Executed April 30, 2014 07:06 p.m. CDT by Lethal Injection in Oklahoma

20th murderer executed in U.S. in 2014

1379th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

3rd murderer executed in Oklahoma in 2014

110th murderer executed in Oklahoma since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(20) |

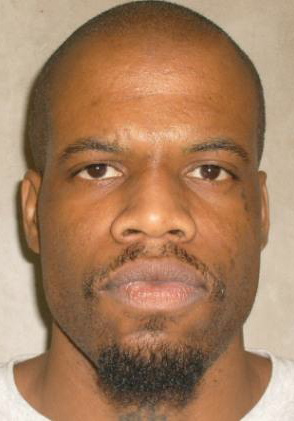

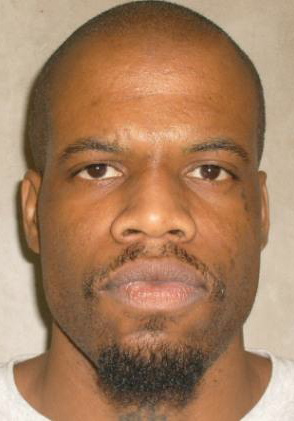

Clayton Derrell Lockett B / M / 23 - 38 |

Stephanie Michelle Neiman W / F / 19 |

Clayton Lockett instructed Mathis to dig a grave and said :"Someone has got to go.” Neiman was taken to the hole dug by Mathis. When she refused to promise that she would not go to the police, Clayton Lockett shot her. The gun jammed, but he fixed it, returned and shot her again. While Mathis buried Neiman, Bornt and Hair were warned that if they told anyone they would be killed too. They then drove both pickups and dropped off Bornt, his son and Hair at Bornt's house and they left in Bornt's pickup. The following day, Bornt and Hair told the Perry police what had happened. Neiman's pickup and her body were recovered and all three men were subsequently arrested. Clayton Lockett ultimately confessed to police.

Citations:

Lockett v. State, 53 P.3d 418 (Okla. Crim. App. 2002). (Direct Appeal)

Lockett v. Trammel, 711 F.3d 1218 (10th Cir. Okla. 2013). (Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

Lockett rejected his last meal after being told he could not have a particular kind of steak.

Final Words:

None.

Internet Sources:

Oklahoma Department of Corrections

CLAYTON D LOCKETTCRF# County Offense Conviction Term Term Code Start End

92-188 KAY Unauthorized Use Of Motor Vehicle N 05/14/1992 5Y 0M 0D Incarceration 11/19/1992 09/10/1996

92-188 KAY Unauthorized Use Of Motor Vehicle N 05/14/1992 5Y 0M 0D Incarceration 11/19/1992 09/10/1996

92-188 KAY Unauthorized Use Of Motor Vehicle N 05/14/1992 5Y 0M 0D Incarceration 11/19/1992 09/10/1996

92-188 KAY Unauthorized Use Of A Vehicle 05/14/1992 3Y 0M 0D Probation 05/14/1992 05/13/1995

92-287 KAY Burglary In The Second Degree 09/02/1992 0 Y Incarceration 09/08/1992 09/07/1992

92-287 KAY Burglary In The Second Degree 09/02/1992 7Y 0M 0D Incarceration 11/19/1992 12/20/1997

92-287 KAY Knowingly Concealing Stolen Property N 09/02/1992 5Y 0M 0D Incarceration 11/19/1992 09/10/1996

92-315 KAY Intimidation Of State Witness N 11/19/1992 5Y 0M 0D Incarceration 11/19/1992 09/10/1996

92-315 KAY Intimidation Of State Witness N 11/19/1992 5Y 0M 0D Incarceration 11/19/1992 09/10/1996

96-234 GRAD Conspiracy To Commit A Felony 08/19/1996 4Y 0M 0D Incarceration 09/11/1996 01/04/1999

96-234 GRAD Conspiracy To Commit A Felony 08/19/1996 6Y 0M 0D Probation 08/19/1996 08/18/2006

96-234 GRAD Conspiracy To Commit A Felony 08/19/1996 2.16 Y SUSPENDED 09/11/1996 11/09/1998

99-53A NOBL Conspiracy Afc4f 10/05/2000 45Y Incarceration

99-53A NOBL Forcible Oral Sodomy Afc4f 10/05/2000 150Y Incarceration

99-53A NOBL Forcible Oral Sodomy Afc4f 10/05/2000 150Y Incarceration

99-53A NOBL Forcible Oral Sodomy Afc4f 10/05/2000 300Y Incarceration

99-53A NOBL Robbery By Force And Fear Afc4f 10/05/2000 85Y Incarceration

99-53A NOBL Robbery With A Firearm Afc4f 10/05/2000 85Y Incarceration

99-53A NOBL Assault With A Dangerous Weapon Afc4f 10/05/2000 75Y Incarceration

99-53A NOBL Assault With A Dangerous Weapon Afc4f 10/05/2000 60Y Incarceration

99-53A NOBL Assault And Battery Afc4f 10/05/2000 90D Incarceration

99-53A NOBL Rape, First Degree Afc4f 10/05/2000 250Y Incarceration

99-53A NOBL Rape, First Degree Afc4f 10/05/2000 200Y Incarceration

99-53A NOBL Rape, Firist Degree Afc4f 10/05/2000 250Y Incarceration

99-53A NOBL Rape, First Degree Afc4f 10/05/2000 175Y Incarceration

99-53A NOBL Murder First Degree Afc4f 10/05/2000 DEATH Death 10/09/2000

99-53A NOBL Kidnapping Afc4f 10/05/2000 100Y Incarceration

99-53A NOBL Kidnapping Afc4f 10/05/2000 100Y Incarceration

99-53A NOBL Kidnapping Afc4f 10/05/2000 100Y Incarceration

99-53A NOBL Kidnapping Afc4f 10/05/2000 100Y Incarceration

99-53A NOBL First Degree Burglary Afc4f 10/05/2000 60Y Incarceration

Death Penalty Information

The current death penalty law was enacted in 1977 by the Oklahoma Legislature. The method to carry out the execution is by lethal injection. The original death penalty law in Oklahoma called for executions to be carried out by electrocution. In 1972 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional the death penalty as it was then administered.

Oklahoma has executed a total of 190 men and 3 women between 1915 and 2014 at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary. Eighty-two were executed by electrocution, one by hanging (a federal prisoner) and 110 by lethal injection. The last execution by electrocution took place in 1966. The first execution by lethal injection in Oklahoma occurred on September 10, 1990, when Charles Troy Coleman, convicted in 1979 of Murder 1st Degree in Muskogee County was executed.

Method of Execution: Lethal Injection

Drugs used: Midazolam - causes unconsciousness; Vecuronium Bromide - stops respiration: Potassium Chloride - stops heart. Two intravenous lines are inserted, one in each arm. The drugs are injected by hand held syringes simultaneously into the two intravenous lines. The sequence is in the order that the drugs are listed above. Three executioners are utilized, with each one injecting one of the drugs.

Brief in Opposition to Clemency Petition of Clayton Lockett (33 pages)

“In reality I am probably the most dangerous type of criminal . . . ‘cause I’m an assassin - point blank!”

AG's Statement on Execution Review

Wednesday, April 30, 2014

“It is important to review the events surrounding the execution of Clayton Lockett to ascertain what transpired and to ensure the death penalty is administered correctly. It’s equally important that any such review be conducted with a commitment to objectivity. Transparency and impartiality in the fact-finding surrounding this execution will give Oklahomans confidence and lend credibility to the state’s most solemn of duties: carrying out the sentence of death.

As the state’s chief legal officer, and to ensure the fair administration of justice, I am taking the following actions: • Assigning investigators from the Attorney General’s Office to work with DPS Commissioner Michael Thompson as he gathers information on the execution of Lockett; • Designating a special advisor(s) to assess the results of the review of Lockett’s execution, and Department of Corrections’ procedures, and then to recommend, if necessary, any changes surrounding such issues; • Instructing my staff to work with lawmakers on any relevant legislative proposals emanating from the review; • Ensuring victims’ concerns in the process are addressed.

Integrity and fairness are core values of Oklahomans, and my office is committed to upholding those values as we conduct this review.” – Attorney General Scott Pruitt

"Oklahoma prison report says collapsed vein botched execution," by Heide Brandes. (May 1, 2014 5:56pm)

OKLAHOMA CITY (Reuters) - The botched Oklahoma execution of Clayton Lockett was largely due to a collapsed vein during the lethal injection, and the needle was inserted in the groin area instead of the arm after prison officials used a stun gun to restrain him, a prisons report said on Thursday. Department of Corrections Director Robert Patton said in the report the state's execution protocols needed to be revised and called for an indefinite stay of executions until the new procedures are in place and staff trained.

Ahead of the Tuesday execution, Lockett, a convicted murderer, had refused to be restrained, the report said, and after being given a warning "an electronic shock device was administered," causing an injury to his arm. The state has come under a barrage of criticism for the botched execution that many saw as a violation of constitutional protections against cruel and unusual punishment. The White House said the process fell short of humane standards.

Lockett, 38, died of an apparent heart attack minutes after the lethal injection protocol failed. He was convicted of shooting 19-year-old Stephanie Nieman in 1999 and then helping to bury her alive in a shallow grave, where she died.

Witnesses to the execution said Lockett clenched his jaw and fists a few minutes after the drugs were injected and appeared to be in pain. Prison officials covered the windows to the death chamber soon after as it became apparent there was trouble. The doctor overseeing the execution reported that Lockett's vein had collapsed during the injection and the drugs had either absorbed into the tissue, or leaked out or both, Patton said.

Patton asked if enough drugs had been administered to cause death, and the doctor answered "no." Patton then asked if another vein was available and if enough drugs remained to finish the execution. The doctor responded "no" to both questions. Once the problem became apparent, Patton halted the execution. Lockett died 43 minutes after the execution started, and an autopsy was under way. "I intend to explore best practices from other states and ensure the Oklahoma protocol adopts proven standards," Patton said in his report.

Patton said in the report that medical officials examined Lockett's arms, legs, feet and neck for veins, but no viable entry point was located. After that, a lethal injection insertion point was used in Lockett's groin area. "As the Oklahoma Department of Corrections dribbles out piecemeal information about Clayton Lockett's botched execution, they have revealed that Mr. Lockett was killed using an invasive and painful method - an IV line in his groin," said Madeline Cohen, a lawyer who fought to halt the execution of another Oklahoma death row inmate.

That inmate, convicted murderer and rapist Charles Warner, had also been also scheduled for execution on Tuesday night, but was granted a 14-day stay after the botched execution of Lockett. The executions of Lockett and Warner, convicted in separate crimes, had been put on hold for several weeks because of a legal fight over the state's new lethal injection cocktail, with lawyers arguing Oklahoma was withholding crucial information about the drugs to be used.

Attorneys for death row inmates have argued that the drugs used in Oklahoma and other states could cause an unnecessarily painful death, in violation of the U.S. Constitution. (Writing by Jon Herskovitz; Editing by Cynthia Johnston and Mohammad Zargham)

"Obama to have attorney general look into botched Oklahoma execution," by Bill Trott. (May 2, 2014 5:26pm EDT)

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - President Barack Obama on Friday said the botched execution of a murderer in Oklahoma raises questions about the death penalty in the United States and he will ask the U.S. attorney general to look into the situation. "What happened in Oklahoma is deeply troubling," he said.

The condemned man, Clayton Lockett, 38, who was convicted of murder, rape, kidnapping and robbery in a 1999 crime spree, died of an apparent heart attack minutes after the lethal injection protocol failed. A prison report said the problem was largely due to a collapsed vein during the injection of the lethal drugs and that the needle was inserted in Lockett's groin instead of his arm. Oklahoma's director of corrections called for a revision of the state's execution methods and a suspension of executions until new procedures are in place.

Obama cited uneven application of the death penalty in the United States, including racial bias and cases in which murder convictions were later overturned, as grounds for further study of the issue. "And this situation in Oklahoma just highlights some of the significant problems," he said at a news conference. "I'll be discussing with (Attorney General) Eric Holder and others to get me an analysis of what steps have been taken - not just in this particular instance but more broadly - in this area," he said. "I think we do have to, as a society, ask ourselves some difficult and profound questions around these issues."

Oklahoma has sent Lockett's body to the Dallas County Medical Examiner's office for a complete post mortem examination, officials in the state said. It was also testing a batch of drugs that was to be used in a second execution planned to come just after Lockett was put to death on Tuesday. The second inmate, convicted rapist and murderer Charles Warner, was granted a temporary stay due to problems with Lockett's execution. (Writing by Bill Trott; Additional reporting by Heide Brandes in Oklahoma City; Editing by Tom Brown)

Oklahoma Coalition to Abolish Death Penalty

"Eyewitness account: A minute-by-minute look at what happened during Clayton Lockett’s execution," by Ziva Branstetter. (Thursday, May 1, 2014 12:00 am)

Tulsa World Enterprise Editor Ziva Branstetter was one of 12 media witnesses to attend a botched execution Tuesday at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary. Here is her account of what happened Tuesday in McAlester:

5:30 p.m. Reporters are taken in two white vans to the prison’s death row, called the H unit, to attend the execution. Media witnesses can take nothing with them into death row, not even a watch, and are issued a spiral notebook and pen after being searched by correctional officers. We are taken to the death row law library where we wait with two prison officials to be taken to the execution viewing chamber.

5:40 p.m. Inmates can be heard banging loudly on cell doors throughout death row, which prison officials explain is a sign of respect for the inmate to be executed. Not all inmates receive such a sendoff; it just depends on whether other inmates liked the condemned inmate.

5:50 p.m. We are taken from the law library down a long sterile hall, around a corner and into the viewing chamber. Media witnesses file into the back row of two rows of metal folding chairs. Before the execution starts, witnesses for the crime victim, Stephanie Neiman, file into a separate viewing room for victims’ relatives so they can watch the process through one-way glass. Two attorneys for inmate Clayton Lockett, his only witnesses, sit in front of us. Department of Public Safety Commissioner Michael Thompson, Department of Corrections Director Robert Patton and several other state officials also file in, sitting in the front row.

6:23 p.m. The beige blinds covering four windows into the execution chamber are raised and the execution is set to begin – 23 minutes past its scheduled time. This execution has taken longer to start than the three others I have covered and other media witnesses remark on the slow start as well. Oklahoma State Penitentiary Warden Anita Trammell asks Lockett, covered up to his shoulders by a white sheet, whether he has any last words. “No,” is all he says. This isn’t especially surprising. Earlier, Lockett rejected his last meal after being told he couldn’t have a particular kind of steak. “Let the execution begin,” Trammell says. Inside the room are four other people, including a physician and a uniformed correctional officer.

6:28 p.m. Fifty milligrams of midazolam have been injected into each of Lockett’s arms to start the process, an attempt to sedate him before the second and third drugs are administered to stop the breathing and the heart. Lockett has spent the past several minutes blinking and occasionally pursing his lips.

6:29 p.m. Lockett’s eyes are closed and his mouth is open slightly.

6:31 p.m. The doctor checks Lockett’s pupils and places his hand on the inmate’s chest, shaking him slightly. “Mr. Lockett is not unconscious,” Trammell states.

6:33 p.m. The doctor checks Lockett a second time after a full minute without movement. “Mr. Lockett is unconscious,” Trammell states. It seems like it took longer than expected for this to occur. In past executions I have attended, there has been no notice that the inmate was unconscious, just a pronouncement of death after about eight minutes without much reaction from the inmate.

6:36 p.m. Lockett kicks his right leg and his head rolls to the side. He mumbles something we can’t understand.

6:37 p.m. The inmate’s body starts writhing and bucking and it looks like he’s trying to get up. Both arms are strapped down and several straps secure his body to the gurney. He utters another unintelligible statement. Defense Attorney Dean Sanderford is quietly crying in the observation area.

6:38 p.m. Lockett is grimacing, grunting and lifting his head and shoulders entirely up from the gurney. He begins rolling his head from side to side. He again mumbles something we can’t understand, except for the word “man.” He lifts his head and shoulders off the gurney several times, as if he’s trying to sit up. He appears to be in pain.

6:39 p.m. The physician walks around to Lockett’s right arm, lifts up the sheet and says something to Trammell. “We’re going to lower the blinds temporarily,” she says. The blinds are lowered and we can’t see what is happening. Reporters exchange shocked glances. Nothing like this has happened at an execution any of us has witnessed since 1990, when the state resumed executions using lethal injection.

6:40 p.m. A black landline phone rings in the viewing chamber and Patton leaves to take the call, stretching the phone cord out into the hall and closing the door behind him. Though the clock on the wall in the execution chamber is no longer visible, it seems like several minutes pass before Thompson is summoned out to the hallway.

Approximately 6:50 p.m. Patton comes back to the viewing room and says the execution has been “stopped. We’ve had a vein failure in which the chemicals did not make it into the offender. … Under my authority, we are issuing a stay for the second execution.” The announcement is stunning and leaves us wondering what has happened to Lockett. Patton leaves for about 10 more minutes and reporters at the end of our row begin interviewing Sanderford and defense attorney David Autry, both clearly upset by the turn of events. “They will save him so they can kill him another day,” Autry says. We are told to leave the viewing chamber and are escorted back to a waiting white prison van. We have to tear the notes out of the spiral notebook and leave it plus the pen behind. Another van is on the way so I stay behind with reporters from the Associated Press, The Oklahoman, OETA and The Guardian to compare notes. After every execution, it’s important that reporters compare last words and other observations to make sure they have the most accurate version of events possible.

7:06 p.m. Lockett is pronounced dead in the execution chamber from a heart attack. The news of his death is provided to reporters by Patton during a brief statement at the media center on the prison grounds. He explains to reporters that prison officials do not know how much of the second and third drugs entered Lockett’s body. “His line failed,” Patton says. When asked what that means, Patton adds: “His vein exploded.”

"Oklahoma execution: Clayton Lockett writhes on gurney in botched procedure," by Katie Fretland. (30 April 2014)

• State calls off second execution after failure of first

• Heart attack kills Lockett 43 minutes after drugs injected

• Untested cocktail of drugs used in botched execution

• Eyewitness account of Clayton Lockett execution

The state of Oklahoma botched one execution and was forced to call off another on Tuesday when a disputed cocktail of drugs failed to kill a condemned prisoner who was left writhing on the gurney. After the failure of a 20-minute attempt to execute him, Clayton Lockett was left to die of a heart attack in the execution chamber at the Oklahoma state penitentiary in McAlester. A lawyer said Lockett had effectively been "tortured to death".

For three minutes after the first drugs were delivered Lockett struggled violently, groaned and writhed, lifting his shoulders and head from the gurney. Some 16 minutes after the execution began, and without Lockett being declared dead, the blinds separating the chamber from the viewing room were closed. The process was called off shortly afterwards. Lockett died 43 minutes after the first executions drugs were adminsitered. The execution of Charles Warner, scheduled for 8pm local time, was then postponed. Both were due to have been carried out with a drug cocktail using dosages never before tried in American executions. Lockett, 38, was convicted of the killing of 19-year-old, Stephanie Neiman, in 1999. She was shot and buried alive. Lockett was also convicted of raping her friend in the violent home invasion that lead to Neiman's death.

Warner, 46, was found guilty of raping and killing 11-month-old Adrianna Waller in 1997. He lived with the child's mother. Death penalty states have scrambled to find new execution methods after drugs companies opposed to capital punishment, mostly based in Europe, withdrew their supplies. Oklahoma decided to lethally inject Lockett and Warner with midazolam ,which acts as a sedative and is also used as an anti-seizure drug, followed by vecuronium bromide and potassium chloride. Florida has used a similar method but it employed a dose of midazolam five times greater. Ohio used midazolam alongside a different drug, hydromorphone, in the January execution of Dennis McGuire, which took more than 20 minutes. The grim outcome on Tuesday in Oklahoma appeared likely to fuel the debate over the death penalty in the US, in particular the use of these untested drugs combinations.

Madeline Cohen, an attorney for Warner, condemned the way Lockett was killed. "After weeks of Oklahoma refusing to disclose basic information about the drugs for tonight's lethal injection procedures, tonight Clayton Lockett was tortured to death," she said. Richard Dieter, the executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, which monitors capital punishment, said: "This could be a real turning point in the whole debate as people get disgusted by this sort of thing. "This might lead to a halt in executions until states can prove they can do it without problems. Someone was killed tonight by incompetence," he told the Associated Press. Before the attempted executions in Oklahoma, corrections spokesman Jerry Massie said they would probably take longer than normal because the first drug was expected to work more slowly. "Don't be surprised," Massie said.

The Guardian watched as Lockett was asked if he had final words. He said "no." He lay covered in a white sheet when the execution began at 6.23pm. At 6.30pm he was found to be still conscious. Lockett was then pronounced unconscious at 6.33pm but his violent struggle began three minutes later. He tried to speak and was heard to say "man" at 6.39pm. An official in the execution room then lowered the blinds so viewers could no longer witness the process.

Robert Patton, the director of Oklahoma's department of corrections, said later that when doctors felt that the drugs were not having the required effect on Lockett, they discovered that a vein had ruptured. "After conferring with the warden, and unknown how much drugs went into him, it was my decision at that time to stop the execution," Patton told reporters. Massie said that all three drugs in the cocktail used by the state were administered, but that a vein "blew" during the execution process and Lockett later suffered a heart attack. He was pronounced dead at 7.06pm, 43 minutes after the process began. The execution of Charles Warner was postponed for 14 days.

The double executions were scheduled after an unprecedented legal and political dispute in Oklahoma. The inmates challenged the secrecy surrounding Oklahoma's source of lethal injection drugs, winning at the state district court level, but two higher courts argued over which could grant a stay of execution. When the state supreme court stayed their executions so that it could consider their constitutional claim, the Republican governor, Mary Fallin, declared in a controversial statement that it had no authority to grant the stay. A member of the Oklahoma House of Representatives said he would try to have the justices who wanted the stay impeached. Amid accusations of undue political pressure, the court then ruled against the prisoners and lifted the stay.

On Tuesday night Fallin said she had directed her officials to conduct an investigation. "I have asked the department of corrections to conduct a full review of Oklahoma's execution procedures to determine what happened, and why, during this evening's execution of Clayton Derrell Lockett," she said in a statement. "I have issued an executive order delaying the execution of Charles Frederick Warner for 14 days to allow for that review to be completed."

Susanna Gattoni and Seth Day, attorneys for Lockett and Warner, said Lockett's execution demonstrated the harm caused by secrecy surrounding the drugs used in the attempted executions. "This is exactly why we fought so hard to get this information known not just for our clients but for everyone," said Gattoni. " This shouldn't be kept secret. This is unfortunately what happens." "There will be a next step," Day said. "Whatever it is there will be a next step." Cohen, Warner's attorney, said no executions should proceed in Oklahoma in light of Lockett's execution. "My feeling about this is there can be no more executions in Oklahoma until there is a full investigation into what went wrong, an autopsy by an independent pathologist and full transparency about this process including the drugs," Cohen said.

"Officials refuse to say if they tried to revive Clayton Lockett," by Ziva Branstetter. (May 1, 2014 12:00 am)

Inmate Clayton Lockett spent three minutes writhing in pain at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary before prison officials said they had halted his execution. Shades were drawn in the execution chamber 16 minutes after the execution began, preventing media witnesses from seeing what happened to Lockett, 38. Department of Corrections Director Robert Patton later said Lockett had been pronounced dead of a heart attack at 7:06 p.m., a total of 43 minutes after the execution began.

Lockett was injected with midazolam, a sedative, and then was supposed to be injected with vecuronium bromide, a paralytic drug intended to stop the breathing; and potassium chloride, a drug intended to stop the heart. It is unclear how much of the drugs were administered, DOC officials said. Alex Weintz, a spokesman for Gov. Mary Fallin, referred questions to DOC about what happened to Lockett before his death. A spokesman said the agency would not comment on the execution or make a statement Wednesday. Officials said previously that Lockett died on the gurney and was not removed from the execution chamber before his death.

Records show DOC's new execution protocol, approved April 14, lists no policies for such situations. It allows the prison to choose from five drug combinations, including the untested combination used Tuesday. A physician in the execution chamber declared Lockett unconscious. DOC officials cited the state's execution secrecy law in refusing to identify the doctor. David Autry, one of two defense attorneys for Lockett who witnessed the execution, told the World: "This was obviously a botched execution. ... For them to claim that he was sedated appropriately and adequately is ridiculous."

Autry said he is unaware of what happened to Lockett after the blinds were drawn. "All I know is Director (Robert) Patton came in and said he was halting the execution," he said. "I assumed that they were going to try to revive him. What efforts if any they made to revive him or try to counteract the drugs, I don't know." Autry questioned DOC's statement that Lockett's vein had collapsed, preventing full administration of the drugs. "I'm not a medical professional, but Mr. Lockett was not someone who had compromised veins," Autry said. "He was in very good shape. He had large arms and very prominent veins." Autry said the state's pledge to investigate the botched execution before Warner's death "is not going to cut it."

"They are going down the same path they've gone down before trying to get this done at all costs regardless," he said. "... That's going to be a whitewash. They are going to paper over this." A medical expert who has testified in death penalty cases said, based on witness accounts, Lockett was conscious and experienced a painful execution. Dr. David Waisel, associate professor of anesthesiology at Harvard Medical School, said midazolam is typically given in small doses to patients before surgery. Waisel, who has testified or consulted in about eight death penalty cases, said he is not aware of another execution using the same three-drug combination used by Oklahoma on Tuesday.

After conferring with the physician, OSP Warden Anita Trammell declared Lockett was unconscious at 6:33 p.m., 10 minutes after the procedure began. Less than five minutes later, a World reporter and other witnesses to the execution saw Lockett convulsing and writhing, apparently in pain. He tried to speak, although what he said was not clear. Waisel said people who are unconscious are not capable of speaking and bodily movements. Waisel said given the timeline and drugs used, "it is possible that he received enough midazolam to make him sleepy, but not the full intended dose." He said if the second and third drugs were administered directly to Lockett's blood stream through a vein "he would have died right away." "What I suspect happened was that the two drugs were not injected into the vein, but were injected in the soft tissue around the vein," he said. "That can be very painful, and would be consistent with the reaction being reported."

Waisel said because so many minutes had elapsed between administering of the midazolam and Lockett's violent reaction, "clearly this sounds like a new injection of something that was very painful." Attorney General Scott Pruitt's office said in a statement Tuesday that an expert witness had testified in court cases to the safety of midazolam used in Florida executions. Pruitt's statement cited court testimony by Dr. Mark Dershwitz, professor of anesthesiology at the University of Massachusetts, that "a 50 mg dose prevented his patients from perceiving the noxious stimuli associated with neurosurgery."

"The state is using twice as much midazolam (100 mg) in the executions of Lockett and Warner," Pruitt's statement says. However, Florida uses 500 milligrams of midazolam in its executions, records show.

Three-drug protocol

1. Oklahoma's execution protocol allows officials to choose from five drug combinations. The state chose the fifth option for the scheduled executions of two inmates Tuesday night. Here are the three drugs chosen by the state.

1. Midazolam: A sedative, 50 milligrams in each arm.

2. Vecuronium bromide: Paralytic drug intended to stop breathing, 20 milligrams in each arm. The drug "will not be administered until at least 5 minutes after the beginning of the administration of the midazolam."

3. Potassium chloride: A drug intended to stop the heart, 50 cc in each arm.

"Clayton Lockett's mother demands thorough investigation, expresses sorrow for her son's victim," by Zita Branstetter. (Thursday, May 1, 2014 12:00 am)

The morning after convicted killer Clayton Lockett died of a heart attack after his execution went awry, his mother expressed sorrow for Lockett's victim and demanded answers for what went wrong Tuesday in McAlester. Lockett's mother, Ladonna Hollins, told the Tulsa World Wednesday she expected a complete investigation from the state about how her son died. "He was in pain and in our Constitution it clearly states that we should not make a man suffer like this so I’m torn. My heart aches that he had to suffer like that. … Stephanie suffered I’m sure but now here’s the end result. They are both dead now. She’s not any more alive than she was the day before," said Hollins, of Oklahoma City. "My heart bleeds as well as Mrs. Neiman's heart bleeds."

Lockett, 38, was convicted in the 1999 murder of Stephanie Neiman, 19, of Perry. Tuesday night, Gov. Mary Fallin issued a statement saying she had issued an executive order delaying the execution of convicted killer Charles Warner. “I have asked the Department of Corrections to conduct a full review of Oklahoma’s execution procedures to determine what happened and why during this evening’s execution of Clayton Derrell Lockett,” Fallin said in the statement. “I have issued an executive order delaying the execution of Charles Frederick Warner for 14 days to allow for that review to be completed.”

Hollins awaits the results of that investigation. "The reason for the drugs was to kill him, not to make him suffer like that," Hollins said. "... I have faith that through my son’s death that we can change a wrong that needs to be changed." The Neiman family provided a statement -- handwritten before the execution -- saying: "God blessed us with our precious daughter, Stephanie, for 19 years. Stephanie loved children. She worked in vacation Bible school and always helped with our church nativity scenes. She was the joy of our life. We are thankful this day has finally arrived and justice will be served."

The family declined comment Wednesday and issued a statement through the state Attorney General's Office asking that their privacy be respected. Tuesday's execution was the first in Oklahoma using a new three-drug cocktail of vecuronium bromide, midazolam and potassium chloride.

David Autry, one of two defense attorneys for Lockett who witnessed the execution, told the Tulsa World on Wednesday that it was “extremely distressing to watch let alone to go through like Mr. Lockett did.” During Lockett’s violent reaction, Autry said he thought “this was obviously a botched execution. I was thinking that Mr. Lockett was not fully sedated and that he was experiencing a great deal of pain.” “For them to claim that he was sedated appropriately and adequately is ridiculous.” Autry said he is unaware of what happened to Lockett after the blinds were drawn 16 minutes into the execution.

“All I know is Director (Robert) Patton came in and said he was halting the execution. I assumed that they were going to try to revive him. What efforts if any they made to revive him or try to counteract the drugs I don’t know.” Autry said the state’s pledge to investigate the botched execution in the two weeks before Warner’s execution “is not going to cut it.” “They are going down the same path they’ve gone down before trying to get this done at all costs regardless. … That’s going to be a whitewash. They are going to paper over this.”

"Death row inmate killed teen because she wouldn't back down," by Ziva Branstetter. (Sunday, April 20, 2014)

Stephanie Neiman was proud of her shiny new Chevy truck with the Tasmanian Devil sticker on it and a matching "Tazz" license plate. Her parents had taught the teenager to stand up for "what was her right and for what she believed in." Neiman was dropping off a friend at a Perry residence on June 3, 1999, the same evening Clayton Lockett and two accomplices decided to pull a home invasion robbery there. Neiman fought Lockett when he tried to take the keys to her truck.

The men beat her and used duct tape to bind her hands and cover her mouth. Even after being kidnapped and driven to a dusty country road, Neiman didn't back down when Lockett asked if she planned to contact police. The men had also beaten and kidnapped Neiman's friend along with Bobby Bornt, who lived in the residence, and Bornt's 9-month-old baby.

"Right is right and wrong is wrong. Maybe that's what Clayton was so scared of, because Stephanie did stand up for her rights," her parents later wrote to jurors in an impact statement. "She did not blink an eye at him. We raised her to work hard for what she got." Steve and Susie Neiman asked jurors to give Lockett the death penalty for taking the life of their only child, who had graduated from Perry High School two weeks before her death. Tuesday, 15 years later, the state plans to carry out that penalty.

Lockett later told police "he decided to kill Stephanie because she would not agree to keep quiet," court records state. Neiman was forced to watch as Lockett's accomplice, Shawn Mathis, spent 20 minutes digging a shallow grave in a ditch beside the road. Her friends saw Neiman standing in the ditch and heard a single shot. Lockett returned to the truck because the gun had jammed. He later said he could hear Neiman pleading, "Oh God, please, please" as he fixed the shotgun.

The men could be heard "laughing about how tough Stephanie was" before Lockett shot Neiman a second time. "He ordered Mathis to bury her, despite the fact that Mathis informed him Stephanie was still alive." Bornt and Neiman's friend "were threatened that if they told anybody about these events, they too would be murdered," court records state. "Every day we are left with horrific images of what the last hours of Stephanie's life was like," her parents' impact statement says.

"We were left with an empty home full of memories and the deafening silence of the lack of life within its walls. ... We feel that the only thing left to do is let Clayton Lockett serve out the sentence of death that a jury sentenced him to. Anything less is a travesty of justice." Bornt wrote a letter Feb. 7 stating: "Clayton being put to death by lethal injection is almost too easy of a way to die after what he did to us. ... He will just be strapped to the table and will go to sleep and his heart will stop beating." 'A base instinct'

Madeline Cohen, an assistant federal public defender who has represented another inmate involved in the case, said she can understand why some people say defendants in murder cases should endure a painful death. "Why should we give them a humane death when they didn't give their victim a humane death? I think that's a base instinct, but that is not what the Constitution provides. ... When we allow our government to take illegal and unconstitutional actions in our name, then all of our rights are jeopardized," she said. Cohen has represented Charles Warner, scheduled to die April 29 for the rape and murder of his girlfriend's 11-month-old daughter, Adriana Waller, in 1997.

Attorneys representing Lockett and Warner have fought a legal battle on multiple fronts against the state's execution-secrecy law. Defense attorneys argue the state should have to reveal the sources of its drugs and other details to ensure the inmates aren't subjected to cruel and unusual punishment. "States have turned to secrecy in the face of drug shortages. It's a reaction to this combination of poorly experimental execution procedures and some frighteningly botched executions," Cohen said. An Oklahoma County District Court judge ruled the state law allowing Oklahoma to withhold most information about execution drugs and procedures violates the state Constitution. The state has appealed that ruling to the state Supreme Court, but Lockett and Warner may be executed before the appeal is considered.

The state Court of Criminal Appeals has refused to grant a stay, saying it can only consider such requests from inmates challenging their convictions before the court. Attorney General Scott Pruitt's office said in an email the state will fight to defend the secrecy law because pharmacies must be protected from "threats of violence and political pressure." In a letter to defense attorneys April 1, the state announced it planned to use a new combination of drugs to execute the men: midazolam, pancuronium bromide and potassium chloride. Defense attorneys cite several cases in which inmates apparently experienced slow or painful deaths during executions.

"This drug regimen has never before been used to execute a prisoner, not only in Oklahoma, but anywhere in the United States," defense attorneys state in their request for a stay. Cohen said protecting pharmacies should not be a reason for the state to "hide information" about the execution process. "As far as the anti-death penalty activists, those people are trying to stop violence and killing," he said. "They are mostly people of faith and conviction. The idea that they would threaten a pharmacist is hard to believe."

LaDonna Hollins, Lockett's stepmother, told an Oklahoma City television station last month her son deserved to be executed for his crimes but should not be made to suffer. "I want to know what mixture of drugs are you going to use now. Is this instant? Is this going to cause horrible pain?" Hollins said. "I know he's scared. He said he's not scared of the dying as much as the drugs administered." Hollins told friends and relatives in a recent Facebook post: "The death penalty is to kill a man for his injustice ... by lethal injection not lethal suffocation."

"Oklahoma Botches Clayton Lockett's Execution," by Baily Elise McBride and Sean Murphy. (04/29/2014 8:32 pm)

McALESTER, Okla. (AP) -- An Oklahoma death row inmate writhed, clenched his teeth and appeared to struggle against the restraints holding him to a gurney before prison officials halted an execution in which the state was using a new drug combination for the first time. The man later died of a heart attack.

Clayton Lockett, 38, was declared unconscious 10 minutes after the first of three drugs in the state's new lethal injection combination was administered Tuesday evening. Three minutes later, he began breathing heavily, writhing, clenching his teeth and straining to lift his head off the pillow. Officials later blamed a ruptured vein for the problems with the execution, which are likely to fuel more debate about the ability of states to administer lethal injections that meet the U.S. Constitution's requirement they be neither cruel nor unusual punishment.

The blinds eventually were lowered to prevent those in the viewing gallery from watching what was happening in the death chamber, and the state's top prison official later called a halt to the proceedings. Lockett died of a heart attack shortly thereafter, the Department of Corrections said. "It was a horrible thing to witness. This was totally botched," said Lockett's attorney, David Autry. Questions about execution procedures have drawn renewed attention from defense attorneys and death penalty opponents in recent months, as several states scrambled to find new sources of execution drugs because drugmakers that oppose capital punishment -- many based in Europe -- have stopped selling to U.S. prisons and corrections departments.

Defense attorneys have unsuccessfully challenged several states' policies of shielding the identities of the source of their execution drugs. Missouri and Texas, like Oklahoma, have both refused to reveal their sources and both of those states have carried out executions with their new supplies. Tuesday was the first time Oklahoma used the sedative midazolam as the first element in its execution drug combination. Other states have used it before; Florida administers 500 milligrams of midazolam as part of its three-drug combination. Oklahoma used 100 milligrams of that drug. "They should have anticipated possible problems with an untried execution protocol," Autry said. "Obviously the whole thing was gummed up and botched from beginning to end. Halting the execution obviously did Lockett no good."

Republican Gov. Mary Fallin ordered a 14-day stay of execution for an inmate who was scheduled to die two hours after Lockett, Charles Warner. She also ordered the state's Department of Corrections to conduct a "full review of Oklahoma's execution procedures to determine what happened and why during this evening's execution." Robert Patton, the department's director, halted Lockett's execution about 20 minutes after the first drug was administered. He later said there had been vein failure. The execution began at 6:23 p.m., when officials began administering the midazolam. A doctor declared Lockett to be unconscious at 6:33 p.m.

Once an inmate is declared unconscious, the state's execution protocol calls for the second drug, a paralytic, to be administered. The third drug in the protocol is potassium chloride, which stops the heart. Patton said the second and third drugs were being administered when a problem was noticed. He said it's unclear how much of the drugs made it into the inmate's system. Lockett began writhing at 6:36. At 6:39, a doctor lifted the sheet that was covering the inmate to examine the injection site. "There was some concern at that time that the drugs were not having that (desired) effect, and the doctor observed the line at that time and determined the line had blown," Patton said at a news conference afterward, referring to Lockett's vein rupturing.

After an official lowered the blinds, Patton made a series of phone calls before calling a halt to the execution. "After conferring with the warden, and unknown how much drugs went into him, it was my decision at that time to stop the execution," Patton told reporters. Lockett was declared dead at 7:06 p.m. Autry, Lockett's attorney, was immediately skeptical of the department's determination that the issue was limited to a problem with Lockett's vein. "I'm not a medical professional, but Mr. Lockett was not someone who had compromised veins," Autry said. "He was in very good shape. He had large arms and very prominent veins."

The American Civil Liberties Union of Oklahoma, which was not a party in the legal challenge to the state's execution law, called for an immediate moratorium on state executions. "This evening we saw what happens when we allow the government to act in secret at its most powerful moment and the consequences of trading due process for political posturing," said ACLU executive director Ryan Kiesel.

In Ohio, the January execution of an inmate who made snorting and gasping sounds led to a civil rights lawsuit by his family and calls for a moratorium. The state has stood by the execution but said Monday that it's boosting the dosages of its lethal injection drugs. A four-time felon, Lockett was convicted of shooting 19-year-old Stephanie Neiman and watching as two accomplices buried her alive in rural Kay County in 1999. Neiman and a friend had interrupted the men as they robbed a home.

Warner had been scheduled to be executed two hours later in the same room and on the same gurney. The 46-year-old was convicted of raping and killing his roommate's 11-month-old daughter in 1997. He has maintained his innocence. Lockett and Warner had sued the state for refusing to disclose details about the execution drugs, including where Oklahoma obtained them. The case, filed as a civil matter, placed Oklahoma's two highest courts at odds and prompted calls for the impeachment of state Supreme Court justices after the court last week issued a rare stay of execution. The high court later dissolved its stay and dismissed the inmates' claim that they were entitled to know the source of the drugs. By then, Fallin had issued a stay of her own -- a one-week delay in Lockett's execution that resulted in both men being scheduled to die on the same day.

"Execution failure in Oklahoma: Clayton Lockett dies of heart attack after vein explodes," by Graham Lee Brewer. ( Modified: April 30, 2014 at 10:07 am)

Oklahoma Corrections Department officials stopped the execution of Clayton Derrell Lockett just before 6:30 p.m. Tuesday after a botched lethal injection that caused Lockett’s body to violently convulse on the table. He died of a heart attack about 40 minutes later. He was declared dead at 7:06 p.m. His death was not witnessed by the media.

Patton later announced Lockett had suffered a “blown vein” and had died of a heart attack. He said all three execution drugs had been administered, but “the drugs were not having the effect.” Concerns about drugs Madeline Cohen, a lawyer representing Warner, expressed deep concern over Tuesday’s execution. “I was in the room with Mr. Warner’s family, so I could not see Clayton Lockett being tortured to death,” Cohen said.

“From our perspective, there should be no further executions in Oklahoma until a full autopsy has been done on Mr. Lockett by an independent pathologist and there has to be full transparency.” Tuesday night, Fallin postponed Warner’s execution until May 13, “to allow the Corrections Department to evaluate the current execution protocol and to allow exhaustion of all possible legal remedies.” The two death penalty cases have been subject to much legal wrangling and court action in the past several weeks.

Lockett was scheduled to be executed April 22, but his execution, along with Warner’s, was stayed by the state Supreme Court. The Supreme Court later dissolved its stay after an executive order from Fallin called the ruling an overreach.

The inmates initially had their executions delayed after a district judge agreed with their attorneys that a law allowing the state to keep secret its source of lethal injection drugs was unconstitutional. The inmates sued the state in January over a law allowing the state to keep its source of lethal injection drugs secret. Lawyers for the inmates argued without validating the purity of the compounded drugs likely to be used in the lethal injections, their clients had no way of knowing whether or not their civil rights would be violated. Cohen said Lockett’s execution validated worry over the never-before-used drugs. “My concerns are certainly are a lot less uncertain than they were a day ago,” Cohen said. “I have to say that I did not want to be validated in this way. It feels very awful.”

"Ponca City man convicted in crime spree." (August 25, 2000)

PERRY - A Ponca City man has been convicted of first-degree murder and 18 other counts involving a crime spree that left Stephanie Neiman dead and two other people injured. A Noble County jury deliberated more than three hours Wednesday before returning the guilty verdicts for Clayton Derrell Lockett, 24.

The penalty phase of the trial began Thursday and was expected to continue until early next week. The June 1999 spree began when Lockett and two others forced their way into Bobby Bornt's residence in Perry, police said. Neiman, 19, of Perry and another 19-year-old from Perry arrived at the home and were accosted by the men. Their hands were bound with duct tape. One of the women was raped. Authorities said the women did not know the suspects.

Bornt, his 9-month-old son and the two women were taken to a location in Kay County where Neiman was shot. Police said the others were put back in trucks, driven back to Perry and released. The child was not harmed. Neiman's body was found in a shallow grave along a dirt road near Tonkawa. One of the suspects led police to the body. The woman's two friends have said they believed they were allowed to live because they had children. In addition to the murder charge, Lockett was found guilty of conspiracy, first-degree burglary, three counts of assault with a dangerous weapon, three counts of forcible oral sodomy, four counts of first-degree rape, four counts of kidnapping and two counts of robbery by force and fear. The charges were after former convictions of two or more felonies, according to the court clerk's office.

Alfonzo LaRon Veasey Lockett, 19, of Ponca City and Shawn C. Mathis, 27, also have been ordered held for trial in Neiman's death. The Locketts are cousins. The three were arrested at Mathis' home in Enid.

"Three Jailed in Kidnappings, Rapes, Woman's Slaying," by Michael McNutt. (June 6, 1999)

(PERRY) - A late-night social visit turned into a deadly nightmare for two Perry women whose arrival interrupted their friend being beaten by three men, authorities said Saturday. One woman was killed. One was raped. Both were beaten and kidnapped, Perry police said. Three men, two of them cousins, were in custody Saturday in the fatal shooting of Stephanie Michelle Neiman, 19, and the kidnapping of three others. Neiman suffered a fatal shotgun wound, authorities said. Neiman's body was found Friday night in a shallow grave along a dirt road west of Ponca City, about 40 miles north of Perry.

The three others kidnapped, including a 9-month-old baby, were taken back to Perry and released. Bobby Lee Bornt, 23, and an 18-year-old woman were beaten. They were treated and released at a local hospital. Bornt's infant son was not hurt. Police Chief Fred LeValley gave no motive for the attacks in his prepared statement. He earlier said the three men knew Bornt.

Two Ponca City men said to be first cousins were being held Saturday night in Noble County jail in Perry. Police identified them as Clayton Derrell Lockett, 23, and Alfhonzo Laron Lockett Veasey, 17. However, the teen gave the name Veasey Alfhonzo Lockett when he was jailed Friday night. Shawn Mathis, 26, of Enid was being held at Perry's police department. All three were arrested Friday afternoon at Mathis' house in Enid after Enid officers spotted Bornt's stolen pickup by the house. Perry police officers drove to Enid to talk with the three men. They brought them to Noble County jail Friday night.

Police suspect the three men were beating Bornt at his house late Friday night when the 18-year-old woman and Neiman arrived, police said. The attackers entered the house a short time earlier by smashing down the front door. They grabbed Bornt and tied him up before beating him, police said. The attackers, armed with a knife and a 12-gauge shotgun, held Bornt, his son and the two women in the house for the next several hours, police said. During this time, the three attackers each raped one of the women, police said.

Eventually, the three men ordered the captives into two pickups and drove them to a secluded spot in Kay County. They were taken out of the pickups and Neiman was shot, police said. Bornt, his son and the woman were returned to Bornt's house. The men left in Bornt's pickup. Police learned about the events about 9 a.m. Friday when one of the victims went to the police station to report what happened. Perry police officers along with deputies from Noble County and nearby Kay County spent the next several hours looking for Neiman. Her body was found about 7:45 p.m. Friday.

"The Botched Execution of Clayton Lockett and Why I’m Ambivalent About the Death Penalty," by Bob Cesca. (April 30, 2014)

In the Summer of 1999, Clayton Lockett and two accomplices, including a man named Shawn Mathis, were burglarizing a home when they were interrupted by 19-year-old Stephanie Neiman as she dropped off her friend who happened to live there. Neiman put up a fight when Lockett attempted to grab the keys to her new Chevy pickup truck. So the men beat her, wrapped her arms, mouth and legs with duct tape and then Lockett and his cohorts beat up Neiman’s friend, as well as another resident of the home and that person’s 9-month-old child. It gets worse.

Neiman and her friends were abducted and driven out to a remote country road. Lockett and his victims waited while Mathis chipped away at the ground, digging a small grave along the road. Neiman was placed in the ditch and Lockett shot her with a sawed off shotgun. But she survived and began pleading for her life. Another shot, but this time the gun jammed. A third shot hit its target. But Stephanie Neiman was still alive. So Lockett and Mathis buried her anyway. Alive.

Fast forward to Tuesday night. After being prosecuted, convicted and sentenced to death, with the ruling upheld by an Oklahoma appellate court, Lockett was scheduled to be executed by lethal injection at the state penitentiary in McAlester, OK. The chemical cocktail used for the execution hadn’t been tested. The Guardian‘s Katie Fretland reported earlier in the week: The state plans to lethally inject Lockett…with midazolam followed by vecuronium bromide and potassium chloride. Florida has used a similar method, but it employed a dose of midazolam that is five times greater. And Ohio used midazolam with a different drug, hydromorphone, in the January execution of Dennis McGuire, which took longer than 20 minutes.

Oklahoma corrections spokesman Jerry Massie briefed the media and said the executions will likely take longer than normal, because the first drug is expected to work more slowly. “Don’t be surprised,” Massie said. In spite of Massie’s eerie caveat, it appears as though corrections officials administering the injections were very surprised when the execution went nightmarishly awry.

Ten minutes into the procedure, Lockett lapsed into unconsciousness. But then, minutes later, he began to writhe and convulse. The AP reported that Lockett was “clenching his teeth and straining to lift his head off the pillow.” The convulsing and gasping reportedly continued for another 10 minutes. Spectators were blocked from continuing to view the scene. The execution was finally aborted after an agonizing 24 minutes. But Lockett died of a heart attack more than an hour later.

It turns out the chemicals failed to rush into Lockett’s body quickly enough — something having to do with a “vein failure” — and hence the slow death. Clayton Lockett was sentenced in a court of law to die, and death is what he got. Though it should never have happened this way. I wanted to lead off this post with the story of what exactly Lockett did to find himself strapped to a gurney inside an execution chamber. In discussions of the death penalty, it’s often too easy to overlook or even forget what execution-worthy trespasses were committed, therefore the criminal is often granted undue sympathy. Make no mistake, Lockett was the worst of the worst — burying a teenager alive, beating a 9-month-old baby, multiple kidnappings, burglary and inflicting psychological torture upon the slain teen’s friends by forcing them to watch. Unforgivable and worthy of harsh punishment.

Clearly, I’m ambivalent about the death penalty. On one hand, I can’t help but to be satisfied that Lockett is gone. Admittedly, this is nothing more than gut instinct and a very emotional, primal, human sense of cold, hard justice. This man took a young woman’s life in one of the most grisly ways possible and therefore I refuse to shed a tear, nor am I capable of doing so, over the fact that the state of Oklahoma forcibly shuffled him off this mortal coil.

On the other hand, and objectively speaking, the death penalty has proved to be an ineffective deterrent, and in terms of recidivism, locking up murderers like Lockett for the rest of his life without parole takes care of that. But what truly makes the death penalty less appealing are circumstances like this horrendously botched execution along with the reality that, according to a recent study, 4.1 percent or one in 25 Americans who are sentenced to die happen to be innocent.

That’s egregiously unacceptable. Unless the penalty can be carried out in a more humane way, and unless there’s indisputable proof of guilt either ascertained by a full and uncoerced confession or based on undeniable DNA evidence which has been verified, tested, re-tested and exhaustively adjudicated, the death penalty shouldn’t be a sentencing option. There’s no reason, in spite of the brutal nature of his crimes, that Lockett should have died in that practically medieval way. His penalty was death, not 24 minutes of what can only be defined as state-induced torture… and then eventual death. Torture wasn’t part of the deal. If Jerry Massie and others knew there could be a problem, why risk the Department of Corrections’ reputation as well as the possibility that the felon might survive? Why attempt an experimental process? The DOC had one job: make sure Lockett dies, and dies expeditiously. They failed to do their job in the most spectacularly cruel and unusual way possible.

It turns out death penalty states including Oklahoma have been scrambling to find new chemical combinations due to the fact that pharmaceutical companies stopped producing the “safest” drug previously used in lethal injections: sodium thiopental. So the guilt is obviously shared among many, though many drug companies have discontinued sodium thiopental for humanitarian reasons.

Do I believe the world is a better place without Lockett in it? I have to be honest and say absolutely — yes. But that is in no way an endorsement of how it occurred or the system as it currently exists. Executions, if they are to continue here, should be noticeably rare and reserved for the most vile and unrepentant among us. However, unless we can guarantee proof of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt and with airtight certainty, and unless a process can be devised that’s both quick and fool-proof, the death penalty, as with any policy this morally delicate and yet this disturbingly imperfect, should be shelved.

One last thing: don’t forget Stephanie Neiman. The reason Lockett chose to bury her alive was because she bravely told him that if she were to be set free she would call the police. For that, she was killed and under circumstances arguably more harrowing than Lockett’s. She died trying to do the right thing, and her killer died because he did one of the worst things imaginable.

"Remembering Stephanie Neiman: Oklahoma Murder Victim's Tragic Story." (Apr 30, 2014 2:56 PM)

PERRY, Oklahoma - The teenager whose murder led to a controversial execution on Tuesday was known for her sweetness and her fondness for her pickup truck. The parents of murder victim Stephanie Neiman have not spoken publicly since the execution of Clayton Derrell Lockett went awry. But a letter they wrote for Lockett's clemency hearing in February indicates what they were feeling leading up to Tuesday night.

Lockett murdered Neiman on June 3, 1999. Stephanie, 19, had just graduated from Perry High School, where she played the saxophone in the band, two weeks earlier. Neiman and a female friend had stopped to visit another friend named Bobby Bornt, 23, who was at his Perry home with his 9-month-old son. Clayton Lockett, 23, his cousin, Alfonzo Lockett, 17 and Shawn Mathis, 26, were already there. While Bornt's baby son slept in another room, they had tied up and were beating Bornt because he owed money to Clayton Lockett. When Neiman's friend went inside the home they hit her with a shotgun then forced her to call Neiman into the home.

They repeatedly raped Neiman's 18-year-old friend, tied up the two women then used Neiman's truck to take the adults and the baby to a rural part of Kay County. When Neiman refused to give Clayton Lockett the keys to her truck or provide him the alarm code, he ordered Stephanie to kneel while Mathis dug a grave. Lockett shot her and the gun jammed. While Neiman lay there screaming, the attackers cleared the jam and Lockett shot her a second time. Even though she was still breathing, he ordered the other two attackers to drag her into the grave and bury her. They threatened to kill Bobby Bornt and Neiman's friend if they went to police, but they did anyway. Perry police arrested the three attackers just three days later.

Alfonzo Lockett and Shawn Mathis are each serving life terms for their parts in the crime. On February 28, 2014, the Oklahoma Attorney General's office presented a packet of information at a clemency hearing for Clayton Lockett. The packet contains details of the case, as well as the results of Lockett's appeals to that point. It details his long criminal history and the punishment he's received for making threats and misbehaving since being convicted of the murder, including throwing urine and feces at the corrections officers bringing him food.

It also contains heartwrenching victim impact statements from Bornt, Neiman's friend and fellow victim, Neiman's parents and law enforcement officers involved in the case. Writing on behalf of her husband, Steven, Susie Neiman said that the last 15 years have been "HELL." Read Susie Neiman's Victim Impact Statement. "Every day we are left with horrific images of what the last hours of Stephanie's life was like. Did she cry out for us to help her? We are left with the knowledge that she needed us and we were not aware of it therefore unable [to] help her."

"We go through the motions of living, we eat, we sleep, Steve goes to work and comes home again. We do what we have to do to make it through the day and we start all over again the next. We exist," she wrote. "We were left with an empty home full of memories and the deafening silence of the lack of life within it's [sic] walls. We have moved, but in our new home Stephanie also has a bedroom which is filled with her treasures and belongings." She also writes that she and her husband will never know the joy of grandchildren because Stephanie was an only child.

"Clayton Lockett made choices on June 3, 1999. Actions have consequences. It is time that he face the full consequences of murdering our daughter Stephanie. She deserves that. A jury decided Clayton Lockett's fate and we believe it is time for justice to finally be carried out." Susie and Steve Neiman released a statement Tuesday night and said they do not wish to issue any further statements on their daughter's murder or the execution and ask their privacy be respected. "God blessed us with our precious daughter, Stephanie for 19 years. Stephanie loved children. She worked in Vacation Bible School and always helped with our church nativity scenes. She was the joy of our life. We are thankful this day has finally arrived and justice will finally be served."

"Oklahoma Team Struggled to Find Vein Before Botched Execution," by Pete Williams. (May 2, 2014)

The lethal injection in the botched Oklahoma execution was given through the inmate’s groin after a specialist could not find a good spot on his arms, legs or feet, the state’s prison chief revealed Thursday. Clayton Lockett’s legal team denounced the method as “invasive and painful,” speculated that it was done incorrectly and accused the state of trying to “whitewash” the death-row debacle.

The new details about how the three-drug combination was administered came in a letter from Department of Corrections director Robert Patton to Governor Mary Fallin, which also disclosed that Lockett was Tasered and cut his own arm in the hours before the execution. Patton recommended an indefinite delay in executions until a review of the state's lethal injection protocol ordered by Fallin is complete.

Fallin had ordered a two-week delay in the next execution, but Patton said it could take longer "to refine the new protocols." "I intend to explore best practices from other states and ensure the Oklahoma protocol adopts proven standards," he wrote.

He also suggested that state officials more senior than a prison warden should have the responsibility of making execution decisions. Lockett’s death has renewed debate over the use of lethal injections amid drug shortages that have forced states to come up with new execution formulas. Oklahoma was trying a new drug protocol on Lockett, who raped one woman, shot another and ordered two accomplices to bury her alive.

Witnesses have said Lockett, 38, appeared to be awake, in pain and struggling several minutes after he was declared unconscious. His movements on the death-chamber gurney were not mentioned in Patton's timeline of the execution, which did reveal that Lockett was not cooperative during execution preparations. Prison officers used a stun-gun on condemned man when he refused to be restrained for pre-execution medical X-rays, Patton said. During the subsequent exam, a "self-inflicted laceration" was discovered on his right arm, but it did not require stitches, he wrote.

Lockett, 38, also refused final visits with his lawyers and his last meal. After he was brought to the execution chamber, a phlebotomist could not find a good place on his arms, legs and feet to put the IV and instead ran the line into his groin.

Other key points in the timeline:

•6:18 p.m. — Lethal injection IV lines are inserted.

•6:23 p.m. — The first drug, midazolam, is given to cause loss of consciousness.

•6:33 p.m. — Doctor declares Lockett unconscious and begins administering two other drugs, the paralytic vecuronium bromide and the heart-stopper potassium chloride.

•6:42 p.m. — Shades lowered to block view by witnesses.

•6:44 to 6:56 p.m. — Doctor reports blood vein collapsed, drugs either absorbed into tissue, leaked out, or both. Doctor says not enough drugs have been administered to cause death, that no other vein is available, and that not enough drugs remain. The doctor detects a faint heartbeat.

•6:56 p.m. — Execution is halted.

•7:06 p.m. — Lockett pronounced dead.

A second inmate, Charles Warner, who raped and killed an 11-month-old baby, was due to be executed right after Lockett but his lethal injection was rescheduled for May 13.

"Is Lethal Injection Painful? by Pete Williams. (May 1, 2014)

Warner’s lawyer, Madeline Cohen, said she agrees with Patton’s call for an indefinite stay of execution and urged that the probe be carried out by someone outside Fallin’s administration. “Oklahoma is revealing information about this excruciatingly inhumane execution in a chaotic manner, with the threat of execution looming over Charles Warner,” she said.

“No execution should take place in Oklahoma until there has been time for a thorough and truly independent investigation into the protocol, the drugs and the manner in which Oklahoma carries out executions. “This most recent information about the tortuous death of Mr. Lockett, and the State's efforts to whitewash the situation, only intensifies the need for transparency."

"White House: Botched Execution Was Not Humane," by Tracy Connor. (April 30, 2014)

The White House is criticizing Oklahoma's botched execution of Clayton Lockett, who appeared to be in pain and struggling to sit up minutes after he was pronounced unconscious. Press Secretary Jay Carney said that while he has not discussed the case with President Barack Obama, anyone would agree Tuesday's lethal injection was not humane. "He has long said that while the evidence suggests that the death penalty does little to deter crime, he believes there are some crimes that are so heinous that the death penalty is merited," Carney said.

"In this case, or these cases, the crimes are indisputably horrific and heinous. But it's also the case that we have a fundamental standard in this country that even when the death penalty is justified, it must be carried out humanely. And I think everyone would recognize that this case fell short of that standard." Lockett's execution was halted by prison officials who said an intravenous line blew, but he died afterward of a massive heart attack.

A second execution scheduled for that night was postponed for at least two weeks while state officials conduct a review. It was the first execution using Oklahoma's new three-drug protocol, which defense lawyers have denounced as experimental. Lockett also fought unsuccessfully to force the state to reveal where it obtained the chemical.

Lockett's aunt, Deanna Parker, told NBC News that she agreed with the White House's characterization of her nephew's death. "I wish they would have spoken up before all this," she said.

"Oklahoma Execution: Family of Inmate Eyes Lawsuit," by Tracy Connor.

The family of a death-row prisoner who died after a botched lethal-injection said they are considering a lawsuit against Oklahoma to force changes in the execution process. "I'm not seeking financial gain from this," said Ladonna Hollins, the stepmother of convicted killer and rapist Clayton Lockett, who appeared to regain consciousness and struggle in pain in the middle of his execution Tuesday night.

"My main thing is I want the process changed," Hollins told NBC News as she waited for her son's body to be released so she could begin planning a funeral. "I want them to admit they did wrong and after that, let’s change this," said Hollins, who has not retained a lawyer yet. "If we are going to put people to death, let's do it the right way."

Prison officials — who halted the execution, but not in time to save Lockett — said an intravenous line blew while the deadly drugs were being administered. The governor has ordered an investigation. But the dead man's family suspects a last-minute switch to new execution drugs, which were obtained behind a veil of secrecy, is to blame. They are seeking an independent autopsy. "If we are going to put people to death, let's do it the right way."

Relatives of an Ohio inmate who was executed in January with an untested combination of drugs filed a federal suit against the state, charging it violated the constitutional protection against cruel and unusual punishment. A lawyer for the family of Dennis McGuire — who took 25 minutes to die and appeared to gasp for air — said they are not interested in collecting damages, just getting the court to bar the chemicals from being used again. The case is pending. Meanwhile, Ohio's prison agency just announced its internal review of the execution found it was "humane" and it's moving ahead with more lethal injection using the same drug combination.

Post-execution lawsuits on behalf of the condemned are rare, experts said. The family of Joseph Clark — whose 2006 execution took 86 minutes after the team struggled to find a usable vein — filed a $150,000 suit that was ultimately thrown out by a judge who ruled his suffering was not "intolerable." In his decision, the judge said he had not been able to find another case where a prisoner's estate sued after the execution for an Eighth Amendment violation. "It's largely an uncharted area because there is not a whole lot of prospect of winning," said Richard Dieter, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, which opposes capital punishment.

He said death-row inmates often have very distant relationships with family, who can't argue economic losses from their death. "And I don't think any court will want to award too much to the family of a killer," he said.

But he said that Lockett's family might have the best shot at success — because the state was using a new protocol and had to stop the execution before it was complete. "Oklahoma has broken new ground in a lot of bad ways," he said.

Brian Ted Jones in General Writing: Idea, Thinking, Opinion

The Life of Clayton Lockett: A short biography

Clayton Derrell Lockett was born on November 22, 1975. His mother used drugs during the pregnancy, and when Clayton was three years old, she placed him on his father’s doorstep and walked away. When his father found him, he was soaked in urine. After his mother abandoned him, Clayton became uniquely attached to his father, coming to idolize the man. Yet Clayton’s father beat his son, regularly and severely, stripping him naked and striking him with belts and boards. He would also frequently threaten the child with guns.

Clayton first began using drugs at age three—at his father’s insistence. Clayton’s father was a criminal, and taught his son to steal, punishing the boy if he were caught. He watched pornographic movies in the child’s presence, and encouraged his son to become sexually active at a very early age, telling the boy that women are “no good,” and that they exist only to do what men want. Several members of Clayton’s family believed his older brother had sexually abused him when he was little. Clayton sucked his thumb and wet the bed until he was 12. While still very young, he suffered a bad fall, with a concussion. When Clayton was 16, he was incarcerated at a correctional center meant for adults. While there, he was raped by three men.

On June 3, 1999, Clayton was 23 years old, and already a convicted felon (for burglary). Around 10:30 that night, Clayton and two other men broke into the house of a Perry, Oklahoma resident named Bobby Bornt. Bobby had been asleep on the couch, while his nine-month-old son, Sam, lay sleeping in a back bedroom. Clayton struck Bobby with a shotgun; all three men then beat Bobby, tied his hands with duct tape, gagged him, and left him on the couch while they searched the house for drugs. Around that time, Bobby’s friend, Summer Hair, approached the front door. She was pulled inside, beaten, and told to call for her friend, Stephanie Neiman, who was outside waiting in her pickup truck. Summer did as the men said, and when Stephanie entered the house, she, too, was captured. Two of the men, including Clayton, then raped Summer.

The captors bound their victims, and Clayton instructed one of the two men to look in the garage and find a shovel. The victims, including Sam, were loaded into two pickups, one belonging to Bobby, the other to Stephanie. They drove to a country road in Kay County, Oklahoma. There, Clayton raped Summer again. The men dug a shallow hole, and decided to kill Stephanie. Clayton shot her, but the shot did not kill her right away. She was buried alive in the shallow hole. The men then returned to Bobby’s house, where they left Bobby, Sam, and Summer behind. Police arrested Clayton the next day, and he confessed to the murder.

Trials in Oklahoma where the State seeks the death penalty are split in two: the first stage determines guilt, and the second, punishment. At the guilt stage, the State presented Clayton’s videotaped confession. He admitted he’d gone to Bobby’s house to rob him; admitted to beating him, and Summer, and Stephanie; admitted to binding them all with duct tape; admitted to kidnapping them; admitted to making the decision that Stephanie would die; admitted to shooting her, while she wept; and he admitted to insisting that she be buried while she was still living. He denied raping Summer, and claimed to have held, comforted, and fed Sam at the house (he also claimed to have changed the baby’s diaper at the murder site). The jury found Clayton guilty, and in the second stage of the trial—the stage for determining whether Clayton would receive the death penalty—the State presented evidence that Clayton had sent jail-letters to friends suggesting that his gang, the Crips, kill Bobby and Summer ahead of his trial. He also claimed to be tracking his surviving victims’ movements—a claim corroborated by his knowledge of Bobby and Summer’s addresses and Social Security Numbers. Clayton had also written letters to jail personnel where he boasted about his IQ (190), martial arts prowess (two black belts), and advanced criminality (claiming he’d stabbed multiple corrections officers, started a prison riot, and would not be convicted, because his gang would not allow it). On October 5, 2000, the jury sentenced Clayton to death.