Executed September 28, 2005 12:27 a.m. by Lethal Injection in Indiana

41st murderer executed in U.S. in 2005

985th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

5th murderer executed in Indiana in 2005

16th murderer executed in Indiana since 1976

|

|

| Since 1976 |

Date of Execution |

State |

Method |

Murderer

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Date of

Birth |

Victim(s)

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Date of

Murder |

Method of

Murder |

Relationship

to Murderer |

Date of

Sentence |

| 985 |

09-28-05 |

IN |

Lethal Injection |

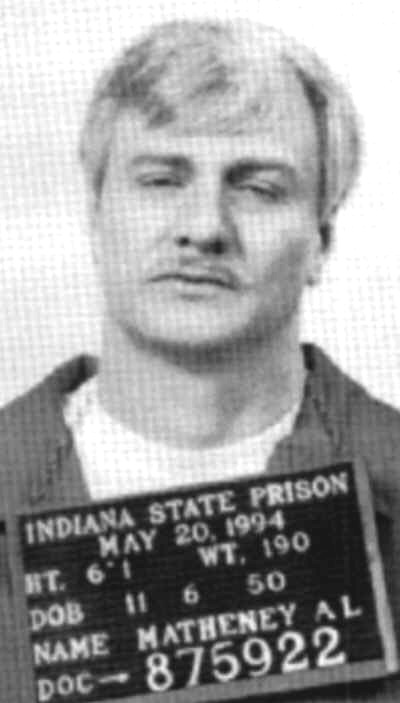

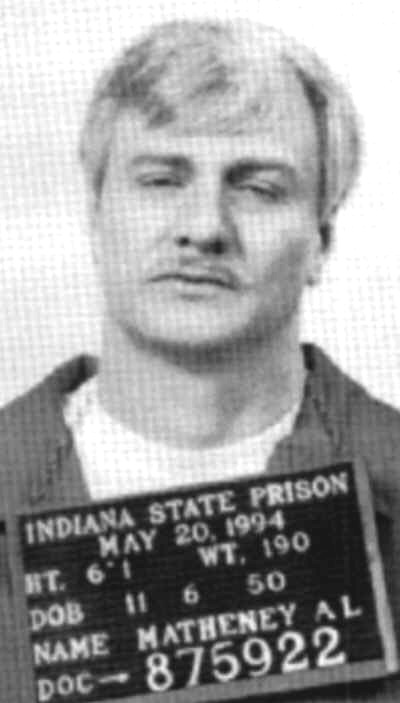

Alan Lehman Matheney W / M / 38 - 54 |

11-06-50 |

Lisa Bianco W / F / 34 |

03-04-89 |

Beating with shotgun |

Ex-Wife |

05-11-90 |

Summary:

Matheny was convicted and sent to prison in 1987 for Battery and Confinement of his ex-wife, Lisa Bianco. While in prison, Matheny had repeatedly expressed a desire to kill Bianco, and attempted to solicit others to do so. After serving almost 2 years, he was given an 8-hour furlogh from Pendleton, where he was an inmate. Although the pass authorized a trip to Indianapolis, Matheny headed straight for St. Joseph County. Once there, he changed clothes and took a shotgun from a friend's house, then drove to Mishawaka. He parked the car in a lot two doors down from his ex-wife's house, then broke in through the back door. Bianco ran from the home, pursued by Matheny through the neighborhood. When he caught her, he beat her with the shotgun that broke into pieces. He then got into his car and drove away. Bianco died as a result of this blunt force trauma. (insanity defense) (This case generated massive amounts of publicity and led to state legislation requiring the Indiana DOC to notify victims of release from prison)

Final Meal:

Chicken wings, a fried chicken dinner, large wedges of potatoes, corn on the cob, biscuits and a chocolate shake.

Final Words:

"I love my family and my children. I'm sorry for the pain I've caused them. I thank my friends who stood by me . . . I'm sure my grandchildren will grow up happy and healthy in the care of their wonderful parents," Matheney said in a final statement read by his lawyer, Steven Schutte.

Citations:

Direct Appeal:

Matheney v. State, 583 N.E.2d 1202 (Ind. January 9, 1992) (45S00-9002-DP-116)

Conviction Affirmed 5-0 DP Affirmed 4-1

Givan Opinion; Shepard, Dickson, Krahulik concur; Debruler dissents.

For Defendant: Scott L. King, Crown Point Public Defender

For State: Arthur Thaddeus Perry, Deputy Attorney General (Pearson)

Matheney v. Indiana, 112 S.Ct. 2320 (1992) (Cert. denied)

PCR:

PCR Petition filed 11-25-92. Amended PCR filed 09-09-94, 10-26-94.

State’s Answer to PCR Petition filed 12-08-92, 10-11-94.

PCR Hearing 10-11-94.

Special Judge Richard J. Conroy

For Defendant: J. Jeffreys Merryman, Jr., Steven H. Schutte, Deputy Public Defenders (Carpenter)

For State: Michael G. Gotsch

04-10-95 PCR Petition denied.

Matheney v. State, 688 N.E.2d 883 (Ind. 1997) (45S00-9207-PD-584)

(Appeal of PCR denial by Special Judge Richard J. Conroy)

Affirmed 5-0; Shepard Opinion; Dickson, Sullivan, Selby, Boehm concur.

For Defendant: J. Jeffreys Merryman, Jr., Steven H. Schutte, Deputy Public Defenders (Carpenter)

For State: Arthur Thaddeus Perry, Deputy Attorney General (Modisett)

Matheny v. Indiana, 119 S.Ct. 1046 (1999) (Cert. denied)

Habeas:

04-14-98 Notice of Intent to File Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus filed.

07-11-98 Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus filed in U.S. District Court, Northern District of Indiana.

08-17-98 Amended Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus filed

Alan L. Matheney v. Ron Anderson, Superintendent (3:98-CV-00183-AS)

Judge Allen Sharp

For Defendant: Marie F. Donnelly, Alan M. Freedman, Chicago, IL

For State: Andrew L. Hedges, Michael A. Hurst, Deputy Attorneys General (Modisett)

03-29-99 Respondent’s Return and Memorandum filed in opposition to Writ of Habeas Corpus.

06-08-99 Petitioner’s Reply and Memorandum filed in support of Writ of Habeas Corpus.

07-30-99 Writ of Habeas Corpus denied.

10-25-99 Certificate of Appealability granted in part.

Matheney v. Anderson, 60 F.Supp.2d 846 (N.D. Ind. July 30, 1999) (3:98-CV-183-AS)

(Petition for Habeas Writ denied by Judge Allen Sharp)

Matheney v. Anderson, 253 F.3d 1025 (7th Cir. June 18, 2001) (99-3657)

(Appeal of habeas denial; Affirmed 2-1, but remanded to U.S. District Court for evidentiary hearing on issue of competency at trial)

Circuit Judge Michael S. Kanne, Judge John L. Coffey; Judge Ilana Diamond Rovner dissents.

For Defendant: Alan M. Freedman, Midwest Center for Justice, Chicago, IL

For State: Michael R. McLaughlin, Deputy Attorney General (Freeman-Wilson)

Anderson v. Matheney, 122 Sct. 1635 (2002) (Cert. denied).

Matheney v. Anderson, 377 F.3d 740 (7th Cir. July 29, 2004) (03-1739).

(After remand to U.S. District Court for evidentiary hearing on issue of competency at trial, and denial of habeas)

Affirmed 3-0; . Michael S. Kanne Opinion; Wiliam J. Bauer, Ilana Diamond Rovner concur.

For Defendant: Alan M. Freedman, Carol R. Heise, Evanston, IL

For State: Thomas D. Perkins, Stephen R. Creason, Deputy Attorney General (Carter)

Matheney v. Davis, ___ S.Ct. ___ (May 16, 2005) (Cert. denied)

Internet Sources:

Clark County Prosecuting Attorney

MATHENEY, ALAN LEHMAN (ON DEATH ROW SINCE 05-11-90)

DOB: 11-06-1950

DOC#: 875922

White Male

Court: Lake County Superior Court Venued from St. Joseph County

Trial Judge: Judge James E. Letsinger

Cause#: 71D05-8903-CF-000181 (St. Joseph) 45G02-9001-CF-00022 (Lake County)

Prosecutor: John D. Krisor

Defense Attorneys: Scott L. King

Date of Murder: March 4, 1989

Victim(s): Lisa Bianco W / F / 34 (Ex-wife of Matheney)

Method of Murder: beating with shotgun

Trial: Information/PC for Murder filed (03-07-89); Amended Information for DP filed (03-20-89); Change of Venue (01-25-90).

Conviction: Murder, Burglary (B Felony)

Sentencing: May 11, 1990 (Death Sentence)

Aggravating Circumstances: b (1) Burglary; b (3) Lying in wait

Mitigating Circumstances: turned himself in; extreme mental and emotional disturbance; helpful, useful, generous and kind; mental disease (schizophreniform disorder).

Indianapolis Star

"Matheney executed for killing ex-wife; Daniels opted against clemency for murderer," by Kevin Corcoran. (September 28, 2005)

MICHIGAN CITY, Ind. -- Alan Matheney, 54, one of the most notorious killers on Indiana's Death Row, was executed by lethal injection early today at the Indiana State Prison in Michigan City.

Gov. Mitch Daniels denied him clemency Tuesday without explanation. He was the fifth inmate to be executed in Indiana this year, the most since the death penalty was reinstituted in 1977.

Late Tuesday night, minutes before the execution took place, seven people stood outside the governor's residence with signs protesting the execution.

"I call it the murder penalty," said Jennifer Cobb, 47. "I believe the state taking a life because that person took a life makes the state a hypocrite."

A Lake County jury, which recommended the death penalty, convicted Matheney of murder for beating his ex-wife, Lisa Marie Bianco, 29, to death in March 1989 with a rifle butt while on an eight-hour furlough from the Correctional Industrial Facility near Pendleton.

Matheney traveled to Mishawaka, burst into Bianco's home, caught her as she tried to run away and struck her in the head with a rifle so hard the weapon broke.

At the time of his crime, Matheney was serving a seven-year sentence for beating Bianco and trying to abduct their two daughters. Mental health experts testified Matheney was delusional, falsely believing Bianco was having an affair with a local prosecutor and the pair were conspiring to keep him in prison for life. At trial, his legal team, including then-public defender Scott King, who's now mayor of Gary, mounted an unsuccessful insanity defense.

Bianco's murder made national headlines and prompted then-Gov. Evan Bayh, who was nearly two months into his first term, to scrap furloughs and deny nearly all requests for clemency during his eight years in office. Since Bayh, two governors, Democrat Joe Kernan and Republican Mitch Daniels, have commuted the death sentences of three inmates.

Last month, Daniels spared the life of Arthur P. Baird II, who was diagnosed as severely mentally ill. Indiana has executed 15 people since the death penalty was reinstated in 1977. Learn more at

Indianapolis Star

"Death Row inmate skips his hearing on clemency," by Richard D. Walton. (September 20, 2005)

A clemency hearing for a Death Row inmate who murdered his ex-wife while on a prison furlough ended abruptly Monday when he refused to testify.

Alan Matheney's refusal keeps the Indiana Parole Board from making a clemency recommendation to Gov. Mitch Daniels, said Board Chairman Raymond Rizzo.

"That's the end of it, there's no (public) hearing next week, there's no nothing," Rizzo had warned Matheney's lawyers. "He takes his chances with whatever happens from there."

Matheney, whose attorneys claim he is mentally ill, is scheduled to die Sept. 28 for bludgeoning 29-year-old Lisa Marie Bianco with the butt of a shotgun in March 1989 outside her Mishawaka home. He was out on an eight-hour pass from prison, where he was serving time for a 1987 assault on Bianco.

The killing spurred public outrage and caused then-Gov. Evan Bayh to suspend the furlough program, later reinstated with restrictions. Reforms included a requirement that domestic abuse victims, upon request, be informed when their abuser is to be freed.

Matheney, 54, was set to testify Monday morning in the Indiana State Prison in Michigan City. When he didn't show, Rizzo issued his warning, and Matheney's attorneys left the room to speak to him privately. About 15 minutes later, they returned to announce he would not appear.

Matheney attorney Carol Heise, saying her client is delusional and psychotic, urged the board still to consider clemency.

"It's a matter of life and death, and you're the chairman of the board," she told Rizzo. "There's a mentally ill prisoner here."

Rizzo replied: "We can't conduct a hearing without that prisoner. That's that."

Bianco's father, Eugene Bianco, attended the hearing. Matheney's refusal to testify was an attempt to manipulate the system, he said.

"He's not mentally ill," said Bianco, a Granger resident who visits his daughter's grave every week. "It's just the way he is."

ProDeathPenalty.Com

On March 4, 1989, Alan Matheney, while on an eight-hour pass from prison, brutally murdered Lisa Bianco (his ex-wife and the mother of his two daughters, Amber and Brooke). On March 4, 1989, Matheney was given an eight-hour pass from the Correctional Industrial Complex in Pendleton, Indiana where he was an inmate. Matheney was serving a sentence for Battery and Confinement in connection with a previous assault on his ex-wife, Lisa Bianco, who was the victim in this case.

The pass authorized a trip to Indianapolis; however, Matheney drove to St. Joseph County. Matheney went to the house of a friend where he changed clothes and removed an unloaded shotgun from the house without the knowledge of those present. Matheney then drove to Mishawaka. He parked his car not far from Lisa Bianco's house and broke in through the back door. Lisa ran from her home, pursued by Matheney. Neighbors witnessed the chase that ensued. When Matheney caught Lisa, he beat her with the shotgun which broke into pieces. One neighbor confronted Matheney and saw him get into a car and drive away. Matheney surrendered to a policeman later that afternoon.

The autopsy showed that Lisa Bianco died as a result of trauma to the head from a blunt instrument. It is worth noting that at trial the prosecution introduced overwhelming evidence of Matheney's murder of Lisa Bianco. Matheney's brother and a friend of Matheney's both testified at trial that Alan Matheney arrived at the friend's home at about 1:00 p.m. on March 4, 1989. The friend further testified that when Matheney left his home approximately one hour later, a gun belonging to his step-son was missing. Matheney's daughter, Brooke, testified that she was at home with her mother in St. Joseph County on the afternoon of the Fourth when she saw her father enter the house and confront her mother. At her mother's request, Brooke ran next door and asked the neighbor to call the police. Several neighbors testified that they watched Matheney violently assault and murder Lisa in the middle of the street by repeatedly striking her with a rifle.

The evidence was so powerful that when defense counsel began his opening statement, he admitted: "On March 4, 1989, in the early afternoon, Alan Matheney beat his ex-wife to death in broad daylight, on a public street corner, in Mishawaka, Indiana." Defense counsel went on to argue that Matheney was insane at the time of the killing, his legal defense, however two separate court-appointed doctors individually reported to the court that Matheney was sane at the time he committed the crimes.

UPDATE: On Monday, August 29, the Indiana Supreme Court set a September 28 execution date for 54-year-old Alan Matheney for the 1989 murder of his ex-wife, Lisa Bianco. In 1989, Matheney was in serving time in prison for an assault on his former wife, Lisa Bianco. He was released on an eight-hour pass, forced his way into Lisa's home in Mishawaka, then killed her by beating her to death with an un-loaded shotgun.

Sixteen years later, Lisa Bianco's mother says it's hard to feel justice has been served. "Justice isn't exactly what you would hope that it would be," says Millie Bianco. "I imagine we are closer. This is more definitive, but I think that the validity of the death penalty sentence was invalidated a long time ago just because it takes you know, so long." The conviction and sentence were upheld but the time it took to get here has worn on the Bianco family. "I don't think that justice is really served, has been served with the death penalty because he's had all these years you know, that Lisa didn't,” says Millie. "It's just not that much of a deterrent because it's not employed on a timely basis. We've been subjected to, you know, all these appeals, having to have Lisa slandered again in court. To me it's just, you know, is a misuse of taxpayers money and the family's emotions."

Matheney could still avoid the death penalty by receiving a stay or seeking clemency from the governor. In 1999, the courts ordered a new evidentiary hearing on Matheney's competency. In February of 2003, a federal judge in South Bend rejected Matheney's appeal that he should have been found mentally incompetent to stand trial, and his attorneys should have sought such a ruling. The federal judge found no evidence Matheney should have been ruled mentally incompetent, and he noted that Matheney's attorneys had pursued an insanity defense. The case returned to the Seventh U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Chicago, which ordered the review. The court ruled in July of 2004 that Matheney was mentally competent to stand trial at the time. The US Supreme Court refused to hear Matheney's appeal in May 2005.

UPDATE: A man who beat his ex-wife to death with an unloaded shotgun during an eight-hour furlough from prison was executed early Wednesday, hours after the governor denied his request for clemency. Alan Matheney, 54, sentenced to death in 1990 for murdering 29-year-old Lisa Bianco, was executed by chemical injection and pronounced dead at 12:27 a.m. EST. "I love my family and my children. I'm sorry for the pain I caused them," Matheney said in his final statement, read by his attorney.

When granted the prison furlough, he had been serving an eight-year sentence for a 1987 assault on Bianco and confining their two children. Prosecutors said he drove to the South Bend suburb of Mishawaka, broke into Bianco's home, chased her outside and beat her to death. The murder came just months after images of Willie Horton, a murderer who committed a rape while on prison furlough in Massachusetts, helped derail Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis' 1988 bid for the White House. In Indiana, then-Gov. Evan Bayh suspended the state's prison furlough program after Bianco's murder. The program has since been reinstated, but with tighter restrictions. The state also agreed to pay $900,000 to Bianco's estate and the couple's children, who were home at the time of the attack.

Bianco had divorced Matheney in 1985. She continued to fear her husband even after his incarceration and had gotten assurances from prison officials that she would be notified if he was ever released. She was not notified of the furlough, however, and Matheney violated the terms of his pass and an earlier court order when he left central Indiana for her home. On Tuesday, Gov. Mitch Daniels denied defense lawyers' request to consider blocking the execution on grounds he was mentally ill. Millie Bianco, the victim's mother, said although she believed Matheney deserved to be executed, she had mixed feelings about Daniels' decision. "This is a man who washed dishes in my kitchen and who could be charming, who loved his dog," she told The Associated Press by telephone from her home in Lake Alfred, Fla. About 20 death penalty opponents marched in front of the prison banging drums Tuesday evening to protest the execution.

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

Alan Lehman Matheney - Indiana - September 28, 2005 12:00 CST

Alan Lehman Matheney, a white man, faces execution on Sept. 28, 2005 for the beating death of his ex-wife, 30-year-old Lisa Bianco, on Mar. 4, 1989. On an eight-hour release from prison Matheney forced entry into Bianco’s home, chased her outside into the street and beat her to death with a .410 gauge shotgun. Matheney has been diagnosed with schizophreniform disorder by mental health professionals. His disorder led him to believe that Lisa Bianco was involved in a conspiracy against him.

Alan Lehman Matheney’s charges are intentional killing while committing a burglary and murder by lying in wait. In a dissenting opinion Indiana Supreme Court Justice DeBruler explains that because in Matheney’s case “the intent of burglary is the intent to kill, the weight of the aggravator is greatly diminished.” He then clarifies that Matheney did not lie in waiting for his victim’s arrival; therefore his second charge has no basis. At the end of his dissenting opinion Justice DeBruler explains that in weighing the one weakened aggravating factor of intentional killing while committing a burglary with the mitigating factor of Matheney’s mental illness he finds that the death penalty is both extreme and inappropriate in this case.

WISH-TV

"Clemency Denied; Execution Set for Matheney." (Sep 27, 2005, 07:11 PM EDT)

The fifth execution of the year is scheduled to take place at the state prison in Michigan City just after midnight. It’s the final episode in a case that changed the criminal justice system in Indiana.

Alan Matheney, 54, will die for the murder of his wife, a crime committed while he was on an eight-hour furlough from prison. The Mishawaka murder of Lisa Bianco in 1989 brought widespread attention to the issue of domestic violence.

Bianco volunteered at a shelter where new residents are still shown videotape of her battered face.

"Lisa is a big part of the Elkhart County women's shelter - her life and unfortunately her death,” said Cyneatha Millsaps, Elkhart County Family Service. “Lisa found support and then we wanna be that support for other women in the process.”

The crime also led to a new law requiring victims to be notified when prisoners are released.

“The system was a complete failure in that regard and that's why Evan Bayh canceled the furlough program on this. Someone who's slipping in a domestic violence situation is at his most dangerous and they don't care about the outcome,” said Ann DeLaney, Julian Center executive director and former Bayh aide.

Alan Matheney also didn't care to attend a clemency hearing. The governor denied a pardon Tuesday in a statement that was just two sentences long.

Lisa Bianco's mother, Millie Bianco, now lives in Florida where she says that her only regret is that it has taken 15 years to carry out the death penalty. She says the execution will be “a piece of cake” compared to her daughter's murder.

IndyChannel.Com

"Man Executed For Slaying Of Ex-Wife." (POSTED: 2:13 am EST September 28, 2005)

MICHIGAN CITY, Ind. -- A man who beat his ex-wife to death with an unloaded shotgun during an eight-hour furlough from prison was executed early Wednesday, hours after the governor denied his request for clemency.

Alan Matheney, 54, sentenced to death in 1990 for murdering 29-year-old Lisa M. Bianco, was executed by chemical injection and pronounced dead at 12:27 a.m.

Matheney's attorney Steve Schutte, one of six people who witnessed the execution, read his client's final statement.

"I love my family and my children. I'm sorry for the pain I caused them," Matheney said in the statement. "I'm sure my grandchildren will grow up healthy and happy in the care of their wonderful parents."

Java Ahmed, an Indiana Department of Correction spokeswoman, said Matheney met his two grandchildren for the first time Tuesday. His 22-year-old daughter brought her 7-month-old daughter and 2-year-old son to visit Matheney, Ahmed said.

Also in his final statement, Matheney thanked four friends for standing by him.

When asked how Matheney was feeling Tuesday as the time of the execution approached, Schutte described him as "severely mentally ill."

"Today he was profoundly mentally ill," Schutte said. "He was confused and disoriented, but he understood what was in store for him tonight."

When granted the furlough from a state prison in Pendleton, Matheney had been serving an eight-year sentence for a 1987 assault on Bianco and confining their two children.

Prosecutors said he drove to the South Bend suburb of Mishawaka, broke into Bianco's home, chased her outside and beat her to death.

The murder came just months after images of furloughed Massachusetts killer Willie Horton helped derail Michael Dukakis' presidential hopes.

Then-Gov. Evan Bayh suspended the state's prison furlough program after Bianco was killed about two months into his first term. It was later reinstated with tightened restrictions that would have prevented Matheney's release.

Lisa Bianco's mother, Millie Bianco, said although she thought Matheney should be put to death, she still had mixed feelings about Gov. Mitch Daniels' decision Tuesday to deny clemency.

"This is a man who washed dishes in my kitchen and who could be charming, who loved his dog," she said by telephone from her home in Lake Alfred, Fla., before Wednesday's execution. "At times your mind skips back to those parts. So it is hard."

But she said even the death penalty was not punishment enough for Matheney.

"If we're talking about true justice, he wouldn't be receiving a nice, quiet injection. Lisa was chased out of her home half naked and bludgeoned to death on the neighbor's doorstep, and that's a horribly indignant murder," she said. "What he is getting is going to be a piece of cake compared to that."

Agencies that work to prevent domestic violence criticized how the state handled releasing Matheney. They said Bianco had done everything abuse victims are urged to do, including filing police reports and testifying against Matheney in court. She was working at a shelter for abused women.

"The legal system was almost to the point of irresponsibility and a total lack of respect for the victim's rights," Millie Bianco said. "She knew once he was out that he would be after her."

The state changed its procedures for notifying crime victims when their attackers are released and agreed to pay $900,000 to Bianco's estate and the couple's children, who were home at the time of the attack.

Matheney lost his last chance to avoid execution on Tuesday when Daniels denied his clemency request without comment. Matheney's attorneys had asked Daniels to consider blocking the execution on grounds he was mentally ill.

The governor's decision came after Matheney refused to attend a state Parole Board hearing last week.

About 20 people marched around in front of the prison banging drums Tuesday evening in protest of the execution. Most of them remained as Matheney was executed.

"I don't believe that vengeance in reaction to violence is a healing for society," said the Rev. Charles Doyle, chairman of the Duneland Coalition Against the Death Penalty. "It puts us all at the same level as the killer."

Matheney was the fifth man executed by the state this year.

Daniels last month blocked the execution of Arthur Baird II, 59, of Darlington, who was convicted of killing his parents and pregnant wife. Baird sought clemency on the grounds he was mentally ill, saying he had no control over his body at the time of the killings. Daniels commuted the death sentence to life without parole.

Matheney's defense attorneys contended during his trial that he was mentally ill, but jurors declined to find him not guilty by reason of insanity or guilty but mentally ill. The jury unanimously recommended the death sentence, and appeals court reviews upheld the verdict.

Gary Post-Tribune

"Killer had dual legacy ," by John Grant Emeigh. (September 28, 2005)

MICHIGAN CITY — His crime was violent and brutal. But his ultimate legacy could save lives.

As Indiana prepared to execute Alan Lehman Matheney early today, the domestic violence reforms born from his crime live on, protecting victims across the state.

Domestic violence experts point to the Matheney case as a pivotal moment in their movement.

Matheney, 54, was set to be executed by lethal injection at Indiana State Prison in Michigan City just after midnight for killing his ex-wife, Lisa Bianco, 16 years ago in Mishawaka.

What made this murder a national story, a TV movie and a battle cry for champions of battered women was that Matheney committed the crime while on an eight-hour furlough from prison.

This case led lawmakers to create new laws requiring victims of domestic violence to be told whenever their attacker was released from jail.

Charlotte Conjelko, a spokeswoman for The Caring Place, a shelter for batter women in Valparaiso, said the legislation was long overdue.

“That’s what it took — Matheney taking her life — before Indiana did something about domestic violence,” Conjelko said.

Mary Beth Schultz, director of the shelter, said Porter County has an effective system in place for notifying domestic violence victims. Whenever someone is arrested on a domestic violence-related crime in Porter County, a judge must approve the release before turning the suspect loose.

Once release is granted, local law enforcement will notify the victim. This system gives the victim plenty of time to make preparations, Schultz said. In 2004, police have called The Caring Place 196 times, alerting women there of an inmate’s release.

Lisa Bianco was never given that chance.

Matheney had just served his second year in prison for beating and confining Bianco in 1987 when he was granted an eight-hour furlough, approved by then-Gov. Evan Bayh. He was authorized to go only to Indianapolis but instead headed straight for St. Joseph County.

Despite making repeated requests to the prison system to be informed about Matheney’s release, Bianco was never notified. He beat her to death with a shotgun he took from a friend’s house.

Domestic violence groups were outraged, and made their anger known to lawmakers.

“It made the police and everyone else more sensitive toward domestic violence issues and that you have to respond and respond quickly,” Schultz said.

Gary Mayor Scott King remembers the Matheney case clearly. He represented Matheney in his murder trial as his court-appointed attorney.

The domestic violence issue put this case in the national spotlight.

“It was the cause celeb at the time,” King said.

There was so much attention paid to the case that it was granted a change of venue. Though tried in South Bend, it was presided over by Lake County Superior Court Judge James Letsinger, and jurors came from Lake County.

“Judge Letsinger worked hard to do his best to level the field in this case and to keep the publicity from prejudicing my client,” King said.

Matheney’s insanity defense didn’t sway the jury from convicting him and, subsequently, opting for the death penalty.

Opponents of the death penalty say the Matheney case is a prime example of why capital punishment should be abolished.

Marti Pizzini of the Duneland Coalition Against the Death Penalty said the state is just as culpable as Matheney in the death of Bianco. Her group held a vigil outside the prison Tuesday.

She said the state should never have granted Matheney that furlough, because, Pizzini said, he was delusional at the time and repeatedly expressed a desire to kill his ex-wife while he was in prison.

“Now, they (the state) are trying to wash the blood of guilt off their hands by executing him,” she said.

Capital punishment will not deter the mentally ill from battering women or murder, Pizzini said.

“They are not going to factor in the threat of execution into their actions,” she said.

Reuters News

"Indiana executes killer who was on prison furlough," by Karen Murphy. (28 Sep 2005 06:20:36 GMT)

MICHIGAN CITY, Ind., Sept 28 (Reuters) - The state of Indiana on Wednesday executed a man who bludgeoned his ex-wife to death while on temporary furlough from prison, where he was serving a sentence for nearly killing her.

Officials at the Indiana State Prison said Alan Matheney, 54, was pronounced dead at 1:27 a.m. EDT (0527 GMT) after an injection of lethal chemicals.

"I love my family and my children. I'm sorry for the pain I've caused them. I thank my friends who stood by me ... I'm sure my grandchildren will grow up happy and healthy in the care of their wonderful parents," Matheney said in a final statement read by his lawyer, Steven Schutte.

For his last meal he had chicken wings, a fried chicken dinner, large wedges of potatoes, corn on the cob, biscuits and a chocolate shake.

Given an eight-hour furlough from an Indianapolis prison in 1989, Matheney drove to the northern Indiana home of his ex-wife, Lisa Bianco, broke in, chased her down in the street and beat her with the butt of a stolen shotgun until the weapon broke into pieces.

Pieces of wood were found embedded in Bianco's skull.

The murder led then-Gov. Evan Bayh to suspend prisoner furloughs and fire two prison employees who neglected to inform Bianco that Matheney was temporarily free. Furloughs were designed to reward good behavior and aid inmates' readjustment to society.

At the time of the murder, Matheney was serving an eight-year sentence for a 1987 assault in which he raped and beat Bianco. A month after the couple's 1985 divorce, he had kidnapped their two daughters.

When he was furloughed, Matheney's mother picked him up for what was supposed to be a day together in Indianapolis, near the prison. But he commandeered the car and stole a friend's unloaded shotgun, searching in vain for ammunition.

Bianco was coming out of the shower when Matheney broke in and she was wearing underwear and a towel when he caught up with her as she reached a neighbor's door. One of their daughters witnessed her mother being beaten to death.

Bianco had been working at a shelter for battered women.

At his murder trial and in subsequent appeals, Matheney's attorneys said he was delusional, thinking Bianco was having an affair with a local prosecutor and that the two were conspiring to keep him in prison. A jury rejected Matheney's insanity defense.

He was the 41st person put to death this year in the United States, and the 985th since capital punishment was restored in 1976. It was Indiana's fifth execution this year, the most since 1938 when the state put eight people to death.

Fort Wayne Journal Gazette

"Matheney execution ‘past time'" by Tom Coyne. (Associated Press Posted on Wed, Sep. 28, 2005)

MICHIGAN CITY – A man whose brutal slaying of his ex-wife spurred sweeping changes in the state’s prison furlough program was executed early this morning.

The killing of Lisa Bianco by Alan Matheney came just months after images of furloughed Massachusetts killer Willie Horton helped derail Michael Dukakis’ presidential hopes. Then-Gov. Evan Bayh suspended Indiana’s prison furlough program after Bianco was killed, about two months into Bayh’s first term.

Millie Bianco says a favorite saying of her former son-in-law was, “What goes around, comes around. I think it’s past time for what goes around to come around,” she said.

Matheney, 54, was convicted of killing Lisa Bianco in 1989 outside her Mishawaka home while he was on a furlough from a state prison near Pendleton, where he was serving an eight-year sentence for beating Bianco and confining their two children.

Domestic violence opponents criticized the handling of the case, saying Bianco had done everything abuse victims are urged to do, including filing police reports and testifying against Matheney in court. She was working at a shelter for abused women at the time of her death.

“The legal system was almost to the point of irresponsibility and a total lack of respect for the victim’s rights,” Millie Bianco said. “She knew once he was out that he would be after her.”

The state changed its procedures for notifying crime victims when their attackers were released and agreed to pay $900,000 to Bianco’s estate and the couple’s children, who were home at the time of the attack.

Matheney lost his last chance of avoiding execution when Gov. Mitch Daniels on Tuesday denied his clemency request. Matheney’s attorneys had asked Daniels to consider blocking the execution on grounds that Matheney was mentally ill.

The governor gave no explanation for his decision, which came after Matheney refused to attend a state Parole Board hearing last week.

Matheney was the fifth man executed by the state this year.

Daniels last month blocked the execution of Arthur Baird II, 59, of Darlington, who was convicted of killing his parents and pregnant wife. Baird sought clemency on grounds he was mentally ill. Daniels commuted the sentence to life without parole.

In his order, Daniels noted Baird’s claim that he was mentally ill but emphasized that life without parole was not an option at the time of Baird’s sentencing and all jurors whose views were known had indicated they would have chosen that alternative if it was available.

Matheney’s defense attorneys contended during his trial that he was mentally ill, but jurors declined to find him not guilty by reason of insanity or guilty but mentally ill. The jury unanimously recommended the death sentence, and appeals court reviews upheld the verdict.

“This is a man who washed dishes in my kitchen and who could be charming, who loved his dog,” Millie Bianco said by telephone from her home in Lake Alfred, Fla. “At times your mind skips back to those parts. So it is hard.”

But she said even the death penalty is not punishment enough for Matheney.

“If we’re talking about true justice, he wouldn’t be receiving a nice, quiet injection. Lisa was chased out of her home half-naked and bludgeoned to death on the neighbor’s doorstep, and that’s a horribly indignant murder,” she said. “What he is getting is going to be a piece of cake compared to that.”

South Bend Tribune

"Matheney execution now only hours away; Inmate has 'special meal' while others wait to see if governor grants reprieve," by By Marti Goodlad Heline. (September 27, 2005)

Today will be Alan Matheney's last full day on earth, barring a last minute decision by Gov. Mitch Daniels to commute his sentence.

Matheney, 54, is scheduled to be executed by lethal injection just after midnight today at the Indiana State Prison in Michigan City for the 1989 murder of his ex-wife, Lisa Bianco.

For her mother, Millie Bianco, it's time Matheney learned, "What goes around comes around," citing one of her former son-in-law's favorite sayings.

"I take no pleasure in anyone's life being ended," Millie Bianco said Monday evening from her home in Haines City, Fla.

But she believes, after 16 years, it's time for the victim's family to see some justice.

As Matheney dined Monday on what prison officials call his "special meal" and continued to have visitors and make phone calls, his lawyers hoped for the best from Daniels' office.

The lawyers say Matheney's mental illness is so severe it is inappropriate to execute him.

Last month, Daniels commuted the death sentence of Arthur Baird II, citing his mental illness.

The governor still had the case under review, was the official word late Monday afternoon from Indianapolis.

Matheney requested a fried chicken dinner complete with potato wedges, corn on the cob, chicken wings and a chocolate milkshake, said Barry Nothstine, prison spokesman.

The special dinner is prepared at a local restaurant.

It is not called the last meal, Nothstine said, since it is served a day or two ahead of time.

That's because prison officials do not want inmates to consume too much the day of the execution, much like a doctor asks patients not to eat before surgery, Nothstine said.

In the final week before execution, prison visitation rules are lifted, and an inmate can have unlimited visits with 10 people.

"Matheney has been having lots of visits of both family and friends," Nothstine said.

Prison officials will not identify those visitors or the witnesses the inmate chooses to watch the execution.

Matheney did not select a spiritual adviser, according to Nothstine.

The former Granger man was free on an eight-hour pass from prison when he used a shotgun to beat Bianco to death outside her Mishawaka home.

Matheney was serving an eight-year sentence for battery on Bianco and taking his two young daughters out of state illegally. He was freed on a brief furlough from the Correctional Industrial Facility near Pendleton.

The killing shook up the state prison system resulting in a suspension of the furlough and work release programs for quite some time.

The incident also served to raise the issue of victims' rights and bring awareness to the obstacles domestic violence victims face. Millie Bianco advocated for legislation to improve the lot of domestic violence victims for a decade after her daughter's death.

Bianco will not be coming to Indiana for the execution but sent the governor her opinion.

If Matheney's clemency hearing had not been canceled, she would have come for that.

She said she told Daniels of Matheney's threats to kill her daughter if she left him, of the failure of the Department of Correction to notify Lisa of Matheney's release.

"I asked, 'At what point does the legal system become irresponsible and total disrespectful of a victim's right?' " Bianco said.

She said she was tired of all the consideration Matheney has received for 16 years.

"We have to have a system where we get some measure of justice," Bianco said for victims. "We also have to have the kind of system that makes a prospective criminal understand what the consequences will be. If we don't have that or don't employ it on a timely basis, it's a futile effort."

Bianco said she has been "on an emotional roller coaster" since the execution date was set four weeks ago.

She wasn't sure what she'd be doing today while waiting to see what happened, probably "business as usual."

"I will have to live with whatever the decision is. It's been that way from the beginning," she said.

Bianco declined to say whether her granddaughters would attend the execution or visit their father. The younger daughter lives locally and the other lives out of state. The local one, Amber, came with her husband to the prison for the clemency hearing her father chose not to attend last week.

On Friday, Matheney's lawyers submitted to the governor additional materials seeking to stop the execution.

Among them were statements from three jurors at the 1990 trial who would have chosen life in prison without parole if it had been an option then, said attorney Carol Heise of the Midwest Center for Justice of Evanston, Ill.

Also submitted was a statement about Matheney's delusional disorder from a psychiatrist who had examined Matheney before trial, a statement from a magistrate who believes execution is not appropriate and statements from international groups seeking a reprieve on the mental illness issue, Heise said.

The Iinternational Justice Project: Mental Illness

Alan L. Matheney - Indiana

Mental Illness; Schizophreniform Disorder and Paranoid Personality Disorder with Psychotic Delusions.

Execution Date: 28 September, 2005.

Alan Matheney is a 54 year old white male currently awaiting execution in Indiana for the 1989 murder of his ex-wife. On 11 April, 1990, a jury found Mr. Matheney guilty of burglary and the murder of his ex-wife, Lisa Bianco. On 20 April, 1990, the same jury recommended a sentence of death and on 11 May, 1990, Judge Letsinger of the Lake County Superior Court followed the jury’s recommendation and entered a written order imposing the death sentence. There is strong evidence to suggest that Mr. Matheney suffers from extreme mental and emotional disturbance and has been diagnosed with schizophreniform disorder and a severe paranoid personality disorder with psychotic delusions.

Facts of the Crime and mental Illness Background

Mr. Alan Matheney was serving a sentence imposed in St. Joseph County on November 23, 1987, for the 1985 unlawful confinement of his children and the 1987 battery of his ex-wife Lisa Bianco. In September 1985, while Matheney was in jail awaiting a plea acceptance, Dr Arens evaluated his mental state. Dr Arens diagnosed Mr. Matheney as suffering from schizopheroform disorder, observing that Matheney was experiencing social withdrawal, cognitive confusion, anxiety and paranoia. It was agreed that the judgment on the confinement would be deferred while Matheney received psychiatric treatment from Dr. Arens. Matheney and Arens met twelve times between 1985 and 1987. In January 1987, Matheney abused his ex-wife Lisa Bianco. Matheney was checked into the psychiatric ward at South Bend Memorial Hospital, Indiana. Shortly afterwards, Matheney was arrested and charged with the battery of his ex-wife. Mr Matheney entered pleas to both the 1985 confinement and the 1987 battery charges. He was convicted and sent to Pendleton Prison where he received no further psychiatric care.

On March 4, 1989, Matheney was issued with an eight hour pass release from the Correctional Industrial Complex at Pendleton, Indiana. During his incarceration for the crime of battery and confinement, Mr. Matheney was suffering under the delusion that his ex-wife and the prosecutor for St. Joseph County, Michael Barnes, were having an affair. He further believed that Barnes and Bianco had colluded to have him jailed indefinitely.

Alan Matheney used the opportunity provided by the eight hour pass to confront his wife about her part in the delusional conspiracy. He stopped at a friend’s house, removed an unloaded shotgun and drove to his ex-wife’s house. When he arrived, she ran from the house; he followed. Upon catching Ms. Bianco, he hit her in the head with the shotgun killing her. He later surrendered himself to the authorities. At the police station, Matheney asserted that he was at the centre of a conspiracy involving the CIA and organized crime. Additional elements of the conspiracy theory included political corruption, Lisa Bianco’s involvement in the drug trade, and that Lisa Bianco was in possession of tapes that would free him from prison and these tapes he had gone to her house to retrieve.

Two public defenders were appointed to the case, neither had any capital trial experience. The attorneys requested a psychiatric competency examination. The judge granted this request and appointed Drs. Myron Berkson and George Batacan to perform the examinations. Unfortunately, on the same day, March 27, 1989, the judge issued an “Order for Examination Concerning Sanity,” this order excluded any reference to the requested competency determination. In the written instructions to the two doctors the judge failed to direct on the issue of competency. Therefore, the issue of competency to stand trial was not addressed at the original trial.

Also at this time, Mr. Matheney claimed that the relationship between his wife and the St. Joseph County Prosecutor prevented him from securing quality counsel, that his family’s phone was tapped, and that the police had broken into his relatives’ homes to steal evidence. The judge granted the motion and the case was moved to Lake County Superior Court on January 25, 1990.

At his capital trial, Dr. Helen Morrison was a witness for the defence. She found Matheney was suffering from a severe paranoid personality disorder with psychotic delusions. Dr. Morrison characterized the disorder as “a fixed…false belief, a belief which defies reality, but one upon which the person bases his behavior, his subsequent actions, and his subsequent involvement”. Dr. Morrison found that Matheney did appreciate the wrongfulness of his actions, but he could not conform his conduct to the requirements of the law, because his actions at the time of the murder were defined by the psychotic delusions he experienced. Dr Morrison further testified that she believed that the 1985 evaluations and diagnosis were the first documented symptoms of Matheney’s delusional disorder.

Dr. Morrison had a number of face-to-face interviews with Matheney and based upon this information, coupled with the reports from previous psychological examinations administered by other doctors, Morrison diagnosed Matheney as suffering from severe paranoid personality disorder with psychotic delusions that impaired his perception of reality completely.

As stated earlier, the issue of competency to stand trial was not addressed at original trial. It was, however, addressed in 1994 by the Indiana trial court in the post-conviction review of Matheney's conviction. A lengthy evidentiary hearing was conducted. At this time Dr. Morrison’s diagnosis of paranoid delusional disorder led her to affirm unequivocally that in her professional opinion, Matheney was incompetent to stand trial in 1990.

[Matheney] was not competent. He was not able to rationally understand what he needed to do in order to provide a defense. He didn’t trust his attorney because he was part of the court system. He also didn’t have a rational understanding of what this was about. To him, this was about the fact that he had been persecuted. . . . The fact that appellant lacked a rational understanding of the proceedings rendered the fact that he was oriented as to time and place, and able to identify actors within the judicial process, essentially meaningless.

Dr. Morrison re-confirmed in a 2002 videotaped deposition that Matheney was not competent to stand trial because he was "not able to rationally understand what he needed to do to provide a defense" and he did not "trust his attorney because [Matheney believed the attorney] was part of the court system" and therefore part of the conspiracy against him.

Present Situation

The psychiatric evidence illustrates Mr. Matheney’s inability to comprehend the reality of his situation and his inability to make rational choices accordingly. The mental illness is treatable, which greatly reduces the risk of future violence. Despite this, all his appeals to date have failed. Mr. Matheney has exhausted all his state and federal appeals. He has an execution date of 28 September, 2005.

WTHR-TV

"Matheney executed." (Associated Press September 28, 2005)

Michigan City, September 28 - (AP) - A man who beat his ex-wife to death with an unloaded shotgun during an eight-hour furlough from prison was executed early Wednesday, hours after the governor denied his request for clemency.

Alan Matheney, 54, sentenced to death in 1990 for murdering 29-year-old Lisa M. Bianco, was executed by chemical injection and pronounced dead at 12:27 a.m. EST.

Matheney's attorney Steve Schutte, one of six people who witnessed the execution, read his client's final statement.

"I love my family and my children. I'm sorry for the pain I caused them," Matheney said in the statement. "I'm sure my grandchildren will grow up healthy and happy in the care of their wonderful parents."

Java Ahmed, an Indiana Department of Correction spokeswoman, said Matheney met his two grandchildren for the first time Tuesday. His 22-year-old daughter brought her seven-month-old daughter and two-year-old son to visit Matheney, Ahmed said.

Also in his final statement, Matheney thanked four friends for standing by him.

When asked how Matheney was feeling Tuesday as the time of the execution approached, Schutte described him as "severely mentally ill."

"Today he was profoundly mentally ill," Schutte said. "He was confused and disoriented, but he understood what was in store for him tonight."

When granted the furlough from a state prison in Pendleton, Matheney had been serving an eight-year sentence for a 1987 assault on Bianco and confining their two children.

Prosecutors said he drove to the South Bend suburb of Mishawaka, broke into Bianco's home, chased her outside and beat her to death.

The murder came just months after images of furloughed Massachusetts killer Willie Horton helped derail Michael Dukakis' presidential hopes.

Then-Gov. Evan Bayh suspended the state's prison furlough program after Bianco was killed about two months into his first term. It was later reinstated with tightened restrictions that would have prevented Matheney's release.

Lisa Bianco's mother, Millie Bianco, said although she thought Matheney should be put to death, she still had mixed feelings about Gov. Mitch Daniels' decision Tuesday to deny clemency.

"This is a man who washed dishes in my kitchen and who could be charming, who loved his dog," she said by telephone from her home in Lake Alfred, Fla., before Wednesday's execution "At times your mind skips back to those parts. So it is hard."

But she said even the death penalty was not punishment enough for Matheney.

"If we're talking about true justice, he wouldn't be receiving a nice, quiet injection. Lisa was chased out of her home half naked and bludgeoned to death on the neighbor's doorstep, and that's a horribly indignant murder," she said. "What he is getting is going to be a piece of cake compared to that."

Agencies that work to prevent domestic violence criticized how the state handled releasing Matheney. They said Bianco had done everything abuse victims are urged to do, including filing police reports and testifying against Matheney in court. She was working at a shelter for abused women.

"The legal system was almost to the point of irresponsibility and a total lack of respect for the victim's rights," Millie Bianco said. "She knew once he was out that he would be after her."

The state changed its procedures for notifying crime victims when their attackers are released and agreed to pay $900,000 to Bianco's estate and the couple's children, who were home at the time of the attack.

Matheney lost his last chance to avoid execution on Tuesday when Daniels denied his clemency request without comment. Matheney's attorneys had asked Daniels to consider blocking the execution on grounds he was mentally ill.

The governor's decision came after Matheney refused to attend a state Parole Board hearing last week.

About 20 people marched around in front of the prison banging drums Tuesday evening in protest of the execution. Most of them remained as Matheney was executed.

"I don't believe that vengeance in reaction to violence is a healing for society," said the Rev. Charles Doyle, chairman of the Duneland Coalition Against the Death Penalty. "It puts us all at the same level as the killer."

Matheney was the fifth man executed by the state this year.

Matheney v. State, 583 N.E.2d 1202 (Ind. January 9, 1992) (Direct Appeal).

Defendant was convicted by jury in the Lake Superior Court, James E. Letsinger, J., of murder and burglary and was sentenced to death. Defendant appealed. The Supreme Court, Givan, J., held that: (1) tendered instruction on voluntary manslaughter was properly refused; (2) no compelling need or extraordinary circumstances required court to compel testimony of prosecuting attorney in support of insanity defense; and (3) evidence supported lying in wait aggravating circumstance, and aggravators and mitigators were fully considered by trial court and jury in reaching death penalty sentence.

Affirmed.

Shepard, C.J., concurred in result.

DeBruler, J., concurred in part and dissented in part and filed opinion.

GIVAN, Justice.

A jury trial resulted in the conviction of appellant of Murder and Burglary. The jury recommended the death penalty. On May 11, 1990, the trial court sentenced appellant to death.

The facts are: On March 4, 1989, appellant was given an eight-hour pass from the Correctional Industrial Complex in Pendleton, Indiana where he was an inmate. Appellant was serving a sentence for Battery and Confinement in connection with a previous assault on his ex-wife, Lisa Bianco, who was the victim in this case. The pass authorized a trip to Indianapolis; however, appellant drove to St. Joseph County. Appellant went to the house of a friend, Rob Snider, where he changed clothes and removed an unloaded shotgun from the house without the knowledge of those present.

Appellant then drove to Mishawaka. He parked his car not far from Bianco's house and broke in through the back door. Bianco ran from her home, pursued by appellant. Neighbors witnessed the chase that ensued.

When appellant caught Bianco, he beat her with the shotgun which broke into pieces. One neighbor confronted appellant and saw him get into a car and drive away. Appellant surrendered to a policeman later that afternoon. The autopsy showed that Bianco died as a result of trauma to the head from a blunt instrument.

* * *

Prior to trial, appellant's counsel discovered a letter dated January 20, 1989, written by Michael Barnes, prosecuting attorney for St. Joseph County, to appellant's family regarding appellant. In the letter, Barnes referred to appellant as a "troubled" and "very sick [original emphasis] man."

Appellant made a pretrial motion to call Barnes as a witness for the defense. The trial court denied this motion at a pretrial hearing. Appellant renewed his motion at trial which, again, was denied. Appellant then moved to admit a portion of the transcript of the pretrial hearing and the letter under the theory that the transcript was prior recorded testimony which authenticated the letter. The trial court denied this motion as well.

* * *

Appellant claims that Barnes' testimony would have helped prove the insanity defense. However, Barnes testified at the pretrial hearing that at the time he wrote the letter, he had not formed an opinion as to appellant's mental condition. If he were compelled to testify regarding his characterization of appellant as being "sick," he would state that appellant was not remorseful or regretful of his actions leading to his arrest for Battery and Confinement. Regarding appellant's mental condition, he would have testified that appellant was sane. Barnes stated that he was "fed up" with appellant's family bringing what he felt were meritless claims concerning items believed to be wrongfully in Bianco's possession prior to the killing, and that this frustration precipitated the writing of the letter.

The trial court did not abuse its discretion by refusing to compel the testimony of the prosecuting attorney where evidence from other sources, such as the defense psychiatrist, was available and utilized by the defense to present the insanity defense. The availability of such evidence indicates that there was neither a compelling need nor extraordinary circumstances for the testimony.

* * *

An examination of the evidence most favorable to the State shows that there was sufficient evidence upon which to find that the lying in wait aggravator was proven. There was testimony which indicated that once appellant arrived in St. Joseph County from Pendleton on the day of the killing, he dropped his mother at her home at about 1:00 p.m. There was further testimony that appellant's brother recalled arriving at Rob Snider's home at about 1:05 p.m., and that appellant left Snider's home at about 1:20 p.m. Snider testified that he recalled that appellant left Snider's house at 2:00 p.m.

There was evidence indicating that the distance from Snider's house to Lisa Bianco's house was 9.7 miles and that the drive to Mishawaka from Snider's house took approximately fifteen to twenty minutes. Police first were dispatched to Bianco's house at 3:09 p.m.

The jury had before it evidence that appellant parked the car he was driving in the parking lot of the credit union next to an alley, two houses away from Bianco's house, despite the fact there were no parked cars in the area of Bianco's residence. Footprints were found going from the credit union to Bianco's back yard. The alley was muddy, and the shoes appellant was wearing at the time of his arrest also were muddy.

Bianco's back yard was isolated and secluded by dense bushes along the perimeter. The yard is obscured by branches, a large wooden gate, and the garage. Bianco's daughter heard glass breaking and then saw appellant holding what she described as a black bar.

It would be reasonable for the trier of fact to conclude that appellant had used a circuitous approach toward Bianco's house in order to conceal himself from her and that testimony regarding the amount of time involved tended to prove that appellant waited and watched until he could take Bianco by surprise. The evidence regarding his use of a deadly weapon was indicative of his intent to kill. The evidence was sufficient to support the finding that this aggravating factor was proven beyond a reasonable doubt.

Appellant argues that the death penalty is inappropriate in this case. In review, we determine whether the death penalty is appropriate to the defendant and the circumstances of his crime. Coleman v. State (1990), Ind., 558 N.E.2d 1059.

Appellant's first contention is that the trial court failed to find the mitigating circumstance that appellant was under the influence of extreme mental and emotional disturbance at the time of the murder; therefore, that factor was not properly weighed.

Appellant further argues that his ability to conform his conduct to the requirements of law was impaired by his mental disease. However, the defense psychiatrist offered a diseased-mind diagnosis which was rejected by the jury. The facts show that appellant is intelligent and manipulative.

The manner in which appellant prepared for killing Bianco, the way in which he approached Bianco's house, and then carried out the plan indicate that he was not extremely mentally and emotionally disturbed at the time of the murder. Further, appellant had expressed repeatedly an intention to kill Bianco and had tried to solicit others to do so. This evidence supports the trial court's finding that this mitigating circumstance was not present.

Appellant's final argument against imposition of the death penalty is that his character and the nature of the offense do not warrant such a sentence. The evidence presented indicates that appellant failed to accept responsibility for his actions and that he attempted to shift responsibility to others. Appellant refuses to accept instruction or correction. The nature of this case involves domestic violence so brutal that to find, as appellant argues now, that but for his relationship with Bianco, he lived a life of normalcy, would denigrate the seriousness of this offense.

While appellant has a right to offer evidence of mitigating circumstances he feels are present, the trial court is under no obligation to find that the mitigators exist. Lowery v. State (1989), Ind., 547 N.E.2d 1046, cert. denied, 498 U.S. 881, 111 S.Ct. 217, 112 L.Ed.2d 176. We will not reverse a death penalty sentence for failure to find a mitigator unless the evidence leads only to a conclusion opposite to the one reached by the trial court. Id. We find that the aggravators and mitigators were fully considered by the trial court and jury in reaching the death penalty sentence.

The trial court is affirmed.

DICKSON and KRAHULIK, JJ., concur.

SHEPARD, C.J., concurs in result.

DeBRULER, J., concurs and dissents with separate opinion.

Matheney v. State, 688 N.E.2d 883 (Ind. 1997) (PCR)

Convictions for murder and burglary, and resulting death sentence, were affirmed on appeal, 583 N.E.2d 1202, and petitioner sought post-conviction relief. The Lake Superior Court, Richard J. Conroy, J., denied petition, and petitioner appealed. The Supreme Court, Shepard, C.J., held that: (1) petitioner's mental state did not make him unable to proceed with post-conviction proceedings; (2) postconviction court did not clearly err in denying petitioner's motion to disclose names of jurors at his original trial; (3) as applied in current proceedings, Lake County Magistrate Act did not encroach on power of judiciary in violation of State Constitution; (4) petitioner failed to show that magistrate was biased or engaged in improper ex parte communications; (5) trial and appellate counsel were not ineffective in strategy as to mental illness claims, in failing to object to various jury instructions, or in failing to challenge death penalty statute on constitutional and other grounds; (6) evidence that sentencing court may have relied on presentence psychological questionnaire, without providing defense counsel a copy of it, warranted Supreme Court's independent review of death sentence; and (7) aggravating circumstances outweighed mitigating circumstances, thus supporting imposition of death penalty.

Affirmed.

Boehm, J., filed concurring opinion.

SHEPARD, Chief Justice.

Alan L. Matheney filed a petition for post-conviction relief challenging his conviction and death sentence for the murder of his former wife. Judge Richard J. Conroy denied Matheney's petition, and Matheney appeals. We affirm.

A jury found that in March 1989 Matheney murdered his ex-wife, Lisa Bianco, while on an eight-hour pass from the Correctional Industrial Complex in Pendleton, Indiana, where he was serving a sentence for battery and confinement in connection with a previous assault on Bianco. Following the jury's recommendation, the court sentenced Matheney to death. This Court affirmed Matheney's conviction and sentence. Matheney v. State, 583 N.E.2d 1202 (Ind.1992). This post-conviction proceeding ensued.

* * *

Matheney claims his trial counsel pursued a defense during the guilt phase unsupported by the Matheney's mental health evidence, and did not adequately argue during the penalty phase the existence of a mitigating circumstance available from Matheney's mental health evidence. Matheney's argument is summarized as follows. Dr. Morrison, a psychologist who had examined Matheney, was called to testify in support of Matheney's insanity defense. She testified that Matheney suffered from a paranoid personality disorder. To prove insanity, a defendant must show, among other things, that he could not appreciate the wrongfulness of his actions when he committed the crime. Ind.Code § 35-41-3-6 (West 1986). Counsel never attempted to prove that Matheney did not appreciate the wrongfulness of his actions. In fact, Dr. Morrison testified as part of Matheney's post-conviction proceeding that she would have opined at trial that Matheney could appreciate the wrongfulness of his actions on the day of the crime. However, she also stated that in her opinion Matheney's illness prevented him from conforming his conduct to the requirements of the law. Such an inability is one of the listed mitigating factors in the death penalty statute. Ind.Code § 35-50-2- 9(c)(6) (West Supp.1996). Therefore, Matheney argues, counsel were ineffective for pursuing a defense at the guilt phase on which they had no hope of success, while failing to adequately present readily available mitigating evidence during the penalty phase.

While present counsel bemoan trial counsels' decision to pursue the insanity defense, they provide no evidence of what alternative strategy trial counsel should have employed in its stead. Indeed, there is much to indicate that employing this defense was the best alternative available. There was no available defense that would have cast doubt on the fact that he intentionally killed Lisa Bianco, and by employing the insanity defense, Matheney's attorneys were able to introduce evidence that they otherwise would not have been able to submit. (See P.C.R. at 1699 (indicating trial counsels' use of insanity defense to get Matheney's side of the story before the jury through the expert called to testify, while keeping Metheney himself off the witness stand)). We conclude counsel did not perform at a level below professional norms.

Matheney's penalty phase claim of ineffective assistance fails on the prejudice prong. In our opinion concerning Matheney's direct appeal, we addressed the "inability to conform" mitigator, noting evidence supporting the trial court's finding that this mitigator did not exist. [FN13] Moreover, while trial counsel did not elicit the statement "Matheney's illness prevented him from conforming his behavior to the requirements of the law" from Dr. Morrison, they did elicit testimony from her at the guilt phase which could support the presence of that mitigator. (See T.R. at 2724-32.) The trial court informed the jury about the "inability to conform" mitigator, and told the jury it could consider evidence from the guilt phase during the penalty phase. Finally, trial counsel argued this mitigator while arguing to the jury, and to the judge, about sentencing. While eliciting Dr. Morrison's explicit opinion as to the presence of this mitigator during the penalty phase may have helped Matheney, given the testimony elicited from Dr. Morrison, trial counsel's closing argument, and the evidence cutting against the presence of that mitigator already mentioned in our previous opinion, we cannot say that the failure to elicit such testimony from Dr. Morrison creates "a reasonable probability that the result of the proceeding would have been different," Cook, 675 N.E.2d at 692.

FN13. We stated:

Appellant ... argues that his ability to conform his conduct to the requirements of the law was impaired by his mental disease. However, the defense psychiatrist offered a diseased-mind diagnosis which was rejected by the jury. The facts show that appellant is intelligent and manipulative.

The manner in which appellant prepared for killing Bianco, the way in which he approached Bianco's house, and then carried out the plan indicate that he was not extremely mentally and emotionally disturbed at the time of the murder. Further, appellant had expressed repeatedly an intention to kill Bianco and had tried to solicit others to do so. This evidence supports the trial court's finding that this mitigating circumstance was not present.

* * *

The charged aggravating circumstances were killing by "lying in wait," and killing while committing or attempting to commit burglary. As fully discussed in our previous opinion, there was abundant evidence proving this aggravator beyond a reasonable doubt. Matheney v. State, 583 N.E.2d 1202, 1208-09 (Ind.1992). There is also ample evidence showing that Matheney broke into Bianco's home with the intent to commit murder therein. The "breaking" aspect is irrefutable: the evidence showed that he broke through the backdoor to gain entry into the house. The evidence indicating that he intended to commit murder after breaking in is also strong: he had repeatedly expressed an intention to kill Bianco and had tried to solicit others to do so; he went straight to Bianco's Mishawaka home, instead of to Indianapolis, on his eight-hour pass from the Pendleton correctional facility, stopping only at his mother's home to drop her off and at Rob Snider's home to change his clothes and get one of Snider's shotguns; and he pursued Bianco with the gun in hand as she ran from her home dressed only in her underpants, striking her repeatedly upon catching her until the gun shattered from the force of the blows. Few things short of fear of imminent death would drive the average female out of her urban home across the street and over to the house of a neighbor in the middle of the day dressed only in her underpants.

The evidence also suggests some arguably mitigating circumstances. First, the defendant was extremely angry with the victim, which could be evidence that he was under the influence of an extreme mental or emotional disturbance when he killed Bianco. Ind.Code Ann. § 35-50-2-9(c)(2) (West Supp.1996). However, as Judge Letsinger noted, there was also evidence tending to show that his anger did not rise to the level that it dominated his actions.

The video tape after his arrest that day shows a calm demeanor with Matheney discussing the case disposition just after the fact. This attitude is entirely consistent with the witness description of his calm demeanor before the fact. He had given no one any indication of emotions out of control. These witnesses had known and observed his behavior from birth.

(Petitioner's Br. at A-1--A-2.) Thus, we can only afford this mitigator slight weight.

Second, while evidence was offered supporting the contention that Matheney suffered from a mental disease which caused him to view life through a distorted and deluded version of reality, (see, e.g., T.R. at 2724-32), there was little evidence tending to show that this alleged mental disease left Matheney literally no other choice but that of killing Lisa Bianco. While it may have caused him to believe that Bianco and others were conspiring to keep him incarcerated and deprive him of his rights, we are still left with the question of why that belief would necessarily drive Matheney to kill Bianco instead of simply sticking to legal, lawful avenues of exposing this perceived unlawful conspiracy. While hate, jealousy and vengeance may be motivations which are undesirable and often lead people to do things they otherwise would not do, we do not consider people who act upon these motivations to be "mentally ill" or unable to "conform their conduct to the requirements of the law," per se. Moreover, other evidence before the trial court supported its finding that this mitigating circumstance was not present. See supra note 13. Thus there is little if any weight for this mitigator available to effect the significant weight of the two proven aggravators.

Finally, we note that the jury fully considered the aggravators and mitigators and recommended the death sentence upon concluding that latter outweighed by the former, Matheney, 583 N.E.2d 1202, 1209 (Ind.1992), and did so without the aid of the psychological questionnaire at issue. Our reweighing of the statutory aggravators and mitigators, also without consideration of the contents of Judge Letsinger's psychological questionnaire, amply demonstrates that the aggravating circumstances outweighed the mitigating circumstances and that death is appropriate for this offense and this offender.

Conclusion -

We affirm the judgment of the post-conviction court.

DICKSON, SULLIVAN and SELBY, JJ., concur.

BOEHM, J., concurs with separate opinion.

Matheney v. Anderson, 253 F.3d 1025 (7th Cir. June 18, 2001) (Habeas)

Defendant, who was convicted of murder and burglary and sentenced to death, appealed from an order of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Indiana, Allen Sharp, J., 60 F.Supp.2d 846, which denied his habeas petition without holding an evidentiary hearing. The Court of Appeals, Coffey, Circuit Judge, held that: (1) evidentiary hearing was required to determine whether defendant received ineffective assistance of counsel because his defense team did not pursue his request for a hearing on his competency to stand trial prior to the commencement of trial, and (2) defendant did not meet his burden of establishing prejudice resulting from counsel's failure to present defense psychiatrist's testimony at penalty phase of capital trial to establish existence of a factor mitigating against imposition of the death penalty.

Affirmed in part; remanded with instructions.

Ilana Diamond Rovner, Circuit Judge, filed opinion concurring in part and dissenting in part.

COFFEY, Circuit Judge.

On March 7, 1989, the State of Indiana charged Alan Matheney in a two-count indictment with murder and burglary. Matheney entered a plea of not guilty as to both counts. In April 1990, an Indiana jury found Matheney guilty on both counts and recommended the death penalty. The trial judge agreed, and on May 11, 1990, Matheney was sentenced to death.

After exhausting his state remedies, Matheney filed a petition on July 10, 1998, in federal court pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2254 for a writ of habeas corpus challenging his convictions and death sentence. On July 30, 1999, the district court, without holding an evidentiary hearing, denied Matheney's habeas petition. See Matheney v. Anderson, 60 F.Supp.2d 846 (N.D.Ind.1999). The court proceeded to grant a certificate of appealability on two issues: (1) whether the state trial court "should have found the petitioner incompetent to stand trial or, in the alternative, should have granted an evidentiary hearing on the petitioner's competency to stand trial"; and (2) "whether the petitioner was denied effective assistance of counsel at the penalty and the sentencing phases of his trial...."

With respect to the second issue, Matheney claims that his trial attorney's performance fell below an objective standard of reasonableness when the attorney did not call the defense psychiatrist, Dr. Helen Morrison, to the stand during the penalty phase of the trial. Dr. Morrison had previously testified during the guilt phase of the trial, in support of Matheney's defense of insanity, that she believed Matheney suffered from a mental disease or defect at the time of the murder. Matheney claims that if Dr. Morrison had been called to the stand during the penalty phase, she could have offered testimony to establish the existence of a factor mitigating against imposition of the death penalty--that a mental disease or defect rendered Matheney incapable of conforming his conduct to the requirements of the law. We reject Matheney's claim because the trial judge, who is the ultimate decision-maker in matters of capital sentencing under Indiana law, stated on the record that he gave no weight to this mitigating factor because, after hearing the testimony during the guilt phase of the trial, he agreed with the two court-appointed psychiatrists that Matheney suffered from no mental disease or defect at the time of the murder. Thus, we are convinced that Matheney has failed to demonstrate a reasonable probability that additional testimony from Dr. Morrison during the sentencing phase of the trial would have resulted in imposition of a sentence other than death.

However, we remand this case for an evidentiary hearing on issues related to Matheney's alleged incompetency to stand trial and his lawyer's performance on issues related thereto. Matheney's trial attorneys filed a petition requesting the trial court to order independent psychiatrists to perform both a competency evaluation and a sanity evaluation. They then failed to follow through with the request for a competency evaluation after the trial court failed to include it in its order for a sanity evaluation. Given that a legitimate question has been raised as to Matheney's competency to stand trial and his lawyer's performance on this issue, we remand the case for an evidentiary hearing.

I. BACKGROUND

On March 4, 1989, the defendant, while on an eight-hour pass from prison, [FN1] brutally murdered Lisa Bianco (his ex-wife and the mother of his two daughters, Amber and Brooke). The core facts of this case were succinctly set forth in the Indiana Supreme Court's opinion denying Matheney's direct appeal of his conviction:

FN1. Matheney and Bianco were divorced on June 19, 1985, and Bianco

was awarded custody of the couple's two daughters. Matheney initially was granted supervised visitation. On the day of his first unsupervised visitation, July 3, 1985, Matheney seized his children and left Indiana for other parts of the United States. He was apprehended on August 23, 1985, in North Carolina and charged with confinement. He was convicted and sentenced on the confinement charge and of a battery charge stemming from an earlier physical attack on his ex-wife.

On March 4, 1989, appellant was given an eight-hour pass from the Correctional Industrial Complex in Pendleton, Indiana where he was an inmate. Appellant was serving a sentence for Battery and Confinement in connection with a previous assault on his ex-wife, Lisa Bianco, who was the victim in this case. The pass authorized a trip to Indianapolis; however, appellant drove to St. Joseph County. Appellant went to the house of a friend, Rob Snider, where he changed clothes and removed an unloaded shotgun from the house without the knowledge of those present.

d the chase that ensued.