39th murderer executed in U.S. in 2001

722nd murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

2nd murderer executed in Indiana in 2001

9th murderer executed in Indiana since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

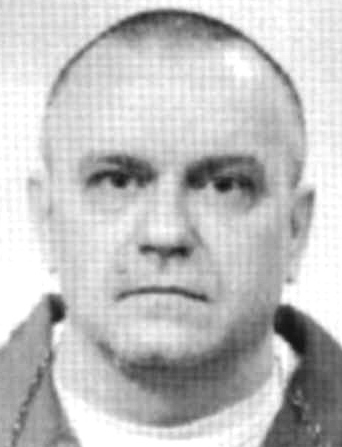

James Lowery W / M / 32 - 54 |

Mark Thompson W / M / 80 Gertrude Thompson W / F / 80 |

01-07-83 |

Summary:

Mark and Gertrude Thompson were 80 years of age, in declining health, and needed assistance in caring for themselves and their property. Both were found shot to death in their country home in West Point, Indiana. The Thompsons had earlier employed Lowery and his wife as caretakers. The Thompsons, dissatisfied with the Lowerys, asked them to leave. Lowery and his friend Jim Bennett discussed committing robbery and Lowery told Bennett he knew where he could get some money. On September 30, 1979 Bennett picked Lowery up and followed Lowery's directions. Lowery told Bennett they were going to the Thompson's residence to force him to write a check for $9,000, then to kill and bury both Thompsons. Janet Brown, housekeeper and caretaker for the Thompsons, was sitting in her trailer adjacent to the Thompson's garage when Lowery, armed with a pistol and sawed-off shotgun, kicked the door open and entered. After some conversation, Lowery forced her to take him into the Thompson's residence. Lowery took Brown into the kitchen where Mark Thompson was standing. He told Thompson he was being held up and then shot him in the stomach. Lowery then went to another room, forced Mrs. Thompson into the kitchen and shot her in the head. He also shot Brown, but Brown had her hand over her head when Lowery fired at her, causing injury to her hand and her head, but not fatally wounding her. A burglar alarm began ringing and Lowery became excited. He went back to and shot Mr. Thompson in the head before fleeing the scene. Lowery admitted the killings during penalty phase testimony. Bennett pled guilty by agreement, received a 40 year sentence, and testified against Lowery at his first trial. Following reversal on direct appeal for failure to sequester the jury, a second trial ended with the same result. At the second trial, Bennett refused to testify and his previous testimony was admitted against Lowery, who was sentenced to death a second time on January 7, 1983.

Citations:

James Lowery v. State, 434 N.E.2d 868 (Ind. May 5, 1982) (Direct Appeal).

Lowery v. State, 471 N.E.2d 258 (Ind. 1984) (Attorney fees).

James Lowery v. State, 478 N.E.2d 1214 (Ind. 1985) (Direct Appeal).

Lowery v. Indiana, 106 S. Ct. 1500 (1986) (Cert. denied).

Lowery v. State, 640 N.E.2d 1031 (Ind. 1994) (PCR).

Lowery v. Anderson, 69 F.Supp.2d 1078 (S.D. Ind. July 6, 1999) (Habeas).

Lowery v. Anderson, 225 F.3d 833 (7th Cir. August 29, 2000) (Habeas).

Lowery v. Anderson, 121 S.Ct. 1488 (April 2, 2001) (Cert. Denied).

Lowery v. Anderson, ___ F.Supp.2d ___, (S.D. Ind. April 13, 2001) (Clemency).

Internet Sources:

Clark County Prosecuting Attorney (James Lowery)

EXECUTED BY LETHAL INJECTION 06-27-01 12:29 A.M.DOB: 03-16-1947

DOC#: 18667 White Male

Boone County Superior Court

Judge Paul H. Johnson, Jr.

Venued from Tippecanoe County

Prosecutor: John H. Meyers, John Barce

Defense: Lawrence D. Giddings, Donald R. Peyton

Date of Murder: September 30, 1979

Victim(s): Mark Thompson W/M/80; Gertrude Thompson W/F/80 (Former employers)

Method of Murder: shooting with .32 handgun

Conviction: Murder, Murder, Attempted Murder (A Felony)

Sentencing: July 11, 1980 (Death Sentence)

Aggravating Circumstances: b (1) Burglary/Robbery; B(8) 2 murders

Mitigating Circumstances: no parental love, mental commitment as a teenager

Direct Appeal:

James Lowery v. State, 434 N.E.2d 868 (Ind. May 5, 1982)

Conviction Reversed 3-2 DP Vacated 3-2 (Failure to sequester)

Debruler Opinion; Hunter, Prentice concur; Givan, Pivarnik dissent.

Lowery v. State, 471 N.E.2d 258 (Ind. 1984) (Regarding attorney fees for public defenders at DP trial)

On Remand: Trial was venued to Hendricks County and Lowery was again convicted of Murder, Murder, Attempted Murder and sentenced to death and 50 years imprisonment by Judge Jeffrey V. Boles on 01-07-83.

Direct Appeal:

James Lowery v. State, 478 N.E.2d 1214 (Ind. 1985)

Conviction Affirmed 5-0 DP Affirmed 4-1

Pivarnik Opinion; Givan, Hunter, Prentice concur; Debruler dissents.

Lowery v. Indiana, 106 S. Ct. 1500 (1986) (Cert. denied)

PCR:

PCR Petition filed 07-18-86. PCR denied on 10-22-90 by Special Judge Thomas K. Milligan.

Lowery v. State, 640 N.E.2d 1031 (Ind. 1994)

(Appeal of PCR denial by Special Judge Thomas K. Milligan)

Affirmed 5-0 except Attempted Murder conviction reversed;

Debruler Opinion; Shepard, Dickson, Givan, Sullivan concur.

Habeas:

Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus filed 02-05-96 in U.S. District Court, Southern District of Indiana.

Writ denied 07-06-99 by U.S. District Court Judge David Hamilton.

Lowery v. Anderson, 69 F.Supp.2d 1078 (S.D. Ind. July 6, 1999)

(Petition denied by Judge David Hamilton)

Lowery v. Anderson, 225 F.3d 833 (7th Cir. August 29, 2000)

Affirming the denial of habeas corpus.

3-0 Circuit Judge Bauer Opinion, Flaum, Manion.

Lowery v. Anderson, 121 S.Ct. 1488 (April 2, 2001) (Cert. Denied)

Clemency:

Lowery v. Anderson, 138 F.Supp.2d 1128 (S.D. Ind. April 13, 2001)

(Order of Judge Hamilton granting the Motion for Appointment of Counsel for state clemency proceedings; Monica Foster and Brent Westerfield appointed; “the Court anticipates that a maximum of approximately 80 hours of attorney work may be ‘reasonably necessary’ in the clemency proceedings.”)

LOWERY WAS EXECUTED BY LETHAL INJECTION ON 06-27-01 12:29 AM EST. HE WAS THE 79TH CONVICTED MURDER EXECUTED IN INDIANA SINCE 1900, AND THE 9TH SINCE THE DEATH PENALTY WAS REINSTATED IN 1977.

James Lowery, then 32, was convicted of the murders of an elderly couple during a burglary. Mark and Gertrude Thompson were killed in their home in Tippecanoe County, shot in the head on September 30, 1979. Lowery and his wife had worked for the Lowerys as caretakers due to their poor health but had been fired a few months before. Lowery knew Mark Thompson was an attorney and thought it would be "easy money." Janet Brown, the Thompsons new caretaker, was also shot in the head but survived her injuries. Lowery went to the Thompson's home to rob them of $9,000 and gained entrance by holding a gun to Janet's head. Lowery immediately shot Mr. Thompson in the stomach, herded Janet and Mrs. Thompson into the kitchen and shot them both in the head. Janet managed to partially deflect the bullet with her hand, and she survived. Lowery then shot Mr. Thompson again.

UPDATE - Jim Lowery, 54, formerly of Crawfordsville, was pronounced dead at 12:29 a.m. Both the U.S. Supreme Court and the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals declined to intervene on Lowery's behalf Tuesday afternoon. Gov. Frank O'Bannon already had refused to commute his death sentence to one of life in prison. In his five-page denial of Lowery's request for clemency, O'Bannon noted that Lowery had benefited from the work of skilled attorneys and had been convicted and sentenced to death in 2 separate trials. The first verdict was overturned on procedural grounds. "24 jurors and 23 judges have found the death penalty appropriate in this case," O'Bannon wrote. "The process was fair, and I defer to the findings of the courts." Lowery's own stepdaughter, Heather Rice, said he used to press a gun to her head and pull the trigger when she was a child. The goal: intimidation. "Let this man finally be brought to justice," she said at the time. The board unanimously recommended against clemency.

"Lowery is Put to Death for 1979 Murders; Condemned Man Slept, Ate Usual Prison Food During Final Hours Before State Execution," by John Masson. (Indianapolis Star June 27, 2001)

MICHIGAN CITY, Ind. -- Convicted double-murderer James Lowery was executed by injection early this morning at the Indiana State Prison. Lowery was put to death at 12:29 a.m. for the 1979 slayings of an elderly Tippecanoe County couple. Afterward, his attorneys, Monica Foster and Brent Westerfeld, spoke to reporters outside the prison. Foster read a lengthy handwritten statement from Lowery that ended with the words: "I am so very sorry." Lowery had made no statement inside the prison before his execution, Foster said. In the final hours before the execution, supporters and opponents of the death penalty gathered in the parking lot outside the prison walls. The approximately 45 anti-death penalty protesters far outnumbered the handful of people who showed up to support the execution.

"I don't think it's ever right to kill somebody," said Nate Holdren, a recent graduate of Valparaiso University. "It would be a better world if we'd stop doing it." Nearby stood three pro-execution protesters; one held a sign that declared: "The penalty for murder is death." Holdren and two other Valparaiso graduates sat on a blanket, gazing at a candle. "I think it's simple hatred and a desire for vengeance," said Mia Cabibbo. "I'm all for protecting society. . . . I think we have systems in place to do that, and they're called prisons." Lowery spent much of Tuesday night sleeping, said Pam Pattison, a spokeswoman for the Indiana Department of Correction. Earlier, he met with his attorneys and the Rev. Paul LeBrun, who would administer the last rites, Pattison added. Tuesday afternoon, the U.S. Supreme Court and the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals declined to intervene on Lowery's behalf. Gov. Frank O'Bannon already had refused to commute his death sentence to one of life in prison. Still, Foster said, Lowery spent his last few hours thinking of others, not of himself. "He's clearly more concerned about the impact of his death on other people," said Foster, who has represented Lowery for 16 years. Just after midnight, a series of three drugs flowed into Lowery's veins. He became the third person executed in Indiana in 16 days. Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh and drug kingpin Juan Raul Garza were put to death by federal authorities near Terre Haute earlier this month. "Indiana has become the killing field, hasn't it?" Foster said.

John Krull, executive director of the Indiana Civil Liberties Union, warned against allowing the Hoosier state to become "the Texas of the North." "We're killing people as fast as Burger King makes hamburgers," Krull said after a sparsely attended noontime Statehouse gathering. Lowery was convicted of the murders of Mark and Gertrude Thompson, both 82 years old. He shot the couple during a robbery. He had been fired from his job as their caregiver a few months before. In denying clemency, O'Bannon noted that Lowery had benefited from the work of skilled attorneys and had been convicted and sentenced to death in two separate trials. The first verdict was overturned on procedural grounds. "Twenty-four jurors and 23 judges have found the death penalty appropriate in this case," O'Bannon wrote. "The process was fair, and I defer to the findings of the courts." But death penalty opponents decried that decision, especially in light of the horrific abuse Lowery is said to have suffered during his youth. The 54-year-old Lowery told Parole Board members earlier this month that he had been raped repeatedly by employees at a state-run mental institution. Supporters also cited his exemplary prison record. Charlie Kafoure of the Indiana Coalition To Abolish Capital Punishment noted Lowery's "heroic" role as a peacemaker on Death Row. But others told the Parole Board about a different Lowery. His own stepdaughter Heather Rice, said he used to press a gun to her head and pull the trigger when she was a child. The goal: intimidation. "Let this man finally be brought to justice," she said at the time. The board unanimously recommended against clemency.

Lowery asked LeBrun, Foster and Westerfeld to watch the execution. He declined a special last meal in favor of standard inmate fare, a prison spokesman said. "I think he would tell you that he views his death as a private thing," Foster said. "He really doesn't like the whole circus atmosphere."

USA (Indiana): James (Jim) Lowery, white, age 54Jim Lowery is scheduled to be executed in Indiana on 27 June 2001 after more than two decades on death row. Mark and Gertrude Thompson were murdered in their home on the night of 30 September 1979. Jim Lowery, who had briefly worked as the elderly couple's caretaker before being fired, was convicted of the murders and sentenced to death in 1980. He was retried in 1983 after winning an appeal, but was again convicted and sentenced to death.

The jury heard some evidence of Jim Lowery's background at the sentencing phase of the retrial, but the defence did not present much of the detail now available about his deprived and abused life before the crime. Specifically, it heard nothing about his appalling treatment in state mental facilities as a teenager. Jim Lowery was born in 1947 to a 14-year-old mother and an alcoholic father. His and his four siblings' childhood was marked by poverty and parental neglect. Jim Lowery first got into trouble as a young teenager, after taking his father's car for joyriding in. When he was 15 or 16, his parents took him to court and a judge committed him to a state mental facility, even though no evidence had been presented that he was mentally ill. The teenager ran away from the institution several times, telling his brothers and sisters that he had witnessed inmates being given electro-shock treatment and that he was afraid this would happen to him. He was transferred to the maximum security unit of another institution, the Norman Beatty Hospital, which has since been closed. There he was subjected to repeated gang rapes by staff. On occasion he was held in isolation, and he witnessed further electro-shock treatment. He was released at the age of 18. He took to drugs, alcohol, and property crime, and was in and out of the prison system until the crime for which he was sentenced to die.

Another former teenage inmate of Norman Beatty, Frank Davis, was sentenced in 1996 to life imprisonment for two murders. The sentencing judge rejected the prosecution's bid for a death sentence, stating: "the Court finds of great significance the fact that the State created the monster it now seeks to destroy. The mitigation provided by the horrors perpetrated upon Defendant while at Norman Beatty Hospital and while the State was in loco parentis with the Defendant, are so strong as to overcome the substantial aggravating circumstances also found in this case." As a 14-year-old, Davis was subjected to rape at the hands of other patients in the hospital.

At a clemency hearing on 18 June, the Indiana Parole Board heard testimony from a psychologist who recently diagnosed Jim Lowery as still suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of his treatment in the mental institutions. The psychologist also testified that Lowery should never have been placed in those facilities. The board also heard how Jim Lowery has been a model prisoner who has not had a single disciplinary write-up in his 22 years on death row and who has been entrusted with a job as a prison porter, which allows him to be out of his cell for extended periods of time. The board was told that Lowery had helped save another prisoner's life by calling attention to his suicide bid, and that he has been an important mediator between prisoners and the authorities at times when tensions on Indiana's death row have run high.

On 19 June, the parole board voted against clemency. Its chairman noted that there was "no question that [Lowery] was a model prisoner" whose record in the prison was "exemplary". Jim Lowery's fate is now in Governor O'Bannon's hands. Under Article 5, Section 17 of the Indiana Constitution, he has the power to override the Board's recommendation and grant clemency. Last year, Governor O'Bannon ordered a legislative study into the fairness of the state's use of the death penalty. That study is still in progress. Fourteen professors at the Notre Dame School of Law, Indiana, have signed a letter stating that it is "both unwise and inconsistent with elemental notions of fairness to conduct any execution" in Indiana while the system is being studied, given that it is "possible that the State of Indiana might execute a person who would have been entitled to the benefit of the Commission's work". The letter noted that in this regard "Mr Lowery's situation creates a risk of an erroneous execution". Another five law professors from Indiana University of Law have signed a similar statement.

"State Parole Board Recommends Killer's Execution; Governor Will Now Decide," by Kevin Corcoran.

June 19, 2001 - Jim Lowery's effort to spend the rest of his life in prison was dealt a setback Tuesday when the Indiana Parole Board voted unanimously to recommend proceeding with his execution by chemical injection. Citing the brutality of a double murder Lowery committed in 1979, the board's four members said the best interests of society would be served by killing him June 27 in the Indiana State Prison at Michigan City.

Lowery shot Mark and Gertrude Thompson, both 82, to death in their Tippecanoe County home during a robbery just months after the couple had fired Lowery and his wife as caregivers, according to court records.

"There were several points at which Mr. Lowery could have left the residence," said Valerie Parker, the board's vice chairman. "It was almost as if he seemed to enjoy the power he held over his victims."

Now, more than 20 years later, others are in control. Lowery and his attorneys say his life should be spared because of exemplary conduct in prison and repeated gang rapes they allege happened while Lowery, now 54, was confined to a state mental hospital as a teenager. "The state is now attempting to execute the monster that it created," said Monica Foster, one of Lowery's defense attorneys.

The Parole Board's recommendation will go to Gov. Frank O'Bannon, who is the only person who can commute Lowery's death sentence to life in prison without possibility of parole.

When Lowery was convicted, life in prison was not a sentencing option. Since it became law in 1993, defendants in capital murder cases have been nearly three times less likely to get death sentences, according to the Indiana Public Defender Council.

This change in the tide of murder prosecutions since Lowery's 1983 convictions has Foster and co-counsel Brent Westerfield scrambling in Lowery 's final days to achieve the holy grail of death penalty defense: a set of circumstances compelling enough for O'Bannon to let a Death Row inmate spend the remainder of his life behind bars. "We hope the governor's going to do the right thing," Foster said after the hearing. "We believe this is an extraordinary case."

James Lowery v. State, 434 N.E.2d 868 (Ind. May 5, 1982) (Direct Appeal).

Defendant was convicted before the Superior Court, Boone County, Paul H. Johnson, Jr., J., of murder and attempted murder, and he appealed. The Supreme Court, DeBruler, J., held that: (1) upon his timely pretrial motion for jury sequestration during trial for murder and attempted murder, defendant was entitled to have jury sequestered; (2) witness' taped statement to police before trial, offered and admitted after witness had testified she could not recall all of what she had said in statement and had left witness stand, was properly admitted over hearsay objection; (3) photograph of defendant taken on day of his arrest some two days following the charged crimes was properly admitted over objection; (4) where jury never saw plea bargain agreement between State and defendant's accomplice or knew that a polygraph examination had been administered to accomplice pursuant to agreement, any issue regarding propriety of admission of agreement because of reference therein to polygraph examination was moot on appeal; and (5) where defendant gave no waiver of appeal and no waiver of counsel, defendant was entitled to fullest assistance of counsel at every critical stage of appeal, including mandatory review of death sentence. Reversed. Givan, C. J., dissented and filed an opinion in which Pivarnik, J., concurred.

DeBRULER, Justice.

This is a direct appeal arising out of convictions on a three count indictment, charging two counts of murder and one count of attempted murder. The jury returned verdicts of guilty on each of the three counts, for the murders of an elderly couple living in West Point, Indiana, and the attempted murder of their housekeeper. The court found appellant guilty on each of the three counts and pursuant to the provisions of Ind.Code s 35-50-2-9 (Burns 1979) sentenced him to suffer the death penalty.

The following rulings are challenged on appeal and considered in this opinion:

1. The denial of a defense motion to sequester the jury throughout the trial.

2. The admission of a taped pre-trial statement.

3. The admission of a photograph of appellant.

4. The admission of an accomplice's plea agreement.

In addition to considering the above issues, the Court on its own considers for the guidance of the bench and bar the scope of the appellate lawyer's function in appeals from convictions resulting in the sentence of death.

The record shows the following facts. Appellant and an accomplice decided to rob Mark and Gertrude Thompson, an elderly couple living in a rural area of Tippecanoe County. Appellant armed himself with a .32 caliber revolver and set out with his partner for the Thompson home on September 30, 1979. At about 7:00 that evening, the pair entered the house trailer of the Thompson's housekeeper, which was parked near the home, and forced the housekeeper to enter the home with them. Upon confronting Mr. Thompson and having a brief exchange of words with him, appellant fired a non-fatal shot into Mr. Thompson's abdomen. Appellant directed his accomplice to guard Mr. Thompson while he sought out Mrs. Thompson, whom he found in the den and brought into the kitchen. Very shortly Mr. Thompson managed to trip a switch that set off a siren he had attached to his barn as a means of letting his neighbors know there was an emergency at his home. Appellant panicked upon hearing the siren and fired a single shot at point-blank range into Mrs. Thompson's head, killing her. He then turned to the housekeeper and fired a shot into her head. However, she had raised her hand to shield herself and the bullet had struck her hand first, thus reducing its velocity enough that it only barely penetrated her skull. She fell to the floor feigning death and survived. Appellant last went to Mr. Thompson and fired a single fatal shot into his head.

At appellant's trial, his accomplice and the housekeeper testified against him regarding the crime. His wife also testified regarding admissions he made to her about the murders. These admissions were made in front of the accomplice immediately after the pair returned to appellant's home in Crawfordsville.

The trial court denied a pre-trial defense motion for jury sequestration during the trial. The right asserted is based upon Public Law 1905, ch. 169, s 263, Ind.Code s 35-1-37-2 , which provides: "When the jurors are permitted to separate, after being impaneled, and at each adjournment, they must be admonished by the court that it is their duty not to converse among themselves, nor suffer others to converse with them, on any subject connected with the trial, or to form or express any opinion thereon, until the cause is finally submitted to them." Referring to this statute this Court has said: "At common law it was not permissible for a jury to separate even with the defendant's consent; but under our statute above quoted, it has been held and is the general practice that a jury be allowed to separate with the defendant's consent. McCorkle v. State (1859), 14 Ind. 39." Faulkner v. State, (1923) 193 Ind. 663, 669, 141 N.E. 514.

Separation of the jury proscribed in this statute occurs when jurors are permitted to return alone to the general community or to go to their respective homes, during the trial, after being duly admonished, and prior to the final charge by the court and the commencement of deliberations. The defendant's consent to separation will be presumed from a record of proceedings which is silent. Faulkner v. State, supra.

The application of this statute in cases in which the defendant faces the possibility of the imposition of the penalty of death has remained static since its enactment in 1905 to the date of this opinion. A timely request by the defendant for the jury to be kept together during the trial in a capital case places a mandatory duty upon the trial judge to grant the request. There is in such cases no discretion reposed in the trial court to deny that request, and no burden upon the defendant at trial or on appeal to make a showing of cause or prejudice. Whitaker v. State, (1960) 240 Ind. 676, 168 N.E.2d 212. Indeed, no case has presented itself in which a defendant has been ordered put to death by an American court as punishment for crime upon the verdict of a jury which was permitted to separate and return to commingle in the general community during the trial, over the timely objection of the accused. We therefore hold that it was reversible error for the court to deny the motion on the basis asserted and that consequently appellant must be granted a new trial.

James Lowery v. State, 478 N.E.2d 1214 (Ind. 1985) (Direct Appeal).

Defendant was convicted before the Superior Court, Boone County, Paul H. Johnson, Jr., J., of murder and attempted murder, and he appealed. The Supreme Court, 434 N.E.2d 868,

PIVARNIK, Justice.

On September 30, 1979, Mark and Gertrude Thompson were in their country home in West Point, Tippecanoe County, Indiana. Both Thompsons were past 80 years of age, in declining health, and needed assistance in caring for themselves and their property. On that date, both were killed by gunshot in their home. Before this date, the Thompsons had employed Defendant-Appellant James Lowery and his wife as caretakers. The Thompsons, dissatisfied with the Lowerys, asked them to *1219 leave and ordered them out of the provided trailer and off the property immediately. The Lowerys refused to leave that quickly and after some discussion, Mark Thompson gave the Lowerys a check for one-hundred ($100.00) dollars in exchange for leaving immediately. Weeks before September 30, Lowery and Jim Bennett discussed committing a crime for pecuniary gain. Lowery told Bennett he knew where he could get some money, but he did not disclose the place at that time. About three weeks prior to September 30, Bennett gave Lowery a .32 caliber nickel or chrome plated pistol and some ammunition. The gun was supposedly for Barbara Lowery's protection while Lowery was not home. On September 30, Bennett picked Lowery up and followed Lowery's directions. Bennett knew, in general, that they were driving to West Point to rob Lowery's former employers. Later, Lowery told Bennett more specifically that they were going to the Thompson's residence to force Mr. Thompson to write a check for nine-thousand ($9,000.00) dollars, then kill and bury both Thompsons. He also planned to take Thompson's gun collection. As they approached the Thompson residence around dark, Lowery carried the pistol and Bennett a sawed-off shotgun.

Janet Brown, housekeeper and caretaker for the Thompsons, was sitting in the trailer where she lived, adjacent to the Thompson's garage, reading a book when she heard the Thompson's dog bark, and a man with a gun in his hand kicked the door open and entered. Brown recalled having once met the man at the West Point Post Office. She and Lowery had struck up a conversation about their motorcycles. When she told Lowery she worked for the Thompsons, he had remarked that he too had worked for them at one time. He said Mark Thompson was all right but to watch out for Mrs. Thompson as she was hateful. He recounted how they were ordered to leave the Thompsons' and how he had first requested payment of one hundred ($100.00) dollars. Brown thought Lowery spoke hatefully of the Thompsons. She identified Jim Lowery as the man who came into the trailer with a gun the evening of September 30, 1979.

After Lowery broke into Brown's trailer, he held the gun against Brown's neck and forced her to take him to the Thompson's residence. Brown saw someone with Lowery but said she did not get a good look at him. Bennett testified similarly to Brown about these events. Lowery took Brown into the kitchen where Mark Thompson was standing. He told Thompson he was being held up and then shot him in the stomach. After shooting Mark Thompson, Lowery forced Brown, with a gun to her head, through the kitchen and down the hall to the den where Gertrude Thompson was watching television. Lowery ordered Mrs. Thompson to get up and move and as she was walking down the hall, he struck her in the head with the gun. Blood spurted from her head and she began to stagger.

After Lowery forced Brown and Mrs. Thompson into the kitchen, he shot Mrs. Thompson in the head and also shot Brown. Brown had her hand over her head when Lowery fired at her, causing injury to her hand and her head, but not fatally wounding her. As she lay bleeding, not sure how seriously she was injured, the burglar alarm began ringing. Mark Thompson apparently had activated it. She testified that at that time Lowery and the person with him became excited and Lowery went back to where Mark Thompson was and she heard two more shots. Lowery still wanted to find something to take from the house, but because the siren was ringing and they feared the police would come soon, Lowery and Bennett fled by way of the back roads. They returned to Lowery's place where they told Barbara Lowery about the shootings. After Lowery was apprehended by the police, he made several voluntary incriminating statements to numerous police officers. Later, in the jail cell, he admitted the perpetration of these crimes to his cellmate and detailed the manner in which they were executed.

* * *

An examination of the entire record, pursuant to our responsibility to review the imposition of the death penalty, clearly supports the conclusion that imposition of the death penalty was appropriate, considering the nature of the offense and the character of the defendant. As this opinion already amply demonstrates, there was proof beyond a reasonable doubt that this defendant intentionally killed the Thompsons. He expressed animosity toward them because of his prior relationship with them and further expressed a desire and intent to get money and property from them. The trial judge told the defendant during sentencing, "I can find no factor that mitigates in your favor in this case. You have nothing going for you except a brutal cold blooded pre-planned killing of old people." (Record at 207). At another point he stated, "There are no, there is no justification and not even the wildest theorist can provide the justification for what you did under any circumstances of logic or reason." (Record at 205). The record patently shows the egregious nature of these offenses and the character of this offender. The trial court carefully complied with the proper procedures pursuant to statute and case law, and we find that the imposition of death, recommended by the jury and imposed by the trial court, was not arbitrarily or capriciously arrived at and is reasonable and appropriate.

We affirm the trial court in its judgment, including its imposition of the death penalty. This cause is accordingly remanded to the trial court for the purpose of setting a date for the death sentence to be carried out.

GIVAN, C.J., and HUNTER, J., concur.

DeBRULER, J., concurs and dissents with separate opinion.

PRENTICE, J., concurs in result with separate opinion.

Lowery v. Anderson, 225 F.3d 833 (7th Cir. August 29, 2000) (Habeas).

After his convictions for murder and attempted murder and death sentence were affirmed following retrial, 478 N.E.2d 1214, petitioner sought state postconviction relief. Denial of relief was affirmed, 640 N.E.2d 1031, with respect to murder convictions and death sentence. Petitioner sought federal habeas corpus relief. The United States District Court for the Southern District of Indiana, David F. Hamilton denied petition. Petitioner appealed. The Court of Appeals, Bauer, Circuit Judge, held that: (1) prosecution made good faith effort to secure accomplice's testimony for petitioner's retrial; (2) any error in failure to present accomplice as live witness during retrial was harmless; (3) remarks of trial court and prosecutor did not unconstitutionally minimize jury's perception of its role in imposition of death penalty; and (4) petitioner did not receive ineffective assistance of counsel.

Affirmed.

BAUER, Circuit Judge.

Mark and Gertrude Thompson were murdered in their home on the night of September 30, 1979 by a man they once trusted as their caretaker. The Thompsons were an elderly couple and their declining health necessitated that they hire others to help care for them and their property. During the summer of 1979, Lowery and his wife Barbara filled that role.

Only a few months before the murders, Mark Thompson fired Jim Lowery and ordered him off the Thompson property. The loss of that job included the loss of the rent-free caretaker's trailer on the Thompson property, in which Lowery and his family lived, and the loss of the modest salary. At first, Lowery refused to accept his demise, pleading with Mark Thompson that he had no money and no place to go. Thompson, however, was so dissatisfied with the Lowerys' service that he offered Lowery $100.00 if he would leave the property immediately. Lowery took the money *837 and moved his family to an old school bus in a nearby campground.

On September 30, 1979, Lowery and his friend Jim Bennett drove to the Thompson's home intending to rob and murder the couple. Several weeks before, Lowery and Bennett had discussed committing a crime for pecuniary gain, as both were in need of money. Lowery told Bennett he knew where he could get some money, but it was not until they were in the car on their way to the Thompson's house that Lowery told Bennett that they were going to rob the Thompsons. Lowery's plan was to force Mark Thompson to write a check for $9,000 and then to kill and bury the couple. Lowery was armed with a pistol and Bennett a sawed-off shotgun.

Lowery and Bennett arrived at the Thompson's property around dark. Janet Brown, the new caretaker, was in the trailer reading a book when she heard the Thompson's dog bark. Seconds later, the trailer door was kicked in and an armed Lowery entered, leaving Bennett outside.

Ms. Brown later told police that she immediately recognized the man as the Thompson's former caretaker. The two had met at the post office a week earlier and had struck up a conversation. When she told Lowery that she worked for the Thompsons, Lowery admitted that he had been their previous caretaker and he spoke, she thought, hatefully of them.

Lowery put the pistol against Brown's neck and forced her to take him into the Thompson's house. Bennett joined them as they crossed the lawn to the house. Inside, they found Mark Thompson standing in the kitchen. Immediately upon seeing Lowery and being told that this was a “hold up,” Thompson said “You don't want to do this now, Jim.” Lowery responded by shooting him in the stomach.

After shooting Mark Thompson, Lowery forced Brown, with the gun to her head, through the kitchen, down the hall, and into the den where Gertrude Thompson was watching television. Lowery ordered Mrs. Thompson to get up and to go into the kitchen. She complied. As she was walking down the hall, Lowery hit her in the head with the gun. She began to bleed, but was able to make it into the kitchen, where Lowery shot her once in the head at close range. Gertrude Thompson died before help could arrive.

Lowery also shot Janet Brown, but because she put her hands in front of her, the shot was deflected and she was grazed but alive. She wisely lay on the floor pretending to be dead. As she lay there, she heard the burglar alarm sound. Somehow, despite his wound, Mark Thompson had activated it, obviously greatly distressing Lowery and Bennett. Lowery went back to where Mark Thompson was, and Brown heard two more shots. Lowery and Bennett then fled.

Later, when she was certain the two men were gone, Brown called the police. When they arrived, Gertrude Thompson was dead and Mark Thompson was dying from a gunshot wound to the head. Before his death, Mark Thompson was able only to say that four “monkeys” assaulted him. His son testified that Mr. Thompson used the term “monkeys” when he could not remember someone's name.

Using the back roads, Lowery and Bennett returned to the old school bus. They told Lowery's wife, Barbara, about the shootings. Lowery was arrested two days later. Bennett the day after that. After his arrest, Lowery made several incriminating statements to police officers. He also told his cellmate of his crimes, describing them in a detailed manner. Before trial he challenged the admissibility of these statements, but was successful in excluding only some.

The prosecution struck a deal with Bennett. In exchange for his testimony against Lowery and a plea of guilty, the State dropped the habitual offender charge against Bennett and its request for the death penalty. It also guaranteed Bennett a sentence of 40 years.

Bennett testified that he and Lowery had planned to rob the Thompsons and that Lowery shot the Thompsons and Ms. Brown during the attempted burglary. Brown identified Lowery in court and testified that he was the person who shot her and the Thompsons. Barbara Lowery also testified, recounting how her husband and Bennett left the camp with a handgun and a shotgun, saying they were “off on a caper.” When they returned later that night, she said, they were visibly upset and shaking, with Bennett explaining that it “went bad,” and, in Lowery's presence, saying “he” (meaning Lowery) shot them in the head. The jury convicted Lowery of two counts of murder and one count of attempted murder and recommended that he be put to death. The judge sentenced him to death. The Supreme Court of Indiana reversed Lowery's convictions on direct appeal because the trial court failed to sequester the jury. Lowery v. State, 434 N.E.2d 868 (Ind.1982). Lowery was tried a second time.

Bennett refused to testify at the second trial. He wanted a “better deal” on his plea bargain. The State refused. Bennett was brought before the court (out of the jury's presence) and refused to be sworn in. The court threatened to hold Bennett in contempt, but Bennett still refused to testify. He was held in contempt. The next day, this procedure was repeated and the same result obtained. Frustrated, the trial judge told Bennett that if he continued to refuse to testify, the court would order the prosecutor to bring murder charges against Bennett because he had violated his plea agreement. Both the prosecutor and the defense counsel agreed that such an order was beyond the scope of the court's authority and the court recanted. Before Bennett was aware that the threat of prosecution had been removed, however, he changed his mind and agreed to testify. That change was short lived. Once Bennett was advised that the only penalty for refusing to testify was to be held in contempt of court, he again refused to testify. The court then declared Bennett to be unavailable and allowed the prosecutor to read Bennett's testimony from the first trial to the jury. The jury convicted Lowery of the murders of Mark and Gertrude Thompson and the attempted murder of Janet Brown.

At the sentencing phase of the trial, the prosecution argued for the death penalty, saying it was justified because the murders were committed during an attempted burglary (an aggravating factor) and because there were multiple murders. Lowery's mother, father and youngest sibling testified on Lowery's behalf, as did a psychiatrist retained by the defense. Lowery also took the stand, admitting to the crimes. Nevertheless, the jury recommended the death penalty. The trial judge sentenced Lowery accordingly.

The Supreme Court of Indiana affirmed the murder convictions and death sentences. Lowery v. State, 478 N.E.2d 1214 (Ind.1985). However, it later reversed the conviction of attempted murder, saying the jury had been wrongly instructed on that count. Lowery v. State, 640 N.E.2d 1031 (Ind.1994). The State chose not to retry Lowery for the attempted murder. The U.S. District Court denied habeas relief. Lowery v. Anderson, 69 F.Supp.2d 1078 (S.D.Ind.1999) . Lowery appeals, claiming that the introduction of Bennett's prior testimony violated his Sixth and Fourteenth Amendment rights, that the State and trial court violated Caldwell v. Mississippi, 472 U.S. 320, 105 S.Ct. 2633, 86 L.Ed.2d 231 (1985), by leading the jury to believe that its recommendation to the judge concerning the death penalty carried less weight than in fact it does, and that he was denied effective assistance of counsel. We affirm.

* * *

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment of the District Court is affirmed.

Defendant was found guilty by a jury in the Hendricks Circuit Court in a bifurcated trial of two counts of murder and one count of attempted murder. The jury recommended the death penalty for each murder conviction. The trial court sentenced Defendant to death for the two murder convictions and to a term of fifty (50) years for the attempted murder conviction.

Fifteen issues have been presented for our determination in this direct appeal as follows:

1. whether the Indiana death penalty statute constitutes vindictive justice;

2. lack of specific rules governing the review of death sentences;

3. denial of Defendant's request for funds to hire an expert to assist counsel during jury selection;

4. refusal of the trial court to permit individual voir dire of each prospective juror;

5. denial of Defendant's Motion to Suppress;

6. error in admission of trial testimony of witness James Bennett;

7. error in admission of certain State exhibits;

8. error in admitting testimony of witness George Ross;

9. error in admission of Defendant's Exhibit E on motion of the prosecution;

10. admission of opinion testimony of Dr. Miller;

11. permission of Detective Payne to testify about a pretrial identification display;

12. allowing leading questions by the prosecution;

13. error in the giving of an accomplice instruction;

14. sufficiency of the evidence; and

15. error in finding that the aggravating factors outweighed the mitigating factors.

Jim Lowery is under sentence of death for the 1979 murders of Mark and Gertrude Thompson. A direct appeal to the Supreme Court of Indiana won him a new trial, but upon retrial he was again convicted and again sentenced to death. His appeals thereafter were fruitless. He petitioned for collateral relief, but his challenges to the murder convictions and death sentence were unsuccessful. His attempt to win a writ of habeas corpus from the U.S. District Court also failed. Now he is before us. We find that neither his conviction nor his sentence were the result of constitutional violations and affirm the District Court's decision to deny the writ.