Executed January 17, 2007 06:21 p.m. CST by Lethal Injection in Texas

3rd murderer executed in U.S. in 2007

1060th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

2nd murderer executed in Texas in 2007

381st murderer executed in Texas since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

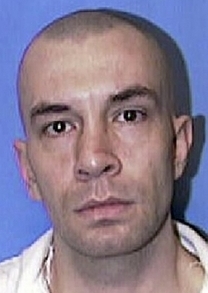

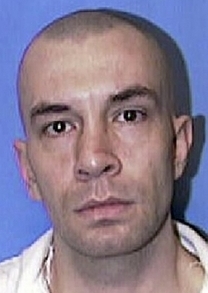

Johnathan Bryant Moore W / M / 20 - 32 |

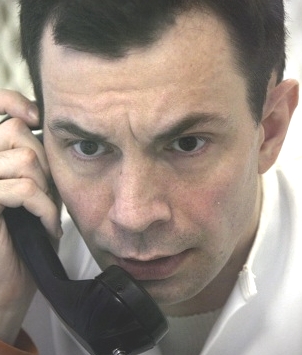

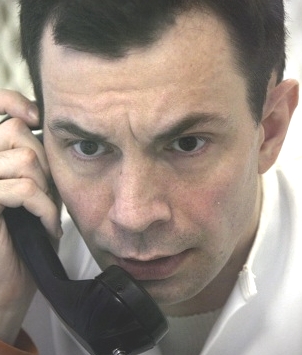

Fabian Dominquez OFFICER H / M / 29 |

Citations:

Moore v. State, 999 S.W.3d 385 (Tex.Cr.App. 1999) (Direct Appeal).

Moore v. Dretke, 182 Fed.Appx. 329 (5th Cir. 2006) (Habeas).

Final/Special Meal:

Kraft Cheese & Macaroni, Beef Flavored Rice-A-Roni.

Final Words:

Johnathan Moore repeatedly apologized to the officer's widow. "It was done out of fear, stupidity and immaturity. I’m sorry. I did not know the man but for a few seconds before I shot him. It wasn’t until I got locked up and saw that newspaper, I saw his face and his smile and I knew he was a good man. I am sorry for all your family and for my disrespect — he deserved better. He wished her happiness. He then counseled a friend who was a witness to quit using heroin and methadone. He told his father that he loved him.

Internet Sources:

Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Executed Offenders (Jonathan Moore)

Inmate: Jonathan Bryant Moore

Wednesday, January 10, 2007 - Media Advisory: Johnathan Moore Scheduled For Execution

AUSTIN – Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott offers the following information about Johnathan Moore, who is scheduled to be executed after 6 p.m. Wednesday, January 17, 2007, for the 1995 shooting death of San Antonio police officer Fabian Dominguez.

FACTS OF THE CRIME

In the early morning hours of January 15, 1995, San Antonio police officer Fabian Dominguez was driving home from work when he spotted a burglary in progress at a residence. Dominguez, who was still in his uniform, pulled into the driveway of the residence, blocking a car occupied by Johnathan Moore, Pete Dowdle and Paul Cameron, who were finishing their second trip to burglarize the home.

Gun drawn, Dominguez approached the vehicle and repeatedly ordered the three men to get out of the car to no avail. After taking the car keys from Dowdle, the driver, Dominguez approached the passenger side of the car with his gun drawn at which point Moore, who was in the front passenger seat, pulled out a .25 caliber automatic gun and shot Dominguez. The officer fell to the ground, dropping his gun into the rear seat of the car. Moore got out of the car, recovered the car keys and retuned them to Dowdle. Moore then grabbed Dominguez’s gun and shot the officer three times in the head.

Officer Dominguez died from multiple gunshot wounds to the head. Ballistics established that the wounds were inflicted by one shot from Moore’s .25 caliber handgun and three shots from the officer’s .40 caliber service weapon.

After leaving the scene of the crime, Moore, Cameron, Dowdle, and Moore’s girlfriend, Meredith Nichols, traveled to a plot of land near Pipe Creek, Texas, where they disposed of both murder weapons and the stolen items. Moore was arrested the next day following a high speed chase. While under arrest, Moore signed a full and detailed confession.

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

October 1996 -- Moore was convicted of capital murder and sentenced to death in Bexar County.

April 1999 -- Moore’s conviction and sentence were upheld on direct appeal.

May 2002 -- The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals denied Moore’s application for writ of habeas corpus.

March 2005 -- A U.S. district court denied Moore’s federal habeas corpus petition

May 2006 --The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the U.S. district court’s denial of habeas corpus relief.

November 2006 -- The U.S. Supreme Court denied Moore’s petition for writ of certiorari.

CRIMINAL HISTORY

Johnathan Moore, born on April 4, 1974, was twenty years old on the date he committed capital murder.

Texas Department of Criminal Justice records reflect that, in addition to the capital murder of the San Antonio police officer, Moore was charged with criminal trespass in Bexar County in June 1993 and with the burglary of a vehicle in Bexar County in January 1995. In January 1995, Moore was charged with evading arrest in conjunction with the high speed chase that resulted in his capture on the capital murder charge. Texas Department of Criminal Justice records show that Moore made at least two failed escape attempts from the Bexar County jail while he was in the lockup awaiting his capital murder trial in the slaying of the police officer.

"Man executed for gunning down officer; Self-described fascist apologizes to victim's widow," by Michael Graczyk. (Associated Press Jan. 18, 2007, 2:05PM)

HUNTSVILLE — A self-described fascist who adopted the dark punk and goth lifestyle was executed Wednesday for the slaying of a San Antonio police officer 12 years ago. Johnathan Moore repeatedly apologized to the officer's widow. "It was done out of fear, stupidity and immaturity. It wasn't until I got locked up and saw the newspaper; I saw his face and smile and I realized I had killed a good man." Moore told Jennifer Morgan, who stood next to the death chamber window surrounded by comforting friends. He wished her happiness. He then counseled a friend who was a witness to quit using heroin and methadone. He told his father that he loved him.

He was pronounced dead at 6:21 p.m., eight minutes after the lethal dose of drugs began. Moore, 32, was the second condemned Texas prisoner executed this year and the second of five scheduled to die this month in the nation's busiest capital punishment state.

Moore was convicted of gunning down Fabian Dominguez, 29, who interrupted Moore and two companions during the burglary of a house in the officer's neighborhood in January 1995. Dominguez was returning home from his shift when he spotted a suspicious car in the driveway of the house and stopped to investigate. When he confronted Moore, seated in the passenger side of the car, Moore opened fire with a .25-caliber handgun. Moore also retrieved the officer's service revolver and shot him three more times in the head. He was arrested the following day after leading police on a chase into Bandera County.

The U.S. Supreme Court refused to review Moore's case last year. An appeal to stop the punishment by challenging the state's lethal injection execution procedure was rejected Tuesday by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, and the Supreme Court then rejected a similar appeal about two hours before Moore's execution. The San Antonio Police Officers Association chartered a bus so about two dozen officers could honor their fallen colleague while prison officials inside the Huntsville Unit of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice carried out the punishment.

Moore is the first person convicted of killing a San Antonio police officer to go to the death chamber since the state resumed carrying out capital punishment in 1982. The two others with Moore the night of the shooting were arrested a short time after his arrest. Peter Dowdle, now 29, is serving a 25-year prison term. Paul Cameron, also 29, is serving life.

On a Web site, Moore said he "hung out with the Industrial, Punk and Goth scene" and described himself as "a full-blown fascist." He added: "I have disappointed and let down everybody that has ever loved me." Moore's capital murder trial was hardly routine.

Following his conviction and before punishment testimony was to begin, he fired his lawyers so he could represent himself, then rehired them the following day. Before the trial, he had tried to escape from custody during a visit to a health clinic, grabbing a stun gun and a can of pepper spray hidden in a restroom and unsuccessfully trying to overpower a deputy guarding him. Authorities found a handcuff key inside a shoe in his cell.

"S.A. officer's killer tells widow he's sorry," by Maro Robbins and Vianna Davila. (Web Posted: 01/18/2007 12:30 AM CST)

HUNTSVILLE — A tear had already slid from behind his glasses when Johnathan Moore turned his head toward the woman he'd widowed a dozen years earlier. "Jennifer, where are you at?" Moore said Wednesday night as his eyes searched the execution chamber for the widow of the police officer he had murdered while fleeing the scene of a burglary.

Jennifer Morgan stood a few feet away, watching through iron bars and Plexiglas, while outside the prison some 30 supporters had gathered to honor her slain husband, Officer Fabian Dominguez. "Jennifer, I'm sorry," he said, his jaw beginning to quake. "I did not know the man but for a few seconds before I shot him. It was done out of fear, stupidity and immaturity."

Morgan listened silently with her sister's arm around her and two friends nearby. When the prisoner first spoke, the group appeared to flinch. But, afterward, Morgan seemed relaxed. "I'm feeling relief," she said later, "almost like we held our breath for 12 years and now we can let it out."

Morgan, her twin daughters and her supporters had traveled nearly 200 icy miles for this moment and what it represented to them: justice for the slain patrolman and a precedent for San Antonio law enforcement. Moore's execution was the first to punish the murder of a Bexar County police officer since Texas resumed the death penalty in 1973.

The vigil outside the prison had been muted. The officers and their friends held fluorescent batons that glowed softly with a shade of police blue. Some had graduated from the police academy alongside Dominguez. Others were widows of officers who had died in the line of duty.

Still others didn't know Dominguez personally but still felt a personal stake in punishing Moore, who had shot his victim six times at close range. "I would push the needle (myself)," said Teddy Stewart, president of the San Antonio Police Officers Association, which had organized the pilgrimage and chartered a bus.

Strapped to the gurney, Moore made it clear that he regretted his crime as soon as he was locked up and read newspaper coverage of the man he'd murdered. "I saw his face and his smile and I knew he was a good man," Moore told Morgan. "I am sorry for all your family and my disrespect. He deserved better."

Moore next turned his gaze toward his father, a retired electrician who last year lost his wife — Moore's mother — and still keeps her voice on the answering machine. Moore told his dad, his half-brother and a longtime friend that he loved them. Then he addressed a sobbing woman. This was a woman he'd met and fallen in love with by mail. Her name was now tattooed on his knuckles and he'd reportedly married her days earlier. "Quit the heroin," he said.

He stopped and then, seconds later, started to add something, but the words hung half-formed on his lips as the chemicals took effect. His eyes closed, and by the time he was pronounced dead 10 minutes later, he already appeared pale.

Moore had been the most prominent defendant in the case, but his death left two others still in prison. Paul Cameron's life sentence is expected to keep him in custody at least until 2035, but parole for Peter Dowdle could come as soon as July. No one, however, was thinking this far ahead Wednesday evening after they left the prison and returned to a nearby motel.

Asked what she and her family would do next, Morgan looked at her twin daughters, Miranda and Michaela, who had been infants at the time of their father's death. "Now we go back," Morgan said, "And go to school." For the moment, at least, their lives seemed to be returning to normal. At the mention of school, Michaela rolled her eyes.

"Daughters of murdered cop wait in cold outside for closure," by Vianna Davila. (Web Posted: 01/18/2007 12:50 AM CST)

HUNTSVILLE — Waiting for word that the man who killed their father had been put to death, twins Michaela and Miranda Dominguez wondered — what does an execution chamber look like? They posed the question as they huddled in freezing temperatures outside the building where Johnathan Moore was about to die, 12 years after he murdered their dad, San Antonio Police Officer Fabian Dominguez.

Their stepfather, Mitchell Morgan, described the room he had seen, although, like the girls, he would not witness the execution. He told them about the window that lets witnesses look in and the microphone that would transmit his last words. "We can hear what he says," Morgan explained, but Moore couldn't hear anyone else. As they listened, Miranda twirled in her hands a neon blue glow stick that police officers had handed out to the supporters outside.

Both now 12, the girls were only babies when their father was killed in 1995. They had accompanied their mother, Jennifer, on this trip for closure, to see Moore brought to justice. Now they were two tiny figures trying to keep warm among dozens of police officers waiting outside the red-bricked prison. "Think summer," one officer said as he grinned at the girls. Another officer handed one of the twins his gloves, huge on her hands. "Now you look like Shrek," someone said and laughed.

But when they got word that Moore was dead, the twins fell silent. Like everyone else, they lifted their glow sticks in the air. Two hours later, the girls returned to their hotel room with their family, eager for dinner and maybe a movie. They were not quite sure how to begin grasping the day's events. "I don't know how I feel," Miranda said. Like her sister, she has begun to wonder about the man who killed their father. "It's just kind of weird to think he was a real person," Michaela said.

They still hunger for stories about their father, killed before they could know him. "When other people ask about him, we don't really have anything to say," Michaela said. For now, they will hold on to what they can: the letter from Dominguez's police academy classmate; the blue T-shirts bearing their father's badge number and a Bible quote, John 15:13: "Greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends."

And on a chain around her neck, Michaela wears a silver ring of two clasped hands. Everyone jokes the ring is from Michaela's secret boyfriend. But it really used to belong to her mother, a gift from the girls' father. "I like it, though," Michaela said, and smiled.

"Convicted San Antonio cop killer executed." (AP 06:41 PM CST on Wednesday, January 17, 2007)

HUNTSVILLE, Texas – A self-described fascist who adopted the dark punk and goth lifestyle was executed Wednesday for the slaying of a San Antonio police officer 12 years ago.

Johnathan Moore repeatedly apologized to the officer's widow. "It was done out of fear, stupidity and immaturity. It wasn't until I got locked up and saw the newspaper; I saw his face and smile and I realized I had killed a good man." Moore told Jennifer Morgan, who stood next to the death chamber window surrounded by comforting friends. He wished her happiness. He then counseled a friend who was a witness to quit using heroin and methadone. He told his father that he loved him.

He was pronounced dead at 6:21 p.m., eight minutes after the lethal dose of drugs began. Moore, 32, was the second condemned Texas prisoner executed this year and the second of five scheduled to die this month in the nation's busiest capital punishment state.

Moore was convicted of gunning down Fabian Dominguez, 29, who interrupted Moore and two companions during the burglary of a house in the officer's neighborhood in January 1995. Dominguez was returning home from his overnight shift when he spotted a suspicious car in the driveway of the house and stopped to investigate. When he confronted Moore, seated in the passenger side of the car, Moore opened fire with a .25-caliber handgun. Moore also retrieved the officer's service revolver and shot him three more times in the head. He was arrested the day following the shooting after leading police on a chase into neighboring Bandera County and wrecking his car by hitting a couple of police cars.

The U.S. Supreme Court refused to review Moore's case late last year. An appeal to stop the punishment by challenging the state's lethal injection execution procedure was rejected Tuesday by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, and the Supreme Court then rejected a similar appeal about two hours before Moore's scheduled execution time. The San Antonio Police Officers Association chartered a bus and expected to have several dozen officers outside the Huntsville Unit of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice to honor their fallen colleague while prison officials inside carried out the punishment.

Dominguez's widow, Jennifer Morgan, planned to be among the witnesses. "I don't want to change the outcome," she said. "He did a horrible thing and as far as I know hasn't shown a lot of remorse about it." Moore is the first person convicted of killing a San Antonio police officer to go to the death chamber since the state resumed carrying out capital punishment in 1982.

The two others with Moore the night of the shooting were arrested a short time after his arrest. Peter Dowdle, now 29, is serving a 25-year prison term. Paul Cameron, also 29, is serving life.

On an Internet site, Moore said he "hung out with the Industrial, Punk and Goth scene" and described himself as "a full-blown fascist." But he added: "I have disappointed and let down everybody that has ever loved me."

Moore told the San Antonio Express-News last week the shooting was the result of "fear and stupidity" and credited Dominguez for being "the man." "He was taking charge and he was running right into a situation that required a lot of strength and courage," Moore said. "I think about that a lot."

Moore's capital murder trial was hardly routine. Following his conviction and before punishment testimony was to begin at his trial, he fired his lawyers so he could represent himself, then rehired them the following day. Before the trial, he had tried to escape from custody during a visit to a health clinic, grabbing a stun gun and a can of pepper spray hidden for him in a restroom and unsuccessfully trying to overpower a deputy guarding him. Authorities found a handcuff key inside a shoe in his cell.

During the punishment phase, his mother, from the witness stand, shouted profanities at lawyers for both sides and was arrested after deputies said she bit a court bailiff.

Dominguez had been an officer about 2 1/2 years at the time of his death. He had infant twin daughters, who now are 12. More than a dozen other Texas inmates already have execution dates for 2007, including two more next week.

On Jan. 24, Larry Swearingen, 35, is set to die for the December 1998 abduction and strangling of a 19-year-old Montgomery County woman, Melissa Trotter. The next day, Ronald Chambers, 51, is scheduled for injection for abducting and fatally shooting Mike McMahan, 22, a Texas Tech student from Washington state, during an April 1975 carjacking in Dallas.

"Convicted cop killer executed," by Stewart Smith. (Published: January 17, 2007 11:27 pm)

Johnathan Moore gave a full confession to the authorities after shooting San Antonio Police Officer Fabian Dominguez in 1995. However, it wasn’t until he offered his last words shortly before his execution that Moore admitted his actions were out of “fear, stupidity and immaturity.” “I’m sorry. I did not know the man but for a few seconds before I shot him,” Moore said, addressing Dominguez’s widow, Jennifer Morgan. “It wasn’t until I got locked up and saw that newspaper, I saw his face and his smile and I knew he was a good man. I am sorry for all your family and for my disrespect — he deserved better.”

Moore’s friends and family members huddled closely together inside the viewing room. Moore admonished one of his friends to stop using heroin and methadone and told his father he loved him. He was pronounced dead at 6:21 p.m.

Moore, 32, was the second condemned Texas prisoner executed this year and the second of five scheduled to die this month in the nation’s busiest capital punishment state.

Moore was convicted of gunning down Dominguez, 29, who interrupted Moore and two companions during the burglary of a house in the officer’s neighborhood in January 1995. Dominguez was returning home from his overnight shift when he spotted a suspicious car in the driveway of the house and stopped to investigate. When he confronted Moore, seated in the passenger side of the car, Moore opened fire with a .25-caliber handgun. Moore also retrieved the officer’s service revolver and shot him three more times in the head. He was arrested the day following the shooting after leading police on a chase into neighboring Bandera County and wrecking his car by hitting a couple of police cars.

The U.S. Supreme Court refused to review Moore’s case late last year. An appeal to stop the punishment by challenging the state’s lethal injection execution procedure was rejected Tuesday by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, and the Supreme Court then rejected a similar appeal about two hours before Moore’s scheduled execution time.

The San Antonio Police Officers Association chartered a bus and about two dozen officers holding blue glow sticks stood outside the Huntsville Unit of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice to honor their fallen colleague while prison officials inside carried out the punishment. Moore is the first person convicted of killing a San Antonio police officer to go to the death chamber since the state resumed carrying out capital punishment in 1982.

The two others with Moore the night of the shooting were arrested a short time after his arrest. Peter Dowdle, now 29, is serving a 25-year prison term. Paul Cameron, also 29, is serving life.

On an Internet site, Moore said he “hung out with the Industrial, Punk and Goth scene” and described himself as “a full-blown fascist.” But he added: “I have disappointed and let down everybody that has ever loved me.” The Associated Press contributed to this story.

Texas Execution Information Center by David Carson.

Johnathan Bryant Moore, 32, was executed by lethal injection on 17 January 2007 in Huntsville, Texas for killing a police officer while burglarizing a home.

On 15 January 1995, Moore, then 20, Paul Cameron, 17, and Peter Dowdle, 17, drove to the San Antonio home of William Braden and burglarized it. After stealing some items and leaving, the men returned to the house to burglarize it again. Dowdle backed their car into Braden's driveway and stayed inside while Moore and Cameron burglarized the house.

San Antonio Police Officer Fabian Dominguez, 29, was driving home from work before sunrise and was a few blocks from home when he spotted what appeared to be a burglary in progress. Dominguez was driving his personal vehicle, but he was still in uniform. He pulled into Braden's driveway, blocking the suspects' car. The three men had concluded their second burglary and were inside the vehicle. Dominguez drew his gun, approached the vehicle, and ordered the men out of the car, but they failed to comply. Dominguez took the keys from Dowdle, then walked around to the passenger side. Moore, who was in the front passenger seat, then pulled out a .25 caliber semiautomatic pistol and shot Dominguez in the face. Dominguez dropped his gun into the car and fell to the ground. Moore then got out of the car, took the keys, and gave them back to Dowdle. He then grabbed Dominguez's gun and shot him three times in the head.

After leaving the scene of the crime, the men picked up Moore's girlfriend, Meredith Nichols, then they drove to a field near Pipe Creek in Bandera County, northwest of San Antonio. There, they disposed of both murder weapons and the stolen items.

The next day, San Antonio police put Moore under surveillance as a suspect in the murder. He was spotted committing traffic violations while driving around with Nichols in her car. When police signaled him to pull over, he sped away. He was captured and arrested after a 20-minute high-speed chase that ended in Bandera County when he lost control of his car and crashed into two police cars. After his arrest, he confessed to the murder and said he could see that the man he shot was wearing a police uniform. He said that he fled from the police because "I figured pretty much that the cops knew I was the one that shot the cop." Cameron and Dowdle were arrested a short time later.

Moore had a previous arrest for criminal trespassing in June 1993. He was given deferred adjudication. The state also presented evidence that Moore was charged with burglary in January 1995 and that he attempted to escape from the Bexar County jail twice while awaiting his capital murder trial.

A jury convicted Moore of capital murder in October 1996 and sentenced him to death. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the conviction and sentence in April 1999. All of his subsequent appeals in state and federal court were denied.

Paul Cameron was also convicted of capital murder and was sentenced to life in prison. He is not eligible for parole until 2035. Peter Elmer Dowdle was convicted of engaging in an organized criminal act and was sentenced to 25 years in prison. He becomes eligible for parole this July.

On a web site, Moore wrote that at the time of the murder, he was an anarchist, but while in prison, he rejected that philosophy and became "a full-blown fascist." He also wrote, "I have disappointed and let down everybody that has ever loved me." "I've destroyed the Dominguez family," Moore said an interview from death row the week before his execution. "I put a whole lot of people through a whole lot of pain." He said that at the age of 20, he was enamored with guns, the punk/goth lifestyle, and the film "Natural Born Killers," and that he was mean and usually stoned. He blamed his actions on the night of the murder on "fear and stupidity."

Moore said that when Officer Dominguez approached him, Dominguez had his weapon pointed at his head. Instead of raising his hands as ordered, he brushed the policeman's gun aside and fired several shots from the gun in his hand. Then, he said he wondered what would happen to him if Dominguez survived. He decided that since the officer had just held a loaded gun to his head, he would make him pay. It was a decision he would regret. Moore said in the interview that he learned about Fabian Dominguez and his family and came to admire him. "He was the man," Moore said. "He was taking charge, and he was running right into a situation that required a lot of strength and courage. I think about that a lot."

At his execution, Moore scanned one of the viewing rooms for the widow of his victim. "Jennifer, where are you at?" he asked. After he spotted her, he said, "Jennifer, I'm sorry. I did not know the man but for a few seconds before I shot him. It was done out of fear, stupidity, and immaturity. It wasn't until I got locked up and saw the newspaper ... I saw his face and his smile, and I knew he was a good man. I am sorry for all your family and my disrespect. He deserved better." Moore then told his father, half-brother, and a longtime friend that he loved them. He told a woman who he had met by mail while on death row and had married by proxy a few days earlier to "quit the heroin." The lethal injection was then started. Moore tried to speak again, but the chemicals quickly took effect, and he lost consciousness. He was pronounced dead at 6:21 p.m.

"I'm feeling relief," Jennifer Morgan - who has remarried since her husband's slaying - said afterward. "Almost like we held our breath for twelve years, and now we can let it out."

On January 15, 1995, at approximately 5:00 a.m., San Antonio police officer Fabian Dominguez went off duty and began driving home in his personal vehicle. Officer Dominguez lived in San Antonio with his wife and infant twin daughters. Officer Dominguez was a few blocks from home when he noticed suspicious activity at a residence. Based on what Officer Dominguez observed, he took action to investigate what appeared to be a burglary in progress.

When he pulled into the driveway, blocking in the suspects’ vehicle, Paul Cameron, Pete Dowdle, and Johnathan Moore were concluding their second trip to burglarize the Braden home. In his voluntary written statement, Moore described the sequence of events leading up to the murder of Officer Dominguez. "For some dumb reason we decided to go back to the house on Country Flower. We went in Pete’s grandmother’s car. . . . Pete drove. I was in the front passenger side of the car and Paul was in the backseat. Pete backed the car into the driveway. Pete stayed out in the car. We had accidently left the front door wide open the first time. Me and Paul went in through the front door. We didn’t have any problem with the dog. All three of us were wearing gloves again. We had left some guns and a compound bow were left from the first time. We got those things. Me and Paul decided to split form the inside. We walked outside and we saw a car passing by. The car stopped and I saw the reverse lights come on. We all got into the car. Pete was behind the wheel. I was in the front passenger seat and Paul was in the backseat. The car pulled into the driveway and pretty much blocked us in. The police officer got out of the car and had his gun pointing at Pete. I could see that this guy was wearing a police uniform. The officer said get out of the car now. I had my window rolled down.

The officer kept repeating “get out of the car”. . . . . I kept telling Pete let’s split but he would not do it. By the time the officer walked up to the car and had the gun pointed at my head. The officer was on the passenger side of Pete’s car. The officer told Pete to give him the car keys and Pete gave it to him. I scooted the officer’s pistol away and I pulled out my gun and shot at him. I believe I shot at him three times. The officer fell to the ground. I already had my gun in my hand when the officer walked up. My gun is a .25 caliber automatic. It’s plated and it’s a Lorcin brand. After I shot the officer his gun fell into the front rear seat of Pete’s car. I got out of the car and I got the car keys and gave them to Pete. I got the officer’s gun and shot the officer three times in the head. I got back in the car and Pete split. Paul was in the backseat during the whole time. Pete didn’t want to get into trouble after I shot the cop so he drove away."

Neighbors across the street heard gunfire coming from the Braden home. Upon receiving a 911 call, police and emergency personnel were immediately dispatched. Officer Dominguez was dead by the time firemen arrived on the scene. The coroner later determined that Officer Dominguez died from multiple gunshot wounds to the head. Ballistics established that the wounds were inflicted by one shot from Moore’s .25 caliber handgun, and three shots from Officer Dominguez’s .40 caliber service weapon.

After leaving the scene of the crime, Moore, Cameron, Dowdle, and Moore’s girlfriend, Meredith Nichols, traveled to a plot of land near Pipe Creek, Texas, where they disposed of both murder weapons and the items stolen from the Braden residence. The following day Moore was developed as a suspect in the burglary. He was subsequently located and seen driving a vehicle that belonged to Nichols. Nichols was a passenger in the vehicle. While under police surveillance, Moore committed numerous traffic violations. When police officers signaled him to pull to the side of the road, a high speed chase ensued. Twenty miles later, Moore and Nichols were captured after Moore careened to the side of the road.

After a brief struggle, San Antonio police officers arrested Moore and took him into custody. In his voluntary statement Moore explained his flight from authorities, stating, “I figured pretty much that the cops knew that I was the one that shot the cop.” Jennifer Morgan, Fabian Dominguez's widow, plans to witness the execution. She said, "Justice needs to prevail, and this is part of it." She said that Moore has shown no remorse, to her knowledge.

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

Johnathan Moore, Jan. 17, 2007, TX

Do Not Execute Johnathan Moore!

On Jan. 15, 1995, Johnathan Moore and two companions were in the process of burglarizing a house when Moore shot an off-duty San Antonio police officer who tried to stop the crime. After his arrest, Moore gave police a voluntary written statement, where he confessed to the crime. He was sentenced to death, while his two codefendants face lighter sentences.

Johnathan Moore should not be executed for this crime. Executing Moore would violate the right to life as proclaimed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and would constitute the ultimate cruel, inhuman, and degrading punishment. Furthermore, the court denied Moore’s request for a competency hearing, even though he has a history of depression and hospitalization. Moore also represented himself on two separate occasions in the trial, before which his lawyers did not present enough evidence to the judge to show that Moore was incompetent, which amounts to ineffective assistance of counsel.

At the time of this crime, Moore was 20 years old. He comes from a very troubled and dysfunctional family, including persistent problems between his parents and possibly serious life-long mental health problems in his mother.

Please write to Gov. Rick Perry on behalf of Johnathan Moore!

"His Crime: Shot down a police officer who surprised him during burglary," by Emanuella Moore. (Updated Jan. 16, 2007)

San Antonio Police Officer Fabian Dale Dominguez was just blocks away from home when he stopped off to investigate a burglary in progress on the morning of Jan. 15, 1995. Dominguez, 29, pulled his car into the driveway, blocking the getaway vehicle that contained burglars Johnathan Moore, Peter Dowdle and Paul Cameron. The father of two approached the car with his gun raised and ordered the teens to surrender. Instead, Moore drew his gun and shot Dominguez three times in the head.

Then the 19-year-old got out of the car, grabbed Dominguez's service pistol, and shot the officer three more times. Dominguez died at the scene. Police caught up with Moore two days later, but he led them on a 20-mile car chase that ended in a crash. Cameron was arrested the same day, and Dowdle turned himself in.

Moore stood trial in 1996 on one charge of capital murder for killing a police officer during a burglary. Based on his history of mental illness, he pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity. Prosecutors claimed Moore knowingly shot a police officer in uniform. They also pointed to his repeated shooting of Dominguez — even after he was down — as evidence of his intent to kill.

Moore's lawyers never denied the murder. Instead, they tried to convince a Bexar County jury that he suffered from schizophrenia, paranoid delusions and severe depression, which prevented him from understanding his actions. Defense psychiatrists cited Moore's troubled background, including an abusive childhood and a stint in a psychiatric hospital, as evidence of an impaired capacity for decision-making. But state mental health experts disagreed, claiming that Moore's problems were behavioral rather than psychological. Prosecutors also introduced school and police records indicating a long history of thefts, burglaries and public mischief.

After deliberating for two hours, jurors convicted Moore of capital murder.

Several times during the trial, Moore's antics outside the jury's presence received just as much attention as the testimony. He attempted suicide at least once while awaiting trial. In the trial's first week, deputies discovered that he tried to escape by tucking a handcuff key into his shoes. He also attempted to fire his court-appointed attorneys, accusing them of failing to investigate allegations that prosecutors forced witnesses to lie under oath. Before his penalty phase, Moore fired his defense team and represented himself for one day before requesting to rehire them. District Judge Sharon McCrae granted his request, prompting his attorneys to call for a competency exam and a mistrial. Both motions were denied.

Moore's mother offered a tearful plea for her son's life and blamed his crime on years of abuse by a relative and a history of depression and suicide attempts. Prosecutors countered her pleas with statements from law enforcement officers, former teachers and friends who testified to Moore's propensity for violence and his "obsession" with satanism, the Goth subculture and punk music. The jury took four hours to sentence Moore to death. Members of the San Antonio Police Department applauded the sentence as it was read.

Moore appealed his convictions based on ineffective counsel claims for failing to investigate his competency to stand trial. His claims were denied, and his execution was scheduled for Wednesday evening.

On Friday, his girlfriend, Naomi Madsen of New York, filed for a marriage license at his request. "I don't need the piece of paper, but I wanted to make him happy before he dies," said Madsen, whose nickname, Lily, is tattooed on Moore's knuckles. "I'm in love with him."

Moore says he has accepted his fate and now is more concerned with earning co-defendant Paul Cameron a reduced sentence. Cameron was also convicted of capital murder as a party to the crime for allegedly coaxing Moore into shooting the officer. He received a life sentence. Peter Dowdle, the driver, received a 25-year sentence on an organized crime charge for his role in the shooting.

"[Paul Cameron] is not guilty of capital murder. He should get some kind of relief, hopefully," Moore said. "I'm trying to help him in any way I can because capital murder, life sentence, 40-year minimum, for a case he wasn't all the way down with in the first place is just wrong."

An interview with death row inmate Johnathan Moore."

I haven't accomplished anything. I wish I had, now looking in hindsight, I wish I had done something to get my name out there, but I didn't, so here I am now, haven't done anything with my life and now I'm going to get killed.

CourtTVnews.com reporter Emanuella Grinberg interviewed Texas death row inmate Johnathan Moore on Jan. 10 at the Polunsky Prison Unit in Livingston, Texas. He was executed Jan. 17. The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity. The video was produced by Mark Grieco.

COURTTVNEWS.COM: Can you describe a typical day on death row?

JOHNATHAN

MOORE: Monotonous. I'm sure that's the answer everyone gives you guys. Just droning, same day every day, it's "Groundhog Day" here, the movie. It's hard to decipher the separate days.

CTV: How are you doing today?

MOORE: Pretty good, pretty good, really good, actually.

CTV: What makes this day so good?

MOORE: Just in general, I know how to live life and feel good about things.

CTV: What do you do to pass the time?

MOORE: Read, write, do some running. I run a lot. You have different little societies in here, groups of friends, and you got different stuff to do, play games, stuff like that.

CTV: What kind of writing do you do?

MOORE: Just pen-pal letters to my friends and stuff.

CTV: Do you write poetry or anything like that?

MOORE: Not so much anymore. I used to, but I got out of it.

CTV: Why?

MOORE: Everybody's doing that in here. I just don't feel like it.

CTV: You said you talk with the other inmates. Are you friends with any of them?

MOORE: A couple. In prison, there's always shifting loyalties. It's a never-ending chess game in here when you're dealing with people. That's why you got to look into yourself and do your own time.

CTV: Where do you fit in?

MOORE: You're playing a chess game and everybody else is playing their pieces against you, so I mean, it's never-ending because no one ever wins. I don't know, it deals with the personalities and stuff you got in here because there's some extreme personalities in here and people are just trying to get along, and some people want to do other people's time.

CTV: Do you get mail from strangers?

MOORE: Lately, I have been. There have been Christian people coming out of the woodwork, saying "Give your life to God," and stuff like that. I have lots of pen pals and old friends from the streets. There's plenty of mail, I suppose.

CTV: How has life in prison changed you?

MOORE: It hasn't changed me. But I'm the same person I was when I got locked up, but I have matured in prison, because when I got locked up I was still, I was 19, thinking and acting like a 16-year-old, emotionally immature. But I've matured since I've been in prison; I guess that's the only change, and karma, I've learned about karma, I've started learning about karma now.

CTV: What have you learned about karma?

MOORE: Just treat people the way you want to be treated and don't hassle people.

CTV: On your MySpace page, you indicate you used to be an anarchist. What made you change to fascism?

MOORE: When I was in the world, I was immature, just thinking about being anti-government and anti-police, just had the mental process of going against everything and I called it anarchy because everybody else called it anarchy back then, little kids and spray-painting anarchy signs and all that crap. The turn to fascism is not so much to be taken literally. I just now think that in general that most men are stupid and shouldn't be able to think for themselves anymore. I'm just disgusted with society in general now.

CTV: Why?

MOORE: It's complicated. A lot of it has to do with guns and people running around, like when I was a kid running around doing stupid shit with guns. I wish I didn't have access to guns in the first place because I wasn't mature enough to handle the responsibility of it. They were all stolen anyhow. But in general, I shouldn't have had access to begin with.

CTV: What do you miss most about life on the outside?

MOORE: Just having fun, having fun with friends. And obviously the lack of women and that concept. But it's still a society in here. It's just different.

CTV: If you weren't in here, what do you think you'd be doing right now?

MOORE: When I was out in the world, I wasn't ready to go to college yet. My parents kept pushing me into college. I ended up starting three times and dropping out three times. But now I've got the will and the ambition to go to school, and I would probably go back to school and pursue a degree in engineering of some sort, electrical engineering ... or at the very least, join the military because that's the easiest way out, just some type of a structured environment to get in ... But I'd be doing some type of schooling now.

CTV: Wouldn't the military have conflicted with your views back then?

MOORE: Back then, yeah, but back then, I still needed structure too. I lacked the tools to survive the way society expects you to survive.

CTV: What is your happiest memory from your childhood?

MOORE: Being in a psychiatric hospital. I was in Laurel Ridge in San Antonio. Yeah, I don't know if you guys are familiar with that. All the kids in there were messed up and we all got along great. It was fun, it was a fun time for me.

CTV: What was fun about it?

MOORE: The fact that I fit in with a bunch of fucked-up kids because at that point in time I didn't fit in with anybody. It wasn't until I got to hang out with a bunch of messed-up kids that I finally found a place to fit in.

CTV: How was your relationship with your parents?

MOORE: My mom died last year. When I was in the world, they were pushing me into school and trying to get good grades and all that and it got to the point I wasn't hearing that any more, so there was a lot of friction on that. They were trying to make me become somebody and I wasn't hearing it. I just wanted to party and have a good time and all that and that was when I got kicked out. We didn't get close close until after I got locked up and then everything came full circle and we realized we were buddies all along and got along.

CTV: As a child, what did you want to grow up to be or do?

MOORE: Until I was like 10 or 12, I was wanting to be a pilot of some sort. Actually, I took flight lessons when I was 12 out of San Antonio International. But I replaced that with skateboarding and then lost all ambition from there and never got it back.

CTV: How old were you when you went to the psychiatric institute?

MOORE: It was either late 15 or early 16. I think that was like six months.

CTV: How do you think that affected you?

MOORE: Positively, because up until then I had a real negative view on everything, but I felt pretty good coming out. It was a good thing. It was a private hospital. I don't know how people turn out from state hospitals.

CTV: What are you good at?

MOORE: Nothing really. I haven't had a chance to work with anything to become good at anything.

CTV: When you were out there, was there anything you felt you were good at?

MOORE: No. I've tried everything, I skated for years and never got good at it, played guitar and bass for years, never got good at that. So, I mean, I was a failure at everything.

CTV: Who's Lily?

MOORE: Just a friend of mine, met her about a year ago, and just a good friend.

CTV: How did you meet?

MOORE: She found me on the Internet somehow and wrote to me. Things went from there.

CTV: When did you get that tattoo [the one on your knuckles that says Lily]?

MOORE: The day after I got my execution date, so it was six months ago.

CTV: What made you decide to get it?

MOORE: I just, it's funny because even when I got it, she and I were having an argument and she hadn't even written to me in six weeks when I got it, so I don't know. I felt it, I needed it. I wanted it there and I felt good about having it there, even though she and I were at a point where we might not even talk to each other again, but I felt, I felt I'd show her that I was thinking about her anyhow and put it on there.

CTV: Are you talking again?

MOORE: Yes, I saw her yesterday and the day before. She's down here visiting. [Note: The couple filed marriage papers two days after this interview.]

CTV: Is there any particular moment in your life that you consider a turning point?

MOORE: I guess this case, from getting locked up. When this case happened, I had zero foresight. All I could think about was today and tomorrow and not much beyond that. Had I had maturity and foresight back then, then none of this would have never happened ... it took getting locked up and sent to prison before I realized all this, so I mean, I guess that would be the only turning point I ever had.

CTV: Have you gotten any treatment since you've been in here?

MOORE: No.

CTV: Have you asked for any?

MOORE: No.

CTV: Do you feel you need any?

MOORE: No. I'm not that crazy.

CTV: I'd like to ask you some questions about your case. Why were you out robbing that evening? What did you want the money for?

MOORE: Rent and food, I guess, that's what it boiled down to ... I was living with a girlfriend and we were sharing rent on an apartment. She was paying for most of it. I was having to rob and steal all the time to catch up with her.

CTV: Why did you return to the scene of the crime?

MOORE: Stuff was left behind, a couple of firearms I think, odds and ends, but I figured we could jump in and back out, get in and get out and run away with the loot. We already had most of it but I guess we left about 10 percent of it behind. I made the decision for us to go back and get it.

CTV: Why did you kill the officer?

MOORE: The driver is out in the car. He's ducked down in the seat, and me and my buddy were in the house and the driver yelled, "There's a car coming." We dropped what we had and ran out to the car. The car coming down the road was a personal car, it wasn't a police car. It blocked us in the driveway. He got in the driveway pretty hard and quick and jumped out ... had the driver door open and pointed his weapon at our windshield. All I could see was his face and his pistol, his weapon... It wasn't until a few months ago that I started thinking about the actual situation, the timing of the situation, and trying to see some significance in it. From the time he jumped out his driver door and leveled his weapon at us to the time I shot at him, it was less then 10 seconds. I bring that up now as being significant because I didn't have time to think things through and understand what was happening fully.

CTV: Did you think he was a police officer?

MOORE: I felt he was a police officer. And in my trial, they made a deal about him being in uniform and he was, but he also had a black jacket covering his top half. You had to understand that this neighborhood was pitch-black. I felt he was a police officer because of the authority he was projecting: a bad-ass motherfucker taking charge of situation and shit. So I felt he weren't no ordinary man.

CTV: Were you afraid of him?

MOORE: Not so much about getting killed, but just didn't want him to alter my path that I was trying to take. I'm trying to get somewhere. I can't call it survival or, like, self-defense, but I was scared and I wasn't about to let anybody alter my path if I could find a way out of it and that's what ultimately got him killed.

CTV: What's your biggest regret?

MOORE: Taking my firearm out with me that night. I did put myself in that position. I am responsible for his death, but the only thing that I can argue is I had two co-defendants. One of them was found guilty of capital murder by law of parties ... and I think that's wrong because he wasn't an active participant in killing anybody and neither one of them knew full well whether or not I had a pistol with me that night anyhow ... The guy in the backseat had just turned 17 and the driver, Paul, uh, Pete, was about 17 and maybe 5 months.

CTV: What do you think should happen to them?

MOORE: The driver, Pete, got organized crime and a 25-year sentence and for his part in this case. I guess that's probably fair because the main result was a man getting killed and had he not gotten killed, I think a lesser sentence would've been better, but a man did get killed, so there's something more to it. And for Paul, he should've gotten same convictions, same sentence as Pete and was headed in that direction, but when we went to the county jail and they had a hard time indicting ... About a year into our being locked up, they were able to return a capital murder indictment on him and this was based on new evidence from two people who were so-called witnesses ...

CTV: Which would you prefer, a death sentence or life without parole?

MOORE: I'd take life.

CTV: Why?

MOORE: Shit, you learn to deal with it, you learn to live. I enjoy life in here too. For some people it's bad. It depends on what kind of case you have and stuff like that.

CTV: Are you religious?

MOORE: No.

CTV: What do you think will happen to you after you die?

MOORE: Get cremated.

CTV: Is there an afterlife?

MOORE: I'll find out when I get there.

CTV: With less than a week until your scheduled execution, are you ready to die?

MOORE: Yeah, I can take it or leave it, I don't want to die, but it's what the state wants.

CTV: Are you afraid of death?

MOORE: No, no. It's going to happen eventually anyhow.

CTV: Is there anything you want people to know about you that they may not know already?

MOORE: Well, just about Paul Cameron. He is not guilty of capital murder. He should get some kind of relief, hopefully.

CTV: And what about you?

MOORE: No, everybody knows me, they know me. I don't hide anything. Everybody knows definitely how I feel.

CTV: What do you want to be remembered for?

MOORE: Nothing. I mean, I haven't accomplished anything. I wish I had, now looking in hindsight, I wish I had done something to get my name out there, but I didn't, so here I am now, haven't done anything with my life and now I'm going to get killed.

CTV: Have you thought about what your last words might be?

MOORE: It would be about Paul. I'm trying to help him in any way I can because capital murder, life sentence, 40-year minimum, for a case he wasn't all the way down with in the first place is just wrong

Moore v. State, 999 S.W.3d 385 (Tex.Cr.App. 1999) (Direct Appeal).

Defendant was convicted in the District Court, Bexar County, Sharon Macrae, J., of capital murder and sentenced to death. Defendant appealed. The Court of Criminal Appeals, Keller, J., held that: (1) defense counsel's comments on defendant's courtroom outbursts and unspecified allegations of difficult communication with defendant were insufficient to require competency hearing; (2) defendant's outbursts were timely, topical, and logical, and thus not probative of his competence to stand trial; (3) defendant's decision to proceed pro se was knowingly and intelligently made and voluntary, and thus was not evidence of incompetence; (4) failure to supplement appellate record precluded appellate review of court reporter's failure to record bench conferences; (5) visiting judge assigned to preside over weekly general assembly of veniremen was not trial judge's “designee,” but had power to entertain prospective juror's excuses and exemptions; (6) defendant's oral statement about location of compound bow, which law enforcement did even know existed at time, rendered entire oral confession admissible; and (7) error in admitting defendant's hand drawn diagram of crime scene as an oral statement was harmless. Affirmed. Mansfield, J., concurred in part and joined opinion of Court in part; Meyers and Johnson, JJ., concurred in result.

KELLER, J., delivered the opinion of the court, in which McCORMICK, P.J. and PRICE, HOLLAND, WOMACK, and KEASLER, J.J., joined.

Appellant was convicted of the offense of capital murder, committed January 15, 1995. See Tex. Penal Code Ann. §§ 19.03(a)(1) and (2). FN1 Pursuant to the jury's answers to the special issues set forth in Texas Code of Criminal Procedure Article 37.071 §§ 2(b) and 2(e), the trial judge sentenced appellant to death. Article 37.071 § 2(g).FN2 Direct appeal to this Court is automatic. Article 37.071 § 2(h). Thirty-seven points of error are advanced by the appellant on direct appeal. We will affirm.

FN1. Under Tex. Penal Code Ann. § 19.03(a)(1) a person commits capital murder if the person murders a peace officer or fireman who is acting in the lawful discharge of an official duty and who the person knows is a peace officer or fireman. Under Tex. Penal Code Ann. § 19.03(a)(2) a person commits capital murder if the person intentionally commits the murder in the course of committing burglary.

Appellant was charged in a two paragraph indictment with committing the capital murder of Fabian Dominguez. The first paragraph alleged murder of a peace officer acting in the lawful discharge of an official duty. The second paragraph alleged murder in the course of burglary of a habitation.

Statement of Facts

On January 15, 1995, at approximately 5:00 a.m., San Antonio police officer Fabian Dominguez went off duty and began driving home in his personal vehicle. Officer Dominguez lived in San Antonio with his wife and infant twin daughters. Officer Dominguez was a few blocks from home when he noticed suspicious activity at the residence of William Braden. Based on what Officer Dominguez observed, he took action to investigate what appeared to be a burglary in progress. When he pulled into the Braden driveway, blocking in the suspects' vehicle, Paul Cameron, Pete Dowdle, and appellant were concluding their second trip to burglarize the Braden home.

In his voluntary written statement to Detective James Holguin, appellant described the sequence of events leading up to the murder of Officer Dominguez. For some dumb reason we decided to go back to the house on Country Flower. We went in Pete's grandmother's car···· Pete drove. I was in the front passenger side of the car and Paul was in the backseat. Pete backed the car into the driveway. Pete stayed out in the car. We had accidently left the front door wide open the first time. Me and Paul went in through the front door. We didn't have any problem with the dog. All three of us were wearing gloves again. We had left some guns and a compound bow were left (sic) from the first time. We got those things. Me and Paul decided to split form (sic) the inside. We walked outside and we saw a car passing by. The car stopped and I saw the reverse lights come on. We all got into the car. Pete was behind the wheel. I was in the front passenger seat and Paul was in the backseat. The car pulled into the driveway and pretty much blocked us in. The police officer got out of the car and had his gun pointing at Pete. I could see that this guy was wearing a police uniform. The officer said get out of the car now. I had my window rolled down. The officer kept repeating “get out of the car”. ···· I kept telling Pete let's split but he would not do it. By the time the officer walked up to the car and had the gun pointed at my head. (sic) The officer was on the passenger side of Pete's car. The officer told Pete to give him the car keys and Pete gave it to him. I scooted the officer's pistol away and I pulled out my gun and shot at him. I believe I shot at him three times. The officer fell to the ground. I already had my gun in my hand when the officer walked up. My gun is a .25 caliber automatic. It's plated and it's a Lorcin brand. After I shot the officer his gun fell into the front rear seat of Pete's car. I got out of the car and I got the car keys and gave them to Pete. I got the officer's gun and shot the officer three times in the head. I got back in the car and Pete split. Paul was in the backseat during the whole time. Pete didn't want to get into trouble after I shot the cop so he drove away.

Neighbors across the street heard gunfire coming from the Braden home. Upon receiving a 911 call, police and emergency personnel were immediately dispatched. Officer Dominguez was dead by the time firemen arrived on the scene. The coroner later determined that Officer Dominguez died from multiple gunshot wounds to the head. Ballistics established that the wounds were inflicted by one shot from appellant's .25 caliber handgun, and three shots from Officer Dominguez's .40 caliber service weapon.

After leaving the scene of the crime, appellant, Cameron, Dowdle, and appellant's girlfriend, Meredith Nichols, traveled to a plot of land near Pipe Creek, Texas, where they disposed of both murder weapons and the items stolen from the Braden residence.

The following day appellant was developed as a suspect in the burglary. He was subsequently located and seen driving a vehicle that belonged to Nichols. Nichols was a passenger in the vehicle. While under police surveillance, appellant committed numerous traffic violations. When police officers signaled him to pull to the side of the road, a high speed chase ensued. Twenty miles later, appellant and Nichols were captured after appellant careened to the side of the road. After a brief struggle, San Antonio police officers arrested appellant and took him into custody. In his voluntary statement to Detective Holguin appellant explained his flight from authorities, stating, “I figured pretty much that the cops knew that I was the one that shot the cop.”

* * *

VI. Admission of Appellant's Oral Statements

Points of error five and six assert that the trial court erred in admitting into evidence an oral statement made by appellant subsequent to arrest. Article 38.22 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure in pertinent part provides: Sec. 3. (a) No oral or sign language statement of an accused made as a result of custodial interrogation shall be admissible against the accused in a criminal proceeding unless: (c) Subsection (a) of this section shall not apply to any statement which contains assertions of facts or circumstances that are found to be true and which conduce to establish the guilt of the accused, such as the finding of secreted or stolen property or the instrument with which he states the offense was committed.

As a general rule, under section 3(a), oral confessions are not admissible. However, as an exception set out in section 3(c), oral statements asserting facts or circumstances establishing the guilt of the accused are admissible if at the time they were made they contained assertions unknown by law enforcement but later corroborated. Dansby v. State, 931 S.W.2d 297 (Tex.Crim.App.1996); Gunter v. State, 858 S.W.2d 430 (Tex.Crim.App.1993). Such oral statements need only circumstantially demonstrate the defendant's guilt. Port v. State, 791 S.W.2d 103 (Tex.Crim.App.1990). Furthermore, if such an oral statement contains even a single assertion of fact found to be true and conducive to establishing the defendant's guilt, then the statement is admissible in its entirety. Marini v. State, 593 S.W.2d 709 (Tex.Crim.App.1980).

Appellant asserts that the police knew all of the facts supplied by him in his confession prior to the making of that statement.FN13 Accordingly, he claims the State has failed to satisfy the exception of Article 38.22 § 3(c). We disagree.

While the trial court concluded that appellant made various oral statements which conduce to establish his guilt, the most significant is his statement concerning a compound bow taken in the burglary. In describing how he and his accomplices disposed of items related to the burglary and murder, appellant stated, “All that was in the car was a compound bow and binoculars, my .25 caliber pistol, the officer's pistol, and a sawed-off shotgun.”

According to Detective McCourt, who sat in on appellant's interview, at one point Detective Holguin left the room and McCourt asked appellant something about the bow. Though all of the other items related to the burglary and murder had been discovered prior to appellant's statement, no compound bow had been recovered. During his discussion with McCourt, appellant said that the bow would not be found at the same place he and his accomplices had put the other stolen property. Appellant told McCourt that he had tired of carrying the various items and had thrown the bow in another direction from the general vicinity of the other stolen property. At the time appellant revealed this information, neither law enforcement nor William Braden, the owner of the bow, were aware that the compound bow had been stolen from the scene of the crime. It was not until the next day that the information about this bow was confirmed by its discovery in Bandera County near but not in the same location as the other stolen property which had been discovered the previous evening. Appellant's statements about the compound bow contained assertions of fact unknown by law enforcement but later corroborated. In accord with our holding in Marini, appellant's oral statement about the compound bow contains facts which were found to be true and were conducive to establishing guilt. Hence his entire oral statement was properly deemed admissible under Article 38.22. Point of error five is overruled.

With the oral statement being admissible, the final issue for consideration is the manner in which it was put into evidence. Unable to recollect appellant's complete statement, Detective Holguin was allowed by the trial court to read appellant's statement as a past recollection recorded. Tex. Rule Crim. Evid. 803(5). Appellant argues that the statement was hearsay and should not have been admitted as a recollection recorded because Holguin lacked the personal knowledge required by Rule 803(5). We disagree with appellant's assertion that the reading of the transcribed oral statement constituted hearsay. By signing Detective Holguin's transcription of the oral statement, appellant manifested an adoption or belief in its truth. Accordingly, it was an admission by a party opponent, and not hearsay. See Tex.R.Crim. Evid. 801(e)(2)(B). Point of error six is overruled.

* * *

The judgment of the trial court is AFFIRMED.

Moore v. Dretke, 182 Fed.Appx. 329 (5th Cir. 2006) (Habeas).

Background: After murder conviction and death sentence were upheld on appeal and in subsequent state court habeas proceedings, petitioner filed federal habeas petition, alleging ineffective assistance of counsel during his trial. The United States District Court for the Western District of Texas, Rodriguez, J., 2005 WL 705340, denied habeas petition, and petitioner moved for certificate of appealability on issue of ineffective assistance.

Holding: The Court of Appeals held that, after state court determined that pretrial competency hearing was not necessary, failure of petitioner's defense attorneys to produce testimony of defense experts on question of his competency to stand trial did not amount to ineffective assistance. Motion for COA denied.

Petitioner Johnathan Bryant Moore was convicted in Texas state court of capital murder and sentenced to death. After exhausting all available state remedies, Moore filed a petition for federal habeas corpus relief in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas, claiming that he received ineffective assistance of counsel in violation of the Sixth Amendment and that he was sentenced to death in violation of the Seventh Amendment. The district court denied the petition and declined to issue a certificate of appealability (COA). Moore now requests that this Court grant a COA as to his ineffective assistance of counsel claim pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2253(c)(2). For the reasons stated below, we deny Moore's Application for a Certificate of Appealability.

I. Background

In October 1996, Petitioner Moore was convicted of capital murder for the shooting of San Antonio police officer Fabian Dominguez and sentenced to death. The facts of the murder, as summarized by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (TCCA) on direct appeal, are as follows:

On January 15, 1995, at approximately 5:00 a.m., San Antonio police officer Fabian Dominguez went off duty and began driving home in his personal vehicle. Officer Dominguez lived in San Antonio with his wife and infant twin daughters. Officer Dominguez was a few blocks from home when he noticed suspicious activity at the residence of William Braden. Based on what Officer Dominguez observed, he took action to investigate what appeared to be a burglary in progress. When he pulled into the Braden driveway, blocking in the suspects' vehicle, Paul Cameron, Pete Dowdle, and [Moore] were concluding their second trip to burglarize the Braden home.

In his voluntary written statement to Detective James Holguin, [Moore] described the sequence of events leading up to the murder of Officer Dominguez. For some dumb reason we decided to go back to the house on Country Flower. We went in Pete's grandmother's car···· Pete drove. I was in the front passenger side of the car and Paul was in the backseat. Pete backed the car into the driveway. Pete stayed out in the car. We had accidently left the front door wide open the first time. Me and Paul went in through the front door. We didn't have any problem with the dog. All three of us were wearing gloves again. We had left some guns and a compound bow were left (sic) from the first time. We got those things. Me and Paul decided to split form (sic) the inside. We walked outside and we saw a car passing by. The car stopped and I saw the reverse lights come on. We all got into the car. Pete was behind the wheel. I was in the front passenger seat and Paul was in the backseat. The car pulled into the driveway and pretty much blocked us in. The police officer got out of the car and had his gun pointing at Pete. I could see that this guy was wearing a police uniform. The officer said get out of the car now. I had my window rolled down. The officer kept repeating “get out of the car”···· I kept telling Pete let's split but he would not do it. By the time the officer walked up to the car and had the gun pointed at my head. (sic) The officer was on the passenger side of Pete's car. The officer told Pete to give him the car keys and Pete gave it to him. I scooted the officer's pistol away and I pulled out my gun and shot at him. I believe I shot at him three times. The officer fell to the ground. I already had my gun in my hand when the officer walked up. My gun is a .25 caliber automatic. It's plated and it's a Lorcin brand. After I shot the officer his gun fell into the front rear seat of Pete's car. I got out of the car and I got the car keys and gave them to Pete. I got the officer's gun and shot the officer three times in the head. I got back in the car and Pete split. Paul was in the backseat during the whole time. Pete didn't want to get into trouble after I shot the cop so he drove away.

Neighbors across the street heard gunfire coming from the Braden home. Upon receiving a 911 call, police and emergency personnel were immediately dispatched. Officer Dominguez was dead by the time firemen arrived on the scene. The coroner later determined that Officer Dominguez died from multiple gunshot wounds to the head. Ballistics established that the wounds were inflicted by one shot from [Moore]'s .25 caliber handgun, and three shots from Officer Dominguez's .40 caliber service weapon.

After leaving the scene of the crime, [Moore], Cameron, Dowdle, and [Moore]'s girlfriend, Meredith Nichols, traveled to a plot of land near Pipe Creek, Texas, where they disposed of both murder weapons and the items stolen from the Braden residence.

The following day [Moore] was developed as a suspect in the burglary. He was subsequently located and seen driving a vehicle that belonged to Nichols. Nichols was a passenger in the vehicle. While under police surveillance, [Moore] committed numerous traffic violations. When police officers signaled him to pull to the side of the road, a high speed chase ensued. Twenty miles later, [Moore] and Nichols were captured after [Moore] careened to the side of the road. After a brief struggle, San Antonio police officers arrested [Moore] and took him into custody. In his voluntary statement to Detective Holguin [Moore] explained his flight from authorities, stating, “I figured pretty much that the cops knew that I was the one that shot the cop.” Moore v. State, 999 S.W.2d 385, 391-92 (Tex.Crim.App.1999).

On direct appeal to the TCCA, Moore raised thirty-seven points of error. The TCCA found no error and affirmed his conviction and sentence. Moore's petition for writ of certiorari to the U.S. Supreme Court was denied. Moore subsequently filed an application with the Texas trial court for a writ of habeas corpus, raising eighteen grounds for habeas relief. After holding an evidentiary hearing, the convicting court entered findings of fact and conclusions of law recommending that Moore's application be denied. The TCCA adopted the convicting court's recommended factual findings and legal conclusions and denied Moore's request for habeas relief.

Moore subsequently filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus in federal district court. In his petition, he raised only two grounds for relief, both of which were previously raised before the state habeas court: (1) that he received ineffective assistance of counsel in violation of the Sixth Amendment; and (2) that he was sentenced to death in violation of the Seventh Amendment. The district court denied relief and declined to issue a COA. Moore thereafter filed an Application for a Certificate of Appealability with this Court. He only seeks a COA as to the ineffective assistance of counsel claim.

II. Facts Relating to Ineffective Assistance of Counsel Claim

Moore's central claim is that he received ineffective assistance of counsel at trial because his court-appointed attorneys failed to present sufficient available evidence-namely, the testimony of defense experts-to the trial judge to support their request that a jury be empaneled to determine whether Moore was competent to stand trial. The facts relevant to this claim are drawn from the pretrial proceedings, the guilt-innocence and punishment phases of trial, and the post-conviction proceedings.FN2 FN2. We summarize the well-stated facts presented in the district court's order, Moore v. Dretke, No. SA-02-CA-0579 (W.D.Tex. Mar. 22, 2005), which reflect the state habeas court's findings of fact.

Pretrial, at a suppression hearing, Moore's court-appointed counsel, John Convery and Ronald Guyer, made an ex parte application to the trial court for an examination of Moore on his competency to stand trial. Counsel asked the court to consider, in deciding whether to hold a competency hearing, inappropriate outbursts and comments made by Moore during the suppression hearing, Moore's history of mental illness, including hospitalization and treatment at a mental health facility, and counsel's general impression that Moore was not competent and did not understand the proceedings against him. The court found insufficient evidence to necessitate a competency hearing, but, “in an abundance of caution,” appointed Dr. Michael Arambula to examine Moore and give the court an opinion as to Moore's competency.

Dr. Arambula examined Moore, but he never gave the trial court an opinion as to Moore's competency; rather, he and his colleague, Dr. Margot Zuelzer, who also examined Moore, made reports only to Moore's counsel. While equivocal, they both reported that they felt Moore was competent to stand trial. The only report on competency submitted to the trial court was one prepared by Dr. John Sparks, a psychiatrist appointed for the State to evaluate Moore's competency, sanity, and future dangerousness after Moore's counsel notified the court during voir dire of their intention to raise insanity as a defense. Dr. Sparks stated in his report that he thought Moore was competent to stand trial.

When trial commenced, Moore tried to discharge his attorneys, expressing concern about being represented by lawyers who were “paid for by the State.” The trial court discussed the inadvisability of self-representation with Moore and gave him time to meet with his attorneys over lunch to reassess whether he wanted to discharge them. After lunch, Moore indicated that he would proceed with Guyer and Convery as counsel. Moore's competency was not raised again at this time.

Moore's chief defense at trial was insanity. His counsel put Doctors Arambula and Zuelzer on the stand to testify as to Moore's mental state at the time of the offense. They both testified that Moore suffered from schizoaffective disorder and that his illness was severe, rendering him insane at the time he shot Officer Dominguez. Neither doctor was asked on the stand about Moore's competence to stand trial. The State called Dr. Sparks and another doctor-who evaluated detainees, including Moore, at the Bexar County Jail-on rebuttal, and they testified that Moore suffered from dysthymia, a minor depression, and possibly a borderline personality disorder and that his illness did not render him legally insane at the time of the shooting. Neither doctor called by the State was asked on the stand about Moore's competence to stand trial. At the conclusion of the guilt-innocence phase of the trial, the jury rejected Moore's insanity defense and found Moore guilty of capital murder.

At the punishment phase of trial, Moore again tried to discharge his attorneys. This time, Moore was not persuaded by the court's admonition regarding the advisability of self-representation; he insisted on representing himself. After inquiring into Moore's ability to choose intelligently and voluntarily to self-represent, the trial court warned Moore about the dangers of self-representation, noted that the record reflected that he was mentally competent, and permitted him to proceed without counsel. Guyer and Convery, whom the court appointed as standby counsel in the event that Moore demonstrated an inability to represent himself, moved at this time for a competency hearing under Texas Code of Criminal Procedure article 46.02. FN3 However, they did not present any new evidence regarding competence, relying instead on the insanity evidence presented at trial and Moore's insistence on representing himself. Denying Guyer and Convery's motion, the trial court emphasized that Dr. Sparks had filed a report with the court stating his opinion that Moore was competent to stand trial and that a desire to self-represent did not in and of itself suggest that Moore was incompetent. Later that day, Guyer and Convery renewed their request for a competency hearing. The trial court again denied their request, stating that it had heard no evidence suggesting that Moore was incompetent.FN4

FN3. Article 46.02 provided at that time, If during the trial evidence of the defendant's incompetency is brought to the attention of the court from any source, the court must conduct a hearing out of the presence of the jury to determine whether or not there is evidence to support a finding of incompetency to stand trial. TEX. CODE CRIM. PROC. art. 46.02, § 2(b) (West 1996). FN4. The record shows that Guyer informed the trial court that “[counsel] might present Dr. Arambula on this matter,” but after a brief recess advised the court that “[counsel is] not prepared to go forward on that at this moment.”

Moore represented himself during the first two days of the punishment phase of trial, asking relevant questions and obtaining favorable rulings on objections. On the second day, Moore decided to discontinue self-representation, and Guyer and Convery were reinstated as counsel. Counsel then moved for a mistrial, based in part on evidence of Moore's competency. The motion was denied. Counsel continued to represent Moore throughout the remainder of his trial. On October 25, 1996, Moore was sentenced to death.

On appeal to the TCCA, Moore's conviction and sentence were upheld. Addressing one of many points of error, the TCCA found that Moore was competent to stand trial and that the combination of Moore's courtroom outbursts, his mental health history, his self-representation, and nonspecific concerns about his ability to communicate with his attorneys did not raise a bona fide doubt as to his competency such that a competency hearing was warranted in the court below. The Supreme Court denied Moore's petition for writ of certiorari.