Officer Goforth's destruction of fingerprint evidence. We disagree. Due process does not impose “an undifferentiated and absolute duty to retain and to preserve all material that might be of conceivable evidentiary significance in a particular prosecution.” FN33 As stated earlier, unless a defendant can show bad faith by the police, destruction of potentially useful evidence does not constitute a due process violation. Ochoa cites two out-of-state cases that impose a higher standard on police, but this case is controlled by Hogan v. State and Arizona v. Youngblood. We find, in the absence of a showing of bad faith, the failure of the trial court to provide an instruction allowing the jury to draw a negative inference from the destruction of evidence does not violate Ochoa's right to due process. However, such an instruction may be an appropriate sanction where the defense has made a showing of bad faith. FN33. Youngblood, 488 U.S. at 58, 109 S.Ct. at 337.

¶ 27 In Proposition III, Ochoa relates that on the second day of trial, the prosecution revealed that the previous afternoon an informant in the Oklahoma County jail had advised an assistant district attorney that Torres had claimed to have shot and killed Yanez and Morales. Torres also allegedly claimed Ochoa was present at the shootings. This claim contradicted the State's theory that Ochoa shot the victims and Torres aided and abetted in their killing. Upon hearing this information, Ochoa's counsel withdrew their announcement of ready, requested a continuance to investigate and moved for a severance. The prosecutor stated he would not call the informant to testify. The trial court denied Ochoa's motions for a continuance and severance.

¶ 28 Ochoa asserts the trial court erred by failing to grant a continuance. This Court has stated “the decision whether to grant or deny a motion for continuance rests within the sound discretion of the trial court and will not be disturbed absent abuse of such discretion.” FN34 “When considering the overruling of a motion for a continuance, we will examine the entire record to ascertain whether or not the appellant suffered any prejudice by the denial.” FN35 Here, although the court denied the continuance, defense counsel had tried to speak with the informant while Ochoa's case was still in voir dire, but the informant refused to talk. There is nothing indicating that additional time would have changed his position. Ochoa has not shown he was prejudiced by the denial of the continuance. The court did not abuse its discretion.

FN34. Salazar v. State, 852 P.2d 729, 735 (Okl.Cr.1993). FN35. Bryson v. State, 876 P.2d 240, 254 (Okl.Cr.1994), cert. denied, 513 U.S. 1090, 115 S.Ct. 752, 130 L.Ed.2d 651 (1995).

¶ 29 Ochoa also argues his and Torres' trial ought to have been severed. Where two defendants have “mutually antagonistic defenses,” separate trials ought to be held and compelling joinder of trials may result in reversible error.FN36 Mutually antagonistic defenses occur when each defendant seeks to inculpate the other and exculpate himself.FN37 The Court has stated, “it is not enough that the defenses of the co-defendants are inconsistent, in conflict or are otherwise unreconcilable. To be considered ‘mutually antagonistic,’ the two theories of defense must be in direct contravention and the parties must each place blame with the co-defendant.” FN38 The Court has further stated “one defendant's attempt to cast blame on the other is not in itself a sufficient reason to require separate trials,” FN39 and “[m]ere conflicting defenses, standing alone, do not constitute the showing of prejudice necessary for judicial severance.” FN40

FN36. Cannon v. State, 827 P.2d 1339, 1341 (Okl.Cr.1992); Lafevers v. State, 819 P.2d 1362, 1364 (Okl.Cr.1991). FN37. Lafevers, 819 P.2d at 1365. FN38. Id. at 1365–66. FN39. Neill, 827 P.2d at 886. FN40. Id. at 886–87. See Zafiro v. United States, 506 U.S. 534, 538, 113 S.Ct. 933, 938, 122 L.Ed.2d 317 (1993) (“[m]utually antagonistic defenses are not prejudicial per se ”).

¶ 30 The defenses here were not mutually antagonistic. As stated earlier, the defense of both men was that they did not commit the crime and both men focused their attack on undermining the eye-witness testimony. Further, the State did not call the informant to testify.FN41 Thus, the defendants did not engage in any sort of finger-pointing or blame. The trial court did not err in refusing to sever the defendants' trials.FN42

FN41. See Plantz v. State, 876 P.2d 268, 273 (Okl.Cr.1994), cert. denied, 513 U.S. 1163, 115 S.Ct. 1130, 130 L.Ed.2d 1091 (1995) (finding severance not required where defendants did not present mutually antagonistic defenses and State did not introduce incriminating statement by non-testifying co-defendant). FN42. Neill, 827 P.2d at 886 (absent abuse of discretion, trial court's decision to try defendants jointly will not be disturbed on appeal).

¶ 31 In his fourth proposition of error, Ochoa, for the first time, challenges the admissibility of Christina Yanez's identification of him and Torres. Since Ochoa did not lodge a contemporaneous objection to the evidence, relief will only be granted upon a showing that plain error occurred as a result of the admission of this evidence.

¶ 32 Christina's identification of Ochoa and Torres was crucial to the State's case. Initially, she denied knowing the men who killed her parents. Christina admitted this initial denial explaining she made the initial denial because she was frightened. The initial denial does not render Christina's subsequent identification inadmissible; the evidence merely goes to the issue of credibility and reliability, which was a proper issue for the jury to decide. FN43. See Woodruff v. State, 846 P.2d 1124, 1134 (Okl.Cr.), cert. denied, 510 U.S. 934, 114 S.Ct. 349, 126 L.Ed.2d 313 (1993) (jury is exclusive judge of weight of evidence and credibility of witnesses). Cf. Snow v. State, 876 P.2d 291, 295 (Okl.Cr.1994), cert. denied, 513 U.S. 1179, 115 S.Ct. 1165, 130 L.Ed.2d 1120, '30 L.Ed.2d 1120 (1995) (noting cautionary instruction on eye-witness identification was not necessary and instructing jury that it was sole judge of witness credibility was proper).

¶ 33 Ochoa next contends that Christina's subsequent identification of the men was tainted because Christina saw the men in handcuffs at the crime scene. The record does not support this contention. There is no testimony that Christina ever saw the defendants prior to telling Officer Mullenix at the police station that Ochoa was one of the men she saw in her home that night. Ochoa points to testimony that, after their arrest, Ochoa and Torres were taken to the crime scene and held in handcuffs there for some time. It was possible for the Yanez/Morales neighbors to see the defendants under arrest. However, there was no evidence that Christina saw the defendants or even knew they were there, and defense counsel never questioned Christina about this matter. Moreover, Officer Brett Macy testified that neither Christina nor her step-brother Francisco came into contact with the defendants at the crime scene. Based on this record, Ochoa has failed to show that there was a show-up identification and we cannot say that under the totality of the circumstances Christina's identification was tainted and/or unreliable.FN44 Accordingly, admission of her testimony and identification was proper. FN44. See Neil v. Biggers, 409 U.S. 188, 93 S.Ct. 375, 34 L.Ed.2d 401 (1972); Tibbetts v. State, 778 P.2d 925, 928–29 (Okl.Cr.1989).

¶ 34 Ochoa also alleges it was error for Detective Mullenix to testify that Christina identified Ochoa at the police station. Again Ochoa failed to lodge a contemporaneous objection and we review for plain error. This Court has stated “a witness, after making an in-court identification of the defendant, may testify that ‘at a particular day, place, and time or times, [he or she] had occasion to see, recognize and identify the defendant as the person who committed the crime.’ ” FN45 However, “[o]nly the identifier may testify that an identification was made.... Testimony by a third party that an identification was made, or that a particular person was identified is ... error.” FN46 Nonetheless, “[w]hen such testimony follows an in-court identification of the accused by the identifier the error has been found to be harmless.” FN47 Here, it was error for Mullenix to testify that Christina told him that one of the intruders was Ochoa. Nonetheless, the testimony was merely cumulative of Christina's testimony. The error is not prejudicial and relief is not warranted.

FN45. Scales v. State, 737 P.2d 950, 952 (Okl.Cr.1987) (quoting Hill v. State, 500 P.2d 1075, 1078 (Okl.Cr.1972)). FN46. Kamees v. State, 815 P.2d 1204, 1207 (Okl.Cr.1991) (citation omitted). FN47. Id. at 1207–08. See Trim v. State, 808 P.2d 697, 699 (Okl.Cr.1991).

¶ 35 Ochoa claims in his fifth proposition of error that his arrest is invalid because Officer Coats lacked probable cause to execute his warrantless arrest of Ochoa and Torres. This Court has stated, “The test for a valid warrantless arrest is whether at the moment the arrest was made the officer had probable cause to make it—whether at that moment the facts and circumstances within his knowledge and of which he had reasonably trustworthy information were sufficient to warrant a prudent man in believing that the defendant had committed or was committing an offense.” FN48 Ochoa asserts that Officer Coats did not have a description of the defendants until after he arrested the men. However, a fair reading of the record below supports the trial court's conclusion that Officer Coats heard the description of the defendants over the radio prior to arresting them. Further, Coats testified the men were perspiring and there was blood on Torres' clothes. These factors support the trial court's conclusion that there was probable cause to arrest. This proposition is denied. FN48. Castellano v. State, 585 P.2d 361, 365–66 (Okl.Cr.1978). See 22 O.S.1991, § 196 (“A peace officer may, without a warrant, arrest a person ... [w]hen a felony has in fact been committed, and he has reasonable cause for believing the person arrested to have committed it”).

¶ 36 Ochoa makes several complaints about alleged evidentiary errors in his seventh proposition of error. First, Ochoa complains the prosecution sought to introduce evidence of Ochoa's gang affiliation during the first stage of trial. Although the trial court ruled that such evidence was inadmissible during first stage, the prosecution elicited from Officer Tays that the suspects—Ochoa and Torres—might be gang members. There was no objection to this testimony.FN49 On four occasions during closing argument, the prosecution referred to the defendants, either directly or indirectly, as gang members. Defense objected to two of the comments on the grounds that the statement was not in evidence; FN50 the objections were overruled. We review these claims for plain error and we are troubled that the prosecution attempted to deliberately inject gang evidence into the first stage of trial. Not only did the evidence and comments regarding Ochoa's gang membership violate the trial court's order, but also such evidence was irrelevant to the question of guilt or innocence as the gang evidence was in no way connected to the Yanez/Morales' murders. While we find the use of gang evidence in the first stage of trial to be error, Ochoa has failed to show that the error was sufficiently prejudicial. Accordingly, relief is denied.

FN49. A defendant waives error when he fails to lodge a contemporaneous objection at trial. Hooker v. State, 887 P.2d 1351, 1365 (Okl.Cr.1994), cert. denied, 516 U.S. 858, 116 S.Ct. 164, 133 L.Ed.2d 106 (1995). FN50. An objection is waived if the grounds for the objection were different at trial than on appeal. Valdez v. State, 900 P.2d 363, 380 (Okl.Cr.), cert. denied, 516 U.S. 967, 116 S.Ct. 425, 133 L.Ed.2d 341 (1995); Mitchell v. State, 884 P.2d 1186, 1197 (Okl.Cr.1994), cert. denied, 516 U.S. 827, 116 S.Ct. 95, 133 L.Ed.2d 50 (1995).

¶ 37 Ochoa next complains that, over objection, Officer Robertson was allowed to testify about the inconclusive results of an FBI gun powder residue examination. This testimony was hearsay FN51 and should not have been allowed. However, we find the error harmless and deny relief. FN51. The State does not argue that the evidence is not hearsay. Rather, citing Simpson v. State, 876 P.2d 690 (Okl.Cr.1994), the State contends that relief is not warranted under the plain error standard. Simpson is not the correct standard to review this error because defense objected to the testimony on the grounds of hearsay.

¶ 38 Third, Ochoa contends the State failed to make an adequate showing that Garcia was unavailable to testify in person. We disagree. At trial, the prosecution advised the trial court that they could not locate Francisco Garcia and wished to introduce his testimony from the first trial in lieu of live testimony. “This Court has long held that the State must satisfy two threshold requirements before prior testimony may be admitted into evidence. The prosecution must prove, ‘(1) [t]he actual unavailability of the witness despite good faith and due diligent efforts to secure the presence of the witness at trial; and, (2) the transcript of the witness' testimony bears a sufficient indicia of reliability to afford the trier of fact a satisfactory basis for evaluating the truth of the prior testimony.’ ” FN52 Ochoa contends that the State failed to satisfy the first prong of this test because it did not exercise due diligence in locating Garcia. To the contrary, the State adequately attempted to locate Garcia and the trial court properly ruled that the State exercised due diligence. Admission of Garcia's previous testimony was not error. FN52. McCarty v. State, 904 P.2d 110, 128 (Okl.Cr.1995) (quoting Smith v. State, 546 P.2d 267, 271 (Okl.Cr.1976)).

¶ 39 Fourth, Ochoa asserts that Officer Mullenix injected an evidentiary harpoon into the trial. This Court has defined evidentiary harpoons as follows: “(1) they are generally made by experienced police officers; (2) they are voluntary statements; (3) they are willfully jabbed rather than inadvertent; (4) they inject information indicating other crimes; (5) they are calculated to prejudice the defendant; and (6) they are prejudicial to the rights of the defendant on trial.” FN53 Officer Mullenix's testimony was not an evidentiary harpoon. Mullenix's comment was a legitimate response to counsel's cross-examination questions. Moreover, Mullenix did not introduce information of other crimes; he simply indicated that he did not pursue another suspect in this case because he believed the police had arrested the right men. The officer's testimony is not an evidentiary harpoon and we decline to grant relief. FN53. Bruner v. State, 612 P.2d 1375, 1378–79 (Okl.Cr.1980).

¶ 40 Next, Ochoa objects to a number of photographs admitted at trial including Exhibits 105–09 and 111–123, which were crime scene photographs of both victims, and Exhibit 62, which included photographs found in the victim's purse. At trial, Ochoa only objected to Exhibits 106 and 107. His objections were overruled.

¶ 41 The decision to admit photographs rests within the sound discretion of the trial court.FN54 “The test for admissibility of a photograph is not whether it is gruesome or inflammatory, but whether its probative value is substantially outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice.” FN55 Moreover, “[t]he probative value of photographs of murder victims can be manifested in numerous ways, including showing the nature, extent and location of wounds, establishing the corpus delicti, depicting the crime scene, and corroborating the medical examiner's testimony.” FN56

FN54. McCormick v. State, 845 P.2d 896, 898 (Okl.Cr.1993). FN55. Hooks v. State, 862 P.2d 1273, 1280 (Okl.Cr.1993), cert. denied, 511 U.S. 1100, 114 S.Ct. 1870, 128 L.Ed.2d 490 (1994). FN56. Trice v. State, 853 P.2d 203, 212–13 (Okl.Cr.), cert. denied, 510 U.S. 1025, 114 S.Ct. 638, 126 L.Ed.2d 597 (1993).

¶ 42 In this case, although the State introduced eighteen pictures of the victims' bodies at trial, Ochoa only objected to two of the photographs. These two photographs were no more gruesome than the other sixteen. Moreover, exhibits 105–09 and 111–123 were probative of the nature and extent of the wounds, corroborated the medical examiner's testimony, depicted the crime scene and established the corpus delicti. The trial court did not err in admitting these photographs.

¶ 43 Ochoa also complains about Exhibit 62, which was the victim's purse and contents thereof, including photographs of the victims before their deaths. Generally, photographs of victims before their deaths are not probative FN57 and, in this case, the photographs should not have been admitted. However, Ochoa did not object to the evidence and he has failed to show plain error occurred in either stage of trial. FN57. Peninger v. State, 811 P.2d 609, 611 (Okl.Cr.1991) (admission of photograph of victim before death not proper).

¶ 44 Finally, Ochoa argues that, as a whole, the errors discussed above deprived him of a fair trial or a fair sentencing hearing. We disagree and decline to grant relief under this proposition of error.

¶ 45 The issue in Ochoa's ninth proposition of error is the appropriate aiding and abetting instructions to be used in a malice murder case when the evidence reflects that the defendant aided and abetted in first degree malice murder. At the outset, it should be noted that the State's theory of the case was that Ochoa was the shooter and that Torres aided and abetted in the killings. The evidence supports this theory. Ochoa appears to argue that the evidence also suggests that he may have simply aided and abetted in the killings. This claim is, at best, tenuous. Nonetheless, we review Ochoa's objections to the aiding and abetting instructions.

¶ 46 This Court has stated that “in a malice murder case the State must prove the aider and abetter personally intended the death of the victim and aided and abetted with full knowledge of the intent of the perpetrator.” FN58 “Aiding and abetting in a crime requires the State to show that the accused procured the crime to be done, or aided, assisted, abetted, advised or encouraged the commission of the crime.” FN59 Moreover, while mere presence does not constitute a criminal act, “only slight participation is needed to change a person's status from mere spectator into an aider and abettor.” FN60

FN58. Johnson v. State, 928 P.2d 309, 315–16 (Okl.Cr.1996). Accord Cannon v. State, 904 P.2d 89, 99 (Okl.Cr.1995); but see Conover v. State, 933 P.2d 904, 914–16 (Okl.Cr.1997). FN59. Spears v. State, 900 P.2d 431, 438 (Okl.Cr.) (citations omitted), cert. denied, 516 U.S. 1031, 116 S.Ct. 678, 133 L.Ed.2d 527 (1995). FN60. Id.

¶ 47 Ochoa argues the standard Oklahoma Uniform Jury Instructions 1st ed. (OUJI–CR 1st ed.) on aiding and abetting, which were given to the jury in his case, were inadequate to set forth the elements of aiding and abetting in a malice murder case.FN61 At issue are Jury Instructions 11–12, which are identical to OUJI–CR 1st ed. 204–05. Ochoa contends the standard aiding and abetting instructions replace the specific intent to kill in a malice murder case with a general criminal intent, thus, lessening the State's burden of proof. FN61. The trial court used the OUJI–CR 1st ed., which went into effect in 1981. About a month after Ochoa's trial, this Court issued the revised OUJI–CR 2d ed.

¶ 48 The question here—the appropriate aiding and abetting instructions in a malice murder case—was answered in Johnson v. State. FN62 Like Ochoa, the appellant in Johnson complained that the trial court erred in using the Oklahoma Uniform Instructions on aiding and abetting in a first degree malice murder case. Like Ochoa, Johnson argued the instructions allowed the jury to replace a general intent for a specific intent to kill thus lessening or changing the State's burden of proof. The Johnson Court rejected this argument finding that these instructions in conjunction with the instructions on first degree murder properly set out Oklahoma law and channeled the jury's discretion. Johnson controls here. Accordingly, we find the instructions in Ochoa's case properly set forth the law, did not diminish the State's burden of proof and adequately channeled the jury's discretion. Plain error did not occur. FN62. 928 P.2d at 315–16.

¶ 49 Ochoa also complains because the instructions do not set out separate aiding and abetting instructions for murder and burglary. We find the instructions are not misleading or confusing, and relief is not warranted.

¶ 50 In his tenth proposition of error, Ochoa argues that Jury Instruction 6 is erroneous. Jury Instruction 6 instructed Ochoa's jury that: No person may be convicted of Murder in the First Degree unless his conduct caused the death of the person allegedly killed. A death is caused by conduct if the conduct is a substantial factor in bringing about the death and the conduct is dangerous or destroys life. FN63. Vol. III O.R. at 573. There was no objection to the instruction; we review for plain error.

¶ 51 As Ochoa points out the comments to OUJI–CR 1st ed. 426—which is essentially the same as Instruction 6 in this case—recommends the instruction only be given when the actual cause of death is disputed. The State concedes that the facts of this case do not warrant giving the instruction. In Smith v. State FN64 a similar error occurred. There, despite finding error, the Court found that “[t]he instructions, when read as a whole, accurately state the applicable law and preclude the possibility that the jury may have believed it appropriate to convict Appellant of first degree murder absent a finding of intent.” FN65 Likewise, here the instruction did not confuse the jury as to its role or lessen the State's burden of proof. Ochoa has failed to show how he was burdened by such an instruction. There was no plain error.

FN64. 932 P.2d 521, 533–534 (Okl.Cr.1996). FN65. Id. at 534. See Sadler v. State, 846 P.2d 377, 387 (Okl.Cr.1993).

¶ 52 In his eleventh proposition of error, Ochoa argues the evidence is insufficient to sustain his convictions. We disagree. The evidence at trial revealed that Ochoa and Torres went to the Yanez/Morales home during the early morning hours of July 12, 1993. They parked their car several blocks from the victims' home and removed a gun from the car. The men forcibly entered the victims' home. Ochoa and Torres' activities awakened the Yanez/Morales children, who observed some of the defendants' actions. Francisco, victim Morales' son, observed a man in a black t-shirt shoot his father. Christina, victim Yanez's daughter, identified Ochoa as the man in the black t-shirt. Christina identified Torres as the other man in her home. Both men were arrested a short distance from the Yanez/Morales home. This evidence amply supports Ochoa's convictions for murder and burglary.

Prosecutorial Misconduct

¶ 53 In Proposition XX, Ochoa alleges prosecutorial misconduct occurred during closing arguments in both the first and second stage of trial. At trial, Ochoa failed to object to many of the comments now raised as errors on appeal. Ochoa has waived such objections. Other comments about which Ochoa now complains fall within the broad parameters of effective advocacy and do not constitute error. Nonetheless, several of the prosecutor's comments warrant closer examination.

¶ 54 During first stage closing argument, the prosecutor argued: “All I've got to say is why do you think we're asking you to convict? Do you think we're trying to prosecute somebody that's innocent?” FN66 Torres objected to the comment stating “there is a presumption of innocence.” FN67 The trial court stated, “That's correct, but—proceed.” FN68 Since Ochoa did not object to the comment, we review for plain error. In Miller v. State,FN69 the Court found it was fundamental error for the prosecutor to state in closing argument that “[the cloak of innocence had] been ripped away from him by the testimony of three men—four men, actually. [The defendant] stands guilty as charged.” FN70 Likewise, in Hamilton v. State,FN71 the Court found it error for the prosecutor to state that the cloak of innocence had been stripped from the defendant; however, the Court found the error harmless. Here, although the prosecutor did not use the phrase “cloak of innocence,” his rhetorical question that he would not prosecute an innocent man impermissibly treaded on Ochoa's presumption of innocence. Such argument cannot be condoned. Nonetheless, like in Hamilton, the comment did not affect the verdict and plain error did not occur.

FN66. Vol. VIII Tr. at 185. FN67. Id. FN68. Id. FN69. 843 P.2d 389 (Okl.Cr.1992). FN70. Id. at 390. FN71. 937 P.2d 1001, 1009–10 (Okl.Cr.1997), cert. denied, 522 U.S. 1059, 118 S.Ct. 716, 139 L.Ed.2d 657 (1998).

¶ 55 In second stage closing argument, the prosecutor argued that if the jury sentenced the defendants to a term of imprisonment the defendants would have food and shelter while the victims “lie cold in their graves.” FN72 This Court has condemned similar arguments by the same prosecutor,FN73 and we continue to do so here. Nonetheless, there was no objection to the comment and we can not say that the comment constituted plain error. The prosecutor also overstated the gang evidence and argued that the motive for the killings was to gain higher status in the gang. The evidence did not support this claim. In addition, the prosecutor improperly pleaded with the jury to do justice “and the only way you can do that is bring back a sentence of death.” FN74 He also told the jury “If this isn't a death penalty case, what is?” FN75 It is error for a prosecutor to refer to facts not in evidence and it is error for the prosecutor to state his personal opinion as to the appropriateness of the death penalty. FN76 We are disturbed that the prosecutor risked reversal on appeal by employing such improper tactics. However, Ochoa has failed to show that the comments affected the outcome of his case and we find the errors harmless.

FN72. Vol. X Tr. at 286–87. FN73. Duckett v. State, 919 P.2d 7, 19 (Okl.Cr.1995). FN74. Vol. X Tr. at 301. FN75. Id. at 297. FN76. McCarty v. State, 765 P.2d 1215, 1221(Okl.Cr.1988) (“Mr. Macy improperly expressed his personal opinion as to the death penalty by stating, ‘this defendant deserves it ... This is a proper case for the death penalty ... and justice demands it.’ Such argument was not based on evidence supporting any alleged aggravating circumstance, but was simply a statement of Mr. Macy's personal opinion as to the appropriateness of the death penalty and, as such, was clearly improper.”)

Capital Sentencing Stage of Trial

¶ 56 Ochoa's twelfth and thirteenth propositions of error concern the continuing threat aggravating circumstance used to support his death sentence. In Proposition XII, Ochoa argues the trial court erred in allowing evidence of his gang affiliation to be introduced to prove continuing threat. In Proposition XIII, Ochoa argues the evidence was insufficient to support the jury's finding that he posed a continuing threat to society. These two propositions are closely related, and we consider them together.

¶ 57 Oklahoma provides that the death penalty may be considered an appropriate punishment for first degree murder only in certain specific cases, which are narrowly defined by statutory aggravating circumstances.FN77 At issue here is the continuing threat aggravating circumstance which Oklahoma defines as the “existence of a probability that the defendant would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society.” FN78 To prove this aggravating circumstance, the State relied on (1) the facts of the crime itself, and (2) Ochoa's affiliation with the Southside Locos, a local gang.

FN77. 21 O.S.1991, § 701.12. FN78. 21 O.S.1991, § 701.12(7).

¶ 58 Ochoa argues that admission of evidence of his gang affiliation was error. As an initial matter, we note that in his reply brief Ochoa raises the issue of whether the admission of the gang affiliation evidence violated Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals,FN79 and Taylor v. State.FN80 Because Ochoa did not raise this issue in his brief-in-chief, the issue is waived and we will not consider it.FN81 FN79. 509 U.S. 579, 113 S.Ct. 2786, 125 L.Ed.2d 469 (1993). FN80. 889 P.2d 319, 329–30 (Okl.Cr.1995). FN81. Rule 3.4(F)(1), Rules of the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals, Title 22, Ch.18, App.

¶ 59 In his brief-in-chief, Ochoa argues that admission of the gang evidence violated the First and Fourteenth Amendments of the federal constitution and violated the Supreme Court's ruling in Dawson v. Delaware.FN82 In his majority opinion in Dawson, Chief Justice Rhenquist held that “the First and Fourteenth Amendments prohibit the introduction in a capital sentencing proceeding of the fact that the defendant was a member of an organization called the Aryan Brotherhood, where the evidence has no relevance to the issues being decided in the proceeding.” FN83 Although the Court recognized “the First Amendment protects an individual's right to join groups and associate with others holding similar beliefs,” FN84 the Court rejected Dawson's claim that evidence of his membership in the Aryan Brotherhood was per se invalid.

FN82. 503 U.S. 159, 112 S.Ct. 1093, 117 L.Ed.2d 309 (1992). FN83. Id. at 161, 112 S.Ct. at 1095. FN84. Id. at 162, 112 S.Ct. at 1096.

¶ 60 In finding evidence of Dawson's membership in the Aryan Brotherhood to be improper, the Court appears to have been particularly struck by two facts: (1) the Aryan Brotherhood evidence was not connected to the murder of Dawson's victim, who was white; and (2) the prosecution failed to prove that the Aryan Brotherhood was involved in any criminal activity. Rather, at issue in Dawson was simply the following stipulation: “ ‘The Aryan Brotherhood refers to a white racist prison gang that began in the 1960's in California in response to other gangs of racial minorities. Separate gangs calling themselves the Aryan Brotherhood now exist in many state prisons including Delaware.’ ” FN85 Without any other evidence of criminal activity, Dawson's membership in the Aryan Brotherhood simply showed he was a racist and/or a member of a racist organization, and that alone is not proper evidence. Nonetheless, the Court did not close the door to all evidence relating to a defendant's associations. The Court noted, “In many cases, for example, associational evidence might serve a legitimate purpose in showing that a defendant represents a future danger to society. A defendant's membership in an organization that endorses the killing of any identifiable group, for example, might be relevant to a jury's inquiry into whether the defendant will be dangerous in the future.” FN86

FN85. Id. at 162, 112 S.Ct. at 1096. FN86. Id. at 166, 112 S.Ct. at 1098.

¶ 61 The issue before us is Ochoa's membership in the Southside Locos. In contrast to Dawson, here the State introduced not only evidence of Ochoa's membership in the gang, but also introduced evidence that the Southside Locos engaged in criminal activity ranging from graffiti to drug trafficking to murder. This type of membership in a criminal gang is the type of associational evidence that the Supreme Court viewed as relevant and permissible in Dawson. The problem here for the State is not the admissibility of the evidence itself, but the ultimate probative value of this evidence in this particular case.

¶ 62 The evidence of Ochoa's membership in or affiliation with the Southside Locos is, at best, of marginal value. There is no evidence that the murders of Maria Yanez or Francisco Morales were in any way connected to the gang or committed on behalf of or to earn status in the gang. Indeed, the State in its brief explicitly states, “No motive was ever discerned for the crime and it appears the Morales' home may have been picked at random.” FN87 Further, although the State introduced evidence that the Southside Locos engaged in a variety of criminal activities, the State utterly failed to tie Ochoa to these criminal activities. There is absolutely no evidence that Ochoa ever engaged in any kind of criminal activity connected with the Southside Locos. The only evidence of Ochoa's affiliation with the gang is that Ochoa told a police officer that he was a member of the Southside Locos and he sported a tattoo of a “cholo,” which is a purported symbol of gang membership. The State offered nothing else to show the nature, extent or value of Ochoa's relationship with the gang. Such lack of connection between the gang's criminal activity and Ochoa makes this evidence, while admissible, of very marginal value as to the question of whether Ochoa himself poses a continuing threat to society. The marginal quality of this evidence thus begs the next question: is the evidence sufficient to support the continuing threat aggravating circumstance. The answer is no.

FN87. St. Br. at 63.

¶ 63 As stated above, the State not only failed to show that Ochoa engaged in any criminal gang activity, but also the State failed to show that Ochoa ever committed any crime. Ochoa had no prior criminal record and he had no prior unadjudicated offenses. There was no evidence that since the murders Ochoa had engaged in any violent or illegal activities. This lack of evidence of criminal activity on the part of Ochoa stands in marked contrast with the requirement “that the State present sufficient evidence concerning prior convictions or unadjudicated crimes to show a pattern of criminal conduct that will likely continue in the future to support its ‘continuing threat’ contention.' ” FN88 The State utterly failed to make such a showing here. FN88. Perry v. State, 893 P.2d 521, 536 (Okl.Cr.1995) (quoting Malone v. State, 876 P.2d 707, 717 (Okl.Cr.1994)).