Executed March 22, 2012 at 6:20 p.m. by Lethal Injection in Mississippi

11th murderer executed in U.S. in 2012

1288th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

3rd murderer executed in Mississippi in 2012

18th murderer executed in Mississippi since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(11) |

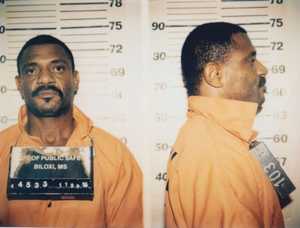

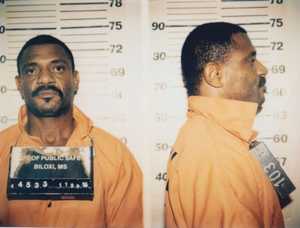

William Gerald Mitchell B / M / 46 - 61 |

Patty Milliken W / F / 38 |

At the time of the murder, Mitchell had been paroled for approximately eleven months from a sentence of life in prison for a previous murder committed in 1974.

Citations:

Mitchell v. State, 792 So.2d 192 (Miss. 2001). (Direct Appeal)

Mitchell v. State, 886 So.2d 704 (Miss. 2004). (PCR)

Mitchell v. Epps, 641 F.3d 134 (5th Cir. 2011). (Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

Big plate of fried shrimp and oysters together, big strawberry shake, cup of ranch dressing, 2 fried chicken breasts and a coke.

Final Words:

None.

Internet Sources:

PARCHMAN — A Mississippi man was executed Thursday for the 1995 slaying of a woman who disappeared from convenience store where she worked in Biloxi. William Mitchell, 61, was pronounced dead at 6:20 p.m. after a lethal injection. He is the second inmate executed this week for also killing a woman in 1995.

Asked whether he wanted to say anything before the chemicals were pumped into his veins, Mitchell emphatically said, "No." Dressed in a red jumpsuit, wearing black-and-white sneakers, Mitchell appeared to lick his lips, took a deep breath and exhaled and then yawned. Moments later he closed his eyes and officials pronounced him dead.

Mitchell was convicted in the Nov. 21, 1995, slaying of 38-year-old Patty Milliken, who disappeared after walking out of the Majik Mart convenience to have a cigarette with Mitchell. Her body was found the next day under a bridge. She had been "strangled, beaten, sexually assaulted and repeatedly run over by a vehicle," according to court records. Mitchell was convicted of capital murder in Harrison County in 1998.

Two members of Milliken's family - son Williams Burns and a sister, Rosemary Riley, - witnessed the execution. Corrections Commissioner Chris Epps said Mitchell didn't want any of his own relatives to witness it, but noted that Mitchell's lawyers were present. Earlier Thursday, Mitchell was visited by a brother and two sisters. Epps said Mitchell was talkative earlier in the day. "Just small talk ... nothing about what he was on death row for," Epps said.

Mitchell's last meal request was for fried shrimp and oysters, ranch dressing, two fried chicken breasts, a strawberry shake and a soft drink. Epps said Mitchell ate very little of the meal, but asked for a sedative.

The Mississippi Supreme Court and the U.S. Supreme Court earlier Thursday declined to stop Mitchell's execution. Gov. Phil Bryant said in a statement that he would not halt the execution. "After reviewing the case of William Mitchell and the crime he committed, I will not stand in the way of the scheduled execution. My thoughts and prayers are with the family and friends of Patty Milliken, who fell victim to this horrible act of violence," Bryant said in the statement.

Mitchell's body will be turned over to his sister, Gerolyn Mitchell, and Brinson Funeral Home in Cleveland.

Court records show Mitchell had been out of prison on parole for less than a year for a 1974 murder when he was charged with raping and killing Milliken. According to court records, Mitchell, as a young adult, served in the Army but by the 1990s, he had a long criminal record and had spent much of his adult life behind bars. He was charged twice with beating women in 1973. In 1974, he was charged with killing a family friend and stabbing her daughter.

In his petition to the Supreme Court, Mitchell had argued the Mississippi courts denied his right to due process by failing to address his challenge that was based on his lawyers' inadequate representation. He said the courts just ignored the issue by saying it had already been adjudicated elsewhere. Mississippi Attorney General Jim Hood in his brief to the Supreme Court said the issues raised by Mitchell were nothing new and were rejected by other courts.

On Tuesday, Larry Matthew Puckett, was executed for the 1995 sexual assault and slaying of the wife of his former boss. Puckett, 35, was convicted of the Oct. 14, 1995, killing of Rhonda Hatten Griffis, a 28-year-old mother of two who lived northeast of Hattiesburg in Petal. Like Mitchell, Puckett said "no" when asked if he had a last statement.

"Mississippi Execution." (March 22, 2012)A Coast man will be executed Thursday for the murder of a Biloxi store clerk who was beaten, strangled, sexually assaulted and still alive when she was run over with a car in 1995. William “Jerry” Mitchell, 61, is scheduled to be the second killer put to death by lethal injection in a week at the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman.

Mitchell has been on death row since 1998, when a Harrison County jury found him guilty in the slaying of 38-year-old Patty Milliken. He was on parole for a previous murder when a Biloxi police officer found Milliken’s body, nude and mutilated, under the Popp’s Ferry Bridge on Nov. 22, 1995. Milliken had lived in Gulfport a couple of years and was a cashier at a Majik Market on Popp’s Ferry Road. The mother of four disappeared from the store near the end of her shift.

Milliken had called her son to tell him she would be home in 15 minutes, and stepped outside the store to smoke a cigarette with Mitchell, court papers show. A few minutes later, a co-worker cut his finger and went outside to get Milliken to relieve him while he bandaged it. Milliken had disappeared, but her purse, car keys and cigarettes were still in the store. Her co-worker reported her missing.

Officer Tim McKaig, now a detective, went looking for Mitchell that night to question him about the disappearance. There was no reason to believe she had been killed, and a camera crew from the TV show “COPS” happened to be in town to film police at work. McKaig testified he found Mitchell in the backyard at his father’s house on Croesus Street. “Before I could say anything,” McKaig said, “he said, ‘Who’s there?’ and I said, ‘Police. I just want to talk to you,’ and he ran.” Mitchell sped off in his Pontiac Grand Am. Police saw his car at a U.S. 90 gas station, and he sped off again with five police cars pursuing him. His car crashed into a chain-link fence near the CSX railroad tracks and Caillavet Street. The “COPS” crew filmed it.

Mitchell was on parole for the 1974 murder of Irene Edwards, also killed in Harrison County. He had stabbed her to death with two butcher knives when he was home from college one weekend.

From missing to murdered

The morning after Milliken disappeared, a police officer who had heard of a missing woman stopped under the Popp’s Ferry Bridge to look for her. He found her body under the north end of the bridge. Forensic examination would reveal she had been assaulted physically and sexually, then the top half of her body was run over repeatedly by a car. Robert Burriss, a crime-scene technician then, said the crime scene ranks high on his list of the worst he ever saw. “He used his car to run over her, back and forth, at least a dozen times,” Burriss said as he recalled finding blood in the back of the car, and blood and hair on the undercarriage of Mitchell’s car. “Her body had very distinctive tire marks,” he said. Tire casts from the scene matched the tread design and size on three of Mitchell’s tires.

In a videotape played at the trial, Mitchell said Milliken left the store willingly and they were going to have sex in the backseat of his car, but they argued and she slapped him and he hit her. He said he ordered her out of his car and that was the last time he saw her.

The jury took 50 minutes to find him guilty on July 23, 1998. The next day, the jury deliberated a little less than two hours and handed then-Judge Kosta Vlahos a death-sentence verdict.

A 14-year wait for execution

A death sentence has an automatic appeal process that usually takes years to resolve. At the time, it had been nine years since the state executed a killer, in part over controversy involving the death penalty and the use of the gas chamber. Mitchell became the state’s 63rd death row inmate in a logjam of executions delayed for reasons such as a nationwide ban on executions for several years. Executions resumed in 2002 after state lawmakers decided a lethal injection is a more humane form of death than gas. Mitchell based one of his appeals on a 2002 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that prohibits the execution of a mentally ill criminal. It’s considered cruel and unusual punishment. His death sentence was upheld in 2004. The ruling said he had served in the military four years, attended college one semester, and was not deemed retarded by a clinical psychologist who interviewed him.

Process has begun

The procedures to execute him have begun, with notifications of relatives and others, and obtaining drugs for the lethal-injection cocktail. The state changed its ingredients in 2011 because of a nationwide shortage of sodium thiopental. The injection that will take Mitchell’s life costs $11,400, according to the Mississippi Department of Corrections. The cocktail is a mixture of pentobarbital, pavulon, potassium chloride and saline. One is an anesthetic, one stops breathing and another stops the heart. Mitchell will be moved from death row Tuesday to a holding cell next to the execution room.

Parchman will be placed on lockdown Wednesday. Inmates won’t be allowed out of their cells unless there’s an emergency, said Suzanne Singletary, MDOC spokeswoman. On Thursday, prison staff will inspect the gurney and syringes, prepare the drugs and fill the syringes. Mitchell’s family will be allowed to visit him between 1 and 3 p.m., just before a visit from his attorney and a chaplain. He also will be able to talk with his family by telephone. Mitchell will receive his last meal at 4 p.m. and will be allowed to shower. A clergyman can then visit if Mitchell wishes.

Witnesses to the execution will be taken to Unit 17 at Parchman 30 minutes in advance. Mitchell will be taken to the execution room and strapped on the gurney about 5:45 p.m. Witnesses will be escorted into the observation room at 6 p.m. An assistant will then insert intravenous lines into Mitchell’s arm. The executioner, who will be paid $500 plus expenses, will administer the drugs. Mitchell will die within minutes. Several of Milliken’s family members plan to watch, but they are not willing to speak to reporters until after the execution, Singletary said.

Burriss, now retired, said he may ask police officials if he can accompany them to witness Mitchell’s execution. “I want to know what he has to say,” Burriss said. “I’d like to know if he shows remorse and has accepted Jesus as his savior. I can’t say I’m really 100 percent for or against the death penalty, but if he falls in the category of not being able to be rehabilitated, I have no problem with the death penalty.”

Mississippi Department of Corrections (Offender Data Sheet)

Inmate: WILLIAM J MITCHELLSentences:1 HOMICIDE- 06/24/1975 HARRISON COUNTY, LIFE SENTENCE; 2 AGGRAVATED ASSAULT 06/24/1975 HARRISON COUNTY, 5 Years; 3 HOMICIDE- 07/24/1998 HARRISON COUNTY, DEATH SENTENCE

Mississippi Department of Corrections (Media Kit)

Mississippi Department of CorrectionsState Death Row Inmate William J. Mitchell

MDOC #31271

Black Male

DOB – 07.04.1950

Factual Background of the Case

On November 21, 1995, James Hartley saw William Mitchell enter the Majik Mart on Popps Ferry Road in Biloxi, Mississippi, three separate times to visit Patty Milliken while she was working her shift. Hartley over-heard Milliken refer to Mitchell as "Jerry." When Milliken's shift ended that evening around 8:00 p.m., she and Hartley had yet to document the amount of cash they had placed in the safe that night. Milliken opened the safe and then telephoned her son that she would be home in fifteen minutes.

According to Hartley, Milliken walked out of the store with Mitchell to smoke a cigarette and told him (Hartley) that she would be right back. Ten minutes later, Hartley walked outside to ask Milliken a question, but she was not there. Her belongings were inside the store, and her car was in the parking lot.

When Milliken had still not returned by 10:00 p.m., Hartley telephoned the police. Hartley gave Milliken's purse to police and showed them where she had written Mitchell's phone number. The police cross referenced the telephone number to a physical address and proceeded to the address. The police arrived at the residence at approximately midnight and asked to speak to Mitchell. Mitchell ran, and the Biloxi Police Department issued an alert for Mitchell and his vehicle. A police officer later spotted Mitchell at a gas station on U.S. Highway 90. Mitchell again ran, and the police followed in pursuit.

Mitchell was eventually caught and arrested for traffic violations. His passenger testified that Mitchell had stated that he (Mitchell) "got that bitch." Patty Milliken's body was found the following morning under a bridge. She had been beaten, strangled, sexually assaulted both vaginally and anally, crushed by a car and mutilated.

There was testimony that she was still alive when the car ran over her. Comparison tests conducted indicated the tire casts from the area matched three of the four tires on Mitchell's car with regard to tread design and size. Police also found blood and hair on and under Mitchell's car.

Mitchell was charged with the capital murder of Milliken committed while being under a sentence of life in prison. On July 24, 1998, a jury found him guilty and sentenced him to death by lethal injection.

Execution by Lethal Injection

In 1998, the Mississippi Legislature amended Section 99-19-51, Mississippi Code of 1972, as follows: 99-19-51. The manner of inflicting the punishment of death shall be by continuous intravenous administration of a lethal quantity of an ultra short-acting barbiturate or other similar drug in combination with a chemical para-lytic agent until death is pronounced by the county coroner where the execution takes place or by a licensed physician according to accepted standards of medical practice.

Mississippi Death Row Demographics

Youngest on Death Row: Terry Pitchford, MDOC #117778, age 26

Oldest on Death Row: Richard Jordan, MDOC #30990, age 65

Longest serving Death Row inmate: Richard Jordan, MDOC #30990 (March 2, 1977: Thirty-Four Years)

Total Inmates on Death Row = 55

MALE:53

FEMALE: 2

WHITE:23

BLACK: 31

ASIAN: 1

Mississippi State Penitentiary

The Mississippi State Penitentiary (MSP) is Mississippi’s oldest of the state’s three institutions and is located on approximately 18,000 acres in Parchman, Miss., in Sunflower County. In 1900, the Mississippi Legislature appropriated $80,000 for the purchase of 3,789 acres known as the Parch-man Plantation. The Superintendent of the Mississippi State Penitentiary and Deputy Commissioner of Institutions is E.L. Sparkman. There are approximately 868 employees at MSP. MSP is divided into two areas: AREA WARDEN UNITS Area I - Warden Earnest Lee Unit 29 Area II - Warden Timothy Morris Units 25, 26, 28, 30, 31, and 42 The total bed capacity at MSP is currently 4,648. The smallest unit, Unit 42, houses 56 inmates and is the institution’s hospital. The largest unit, Unit 29, houses 1,561 minimum, medium, close-custody and Death Row inmates. MSP houses male offenders classified to all custody levels and Long Term Segregation and death row. All male offenders sentenced to death are housed at MSP. All female offenders sentenced to death are housed at the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility in Pearl, Miss. The majority of the farming activity involving Agricultural Enterprises takes place at MSP. Programs offered at MSP include alcohol and drug treatment, adult basic education, inmate legal assistance, pre-release, therapeutic recreation, religious/faith programs and vocational skills training. Mississippi Prison Industries operates a work program at the MSP and utilizes more than 296,400 inmate man-hours in its textile, metal fabrication and wood working shops. On a monthly average, 190 inmates work in these shops.

Lethal injection is the world’s newest method of execution. While the concept of lethal injection was first pro-posed in 1888, it was not until 1977 that Oklahoma became the first state to adopt lethal-injection legislation. Five years later in 1982, Texas performed the first execution by lethal injection. Lethal injection has quickly be-come the most common method of execution in the United States. Thirty-five of thirty-six states that have a death penalty use lethal injection as the primary form of execution. The U.S. federal government and U.S. mili-tary also use lethal injection. According to data from the U.S. Department of Justice, 41 of 42 people executed in the United States in 2007 died by lethal injection.

While lethal injection initially gained popularity as a more humane form of execution, in recent years there has been increasing opposition to lethal injection with opponents arguing that instead of being humane it results in an extremely painful death for the inmate. In September 2007 the United States Supreme Court agreed to hear the case of Baze v. Rees to determine whether or not Kentucky’s three drug-protocol for lethal injections amounts to cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment to the United State Constitution. As a result of the Supreme Court’s decision to hear this case, executions in the United States came to a brief halt in late September 2007. On April 16, 2008, the Supreme Court ruled in Baze holding that Kentucky’s three-drug protocol for administering lethal injections does not violate the Eighth Amendment. The result of this ruling was to lift the de facto moratorium on executions in the United States. The State of Georgia became the first state to carry out an execution since the Court’s Baze decision when William Earl Lynd was executed by lethal injection on May 6, 2008.

Chronological Sequence of Events of Execution

48 Hours Prior to Execution The condemned inmate shall be transferred to a holding cell.

24 Hours Prior to Execution Institution is placed in emergency/lockdown status.

1200 Hours Day of Execution Designated media center at institution opens.

1500 Hours Day of Execution Inmate’s attorney of record and chaplain allowed to visit.

1600 Hours Day of Execution Inmate is served last meal and allowed to shower.

1630 Hours Day of Execution MDOC clergy allowed to visit upon request of inmate.

1730 Hours Day of Execution Witnesses are transported to Unit 17.

1800 Hours Day of Execution Inmate is escorted from holding cell to execution room.

1800 Witnesses are escorted into observation room.

1900 Hours Day of Execution A post execution briefing is conducted with media witnesses.

2030 Hours Day of Execution Designated media center at institution is closed.

Death Row Executions

Since Mississippi joined the Union in 1817, several forms of execution have been used. Hanging was the first form of execution used in Mississippi. The state continued to execute prisoners sentenced to die by hanging until October 11, 1940, when Hilton Fortenberry, convicted of capital murder in Jefferson Davis County, became the first prisoner to be executed in the electric chair. Between 1940 and February 5, 1952, the old oak electric chair was moved from county to county to conduct execu-tions. During the 12-year span, 75 prisoners were executed for offenses punishable by death. In 1954, the gas chamber was installed at the Mississippi State Penitentiary, in Parchman, Miss. It replaced the electric chair, which today is on display at the Mississippi Law Enforcement Training Academy. Gearald A. Gallego became the first prisoner to be executed by lethal gas on March 3, 1955. During the course of the next 34 years, 35 death row inmates were executed in the gas cham-ber. Leo Edwards became the last person to be executed in the gas chamber at the Mississippi State Penitentiary on June 21, 1989.

On July 1, 1984, the Mississippi Legislature partially amended lethal gas as the state’s form of execu-tion in § 99-19-51 of the Mississippi Code. The new amendment provided that individuals who com-mitted capital punishment crimes after the effective date of the new law and who were subsequently sentenced to death thereafter would be executed by lethal injection. On March 18, 1998, the Mississippi Legislature amended the manner of execution by removing the provision lethal gas as a form of execution.

Mississippi State Penitentiary in Parchman, Mississippi

The Mississippi State Penitentiary (MSP) is Mississippi’s oldest of the state’s three institutions and is located on approximately 18,000 acres in Parchman, Miss., in Sunflower County. In 1900, the Mississippi Legislature appropriated $80,000 for the purchase of 3,789 acres known as the Parch-man Plantation. The Superintendent of the Mississippi State Penitentiary and Deputy Commissioner of Institutions is E.L. Sparkman. There are approximately 868 employees at MSP.

MSP is divided into two areas: AREA WARDEN UNITS - Area I - Warden Earnest Lee Unit 29, Area II - Warden Timothy Morris Units 25, 26, 28, 30, 31, and 42. The total bed capacity at MSP is currently 4,648. The smallest unit, Unit 42, houses 56 inmates and is the institution’s hospital. The largest unit, Unit 29, houses 1,561 minimum, medium, close-custody and Death Row inmates. MSP houses male offenders classified to all custody levels and Long Term Segregation and death row.

All male offenders sentenced to death are housed at MSP. All female offenders sentenced to death are housed at the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility in Pearl, Miss. The majority of the farming activity involving Agricultural Enterprises takes place at MSP. Programs offered at MSP include alcohol and drug treatment, adult basic education, inmate legal assistance, pre-release, therapeutic recreation, religious/faith programs and vocational skills training.

Mississippi Prison Industries operates a work program at the MSP and utilizes more than 296,400 inmate man-hours in its textile, metal fabrication and wood working shops. On a monthly average, 190 inmates work in these shops.

Death Row Executions

Since Mississippi joined the Union in 1817, several forms of execution have been used. Hanging was the first form of execution used in Mississippi. The state continued to execute prisoners sentenced to die by hanging until October 11, 1940, when Hilton Fortenberry, convicted of capital murder in Jefferson Davis County, became the first prisoner to be executed in the electric chair. Between 1940 and February 5, 1952, the old oak electric chair was moved from county to county to conduct execu-tions. During the 12-year span, 75 prisoners were executed for offenses punishable by death.

In 1954, the gas chamber was installed at the Mississippi State Penitentiary, in Parchman, Miss. It replaced the electric chair, which today is on display at the Mississippi Law Enforcement Training Academy. Gearald A. Gallego became the first prisoner to be executed by lethal gas on March 3, 1955. During the course of the next 34 years, 35 death row inmates were executed in the gas cham-ber. Leo Edwards became the last person to be executed in the gas chamber at the Mississippi State Penitentiary on June 21, 1989.

On July 1, 1984, the Mississippi Legislature partially amended lethal gas as the state’s form of execu-tion in § 99-19-51 of the Mississippi Code. The new amendment provided that individuals who com-mitted capital punishment crimes after the effective date of the new law and who were subsequently sentenced to death thereafter would be executed by lethal injection. On March 18, 1998, the Mississippi Legislature amended the manner of execution by removing the provision lethal gas as a form of execution.

INMATES EXECUTED IN THE MISSISSIPPI GAS CHAMBER

Name Race-Sex Offense Date Executed

Gerald A. Gallego White Male Murder 03-03-55

Allen Donaldson Black Male Armed Robbery 03-04-55

August Lafontaine White Male Murder 04-28-55

John E. Wiggins White Male Murder 06-20-55

Mack C. Lewis Black Male Murder 06-23-55

Walter Johnson Black Male Rape 08-19-55

Murray G. Gilmore White Male Murder 12-09-55

Mose Robinson Black Male Rape 12-16-55

Robert Buchanan Black Male Rape 01-03-56

Edgar Keeler Black Male Murder 01-27-56

O.C. McNair Black Male Murder 02-17-56

James Russell Black Male Murder 04-05-56

Dewey Towsel Black Male Murder 06-22-56

Willie Jones Black Male Murder 07-13-56

Mack Drake Black Male Rape 11-07-56

Henry Jackson Black Male Murder 11-08-56

Minor Sorber White Male Murder 02-08-57

Joe L. Thompson Black Male Murder 11-14-57

William A. Wetzell White Male Murder 01-17-58

J.C. Cameron Black Male Rape 05-28-58

Allen Dean, Jr. Black Male Murder 12-19-58

Nathaniel Young Black Male Rape 11-10-60

William Stokes Black Male Murder 04-21-61

Robert L. Goldsby Black Male Murder 05-31-61

J.W. Simmons Black Male Murder 07-14-61

Howard Cook Black Male Rape 12-19-61

Ellic Lee Black Male Rape 12-20-61

Willie Wilson Black Male Rape 05-11-62

Kenneth Slyter White Male Murder 03-29-63

Willie J. Anderson Black Male Murder 06-14-63

Tim Jackson Black Male Murder 05-01-64

Jimmy Lee Gray White Male Murder 09-02-83

Edward E. Johnson Black Male Murder 05-20-87

Connie Ray Evans Black Male Murder 07-08-87

Leo Edwards Black Male Murder 06-21-89

PRISONERS EXECUTED BY LETHAL INJECTION

Name Race-Sex Offense Date Executed

Tracy A. Hanson White Male Murder 07-17-02

Jessie D. Williams White Male Murder 12-11-02

John B. Nixon, Sr. White Male Murder 12-14-05

Bobby G. Wilcher White Male Murder 10-18-06

Earl W. Berry White Male Murder 05-21-08

Dale L. Bishop White Male Murder 07-23-08

Paul E. Woodward White Male Murder 05-19-10

Gerald J. Holland White Male Murder 05-20-10

Joseph D. Burns White Male Murder 05-20-10

Benny Joe Stevens White Male Murder 05-10-11

Rodney Gray Black Male Murder 05-17-11

Edwin Hart Turner White Male 02/08/2012

Source: Mississippi Department of Corrections, Mississippi State Penitentiary

"State Executes William Mitchell," by R.L. Nave. (March 23, 2012)

William Mitchell was already affixed to the metal table with thick, heavy, tan leather straps when prison guards escorted witnesses into the execution viewing rooms at Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman. Dressed in a red jumpsuit and surprisingly clean black and white sneakers--MSP's version of Converse's All-Star--Mitchell's bulky 6-foot-1-inch frame filled every available inch of the gurney that was bolted to the floor. Underneath the slab, curiously, sat a small, wooden step stool.

His hair cut short, a small tuft of gray hair on his chin, Mitchell stared blankly at the ceiling above him, not once shooting a glance in the direction of any of the five people standing just feet from him in the cramped chamber. The officials--one woman and four men, including MDOC Commissioner Christopher Epps--did not look at Mitchell or at each other. Just after 6 o'clock, as the sun set outside, one of the male officials flipped on a microphone mounted above Mitchell's face and asked the condemned if he wished to make a last statement. "No," he said, defiantly. The official stepped back and a tube originating from a separate room began to sway gently as pentobarbital (an anesthetic), Pavulon (a muscle relaxer), and potassium chloride (which causes cardiac arrest) pumped into Mitchell's arms, extended and taped to extensions on the gurney.

He took a few quick breaths, his huge chest expanding several times, and he let out an unusual sounding yawn. His bottom jaw protruded from his face in an unnatural way for a just a second before he relaxed. His eyes closed, and the 62-year-old man didn't move again. Another 10 or 15 minutes of silence--both in the execution chamber and in the condemned's witness room--followed before prison officials pronounced Mitchell dead at 6:20 p.m.

Two of Mitchell's attorneys, Glenn Swartzfager and Louwlynn Vanzetta Williams, consoled one another with mere glances. When it was over, corpse directors from Brinson Funeral Home in Cleveland loaded Mitchell's body into a white SUV parked immediately outside the death chamber.

A judge sentenced Mitchell to death in 1998 for the capital murder of Patty Milliken in Biloxi. Milliken, a store clerk at Majik Mart, left to have a cigarette with Mitchell at the end of her shift on November 21, 1995, according to information from the MDOC. Milliken's co-worker called the police when she did not return to the market where she had left her belongings. When police arrived at Mitchell's home to ask about Milliken's whereabouts, he ran. A police officer spotted Mitchell later at a gas station, and he ran again.

Police eventually captured Mitchell, who was out on parole at the time for a murder and aggravated assault committed in 1975. Milliken's body was found a day later under a bridge. She had been beaten, strangled, vaginally and anally assaulted, crushed by a car and mutilated. A passenger of Mitchell's told police that Mitchell, referring to Milliken, said he "got that bitch."

Epps, MDOC commissioner, said yesterday that he asked Mitchell several times on the day of his execution to talk about the incident. "If you hadn't done anything, would you say anything?" was Mitchell's response, Epps said. Throughout the day, MDOC held press briefings for the three reporters who signed up to witness the execution. Reporters received details of Mitchell's final day, such as who he called on the telephone (six people in all, including his daughter), if he showered and the contents of his last meals. For breakfast, it was potatoes and beef gravy, biscuits, dry cereal, milk and coffee, which he did not finish. For his final meal (he declined lunch), Mitchell ordered a "big plate of fried shrimp and oysters, big strawberry shake, cup of Ranch dressing, two fried chicken breasts and a Coke." He ate very little, Epps said, which is unusual in the 18 executions he's overseen.

Members of Milliken's family, including her son, Will Burns, who was a child when she died, read statements. Burns remembered walks on the beach and drives along Highway 90 to admire beautiful homes. He said that he is disappointed that "a beautiful lady's name will forever be tied to a disgusting man." "In this moment, I am very angry at the system, at this man, and at the fact that the process took close to 17 years to come to fruition," Burns said. "Do I feel justice was served? I would have to say only slightly. Sure, the state of Mississippi took his life. He lived in a cage like an animal for the last 17 years, but we all paid to keep him there."

On Tuesday, March 22, the state also executed Larry Matthew Puckett. In August 1996, Puckett received a death sentence for the murder, rape and sexual battery of Rhonda Griffis, his former boss' wife.

The last time that Patty Milliken was seen alive was at the conclusion of her shift at 8:00 p.m., November 21, 1995, at the Majik Mart on Popps Ferry Road in Biloxi, Mississippi. She told her co-worker, James Leland Hartley, that she was going outside to smoke and talk to William Gerald Mitchell and that she would return shortly. Before following Mitchell outside, she telephoned her son, telling him she would be home in approximately fifteen minutes. She also left her keys in the safe to initiate a 10-minute time-released unlock and her purse and other personal items on the counter. Patty Milliken's body was found the following morning under a bridge. She had been beaten, strangled, sexually assaulted, crushed by being driven over, and mutilated.The record shows that on November 21, 1995, Hartley saw Mitchell enter the store three separate times to visit Milliken while she was working her shift. Hartley overheard Milliken refer to Mitchell by the name of "Jerry." At the end of Milliken's shift that evening, around 8:00 p.m., Milliken and Hartley realized that they had forgotten to document the amount of cash they had placed in the safe that night. Milliken opened the safe and telephoned her son that she would be home in fifteen minutes. At approximately 8:05 p.m. Milliken decided to walk out of the store with Mitchell and told Hartley that "she'd be outside smoking a cigarette if [Hartley] needed her and that she'd be right back." Milliken left her keys in the lock on the safe, cigarettes and lighter on one counter, and her purse on another counter. Hartley testified that it was odd for Milliken to go outside to smoke because employees were authorized to smoke inside the store. Ten minutes after Milliken had gone outside, Hartley walked outside to ask her a question, but she was not there. Her belongings were still inside the store, and her car remained in the parking lot. Hartley telephoned Milliken's home and learned that she had not been in contact with her family. When Milliken had still not returned by 10:00 p.m., Hartley telephoned the police.

When the police arrived, Hartley gave them Milliken's purse and showed them where she had written Jerry's phone number. The police cross-referenced the telephone number to a physical address, and proceeded to the house on Croesus Street. The police arrived at the residence at approximately midnight. Officers Matory and Doucet went to the front door, and Officer McKaig "was on the right side of the house approaching the rear." McKaig saw Mitchell, and Mitchell asked, "Who's that?" McKaig identified himself as a police officer and explained that he wanted to speak to him. Mitchell ran, and a pursuit on foot followed. Captain Anderson responded to assist with the foot pursuit. Captain Patterson, arriving to assist with the foot pursuit, spoke with Booker Gatlin, Mitchell's grandfather and owner of the residence on Croesus Street. Gatlin indicated that "Jerry" was William Gerald Mitchell, and that he drove a blue Grand Am.

When the foot pursuit proved unsuccessful, the Biloxi Police Department issued a be-on-the-lookout ("BOLO") for Mitchell and his vehicle. Shortly thereafter, an officer spotted Mitchell getting gas at a Shell station located on U.S. Highway 90. When Mitchell noticed the police car, he threw down the gas nozzle he was using and sped away in his vehicle. Patrolman Sonnier took part in the pursuit of Mitchell. That evening he had a television camera crew riding with him, and they were able to film most of the pursuit. Sonnier testified that Mitchell was the driver of the vehicle and that Curtis Pearson was his passenger. The high-speed chase ended in Mitchell being arrested for various traffic violations.

Mitchell's passenger, Pearson, testified that, during the chase, Mitchell stated 2-3 times that he "got that bitch." Officer Heard of the Biloxi Police Department discovered the mutilated, almost naked body of Patty Milliken under the Popps Ferry Bridge at 7:14 a.m. the following morning. Officer Robert Burriss arrived at the scene at approximately 7:30 a.m., and worked the scene until 2:00 p.m. Burriss testified that he found Patty's body on its back. She had part of a shirt sleeve around her right arm and part of her bra around her left arm, with only a pair of white socks clothing her body. Her body was bruised and scraped, and her head was "burst open" with the brains "spilling out of the skull, scattered about on the yard, and there was also some of the brain matter stuck on her back."

There were "numerous" tire tracks "back and forth all over that area;" tracks that were similar to the ones found on Milliken's body. Testing would ultimately show that the tire casts from the area matched three of the four tires on Mitchell's car with regard to tread design, size and "overall width." Later that day, pursuant to a search warrant, Burriss also collected evidence from Mitchell's car. Burriss made a diagram of the car indicating where he found "various pieces of blood and hair on the automobile." Burriss found hair and blood on the passenger door; blood underneath the fender and body of the car, as well as on the catalytic converter; and blood spatters in three of the wheel wells. Patty's broken lower dentures were also found in Mitchell's car. After Mitchell's arrest for traffic violations, he was taken to the Biloxi Police Department.

Mitchell was initially interviewed by Sergeant Torbert and Investigator Thompson. Later, Officers Newman and Peterson interviewed Mitchell at 1:07 p.m. on November 22, 1995, the same day Patty Milliken's body was found. At the time of this second interview, Mitchell had not been arrested or charged with murder, but was in custody for the traffic violations. Mitchell said that he was the only one to use his vehicle that night. Mitchell claimed that Patty was alive when he left her, though he did admit that he had hit her hard enough in the nose that "blood just flew everywhere." A redacted version of Mitchell's second interview was admitted during the trial. The tape was edited and redacted at the point before Mitchell made any statement that he killed or was responsible for the death of Patty Milliken.

After Mitchell's second interview, Mitchell was booked on the charge of murder and transported to the Harrison County Jail. Prior to his transfer, a suspect rape kit was performed on Mitchell at the Biloxi Regional Medical Center. Later, search warrants were secured and executed on Mitchell, Mitchell's car, and Mitchell's residence at 323 Croesus Street in Biloxi. Dr. Paul McGarry performed the autopsy on Patty Milliken's body.

According to McGarry, Patty was strangled, beaten, sexually assaulted, and repeatedly run over by a vehicle. McGarry stated that the damage to the larynx cartilages and hemorrhagic airway proved that she had been strangled. There were also semicircular marks from her attacker's fingernails on her neck. She was beaten to the point that her lower denture was broken and expelled. Her face was swollen and purple which "would evidence that hard blows had been delivered to the head." Analysis of the genital area displayed "the kind of injuries that are produced by stretching and tearing of the delicate lining of the vagina" which McGarry "interpreted as forceful penetration enough to damage the tissue and tear and rub off surfaces of the tissue, to stretch the opening. The anus was even more so damaged." McGarry confirmed that Patty Milliken's sexual injuries occurred while she was still alive. McGarry also testified to finding five tire tracks across the victim's body. According to McGarry, Patty Milliken apparently lived long enough to experience the crushing injuries that ruptured her kidney, liver, and spleen; broke almost every rib; broke her spine; broke her collarbone; and, tore open her lungs and heart vessels. Patty Milliken was killed when her "brain [was] blown out by crushing and squashed out." The brain was expelled up to four feet from an opening at the top of her head measuring eight inches in diameter.

At the time of Patty's savage murder, Mitchell had been paroled for approximately eleven months from a sentence of life in prison for murder.

The Silent Voices of Mississippi

THE SILENT VOICES OF MISSISSIPPI: Justice For William MitchellWilliam Mitchell is expecting a execution to be set any time. Once the state gets a date set it is carried out within 30 days. William Mitchell is one of the men named in the Knox Lawsuit, who deceive inadequate counsel.

KNOX V. MISSISSIPPI Justia.com Opinion Summary: In 2010, sixteen death-sentenced inmates, including Steve Knox (the inmates), filed a complaint in the Chancery Court. The essence of their complaint was that due to defects in both the statutory structure and the performance of the Mississippi Office of Capital Post-Conviction Counsel (MOCPCC), they were deprived of their right to obtain meaningful state post-conviction and federal habeas corpus review of their convictions and death sentences. The inmates requested injunctive relief against the State due to alleged violations of their rights to competent, appointed, post-conviction counsel. The State moved to dismiss for lack of jurisdiction. After a hearing, the chancery court found that it lacked subject matter jurisdiction over the complaint because the inmates' "attack on the death sentences and post-conviction judicial reviews of [their] convictions" was cognizable under the Uniform Post-Conviction Collateral Relief Act (UPCCRA). The chancery court dismissed the complaint. Upon review, the Supreme Court affirmed, finding the chancery court lacked jurisdiction over the inmates claims because the claims were embraced by the UPCCRA.

PLEASE SIGN AND SHARE

Mitchell v. State, 792 So.2d 192 (Miss. 2001). (Direct Appeal)

Defendant was convicted in the Circuit Court, Harrison County, Kosta N. Vlahos, J., of capital murder and was sentenced to death by lethal injection. He appealed. The Supreme Court, Pittman, C.J., held that: (1) in a matter of first impression, the issuance of a second indictment before a nolle prosequi of the first indictment was not a double jeopardy violation; (2) investigating police officer did not trespass on defendant's property; (3) defendant's right to a speedy trial was not violated; and (4) death sentence was not disproportionate when compared to similar cases. Affirmed.

EN BANC.

PITTMAN, C.J., for the Court:

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

¶ 1. William Gerald Mitchell was originally indicted as a habitual offender on July 25, 1996, by the Grand Jurors of the Second Judicial District of Harrison County for the November 21, 1995, capital murder of Patty Milliken, while Mitchell was under a sentence of life imprisonment, in violation of Miss.Code Ann. § 97–36–19(2)(e). On July 21, 1998, the trial judge granted a nolle prosequi for the indictment due to an error contained within the indictment.

¶ 2. On April 29, 1998, William Gerald Mitchell was indicted as a habitual offender by the Grand Jurors of the Second Judicial District of Harrison County for the November 21, 1995, capital murder of Patty Milliken, while Mitchell was under a sentence of life imprisonment, in violation of Miss.Code Ann. § 97–36–19(2)(b). Mitchell was arraigned and pled not guilty on June 4, 1998.

¶ 3. On July 23, 1998, the jury found Mitchell guilty of capital murder. A hearing regarding Mitchell's status as a habitual offender was held, and the trial judge ruled that Mitchell was a habitual offender. The sentencing hearing was held July 23, 1998, where the jury imposed the death penalty. The trial court stayed Mitchell's execution. Mitchell's post-trial motions were denied in November, 1998. Mitchell appeals, raising twelve issues for consideration by this Court.

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

¶ 4. The last time that Patty Milliken was seen alive was at the conclusion of her shift at 8:00 p.m., November 21, 1995, at the Majik Mart on Popps Ferry Road in Biloxi, Mississippi. She told her co-worker, James Leland Hartley, that she was going outside to smoke and talk to William Gerald Mitchell and that she would return shortly. Before following Mitchell outside, she telephoned her son, telling him she would be home in approximately fifteen minutes. She also left her keys in the safe to initiate a 10–minute time-released unlock and her purse and other personal items on the counter. Patty Milliken's body was found the following morning under a bridge. She had been beaten, strangled, sexually assaulted, crushed by being driven over, and mutilated.

¶ 5. The record shows that on November 21, 1995, Hartley saw Mitchell enter the store three separate times to visit Milliken while she was working her shift. Hartley overheard Milliken refer to Mitchell by the name of “Jerry.” At the end of Milliken's shift that evening, around 8:00 p.m., Milliken and Hartley realized that they had forgotten to document the amount of cash they had placed in the safe that night. Milliken opened the safe and telephoned her son that she would be home in fifteen minutes. At approximately 8:05 p.m. Milliken decided to walk out of the store with Mitchell and told Hartley that “she'd be outside smoking a cigarette if [Hartley] needed her and that she'd be right back.”

¶ 6. Milliken left her keys in the lock on the safe, cigarettes and lighter on one counter, and her purse on another counter. Hartley testified that it was odd for Milliken to go outside to smoke because employees were authorized to smoke inside the store. Ten minutes after Milliken had gone outside, Hartley walked outside to ask her a question, but she was not there. Her belongings were still inside the store, and her car remained in the parking lot. Hartley telephoned Milliken's home and learned that she had not been in contact with her family. When Milliken had still not returned by 10:00 p.m., Hartley telephoned the police.

¶ 7. When the police arrived, Hartley gave them Milliken's purse and showed them where she had written Jerry's phone number. The police cross-referenced the telephone number to a physical address, and proceeded to 323 Croesus Street. The police arrived at the residence at approximately midnight.

¶ 8. Officers Matory and Doucet went to the front door, and Officer McKaig “was on the right side of the house approaching the rear.” McKaig saw Mitchell, and Mitchell asked, “Who's that?” McKaig identified himself as a police officer and explained that he wanted to speak to him. Mitchell ran, and a pursuit on foot followed.

¶ 9. Captain Anderson responded to assist with the foot pursuit. Captain Patterson, arriving to assist with the foot pursuit, spoke with Booker Gatlin, Mitchell's grandfather and owner of the residence on Croesus Street. Gatlin indicated that “Jerry” was William Gerald Mitchell, and that he drove a blue Grand Am.

¶ 10. When the foot pursuit proved unsuccessful, the Biloxi Police Department issued a be-on-the-lookout (“BOLO”) for Mitchell and his vehicle. Shortly thereafter, an officer spotted Mitchell getting gas at a Shell station located on U.S. Highway 90. When Mitchell noticed the police car, he threw down the gas nozzle he was using and sped away in his vehicle. Patrolman Sonnier took part in the pursuit of Mitchell. That evening he had a television camera crew riding with him, and they were able to film most of the pursuit. Sonnier testified that Mitchell was the driver of the vehicle and that Curtis Pearson was his passenger. The high-speed chase ended in Mitchell being arrested for various traffic violations. Mitchell's passenger, Pearson, testified that, during the chase, Mitchell stated 2–3 times that he “got that bitch.”

¶ 11. Officer Heard of the Biloxi Police Department discovered the mutilated, almost naked body of Patty Milliken under the Popps Ferry Bridge at 7:14 a.m. the following morning. Officer Robert Burriss arrived at the scene at approximately 7:30 a.m., and worked the scene until 2:00 p.m. Burriss testified that he found Milliken's body on its back. She had part of a shirt sleeve around her right arm and part of her bra around her left arm, with only a pair of white socks clothing her body. Her body was bruised and scraped, and her head was “burst open” with the brains “spilling out of the skull, scattered about on the yard, and there (sic) was also some of the brain matter stuck on her back.”

¶ 12. There were “numerous” tire tracks “back and forth all over that area;” tracks that were similar to the ones found on Milliken's body. Testing would ultimately show that the tire casts from the area matched three of the four tires on Mitchell's car with regard to tread design, size and “overall width.”

¶ 13. Later that day, pursuant to a search warrant, Burriss also collected evidence from Mitchell's car. Burriss made a diagram of the car indicating where he found “various pieces of blood and hair on the automobile.” Burriss found hair and blood on the passenger door; blood underneath the fender and body of the car, as well as on the catalytic converter; and blood spatters in three of the wheel wells. Milliken's broken lower dentures were also found in Mitchell's car.

¶ 14. After Mitchell's arrest for traffic violations, he was taken to the Biloxi Police Department. Mitchell was initially interviewed by Sergeant Torbert and Investigator Thompson. Later, Officers Newman and Peterson interviewed Mitchell at 1:07 p.m. on November 22, 1995, the same day Milliken's body was found. At the time of this second interview, Mitchell had not been arrested or charged with murder, but was in custody for the traffic violations. Mitchell said that he was the only one to use his vehicle that night. Mitchell claimed that Milliken was alive when he left her, though he did admit that he had hit her hard enough in the nose that “blood just flew everywhere.” A redacted version of Mitchell's second interview was admitted during the trial. The tape was edited and redacted at the point before Mitchell made any statement that he killed or was responsible for the death of Milliken.

¶ 15. After Mitchell's second interview, Mitchell was booked on the charge of murder and transported to the Harrison County Jail. Prior to his transfer, a suspect rape kit was performed on Mitchell at the Biloxi Regional Medical Center. Later, search warrants were secured and executed on Mitchell, Mitchell's car, and Mitchell's residence at 323 Croesus Street in Biloxi.

¶ 16. Dr. Paul McGarry performed the autopsy on Milliken's body. According to McGarry, Milliken was strangled, beaten, sexually assaulted, and repeatedly run over by a vehicle. McGarry stated that the damage to Milliken's larynx cartilages and hemorrhagic airway proved that she had been strangled. There were also semicircular marks from her attacker's fingernails on her neck. She was beaten to the point that her lower denture was broken and expelled. Her face was swollen and purple which “would evidence that hard blows had been delivered to the head.” Analysis of the genital area displayed “the kind of injuries that are produced by stretching and tearing of the delicate lining of the vagina” which McGarry “interpreted as forceful penetration enough to damage the tissue and tear and rub off surfaces of the tissue, to stretch the opening. The anus was even more so damaged.” McGarry confirmed that Milliken's sexual injuries occurred while she was still alive.

¶ 17. McGarry also testified to finding five tire tracks across the victim's body. According to McGarry, Milliken apparently lived long enough to experience the crushing injuries that ruptured her kidney, liver, and spleen; broke almost every rib; broke her spine; broke her collarbone; and, tore open her lungs and heart vessels. Milliken was killed when her “brain [was] blown out by crushing and squashed out.” The brain was expelled up to four feet from an opening at the top of her head measuring eight inches in diameter.

¶ 18. At the time of Milliken's savage murder, Mitchell had been paroled for approximately eleven months from a sentence of life in prison for murder.

DISCUSSION

I. CAN AN INDICTMENT BE RETURNED AGAINST A DEFENDANT WHILE A PRIOR INDICTMENT CHARGING THE SAME OFFENSE IS STILL ACTIVE AND PENDING?

¶ 19. On July 25, 1996, William Gerald Mitchell was indicted as a habitual offender by the Grand Jurors of the Second Judicial District of Harrison County for the November 21, 1995, capital murder of Patty Milliken, while Mitchell was under a sentence of life imprisonment, in violation of Miss.Code Ann. § 97–3–19(2)(e). At a hearing held November 13, 1997, the trial judge noted a scrivener's error in the indictment in that Mitchell had been charged under the wrong subsection of the capital murder statute. This first indictment, Cause No. 96–263, while specifically citing Miss.Code Ann. § 97–3–19(2)(b) in its heading, referred to the felony-murder section of the Miss.Code § 97–3–19(2)(e) and contained language “with or without deliberate design.” The trial judge commented that “it ought to be cleaned up if it is a Scribner's [sic] error.” Subsequently, on April 29, 1998, William Gerald Mitchell, a/k/a William Jerald Mitchell, was indicted as a habitual offender by the Grand Jurors of the Second Judicial District of Harrison County for the November 21, 1995, capital murder of Patty Milliken, while under a sentence of life imprisonment, in violation of Miss.Code Ann. § 97–3–19(2)(b).

¶ 20. On July 21, 1998, the trial court granted a motion by the State to nolle prosequi the first indictment. This nolle prosequi came about as a result of defense counsel making a motion to dismiss Mitchell's second indictment, Cause No. 98–195, because the first indictment, Cause No. 96–263, was still active and pending. This motion was made immediately after the jury was impaneled and sworn in. The trial judge denied the defense's motion to dismiss. It was after the motion was denied that the State made an ore tenus motion to nolle prosequi the first indictment, which, against opposition of defense counsel, was granted.

¶ 21. After the motion to nolle prosequi was granted, the district attorney stated:

And we further would say to the record that that is the same case and all material points, some name's changed and better tracks the statute as the present—that the case that we're involved in today B–2402–98–00195, being the capital murder indictment against William Gerald Mitchell a/k/a William Jerald Mitchell which was filed on April 29th, 1998. And the defense has been—was made aware of it at that time, and in fact all-I'll say this to make clear in the record, there was no confusion no disadvantage to the defense by the action that was taken because all of their motions since that time, all the correspondence since that time, all of the record entries since that time, not only by the prosecution but by the defense starting with its filing on June 3rd, 1998, have been with the current number, the number under which we proceed today, as announced by the Court numerous times.

¶ 22. Mitchell contends that the trial court erred in denying his motion to dismiss the second indictment at a time when the first indictment was still pending and had not been nolle prosequi or dismissed. Mitchell asserts that the grand jury should not have been allowed to consider or return the second indictment against him while his first indictment was still active and pending.

¶ 23. The State maintains that because there was a nolle prosequi of the first indictment, the trial that ensued under the second indictment was proper.

¶ 24. Whether a second indictment on a charge contained within the first indictment can be returned against a defendant while the first indictment is active and pending is a matter of first impression for this Court. However, Wilson v. State, 574 So.2d 1324, 1332 (Miss.1990), supports the proposition that there is no double jeopardy violation when a second indictment is returned by a grand jury, and then the prosecution successfully moves the court to enter a nolle prosequi motion regarding the first indictment. The first indictment in Wilson resulted in a mistrial when the jury could not agree on a verdict. The defense filed a motion to quash the second indictment alleging that Wilson was facing double jeopardy, which was denied. Id. The difference between Wilson and the case at hand is that in Wilson, the prosecution had secured a court order granting the nolle prosequi for the first indictment prior to the second trial, while in the instant case Mitchell actually had two active indictments pending against him after the jury had been impaneled, and opening statements by the State had been made. The trial was in progress when Mitchell's counsel was allowed to make the motion to dismiss, although it appears from the record that Mitchell's counsel attempted to make the motion before the State's opening statements began. The trial judge decided to hear the motion when the jury had gone to lunch.

¶ 25. What must be determined is whether Mitchell actually incurred any harm from having simultaneous indictments against him. Was Mitchell subjected to multiple prosecutions in this case, and was he aware of the grounds for the prosecution against him? The record indicates that he suffered no harm by having the simultaneous indictments. The fact that defense counsel submitted motions and requests for discovery to the court with the cause number from the second indictment shows that there was an awareness that the State was pursuing prosecution under the second indictment. However, it should be noted that during this time period Mitchell also submitted, pro se, several motions that were duplicative in nature to what his counsel had submitted, and that these referenced the cause number from the first indictment.

¶ 26. Also, Mitchell was subject to only one prosecution, only one trial. In Warren v. State, 709 So.2d 415, 418 (Miss.1998), this Court ruled that there was not a double jeopardy violation when a trial was aborted because a witness's testimony for the prosecution did not support the elements set out in the indictment and the defendant was subsequently re-indicted. Mitchell argues that because the State was barred in Warren from charging the same offense in Count II on the basis that it violated double jeopardy, the same should apply in the present case. Mitchell is incorrect in this assertion. Mitchell was not subjected to an actual trial or even an “aborted” trial, as was the case in Warren. Instead Mitchell attempted to make his motion before opening statements began; was told by the Judge that his motion would be reserved until the jury had gone to lunch; and then made his motion to dismiss before the prosecution had even called its first witness.

¶ 27. Any error from the issuance of the second indictment before nolle prosequi of the first indictment occurred was clearly harmless. This issue is without merit.

II. DID THE TRIAL COURT ERR WHEN IT ALLOWED THE PROSECUTION TO AMEND THE INDICTMENT?

¶ 28. During motions that were heard on June 4, 1998, the State realized that it had failed to include two felony convictions for assault and battery with intent to maim, which Mitchell had previously been sentenced to five years in prison, in the indictment. The trial judge asked for a written motion from the State, and authorized defense counsel to respond to the proposed amendment. The prosecution filed its motion to amend the indictment with the circuit clerk on June 8, 1998. The trial judge granted the amendment with an order indicating that the indictment was amended pursuant to an ore tenus motion from the State's prosecutor.

¶ 29. Mitchell contends that the trial court erred in signing an order allowing the State to amend the indictment without allowing the defense to respond. Mitchell asserts that he was denied his right to due process when not afforded the opportunity to be heard regarding the motion.

¶ 30. Mitchell, in his reply brief, maintains that the discussion regarding the proposed amendment held on June 4, 1998, did not constitute notice that the State was going to amend the indictment. Mitchell also asserts that the State's motion to amend indictment was not noticed to him and that a certificate of service was not provided to Mitchell or his attorneys. The record does not contain a certificate of service showing that Mitchell or his counsel were presented with a copy of this motion. Mitchell believes that this is a violation of Rule 2.06 of the Uniform Circuit and County Court rules which states as follows:

Unless otherwise ordered by the court, all pleadings, motions, or applications to the court, except the initial pleading or indictment, must be served by any form of service authorized by Rule 5 of the Mississippi Rules of Civil Procedure on all attorneys of record for the parties, or on the parties when not represented by an attorney, and the person filing same shall also file an original certificate of service certifying that a correct copy has been provided to the attorneys or to the parties, the manner of service, and to whom it was served. Except as allowed by this rule or allowed by the court for good cause shown, the clerk may not accept for filing any document which is not accompanied by a certificate of service.

U.R.C.C.C. 2.06. Mitchell contends that the fact that the court order was signed on June 4, 1998 but not entered until June 18, 1998, combined with the absence of a signature for Mitchell's counsel, shows that he was not given notice or permission to respond to the proposed amendment. Mitchell asserts that he should have, in the least, been arraigned on the new amended indictment.

¶ 31. The State claims that the indictment was properly amended to charge Mitchell as a habitual offender under Rule 7.09 of the Uniform Circuit and County Court Rules, which provides as follows:

All indictments may be amended as to form but not as to the substance of the offense charged. Indictments may also be amended to charge the defendant as an habitual offender or to elevate the level of offense where the offense is one which is subject to enhanced punishment for subsequent offenses and the amendment is to assert prior offenses justifying such enhancement (e.g., driving under the influence, Miss.Code Ann. § 63–11–30). Amendment shall be allowed only if the defendant is afforded a fair opportunity to present a defense and is not unfairly surprised.

U.R.C.C.C. 7.09. The State contends that Mitchell cannot claim he was unfairly surprised by the addition of his other convictions to the indictment because Mitchell was charged with capital murder as a habitual offender from the very outset of the case. Burrell v. State, 726 So.2d 160, 162 (Miss.1998), noted that “although 7.09 does authorize amendments to charge the defendant as an habitual offender under § 99–19–83, this Court held in Nathan v. State, 552 So.2d 99, 106–07 (Miss.1989) that § 99–19–83 only affects sentencing and does not affect the substance of the offense charged.” Evans v. State, 725 So.2d 613, 681 (Miss.1997), holds that “the test for determining whether an indictment will prejudice the defendant's case is ‘whether a defense as it originally stood would be equally available after the amendment is made.’ ” (quoting Griffin v. State, 540 So.2d 17, 21 (Miss.1989)).

[2] ¶ 32. While the amendment to the indictment may not have been correctly made in terms of procedure, it certainly did not place Mitchell in any worse position than before the amendment was made. It only served to add convictions which in no way changed the substance of the indictment. Gray v. State, 605 So.2d 791, 793 (Miss.1992) states that “habitual offender status is not a crime, in and of itself, but merely a status which, if proven, will enhance the sentence imposed for the conviction of the offense.” In the present case we are not considering an amended indictment that was being made to lift the defendant to the level of “habitual offender.” Instead we see a situation where a prosecutor sought to correct an omission of two felonies that should have been included in the original indictment. The court's error in not allowing the defense to respond is harmless, rendering this issue without merit.

III. DID THE TRIAL COURT ERR IN REFUSING TO GRANT DEFENDANT'S MOTION FOR A SPECIAL VENIRE, AND/OR, TO GRANT A CONTINUANCE TO THE DEFENDANT?

¶ 33. Mitchell's counsel, before trial, filed a motion for special venire. The trial judge was notified of the request during the June 4, 1998, court hearing. Mitchell's counsel announced to the trial judge that he would either file a withdrawal or pursue the motion on June 8, 1998, upon which the trial judge reserved the motion. Approximately 2–3 weeks before trial, the trial judge instructed his court administrator to contact defense counsel to determine the status of the request for a special venire.

¶ 34. On June 17, 1998, a motion for continuance was discussed, during which the defendant's motion for special venire was ruled upon. Defense counsel acknowledged at the motion for continuance that he had informed the court administrator that the special venire request would be waived. Defense counsel then explained to the trial judge that subsequent to counsel's waiving of special venire, Mitchell was insisting that he have a special venire for his case. The trial court ruled that the demand for special venire was untimely and that Mitchell had waived his right to demand a special venire.

¶ 35. Mitchell now argues that a continuance should have been granted by the trial court for the purpose of summoning a special venire. Mitchell believes that because he did not personally agree to the withdrawal of the request for special venire that the withdrawal was not valid. Mitchell fails to cite any authority for this proposition causing consideration of this issue to be procedurally barred. Holland v. State, 705 So.2d 307, 329 (Miss.1997).

[4] [5] [6] ¶ 36. In addition, this issue is without merit. Any person charged with a capital crime, or with the crime of manslaughter, that has been arraigned and has entered a plea of not guilty is entitled to a special venire upon demand. Miss.Code Ann. § 13–5–77 (Supp.2000). The standard of review regarding a denial of a motion for a special venire comes from Davis v. State, 684 So.2d 643, 650 (Miss.1996), which states, “this Court will not overrule the lower court's denial of a motion for special venire except upon a showing of abuse of discretion.” The movant for special venire must make the request for special venire in a timely fashion. Id. (citing Williams v. State, 590 So.2d 1374 (Miss.1991)). It is also the responsibility of the movant to bring the motion to the attention of the trial court, otherwise the issue will be considered waived. Billiot v. State, 454 So.2d 445, 456 (Miss.1984).

¶ 37. In the present case, the trial judge did not abuse his discretion when he determined that the motion for special venire was untimely and that the right to demand a special venire had been waived. The defense gave every indication that it did not intend to pursue having a special venire until the Friday before this case was set to begin on the following Monday, rendering the request for special venire untimely and waived.

IV. WAS AN ILLEGAL WARRANTLESS ARREST OF MITCHELL MADE BY LAW ENFORCEMENT PERSONNEL? IF SO, DID THE TRIAL COURT ERR IN OVERRULING DEFENDANT'S MOTION TO SUPPRESS?

¶ 38. Mitchell argues that his arrest was without probable cause and that the court erred in denying his motion to suppress statements and derivative evidence obtained from the arrest.

¶ 39. Two pursuits of Mitchell occurred before he was arrested. The first took place on foot as he ran from his residence. The second was a high speed chase as police pursued Mitchell in his car.

¶ 40. The facts known to the police prior to their decision to question Mitchell at his home were as follows: (1) Milliken had worked the 4:00–8:00 p.m. shift at the Majik Mart on November 21, 1995; (2) surveillance video at the store showed Mitchell coming into the store three different times that day talking to Milliken; (3) Milliken's coworker saw Milliken write down Mitchell's telephone number in her address book; (4) Milliken telephoned her son to inform him she would be home in fifteen minutes; (5) Milliken had left her personal belongings inside the store and stated that she was going outside to smoke a cigarette with Mitchell; (6) Milliken walked with Mitchell out of the store; (7) ten minutes later, Milliken's coworker stepped outside to ask her a question and realized that she was gone; (8) Milliken's car was still parked at the store; (9) two hours after Milliken had gone outside with Mitchell, she had still not returned, her personal effects were still at the store, and she had not gone home; (10) Milliken's coworker had called the police concerned about Milliken's whereabouts; (11) Milliken's coworker had told the police about Mitchell's visits, showed them the surveillance video, and Mitchell's telephone number in Milliken's purse; (12) the police had cross-referenced the telephone number, learned of Mitchell's address, and proceeded to 323 Croesus Street to see if Mitchell knew of Milliken's whereabouts.

¶ 41. The test for probable cause in Mississippi is the totality of the circumstances. Haddox v. State, 636 So.2d 1229, 1235 (Miss.1994). This Court has defined probable cause as:

a practical, nontechnical concept, based upon the conventional consideration of every day life on which reasonable prudent men, not legal technicians act. It arises when the facts and circumstances with an officer's knowledge, or of which he has reasonably trustworthy information, are sufficient in themselves to justify a man of average caution in the belief that a crime has been committed and that a particular individual committed it.

Conway v. State, 397 So.2d 1095, 1098 (Miss.1980) (quoting Strode v. State, 231 So.2d 779 (Miss.1970)). An officer's knowledge before the pursuit is determinative of probable cause. Riddles v. State, 471 So.2d 1234, 1236 (Miss.1985).

¶ 42. Considering the facts and circumstances under which Milliken disappeared, it was not unreasonable for the officer to form a belief that a crime against Milliken had occurred. The information that was provided to the police seemed reasonable and trustworthy enough to connect Mitchell to the possible abduction.

¶ 43. There are three valid police tactics to investigate a possible crime as set out by this Court in Nathan v. State, 552 So.2d at 103: (1) Voluntary Conversation: An officer may approach a person for the purpose of engaging in a voluntary conversation no matter what facts are known to the officer since it involves no force and no detention of the person interviewed; (2) Investigative Stop and Temporary Detention: To stop and temporarily detain is not an arrest, and the cases hold that given reasonable circumstances an officer may stop and detain a person to resolve an ambiguous situation without having sufficient knowledge to justify an arrest; (3) Arrest: An arrest may be made when the officer has probable cause. (citing Singletary v. State, 318 So.2d 873, 876 (Miss.1975)).

¶ 44. The officers in the present case chose to approach Mitchell and attempt to engage him in voluntary conversation, although they could have just as legally stopped and detained Mitchell. “Under the Fourth Amendment, police officers with reasonable suspicion that an individual has committed or is about to commit a crime may detain that individual, using some force if necessary, for the purpose of asking investigative questions.” Kolender v. Lawson, 461 U.S. 352, 367, 103 S.Ct. 1855, 75 L.Ed.2d 903 (1983).

¶ 45. Officer McKaig found Mitchell standing in his back yard. McKaig identified himself and explained to Mitchell that he wanted to ask him some questions. Mitchell ran, ignoring McKaig's order to halt. Minutes later, Mitchell also ignored an order to halt when Officer Doucet saw Mitchell on Reynoir Street. Each of these orders to halt were legitimate under the law. Officers are permitted to stop and temporarily detain citizens for questioning when there is suspicion and/or arrest a citizen when probable cause exists. Nathan, 552 So.2d at 103 (citing Singletary, 318 So.2d at 876).

¶ 46. Here, the requisite suspicion existed to allow the officers to stop and detain Mitchell temporarily for questioning. Once he fled the officers and ignored their commands to halt, the officers, already possessing a reasonable suspicion, also obtained probable cause. This is consistent with Sibron v. New York, 392 U.S. 40, 66–67, 88 S.Ct. 1889, 20 L.Ed.2d 917 (1968), which states “deliberately furtive actions and flight at the approach of strangers or law officers are strong indicia of mens rea, and when coupled with specific knowledge on the part of the officer relating the suspect to the evidence of crime, they are proper factors to be considered in the decision to make an arrest.”

¶ 47. Mitchell argues that his arrest began when McKaig spoke to Mitchell in his backyard, in accordance with Pollard v. State, 233 So.2d 792 (Miss.1970); Terry v. State, 252 Miss. 479, 173 So.2d 889 (1965); and Smith v. State, 240 Miss. 738, 128 So.2d 857 (1961). However this pursuit did not result in arrest. Instead it resulted in the police issuing a be-on-the-lookout (“BOLO”) for Mitchell. Mitchell's argument that an arrest resulted from the events in Mitchell's backyard is incorrect.

¶ 48. After the BOLO had been issued on police radio, Officer Dawson, traveling in a marked police car, viewed a man and car fitting the description getting gasoline at a Shell station. As Dawson approached the gas station, Mitchell threw down the gas nozzle and sped away. Dawson stated that he immediately began following Mitchell's vehicle, but did not put on his lights and siren until he observed Mitchell run a red light on another street. Mitchell was eventually arrested for disturbing the peace, reckless driving, and resisting arrest.

¶ 49. This Court held in Ott v. State, 722 So.2d 576, 582 (Miss.1998), that “an officer may make a warrantless arrest based on his own personal observations or based on communications with other officers.” In this case, Officer Dawson relied on the BOLO that had been issued and his observance of Mitchell at the gas station. Dawson stated “(w)hat was going through my mind at that time is I'm looking for this vehicle, the other officers are wanting to talk to this guy, when he sees me he takes off ...”

¶ 50. Probable cause to arrest Mitchell existed when he received the BOLO and subsequently viewed Mitchell's vehicle matching the description. Hamburg v. State, 248 So.2d 430 (Miss.1971). Coupled with Mitchell's reaction by fleeing and stealing gas, Dawson had sufficient probable cause to pursue and arrest Mitchell.

¶ 51. The Biloxi Police Department had probable cause to arrest Mitchell at the outset of both pursuits that occurred. Accordingly, the trial judge did not err in denying the motion to suppress.

V. DID AN ILLEGAL TRESPASS BY LAW ENFORCEMENT PERSONNEL TAKE PLACE PRIOR TO THE ARREST OF THE DEFENDANT? IF SO, DID THE TRIAL COURT ERR IN OVERRULING DEFENDANT'S MOTION TO SUPPRESS?

¶ 52. Mitchell asserts that the police officers made an illegal trespass onto the property where he was staying, and, as a result, evidence taken from his person and his car should have been suppressed by the trial court. Mitchell contends that, but for the illegal trespass he claims occurred, he would not have fled. Mitchell also asserts that evidence retrieved off of Mitchell's person and his car is directly attributable to Officer McKaig's initial trespass.

¶ 53. Once the police realized that Milliken seemed to have disappeared, Patrolmen McKaig, Doucet, and Matory visited Booker Gatlin's home (Mitchell's grandfather), where Mitchell had been residing. Officer Doucet instructed McKaig to go watch the back door, while he and Matory went to the front door. McKaig stated in his testimony that he was not given permission by an owner or occupant to go onto the property. As McKaig walked along the side, around to the rear of the house, he encountered Mitchell. Mitchell noticed him and asked who was there. McKaig responded by stating that it was the police and that he just wanted to talk to him. Mitchell then fled.

¶ 54. Mitchell contends that this constituted an illegal trespass on the part of the police. Mitchell refers to Davidson v. State, 240 So.2d 463 (Miss.1970), where this Court determined that a game warden had committed trespass when he entered upon Davidson's land to inspect a tractor. The warden then turned over information to the sheriff, who obtained a search warrant to go on the land where it was then determined that the tractor was stolen. Id. This Court ruled that the subsequent search by the sheriff was illegal because it was based on information illegally obtained by the warden. Id. at 463–64. The Court stated that “the right to be free from an illegal search and seizure is a right which the courts must vigilantly protect.” “This right to be secure from invasions of privacy by government officials is a basic freedom in our Federal and State constitutional systems.” Id. at 464.

¶ 55. Mitchell's reliance on Davidson is not well-founded. The holding in Davidson is that a search warrant cannot be sworn and executed based upon information that was obtained through an illegal trespass. Id. Davidson and the case at hand are easily differentiated. In Davidson, the warden was not on the land because of a possible theft of a tractor, whereas in the instant case the police were under the belief that Mitchell was the last person who had seen Milliken and were aware that she had disappeared under curious circumstances. Also the police in the present case did not gather evidence from Mitchell's car or clothing while on the premises to ask him questions. Only after other information was amassed through questioning of Mitchell and the discovery of Milliken's body, did the police obtain search warrants for Mitchell's body and vehicle.

¶ 56. This Court, in Waldrop v. State, 544 So.2d 834, 838 (Miss.1989), determined that a claim of police trespass cannot be made regarding areas that are typically used by visitors. This Court stated: It is not objectionable for an officer to come up upon that part of the property which has “been open to the public common use.” The route which any visitor to a residence would use is not private in the Fourth Amendment sense, and thus if police take that route “for the purpose of making a general inquiry” or for some other legitimate reason, they are free “to keep their eyes open ...” (citing 1 W. LaFave, Search and Seizure, § 2.3, at 318 (1978)). This Court continued quoting LaFave by stating: