Executed April 10, 2013 07:19 p.m. EST by Lethal Injection in Florida

7th murderer executed in U.S. in 2013

1327th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Florida in 2013

75th murderer executed in Florida since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(7) |

|

Larry Eugene Mann W / M / 27 - 59 |

Elisa Nelson W / F / 10 |

01/14/83 03/02/90 |

Citations:

Mann v. State, 420 So.2d 578 (Fla. 1982). (Direct Appeal)

Mann v. State, 453 So.2d 784 (Fla. 1984). (Direct Appeal - After Resentencing)

Mann v. State, 482 So.2d 1360 (Fla. 1986). (PCR)

Mann v. State, 603 So.2d 1141 (Fla. 1992). (Direct Appeal - After Resentencing)

Mann v. Dugger, 844 F.2d 1446 (11th Cir. 1988). (Federal Habeas)

Final / Special Meal:

Fried shrimp, fish and scallops, stuffed crabs, hot butter rolls, cole slaw, pistachio ice cream and a Pepsi.

Final Words:

None.

Internet Sources:

Florida Department of Corrections

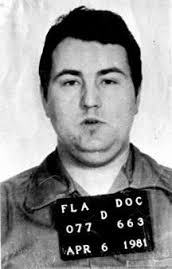

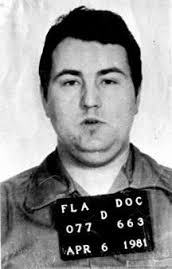

DC Number: 077663Current Prison Sentence History:

Offense Date-Offense-Sentence Date-County-Case No.-Prison Sentence Length

11/04/1980

1ST DG MUR/PREMED. OR ATT.

03/26/1981

PINELLAS

8008741

DEATH SENTENCE

11/04/1980

KIDNAP;COMM.OR FAC.FELONY

03/26/1981

PINELLAS

8008741

99Y 0M 0D

At approximately 10:30 a.m. on 11/04/80, 10-year-old, Elisa Nelson was riding her bike to school. She was late for school because she had a dentist appointment that morning, and her mother had given her a note excusing her absence. Elisa’s bicycle was found later that day in a ditch approximately one mile from Elisa’s school. A search party, which included police officers and community members, was initiated. Elisa’s body was found on 11/05/80.

Elisa died from a skull fracture possibly caused by a single blow to the head. A cement-encased steel pipe was found lying next to the body. There were two lacerations approximately 3.5 and 4.5 inches along the girl’s neck. The medical examiner could not discern if the lacerations were made before or after the child’s death, but they were not the cause of death. There were no signs of molestation on the body.

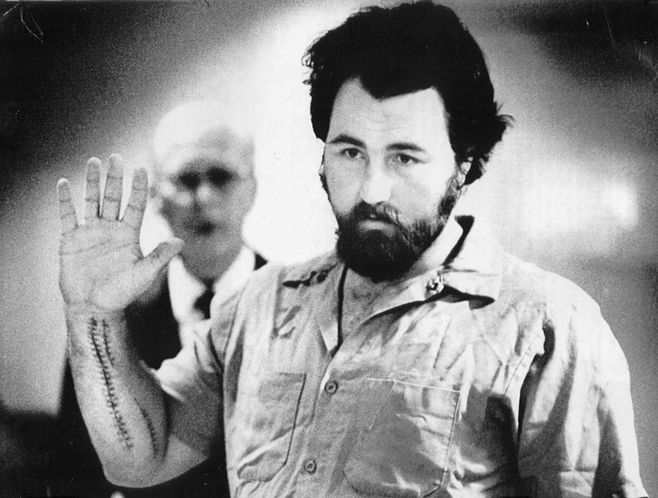

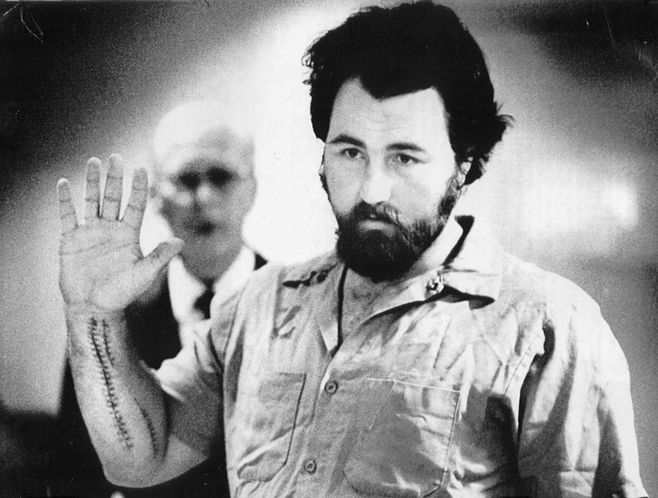

The same day that Elisa disappeared, Larry Eugene Mann attempted to commit suicide by slashing both of his forearms. The police were summoned to help, and Mann stated to them that he had “done something stupid and needed help.” Mann was taken to the hospital were the doctor ruled that Mann had made a serious attempt to end his life. On 11/08/80, Mann asked his wife to retrieve his glasses from his 1957 Chevy pickup truck. Upon doing so, Mrs. Mann found the bloodstained note that Elisa’s mother had written to excuse her from school. A friend of Mrs. Mann’s reported this finding to the police and that resulted in a search warrant of Mann’s truck and house. Inside the truck, a bloodstain was found with the same blood type as both Mann and Elisa. On 11/10/80, Mann was arrested. Prior to the above incident, Mann had previously attempted suicide at least three or four times. Mann also has a history of pedophilia and psychotic depressions.

UPDATE: Larry Mann was executed without a final statement. He responded "Uh, no sir" when asked if he had any final words. Had she lived, Elisa would have been 42 years old by the time Mann was executed.

"Florida executes man for 1980 murder of 10-year-old schoolgirl." (Wed Apr 10, 2013 7:56pm EDT)

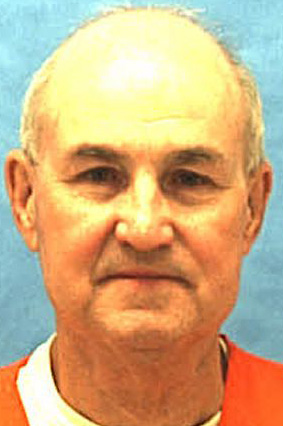

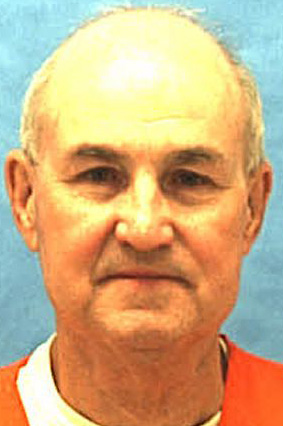

(Reuters) - Florida executed one of its longest-serving death row inmates on Wednesday for kidnapping and killing a 10-year-old girl in 1980. Larry Eugene Mann, 59, was pronounced dead from a lethal injection at 7:19 p.m. EDT (2319 GMT) at the Florida State Prison in Starke, the Florida Department of Corrections said. A last-minute appeal had been denied shortly before the execution.

Mann, a pedophile who had previously served time in prison for sexual battery, snatched Elisa Nelson from her bicycle as she pedaled to school on November 4, 1980, in the Gulf Coast town of Palm Harbor, according to court documents. He threw the bicycle in a ditch and drove the girl to an orange grove, where he beat her, stabbed her and crushed her head with a concrete-encased pole, trial evidence showed. Elisa had carried a note in her pocket explaining that she was late for school because she had a dental appointment. The blood-stained note was found in Mann's truck.

Mann was convicted of murder and sentenced to die in 1981, then received the death penalty again in 1990 after a federal court granted him a re-sentencing.

In an appeal rejected by the U.S. Supreme Court last week, Mann's lawyers argued that Florida's death penalty law failed to meet evolving standards of decency, in part because it allows a jury to recommend death by a simple majority rather than requiring unanimity. They also said Mann had been arbitrarily chosen for execution from among more than 400 Florida Death Row inmates, 94 of whom had exhausted their appeals.

Since his 1990 re-sentencing, Mann's case had been reviewed by dozens of judges and justices, according to Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi.

"Florida man executed in girl's 1980 slaying," by Brendan Farrington. (Associated Press)

STARKE, Fla. -- Florida executed one of the longest-serving inmates on its death row Wednesday evening, 32 years after he kidnapped and murdered a 10-year-old girl who was riding her bike to school after a dentist put on her braces. Larry Eugene Mann was put to death by lethal injection for kidnapping and murdering Elisa Vera Nelson on Nov. 4, 1980. Melissa Sellers, a spokeswoman for Gov. Rick Scott's office, said Mann was pronounced dead at 7:19 p.m. at the Florida State Prison in Starke. He was 59.

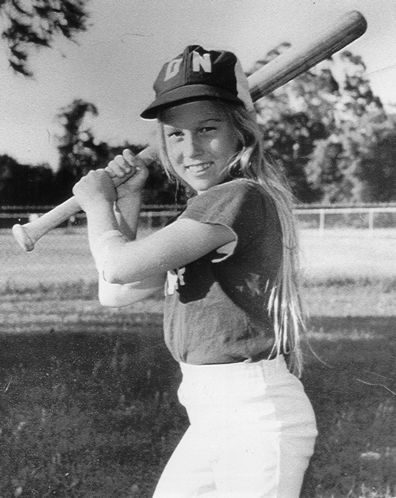

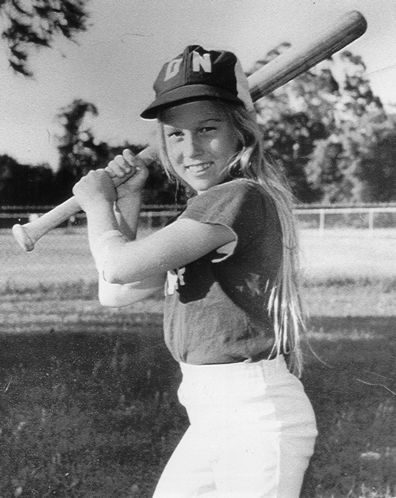

The death sentence was carried out more than an hour after the U.S. Supreme Court denied Mann's latest appeal. The condemned man answered "Uh, no sir," when asked if he had any last words before the procedure began. There were 28 witnesses to the execution, including media and corrections personnel, and a group of Elisa's relatives sat in the front row wearing buttons with her photo on them. Afterward, Elisa's family was joined by a group of friends and family as her brother, Jeff Nelson, read a statement describing his sister as a "bright, funny, caring, beautiful little girl" who loved to play baseball and pretend to be a school teacher. He said she was a Girl Scout who would take in stray pets and donated money she earned to charity. She was a cheerleader who loved to dance and sing.

Then he described in horrifying detail how she died, saying Mann abducted her less than 100 yards from her school in Pinellas County. He said his sister fought hard, and Mann beat her, sending blood and hair throughout his pickup truck, as well as the note his mother wrote excusing Elisa from being late to school. He described how Mann pulled over into an abandoned orange grove, slit her throat twice, and then bludgeoned her head with a pipe with a cement base. He paused from the written statement to add, "We just watched that same man slip into a very peaceful sleep. That's a far cry from how my sister passed." Earlier, Nelson's wife Debbie grasped his arm as Mann's sentence was carried out. Asked by the execution team leader if he had any final words, Mann said, "Uh,no sir." Elisa's parents, David and Wendy Nelson, watched in silence. Her father kept his arms cross as he stared at Mann, who kept his eyes closed except for a brief moment throughout the procedure.

Outside the prison, there were 43 people gathered in favor of the execution and, in a separate area, 38 people were protesting the death penalty.

In 1980, Mann tried killing himself immediately after the girl's slaying, slashing his wrists and telling responding police officers he had "done something stupid." They thought he was talking about the suicide attempt until a couple of days later when Mann's wife found the bloodied note Elisa's mother wrote. While Mann sought to die the day he killed Elisa, his lawyers had succeeded in keeping him alive for decades through scores of appeals. His lawyers didn't contest his guilt during appeals, but rather whether he had been properly sentenced to death. Jeff Nelson criticized the justice system for making his family wait so long. "Elisa was only in our lives for less than 3,800 days and this pedophile and his lawyers have spent nearly 12,000 days - over three times her entire life - making a mockery of our legal system," he said.

Of the 406 inmates on death row in Florida, only 28 had been there longer than Mann.

Mann woke up at 6 a.m. and had his final meal at 10 a.m, including fried shrimp, fish and scallops, stuffed crabs, ice cream and a soda. His only visitors were his two lawyers and a spiritual adviser. His mood was calm and somber in the hours leading up to the execution time, said Department of Corrections spokeswoman Ann Howard. While Mann didn't make a last statement in the death chamber, he did ask that "last words" be handed out after the execution. He chose a Bible verse. "For the wages of sin is death, but the gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord," Mann wrote out by hand.

Elisa's brother said the family has had to hear over the years that Mann would kneel in prayer while in prison and express remorse for his crime. "He just had his chance to say something and he didn't say anything," Nelson said. "We question whether he was really remorseful."

"Larry Mann executed for Palm Harbor girl's 1980 killing," by Dan Sullivan) (Wednesday, April 10, 2013)

STARKE — Larry Eugene Mann, who crushed a little girl's skull 32 years ago, died Wednesday night as chemicals coursed through his veins. Mann was executed by lethal injection at Florida State Prison for the murder of 10-year-old Elisa Vera Nelson, whom he abducted one morning in 1980 as she rode her bicycle to school in Palm Harbor. He was pronounced dead at 7:19 p.m. He was 59.

Afterward, Jeff Nelson, Elisa's brother, stood in the light of a setting sun outside the prison, joining a crowd of about 50 people who turned out to offer support. Nelson, who was 12 when his sister was killed, thanked authorities for the capture and prosecution of Mann. He also thanked Gov. Rick Scott, who signed Mann's death warrant. For three decades, he said, lawyers have talked about how Mann has changed in prison, how he studied the Bible and prayed and expressed remorse. But no one ever talked about Elisa, he said. She had a cheeky grin and bested a little league team full of boys. She was a cheerleader and dancer who loved to play teacher and tutored neighborhood kids. She was a fun-loving fifth-grader with big blue eyes and shades of gold running through long, blond hair. She loved reading and learning and meeting new people. She tumbled through gymnastic lessons. At home, she hung posters of John Travolta on her bedroom wall. She had a cat named Smokey and a dog named Stupid. Her parents, David and Wendy Nelson, moved to Florida from Michigan in the early 1970s and started a successful construction business.

On the morning of Nov. 4, 1980, Wendy Nelson took her daughter to an orthodontist to be fitted with braces. She wrote a note to excuse Elisa's tardiness from class at Palm Harbor Middle School. Just after 10:30 a.m., Elisa pedaled off to school on her blue and silver bike. Elisa's parents reported her missing later that day and Pinellas sheriff's deputies launched a massive search. Nearly half of Palm Harbor turned out to help, one deputy later testified. Before sunset, a sheriff's helicopter spotted Elisa's bike in a drainage ditch north of the school. The next day, two men searching an isolated, weed-choked orange grove west of County Road 39 found her body beneath an avocado tree. Her throat had been cut, an autopsy showed, but she died from a single blow to the head from a concrete block.

The crime began to unravel after someone phoned a TV station and said authorities should look at Mann. Detectives later learned the call came from one of his neighbors, who had seen him washing dirt off the tires on his 1957 Chevrolet pickup shortly after Elisa went missing. It wasn't the first time Mann had been investigated for a violent crime. In 1973, in Mississippi, he forced his way into an apartment where a woman was baby-sitting a 1-year-old boy. He made the woman commit a sex act, threatening to harm the child if she didn't. He was later arrested and served time in prison. Before that, when he was a teen, Mann kidnapped a 7-year-old girl from a church parking lot and molested her. A forensic exam of Elisa's bike turned up a set of fingerprints under the seat and near the front tire. They belonged to Mann.

But the case's biggest break came a few days later when Mann's wife, Donna, went to his truck to retrieve his glasses. On the front seat, she found Wendy Nelson's note excusing Elisa for being late to school. It was stained with blood. She gave the note to detectives. They searched his truck and found blood and hair matching Elisa's inside the cab. A paint scraping from the rear bumper matched paint from Elisa's bike. And pieces of foam rubber from the front seat matched pieces stuck to Elisa's clothing. Prosecutors theorized that Mann abducted Elisa intending to molest her, but did not go through with it. When she tried to escape, he killed her. A jury convicted him of first-degree murder in April 1981 and recommended death by a 7-5 vote.

But legal errors led him to be resentenced twice — in 1983 and 1990. And appeals kept him alive on death row for more than three decades. Few men on death row had been there longer. In that time, lawyers argued, Mann changed. He corresponded with Sister Loretta Pastva, a nun and professor at Notre Dame College in Ohio, writing her more than 400 letters. "He realizes the seriousness of the thing he did," Pastva testified in a 1998 appellate hearing. "He is very sorry about it. He does not expect anything, any special treatment, but he would wish for some mercy."

Such thoughts stoked the ire of Elisa's surviving family. "It is glaringly apparent that there is something fundamentally flawed with a justice system that takes over 32 years to bring to justice a pedophile who confessed to kidnapping and murdering a 10-year-old girl," Jeff Nelson said. "Several juries of Mann's peers decided that his crime was so heinous that he should die for it. For the last 12,000 days, there have been arguments about pieces of paper that have no bearing on the facts of this case. … But there is never any deliberation about what he did to Elisa in that orange grove on that November morning." Earlier in the day, Mann prepared a written statement. It quoted Bible verse, Romans 6:23: "For the wages of sin is death: but the gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord."

Mann had a last meal of fried shrimp, fish and scallops, stuffed crabs, hot butter rolls, cole slaw, pistachio ice cream and Pepsi.

Twenty-one witnesses stared at their reflections in a rectangular window as the execution team prepared behind a brown curtain. At 7:03 p.m., the curtain rose. Mann lay strapped to a gurney. His bald white head peeked out the end of a white sheet that covered his body. An intravenous tube pierced his left arm. He lifted his head and looked through the window. He leaned back and gazed at the ceiling. A prison official asked if he wanted to say anything. "Uh, no, sir.," Mann said. The chemicals began flowing at 7:04. The witnesses watched in silence. Mann closed his eyes. His chest rose and fell. At 7:07, his mouth slipped open. His cheeks turned ashen. At 7:19, a man in a white coat appeared from behind a curtain. He lifted Mann's eyelids and shined a light. He put a stethoscope to his chest.

It was over in 15 minutes. The curtain closed.

"Execution nears for killer of Pinellas girl, possibly linked to more deaths," by Dan Sullivan. (Sunday, April 7, 2013 4:30am)

PALM HARBOR — No one doubts what Larry Eugene Mann did the morning of Nov. 4, 1980. It has been well established, through forensic evidence, witness statements and Mann's own words — that he abducted 10-year-old Elisa Nelson as she rode her bicycle to school that Tuesday morning 32 years ago. Mann has never claimed he didn't snatch the blond-haired fifth-grader off a Palm Harbor street. He has never denied taking her to the orange grove where she was killed.

Still, years of legal wrangling has prolonged the dreadful story of one of the worst crimes in Pinellas County history. This week, the final chapter might finally be written. Barring a successful last-minute appeal, Mann will be strapped to a gurney at 6 p.m. Wednesday inside Florida State Prison and injected with a lethal cocktail of chemicals. It will mean justice for Elisa's family. But when the 59-year-old former well-driller draws his final breath, he may take with him knowledge of other murders that remain unsolved.

Two states and more than 500 miles away from the place where Elisa died, authorities in south Mississippi have scoured old case files in recent years, trying to link Mann to three of the area's cold cases from the 1970s. A Mississippi native, Mann lived in Pascagoula in that decade. Despite remarkable similarities to Elisa's case, authorities have never been able to say for certain that he committed any of the murders. "I just can't fathom that he had never done that before," said Pascagoula police Detective Darren Versiga. "Are there things he got away with? Absolutely."

• • •

On Feb. 1, 1973, Rose Marie Levandoski vanished after she left class to use a restroom at St. Martin Junior High School in southern Mississippi. Three weeks later, authorities found the 13-year-old's nude body floating in a river near Biloxi. She had been stabbed to death. In October of that year, Larry Mann forced his way into an apartment on Lanier Street in Pascagoula, where a woman was babysitting a 1-year-old boy, according to police. He grabbed the woman by the hair and forced her to her knees. If you don't give me what I want, Mann told the woman, I will take it from the baby. He forced her to commit a sex act on him. Police later caught up with Mann. He was convicted of sexual battery and burglary and sentenced to prison.

Two years later, Mann was living in a work-release camp, which allowed him limited access to the outside world while he served his sentence. On Sept. 24, 1975, Janie Sanders disappeared after walking home with classmates along Lanier Street in Pascagoula. A wildlife officer found the 16-year-old's body the same day, dumped in the woods near Grand Bay, Ala. She had been raped and stabbed. Even with numerous leads and a handful of other suspects, the Levandoski and Sanders cases both eventually went cold.

In 2009, Pascagoula police, who investigated the Sanders kidnapping, began to re-examine their unsolved cases. Detective Versiga looked for patterns of predatory behavior. He noted the obvious similarities with the Sanders and Levandoski slayings and the December 1978 murder of 20-year-old Debra Gunter, who was kidnapped from her job as a clerk at a Gautier, Miss., convenience store and found stabbed to death five days later. He learned of Mann and studied the Nelson case. "He is a predator," Versiga said. "Predators don't just wake up during the night and say, 'I think I'm going to go kill somebody today.' "

Mann once lived on Lanier Street in Pascagoula, Versiga said, where Sanders was last seen, and where he attacked the woman in the 1973 rape case. Despite exhaustive efforts, the detective was unable to determine if Mann was indeed involved in the other cases. "I have looked at him and I can't say he didn't do it," Versiga said. "He was in jail in '81 and a lot of things stopped after that."

• • •

In his years on death row, Mann has maintained he is no longer the violent sexual predator he was three decades ago. After Gov. Rick Scott signed his death warrant March 1, Mann's legal team filed a lengthy appeal with the state Supreme Court. In it, the attorneys noted Mann's spotless prison record, his status as a revered figure among prison guards and fellow inmates, and his in-depth studies of the Bible. They noted remorse he has expressed for killing Elisa, an act he once described as "the cross on which I am crucified daily."

That is little consolation for Elisa's family, who have called for the death penalty since the day he was charged with her murder. For 32 years, they have watched and waited and hoped as Mann's first execution date was stayed, as his death sentence was twice vacated and reinstated. In the 1980s and 1990s, Elisa's mother, Wendy Nelson, was involved in victim advocacy issues, forming the League of Victims and Empathizers (LOVE). In 1994, she appeared in a campaign advertisement for Jeb Bush during his first run for governor. In the ad, Nelson accused then-Gov. Lawton Chiles of being soft on crime for not signing Mann's death warrant.

This month, the state Supreme Court denied Mann's last appeal. The Nelson family has declined to speak publicly since the latest death warrant was signed. "What we're pushing for is to have the law enforced," Wendy Nelson told a reporter in 1982. "Maybe there will be a little girl alive 10 years from now because of this."

Florida authorities have a sample of Mann's DNA in a database, making links to other crimes possible. Still, answers in the Mississippi cases may never be known. Hurricane Katrina destroyed much of the records and evidence there in 2005, Versiga said. "It would be nice if he decided to give a confession in the last few days here," he said. "He might want to cleanse his soul."

"Florida executes man for 1980 murder of 10-year-old schoolgirl." (7:57 p.m. EDT, April 10, 2013)

April 10 (Reuters) - Florida executed one of its longest-serving death row inmates on Wednesday for kidnapping and killing a 10-year-old girl in 1980. Larry Eugene Mann, 59, was pronounced dead from a lethal injection at 7:19 p.m. EDT (2319 GMT) at the Florida State Prison in Starke, the Florida Department of Corrections said. A last-minute appeal had been denied shortly before the execution.

Mann, a pedophile who had previously served time in prison for sexual battery, snatched Elisa Nelson from her bicycle as she pedaled to school on Nov. 4, 1980, in the Gulf Coast town of Palm Harbor, according to court documents. He threw the bicycle in a ditch and drove the girl to an orange grove, where he beat her, stabbed her and crushed her head with a concrete-encased pole, trial evidence showed. Elisa had carried a note in her pocket explaining that she was late for school because she had a dental appointment. The blood-stained note was found in Mann's truck.

Mann was convicted of murder and sentenced to die in 1981, then received the death penalty again in 1990 after a federal court granted him a re-sentencing. In an appeal rejected by the U.S. Supreme Court last week, Mann's lawyers argued that Florida's death penalty law failed to meet evolving standards of decency, in part because it allows a jury to recommend death by a simple majority rather than requiring unanimity. They also said Mann had been arbitrarily chosen for execution from among more than 400 Florida Death Row inmates, 94 of whom had exhausted their appeals.

Since his 1990 re-sentencing, Mann's case had been reviewed by dozens of judges and justices, according to Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi.

Following is a list of inmates executed since Florida resumed executions in 1979:

1. John Spenkelink, 30, executed May 25, 1979, for the murder of traveling companion Joe Szymankiewicz in a Tallahassee hotel room.

2. Robert Sullivan, 36, died in the electric chair Nov. 30, 1983, for the April 9, 1973, shotgun slaying of Homestead hotel-restaurant assistant manager Donald Schmidt.

3. Anthony Antone, 66, executed Jan. 26, 1984, for masterminding the Oct. 23, 1975, contract killing of Tampa private detective Richard Cloud.

4. Arthur F. Goode III, 30, executed April 5, 1984, for killing 9-year-old Jason Verdow of Cape Coral March 5, 1976.

5. James Adams, 47, died in the electric chair on May 10, 1984, for beating Fort Pierce millionaire rancher Edgar Brown to death with a fire poker during a 1973 robbery attempt.

6. Carl Shriner, 30, executed June 20, 1984, for killing 32-year-old Gainesville convenience-store clerk Judith Ann Carter, who was shot five times.

7. David L. Washington, 34, executed July 13, 1984, for the murders of three Dade County residents _ Daniel Pridgen, Katrina Birk and University of Miami student Frank Meli _ during a 10-day span in 1976.

8. Ernest John Dobbert Jr., 46, executed Sept. 7, 1984, for the 1971 killing of his 9-year-old daughter Kelly Ann in Jacksonville..

9. James Dupree Henry, 34, executed Sept. 20, 1984, for the March 23, 1974, murder of 81-year-old Orlando civil rights leader Zellie L. Riley.

10. Timothy Palmes, 37, executed in November 1984 for the Oct. 19, 1976, stabbing death of Jacksonville furniture store owner James N. Stone. He was a co-defendant with Ronald John Michael Straight, executed May 20, 1986.

11. James David Raulerson, 33, executed Jan. 30, 1985, for gunning down Jacksonville police Officer Michael Stewart on April 27, 1975.

12. Johnny Paul Witt, 42, executed March 6, 1985, for killing, sexually abusing and mutilating Jonathan Mark Kushner, the 11-year-old son of a University of South Florida professor, Oct. 28, 1973.

13. Marvin Francois, 39, executed May 29, 1985, for shooting six people July 27, 1977, in the robbery of a ``drug house'' in the Miami suburb of Carol City. He was a co-defendant with Beauford White, executed Aug. 28, 1987.

14. Daniel Morris Thomas, 37, executed April 15, 1986, for shooting University of Florida associate professor Charles Anderson, raping the man's wife as he lay dying, then shooting the family dog on New Year's Day 1976.

15. David Livingston Funchess, 39, executed April 22, 1986, for the Dec. 16, 1974, stabbing deaths of 53-year-old Anna Waldrop and 56-year-old Clayton Ragan during a holdup in a Jacksonville lounge.

16. Ronald John Michael Straight, 42, executed May 20, 1986, for the Oct. 4, 1976, murder of Jacksonville businessman James N. Stone. He was a co-defendant with Timothy Palmes, executed Jan. 30, 1985.

17. Beauford White, 41, executed Aug. 28, 1987, for his role in the July 27, 1977, shooting of eight people, six fatally, during the robbery of a small-time drug dealer's home in Carol City, a Miami suburb. He was a co-defendant with Marvin Francois, executed May 29, 1985.

18. Willie Jasper Darden, 54, executed March 15, 1988, for the September 1973 shooting of James C. Turman in Lakeland.

19. Jeffrey Joseph Daugherty, 33, executed March 15, 1988, for the March 1976 murder of hitchhiker Lavonne Patricia Sailer in Brevard County.

20. Theodore Robert Bundy, 42, executed Jan. 24, 1989, for the rape and murder of 12-year-old Kimberly Leach of Lake City at the end of a cross-country killing spree. Leach was kidnapped Feb. 9, 1978, and her body was found three months later some 32 miles west of Lake City.

21. Aubry Dennis Adams Jr., 31, executed May 4, 1989, for strangling 8-year-old Trisa Gail Thornley on Jan. 23, 1978, in Ocala.

22. Jessie Joseph Tafero, 43, executed May 4, 1990, for the February 1976 shooting deaths of Florida Highway Patrolman Phillip Black and his friend Donald Irwin, a Canadian constable from Kitchener, Ontario. Flames shot from Tafero's head during the execution.

23. Anthony Bertolotti, 38, executed July 27, 1990, for the Sept. 27, 1983, stabbing death and rape of Carol Ward in Orange County.

24. James William Hamblen, 61, executed Sept. 21, 1990, for the April 24, 1984, shooting death of Laureen Jean Edwards during a robbery at the victim's Jacksonville lingerie shop.

25. Raymond Robert Clark, 49, executed Nov. 19, 1990, for the April 27, 1977, shooting murder of scrap metal dealer David Drake in Pinellas County.

26. Roy Allen Harich, 32, executed April 24, 1991, for the June 27, 1981, sexual assault, shooting and slashing death of Carlene Kelly near Daytona Beach.

27. Bobby Marion Francis, 46, executed June 25, 1991, for the June 17, 1975, murder of drug informant Titus R. Walters in Key West.

28. Nollie Lee Martin, 43, executed May 12, 1992, for the 1977 murder of a 19-year-old George Washington University student, who was working at a Delray Beach convenience store.

29. Edward Dean Kennedy, 47, executed July 21, 1992, for the April 11, 1981, slayings of Florida Highway Patrol Trooper Howard McDermon and Floyd Cone after escaping from Union Correctional Institution.

30. Robert Dale Henderson, 48, executed April 21, 1993, for the 1982 shootings of three hitchhikers in Hernando County. He confessed to 12 murders in five states.

31. Larry Joe Johnson, 49, executed May 8, 1993, for the 1979 slaying of James Hadden, a service station attendant in small north Florida town of Lee in Madison County. Veterans groups claimed Johnson suffered from post-traumatic stress syndrome.

32. Michael Alan Durocher, 33, executed Aug. 25, 1993, for the 1983 murders of his girlfriend, Grace Reed, her daughter, Candice, and his 6-month-old son Joshua in Clay County. Durocher also convicted in two other killings.

33. Roy Allen Stewart, 38, executed April 22, 1994, for beating, raping and strangling of 77-year-old Margaret Haizlip of Perrine in Dade County on Feb. 22, 1978.

34. Bernard Bolander, 42, executed July 18, 1995, for the Dade County murders of four men, whose bodies were set afire in car trunk on Jan. 8, 1980.

35. Jerry White, 47, executed Dec. 4, 1995, for the slaying of a customer in an Orange County grocery store robbery in 1981.

36. Phillip A. Atkins, 40, executed Dec. 5, 1995, for the molestation and rape of a 6-year-old Lakeland boy in 1981.

37. John Earl Bush, 38, executed Oct. 21, 1996, for the 1982 slaying of Francis Slater, an heir to the Envinrude outboard motor fortune. Slater was working in a Stuart convenience store when she was kidnapped and murdered.

38. John Mills Jr., 41, executed Dec. 6, 1996, for the fatal shooting of Les Lawhon in Wakulla and burglarizing Lawhon's home.

39. Pedro Medina, 39, executed March 25, 1997, for the 1982 slaying of his neighbor Dorothy James, 52, in Orlando. Medina was the first Cuban who came to Florida in the Mariel boat lift to be executed in Florida. During his execution, flames burst from behind the mask over his face, delaying Florida executions for almost a year.

40. Gerald Eugene Stano, 46, executed March 23, 1998, for the slaying of Cathy Scharf, 17, of Port Orange, who disappeared Nov. 14, 1973. Stano confessed to killing 41 women.

41. Leo Alexander Jones, 47, executed March 24, 1998, for the May 23, 1981, slaying of Jacksonville police Officer Thomas Szafranski.

42. Judy Buenoano, 54, executed March 30, 1998, for the poisoning death of her husband, Air Force Sgt. James Goodyear, Sept. 16, 1971.

43. Daniel Remeta, 40, executed March 31, 1998, for the murder of Ocala convenience store clerk Mehrle Reeder in February 1985, the first of five killings in three states laid to Remeta.

44. Allen Lee ``Tiny'' Davis, 54, executed in a new electric chair on July 8, 1999, for the May 11, 1982, slayings of Jacksonville resident Nancy Weiler and her daughters, Kristina and Katherine. Bleeding from Davis' nose prompted continued examination of effectiveness of electrocution and the switch to lethal injection.

45. Terry M. Sims, 58, became the first Florida inmate to be executed by injection on Feb. 23, 2000. Sims died for the 1977 slaying of a volunteer deputy sheriff in a central Florida robbery.

46. Anthony Bryan, 40, died from lethal injection Feb. 24, 2000, for the 1983 slaying of George Wilson, 60, a night watchman abducted from his job at a seafood wholesaler in Pascagoula, Miss., and killed in Florida.

47. Bennie Demps, 49, died from lethal injection June 7, 2000, for the 1976 murder of another prison inmate, Alfred Sturgis. Demps spent 29 years on death row before he was executed.

48. Thomas Provenzano, 51, died from lethal injection on June 21, 2000, for a 1984 shooting at the Orange County courthouse in Orlando. Provenzano was sentenced to death for the murder of William ``Arnie'' Wilkerson, 60.

49. Dan Patrick Hauser, 30, died from lethal injection on Aug. 25, 2000, for the 1995 murder of Melanie Rodrigues, a waitress and dancer in Destin. Hauser dropped all his legal appeals.

50. Edward Castro, died from lethal injection on Dec. 7, 2000, for the 1987 choking and stabbing death of 56-year-old Austin Carter Scott, who was lured to Castro's efficiency apartment in Ocala by the promise of Old Milwaukee beer. Castro dropped all his appeals.

51. Robert Glock, 39 died from lethal injection on Jan. 11, 2001, for the kidnapping murder of a Sharilyn Ritchie, a teacher in Manatee County. She was kidnapped outside a Bradenton shopping mall and taken to an orange grove in Pasco County, where she was robbed and killed. Glock's co-defendant Robert Puiatti remains on death row.

52. Rigoberto Sanchez-Velasco, 43, died of lethal injection on Oct. 2, 2002, after dropping appeals from his conviction in the December 1986 rape-slaying of 11-year-old Katixa ``Kathy'' Ecenarro in Hialeah. Sanchez-Velasco also killed two fellow inmates while on death row.

53. Aileen Wuornos, 46, died from lethal injection on Oct. 9, 2002, after dropping appeals for deaths of six men along central Florida highways.

54. Linroy Bottoson, 63, died of lethal injection on Dec. 9, 2002, for the 1979 murder of Catherine Alexander, who was robbed, held captive for 83 hours, stabbed 16 times and then fatally crushed by a car.

55. Amos King, 48, executed by lethal inection for the March 18, 1977 slaying of 68-year-old Natalie Brady in her Tarpon Spring home. King was a work-release inmate in a nearby prison.

56. Newton Slawson, 48, executed by lethal injection for the April 11, 1989 slaying of four members of a Tampa family. Slawson was convicted in the shooting deaths of Gerald and Peggy Wood, who was 8 1/2 months pregnant, and their two young children, Glendon, 3, and Jennifer, 4. Slawson sliced Peggy Wood's body with a knife and pulled out her fetus, which had two gunshot wounds and multiple cuts.

57. Paul Hill, 49, executed for the July 29, 1994, shooting deaths of Dr. John Bayard Britton and his bodyguard, retired Air Force Lt. Col. James Herman Barrett, and the wounding of Barrett's wife outside the Ladies Center in Pensacola.

58. Johnny Robinson, died by lethal injection on Feb. 4, 2004, for the Aug. 12, 1985 slaying of Beverly St. George was traveling from Plant City to Virginia in August 1985 when her car broke down on Interstate 95, south of St. Augustine. He abducted her at gunpoint, took her to a cemetery, raped her and killed her.

59. John Blackwelder, 49, was executed by injection on May 26, 2004, for the calculated slaying in May 2000 of Raymond Wigley, who was serving a life term for murder. Blackwelder, who was serving a life sentence for a series of sex convictions, pleaded guilty to the slaying so he would receive the death penalty.

60. Glen Ocha, 47, was executed by injection April 5, 2005, for the October, 1999, strangulation of 28-year-old convenience store employee Carol Skjerva, who had driven him to his Osceola County home and had sex with him. He had dropped all appeals.

61. Clarence Hill 20 September 2006 lethal injection Stephen Taylor Jeb Bush

62. Arthur Dennis Rutherford 19 October 2006 lethal injection Stella Salamon Jeb Bush

63. Danny Rolling 25 October 2006 lethal injection Sonja Larson, Christina Powell, Christa Hoyt, Manuel R. Taboada, and Tracy Inez Paules

64. Ángel Nieves Díaz 13 December 2006 lethal injection Joseph Nagy

65. Mark Dean Schwab 1 July 2008 lethal injection Junny Rios-Martinez, Jr.

66. Richard Henyard 23 September 2008 lethal injection Jamilya and Jasmine Lewis

67. Wayne Tompkins 11 February 2009 lethal injection Lisa DeCarr

68. John Richard Marek 19 August 2009 lethal injection Adela Marie Simmons

69. Martin Grossman 16 February 2010 lethal injection Margaret Peggy Park

70. Manuel Valle 28 September 2011 lethal injection Louis Pena

71. Oba Chandler 15 November 2011 lethal injection Joan Rogers, Michelle Rogers and Christe Rogers

72. Robert Waterhouse 15 February 2012 lethal injection Deborah Kammerer

73. David Alan Gore 12 April 2012 lethal injection Lynn Elliott

74. Manuel Pardo 11 December 2012 lethal injection Mario Amador, Roberto Alfonso, Luis Robledo, Ulpiano Ledo, Michael Millot, Fara Quintero, Fara Musa, Ramon Alvero, Daisy Ricard.

75. Larry Eugene Mann 10 April 2013 lethal injection Elisa Nelson

Florida Commission on Capital Cases

Inmate: Mann, Larry

DC#: 077663

Last Action

08/09/02 USDC 02-1439 Habeas Corpus

08/16/02 USDC 02-1439 Case administratively closed

11/18/04 USDC 02-1439 Case reopened

01/18/05 USDC 02-1439 Amended

10/19/06 USDC 02-1439 Response

11/10/10 USDC-M 02-1439 Petition denied

12/09/10 USDC-M 02-1439 Motion to alter judgment filed

12/17/10 USDC-M 02-1439 Response filed

01/21/11 USDC-M 02-1439 Motion denied

02/22/11 USDC-M 02-1439 Application for Certificate of Appealability was filed

01/11/08 FSC 08-62 3.851 Appeal filed

05/27/08 FSC 08-62 Initial brief filed

06/30/08 FSC 08-62 Answer brief filed

02/06/09 FSC 08-62 Disposition affirmed

02/22/11 USCA 11-10855 Habeas Appeal filed

04/16/07 CC 8008741 (RS) 3.851 Motion filed

09/21/07 CC 8008741 (RS) Amended

11/21/07 CC 8008741 (RS) 3.851 denied

11/26/07 CC 8008741 (RS) SC

Last Updated: 2011-06-28 12:28:07.0

Case Summary

MANN, Larry Eugene (W/M)

DC# 077663

DOB: 06/09/53

Sixth Judicial Circuit, Pinellas County, Case# 80-8741

Sentencing Judge: The Honorable Philip A. Federico

Attorneys, Trial: Susan F. Schaeffer & Patrick D. Doherty – Private

Attorney, Direct Appeal: David A. Davis – Assistant Public Defender

Attorney, Collateral Appeals: Marie-Louise Parmer & Leslie Scalley – CCRC-M

Date of Offense: 11/04/80

Date of Sentence: 03/26/81

Date of Resentence (I): 01/14/83

Date of Resentence (II): 03/02/90

Circumstances of the Offense:

At approximately 10:30 a.m. on 11/04/80, 10-year-old, Elisa Nelson was riding her bike to school. She was late for school because she had a dentist appointment that morning, and her mother had given her a note excusing her absence. Elisa’s bicycle was found later that day in a ditch approximately one mile from Elisa’s school. A search party, which included police officers and community members, was initiated. Elisa’s body was found on 11/05/80. Elisa died from a skull fracture possibly caused by a single blow to the head. A cement-encased steel pipe was found lying next to the body. There were two lacerations approximately 3.5 and 4.5 inches along the girl’s neck. The medical examiner could not discern if the lacerations were made before or after the child’s death, but they were not the cause of death. There were no signs of molestation on the body.

The same day that Elisa disappeared, Larry Mann attempted to commit suicide by slashing both of his forearms. The police were summoned to help, and Mann stated to them that he had “done something stupid and needed help.” Mann was taken to the hospital were the doctor ruled that Mann had made a serious attempt to end his life. On 11/08/80, Mann asked his wife to retrieve his glasses from his 1957 Chevy pickup truck. Upon doing so, Mrs. Mann found the bloodstained note that Elisa’s mother had written to excuse her from school. A friend of Mrs. Mann’s reported this finding to the police and that resulted in a search warrant of Mann’s truck and house. Inside the truck, a bloodstain was found with the same blood type as both Mann and Elisa. On 11/10/80, Mann was arrested. Prior to the above incident, Mann had previously attempted suicide at least three or four times. Mann also has a history of pedophilia and psychotic depressions.

Trial Summary:

11/18/80 Defendant indicted on the following charges: Count I: First-Degree Murder, Count II: Kidnapping

11/20/80 Defendant entered a written plea of not guilty

03/19/81 Defendant found guilty on both counts

03/20/81 A majority of the jury recommended the death penalty.

03/26/81 The defendant was sentenced as follows: Count I: First-Degree Murder – Death, Count II: Kidnapping – 99 years to run consecutive to Count I.

09/02/82 Trial remanded to Circuit Court for resentencing by FSC

01/14/83 Order denying advisory jury panel

01/14/83 Defendant resentenced as follows:

Count I: First-Degree Murder – Death

Count II: Kidnapping – 99 years to run consecutive to Count I

04/02/88 Trial remanded to Circuit Court for resentencing by the USCA 11th Circuit

02/06/90 Upon advisory sentencing, the jury, by a 9-3 majority, voted for the death penalty.

03/02/90 Defendant was resentenced to death on Count I, First-Degree Murder.

Appeal Summary:

Florida Supreme Court – Direct Appeal

FSC# 60,569

420 So. 2d 578

05/04/81 Appeal filed

09/02/82 FSC affirmed the conviction but vacated death sentence

11/03/82 Rehearing denied

12/07/82 Mandate issued

Florida Supreme Court – Direct Appeal (RS 1)

FSC# 63,438

453 So. 2d 784

03/25/83 Appeal filed

05/24/84 FSC affirmed the conviction and sentence

08/30/84 Rehearing denied

10/12/84 Mandate issued

United States Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Certiorari

USSC# 84-5632

469 U.S. 1181

10/22/84 Petition filed

01/14/85 Petition denied

State Circuit Court – 3.850 Motion

CC# 80-8741

01/30/86 Motion filed

01/31/86 Motion denied

Florida Supreme Court – 3.850 Appeal

FSC# 68,261

482 So. 2d 1360

02/01/86 Appeal filed

02/01/86 FSC affirmed trial court denial of the postconviction relief. The rehearing was denied.

02/10/86 Mandate issued

Florida Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

FSC# 68,262

482 So. 2d 1360

02/01/86 Petition filed

02/01/86 Petition and rehearing denied

02/10/86 Mandate issued

United States District Court, Middle District – Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

USDC# 86-135

02/03/86 Petition filed

02/19/86 Petition denied

United States Court of Appeals, 11th Circuit – Petition for Habeas Corpus

USCA# 86-3182

817 F.2d 1471

03/19/86 Appeal filed

05/14/87 USCA denied relief for the conviction but reversed the sentence and

remanded the case for resentencing

09/10/87 Vacated previous opinion and petition for rehearing in banc granted

12/14/87 Case reheard

04/21/88 USDA denied relief for the conviction but reversed the sentence and

remanded the case for resentencing

United States Supreme Court – Petition for Certiorari filed by the State

USSC# 87-2073

489 U.S. 1071

06/19/88 Petition filed

03/06/89 Petition denied

Florida State Supreme Court – Direct Appeal (RS II)

FSC# 75,952

603 So. 2d 1141

05/04/90 Appeal filed

04/02/92 FSC affirmed the conviction and sentence

08/27/92 Revised opinion and rehearing denied

09/28/92 Mandate issued

United States Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Certiorari

USSC# 92-6757

506 U.S. 1085

11/25/92 Petition filed

01/19/93 Petition denied

State Circuit Court – 3.850 Motion

CC# 80-8471

04/28/94 Motion filed

04/22/96 Motion denied in part and evidentiary hearing granted

03/27/97 Motion denied

Florida Supreme Court – 3.850 Appeal

FSC# 90,452

697 So. 2d 511

04/30/97 Appeal filed

06/25/97 Appeal dismissed

State Circuit Court – 3.850 Motion

CC# 80-8741

07/07/97 Motion filed

07/29/98 Motion denied on most issues but an evidentiary hearing was ordered

12/01/98 Evidentiary hearing held

01/13/99 Motion denied

Florida Supreme Court – 3.850 Appeal

FSC# 94,885

770 So. 2d 1158

02/15/99 Appeal filed

09/28/00 FSC affirmed the trial court’s denial of the 3.850 Motion

10/31/00 Rehearing denied

11/27/00 Mandate issued

Florida Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

FSC# 00-2602

794 So. 2d 595

12/20/00 Petition filed

07/12/01 Petition denied

09/05/01 Rehearing denied

United States Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Certiorari

USSC# 01-7092

536 U.S. 962; 122 S. Ct. 2669; 153 L. Ed. 2d 843

11/28/01 Petition filed

06/28/02 Petition denied

State Circuit Court – 3.850 Motion

CC# 80-8471

08/06/02 Motion filed

10/22/02 Motion denied

United States District Court, Middle District – Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

USDC# 02-1439

08/09/02 Petition filed

08/16/02 Administratively closed

11/18/04 Case reopened

01/18/05 Petition amended

11/10/10 Petition denied

12/09/10 Motion to Alter Judgment filed

01/21/11 Motion denied

02/22/11 Certificate of Appealability filed

Florida Supreme Court – 3.850 Appeal

FSC# 03-394

868 So.2d 524

03/17/03 Appeal filed

02/02/04 FSC affirmed the trial court’s denial of the 3.850 Motion

04/26/04 Rehearing denied

State Circuit Court – 3.851 Motion

CC# 80-8741

04/16/07 Motion filed

09/21/07 Amended Motion filed

11/21/07 Motion denied

Florida Supreme Court – 3.851 Appeal

FSC# 08-62

01/11/08 Appeal filed

02/06/09 Disposition affirmed

United States Court of Appeals – Habeas Appeal

USCA# 11-10855 (Pending)

02/22/11 Appeal filed

Death Warrant:

01/07/86 Death Warrant signed by Governor Bob Graham

02/03/86 United States District Court, Middle District, granted a stay of execution

Clemency Hearing:

11/20/85 Clemency hearing denied

Factors Contributing to the Delay in Imposition of Sentence:

The main factor that has contributed to the delay in this case in the fact that Mann has been resentenced twice. Additional factors are the number of appeals that have been filed in addition to the 3.850 Motion that was filed on 04/28/94 was pending for three years and a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus that was pending for eight years in the United States District Court, Middle District.

Case Information:

Mann filed a Direct Appeal to the Florida Supreme Court on 05/04/81. Mann contended that the trial court improperly allowed into evidence the bloodstains found in his truck due to the fact that the blood type matched both him and the victim. The Court ruled that the trial court properly admitted this evidence and found the conviction free from substantive error. The conviction was affirmed. In regard to his sentencing, the Court found that the trial court improperly applied the aggravating factors of prior conviction of a felony involving violence and the homicide to have been committed in a cold, premeditated manner. The Court vacated the sentence and remanded the case to the trial court for a new sentencing proceeding without a jury.

Mann was resentenced to death by the Circuit Court on 01/14/83. He filed a Direct Appeal after resentencing to the Florida Supreme Court on 03/25/83. Mann contended that the Court’s original opinion barred the state from presenting additional evidence at the resentencing. The Court found no error and affirmed the sentence of death.

Mann filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Supreme Court on 10/22/84. The petition was denied on 01/14/84. Governor Graham signed a Death Warrant for Mann on 01/07/86. A 3.850 motion and a stay of execution were filed to the Circuit Court on 01/30/86. The motion and the stay of execution were denied on 01/31/86. On 01/31/86, Mann filed for a stay of execution pending the appeal on 01/31/86, the stay was denied on the same day. On 02/01/86 Mann filed a 3.850 appeal, a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus, and a stay of execution to the Florida Supreme Court. Mann’s main claim was ineffective trial counsel because of his attorney’s failure to object to statements made by the prosecutor during closing arguments of the penalty phase. The Court ruled that these comments did not constitute a reversible error. The Court denied the habeas and the stay and affirmed the trial court’s denial of the 3.850 motion on 02/01/86. No rehearing was allowed and a mandate was issued on 02/10/86.

On 02/03/86, Mann filed a petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus with the United States District Court, Middle District. The District Court granted the stay of execution on 02/03/86, but denied the Habeas on 02/19/86.

On 03/19/86, Mann filed Habeas Appeal to the United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh Circuit. Mann raised only one issue in reference to his conviction. He states that he was involuntarily absent from the jury’s presence when they were allowed to view the crime scene, which violated his rights under the 6th, 8th, and 14th Amendments. The USCA found this to be a harmless error and denied all relief as to his conviction. In regard to his sentence, Mann raised five issues. Three did not entitle Mann to relief, but the claim that the court diminished the jury’s sense of responsibility in imposing the death sentence entitled Mann to relief in the form of a resentencing proceeding. Due to this finding, the USCA stated that the need to render a comment on the fifth issue was moot. The sentence was reversed and the case was remanded to the circuit court for a new jury sentencing proceeding on 05/14/87. On 09/10/87 the previous opinion was vacated and a rehearing en banc was scheduled. The case was reheard en banc on 12/14/87, and a new opinion was issued on 04/02/88 again reversing the sentence and remanding the case to the circuit court for re-sentencing.

The State filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Supreme Court on 06/19/88. The petition was denied on 03/06/89. On 02/06/90, a jury recommended the death penalty by majority. Mann was resentenced to death on Count I, Murder in the First Degree on 03/02/90. Mann filed a Direct Appeal to the Florida Supreme Court on 05/04/90. The Court affirmed the sentence of death on 04/02/92. The rehearing was denied and a revised opinion was issued on 08/27/92. The Court again affirmed the sentence of death. A mandate was issued on 09/28/92. Mann filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Supreme Court on 11/25/92. The petition was denied on 01/19/93.

A 3.850 Motion was filed to the Circuit Court on 04/28/94. The motion was denied in part and an evidentiary hearing was granted. The motion was denied on 03/27/97. A 3.850 Appeal was filed in the Florida Supreme Court on 04/30/97. The appeal was dismissed and CCRC was directed to file an amended 3.850 motion within ten days on 06/25/97. An amended 3.850 Motion was filed to the Circuit Court on 07/07/97. The motion was granted in part and an evidentiary hearing was granted on 07/29/98. The evidentiary hearing was held on 12/01/98 and the motion was denied on 01/13/99. A 3.850 Appeal was filed in the Florida Supreme Court on 02/15/99. Mann raised ten issues. The Court found five to be procedurally barred and the remaining issues without merit. On 09/28/00, they affirmed the trial court’s denial of the 3.850 Motion. The rehearing was denied on 10/31/00, and the mandate was issued on 11/27/00.

Mann filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus on 12/20/00 to the Florida Supreme Court. The State claimed that the Florida Rule of Appellate Procedure 9.140 bars Mann’s Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus. The Court did not bar the petition under Rule 9.140, but stated that as of 01/01/02, all petitions for extraordinary relief must be filed simultaneously with the initial brief appealing the denial of a rule 3.850 Motion. The Court accepted the Petition and addressed Mann’s five issues. The claims raised were either without merit, rejected, or procedurally barred; therefore, the Court denied the petition on 07/12/01. The rehearing was denied on 09/05/01. Mann filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Supreme Court on 11/28/01. The petition was denied on 06/28/02. Mann filed a 3.851 Motion to the State Circuit Court on 08/06/02. The motion was denied on 10/22/02.

On 08/09/02, Mann filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus to the United States District Court, Middle District. It was administratively closed on 08/16/02 due to pending cases in the Circuit Court. The case was reopened on 11/18/04. The petition was amended on 01/18/05. On 11/10/10, the petition was denied. A Motion to Alter Judgment was filed on 12/09/10, and it was denied on 01/21/11. A Certificate of Appealability was filed on 02/22/11. Mann filed a 3.850 Appeal to the Florida Supreme Court on 03/17/03. The Court affirmed the trial court’s denial of Mann’s 3.850 Motion. On 04/16/07, a 3.851 motion was filed with the State Circuit Court. Mann amended this motion on 09/21/07. This successive motion was denied 11/21/07. On 01/11/08, Mann filed a 3.851 Appeal to the Florida Supreme Court. On 02/06/09, the Florida Supreme Court affirmed disposition of the State Circuit Court. Mann filed a Habeas Appeal in the United States Court of Appeals on 02/22/11. This case is currently pending.

Mann v. State, 420 So.2d 578 (Fla. 1982). (Direct Appeal)

Defendant was convicted before the Circuit Court, Pinellas County, Philip A. Federico, J., of first-degree murder, with capital punishment imposed, and defendant appealed. The Supreme Court held that: (1) although defendant and victim had same blood type and enzymes, evidence that several bloodstains found at scene matched those found on seat of defendant's truck was relevant; (2) although evidence at sentencing phase of Mississippi burglary prosecution showed that during burglary defendant had committed sexual battery on an occupant that conviction did not constitute an aggravating circumstance of prior conviction of a felony involving use of threat or violence of person; (3) findings in regard to death sentence should be of unmistakable clarity; and (4) trial court improperly found homicide to have been committed in a cold, calculated, premeditated manner. Conviction affirmed; sentence vacated for new sentencing proceeding. Alderman, C.J., concurred in part and dissented in part with an opinion in which Adkins and Boyd, JJ., concurred.

PER CURIAM.

This is an appeal from a conviction of first-degree murder and a sentence of death. We have jurisdiction FN1 Art. V, § 3(b)(1), Fla.Const., and affirm the conviction but vacate the sentence.

On November 4, 1980 ten-year-old Elisa Nelson was abducted while bicycling to school after a dentist's appointment. Her bicycle was found later that day, and searchers found her body the following day. She died from a skull fracture and had been stabbed and cut several times. The afternoon of the 4th Mann attempted to commit suicide. The police took him to a hospital where he stayed several days. On November 8th Mann's wife, while looking in his pickup truck for his eyeglasses, found a bloodstained note written by Elisa's mother explaining her daughter's tardiness because of the dentist's appointment. The police obtained a warrant to search Mann's truck and home and arrested him on the 10th.

The jury convicted Mann of first-degree murder and recommended the death penalty. The trial court agreed with the recommendation, finding four aggravating factors FN2 and, possibly, one mitigating circumstance. FN3 On appeal Mann alleges one trial error and seven sentencing errors. FN2. Prior conviction of violent felony; felony murder; heinous, atrocious, and cruel; and cold, calculated, and premeditated. FN3. Psychotic depression and paranoid feelings of rage.

The claimed trial error is that the trial court should not have allowed into evidence the fact that several bloodstains found at the crime scene and on the seat of Mann's truck matched the bloodtype of and had the same type of enzymes as the victim. Mann agrees that such evidence would normally be admitted as relevant, but in this case his bloodtype and type of enzymes are the same as those of the victim. He argues, therefore, that this evidence tends to prove nothing, particularly since he presented evidence that he had, prior to the homicide, bled profusely in the truck from an injury. He argues that, since it is equally as likely that the blood was his as that of the victim, the bloodstains in the truck were irrelevant and should have been excluded.

The court properly admitted this evidence. Relevant evidence is evidence tending to prove a material fact and is admissible, except as provided by law. §§ 90.401, 94.402, Fla.Stat. (1979). The bloodstained note had been found in the truck; the fact of blood in the truck had some relevance whether it came from the victim or from Mann. If it were the victim's, it was evidence of her or her body being in the truck; if Mann's, it could explain the blood on the note. Either theory tended to prove some connection between Mann and the victim. In addition to this claimed trial error we have independently reviewed the record to assure ourselves of the propriety of the conviction. We find the conviction supported by competent, substantial evidence, free from substantive error, and affirm it. Mann's main arguments center upon the imposition of the death penalty. His first contention is that the trial judge allowed inadmissible testimony in connection with a prior felony conviction in Mississippi to be introduced into evidence, compounded that error when he found that Mann had been convicted of a burglary during the course of which he used violence, and then used that fact as an aggravating factor in his sentencing order.

One of the aggravating circumstances that a trial judge may consider in determining whether or not to impose the death penalty is set out in section 921.141(5)(b), Florida Statutes (1979): “The defendant was previously convicted of another capital felony or of a felony involving the use or threat of violence to the person.” Mann had been convicted in Mississippi of the crime of burglary, an offense that, standing alone, would not fall within the foregoing definition. Lewis v. State, 398 So.2d 432 (Fla.1981). See Ford v. State, 374 So.2d 496 (Fla.1979), cert. denied, 445 U.S. 972, 100 S.Ct. 1666, 64 L.Ed.2d 249 (1980).

The facts adduced at the sentencing phase of the trial showed that during that burglary the defendant committed a sexual battery upon the occupant of the house he burglarized. Had he been convicted of that sexual battery, the aggravating factor would apply. We must determine whether on sentencing it is proper, in an effort to prove conviction of a prior felony involving the use or threat of violence, to show what actually transpired when the conviction itself was for a crime which, by itself, is not a crime involving the use of violence. Must the conviction itself have inherently included a prior jury's determination of violence, or is it enough to show a prior conviction and let the sentencing jury find, based upon the evidence, whether that prior conviction included violence? Section 921.141(5)(b) does not contain the “during which” language utilized by the trial judge. We are not presented with a copy of the Mississippi charge document and, thus, cannot determine whether it alleged, and the jury convicted him of, a breaking with intent to commit a crime of violence. The record of Mann's conviction, as presented to this Court, does not disclose a conviction of a crime of violence. We hold that a prior conviction of a felony involving violence must be limited to one in which the judgment of conviction discloses that it involved violence.FN4 On the record in this case the trial judge improperly found prior conviction of a felony involving violence. FN4. Such as a conviction under § 810.02(2)(a), Fla.Stat.

Another area of concern is the trial judge's attention to Mann's evidence in mitigation. This is particularly significant because it relates to the properly found aggravating circumstance of the crime being especially heinous, atrocious, and cruel. There is frequently a significant connection between the grossness of a homicide and the perpetrator's mental condition. A psychiatrist testified that Mann's mental condition was of such a nature that he was under the influence of extreme mental or emotional disturbance when he committed this atrocity and that his capacity to appreciate the criminality of his conduct or to conform his conduct to the requirements of law was substantially impaired. § 921.141(6)(b), (f). Although this witness was cross-examined, his opinions were neither rebutted nor contradicted by another witness. The trial judge's reference to the testimony is:

The only mitigating circumstance apparent to the Court which is based solely upon the opinion of Dr. Alfred Fireman, a local psychiatrist, is that the defendant suffered from psychotic depression and paranoid feelings of rage against himself because of strong pedophilic urges. From this we are unable to discern if the trial judge found that the mental mitigating circumstances did not exist. If so it appears that he misconstrued the doctor's testimony. On the other hand, he may have found them to exist and weighed them against the proper aggravating circumstances. We, however, cannot tell which occurred. The trial judge's findings in regard to the death sentence should be of unmistakable clarity so that we can properly review them and not speculate as to what he found; this case does not meet that test.

We also find that the trial court improperly found the homicide to have been committed in a cold, calculated, premeditated manner. § 921.141(5)(i). The state's evidence failed to support finding this aggravating circumstance. See Jent v. State, 408 So.2d 1024 (Fla.1981). We find Mann's other sentencing challenges to be without merit.

The conviction is affirmed, but the sentence is vacated. The trial court is directed to conduct a new sentencing proceeding without a jury. It is so ordered. OVERTON, SUNDBERG, McDONALD and EHRLICH, JJ., concur. ALDERMAN, C.J., concurs in part and dissents in part with an opinion, with which ADKINS and BOYD, JJ., concur.

ALDERMAN, Chief Justice, concurring in part, dissenting in part.

I concur with the affirmance of Mann's conviction for first-degree murder, but I dissent to the reversal of his death sentence and the remand for a new sentencing hearing. I believe the trial court properly found the aggravating circumstance that Mann was previously convicted of a felony involving the use or threat of violence to the person. This previous crime was described by the trial court as follows:

In 1973 the defendant was convicted of the crime of burglary in Mississippi during the course of which, through threats and actual physical force, he had the victim perform fellatio upon him resulting in his ejaculation in her mouth. That victim, Deborah Richards (now Deborah Johnson), was produced by the State to testify in the penalty phase of this trial as to the above facts. The force used involved choking, hair pulling and throwing the victim across the room. The defendant was sentenced to nine (9) years imprisonment and was paroled after serving four (4) years.

Although burglary will not necessarily be a crime of violence as contemplated by this aggravating circumstance, in the present case the State proved beyond a reasonable doubt that the felony of burglary for which Mann was previously convicted involved “the use or threat of violence.” The trial court, in its findings in support of the death penalty, clearly delineated an adequate factual basis for a finding of this aggravating circumstance. I disagree with the majority's holding that this aggravating circumstance was improperly found to exist. It is not a necessary predicate to this aggravating circumstance that the judgment of conviction of the prior felony disclose that it involved violence as suggested by the majority. Rather, it is sufficient that the State prove beyond a reasonable doubt, as it did in this case, that the defendant was previously convicted of another felony and that while committing that felony the defendant used or threatened to use violence to another person.

The majority acknowledges that the trial court properly found as aggravating circumstances that the capital felony committed by Mann was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel and that the murder was committed while Mann was engaged in a kidnapping. The majority, however, expresses concern about the trial court's attention to Mann's evidence in mitigation. It notes that there is frequently a significant connection between the grossness of a homicide and the perpetrator's mental condition. In this case, the trial court, in support of its finding that this murder was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel, explained that the victim, a 10-year-old girl, sustained a 3 1/4-inch cut on the right side of her neck and a 4 1/2-inch cut on the left side of her neck, which cuts produced great pain and severe bleeding and that the victim was conscious for at least several minutes before elapsing into unconsciousness due to loss of blood. The court further stated that death was produced as the result of a massive skull fracture caused by blunt trauma. This was a proper finding. The heinousness, atrociousness, or cruelness of Mann's acts is determined on the basis of what Mann did and its effect on the victim. Diminished mental capacity does not abrogate this aggravating factor. A legally sane but mentally ill defendant who commits an especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel murder will have this aggravating factor weighed against him even though his mental illness contributed to the heinousness, atrociousness, or cruelness of his actions. Evidence of his mental condition is only to be considered in determining whether a mitigating circumstance is proven. Such evidence is not relevant in determining whether the murder is especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel.

In the present case the trial court considered the evidence offered in mitigation as to defendant's mental or emotional disturbance and expressly found as the sole mitigating factor that Mann suffered from psychotic depression and paranoid feelings of rage against himself because of strong pedophilic urges. It then weighed this mitigating factor against the aggravating factors and found that the aggravating factors far outweighed the mitigating.

Even if the trial court's finding that this murder was committed in a cold, calculated, and premeditated manner was not proven beyond a reasonable doubt by the State, as the majority holds, the elimination of this aggravating factor from the weighing process does not require a reversal of the death sentence. The court validly found that Mann had been previously convicted of another felony involving the use or threat of violence to the person, that the murder was committed while Mann was engaged in a kidnapping, and that the murder was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel. These aggravating circumstances, coupled with the jury's recommendation of death, are more than sufficient to outweigh the very weak mitigating circumstance found in this case and to warrant imposition of the death penalty. This case should not be remanded for resentencing.

I not only would affirm Mann's conviction but also would affirm his sentence of death. ADKINS and BOYD, JJ., concur.

Mann v. State, 453 So.2d 784 (Fla. 1984). (Direct Appeal - After Resentencing)

Defendant was convicted in the Circuit Court, Pinellas County, Philip A. Federico, J., of first-degree murder, with capital punishment imposed, and defendant appealed. The Supreme Court, 420 So.2d 578, affirmed conviction but vacated sentence and remanded for new sentencing proceeding. On remand, the Circuit Court again sentenced defendant to death, and he appealed. The Supreme Court held that: (1) evidence was sufficient to support finding of aggravating circumstance of previous conviction of violent felony; (2) introduction of additional evidence at resentencing was proper; and (3) finding that three established aggravating circumstances outweighed single mitigating circumstance supported death sentence. Affirmed.

PER CURIAM.

A jury convicted Mann of first-degree murder and kidnapping and recommended the death penalty. The trial court sentenced Mann to death for the murder and to ninety-nine years for the kidnapping. On appeal we affirmed the convictions, but vacated the death sentence and remanded for resentencing. Mann v. State, 420 So.2d 578 (Fla.1982). On remand the trial court conducted a new sentencing proceeding without a jury and again sentenced Mann to death. We have jurisdiction pursuant to article V, section 3(b)(1) of the Florida Constitution and affirm the death sentence.

In Mann's original sentencing proceeding the state introduced a copy of a conviction showing that Mann had been convicted of burglary in Mississippi. The state also presented evidence (testimony of the victim) to show that Mann committed a sexual battery upon the occupant of the house he burgled. Relying on this conviction and supporting evidence, the trial court found that the aggravating circumstance of previous conviction of a violent felony had been established. § 921.141(5)(b), Fla.Stat. (1979). On appeal we held that the trial court had erroneously found this aggravating circumstance because burglary is not a crime of violence on its face. 420 So.2d at 580. We also held that the trial court had improperly found the establishment of another aggravating circumstance and that we could not tell what the trial court found regarding the mitigating evidence that Mann presented. We therefore vacated the sentence and remanded for resentencing.

On resentencing the trial court deleted the second improper aggravating factor and specifically found in mitigation that Mann suffered from psychotic depression and feelings of rage. The court also again found that the prior Mississippi conviction established the aggravating factor of previous conviction of a violent felony. We hold that this aggravating circumstance has now been established.

Besides relying on the evidence presented in the first sentencing proceeding, at resentencing the state introduced a copy of a Mississippi indictment charging Mann with burglary both with the intent to commit unnatural carnal intercourse and that he did commit that crime against a named female person. Mann now claims that our first opinion precluded the state from presenting additional evidence. We disagree. Our remand directed a new sentencing proceeding, not just a reweighing. In such a proceeding both sides may, if they choose, present additional evidence. Moreover, as we stated previously: “We are not presented with a copy of the Mississippi charge document and, thus, cannot determine whether it alleged, and the jury convicted him of, a breaking with intent to commit a crime of violence.” Id. at 581. The state remedied this omission on resentencing, and the proof-the indictment, the conviction, and the victim's testimony-establishes a prior conviction of a violent felony.

In aggravation the trial court also again found the murder to have been committed during the course of a kidnapping and to have been especially heinous, atrocious, and cruel. He found that the three established aggravating circumstances outweighed the single mitigating circumstance and again sentenced Mann to death. Compare Adams v. State, 412 So.2d 850 (Fla.1982) (eight-year-old girl strangled, mitigating circumstances of emotional disturbance outweighed by aggravating circumstances). We find no error and affirm the sentence.

It is so ordered. ALDERMAN, C.J., and ADKINS, BOYD, OVERTON, McDONALD, EHRLICH and SHAW, JJ., concur.

Mann v. State, 482 So.2d 1360 (Fla. 1986). (PCR)

Petitioner, who was scheduled for execution, sought postconviction relief. The Circuit Court, Pinellas County, Philip A. Federico, J., denied petitioner's motion for relief. Defendant appealed, and filed petition for habeas corpus in the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court held that: (1) evidentiary hearing was not required on petition for postconviction relief; (2) trial judge did not abuse his discretion by not having oral argument on postconviction relief petition; (3) it was not appropriate in collateral attack on death sentence to attempt to collaterally attack petitioner's prior conviction of a crime of violence in a foreign jurisdiction; and (4) it was proper to fail to delay execution of sentence prior to ruling in that jurisdiction on collateral attack on the prior conviction. Order denying postconviction relief affirmed; habeas corpus denied; stay of execution denied.

Mann v. State, 603 So.2d 1141 (Fla. 1992). (Direct Appeal - After Resentencing)

Conviction for murder and kidnapping was affirmed, but sentence of death was reversed by the Florida Supreme Court, 420 So.2d 578. Following reimposition of death penalty, Florida Supreme Court affirmed, 453 So.2d 784. Petition for habeas corpus was denied by the United States District Court for the Middle District of Florida, Elizabeth A. Kovachevich, J., and appeal was taken. The Court of Appeals, 817 F.2d 1471, 828 F.2d 1498, 844 F.2d 1446, reversed and remanded with instructions to set aside death sentence unless state afforded new sentencing proceeding. Defendant was sentenced to death in the Circuit Court, Pinellas County, James R. Case, C.J., and he appealed. The Supreme Court held that: (1) detective's testimony was harmless on remorse issue, even if it was comment on right to remain silent; (2) prosecutor's closing argument that psychologist suggested that defendant's actions were more excusable because he was “child molester” and “pervert” was permissible; and (3) any error in instruction on felony-murder aggravator of murder being committed during kidnapping was harmless. Affirmed.

PER CURIAM.

Larry Mann appeals his death sentence imposed on resentencing. We have jurisdiction pursuant to article V, section 3(b)(1), Florida Constitution, and affirm.

A jury convicted Mann of kidnapping and first-degree murder in the death of a ten-year-old girl, and the trial court sentenced him to death. This Court affirmed the conviction, but remanded for resentencing. Mann v. State, 420 So.2d 578 (Fla.1982).FN1 On remand the trial court again sentenced Mann to death, and this Court affirmed. Mann v. State, 453 So.2d 784 (Fla.1984), cert. denied, 469 U.S. 1181, 105 S.Ct. 940, 83 L.Ed.2d 953 (1985). After the signing of his death warrant in 1986, Mann filed a motion for postconviction relief with the trial court and a petition for writ of habeas corpus with this Court. This Court affirmed the trial court's denial of relief and denied the habeas petition. Mann v. State, 482 So.2d 1360 (Fla.1986). Mann received a stay of execution in the federal system, however, and the circuit court of appeal eventually decided that his jury had been misinformed as to its role in sentencing and directed that he be resentenced. Mann v. Dugger, 844 F.2d 1446 (11th Cir.1988), cert. denied, 489 U.S. 1071, 109 S.Ct. 1353, 103 L.Ed.2d 821 (1989). FN1. The facts are set out in this original opinion.

Numerous witnesses testified at the new penalty phase. Among other people, the lead detective of the investigation and several technicians testified as to the circumstances of the crime. The medical examiner described the victim's injuries and told the jury that she died from a skull fracture after being cut and beaten. Mann had been convicted of burglary in Mississippi, and his victim testified to the circumstances of that crime to prove that it was a crime of violence. Several family members and other people testified in Mann's behalf, describing his life, how they thought he had grown as a person since being imprisoned, and his expressions of remorse for committing this murder. A psychologist opined that Mann is an alcoholic and a pedophile but had no brain damage. She also thought that the statutory mental mitigators FN2 should be applied to Mann. On cross-examination she stated that Mann abducted the victim because he wanted to molest her. In rebuttal the prosecution presented a psychologist, who testified that Mann is a pedophile and substance abuser, that he is antisocial, and that the mental mitigators did not apply in this case. Two other witnesses testified that they received no indication that Mann was drunk the morning he committed this crime.

FN2. The mental health mitigators are: “The capital felony was committed while the defendant was under the influence of extreme mental or emotional disturbance” and “[t]he capacity of the defendant to appreciate the criminality of his conduct or to conform his conduct to the requirements of law was substantially impaired.” § 921.141(6)(b), (f), Fla.Stat. (1989).

After hearing all of the testimony, the jury recommended that Mann be sentenced to death. In his written findings the trial judge found that Mann had a prior violent felony conviction, that he committed this murder during the commission of a felony, and that this murder was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel. The judge found that no statutory mitigators had been established, but that the following nonstatutory mitigators had been: Mann suffered from psychotic depression and feelings of rage against himself because of strong pedophilic urges; Mann had been an exemplary inmate; he had a long history of alcohol and drug dependency; he had demonstrated great remorse; he had developed his artistic talents; and he had maintained a relationship with his family and friends. Characterizing these mitigators as “unremarkable,” however, the judge found that they did not outweigh the aggravators and that the death penalty was appropriate.