Executed December 10, 2013 06:06 p.m. CDT by Lethal Injection in Oklahoma

37th murderer executed in U.S. in 2013

1357th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

4th murderer executed in Oklahoma in 2013

106th murderer executed in Oklahoma since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(37) |

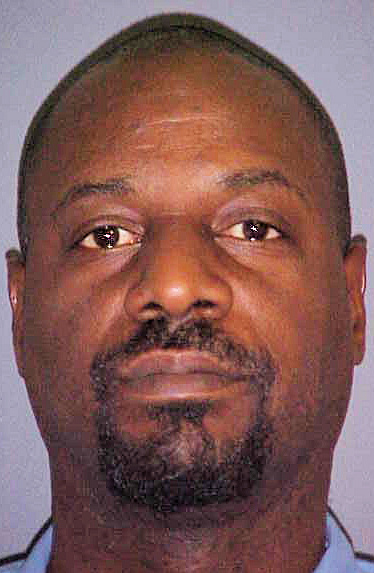

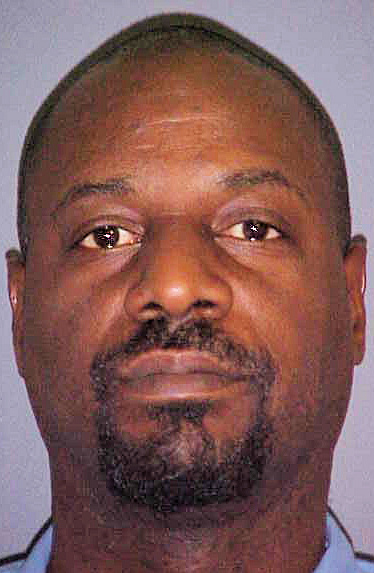

Ronald Clinton Lott B / M / 25, 26 - 53 |

Anna Laura Fowler W / F / 83 Zelma Cutler W / F / 93 |

01-11-87 |

Asphyxiation |

Citations:

Lott v. State, 2004 OK CR 27 (Okla. Crim. App. 2004). (Direct Appeal)

Lott v. Trammell, 705 F.3d 1167 (10th Cir. Okla. 2013). (Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

Fish, fries and hush puppies with tartar sauce and ketchup from Long John Silver's.

Final Words:

At the clemency hearing, Lott apologized to the victims’ families and asked for their forgiveness. “I’m so sorry for what I’ve done. And I’d ask them to forgive me.” Lott made no final statement at the execution.

Internet Sources:

Oklahoma Department of Corrections

RONALD C LOTTCASE# County Offense Conviction Term Start End

87-2865 OKLA Rape In The First Degree, Afcf 09/01/1987 25Y 0M 0D 09/14/1987 12/02/1998

87-2865 OKLA Burglary In The First Degree, Afcf 09/01/1987 25Y 0M 0D 09/14/1987 01/10/1998

87-2867 OKLA Burglary In The First Degree Afcf 09/01/1987 25Y 0M 0D 09/14/1987 12/02/1998

87-2867 OKLA Rape In The First Degree, Afcf 09/01/1987 25Y 0M 0D 09/14/1987 12/02/1998

87-2867 OKLA Robbery With Firearms, Afcf 09/01/1987 25Y 0M 0D 09/14/1987 12/02/1998

87-963 OKLA Murder In The First Degree (Death) 01/18/2002 12/10/2013

87-963 OKLA Murder In The First Degree (Death) 01/18/2002 12/10/2013

Death Penalty Information

The current death penalty law was enacted in 1977 by the Oklahoma Legislature. The method to carry out the execution is by lethal injection. The original death penalty law in Oklahoma called for executions to be carried out by electrocution. In 1972 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional the death penalty as it was then administered.

Oklahoma has executed a total of 176 men and 3 women between 1915 and 2011 at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary. Eighty-two were executed by electrocution, one by hanging (a federal prisoner) and 96 by lethal injection. The last execution by electrocution took place in 1966. The first execution by lethal injection in Oklahoma occurred on September 10, 1990, when Charles Troy Coleman, convicted in 1979 of Murder 1st Degree in Muskogee County was executed.

Execution Process

Method of Execution: Lethal Injection

Drugs used:

Sodium Thiopental or Pentobarbital - causes unconsciousness

Vecuronium Bromide - stops respiration

Potassium Chloride - stops heart

Two intravenous lines are inserted, one in each arm. The drugs are injected by hand held syringes simultaneously into the two intravenous lines. The sequence is in the order that the drugs are listed above. Three executioners are utilized, with each one injecting one of the drugs.

"Oklahoma executes man for killing women." (Associated Press Wednesday, December 11, 2013 10:27 am)

McALESTER, Okla. — Oklahoma on Tuesday executed a man who was convicted of killing two women — one 83, the other 93. Ronald Clinton Lott, 53, was pronounced dead at 6:06 p.m. after receiving a lethal injection at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester. Lott was the fifth Oklahoma death row inmate to be executed this year.

An Oklahoma County jury convicted Lott of two counts of first-degree murder in the deaths of Anna Laura Fowler, 83, in September 1986 and Zelma Cutler, 93, in January 1987. He was also convicted of raping the women. State and federal courts denied Lott’s appeals.

Fowler lived alone in Oklahoma City when Lott broke into her home through the back screen door and attacked her on Sept. 2, 1986. Authorities said Fowler was raped and a knotted cloth was used to bind her hands. She had multiple injuries, including rib fractures and bruising on her wrists, hands, eyes, lips and cheeks. She died from asphyxiation, and her grandson found her dead on her bed the next morning.

Cutler’s home was across the street from Fowler and she also lived alone. Police found her dead on her bed on Jan. 11, 1987. The electricity to Cutler’s home had been shut off at the breaker box and the phone wire had been cut. She had been raped and had multiple rib fractures and bruising. Another man was initially charged and convicted and was sentenced to death.

During the appeals process, DNA samples excluded the man and implicated Lott, who at the time was incarcerated for raping two other elderly women. In November, the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board voted 4-1 to deny commuting Lott’s death sentence to life in prison.

At the clemency hearing, Lott apologized to the victims’ families and asked for their forgiveness. “I’m so sorry for what I’ve done. And I’d ask them to forgive me,” Lott told board members, victims’ family members and others during a teleconference from the Oklahoma State Penitentiary at McAlester. “I caused them so much hurt and pain.” Lott initially told members of the Pardon and Parole Board that he wanted to waive his clemency hearing, but made a statement after his attorney pleaded with him to do so. He refused to ask the board to spare his life, though, despite his attorney’s pleas.

Jim Fowler, the son of Anna Fowler, urged the board to spare Lott’s life “and let him rot in that damn cell.” Oklahoma is scheduled to execute another inmate before the end of the year. Johnny Dale Black, 48, is scheduled to be executed Dec. 17 for the 1998 stabbing death of a Ringling horse trainer.

"Okla. executes man convicted of killing 2 women." (AP December 10, 2013 at 7:50 pm)

McALESTER, Okla. (AP) — Oklahoma on Tuesday executed a man who was convicted of killing two women — one 83, the other 93. Ronald Clinton Lott, 53, was pronounced dead at 6:06 p.m. after receiving a lethal injection at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester. Lott was the fifth Oklahoma death row inmate to be executed this year.

As the curtains opened, Lott looked over at his brother, who raised his fist and nodded. Lott made no final statement. He again looked at his brother in the first row of the viewing room as the drugs were pumped into his body, then Lott's eyes closed. He started breathing heavily and gasped for air three times. Following the pronouncement of death, corrections workers tried to close the curtains, but one wouldn't despite repeated attempts. They ended up hanging a white sheet over the window.

An Oklahoma County jury convicted Lott of two counts of first-degree murder in the deaths of Anna Laura Fowler, 83, in September 1986 and Zelma Cutler, 93, in January 1987. He was also convicted of raping the women. State and federal courts denied Lott's appeals. No members of the victims' families were in attendance, but an attorney for Lott was.

Fowler lived alone in Oklahoma City when Lott broke into her home through the back screen door and attacked her on Sept. 2, 1986. Authorities said Fowler was raped and a knotted cloth was used to bind her hands. She had multiple injuries, including rib fractures and bruising on her wrists, hands, eyes, lips and cheeks. She died from asphyxiation, and her grandson found her dead on her bed the next morning. Cutler's home was across the street from Fowler and she also lived alone. Police found her dead on her bed on Jan. 11, 1987. The electricity to Cutler's home had been shut off at the breaker box and the phone wire had been cut. She had been raped and had multiple rib fractures and bruising.

Another man was initially charged and convicted and was sentenced to death. During the appeals process, DNA samples excluded the man and implicated Lott, who at the time was incarcerated for raping two other elderly women.

In November, the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board voted 4-1 to deny commuting Lott's death sentence to life in prison. At the clemency hearing, Lott apologized to the victims' families and asked for their forgiveness. "I'm so sorry for what I've done. And I'd ask them to forgive me," Lott told board members, victims' family members and others during a teleconference from the Oklahoma State Penitentiary at McAlester. "I caused them so much hurt and pain." Lott initially told members of the Pardon and Parole Board that he wanted to waive his clemency hearing, but made a statement after his attorney pleaded with him to do so. He refused to ask the board to spare his life, though, despite his attorney's pleas. Jim Fowler, the son of Anna Fowler, urged the board to spare Lott's life "and let him rot in that damn cell."

Lott's last meal was fish, fries and hush puppies with tartar sauce and ketchup from Long John Silver's. A planned protest at the Governor's Mansion over the execution was cancelled due to inclement weather. Oklahoma is scheduled to execute another inmate before the end of the year. Johnny Dale Black, 48, is scheduled to be executed Dec. 17 for the 1998 stabbing death of a Ringling horse trainer.

"Oklahoma executes inmate," by Heide Brandes. (Tue Dec 10, 2013 11:07pm EST)

(Reuters) - Oklahoma on Tuesday executed a man convicted of raping and murdering two elderly women in the 1980s, while Missouri appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court to be allowed to proceed with an execution. Ronald Clinton Lott, 53, was pronounced dead at 6:06 p.m. Central Time (0006 GMT on Wednesday) after a lethal injection at a state prison in Oklahoma, state Department of Corrections spokesman Jerry Massie said. Lott was the 37th person executed in the United States this year, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

Lott was convicted of raping and killing Anna Laura Fowler, 83, in 1986 and Zelma Cutler, 90, in 1987 in their Oklahoma City homes. DNA evidence linked him to the crimes. He made no final statement, Massie said. "Ronald Lott was sentenced to death by a jury of his peers for the heinous and unconscionable acts he committed against Anna and Zelma in their homes," Attorney General Scott Pruitt said in a statement.

According to Oklahoma criminal appeals court records, evidence presented at trial suggested Lott attacked the women and sat on their chests, breaking their ribs. Both had numerous bruises and were asphyxiated. Another man, Robert Lee Miller Jr., had originally confessed to the rape and murder of the two women and served 11 years, seven on death row, before DNA evidence led authorities to Lott. Miller was released in 1998.

Lott was the fifth man executed in Oklahoma in 2013. The state is also scheduled to execute Johnny Dale Black, 48, on December 17 for his conviction in the 1998 stabbing death of Ringling, Oklahoma, horse trainer Bill Pogue.

"Man who killed, raped elderly Okla. women executed," by Kristi Eaton. (AP December 11, 2013)

McALESTER, Oklahoma (AP) — Oklahoma on Tuesday executed a man who was convicted of killing two women — one 83, the other 93. Ronald Clinton Lott, 53, was pronounced dead at 6:06 p.m. after receiving a lethal injection at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester. Lott was the fifth Oklahoma death row inmate to be executed this year.

As the curtains opened, Lott looked over at his brother, who raised his fist and nodded. Lott made no final statement. He again looked at his brother in the first row of the viewing room as the drugs were pumped into his body, then Lott's eyes closed. He started breathing heavily and gasped for air three times. Following the pronouncement of death, corrections workers tried to close the curtains, but one wouldn't despite repeated attempts. They ended up hanging a white sheet over the window.

An Oklahoma County jury convicted Lott of two counts of first-degree murder in the deaths of Anna Laura Fowler, 83, in September 1986 and Zelma Cutler, 93, in January 1987. He was also convicted of raping the women. State and federal courts denied Lott's appeals. Fowler lived alone in Oklahoma City when Lott broke into her home through the back door and attacked her on Sept. 2, 1986. Authorities said Fowler was raped and a knotted cloth was used to bind her hands. She had multiple injuries, including rib fractures and bruising on her wrists, hands, eyes, lips and cheeks. She died from asphyxiation, and her grandson found her dead on her bed the next morning. Cutler's home was across the street from Fowler and she also lived alone. Police found her dead on her bed on Jan. 11, 1987. The electricity to Cutler's home had been shut off at the breaker box and the phone wire had been cut. She had been raped and had multiple rib fractures and bruising.

In November, the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board voted 4-1 to deny commuting Lott's death sentence to life in prison. Jim Fowler, the son of Anna Fowler, urged the board to spare Lott's life "and let him rot in that damn cell." Oklahoma is scheduled to execute another inmate before the end of the year. Johnny Dale Black, 48, is scheduled to be executed Dec. 17 for the 1998 stabbing death of a Ringling horse trainer.

Oklahoma Coalition to Abolish Death Penalty

Sometime after 10:30 p.m., September 2, 1986, Anna Laura Fowler was attacked in her home, raped and murdered. Mrs. Fowler was 83 years old and lived alone. As a result of the attack, Mrs. Fowler suffered severe contusions on her face, arms and legs, and multiple rib fractures. She died from asphyxiation. Zelma Cutler lived across the street from Mrs. Fowler. Mrs. Cutler was 93 years old and lived alone. During the early morning hours of January 11, 1987, Mrs. Cutler was attacked, raped and murdered in her home. Mrs. Cutler suffered severe contusions on her arms and legs as a result of the attack. She also suffered multiple rib fractures. Mrs. Cutler died from asphyxiation. In both instances, the victims were vaginally raped and orally sodomized. Further, the evidence presented at trial suggested that Mrs. Fowler was anally raped and that the perpetrator attempted to anally rape Mrs. Cutler as well. Lastly, the evidence presented at trial suggested that the rib fractures sustained by both women occurred as a result of the perpetrator sitting directly on their chests and either orally sodomizing them and/or suffocating them with pillows after the attack.

Another individual, Robert Miller, was initially arrested, charged, and convicted of the Fowler and Cutler murders. But, notwithstanding Miller's arrest, two additional elderly women living in the Oklahoma City area were attacked and raped in their homes, in a manner similar to the attacks on Fowler and Cutler. And Lott proved to be responsible for those crimes: Subsequent to Miller's arrest, Grace M. was attacked and raped in her home on March 22, 1987. Eleanor H. was attacked and raped in her home on May 7, 1987. Both Mrs. M. and Mrs. H. were elderly ladies who lived alone. With the exception that Mrs. M. and Mrs. H. were not killed after being raped, there were striking similarities between the attacks on the four women.

Lott was arrested, charged, and ultimately pled guilty to committing the rapes against Mrs. M. and Mrs. H. In the early 1990s, DNA testing established that Lott, rather than Miller, had raped Mrs. Fowler and Mrs. Cutler. At that time, Lott was still incarcerated and serving time in connection with the other rape convictions.

On March 10, 1995, an amended information was filed in the District Court of Oklahoma County, Oklahoma, jointly charging Lott and Miller with two counts of first-degree malice aforethought murder (Count 1 was for the murder of Mrs. Fowler and Count 2 was for the murder of Mrs. Cutler) and, in the alternative, with two counts of first-degree felony murder. On January 30, 1996, however, those charges were dismissed at the request of the State. On or about March 19, 1997, the State reinstated the case by filing a third amended information against Lott and Miller. The trial court appointed the Oklahoma Indigent Defense System (OIDS) to represent Lott.

On March 20, 1998, the State filed a bill of particulars asserting that Lott “should be punished by death due to and as a result of” the existence of three “aggravating circumstance(s)”: (1) the murders were “especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel”; (2) the murders were “committed for the purpose of avoiding or preventing a lawful arrest or prosecution”; and (3) “[t]he existence of a probability that [Lott] would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society.”

On November 13, 2000, the State filed a fourth amended information. Although the fourth amended information continued to charge Lott with two counts of first-degree malice aforethought murder and, in the alternative, two counts of first-degree felony murder, the charging language differed significantly from that of the third amended information. Whereas the third amended information alleged that the first-degree malice aforethought murder counts, as well as the felony murder counts, were “feloniously committed · by Robert Lee Miller Jr. and Ronald Clinton Lott acting jointly and willfully,” the fourth amended information (a) omitted from the first-degree malice aforethought murder charges the allegations that Lott acted jointly with Miller, thus leaving only Lott as the named defendant in those counts, and (b) altered the felony murder counts to allege that Lott was “aided and abetted by Miller.”

The case proceeded to trial on October 29, 2001. But a mistrial occurred: In the middle of trial, the State requested a continuance when the medical examiner revealed he had evidence in his possession that had never been tested. The State requested the continuance so LabCorp could test the newly discovered evidence. The defense requested a mistrial. The State agreed to the mistrial if the defense would agree to stipulate to a continuance and stipulate to the chain of custody. The mistrial was granted and the trial rescheduled for December 3, 2001. The December 2001 trial proceeded as scheduled. At the conclusion of the first-stage evidence, the jury found Lott guilty of both murders.

At the conclusion of the second-stage proceedings, the jury found, with respect to each of the counts of conviction, the existence of two of the three alleged aggravating circumstances: that the murders were especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel, and that the murders were committed for the purpose of avoiding or preventing a lawful arrest or prosecution. The jury in turn fixed Lott's punishment at death for each of the two counts of conviction. On January 18, 2002, the state trial court formally sentenced Lott to death for each of the two murder convictions.

Oklahoma Attorney General (News Release)

News Release - Ronald C. Lott

December 10th at 6 p.m. Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester

Name: Ronald Lott

DOB: 09/22/1960

Sex: Male

Age at Date of Crime: 26

Victim(s): Anna Laura Fowler, 83 - Zelma Cutler, 93

Date of Crime(s): 9/2/1986 - 1/11/1987

Date of Sentence: 1/18/2002

Crime Location: Victim’s Home -1200 N.W. 31st Street, OKC – Anna Fowler

Crime Location: Victim’s Home- 1142 N.W. 31st Street, OKC- Zelma Cutler

Judge: Virgil C. Black

Prosecuting: Robert Macy, Wes Lane, Greg Mashburn, Richard Wintory

Defending: Craig D. Corgan, Wayna Tyner, Perry W. Hudson, John Albert

Circumstances Surrounding Crime:

Lott was found guilty by a jury of his peers and sentenced to death for the first degree murders of Anna Laura Fowler, 83, and Zelma Cutler, 93, both of Oklahoma City. Fowler and Cutler both lived alone across the street from each other in Oklahoma City. Lott entered their homes and brutally beat, raped and murdered both elderly women. Along with the murders of Fowler and Cutler, Lott beat and raped two other victims within a three mile radius of the first victims’ homes. Lott’s DNA was found at all four crime scenes.

Statement from Attorney General Scott Pruitt: “Ronald Lott was sentenced to death by a jury of his peers for the heinous and unconscionable acts he committed against Anna and Zelma in their homes,” Attorney General Scott Pruitt said. “My thoughts and prayers are with Anna Fowler’s and Zelma Cutler’s family and friends.”

Wikipedia: Oklahoma Executions

A total of 106 individuals convicted of murder have been executed by the State of Oklahoma since 1976, all by lethal injection:

1. Charles Troy Coleman 10 September 1990 John Seward

2. Robyn Leroy Parks 10 March 1992 Abdullah Ibrahim

3. Olan Randle Robinson 13 March 1992 Shiela Lovejoy, Robert Swinford

4. Thomas J. Grasso 20 March 1995 Hilda Johnson

5. Roger Dale Stafford 1 July 1995 Melvin Lorenz, Linda Lorenz, Richard Lorenz, Isaac Freeman, Louis Zacarias, Terri Horst, David Salsman, Anthony Tew, David Lindsey

6. Robert Allen Brecheen [1][2][3] 11 August 1995 Marie Stubbs

7. Benjamin Brewer 26 April 1996 Karen Joyce Stapleton

8. Steven Keith Hatch 9 August 1996 Richard Douglas, Marilyn Douglas

9. Scott Dawn Carpenter 7 May 1997 A.J. Kelley

10. Michael Edward Long 20 February 1998 Sheryl Graber, Andrew Graber

11. Stephen Edward Wood 5 August 1998 Robert B. Brigden

12. Tuan Anh Nguyen 10 December 1998 Amanda White, Joseph White

13. John Wayne Duvall 17 December 1998 Karla Duvall

14. John Walter Castro 7 January 1999 Beulah Grace, Sissons Cox, Rhonda Pappan

15. Sean Richard Sellers 4 February 1999 Paul Bellofatto, Vonda Bellofatto, Robert Bower

16. Scotty Lee Moore 3 June 1999 Alex Fernandez

17. Norman Lee Newsted 8 July 1999 Larry Buckley

18. Cornel Cooks 2 December 1999 Jennie Elva Ridling

19. Bobby Lynn Ross 9 December 1999 Steven Mahan

20. Malcolm Rent Johnson 6 January 2000 Ura Alma Thompson

21. Gary Alan Walker 13 January 2000 Eddie O. Cash, Valerie Shaw-Hartzell, Jane Hilburn, Janet Jewell, Margaret Bell Lydick, DeRonda Gay Roy

22. Michael Donald Roberts 10 February 2000 Lula Mae Brooks

23. Kelly Lamont Rogers 23 March 2000 Karen Marie Lauffenburger

24. Ronald Keith Boyd 27 April 2000 Richard Oldham Riggs

25. Charles Adrian Foster 25 May 2000 Claude Wiley

26. James Glenn Rodebeaux 1 June 2000 Nancy Rose Lee McKinney

27. Roger James Berget 8 June 2000 Rick Lee Patterson

28. William Clifford Bryson 15 June 2000 James Earl Plantz

29. Gregg Francis Braun 10 August 2000 Gwendolyn Sue Miller, Barbara Kchendorfer, Mary Rains, Pete Spurrier, Geraldine Valdez

30. George Kent Wallace 10 August 2000 William Von Eric Domer, Mark Anthony McLaughlin

31. Eddie Leroy Trice 9 January 2001 Ernestine Jones

32. Wanda Jean Allen 11 January 2001 Gloria Jean Leathers

33. Floyd Allen Medlock 16 January 2001 Katherine Ann Busch

34. Dion Athansius Smallwood 18 January 2001 Lois Frederick

35. Mark Andrew Fowler 23 January 2001 John Barrier, Rick Cast, Chumpon Chaowasin

36. Billy Ray Fox 25 January 2001

37. Loyd Winford Lafevers 30 January 2001 Addie Mae Hawley

38. Dorsie Leslie Jones, Jr. 1 February 2001 Stanley Eugene Buck, Sr.

39. Robert William Clayton 1 March 2001 Rhonda Kay Timmons

40. Ronald Dunaway Fluke 27 March 2001 Ginger Lou Fluke, Kathryn Lee Fluke, Suzanna Michelle Fluke

41. Marilyn Kay Plantz 1 May 2001 James Earl Plantz

42. Terrance Anthony James 22 May 2001 Mark Allen Berry

43. Vincent Allen Johnson 29 May 2001 Shirley Mooneyham

44. Jerald Wayne Harjo 17 July 2001 Ruther Porter

45. Jack Dale Walker 28 August 2001 Shely Deann Ellison, Donald Gary Epperson

46. Alvie James Hale, Jr. 18 October 2001 William Jeffery Perry

47. Lois Nadean Smith 4 December 2001 Cindy Baillee

48. Sahib Lateef Al-Mosawi 6 December 2001 Inaam Al-Nashi, Mohamed Al-Nashi

49. David Wayne Woodruff 21 January 2002 Roger Joel Sarfaty, Lloyd Thompson

50. John Joseph Romano 29 January 2002

51. Randall Eugene Cannon 23 July 2002 Addie Mae Hawley

52. Earl Alexander Frederick, Sr. 30 July 2002 Bradford Lee Beck

53. Jerry Lynn McCracken[10] 10 December 2002 Tyrrell Lee Boyd, Steve Allen Smith, Timothy Edward Sheets, Carol Ann McDaniels

54. Jay Wesley Neill 12 December 2002 Kay Bruno, Jerri Bowles, Joyce Mullenix, Ralph Zeller

55. Ernest Marvin Carter, Jr. 17 December 2002 Eugene Mankowski

56. Daniel Juan Revilla 16 January 2003 Mark Gomez Brad Henry

57. Bobby Joe Fields 13 February 2003 Louise J. Schem

58. Walanzo Deon Robinson 18 March 2003 Dennis Eugene Hill

59. John Michael Hooker 25 March 2003 Sylvia Stokes, Durcilla Morgan

60. Scott Allen Hain 3 April 2003 Michael William Houghton, Laura Lee Sanders

61. Don Wilson Hawkins, Jr. 8 April 2003 Linda Ann Thompson

62. Larry Kenneth Jackson 17 April 2003 Wendy Cade

63. Robert Wesley Knighton 27 May 2003 Richard Denney, Virginia Denney

64. Kenneth Chad Charm 5 June 2003 Brandy Crystian Hill

65. Lewis Eugene Gilbert II 1 July 2003 Roxanne Lynn Ruddell

66. Robert Don Duckett 8 July 2003 John E. Howard

67. Bryan Anthony Toles 22 July 2003 Juan Franceschi, Lonnie Franceschi

68. Jackie Lee Willingham 24 July 2003 Jayne Ellen Van Wey

69. Harold Loyd McElmurry III 29 July 2003 Rosa Vivien Pendley, Robert Pendley

70. Tyrone Peter Darks 13 January 2004 Sherry Goodlow

71. Norman Richard Cleary 17 February 2004 Wanda Neafus

72. David Jay Brown 9 March 2004 Eldon Lee McGuire

73. Hung Thanh Le 23 March 2004 Hai Hong Nguyen

74. Robert Leroy Bryan 8 June 2004 Mildred Inabell Bryan

75. Windel Ray Workman 26 August 2004 Amanda Hollman

76. Jimmie Ray Slaughter 15 March 2005 Melody Sue Wuertz, Jessica Rae Wuertz

77. George James Miller, Jr. 12 May 2005 Gary Kent Dodd

78. Michael Lannier Pennington 19 July 2005 Bradley Thomas Grooms

79. Kenneth Eugene Turrentine 11 August 2005 Avon Stevenson, Anita Richardson, Tina Pennington, Martise Richardson

80. Richard Alford Thornburg, Jr. 18 April 2006 Jim Poteet, Terry Shepard, Kevin Smith

81. John Albert Boltz 1 June 2006 Doug Kirby

82. Eric Allen Patton 29 August 2006 Charlene Kauer

83. James Patrick Malicoat 31 August 2006 Tessa Leadford

84. Corey Duane Hamilton 9 January 2007 Joseph Gooch, Theodore Kindley, Senaida Lara, Steven Williams

85. Jimmy Dale Bland 26 June 2007 Doyle Windle Rains

86. Frank Duane Welch 21 August 2007 Jo Talley Cooper, Debra Anne Stevens

87. Terry Lyn Short[4] 17 June 2008 Ken Yamamoto

88. Jessie Cummings 25 September 2008 Melissa Moody

89. Darwin Brown 22 January 2009 Richard Yost

90. Donald Gilson 14 May 2009 Shane Coffman

91. Michael DeLozier 9 July 2009 Orville Lewis Bullard, Paul Steven Morgan

92. Julius Ricardo Young 14 January 2010 Joyland Morgan, Kewan Morgan

93. Donald Ray Wackerly II 14 October 2010 Pan Sayakhoummane

94. John David Duty 16 December 2010 Curtis Wise

95. Billy Don Alverson 6 January 2011 Richard Kevin Yost

96. Jeffrey David Matthews 11 January 2011 Otis Earl Short Mary Fallin

97. Gary Welch 5 January 2012 Robert Dean Hardcastle

98. Timothy Shaun Stemple 15 March 2012 Trisha Stemple

99. Michael Bascum Selsor 1 May 2012 Clayton Chandler

100. Michael E. Hooper 14 August 2012 Cynthia Jarman, Timothy Jarman, Tonya Jarman

101. Garry T. Allen 06 November 2012 Gail Titsworth

102. George Ochoa 04 December 2012 Francisco Morales, Maria Yanez

103. Steven Ray Thacker 12 March 2013 Laci Dawn Hill

104. James L. DeRosa 18 June 2013 Curtis and Gloria Plummer

105. Brian Darrell Davis 25 June 2013 Jody Sanford

106. Ronald C. Lott 10 December 2013 Anna Laura Fowler, Zelma Cutler

Lott v. State, 2004 OK CR 27 (Okla. Crim. App. 2004). (Direct Appeal)

PROCEDURAL POSTURE: Defendant sought review of the decision of the District Court of Oklahoma County (Oklahoma), which convicted him of two counts of first-degree murder in violation of Okla. Stat. tit. 21, § 701.7 (Supp. 1985) and sentenced him to death on each count.

OVERVIEW: Defendant was convicted of two counts of first-degree murder for the brutal killings of two elderly women. The jury recommended the sentence of death on each count and the trial court sentenced accordingly. The court affirmed, stating that it could not say that the jury was influenced by passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor contrary to Okla. Stat. tit. 21, § 701.13(C) (2001), in finding that the aggravating circumstances outweighed the mitigating evidence. Further, the court held that defendant was not denied his right to a speedy trial, stating that although continuances resulted in delay, the trial court did not abuse its discretion in granting them because it gave the defense time to investigate evidence recently turned over by the State. The trial court did not err in refusing to sever the two murder charges and try him separately for each offense because the evidence was sufficient to find that proof of each offense overlapped so as to evidence a common scheme or plan. Further, he failed to show any prejudice resulting from the joinder. The trial court did not err on instructing the jury on aiding and abetting because they were warranted by the evidence.

OUTCOME: The judgment was affirmed.

LUMPKIN, JUDGE:

Appellant Ronald Clinton Lott was tried by jury and convicted of two counts of First Degree Murder (21 O.S.Supp. 1985, § 701.7), Case No. CF-87-963, in the District Court of Oklahoma County. The jury found the existence of two aggravating circumstances in each count and recommended the punishment of death for each count. The trial court sentenced accordingly. From this judgment and sentence Appellant has perfected this appeal. 1

1 Appellant's Petition in Error was filed in this Court on July 17, 2002. Appellant's brief was filed September 5, 2003. The State's brief was filed January 5, 2004. The case was submitted to the Court January 13, 2004. Appellant's reply brief was filed January 26, 2004. Oral argument was held June 8, 2004.

Sometime after 10:30 p.m., September 2, 1986, Anna Laura Fowler was attacked in her home, raped and murdered. Mrs. Fowler was 83 years old and lived alone. As a result of the attack, Mrs. Fowler suffered severe contusions on her face, arms and legs, and multiple rib fractures. She died from asphyxiation. Zelma Cutler lived across the street from Mrs. Fowler. Mrs. Cutler was 93 years old and lived alone. During the early morning hours of January 11, 1987, Mrs. Cutler was attacked, raped and murdered in her home. Mrs. Cutler suffered severe contusions on her arms and legs as a result of the attack. She also suffered multiple rib fractures. Mrs. Cutler died from asphyxiation.

Robert Miller was arrested, charged, and ultimately convicted of the rapes and murders of Mrs. Fowler and Mrs. Cutler. Subsequent to Miller's arrest, Grace Marshall was attacked and raped in her home on March 22, 1987. Eleanor Hoster was attacked and raped in her home on May 7, 1987. Both Mrs. Marshall and Mrs. Hoster were elderly ladies who lived alone. With the exception that Mrs. Marshall and Mrs. Hoster were not killed after being raped, there were striking similarities between the attacks on the four women. Appellant was arrested, charged, and ultimately plead guilty to committing the rapes against Mrs. Marshall and Mrs. Hoster.

In approximately 1992, during Robert Miller's appeal period, Miller was excluded as the source of semen in the Fowler/Cutler cases through DNA testing. DNA testing subsequently implicated Appellant as the source of the semen. While Appellant was incarcerated for the Marshall/Hoster crimes, he was charged with two counts of malice aforethought murder or in the alternative first degree felony murder for the murders of Mrs. Fowler and Mrs. Cutler.

PRE-TRIAL ISSUES

In his first assignment of error, Appellant contends the trial court erred in refusing to dismiss the charges based upon the denial of his constitutional rights to a speedy trial under the Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution and Article II, §§ 6 and 20 of Oklahoma's Constitution. 2

2 The speedy trial provision of the Sixth Amendment provides, "In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district where the crime shall have been committed….". Similarly, Section 20 of the Oklahoma Constitution states, in part, "In all criminal prosecutions the accused shall have the right to a speedy and public trial by an impartial jury of the county in which the crime shall have been committed….". Section 6 of the Oklahoma Constitution reinforces the importance of this constitutional right by stating, "The courts of justice of the State shall be open to every person, and speedy and certain remedy afforded for every wrong and for every injury to person, property, or reputation; and right and justice shall be administered without sale, denial, delay, or prejudice." Oklahoma does not have a speedy trial act which sets forth a specific period of time for a matter to be brought to trial. But see Uniform Criminal Extradition Act, 22 O.S. 1991, § 1347.

When reviewing a claim of the denial of the constitutional right to a speedy trial, we apply the four balancing factors established by the United States Supreme Court in Barker v. Wingo, 407 U.S. 514, 530, 92 S. Ct. 2182, 2192, 33 L. Ed. 2d 101 (1972): (1) length of the delay; (2) reason for the delay; (3) the defendant's assertion of his right, and (4) prejudice to the defendant. These are not absolute factors, but are balanced with other relevant circumstances in making a determination. See Rainey v. State, 1988 OK CR 65, 1988 Okla. Crim. App. LEXIS 65, P3, 755 P.2d 89, 90. Appellant claims all four factors clearly weigh in his favor and that his speedy trial right has been unquestionably denied.

Regarding the length of delay, Appellant was originally charged on March 10, 1995, by amended information, with the commission of the Fowler/Cutler murders. On January 30, 1996, those charges were dismissed by the State with the intent to refile at a later date. At that time, Appellant was incarcerated for the Marshall/Hoster rapes. Appellant argues the ten months between the filing and dismissal of the original charges should be counted in considering the length of delay factor. In United States v. MacDonald, 456 U.S. 1, 8, 102 S. Ct. 1497, 1502, 71 L. Ed. 2d 696 (1982), the United States Supreme Court held that "once charges are dismissed, the speedy trial guarantee is no longer applicable." Appellant's reliance on Klopfer v. North Carolina, 386 U.S. 213, 87 S. Ct. 988, 18 L. Ed. 2d 1 (1967) is misplaced. In Klopfer, the prosecutor was able to suspend proceedings indefinitely; the charges were not dismissed. Id., at 214, 87 S. Ct. at 989. In the present case, Appellant was incarcerated for a separate crime at the time, therefore no due process violation occurred. See McDonald, 456 U.S. at 8, 102 S. Ct. at 1502.

Charges against Appellant for the Fowler/Cutler murders were refiled by a Third Amended Felony Information on March 19, 1997. The trial began December 3, 2001. Therefore the length of delay was approximately 4 years and 10 months. 3 This was a substantial delay and is sufficient, under our case law, to necessitate a review of the other three factors. See Ellis v. State, 2003 OK CR 18, P30, 76 P.3d 1131, 1136. 4

3 An earlier jury trial was begun October 29, 2001. In the middle of trial, the State requested a continuance when the medical examiner revealed he had evidence in his possession that had never been tested. The State requested the continuance so LabCorp could test the newly discovered evidence. The defense requested a mistrial. The State agreed to the mistrial if the defense would agree to stipulate to a continuance and stipulate to the chain of custody. The mistrial was granted and the trial rescheduled for December 3, 2001. Appellant waived his right to a speedy trial as to the December trial date.

4 In Ellis, we cited to 22 O.S.Supp. 1999, § 812.1, which indicates our Legislature considers any delay beyond one-year to require special review by the District Court. We further noted that even under the former statute, § 812, we have generally regarded the twelve-month interval as a threshold period of time in the speedy trial inquiry.

We next consider the second factor, the reason for the delay. Barker v. Wingo speaks of a "valid reason" for the delay. However, our statute speaks of "appropriateness of the cause of the delay," while the former statute spoke of "good cause." 5 All of these phrases have essentially the same meaning and require the reviewing court to ascertain what is causing the delay and then to ask if the cause is reasonable. Id. Further, Barker v. Wingo recognized that the second factor depends on the circumstances of the case. Deliberate delay weighs heavily against the government. Neutral reasons, like negligence or crowded courts, weigh slightly in a defendant's favor, for "ultimate responsibility for such circumstances must rest with the government rather than with the defendant." Barker v. Wingo, 407 U.S. at 531, 92 S. Ct. at 2192. And a "valid reason, such as a missing witness, should serve to justify appropriate delay." Id. Ellis, 2003 OK CR 18, P47-48, 76 P.3d at 1139 (footnote omitted).

5 22 O.S.Supp. 1999, § 812.1(A), provides in pertinent part, "If any person charged with a crime and held in jail solely by reason thereof is not brought to trial within one (1) year after arrest, the court shall set the case for immediate review as provided in Section 2 of this act, to determine if the right of the accused to a speedy trial is being protected." This provision was enacted in 1999 and became effective on November 1, 1999. However, it is basically an amendment to sections 811 and 812, which have been the law since 1910, but were repealed when the new version was enacted. 22 O.S. 1991, § 812, repealed in 1999. provided, "If a defendant prosecuted for a public offense, whose trial has not been postponed upon his application, is not brought to trial at the next term of court in which the indictment or information is triable after it is filed, the court must order the prosecution to be dismissed, unless good cause is shown."

Appellant's case was set for trial to begin on May 22, 2000. This date was stricken at the request of the defense in order to allow Appellant to produce evidence in support of a Motion to Dismiss for Speedy Trial. A hearing was held on Appellant's motion on May 26, 2000. On June 2, 2000, the trial court denied the motion to dismiss and issued a detailed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law. See Appendix.

In its Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, the trial court found several reasons for the delay. The court also stated that the delay was not solely attributable to the State. The preliminary hearing began 8 months after charges had been refiled. It was continued on six different dates until it was completed March 20, 1998. The trial court found that at no time during the course of the hearing did the defense raise an objection to the lengthy nature of the hearing. Under our review of the voluminous record, we cannot dispute that claim. At the conclusion of the hearing, Appellant requested immediate receipt of the preliminary hearing transcripts at public expense. The record reflects a delay of approximately six months, with the final transcript filed in September 1998. The trial court found that defense counsel's request for a completed transcript was reasonable as the evidence presented at the preliminary hearing was relevant to the court's pre-trial rulings.

In a Supplemental Brief, Appellant challenges the trial court's finding that this delay was due to the preparation of preliminary hearing transcripts. Appellant asserts trial counsel never requested a continuance based on the lack of transcripts. Even if counsel did not request a continuance on this basis, we find the trial court's ruling that such transcripts were necessary and relevant for pre-trial rulings to be reasonable.

Appellant argues the delay from preliminary hearing to pre-trial was due instead to the fact that the assigned judge, Judge Owens, was retiring in January 1999 and simply did not want to try the case. Appellant relies on Ellis where we stated, "under the statute, it is clearly the trial judge's responsibility to manage his or her docket in such a way that ensures the right to speedy trial is being protected". 2003 OK CR 18, P50, 76 P.3d at 1139.

In this regard, the trial court found the case was delayed due to scheduling conflicts of both court and counsel. The trial court found that the docket of Judge Owens was such that he could not have tried a case of this magnitude during the four month time period encompassing the final completion of the preliminary hearing transcript and the date of his retirement. The trial court noted that Judge Owens chose not to hear any pre-trial motions in this case as he would not be the presiding judge at trial. The trial court found no defense request for trial during the time the case was pending before Judge Owens.

Section 812.2(A)(2)(g) and (i) require the court to look at whether the delay occurred because "the court has other cases pending for trial that are for persons incarcerated prior to the case in question, and the court does not have sufficient time to commence the trial of the case within the time limitation fixed for trial," and "the court, state, accused, or the attorney for the accused is incapable of proceeding to trial due to illness or other reason and it is unreasonable to reassign the case." While we do not know from the record whether Judge Owens had other cases pending for trial that were for persons incarcerated longer than Appellant, we do have the trial court's finding that Judge Owens' docket was such that he could not try a case of this complexity prior to his retirement. While these delays appear to be a deliberate postponement of the case, taking judicial notice of the large caseload of criminal cases in the District Court of Oklahoma County, and the complex nature of the present case, we do not dispute the trial court's finding that the delay pending Judge Owens' retirement was reasonable. 6 Therefore, this delay does not weigh in Appellant's favor.

6 Appellant argues the case was passed four times while assigned to Judge Owens without Appellant's or defense counsel's knowledge, appearance or consent. Appellant states in his brief that each time counsel appeared, he would be informed that the case had been passed and Judge Owens would not meet with him. Appellant contends that finally defense counsel complained and was told by the bailiff that Judge Owens did not intend to do anything on the case because he was retiring in 1999. The record does not support Appellant's allegations, although we recognize the difficulty in proving such claims. If in fact, Appellant's claims are true that he was not able to meet with the judge and informed by a third party that the judge did not intend to act on the case pending his retirement, it was defense counsel's responsibility to request reassignment of the case to a different judge. There is no evidence of such in this case. However, we also note that as part of properly managing their caseload, judges who find it impossible to complete a case before retirement, should seek to reassign the case as soon as possible.

In February 1999, the case was reassigned to Judge Bragg. However, she shortly thereafter recused herself from the case. The case was assigned to Judge Black on March 1, 1999, and pre-trial hearings were commenced. However, it would be another two years and seven months before trial would begin. The trial court found this was due to the change in defense counsel (three attorneys from the Oklahoma Indigent Defense System since preliminary hearing), and scheduling conflicts of all parties concerned. As a result of the scheduling conflicts, the trial court convened a three-judge panel to resolve the conflicts and schedule major cases involving the attorneys in Appellant's case. Appellant's case was set for trial on March 27, 2000. While Appellant criticizes the convening of this three-judge panel, he does not offer an alternative solution to resolving the scheduling conflicts between court and counsel. We find the trial court acted responsibly in convening the panel in order to resolve the conflicts and expedite Appellant's case.

Trial did not begin on March 27, 2000, but was delayed due to requests for continuance from the State for additional time for forensic analysis, the postponement of scheduled testing by LabCorp so the defense could have an expert present during testing, and Appellant's Motion to Dismiss for lack of a Speedy Trial. In its order denying the motion to dismiss, the trial court stated that the State and the court could have tried the case in May or June 2000, but at the request of the defense, proceedings were stayed pending resolution of the motion. The motion to dismiss was denied June 2, 2000, and trial was rescheduled to November 13, 2000, to allow Appellant to seek extraordinary relief with this Court. On July 3, 2000, Appellant appealed to this Court from the District Court's order denying his motion to dismiss for lack of speedy trial. On August 17, 2000, this Court declined jurisdiction and dismissed the appeal. This mandamus action does not weigh in Appellant's favor as it was ultimately unsuccessful and caused a further delay of eight months. However, "by the same token, we recognize a mandamus action is not the same as an interlocutory appeal and the remedy was sought, at least in part, to protect his speedy trial endeavors." Ellis, 2003 OK CR 18, P56, 76 P.3d at 1140, citing United States v. Loud Hawk, 474 U.S. 302, 316, 106 S. Ct. 648, 656, 88 L. Ed. 2d 640 (1986)(finding delay attributable to defendant's interlocutory appeal "ordinarily will not weigh in favor of a defendant's speedy trial claims.")

The record reflects that from the November 2000 trial date, trial was rescheduled approximately three times (March 26, 2001; September 10, 2001; and October 29, 2001). These delays were the result of additional forensic testing. Appellant argues this delay was a "concerted effort on the part of the State and the trial court to allow the State to continue to investigate and strengthening (sic) its case". To the contrary, the record reflects an effort by the trial court to ensure the parties had all necessary evidence before proceeding to trial.

The record reflects that certain delays from the November 2000 trial date to October 2001 when the first trial began were the result of the State failing to timely comply with the Discovery Code. The trial courts are empowered to order the appropriate relief for the failure to comply with a discovery order. 22 O.S.Supp. 1996, § 2002(E)(2). Although the continuances resulted in further delay, the trial court did not abuse its discretion in granting the continuances as it gave the defense time to investigate evidence recently turned over by the State. Further, considering the recent availability of the new mitochondrial analysis of DNA evidence during the pendency of the proceedings, the continuances for additional forensic testing were reasonable and prudent.

In March 2001 an issue arose as to the involvement of Joyce Gilchrist, forensic chemist with the Oklahoma City Police Department and potential witness in the case. Prior to selecting a jury for the start of trial on March 26, 2001, the trial court held an in-camera hearing on the matter. It was revealed that there was an ongoing internal review within the police department of Ms. Gilchrist's work. The defense indicated to the court that it would be ineffective in announcing ready for trial at that time without further information on the Gilchrist matter; however, the defense did not want a continuance based upon the speedy trial claim. As a third alternative, the defense moved for a dismissal of the case.

The trial court denied the motion to dismiss, and with a jury waiting to be selected, informed the defense it had to choose between going forward with trial or continuing the case. After giving defense counsel time to consult with Appellant, defense counsel announced that based upon the need for additional investigation that could lead to exculpatory evidence, a continuance was requested. However, the defense did not want to relinquish its claim to a speedy trial. The State objected to the continuance and argued Appellant could not assert a speedy trial claim and request a continuance. The State argued Ms. Gilchrist had minimal involvement in this case and was not the sole tester of the evidence. The State also argued the defense had been aware for some time prior to the start of trial of Ms. Gilchrist's involvement in the case and the controversy surrounding her work.

Noting the presence of victims in the courtroom waiting for the start of trial, potential jurors waiting outside the courtroom for the start of voir dire, the State's announcement of ready for trial, the court's own ability to try the case that day, and the court's misgivings about the necessity of a continuance based upon the Gilchrist matter, the trial court informed defense counsel he would have to choose between a request for a continuance and exercise of his speedy trial claim. The court informed Appellant that if he requested the continuance, he would have to waive the speedy trial claim. Appellant chose the continuance and jury trial was rescheduled to September 10, 2001. On August 30, 2001, the trial court convened a hearing to inform the parties that due to another jury trial, Appellant's trial would not proceed on September 10, 2001. Appellant objected on speedy trial grounds. The court noted that due to its heavy caseload, the earliest it could try the case would be October 29, 2001.

We agree with the trial court's finding that the delay in this case was not solely attributable to the State. The State, the defense, and the court can all be held accountable for delays in this case. However, on the record, the majority of the delays were for good cause and not deliberate attempts to slow the process by either party. Considering the complexity of this case, the discovery of the availability of the new mitochondrial analysis of DNA evidence during the pendency of the proceedings, the majority of the delays were necessary to further the ends of justice and ensure that Appellant received a fair and impartial trial. See McDuffie v. State, 1982 OK CR 150, P7, 651 P.2d 1055, 1056. As for the third factor, assertion of the right by the accused, incarceration makes the demand for one in custody. See McDuffie, 1982 OK CR 150, P8, 651 P.2d at 1056. Additionally, Appellant made an affirmative request for a speedy trial on at least nine different occasions. As we noted in Ellis, 2003 OK CR 18, P45, 76 P.3d at 1139, "the defendant's assertion of his speedy trial right, then, is entitled to strong evidentiary weight in determining whether the defendant is being deprived of the right " (quoting Barker, 407 U.S. at 531-32, 92 S. Ct. at 2192-93). The third factor weighs in Appellant's favor.

Our fourth and final consideration concerns the prejudice, if any, worked upon Appellant from the delays in this case. In Ellis, this Court stated: Both parties correctly noted that the United States Supreme Court has held that an affirmative demonstration of prejudice is not a prerequisite to a claim of denial of the right to speedy trial and that prejudice is not limited to detriment to the defense of the accused. Moore v. Arizona, 414 U.S. 25, 94 S. Ct. 188, 38 L. Ed. 2d 183 (1973). Nevertheless, prejudice is one of the factors that must be considered, and Barker v. Wingo outlined three types: oppressive pretrial incarceration; anxiety and concern of the accused; and impairment of the defense. Of these factors, the Supreme Court considers the third the most serious "because the inability of a defendant adequately to prepare his case skews the fairness of the entire system." Barker v. Wingo, 407 U.S. at 532, 92 S. Ct. at 2193; but see Doggett v. United State, 505 U.S. 647, 661-65, 120 L. Ed. 2d 520, 112 S. Ct. 2686, 2695-698 (Thomas, dissenting) (noting Barker's suggestion that preventing prejudice to the defense is a fundamental objective of the speedy trial clause is "plainly dictum" and contradicted by holdings of other cases). 2003 OK CR 18, P58, 76 P.3d at 1140-1141.

Appellant argues prejudice is evident because had his case gone to trial as mandated by 22 O.S. 1991, § 812, in effect at the time of the first trial setting, the State's evidence would have consisted of DNA evidence by Brian Wraxall only. Wraxall testified at trial that his analysis of the evidence showed Appellant's DNA was consistent with all nine markers in the best samples taken from the crime scenes and was sufficient for him to identify Appellant as the source of the semen. This was the evidence the State had at preliminary hearing. Appellant asserts he would have challenged Wraxall's credibility and expertise based on extensive impeachment material available to the defense. However, due to the delays in the case, the State was able to present testimony from Megan Clement of LabCorp who testified that a sperm fraction of a vaginal swab taken from Mrs. Fowler was tested and a profile in 13 different areas of DNA obtained. Ms. Clement testified that the random match probability that Appellant was the donor of the sperm found in the vaginal swab was 1 in 157 quadrillion. At trial, Wraxal offered no such statistical probabilities, and the defense did not impeach him because Ms. Clement's testimony was more damaging.

The delays in the trial did not prevent Appellant from challenging the expertise and credibility of any of the experts conducting the DNA analysis. Further, the science of DNA testing is rapidly progressing and it was to the benefit of both the State and the defense to have the evidence subjected to the latest and most accurate type of analysis. Such testing could have very easily been exculpatory and therefore benefited Appellant. The fact that the results proved favorable to the State and not Appellant is not grounds upon which to base a finding of prejudice. This case is distinguishable from Ellis, in that the delays in Ellis were based upon the State's search for evidence against the defendant. In the present case, all of the evidence had been gathered, no new evidence was sought. It was merely a question of analyzing that evidence in the most accurate method possible. We find Appellant was not prejudiced by the delays as his defense was not hindered or impaired.

Appellant further argues the delay in not only going to trial but in charging him created significant difficulties for the defense in obtaining mitigation records and locating mitigating witnesses. Appellant asserts that with fourteen years having passed between the first homicide and trial, he was unable to obtain important evidence such as juvenile records, hospital records, and contact with friends and family that would have been helpful to a jury in determining his punishment. Initially, we do not review this claim of prejudice based upon a lapse of fourteen years, as Appellant did not even become a suspect until six years after the commission of the first murder. Further, Appellant has failed to demonstrate any prejudice. His argument in this regard is fully set forth above. Without further development of the argument, this Court is unable to review the claim.

As for Barker's other factors of prejudice, oppressive pretrial incarceration and anxiety and concern of the accused, Appellant makes no argument. However, we note that by 2000, Appellant had discharged the two 25 year sentences received in the Marshall/Hoster cases and was incarcerated solely on the charges in this case. While Appellant suffered some prejudice as a result of the deprivation of his liberty, this is not sufficient to tip the scales in Appellant's favor. The fourth factor weighs in the State's favor.In summary, we find the first and third speedy trial factors weigh in Appellant's favor, but reasons for the delay and prejudice favor the State. After careful consideration, we find Appellant was not deprived of his speedy trial rights under the federal and state constitutions, based upon the finding of reasonable reasons for the delay, the absence of significant prejudice, and the less-than egregious deprivation of liberty.

Appellant further asserts the failure to dismiss his prosecution violated 22 O.S. 1991, § 812 and 22 O.S.Supp. 1999, §§ 812.1 and 812.2. Appellant argues that when charges were refiled in March 1997, he was not brought to trial "at the next term of court" pursuant to 22 O.S. 1991, § 812, the statute in effect at the time. 7 However, as Appellant notes, the prosecution need not be dismissed in such a case when "good cause" has been shown for the delay. As discussed above, the complexities of this case, including the use of DNA analysis, the assigned judge's pending retirement, plus the extraordinarily long preliminary hearing provided sufficient good cause for the delay of the case past the "next term of court." Therefore, the failure to dismiss the prosecution in the fall of 1998 was not a statutory violation. Further, any violation of the 1999 enactment of §§ 812.1 and 812.2 was harmless under the facts of this case. See Simpson v. State, 1994 OK CR 40, P 34, 876 P.2d 690, 701-02. Accordingly, this assignment of error is denied. 8

7 The phrase "term of court" as used in 22 O.S. 1991, § 812 and elsewhere throughout our state laws, i.e. 12 O.S. 1991, §§ 32.1, 55, 663-666, and 1451, refers to statutory provisions setting forth specific time periods during the year in which jury trials could be conducted in courts of this State. See 20 O.S. §§ 92, 95, 96.1, 96.2, 141 - 161. These provisions have been repealed (variously in 1941, 1968 and 1969). As a result, the dates in which court may conducted, and jury trials held, is not restricted by statute but is within the discretion of the District Courts. Therefore, the phrase "term of court" does not have the same meaning in today's judicial system as it once did.

8 Appellant also argues he was denied his rights to be free from the arbitrary imposition of the death penalty under the Eighth Amendment, 21 O.S. 1991, § 701.10, and 21 O.S.Supp. 1985, § 701.13(C). Appellant contends the State relied on first stage evidence obtained in violation of his federal and state constitutional rights to a speedy trial to support the alleged aggravating circumstances. However, this Court has found the first stage evidence was not unconstitutionally obtained. Therefore Appellant's claim is without merit.

In his second assignment of error, Appellant contends the trial court erred in refusing to sever the two murder charges and try him separately for each offense. An objection to the joinder of offenses was filed by the defense on October 25, 2000. On November 6, 2000, the trial court heard argument and denied the motion to sever. Therefore, the issue has been properly preserved for appellate review. Joinder of offenses is permitted pursuant to 22 O.S. 2001, § 438. This section provides that multiple offenses may be combined for trial "if the offenses . . . could have been joined in a single indictment or information." This Court has allowed joinder of separately punishable offenses allegedly committed by the accused if the separate offenses "rise out of one criminal act or transaction, or are part of a series of criminal acts or transactions. Glass v. State, 1985 OK CR 65, P8, 701 P.2d 765, 768. "Further, with respect to a series of criminal acts or transactions, 'joinder of offenses is proper where the counts so joined refer to the same type of offenses occurring over a relatively short period of time, in approximately the same location, and proof as to each transaction overlaps so as to evidence a common scheme or plan.'" Cummings v. State, 1998 OK CR 45, 968 P.2d 821, 829, cert. denied, 526 U.S. 1162, 119 S. Ct. 2054, 144 L. Ed. 2d 220 (1999). See also Glass, 1985 OK CR 65, P8, 701 P.2d at 768.

Appellant admits that the first of the four factors discussed in Glass and Cummings was established, as the charges stemming from the first offense, first degree rape and first degree murder and in the alternative felony murder, were identical to the charges from the second offense. Appellant also states, "it is less clear but still likely that the requirements of proximity in time and space were also satisfied." The record supports Appellant's grudging admission of the satisfaction of the time and space requirements listed as the second and third factors for consideration. Mrs. Fowler and Mrs. Cutler lived across the street from each other and were killed within a four month time period.

Appellant does not concede the fourth factor, that the proof as to each transaction overlaps so as to evidence a common scheme or plan, was established. We disagree. Both crimes were committed against elderly ladies who lived alone. Both victims had friends or family who visited them, but otherwise they had set routines, and rarely left their homes. In contrast to other houses in the neighborhood, the victims' homes and yards were noticeably well taken care of. In each case, entry into the house was made under cover of darkness, either late at night or very early in the morning. Entry in each case was a break-in through a rear door to the residence. In each case, cuts had been made in the rear screen door. Both victims were beaten, raped, and asphyxiated in their beds. A knotted rag was found near each body. In each case, the rapes appeared to be the primary purpose for the break-ins as the houses were not ransacked and nothing of value was taken from the homes. In each instance, Appellant had a relative who lived nearby. This evidence is sufficient to find that proof of each offense overlapped so as to evidence a common scheme or plan, and therefore allow for joinder of the offenses for trial. See Gilson v. State, 2000 OK CR 14, P48, 8 P.3d 883, 904-905, cert. denied, 532 U.S. 962, 121 S. Ct. 1496, 149 L. Ed. 2d 381 (2001). See also Pack v. State, 1991 OK CR 109, P8, 819 P.2d 280, 283.

Further, Appellant has failed to show any prejudice resulting from the joinder. Evidence of either offense would have been admissible in a trial of the other pursuant to 12 O.S. 1991, § 2404(B) as evidence of other crimes or wrongs to prove motive, intent, or common scheme or plan. See Myers v. State, 2000 OK CR 25, P

17 P.3d 1021, 1029-30, cert. denied, 534 U.S. 900, 122 S. Ct. 228, 151 L. Ed. 2d 163 (2001). Accordingly, we find no abuse of discretion by the trial court denying the motion to sever. See Gilson, 2000 OK CR 14, P49, 8 P.3d at 905. This assignment of error is denied.

FIRST STAGE ISSUES

Appellant contends the trial court erred in admitting evidence of the sexual assaults on Mrs. Marshall and Mrs. Hoster. Appellant relies on prior case law from this Court where we have stated that "similarity between crimes, without more, is insufficient to permit admission" of evidence of other crimes. See Hall v. State, 1980 OK CR 64, P5, 615 P.2d 1020, 1022. Prior to trial, the State filed a Notice of Intent to Use Evidence of Other Crimes and Brief in Support. The State alleged the similarities between the Fowler/Cutler homicides and the Marshall/Hoster assaults were "relevant as an aid in determining the identity of the assailant. Also, the evidence is admissible as being part of a common scheme or plan since it demonstrates a highly distinct method of operation." The State cited 37 similarities between the Fowler/Cutler crimes and the Marshall/Hoster crimes. After hearing argument, the trial found the other crimes evidence to be relevant and admissible.

The basic law is well established - when one is put on trial, one is to be convicted - if at all - by evidence which shows one guilty of the offense charged; and proof that one is guilty of other offenses not connected with that for which one is on trial must be excluded. Burks v. State, 1979 OK CR 10, P2, 594 P.2d 771, 772, overruled in part on other grounds, Jones v. State, 1989 OK CR 7, 772 P.2d 922. See also Hall v. State, 1985 OK CR 38, P21, 698 P.2d 33, 37. However, evidence of other crimes is admissible where it tends to establish absence of mistake or accident, common scheme or plan, motive, opportunity, intent, preparation, knowledge and identity. Burks, 1979 OK CR 10, P2, 594 P.2d at 772. To be admissible, evidence of other crimes must be probative of a disputed issue of the crime charged, there must be a visible connection between the crimes, evidence of the other crime(s) must be necessary to support the State's burden of proof, proof of the other crime(s) must be clear and convincing, the probative value of the evidence must outweigh the prejudice to the accused and the trial court must issue contemporaneous and final limiting instructions. Welch v. State, 2000 OK CR 8, P8, 2 P.3d 356, 365, cert. denied, 531 U.S. 1056, 121 S. Ct. 665, 148 L. Ed. 2d 567 (2000).

When other crimes evidence is so prejudicial it denies a defendant his right to be tried only for the offense charged, or where its minimal relevancy suggests the possibility the evidence is being offered to show a defendant is acting in conformity with his true character, the evidence should be suppressed. Id. Where, as here, the claim was properly preserved, the State must show on appeal that admission of this evidence did not result in a miscarriage of justice or constitute a substantial violation of a constitutional or statutory right. Id. at

2 P.3d at 366. This Court has allowed evidence of other crimes or bad acts to be admitted under the "plan" exception of § 2404(B) where the methods of operation were so distinctive as to demonstrate a visible connection between the crimes. Id. at

2 P.3d at 366-67. See also Aylor v. State, 1987 OK CR 190, P5, 742 P.2d 591, 593; Driskell v. State, 1983 OK CR 22, P23, 659 P.2d 343, 349; Driver v. State, 1981 OK CR 117, P5, 634 P.2d 760, 762-63. Distinctive methods of operation are also relevant to prove the identity of the perpetrator of the crime. Eberhart v. State, 1986 OK CR 160, P23, 727 P.2d 1374, 1379-80.

In this case, there is a substantial degree of similarity between the Marshall/Hoster assaults and the Fowler/Cutler homicides. The similarities show a visible connection sufficient to characterize a common scheme and to be probative on the issue of identity of the perpetrator. Briefly summarized, these similarities include: all four victims were white females over the age of 71 who lived alone; all four victims lived on the south side of the street and on corner lots; the back porch screen door was cut on the homes of three of the victims; the breaker box for the electricity to the residence was shut off in the homes of three of the four victims; entry to the residence was gained through a rear door in all four homes; a back door window was broken in three of the homes; two of the victims were awake when their homes was broken into and they were forced to their bedrooms; all four victims were raped vaginally while in their bedrooms; two of the four victims were also anally raped; all four victims were raped either late at night or in the early morning; all four victims were beaten about the head, face and arms; all four victims suffered vaginal tears and bleeding; a knotted rag was found on the beds of three of the victims; a pillow was placed over the faces of three of the victims during the assault; none of the residences occupied by the four victims were ransacked and nothing of any significant value was taken from any of the homes; all four assaults occurred within an eight month time period with the Fowler/Cutler crimes occurring four months apart and the Marshall/Hoster crimes occurring two months apart; all four victims lived within three miles of each other; Appellant lived with his mother or sister near the Fowler/Cutler homes at the time of their murders and he lived with his brother near the Marshall/Hoster homes at the time of their assaults.

Appellant contends there were just as many differences as there were similarities between the crimes. Chief among those differences is the fact that two of the victims were left alive while two were killed. Appellant argues that at the time these four crimes occurred, numerous instances of rapes and home invasions of elderly women were being reported in the media. Appellant asserts the crimes in this case were not unusual enough to point to a signature of one individual perpetrator. We disagree. The similarities in this case are far greater than those in Hall v. State, 1980 OK CR 64, P6, 615 P.2d at 1022 relied upon by Appellant (similarities limited to each rape took place in an automobile, all three victims were under the age of consent, and each rape was committed in Tulsa County). Further, the similarities between the Fowler/Cutler homicides and the Marshall/Hoster assaults show a method of operation so distinctive as to demonstrate a visible connection between the crimes. In crimes involving sexual assaults, this Court has adopted a greater latitude rule for the admission of other crimes. Myers, 2000 OK CR 25, PP21- 24, 17 P.3d 1021 at 1030. See also Driskell, 659 P.2d at 349. 9

9 Even before Myers, this Court in Driskell, 659 P.2d at 349 cited to Rhine v. State, 1958 OK CR 110, P20, 336 P.2d 913 (Okl.Cr. 1958) and stated:

'That evidence of the commission of other similar crimes may be given to show the plan or design on the part of the defendant to commit such crimes has often been judicially recognized. The word 'design' implies a plan formed in the mind. That an individual who commits or attempts to commit abnormal sex offenses is likely to have such a mental 'plan' finds recognition in the fact that when a defendant is charged with the commission of sexual offense the law is more liberal in admitting as proof of his guilt evidence of similar sexual offenses committed by him than it is in admitting evidence of similar offenses when a defendant is charged with the commission of non-sexual crimes…. 'But where the prior rape or attempt is committed under circumstances remarkably similar to the one charged the evidence is admissible to show a plan or scheme to commit the crime in that fashion, even though the prior rape or attempt was committed on a person other than the prosecutrix. In such cases the evidence that defendant committed the prior offense tends to prove that he committed the offense charged.' 659 P.2d at 349.

We further uphold the trial court's ruling that the probative value of the evidence of the Marshall/Hoster assaults outweighed its prejudicial impact. See Mayes v. State, 1994 OK CR 44, P77, 887 P.2d 1288, 1309-10, cert. denied, 513 U.S. 1194, 115 S. Ct. 1260, 131 L. Ed. 2d 140 (1995). The evidence was necessary to support the State's burden of proof despite its prejudicial nature. Finding the evidence properly admitted, this proposition is denied.

FIRST STAGE JURY INSTRUCTIONS

In his fourth assignment of error, Appellant contends the trial court erred by instructing the jury on aiding and abetting. We review only for plain error as no objection was raised to the instruction. Bland v. State, 2000 OK CR 11, P49, 4 P.3d 702, 718, cert. denied, 531 U.S. 1099, 121 S. Ct. 832, 148 L. Ed. 2d 714 (2001). In support of his contention, Appellant relies on Lambert v. State, 1994 OK CR 79, 888 P.2d 494. In Lambert, the defendant was charged with malice aforethought murder. The trial court gave instructions on felony murder. The appellant argued he was not given sufficient notice of this theory in the information, and this Court reversed on this basis. 1994 OK CR 79, PP45 - 48, 888 P.2d 494 at 504. The situation in the present case is very different.

In a Fourth Amended Felony Information, filed approximately one year before trial, Appellant was charged with two counts of first degree malice aforethought murder for the deaths of Mrs. Fowler and Mrs. Cutler. In the alternative, he was charged with two counts of felony murder by aiding and abetting Robert Lee Miller, Jr., who in the commission of first degree burglary and first degree rape killed the victims. (O.R. 734-735). The State's theory throughout the proceedings was that Appellant committed the rapes, and that Appellant either killed the victims himself or he aided and abetted Miller in killing the victims. Unlike Lambert, Appellant was given plenty of notice concerning the State's alternative theories of guilt.

Further, the aiding and abetting instructions were warranted by the evidence. The State's evidence included the results of DNA testing showing Appellant was the donor of the semen found at the crime scenes, and that Miller had been excluded as the semen donor. The State also presented evidence showing Appellant had pled guilty to committing two other rapes under very similar circumstances as the charges on trial. During the cross-examination of several of the State's witnesses, the defense established that Miller had made certain statements about the Fowler/Cutler crimes which were not known to the general public, and that based in part upon those statements, Miller had been previously convicted of committing the Fowler/Cutler homicides. During re-direct examinations, the State elicited testimony that it was possible there were two intruders into the homes of Mrs. Fowler and Mrs. Cutler and that it was possible that one intruder killed the victims while the other watched. Additionally, during its case-in-chief, the defense introduced evidence concerning Miller's prior prosecution in the Fowler/Cutler cases. Accordingly, the trial court did not abuse its discretion in giving the instructions on aiding and abetting instructions. See Cannon v. State, 1995 OK CR 45, P25, 904 P.2d 89, 99. See also Slaughter v. State, 1997 OK CR 78, P63, 950 P.2d 839, 857 n. 9., cert. denied, 525 U.S. 886, 119 S. Ct. 199, 142 L. Ed. 2d 163 (1998).

Appellant further argues defense counsel was ineffective as counsel admitted guilt as to the felony murder charge without Appellant's consent. This Court follows the test for ineffective assistance of counsel set forth in Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 687, 104 S. Ct. 2052, 2064, 80 L. Ed. 2d 674 (1984). See Bland, 2000 OK CR 11, 4 P.3d at 730. Under Strickland's two-part test, the appellant must overcome the strong presumption that counsel's conduct falls within the wide range of reasonable professional assistance by showing: [1] that trial counsel's performance was deficient; and [2] that he was prejudiced by the deficient performance. Unless the appellant makes both showings, "it cannot be said that the conviction … resulted from a breakdown in the adversary process that renders the result unreliable." Strickland, 466 U.S. at 687, 104 S. Ct. at 2064. Appellant must demonstrate that counsel's representation was unreasonable under prevailing professional norms and that the challenged action could not be considered sound trial strategy. Id. at 688-89, 104 S. Ct. at 2065. The burden rests with Appellant to show that there is a reasonable probability that, but for any unprofessional errors by counsel, the result of the proceeding would have been different. A reasonable probability is a probability sufficient to undermine confidence in the outcome. Id., 466 U.S. at 698, 104 S. Ct. at 2070. When a claim of ineffectiveness of counsel can be disposed of on the ground of lack of prejudice, that course should be followed. Id. at 697, 104 S. Ct. at 2069. This Court has stated the issue is whether counsel exercised the skill, judgment and diligence of a reasonably competent defense attorney in light of his overall performance. Bland, 2000 OK CR 11, 4 P.3d at 731.

Appellant relies on Jackson v. State, 2001 OK CR 37, 41 P.3d 395, 398-399, where this Court reiterated its position that a concession of guilt does not amount to ineffective assistance of counsel, per se. The Court stated, "a complete concession of guilt is a serious strategic decision that must only be made after consulting with the client and after receiving the client's consent or acquiescence." Id. at P25, 41 P. 3d at 400. This Court placed the burden on the appellant to show that he was not consulted and that he did not agree to or acquiesce in the concession strategy. Id. Under the facts of the present case, and when all of the arguments are read in context, it is clear that guilt was not conceded. The defense was well aware from early on that the State had DNA evidence which conclusively placed Appellant at the scene. The defense filed numerous pre-trial motions challenging that evidence. To counter the State's evidence at trial, the defense showed that the scientific evidence relied upon 14 years ago to convict Robert Miller of the Fowler/Cutler crimes - hair and blood analysis - had since been proven unreliable. Defense counsel questioned whether DNA analysis might not also go the way of hair and blood analysis in light of future advances in forensic testing. Counsel also argued that all the State had to prove Appellant's guilt was DNA and that relying on DNA was like gambling and relying on mere probabilities. Defense counsel urged the jury not to let the State's experts decide the case for them. The defense also presented evidence showing Miller's involvement in the Fowler/Cutler crimes and his knowledge of details that only someone present at the crime scenes would have known. Defense counsel argued in closing argument that the evidence showed Miller wasn't a mere observer to the crimes, but the actual perpetrator of the crimes.

Defense counsel also challenged the State's alternative theories of guilt and argued the State could not assert that Miller was and was not the killer. Defense counsel argued that while Miller was in jail for the Fowler/Cutler crimes, other rape victims did not die. Defense counsel stated that when the State told the jury they had no evidence Miller was the killer, "that cuts both ways because they also have no evidence what Ronald Lott was. None." Counsel then stated, "I don't know what you're going to do with that DNA, but at worst they have proven that Ronald Lott was the rapist . . ." Defense counsel further argued that merely because Miller was not included as a donor of the semen found at the scene, that did not mean that he was not a rapist and a killer. Counsel argued it merely showed Miller did not ejaculate at the scene. Counsel concluded his closing argument by asserting the State had not proven that Miller was not the killer, and because of that reasonable doubt as to Appellant's guilt existed.