32nd murderer executed in U.S. in 2013

1352nd murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

2nd murderer executed in Arizona in 2013

36th murderer executed in Arizona since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(32) |

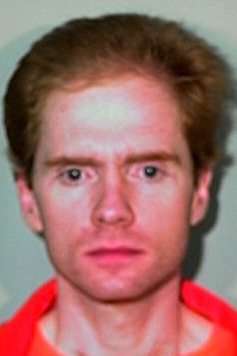

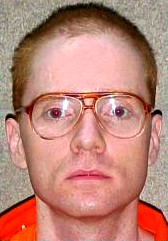

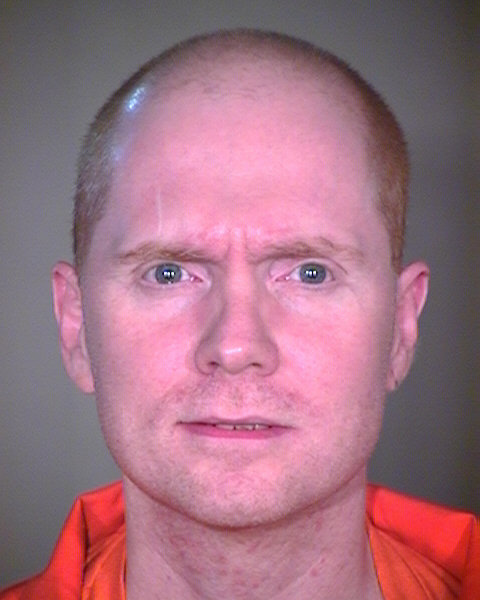

Robert Glen Jones Jr. W / M / 26 - 43 |

Clarence "Chip" O'Dell III W / M / 47 Thomas Hardman W / M / 26 Maribeth Munn W / F / 53 Carol Lynn Noel W / F / 50 Arthur "Taco" Bell W / M / 54 Judy Bell W / F / 46 |

05-30-96 06-13-96 06-13-96 06-13-96 06-13-96 |

.380 Handgun |

Summary:

Jones and accomplices David and Scott Nordstrom drove to the Moon Smoke Shop intent on committing a Robbery. David waited in the truck while Jones and Scott Nordstrom armed themselves and went inside. They followed a customer, Chip O'Dell, into the store and shot him in the head without saying a word, killing him. There were 4 employees inside. Unprovoked, they immediately started shooting at the other employees. Thinking the others were dead, employee Mark Naiman ran out of the store and called 9-1-1 at a payphone. One of the men followed employee Tom Hardman into a back room and shot him fatally in the head as he lay on the floor. Another employee was shot in the face and arm, but survived. Minutes later, the two men jumped in the waiting truck and took off. According to the testimony of David Nordstrom, when they got into the vehicle Jones said he had shot two people, and Scott Nordstrom responded that "I shot one."

Two weeks later, the Fire Fighters Union Hall was robbed. Inside, four bodies were found, all shot dead: Union member Maribeth Munn, the bartender Carol Lynn Noel, and a couple, Judy and Arthur Bell. $1300 had been taken from the open cash register. The coroner concluded that the bartender had been shot twice, and that the other three victims were shot through the head at close range as their heads lay on the bar. David Nordstrom testified at trial that that evening Jones entered David's father's house and told him that he and Scott Nordstrom had robbed the Union Hall. He stated that because the bartender could not open the safe, Scott kicked her and shot her. Jones said he then shot the three other witnesses in the back of the head.

A month later, Richard Roels was bound with duct tape and shot in the head at his phoenix home. Police traced purchases with Roels credit card to Jones, who upon arrest was wearing the watch that Roels received upon his retirement. Jones pled guilty and was sentenced to Life Without Parole. Accomplice Scott Nordstrom was also convicted of Murder, was sentenced to death, and is awaiting execution.

Citations:

State v. Jones, 197 Ariz. 290, 4 P.3d 345 (Ariz. 2000), Cert. denied 121 S. Ct. 1616 (2001). (Direct Appeal)

State v. Nordstrom, 200 Ariz. 229, 25 P.3d 717 (Ariz. 2001). (Companion Case - Direct Appeal)

Jones v. Ryan, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 12887 (D. Ariz. Jan. 28, 2010). (Habeas)

Final Words:

"Love and respect my friends and family, and hope my friends are never here."

Final / Special Meal:

Jones declined a special last meal so he was given the same meal provided to the other inmates at the prison, which consisted of a beef patty, mashed potatoes with brown gravy, a serving of carrots, two slices of wheat bread, a slice of glazed cake and a powdered juice drink. The meal was served to him Tuesday night.

Internet Sources:

Arizona Department of Corrections

INMATE 070566 - JONES, ROBERT GLENN

JONES, ROBERT

DOB:12/25/1969

GENDER: MALE

HEIGHT: 71 inches

175 pounds

HAIR COLOR: RED

EYE COLOR: BLUE

RACE: CAUCASIAN

ADMISSION: 02/17/2000

On May 30, 1996, Robert Jones and Scott Nordstrom entered the Moon Smoke Shop in Tucson. Jones immediately shot a customer in the head; one employee escaped, two others were shot at by Jones behind the counter (one was injured but survived and the other was not hit), and another employee was executed by Scott Nordstrom with two shots to the head. Money was taken which was shared with lookout David Nordstrom.

On June 13, 1996, Robert Jones and Scott Nordstrom entered the Firefighters Union Hall in Tucson. Three customers were executed with shots to the head by Jones and a wallet taken from one of them. The bartender was shot dead by Scott Nordstrom after being unable to open a safe; money was taken from a cash register. Both cases were solved when David Nordstrom contacted the police.

Presiding Judge: John S. Leonardo

Prosecutor: David White

Defense: Eric Larsen and David Braun

Start of Trial: June 17, 1998

Verdict: June 26, 1998

Sentencing: December 7, 1998

Aggravating Circumstances: Convicted of other offenses for which life sentence or death penalty impossible; Convicted of other "serious" offenses; Pecuniary gain; On parole at time of offense; Multiple homicides

Mitigating Circumstances: Statutory - none proven; Non-statutory-dysfunctional family family support good behavior/demeanor during trial

JONES, Robert Glenn ADC#070566 Pima County CR57526 sentenced as follows:

Count I First Degree Murder as to Thomas Hardman, committed on 5/30/96, sentenced to DEATH.

Count 2 First Degree Murder as to Clarence O'Dell, committed on 5/30/96, sentenced to DEATH.

Count 8 First Degree Murder as to Maribeth Munn, committed on 6/13/96, sentenced to DEATH.

Count 9 First Degree Murder as to Carol Lynn Noel, committed on 6/13/96, sentenced to DEATH.

Count 10 First Degree Murder as to Arthur Bell, committed on 6/13/96, sentenced to DEATH.

Count 11 First Degree Murder as to Judy Bell, committed on 6/13/96, sentenced to DEATH.

These sentences are CONSECUTIVE, one to the other.

Non-Capital Counts

Count 3 Attempted First Degree Murder as to Steve Vetter, committed on 5/30/96, sentenced to 15 years concurrent with counts 4 & 13, consecutive to all other counts.

Count 4, 5, 6 Armed Robbery , committed on 5/30/96, sentenced to 15 years each count. Count 4 is concurrent with counts 3 & 13, consecutive to all other counts; count 5 is concurrent with count 14, consecutive to all other counts; count 6 is concurrent with count 15, consecutive to all other counts,

Count 7 Burglary in the First Degree, committed on 6/13/96, sentenced to 15 years consecutive to all other counts.

Count 12 Burglary in the First Degree, committed on 5/30/96, sentenced to 15 years consecutive with all other counts.

Count 13, 14, 15 Aggravated Assault, Deadly Weapon/Dangerous Instrument, committed on 5/3 0/96, sentenced to 10 years each count. Count 13 concurrent with counts 3 & 4, consecutive to all other counts; count 14 concurrent with count 5, consecutive to all other counts; count 15 concurrent with count 6, consecutive to all other counts.

Co-defendant is Scott Nordstrom ADC#086114 On May 30, 1996 Robert Jones and Scott Nordstrom entered the Smoke Shop at Grant and First Avenue in Tucson, AZ. Victim two a customer was standing inside the door was shot once in the back of his head with a handgun by Jones. Three employees were ordered to the floor where they were shot by Jones. Victim four was struck twice. Victim six was ordered to open both registers and he heard the shots when Jones shot the others when he was on his way to the second register. Victim six fled upon hearing the shots, out the front door of the business without injury. A fourth employee, victim one was on the opposite side of the room it is believed that he fled to a back room when the shooting started, Scott Nordstrom followed him, made him lay face down on the floor, and shot him twice in the back of the head with a .380 caliber handgun. Robert Jones and Scott Nordstrom then left the shop, got into a waiting truck parked behind the business, driven by David Nordstrom.

On June 13, 1996 between 9:15 and 9:30 p.m. Robert Jones and Scott Nordstrom entered the Union Hall on East Benson Highway where victim twelve was the bartender and three customers, victims 9, 15 and 17 were seated at the bar. Jones had the customers bend forward with their faces flat on the bar and he shot each one once in the back of the head with a nine millimeter handgun. Victim 15 also showed evidence of being struck with a blunt object in the face and his wallet was stolen. Victim 12 was taken to the back room to open the safe, she did not have the combination, she was struck or kicked in the face, her blood was found on the safe. She was found behind the bar shot once in the back and once in the head by Nordstrom with a .380 caliber handgun. The victims were found by customers that arrived approximately 9:30 p.m. after the defendants had left.

Other Unrelated charges from Maricopa County CR 1996-012723

Count I Burglary in the Second Degree, committed on 8/18/96 and 8/19/96, sentenced to 3.5 years.

Count 3 Armed Robbery, committed on 8/20/96, sentenced to 10.5 years consecutive to count 1.

Count 4 Burglary in the Second Degree, committed on or between 8/22/96 and 8/23/96, sentenced to 3.5 years consecutive to count 3.

Count 6 Burglary in the Third Degree, committed on or about 8/23/96, sentenced to 2.5 years consecutive to count 4.

Count 8 Burglary in the Second Degree, committed on or about 8/23/96, sentenced to 3.5 years consecutive to count 6. Count 10 First Degree Murder, committed on 8/23/96, sentenced to Natural Life consecutive to count 42.

Count 16 Fraudulent Schemes and Artifices, committed on or about 8/23/96, sentenced to 5 years consecutive to count 8. Count 18 Armed Robbery, committed or about 8/24/96, sentenced to 10.5 years concurrent with counts 21 & 41, consecutive to count 16.

Count 19 Aggravated Assault, committed on or about 8/24/96, sentenced to 7.5 years concurrent with counts 20, 22, 25, 26 & 27, consecutive to counts 18, 21 & 41.

Count 20 Aggravated Assault, committed on or about 8/24/96, sentenced to 7.5 years concurrent with counts 19, 22, 25, 26 & 27, consecutive to counts 18, 21 & 41. Count 21 Armed Robbery, committed on or about 8/24/96, sentenced to 10.5 years concurrent with counts 18 & 41, consecutive to count 16.

Count 22 Aggravated Assault, committed on or about 8/24/96, sentenced to 7.5 years concurrent with counts 19, 20, 25, 26 & 27, consecutive to counts 18, 21 & 41.

Count 23 First Degree Burglary, committed on or about 8/24/96, sentenced to 7.5 years consecutive to counts 19, 20, 22, 25, 26 & 27.

Count 24 Attempted Armed Robbery, committed on or about 8/24/96, sentenced to 7.5 years concurrent with count 28, consecutive to count 23.

Count 25 Aggravated Assault, committed on or about 8/24/96, sentenced to 7.5 years concurrent with counts 19, 20, 22, 26 & 27, consecutive to counts 18, 21 & 41.

Count 26 Aggravated Assault, committed on or about 8/24/96, sentenced to 7.5 years concurrent with counts 19, 20, 22, 25 & 27, consecutive to counts 18, 21 & 41.

Count 27 Aggravated Assault, committed on or about 8/24/96, sentenced to 7.5 years concurrent with counts 19, 20, 22, 25 & 26, consecutive to counts 18, 21 & 41.

Count 28 Attempted Armed Robbery, committed on or about 8/24/96, sentenced to 7.5 years concurrent with count 24, consecutive to count 23.

Count 29 Attempted First Degree Murder, committed on or about 8/24/96, sentenced to 10.5 years consecutive to counts 24 & 28.

Count 30 Theft, committed on or about 8/24/96, sentenced to 3.5 years consecutive to count 29.

Count 41 Armed Robbery, committed on or about 8/24/96, sentenced to 10.5 years concurrent with counts 18 & 21, consecutive to count 16.

Count 42 Unlawful Flight from a Law Enforcement Vehicle, committed on or about 8/24/96, sentenced to 1. 5 years consecutive to count 30.

NEWS RELEASE

October 23, 2013

Convicted Murderer Robert Jones Executed

FLORENCE (Wednesday, October 23, 2013) – Arizona Department of Corrections inmate Robert Jones, #070566, was executed by lethal injection at 10:52 a.m. Wednesday, October 23rd at the Arizona State Prison Complex - Florence. The one drug protocol was administered at 10:35 a.m. and the execution was completed 17 minutes later. Jones’s last words were: "Love and respect my friends and family, and hope my friends are never here."

Jones declined a special last meal so he was given the same meal provided to the other inmates at the prison, which consisted of a beef patty, mashed potatoes with brown gravy, a serving of carrots, two slices of wheat bread, a slice of glazed cake and a powdered juice drink. The meal was served to him Tuesday night.

Jones was convicted and sentenced to death as a consequence of the two separate shootings in 1996 that left six people dead. Scott Nordstrom was also sentenced to death for his role in the crimes. Jones was also sentenced to life in prison for the murder of Richard Roels of Phoenix that same year.

AZCentral - The Arizona Republic

"Man who killed 7 in 1996 Arizona crime spree is put to death," by Michael Kiefer. (The Republic 10/23/13)

FLORENCE-- Robert Jones never looked up at the families of the men and women he killed. He didn't apologize. He didn't explain himself. He just closed his eyes and went to sleep, media witnesses said, the second Arizona Death Row inmate to be executed this month.

Jones, 43, was sentenced to death for the 1996 murders of Chip O' Dell, Tom Hardman, Carol Lynn Noel, Maribeth Munn and Judy and Arthur Bell during two armed robberies in Tucson, and was sentenced to life in prison for the murder of Richard Roels in Phoenix.

Jones met with his attorneys Tuesday night to reminisce about his life. He declined the traditional special last meal afforded to condemned prisoners. "It's just another meal and there's nothing special about the day to me," he told Assistant Federal Defender Dale Baich. Instead, he ate what the other inmates ate: a beef patty, mashed potatoes with brown gravy, a serving of carrots, two slices of wheat bread, a slice of glazed cake and a powdered juice drink.

On Wednesday morning he was strapped to a gurney in Housing Unit 9, which is what prison officials call the death house. And when the execution medical staff had difficulty inserting the catheters that would deliver the barbiturate pentobarbital in his arm, Jones joked that if they let his hands free, he could do it himself. Unable to get two lines into his arms, the medical staff then surgically implanted a catheter in Jones' groin. The scheduled 10 a.m. execution was delayed because of those difficulties.

"Love and respect my friends and family," Jones said as his last words, "and hope my friends are never here." The drug was administered at 10:35 a.m. and Jones was pronounced dead at 10:52. He never looked toward the witnesses on the other side of a window from him, and mostly kept his eyes shut, breathing heavily and then going to sleep.

More than 20 relatives of the victims witnessed the execution and several spoke afterwards, their voices filling with emotion and anger. "Personally, I think this was too easy," said Carson Noel, the son of Carol Lynn Noel, referring to how easily Jones died. "This was the second hardest thing I've ever done," he said. "The first was putting my mom to rest." Christopher Bell, the son of Judy and Arthur Bell, said, "17 years is too long. And we still have a lifetime ahead to heal." Then he thought a moment. "And we're never going to heal." Several of the victims remarked that they would not get closure until Jones' accomplice in six of the murders, Scott Nordstrom, is executed as well.

Jones and his accomplices killed ruthlessly. On May 30, 1996, two men burst through the doors of the Moon Smoke Shop in Tucson. A red-haired man, believed to be Jones, wearing a black cowboy hat and dark sunglasses immediately shot O’Dell in the head, killing him, survivors said. O’Dell was a customer in the store. Store employees dropped to the floor behind the counter as the gunman continued to fire. The gunman then chased Tom Hardman to a back room, where the gunman killed him, as well. Two employees fled; a third was wounded. One of the survivors saw a light-colored pickup truck speeding away from the scene with two people in it.

Two weeks later, on June 13, 1996, four bodies were found at the Fire Fighters Union Hall, also in Tucson: Noel, the bartender, and club members Munn and the Bells. Noel had been beaten and shot twice; the others were apparently shot in the back of the head after being made to put their heads on the bar. Police believed $1,300 was taken from the cash register.

Roels was killed more than a month later at his house in central Phoenix on Aug. 23, 1996. Phoenix police quickly tracked Roels’ stolen credit cards and found that they had been used in the hours after the killing to buy pizzas and a pair of cowboy boots. Then, as the killers tried to buy ammunition at a gun-supply store, a suspicious store clerk called police and turned over surveillance photos of the two men. The police then sent the photos to local hotels to see if anyone recognized the two men. Staff at a motel near Interstate 17 and Indian School Road identified them.

Jones and an accomplice named Stephen Coats were leaving the motel as a police helicopter tracked them. The two men led police on a car chase through city streets that reached speeds of 80 mph. Then, the killers stopped at a car dealership, hot-wired a Corvette and sped down Camelback Road at 100 mph. They eluded police on Arizona 51 at top speeds of nearly 130 mph. The Corvette ran out of gas in Tempe, where Jones and Coats split up. Coats forced his way into an apartment at gunpoint; Jones hot-wired a Porsche that he crashed.

When he was arrested, Jones was wearing the watch that Roels received from the newspaper on his retirement. The link to the Tucson murders came when a man named David Nordstrom went to Tucson police and told them that he had been with Jones and his own brother Scott Nordstrom on the day they robbed the Moon Smoke Shop. David, who was on parole and wearing an electronic-monitoring device, said he was driving the pickup truck when the first murders and robbery were committed. Jones fit the description of the gunman; for that matter, so did David Nordstrom. But David pinned the murders on Scott Nordstrom and Jones. He also said he knew of the other robbery and murders from what Jones and Scott told him. David Nordstrom was initially charged in some of the murders, but the charges were dropped in exchange for his testimony. Jones and Scott Nordstrom were both sentenced to death. Coats, who had nothing to do with the Tucson robberies, was sentenced to life in prison for Roels’ murder.

Jones was born on Christmas Day 1969 in Tyler, Texas. Jones’ natural father was absent from the home during Jones’ childhood, according to court records. Jones’ two successive stepfathers beat him, and when he became big enough to defend himself at about age 15, he was kicked out of his mother’s house. Jones dropped out of school and began using cocaine and methamphetamine.

His defense attorneys maintained to the end that the Tucson murders were a case of mistaken identity, pointing out that David Nordstrom resembled Jones. There was no physical evidence that linked Jones to the murders. However, he pleaded guilty to Roels’ murder.

But in the last weeks, state and federal courts refused to grant a stay of execution. Jones and another death-row inmate, Edward Schad, filed a lawsuit against the state to get the Arizona Department of Corrections to reveal the source of the barbiturate pentobarbital, which would be used in both men’s executions. The two men appeared side by side on closed-circuit TV during the federal court hearings earlier this month. The judge ordered the Corrections Department to provide the information, which it did, although the inmates’ attorneys asked for more. Schad was executed Oct. 9. The suit will continue even after Jones’ death.

Jones did not attend his clemency hearing last week, claiming that there was no chance that the Arizona Board of Executive Clemency would commute his sentence or grant him a reprieve.

Ryanne Costello, the daughter of Richard Roels, was among the witnesses to Wednesday’s execution. She has spent much of the last 17 years wondering about her father’s murder and even tried to set up meeting with Jones to ask him what her father’s last words had been. She wanted closure. She wanted to understand why her father was dead and how he faced his last moments. “I was prepared for it,” Costello said. “He could have told me anything.” After the execution, Costello said, "I can't explain how relieved I am, because I feel I can move on."

"Arizona executes man convicted of killing six in 1996," by David Schwartz. (Wed Oct 23, 2013 3:56pm EDT)

(Reuters) - An Arizona inmate convicted of murdering six people during two robberies in Tucson in 1996 was executed by lethal injection on Wednesday, the state attorney general said. Robert Glen Jones Jr., 43, was pronounced dead at 10:52 a.m. (1752 GMT) inside the state prison in Florence about 60 miles southeast of Phoenix, Arizona Attorney General Tom Horne said. It was the second execution in Arizona this month.

"(I) love and respect my friends and family, and hope my friends are never here," Jones said immediately before he was put to death, according to Doug Nick, a spokesman for the Arizona Department of Corrections. Jones had declined any special last meal. More than a dozen relatives of the victims but no member of Jones's family witnessed the execution, Nick said.

Jones was convicted in 1998 for the murders committed with accomplice Scott Nordstrom, who remains on Arizona's death row. Court records show that Jones entered a smoke shop with Nordstrom on May 30, 1996, and killed his first victim with a gunshot to the head and wounded another man. Nordstrom killed another victim who tried to flee the business. The two men grabbed money from a cash register and fled, jumping into a waiting pickup truck that was parked behind the shop with David Nordstrom, Scott's brother, behind the wheel.

In the second incident on June 13, Jones and Nordstrom burst into a firefighters' union hall. Jones had three customers bend forward with their faces flat on the bar and killed each with a bullet to the head, prosecutors said. Nordstrom killed the female bartender after she was unable to open a safe.

The cases were solved when David Nordstrom contacted authorities. Jones was convicted in June 1998 of six counts of murder and attempted first-degree murder, aggravated assault, armed robbery and burglary.

Arizona has executed 36 people since the state reinstated the death penalty in 1992. Two weeks ago, Edward Harold Schad, 71, was put to death for strangling a 74-year-old man to death and fleeing in the victim's new Cadillac more than three decades ago. Thirty-two people have been put to death in the United States this year, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

"Robert Jones executed for six murders," by Patrick McNamara. (October 24, 2013 12:00 am)

The man convicted of gunning down six people in cold blood in a pair of 1996 robberies died quietly Wednesday in Housing Unit 9 at the Arizona Department of Corrections prison in Florence.

In stark contrast to the violent and bloody deaths Robert Glen Jones’ inflicted upon his victims, Jones appeared to fall peacefully asleep after prison officials administered the lethal dose of phenobarbital. “I think it was too easy,” said Carson Noel?, whose mother was one of the people Jones and accomplice Scott Nordstrom shot and killed. Noel said Jones wasn’t made to suffer the way his victims were.

Jones, 43, and Nordstrom were found guilty of the Moon Smoke Shop and Firefighter’s Union Hall murders in 1998 and sentenced to die for the crimes. Nordstrom remains on death row. Arthur “Taco” Bell, 54; Judy Bell, 46; Maribeth Munn, 53; and Carol Lynn Noel, 50, were shot and killed during a robbery at the Firefighter’s Union Hall. Clarence Odell III, 47; and Thomas Hardman, 26, were killed in the Moon Smoke Shop.

“All I could think of was my mom and dad,” said Christopher Bell?, son of Arthur and Judy Bell. Bell said the 17 years since his parents were slain was too long to wait for the death sentence to be carried out. Even with one of the killers of his parents dead, Bell said his family would always bear the scars left by their deaths. “It’s never going to heal — it never will,” Bell said. Following the murders, Bell said he moved to Texas to escape some of the memories and make a new start.

Jones steadfastly maintained his innocence over the years. Prior to the execution, however, he declined to attend his clemency board hearing, where an attorney represented him in a plea for a stay. He also refused a special meal the day before the death sentence was carried out, eating instead the same meal other death-row inmates had: beef patties, mashed potatoes, gravy, carrots, two slices of wheat bread, glazed cake and a powdered-juice drink.

Before the administration of the lethal dose, Jones offered no apologies and expressed no remorse. “Love and respect my family and friends and I hope my friends are never here,” were the last words Jones spoke.

At times he even joked with prison staffers as they struggled to find viable veins to insert the IVs, suggesting with his years of experience shooting “dope” he could find the vein himself if they freed his hand. Witnesses watched on television monitors as prison and medical staff worked for nearly an hour around Jones before opting to administer the lethal injection drugs into the femoral artery of his right leg. When the curtains that block out the glass between the observation room and death chamber were opened, the death warrant was read to Jones. The drugs were administered at 10:35 a.m.

Jones lay nearly motionless with his eyes closed moving only his right hand periodically. His chest made one upward heave before he stopped moving completely. As the drug worked its way through his system, the muscles in his face relaxed and his mouth fell slightly slack. Soon the color began to run from his face, taking on a pale gray shade. After nearly 10 minutes of silence, a medical technician checked Jones’ vital signs and pronounced him “officially sedated.” A few minutes later, Arizona Department of Corrections Director Charles L. Ryan ?stepped into the chamber and pronounced Jones officially dead at 10:52 a.m.

For Noel, attending the execution was a difficult decision. “This is probably the second-hardest thing I’ve had to do,” he said. “The first was laying my mom to rest.”

It was Arizona’s 36th execution since 1992. Wednesday’s execution was the second in Arizona this month. Edward Schad?, 71, was executed Oct. 9 for killing a Bisbee man in 1978. No execution date has been set for Nordstrom.

"Firefighters Union Hall murders: 17 years later," by Som Lisaius. (Sep 12, 2013 7:11 PM EDT)

TUCSON, AZ (Tucson News Now) - It's been 17 years since one of the most horrific crime sprees in Tucson history. What started as a series of armed robberies ultimately ended in the murder of six people, four of them at the Firefighters Union Hall on East Benson Highway. For the daughter of one of those victims, it's one day she'll never forget. June 13th, 1996.

Seven and half months pregnant at the time, Teresa Munn just got home from her first birthing class when she turned on the TV. "And we had come home and saw a news report on the news saying coming up at 10 there was a quadruple homicide at the Firefighters Union Hall," Munn said. "And behind the reporter in the background we could see my mother's car, so we knew she was in there that night." Sadly, Maribeth Munn was one of four people murdered that night as two thugs got away with just $850. "They had gone in, Robert Jones and Scott Nordstrom to rob them -- and wanted to leave no witnesses," Munn said.

Exactly two weeks earlier the same to men shot and killed two other people as they robbed a Moon Smoke Shop in midtown. Ballistics left at both scenes connected the crimes to the same two suspects. 17 years later, while Scott Nordstrom remains on death row, his execution still uncertain -- Robert Jones is now counting the days until his lethal injection. It's scheduled for October 23rd this year -- and Teresa Munn will be there.

"Since he's actually the one that shot my mother, he saw her die," Munn says..."I will see him die and that will close this book." A book that's had many chapters over the last decade and a half. Teresa's brother Scott was married to the daughter of two others killed in the union hall that night. And when she eventually gave birth to her first and only son, Munn says, "The nurse who was in the hospital with me when I was delivering my son is the sister of Chip O'Dell, who was killed at the Moon Smoke Shop." An interesting symmetry to so many lives marred by tragedy.

For Teresa, she's looking forward to finally putting all of this behind her. She knows nothing can change the past. But fond memories of her mother will always be the same. "She was only four-foot-eleven, and growing up in the '70s we had a huge Ford station wagon," Munn says, smiling. "Taking road trips, this tiny woman could reach all the way in the back and smack us -- so yeah...she was tough."

David Nordstrom, the state’s key witness, was released from prison in January 1996, after serving his sentence for a theft conviction. At that time, he took up residence in his father’s home in Tucson, where he was under “home arrest” status and monitored by an ankle monitor. The home arrest was related to his prior theft conviction, and as a term of the arrest, he had to be inside his father’s home by a certain time every evening.

During this period of home arrest, he reestablished his friendship with Robert Jones. Scott Nordstrom, David’s brother, also returned to Tucson and spent time with David and Jones. Sometime before April 1996, David obtained a .380 semiautomatic pistol from a friend, which he gave to Jones after Jones requested it for protection. On May 30, 1996, Scott and Jones picked up David in Jones’s truck, an old white Ford pickup. Jones was wearing his usual attire: a long-sleeved western shirt, Levi’s, boots, sunglasses, and a black cowboy hat. In a parking lot near the Tucson Medical Center, Jones spotted a car that he thought he could steal. Although he failed to start the car, Jones found a 9mm pistol under the seat and left with it, stating, “I’ve got my gun now.”

As the three continued driving, they began discussing the possibility of a robbery, and Jones gave Scott the .380 pistol. Jones then suggested that they rob the Moon Smoke Shop. He parked behind the store, telling David that he and Scott would go in, rob it, and be right out. David then heard gunfire from inside, after which, Jones and Scott left the shop and jumped into the truck. David drove up the alley, exited onto the surface street, and headed toward the freeway. Jones stated, “I shot two people,” and Scott stated, “I shot one.” Jones then split the money from the robbery with David and Scott.

The survivors from the robbery testified that four employees were in the store at the time of the robbery: Noel Engles, Tom Hardman, Steve Vetter, and Mark Naiman, a new employee on the job for the first time. Just before the robbery, Engles was standing behind the counter, and Vetter and Naiman were kneeling behind it. Hardman was sitting behind another counter, and no customers were in the store. Jones and Scott followed a customer, Chip O’Dell, into the store and immediately shot him in the head. As the door buzzer indicated someone had entered the store, Engles, Vetter, and Naiman all heard the gunshot. Because all three were concentrating on the stock behind the counter, however, none of them saw the robbers or O’Dell enter. Engles looked up to see a robber in a long-sleeved shirt, dark sunglasses, and a dark cowboy hat wave a gun at him and yell to get down. Naiman recognized the gun as a 9mm. Engles noticed a second robber move toward the back room and heard someone shout, “Get the fuck out of there!”

Engles dropped to his knees and pushed an alarm button. The gunman at the counter nudged Naiman in the head with his pistol and demanded that he open the register. After he did so, the gunman reached over the counter and began firing at the others on the floor. Thinking the others were dead, Naiman ran out of the store and called 911 at a payphone. On the floor behind the counter, Engles heard shots from the back room and, realizing the gunmen had left the store, ran out the back door. While running up the alley to get help, he saw a light-colored pickup truck carrying two people, which turned sharply onto the surface street, despite heavy traffic. All survivors agreed that no one had offered any resistance to the gunmen, and that the shootings were completely unprovoked. Naiman and Engles survived, as did Vetter, despite the shots to his arm and face. Chip O’Dell died from a bullet through his head, which had been fired from close range. Hardman, who had fled to the back room when the gunmen entered, had been shot fatally in the head from above as he lay on the floor. Three 9mm shell casings were found in the store, one beside Mr. O’Dell and two near the cash register. Two .380 shells were found near Hardman’s body.

Two weeks after the robbery, Naiman met with a police sketch artist who used his description of one of the gunmen to create a composite drawing. Two weeks after the Moon Smoke Shop robbery, the Fire Fighters Union Hall was robbed. The Union Hall was a club owned by the firefighters and their guests, which contained a bar, bingo hall, and snack bar. Members entered using key cards, and the bartender buzzed in guests. When member Nathan Alicata arrived at 9:20 p.m., he discovered the bodies of member Maribeth Munn, the bartender, Carol Lynn Noel, and a couple, Judy and Arthur “Taco” Bell. During the ensuing investigation, the police found three 9mm shell casings, two live 9mm shells, and two .380 shell casings. Approximately $1300 had been taken from the open cash register.

The coroner, who investigated the bodies at the scene, concluded that the bartender, Carol, had been shot twice, and that the other three victims were shot through the head at close range as their heads lay on the bar. Carol also suffered blunt force trauma which caused a bleeding laceration to the side of her mouth, and Arthur had a contusion on the right side of his head in a shape consistent with a pistol.

On August 23, 1996, Ryanne Costello had lunch with her father, Robert Roels, at his house in central Phoenix on Aug.23, 1996. A few hours later, he was murdered. If the killers had arrived two hours earlier, "the homicide detective said they would have killed me, too," Costello said. Roels was bound with duct tape and shot in the head. Phoenix police quickly tracked Roels' stolen credit cards and found that they had been used in the hours after the killing to buy pizzas and a pair of cowboy boots. Then, as the killers tried to buy ammunition at a gun-supply store, a suspicious store clerk called police and turned over surveillance photos of the two men. The police then sent the photos to local hotels to see if anyone recognized the two men. Staff at a motel near Interstate 17 identified them.

Jones and an accomplice named Stephen Coats were leaving the motel as a police helicopter tracked them. The two men led police on a car chase through city streets that reached speeds of 80 mph. Then the killers stopped at a car dealership, hot-wired a Corvette and sped down another road at 100 mph. They eluded police on Arizona 51 at top speeds of nearly 130 mph. The Corvette ran out of gas in Tempe, Ariz., where Jones and Coats split up. Coats forced his way into an apartment at gunpoint; Jones hot-wired a Porsche that he crashed. When he was arrested, Jones was wearing the watch that Roels, a retired Arizona Republic executive, received from the newspaper on his retirement.

The link to the Tucson murders came when a man named David Nordstrom went to Tucson police and told them that he had been with Jones and his own brother, Scott Nordstrom, on the day they robbed the Moon Smoke Shop. David Nordstrom, who was on parole and wearing an electronic-monitoring device, said he was driving the pickup truck when the first murders and robbery were committed. Jones fit the description of the gunman; for that matter, so did David Nordstrom. But David pinned the murders on Scott Nordstrom and Jones. He also said he knew of the other robbery and murders from what Jones and Scott Nordstrom told him.

David Nordstrom was initially charged in some of the murders, but the charges were dropped in exchange for his testimony. Jones and Scott Nordstrom were both sentenced to death. Coats, who had nothing to do with the Tucson robberies, was sentenced to life in prison for Roels' murder.

David Nordstrom testified at trial that on the day of the Union Hall murders, his brother Scott gave him a ride home, where he remained the rest of the evening. David’s parole officer produced records at trial verifying that David’s ankle-monitoring unit indicated he had not left his father’s home on the night of the murders. Late that evening, Jones entered David’s father’s house and began telling David what had happened. Jones admitted to David that he and Scott had robbed the Union Hall. He stated that because the bartender could not open the safe, Scott kicked her and shot her. Jones said he then shot the three other witnesses in the back of the head. Jones, Scott, and David disposed of the guns by throwing them into a pond south of Tucson, and Scott and David burned one of the victim’s wallets at another location.

David kept the secret until he saw an appeal on the television for information. At that time, he told his girlfriend, Toni Hurley, what he knew. Hurley eventually made an anonymous call, which led to David’s contact with the police, and an ultimate release of the information.

Arizona Death Row Prisoners Slideshow (AZCentral.Com)

Arizona's History of Executions since 1992 (AZCentral.Com)

Wikipedia: List of People executed in Arizona Since 1976

1. Donald Eugene Harding White 43 M 06-Apr-1992 Lethal gas Allen Gage, Robert Wise, and Martin Concannon

2. John George Brewer White 27 M 03-Mar-1993 Lethal injection Rite Brier

3. James Dean Clark White 35 M 14-Apr-1993 Lethal injection Charles Thumm, Mildred Thumm, Gerald McFerron, and George Martin

4. Jimmie Wayne Jeffers White 49 M 13-Sep-1995 Lethal injection Penelope Cheney

5. Darren Lee Bolton White 29 M 19-Jun-1996 Lethal injection Zosha Lee Picket

6. Luis Morine Mata Latino 45 M 22-Aug-1996 Lethal injection Debra Lee Lopez

7. Randy Greenawalt White 47 M 23-Jan-1997 Lethal injection John Lyons, Donnelda Lyons, Christopher Lyons, and Theresa Tyson

8. William Lyle Woratzeck White 51 M 25-Jun-1997 Lethal injection Linda Leslie

9. Jose Jesus Ceja Latino 42 M 21-Jan-1998 Lethal injection Linda Leon and Randy Leon

10. Jose Roberto Villafuerte Latino 45 M 22-Apr-1998 Lethal injection Amelia Shoville

11. Arthur Martin Ross White 43 M 29-Apr-1998 Lethal injection James Ruble

12. Douglas Edward Gretzler White 47 M 03-Jun-1998 Lethal injection Michael Sandsberg and Patricia Sandsberg

13. Jesse James Gillies White 38 M 13-Jan-1999 Lethal injection Suzanne Rossetti

14. Darick Leonard Gerlaugh Native American 38 M 03-Feb-1999 Lethal injection Scott Schwartz

15. Karl-Heinz LaGrand White 35 M 24-Feb-1999 Lethal injection Kenneth Hartsock

16. Walter Bernhard LaGrand White 37 M 03-Mar-1999 Lethal gas

17. Robert Wayne Vickers White 41 M 05-May-1999 Lethal injection Wilmar Holsinger

18. Michael Kent Poland White 59 M 16-Jun-1999 Lethal injection Cecil Newkirk and Russell Dempsey

19. Ignacio Alberto Ortiz Latino 57 M 27-Oct-1999 Lethal injection Manuelita McCormack

20. Anthony Lee Chaney White 45 M 16-Feb-2000 Lethal injection John B. Jamison

21. Patrick Gene Poland White 50 M 15-Mar-2000 Lethal injection Cecil Newkirk and Russell Dempsey

22. Donald Jay Miller White 36 M 08-Nov-2000 Lethal injection Jennifer Geuder

23. Robert Charles Comer White 50 M 22-May-2007 Lethal injection Larry Pritchard and Tracy Andrews

24. Jeffrey Timothy Landrigan Native American 50 M 26-Oct-2010 Lethal injection Chester Dean Dyer

25. Eric John King African American 47 M 29-Mar-2011 Lethal injection Ron Barman and Richard Butts

26. Donald Beaty White 25-May-2011 Lethal Injection Christy Ann Fornoff

27. Richard Lynn Bible 30-June-2011 Lethal Injection Jennifer Wilson

28. Thomas Paul West 19-July-2011 Lethal Injection Don Bortle

29. Robert Henry Moorman 29-Feb-2012 Lethal injection Roberta Maude Moorman

30. Robert Charles Towery 08-Mar-2012 Lethal injection Mark Jones

31. Thomas Arnold Kemp 25-Apr-2012 Lethal injection Hector Juarez

32. Samuel Lopez 27-June-2012 Lethal Injection Estafana Holmes

33. Daniel Wayne Cook 8-August-2012 Lethal Injection Carlos Froyan Cruz-Ramos. Kevin Swaney

34. Richard Dale Stokley 5-December-2012 Lethal Injection Mary Snyder, Mandy Meyers

35. Edward Harold Schad 9-October-2013 Lethal Injection Lorimer Grove

36. Robert Glen Jones Jr. 23-October-2013 Lethal Injection Chip O'Dell, Tom Hardman, Maribeth Munn, Carol Noel, Judy Bell, Arthur 'Taco' Bell

State v. Jones, 197 Ariz. 290, 4 P.3d 345 (Ariz. 2000), Cert. denied 121 S. Ct. 1616 (2001). (Direct Appeal)

Procedural Posture

Appellant filed an appeal from the Superior Court of Pima County, Arizona, which convicted him inter alia of six counts of first-degree murder and sentenced him to death.

Overview

Appellant was convicted of six counts of first-degree murder, one count of first-degree attempted murder, three counts of aggravated assault, three counts of armed robbery, and two counts of first-degree burglary. He was sentenced to death. On direct appeal, the court affirmed. The court rejected appellant's contentions of prosecutorial misconduct. The prosecutor's single reference to the death penalty did not constitute reversible error. Appellant was not denied his right to be present at trial, because he was not excluded from any trial proceeding that involved any actual confrontation. Appellant failed to prove sufficient mitigating factors to justify a lesser sentence. Specifically, appellant did not prove the good character factor, because he committed crimes as a juvenile, and had been in and out of prison for felony convictions since that time.

Outcome

Death sentence was affirmed. Prosecutor's reference to the death penalty during closing argument was not reversible error. Appellant failed to prove sufficient mitigating factors to justify a lesser sentence.

En Banc - McGREGOR, Justice

P1 Appellant Robert Jones appeals his convictions and death sentences for six counts of first-degree murder, and his convictions and sentences for one count of first-degree attempted murder, three counts of aggravated assault, three counts of armed robbery, and two counts of first-degree burglary. 1 We review this case on direct, automatic appeal pursuant to article VI, section 5.3 of the Arizona Constitution, Arizona Rules of Criminal Procedure 26.15 and 31.2.b, and Arizona Revised Statutes Annotated (A.R.S.) section 13-4031. For the following reasons, we affirm the appellant's convictions and sentences.

I.

P2 David Nordstrom (David), the state's key witness, was released from prison in January 1996, after serving his sentence for a theft conviction. At that time, he took up residence in his father's home in Tucson, where he was under "home arrest" status and monitored by an ankle monitor. The home arrest was related to his prior theft conviction, and as a term of the arrest, he had to be inside his father's home by a certain time every evening. During this period of home arrest, he reestablished his friendship with the defendant, Robert Jones (Jones). Scott Nordstrom (Scott), David's brother, also returned to Tucson and spent time with David and Jones.

P3 Sometime before April 1996, David obtained a .380 semiautomatic pistol from a friend, which he gave to Jones after Jones requested it for protection. On May 30, 1996, Scott and Jones picked up David in Jones's truck, an old white Ford pickup. Jones was wearing his usual attire: a long-sleeved western shirt, Levi's, boots, sunglasses, and a black cowboy hat. In a parking lot near the Tucson Medical Center, Jones spotted a car that he thought he could steal. Although he failed to start the car, Jones found a 9mm pistol under the seat and left with it, stating, "I've got my gun now." (R.T. 6/23/98, at 103-04.)

P4 As the three continued driving, they began discussing the possibility of a robbery, and Jones gave Scott the .380 pistol. Jones then suggested that they rob the Moon Smoke Shop. He parked behind the store, telling David he and Scott would go in, rob it, and be right out. David then heard gunfire from inside, after which, Jones and Scott left the shop and jumped into the truck. David drove up the alley, exited onto the surface street, and headed toward the freeway. Jones stated, "I shot two people," and Scott stated, "I shot one." (Id. at 113.) Jones then split the money from the robbery with David and Scott.

P5 The survivors from the robbery testified that four employees were in the store at the time of the robbery: Noel Engles, Tom Hardman, Steve Vetter, and Mark Naiman, a new employee on the job for the first time. Just before the robbery, Engles was standing behind the counter, and Vetter and Naiman were kneeling behind it. Hardman was sitting behind another counter, and no customers were in the store. Jones and Scott followed a customer, Chip O'Dell, into the store and immediately shot him in the head. As the door buzzer indicated someone had entered the store, Engles, Vetter, and Naiman all heard the gunshot. Because all three were concentrating on the stock behind the counter, however, none of them saw the robbers or O'Dell enter. Engles looked up to see a robber in a long-sleeved shirt, dark sunglasses, and a dark cowboy hat wave a gun at him and yell to get down. Naiman recognized the gun as a 9mm.

P6 Engles noticed a second robber move toward the back room and heard someone shout, "Get the fuck out of there!" (R.T. 6/18/98, at 47.) Engles dropped to his knees and pushed an alarm button. The gunman at the counter nudged Naiman in the head with his pistol and demanded that he open the register. After he did so, the gunman reached over the counter and began firing at the others on the floor. Thinking the others were dead, Naiman ran out of the store and called 911 at a payphone. On the floor behind the counter, Engles heard shots from the back room and, realizing the gunmen had left the store, ran out the back door. While running up the alley to get help, he saw a light-colored pickup truck carrying two people, which turned sharply onto the surface street, despite heavy traffic. All survivors agreed that no one had offered any resistance to the gunmen, and that the shootings were completely unprovoked.

P7 Naiman and Engles survived, as did Vetter, despite the shots to his arm and face. Chip O'Dell died from a bullet through his head, which had been fired from close range. Hardman, who had fled to the back room when the gunmen entered, had been shot fatally in the head from above as he lay on the floor. Three 9mm shell casings were found in the store, one beside Mr. O'Dell and two near the cash register. Two .380 shells were found near Hardman's body. Two weeks after the robbery, Naiman met with a police sketch artist who used his description of one of the gunmen to create a composite drawing.

P8 Two weeks after the Moon Smoke Shop robbery, the Fire Fighters Union Hall was robbed. The Union Hall was a club owned by the firefighters and their guests, which contained a bar, bingo hall, and snack bar. Members entered using key cards, and the bartender buzzed in guests. When member Nathan Alicata arrived at 9:20 p.m., he discovered the bodies of member Maribeth Munn, the bartender, Carol Lynn Noel, and a couple, Judy and Arthur "Taco" Bell.

P9 During the ensuing investigation, the police found three 9mm shell casings, two live 9mm shells, and two .380 shell casings. Approximately $ 1300 had been taken from the open cash register. The coroner, who investigated the bodies at the scene, concluded that the bartender, Carol, had been shot twice, and that the other three victims were shot through the head at close range as their heads lay on the bar. Carol also suffered blunt force trauma which caused a bleeding laceration to the side of her mouth, and Arthur had a contusion on the right side of his head in a shape consistent with a pistol.

P10 David Nordstrom testified at trial that on the day of the Union Hall murders, his brother Scott gave him a ride home, where he remained the rest of the evening. David's parole officer produced records at trial verifying that David's ankle-monitoring unit indicated he had not left his father's home on the night of the murders. Late that evening, Jones entered David's father's house and began telling David what had happened. Jones admitted to David that he and Scott had robbed the Union Hall. He stated that because the bartender could not open the safe, Scott kicked her and shot her. Jones said he then shot the three other witnesses in the back of the head. Jones, Scott, and David disposed of the guns by throwing them into a pond south of Tucson, and Scott and David burned one of the victim's wallets at another location.

P11 David kept the secret until he saw an appeal on the television for information. At that time, he told his girlfriend, Toni Hurley, what he knew. Hurley eventually made an anonymous 88-CRIME call, which led to David's contact with the police, and an ultimate release of the information.

II.

P12 Jones appeals his convictions and sentences on eleven grounds. For the reasons discussed below, we uphold the convictions and sentences.

A.

P13 Jones's first point of error concerns the use of prior consistent statements to rebut recent charges of fabrication. Jones argues that in each instance, the witness's statement was actually made after that witness had motive to fabricate. Specifically, Jones objected to the following testimony: (1) David Nordstrom's out-of-court statements to Toni Hurley and the police, introduced at trial through Hurley's testimony, (2) David Evans's out-of-court statements to detectives, introduced at trial through Detective Edward Salgado's testimony, and (3) Lana Irwin's out-of-court statements to the police, introduced at trial by Detective Brenda Woolridge.

P14 Arizona Rule of Evidence 801(d)(1)(B) provides that an out-of-court statement is not hearsay if the declarant testifies at trial, is available for cross-examination, and the statement is "consistent with the declarant's testimony and is offered to rebut an express or implied charge against the declarant of recent fabrication or improper influence or motive." This rule requires the statement to have been made before the motive to fabricate arose: The only way to be certain that a prior consistent statement in fact controverts a charge of "recent fabrication or improper influence or motive" is to require that the statement be made at a time when the possibility that the statement was made for the express purpose of corroborating or bolstering other testimony is minimized. State v. Martin, 135 Ariz. 552, 554, 663 P.2d 236, 238 (1983). The timing requirement applies, regardless whether the witness is accused of recent fabrication, bad motive, or improper influence. See Id. Thus, to determine admissibility, the court must decide (1) whose credibility the statement bolsters, and (2) when that particular witness's motive to be untruthful arose. In this case, because both David Evans's and Lana Irwin's prior statements were used to bolster their own testimony and were made before their motives to fabricate arose, they were properly admitted under Rule 801. David Nordstrom made his prior statements, however, after his motive to fabricate arose. Therefore, the trial court erred in admitting them.

P15 First, Evans testified at trial that he had a conversation with Jones, in which Jones stated the police were on to him and knew that he had committed the murders. Evans also admitted he was receiving a plea bargain in two cases in exchange for his testimony. To rebut this motive to fabricate, the state questioned Detective Salgado concerning Evans's consistent statements to the police. Salgado testified that not only did Evans not ask for anything when he voluntarily contacted the police with the information, but that at the time of his original statements, he had not been arrested for any crime. During that original conversation with the police, Evans stated that Jones had admitted he needed to leave town because he had killed some people. Evans was not, however, offered a deal to testify until later. Thus, he had no motive to fabricate this original statement, and it was admissible under Rule 801. When the defense objected at trial, the trial court determined the prior consistent statements were admissible because they aided the jury in determining Evans's credibility. Because the defense called Evans's credibility into question through its cross-examination, the prior consistent statements were made before his motive to fabricate arose, and the statements were used to bolster Evans's credibility, the trial court did not abuse its discretion in admitting them.

P16 Second, Jones argues that the trial court improperly admitted Lana Irwin's prior consistent statements to the police, despite the fact that her motive to fabricate had already arisen at the time of her statement. Irwin testified at trial that she overheard Jones say he had murdered four people in Tucson. Because she feared Jones's retaliation, however, she originally told the detectives about a "dream" she had. In the dream, the victims were killed exactly as Jones had described it. To bolster Irwin's credibility, Detective Brenda Woolridge later testified that when she and another detective originally went to the Maricopa County Jail to question Irwin, they offered her absolutely no deal. In fact, Irwin initially refused to speak with them. It was only when they began to leave that Irwin stated she had the "dream." The defense objected to the detective's testimony concerning Irwin's "dream" as hearsay. The trial judge, however, admitted her statements to the police, relying on Rule 801. This admission was proper. Based on the evidence, Irwin did not have a motive to fabricate at the time of her original statements. She had been offered no deal prior to the statements, and the deal that she eventually received was negligible. 2 Because the statements were made by Irwin prior to her motive to fabricate and introduced to bolster Irwin's testimony, the trial court did not err in admitting them under Rule 801.

P17 Third, Jones claims that David Nordstrom's statements to both the police and Toni Hurley were erroneously admitted under Rule 801 because they were actually made after his motive to fabricate arose. At trial, the state offered Toni Hurley's testimony that David had made prior consistent statements to her concerning the murders for the purpose of bolstering David's testimony. The court admitted these statements under Rule 801. The defense's primary trial theory was that David actually perpetrated the murders, and because he happened to resemble Jones, decided to blame Jones as soon as they happened. Thus, when David told Hurley and the police what Jones had said and done, he was already plotting to lie about Jones's involvement in the case, even though David was not yet considered a suspect. Assuming Jones's theory was true, David's motive to fabricate necessarily arose at the time of the murders. See State v. Jeffers, 135 Ariz. 404, 424, 661 P.2d 1105, 1125 (1983). If David actually participated in all of the killings, his decision to shift the blame to Jones presumably formed immediately upon the deaths. It would have been in David's best interest to plant the seeds of this deception before he became a suspect, by telling Hurley and the police that Jones was the true murderer. Thus, because David's motive to fabricate arose at the time the murders occurred, rather than at the time of his arrest, the trial court improperly admitted his prior statements under Rule 801. We find, however, that admitting this testimony was harmless error.

P18 The defense's primary theory at trial was that David himself was the murderer and was merely blaming his bad deeds on the innocent defendant. To support this theory, the defense attacked David's credibility on every basis. It pointed out that David was a convicted felon, habitually used drugs and alcohol, violated the terms of his probation, did not obtain steady employment, possessed illegal firearms, violated his curfew, falsified his employment records, and lied to the police. On the stand, the defense impeached him numerous times with his prior inconsistent statements to the police. The defense argued that David was receiving virtually no punishment for his participation in the Moon Smoke Shop murders in exchange for his testimony. Finally, it argued in both opening and closing statements its theory that David was the true murderer. Yet, even in light of the defense's extensive attempts to impeach David and the multiple attacks on his veracity, the jury chose to convict Jones on every count of murder. We do not believe that had Toni Hurley's testimony concerning David Nordstrom's prior statements been excluded, the jury would have suddenly regarded David as a liar. David's credibility as a witness did not hinge on these prior consistent statements. Moreover, even if Hurley's testimony had been excluded, all of David's testimony about Jones's involvement and admissions would still have been admissible. Therefore, although the statements were erroneously admitted under Rule 801, we find no reversible error.

B.

P19 Jones next argues that the prosecutor's threat to prosecute defense witness Zachary Jones 3 (Zachary) for perjury, regardless of how Zachary testified, violated the defendant's right to a fair trial, due process right to present a defense, and compulsory process rights under U.S. Constitution Amendments V, VI, VIII, and XIV, and Arizona Constitution article II, sections 4 and 24, because it prevented the defense from rebutting the testimony of the prosecution's primary witness. According to a defense interview with Zachary, while David Nordstrom, the state's star witness, was in jail following his arrest for his participation in the murders, Zachary overheard David tell another inmate, "Yeah, there's someone out there who's almost my twin brother who I can lay all my bad deeds on, so I have a second chance at life." (R.O.A. at 323.) The defense made an offer of proof of Zachary's testimony at a pre-trial hearing on June 17, 1998. Defense counsel told the court that he had spoken with Zachary's attorney, who said Zachary might invoke the Fifth Amendment. As a result, defense counsel was not certain whether Zachary would testify. During this discussion, the prosecutor volunteered to the court why Zachary might invoke the Fifth Amendment:

[Prosecutor] I am putting this on the record so that the Court understands the context of why Mr. Zachary Jones may have a valid Fifth Amendment claim here. The Court has heard Mr. Larsen's [defense counsel] recitation of what Mr. Zachary Jones has previously said. It is the State's belief, and I believe we have a witness who will testify if need be, that there was a conspiracy in the Pima County Jail on the part of Mr. Robert Jones and other inmates to solicit inmates to fabricate accounts about David Nordstrom bragging that he had pulled the wool over the State's eyes and he had really been personally responsible for these killings. . . . . If he comes into court and says and sticks with the account that Mr. Larsen has given and I can prove that this is false, he is committing perjury. If he comes into court and says, and I think there is some possibility that, okay, you know, I didn't ever have this conversation with David Nordstrom, he is admitting to participating in a conspiracy to commit perjury because he will have to admit that he agreed with Robert Jones to falsify the story . . . . (R.T. 6/17/98, at 7-8.) The prosecutor neither contacted Zachary directly, nor spoke to Zachary's attorney. Instead, he explained to the court his analysis of the reasons Zachary might choose to invoke his Fifth Amendment rights. Six days into trial, when the defense attempted to call Zachary as a witness, Zachary's counsel informed the court that he might be liable for perjury, regardless of how he testified, and the prosecutor again confirmed the possibility in open court. Zachary consulted with his attorney and asserted his Fifth Amendment rights. These facts do not amount to prosecutorial misconduct.

P20 We will disturb the trial court's decision not to grant a mistrial for prosecutorial misconduct only for an abuse of discretion. See State v. Lee, 189 Ariz. 608, 616, 944 P.2d 1222, 1230 (1997). Jones cites to United States v. Vavages, 151 F.3d 1185 (9th Cir. 1998), for the proposition that a prosecutor's threat of a perjury prosecution to a defense witness constitutes witness intimidation and is improper. The facts of the present case, however, are distinguishable. In Vavages, the court agreed that "there . . . [was] no question that the prosecutor was justified in contacting . . . [the defense witness's] counsel, cautioning him against his client's testifying falsely, and informing him of the possible consequences of perjurious testimony." Id. at 1190. The court was concerned, however, with three aspects of the prosecutor's behavior: (1) his articulation to the witness of his belief that the testimony would be false, (2) his threat to withdraw the witness's plea agreement in an unrelated case, and (3) the use of the absence of the testimony to refute the defense's alibi during closing argument. See 151 F.3d at 1190-91; see also Webb v. Texas, 409 U.S. 95, 97-98, 93 S. Ct. 351, 353, 34 L. Ed. 2d 330 (1972) (finding that the judge's threatening remarks to the sole defense witness drove him off the stand).

P21 Here, however, the prosecution's statements did not constitute a threat. In fact, according to the record, as relied upon in Jones's own brief, the prosecutor's remarks were made to the court to explain Zachary's somewhat confusing decision to invoke the Fifth Amendment. Nothing in the record indicates that the prosecutor contacted Zachary directly, or made any personal threats to Zachary concerning his testimony. Nor did the prosecutor ever actually say that he would pursue a conviction, regardless of how Zachary testified. He simply stated his understanding of the reasons Zachary might refuse to testify. There is no per se prosecutorial misconduct when the prosecutor merely informs the witness of the possible effects of his testimony. See State v. Dumaine, 162 Ariz. 392, 400, 783 P.2d 1184, 1192 (1989). In addition, counsel represented Zachary and advised him as to whether he should testify. Thus, Zachary's decision followed consultation with and advice from his own attorney. Absent some substantial governmental action preventing the witness from testifying, a witness's decision to invoke the Fifth Amendment does not suggest prosecutorial misconduct.

P22 Finally, Jones argues that the trial court erred by failing to sua sponte grant immunity to Zachary in exchange for his testimony. Jones failed, however, to make any objection or motion to this effect at trial. No court has held that the constitutional burden to meet the Sixth Amendment's Confrontation Clause shifts to the trial court in the absence of the defense counsel's motion or request to grant such immunity. At the very least, Jones waived the argument that the court should have granted him immunity by failing to pursue the remedy at trial. For these reasons, we reject the defendant's second point of error.

C.

P23 Jones's third point of error concerns the life- and death-qualification of the jury. Jones argues that once the trial court denied his motion to prohibit death-qualification, the only standard that could be applied was that defined in Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510, 88 S. Ct. 1770, 20 L. Ed. 2d 776 (1968). He further argues that when the court allowed the prosecution the opportunity to death-qualify, the defendant should have been entitled to life-qualify under Morgan v. Illinois, 504 U.S. 719, 112 S. Ct. 2222, 119 L. Ed. 2d 492 (1992). Although the court denied the defendant's request to apply Witherspoon and Morgan on improper grounds, the court effectively met the constraints of both tests during its voir dire questioning. Therefore, the trial court's denial constituted harmless error.

P24 We have recognized that death-qualification is appropriate in Arizona, even though juries do not sentence: "We have previously rejected the argument that, because the judge determines the defendant's sentence, the jury should not be death qualified. We have also repeatedly reaffirmed our agreement with Witherspoon v. Illinois and Adams v. Texas." State v. Van Adams, 194 Ariz. 408, 417, 984 P.2d 16, 25 (1999) (citations omitted). Even more importantly, however, this Court has applied and adopted the more liberal Wainwright v. Witt, 469 U.S. 412, 105 S. Ct. 844 (1955), test. See State v. Anderson, Ariz. Adv. Rep. , Ariz. , P.2d (2000). In Wainwright, the Supreme Court took a step back from the rigid test articulated in Witherspoon, which required the prospective juror to unequivocally state that he could not set aside his feelings on the death penalty and impose a verdict based only on the facts and the law, and held that a juror was properly excused from service if the juror's views would "'prevent or substantially impair the performance of his duties as a juror in accordance with his instructions and his oath.'" Wainwright, 469 U.S. at 424, 105 S. Ct. at 852 (quoting Adams v. Texas, 448 U.S. 38, 45, 100 S. Ct. 2521, 2526, 65 L. Ed. 2d 581 (1980)). The trial judge has the power to decide whether a venire person's views would actually impair his ability to apply the law. For this reason, "deference must be paid to the trial judge who sees and hears the juror." Wainwright, 469 U.S. at 426, 105 S. Ct. at 853. Thus, we recognize that the trial judge has discretion in applying the test; the inquiry itself is more important than the rigid application of any particular language.

P25 Although the trial judge incorrectly stated that the Witherspoon/Wainwright standard did not apply because Arizona juries do not sentence defendants, in fact his approach complied with the constraints of Witherspoon/Wainwright. The trial court, in agreement with both parties, submitted written juror questionnaires at the outset of voir dire. These questionnaires were available to the parties after the venire persons completed them. The parties then conferred about which persons to strike based on the answers given. The questionnaire contained the following question:

If Robert Jones is convicted of one or more counts of first degree murder in this case, it is a legal possibility that he could receive a sentence of death. In Arizona, a jury only decides the question of whether the defendant is guilty or not guilty; the jury does not decide the sentence to be imposed, nor does it make any recommendation to the court on the sentence to be imposed. The matter of the possible punishment is left solely to the court. Therefore, if you serve as a juror in this case, you will be required under your oath to disregard the possible punishment and not to let it affect in any way your decision as to guilty [sic] or innocence. Can you disregard the possible punishment and decide this case based on the evidence produced in court? (Emphasis in original.) Defense counsel stated only that "without waiving my request for my version of a questionnaire," he agreed to the proposed process. (R.T. 5/4/98, at 9.) He did not object to the trial court's particular question before the questionnaires were submitted. After the questionnaires were filled out and analyzed by the parties, the lawyers agreed to dismiss thirty jurors for cause because those persons had indicated that they could not set aside their beliefs about the death penalty or their opinions already formed from media coverage. The defense did not object to the dismissals, nor request to further question any of the dismissed venire persons. The court then informed the attorneys that they should call attention to any additional questions that should be asked concerning the death penalty. The court dismissed another juror for cause because that juror stated he could not set aside his feelings on the death penalty. No other potential juror expressed this view. The defense then asked that the trial court pose additional specific questions concerning the death penalty. The court declined, stating that the questionnaires adequately addressed the issue, but agreed to inquire further whether any of the remaining jurors felt strongly about the death penalty, one way or the other. The judge reminded the jurors of the questionnaire, and asked them if they felt strongly about the death penalty. Three persons responded that they supported its imposition. Once again, defense counsel failed to object or request additional questions (although he did later strike these jurors with his peremptory strikes). Both parties passed the panel with no further objections.

P26 In light of these facts, the trial court did not abuse its discretion. Not only did it ask the appropriate Witherspoon/Wainwright question in the questionnaire and to the remaining panel, but the defense counsel failed to object at any time to the questions. Thus, the court's procedure met the Witherspoon/Wainwright test.

P27 Likewise, although the trial court did not specifically apply Morgan v. Illinois, 4 504 U.S. 719, 112 S. Ct. 2222, 119 L. Ed. 2d 492 (1992), it also satisfied the constraints of this test through voir dire. Jones essentially argues that the trial court should have applied a reverse-Witherspoon test under Morgan. In Morgan, the Supreme Court held that a jury pool containing prejudiced jurors, be it toward one extreme or another, could not effectively pass judgment in a capital case. In Witherspoon, the Court was concerned that a juror who felt so strongly against the death penalty that he could not set aside his belief and follow the evidence and the law could not make an unbiased determination concerning the sentence. Morgan recognizes the opposite extreme: defendants have a right to know whether a potential juror will automatically impose the death penalty once guilt is found, regardless of the law. Thus, defendants are entitled to address this issue during voir dire.

P28 Morgan, however, does not require the trial court to life-qualify the jury in the absence of the defendant's request. See United States v. McVeigh, 153 F.3d 1166, 1206 (10th Cir. 1998) ("upon a defendant's request, a trial court is obligated to ensure that prospective jurors are asked sufficient questions"); United States v. Tipton, 90 F.3d 861, 879 (4th Cir. 1996) ("The right to any inquiry on this subject is dependent upon request . . . ."). The trial court is under no obligation to question the venire persons endlessly concerning other topics, even if those questions might indicate an affinity for the death penalty. See Trevino v. Johnson, 168 F.3d 173, 183 (5th Cir. 1999).

P29 Here, the defense counsel never submitted questions to the trial court articulating the Morgan question. During voir dire, the court specifically asked if any of the jurors had strong feelings about the death penalty, either way. Three people responded that they favored its application, and all three were removed by the defense with its peremptory strikes. The defense did not object to the failure to remove for cause, and failed to request any additional questions. Although the trial judge did not rigidly apply Morgan, he sought and obtained the required information from the panel. For these reasons, we reject Jones's third point of error.

D.

P30 Jones next argues that the trial court abused its discretion by allowing David Nordstrom to testify (1) about Jones's status as a paroled felon, (2) that following the murders, Jones borrowed duct tape to use in a subsequent robbery, and (3) that Jones was subsequently incarcerated in Phoenix. Jones argues that danger of unfair prejudice outweighed the probative value of these statements.

P31 First, through unsolicited testimony, David Nordstrom mentioned on the stand that after Jones dyed his hair brown, he asked David for a roll of duct tape for use in another robbery. Shortly thereafter, when asked why he refused to return Jones's telephone calls, David responded that he knew Jones was in jail and had no desire to call him there. After David made several similar statements, the defense moved for a mistrial.

P32 When unsolicited prejudicial testimony has been admitted, the trial court must decide whether the remarks call attention to information that the jurors would not be justified in considering for their verdict, and whether the jurors in a particular case were influenced by the remarks. See State v. Stuard, 176 Ariz. 589, 601, 863 P.2d 881, 893 (1993). When the witness unexpectedly volunteers information, the trial court must decide whether a remedy short of mistrial will cure the error. See State v. Adamson, 136 Ariz. 250, 262, 665 P.2d 972, 984 (1983). Absent an abuse of discretion, we will not overturn the trial court's denial of a motion for mistrial. See Id. The trial judge's discretion is broad, see State v. Bailey, 160 Ariz. 277, 279, 772 P.2d 1130, 1132 (1989), because he is in the best position to determine whether the evidence will actually affect the outcome of the trial. See State v. Koch, 138 Ariz. 99, 101, 673 P.2d 297, 299 (1983). In this case, the comments did not create undue prejudice, and the trial court did not abuse its discretion.

P33 Defense counsel did not request any curative instruction, because he felt it would only draw attention to the remarks. The court refused to grant the motion for mistrial, finding that David did not testify that a robbery actually occurred, and that the jury probably would assume Jones was in jail for the immediate crimes. Furthermore, the prosecutor avowed that the remarks were both unexpected and unsolicited. The prosecutor informed the court that David had been fully instructed about the areas he was not permitted to discuss under the in limine rulings. For these reasons, the trial court concluded that a limiting instruction would cure any prejudice. The jury was instructed:

Ladies and gentlemen, references have been made in the testimony as to other alleged criminal acts by the defendant unrelated to the charges against him in this trial. You are reminded that the defendant is not on trial for any such acts, if in fact they occurred. You must disregard this testimony and you must not use it as proof that the defendant is of bad character and therefore likely to have committed the crimes with which he is charged. (R.T. 6/23/98, at 143-44.) During redirect, David responded to a question with the statement that his brother Scott and Jones were both convicted felons. Only when the counsel later approached the bench to consider questions submitted by the jury, however, did the defense renew its motion for a mistrial. Once again, the trial court determined that the error could be cured through a limiting instruction, and repeated the instruction set out above. 5

P34 Arizona has long recognized that testimony about prior bad acts does not necessarily provide grounds for reversal. See, e.g., State v. Stuard, 176 Ariz. 589, 601-02, 863 P.2d 881, 893-94 (1993) (holding that a trial judge's limiting instruction and striking of the offending statements cured the defects); State v. Bailey, 160 Ariz. 277, 279-80, 772 P.2d 1130, 1132-33 (1989) (holding that a remark that the defendant had been in jail did not require a mistrial because "even if the members of the jury reached that conclusion, they would have no idea how much time he spent in prison or for what crime"). Here, the testimony made relatively vague references to other unproven crimes and incarcerations. Furthermore, the judge gave an appropriate limiting instruction, without drawing additional attention to the evidence.

P35 Second, unlike the primary case on which Jones relies, Dickson v. Sullivan, 849 F.2d 403 (9th Cir. 1988), in which a court official told jurors of the defendant's previous involvement in a similar case, the statements here were unsolicited descriptions from a witness concerning a dissimilar crime. When the statements are made by a witness, whose credibility is already at issue, they do not carry the same weight or effect as a statement from a court official, who is presumed to uphold the law. The defendant agreed during trial that the prosecution played no part in soliciting the information from David. Therefore, the statements are not as harmful as those made in Dickson, and the trial court did not abuse its discretion.

E.

P36 Jones's fifth point of error concerns statements the prosecution made during closing arguments. During the arguments, the prosecutor made reference to the death penalty, compared Jones to Ted Bundy and John Wayne Gacy, and asked the jury to return a guilty verdict on behalf of the victims and their families. The defense moved for a mistrial, and its motion was denied. Although we agree that some of the prosecutor's statements were inappropriate, for the following reasons, we uphold the trial court's decision.