Executed June 15, 2007 12:29 a.m. CDT by Lethal Injection in Indiana

23rd murderer executed in U.S. in 2007

1080th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

2nd murderer executed in Indiana in 2007

19th murderer executed in Indiana since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

Michael Allen Lambert W / M / 20 - 36 |

Greg Winters OFFICER W / M / 31 |

Final Words:

None.

Citations:

Direct Appeal:

Lambert v. State, 643 N.E.2d 349 (Ind. December 6, 1994)

Conviction Affirmed 5-0; DP Affirmed 3-2

Givan Opinion; Shepard, Dickson concur; Debruler, Sullivan dissent.

(Case was remanded back to trial court before this opinion to allow for correct application of intoxication as mitigator)

Lambert v. State, 675 N.E.2d 1060 (Ind. 1996)

(On Rehearing, DP Affirmed 4-1 despite error in admitting victim impact evidence)

Selby Opinion; Shepard, Dickson, Sullivan concur; Boehm dissents.

Lambert v. Indiana, 117 S.Ct. 2417 (1997) (Cert. denied).

Lambert v. Indiana, 118 S.Ct. 7 (1997) (Rehearing denied).

PCR:

PCR Petition filed 10-01-97.

PCR denied 07-10-98 by Delaware Superior Court Judge Robert L. Barnet, Jr.

Lambert v. State, 743 N.E.2d 719 (Ind. March 5, 2001)

(Appeal of PCR denial by Delaware Superior Court Judge Robert L. Barnet, Jr.)

Conviction Affirmed 5-0; DP Affirmed 5-0

Sullivan Opinion; Shepard, Dickson, Boehm, Rucker concur. Lambert v. Indiana, 122 S.Ct. 1082 (2002) (Cert. denied).

Lambert v. State, 825 N.E.2d 1261 (Ind. Apr 28, 2005) (18S00-0412-SD-503).

(Lambert sought leave to file successive petition for state postconviction relief. Held: Denied; Indiana Supreme Court, on direct appeal, had appellate authority to independently reweigh the proper aggravating and mitigating circumstances, as remedy for improper victim impact evidence admitted during trial.)

Shepard Opinion; Dickson, Sullivan concur. Rucker, Boehm dissent.

Habeas:

Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus filed on 11-13-01 in U.S. District Court, Southern District of Indiana.

Writ denied 11-07-02 by U.S. District Court Judge Larry J. McKinney.

Lambert v. McBride, 365 F.3d 557 (7th Cir. April 7, 2004).

(Appeal of denial of Habeas Writ - Affirmed 3-0 - Ring does not apply retroactively).

Circuit Judge Terence T. Evans, Judge Kenneth F. Ripple, Judge Michael S. Kanne.

05-12-05 Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus filed in U.S. District Court, Southern District of Indiana.

Judge Larry J. McKinney

05-31-05 Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus dismissed for lack of jurisdiction; Stay denied.

06-17-05 Stay of Execution ordered by 7th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals for scheduled 06-22-05 execution date. “In due course, the court will issue an order addressing whether a certificate of appealability should be issued.

Lambert v. Davis, ___ F.3d ___ (7th Cir. May 31, 2006) (05-2610)

Appeal of dismissal of Successive Petition for Habeas Relief.

(Whether Lambert was entitled to benefit of “Saylor” rule is a matter of state, not federal, law)

Affirmed 2-1; Opinion by Circuit Judge Terence T. Evans.

Judge Michael S. Kanne concurs; Judge Kenneth F. Ripple dissents.

For Defendant: Alan M. Freedman, Midwest Center for Justice, Evanston, IL

For State: Stephen R. Creason, Deputy Attorney General (S. Carter)

Internet Sources:

Clark County Prosecuting Attorney

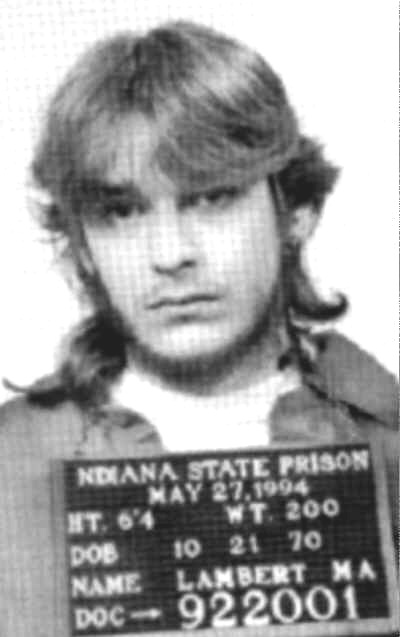

ON DEATH ROW SINCE 01-17-92

DOB: 10-21-1970

DOC#: 922001

White Male

Delaware County Superior Court

Judge Robert L. Barnet, Jr.

Prosecutor: Richard W. Reed, J.A. Cummins, Jeffrey L. Arnold

Defense: Ronald E. McShurley, Mark D. Maynard

Date of Murder: December 28, 1990

Victim(s): Gregg Winters W/M/31 Muncie Police Officer

Method of Murder: shooting with .25 handgun

Trial: Information/PC for Murder and DP filed (01-09-91); Voir Dire (11-04-91, 11-06-91, 11-07-91, 11-08-91, 11-11-91, 11-12-91, 11-13-91); Jury Trial (11-13-91, 11-14-91, 11-15-91, 11-16-91); Deliberations over 2 days; Verdict (11-16-91); DP Trial (11-18-91); Verdict (11-18-91); Court Sentencing (01-17-92).

Conviction: Murder

Sentencing: January 17, 1992 (Death Sentence)

Aggravating Circumstances: law enforcement victim

Mitigating Circumstances: 20 years old at the time of the murder, lack of guidance in upbringing, intoxication at time of murder, positive signs of rehabilitation

Also Serving Time For:

Burglary, sentenced to 8 years imprisonment on 08-31-92. (Delaware County)

Battery, sentenced to 8 years imprisonment on 11-07-97. (LaPorte County)

"Inmate executed for killing Muncie police officer," by Tom Coyne. (Associated Press June 15, 2007)

MICHIGAN CITY, Ind. — The man convicted of fatally shooting a Muncie police officer more than 16 years ago was executed early Friday. Michael Lambert, 36, was pronounced dead at 12:29 a.m. CDT following the lethal injection procedure, Indiana State Prison spokesman Barry Nothstine said. Lambert did not offer a final statement.

Some 20 police cars arrived at the prison about two hours before the execution, bringing dozens of officers and others from Muncie and elsewhere, including LaPorte, Mishawaka, South Bend and Gary. As they awaited word of the execution, they held blue glowsticks given to them by the widow of Officer Gregg Winters to represent the “thin blue line” he was on the night he was killed.

Molly Winters hugged supporters outside the prison soon after Lambert’s death was announced and said she was relieved it was over. “Justice has been served,” she said. “You look at all the blue lights behind you. It shows you that Gregg has not been forgotten and everything he stood for.” Lambert’s execution came about nine hours after the U.S. Supreme Court rejected, without commenting, his final appeal. Gov. Mitch Daniels on Wednesday had denied his clemency petition.

Lambert fatally shot Winters on Dec. 28, 1990, while Winters was driving him in a cruiser to the Delaware County Jail on a charge of public intoxication. Another officer had patted Lambert down but did not find the gun he had in his pocket. Lambert shot Winters five times in the head, and the officer died 11 days later.

Terry Winters, the slain officer’s brother and deputy chief of the Muncie Police Department, witnessed the execution under a state law that took effect last year giving relatives of murder victims that right. “It was not an easy thing, but his death was a lot smoother than what my brother’s was,” Terry Winters said of watching the lethal injection. “His punishment for that crime was death and it’s been carried out. And that’s the end of it.”

Molly Winters had decided not to watch the execution, saying she was with her husband when he died and that she did not want Lambert’s death to also be in her memories. The couple’s two sons, 19-year-old Kyle and 17-year-old Brock, joined their mother at the prison. “It’s just more relief that this part’s over even though it’s still not going to bring Dad back,” Kyle Winters said. Brock Winter’s eyes welled up and he did not speak as his family members commented.

Lambert said in an interview last week that he could not remember what happened the night of the shooting and had no explanation for why he shot Winters. “No one in their right mind is going to sit there facing a public intoxication charge or something like that and go to that extreme,” he said. “That’s one of the aspects of this thing that makes it hard to come to terms with.”

Muncie police Detective Brad Wiemer, who was among those who traveled to the prison, said the group was there in a show of support for the Winters family. “In a horrible, tragedy situation like this, it’s just nice to see the support come out, especially from different areas,” Wiemer said.

Some 25 anti-death penalty protesters carried signs and banged drums outside the prison’s main gate in the hours before the execution. The Rev. Tricia Teater, a Buddhist priest from Chicago, said she spent Thursday afternoon with Lambert, praying, mediating and chanting. “It is a very sad thing for this society to keep spinning the cycle of violence and creating more victims and more pain,” she told the protesters.

Lambert’s attorneys had asked the Supreme Court on Monday to stay the execution on several grounds, including the fact that three of the five Indiana Supreme Court justices had at times during his appeals ruled his death sentence was “constitutionally deficient.” The appeals argued that the execution should be blocked because the state’s high court had found that the jury in Lambert’s case was improperly exposed to victim impact evidence. “We thought that in America three out of five wins, an issue that was constantly going around throughout the case of an unfair sentencing hearing,” Lambert attorney Alan M. Freedman said Thursday. “But that’s part of the process and we’ve lost.” Lambert’s attorneys did not speak with reporters following the execution.

Lambert, who did not request a special last meal, met Thursday with some friends after having visited with family members earlier in the week, said Nothstine, the prison spokesman.

"Protests, prayers mark final hours for Lambert; Authorities at the Indiana State Prison early Friday were preparing to execute Muncie resident Michael Lambert," by Nick Werner. (Jun 15, 2007)

MICHIGAN CITY -- With the life of convicted killer Michael A. Lambert apparently in its final hours, opponents of capital punishment gathered outside the walls of the Indiana State Prison to protest his execution. Lambert, 36, Muncie, was to be killed by lethal injection in the prison's death chamber shortly after 1 a.m. Friday (Muncie time).

The execution date fell more than 15 years after the Muncie man received a death sentence -- from Delaware Circuit Court 3 Judge Robert Barnet Jr. -- for the slaying of Muncie police officer Gregg Winters. Lambert's last hopes of a stay of execution faded Thursday afternoon when his Chicago-area attorneys called him with word that all 11th-hour appeals had failed.

Indiana State Prison spokesman Barry Nothstine said he escorted the condemned killer to a telephone and was with him when he received the news. "He really didn't say anything..." Nothstine said. "He's been very quiet and calm throughout today and the entire week."

In what was almost certain to be his last day, Lambert began meeting with friends at 8 a.m. Central Time, Nothstine said. He met with four friends during the day. Lambert had already met with his relatives earlier this week and did not want family members in Michigan City for his execution, Nothstine said. At 4 p.m. Lambert was escorted to a holding room next to the execution chamber, where he met with a spiritual adviser, Nothstine said.

The adviser, a Buddhist priest from Chicago, told reporters Thursday night she spent about two hours with Lambert, praying, meditating and chanting near an altar of incense and candles. "He's in a place he needs to be at this time," said the priest, Tricia Teeter. Teeter also expressed her discontent with the death penalty. "Tonight we see the cycle of violence continue right in front of our eyes," she said. In the two minutes she addressed media, Teeter did not mention how long Lambert had been a Buddhist or what drew him to Buddhism. "I promised him I would see him at sunrise in the morning," she said.

By 9 p.m. Muncie time, opponents of the death penalty began filing into a parking lot across the street from the prison, an area has been designated for such vigils and demonstrations. Within minutes they numbered about 20, mostly members of the Duneland Coalition to Abolish Capital Punishments. They carried picket signs, folding chairs, tom-toms and anti-death penalty literature, anticipating Lambert's execution in about four hours. Their signs read, "Death Penalty Moratorium Now," and "Shame Never Kill in Our Name" and "The State is not the Angel of Death." Protesters said they planned to light vigil candles, beat drums, toll bells and sing abolition songs.

Rev. Charles Doyle of the Gary Roman Catholic Diocese, is the Duneland's president. Execution is playing God, Doyle said, and puts the state on the same level as the murderer. "If we consider them so dangerous, we can safely keep them away from the community without killing them," Doyle said.

A few police officers, mainly from the Indianapolis area, later gathered in the parking lot to show their support of the death penalty. Mark Hamner, a patrolman with the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department, disagreed with protesters' beliefs that the death penalty did nothing to deter future crimes. "One thing is for sure; Michael Lambert is never going to kill again," Hamner said, as drum beats from about 30 picketing protesters echoed in the background.

Hamner did not know the Winters family and was not involved in any organized efforts to show support for them. He said he has attended four executions, not just those involving fallen officers. Hamner grilled meat on a charcoal grill and drank soda, much like he was tailgating.

A group of Muncie police officers and supporters of the Winters family were believed to be waiting out the evening in a nearby park. Terry Winters, Muncie's deputy police chief and brother of the slain officer, was to witness the execution. A large contingent of police vehicles -- including Muncie police cars -- arrived outside the prison about 10:45 p.m., some with flashing lights.

Lambert fatally shot Gregg Winters on Dec. 28, 1990, while Lambert was being taken to the Delaware County Jail on a charge of public intoxication. A police officer who patted Lambert down did not find the gun he had in his pocket. Lambert shot Winters five times in the head, and the officer died 11 days later.

"Widow believes officer finally at peace; Michael A. Lambert was declared dead in the state prison's death chamber at 1:29 a.m. Friday," by Nick Warner. (June 16, 2007)

MUNCIE -- The spirit of slain Muncie police officer Gregg Winters was present throughout all the court proceedings and legal battles that concluded with his killer's execution early Friday, his widow Molly Winters said. When Molly Winters and their two sons became overwhelmed or tired, Gregg Winters remained as attentive in death as he was in life, providing his family with the extra strength it needed to go on, Molly Winters said Friday afternoon. "Now that justice has been served, he's resting peacefully in heaven," she added.

On Dec. 28, 1990, 20-year-old Michael Lambert used a .25-caliber handgun hidden somewhere on his body to shoot Winters five times in the head and neck as Winters was transporting Lambert to a temporary jail on Riggin Road. Police had found Lambert drunk under a car earlier that night in the 1000 block of East 24th Street and arrested him on a charge of public intoxication. Greg Winters died 11 days later at the age of 32.

Convicted of murder by a Delaware Superior Court 1 jury in November 1991, Lambert was sentenced to death two months later by Judge Robert Barnet Jr.

The Muncie man was pronounced dead from lethal injection at 1:29 a.m. (Muncie time) Friday in the execution chamber of the Indiana State Prison in Michigan City, prison spokesman Barry Nothstine said. Lambert, 36, had been cooperative with prison employees and did not offer any final statement.

Gregg Winters' brother, Terry, a deputy police chief for the Muncie Police Department, was the only representative of the Winters family to witness Lambert's execution. "His death was a lot smoother than what my brother's was," Terry Winters told reporters outside prison walls just minutes after the execution.

The rest of the family and about six Muncie police officers who were close to Gregg Winters awaited confirmation of Lambert's death inside a room used for parole board hearings. The news for them came in the form of a radio transmission from a victim advocate who witnessed the execution to a victim advocate stationed with the small group. "When I heard that I just kind of stood there," Molly Winters said.

The scene outside the prison was equally subdued. Death penalty protesters began filing in to a parking lot across a street from the prison's eastern gate about 8 p.m. At their peak, they numbered somewhere between 20 and 30.

The protesters, mostly from the Dunelands Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty, brought folding chairs, tom-tom drums and florescent picket signs with such phrases as "Death is God's Business" and "Thou Shalt Not Kill." John Souder Roser, a 73-year-old retired truck driver from Porter County, said his father had been a social worker at the Indiana State Prison and he grew up in a house on prison grounds. "I believe it's wrong," he said. "It's totally insane. It makes me a murderer. I'm part of the state of Indiana and I'm culpable in this man's death."

Lambert's spiritual adviser, a Buddhist priest from Chicago addressed the protesters, telling them she prayed, chanted and meditated with Lambert near an altar of candles and incense for about two hours Thursday. "Tonight we see the cycle of violence continue right in front of our eyes," she said.

What had largely been a demonstration against capital punishment changed around 10 p.m. Sirens north of the prison interrupted the calm, signaling the arrival of those wishing to show their support for Gregg and Molly Winters. A caravan of about 30 sport-utility vehicles and marked and unmarked police cars, some with lights flashing, ushered in at least 70 people. Many wore T-shirts emblazoned with a police badge and the words "In Memory of Gregg Wm. Winters."

Most were either off-duty officers belonging to Indiana's Fraternal Order of Police or surviving family members of other officers killed in the line of duty. About a dozen were Muncie police officers in uniform, including Jeff Leist, who played softball on the Muncie FOP team with the Winters brothers. "We had a lot of good memories,' Leist said. "He was a good police officer, dad and husband. He was a great man."

Mike Goodwin was in this group. His brother, Cpl. Thomas Goodwin of the Goshen Police Department, was shot and killed in 1998. Molly Winters helped guide Mike Goodwin and Goshen officers through their grief, he said. "She's done so much for our family," Goodwin said. "This is a small way to pay her back."

At 11 p.m., these supporters distributed blue glow sticks, an alternative form of candlelight vigil to express the "thin blue line" of law enforcement. As the execution neared, the crowd formed a line along the prison's wrought iron fence, holding the glow sticks in outstretched arms toward the prison.

This was the image Molly Winters first saw as she left the prison after Lambert's death with her sons, Kyle, 20, and Brock, 17, at her side and Terry Winters nearby. Molly, Terry and Kyle Winters briefly spoke to reporters at the prison's gate before embracing their supporters one-by-one. "It's just a relief," Kyle said. "Even though it's still not going to bring my dad back."

"Execution Means Justice for Wife of Officer Killed." by Debbie Knox. (June 15, 2007 07:06 AM EDT)

INDIANAPOLIS - The execution of Michael Lambert means justice for Molly Winters, the wife of Muncie Police Officer Gregg Winters. Winters was killed in 1990 when Lambert, a handcuffed prisoner in Winters' patrol car, used a concealed handgun to shoot Winters in the back of the head five times. Days later Gregg Winters died. Lambert was sentenced to death for the crime.

"Five days before Gregg was shot he said, 'Let's talk about something.' And I said, 'Okay, what do you want to talk about?' And he said, 'If anything ever happens to me this is what I would want at my visitation, this is what I want at my funeral. This is what I want for the future for you and the boys,'" Molly remembered. "That was God's way of as much as he could prepare me, prepare me," she said.

"I went to bed about 1:30 that night and at about 20 till 2:00, Brock who was 10 months at the time cried out. And I thought oh, we have another ear infection and I later found out that's when Mike Lambert shot Gregg in the head." "I was with Gregg when he took his last breath and will remember that. It'll be forever etched in my mind. I will not give Mike Lambert the honor of being in my memories for the rest of my life. That's not going to happen," she said.

"Every milestone that my children has gone through has been difficult, when they learned to write their name, they had to write it on a piece of paper and attach it to a helium balloon and send it to heaven so Daddy could see that they now could write their name. Same way when they started writing numbers. They're very angry that they haven't had their dad here to share things with them."

"It's been 17 years of fighting the battles and fighting for victims rights and trying to make a huge positive out of a horrible tragedy and now it's time for Gregg and it's time that he get to rest," she said. "I will be there. I will be standing there quietly with my blue glo-stick that represents Gregg and the thin blue line of law enforcement and I'm ready for justice."

"Inmate executed for killing Muncie police officer." (June 15, 2007 12:34 PM EDT)

Michigan City - The man convicted of fatally shooting a Muncie police officer more than 16 years ago was executed early Friday. Michael Lambert, 36, was pronounced dead at 12:29 a.m. CDT following the lethal injection procedure, Indiana State Prison spokesman Barry Nothstine said. Lambert did not offer a final statement.

At midnight, white lights of protest shone from death penalty opponents who stood outside the Indiana State Prison in Michigan City. There were blue lights of support held by relatives of police and other slain lawmen remembering Greg Winters.

Molly Winters, her two sons and supporters left the prison with the justice they have waited more than 16 years for. "Relief," Molly Winters said tearfully. "Justice has been served and look at all the blue lights behind you - it tells us that Greg has not been forgotten and everything he stood for." "This part's over even though it's still not gonna bring Dad back," said Kyle Winters. "Just a relief."

Officer Winters was shot to death in his patrol car by Michael Lambert. Winters' brother, a Muncie police deputy chief, witnessed the execution. "His death was a lot smoother than what my brother's was and his punishment for that crime was death and it's been carried out and that's the end of it," said Terry Winters.

During the last 16 years, Molly Winters has said she's been on a journey that at times felt as though she were in prison as well. "There is a feeling of being set free because when Lambert put those five shots in the back of Greg's head, I said as long as I live, I will be at every court hearing and I will do everything I can do every step of the way to make sure that one day Greg will rest peacefully and that there will be justice, and it's done," she said. Now Molly Winters continues her journey, embraced and surrounded by friends.

Lambert's execution for the killing of Officer Gregg Winters came about nine hours after the U.S. Supreme Court rejected, without commenting, his final appeal. The U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday denied, without commenting, to grant Lambert's request that the execution be blocked. That step came a day after Governor Mitch Daniels denied his clemency petition.

"3:13 p.m.: Lambert doesn’t like change in who can watch executions." (The Associated Press Published June 14, 2007 03:12 pm)

MICHIGAN CITY, Ind. (AP) — When Michael Lambert was set to be executed two years ago, he agreed to let the brother of the police officer he fatally shot more than 16 years ago watch him die. That execution was stayed. Since then, a change in Indiana law means he has no say over who in Muncie Officer Gregg Winters’ family can watch his execution now set for early Friday. It’s a change Lambert doesn’t like. “I don’t think anyone should be given that choice,” he said during an interview last week. “It’s not natural just to come in and watch someone die — not just die, but watch someone be killed. It’s not natural.”

Terry Winters, deputy chief of the Muncie Police Department, thought it was unfair he needed to ask Lambert for permission two years ago. “My brother is the victim here and it shouldn’t be up to him (Lambert),” Winters said.

Gov. Mitch Daniels on Wednesday denied clemency for Lambert. The governor did not elaborate on his decision, which was issued in a brief statement from his office. “Obviously, we’re very disappointed,” Larry Komp, one of the attorneys representing Lambert through the Midwest Center for Justice in Evanston, Ill., said Wednesday.

Lambert’s last chance to avoid execution rested with the U.S. Supreme Court. His attorneys on Monday asked the Court to stop it on several grounds, including the fact that three of Indiana’s five Supreme Court justices have at times during his appeals ruled his death sentence is “constitutionally deficient.” The high court had not ruled as of Thursday afternoon.

Lambert killed Gregg Winters on Dec. 28, 1990, while he was being brought to the Delaware County Jail on a charge of public intoxication. A police officer who patted Lambert down did not find the gun he had in his pocket. Lambert shot Winters five times in the head, and the officer died 11 days later.

Lambert is the second person to be executed under the new law that gives up to eight spots to immediate family members of murder victims. Last month, five adult children of Juan Placencia watched as David Leon Woods was executed.

Terry Winters was the only relative who asked to witness the execution that will be by lethal injection. Gregg Winters’ widow, Molly, did not want to watch but planned to be at the prison. “I was with Gregg those 11 days that he was laying there fighting for his life,” she said. “And I was there when he took his last breath and died. That is a memory that will always be in my mind. I will not give Michael Lambert the privilege of knowing he will always be forever in my memories right next to Gregg. I’m not doing it.”

A federal appeals court temporarily blocked Lambert’s 2005 execution. It later lifted that order, and the U.S. Supreme Court for a fourth time declined to review his case.

He then filed another appeal with the Indiana Supreme Court, which it denied last month and set the new execution date. Lambert again argued that his death sentence should be overturned because the state’s high court had held that the jury in his case was improperly exposed to victim impact evidence.

"Indiana executes man who killed cop while drunk," by Karen Murphy. (Fri Jun 15, 2007 2:54AM EDT)

MICHIGAN CITY, Indiana (Reuters) - The state of Indiana on Friday executed a man who killed a police officer after he was arrested for public drunkenness more than 16 years ago. Michael Lambert, 36, was pronounced dead at 12:29 a.m. CDT (1:29 a.m. EDT, 0529 GMT) after an injection of lethal chemicals, officials at the Indiana State Prison said.

Lambert had lost a series of final court appeals and was denied clemency by both the state parole board and Gov. Mitch Daniels.

He was convicted of killing Gregg Winters, a city policeman in Muncie, Indiana, in December 1990. Winters took him into custody for public drunkenness. Sitting in the back of Winters' squad car, Lambert pulled a gun he had concealed and shot the officer, a 32-year-old father of two, five times in the back of his head.

Winters' brother, Terry Winters, the deputy chief of the Muncie police department, witnessed the execution. Roughly a hundred other police officers held a candlelight vigil outside the prison.

Lambert had been given a kitten while on death row, which he left to his son. The kitten was three months old.

Lambert was offered a meal of his choosing on Wednesday night but declined the offer. He has contended he didn't know what he was doing when he killed Winters because he was drunk.

He met with a spiritual advisor on Thursday but had no final statement.

His was the 23rd execution in the United States this year, the second in Indiana in 2007 and the 1,080th since the death penalty was restored in the United states in 1976.

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

Michael Lambert, June 15, IN

Do Not Execute Michael Lambert!

The state of Indiana is scheduled to execute Michael Lambert on June 15 for the December 1990 murder of Officer Gregg Winters.

Indiana should not execute Lambert for his role in this crime. Executing Lambert would violate the right to life as declared in the Universal Declaration of Human Right and constitute the ultimate cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment. Furthermore, the jury may have been exposed improperly to victim impact evidence, and the defense did not present a full mental history of Lambert during their mitigation argument. Currently, Lambert is a party in a federal lawsuit challenging the legality of the state’s lethal injection protocol.

Please write to Gov. Mitch Daniels on behalf of Michael Lambert!

Lambert v. State, 643 N.E.2d 349 (Ind. 1994) (Direct Appeal).

Defendant was convicted in the Delaware Superior Court, Division 1, Robert L. Barnet, Jr., J., of murder of police officer, was sentenced to death, and he appealed. The Supreme Court, Givan, J., held that: (1) jury panel was properly drawn; (2) prosecution could qualify jury to consider death penalty; (3) defendant's statement to police was intelligent and voluntary; (4) trial court did not abuse its discretion in admitting videotaped demonstration of how handcuffed defendant could have shot police officer; (5) no aggravating situation existed which could have justified instruction on voluntary manslaughter; (6) instruction on jury recommendation for sentencing correctly advised jury of their advisory role; (7) defendant waived issue of whether trial court properly admitted victim-impact evidence; and (8) trial court properly weighed aggravating and mitigating factors in determining death sentence. Affirmed. DeBruler, J., concurred in result in part and dissented in part and filed opinion in which Sullivan, J., joined.

GIVAN, Justice.

Upon conviction of the murder of a police officer, appellant received the death penalty. Oral argument was held in this cause on June 3, 1993. The State conceded the trial court applied the wrong standard in determining intoxication is not a mitigator; therefore, this Court ordered the case remanded to the trial court to reconsider evidence of intoxication and its effect on the penalty in view of Ind.Code § 35-50-2-9(c)(6). The trial court has returned its findings and judgment as per our Order and the parties have filed their respective briefs pertaining thereto.

The facts are: During the afternoon of December 27, 1990, appellant consumed several alcoholic drinks. At approximately 8:00 p.m., he went to the 300 Club Bar on the south side of Muncie, Indiana where he consumed additional alcoholic beverages. His conduct there was described as “radical” and “dancing around wild-eyed.” A little after 1:00 a.m., on December 28, 1990, Muncie Police Officers were dispatched to a property-damage accident. When they arrived, they observed a utility truck with the name “Jim Allen's Service Maintenance” painted on the side. Shirts inside the truck bore the name “Mike.” The driver could not be found and the truck was towed.

A short time later, Officer Kirk Mace observed appellant trying to crawl under a car. When Officer Mace investigated, appellant told him he was going to sleep under the car. He was lightly dressed, it was snowing and the temperature was in the teens. The officer concluded that appellant was intoxicated and placed him under arrest for public intoxication. Appellant was subjected to a “quick pat-down search,” was handcuffed, and was placed in the back of the police car. Then, Officer Gregg Winters, with only he and appellant in the police car, started driving to the jail which was approximately fifteen minutes away.

A few minutes later, Deputy Sheriff Mike Scroggins and Deputy Greg Ellison were driving their patrol cars east on Riggins Road when they observed a westbound car approaching. It suddenly slid off the road, coming to rest against a fence in a ditch. As the car went into the ditch, the officers were able to observe that it was a police car. They observed Officer Winters immobile behind the steering wheel and appellant in the back seat of the car. It was discovered that Officer Winters had suffered gunshot wounds to the back of the head and neck, and although appellant was handcuffed, there was a .25 caliber pistol lying on the floor of Winter's police car. Ballistics tests later established the weapon was used to inflict the wounds on Officer Winters. It also was learned later that appellant had stolen the pistol from his employer.

Six empty cartridge casings were located in the car and five slugs were recovered, one from the body of Winters during the autopsy, two from the front seat of the car, one from Winters' clothing at the hospital, and one which was lodged between the dash panel and the left pillar of the car. An autopsy revealed that Officer Winters in fact had been struck by five separate bullets.

Despite the fact appellant was handcuffed at the time, he apparently was able to recover the pistol from his clothing and fire the shots into the back of the head and neck of Officer Winters. Police conducted a demonstration to determine if such an act was possible. The demonstration was videotaped and clearly established the fact that a person of appellant's height and weight in fact could accomplish such a feat although it did require a certain amount of physical dexterity.

Appellant claims the jury panel was improperly drawn and that the system used by Delaware County to obtain prospective jurors uses the voter registration lists only and thus is in violation of Ind.Code § 33-4-5-2(a), which requires a list of prospective jurors be chosen from not only the list of legal voters in the county but also the latest tax schedules of the county.

Appellant concedes that this procedure was approved in Rogers v. State (1981), Ind.App., 428 N.E.2d 70. Appellant argues that in 1989 the legislature amended Ind.Code § 33-4-5-7 to eliminate the requirement that a person be a resident voter in order to be qualified for jury duty and in retaining the language in Ind.Code § 33-4-5-2(a) that the jury panel be drawn both from the voter registration list and the tax schedules, further provided that potential juror lists could be expanded beyond those persons to include various other groups.

Appellant takes the position that when the legislature undertakes to amend a statute it is presumed to be aware of prior language and the Court interpretation of the statute. Thus, the prior holding in Rogers that a drawing from either registered voters or property owners would be proper was altered by the statutory amendment. Henceforth, it is required that both voter registration and tax schedules lists be used in drawing potential jurors.

In order to show reversible error in the manner in which prospective jurors are chosen, an appellant must show a common thread running through the excluded group, showing that the exclusion was such as to prevent juries from being made up of a certain segment of the population of the community. See Moore v. State (1981), Ind.App., 427 N.E.2d 1135. In the case at bar, appellant in effect is arguing that property owners who are not registered voters would have been excluded. However, there is no showing that property owners as a group were excluded from the jury. As the State points out, many property owners in fact are registered voters and there is no showing here that a jury was made up entirely of registered voters only and excluded property owners. Under the circumstances of this case, the observations made by the Court of Appeals in Rogers are still valid and applicable to the case at bar. We see no reversible error in the manner in which the jury was chosen.

Appellant claims the trial court erred in denying his motion for change of venue or venire. The record here amply demonstrates that this case received a high degree of publicity not only in Delaware County but throughout the entire state. During voir dire examination, the jurors were questioned extensively concerning the knowledge they had gained of the case through news media or any other source. Each person who eventually was chosen and served on the jury was able to state that although they had read accounts of the incidents leading to appellant's trial, they would be able to make their determination based solely on the evidence heard in the case and would follow the instructions of a trial court. This was in keeping with our holding in Davidson v. State (1991), Ind., 580 N.E.2d 238.

We would further point out that appellant did not exhaust his peremptory challenges which would be a prerequisite to demonstrating that he was subjected to a biased panel. Reinbold v. State (1990), Ind., 555 N.E.2d 463. There is no evidence in this record to support appellant's claim that the trial court erred in denying his motion for change of venue or change of venire.

Appellant contends that allowing the State to proceed to seek a “death-qualified” jury subjected him to a trial by a “guilt-prone” jury. Appellant concedes that both the Supreme Court of the United States and the Supreme Court of Indiana have held that death qualification is not unconstitutional. See Lockhart v. McCree (1986), 476 U.S. 162, 106 S.Ct. 1758, 90 L.Ed.2d 137; Fleenor v. State (1987), Ind., 514 N.E.2d 80, cert. denied, 488 U.S. 872, 109 S.Ct. 189, 102 L.Ed.2d 158. However, he urges us to reconsider this line of cases in light of Georgia v. McCollum (1992), 505 U.S. 42, 112 S.Ct. 2348, 120 L.Ed.2d 33. We do not find that case on point here. McCollum holds that the prosecution is barred from exercising peremptory challenges in a racially discriminatory manner.

We find that both the United States Supreme Court and this Court still adhere to the proposition that it is proper to qualify a jury concerning their willingness to give the death penalty. Appellant argues that McCollum stands for the proposition that excluding any class of persons from a jury deprives those persons of their rights and undermines the fairness of the judicial system. However, when persons state they cannot perform their duties as required by law because of their personal convictions, they cannot qualify for jury service in that particular case. See Utley v. State (1992), Ind., 589 N.E.2d 232, cert. denied, 506 U.S. 1058, 113 S.Ct. 991, 122 L.Ed.2d 142. We continue to hold that it is valid for the State to qualify a jury to consider the death penalty.

Appellant claims the trial court erred in denying his motion to suppress his statement to police and admitting that statement in evidence at trial. Appellant contends he was so intoxicated at the time he was arrested and questioned that he was incapable of knowingly and freely waiving his right against self-incrimination; therefore, his statement to police was not admissible. There is no question that a person may be so intoxicated that he is incapable of giving a knowingly voluntary statement to police. See Thomas v. State (1983), Ind., 443 N.E.2d 1197. We have held that a defendant's statement will be deemed incompetent only when he is so intoxicated that it renders him unconscious of what he is doing or produces a state of mania. A lesser degree of intoxication affects only the weight and not the admissibility of his statement. Houchin v. State (1991), Ind., 581 N.E.2d 1228.

Officer Stanley testified that when he started taking appellant's statement at 4:05 a.m. on December 28, appellant appeared to be oriented as to time and place and did not slur his words. He said appellant stated to him that he understood what was going on and that he was able to recount events in a logical order and sequence. Appellant stated that he had “a buzz on” but he was not drunk and knew what he was saying. Captain Cox testified that he detected an odor of alcohol; however, he observed appellant walking and he did not wobble or stumble. Although there was an odor of alcohol on appellant, he did not demonstrate any of the other signs of intoxication. Samples of appellant's signature affixed to his statement to the police and his signature taken at other times were compared for their similarity.

A breathalyzer test given to appellant at 5:15 a.m. showed he tested a blood alcohol level of .18 percent. We have held that if a defendant appears to be able to talk clearly and understand what he is saying even though he tests high in blood alcohol content, his statement will be admissible. See Gregory v. State (1989), Ind., 540 N.E.2d 585. The evidence in this case supports the trial court's finding that although intoxicated, appellant had the ability to render an intelligent and voluntary statement to the police.

Appellant contends the trial court erred by allowing in evidence a videotape of a staged “reenactment” of the crime. Because of the obvious difficulty of a person who was handcuffed obtaining a weapon from his clothing and firing five shots into the back of an officer's head, the State chose a person of appellant's height and weight to demonstrate such a possibility. In several tries, the demonstrator was able to produce a gun from several locations in his clothing with the exception of his right coat sleeve. He not only was able to produce the weapon but able to demonstrate his ability to fire it in the direction of a person seated behind the wheel of the automobile. Demonstrations are admissible subject to a trial court's discretion. On review, we will reverse only for an abuse of that discretion. Peck v. State (1990), Ind., 563 N.E.2d 554.

Appellant cites Peterson v. State (1987), Ind., 514 N.E.2d 265 for the proposition that in making a determination to permit a demonstration, the court should consider: 1) the ability to make a faithful record of the drama for appeal purposes; 2) the degree of accuracy in the recreation of the actual prior condition; 3) the complexity and duration of the procedure; 4) other available means of proving the same facts; and 5) the risk which the conduct of such procedure may pose to the fairness of the trial. In this case, it is obvious the ability to restage the action was exceedingly simple.

The police officer and appellant were the only two people in the automobile-the police officer behind the wheel and appellant handcuffed in the back seat. There is obviously very little variation that could have occurred. There is obviously nothing complex about such a procedure. The murder weapon was found on the floor of the car and it was established that it had been stolen from appellant's employer. The demonstration clearly showed the ability for a handcuffed person to produce and fire the gun in such a manner as was necessary to inflict the wounds on the officer. We see no violation of the trial court's discretion in permitting the videotape of the demonstration to be shown to the jury.

Appellant claims the trial court erred in refusing to read appellant's Final Instructions Nos. 9 and 10 on voluntary manslaughter as a lesser-included offense. Appellant contends he was too drunk to form the necessary intent to kill. This Court has held previously that voluntary manslaughter requires intent, whereas the defense of intoxication, if accepted, requires an acquittal because of lack of the ability to form intent. It does not justify a conviction on a lesser-included offense. Rowe v. State (1989), Ind., 539 N.E.2d 474; McCarty v. State (1986), Ind., 496 N.E.2d 379.

In the case at bar, appellant was arrested while trying to crawl under an automobile to sleep. When the officer discerned that he was intoxicated, he was arrested, handcuffed, and placed in the back seat of a squad car. There was nothing unusual about his arrest nor was there any confrontation with the police in regard thereto. There is no evidence that he was abused in any way or that he was discernibly angered in any way. There is nothing about the facts in this case that would justify a finding that appellant was subjected to an aggravating situation provoking sudden heat which would be an element to consider so far as a voluntary manslaughter instruction would be concerned. The trial court did not err in refusing to give a voluntary manslaughter instruction.

Appellant claims the trial court erred by modifying his proposed Final Instruction No. 1 regarding the effect of the jury recommendation concerning the death penalty during the penalty phase of the trial. The trial judge modified appellant's Tendered Instruction to read in part: “A jury recommendation is to be given a special role in a judge's process of determining punishment, because it represents the collective conscience of the community.” He claims his instruction should have been given unmodified because nowhere else were the jurors told of the great weight and very serious consideration which would be given to their recommendation and sentencing.

In Drollinger v. State (1980), 274 Ind. 5, 408 N.E.2d 1228, this Court noted that an instruction need not necessarily be read to the jury because it is a correct statement of the law. “The mere fact that certain language or expressions are used in the opinions of this Court to reach its final conclusion does not make it proper language for instructions to a jury.” Id. at 25, 408 N.E.2d at 1241.

The trial court correctly advised the jury of their advisory role. Bellmore v. State (1992), Ind., 602 N.E.2d 111, 125. The instruction tendered by appellant focused only on one possible recommendation and would have encouraged the jury to try to gauge the legal consequence of their recommendation rather than to consider what on the evidence their recommendation should be. The modification by the trial court was proper. There was no error.

Appellant claims the trial court erred in allowing the State to present victim-impact evidence during the penalty phase of the trial and failing to strike the victim-impact statements from the presentence investigation report. In Bivins v. State (1994), Ind., 642 N.E.2d 928, a majority of this Court, construing our state constitution, adopted a new rule of criminal procedural law constraining the available aggravating circumstances to those designated by the capital sentencing statute. The Bivins majority applied this new rule to hold that victim-impact evidence would be improper unless relevant to one of the statutory capital aggravators. This new rule applies in pending cases on direct appeal if the issue is properly preserved. In the present appeal, the defendant asserts error in the admission of victim-impact evidence only on grounds that it is contrary to Indiana statutes concerning the probation officer's presentence investigation. Ind.Code § 35-38-1-8.5(A). Because the defendant's appeal does not present the legal claim upon which Bivins was decided, we deem such issue to be waived. Appellant concedes that the United States Supreme Court has held in Payne v. Tennessee (1991), 501 U.S. 808, 111 S.Ct. 2597, 115 L.Ed.2d 720 that the Eighth Amendment does not prohibit the introduction of such evidence. He further concedes that this Court has followed Payne. Roche v. State (1992), Ind., 596 N.E.2d 896; Benirschke v. State (1991), Ind., 577 N.E.2d 576, cert. denied, 505 U.S. 1224, 112 S.Ct. 3042, 120 L.Ed.2d 910. We find no reversible error here.

Appellant contends the trial court erred at sentencing by finding and considering aggravating circumstances not supported by the evidence and failing to find and consider mitigating circumstances supported by the evidence. He further claims the trial court applied the wrong standard to the evidence of intoxication and in finding that the aggravating factor of the killing of a police officer in the line of duty outweighed the mitigating factors. As previously stated in this opinion, this case was remanded to the trial court for consideration of the possible mitigator of intoxication.

In responding to that remand, the trial court has presented a lengthy and detailed evaluation of each possible aggravator and each possible mitigator which he considered in rendering the sentence. He carefully analyzes each aspect of the claim of appellant's intoxication and finds that he in fact was intoxicated at the time the crime was committed and that he was intoxicated to the extent that it impaired his ability to reason. However, he further found that: “[Appellant's] capacity to conform his conduct to the requirements of the law was not substantially impaired as a result of intoxication, mental disease, or defect. The Defendant was able to conform his conduct to those requirements.

A closer question is whether or not [his] capacity to appreciate the criminality of his conduct was substantially impaired as a result of mental disease or defect or of intoxication.”

The court went into detail concerning appellant's age-which was 20 years, his level of intoxication, his family history, his prior exposure to alcohol, and the impact the alcohol had on his judgement. He held that these factors should be considered as mitigators and should be considered together with the aggravators in coming to a conclusion as to the sanction to be imposed. The careful detail given by the trial court in response to our remand is to be commended. In the vernacular, we observe he did not “leave a stone unturned.”

He carefully points out the evidence as to appellant's degree of intoxication, the absence of any aggravating circumstance, the total wantonness of appellant's conduct in deliberately firing five shots into the back of the head and neck of an officer who had in no way abused him. The trial court did observe that appellant had shown some signs of possible rehabilitation and he claimed that he already had started on such a program.

This case is very similar to the case of Johnson v. State (1992), Ind., 584 N.E.2d 1092, cert. denied, 506 U.S. 853, 113 S.Ct. 155, 121 L.Ed.2d 105. The ages of Johnson and appellant were the same. They both were intoxicated at the time they committed murder. In Johnson's case, he fatally bludgeoned an 82-year-old woman to death after breaking into her home. In the case at bar, the officer was shot from the back with no opportunity to defend himself.

In both cases, lack of guidance in upbringing and intoxication were urged as mitigating circumstances. However, in Johnson as in the case at bar, those contentions were to no avail at the trial level. The court in Johnson relied on our holding in Woods v. State (1989), Ind., 547 N.E.2d 772, cert. denied, 501 U.S. 1259, 111 S.Ct. 2911, 115 L.Ed.2d 1074, where the defendant attempted to rely on the fact of a turbulent childhood marked by mistreatment as a mitigator. As in both Johnson and Woods, we find appellant's claims that mitigators should override the aggravators and that the death penalty should not be invoked are to no avail.

The trial court is affirmed. SHEPARD, C.J., and DICKSON, J., concur. DeBRULER, J., concurring in result and dissenting with separate opinion in which SULLIVAN, J., concurs.

DeBRULER, Justice, concurring in result and dissenting.

1. Over objection at trial the judge admitted a videotape in which appeared a male officer whose hands were handcuffed behind his back. This officer moved and tossed about and managed to position his hands and body in a manner which would have permitted him to remove a handgun from the back of his pants, place it on the driver's head rest and yell “bang, bang.” This ruling was error. The standard governing the admissibility of such matter given in Peterson v. State (1987), Ind., 514 N.E.2d 265, was not met. First, there was no necessity for the employment of this method by the prosecution in proving its case. The jury was in a perfect position to judge whether appellant was able to draw, point, and fire the fatal shots while handcuffed. Such judging is everyday fare for triers of fact. Second, this visual portrayal is pure theater. It was written, produced, directed, and casted by the prosecuting agents of the government. It has emotional content and impact upon the viewer far beyond the abstract message it carried that appellant could have drawn, pointed and fired. The film was manufactured outside the courtroom. It was shown to the jury on a screen using expensive and technologically sophisticated machinery. There was undoubtedly a hushed atmosphere in the courtroom. The attention of the jury was undoubtedly focused in that special manner which accompanies theater and television viewing. It is impossible to conceive of a process posing a greater threat to the fairness of judicial proceedings. This particular film and its genre, as evidence, have no part in court and must be condemned in the strongest terms.

As has oft been noticed, it is not every error which requires remedy. Under the unique circumstances of this case, the error admitting this film was harmless at the guilt/innocence stage of the trial. Additional facts supporting the verdict show that when deputy sheriff Scroggins and deputy Ellison reached the car, the motor was running, the car was in drive, and the victim Winters was behind the wheel with his foot still on the accelerator. Appellant was in the back with the murder weapon. Winters was dying of multiple bullet wounds. Winters' gun was still secure in its holster. The risk that the jury gave significant weight to the erroneously admitted film in determining guilt or innocence is de minimus. Since I regard the ruling of the trial court to be error, I concur in result only in that part of the majority opinion affirming the conviction.

2. With respect to sentencing, I dissent and vote to set aside the sentence of death and order the imposition of a term of years. The trial court was in error in permitting Chief Scroggins over an Eighth Amendment objection to testify that as a direct result of the murder of Officer Winters he was unable to function at an appropriate level as chief, and had to seek medical help and take prescription drugs. He also testified that some officers as a direct result of the murder of Officer Winters began acting in a violent and illegal way in dealing with the public in the course of their duties.

The holding of the Supreme Court in Payne v. Tennessee, 501 U.S. 808, 111 S.Ct. 2597, 115 L.Ed.2d 720 (1991), does not write the Eighth Amendment out of the issue of whether victim impact evidence is admissible during the penalty phase of a capital trial. After Payne, some victim impact evidence is admissible and some is not. In Payne the Supreme Court approved the prosecutor's use of a grandmother's testimony describing the sense of loss of her grandchild who himself managed to survive the same murderous attack which had taken the lives of his mother and sister. The child was a survivor of the very crime for which the death penalty was sought. I do not believe the Eighth Amendment, as interpreted by the Supreme Court in Payne, would permit a state to include a police chief or a police department among the survivors of crime for the purpose of admissibility. Clearly, only three Justices in Payne regard such large entities and the community as a whole as survivors for this purpose.

In its final order, the trial court added weight to the death aggravator based upon the “terrible effect” which this killing had on other officers. In so doing, it is evident that the trial court was moved by the testimony of Chief Scroggins and inferences therefrom to add weight on the aggravator side of the scales. This was federal constitutional error and contrary to law.

3. In its final order, the trial court's final reason for choosing death was that under the circumstances of the case the “... imposition of the death penalty is supportable and the Court now accepts the recommendation of the jury.” I continue to regard this type of reasoning as inconsistent with the requirement that the judge adjudicate the propriety of the sentence of death.

4. Finally, it is important to consider the distinctions between the circumstances of this case and those present in Johnson v. State (1992), Ind., 584 N.E.2d 1092, cert. denied, 506 U.S. 853, 113 S.Ct. 155, 121 L.Ed.2d 105 (1992) and Woods v. State (1989), Ind., 547 N.E.2d 772, cert. denied, 501 U.S. 1259, 111 S.Ct. 2911, 115 L.Ed.2d 1074 (1991), in which the death penalty was affirmed by this Court on appeal. In both those cases, as in this case, the defendant was under the lawful drinking age, and killed while intoxicated. There the similarities end. Both Johnson and Woods planned to rob a lone elderly person at home, and in executing such plans held weapons for use against the intended victims. Appellant did not plan to kill officer Winters and arm himself for that purpose. His design to kill and escape was made under a high state of intoxication, after having been handcuffed and confined in a small space. The weight of the aggravators in Johnson and Woods is greater. SULLIVAN, J., concurs.

Lambert v. State, 675 N.E.2d 1060 (Ind. 1996) (Direct Appeal Rehearing)

Defendant was convicted in the Delaware Superior Court, Robert L. Barnet, Jr., J., of murdering a police officer, and was sentenced to death. Defendant appealed. The Supreme Court, Givan, J., 643 N.E.2d 349, affirmed. Defendant petitioned for rehearing. The Supreme Court, Selby, J., held that: (1) defendant preserved relevancy objections to victim impact testimony on appeal; (2) victim impact testimony was inadmissible; (3) erroneous admission of victim impact testimony was not harmless; but (4) death sentence was warranted nonetheless. Petition granted; affirmed in part and reversed in part. Boehm, J., filed dissenting opinion.

SELBY, Justice.

This is a petition for rehearing of this Court's decision to affirm the trial court's sentence of death in Lambert v. State, 643 N.E.2d 349 (Ind.1994). Lambert was tried, convicted, and sentenced to death for the murder of a police officer. As a result of Lambert's initial direct appeal, and by stipulation of the State, this Court remanded the case to the trial court to reconsider evidence of Lambert's intoxication and its effect as a mitigator under Ind.Code Section 35-50-2-9(c)(6). After reconsideration of the intoxication mitigator, the trial court again sentenced Lambert to death. This Court affirmed that sentence on direct appeal. Lambert v. State, supra. Lambert now petitions for rehearing, raising multiple issues. We grant his petition for rehearing solely on the issue of the admissibility of certain victim impact testimony at the sentencing phase of the trial.

On direct appeal, we deemed that the issue of the admissibility of victim impact testimony was waived. We reasoned that Lambert had “assert[ed] error in the admission of victim-impact evidence only on grounds that it is contrary to Indiana statutes concerning the probation officer's presentence investigation[,] Ind.Code Section 35-38-1-8.5(a)[,]” and therefore he had waived his relevancy objection to the admission of this evidence. Lambert, 643 N.E.2d at 354 (emphasis added).

Lambert notes in his Petition for Rehearing that the objections which he made at trial regarding the admission of this evidence were not limited to statutory concerns. Rather, Lambert consistently objected to the admissibility of the evidence on the grounds that it was irrelevant. For example, he introduced a Motion to Exclude Victim Impact Evidence, and he continually objected to the admission of victim impact evidence during the penalty phase on the basis that this victim impact evidence constituted irrelevant aggravators. Also, in his brief on direct appeal, Lambert argued that the extensive victim impact testimony goes “far beyond the ‘quick glimpse’ ” of the victim's life and the impact of the crime permissible under Payne v. Tennessee, 501 U.S. 808, 111 S.Ct. 2597, 115 L.Ed.2d 720 (1991). (Brief for Appellant at 9, 25.) Additionally, Lambert objected to the jury's recommendation because it had been tainted by the extensive victim impact testimony. Thus, a review of the record indicates Appellant did raise relevancy objections to the victim impact testimony at trial and did adequately, though perhaps imprecisely, preserve his objections on appeal. We grant his Petition for Rehearing to review those objections.

FACTS

While Lambert v. State contains a full recital of the facts, we will briefly restate them here. During the afternoon of December 27, 1990, Michael Allen Lambert, then a twenty-year-old man, began consuming alcohol. At approximately 8:00 p.m., he went to a bar in Muncie, Indiana where he continued drinking. A little after 1:00 a.m., on December 28, 1990, Muncie police officers were called to an accident scene. At the scene, an officer discovered Lambert attempting to crawl under a car. When confronted, Lambert explained that he was crawling under the car to go to sleep. The police arrested Lambert for public intoxication. They cuffed Lambert's hands behind his back, gave him a brief pat-down search, and then placed him in the back seat of Officer Gregg Winters' police car. Officer Winters began driving Lambert toward the police station.

A few minutes later, two officers noticed Officer Winters' vehicle approaching them. They then saw Officer Winters' vehicle suddenly slide off the road and into a ditch. Upon investigation, they found Officer Winters with five .25 caliber firearm wounds to the back of his head and neck. Lambert was seated in the back of Officer Winters' police car, and a .25 caliber pistol was laying on the patrol car's floor. Lambert's arms remained handcuffed; his hands, when later examined, showed traces of having been within six inches of the firing of a firearm. The pistol proved stolen from his employer.

At the sentencing phase of the trial, the State presented victim impact testimony in support of the death penalty. Lambert objects to the testimony of three witnesses as improper victim impact testimony: Muncie Chief of Police Donald Scroggins; Officer Terry Winters, a Muncie police officer and the victim's brother; and Molly Winters, the victim's wife.

The court first permitted Chief Scroggins to testify, over Lambert's relevancy objections, about the effect that Officer Winters' death had both on Chief Scroggins personally and on the members of the Muncie Police Department. Chief Scroggins was permitted to testify that at Officer Winters' funeral over twenty different police agencies were represented, and that the Department had received cards and letters from police departments all over the country. He testified that he and other members of the department had sought psychological counseling to cope with Officer Winters' death, and that after the shooting, because he was unable to function as he felt a Chief of Police should, he contacted his physician for prescription medication.

The court next heard from Officer Terry Winters, the victim's brother. Officer Winters testified, over defendant's continued relevancy objections, that his brother had loved being a policeman, and that his brother's death had adversely affected Officer Terry Winters' job performance and attitude toward his job. Officer Winters testified about his other brothers' employment, his father's place of employment, and his mother's place of employment.

Next, Molly Winters, the victim's widow, provided penalty phase testimony regarding her relationship with Officer Gregg Winters. She too testified over defendant's continued objections. She stated that they had been married for six-and-a-half years and that they had two sons, Kyle and Brock, ages four-and-a-half years and twenty months old, who liked sports, roughhousing and bike riding. She was permitted to lay a foundation for admission into evidence of a photo of the family taken the previous Christmas. She testified that Officer Winters was a good father and husband. She further testified that he was a dedicated officer who loved his job, and that she had encouraged him to buy and wear a bullet-proof vest prior to the time that vests were issued by the department. “I told him ... I want you to get a vest and to wear it for added protection because I'm worried about you. I want to make sure that every night that you go to work, you come home safe, and I've got two little babies, and I don't want to raise them by myself.” Molly Winters then related the events that occurred between the time of Officer Winters' shooting and his death eleven days later:

State: He survived 11 days, is that correct? Mrs. Winters: That's correct. State: Did your boys get to see him in the hospital before he died? Mrs. Winters: Yeah. I had a couple of doctors that told me don't subject them to that. But I told them they were wrong because it was very important to me that my children know that Daddy went to work. He did his job, and, as we put it, a bad guy got him. And we don't know the outcome, but Daddy is hurt very badly, and we could go and see him and talk to him, but he just can't talk to us. State: Did the boys go and see him? Mrs. Winters: I took them back, and I stayed out in the hallway, and I explained to my oldest son, Kyle, what was going on because the baby was nine and a half months and he didn't know. And I said, if you want to touch Daddy, you can, but you don't have to. So we went on in. When we went in, he asked me numerous questions, you know about the machines and different things, and then he said, Mommy, can you do me a favor? And I said yeah. He said, can you tell Daddy I love him? And I said, yeah, I can do that. And I said, do you want to hug Daddy or kiss him? And he said, no, I better not right now, but I will later. And he said, Daddy, you have good dreams.

So we went out, and then I had Kyle with me the entire time I was in the hospital with Gregg. And every time he asked about his daddy or wanted to see his daddy or tell his daddy something, I took him in. And the night that we lost Gregg, they moved him to the hospice floor. And when he died, it was more of a homey atmosphere, and I took Kyle in ‘cause we had open visitation, and most of the machines were gone, and the sterile atmosphere was gone, and he climbed up on the bed next to Gregg, and he talked to him for the first time without telling me to tell him things. And he said, I love you, Daddy. And then there was a big window in his room, and Gregg and Kyle, they always went places together. They would dress alike a lot of times. They would go to the bypass and look for semis that they could pass. State: Did they have identical jogging suits? Mrs. Winters: Yeah, yeah. They had a couple of identical outfits. State: Kind of a tradition about McDonald's restaurants?

Mrs. Winters: Yes, yes. They would put their outfits on on payday, and Gregg would take him with him to get his check, and they'd go to the bank, and then it was a boy's day out. They would go to McDonald's on Madison Street, and they would sit at the bar, and they would have lunch together. And when I had Brock, there were several times that Gregg took Brock, but before they would leave when they didn't take Brock, they would tell him, Brockie, now when you get to be a big boy like Kyle, you get to go too. When you can start eating, then you can have some of my french fries, Brockie, you can go with us. (R. at 5867-70.) Molly Winters concluded her testimony by advising the jury that Officer Winter's nickname was “Goose” and that she considered him to be a hero. As noted previously, Lambert objected to the admission of this victim impact testimony. Specifically, Lambert sought to exclude the testimony as not relevant to proof of the “aggravating circumstance alleged; that being that Gregg Winters was a police officer acting in the course of his duty at the time that he was killed.” (R. at 5826.) At the penalty phase of the trial, the trial court, citing Payne v. Tennessee, permitted the State to present its victim impact evidence.

* * *

Because this court cannot say with assurance that the erroneously admitted victim impact evidence did not affect the jury's decision to recommend a death sentence, we hold that the admission of such evidence was not harmless error. On independent reweighing of the statutory aggravators and mitigators, we affirm the trial court's death sentence. SHEPARD, C.J., and DICKSON, and SULLIVAN, J.J., concur.

BOEHM, Justice, dissenting.

I concur in the majority's conclusion that the trial court erred in receiving the heartrending testimony ably described in the majority opinion. However, I respectfully dissent from the majority's imposition of the sentence in this case. I do so not because I disagree with the result reached by the majority, based on the information available to me. Rather, I dissent because I do not believe it is customary for this or any appellate court to originate a sentence as opposed to reviewing and revising a sentence imposed by the trial court. There may be circumstances where that action is appropriate, but this is not one of them.

Lambert v. State, 743 N.E.2d 719 (Ind. 2001) (PCR)

Following final appellate affirmance, upon rehearing, of his murder conviction and death sentence, 675 N.E.2d 1060, petitioner sought post-conviction relief. The Superior Court, Delaware County, Robert L. Barnet, Jr., J., denied petition, and petitioner appealed. The Supreme Court, Sullivan, J., held that: (1) its reweighing of aggravating and mitigating factors on rehearing in petitioner's direct appeal was proper; (2) trial and post-conviction judge's statements during sentencing did not demonstrate disqualifying bias; (3) presence of uniformed, armed police officers in courtroom during trial did not render trial judge incapable of making impartial findings in post-conviction proceedings; (4) defendant's trial counsel was not ineffective for failure to keep out evidence, object to prosecutor's statements, proffer or object to jury instructions, or investigate defendant's claims of mental disorder; (5) defendant's appellate counsel was not ineffective for failing to present particular issues and claims on appeal; (6) state's failure to disclose evidence with purported impeachment value was harmless; (7) any error resulting from sentencing court's reliance on misleading or unreliable testimony was rectified by Supreme Court's reweighing of aggravators and mitigators on rehearing; and (8) petitioner's numerous freestanding claims of trial court error were unavailable on post-conviction review. Affirmed.

Lambert v. McBride, 365 F.3d 557 (7th Cir. 2004) (Habeas)

Background: Following affirmance of his state court murder conviction and death penalty, 675 N.E.2d 1060, and denial of postconviction relief, 743 N.E.2d 719, petitioner sought writ of habeas corpus. The United States District Court for the Southern District of Indiana, Larry J. McKinney, Chief Judge, denied relief, and petitioner appealed.

Holdings: The Court of Appeals, Terence T. Evans, Circuit Judge, held that:

(1) Ring rule that death sentence must be based on jury determination did not apply retroactively,

(2) extension of Clemons rule allowing appellate court to rebalance aggravating and mitigating evidence to case involving advisory jury recommendation was not contrary to or unreasonable application of Supreme Court precedent;

(3) counsel was not deficient in failing to object to presence of officers in courtroom;

(4) determination that prosecutor did not commit misconduct in closing was not contrary to or unreasonable application of Supreme Court precedent; and

(5) state court determination that no Brady violation occurred was not contrary to or unreasonable application of Supreme Court precedent.

Affirmed.

TERENCE T. EVANS, Circuit Judge.

Michael Lambert appeals from the denial of his petition for a writ of habeas corpus, pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2254. He does not dispute that his Indiana conviction for the murder of police officer Gregg Winters is valid, but he contends that the death sentence he received was unconstitutionally imposed. The facts are grisly.

Lambert was drinking heavily one December day in 1990. That night, he went to a bar on the south side of Muncie, Indiana, and drank even more. He became drunk; a patron of the bar said he was “dancing around wild-eyed.” A little after midnight, Muncie police were dispatched to a property-damage accident. When they arrived on the scene, they found a truck without a driver.

A short time later, Officer Kirk Mace saw a man trying to crawl under a car. When Mace investigated, the man, who turned out to be Lambert, said he was going to go to sleep under the car. Lambert was lightly dressed; the outside temperature was in the teens and it was snowing. Mace concluded that Lambert was drunk and arrested him for public intoxication. Lambert was subjected to a quick “pat-down search,” handcuffed, and placed in the back of a squad car. A single officer, Officer Winters, started to drive Lambert to the jail, which was about 15 minutes away. What happened during that short trip ended Winters' life and altered, with a sentence of death, Lambert's life as well.

A few minutes into the trip, a patrol car carrying two deputy sheriffs approached Officer Winters' squad car, which was proceeding from the opposite direction. Suddenly, Winters' patrol car slid off the road and came to rest in a ditch. Why? Well, as revealed during the trial, what happened was chilling.

The “pat-down” search of Lambert had come up dry for weapons, but it was tragically incomplete. Lambert had a gun somewhere on his person, one that he stole from his employer 8 days earlier. During the ride to the jail, Lambert, despite being handcuffed, managed to get the gun and fire shots into the back of Officer Winters' neck and head. When the two deputies got to the scene, Winters was immobile behind the steering wheel and Lambert's pistol was on the floor. An autopsy revealed that Winters was struck by five bullets. He died in a hospital 11 days later.

Lambert was subsequently charged with murder. The charged aggravating circumstance, which made him eligible for the death penalty, was that the victim was a police officer killed in the line of duty. Indiana Code § 35-50-2-9(b)(6). Lambert was convicted by a jury, and the case proceeded to a sentencing hearing before the same jury. During this hearing, under Indiana law, a jury considers “all the evidence introduced at the trial stage of the proceedings, together with new evidence presented at the sentencing hearing.” § 35-50-2-9(d). When these proceedings (prior to the 2002 amendments to the statute) occurred, the judge was not bound by the jury's recommendation, and prior to pronouncing sentence she could receive victim-impact evidence. Indiana Code § 35-50-2-9(e). In this case, however, it was the jury who heard victim-impact testimony-from the police chief, Officer Winters' brother, and from his widow, Molly Winters. The jury recommended a death sentence, which the judge then imposed.

Lambert appealed his conviction and sentence to the Indiana Supreme Court, which remanded the case to the trial court to reconsider evidence of intoxication as it was related to the penalty determination. The trial judge once again sentenced Lambert to death, and this time the Indiana Supreme Court affirmed both the conviction and sentence. Lambert v. State, 643 N.E.2d 349 (Ind.1994). Lambert sought rehearing, arguing that the court was wrong to find that he waived his claim that the trial judge improperly admitted the victim-impact testimony. The Indiana Supreme Court, on rehearing, held that the victim-impact evidence was improperly admitted and that its admission was not harmless error. The court found, however, after itself weighing the factors in aggravation and mitigation, that the death sentence was proper. Lambert v. State, 675 N.E.2d 1060 (Ind.1996). Next, Lambert filed a petition for state postconviction relief in the trial court. After an evidentiary hearing, the court denied relief. Lambert once again appealed to the Indiana Supreme Court, which affirmed the denial of postconviction relief, Lambert v. State, 743 N.E.2d 719 (Ind.2001). A rehearing request was also denied. Along the way, petitions for writs of certiorari were presented to the United States Supreme Court and denied. Lambert v. Indiana, 520 U.S. 1255, 117 S.Ct. 2417, 138 L.Ed.2d 181 (1997); Lambert v. Indiana, 534 U.S. 1136, 122 S.Ct. 1082, 151 L.Ed.2d 982 (2002). Lambert's next stop was the United States district court, where he filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus. The district court denied his petition, and this appeal followed.

Because Lambert's petition was filed after the effective date of the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA), the provisions of that Act govern our review. Lindh v. Murphy, 521 U.S. 320, 117 S.Ct. 2059, 138 L.Ed.2d 481 (1997). Under AEDPA, if a constitutional claim was adjudicated on the merits by the state court, a federal court may grant habeas relief on that claim only if the state court decision was “contrary to” or “involved an unreasonable application of clearly established federal law as determined by the Supreme Court,” or if it was based on an unreasonable determination of the facts in light of the evidence presented in the state court proceeding. 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d). A state court decision is “contrary to” established Supreme Court precedent when the state applies a rule different from governing Supreme Court cases or confronts a set of facts that is materially indistinguishable from those of a Supreme Court decision and arrives at a different conclusion. Williams v. Taylor, 529 U.S. 362, 120 S.Ct. 1495, 146 L.Ed.2d 389 (2000). If the case involves an “unreasonable application” of Supreme Court precedent, we defer to reasonable state court decisions. Bell v. Cone, 535 U.S. 685, 122 S.Ct. 1843, 152 L.Ed.2d 914 (2002). State court factual findings that are reasonably based on the record are accorded a presumption of correctness, and the state court's findings of facts must be rebutted by clear and convincing evidence. 28 U.S.C. § 2254(e)(1); Denny v. Gudmanson, 252 F.3d 896 (7th Cir.2001).

Lambert contends that the Indiana Supreme Court decision, where it reweighed the statutory factors in aggravation and mitigation and then permitted his death sentence to stand, is contrary to or an unreasonable application of Clemons v. Mississippi, 494 U.S. 738, 110 S.Ct. 1441, 108 L.Ed.2d 725 (1990).