40th murderer executed in U.S. in 2006

1044th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

4th murderer executed in Oklahoma in 2006

83rd murderer executed in Oklahoma since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

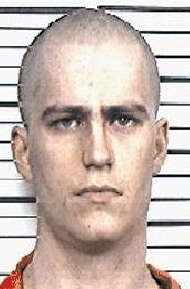

James Patrick Malicoat W / M / 21 - 31 |

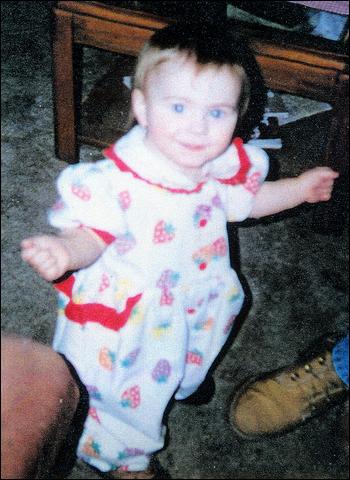

Tessa Leadford W / F / 13 mo |

Summary:

Malicoat was alone at home with his 13 month old daughter, Tessa Leadford, while her mother was at work. He had lived with Tess and her mother for 19 days, worked nights and cared for the child during the day. According to the medical examiner’s report, Tessa died from two subdural hematomas and abdominal bleeding caused by injuries Malicoat inflicted. She also had broken ribs, bite marks and extensive bruising to her face and body. Malicoat admitted hitting her head on a dresser a few days before she died and punching her twice in the stomach the day she died, causing her to stop breathing. Malicoat used CPR to revive her before lying down beside her to take a nap. When he awoke, Malicoat noticed she was dead. He put her in her crib and covered her with a blanket before going back to sleep. When Leadford’s mother returned from work, the couple rushed the child to the emergency room, but staff there determined she had been dead for several hours. Mary Leadford was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison for her role in the death of her daughter.

Citations:

Malicoat v. State, 992 P.2d 383 (Okla.Crim.App. 2000) (Direct Appeal).

Malicoat v. State 137 P.3d 1234 (Okla.Crim.App. 2006) (PCR).

Malicoat v. Mullin 426 F.3d 1241 (10th Cir. 2005) (Habeas).

Final/Special Meal:

Fried chicken, mashed potatoes and gravy, corn on the cob, biscuits, Dr Pepper and an apple pie.

Final Words:

"I just want everybody to know how sorry I am this thing had to happen; any of it. I am sorry I caused the death of another human being. There is nothing I can do to change it. Contrary to what some people believe I spent many years going over it in my head. It's never left me."

Internet Sources:

Oklahoma Department of Corrections

Inmate: JAMES P MALICOAT

ODOC#: 261820

Birth Date: 05/04/1975

Race: White

Sex: Male

Height: 6 ft. 01 in.

Weight: 155 pounds

Hair: Brown

Eyes: Green

County of Conviction: Grad

Date of Conviction: 01/06/98

Location: Oklahoma State Penitentiary, Mcalester

"Okla. man executed for baby daughter beating death." (Thu Aug 31, 2006 8:15pm ET)

McALESTER, Oklahoma (Reuters) - Oklahoma executed a confessed child murderer on Thursday for the 1997 beating death of his 13-month-old daughter. James Malicoat, 31, was condemned for beating Tessa Leadford to death at his home in the south-central Oklahoma town of Chickasha on February 21, 1997 while the girl's mother was at work.

Malicoat admitted slamming Leadford's head into a dresser a few days before she died and punching her in the stomach so hard she stopped breathing on the day of her death. Malicoat tried to resuscitate Leadford but when he was unable to revive her, he laid her in her crib and went to bed. When Tessa's mother Mary Ann Leadford came home from work and found the girl not breathing, she and Malicoat rushed the baby to a hospital emergency room.

Investigators said the extensive bruising on Tessa Leadford's body, bite marks and two broken ribs indicated she had been abused repeatedly for days prior to her death. Mary Ann Leadford was convicted of first-degree murder for her role in her daughter's death and is serving a life sentence.

On Thursday, while strapped to a gurney in the death chamber shortly before his execution, Malicoat apologized for the murder. "I just want everybody to know how sorry I am this thing had to happen; any of it," he said. "I am sorry I caused the death of another human being. There is nothing I can do to change it. Contrary to what some people believe I spent many years going over it in my head. It's never left me."

Malicoat was the 83rd person executed in Oklahoma since the state resumed capital punishment in 1990.

For his last meal, Malicoat requested fried chicken, mashed potatoes and gravy, corn on the cob, biscuits, Dr Pepper and an apple pie.

Oklahoma Attorney General (Press Release)

W.A. Drew Edmondson, Attorney General

"Execution Date Requested for Malicoat."

06/05/2006 - Attorney General Drew Edmondson today asked the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals to set an execution date for Grady County death row inmate James Patrick Malicoat.

Malicoat, 31, was convicted of the Feb. 21, 1997, murder of his 13-month-old daughter, Tessa Leadford, in his Chickasha home. According to the medical examiner’s report, Leadford died from two subdural hematomas and abdominal bleeding caused by injuries Malicoat inflicted as he cared for the child while her mother was at work. Leadford also had broken ribs, bite marks and extensive bruising to her face and body.

Malicoat admitted hitting Leadford’s head on a dresser a few days before she died and punching her twice in the stomach the day she died, causing her to stop breathing. Malicoat used CPR to revive her before lying down beside her to take a nap. When he awoke, Malicoat noticed Leadford was dead. He put her in her crib and covered her with a blanket before going back to sleep. When Leadford’s mother returned from work, the couple rushed the child to the emergency room, but staff there determined she had been dead for several hours.

Edmondon requested the execution date after the U.S. Supreme Court rejected Malicoat’s final appeal. He requested the date be set for “60 days after June 5, 2006, or at the earliest date this Court deems fit.”

Edmondson May 30 requested an execution date for Oklahoma County death row inmate Eric Allen Patton. That request is still pending before the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals.

“It is the practice of this office, before an execution date is requested, to examine each case to determine if the testing of DNA evidence should occur,” said Edmondson. “We have determined, after a thorough review of this case, that DNA testing would be of no value and would have no relevance as to actual innocence. I see nothing that should stand in the way of this execution being carried out.”

"Toddler's killer is put to death." (By AP Wire Service 9/1/2006)

"James Malicoat's execution is the state's fourth this year and the second in three days."

McALESTER (AP) -- A Chickasha man who was convicted of killing his 13-month-old daughter nearly 10 years ago was executed Thursday evening at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary. James Patrick Malicoat, 31, was pronounced dead at 6:09 p.m., four minutes after receiving a lethal dose of drugs. Malicoat was executed for the beating death of Tessa Leadford, whom authorities said had been in her father's care for 19 days. During that time she suffered abdominal bleeding, broken ribs, bite marks and extensive bruising.

When the curtains to the execution chamber were lifted, Malicoat -- strapped to a gurney and wearing glasses -- turned his head to the witness room, smiled and gave a small wave. In his final words, he expressed remorse. "I just want to tell everyone how sorry I am that this had to have happened, any of it," Malicoat said to the witnesses, who including two of his spiritual advisers and three of his attorneys. "I'm sorry I caused the death of another human, but there's nothing I can do to change it. Contrary to what some people believe, I have spent very many years going over it in my head, and it's never left me. I hope someday people involved in it will move on." He thanked his witnesses for supporting him, then said, "That's just about it." He smiled at the witnesses again, then turned his head and looked at the ceiling as the drugs began being administered. He took two deep breaths and closed his eyes and appeared to stop breathing moments later. "He died within a few seconds of injection," said Grady County District Attorney Bret Burns, who helped prosecute Malicoat and attended the execution. "You can't say that for his victim. Tessa took 19 days to die."

No members of Tessa's family attended the execution, nor did Malicoat's mother, Reta Luther.

The five-member state Pardon and Parole Board unanimously denied clemency to Malicoat on Aug. 1, even after Tessa's mother, Mary Ann Leadford, and other family members pleaded with the board to spare his life. Leadford, convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison for her daughter's death, said in a videotape that Malicoat should spend the rest of his life in prison and live with his pain.

"As hard as it is, I have forgiven him," she said. "I don't think he should die."

Malicoat was the fourth inmate to be executed this year in Oklahoma, coming two days after Eric Allen Patton -- convicted of the December 1994 murder of Charlene Elizabeth Kauer in Oklahoma City -- was put to death.

"Chickasha man executed," by Murray Evans. (Associated Press Web-Posted Sep. 01, 2006 03:35: AM)

McALESTER (AP) -- A Chickasha man who was convicted of killing his 13-month-old daughter nearly 10 years ago was executed Thursday evening at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary. James Patrick Malicoat, 31, was pronounced dead at 6:09 p.m. CDT, four minutes after receiving a lethal dose of drugs. Malicoat was executed for the beating death of Tessa Ledford, whom authorities said had been in her father's care for 19 days. During that time she suffered abdominal bleeding, broken ribs, bite marks and extensive bruising.

When the curtains to the execution chamber were lifted, Malicoat -- strapped to a gurney and wearing glasses -- turned his head to the witness room, smiled and gave a small wave. In his final words, Malicoat expressed remorse for his crime. "I just want to tell everyone how sorry I am that this had to have happened, any of it," Malicoat said to the witnesses, who including two of his spiritual advisers, three of his attorneys and two other people connected to him. "I'm sorry I caused the death of another human, but there's nothing I can do to change it. Contrary to what some people believe, I have spent very many years going over it in my head and it's never left me. I hope someday people involved in it will move on." He thanked the witnesses who came to support him, then said, "That's just about it."

He smiled at the witnesses again, then turned his head and looked at the ceiling as the drugs began being administered. He took two deep breaths and closed his eyes, and appeared to stop breathing moments later. "He died within a few seconds of injection," said Grady County District Attorney Bret Burns, who helped prosecute Malicoat and attended the execution. "You can't say that for his victim. Tessa took 19 days to die."

Burns said he respected Malicoat for offering remorse, but that Malicoat needed to be executed for his crime.

No members of Tessa's family attended the execution, and neither did Malicoat's mother, Reta Luther.

On Aug. 1, the five-member state Pardon and Parole Board unanimously denied clemency to Malicoat, even after Tessa's mother, Mary Ann Leadford, and other family members pleaded with the board to spare Malicoat's life.

Mary Leadford, convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison for her daughter's death, said in a videotape that Malicoat should spend the rest of his life in prison and live with his pain.

"As hard as it is, I have forgiven him. I don't think he should die," Leadford said.

Malicoat was the fourth inmate to be executed this year in Oklahoma, coming two days after Eric Allen Patton -- convicted of the December 1994 murder of Charlene Elizabeth Kauer in Oklahoma City -- was put to death.

Malicoat's execution had been scheduled for Aug. 22, but the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals delayed it to allow Malicoat to give a deposition in the competency hearing for another death-row inmate, Garry Thomas Allen.

In one of Malicoat's earlier appeals, he had claimed that Oklahoma's use of lethal injection as an execution method constituted cruel and unusual punishment. The state Court of Criminal Appeals in a unanimous June 19 ruling disagreed, saying the method was constitutional and that the lethal injection process "comports with contemporary standards of decency."

A new lethal drug recipe, which was to deliver a larger dose of anesthesia before the fatal drugs are administered, was first used during Patton's execution.

"Chickasha man executed for death of daughter," by Murray Evans. (Associated Press Thu August 31, 2006)

McALESTER, Okla. - A Chickasha man who was convicted of killing his 13-month-old daughter nearly 10 years ago was executed Thursday evening at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary.

James Patrick Malicoat, 31, was pronounced dead at 6:09 p.m. CDT, four minutes after receiving a lethal dose of drugs.

Malicoat was executed for the beating death of Tessa Leadford, whom authorities said had been in her father's care for 19 days. During that time she suffered abdominal bleeding, broken ribs, bite marks and extensive bruising.

When the curtains to the execution chamber were lifted, Malicoat _ strapped to a gurney and wearing glasses _ turned his head to the witness room, smiled and gave a small wave.

In his final words, Malicoat expressed remorse for his crime.

"I just want to tell everyone how sorry I am that this had to have happened, any of it," Malicoat said to the witnesses, who including two of his spiritual advisers, three of his attorneys and two other people connected to him.

"I'm sorry I caused the death of another human, but there's nothing I can do to change it. Contrary to what some people believe, I have spent very many years going over it in my head and it's never left me. I hope someday people involved in it will move on."

He thanked the witnesses who came to support him, then said, "That's just about it."

He smiled at the witnesses again, then turned his head and looked at the ceiling as the drugs began being administered. He took two deep breaths and closed his eyes, and appeared to stop breathing moments later.

"He died within a few seconds of injection," said Grady County District Attorney Bret Burns, who helped prosecute Malicoat and attended the execution. "You can't say that for his victim. Tessa took 19 days to die."

Burns said he respected Malicoat for offering remorse, but that Malicoat needed to be executed for his crime.

No members of Tessa's family attended the execution, and neither did Malicoat's mother, Reta Luther.

Outside the prison gates, a prayer vigil was held for Tessa's family and Malicoat. Bryan Brooks, the pastor of St. Joseph Catholic Church in Muskogee, said 10 similar vigils were being held at places across the state, including the Governor's Mansion in Oklahoma City.

"For us as Catholics, it's part of our way of showing we believe in the dignity of all human life," Brooks said. "We believe that all human life is sacred and that each and every person has dignity from the moment of conception until a natural death, both victims of violence and people executed because of those murders."

For his final meal request, Malicoat asked for fried chicken, mashed potatoes, corn on the cob, biscuits, a large Dr Pepper and a mini apple pie, Corrections Department spokesman Jerry Massie said.

On Aug. 1, the five-member state Pardon and Parole Board unanimously denied clemency to Malicoat, even after Tessa's mother, Mary Ann Leadford, and other family members pleaded with the board to spare Malicoat's life.

Mary Leadford, convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison for her daughter's death, said in a videotape that Malicoat should spend the rest of his life in prison and live with his pain.

"As hard as it is, I have forgiven him. I don't think he should die," Leadford said.

Malicoat was the fourth inmate to be executed this year in Oklahoma, coming two days after Eric Allen Patton _ convicted of the December 1994 murder of Charlene Elizabeth Kauer in Oklahoma City _ was put to death.

Malicoat's execution had been scheduled for Aug. 22, but the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals delayed it to allow Malicoat to give a deposition in the competency hearing for another death-row inmate, Garry Thomas Allen.

In one of Malicoat's earlier appeals, he had claimed that Oklahoma's use of lethal injection as an execution method constituted cruel and unusual punishment. The state Court of Criminal Appeals in a unanimous June 19 ruling disagreed, saying the method was constitutional and that the lethal injection process "comports with contemporary standards of decency."

A new lethal drug recipe, which was to deliver a larger dose of anesthesia before the fatal drugs are administered, was first used during Patton's execution.

"Mother faces son’s execution; Reta Luther won’t watch her son die," by Kent Bush. (Published August 19, 2006 11:50 am)

CHICKASHA — Reta Luther won’t watch her son die. She will be in McAlester on Tuesday, August 22, 2006 - the date the State of Oklahoma has chosen to put her son, James Patrick Malicoat to death. But she won’t walk down the long, gray halls to the execution chamber.

Malicoat asked her not to be there. It would be too hard on her - and him.

Some will be anticipating the announcement of the execution of a monster who beat, bit and tortured a 13-month child to death.

Luther will feel the horror of knowing that only moments remain in her adopted son’s life.

When Malicoat killed his daughter, he took away Luther’s granddaughter. She felt that pain again recently when her step-grandchildren were killed in a fire on Sixth Street in Chickasha.

Luther said she knows what her son did and she agrees he should be punished. But no mother can easily bear the knowledge that her son will soon die.

“It is very hard,” Luther said. “I only go to work and go home. I sleep about two to three hours a night. It is hard to function with that date hanging out there.”

Malicoat has never denied responsibility for the death of Tessa Leadford.

“He says he knows what he did was wrong and he will stand up and take the punishment for it,” Luther said. “He accepts that responsibility.”

In fact, Malicoat didn’t even plead for is life in front of the Pardon and Parole Board.

“I’m not here to ask for my life today. I don’t know if it would do any good,” Malicoat told the board. But he did apologize for the grief he caused family members.

Luther said she believes Malicoat’s childhood contributed to his horrible act which led to his execution. He was adopted when he was 18-months old.

She said his father, who was later convicted of child abuse, was very abusive toward the young Malicoat.

She recalled a time where he was five years old and he was stripped down and forced to break ice in a horse trough. She also recalls when he was beaten with a two-by-four for putting a screw into the wall incorrectly. She said the father never treated his two natural children the same way he did his adopted son. But Malicoat has never said that is why he believes he committed the murder.

“I have no idea why I did it. I have no idea why it happened. I’ve tried to find an answer for it for nine and a half years,” he said recently.

Since his conviction in 1997, Malicoat has never been outside. The closest he has come to being outside is in an exercise room at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary which has a glass ceiling.

He has requested a short trip outdoors before his life is taken, but his mother doesn’t expect that request to be granted.

Luther said the boy she helped raise - now the man the state will execute - is basically a good person who committed one horrible crime.

She said he is a good poet who has a happy attitude and always kept his friends laughing.

“Anyone who knows him will tell you that this is a one time thing,” Luther said. “Since he has been on medication, he is doing better. I don’t think he should die for this.”

But District Attorney Bret Burns, who prosecuted the case in 1997 disagrees.

“I have never seen a case this bad,” Burns said. “He tortured a 13-month old baby to death. Of all the executions I have been a part of, he deserves it more than any of them.”

For now a mother counts the hours, hoping for a last-second decision to spare her son’s life.

Barring an unexpected pardon, Malicoat will be executed at 6 p.m., Tuesday in McAlester.

"Justice for a tortured child?" by Kent Bush. (Published August 26, 2006 11:47 am)

CHICKASHA — He should have been willing to give his life for his daughter. Instead, he took her life. Now James Patrick Malicoat awaits an execution chamber in which the state will attempt to deliver justice to a 13-month-old girl who was tortured to death almost a decade ago. But there will never be justice for Tessa Leadford.

No death suffered by this murderer could bring equity to the beautiful blonde-haired toddler who loved her father - only to be brutally bitten, beaten, broken and betrayed by him.

On that fateful wintry day, Malicoat’s turbulent torture of his own daughter finally ended her life.

The child had bite marks still healing from painful injuries suffered days before.

Her face was bloodied by fingernails jabbed into her face by a man who violently poked her with his fingers to try to stop the child’s crying which was keeping a father who worked nights from being able to sleep.

Her stomach showed more than 30 fresh and healing bruises from fingers thrust into her body so ferociously that seven ribs were broken and her liver, lungs and a kidney were ruptured.

Her head revealed a soft spot just above her right eye where her skull had been crushed by the force of a blow which caused a hemorrhage in her tiny brain.

After one of the blows stopped the child’s breathing, Malicoat told prosecutors that he “revived” his child. When the child’s vital signs returned, he sought no medical care for the mortally wounded child.

He merely poured some soda into a baby bottle, put the bottle in her mouth and placed her in a playpen near his bed.

Malicoat lay down to sleep.

His child would never awaken.

When Malicoat and the child’s mother found her dead several hours later, they called a family member who told them to seek medical care for the child.

ambulance arrived and soon after, so did the police.

Both were convicted for their roles in the girl’s death.

The mother, Mary Ann Leadford, was sentenced to life in jail for not protecting her child from the abuse of which she was keenly aware. A Grady County jury took only half an hour to decide the father’s fate.

He is set to die Thursday in McAlester.

District Attorney Bret Burns prosecuted the case. He said death was the only punishment available that fits this crime.

Malicoat has said himself that only his death can atone for his actions.

However, no painless execution can erase the terror his child experienced the last few weeks of her life. No punishment can rectify the pain and suffering her father inflicted on her and her mother allowed.

The child’s death will be avenged when her father - her killer - succumbs to the highest penalty the laws in a civil society allow.

But there can be no justice for Tessa Leadford.

"Witnessing execution is Burns’ first official act as D.A.," by Jason Clarke. (Published September 01, 2006 03:06 pm)

McALESTER — At 5 p.m. Thursday, Bret Burns officially assumed the duties as District Six District Attorney. At 6 p.m. he watched a man die. Burns was in attendance for the execution of Grady County murderer James Patrick Malicoat. It was a case that he and former-District Attorney Gene Christian prosecuted together.

As the father of a five-year-old when the case was prosecuted in 1998, Burns said it was hard for him personally.

“It was a hard case for everyone involved,” Burns said, “This one pulled at everyone’s heart due to the nature of the charge and the age of the child - 13 months.”

Following the execution, Burns recounted entering the crime scene.

Dog feces littered the floor. More food in the house for the animal than for humans, and no baby food.

Tessa Leadford lived with Malicoat for 19 days of her life.

Everyone of those 19 days was she was tortured, Burns said. Although typically not determined until formal arraignment, stepping into the crime scene, Burns said he knew the punishment he would be pursuing.

“From the day we walked into the crime scene, the day of his arrest we knew we would seek the death penalty,” Burns said.

“It was a gruesome, gruesome crime.”

Nine and a half years later, Burns sat and watch Malicoat received the punishment his office had worked so hard for.

At about 8:25 p.m. on February 21, 1997, James Malicoat and his girlfriend, Mary Ann Leadford, brought their thirteen-month-old daughter, Tessa Leadford, to the county hospital emergency room. Staff there determined Tessa had been dead for several hours. The child's face and body were covered in bruises, there was a large mushy closed wound on her forehead, and she had three human bite marks on her body. Tessa had two subdural hematomas from the head injury, and severe internal injuries including broken ribs, internal bruising and bleeding, and a torn mesentery. After an autopsy the medical examiner concluded the death was caused by a combination of the head injury and internal bleeding from the abdominal injuries.

Tessa and Leadford began living with Malicoat on February 2, 1997. Malicoat, who was severely abused as a child, admitted he routinely poked Tessa hard in the chest area and occasionally bit her both as discipline and in play. Malicoat worked a night shift on an oil rig and cared for Tessa during the day while her mother worked. Malicoat initially denied knowing how Tessa got her severe head injury; he later suggested she had fallen and hit the edge of the waterbed frame, then admitted he hit her head on the bed frame one or two days before she died. Malicoat admitted punching Tessa twice in the stomach, hard, about 12:30 p.m. on February 21, while Leadford was at work. Tessa stopped breathing and he gave her CPR; when she began breathing again, he gave her a bottle and went to sleep next to her on the bed. When he awoke around 5:30 p.m., she was dead. He put Tessa in her crib and covered her with a blanket, then spoke briefly with Leadford and went back to sleep in the living room.

Leadford eventually discovered Tessa and they brought her to the emergency room. Malicoat explained he had worked all night, had car trouble, took Leadford to work, and was exhausted. He hit Tessa when she would not lie down so he could sleep. He said he sometimes intended to hurt Tessa when he disciplined her, but never meant to kill her. His defense was lack of intent; he claimed he had suffered through such extreme abuse as a child that he did not realize his actions would seriously hurt or kill Tessa.

Malicoat's estranged wife testified that he did not pay child support, and that he once grabbed her wrist and fractured it during a fight. She said shortly before their marriage, Malicoat told her he did not like nor want children, and when she became pregnant a month later he said if she did not get rid of the baby that he would when it got here, however there was no evidence Malicoat ever harmed that child. Malicoat's brother testified that Malicoat was "mean enough" to have done the crime and that he liked to beat women.

The medical examiner described the various and extensive internal and external injuries he found on Tessa's body. He said the abdominal injuries were "non-survivable". In his medical opinion, Tessa's symptoms from the injuries would have included brief loss of consciousness, fussy behavior, poor eating, restlessness and eventually sleepiness sliding into a coma. He said the chest injuries would have been quite painful: bruises to the lungs could have caused difficulty breathing, the bruised diaphragm would have made every breath painful, and the broken ribs would have been very painful whenever Tessa breathed or moved. He said the ruptured mesentery and bleeding in the liver and kidneys would have been extremely painful when inflicted, and would have continued to cause cramping and probably a dull aching pain associated with the tearing and gradual loss of blood.

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

James Malicoat, OK August 22

James Malicoat was convicted of killing his 13-month-old daughter in Grady County. On the night of Feb. 20, 1997 Malicoat severely abused his daughter Tessa, causing internal bleeding that over several hours caused her death.

There is no doubt that Malicoat was responsible for the death of his daughter. We must, however, look into why he would commit such a horrendous act. Malicoat was abused as a child. His mother admitted to hitting him at least three times a month and his father hit him more often and much more brutally. Malicoat was repeatedly beaten with wrenches and cattle prods.

James Malicoat did not intend to kill his daughter; this was not a premeditated murder. He testified that he did not know why he beat his daughter but that the episodes would be sporadic and unprovoked. Psychiatrists also testified that men like Malicoat often do not realize what they are doing until the beating is over. In the state of Oklahoma, the only crime punishable by the death penalty is first-degree murder.

Malicoat’s trial was flawed. A sign above the door to the courtroom where Malicoat was convicted read, “An Eye for an Eye a Tooth for a Tooth.” This is a quote from the Bible that had no place in a courtroom of the United States. The quote has obvious implications and violates the separation of church and state that is fundamental to the United States Constitution. The judge who presided over the trial denied the defense’s motion to have the sign taken down. Another judge found this sign to be contemptible, saying, “The sign…. is inappropriate in any criminal court. As I have previously said, in the context of a capital trial I believe the sign is outrageous and unconstitutional.” This sign created a bias against Malicoat. Courts should remain as unbiased as possible, especially when they decide matters of life and death.

James Malicoat did not commit a premeditated crime and he also did not receive an impartial trial that was free of religious influence. Do not let this man be executed without a fair chance to plead for his life.

Please write to Gov. Brad Henry on behalf of James Malicoat

Malicoat v. State, 992 P.2d 383 (Okla.Crim.App. 2000) (Direct Appeal).

Defendant was convicted in the District Court, Grady County, of first-degree child abuse murder, and was sentenced to death. Appeal was taken, and the Court of Criminal Appeals, Chapel, J., held that: (1) trial court properly exercised its discretion to expedite proceedings during voir dire; (2) challenged jurors were not subject to removal for cause; (3) decision to postpone defendant's opening statement until after State had presented its entire case was within court's discretion; (4) improper expert testimony that victim suffered “intentional abuse” was harmless; (5) instruction on lesser included offense of second-degree depraved mind murder was not warranted; (6) evidence supported aggravating circumstances of a continuing threat to society, and an especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel murder; (7) prosecutor's conduct during closing argument did not rise to level of plain error; (8) other acts evidence was properly admitted during penalty phase; (9) improper admission of photograph of victim prior to crime was harmless; (10) photographs of victim's corpse were properly admitted; (11) defendant did not receive ineffective assistance; and (12) sentence was not result of passion and was supported by evidence.

Affirmed.

Lumpkin, V.P.J., concurred in the result.

Lile, J., concurred in the result.

Strubhar, P.J., dissented and filed opinion.

CHAPEL, Judge:

¶ 2 At about 8:25 p.m. on February 21, 1997, Malicoat and his girlfriend, Mary Ann Leadford, brought their thirteen-month-old daughter, Tessa Leadford, to the county hospital emergency room. Staff there determined Tessa had been dead for several hours. The child's face and body were covered in bruises, there was a large mushy closed wound on her forehead, and she had three human bite marks on her body. Tessa had two subdural hematomas from the head injury, and severe internal injuries including broken ribs, internal bruising and bleeding, and a torn mesentery. After an autopsy the medical examiner concluded the death was caused by a combination of the head injury and internal bleeding from the abdominal injuries.

¶ 3 Tessa and Leadford began living with Malicoat on February 2, 1997. Malicoat, who was severely abused as a child, admitted he routinely poked Tessa hard in the chest area and occasionally bit her both as discipline and in play. Malicoat worked a night shift on an oil rig and cared for Tessa during the day while her mother worked. Malicoat initially denied knowing how Tessa got her severe head injury; he later suggested she had fallen and hit the edge of the waterbed frame, then admitted he hit her head on the bed frame one or two days before she died. Malicoat admitted punching Tessa twice in the stomach, hard, about 12:30 p.m. on February 21, while Leadford was at work. Tessa stopped breathing and he gave her CPR; when she began breathing again, he gave her a bottle and went to sleep next to her on the bed. When he awoke around 5:30 p.m., she was dead. He put Tessa in her crib and covered her with a blanket, then spoke briefly with Leadford and went back to sleep in the living room. Leadford eventually discovered Tessa and they brought her to the emergency room. Malicoat explained he had worked all night, had car trouble, took Leadford to work, and was exhausted. He hit Tessa when she would not lie down so he could sleep. He said he sometimes intended to hurt Tessa when he disciplined her, but never meant to kill her. His defense was lack of intent; he claimed he had suffered through such extreme abuse as a child that he did not realize his actions would seriously hurt or kill Tessa.

* * *

In Proposition XII Malicoat argues the evidence in this case was insufficient to support a sentence of death because the prosecution did not prove that he intended to kill Tessa, intentionally employed lethal force against her, or knowingly engaged in criminal activities known to carry a grave risk of death. In Fairchild FN20 this Court held child abuse murder is a general intent crime. Malicoat argues a conviction based on a general intent, or an intent merely to injure, cannot render a defendant death-eligible. He claims that, under the Enmund/Tison FN21 formula, to impose the death penalty the jury must find either (1) he intended life be taken or contemplated that lethal force would be used; or (2) he had substantial personal involvement in the underlying felony and exhibited reckless disregard or indifference to the value of human life. The trial court refused Malicoat's requested Enmund/Tison instructions. We found in Fairchild that these instructions are not necessary when the defendant himself “personally, willfully, commits an act which produces an injury upon a child resulting in the death of the child, or uses unreasonable force upon a child resulting in the death of the child.” FN22 We decline to revisit this finding here. Malicoat admitted hitting Tessa, causing the injuries which resulted in her death. This proposition is denied.

* * *

Malicoat first claims the trial court erred in allowing the medical examiner to testify regarding the pain and suffering Tessa would have experienced as a result of her head and abdominal injuries. Malicoat's repeated objections to this testimony were overruled, and the issue has been preserved for appeal. The medical examiner described the various and extensive internal and external injuries he found on Tessa's body, including injuries to organs with which laypersons are unfamiliar. He said the abdominal injuries were “non-survivable”. In his medical opinion, Tessa's symptoms from the injuries would have included brief loss of consciousness, fussy behavior, poor eating, restlessness and eventually sleepiness sliding into a coma. He said the chest injuries would have been quite painful: bruises to the lungs could have caused difficulty breathing, the bruised diaphragm would have made every breath painful, and the broken ribs would have been very painful whenever Tessa breathed or moved. He said the ruptured mesentery and bleeding in the liver and kidneys would have been extremely painful when inflicted, and would have continued to cause cramping and probably a dull aching pain associated with the tearing and gradual loss of blood. This testimony was admissible as expert opinion evidence.FN35 The average layperson is unfamiliar or only vaguely familiar with several of the organs injured here. Malicoat vigorously argues elsewhere that a reasonable person could not have known the particular injuries he inflicted would have resulted in Tessa's death. While we reject that argument, we agree that the medical examiner's opinion assisted the jury in determining the effects of the wounds Tessa received. The precise locations and consequences of these injuries are not readily appreciable by any ordinary person without the special skills or knowledge necessary to understand these facts and draw the appropriate conclusions.FN36 We disagree with Malicoat's claim that pain is so subjective the medical examiner's opinion amounted to speculation. While the extent to which a particular person feels pain varies, we accept as fact the proposition that certain injuries will cause pain, and that it is possible to determine whether, as a general rule, that pain is more or less severe. This evidence assisted the jury in determining whether Tessa's death was heinous, atrocious or cruel. The trial court did not err in overruling Malicoat's objections and admitting this testimony.

FN35. 12 O.S.1991, § 2702.

FN36. Gabus v. Harvey, 1984 OK 4, 678 P.2d 253, 255.

¶ 22 Malicoat also complains of evidence of injuries not contemporaneous with death, including the bites, shoving, pushing and poking. Evidence of biting was relevant because biting was charged in the Information. Evidence Malicoat caused Tessa's head injury by pushing her into the bed rail was relevant because the head injury contributed to her death. Much of the other “evidence” Malicoat complains of was actually contained in the State's closing argument. The trial court did not admit evidence that the abuse continued for nineteen days, although the jury certainly could have inferred that from evidence that was admitted. There was evidence that Malicoat poked Tessa both in anger and at play, and pushed her rather than spanking her, but there was no date given for these incidents. We have held evidence of extreme mental torture occurring before or separate from the events causing death is insufficient to support the heinous, atrocious or cruel aggravating circumstance.FN37 However, Malicoat subjected Tessa to a continuing course of conduct, comprising intentional child abuse, which even he agreed could be described as torture. The trial court did not err in admitting this evidence.

FN37. Cheney, 909 P.2d at 81-82. But see Hawkins v. State, 1994 OK CR 83, 891 P.2d 586, 597, cert. denied, 516 U.S. 977, 116 S.Ct. 480, 133 L.Ed.2d 408 (1995) (mental torture during kidnapping preceding murder sufficient to support aggravating circumstance).

¶ 23 The medical examiner testified regarding the extent of pain and suffering Tessa probably experienced as a result of her injuries. Other evidence showed Malicoat engaged in serious physical abuse and torture preceding Tessa's death. Malicoat told officers Tessa was conscious and screamed in pain as he hit her in the stomach, causing non-survivable injuries. Sufficient evidence supports the jury's finding of the heinous, atrocious or cruel aggravating circumstance and this proposition is denied.

¶ 24 Malicoat claims in Proposition XV that the State's reliance upon the same course of conduct to support both his conviction for child abuse murder and the especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel aggravating circumstance does not effectively narrow the class of murders for which the death penalty is appropriate. The State relied on evidence that Malicoat abused Tessa and beat her to death to gain a conviction for child abuse murder. The State introduced the same evidence to support the charge that the murder was especially heinous, atrocious or cruel (see Proposition XIV). Malicoat argues this use of the same evidence to prove guilt and an aggravating circumstance eviscerates the narrowing function necessary before the death penalty may be imposed. In capital cases, the sentencer's discretion must be narrowed by circumscribing the class of death-eligible persons.FN38 Malicoat argues that the child abuse murder statute broadens the class of death-eligible homicides by requiring proof of abusive conduct toward a child resulting in death. He claims the proof of torture or serious physical abuse necessary for a murder to be heinous, atrocious or cruel merely duplicates the child abuse requirement of child abuse murder. He suggests that this double use of torture or serious physical abuse is being improperly used to both broaden and narrow the class of death-eligible defendants.

FN38. Zant v. Stephens, 462 U.S. 862, 878-79, 103 S.Ct. 2733, 2743-44, 77 L.Ed.2d 235 (1983).

¶ 25 We disagree. Malicoat is incorrect when he claims a conviction for child abuse murder necessarily requires proof of physical abuse or torture. The statute requires only the death of a child resulting from one of several forms of abuse. A defendant may be convicted of child abuse murder although the victim did not consciously suffer before death. As conscious suffering is necessary for a valid finding that a murder is heinous, atrocious or cruel, that aggravating circumstance does not merely duplicate the elements of child abuse murder.FN39 Rather, the heinous, atrocious or cruel*400 aggravating circumstance narrows the class of child abuse murders in which defendants are eligible for the death penalty. This proposition is denied.

* * *

Malicoat begins Proposition VII by alleging several errors during the first stage of trial. The State attempted to introduce evidence that Malicoat's house was filthy, smelled bad, and had dog feces on the floor and furniture. The trial court initially sustained Malicoat's objections to this evidence, noting this was not a neglect case and evidence of poor housekeeping had no causal connection to Tessa's death. On cross-examination defense counsel asked a police officer *404 whether Malicoat hadn't emphasized his sense of responsibility for taking care of Tessa. The trial court ruled the question of responsibility for the child's care opened the door to the house's condition, and overruled Malicoat's objection to a subsequent question about the state of the house. This was not clearly an abuse of discretion. While the evidence of poor housekeeping was not relevant to the charged offense it was relevant to the suggestion Malicoat accepted his parental responsibilities.

¶ 41 Malicoat complains about evidence that he had a bad temper, along with a picture of a hole he punched in the wall of his bedroom. The evidence shows Malicoat told officers he had a bad temper but tried to keep it under control around Tessa, and knew it was getting the better of him in the week before her death. Malicoat's mother testified that, during a visit shortly before Tessa's death, Tessa clung to her and did not want to go to Malicoat. She also saw Tessa back away when Malicoat tried to feed her. Malicoat's mother said these actions caused her to believe Tessa was afraid of Malicoat. This evidence was within the witness's personal knowledge, FN62 and rationally based on her perceptions of the events she saw. FN63 However, all this evidence could only be relevant to show whether Malicoat intended to commit child abuse. As child abuse is a general intent crime, this was irrelevant for this issue and should have been excluded. FN64 However, we find admission of this evidence did not contribute to Malicoat's conviction or sentence.

Malicoat argues that counsel failed to investigate his medical history and effectively prepare his medical expert. Appellate counsel asserts trial counsel should have discovered Malicoat's history of seizures. Counsel claims that this information would have changed the medical expert's diagnosis and potential first stage testimony. He argues this information could have been used in support of an instruction on second degree depraved mind murder. We have determined Malicoat was not entitled to an instruction on second degree murder. In addition, general information that Malicoat had suffered from seizures would not have entitled him to that instruction without some evidence that he suffered from a seizure while committing the acts of child abuse which resulted in Tessa's death. As Malicoat was not entitled to an instruction on second degree murder, he cannot show he was prejudiced by counsel's failure to use this information in first stage. Similarly, we find no prejudice in the absence of this information during second stage. We cannot agree with Malicoat's claim that counsel failed to present significant mitigating evidence. On the contrary, counsel presented a thorough and comprehensive picture of Malicoat's personal and family history, concentrating on his experience of severe abuse and resulting personality transformation. Appellate counsel has not shown the addition of evidence Malicoat suffered from seizures would have led the jury to conclude the balance of aggravating circumstances and mitigating factors did not support death.

* * *

In accordance with 21 O.S.1991, § 701.13(C), we must determine (1) whether the sentence of death was imposed under the influence of passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor, and (2) whether the evidence supports the jury's finding of aggravating circumstances. Upon review of *407 the record, we cannot say the sentence of death was imposed because the jury was influenced by passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor contrary to 21 O.S.1991, § 701.13(C).

¶ 55 The jury was instructed on and found the existence of two aggravating circumstances: (1) that the murder was especially heinous, atrocious or cruel, and (2) the existence of a probability that Malicoat would commit criminal acts of violence constituting a continuing threat to society. Malicoat presented evidence that he did not intend the victim's death, and that he suffered severe and extended emotional and physical abuse as a child. The jury was instructed on nine mitigating factors (see Proposition XIX). Upon our review of the record, we find the sentence of death to be factually substantiated and appropriate.

¶ 56 Finding no error warranting modification, the judgment and sentence of the District Court of Grady County is AFFIRMED.

Malicoat v. State 137 P.3d 1234 (Okla.Crim.App. 2006) (PCR).

Background: Following affirmance of defendant's conviction for first degree murder and his death sentence, 992 P.2d 383, and following denial of defendant's state application for postconviction relief and his federal petition for writ of habeas corpus, 426 F.3d 1241, State filed an application for execution date, and defendant requested a stay of the execution.

Holding: As a matter of first impression, the Court of Criminal Appeals held that Oklahoma's execution protocol, setting forth lethal injection procedures, does not violate the Eighth Amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

Request for stay denied; execution date set.

Lumpkin, V.P.J., concurred in part and dissented in part with an opinion.

James Patrick Malicoat was tried by jury and convicted of First Degree Murder in violation of 21 O.S.1991, § 701.7(C), in the District Court of Grady County, Case No. CF-97-59. The jury found two aggravating circumstances: (1) that the murder was especially heinous, atrocious or cruel, and (2) the existence of a probability that Malicoat would commit criminal acts of violence constituting a continuing threat to society. In accordance with the jury's recommendation the Honorable Joe Enos sentenced Malicoat to death. He appealed his judgments and sentences to this Court, we affirmed, and the United States Supreme Court denied certiorari.FN1 This Court subsequently denied Malicoat's application for post-conviction relief. FN2 Malicoat was denied habeas corpus relief in the federal courts. FN3 Malicoat has exhausted his appeals in state and federal court. On June 5, 2006, the State of Oklahoma filed an Application for Execution Date with this Court.

FN1. Malicoat v. State, 2000 OK CR 1, 992 P.2d 383, cert. denied, 531 U.S. 888, 121 S.Ct. 208, 148 L.Ed.2d 146 (2000).

FN2. Malicoat v. State, No. PC-1999-1289 (Okl.Cr. Feb. 1, 2000). Malicoat did not file a petition for writ of certiorari challenging this opinion in the United States Supreme Court.

FN3. Malicoat v. Mullin, 426 F.3d 1241 (10th Cir.2005). Certiorari review was denied. Malicoat v. Sirmons, No. 05-10143, ---U.S. ----, 126 S.Ct. 2356 (June 5, 2006).

¶ 2 Malicoat filed an Objection to Setting of an Execution Date on June 5, 2006.FN4 Malicoat claims that Oklahoma's lethal injection protocol violates the Eighth Amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. He argues that the state's execution procedure creates a substantial risk that he will consciously suffer or experience excruciating pain during the execution process. Malicoat claims that mistakes made during the execution process itself might lead to drug administration failure, causing pain and suffering. He claims that Oklahoma's failure to require specially trained medical personnel heightens the likelihood that such mistakes will be committed. Malicoat also claims that the drugs used in the execution protocol themselves cause pain and suffering and violate the Eighth Amendment. Malicoat notes that pending litigation in the federal courts challenges Oklahoma's execution protocol, and asks this Court to stay any execution date until that litigation has been resolved.

* * *

In support of his claim, Malicoat offers this Court affidavits from the Warden of the Oklahoma State Penitentiary, and an Assistant Professor of Clinical Anesthesiology in the Department of Anesthesiolgy at Columbia University, New York. He also provides the Court with the Oklahoma Department of Corrections Procedures for Execution, a portion of a 2000 Report on the American Veterinary Medical Association Panel on Euthanasia*1236 and a newspaper article describing the recent execution of another Oklahoma capital prisoner. We have considered these documents in reaching our conclusion.

¶ 5 Oklahoma's execution protocol, requiring lethal injection, is established by statute: “The punishment of death must be inflicted by continuous, intravenous administration of a lethal quantity of an ultrashort-acting barbiturate in combination with a chemical paralytic agent until death is pronounced by a licensed physician according to accepted standards of medical practice.” FN8 The specific method of execution is determined by Department of Corrections. The Department of Corrections developed the method of execution currently in use after consultation with medical professionals in the Oklahoma Medical Examiner's Office and the Department of Corrections Pharmacy, and after reviewing procedures used in other states.FN9 The process is described in Exhibit A to Malicoat's Objection, an Affidavit by Warden Mullin. Since 2003, the Department of Corrections has administered sodium thiopental, vecuronium bromide, and potassium chloride in the execution process.FN10 All personnel involved in the execution process have had extensive training and experience in the execution procedures.FN11 Throughout the execution, a licensed physician is present in the execution chamber to monitor the defendant.FN12 A licensed phlebotomist inserts an intravenous line into each arm of the defendant.FN13 Using both lines, the defendant is first given an ultra-short acting barbiturate, sodium thiopental, which renders the inmate unconscious. This is followed by vecuronium bromide and potassium chloride, administered as quickly as possible after the barbiturate, alternating in each arm.FN14 During the process, another dose of sodium thiopental is administered.FN15 Immediately after each drug is administered, that line is flushed with saline before the next dosage is given.FN16 The drugs for each execution are compounded by a licensed pharmacist for the Department of Corrections.FN17 The purpose behind the regimen of drug administration is to ensure that the barbiturate, sodium thiopental, renders the defendant unconscious as the other drugs are administered.

FN8. 22 O.S.2001, § 1014; Oklahoma Department of Corrections Procedures for the Execution of Inmates Sentenced to Death VII(B), OP-040301, Effective Date 4/8/05 (Exhibit C).

FN9. Affidavit of Warden Mike Mullin, ¶ 5 (Exhibit A).

FN10. Affidavit of Warden Mike Mullin, ¶ 8 (Exhibit A).

FN11. Affidavit of Warden Mike Mullin, ¶ 19 (Exhibit A).

FN12. Affidavit of Warden Mike Mullin, ¶ 11 (Exhibit A). Malicoat claims that under the Oklahoma process nobody assures that the defendant is unconscious before the vecuronium bromide and potassium chloride are administered. [Appellant's Response at 2] This assertion is unsupported by any materials before this Court, and appears to be contradicted by the presence of the monitoring physician.

FN13. Affidavit of Warden Mike Mullin, ¶¶ 6, 12 (Exhibit A).

FN14. Affidavit of Warden Mike Mullin, ¶ 13, 15 (Exhibit A).

FN15. Affidavit of Warden Mike Mullin, ¶ 13, 15 (Exhibit A). A total of 2400 milligrams, or 2.4 grams, of sodium thiopental is administered throughout the procedure. Malicoat mistakenly claims in his reply brief that only 1200 milligrams are used.

FN16. Affidavit of Warden Mike Mullin, ¶ 20 (Exhibit A).

FN17. Affidavit of Warden Mike Mullin, ¶ 17 (Exhibit A).

¶ 6 Malicoat fails to show that this protocol is facially unconstitutional. The Eighth Amendment prohibits cruel and unusual punishment.FN18 Whether a punishment is considered cruel and unusual is viewed through “the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society.”FN19 We look at whether the punishment at issue is proportionate to the offense, offends contemporary standards of decency, and has legitimate punishment objectives.FN20 *1237 Punishment is cruel and unusual when it involves the unnecessary and wanton infliction of pain. FN21 Malicoat provides this Court with an affidavit from an anesthesiologist who has studied the execution process, explaining the way in which the drugs interact. Dr. Heath relied on Warden Mullin's Affidavit describing Oklahoma's procedure in preparing his own analysis. The vecuronium bromide, administered immediately after the barbiturate, paralyzes the muscles. The potassium chloride spreads throughout the body and stops the heart. If the defendant is not unconscious when the last two drugs are administered, he will experience extreme burning pain but be unable to indicate this because his muscles will be paralyzed.FN22 Dr. Heath avers that the barbiturate used by Oklahoma, when properly administered, will work effectively, rendering a defendant unconscious “for a considerable period of time.”FN23 Neither his affidavit nor any other material presented by Malicoat suggest that the protocol, as set forth in the Department of Corrections Procedures and Warden Mullin's Affidavit, is anything but humane and effective. Oklahoma and at least thirty-three other capital punishment states have mandated lethal injection as the primary means of execution, suggesting that it comports with contemporary standards of decency.FN24 We have in the past held that lethal injection per se is not unconstitutional. FN25 We must conclude that Oklahoma's execution protocol is constitutional on its face.

FN18. U.S. Const. amend. VIII.

FN19. Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551, 561, 125 S.Ct. 1183, 1190, 161 L.Ed.2d 1 (2005).

FN20. Roper, 543 U.S. at 561, 125 S.Ct. at 1190; Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304, 122 S.Ct. 2242, 153 L.Ed.2d 335 (2002); Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153, 173, 96 S.Ct. 2909, 2925, 49 L.Ed.2d 859 (1976).

FN21. Gregg, 428 U.S. at 173, 96 S.Ct. at 2925.

FN22. Affidavit of Dr. Mark Heath, ¶ 5 (Exhibit D).

FN23. Affidavit of Dr. Mark Heath, ¶ 6 (Exhibit D). He also states, “The successful administration of a large dose of pentothal causes the rapid onset of deep unconsciousness.” Affidavit, ¶ 12. Dr. Heath does not state the amount of sodium thiopental he considers sufficient to cause rapid unconsciousness in the affidavit before the Court. Dr. Heath testified before a Tennessee court that two grams would cause unconsciousness, and five grams would almost certainly be fatal. Abdur'Rahman v. Bredesen, 181 S.W.3d 292, 303 (Tenn.2005). In a similar affidavit admitted in a case before the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, Dr. Heath declared that five grams of sodium thiopental is a massive, potentially lethal dose. Ex Parte Aguilar, 2006 WL 1412666, *3 (Tex.Crim.App. May 22, 2006) (Cochran, J., concurring) (not for publication). Aguilar was presented as a habeas petition. Reviewing under the Texas standard for habeas corpus petitions, the full Texas Court concluded without discussion that Aguilar had failed to make a prima facie showing that the lethal injection process was unconstitutional. The Texas Department of Criminal Justice considers three grams of sodium thiopental to be a lethal dosage. Ex parte O'Brien, 190 S.W.3d 677, 2006 WL 1358983 (Tex.Crim.App.2006) (per curiam opinion dismissing habeas corpus claim) (Cochran, J., concurring).

FN24. The Tennessee and Connecticut Supreme Courts have noted that lethal injection is thought to be the most humane form of execution. Abdur'Rahman, 181 S.W.3d at 306; State v. Webb, 252 Conn. 128, 750 A.2d 448, 457 (2000).

FN25. Jones, 2006 OK CR 5, 128 P.3d at 551; Romano, 1996 OK CR 20, 917 P.2d at 18.

¶ 7 Malicoat argues that the protocol is unconstitutional because mistakes may be made in its application, and if mistakes are made during his execution, he will suffer a cruel and unusual death contrary to the Eighth Amendment. Dr. Heath's Affidavit lists fourteen potential areas in which mistakes may be made in the preparation or administration of the drugs. FN26 Many of these involve human error, including failure to properly mix the drugs, mislabeling, errors in insertion of equipment, and errors in administering the drugs. Some involve mechanical or equipment failure. Some potential mistakes on the list involve equipment which may or may not be used in Oklahoma executions. As Judge Cochran of the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals has said, regarding a similar affidavit Dr. Heath prepared in a case for that Court,

FN26. Affidavit of Dr. Mark Heath, ¶ 8, (a-n) (Exhibit D).

All of these are potential problems during the lethal injection protocol, just as they are potential problems during any surgical procedure. As a society, however, we do not ban surgery because of these potential problems. We take appropriate precautions and rely upon adequate training, skill, and care in doing the job.FN27

FN27. Ex Parte Aguilar, 2006 WL 1412666, *3 (Tex.Crim.App. May 22, 2006) (Cochran, J., concurring) (not for publication) (not for publication).

The State of Oklahoma has developed a particular execution protocol, requiring trained personnel including a licensed physician and licensed medical personnel. The Department of Corrections provides training in the execution process for all persons involved in carrying out the procedures. We agree with the Supreme Court of Connecticut that an execution process “cannot foreclose the possibility of human error, that always accompanies any human endeavor, ” and that the “risk of accident cannot and need not be eliminated from the execution process in order to survive constitutional review.” FN28

FN28. State v. Webb, 252 Conn. 128, 750 A.2d 448, 456-57 (2000), quoting Campbell v. Wood, 18 F.3d 662, 681 (9th Cir.1994) (ruling Washington state's method of execution, hanging, was constitutional).

¶ 8 Malicoat claims that Oklahoma compounds the possibility of mistakes by allowing insufficiently licensed or trained persons to carry out executions. He argues that these mistakes could be avoided if Oklahoma required executions to be carried out by persons with special medical training. Dr. Heath suggests that appropriately trained persons include nurses, emergency medical technicians, physicians, dentists, veterinarians, and physician's assistants. FN29 Oklahoma requires a licensed physician to be present at each execution and a licensed phlebotomist inserts the IV tubes. Malicoat claims that a licensed phlebotomist is not qualified to administer and manage intravenous fluids and drugs. Without expressing an opinion on this claim we note that the protocol provides that a physician is present, monitoring the execution, and thus each step of the process (including insertion of IV tubes and administration of the fluids) must be performed to the physician's satisfaction. Dr. Heath avers that the risk of mistake is compounded because the Oklahoma Department of Corrections has not published the qualification requirements or training procedures for personnel, including medical personnel, involved in executions.FN30 Malicoat thus asks this Court to join Dr. Heath in speculating that, because these training procedures are not part of a public record or submitted to the Court in this case, the execution personnel must be inadequately trained or incompetent. We decline to so speculate.

FN29. Affidavit of Dr. Mark Heath, ¶ 9 (Exhibit D).

FN30. Affidavit of Dr. Mark Heath, ¶¶ 10, 11 (Exhibit D).

¶ 9 Malicoat provides anectodal evidence, in the form of a newspaper article and Dr. Heath's Affidavit, that defendants may not have been unconscious in previous recent executions. Dr. Heath describes several eyewitness accounts of executions in which the defendant's body continued to move or convulse after sodium thiopental was injected. In his opinion, these accounts are “inconsistent with the successful administration of a large dose of pentothal.” FN31 There is no way for this Court to determine, years after those executions, whether eyewitness reports of movement were accurate or signified anything with regard to those defendants' conscious or unconscious state. This Court similarly cannot determine whether mistakes may be made in future executions. Once again, this Court will not speculate on whether mistakes may have been made in past executions. The question before us is whether Oklahoma's execution protocol is constitutional, and we have found that it is.

FN31. Affidavit of Dr. Mark Heath, ¶¶ 12 (Exhibit D). Dr. Heath also suggests that post-execution autopsy reports of sodium pentothal blood concentration levels in North Carolina defendants, some of which were low, may be helpful in determining whether sodium thiopental is appropriately administered. Dr. Heath's brief description of these report results, and their complete inapplicability to Oklahoma procedure, make them less than helpful to this Court.

¶ 10 This Court does not intend to denigrate Malicoat's anecdotal examples of potential problems with executions in Oklahoma. We have previously noted that some eyewitness accounts of irregularities in past executions may create cause for concern.FN32 We again express our confidence that the Department of Corrections will continue to monitor and revise the execution protocol as may be necessary to ensure a swift, painless and humane execution. However, these expressions of concern and confidence regarding the process do not undermine our legal *1239 conclusion that Oklahoma's execution protocol does not violate the Eighth Amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

FN32. Murphy, 124 P.3d at 1209, n. 23.

¶ 11 Although this is an issue of first impression in Oklahoma, other jurisdictions have considered and rejected similar claims.FN33 After a lengthy analysis the Tennessee Supreme Court concluded, “we cannot judge the lethal injection protocol based solely on speculation as to problems or mistakes that might occur. We must instead examine the lethal injection protocol as it exists today.” FN34 We agree. Doing so, we have found that Oklahoma's execution protocol is not cruel and unusual. We recognize that this issue is being litigated separately in the federal court system. However, Malicoat is not entitled to a stay of execution while that litigation is pending.FN35 Malicoat's execution date is set for Tuesday, August 22, 2006.

FN33. Ex Parte Aguilar, 2006 WL 1412666, *3 (Tex.Crim.App. May 22, 2006); Ex parte O'Brien, 190 S.W.3d 677, (Tex.Crim.App.2006); Bieghler v. State, 839 N.E.2d 691, 696 (Ind.2005); Sims v. State, 754 So.2d 657, 668 (Fla.2000); State v. Webb, 750 A.2d at 455 (Conn.2000). See also State v. Deputy, 644 A.2d 411, 420-21 (Del.Super.1994) (discussing training of personnel and contemporary standards of decency). Federal jurisdictions which have rejected this issue include Reid v. Johnson, 333 F.Supp.2d 543, 551 (E.D.Va.2004). In Boltz v. Jones, No. 2006 WL 1495030 (10th Cir. June 1, 2006), the Tenth Circuit recently lifted a stay of execution granted in a capital case with a pending federal claim. The Tenth Circuit found that Boltz had not shown a likelihood of success on the merits of his pending claim that Oklahoma's lethal injection execution protocol was cruel and unusual.

FN34. Abdur'Rahman, 181 S.W.3d at 308.

FN35. The United States Supreme Court recently held that state capital prisoners may bring civil federal suits, claiming that lethal injection procedures are cruel and unusual for reasons similar to Malicoat's, under 42 U.S.C. § 1983. Hill v. McDonough, ---U.S. ----, 126 S.Ct. 2096, 2006 WL 1584710 (U.S. June 12, 2006). The Court expressed no opinion on the merits of the issue. However, the Court noted that a defendant filing a § 1983 suit raising this claim is not entitled to a stay of execution as a matter of course. Op. at ----.

IT IS SO ORDERED. WITNESS OUR HANDS AND THE SEAL OF THIS COURT this 19th day of June, 2006.

Malicoat v. Mullin 426 F.3d 1241 (10th Cir. 2005) (Habeas).

Background: Following affirmance on appeal of defendant's conviction for felony murder by child abuse and imposition of the death penalty, 992 P.2d 383, defendant filed petition for writ of habeas corpus. The United States District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma, Vicki Miles-LaGrange, J., denied petition, and defendant appealed.

Holdings: The Court of Appeals, Henry, Circuit Judge, held that:

HENRY, Circuit Judge.

In this appeal, Mr. Malicoat argues that: (1) his counsel on direct appeal was ineffective for failing to argue that a carving in the courtroom bearing the inscription “AN EYE FOR AN EYE AND A TOOTH FOR A TOOTH” deprived him of a fair trial. Mr. Malicoat also argues that the OCCA erred by (2) concluding that, under Beck v. Alabama, 447 U.S. 625, 627, 100 S.Ct. 2382, 65 L.Ed.2d 392 (1980), he was not entitled to an instruction on the lesser-included offense of second-degree depraved-mind murder; (3) concluding that no finding of Mr. Malicoat's intent to kill was required to support the death sentence, in violation of the Eighth Amendment principles set forth in Enmund v. Florida, 458 U.S. 782, 102 S.Ct. 3368, 73 L.Ed.2d 1140 (1982) and Tison v. Arizona, 481 U.S. 137, 107 S.Ct. 1676, 95 L.Ed.2d 127 (1987); (4) rejecting Mr. Malicoat's claim that the prosecution's closing arguments during the guilt and sentencing stages deprived him of a fair trial; (5) concluding that the admission of a photograph of the victim while alive, although error, was harmless; (6) rejecting Mr. Malicoat's claim that he received ineffective assistance of counsel at trial. Finally, Mr. Malicoat argues that (7) the cumulative effect of these errors also deprived him of a fair trial.

We are not convinced by these arguments. First, the display of the “EYE FOR AN EYE” inscription on the carving in the courtroom did not constitute structural error. Thus, Mr. Malicoat's Sixth Amendment right to effective assistance of counsel was not violated by his attorney's failure to challenge it on direct appeal. Second, as to Mr. Malicoat's Enmund/Tison argument, we conclude that the OCCA did not unreasonably apply federal law in holding that, in order to impose the death penalty, the prosecution was not required to prove that Mr. Malicoat intended the death of the victim or acted in reckless disregard of human life. As to Mr. Malicoat's Beck claim, we similarly conclude that the OCCA did not unreasonably apply federal law in holding that Mr. Malicoat was not entitled to an instruction on second-degree depraved-mind murder. Mr. Malicoat's claims of prosecutorial misconduct, admission of prejudicial evidence, ineffective assistance of trial counsel, and cumulative error also lack merit. Accordingly, we conclude that the district court properly denied Mr. Malicoat's 28 U.S.C. § 2254 petition.

I. BACKGROUND

The relevant facts are set forth in the OCCA's opinion on direct appeal. See 992 P.2d at 391-92. As a result, we only briefly summarize them here.

At about 8:25 p.m. on February 21, 1997, Mr. Malicoat and his girlfriend, Mary Ann Leadford, brought their thirteen-month-old daughter, Tessa Leadford, to the county hospital emergency room. The hospital staff determined that Tessa had been dead for several hours. Her face and body were covered with bruises. She had a large mushy closed wound on her forehead and three human bite marks on her body. A post-mortem examination revealed two subdural hematomas from the head injury, and severe internal injuries, including broken ribs, internal bruising and bleeding, and a torn mesentery. The medical examiner concluded the death was caused by a combination of the head injury and internal bleeding from the abdominal injuries.

Tessa and Mary Ann Leadford had begun living with Mr. Malicoat on February 2, 1997. Mr. Malicoat worked a night shift on an oil rig and was responsible for Tessa's care during the day.

Mr. Malicoat admitted that he routinely poked Tessa hard in the chest area and occasionally bit her, both as a disciplinary measure and in play. When interviewed by police officers, Mr. Malicoat initially denied knowing how Tessa had received the severe head injury. Subsequently, he suggested that she had fallen and hit the edge of a waterbed frame. However, he eventually admitted that he had hit her head on the bed frame one or two days before she died. He also admitted that, at about 12:30 p.m. on February 21, while Ms. Leadford was at work, he twice punched Tessa hard in the stomach. He stated that Tessa stopped breathing and that he gave her CPR. According to Mr. Malicoat, when Tessa began breathing again, he gave her a bottle containing a soft drink and went to sleep next to her on the bed. When he awoke around 5:30 p.m., she was dead. He put Tessa in her crib and covered her with a blanket, spoke briefly with Ms. Leadford, and went back to sleep in the living room. Ms. Leadford eventually discovered that Tessa was not moving, and the couple took her to the emergency room.

Seeking to explain the events leading to Tessa's death, Mr. Malicoat reported that he had worked all night, had car trouble, took Ms. Leadford to work, and was exhausted. He added that he had hit Tessa when she would not lie down so he could sleep. He said he sometimes intended to hurt Tessa when he disciplined her, but never meant to kill her. He told the officers that he had suffered through extreme abuse as a child that he did not realize his actions would seriously hurt or kill Tessa.

The state charged Mr. Malicoat with first-degree felony murder by child abuse under Okla. Stat. tit. 21, § 701.7(C). A first trial ended with a mistrial during jury selection. After the second trial, the jury convicted Mr. Malicoat of the murder charge. Then, upon hearing additional evidence at sentencing, the jury found two aggravating factors: (1) that the murder was especially heinous, atrocious, and cruel and (2) that there existed a probability that Mr. Malicoat would commit criminal acts of violence that constituted a continuing threat to society. See Okla Stat. tit. 21, § 701.12(4) and (7). Following the jury's recommendation, the trial court imposed the death penalty.

The OCCA affirmed Mr. Malicoat's conviction and sentence on direct appeal and then rejected his petition for post-conviction relief. Subsequently, the federal district court denied Mr. Malicoat's federal habeas petition.

* * *

Ineffective Assistance of Appellate Counsel (in failing to challenge the “EYE FOR AN EYE” inscription)

Mr. Malicoat first argues that he received ineffective assistance of counsel on direct appeal. His claim is based upon a wooden carving on the wall directly behind the judge's bench in the Grady County, Oklahoma courtroom in which he was tried. The carving depicts a man and a woman holding a sword bearing the inscription “AN EYE FOR AN EYE AND A TOOTH FOR A TOOTH.” FN1

FN1. Mr. Malicoat attached two photographs of the carving to his state court application for post-conviction relief, and they are attached as an exhibit to this opinion.

A 1976 article from the Chickasha Daily Express reports that the carving was made by Derald Swineford in 1934. The article states that the carving is entitled “Justice Tempered by Mercy.” Fed. Ct. Rec. doc. 23, Ex. A (Response to Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus, filed Dec. 4, 2001).

According to the Daily Express, “the sword with the harsh inscription ‘An Eye for an Eye and a Tooth for a Tooth’ carving on the blade and the winged lions at the bottom represents the early Babylonian code.” Id. “The male figure ··· represents the [Grecian] practice which was the same as that of Hammurabi, as he is grasping the sword of justice.” Id.

The female figure represents Mercy. “[She] represents the Roman element since it seems the Romans were the first to really try a case and decide it not on the belief that the party guilty of the misdeed should suffer in the same manner as the recipient but that a group of men should weigh the causes of the misdeed and decide in what manner the guilty party should be punished or whether he was deserving of any punishment.” Id.

There is no indication in the record that the title appears anywhere on the carving, and the parties do not so suggest.

Mr. Malicoat objected to the inscription during jury selection in his first trial, and the judge responded by covering it up. However, a different judge presided over the second trial, and he overruled Mr. Malicoat's objection. On direct appeal, Mr. Malicoat's counsel did not argue that the inscription deprived him of a fair trial.

Mr. Malicoat now maintains that the failure to advance this argument was constitutionally deficient. In particular, he argues that the trial judge's failure to cover the inscription constituted “a structural error,” the kind of error that “necessarily render[ed][his] trial fundamentally unfair,” Rose v. Clark, 478 U.S. 570, 577, 106 S.Ct. 3101, 92 L.Ed.2d 460 (1986) and that “def [ies] analysis by ‘harmless-error’ standards,” Arizona v. Fulminante, 499 U.S. 279, 309, 111 S.Ct. 1246, 113 L.Ed.2d 302 (1991). As a result, he asserts, there is a reasonable probability that, if his appellate counsel had challenged the “EYE FOR AN EYE” inscription, Mr. Malicoat's capital sentence would have been overturned.

In assessing this argument, we begin by examining the OCCA's adjudication of this claim in order to determine the appropriate standard of review. Then, we outline the framework for evaluating claims alleging ineffective assistance of appellate counsel. Finally, we turn to the particular error alleged here, the failure to challenge the “EYE FOR AN EYE” inscription as an improper invocation of religious principle in a capital case, and we consider whether the inscription constituted a structural error, which, if argued by counsel, would have led the OCCA to overturn Mr. Malicoat's sentence.

A. The OCCA's decision

Mr. Malicoat first raised this claim in post-conviction proceedings in the OCCA. There, he argued that the inscription constituted a structural error because it “creat[ed] an establishment of religion at his public trial; and it denied him a reliable sentencing free from arbitrary, capricious, and unreliable state action, in violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments.” Original Application for Post-Conviction Relief in a Death Penalty Case, at 34 (filed Nov. 19, 1999). Mr. Malicoat submitted photographs of the carving and the inscription, but he offered no evidence that the jury could see the inscription given its vantage point. He *1248 argued that his counsel's failure to challenge the inscription on direct appeal constituted ineffective assistance of counsel in violation of the Sixth Amendment.

In rejecting this argument, the OCCA applied the three-part test for ineffective assistance of counsel claims set forth in its prior decisions. See Order Denying Application for Post-Conviction Relief and Application for Exercise of Original Jurisdiction, filed Feb. 1, 2000, at 3 (citing Walker v. State, 933 P.2d 327, 333 (Okla.Crim.App.1997)).FN2 Under that standard, “omission of meritorious claims [from an appellate brief] will ‘rarely, if ever,’ constitute deficient performance.” Id. at 3 (quoting Bryan v. State, 948 P.2d 1230, 1233 (Okla.Crim.App.1997)).

FN2. Notably, Judge Chapel vigorously dissented. He concluded that:

the sign over the Grady Courthouse bench, reading “AN EYE FOR AN EYE & A TOOTH FOR A TOOTH,” [is] inappropriate in any criminal trial. As I have previously said, in the context of a capital trial I believe that sign is outrageous and unconstitutional. This violates Art. I, § 2 of the Oklahoma Constitution and the 1st, 5th, and 14th Amendments of the United States Constitution.