16th murderer executed in U.S. in 2012

1293rd murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

3rd murderer executed in Arizona in 2012

31st murderer executed in Arizona since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(16) |

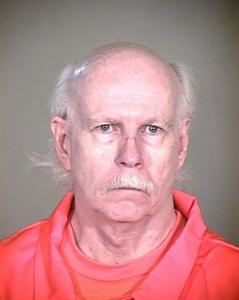

Thomas Arnold Kemp Jr. W / M / 44 - 63 |

Hector Soto Juarez H / M / 25 |

Summary:

College student Hector Juarez was kidnapped by Kemp and his accomplice, Jeffrey Logan, in the parking lot of the apartment complex where he lived. Logan would later report to the police that he and Kemp forced Juarez to withdraw money with an ATM card then drove him to a remote area and shot him. They stole his car then drove to Colorado. At trial, Kemp stated that his biggest mistake was not killing Logan, and that since the victim was a wetback, he did not deserve to live. On the run, the pair would later kidnap a couple in Colorado. When the couple eventually escaped, Logan went to the police. Accomplice Logan was tried first, convicted, and sentenced to life imprisonment for the murder.

Citations:

State v. Kemp, 185 Ariz. 52, 912 P.2d 1281 (Ariz. 1996). (Direct Appeal)

Kemp v. Ryan, 638 F.3d 1245 (9th Cir. 2011). (Habeas)

Final Words:

"I regret nothing."

Final / Special Meal:

A cheeseburger, fries and root beer; boysenberry pie with strawberry ice cream.

Internet Sources:

Arizona Department of Corrections

Inmate: KEMP THOMAS A

DOC#: 099144

DOB: 06/02/1948

Gender: Male

Height 72"

Weight: 170

Hair Color: Gray

Eye Color: Blue

Ethnic: Caucasian

Sentence: DEATH

Admission: 07/20/1993

Conviction Imposed: MURDER 1ST DEGREE

County: PIMA

Case#: 0038226

Date of Offense: 07-11-92

"Arizona executes killer who showed no remorse," by David Schwartz. (Wed Apr 25, 2012 2:52pm EDT)

(Reuters) - A defiant killer who asked for no mercy, shunned a clemency hearing and railed against immigrants at his sentencing was put to death by lethal injection in Arizona on Wednesday for kidnapping and killing a Hispanic college student in 1992, officials said. Thomas Kemp, 63, was pronounced dead at 10:08 a.m. local time at the state prison in Florence, about 60 miles southeast of Phoenix, a state official said. His last words were: "I regret nothing."

Kemp, who acted with an accomplice, was sentenced to death in 1993 for snatching Hector Soto Juarez from outside his Tucson apartment, taking him to a mine northwest of the city and forcing him to disrobe. Juarez was shot fatally in the head. The former trailer park maintenance man had consistently showed no remorse about the killing, and refused to attend a hearing this month by the Arizona Board of Execution Clemency. He branded the proceeding a "dog and pony show."

At his 1993 sentencing, Kemp said his only regret was not killing an accomplice and unleashed a tirade against Mexican immigrants and the legal system, saying his victim was "beneath my contempt." "If more of them wound up dead, the rest of them would soon learn to stay in Mexico, where they belong," Kemp said at his sentencing, according to court documents. "I spit on the law and all those who serve it."

In a statement released shortly after the execution, Arizona Attorney General Tom Horne called Kemp a "particularly cold-blooded individual." "He never expressed any kind of remorse for his crimes, which were particularly brutal," Horne said. "Now that Thomas Kemp has paid the penalty for his terrible crimes, it is my hope that his victims and their families will find some measure of peace that justice has been carried out."

According to court testimony, Kemp and his partner, Jeffrey Logan, set the crimes in motion by buying a .380 semiautomatic handgun from a pawn shop days before the abduction. Late on July 11, 1992, the men took Juarez from the apartment parking lot. At midnight, the two withdrew $200 with Juarez's bank card and drove him to the Silverbell Mine area. Kemp walked his victim 50 to 70 feet from the vehicle, made him take off his clothes and then shot him twice, testimony showed.

His last meal consisted of a bacon cheeseburger with fries, root beer and a piece of boysenberry pie with strawberry ice cream.

AZCentral - The Arizona Republic

"Arizona executes third inmate this year," by Michael Kiefer. (Apr. 25, 2012 10:35 AM)

"Kemp was defiant to the end. "I regret nothing," he said as his last words. Then he trembled as the drugs coursed through his veins, took some deep breaths and went still.

Kemp, 63, was sentenced to death for the July 1992 murder of Hector Juarez.

Kemp was an ex-convict working as a maintenance man at a trailer park in Tucson, where he lived with his mother. When a former prisonmate named Jeffrey Logan escaped from an honor farm in California, he and Kemp teamed up, bought a gun and went cruising for a victim.

They found Juarez, 25, a college student who had left his apartment to get a late-night snack at a fast-food restaurant. Kemp and Logan seized him in the parking lot outside his apartment, made him withdraw money from an ATM, stripped him naked and shot him twice in the head. Then they dumped his body near the Silverbell Mine in Marana, northwest of Tucson.

Kemp and Logan drove to Flagstaff and sold Kemp's truck, then carjacked a couple and forced them to drive to Durango, Colo. where Kemp sexually assaulted the man. The couple escaped and contacted police in Kansas. Logan was arrested in Denver and led Tucson police to Juarez's body in the desert. Kemp was arrested in a homeless shelter in Tucson.

While in jail in Pima County, Kemp effectively confessed to killing Juarez when he told two corrections officers that he was afraid of being housed with Mexican prisoners because he had killed a Mexican.

Kemp was convicted of first-degree murder, armed robbery and kidnapping in June 1993. At his sentencing a month later, Kemp told the court that Juarez was "beneath my contempt" because he was not an American citizen, and, "If more of them wound up dead, the rest of them would soon learn to stay in Mexico, where they belong."

Logan received a sentence of life in prison, which he is serving in Arizona under a different name.

Kemp's last meal was cheeseburger, fries and root beer; boysenberry pie with strawberry ice cream.

"Arizona death-row inmate won't seek mercy." (Associated Press 04/09/12)

PHOENIX - An Arizona inmate set to be executed this month for killing a Tucson college student after robbing him in 1992 has declined to seek mercy from the state's clemency board.

Thomas Arnold Kemp, 63, is set to be executed by lethal injection at the state prison in Florence on April 25.

Daisy Kirkpatrick, an administrative assistant at the Arizona Board of Executive Clemency, told The Associated Press on Monday that Kemp recently declined to petition the board for a lighter sentence.

Kemp's Tucson attorney, Tim Gabrielsen, did not immediately return a call for comment.

Every inmate executed in Arizona has the right to petition the Arizona Board of Executive Clemency to either reduce their sentence to life in prison or delay their execution for more legal wrangling.

No inmates in recent history have declined to seek mercy from the board.

This is not the first time Kemp has refused to argue for leniency for himself.

During his sentencing trial two decades ago, Kemp was supposed to explain to the court why he didn't deserve the death penalty. Instead, he expressed his contempt for his victims, reporters who wrote about the story and the prosecutors on his case.

"I don't show any mercy, and I am certainly not here to plead for mercy," he said. "I spit on the law and all those who serve it."

Kemp was sentenced to death for kidnapping 25-year-old Hector Soto Juarez from outside his Tucson apartment on July 11, 1992, and robbing him before taking him into a desert area, forcing him to undress and shooting him twice in the head.

Juarez had just left his apartment and fiancee to get food when Kemp and Jeffery Logan spotted him. They held him at gunpoint and used his debit card to withdraw $200 before driving him to the Silverbell Mine area near Marana, where Kemp killed Juarez.

The two men then went to Flagstaff, where they kidnapped a married couple traveling from California to Kansas and made them drive to Durango, Colo., where Kemp raped the man in a hotel room. Later, Kemp and Logan forced the couple to drive to Denver, where they escaped. Logan soon after separated from Kemp and called police about Juarez's murder.

Logan led police to Juarez's body, and Kemp was arrested.

Kemp has argued that his conviction was unfair because then-prosecutor Kenneth Peasley repeatedly told jurors that Kemp's homosexuality was behind Juarez's kidnapping and murder, and that the jury hadn't been properly vetted for their feelings about gay men.

Kemp told the judge just before he was sentenced that he should have killed Logan when he had the chance and that he had no regrets.

"The so-called victim was not an American citizen and, therefore, was beneath my contempt," he said and then referred to Juarez using a racial slur for Mexicans. "If more of them ended up dead, the rest of them would soon learn to stay in Mexico where they belong."

"Arizona execution nears for Tom Kemp in 1992 killing," by Michael Kiefer. (Apr. 23, 2012 09:22 PM)

Tom Kemp, who faces execution Wednesday, went to death row for kidnapping and murdering a college student near Marana in 1992. He was, and remains, a hard case. At his sentencing, he said his only regret was not killing an accomplice who turned him in. Kemp did admit to "a deep and abiding sense of remorse," he said, that his friendship kept him from killing the accomplice.

But he had no remorse for killing Hector Juarez, whose naked body he left in the desert near Marana.

At his sentencing, Kemp noted that Juarez was not an American citizen and he offered up a diatribe against Mexican immigrants that made it clear he had no intention of seeking mercy for the killing, telling the court, "I spit on the law and all those who serve it."

Kemp's attorney at the time argued that Kemp had a personality disorder that made him perceive everyone else as dishonest and opportunistic, and therefore moved him to do anything he could to get something for himself.

He still refuses to ask for mercy. He chose not to appear before the Arizona Board of Executive Clemency earlier this month.

In a handwritten note, he said, "I, Thomas Kemp, state that I decline to seek executive clemency due to the futility of that process. In light of the board's history of consistently denying requests for commutations, my impression is that a hearing in my case would be nothing short of a dog and pony show."

There's very little in the record about Kemp, 63. He was born in California in 1948, lived near Chico and was the youngest of five children. He deserted from the U.S. Army in 1968 and served time in prison for robbery. He worked as a maintenance man in a trailer park near Tucson, where he lived with his mother.

In July 1992, Kemp and a friend named Jeffrey Logan bought a gun. Logan and Kemp had met in a California prison, from which Logan recently had escaped.

Juarez was a 25-year-old community-college student. On July 11, 1992, he waited for his girlfriend to come home to their apartment from her job at a local shopping mall, and then he took her car at 11:15 p.m. to pick up something to eat. When he didn't return by midnight, the girlfriend went to the apartment-complex parking lot and found the car unlocked. It still smelled like fast food, but Juarez was gone. His body was found July 25, 1992, near the Silver Bell Mine northwest of Tucson. He had two bullets in his head and was wearing nothing but his shoes and socks.

Kemp and Logan were already gone. They'd apparently forced Juarez to withdraw $200 from his bank account, and after they killed him, they tried unsuccessfully to withdraw more. They drove to Flagstaff, where they repainted Kemp's truck and sold it for $650 on July 15.

But they needed another vehicle for their getaway, so they carjacked a couple and forced them to drive to Durango, Colo. There, in a hotel room, Kemp forced the man to disrobe and sexually assaulted him. The couple escaped and contacted police in Kansas. Logan was arrested in Denver and led Tucson police to Juarez's body in the desert. Kemp was arrested in a homeless shelter in Tucson.

While in jail in Pima County, Kemp effectively confessed to killing Juarez when he told two corrections officers that he was afraid of being housed with Mexican prisoners because he had killed a Mexican.

Logan received a sentence of life in prison, which he is serving in Arizona under a different name.

Kemp was convicted of first-degree murder, armed robbery and kidnapping in June 1993. He was sentenced to death a month later. That sentence will be carried out Wednesday.

On July 11, 1992, at approximately 11:15 p.m., Hector Juarez awoke when his fiancée, Jamie, returned home from work to their shared unit at the Promontory Apartments in Tucson. A short time later, Hector left to get something to eat. Jamie assumed he went to a nearby Jack-in-the-Box at the corner of Oracle and River Roads. He never returned. At around midnight, Jamie became concerned that Hector had not come home and began to look for him. She found both her car and his car in the parking lot. Her car, the one Hector was driving, was unlocked, smelled of fast food, and had insurance papers on the roof. After checking with Hector's brother and a friend, Jamie called the police.

Two or three days before Hector was abducted, Jeffery Logan, an escapee from a California honor farm, arrived in Tucson and met with Thomas Arnold Kemp, Jr. On Friday, July 10, Logan went with Kemp to a pawn shop and helped him buy a .380 semi-automatic handgun. Kemp and Logan spent the next night driving around Tucson. At some time between 11:15 p.m. and midnight, Kemp and Logan abducted Hector Juarez from the parking area of his complex. At midnight, Kemp used Hector's ATM card and successfully withdrew approximately $200.

He then drove Hector out to the Siverbell Mine area near Marana. Kemp walked Hector 50 to 70 feet from the truck, forced him to disrobe, and shot him in the head twice. Kemp then made two unsuccessful attempts to use Hector Juarez's ATM card in Tucson. The ATM machine kept the card after the second time. Kemp and Logan painted Kemp's truck, drove to Flagstaff, and sold it. They bought another .380 semi-automatic handgun with the proceeds. While in Flagstaff, Kemp and Logan met a couple travelling from California to Kansas. At some point they kidnapped the couple and forced them to drive to Durango, Colorado, where Kemp forced the man to disrobe. He then sexually assaulted him. The victim testified that while alone with Kemp in a hotel room, Kemp forced him to undress and then touched his genitals. Later, Kemp, Logan, and the couple drove to Denver. Two weeks after Hector Juarez was abducted, the couple escaped. For unknown reasons, Logan left Kemp, contacted the Tucson police about the murder of Hector Juarez, and was arrested in Denver. With Logan's help, the police discovered Hector Juarez's body. Later that day, the police arrested Kemp at a homeless shelter in Tucson. He was carrying the handgun purchased in Flagstaff and a pair of handcuffs.

After having been read his Miranda rights, Kemp answered some questions before he asked for a lawyer. Kemp admitted that he purchased a handgun with Logan on July 10. He said that on the day of the abduction and homicide he was "cruising" though apartment complexes, and that there was a very good possibility he was at the Promontory Apartments. When the police confronted him with the ATM photographs, he initially denied being the man in the picture. After having been told Logan was in custody, and having again been shown the photographs, Kemp said "I guess my life is over now."

While awaiting trial, Kemp on two separate occasions made admissions to corrections officials. Kemp admitted guilt to two jail officials. He made one comment to Officer Compton after having been asked why he was in administrative segregation or protective custody. Kemp said, "the guy I killed was Hispanic" and the Hispanic guys in the pod where he had previously been felt it was racially motivated. Compton testified, "He says white guys can't help me so I have to be put in protective custody status so they couldn't get at him." Officer Jackson testified that Kemp, in the course of a routine conversation, made a similar statement. Kemp said: "the guy I killed was a Mexican, the Mexicans in the pod I was in are after me. That is why I requested to be moved back here, for my own protection."

Logan's and Kemp's trials were severed. Logan was tried first, convicted, and sentenced to life imprisonment for the murder. A jury found Kemp guilty on all counts. The court found three statutory aggravating factors: a prior conviction of a felony involving the use or threat of violence against a person, the murder was committed with the expectation of pecuniary gain, and the murder was committed in an especially heinous, cruel or depraved manner. After the State presented its case to establish three aggravating factors, and the defense presented its case for mitigation, Kemp addressed the court. He said in part: "The prosecutor, in his alleged wisdom, has portrayed me as being a killer without remorse or regret. This is a wholly inaccurate assessment. I feel a deep and abiding sense of remorse at having permitted friendship to stay my hand in the face of wiser counsel; thus electing not to kill Jeff Logan at a time when both instinct and circumstances demanded his death. You can rest assured that is a lapse of judgment I will never repeat and one which I will bend all my energies towards correcting in the not too distant future. Beyond that, I regret nothing ... The so-called victim was not an American citizen and, therefore, was beneath my contempt. Wetbacks are hardly an endangered species in this state. If more of them wound up dead, the rest of them would soon learn to stay in Mexico, where they belong. I don't show any mercy and I am certainly not here to plead for mercy. I spit on the law and all those who serve it ..." The court did not find any mitigating circumstances and sentenced Kemp to death.

Wikipedia: List of People executed in Arizona Since 1976

1. Donald Eugene Harding White 43 M 06-Apr-1992 Lethal gas Allen Gage, Robert Wise, and Martin Concannon

State v. Kemp, 185 Ariz. 52, 912 P.2d 1281 (Ariz. 1996). (Direct Appeal)

Defendant was convicted in the Superior Court, Pima County, Richard Nichols, J., of first-degree felony murder, armed robbery, and kidnapping, and received death sentence for murder. Appeal was automatic. The Supreme Court, Martone, J., held that: (1) defendant's admissions were voluntary; (2) any error from admission of subsequent homosexual assault was harmless; (3) defense opened door for admission of codefendant's statements; (4) evidence supported kidnapping and armed robbery verdicts; (5) jury was fair and impartial; and (6) sentencing was proper. Affirmed.

MARTONE, Justice.

Kemp was found guilty of first degree felony murder, armed robbery, and kidnapping. He received a death sentence for the murder and prison terms for the other offenses. Appeal to this court is automatic under Rules 26.15 and 31.2(b), Ariz.R.Crim.P., and direct under A.R.S. § 13–4031. We affirm his convictions and sentences.

I. FACTS AND PROCEDURE

On July 11, 1992, at approximately 11:15 p.m., Hector Juarez awoke when his fiancee, Jamie, returned home from work to their shared unit at the Promontory Apartments in Tucson. A short time later, Juarez left to get something to eat. Jamie assumed he went to a nearby Jack-in-the-Box at the corner of Oracle and River Roads. He never returned.

At around midnight, Jamie became concerned that Juarez had not come home and began to look for him. She found both her car and his car in the parking lot. Her car, the one Juarez was driving, was unlocked, smelled of fast food, and had insurance papers on the roof. After checking with Juarez's brother and a friend, Jamie called the police.

Two or three days before Juarez was abducted, Jeffery Logan, an escapee from a California honor farm, arrived in Tucson and met with Thomas Kemp. On Friday, July 10, Logan went with Kemp to a pawn shop and helped him buy a .380 semi-automatic handgun. Kemp and Logan spent the next night driving around Tucson. At some time between 11:15 p.m. and midnight, Kemp and Logan abducted Juarez from the parking area of his complex.

At midnight, Kemp used Juarez's ATM card and successfully withdrew approximately $200. He then drove Juarez out to the Siverbell Mine area near Marana. Kemp walked Juarez 50 to 70 feet from the truck, forced him to disrobe, and shot him in the head twice.

Kemp then made two unsuccessful attempts to use Juarez's ATM card in Tucson. The ATM machine kept the card after the second time. Kemp and Logan painted Kemp's truck, drove to Flagstaff, and sold it. They bought another .380 semi-automatic handgun with the proceeds.

While in Flagstaff, Kemp and Logan met a couple travelling from California to Kansas. At some point they kidnapped the couple and forced them to drive to Durango, Colorado, where Kemp forced the man to disrobe. He then sexually assaulted him.

Later, Kemp, Logan, and the couple drove to Denver. Two weeks after Juarez was abducted, the couple escaped. For reasons unclear of record, Logan left Kemp, contacted the Tucson police about the murder of Juarez, and was arrested in Denver.

With Logan's help, the police discovered Juarez's body. Later that day, the police arrested Kemp at a homeless shelter in Tucson. He was carrying the handgun purchased in Flagstaff and a pair of handcuffs. After having been read his Miranda rights, Kemp answered some questions before he asked for a lawyer. Kemp admitted that he purchased a handgun with Logan on July 10. He said that on the day of the abduction and homicide he was “cruising” though apartment complexes, and that there was a very good possibility he was at the Promontory Apartments. When the police confronted him with the ATM photographs, he initially denied being the man in the picture. After having been told Logan was in custody, and having again been shown the photographs, Kemp said “I guess my life is over now.”

While awaiting trial, Kemp on two separate occasions made admissions to corrections officials. He said that he was in protective custody because the person he killed was Hispanic; the Hispanics in the jail were after him because they thought the crime was racially motivated; and the whites would not protect him.

Logan's and Kemp's trials were severed. Logan was tried first, convicted, and sentenced to life imprisonment for the murder. A jury found Kemp guilty on all counts. The court found three statutory aggravating factors: a prior conviction of a felony involving the use or threat of violence against a person, the murder was committed with the expectation of pecuniary gain, and the murder was committed in an especially heinous, cruel or depraved manner. The court did not find any mitigating circumstances and sentenced Kemp to death.

II. ISSUES PRESENTED

Kemp raises the following issues:

A. Trial Issues

1. Did the trial court err in admitting admissions made by Kemp to jail officials?

2. Was evidence of the subsequent homosexual assault erroneously admitted?

3. Were hearsay statements made by Logan erroneously admitted?

4. Did the prosecutor comment on Kemp's invocation of his Miranda rights?

5. Should the trial court have granted Kemp's Rule 20 motion for judgment of acquittal?

6. Did prosecutorial misconduct deprive Kemp of a fair trial?

7. Did the trial court err in not granting Kemp's motion for change of venue?

8. Did the trial court err in impaneling the jury?

B. Sentencing Issues

1. Is the Enmund finding proper?

2. Does Kemp's California robbery conviction qualify as an offense involving the use or threat of violence against a person (A.R.S. § 13–703(F)(2))?

3. Was the killing committed in an especially cruel manner (A.R.S. § 13–703(F)(6))?

4. Is the finding that Kemp murdered the victim in expectation of pecuniary gain proper and is this aggravating factor constitutional (A.R.S. § 13–703(F)(5))?

5. Did the trial court err in failing to find any mitigating factors and was Kemp's mitigation properly balanced against the aggravating factors?

6. Did the trial judge improperly rely on the presentence report in sentencing Kemp to death?

7. Should Kemp's death sentence be vacated as part of this Court's independent review?

8. Should this Court conduct a proportionality review?

9. Did the trial court err in not ordering a competency hearing?

C. Issues waived at trial

Kemp raises the following issues that were not preserved in the trial court. The issues therefore are waived. Furthermore, there was no fundamental error.

1. Did the trial court grant an overbroad limiting instruction guiding the jury's consideration of evidence that Kemp committed a subsequent homosexual assault?

2. Did the trial court err by not, sua sponte, instructing the jury on lesser included offenses to armed robbery and kidnapping? (Because there is no evidence in the record to support giving the instruction, there is no error. Kemp's defense was that Logan was the killer.)

3. Did the trial court err in admitting unduly prejudicial photographs of Juarez's body? (Kemp stipulated to the introduction of the photographs.)

D. Issues waived for failure to argue on appeal

Kemp raises 12 issues in the appendix to his opening brief. Argument, however, must be in the body of the brief. State v. Walden, 183 Ariz. 595, 605, 905 P.2d 974, 984 (1995). We therefore strike the text contained in the appendix of Kemp's opening brief. All of these issues, which we list in our Appendix, are waived. Counsel, to avoid preclusion, must briefly argue the issue in the body of the brief. Id. As we said in Walden, “[a] list of issues in the brief is not adequate. Nor may the argument be in the appendix.” Id.

III. DISCUSSION

Kemp admitted guilt to two jail officials. He made one comment to Officer Compton after having been asked why he was in administrative segregation or protective custody. Compton testified that Kemp said: “the guy killed was Hispanic and the Hispanic guys in the pod where he had previously been felt it was racially motivated. He says white guys can't help me so I have to be put in protective custody status so they couldn't get at him.” Transcript of June 3, 1993, at 18. (At the motion to suppress hearing held out of the presence of the jury, Compton testified that Kemp said “the guy I killed was Hispanic.” Transcript of June 2, 1993, at 159.)

Officer Jackson testified that Kemp, in the course of a routine conversation, made a similar statement. Kemp said: “the guy I killed was a Mexican, the Mexicans in the pod I was in are after me. That is why I requested to be moved back here, for my own protection.” Transcript of June 3, 1993, at 33.

Kemp argues that these statements were involuntarily made in violation of the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution and art. 2, § 10 of the Arizona Constitution. He also argues that they were deliberately elicited by the jail officials in violation of his Fifth Amendment Miranda rights and his Sixth Amendment Massiah rights. Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 86 S.Ct. 1602, 16 L.Ed.2d 694 (1966); Massiah v. United States, 377 U.S. 201, 84 S.Ct. 1199, 12 L.Ed.2d 246 (1964).

The trial judge's finding that the statements were voluntary was not clearly and manifestly wrong. See State v. Scott, 177 Ariz. 131, 136, 865 P.2d 792, 797 (1993). The record supports the finding that the corrections officials were not attempting to overcome Kemp's will to induce him to inculpate himself. While Jackson and Compton testified that inmates generally had to respond to their inquiries, their questions concerned only the “day to day” circumstances of his incarceration. Kemp was not obligated to make these admissions. Cf. Oregon v. Bradshaw, 462 U.S. 1039, 1045, 103 S.Ct. 2830, 2835, 77 L.Ed.2d 405 (1983) (noting that inquiries between the accused and the State “relating to routine incidents of the custodial relationship[ ] will not generally ‘initiate’ a conversation in the sense in which that word was used in Edwards [ v. Arizona, 451 U.S. 477, 101 S.Ct. 1880, 68 L.Ed.2d 378 (1981) (holding that a request for a lawyer requires the police to cease questioning until the accused consults with his or her lawyer unless the defendant initiates further conversation) ].”).

Kemp argues that Miranda requires the exclusion of the statements because he had previously asserted his right to counsel. Edwards v. Arizona, 451 U.S. 477, 101 S Ct. 1880, 68 L.Ed.2d 378 (1981). But Miranda only applies to custodial interrogation. Jackson and Compton did not attempt to elicit an incriminating response from Kemp. See Rhode Island v. Innis, 446 U.S. 291, 100 S.Ct. 1682, 64 L.Ed.2d 297 (1980) (holding that a comment made by one police officer to another, in the presence of the accused, expressing concern that handicapped children might come across a shotgun, is not a statement designed to elicit an incriminating response).

Compton only asked Kemp why he was in protective custody. He did not interrogate him. Routine inquiries by guards concerning the security status of prisoners are not statements designed to elicit an incriminating response. Id. Compton's question was reasonable and relevant to maintaining order in the prison and protecting Kemp. Similarly, Kemp's statements to Jackson were the product of ordinary, everyday interaction between guard and prisoner. Because Kemp was not interrogated by Compton and Jackson, the admission of his statements did not violate Miranda and his rights under art. 2, § 24 of the Arizona Constitution.

Kemp's assertion that his Sixth Amendment Massiah rights were violated fails for the same reason his Miranda claim fails: the guards did not seek to elicit incriminating evidence from him. Kuhlmann v. Wilson, 477 U.S. 436, 459, 106 S.Ct. 2616, 2630, 91 L.Ed.2d 364 (1986) (holding that “the defendant must demonstrate that the police and their informant took some action, beyond merely listening, that was designed deliberately to elicit incriminating remarks”). Kemp's admissions therefore were properly admitted.

2. Subsequent Homosexual Assault

Kemp claims that the admission of evidence that he sexually assaulted the man he abducted after selling his truck in Flagstaff unfairly prejudiced his defense and requires reversal. The victim testified that while alone with Kemp in a hotel room, Kemp forced him to undress and then touched his genitals. At trial, the State sought to introduce evidence of the kidnapping, robberies, and sexual assault committed by Kemp and Logan after the murder of Juarez and during the flight from Tucson. The trial court granted Kemp's motion in limine to exclude all of the criminal acts except the sexual assault.

We agree that the trial court erred. All of the kidnapping and robbery evidence should have been admitted as evidence of flight showing consciousness of guilt. See M. Udall & J. Livermore, Law of Evidence § 125, at 258 (3d ed. 1991). The sexual assault is more problematic. At trial, the State offered the sexual assault evidence to establish motive for the abduction of Juarez and to prove the identity of the person who killed him. On appeal, the State abandoned this rationale and argued that the evidence would have been properly admitted to show a common plan or scheme. Rule 404(b), Ariz.R.Evid.

We need not consider the new theory, because even if there was error, it was harmless beyond a reasonable doubt. Kemp's conviction is supported by overwhelming evidence of his guilt, including his own statements to the police and corrections officials. After viewing the record in its entirety, we find beyond a reasonable doubt that the jury would have reached the same verdict if the evidence had been excluded.

Kemp also argues that the prosecutor did not timely disclose that the subsequent homosexual assault would be used against him. Before trial, the court on two occasions ordered the State to disclose the bad acts it would use. See Rule 15.1(a)(6), Ariz.R.Crim.P. The State did disclose the victim of the subsequent homosexual assault as a possible witness approximately six months before trial. While it never provided Kemp with a list of his bad acts, Rule 15.1(a)(6) appears to apply to prior acts and not subsequent conduct. But even if Rule 15.1(a)(6) applies here, there simply was no prejudice.

Discovery rulings are affirmed unless there is an abuse of discretion. See State v. Krone, 182 Ariz. 319, 321, 897 P.2d 621, 624 (1995). Kemp argues that he was unable to obtain a fair and impartial jury and he was unable to develop any impeachment or motive evidence against the victim of the subsequent homosexual assault. We disagree.

First, the record is clear that Kemp's trial counsel was aware that Kemp's homosexuality potentially would be placed before the jury. Logan's statements to the police and media raised the issue. In addition, Logan's trial preceded Kemp's, and the witness Kemp sought to preclude testified regarding the same events at Logan's trial. Furthermore, Kemp successfully suppressed other evidence of his homosexuality, including sexually explicit photographs and a journal purportedly detailing his homosexual encounters. Although Kemp did not have a ruling regarding the bad act evidence prior to voir dire, he was clearly aware of the issue, was not surprised, and could have developed it at voir dire if he so wanted.

Second, Kemp's argument that he was unable to develop impeachment or motive evidence is without merit. The only connection the witness had to Kemp was the misfortune of being his kidnapping, robbery, and sexual assault victim. The witness was listed approximately six months before Kemp's trial and testified about the same events at Logan's trial. There was no abuse of discretion.

3. Logan's Hearsay Statements

Kemp claims the court erred in admitting evidence that Logan made statements to the police about the murder. Before trial, and after Kemp's and Logan's trial was severed, Kemp filed a motion to preclude Logan's hearsay statements. Apparently, the motion was not ruled upon. At trial, after the judge ruled that defense counsel had opened the door to their admission, the police detective who had interrogated both Logan and Kemp was permitted to testify to some of the statements made by Logan.

On direct examination during the State's case-in-chief, the police detective testified that he questioned Kemp after his arrest and that Kemp agreed to answer some of his questions. Through the police detective, some of Kemp's admissions concerning his activities and association with Logan before the murder were admitted.

On cross-examination, defense counsel elicited answers that all of the physical evidence, with the exception of the “fuzzy” ATM photograph, implicated Logan but not Kemp. He then went on to ask:

Q: There is no evidence that Kemp had possession of the gun that killed Hector [Juarez] at any time after the purchase?

A: No.

Q: And in fact, the only evidence you have got of what happened to that gun is it was used to kill Hector and Jeff Logan had it; no evidence Thomas Kemp was in the Siverbell Mines area that night, is there?

A: No.

Q: There is no evidence that Thomas Kemp knew?

A: No.

Q: There is no evidence that Thomas Kemp was at the scene where the body was found at all?

A: No.

Transcript of June 3, 1993, at 69 (emphasis added).

The State on re-direct was permitted to question the police detective about his interrogation of Logan to rebut the inference that no evidence connected Kemp to Juarez's murder in Marana. The police detective testified to the following: he had a tape recorded conversation with Logan; Logan said he had been in Tucson two or three days before Juarez's disappearance; Logan told him what happened to Juarez; and Logan told him what he and Kemp were doing the night Juarez disappeared. The trial judge determined that this limited line of inquiry was sufficient to meet the improper inference created by Kemp's defense counsel. The trial judge did not permit the State to elicit Logan's statements that Kemp shot Juarez and to explain how it was that Logan knew where the body was located.

Defense counsel objected to the evidence based on hearsay. The trial judge ruled that the questions asserting that “no evidence” connected Kemp to the murder scene created a false inference and opened the door enough to allow the State to rebut this inference.

On appeal, the State argues that some of this evidence is not hearsay because the statements were not offered for proof of their truth, but just for the fact that they were made. Rule 801(c), Ariz.R.Evid. See John W. Strong, 2 McCormick on Evidence § 250, at 111 (4th ed. 1992). However, the statements were also offered by the State to show that Kemp participated in the murder. Because this is a mixed question, we analyze these statements as if they were hearsay.

Kemp's questioning on cross-examination created the inference that no evidence connected him to Juarez's killing. In fact, there was evidence, Logan's statements, connecting Kemp to the murder scene. Kemp, of course, is entitled to comment on the strength of the State's case against him. If Kemp's defense counsel had asserted that all of the physical evidence inculpated Logan but not Kemp, or otherwise limited his inquiry, no improper inference would have been raised. Kemp's counsel went beyond this. He left the jury with the impression that no evidence connected Kemp to the murder.

Kemp invited error with his cross-examination. As we stated in State v. Lindsey, “[i]n essence the ‘open door’ or ‘invited error’ doctrine means ‘that a party cannot complain about a result he caused.’ ” 149 Ariz. 472, 477, 720 P.2d 73, 78 (1986) (quoting M. Udall & J. Livermore, Law of Evidence § 11, at 11 (3d ed. 1991)). By asserting the non-existence of evidence connecting Kemp to the murder, defense counsel cannot now claim error occurred by meeting the assertion with contrary proof.

We reached the same conclusion in State v. Martinez, 127 Ariz. 444, 622 P.2d 3 (1980). Martinez was being tried for armed robbery. He was arrested after a subsequent robbery attempt went awry; his accomplice escaped and was not arrested. Before trial the court granted Martinez's motion to preclude evidence of the subsequent attempted robbery because its prejudice substantially outweighed its probative value.

When Martinez took the stand in his own defense, he testified that he knew his accomplice only “vaguely” and had met him “once when—last November, I think just briefly.” Id. at 446, 622 P.2d at 5. He also testified that he had seen the rifle used in the robbery in someone else's possession, but was vague about the circumstances. Id. The trial court allowed the State to elicit testimony regarding the subsequent robbery attempt, including testimony that Martinez struggled for control of the rifle. Id. at 447, 622 P.2d at 6. We rejected Martinez's challenge to the admission of this testimony and stated that “[w]hen the defendant, as here, ‘opens the door’ by denying certain facts which the evidence, previously excluded, would contradict, he may not rely on the previous ruling that such evidence will remain excluded.” Id.

In all events, Kemp suffered no prejudice from the admission of Logan's statements. The only new information the jury learned, that it did not already know from other sources, was that Logan made a statement about what happened the night Juarez was abducted, robbed, and killed. The other evidence was cumulative to Kemp's admissions. Specifically, through Kemp's statement after his arrest, the jury had already been informed of Kemp's concern about Logan, the fact that Logan and Kemp had spent a few days together before the homicide, and that they were together the night of the homicide. Any error would have been harmless in light of the substantial evidence of Kemp's guilt.

4. The Doyle Arguments

Doyle v. Ohio, 426 U.S. 610, 96 S.Ct. 2240, 49 L.Ed.2d 91 (1976), prohibits the state's use of the accused's invocation of his Fifth Amendment rights. The State asked a police detective about a statement Kemp made after his arrest. On cross-examination, Kemp's counsel asked the police detective about other aspects of Kemp's statement. During the redirect examination of the police detective, the prosecutor asked Detective Salgado:

Q: At some point, sir, in that same conversation with Mr. Kemp, did you actually come out and ask him questions about the apartment complex parking lot and how Hector Juarez may have gotten in the vehicle with Mr. Kemp.

A: Yes, I did.

Q: At that point, sir, did Mr. Kemp express reluctance to answer your question about the parking lot?

Transcript of June 3, 1993, at 87.

Kemp's objection to the question was sustained before the detective could answer. Although a transcript of Kemp's statement is not part of the record, it appears the answer to the question about the parking lot would have been that Kemp said he was getting nervous. Id. at 98. Apparently, the question to which Kemp asserted his Miranda rights was a later question asking whether Juarez got into his truck. Id. Kemp points to no part of the record to show otherwise. There was no error.

But even assuming it was an improper question, Kemp suffered no prejudice because his objection was immediately sustained before the witness answered the question. In similar cases, we have held that a sustained objection protects a party from improper questions. State v. Sullivan, 130 Ariz. 213, 217–18, 635 P.2d 501, 505–06 (1981) (holding that prejudice from a question that violated Doyle was cured by immediately sustaining objection before the question was answered); State v. Clark, 110 Ariz. 242, 244, 517 P.2d 1238, 1240 (1974) (holding that prejudice from question concerning the treatment of defendants found not guilty by reason of insanity to be cured by immediately sustaining objection and by a curative instruction to the jury). Likewise, Kemp's motion for a mistrial was properly denied.

Kemp also argues that the prosecutor commented on Kemp's silence during closing argument. At closing argument, the prosecutor said: “In this particular case, Mr. Kemp and Mr. Logan obviously were out together as Mr. Kemp told Detective Salgado when he talked to him. He was evasive in some of the areas he was giving answers to.”

Defense counsel did not object, and thus the point is waived. But even had the point been preserved, there was no error. The prosecutor said that Kemp answered questions evasively. This argument is supported by the statements Kemp made to the police after his arrest and before he asked for a lawyer. Kemp said that he was “cruising” apartment complexes. He said there was “a very good possibility” that he was at the apartment from which Juarez was abducted. He said he was going “in and out” of various apartment complexes. Transcript of June 3, 1993, at 57, 60–61. These answers are evasive. Lawyers are entitled to make arguments based on the evidence and reasonable inferences that can be drawn from the evidence. E.g., State v. Woods, 141 Ariz. 446, 454, 687 P.2d 1201, 1209 (1984). The prosecutor's closing argument is supported by the evidence.

5. The Kidnapping and Armed Robbery Convictions

Kemp argues that the evidence is insufficient to find that the victim was kidnapped and robbed, and that his motion for a directed verdict should have been granted. Kemp abducted the victim from the parking area of his apartment complex. A short time later, Kemp used the victim's ATM card at a location between the place of abduction and the site of the murder. The only reasonable inference to be drawn from the evidence is that Kemp and Logan abducted the victim using the gun purchased the day before, forced him to reveal his ATM personal identification number, and then took his money. The evidence viewed in the light most favorable to sustaining the verdict supports the kidnapping and armed robbery convictions.

6. Prosecutorial Misconduct

Kemp claims ten instances of prosecutorial misconduct. All but one of these instances are waived because Kemp failed to object at trial. And none of the nine waived instances can be deemed fundamental error. The nine alleged instances of prosecutorial misconduct are either immaterial and non-prejudicial statements, or have been taken out of context by Kemp on appeal.

The preserved instance of alleged prosecutorial misconduct is the following statement by the prosecutor made during closing argument: “[Defense counsel] has gone so far as to suggest we don't even know if it happened in Pima County. You can be sure of one thing. You wouldn't hear the case, number one, and so that particular argument is simply without merit.” Transcript of June 4, 1993, at 59. The trial judge overruled Kemp's objection to this statement. The State on appeal concedes that this statement is “arguably improper” but asserts that it is nonetheless harmless. We agree. Defense counsel during closing argument asserted that the State had to prove that Juarez was killed in Pima County. However, the State only had to prove that an element of the offense, such as the kidnapping or the armed robbery, occurred in Pima County. A.R.S. § 13–109. The State proved this, so error, if any, would be harmless.

7. Change of Venue

Kemp argues that the trial judge should have granted a motion for change of venue because of pretrial publicity. Kemp has not met his burden of showing that the limited pretrial publicity the case received requires this court to presume prejudice. While it is true that Logan made a number of accusations before trial that were reported in the press, those same press articles contained statements by prosecutors and Kemp's defense counsel attacking Logan's veracity and character. The exposure of Kemp's jurors to pretrial publicity was minor and inconsequential.

In addition, the record indicates that Kemp was able to discover whether any juror was actually prejudiced by the pretrial publicity. No juror was so prejudiced, and Kemp does not claim otherwise. The motion was properly denied.

8. Other Jury Issues

Kemp raises six additional jury selection arguments. First, he argues that the court erred in not providing him a jury roster in advance. Second, he claims the trial court erred in denying his motion to submit a questionnaire to the jury. Third, he claims the trial court should have allowed the lawyers to conduct individual voir dire. Fourth, he claims the death qualification procedure deprived him of a fair trial. Fifth, he claims that the trial court erred in refusing to strike one venire person for cause. Sixth, and finally, he claims that the trial court erred in striking another venire person for cause. All of these claims are without merit.

After reviewing the record, we are convinced that Kemp was tried by a fair and impartial jury. Kemp's jury selection arguments, presented in three and a half pages in his 89 page opening brief, are unclear, lack adequate legal argument and citation to the record. The crux of Kemp's jury arguments seems to be that he was denied an opportunity to question the jury regarding their attitudes and beliefs on homosexuality. But he had the opportunity and elected not to take it. See ante, at 1288. Kemp's first four jury claims are inadequately argued and appear to be without merit. We summarily reject them. See Rule 18.3, Ariz.R.Crim.P. (jury roster to be supplied on day jury selection is commenced); Rule 18.5(d), Ariz.R.Crim.P. (trial court shall conduct voir dire and in its discretion allow counsel to question jurors); State v. Walden, 183 Ariz. 595, 905 P.2d 974 (1995) (decision to submit a jury questionnaire in the sound discretion of the trial court; death qualification of jury permitted).

Kemp also claims that the trial court erred in not striking a particular juror for cause. The juror indicated that his father-in-law had been convicted of incest twenty years ago. He indicated this would not affect his ability to be impartial. The trial court did not abuse its discretion in failing to strike that juror for cause. Id. at 608–09, 905 P.2d at 987–98.

Finally, Kemp claims the trial judge abused his discretion in striking another juror for cause. The juror indicated that he could not participate. He said: “I can't make a decision in this case. I don't have a good excuse. It's too complicated.” Transcript of June 2, 1993, at 95. The juror's response indicated he could not be fair or impartial. There was no abuse of discretion. Id.

B. Sentencing Issues

Kemp challenges the trial court's finding, pursuant to Enmund v. Florida, 458 U.S. 782, 102 S.Ct. 3368, 73 L.Ed.2d 1140 (1982), that he actually killed and intended to kill the victim. We reject this claim. First, Kemp's statements to the corrections officials support the finding. Second, two ATM photographs taken shortly after the victim disappeared show someone resembling Kemp using the victim's ATM card. Third, when police confronted Kemp with the photographs, and insisted he was the one using the card, he replied, “Well, I know you guys aren't stupid.” Fourth, Kemp purchased the murder weapon the day before the murder.

2. Prior Violent Conviction

Kemp first argues that the State did not prove Kemp's prior California robbery conviction beyond a reasonable doubt. However, this argument is without merit because he stipulated to his previous conviction.

Kemp also argues that his California robbery conviction is not a prior crime of violence against a person under A.R.S. § 13–703(F)(2). We disagree. Both the State and Kemp agree that the California statute under which Kemp was convicted requires the taking of property from a person accompanied by “force or fear” and defines fear as either: “1) The fear of an unlawful injury to the person or property of the person robbed.... or 2) The fear of an immediate and unlawful injury to the person or property of another in the company of the person robbed at the time of the robbery.” Cal.Penal Code §§ 211 (1951) (defining robbery) & 212 (1963) (defining force or fear) (emphasis added). Kemp argues that the California statute does not satisfy the (F)(2) factor because its statutory definition does not require the use or threat of violence against a person. Robbery could be committed by threatening force against property.

A prior conviction satisfies A.R.S. § 13–703(F)(2) only if it involves the use or threat of violence against a person, State v. Arnett, 119 Ariz. 38, 579 P.2d 542 (1978), according to its statutory definition, State v. Gillies, 135 Ariz. 500, 662 P.2d 1007 (1983). Extrinsic evidence explaining the prior conviction is not admissible to prove that a prior conviction involved violence against a person. State v. Romanosky, 162 Ariz. 217, 227, 782 P.2d 693, 703 (1989).

We addressed the California robbery statute in State v. Correll, 148 Ariz. 468, 478–79, 715 P.2d 721, 731–32 (1986), and concluded that a robbery conviction under it satisfied (F)(2), at least where it involved the use of a firearm. Yet it was not an armed robbery conviction. The Court treated the robbery conviction as though it were armed robbery because of the sentence enhancement caused by the use of a firearm.

The meaning of Correll is unclear, if the court actually determined that it was “ theoretically possible” to commit a robbery, with or without a weapon, under the California statute in which property, and not a person, was subjected to the threat or use of violence. Id. at 479, 715 P.2d at 732. But we do not read Correll to say that it is even theoretically possible to commit armed robbery without threatening violence against a person. The Court continued: “As a practical matter ‘armed’ robbery against the property of a victim does not occur without use or threat of violence against the person as well.” Id. at 479, 715 P.2d at 732. Thus, the fact that a firearm was used necessarily involved the threat of violence.

Even though it was the use of a firearm that was dispositive in Correll, we agree with the State that it is also possible to envision a “non-violent” robbery accomplished without a firearm. First, even though it is possible to commit robbery in California by threatening force against property, the person from whom property is being taken actually experiences the fear. Under State v. Arnett, 119 Ariz. 38, 51, 579 P.2d 542, 555 (1978), this fear is the violence. Id. (defining violence as the “exertion of any physical force so as to injure or abuse.”). Second, the California robbery statute requires the “taking of personal property in the possession of another, from his person or immediate presence, and against his will” by means of force or fear. Cal.Penal Code § 211 (1951) (emphasis added). Implicit in the California robbery statute is the danger that either the taking itself or the foreseeable resistance to the taking presents the risk of violence. This threat of violence is what makes robbery a more serious crime than larceny. And this threat of violence is the same whether the robbery is accomplished by threatening force against a person or against property. Robbery is clearly a crime against a person. It necessarily carries with it the threat or use of violence. Accordingly, Kemp's robbery conviction satisfies A.R.S. § 13–703(F)(2).

3. Cruelty

Relying on State v. Poland, 132 Ariz. 269, 645 P.2d 784 (1982), appeal after remand, 144 Ariz. 388, 698 P.2d 183 (Patrick) and 144 Ariz. 412, 698 P.2d 207 (Michael) (1985), Kemp argues that the trial court erred in finding that the murder was committed in an especially cruel manner. A.R.S. § 13–703(F)(6). Evidence about “[a] victim's certainty or uncertainty as to his or her ultimate fate can be indicative of cruelty and heinousness.” State v. Gillies, 142 Ariz. 564, 569, 691 P.2d 655, 660 (1984).

The evidence supports the finding. Juarez was abducted from the parking area of his apartment complex. His body was discovered approximately 100 feet off a dirt road in the desert north of Tucson. At some point, after his abduction, Juarez provided Kemp with his personal identification number. Two spent bullet casings were found in the area around his body. He died of two gunshot wounds to the back of the head. Kemp on two occasions admitted the killing.

The only reasonable inference from these facts is that Juarez suffered incredible terror from the moment of his abduction until his murder. Once Logan and Kemp had taken him about fifteen miles north of Tucson, Juarez must have experienced great and terrible uncertainty about his fate. The evidence indicates that Kemp must have led Juarez at gunpoint from the truck to the place where the killing occurred. Once he was forced away from the truck and forced to disrobe, he must have known that his murder was imminent. We think this case is more like State v. Bible, 175 Ariz. 549, 858 P.2d 1152 (1993), than Poland, supra. The cruelty finding is proper.

4. Pecuniary Gain

The trial judge found as an aggravating factor that the murder was committed for pecuniary gain. A.R.S. § 13–703(F)(5). Kemp argues that this factor is unconstitutional as applied here because it repeats an element of the underlying crime of felony murder. Kemp also argues the finding is not supported by the evidence. We disagree with both contentions.

Kemp first challenges the constitutionality of the (F)(5) factor, asserting that any homicide occurring in the course of an armed robbery will also support a finding that the murder was committed for pecuniary gain. We have previously rejected this argument. State v. Greenway, 170 Ariz. 155, 163–65, 823 P.2d 22, 30–32 (1991). In any event, Juarez's killing in the course of the kidnapping is first degree felony murder, wholly apart from the armed robbery conviction. A.R.S. § 13–1105. Thus, Kemp's argument is irrelevant to the constitutionality of the pecuniary gain finding in this case.

Second, the evidence supports the finding in this case. Kemp purchased the murder weapon the day before the murder. Juarez's ATM card was used almost immediately after his abduction and before his murder. Kemp committed the armed robbery, kidnapping, and murder with the expectation of receiving something of pecuniary value. See State v. Spencer, 176 Ariz. 36, 859 P.2d 146 (1993). The finding is proper.

5. Mitigating Factors

Kemp did not seek to prove the existence of any statutory mitigating factors at sentencing. Kemp attempted to prove the existence of non-statutory mitigation but did not offer any evidence or present witnesses.

Through a sentencing memorandum, Kemp sought to prove the following non-statutory mitigating factors: Kemp suffers from a personality disorder making him perceive others as “selfish, dishonest, and opportunistic” whose “only recourse is to get what [he] can for [himself],” Record on Appeal at 324; Kemp failed to receive requested psychological counselling during previous periods of incarceration in California and Arizona, id. at 325; his good behavior, or more specifically, his lack of a disciplinary record, during his previous prison terms, id. at 325–26; his good family background and his mother's dependency upon him, id. at 326; the fact that he is a follower, based on the evidence presented at trial, id. at 327–28; and the fact that the conviction was based on circumstantial evidence, id. at 328–29. Kemp did not offer evidence of a neuropsychological examination that he admits found no evidence of brain impairment.

After the State presented its case to establish three aggravating factors, and the defense presented its case for mitigation, Kemp addressed the court. He said in part:

The prosecutor, in his alleged wisdom, has portrayed me as being a killer without remorse or regret. This is a wholly inaccurate assessment. I feel a deep and abiding sense of remorse at having permitted friendship to stay my hand in the face of wiser counsel; thus electing not to kill Jeff Logan at a time when both instinct and circumstances demanded his death.

You can rest assured that is a lapse of judgment I will never repeat and one which I will bend all my energies towards correcting in the not too distant future. Beyond that, I regret nothing ...

The so-called victim was not an American citizen and, therefore, was beneath my contempt. Wetbacks are hardly an endangered species in this state. If more of them wound up dead, the rest of them would soon learn to stay in Mexico, where they belong.

I don't show any mercy and I am certainly not here to plead for mercy. I spit on the law and all those who serve it ...

Transcript of July 9, 1993, at 17–18.

The court found that Kemp did not prove the existence of any mitigation. We agree.

The court went on to state that even if the defendant had proved the existence of mitigation, any one of the aggravating factors it found were independently sufficient to call for the death penalty. Kemp argues that this finding makes clear that the trial judge did not consider his mitigation. We disagree. This finding indicates that the trial judge did consider the evidence Kemp offered for mitigation; he found that anything Kemp offered, even if proved, would not have been sufficiently substantial to call for leniency.

Kemp complains that the trial judge relied upon a sentencing order prepared in advance and delivered at the conclusion of the hearing. We find no merit to his argument that this indicates a failure to consider Kemp's proffered mitigation. Kemp also argues that the weighing process was faulty, apparently because he disagrees with the weight given to each mitigating factor. Our review of the record indicates that the trial judge properly determined that there was no mitigation, or alternatively, no mitigation sufficiently substantial to call for leniency.

6. Reliance upon the presentence report

Kemp argues that the trial judge relied upon the presentence report which apparently contained inadmissible evidence. However, our review of the special verdict indicates that the trial judge only specifically relied upon the presentence report, which is not part of the record, in two instances. First, he relied on it in part to find that Kemp had previously been convicted of a crime of violence. But Kemp stipulated to the fact of his prior California robbery conviction. Second, the trial judge indicated he relied upon it as a possible source of mitigation. While evidence in support of aggravation must be admissible under the rules of evidence, evidence in support of mitigation does not. A.R.S. § 13–703(C). Kemp does not allege that he suffered prejudice from this reliance. The findings of the trial judge in the special verdict are all supported by the evidence.

7. Independent Review

This Court independently reviews the record in all capital cases and determines whether the death sentence is appropriate. State v. Hill, 174 Ariz. 313, 326, 848 P.2d 1375, 1388 (1993). On this appeal we affirm Kemp's three aggravating factors. After balancing the aggravating factors against evidence offered by the defendant, which we find does not rise to level of mitigation, we affirm Kemp's death sentence. Under A.R.S. § 13–703(E), once we have determined the presence of one aggravating factor, and no mitigation, we must affirm the death sentence. See Walton v. Arizona, 497 U.S. 639, 649–51, 110 S.Ct. 3047, 3055–56, 111 L.Ed.2d 511 (1990).

Even if Kemp's proffered mitigation rose to the level of mitigation, we agree with the trial court that none of this evidence is sufficiently substantial to call for leniency.

8. Proportionality Review

Kemp argues he is entitled to have his sentence reduced to life under a proportionality review. This court no longer conducts proportionality reviews of death sentences. State v. Salazar, 173 Ariz. 399, 844 P.2d 566 (1992).

9. Kemp's Competency

Kemp addressed the court at sentencing. Ante, at 1295. Kemp now argues that the trial judge erred in not ordering, sua sponte, a competency hearing under Rule 11.1, Ariz.R.Crim.P. There was no abuse of discretion here. Kemp's statement does not cast doubt on his ability to understand the nature of the proceedings. See Rule 11.3, Ariz.R.Crim.P. It does not indicate that he lacked the ability to assist in his defense. If anything, his statement says much about the absence of mitigation here and the propriety of the sentence. Because there were no grounds to conduct a competency hearing, the trial judge did not err in failing to order one sua sponte.

IV. DISPOSITION

We reviewed the record for fundamental error and found none before we decided State v. Smith, 184 Ariz. 456, 910 P.2d 1 (1996) (holding that the repeal of A.R.S. § 13–4035 is procedural and not substantive and therefore fully retroactive).FN1 For the foregoing reasons, we affirm Kemp's convictions and sentences.

FN1. The relationship, if any, between our independent review of the propriety of a death sentence and the discontinuance of fundamental error review will have to await another day—in a case in which it is raised and briefed.

FELDMAN, C.J., ZLAKET, V.C.J., and MOELLER and CORCORAN, JJ., concur.

APPENDIX

Issues waived for failure to argue on appeal.

a. Arizona's death penalty statute violates equal protection by providing non-capital defendants with a jury determination of sentence-enhancing allegations and not providing capital defendants with jury determination of aggravating factors.

b. Arizona's death penalty statute fails to sufficiently channel the sentencer's discretion.

c. Arizona's death penalty statute contains no guidelines for prosecutors.

d. The death penalty in Arizona violates the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution and art. 2, §§ 1, 4, and 15 of the Arizona Constitution.

e. The death penalty in Arizona has discriminatorily been applied in Arizona against poor, young males whose victims are caucasian in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment and Ariz. Const. art. 2, §§ 13 and 15. (In this case, however, the victim is a young Mexican male and the defendant is a middle-aged caucasian.)

f. The trial court did not find that death is “appropriate.”

g. Arizona's death penalty statute prevents the consideration of all mitigating factors not meeting the evidentiary standard.

h. Placing the burden of proof on the defendant to show that life is the appropriate sentence is unconstitutional.

i. Judge sentencing violates Kemp's right to have a jury consider all the elements of the offense.

j. A.R.S. § 13–703(F)(6) factor defining cruelty, heinous, and depravity is unconstitutionally vague.

k. The felony murder statute violates the Eighth Amendment by creating a strict liability offense.

l. The trial court erred by failing to instruct the jury that the proper mens rea for felony murder requires a reckless indifference to human life.

Kemp v. Ryan, 638 F.3d 1245 (9th Cir. 2011). (Habeas)

Background: State prisoner petitioned for writ of habeas corpus after his conviction for felony first-degree murder, armed robbery, and kidnapping, and from his capital sentence, had been affirmed on appeal, 185 Ariz. 52, 912 P.2d 1281. The United States District Court for the District of Arizona, Frank R. Zapata, Senior District Judge, 2008 WL 4183379, denied petition, but granted certificate of appealability, 2008 WL 4418164. Prisoner appealed.

Holdings: The Court of Appeals, Callahan, Circuit Judge, held that:

(1) Arizona Supreme Court could rely on position that had been adopted only by plurality of United States Supreme Court;

(2) district court reasonably denied prisoner's request for discovery, and request for evidentiary hearing;

(3) due process did not require re-voir dire of jury after trial court had denied motions in limine that would have barred introduction of subsequent homosexual assault. Affirmed.

CALLAHAN, Circuit Judge:

Thomas Arnold Kemp raises three issues in his appeal from the district court's denial of his habeas petition seeking relief from his state conviction for felony first-degree murder, armed robbery and kidnaping and from his capital sentence. First, Kemp asserts that his rights to be free from compelled self-incrimination and to counsel under the Fifth, Sixth, and Fourteenth Amendments were violated when correctional officers asked him questions and his incriminating statements were admitted at trial. Kemp also argues that the district court abused its discretion in denying him discovery to prove this claim. Second, Kemp contends that without his incriminating statements, which should have been suppressed, the prosecution failed to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that he possessed the requisite mental state for the imposition of the death penalty. Third, Kemp claims that he was denied due process under the Fourteenth Amendment when the prosecutor was dilatory in giving notice that he would introduce evidence that Kemp committed a homosexual sexual assault, the trial court failed to rule the subsequent bad act admissible until after the jury had been voir dired, and the trial court then denied Kemp's request to voir dire the jury on homosexual bias. We affirm. Kemp has not shown that the Arizona Supreme Court's opinion affirming his conviction and capital sentence was either “an unreasonable application of, clearly established Federal law,” or “an unreasonable determination of the facts,” as required for relief under the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (“AEDPA”), 28 U.S.C. § 2254.

I

The underlying criminal acts were described as follows by the district court:

On July 11, 1992, at approximately 11:15 p.m., Hector Juarez awoke when his fiancee, Jamie, returned from work to their residence at the Promontory Apartments in Tucson. A short time later, Juarez left to get something to eat. Jamie assumed he went to a nearby fast food restaurant.

At around midnight, Jamie became concerned that Juarez had not come home and began to look for him. She found both her car and his car in the parking lot. Her car, which Juarez had been driving, was unlocked and smelled of fast food; the insurance papers had been placed on the vehicle's roof. After checking with Juarez's brother and a friend, Jamie called the police.

Two or three days before Juarez was abducted, Jeffery Logan, an escapee from a California honor farm, arrived in Tucson and met with Petitioner. On Friday, July 10, Logan went with Petitioner to a pawn shop and helped him buy a .380 semi-automatic handgun. Petitioner and Logan spent the next night driving around Tucson. At some time between 11:15 p.m. and midnight, Petitioner and Logan abducted Juarez from the parking area of his apartment complex.

At midnight, Petitioner used Juarez's ATM card and withdrew approximately $200. He then drove Juarez out to the Silverbell Mine area near Marana. Petitioner walked Juarez fifty to seventy feet from the truck, forced him to disrobe, and shot him in the head twice.

Petitioner then made two unsuccessful attempts to use Juarez's ATM card in Tucson. The machine kept the card after the second attempt. Petitioner and Logan repainted Petitioner's truck, drove to Flagstaff, and sold it. They bought another .380 semi-automatic handgun with the proceeds.

While in Flagstaff, Petitioner and Logan met a man and woman who were traveling from California to Kansas. They abducted the couple and made them drive to Durango, Colorado; in a motel room there, Petitioner forced the man to disrobe and sexually assaulted him.

Later, Petitioner, Logan, and the couple drove to Denver, where the couple escaped. Logan and Petitioner separated. Logan subsequently contacted the Tucson police about the murder of Juarez. He was arrested in Denver.

With Logan's help, the police located Juarez's body. Later that day, the police arrested Petitioner at a homeless shelter in Tucson. He was carrying the handgun purchased in Flagstaff and a pair of handcuffs. After having been read his Miranda rights, Petitioner answered some questions before asking for a lawyer. He admitted that he purchased a handgun with Logan on July 10. He said that on the day of the abduction and homicide he was “cruising” through apartment complexes, possibly including the Promontory Apartments. When confronted with the ATM photographs, he initially denied being the individual in the picture. After having been told that Logan was in custody and again having been shown the photographs, Petitioner said, “I guess my life is over now.”

B. Kemp's Incriminating Statements While in Jail.

After he was arrested, Kemp was advised of his rights under Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 86 S.Ct. 1602, 16 L.Ed.2d 694 (1966). Later in the evening, Kemp was interviewed by Detective Salgado, but when he was asked about his contact with Juarez, Kemp invoked his right to counsel.

Kemp was taken to the Pima County Jail. During his stay in the jail, Kemp made two incriminating statements. The district court described the events surrounding the statements as follows:

John Jackson, an officer at the Pima County Jail, walked by Petitioner's cell in the disciplinary pod and they had a three to five minute conversation. Jackson did not recall who initiated the interaction. During the conversation, Petitioner volunteered that he had requested to be moved to the disciplinary pod “because the guy I killed was a Mexican. That the Mexicans in the pod were after him, and he wanted to be moved from there for his own protection.” At the time, Jackson did not write a report on the conversation.

Kippy Compton, a Pima County Sheriff's Department correctional officer, recognized Petitioner from a general population pod at the jail. On December 14, 1992, he transported Petitioner within the jail and saw on his identification card that he was in AS1, which is a protective custody status. Compton testified that he must have been off the day they were briefed about Petitioner's status change; the officers are briefed because they need to be aware of any other inmate(s) the person may need to be kept away from. Compton asked Petitioner why he was in AS1 and testified that Petitioner gave the following response: “that Hispanic guy I killed or the guy I killed was Hispanic and the Hispanic guys in the pod think it's racially motivated, and he—he said the whites said they can't help me or won't help me, and so I asked to be put on protective custody.” Compton testified that he was not trying to ask Petitioner about his case because the inmates are not going to talk about their cases and he didn't care. Compton did not question Petitioner further, did not threaten him, or make any promises to him. Compton testified that inmates are expected to respond when questioned by a correctional officer. After thinking about it, Compton decided to write the conversation up in a memo.

While Jackson was carpooling home with Compton one evening, Compton mentioned his conversation with Petitioner and then Jackson mentioned that he had a similar statement from Petitioner. After that conversation, Jackson prepared a report about his conversation with Petitioner.

Kemp filed a pretrial motion to suppress the two statements he had made to Jackson and Compton. The trial court held a hearing on the motion at which both officers testified. The state court found that Kemp's statements to the officers were voluntary and admissible because the conversations were informal and they were not intended or designed to elicit incriminating responses. The officers testified at trial consistent with their testimony at the suppression hearing.

C. The Alleged Curtailment of Voir Dire.

In September 1992, Kemp, through his attorney, first sought discovery with respect to possible prior and subsequent bad acts that the prosecutor might seek to present at trial. At a December 1992 pretrial hearing, the prosecutor agreed to give Kemp a list of prospective witnesses and noted that in the afternoon he would be interviewing the “couple that were kidnaped out of Flagstaff.” On January 25, 1993, Kemp filed a motion seeking discovery of evidence concerning the alleged kidnaping of the couple, which the trial court granted.

Apparently, the State did not provide Kemp with the information requested, and on May 26, 1993, counsel filed two motions in limine to preclude the presentation of any evidence of any prior or subsequent bad acts by Mr. Kemp. One of the motions specifically requested that the kidnaped couple “not be allowed to testify as to any inappropriate sexual behavior by Mr. Kemp towards [the husband].”

On June 2, 2003, the case was called for trial in the Superior Court of Arizona, in and for the County of Pima. The judge was intent on selecting a jury, and when Kemp's attorney, Mr. Larsen, noted that there were unresolved pretrial motions, the court indicated that it intended to begin jury selection “before we hear anything on the motion for change of venue.” The prosecutor, Kenneth Peasley, tendered a new witness list, which included the husband abducted in Flagstaff. He indicated that the husband would present evidence concerning: (1) Kemp's silence to statements made by Logan in the husband's presence; (2) the husband's kidnaping; and (3) that “in the room in Durango Mr. Kemp attempt[ed] to sexually molest and assault” the husband. Peasley further claimed that the sexual assault was “proof of all motives that Mr. Kemp has for the killing, and also explains conditions here in Tucson.” After Peasley's comments, the trial judge stated “I don't need to hear from you on that now, Mr. Larsen.”

A little later, before potential jurors entered the courtroom, Larsen reiterated that he wanted to know “prior to trial what physical evidence and exhibits” the prosecutor intends to use. The prosecutor apparently stated that he intended to introduce materials seized from Kemp, including photographs of naked men, but would make no reference to Kemp's sexually explicit materials and alleged homosexual act in his opening statement. The trial court indicated that the matter would be considered later.

The trial court then asked the prosecutor and defense counsel whether they were ready to proceed and each answered yes. The prospective jurors were sworn in and the judge proceeded to voir dire the jury panel. When the trial judge asked counsel to pass on the panel, defense counsel stated that he had a number of questions. Defense counsel requested a ruling on the evidence that the prosecutor sought to introduce “regarding any sexual matters as it pertains to both [victims].” Larsen was particularly concerned with the possible impact of allegations of sexual molestation on a juror whose father-in-law had been convicted of an incest charge. The trial judge proceeded to ask additional questions of that juror, but did not mention homosexuality. When defense counsel objected that the questions did not begin “to approach what was necessary,” the trial judge responded that Larsen had made his record.