Executed September 25, 2013 10:39 a.m. by Lethal Injection in Ohio

26th murderer executed in U.S. in 2013

1346th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

3rd murderer executed in Ohio in 2013

52nd murderer executed in Ohio since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(26) |

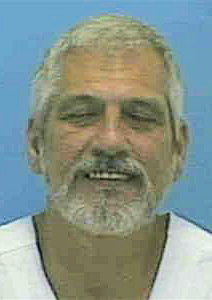

Harry Mitts Jr. W / M / 38 - 61 |

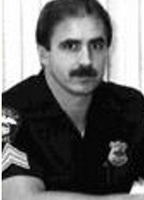

John A. Bryant B / M / 28 Dennis Glivar OFFICER W / M / 40 |

.44 handgun |

Citations:

State v. Mitts, 81 Ohio St. 3d 223, 690 N.E.2d 522 (Ohio 1998). (Direct Appeal)

Mitts v. Bagley, 620 F.3d 650 (6th Cir. 2010). (Habeas)

Bobby v. Mitts, 131 S. Ct. 1762 (U.S. 2011). (Habeas Appeal to U.S. Supeme Court - Reversed)

Final/Special Meal:

Steak smothered with mushrooms and onions, Caesar salad with ranch dressing, Italian bread, fries, peach pie, butter pecan ice cream and Dr. Pepper.

Final Words:

Mitts used his last words to ask for forgiveness and encourage the victims' families to find salvation in Jesus Christ. "I'm so sorry for taking your loved ones' lives. I had no business doing what I did and I've been carrying that burden with me for 19 years. Please don't carry that hatred for me with you in your hearts."

Internet Sources:

Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction

Number: CCI#:

Date of Birth: 6/18/1952

Gender: Male Race: White

Date of Offense:

County of Conviction: Cuyahoga

Institution: Chillicothe Correctional Institution

Executed: 09/25/2013

On September 25, 2013, Harry Mitts, Jr. was executed for the 1994 aggravated murders of John Bryant and Sgt. Dennis Glivar.

"Mitts executed by lethal injection this morning at Lucasville, following 20 years in prison." (September 25, 2013)

LUCASVILLE, Ohio – Garfield Heights killer Harry Mitts Jr. was executed Wednesday after spending nearly two decades on death row for gunning down his neighbor and a police officer. A lethal injection stopped Mitts' heart at 10:39 a.m.

Mitts, 61, was sentenced to death in November 1994 after a full-bore firefight at his apartment complex that left neighbor John Bryant and Garfield Heights Police Sgt. Dennis Glivar dead.

Mitts used his last words to ask for forgiveness and encourage the victims' families to find salvation in Jesus Christ. "I'm so sorry for taking your loved ones' lives," Mitts said with tears in his eyes. "I had no business doing what I did and I've been carrying that burden with me for 19 years. "Please don't carry that hatred for me with you in your hearts."

Mitts' lethal injection lasted nearly 35 minutes. At 10:05 a.m., corrections officers walked a calm Mitts into the death chamber, where he was strapped to a steel bed and hooked up to lines that would deliver deadly chemicals. After his final words, Mitts stared at the ceiling while authorities in another room delivered the injection. Mitts closed his eyes and took increasingly labored breaths. About a minute later, he began to snore. The snoring soon stopped and Mitts' breathing gradually slowed. His face turned blue by the time he took his last peaceful gasp.

Mitts is the last person to be put to death in Ohio using the drug pentobarbital. The state's supply of pentobarbital was expected to run out with Mitts' executions today. Department of Rehabilitation and Correction will announce by Oct. 4 how it will respond, according to spokeswoman Ricky Seyfang.

Witnesses, including retired Garfield Heights Police Lt.Tom Kaiser, who was Glivar's partner at the time and was shot twice during Mitts' storm of gunfire, joined others in watching the condemned murderer die at the Southern Ohio Correctional Facility. Victim witnesses included Bryant's sister, Glivar's widow and mother, and Garfield Heights Police Chief Robert Sackett. "I know its wrong, but I still have hatred for him," said Bryant's sister Johnnal after the execution. Glivar's widow Debbie said she would never forgive Mitts. Mitts' friend Gary Hopkins joined ministers Edward Jenkins and Lucian Piaskowiak on the inmate's side of the witness room. All of the witnesses watched in silence as Mitts slipped away.

Mitts began his hours-long rampage on the evening of Aug. 14, 1994 by firing a laser-sighted round into Bryant's chest as Bryant and his girlfriend were returning home from grocery shopping. Bryant, who was black, and his girlfriend, who was white, were walking from the parking lot to their apartment when Mitts approached the couple. He raised his gun, uttered racial slurs and shot 28-year-old Bryant point blank. Against Mitts' orders, neighbors carried Bryant to a second-floor apartment and waited for help to arrive. Mitts then walked away, randomly firing his weapon, and prepared for the imminent police response. Mitts hoped for a suicide by cop, according to Ohio Parole Board documents. Mitts fired eight to 10 rounds at the first patrol car to approach the complex and then fled to his first-floor apartment. Glivar and Kaiser arrived soon after and located Bryant, who bled out before they arrived. The officers returned downstairs to ensure the building was safe for paramedics to enter.

That is when Mitts, who clenched a .44 Magnum in one fist and a 9 mm pistol in the other, sprung open his apartment door and let loose a volley of gunfire. Glivar, 44, was shot seven times. Bullets ripped through his heart, lung, liver, kidney and stomach. He collapsed near the door, dropped his shotgun and died within minutes. Kaiser was shot in the chest and hand but managed to force Mitts to retreat by firing in the killer's direction. Kaiser then took cover upstairs and kept watch on Mitts' apartment.

"We didn't even know he lived there," Kaiser said Tuesday. "He was just waiting for us. Maybe he was looking through his peephole. He took us by surprise." Kaiser tried to talk Mitts into surrendering. Mitts refused. "The only way we're going to end this is if you kill me," Mitts shouted, according to clemency documents. "You have to come down. You have to do your job and you have to kill me."

Minutes later, Maple Heights Police Officer John Mackey arrived at the complex and helped Kaiser rescue tenants upstairs by guiding them down a ladder propped against a back window. Mackey and Kaiser then took positions outside Mitts apartment while the gunman fired sporadic shots using Glivar's dropped shotgun and weapons from his home arsenal. At one point, Mitts was able to pick out Mackey's location by the sound of the officer's voice carrying through the hallway. Mitts fired through a wall and hit Mackey. The bloody gun battle ended hours later when a SWAT team shot tear gas into Mitts' apartment and subdued the wounded triggerman.

Mitts was charged with the aggravated murders of Bryant and Glivar, and the attempted murders of Kaiser and Mackey. Three months later, the man with no previous criminal record was sentenced to death.

Authorities found thousands of rounds of ammunition in Mitts' home and a bumper sticker that read: "Gun control means hitting what you aim at." The Ohio Parole Board said Mitts' deadly confrontation is "clearly among the worst of the worst capital cases."

Mitts began to tailspin in the weeks leading to the massacre. He began stalking his ex wife and her new husband, and admitted he thought about assassinating the man. Prosecutors argued Mitts' attack was racially motivated, but defense attorneys contended Mitts killed Bryant only to lure police.

Last week, Gov. John Kasich denied Mitts clemency, siding with the parole board's unanimous recommendation to carry out the death sentence. Mitts told the parole board in August he found God while incarcerated at the Cuyahoga County Jail and looked forward to living "in perpetuity with Jesus Christ" after his execution.

"Killer who used racial slurs executed," by Julie Carr Smyth. (Associated Press Sept 26, 2013 5:43 AM)

LUCASVILLE, Ohio — A white gunman who spewed racial slurs before fatally shooting a black man and a police officer in a 1994 rampage that prosecutors called one of the worst Ohio has seen was executed today with the state’s last use of its execution drug. Harry Mitts Jr. asked the families of his victims to forgive him, saying he had carried the burden of his crimes with him for 19 years. “I had no business doing what I did,” he said in a last statement to six witnesses representing his victims. Two clergy members and a friend were also in attendance. Mitts Jr., 61, was pronounced dead at 10:39 a.m. by lethal injection of the powerful sedative pentobarbital at the state prison in Lucasville after years of acknowledging his crimes and repenting. The state’s supply of pentobarbital is expiring, and a new execution method will be announced later.

Mitts was convicted of aggravated murder and attempted murder in the August 1994 rampage against random neighbors and responding police officers at his apartment complex in a Cleveland suburb. Wielding a gun with a laser sight and later other weapons, Mitts first shouted racial epithets and killed a neighbor’s black boyfriend, John Bryant, and then shot and killed white Garfield Heights police Sgt. Dennis Glivar as he responded to the scene. Mitts also shot and wounded two other police officers.

The Ohio Parole Board and Republican Gov. John Kasich had denied Mitts’ pleas for mercy. Mitts, at his clemency hearing, had pointed to a virtually clean record before and after the day of the shootings and said he had found God in prison. After his conviction, he spoke of receiving a Bible from Glivar’s mother and sister and a letter expressing their forgiveness and urging him to seek repentance. Mitts told the Ohio Parole Board he had drunk heavily because he was distraught over his divorce and had likely shot Bryant to draw police to his home in hopes they would shoot and kill him. He said he wasn’t a racist and didn’t remember directing racial slurs at Bryant before shooting him. He said he couldn’t say why he didn’t shoot two white neighbors he encountered ahead of Bryant.

Prosecutors argued that, with the murders, multiple shootings and additional death threats carried out that day, Mitts “exhibited complete disregard for the lives of officers and innocent bystanders at the scene.” “That further tragedy did not result from the bedlam that Mitts created on August 14, 1994, is in many respects a miracle,” a clemency report said.

With Ohio’s supply of pentobarbital expiring, the Department of Rehabilitation and Correction has said it expects to announce its new execution method by Oct. 4. Pentobarbital is no longer available because its manufacturer has put it off limits to states for executions.

"Ohio uses last lethal drug dose to execute convicted murderer," by Kim Palmer. (September 25, 2013 12:24pm EDT)

(Reuters) - Ohio used the state's last available dose of the drug pentobarbital on Wednesday to execute a man described by prosecutors as a racist, who was convicted of killing a neighbor and then a police officer responding to the shooting. Harry Mitts Jr., 61, was pronounced dead at 10:30 a.m. ET (1430 GMT) at the Southern Ohio Correctional facility, a state corrections department official said.

Mitts, who was white, was convicted in 1994 of killing a neighbor, John Bryant, and then shooting to death Ohio police officer Dennis Glivar as he responded to the shooting. Mitts also tried to kill two other police officers. Prosecutors argued that Mitts was a racist who allowed two white people to flee unharmed before he shot Bryant, a black man, and used racial epithets during a standoff with police. Mitts did not contest the evidence against him at trial, instead arguing that he was too intoxicated to form the required intent to kill.

Ohio's supply of pentobarbital expires at the end of September and will no longer be legal for executions. The drug, a barbiturate used to relieve tension and relax patients before surgery, is lethal if given in high doses. Ohio is the latest state forced to find alternate methods after pentobarbital's Danish manufacturer Lundbeck cut off supplies to customers likely to use it for executions, in accordance with Danish law and European human rights law. Ohio has said it plans to have a new execution drug protocol in place in October. The state is next scheduled to execute inmate Ronald Phillips on November 14.

Mitts was the 26th person executed in the United States so far in 2013 and the third in Ohio, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

"Kasich: No mercy for condemned Ohio killer of Two," by Andrew Welsh-Huggins. (AP 09/18/13, 4:01 PM EDT)

COLUMBUS, Ohio (AP) — Gov. John Kasich on Wednesday rejected mercy for a condemned killer of two men, likely ensuring the death row inmate’s execution will proceed next month. Harry Mitts Jr. is scheduled to die by injection on Sept. 25 for killing the men, including a suburban Cleveland police officer, during a 1994 outburst at an apartment. His attorney previously said no other appeals were planned.

As is his practice in death penalty cases, Kasich didn’t explain his reasoning except to note the Ohio Parole Board unanimously recommended against mercy on Aug. 27.

Mitts uttered racial slurs before shooting his first victim, John Bryant, who was black, according to court records. He fired on two police officers as they approached his apartment where he’d taken refuge, wounding one and killing the second, Garfield Heights Sgt. Dennis Glivar. At trial, Mitts’ attorney argued that Mitts suffered an alcoholic blackout that night and didn’t know what he was doing. But the lawyer handling Mitts’ appeals and clemency request says there was no basis for that defense.

Attorney Jeff Kelleher says Mitts’ original lawyer missed the chance to tell the full story: that Mitts was depressed and caused the disturbance in hopes of committing suicide by being shot by police. Mitts knows what he did, takes responsibility, is remorseful and is not and never has been a racist, Kelleher says. “He was an angry, upset person who did something totally unexpected,” Kelleher said in August. “It’s not the person he was before, it’s not the person he’s been since.” A message was left with Kelleher on Wednesday seeking comment on Kasich’s decision. Mitts told parole board members in an early August interview that he would leave the clemency decision up to them. “Mitts indicated that while he could easily cope with a lifetime of imprisonment, he is also prepared to go home to Jesus,” according to the Aug. 27 report by the parole board in recommending against clemency for Mitts.

In its unanimous ruling, the board said it wasn’t convinced Mitts had taken full responsibility for the crime and it rejected his claim that the shooting wasn’t racially motivated. “Given the multiple deaths, the racial animus underlying Bryant’s death, and the law enforcement victims Mitts targeted, Mitts’s case is clearly among the worst of the worst capital cases,” the board said. Even though the original lawyer’s alcoholic blackout tactic didn’t work, it’s unclear what other legal strategy could have produced a different result, the board added.

The state’s supply of its execution drug, pentobarbital, expires at month’s end, and Mitts will be the last person put to death with that drug in Ohio if the execution is carried out. The Department of Rehabilitation and Correction has said it will likely announce its new execution method by Oct. 4.

Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction (Clemency Report)

IN RE: Harry Mitts, Jr., CCI #A305-433

STATE OF OHIO ADULT PAROLE AUTHORITY

Date of Meeting: August 19, 2013

CRIME, CONVICTION: Aggravated Murder with Firearm, Killing an Officer Engaged in his Duties, and Three Mass Murder Specifications, Aggravated Murder with Firearm and Three Mass Murder Specifications, Attempted Murder (two counts) with Firearm and Peace Officer Specifications.

DATE, PLACE OF CRIME: August 14, 1994 in Garfield Heights, Ohio

COUNTY: Cuyahoga

CASE NUMBER: CR313539

VICTIMS: John A. Bryant (deceased), Sgt. Dennis Glivar (deceased), Lt. Tom Kaiser, and Officer John Mackey

INDICTMENT: Count 1: Aggravated Murder with Firearm, Killing an Officer Engaged in his Duties, and Three Mass Murder Specifications Count 2: Aggravated Murder with Firearm and Three Mass Murder Specifications Count 3: Attempted Murder with Firearm and Peace Officer Specifications Count 4: Attempted Murder with Firearm and Peace Officer Specifications

VERDICT: Found Guilty as charged of Counts 1-4 to include all specifications

DATE OF SENTENCE: November 21, 1994

SENTENCE: Counts 1 and 2: DEATH; 3 years actual incarceration (firearm specifications) Counts 3 & 4: 10 – 25 years

ADMITTED TO INSTITUTION: March 3, 1995

JAIL TIME CREDIT: 0 days

TIME SERVED: 18 years, 8 months (does not include jail time credit)

AGE AT ADMISSION: 42 years old

CURRENT AGE: 61 years old

DATE OF BIRTH: June 18, 1952

JUDGES: The Honorable William Aurelius

PROSECUTING ATTORNEY: Stephanie Tubbs Jones

FOREWORD: Clemency proceedings in the case of Harry Mitts Jr., A305-433, were initiated by the Ohio Parole Board pursuant to Sections 2967.03 and 2967.07 of the Ohio Revised Code and Parole Board Policy #105-PBD-01.

On August 6, 2013, Mitts was interviewed via videoconference by the Parole Board at the Chillicothe Correctional Institution. A clemency hearing was then held on August 19, 2013 with eleven (11) members of the Parole Board participating. Arguments in support of and in opposition to clemency were presented at that hearing. The Parole Board considered all of the written submissions, arguments, information disseminated by presenters at the hearing, as well as the judicial decisions, and deliberated upon the propriety of clemency in this case. With eleven (11) members participating, the Board voted eleven (11) to zero (0) to provide an unfavorable recommendation for clemency to the Honorable John R. Kasich, Governor of the State of Ohio.

DETAILS OF THE INSTANT OFFENSE:

The following account of Mitts’s offense was obtained from the Ohio Supreme Court opinion, decided March 11, 1998: On the evening of August 14, 1994, Timothy Rhone helped his sister and brother-in-law, Jeff Walters, move into their apartment. The apartment was on the second floor in the same building where Mitts lived. Between 7:00 and 8:00 p.m., Rhone noticed a man, who he later learned was Mitts, carrying a gun tucked into the small of his back. Fifteen to thirty minutes later, Mitts, who was wearing blue target-shooting earmuffs, confronted Rhone in the hallway. According to Rhone, Mitts pointed a “black and huge” laser-sighted gun at Rhone’s head and “told [him] to get out or [he] was going to fucking die.” When Rhone replied that he did not understand, Mitts said, “I’m not joking, get out now.” Rhone backed away and asked his mother and sister to call 9-1-1 because “a man with a gun [was] threatening to shoot people.”

A short time later, Tracey Griffin and her boyfriend, John Bryant, saw Mitts walking toward them wearing yellow glasses or goggles and carrying a gun. Griffin knew Mitts because they lived in the same apartment complex and their daughters had played together. Mitts’s gun emitted a light, and Griffin saw a dot of red light appear on Bryant’s chest. Mitts said, “Niggers, niggers, I’m just sick and tired of niggers.” Mitts aimed directly at Bryant, Griffin heard a shot, and Bryant fell down. Mitts then walked away, sporadically firing his gun, and later walked back toward Griffin, still firing his weapon, but now in her direction. In the meantime, Walters and Terry Rhone, Timothy’s brother, came out to help Bryant. Mitts aimed his gun and shouted at them, “Leave him there, don’t move.” Walters and Terry Rhone disregarded Mitts’s instruction and carried Bryant into their second-floor apartment.

Around 8:15 p.m., Patrolman John Cermak arrived, and a bystander saw Mitts put a new clip in his gun. Taking “a ready [firing] position,” Mitts fired several shots at Patrolman Cermak, forcing Cermak to drive his car up on a lawn and take cover. Lt. Kaiser and Sergeant Dennis Glivar then arrived. After firing at Patrolman Cermak, Mitts retreated to his first-floor apartment. Patrolman Cermak searched for Mitts, and Lt. Kaiser and Sgt. Glivar went to the apartment building’s second floor, where they found Griffin, Bryant, and the Rhone family. After calling paramedics, Lt. Kaiser and Sgt. Glivar walked down to the first floor.

As Lt. Kaiser and Sgt. Glivar approached Mitts’s apartment, Mitts flung his apartment door open and opened fire with a gun in each hand. Mitts repeatedly shot Sgt. Glivar, forcing him to drop his shotgun, and he shot Lt. Kaiser in the chest and right hand. Lt. Kaiser switched his pistol to his left hand and forced Mitts to retreat by firing three or four times. Lt. Kaiser returned to the Rhone apartment, where he kept a watch on Mitts’s apartment, and radioed for police assistance including the area S.W.A.T. team.

Although wounded, Lt. Kaiser attempted for twenty to thirty minutes to talk Mitts into surrendering, but Mitts replied, “The only way we’re going to end this is if you kill me. You have to come down, you have to do your job and you have to kill me.” Mitts, who had overheard Lt. Kaiser’s S.W.A.T. request over Sgt. Glivar’s abandoned police radio, additionally told Lt. Kaiser, “Go ahead, bring the S.W.A.T. team in, I have thousands of rounds of ammunition. I’ll kill your whole S.W.A.T. team. I’ll kill your whole police department.”

Mitts also threatened Griffin; Mitts told Lt. Kaiser that he was “going to come up and kill that nigger-loving bitch that’s upstairs with you.” Mitts also told Lt. Kaiser that he had been drinking bourbon and was angry because the Grand River Police Chief “stole [his] wife.” Eventually, Patrolman Cermak dragged Sgt. Glivar’s body from the hallway and

Patrolman Cermak and others used a ladder and rescued Rhone’s family and Lt. Kaiser from the upstairs apartment. During the standoff, Mitts called his ex-wife, Janice Salerno, and her husband, Grand River Police Chief Jonathon Salerno. Chief Salerno thought Mitts was joking when Mitts told him that “it’s all over with now, I shot a couple of cops and I killed a fucking nigger.” Chief Salerno, who believed Mitts was drunk, tried to talk him into surrendering, but Mitts refused. Mitts claimed that he had intended to kill both Salerno and his wife, but did not because Mitts’s daughter, Melanie, lived with the Salernos.

Around 8:40 p.m., Maple Heights Police Officer John Mackey responded to the call for police assistance from the city of Garfield Heights. After helping Patrolman Cermak rescue Lt. Kaiser and the Rhone family, Officer Mackey, Sergeant Robert Sackett, and others took tactical positions in the hallway outside Mitts’s apartment. Taking over Lt. Kaiser’s role as a negotiator, Officer Mackey talked with Mitts for over thirty minutes, but Mitts refused to surrender and, at various times, continued to fire shots. Using Sgt. Glivar’s shotgun, Mitts fired twice into a mailbox across the hall, and he also emptied ten pistol shots into that mailbox. According to Officer Mackey, Mitts’s voice appeared calm, and he “never showed any anger or animosity towards” the officers. Around 9:30 p.m., Mitts discerned Officer Mackey’s position in the upstairs apartment from the sound of his voice and fired up the stairway and through a wall, hitting Officer Mackey’s leg with a bullet fragment. Other police officers returned fire and rescued Officer Mackey. Around 1:00 a.m., the S.W.A.T. team injected tear gas into Mitts’s apartment and finally subdued Mitts around 2:00 a.m. Mitts, who had been shot during the standoff, was taken by ambulance to a local hospital, then transported by helicopter to a trauma center at Cleveland’s MetroHealth Medical Center. At 3:43 p.m., a blood sample was drawn from Mitts, and his blood-alcohol level was later determined to be .21 grams per one hundred milliliters.

After arresting Mitts, detectives searched his apartment and found two sets of shooting earmuffs, a yellow pair of glasses customarily used on shooting ranges, a .44 caliber magnum revolver, a 9 mm automatic pistol, a .22 caliber pistol, a laser gun-sight, thousands of rounds of ammunition in boxes, and two nearly empty liquor bottles. The police later learned that Mitts had spent the afternoon target shooting at the Stonewall Range, a firing range. Upstairs in apartment 204, detectives found Bryant’s body. Dr. Heather Raaf, a forensic pathologist, performed autopsies on John Bryant and Sgt. Dennis Glivar. Bryant bled to death within thirty minutes as a result of a single gunshot wound to his chest piercing both lungs and tearing the aorta. Sgt. Glivar died within “a few minutes” from five gunshots to the trunk causing perforations of his lung, heart, liver, kidney, stomach, and intestines. Sgt. Glivar also had been shot in the left shoulder and forearm. Dr. Raaf recovered multiple bullets or fragments from Sgt. Glivar’s body and one small-caliber bullet from Bryant’s body. A grand jury indicted Mitts for the aggravated murders of Sgt. Dennis Glivar (Count One) and John Bryant (Count Two) and the attempted murders of Lt. Thomas Kaiser (Count Three) and Officer John Mackey (Count Four). As death penalty specifications, Count One charged that Mitts knowingly murdered a peace officer in the performance of his duties, R.C. 2929.04(A)(6). Both aggravated murder counts contained three separate course-of-conduct specifications relating to the other three shooting victims. See R.C. 2929.04(A)(5). All four counts also had firearms specifications, and Counts Three and Four added a specification that the victims were peace officers.

At trial, Mitts did not contest the evidence proving the facts, but instead attempted to establish that he was too intoxicated to form the required intent to kill. After a penalty hearing, the jury recommended the death penalty on both aggravated murder counts. The trial court sentenced Mitts to death for the aggravated murders and to terms of imprisonment for the attempted murders. The court of appeals affirmed the convictions and sentences.

PRIOR RECORD

Juvenile Offenses: Mitts has no known juvenile arrest record. Due to Mitts’s age, records from the Cuyahoga County Juvenile Court are no longer available.

Adult Offenses: Mitts has the following known adult arrest record: 8/15/94 Aggravated Murder Garfield Heights, Ohio INSTANT OFFENSE

INSTITUTIONAL ADJUSTMENT:

Mitts was admitted to the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction on December 6, 1994. His work assignments while incarcerated at the Southern Ohio Correctional Facility, Mansfield Correctional Institution, and Ohio State Penitentiary included Porter and Tutor. Since his transfer to the Chillicothe Correctional Institution, Mitts’s work assignment has been as a Porter. Mitts reported that he graduated from Garfield Heights High School in 1970 and attended one and a half years of college studying photo journalism.

Since his admission, Mitts has been placed in disciplinary control one time. He was found guilty of causing or attempting to cause physical harm to another inmate and disobedience of a direct order, which involved Mitts arguing with another inmate after they received their dinner trays. Mitts and the other inmate were ordered to stop by a correctional officer. Mitts ignored the order and began to fight with the other inmate. Mitts received eight days of disciplinary control for the infractions. He has also received one conduct report that did not result in disciplinary control, which involved possession of contraband that included one bottle of paint and two can openers. Mitts received a warning and the contraband was destroyed.

APPLICANT’S STATEMENT:

On August 6, 2013, members of the Ohio Parole Board conducted an interview with Mitts via videoconference from the Chillicothe Correctional Institution. The following individuals observed the interview via videoconference, but did not participate: Steve Maher from the Office of the Ohio Attorney General; Samuel Porter from the office of Governor John Kasich; Jeff Kelleher, Mitt’s attorney; Robert Dixon, Mitt’s attorney; T. Allan Regas, Assistant Cuyahoga County Prosecutor; Katherine Mullin, Assistant Cuyahoga County Prosecutor; Alan Rossman, Assistant Federal Public Defender; Lori Riga, Assistant Federal Public Defender; David Cerutti, Parole Board Parole Officer; and Jerrold Montgomery, Parole Board Parole Officer.

Ohio Parole Board Chair Cynthia Mausser opened the interview by introducing herself to Mitts. She noted that there were several individuals observing the interview, who were not participating. Chair Mausser identified those individuals. Chair Mausser explained the purpose of the interview to Mitts and noted that his clemency hearing is scheduled for August 19, 2013. Chair Mausser introduced Mitts to the members of the Board who were present for the interview.

Chair Mausser asked Mitts what he would like the Board to consider in determining whether to make a favorable or unfavorable recommendation regarding clemency in his case. Mitts told the Board that there was information that he wanted to share about the two victims in his case whom he killed, John Bryant and Sergeant Dennis Glivar. According to Mitts, the information he would share with the Board was not information that the Board would glean from the records of the case.

Mitts noted that he met Bryant several weeks before he killed him. Bryant’s girlfriend, Tracey Griffin, introduced Mitts to Bryant. According to Mitts, after being introduced, he and Bryant spoke for several minutes. Mitts stated that there was no animosity between Bryant and himself. Mitts related how he shot Bryant several weeks later for no apparent reason. Mitts related that, at the time, he was distraught over his divorce and that he wanted the police to shoot him. Mitts believes that in all likelihood he shot Bryant in an attempt to draw police to his home. According to Mitts, several weeks prior, he had considered shooting himself but could not bring himself to do it for fear of how his suicide might affect his daughter, Melanie.

According to Mitts, he did not intend to shoot and kill Glivar. Mitts described how he himself was shot multiple times during the exchange of gunfire with the police. After being shot, Mitts no longer wanted to die. He continued to exchange gunfire with the police in what was, essentially, a fight for survival, Mitts related. At one point, Mitts fired around a blind corner in an attempt to force the police to back off. Unbeknownst to Mitts, standing just feet away from the barrel of his gun was Glivar, who was shot multiple times and killed. Mitts insisted that it was not his intention to kill Glivar. Mitts noted that, during the standoff with police, he allowed the officers to recover Glivar’s body. Mitts described how, when he shot Glivar, Glivar was attempting to evacuate Mitts’s neighbor and her young son from the apartment building, using his own body as a shield. That makes Glivar a hero in Mitts’s estimation. Mitts stated that he was drinking heavily on the evening of the crime and that alcohol clouded his judgment. At the same time, Mitts insisted that his intoxicated state does not excuse his actions.

Mitts stated that he should have died on the night of the crime. Mitts described how, following a short stay in the hospital, he was transferred to the Cuyahoga County Jail where he found God. Since then, Mitts has tried to spread God’s word to others. After he was sentenced and committed to prison, Mitts received a Bible from Glivar’s mother and sister. He described that Bible as a living testament to forgiveness. Mitts later received a letter from Glivar’s sister, which he read for the Board. In her letter, Glivar’s sister described how her brother’s death impacted her family. Glivar’s sister told Mitts that she and her mother forgive him, and she encouraged Mitts to seek forgiveness from Jesus and to embrace God. Mitts stated that he is very remorseful for killing Bryant and Glivar.

After Mitts concluded his statement, Chair Mausser asked him whether he would like to receive clemency in any form. Mitts responded that he will be leaving that to the Board’s discretion. Mitts told the Board that, regardless of whether he is executed or not, he will one day live in perpetuity with Jesus Christ. The only question to be answered in the clemency determination, Mitts stated, is whether he was going to be required to spend the rest of his natural life in prison. Mitts indicated that while he could easily cope with a lifetime of imprisonment, he is also prepared to go home to Jesus. Chair Mausser then permitted the Board members to direct questions to Mitts. Mitts was asked whether he directed racial epithets toward Bryant immediately before shooting him. Mitts responded that he does not believe that he directed any racial slurs at Bryant. However, Mitts acknowledged that witnesses, including Bryant’s girlfriend, Tracey Griffin, heard him make racially derogatory comments immediately before killing Bryant. Mitts had no explanation as to why he did not shoot Griffin or Timothy Rhone, two white individuals who he encountered on the night of the crime. Mitts insisted that he was not then, and is not now, a racist.

Mitts stated that he believes that he received a fair trial. When asked whether a plea agreement was ever offered to him, Mitts indicated that he was never offered any deal from the prosecutor. Mitts suggested that because he was indicted during an election year, no plea agreement was ever going to be offered to him. Mitts indicated that no planning went into his killings of Bryant and Glivar. Mitts insisted that had he put any forethought into his actions he would not have used handguns, but would have used a rifle with a scope. As further evidence that he did not premeditate the murders, Mitts pointed to the fact that most of the ammunition that he had accumulated in his apartment was small caliber 0.22. Mitts stated that the thousands of rounds of ammunition that he had in his home was intended for use at the shooting range and was not an inordinate amount. Lastly, Mitts asked, rhetorically, why he would voluntarily surrender Glivar’s shotgun to the police if his intent on the night of the crime was to engage in mass killing.

Mitts spoke further about his ex-wife, Janice, and her husband Jonathon Salerno, whom she married after divorcing Mitts. Mitts recounted how he had once fantasized about killing both Janice and Salerno. Mitts indicated that he initially felt a great deal of animosity toward Salerno. According to Mitts, Salerno, a local police chief, routinely abused his authority, harassing Mitts and others. Mitts related that he once followed Salerno with a gun and had him “scoped out.” Mitts stated that it was for the sake of his daughter that he did not kill Salerno. According to Mitts, his daughter had grown close to Salerno so he spared Salerno’s life. Mitts stated that, over time, he became friends with Salerno.

Mitts stated that he has had no contact with his daughter for the vast majority of his incarceration. After three years of letter writing following his commitment to prison, communication between Mitts and his daughter stopped. Mitts noted that he has an aunt who keeps in contact with him. His brothers and sister write him occasionally and sometimes send him money. Mitts indicated that he was not surprised when he was sentenced to death in 1994. The death sentence caused him no great consternation. He has appealed his death sentence through the years because it was recommended by his attorneys and was the normal course.

When asked why he ultimately decided to participate in the clemency interview after vacillating on that decision, Mitts responded that he originally refused to participate in order to convey to the Board that he did not want clemency. He was later moved by the Lord to participate. When asked whether he wants to live, Mitts responded that there will be eternal life for him with Jesus. Chair Mausser thanked Mitts for participating in the interview, explained to him the remaining phases of the death penalty clemency process, and concluded the interview.

ARGUMENTS IN SUPPORT OF CLEMENCY:

A clemency application was submitted to the Parole Board. On August 19, 2013, a hearing was conducted to further consider its merits. Mitts’s attorney, Jeff Kelleher, represented Mitts at the clemency hearing and presented arguments in support of clemency. Kelleher’s co-counsel, Robert Dixon, was present but did not make any statements.

Kelleher noted that he has represented Mitts since Mitts undertook his federal habeas corpus appeals. Kelleher conceded that there was no contesting Mitts’s guilt on any element of the offenses for which he was convicted, and the evidence against Mitts was strong. Kelleher stated that he had no intention of twisting the facts or playing with the truth during his presentation. Kelleher advanced three arguments in support of clemency, the first two of which are related. First, Kelleher challenged the representation provided Mitts at trial by his attorney at that time, Thomas Shaughnessy. Second, Kelleher argued that Mitts is not, as Kelleher believes the State is suggesting, a racist cop killer who is remorseless and without redeeming qualities. Third, Kelleher argued that clemency is warranted because the State is on the cusp of changing its death penalty protocol. According to Kelleher, Mitts’s situation is much more complicated than it might appear on its face. Kelleher spoke of the remorse that Mitts feels today. He described the Bible that was given to Mitts by Glivar’s mother and sister, which has never left Mitts’s hands. Mitts opens the Bible every day. He had followed the admonition of Glivar’s family that he embrace God. By doing so, Mitts is honoring the wishes of his victims, Kelleher urged. In that way, Mitts and his victims are forever connected. That, according to Kelleher, is how Mitts manifests his remorse. Mitts is not an outwardly emotional person, Kelleher stated. Kelleher urged the Board not to conclude from Mitts’s stiff, unemotional, and militaristic demeanor that he is remorseless.

Kelleher related that when he first met Mitts, Mitts stated to him that he was the only guilty man on death row. Mitts always acknowledged that he deserved whatever punishment was ultimately imposed upon him. Kelleher insisted that Mitts was not racist, despite the racist epithets he repeatedly uttered on the night of the crime. Kelleher urged the Board to consider the allegation that Mitts is racist in the context of what the evidence in the case does and does not demonstrate. Kelleher noted, for instance, that a search of Mitts’s apartment following his arrest uncovered no racist literature. Though Mitts’s ex-wife once indicated that Mitts had at one time contemplated joining the Ku Klux Klan, her allegation has never been substantiated, Kelleher insisted. Kelleher noted that for 19 years Mitts has lived peacefully on death row with other ethnic groups, including African Americans. In the years preceding his crime, there was never any indication that Mitts was racist. In evaluating whether Mitts is or is not a racist, Kelleher urged the Board to look at the person that Mitts was both before and after the crime.

Kelleher argued that Mitts’s history of racial tolerance and other positive qualities were never developed at trial. According to Kelleher, there was a rush to judgment in Mitts’s case. The trial, verdict, and sentencing all occurred within 90 days, Kelleher noted. Shaughnessy could not have thoroughly researched Mitts’s background and provided an adequate defense in such a short period of time, Kelleher insisted. Shaughnessy therefore effectively abandoned Mitts during the trial process. According to Kelleher, Mitts’s trial was more about Shaughnessy’s personal aggrandizement than competently defending Mitts.

Kelleher urged the Board to view Mitts’s trial in the context of how Cuyahoga County was handling capital cases in the 1990s. According to Kelleher, those cases were repeatedly referred to the same defense attorneys, who were more concerned with media exposure and posturing than defending their clients. Kelleher specifically took issue with the theory advanced at trial by Shaughnessy that Mitts had experienced amnesia caused by alcohol blackout. Essentially, Shaughnessy’s sole defense theory was that Mitts was too intoxicated on the night of the crime to form the requisite criminal intent to kill. That defense, Kelleher urged, was created out of whole cloth. Shaughnessy’s own trial expert refuted his blackout theory. Kelleher argued that the blackout defense was foisted upon Mitts, who never denied that he was aware of what he was doing on the night of the crime and had control over his faculties throughout. Shaughnessy thus painted an incomplete picture of Mitts to the jury, Kelleher argued. Mitts was presented to the jury as a calculating, cold-blooded killer who was attempting to hide behind a weak intoxication defense. Kelleher argued that Mitts’s trial attorney should have instead painted for the jury a more complete picture of who Mitts was when he committed his crimes. Shaughnessy should have dissected Mitts’s life for the jury at the mitigation phase of the trial, describing Mitts’s several divorces and his struggle with depression, which included suicidal ideation.

Nor did Shaughnessy describe for the jury how Mitts had served his country in the Coast Guard and was gainfully employed following his discharge, Kelleher noted. Shaughnessy never informed the jury that, despite the implication that Mitts was a racist, Mitts had in fact worked alongside African Americans for many years without incident. As important as all of that information was, Shaughnessy ignored it, Kelleher argued. In short, Mitts was abandoned and betrayed by his trial counsel, Kelleher urged. The trial was a calamity. There was no reason for Shaughnessy to adopt the blackout defense, Kelleher insisted. While conceding that he has no way of knowing how Mitts’s trial would have turned out had Shaughnessy handled it differently, Kelleher stated that he knows that Mitts was denied the opportunity to present his true self during the trial and, specifically, to refute the implication that he is a racist. Up to the night of the crime, Mitts had lived a law-abiding life. However, in the weeks preceding the shootings, Mitts began to unravel. His suicidal thoughts were becoming more frequent. He was self-medicating with alcohol. Mitts was also stalking his wife and her new husband, Kelleher noted. In short, Mitts was beginning to act very bizarrely. Mitts did not kill Bryant because Bryant was African American, Kelleher insisted. Rather, Mitts killed Bryant to draw the police to him and to kill him. According to Kelleher, he was “fanning the flames” by making racially provocative remarks to hasten his own death at the hands of the police. That Mitts survived the night of the crime is nothing short of a miracle.

Kelleher described Mitts as asymptomatic today. He indicated the Mitts does not currently entertain any thoughts of suicide. Kelleher described Mitts as completely honest to the point of being compulsively truthful. As evidence of his truthfulness, Kelleher pointed to the fact that Mitts confessed to the Board during his clemency interview that, in the period preceding the crime, he had been stalking John Salerno and was contemplating killing him. Mitts is so compulsively truthful, Kelleher argued, that Mitts could not support the false blackout theory that Shaughnessy was advancing at trial. While alcohol has always been part of Mitts’s problems, Mitts himself has never attempted to hide behind it or otherwise tried to skirt responsibility for his crime. Kelleher argued that given his honest nature, were Mitts in fact a racist, he would acknowledge it to the Board. Kelleher opined that Mitts is fundamentally a good man.

Kelleher addressed the fact that Mitts possessed several firearms and accumulated thousands of rounds of ammunition, noting that it is not clear why Mitts accumulated the firearms and ammunition. Guns and ammunition were not a life-long obsession for Mitts. Mitts’s interest in firearms was something that developed well into his adulthood. It was part of the psychological changes that emanated from Mitts’s divorces and his ensuing depression, Kelleher argued. Kelleher noted that the Department of Rehabilitation and Correction intends to adopt a new death penalty protocol in October 2013, which is after Mitts’s scheduled execution date. Kelleher described this as an interesting stage in Ohio’s death penalty history, and described the current system as defective and flawed. According to Kelleher, Billy Slagle’s recent death row suicide is an example of those defects and flaws. Kelleher urged the Board not to use Mitts as a “free pass” to demonstrate that the existing death penalty protocols work, thereby quieting any questions or concerns raised by Slagle’s suicide. In short, Kelleher argued, the existing death penalty system is broken and needs to be retooled. Mitts should not be the last of the line of inmates executed as part of that broken system. Mitts should be a part of the death penalty reforms and not the memory of a deficient system, Kelleher argued.

Kelleher addressed Mitts’s views on the appellate process and these clemency proceedings. Kelleher acknowledged that, during his clemency interview, Mitts conveyed ambivalence about clemency. According to Kelleher, Mitts has always believed that his death sentence was just. If he downplayed the appeals process during his interview, it is because Mitts has always accepted responsibility for his crime, Kelleher argued. Mitts’s attitude toward the appeals process is a manifestation of his own remorse. According to Kelleher, after his appeals were exhausted and clemency proceedings commenced, Mitts wrestled with the decision as to whether to participate in the Parole Board clemency interview, eventually deciding to participate because there were things that he wanted the Board to know, including his view that Bryant and Glivar were heroes. Mitts wanted to use the clemency process as an opportunity to continue his atonement. Kelleher explained that Mitts authorized him to speak on his behalf and to explain to the Board who Mitts is as a person. Kelleher believes that Mitts, today, does want clemency, as he speaks of how God might have a plan for him were his sentence to be commuted to life. Kelleher stressed that he was present at the clemency hearing because Mitts wanted him to be there.

ARGUMENTS IN OPPOSITION TO CLEMENCY:

Assistant Ohio Attorney General Steve Maher, Assistant Cuyahoga County Prosecutor T. Allan Regas, and Assistant Cuyahoga County Prosecutor Katherine Mullin presented arguments in opposition to clemency. Mullin showed the Board several PowerPoint slides. The slides included photographs of Bryant and Glivar taken when they were both still alive; various photographs of the crime scene; and photographs of the firearms and ammunition recovered from Mitts’s apartment following his capture. In addition, one of the slides in Mullin’s PowerPoint contained a photograph of a bumper sticker found in Mitts’s apartment that read: “Gun control means hitting what you aim at.”

Mullin noted that, despite the overwhelming police presence at the clemency hearing, the hearing is not solely about Sergeant Glivar, but also John Bryant, who was Mitts’s first fatality. Bryant was killed for no other reason than that he was African American and in front of Mitts, who is a racist, Mullin argued. Mullin noted that Bryant was not the first person that Mitts encountered after he armed himself on the night of the crime. That person was Timothy Rhone, a white man. Instead of killing Rhone, Mitts directed him to leave the building. Nor did Mitts kill Bryant’s girlfriend, Tracey Griffin, another white individual at the scene. Mitts continued to use racial epithets throughout the police standoff, Mullin pointed out. Mullin stated that, like Kelleher, she agrees that the Board should examine the context and evidence in the case when evaluating whether Bryant’s death was racially motivated. In her view, that context and evidence leads to no other conclusion than that Mitts was a racist who targeted Bryant because of the color of his skin. Mitts was able to hide his racism until the night of the crime, when he could contain it no longer, Mullin argued. Mullin stated that Mitts should not be executed because he is racist. Rather, he should be executed because he took the lives of two individuals. The State has no need to fabricate racism or any other reason to support Mitts’s execution, Mullin insisted. Mitts’s crimes alone are sufficient reason to carry out his death sentence. Regas added that, while Mitts’s racism is not a legitimate basis upon which to execute him, it is relevant because it puts his actions into context. Mitts was not, as Kelleher suggests, using race to “fan the flames” on the night of the crime. On the contrary, Regas argued, the crime itself was racially motivated. Were Mitts merely using race to fan the flames, Mitts would have related that fact to the Board during his clemency interview, but he did not.

Regas refuted the notion that Mitts’s relationships with African Americans were entirely copasetic in the period preceding the shooting. Regas noted that Mitts had previously reported to Salerno that Mitts was having difficulties at work that Mitts believed were race-related. Regas noted that, were Mitts’s motivation simply to commit suicide by cop, he could have accomplished that purpose by walking up to a police officer with an unloaded firearm. There was no need to take anyone’s life other than his own. Mitts’s actions, along with the guns and ammunition found in his apartment, clearly demonstrate that Mitts was out to kill people on the night of August 14, 1994, Regas argued. Mullin then described the responding officers’ heroics on the night of the crime. She described how Mitts immediately fired upon one of the first officers responding to the scene, Jon Cermack. Not far behind Cermack were Kaiser and Glivar, who were also among the first on the scene.

Mullin related how Mitts opened his apartment door and confronted Kaiser and Glivar in a shooter’s position wearing ear and eye protection, which suggests that he was spoiling for a firefight. Mullin related how Mitts killed Glivar and shot Kaiser twice. She challenged Mitts’s contention that he did not intend to shoot and kill Glivar. The idea that Glivar was simply in the wrong place is meritless. Mullin stated that it was Mitts’s philosophy to hit what he aimed at, referring to the bumper sticker that was found in Mitts’s apartment. Despite being seriously wounded, Kaiser continued to attempt to negotiate with Mitts, Mullin related. Meanwhile, Mitts shot another police officer, John Mackey. After fatally wounding Glivar, Mitts picked up Glivar’s shotgun and began firing into the walls of the surrounding apartments. Every one of those gunshots could have produced another victim, Mullin pointed out, as Mitts was on a terroristic rampage. Mullin described how deeply Mitts’s actions affected everyone at the crime scene, including the emergency medical personnel who treated the several victims. Mullin challenged Kelleher’s suggestion that Mitts was an otherwise law-abiding individual who snapped. Mitts acted with prior calculation and design, Mullin insisted. As evidence of Mitts’s propensity for criminal calculation, Mullin pointed to Mitts’s own admission during his clemency interview that he had been stalking Salerno. In short, Mitts had the propensity to kill and could have very easily killed before, Mullin argued. The events of August 14, 1994 were a virtual inevitability, she contended. Maher then added that Mitts’s premeditation is evidenced by the manner in which he killed Bryant. Maher noted that the weapon that he used to kill Bryant had a red laser dot sight, a device used to ensure precise aim. Mitts used that sighting device to shoot Bryant through his aorta, which was as fatal a shot as Mitts could have delivered to Bryant. Mitts did not exhibit disorganized behavior during the shooting, Maher added. Mullin challenged the notion that Mitts’s trial counsel was ineffective. Although Shaughnessy’s blackout theory ultimately failed, it was not unreasonable. Mullin noted that Kelleher offers no viable alternative theory that trial counsel could have advanced. The jury was aware that Mitts had been depressed in the past. That, and any remaining mitigation, was simply not sufficient to outweigh the aggravating factors, Mullin suggested. In any case, Mitts’s ineffective assistance of counsel claims have been thoroughly litigated.

Mullin argued that the 90-day timeframe in which Mitts’s trial was conducted was not unreasonable. The trial was conducted within the parameters of Mitts’s constitutional right to speedy trial, she pointed out. According to Mullin, Mitts was not remorseful during his clemency interview. She acknowledged that Mitts stated that he was remorseful; however, in her opinion, he did not actually demonstrate it. That Mitts spoke of remorse means little, Mullin argued. In her experience, when someone speaks of how remorseful they are, that is usually the first indication that the person is in fact remorseless. Mullin speculated that Mitts’s unwillingness or inability to demonstrate remorse may be related to the fact that he is not wholeheartedly seeking clemency. Regas observed that Mitts himself has never directly requested that his life be spared. Only upon prodding from the Board during the clemency hearing has Mitts’s attorney requested, without equivocation, that Mitts be granted clemency, Regas stated. Regas noted that he was present for Mitts’s clemency interview and was struck by Mitts’s lack of emotion during the interview. Regas observed that the only moments of the interview during which Mitts exhibited any emotion was when describing his tactical actions and decisions on the night of the crime, which Mitts apparently took great pleasure in detailing for the Board. Regas disagreed with Kelleher’s contention that Mitts is compulsively truthful, and argued that Mitts does not always tell the truth. Regas pointed out that when the Board asked Mitts about the racial epithets that he was heard uttering on the night of the crime, Mitts indicated that he did not recall making the statements. His evasive answers on that issue demonstrate that Mitts is not always truthful. Regas insisted that Mitts’s actions and his behavior during the clemency interview demonstrate that he is not the good man that Kelleher describes him to be.

Maher then added that Kelleher’s argument that Mitts has never shirked responsibility for his crime is contradicted by both the court records and the clemency interview. In addition to attempting to shirk responsibility by disavowing any racial component to the crime, Mitts also attempted to shirk responsibility during his trial years ago, Maher argued. Maher noted that Mitts raised the issue of ineffective assistance of counsel in federal court, arguing that his trial counsel compelled him to go along with a blackout defense that he did not support. Maher observed that Mitts only raised that claim after he received the death sentence, but up to that point, Mitts appeared quite content to pursue the blackout defense. Maher noted that Mitts had even provided an unsworn statement to his jury stating that he had no memory of what occurred on the night of the crime until police related to him what transpired. Thus, Maher argued, at the time of trial, Mitts attempted to shirk responsibility by facilitating a blackout defense that he now claims had no basis in fact.

Maher disagreed with Kelleher’s contention that Mitts’s trial counsel abandoned Mitts by failing to address the racial component. Maher noted that racial animus was not an element of any of the crimes with which Mitts was charged. Therefore, the prosecution was not required to prove that Mitts acted with racial motivation. The upshot of that, Maher argued, was that, though Mitts’s racial motivation lurked in the background of his trial, Mitts’s apparent racial animus was not an issue that Shaughnessy could directly confront at trial. Therefore, Shaughnessy addressed the issue indirectly. For instance, when cross-examining an employee from the shooting range that Mitts frequented, Shaughnessy asked the witness whether he recalled Mitts bringing an African-American friend with him to the shooting range. Similarly, when cross-examining Bryant’s girlfriend, Tracey Griffin, Shaughnessy questioned her about her ex-husband, who was African American; how Mitts was aware that Griffin’s ex-husband was African American; and how Mitts remained friends with Griffin notwithstanding her past relationship with an African-American man.

According to Maher, the allegation that Shaughnessy ignored the issue of race at trial is thus directly contradicted by the record. Shaughnessy addressed the issue in the only way that he could given that racial animus was not an element of the charged crimes, Maher argued. Mullin argued that the upcoming change in the lethal injection protocol should have no bearing on Mitts’s execution. According to Mullin, the fact that Mitts will be the last person to die under the existing protocol is not a legitimate basis for clemency. The current protocol is constitutional, she noted. Maher added that Mitts himself has never been a party to the state’s lethal injection litigation, which has been pending in federal court for several years. Having never joined the lethal injection litigation, Mitts is not now in a position to obtain any legal relief from it. Mullin then concluded the State’s presentation by noting that the office of the Cuyahoga County Prosecuting Attorney recently conducted an exhaustive review of Mitts’s case and determined that the death penalty remains an appropriate penalty in his case. She asked that the Board make an unfavorable recommendation regarding clemency.

VICTIMS’ REPRESENTATIVES:

Bryant’s sister, Johnnal Bryant, read from a letter directed to Mitts. In it, she noted that her family can now finally find closure as Mitts’s execution date approaches. She recognized that Mitts’s execution will not bring her brother back. However, it will give her a sense of satisfaction that justice is finally done. She noted that her brother lived only 30 minutes after he was shot while Mitts has lived for 19 years. She noted that before shooting her brother, Mitts had contemplated killing his ex-wife and her new husband but chose not to because of the impact it would have upon his daughter. She asked, rhetorically, whether Mitts ever realized that Bryant too had a family who loved him. Who made Mitts God that he could take a life, she asked. Mitts may think he is going to heaven, but he is not, she stated.

Donald Dean, a minister and friend of the Bryant family, stated that Mitts acted purposely when he killed Bryant. Mitts chose to kill Bryant because Mitts was racist, Dean opined. It was a clear-cut case of murder. Mitts was a cold-blooded killer who hated African Americans. While he and the Bryant family have forgiven Mitts, they have not forgotten what he has done. Dean described how Bryant had turned his life around in the years preceding his death. Bryant had made several positive changes in his life, including embracing God. Dean indicated that it would, in his opinion, be an injustice for Mitts not to suffer the consequences for what he has done.

Tom Kaiser read from a prepared statement. Kaiser cannot imagine the pain that the

Glivar and Bryant families have experienced as they wait for justice to be carried out.

Kaiser noted that he and Glivar were good friends, and described how, ten minutes before

responding to Mitts’s apartment, they were eating together and complaining about the

ongoing baseball strike. Just ten minutes later, they were cowardly ambushed by Mitts.

Kaiser insisted that Mitts could not have shot him twice and Glivar five times were Mitts

in a blackout state, as Mitts’s trial counsel had suggested. Kaiser continued his police

career after being shot, but was away from work for a year. Many of the officers present

at the scene, including himself, were psychologically scarred for life, Kaiser reported.

Kaiser described Mitts as a racist assassin and a cop killer. Kaiser stated that it is time

that everyone affected by Mitts’s crime receive the justice they so deeply deserve.

Glivar’s wife, Debbie Glivar, noted that she had been married to her husband for eleven

years when Mitts took his life. She spoke of the last moments that she spent with her

husband, and related how it is impossible for her to articulate how her life has been

affected by her husband’s death because her life is filled with what-ifs. She dwells on

thoughts of what she has missed out upon in her life. She loved being married to her

husband and she still misses her life with him. Her life today is incomplete and in limbo; she moves constantly because she does not know where she is supposed to be. Her

husband was everything to her.

Jonathon Salerno, a former Grand River Police Chief and the husband of Mitts’s ex-wife,

spoke of how he adopted Mitts’s daughter, Melanie, after Mitts was convicted. According

to Salerno, the Mitts he knew was a racist who hated police. Salerno described how Mitts

called him during the standoff with police and told him that he had killed a cop and

Bryant, using a racial epithet to describe Bryant. At no time during that conversation did

Mitts discuss suicide, Salerno related. Salerno indicated that his prior encounters with

Mitts were consistently negative, describing Mitts as a very aggressive person. Mitts

would tell Salerno that he had no use for cops or black people. Mitts liked to describe his

weapons to Salerno. Salerno described how Melanie once returned from a scheduled visit

with Mitts and told Salerno that Mitts had asked her if she wanted to meet his new

girlfriend, a gun. When speaking on the telephone during the standoff with police, Mitts

told Salerno that he had intended to kill Salerno too until Melanie had told him how much

she loved Salerno. Salerno does not believe that Mitts should receive clemency. Rather,

Salerno urged, he should get what he deserves—death by lethal injection.

PAROLE BOARD’S POSITION AND CONCLUSION:

The Ohio Parole Board conducted an exhaustive review of documentary submissions and

carefully considered the information presented at the clemency hearing. The Board

reached a unanimous decision to provide an unfavorable recommendation regarding

clemency for the following reasons:

• The Board is not persuaded that the unsuccessful blackout theory advanced by

Mitts’s trial attorney warrants clemency on the theory that advancing the defense

amounted to ineffective assistance of counsel. Although that defense tactic

ultimately proved unsuccessful, it remains unclear what alternative trial strategy

would have produced a different result. In any case, that and other claims of

ineffective assistance of counsel advanced by Mitts through the years, have all

been extensively litigated in, and rejected by, the reviewing courts.

• Mitts accepts responsibility for the crime, but only to a point. Mitts continues to

deny or minimize many of the most troubling aspects of his crime. For instance,

despite using racial slurs prior to shooting Bryant and during the ensuing police

standoff, Mitts denies that the crime was racially motivated. Likewise, the record

belies Mitts’s insistence that he only accidentally shot Glivar and Kaiser in an

attempt to make the officers retreat. Mitts’s claim that he was, at first, attempting

to commit suicide by cop and then, later, to survive the police standoff is also

patently lacking in credibility. As the State points out, if Mitts’s purpose was

simply to be shot and killed by the police, he could have accomplished that by

pointing an unloaded gun at officers. It also speaks volumes that Mitts did not

immediately surrender after he supposedly decided that he wanted to live. Lastly,

the Board is troubled by Mitts’s suggestion during his clemency interview that the

various weapons and the thousands of rounds of ammunition in his apartment were

reasonable in quantity and not intended for any nefarious purpose.

• The Board finds no merit in the argument advanced by Mitts’s attorney that

impending changes in the death penalty protocol somehow renders suspect Mitts’s

execution under the existing process.

• Standing in juxtaposition to the insubstantial bases for clemency advanced by

Mitts’s attorney are the aggravating characteristics of Mitts’s crime, which are

many. It is apparent that Mitts targeted his first victim, John Bryant, because

Bryant was African American. Mitts then engaged in a protracted standoff with

police, exchanging gunfire with officers and randomly discharging various

firearms. Mitts exhibited a complete disregard for the lives of officers and

innocent bystanders at the scene. In the end, in addition to killing Bryant, Mitts

killed one police officer and wounded two others. That further tragedy did not

result from the bedlam that Mitts created on August 14, 1994 is in many respects a

miracle, and is testimony to the fine work of the law enforcement officers who

responded to the scene. Given the multiple deaths, the racial animus underlying Bryant’s death, and the law enforcement victims Mitts targeted, Mitts’s case is

clearly among the worst of the worst capital cases.

• Mitts’s crime not only deeply affected the lives of its immediate victims, it also

had a profound impact upon the Garfield Heights Police Department, and the

larger community in which it occurred.

RECOMMENDATION:

The Ohio Parole Board with eleven (11) members participating, by a vote of eleven (11)

to zero (0) recommends to the Honorable John R. Kasich, Governor of the State of Ohio,

that executive clemency be denied in the case of Harry Mitts Jr., A305-433.

On the evening of August 14, 1994, Timothy Rhone helped his sister and brother-in-law, Jeff Walters, move into their apartment. The apartment was on the second floor in the same building where Harry D. Mitts lived. Between 7:00 and 8:00 p.m., Rhone noticed a man, who he later learned was Mitts, carrying a gun tucked into the small of his back. Fifteen to thirty minutes later, Mitts, who was wearing blue target-shooting earmuffs, confronted Rhone in the hallway. According to Rhone, Mitts pointed a "black and huge" laser-sighted gun at Rhone's head and "told him to get out or he was going to fucking die." When Rhone replied that he did not understand, Mitts said, "I'm not joking, get out now." Rhone backed away and asked his mother and sister to call 9-1-1 because "a man with a gun was threatening to shoot people."

A short time later, Tracey Griffin and her boyfriend, John Bryant, saw Mitts walking toward them wearing yellow glasses or goggles and carrying a gun. Griffin knew Mitts because they lived in the same apartment complex and their daughters had played together. Mitts's gun emitted a light, and Griffin saw a dot of red light appear on Bryant's chest. Mitts said, "Ni**ers, ni**ers, I'm just sick and tired of ni**ers." Mitts aimed directly at Bryant, Griffin heard a shot, and Bryant fell down. Mitts then walked away, sporadically firing his gun, and later walked back toward Griffin, still firing his weapon, but now in her direction.

In the meantime, Walters and Terry Rhone, Timothy's brother, came out to help Bryant. Mitts aimed his gun and shouted at them, "Leave him there, don't move." Walters and Terry Rhone disregarded Mitts's instruction and carried Bryant into their second-floor apartment. Around 8:15 p.m., Patrolman John Cermak arrived, and a bystander saw Mitts put a new clip in his gun. Taking "a ready firing position," Mitts fired several shots at Patrolman Cermak, forcing Cermak to drive his car up on a lawn and take cover. Lt. Kaiser and Sergeant Dennis Glivar then arrived. After firing at Patrolman Cermak, Mitts retreated to his first-floor apartment.

Patrolman Cermak searched for Mitts, and Lt. Kaiser and Sgt. Glivar went to the apartment building's second floor, where they found Griffin, Bryant, and the Rhone family. After calling paramedics, Lt. Kaiser and Sgt. Glivar walked down to the first floor. As Lt. Kaiser and Sgt. Glivar approached Mitts's apartment, Mitts flung his apartment door open and opened fire with a gun in each hand. Mitts repeatedly shot Sgt. Glivar, forcing him to drop his shotgun, and he shot Lt. Kaiser in the chest and right hand. Lt. Kaiser switched his pistol to his left hand and forced Mitts to retreat by firing three or four times. Lt. Kaiser returned to the Rhone apartment, where he kept a watch on Mitts's apartment, and radioed for police assistance including the area SWAT team. Although wounded, Lt. Kaiser attempted for twenty to thirty minutes to talk Mitts into surrendering, but Mitts replied, "The only way we're going to end this is if you kill me. You have to come down, you have to do your job and you have to kill me."

Mitts, who had overheard Lt. Kaiser's SWAT request over Sgt. Glivar's abandoned police radio, additionally told Lt. Kaiser, "Go ahead, bring the SWAT team in, I have thousands of rounds of ammunition. I'll kill your whole SWAT team. I'll kill your whole police department." Mitts also threatened Griffin; Mitts told Lt. Kaiser that he was "going to come up and kill that ni**er-loving bitch that's upstairs with you." Mitts also told Lt. Kaiser that he had been drinking bourbon and was angry because the Grand River Police Chief "stole my wife." Eventually, Patrolman Cermak dragged Sgt. Glivar's body from the hallway and Patrolman Cermak and others used a ladder and rescued Rhone's family and Lt. Kaiser from the upstairs apartment.

During the standoff, Mitts called his ex-wife, Janice Salerno, and her husband, Grand River Police Chief Jonathon Salerno. Chief Salerno thought Mitts was joking when Mitts told him that "it's all over with now, I shot a couple of cops and I killed a fucking ni**er." Chief Salerno, who believed Mitts was drunk, tried to talk him into surrendering, but Mitts refused. Mitts claimed that he had intended to kill both Salerno and his wife, but did not because Mitts's daughter, Melanie, lived with the Salernos.

Around 8:40 p.m., Maple Heights Police Officer John Mackey responded to the call for police assistance from the city of Garfield Heights. After helping Patrolman Cermak rescued Lt. Kaiser and the Rhone family, Officer Mackey, Sergeant Robert Sackett, and others took tactical positions in the hallway outside Mitts's apartment. Taking over Lt. Kaiser's role as a negotiator, Officer Mackey talked with Mitts for over thirty minutes, but Mitts refused to surrender and, at various times, continued to fire shots. Using Sgt. Glivar's shotgun, Mitts fired twice into a mailbox across the hall, and he also emptied ten pistol shots into that mailbox. According to Officer Mackey, Mitts's voice appeared calm, and he "never showed any anger or animosity towards" the officers.

Around 9:30 p.m., Mitts discerned Officer Mackey's position in the upstairs apartment from the sound of his voice and fired up the stairway and through a wall, hitting Officer Mackey's leg with a bullet fragment. Other police officers returned fire and rescued Officer Mackey. Around 1:00 a.m., the SWAT team injected tear gas into Mitts's apartment and finally subdued Mitts around 2:00 a.m. Mitts, who had been shot during the standoff, was taken by ambulance to a local hospital, then transported by helicopter to a trauma center at Cleveland's MetroHealth Medical Center. At 3:43 p.m., a blood sample was drawn from Mitts, and his blood-alcohol level was later determined to be .21 grams per one hundred milliliters.

After arresting Mitts, detectives searched his apartment and found two sets of shooting earmuffs, a yellow pair of glasses customarily used on shooting ranges, a .44 caliber magnum revolver, a 9 mm automatic pistol, a .22 caliber pistol, a laser gun-sight, thousands of rounds of ammunition in boxes, and two nearly empty liquor bottles. The police later learned that Mitts had spent the afternoon target shooting at the Stonewall Range, a firing range.

Upstairs in apartment 204, detectives found Bryant's body. Dr. Heather Raaf, a forensic pathologist, performed autopsies on John Bryant and Sgt. Dennis Glivar. Bryant bled to death within thirty minutes as a result of a single gunshot wound to his chest piercing both lungs and tearing the aorta. Sgt. Glivar died within "a few minutes" from five gunshots to the trunk causing perforations of his lung, heart, liver, kidney, stomach, and intestines. Sgt. Glivar also had been shot in the left shoulder and forearm. Dr. Raaf recovered multiple bullets or fragments from Sgt. Glivar's body and one small-caliber bullet from Bryant's body.

A grand jury indicted Mitts for the aggravated murders of Sgt. Dennis Glivar and John Bryant and the attempted murders of Lt. Thomas Kaiser and Officer John Mackey. As death penalty specifications, the prosecution charged that Mitts knowingly murdered a peace officer in the performance of his duties. Both aggravated murder counts contained three separate course-of-conduct specifications relating to the other three shooting victims. All four counts also had firearms specifications, and the attempted murder counts added a specification that the victims were peace officers. At trial, Mitts did not contest the evidence proving the facts, but instead attempted to establish that he was too intoxicated to form the required intent to kill. After a penalty hearing, the jury recommended the death penalty on both aggravated murder counts. The trial court sentenced Mitts to death for the aggravated murders and to terms of imprisonment for the attempted murders.

Ohio Death Row: Mitts News & Blog

Contact: Governor Kasich

Ohio Attorney General - 2012 Capital Crimes Annual Report

Ohio Executions 1999-2013 from Cleveland.Com

List of individuals executed in Ohio

A list of individuals convicted of murder that have been executed by the U.S. State of Ohio since 1976. All were executed by lethal injection.

1. Wilford Berry, Jr. (19 February 1999) Charles Mitroff

State v. Mitts, 81 Ohio St. 3d 223, 690 N.E.2d 522 (Ohio 1998). (Direct Appeal)

Appellant, Harry D. Mitts, appeals from his convictions and sentence to death for the aggravated murders of Sergeant Dennis Glivar and John Bryant and the attempted murders of Lieutenant Thomas Kaiser and Officer John Mackey.

On the evening of August 14, 1994, Timothy Rhone helped his sister and brother-in-law, Jeff Walters, move into their apartment. The apartment was on the second floor in the same building where Mitts lived. Between 7:00 and 8:00 p.m., Rhone noticed a man, who he later learned was Mitts, carrying a gun tucked into the small of his back. Fifteen to thirty minutes later, Mitts, who was wearing blue target-shooting earmuffs, confronted Rhone in the hallway. According to Rhone, Mitts pointed a "black and huge" laser-sighted gun at Rhone's head and "told [him] to get out or [he] was going to fucking die." When Rhone replied that he did not understand, Mitts said, "I'm not joking, get out now." Rhone backed away and asked his mother and sister to call 9-1-1 because "a man with a gun [was] threatening to shoot people."

A short time later, Tracey Griffin and her boyfriend, John Bryant, saw Mitts walking toward them wearing yellow glasses or goggles and carrying a gun. Griffin knew Mitts because they lived in the same apartment complex and their daughters had played together. Mitts's gun emitted a light, and Griffin saw a dot of red light appear on Bryant's chest. Mitts said, "Niggers, niggers, I'm just sick and tired of niggers." Mitts aimed directly at Bryant, Griffin heard a shot, and Bryant fell down.

Mitts then walked away, sporadically firing his gun, and later walked back toward Griffin, still firing his weapon, but now in her direction. In the meantime, Walters and Terry Rhone, Timothy's brother, came out to help Bryant. Mitts aimed his gun and shouted at them, "Leave him there, don't move." Walters and Terry Rhone disregarded Mitts's instruction and carried Bryant into their second-floor apartment.

Around 8:15 p.m., Patrolman John Cermak arrived, and a bystander saw Mitts put a new clip in his gun. Taking "a ready [firing] position," Mitts fired several shots at Patrolman Cermak, forcing Cermak to drive his car up on a lawn and take cover. Lt. Kaiser and Sergeant Dennis Glivar then arrived. After firing at Patrolman Cermak, Mitts retreated to his first-floor apartment. Patrolman Cermak searched for Mitts, and Lt. Kaiser and Sgt. Glivar went to the apartment building's second floor, where they found Griffin, Bryant, and the Rhone family. After calling paramedics, Lt. Kaiser and Sgt. Glivar walked down to the first floor.

As Lt. Kaiser and Sgt. Glivar approached Mitts's apartment, Mitts flung his apartment door open and opened fire with a gun in each hand. Mitts repeatedly shot Sgt. Glivar, forcing him to drop his shotgun, and he shot Lt. Kaiser in the chest and right hand. Lt. Kaiser switched his pistol to his left hand and forced Mitts to retreat by firing three or four times. Lt. Kaiser returned to the Rhone apartment, where he kept a watch on Mitts's apartment, and radioed for police assistance including the area S.W.A.T. team.

Although wounded, Lt. Kaiser attempted for twenty to thirty minutes to talk Mitts into surrendering, but Mitts replied, "The only way we're going to end this is if you kill me. You have to come down, you have to do your job and you have to kill me." Mitts, who had overheard Lt. Kaiser's S.W.A.T. request over Sgt. Glivar's abandoned police radio, additionally told Lt. Kaiser, "Go ahead, bring the S.W.A.T. team in, I have thousands of rounds of ammunition. I'll kill your whole S.W.A.T. team. I'll kill your whole police department * * * ."