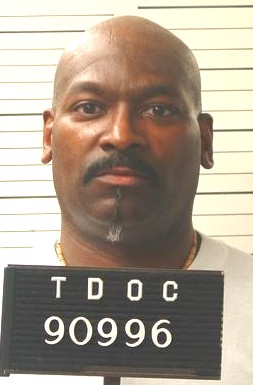

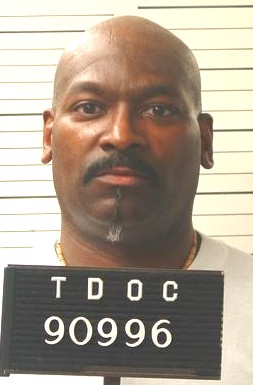

49th murderer executed in U.S. in 2009

1185th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

2nd murderer executed in Tennesee in 2009

6th murderer executed in Tennesee since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(49) |

Injection |

Cecil C. Johnson Jr. B / M / 23 - 53 |

Bobbie Bell B / M / 12 James E. Moore B / M / 41 Charles House B / M / 35 |

|||||||

Citations:

State v. Johnson, 632 S.W.2d 542 (Tenn. 1982) (Direct Appeal).

Johnson v. State, 797 S.W.2d 578 (Tenn. 1990) (Postconviction Relief).

Johnson v. Bell, 525 F.3d 466 (6th Cir. 2008) (Habeas).

Final / Special Meal:

Refused.

Final Words:

Johnson mouthed “I love you,’’ repeatedly to his family, then said "You all stay strong, and keep trusting in the Lord."

Internet Sources:

"Tennessee executes Cecil Johnson," by Chris Echegaray. (December 2, 2009)

In the end Cecil Johnson Jr., convicted in the fatal shooting of three people – including a 12-year-old boy — in 1981, was only forgiven by his son who is in prison. Johnson, sentenced to death, was pronounced dead at 1:34 a.m. Wednesday after he mouthed “I love you,’’ repeatedly to his family.

In 1980 Johnson shot the 12-year-old boy in the head and killed two other people after robbing a convenience store on 12th Avenue South in Nashville. The family of the victims declined to say anything publicly following the execution.

Johnson's brother David Johnson spoke to the media, saying, "He's in a better place because he gave his life to the Lord." During the execution a daughter, DeAngela Johnson, was described as turning her back and covering her ears against her father's breathing sounds as the injections began.

Johnson, 53, was forgiven by his 29-year-old son serving prison time in West Tennessee. James Johnson, serving 23 years for aggravated assault and aggravated robbery, sent his father a message with Riverbend Maximum Security Prison warden Ricky Bell. “Tell him I love him and forgive him for not being there,’’ Johnson’s son said in the message. “And tell him he is not the reason why I am in prison.”

Johnson, the sixth person in the state to be executed since 1960, was pronounced dead after a lethal injection was given at 1 a.m. Wednesday morning.

Johnson, then 24, was convicted of three counts of first-degree murder for the deaths of Bobby Bell Jr., James Moore and Charles House. While in prison in 1985, Johnson and an inmate were involved in a fight that led to the death of another inmate. Johnson was charged with voluntary manslaughter.

Still, last ditch efforts for clemency and motions to stop the execution failed. Tuesday night the Tennessee Supreme Court had denied a request for a stay of execution that was filed by the Reconciliation Ministries.

Johnson refused a final meal, said Dorinda Carter, spokeswoman for the Tennessee Department of Correction. He met with his spiritual adviser, Rev. James Thomas, of the Jefferson Street Missionary Baptist Church. Meanwhile, a service was held in opposition to the death penalty at Hobson United Methodist Church in East Nashville, where 60 people gathered.

Suzanne Craig Robertson had visited with Johnson for 17 years, including his last day on Tuesday. She choked back tears, telling the audience that he was fine and hopeful. “He really believes something is going to stop this,’’ she said from the podium. She declined an interview but Robertson has written about her visits with Johnson in the Tennessee Bar Journal, where she’s the editor. The Journal is the monthly publication for the Tennessee Bar Association.

Robertson wrote that “Cecil is very much like many others on death row: he had an abusive, impoverished childhood, he is black, was largely uneducated until he got in prison, and he is indigent. He is nothing like the others to me, though, because I know his face and his laugh. And his daughter. You’d be surprised how that makes a difference.”

Johnson was born August 29, 1956, in Maury County. He had dropped out in the ninth grade before getting his GED in prison in 1987. He was the oldest of 10 children. At 21, Johnson was married and had a child. He worked at Vanderbilt University as dishwasher and cook at the time of his arrest.

What could’ve made a difference in Johnson’s case are some questions surrounding his conviction, said Denver Schimming, an organizer for Tennesseans for the Alternative to the Death Penalty, formerly known as Tennessee Coalition to Abolish State Killing.

Questions were raised after the trial concluded about police reports that were never turned over to Johnson's attorneys that cast doubt on some eyewitness testimony. His attorneys questioned whether a prosecutor coerced Johnson's friend into lying about that night. “I can’t speak on Johnson’s guilt or innocence,” Schimming said as he prepared protest signs. “But the process of convicting him was fraught with problems. There was no weapon found, no physical evidence and no proceeds of the robbery found.

“There has to be an alternate method to executions – life without parole,” he added. Many states are reviewing their death penalty laws with some repealing it and others enacting stricter guidelines, said Stacy Rector, director of Tennesseans for the Alternative to the Death Penalty. “Change may come slowly for us,” she said at the church service. But there is reason for hope.”

Before his death, Nashville’s federal court granted a temporary restraining order stopping Johnson’s autopsy, pending further review by the court. A hearing was set for 1 p.m. Thursday, Dec. 10. Johnson claimed an autopsy after the execution would be against his religious beliefs and “would amount to desecration.”

"Tennessee executes man who killed three," by Erik Schelzig. (December 3, 2009 at midnight)

NASHVILLE - An inmate put to death for a triple slaying got words of forgiveness from his son, a fellow prisoner, a few hours before the early Wednesday execution. Cecil C. Johnson Jr. received the message from son James Johnson before being executed at Riverbend Maximum Security Institution for the three 1980 deaths in Nashville.

The younger Johnson, 29, is serving time at the West Tennessee State Penitentiary for aggravated assault and burglary. "He said he loves him and forgives him for not being there for him as a father, and that it's not Cecil's fault that he ended up in prison himself," said Dorinda Carter, spokeswoman for the Tennessee Department of Correction.

Cecil Johnson, 53, was executed early Wednesday for killing three people while robbing a Nashville convenience store. The victims included the market owner's 12-year-old son, Bobby Bell Jr., and two men sitting in a cab outside, Charles House, 35, and driver James Moore, 41. The boy's father witnessed the killing and was wounded.

Thirteen minutes after the lethal injection began, Cecil Johnson was officially declared dead at 1:34 a.m.

Bob Bell Sr. and Moore's brother witnessed the execution in a separate room from Johnson's family, Carter said. They did not speak to the media after the execution.

When the blinds to the execution room were lifted, Johnson lay strapped to a gurney with medical tubes strapped to his skin. He mouthed "I love you" to his wife, two brothers and daughter, and was asked whether he had any final words. "You all stay strong, and keep trusting in the Lord," he said.

After the warden said "proceed," daughter Deangala Johnson, 30, turned away and covered her ears as her father took two deep breaths, fell asleep and began to snore. She tried to leave the witness room, but was told by a guard that she couldn't until the warden announced the time of death.

After the execution, wife Sarah Johnson said: "You didn't put away an evil man, you put away a holy man." "Cecil didn't want anyone to have pity," said brother David Johnson. "He already gave himself to the Lord."

A few dozen anti-death penalty protesters gathered in a field outside the prison. "If we're not here, who is going to know that there are people who don't want this to happen?" said Monica Scarlett, 50, a graduate student in social work.

The execution came after federal courts, including the Supreme Court, denied a series of last-minute legal efforts to halt the execution. Gov. Phil Bredesen denied clemency for Johnson last week.

Johnson was a 23-year-old kitchen worker at Vanderbilt Hospital when the July 5, 1980, slayings occurred. His father turned him in two days after the shooting, and he was identified at trial by Bob Bell Sr.

In 1987, Johnson was one of two death row inmates convicted in the 1985 beating death of fellow prisoner Laron Williams at the old Tennessee Penitentiary. Williams was on death row for the slayings of a Memphis policeman and a Roman Catholic priest.

Johnson became the sixth person put to death in Tennessee since 2000. There were no executions between 1961 and 1999. The last person executed in Tennessee was Steve Henley in February.

"Justices spar over Tennessee execution," by Bill Mears. (December 2, 2009 2:24 p.m. EST)

WASHINGTON (CNN) -- Two Supreme Court justices engaged in a late-night exchange of harsh words before the execution early Wednesday of a convicted Tennessee killer who had been sitting on death row for nearly three decades.

Justices John Paul Stevens and Clarence Thomas disagreed over whether to grant a stay of execution for Cecil Johnson Jr. The stay eventually was denied, and about an hour later, at 2:34 a.m., Johnson was put to death by lethal injection at a Nashville, Tennessee, prison.

The 53-year-old inmate had been convicted of murder in a 1980 shooting spree at a convenience store near the state capital. The victims included 12-year-old Bobby Bell Jr., son of the store owner, who was wounded. Two other men sitting in a nearby taxicab also were shot to death.

Stevens, who was initially presented the last-minute appeal by Johnson's lawyers, would have granted the stay, along with Justice Stephen Breyer. Stevens was concerned that too much time had elapsed between sentencing and the planned execution, amounting perhaps to cruel and unusual punishment. "Johnson bears little, if any, responsibility for this delay," said Stevens, who said procedural hurdles at the appellate stage for capital defendants created what he called "underlying evils of intolerable delay." "The delay itself subjects death row inmates to decades of especially severe, dehumanizing conditions of confinement."

It is an issue that the 89-year-old justice has long urged his colleagues to address, with little success. In his early years on the high court in the mid-1970s he had supported the resumption of the death penalty after a four-year moratorium imposed by the Supreme Court. But in recent years, he has voiced his opposition to capital punishment, particularly in cases involving inmates asserting their right to challenge their sentences.

Thomas reacted strongly to Stevens' statement. The conservative jurist said the inmate had challenged his conviction and sentence for nearly 29 years and "now contends that the very proceedings he used to contest his sentence should prohibit the state from carrying it out." "In Justice Stevens' view, it seems the state can never get the timing just right. The reason, he has said, is that the death penalty itself is wrong." Thomas said. "As long as our system affords capital defendants the procedural safeguards this court has long endorsed, defendants who avail themselves of these procedures will face the delays Justice Stevens laments."

Then Thomas goes on to say there are "alternatives," citing the custom in England centuries ago to carry out an execution the day after a conviction. "I have no doubt that such a system would avoid the diminishing justification problem Justice Stevens identifies, but I am equally confident it would find little support from this court."

The high court had been presented with Johnson's emergency appeal early Tuesday afternoon, but apparently the time needed to produce the Stevens and Thomas statements delayed the high court from issuing its denial of a stay until 1:38 a.m. Wednesday. The execution was carried out as scheduled, with no problems reported by corrections officials.

"Cecil C. Johnson Jr execution," by Kate Howard, The Tennessean. (Updated: 12/1/2009 5:57:48 PM)

A flurry of filings in the Cecil Johnson death penalty case appears unlikely to delay or halt the convicted killer's execution. Johnson is scheduled to die at 1 a.m. central time Tuesday morning.

Defense attorneys filed an emergency appeal for stay of execution, along with a supporting memorandum. The motion for a stay calls for a consideration of procedural matters, over whether Johnson's subsequent appeal is a second appeal on habeas corpus grounds. Prosecutors fought against the stay, and the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit has chosen not to issue a stay of execution.

Bobby Bell Jr. was crying hard as he filled a sack with money and gave it to the gunman. He and his father, Bob Bell Sr., were inseparable, and on that hot Saturday night in July 1980 the boy was working the register at his father's store. The 12-year-old sold Cokes and snacks while the elder Bell and his friend worked on a motor. They were about to close for the night when a man burst in with a six-shot revolver.

Although he did everything the robber told him to do, Bobby was shot point-blank in the head in front of his father. The friend, Louis Smith, jumped on top of the boy without knowing it was too late. Bell Sr. was shot in the wrist when he raised his arms to shield his head. Two men sitting in a taxi outside were shot dead as the robber fled.

Prosecutors theorize that the killer, Cecil C. Johnson Jr., then 23, planned to rob the convenience store on 12th Avenue South and leave no witnesses. Johnson was given three death sentences for the murders and two life sentences for the two victims who survived.

In the early morning hours on Wednesday, Johnson is scheduled to die by injection with a three-drug cocktail at Riverbend Maximum Security Prison. Barring any last-minute reprieve, Johnson will be the first person from Nashville executed since the death penalty was reinstated in 1977.

Questions were raised after the trial concluded about police reports that were never turned over to Johnson's attorneys that cast doubt on some eyewitness testimony. His attorneys questioned whether a prosecutor coerced Johnson's friend into lying about that night. The friend, Victor Davis, planned to testify about Johnson's alibi but later became a state informant. In the end, each of Johnson's arguments was rejected by the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. The Tennessee Supreme Court set his execution date.

Gov. Phil Bredesen has denied Johnson's request for clemency, and a request to stay the execution with the U.S. District Court was denied Monday. "It was a case that captured people's imaginations," said Torry Johnson, Nashville district attorney general, who was a prosecutor on the case. "Certainly, we had robberies before this, and market owners and clerks were killed. But having a child killed was something that really did make this different. It was shocking to people."

Johnson, who has maintained his innocence, and his attorney, Jim Thomas, have declined interview requests.

In an interview with the Nashville Banner three weeks after his arrest in 1980, Johnson said he felt like he was stuck in a bad dream. He said he met with police after hearing they were looking for him and told them he was in Franklin with friends at the time of the slayings. He told the paper that he and Victor Davis were just driving around on a pretty summer day, looking for women and dice games, not for the massacre that happened a few blocks from his dad's home.

He was surprised when he was arrested and denied bond. "I feel like this whole thing is wrong," he said. But the witnesses said otherwise.

First robbery at market

The building where Bob Bell's Market was located is now a bar in a district bustling with shops and trendy restaurants. In 1980, what's now the 12South neighborhood was mostly houses, straddling the Edgehill and Belmont neighborhoods. Bell had owned the market for eight years and had never been robbed.

When the man walked into the market with a gun in his hand, Louis Smith didn't realize the gravity. He said he thought the man and Bell were "just jiving," until he was ordered behind the counter.

Minutes later the shooting started. "I jumped on the child," Smith testified. "I didn't think he'd been shot yet."

But a bullet had struck little Bobby in the head. Smith was shot, too. As the man pointed the gun at the head of Bell Sr., he threw his arm up in defense. His wrist stopped the bullet. "Did anyone do anything to provoke the shooting that you know of?" then-prosecutor Tom Shriver asked Smith on the stand. "No. Bob begged him to try to keep him from it," Smith said.

On his way out the door, the man fired two shots, and prosecutors theorized they were the last two bullets in a six-shot revolver. James Moore, a Nashville native and Army veteran who had just started driving for Supreme Cab, was behind the wheel of the taxi. Moore and passenger Charles House died inside the cab.

Bell counted quickly to 10 and jumped up to get his shotgun at the back of the store. He tried to chase the man out, hearing the shots that were fired into the cab as he ran. He told a reporter later that he couldn't have fired the gun anyway, with the bullet in his arm. He stood helpless outside.

Bell said he knew Johnson as a customer in the store who sometimes wore clothing from Vanderbilt. Bell didn't know his name but said he knew the face. "I think (Bell) has made a mistake that he doesn't want to back off of," Johnson told reporters shortly after his arrest. "He looked straight at me and said, it was me. Everything inside me fell down... I don't think he was lying. I just think he made a mistake."

Attempts to reach Bell and relatives of House by phone, mail and through the attorney general's victims services program were failed. On Monday, Bell was the only person signed up to witness the execution by lethal injection.

After Johnson was convicted, his attorneys asked the jury to consider his youth and lack of serious criminal history before sentencing him to death.

Johnson testified at his trial that he was never at the market. But Bell, Smith and two other witnesses identified him as the shooter. There was no physical evidence linking him to the scene, and the murder weapon was never found. But four witnesses testified that Johnson was the killer - one of whom was planning to be his alibi witness, until he was arrested himself a week before trial.

The next day, after an interrogation by the district attorney's office and a promise of immunity, Victor Davis was a witness for the state. He testified that he dropped Johnson off at a car wash just before 10 p.m. when the murders happened. Johnson told him he was going in to rob Bob Bell, and said he didn't intend to leave any witnesses. He said he sat with him later at Johnson's father's house as they counted the money, and Johnson gave him $40.

The district attorney who led the interrogation, Sterling Gray, was later ap-pointed to a judgeship and indicted on charges that he took bribes from defendants in exchange for light sentences. Gray killed his wife and himself that same year. Jim Sledge, an investigator with the district attorney's office who worked on the case, said Gray himself was not the only person involved in that interview. He and the other prosecutors were there, too, he said, and it was above board.

Johnson's attorneys raised the flipped witness as well as questions about the eyewitness testimony in their appeals. Several police reports saying that Bell's friend Louis Smith never got a good look at the accuser were withheld from the defense attorneys, and it wasn't until 1992 that attorneys for Johnson learned of their existence. The district attorneys admitted that the reports were withheld and that the information could have aided Johnson in his defense.

But the federal appeals court ruled the mistake didn't affect the outcome of the trial. Smith admitted that he identified Johnson after seeing him on television, already arrested in the murders, but denied that was the reason he picked him. A panel of federal appeals judges ruled 2-1 to deny Johnson's appeal. In a scathing dissent, Judge R. Guy Cole, Jr. wrote that the jury "saw a markedly different trial than it would have" if the prosecutors hadn't withheld the reports. "Because 'fairness' cannot be stretched to the point of calling this a fair trial, I dissent," Cole wrote.

28 years since the trial

Now 28 years since that trial, gray has crept into the 53-year-old inmate's beard. He was convicted along with Tony Bobo of voluntary manslaughter in prison for the killing of fellow Death Row inmate Laron Williams in 1985. Since then, the cook for Riverbend's Death Row inmates has lived a quieter existence. He hasn't even been written up for talking back in at least seven years.

James Moore's sister, Betty Hunter, has mixed feelings about the execution. Her family, scattered across the country for decades, had no idea a date was set. Learning about it opened a very painful old wound. She said her brother was an intelligent man who played classical piano and had a young daughter. "Even though you never forget, you can kind of move on," Hunter said. "You try not to insist on the how and the why, and time has a way of healing all those wounds to some degree. Don't forget, but you do kind of move on."

Moore was the valedictorian of his high school class and studied physics at Tennessee State University, and his family says he grasped concepts so easily that be barely had to study to make the grades they had to work so hard for. But the man known as "Pretty Mo" was more concerned with enjoying each day, surrounded by friends and loved ones, than keeping his nose in the books. "My family has lost the presence of my brother," Hunter said. "If the courts have decided based on the information they received that he's guilty, at least he's lived 29 years longer than my brother. My brother's life was taken for no reason."

On Monday, Johnson's attorneys argued before a federal court judge that he should get a stay of execution based on the nearly three decades the case has stretched on. They said it amounted to a violation of his civil rights that he was confined in uncertainty for so long. Johnson, his attorney Thomas argued, had done everything he could to move the case along, expecting he'd get a new trial somewhere along the way; the delays were caused by the state.

U.S. District Court Judge Robert Echols dismissed the case, but he did agree that cases like Johnson's, when condemned prisoners stretch on for decades, tend to undermine the public's confidence in the system. "As a member of the judiciary, I am somewhat embarrassed that our system has not been more efficient and more effective," Echols said.

On July 5, 1980, Bob Bell’s Market on 12th Avenue South in Nashville, Tennessee was robbed by an armed gunman around 9:45 pm. In the store at the time of the robbery were Bob Bell, Jr., his son Bobbie, and Louis Smith, an acquaintance of Bob’s.

Bobbie Bell was helping at the cash register and Smith was working at the store repairing a boat motor for Bob Bell. Cecil Johnson pointed a gun at Bell and ordered him and Smith behind the register where Bobbie Bell stood. While Johnson and his captives were behind the counter, a woman and two children entered the market. Johnson concealed his gun and told his captives to act naturally and to wait on the customers. As soon as the customers left, Johnson ordered Bobbie Bell to fill a bag with money from the cash register; Bobbie obeyed. Johnson then searched Smith and Bell, taking Smith’s billfold.

At that moment, Charles House stepped into the market, and was ordered out by Johnson; House obeyed. Almost immediately thereafter, Johnson began shooting his captives. Bobbie Bell was shot first and killed. Smith threw himself on top of Bobbie to protect him from further harm, and was himself shot in the throat and hand. Johnson then walked toward Bob Bell, who was on the floor behind the counter, pointed the gun at Bell’s head and pulled the trigger. Fortunately, Bell threw up his hands and the bullet hit him in the wrist, breaking it. Johnson ran from the market.

Bell got a shotgun from under the store counter, ready to chase Johnson, then heard two gunshots outside the market. He looked toward the front of the store and saw Johnson standing beside an automobile parked at the entrance. Bell chased after Johnson. As he passed the automobile, he saw that a cab driver and his passenger had been shot. The passenger was later identified as Charles House, the customer who had entered the market only moments before Johnson began shooting his captives and who was acquainted with Johnson. Both the cab driver, James E. Moore, and Charles House died from a gunshot wound.

Information Bell gave to police officers immediately after the robbery led to Johnson’s arrest on July 6, 1980. At trial, both Bell and Louis Smith identified Johnson as the perpetrator of the crimes. In addition, Debra Smith, the customer who entered the market during the commission of the robbery, identified Johnson as having been behind the counter with Bell, Bobbie Bell, and Louis Smith. Johnson was also connected to the crimes by Victor Davis, a friend who had spent most of July 5, 1980, in the company of Johnson.

During the course of the investigation, Davis made statements to the prosecution and defense that provided Johnson with an alibi. In essence, Davis said that he and Johnson were together continuously from roughly 3:30 p.m. on July 5 until approximately midnight and that at no time did they visit Bell’s Market. However, the week before the trial, and after he was arrested on unrelated charges of carrying a deadly weapon and public drunkeness, Davis made a statement to the prosecution incriminating Johnson.

At trial, Davis, who was promised immunity from prosecution for any involvement in the crimes committed at Bell’s Market, confirmed his statements incriminating Johnson. According to Davis’s testimony, he and Johnson left Franklin, Tennessee, at approximately 9:25 p.m. on July 5 and arrived in Nashville in the vicinity of Bell’s Market shortly before 10:00 p.m. Johnson then left Davis’s automobile after stating that he was going to rob Bell and was going to “try not to leave any witnesses.” Davis testified that he next saw Johnson some five minutes later near Johnson’s father’s house, which was roughly a block from Bell’s Market. Davis stated that Johnson was carrying a sack and pistol and, when he entered Davis’s automobile, Johnson said, “I didn’t mean to shoot that boy.”

Johnson discarded the gun, which Davis later retrieved and sold the following day for $40. Davis further testified that after he picked up Johnson, they drove directly to Johnson’s father’s house, arriving shortly after 10:00 p.m. There, in the presence of Johnson’s father, Johnson took money from the sack, counted approximately $200, and gave $40 of this money to Davis. According to Davis, Johnson told his father that he and Davis had been gambling and that gambling was the source of the money.

Johnson testified on his own behalf and denied being in Bell’s Market on July 5, 1980. His testimony as to the events of the day was largely in accord with that of Victor Davis, except for the time just before 10:00 p.m. Johnson testified that he never left Davis’s automobile on the trip from Franklin to Johnson’s father’s house in Nashville and that he arrived at his father’s house shortly before 10:00 p.m. Johnson’s father testified that Johnson arrived a few minutes before 10:00, just before the 10:00 p.m. news began.

After hearing all the evidence, a Tennessee jury convicted Johnson of three counts of first degree murder, two counts of assault with intent to commit murder, and two counts of armed robbery. The jury recommended that Johnson be sentenced to death on each count of first degree murder and to consecutive life sentences on each of the remaining counts. The trial court accepted this recommendation and imposed the death penalty. Johnson also murdered fellow death row inmate Laron Williams in 1985. A group of condemned convicts assaulted Williams during an exercise period. Williams had been sentenced to death for the murders of a police officer and a priest.

"Judge to decide on autopsy for executed killer," by Clay Carey and Chris Echegaray. (12-03-09)

A federal judge has moved up the hearing that will determine whether the state can perform an autopsy on a Tennessee death row inmate who was executed earlier this week. U.S. District Court Judge Robert Echols has already issued an order temporarily barring the state from performing an autopsy on the body of Cecil Johnson Jr., 53, who was put to death by lethal injection Wednesday.

Echols had originally scheduled the autopsy hearing for next Thursday. In an order issued late Wednesday night, he rescheduled it for Friday morning. In court filings, Johnson said he did not want the state to perform a routine autopsy on his body after his execution, saying it would violate his religious beliefs.

Johnson was sentenced to death for the 1980 shooting deaths of three people, including a 12-year-old boy, during a robbery at Bob Bell’s Market in 1980.

In court filings, Davidson County Medical Examiner Bruce Levy said this week that his office is bound by law to conduct autopsies on the body of anyone who dies of unnatural causes, including prisoners who are executed. He also said it is the only way to determine whether the execution was carried out properly.

ORIGINAL STORY

A federal judge will decide next week whether the state can perform an autopsy on a Tennessee death row inmate who was executed by lethal injection. U.S. District Court Judge Robert Echols has temporarily barred medical examiners from performing an autopsy on Cecil Johnson Jr., 53, until a Dec. 10 court hearing.

Johnson was put to death Wednesday in Riverbend Maximum Security Institution for the shooting deaths of three people, including a 12-year-old boy, during a robbery at Bob Bell's Market in 1980. "Cecil's religious conscience would not allow him to have an autopsy," said the Rev. Joe Ingle, a Nashville minister and death penalty opponent. "He felt like it was a desecration of his body."

Before Johnson died, his lawyers asked the court to block the scheduled autopsy. Dorinda Carter, spokeswoman for the state Department of Correction, said autopsies on executed inmates are routine. The Davidson County medical examiner is bound by law to conduct an autopsy on the body of anyone who dies of unnatural causes in Nashville, according to court filings. Executions are classified as unnatural deaths. "An autopsy is the only way I can rule out any possibility that the state failed to protect the rights of an inmate during incarceration and establish that the execution was carried out in the manner prescribed by law," Davidson County Medical Examiner Bruce Levy said in court documents.

Never accepted guilt

At a news conference Wednesday, Ingle and others who knew Johnson said he did not commit the murders. Johnson maintained his innocence for nearly three decades.

He was convicted in 1981 of first-degree murder for the deaths of Bobby Bell Jr., 12, James Moore, 41, and Charles House, 35. Johnson exhausted his appeals in 2008, and an execution date was set.

Joe McGee, a minister who counseled Johnson for many years, said Johnson walked into prison an angry man but later changed and seemed at peace near the end. "He said, 'If it's God's will, I'm willing,' " McGee said. The Rev. James Thomas, of Jefferson Street Missionary Baptist Church, served as Johnson's spiritual adviser and said Johnson winked at a group of family and friends shortly before he was put to death. "Death had no power over him," Thomas said.

About 60 people showed up for an anti-death penalty vigil at Hobson United Methodist Church in East Nashville on Wednesday night, and a handful of protesters gathered outside the prison.

Ingle said Johnson's family is planning a memorial service when the state releases his body. Johnson wanted to be buried in a cemetery in Las Vegas court records show.

Tennessee Coalition to Abolish State Killing

State v. Johnson, 632 S.W.2d 542 (Tenn. 1982) (Direct Appeal).

Defendant was convicted in the Davidson County Criminal Court, A. A. Birch, Jr., J., of three counts of murder in the first degree, two counts of assault with intent to commit murder in the first degree, and two counts of robbery accomplished with the use of a deadly weapon, and defendant was sentenced to death. On appeal, the Supreme Court, Cooper, J., held that: (1) prosecution witness who had been defendant's alibi witness until he changed his story shortly before trial did not have his constitutional rights violated by certain acts of the prosecution; (2) fact that, in questioning prosecution witness, prosecution brought out the fact that witness had been granted immunity from prosecution in exchange for his testimony did not prejudice defendant; (3) no prejudice resulted from a five to ten minute differential between the time frame for the crime set forth in the motion to require defendant to give notice of his intention to offer a defense or alibi and the time frame proven by the witnesses who testified; (4) the trial court properly excluded testimony of expert witnesses on the validity of the death penalty as a deterrent to crime, the moral and ethical standards of conduct of western civilization, and the relationship between youth and the accountability for decision making; (5) the evidence sustained jury's imposition of the death penalty on its findings of two aggravating circumstances and the lack of any mitigating circumstance; and (6) the trial court properly struck the affidavits of a juror and counsel for defendant who had telephone conversation with another juror which were submitted in support of defendant's motion for a new trial. Affirmed. Brock, J., concurred in part, dissented in part, and filed opinion.

COOPER, Justice.

This case is before us on direct appeal by Cecil C. Johnson, Jr., from a judgment entered in the Circuit Court of Davidson County, Tennessee. See T.C.A. s 39-2406. The judgment approved the jury's verdicts finding appellant guilty of three counts of murder in the first degree, two counts of assault with intent to commit murder in the first degree, and two counts of robbery accomplished with the use of a deadly weapon. The sentence imposed on each murder conviction was death by electrocution. Appellant also was sentenced to serve four consecutive life terms on the assault with intent to commit murder in the first degree and robbery convictions. On review, we find no material error in the trial record and affirm the several convictions.

The crimes for which appellant stands convicted were committed on July 5, 1980. There is evidence that on that day, at about 9:45 p. m., appellant went to the convenience market on Twelfth Avenue South in Nashville, Tennessee, which was owned and operated by Bob Bell, Jr. Appellant pointed a gun at Mr. Bell and ordered him and Lewis Smith, who was in the store working on a boat motor at the request of Mr. Bell, to go behind the store counter. Mr. Bell's twelve year old son, Bobbie Bell, was already behind the counter.

While appellant and his captives were behind the counter, a woman and two children entered the market. Appellant concealed his gun and told his captives to act naturally and to wait on the customers. As soon as the customers left, appellant ordered Bobbie Bell to fill a bag with money from the cash register; Bobbie obeyed. Appellant then searched Smith and Bell, taking Smith's billfold.

At that moment, Charles House stepped into the market, and was ordered out by appellant; House obeyed. Almost immediately thereafter, appellant began shooting his captives. Bobbie Bell was shot first. Smith threw himself on top of Bobbie to protect him from further harm, and was himself shot in the throat and hand. Appellant then walked toward Bob Bell, who was on the floor behind the counter, pointed the gun at Bell's head and pulled the trigger. Fortunately, Bell threw up his hands and the bullet hit him in the wrist, breaking it. Appellant ran from the market.

Bell got a shotgun from under the store counter, preparatory to chasing appellant. He heard two gunshots outside the market. He looked toward the front of the store and saw appellant standing beside an automobile parked at the entrance. Bell chased after appellant. As he passed the automobile, he saw that a cab driver and his passenger had been shot. The passenger was later identified as Charles House, the customer who had entered the market only moments before appellant began shooting his captives and who was acquainted with appellant. Both the cab driver, James E. Moore, and Mr. House died from a gunshot wound.

Appellant was arrested on July 6, 1980, as the result of information given police officers by Bell immediately after the robberies and murders. Subsequently, both Bell and Lewis Smith identified appellant as the perpetrator of the crimes and testified to that effect at the trial. Debra Ann Smith, the customer who came into the market with the children, also identified appellant and placed him behind the store counter with Bell, Bell's son, and Lewis Smith.

In addition to this eyewitness testimony, appellant was tied into the crimes by the testimony of Victor Davis, who had spent most of July 5, 1980, in company with the appellant. During the police investigation, Davis gave statements to the prosecution and to the defense that tended to provide an alibi for appellant. In essence, Davis said that he and appellant were together continuously from about 3:30 p. m. on July 5, 1980, until about midnight and that at no time did they go to Bell's Market. However, four days before the trial, and after his arrest for carrying a deadly weapon and for public drunkenness, Davis gave a statement to the prosecution, which incriminated appellant. In the trial Davis, who was promised immunity from prosecution in the Bell affair, testified in accord with his last statement.

According to Davis, he and appellant left Franklin, Tennessee, about 9:25 p. m. and arrived in Nashville in the vicinity of Bell's Market shortly before 10:00 p. m. Appellant then left Davis's automobile, after stating that he was going to rob Bell and was going to try not to leave any witnesses.

Davis testified that he next saw appellant, some five minutes later, near appellant's father's house which was only a block or a block and a half from Bell's Market. At that time, appellant was carrying a sack and pistol. Appellant discarded the pistol as he got into Davis's automobile and said, “I didn't mean to shoot that boy.” Davis retrieved the gun and sold it the next day for $40.00. Davis further testified that after he picked up appellant, they went directly to appellant's father's house, arriving a little after 10:00 p. m. There, in the presence of Mr. Johnson, Sr., appellant took money from the sack, counted approximately $200.00, and gave $40.00 of it to Davis.

Appellant took the stand in his own behalf and denied being in the Bell Market on July 5, 1980. His testimony as to events of the day generally was in accord with Davis's testimony, except for the crucial minutes before 10:00 p. m. when witnesses placed appellant in Bell's Market. Appellant testified that he never left the Davis automobile on the trip from Franklin to his father's house in Nashville, and that he arrived at his father's house shortly before 10:00 p. m. Mr. Johnson, Sr., fixed the time of arrival of appellant at a few minutes before 10:00 p. m., by testifying that appellant arrived as a television program ended and the 10:00 p. m. news came on. Appellant's girl friend, who talked with appellant on the telephone while appellant was at his father's home, fixed the time as being ten to fifteen minutes before 10:00 p. m. Appellant further testified that the money counted in the presence of his father was money he had won gambling in a street game in Franklin, Tennessee.

The jury accepted the prosecution evidence, including the identifications of appellant as the person who committed the robberies and murders, and found appellant guilty of murder in the first degree in killing Robert Bell III, James E. Moore, and Charles H. House, of assault with intent to commit murder in the first degree in the shooting of Lewis Smith and Robert Bell, Jr., and of the robbery of Smith and Bell.

The appellant does not specifically challenge the sufficiency of the convicting evidence, but does insist the prosecution was guilty of improprieties which had “a cumulative effect denying the (appellant's) right to a fair trial complying with due process and hindering the effectiveness of his counsel in preparing and conducting the defense.” Under this general assignment, appellant insists the prosecution violated law and ethics in coverting the crucial alibi witness, Victor Davis, into a prosecution witness hostile to the defense.

The thread of appellant's argument throughout his brief of this assignment, and in his oral argument before this court, is that Davis was a “declared witness” for the defense; and that, having been so declared, the prosecution somehow was prohibited from questioning Davis and getting him to change his “story”-that, it was not fair to permit the defense to build an alibi based on the initial statements given by Davis and then have the prosecution get Davis to change his story shortly before trial.

It is well settled that prospective witnesses are not partisans and do not belong to either party, but should be regarded as spokesmen for the facts as they see them. See Gammon v. State, 506 S.W.2d 188, 190 (Tenn.Crim.App.1974). The purpose of an investigation and trial is to get to the truth. This sometimes entails the interrogation of witness on several occasions before truth is distilled in its purity. Neither party can have its investigation limited merely by a declaration that a witness will testify in behalf of the other party.

In addition to the general argument, appellant points to specific acts of the prosecution, which appellant insists were violative of both law and professional ethics. Appellant complains of the fact that the district attorney general caused Davis to be detained for questioning within a week of the trial date, the fact that Davis was questioned in the absence of his counsel, the time of day the questioning took place and Davis's physical condition, the fact that the prosecution made Davis aware of the possibility that the State would turn up evidence against Davis and move against him, and the ultimate grant of immunity to Davis from prosecution for crimes growing out of the Bell incident. Appellant argues that these actions by the district attorney general and his associates, violated Davis's Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Amendment rights. We see no basis for the argument, either in fact or law. First, we find nothing in the record to show a violation of Davis's constitutional rights. The evidence shows that Davis's detention was as the result of a lawful arrest on charges of public drunkenness and the unlawful possession of a deadly weapon. The record also shows that Davis knowingly and voluntarily waived his right to counsel when he learned that the interrogation would be limited to the Bell incident. On the Monday following the interrogation, Davis and his attorney went to the office of the district attorney general, where Davis repeated his statement in the presence of his counsel, had it reduced to writing, and signed it. Furthermore, when Davis testified in the trial, both parties were allowed to fully explore the circumstances of Davis's arrest and detention, the fact that Davis had changed his “story” from the one he had given earlier to the prosecution and the defense, and that the State had promised Davis immunity from prosecution for any crime predicated on the Bell incident. This exploration, of course, was crucial to the jury's evaluation of the credibility of Davis. Second, even if the law enforcement officials violated Davis's right to be secure in his person, his right not to be compelled to be a witness against himself, and his right to have counsel present during any interrogation, these are rights personal to Davis and can only be asserted by him and not by some other person, such as appellant, who might be adversely affected by information elicited during the detention and interrogation. Cf. Brown v. United States, 411 U.S. 223, 230, 93 S.Ct. 1565, 1569, 36 L.Ed.2d 208 (1973); United States v. Nobles, 422 U.S. 225, 95 S.Ct. 2160, 45 L.Ed.2d 141 (1975); Faretta v. California, 422 U.S. 806, 816, 95 S.Ct. 2525, 2533-34, 45 L.Ed.2d 562 (1975).

Appellant also charges that in the guise of questions and in closing argument, the prosecution made declarative statements calculated to bolster the credibility of Davis to the prejudice of the appellant. With these charges in mind, we have re-read those parts of the record cited by appellant and find no basis for the charge.

Appellant also takes issue with the fact that, in questioning Davis, the prosecution brought out the fact that Davis had been granted immunity from prosecution in exchange for testimony relative to the Bell incident. Appellant argues that this was misleading in that the prosecution had not taken procedural steps to insure that Davis had immunity. Appellant does not indicate how he could be prejudiced by the action of the prosecution, nor can we see any basis for prejudice resulting from the statement that Davis had been granted immunity. Such a fact could serve only to diminish Davis's credibility in the eyes of the jury to the advantage of appellant. Furthermore, appellant's insurmountable problem in this case was not Davis's testimony, but the testimony of the three eyewitnesses, two of whom looked into the barrel of the pistol held by appellant and were shot by him.

Appellant further insists that the prosecution improperly withheld notice to the defense of the existence of the witness, Debra Ann Smith, until eleven days before the trial began. Interestingly enough, no complaint was directed to the prosecution's action, or rather inaction, until the motion for new trial was filed in behalf of appellant. This probably was due to the fact that the prosecution gave notice that Debra Ann Smith would be a witness within the minimum time requirement set forth in Rule 12.1(b) of the Tennessee Rules of Criminal Procedure. But whatever the reason, we now find nothing in the record to indicate that the time of notification hindered counsel's preparation for trial or his ability to adequately represent his client in the trial.

Appellant also takes issue with the time frame for the crimes set forth in the motion by the prosecution to require appellant to give notice of his intention to offer a defense or alibi. The time frame for the crimes set forth in the motion was “July 5, 1980, between 10:00 p. m. and 10:10 p. m.” On trial, the proof indicated that the crimes were likely committed between 9:55 p. m. and 10:00 p. m. Appellant insists that he was prejudiced by the five to ten minute time differential. How he was prejudiced is not clear, since appellant did not limit his alibi evidence to the ten minute period set forth in the motion, but covered the period from 9:00 a. m. on July 5, 1980, until the following morning. This testimony necessarily would be the same for both time frames, and no prejudice could result from a five to ten minute differential between the time frame for the crimes set forth in the motion and the time frame proven by the several witnesses who testified.

In a general assignment of error directed to the sentencing hearing, appellant insists that evidentiary rulings by the trial court, “constitute error, deprive the jury of guidance needed to evaluate the (appellant's) mitigating circumstances, and result in an arbitrary and capricious sentence of death.” In the course of discussion of this assignment, appellant insists that the trial court erred in excluding testimony of expert witnesses on the validity of the death penalty as a deterrent to crime, the moral and ethical standards of conduct of western civilization, and the relationship between youth and accountability for decision making. The experts were to testify on these issues generally, since neither of them had ever seen or spoken with the appellant, or had reviewed his record.

In this state, the legislature has provided that where it is found that the defendant is guilty of first degree murder, a second proceeding is to be held before the same jury to determine the sentence-either life imprisonment or death-to be imposed T.C.A. s 39-2404(a). The jury may impose the death penalty only upon finding that one or more aggravating circumstances, listed in the statute, are present, and further that such circumstance or circumstances are not outweighed by any mitigating circumstance. T.C.A. ss 39-2404(g) and (i). The burden of proof rests upon the state to establish the aggravating circumstances beyond a reasonable doubt and the jury must specifically find that these outweigh any mitigating circumstances before they are justified in imposing the death penalty. T.C.A. s 39-2404(f). These separate determinations must be put in writing and given to the trial judge along with the sentence of death, thus assuring that the jury has gone through the correct analysis in arriving at a death sentence. T.C.A. s 39-2404(g).

In Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S. 586, 98 S.Ct. 2954, 2965, 57 L.Ed.2d 973 (1978), the Supreme Court points out that the: Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments require that the sentencer, in all but the rarest kinds of capital cases, not be precluded from considering as a mitigating factor, any aspect of a defendant's character or record and any of the circumstances of the offense that the defendant proffers as a basis for a sentence less than death. The Court emphasized, however, in a footnote to this sentence that “nothing in this opinion limits the traditional authority of a court to exclude, as irrelevant, evidence not bearing on the defendant's character, prior record, or the circumstances of his offense.” 98 S.Ct. at 2965 n. 12. The legislature of this state has gone even further than is required by Lockett v. Ohio, supra, and has provided in T.C.A. s 39-2404(c)

In the sentencing proceeding, evidence may be presented as to any matter that the court deems relevant to the punishment and may include, but not be limited to, the nature and circumstances of the crime; the defendant's character, background history, and physical condition; any evidence tending to establish or rebut the aggravating circumstances enumerated ... below; and any evidence tending to establish or rebut any mitigating factors. Any such evidence which the court deems to have probative value on the issue of punishment may be received regardless of its admissibility under the rules of evidence. (emphasis supplied)

The evidence tendered by the appellant and excluded by the trial court was not relevant to, nor did it have any probative value on the issue of punishment, but consisted of matters properly to be considered by the legislature in deciding whether the death penalty is ever a justified punishment for a person convicted of murder in the first degree and, if so, the circumstances under which the death penalty should be imposed. Cf. Houston v. State, 593 S.W.2d 267 (Tenn.1980), cert. denied, 449 U.S. 891, 101 S.Ct. 251, 66 L.Ed.2d 117. The trial court thus correctly excluded the evidence.

In this case, with respect to each of the three murders, the jury unanimously found the following aggravating circumstance to exist: (6) The murder was committed for the purpose of avoiding, interfering with, or preventing a lawful arrest or prosecution of the defendant or another. T.C.A. s 39-2404(i)(6) and, in addition with respect to the killing of Robert Bell, III, the jury found the following statutory aggravating circumstances: (3) The defendant knowingly created a great risk of death to two or more persons, other than the victims murdered during his act of murder. T.C.A. s 39-2404(i)(3) (7) The murder was committed while the defendant was engaged in committing robbery. T.C.A. s 39-2404(i)(7) The jury also specifically found that there were no mitigating circumstances sufficiently substantial to outweigh the statutory aggravating circumstances, and fixed appellant's sentence at death on each finding of murder in the first degree.

From our review of the record, we are of the opinion that the evidence proves appellant's guilt of the several crimes charged beyond a reasonable doubt. We are also of the opinion that the evidence supports the jury's imposition of the death penalty on its finding of aggravating circumstances listed in the Tennessee Death Penalty Act and the lack of any mitigating circumstance. Further, we are of the opinion that under the circumstances of this case, as shown by the evidence, the imposition of the death penalty by the jury was neither arbitrary nor excessive or disproportionate to the penalty imposed in similar cases.

Appellant sought to have the trial judge, in his instructions to the jury, inform the jury that evidence had been tendered to show that the death penalty has no deterrent effect upon crime and that the death of appellant would not benefit society or comply with moral and ethical standards of the day, and that the trial judge had excluded the evidence. Appellant insists it was error for the trial judge not to give the requested instruction since appellant's counsel had indicated to the jury in his opening statement that such evidence would be forthcoming. We see no merit in this insistence. The trial judge is under no duty to specifically note or explain his rulings on the admissibility of evidence, nor should he call the jury's attention to evidence that has been excluded. The jury's responsibility is to decide the issues on the evidence submitted, not on what the appellant attempted to show.

Appellant takes issue with the action of the trial court in striking the affidavits of a juror and counsel for appellant, which were submitted to the court in support of appellant's motion for new trial. Appellant insists the affidavits reveal that the sentence of death in this case is the result of extraneous, prejudicial information and is the product of mistake and that appellant is entitled to a new sentencing hearing. On reading the affidavits, which were included in the record in this court, we are of the opinion that the action of the trial court was proper; and, in any event, the facts set forth in the affidavits do not show that the sentence of death was either the result of extraneous, prejudicial information, or was the product of mistake.

The substance of the juror's affidavit was that she did not understand that she could have voted for life; that she felt like she was locked in (on the death penalty); that she thought she would have to explain her vote to the judge if she voted for life; that she was afraid the judge would look at her and say, “Well, why did you do it?” that she was not afraid of the judge, but was afraid that she would be embarrassed. The juror further stated that she now believes, deep down in her heart, that Cecil Johnson did not commit the crimes.

It is settled law in this state that a juror can not impeach her verdict, and that a new trial will not be granted upon the affidavit of a juror that she misunderstood the instructions given the jury by the trial judge, provided the instructions were correct. Batchelor v. State, 213 Tenn. 646, 378 S.W.2d 751, 754 (1964); Norris v. State, 22 Tenn. 333 (1842). See also Montgomery v. State, 556 S.W.2d 559 (Tenn.Crim.App.1977). The instructions in this case were complete and clear, the jury had the instructions before them as they deliberated, and, according to the affidavit, the juror in question read the instructions. She can not now impeach her verdict.

The affidavit of counsel for appellant was based on a telephone conversation he had with juror George B. Davis. When the contents of the affidavit were made public, Mr. Davis filed a statement with the court taking issue with parts of the affidavit and clarifying others. On motion, the trial judge struck both the affidavit and Mr. Davis's statement, which was in letter form. We agree with his action. The documents show no more than that the jurors understood the court's instructions and properly applied them to the evidence as they found it, despite a reluctance to impose a death sentence. Furthermore, there is nothing in the documents to indicate that the jury based its decision on any extraneous matter or outside prejudicial influence, as charged by appellant.

In a supplemental assignment of error, appellant questions the propriety of the trial court's excusing three jurors for cause. Appellant insists that the trial court excluded these jurors on the basis of a statement of general opposition to the death penalty, and that this was in violation of the rule set forth in Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510, 513-514, 88 S.Ct. 1770, 1772, 20 L.Ed.2d 776 (1968), and followed by this court in State v. Harrington, 627 S.W.2d 345 (Tenn.1981). Our view of the position taken by the jurors on voir dire examination differs from that of the appellant. As we read the record each of the jurors clearly indicated that he would not consider the death penalty under any circumstances and would automatically vote against its imposition, whatever the evidence and whatever the instructions of the trial court. The jurors having taken this stand, it was mandatory for the trial court to excuse them from service, if the jury were to be impartial.

All assignments of error are overruled. The judgment of conviction in each case and the sentence imposed are affirmed. The death sentence will be carried out as provided by law on June 29, 1982, unless otherwise stayed or modified by appropriate authority. Costs are taxed to appellant. HARBISON, C. J., and FONES and DROWOTA, JJ., concur. BROCK, J., dissents in part and concurs in part.

BROCK, Justice, concurring in part and dissenting in part. For the reasons stated in my dissent in State v. Dicks, Tenn., 615 S.W.2d 126 (1981), I would hold that the death penalty is unconstitutional; but, I concur in all other respects.

Johnson v. State, 797 S.W.2d 578 (Tenn. 1990) (Postconviction Relief)

Murder defendant who had been sentenced to death brought petition for postconviction relief. The Criminal Court, Davidson County, A.A. Birch, J., denied the petition. Defendant appealed. The Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed in part, and reversed in part, and set aside the death sentence as imposed and remanded the case. Appeal was taken. The Supreme Court, O'Brien, J., held that State's counsel did not attempt to minimize jury's degree of responsibility in the sentencing decision or indicate to jurors that they were not solely responsible for authorizing the death penalty. Judgment of trial court reinstated and affirmed. Drowota, C.J., concurred and issued an opinion.

O'BRIEN, Justice.

This post-conviction proceeding is before the Court on joint applications for permission to appeal from the judgment of the Court of Criminal Appeals. The State takes issue with that court's judgment ruling that the prosecuting attorney's argument at trial was violative of the Eighth Amendment and whether or not the defendant waived any right to post-conviction relief on his claim of prosecutorial misconduct. The defendant-petitioner has raised twenty-six (26) issues about equally divided between the guilt phase at trial and the sentencing proceeding.

On 19 January 1981 petitioner was found guilty in a jury trial on three (3) counts of first degree murder; two (2) counts of assault with intent to commit murder, and one (1) count of armed robbery. He was sentenced to death by the jury on each of the first degree murder charges and received consecutive life sentences on each of the other charges. On 3 May 1982 this Court affirmed the convictions and sentences imposed upon the petitioner.FN1 A petition to rehear was denied on 21 May 1982. On 4 October 1982 the United States Supreme Court denied a petition for writ of certiorari. A petition to rehear in that court was denied on 28 October 1982. This petition for post-conviction relief was filed on 15 March 1983 and denied after an evidentiary hearing. The petitioner here appealed the trial court judgment to the Court of Criminal Appeals which on 20 January 1988 affirmed, in part, and reversed in part, the judgment of the trial court dismissing the petition for post-conviction relief. The intermediate court set aside the death sentences imposed in the trial court and remanded the case for a new sentencing hearing on the first degree murder sentences. FN1. State v. Johnson, 632 S.W.2d 542 (Tenn.1982).

We first address the Court of Criminal Appeals judgment remanding the case for a new sentencing hearing. We reverse that court's judgment and reinstate the sentences imposed in the trial court.

The State of Tennessee, appellant here, citing Caldwell v. Mississippi, 472 U.S. 320, 105 S.Ct. 2633, 86 L.Ed.2d 231 (1985),FN2 argues that the Court of Criminal Appeals erred in its holding that defendant did not waive any right to post-conviction relief by his failure to attack the prosecuting attorney's arguments on the basis raised here, either at trial or on direct appeal from his conviction. Moreover, they say he failed to allege any reason for his failure to assert this issue at the appropriate time in the prior proceedings. They further argue that defendant has not shown that Caldwell, supra, created a new constitutional right which must be applied retroactively.

FN2. Caldwell was a case on direct appeal from a capital murder conviction and death sentence in the State of Mississippi. On certiorari the United States Supreme Court held that the Eighth Amendment prohibits the imposition of a death sentence by a sentencer that has been led to believe that the responsibility for determining the appropriateness of defendant's capital sentence rests elsewhere. The sentence of death was vacated, the judgment was reversed to the extent it sustained the imposition of the death penalty, and the case was remanded for further proceedings. Subsequently a second petition for certiorari was granted and the entire judgment was vacated and the case remanded to the Supreme Court of Mississippi for further consideration in light of Griffith v. Kentucky, 479 U.S. 314, 107 S.Ct. 708, 93 L.Ed.2d 649 (1987) and Allen v. Hardy, 478 U.S. 255, 106 S.Ct. 2878, 92 L.Ed.2d 199 (1986).

In reference to the procedural waiver of the Caldwell issue due to the defendant's failure to raise it at trial or on direct appeal the intermediate court held that the essential nature of the problem was discussed in the petition for post-conviction relief, even in advance of the opinion in Caldwell. They expressed their agreement with the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals decision in Dutton v. Brown, 812 F.2d 593, which involved federal habeas corpus jurisdiction. In the Dutton case the court discussed Reed v. Ross, 468 U.S. 1, 104 S.Ct. 2901, 2911, 82 L.Ed.2d 1 (1984). In Reed the court ruled that cause existed for defense counsel's failure to raise an issue when a subsequent Supreme Court decision articulated a constitutional principle not previously recognized. The Court of Criminal Appeals then ruled that this novel-issue principle is equally applicable in State post-conviction litigation. They reversed the judgment of the trial court denying relief on the sentence imposed and remanded the case for a new penalty hearing.

T.C.A. § 40-30-105 expressly provides for relief when grounds stated in a post-conviction petition were not recognized as existing at the time of conviction and require constitutional retrospective application.

T.C.A. § 40-30-112 defines when a ground for relief is previously determined or waived. In the former, a ground for relief is previously determined if a court of competent jurisdiction has ruled on the merits after a full and fair hearing. Waiver is implied if a petitioner knowingly and understandingly fails to present a ground of relief for determination in any proceeding before a court of competent jurisdiction in which the grounds could have been presented. A rebuttable presumption arises that a ground for relief not raised in any such proceeding has been waived.

We do not agree with the State's argument that Caldwell, supra, did not create a new constitutional right, nevertheless there is no constitutional mandate which either prohibits or requires retrospective effect. See Linkletter v. Walker, 381 U.S. 618, 85 S.Ct. 1731, 1737, 14 L.Ed.2d 601 (1965). More recently, United States Supreme Court decisions indicate the intent that new rules for conduct of criminal prosecutions are to be applied retroactively to all cases, State or Federal, pending on direct review which are not yet final. See Griffith v. Kentucky, 479 U.S. 314, 107 S.Ct. 708, 716, 93 L.Ed.2d 649 (1987). In Teague v. Lane, 489 U.S. 288, 109 S.Ct. 1060, 1075, 103 L.Ed.2d 334 (1989) the Court adopted a specific view on retroactivity for cases on collateral review, holding that unless they fall within an exception to the general rule, new constitutional rules of criminal procedure will not be applicable to those cases which have become final before the new rules are announced.FN3. See Penry v. Lynaugh, 492 U.S. 302, 109 S.Ct. 2934, 106 L.Ed.2d 256 (1989) and Sawyer v. Smith, 497 U.S. 227, 110 S.Ct. 2822, 111 L.Ed.2d 193 (1990).

In deciding against retroactive application in this case we are not unmindful of the court's admonition in Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280, 96 S.Ct. 2978, 2991, 49 L.Ed.2d 944 (1976), that the penalty of death is qualitatively different from a sentence of imprisonment and because of that difference there is a corresponding difference in the need for reliability in the determination that death is the appropriate punishment in a specific case. If constitutional error occurred it would require appropriate palliative response. However, the appellate courts of this State may notice plain error at any time, at any stage of the proceedings, where necessary to do substantial justice. Tenn.R.Crim.P. 52. We have examined this record carefully. We do not find, as did the intermediate court, that State's counsel, in their statements to the jury at the sentencing hearing, attempted to minimize the jury's degree of responsibility in the sentencing decision or that the jurors themselves were not solely responsible for authorizing imposition of the death penalty.FN4. The entire opening statement and closing argument of State's counsel is appended to this opinion as an appendix.

That portion of the District Attorney's opening statement and final argument which the lower court found constitutionally offensive is as follows: “Your issue today is whether Cecil Johnson should experience the death penalty. Now in order to arrive at that and we (sic) and we asked you, if you will recall on the voir dire and the judge will explain to you and I am satisfied the defense will, you also have the option of life imprisonment on those three murders. Those are your two options. That is all you have got to debate. You can, you can vote to [have] him executed- now incidentally it is not you doing that. You are representing the reflective judgment, as I have already said, of the people of Tennessee and of the Supreme Court. Or you can sentence him to life imprisonment. (Emphasis in Court of Appeals opinion).

The Court of Appeals also found a part of the prosecution argument to be an attempt to minimize the jury's degree of responsibility in the sentencing decision: The jury is but one step in the process. The Legislature, as General Shriver spoke earlier, has enacted the death penalty, has put that into the body of the law in Tennessee, said that it is applicable in first degree murder cases. It set forth under what circumstances and how the death penalty should be considered and whether or not it will be imposed. And certainly the jury is, is part of that system. But it is just part of a process of determining what is the proper appropriate punishment for, in this case, Cecil Johnson. For his responsibility for three, three separate first degree murders. (Emphasis in Court of Appeals opinion).

That portion of the District Attorney General's opening statement which preceded the remarks found objectionable by the Court of Appeals is as follows: May it please the court, and ladies and gentlemen, you have found Cecil Johnson guilty of murder in the first degree. As we explained when we were questioning you, when you were picked, this is a two-part process. Now your job is to decide what his punishment should be on those charges, the three, three sentences of, or the three charges of murder in the first degree. Now, I think the first thing you need to keep in mind is that the debate here is not whether there ought to be a death penalty. That has already been decided. The United States Supreme Court has decided that. The Tennessee State Legislature which represents the people, and therefore the collective judgment of the people in Tennessee and in Davidson County, the Tennessee State Legislature said there is a death penalty available as a punishment for murder in the first degree. So you are not debating whether there ought to be a death penalty in general.

The part of the closing argument, coming before and after the portion excerpted by the lower court as improper, contains a great deal more to enable a reviewing court to determine if the argument falls short of appropriate constitutional standards: Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, we are once again at a point of argument. We are, however at the sentencing stage as I know all of you are well aware. It is though, what is at least terms (sic) in the statute as argument. As far as I am concerned at this point though I think that what we are in a position of doing is really trying to, what I hope to do is not much argument and more of a discussion with regards to the duties and responsibilities that all of you as jurors are now facing.

When you were called in originally and individually voir dired and asked questions, one of the things, probably the most important thing that you were questioned about by both sides were your feelings about the death penalty. Certainly that is something that before you entered into this courtroom you had thoughts about, you had perhaps discussed, but you had never been in a situation in Court where the death penalty would necessarily be a reality.

If nothing more, we I am sure conveyed to you that this case was, of course, important, and, of course, significant but in addition we conveyed to you that any decision made in this case was not going to be an easy one regardless of what the proof was, regardless of how the evidence came out from that witness stand, the ultimate decisions that you had to make as jurors were going to be difficult ones. And they are made all that much more difficult by the fact that the death penalty is involved.

Now, all of you said at the beginning that you could consider the death penalty and that is all that we ask of you, is to consider the death penalty as it is set forth in the statute, because in order for you to take the oath that the Court administered to you, you had to be able, you had to be in a position to say that you could consider the law as it is in Tennessee. That you could make a true determination in this case according to the law and evidence. And that is what we are down to now. We are past the stage of guilt. We are past the question of guilt. Guilt has been resolved and determined by the jury yesterday afternoon, yesterday evening. In that resolution as you all remember, you found the defendant guilty of first degree murder. Not in one case, or not in one instance, but in three. And your function now has to do with taking those three situations, those three victims, the cases involving those three people and determining whether or not the law dictates that the death penalty shall be imposed. I will be very frank with you that you have convicted the defendant, he already, (sic) you have already given him a considerable period of time and certainly the easiest decision perhaps confronting the jury is to simply conclude that a life sentence on these three murders is what is justified.

While that may be the easiest decision, the question you as individual jurors must ask yourself is how does that fit with what the law says, with what the law is in this State. That's what we are here about. That's what, that's what our entire argument here is about. Is looking at the law in the State of Tennessee and what do you as a juror, as a body, as jurors, what do you do? . . . . . Again, I can't emphasize enough that your situation is going to be unusual in the sense that you are going to have to, to (sic) assess the possibility, the punishment possibilities as to three victims. Not one, but three. Any one of these individuals, Little Bob, James Moore, Charles House, any one of them, their deaths, just their single death alone would be enough for this jury here to be considering and pondering whether or not a life sentence or whether it is death by electrocution....

Ladies and gentlemen, the court will define for you the law in this particular case. It will set out the formula that you need to, (sic) to apply, how you must go about assessing what is the proper punishment.

Both in the opening statement and in the closing argument a great deal more was said to define, explain, and discuss aggravating circumstances and mitigating circumstances and the jury's duty in reference to the consideration of each. In the closing argument the prosecutor also reviewed the evidence and the circumstances of the homicides for which defendant had been convicted.

The trial judge instructed the jury that statutory law required them to fix the punishment after a separate sentencing hearing to determine whether the defendant should be sentenced to death or life imprisonment and that their verdict must be unanimous as to either form of punishment. He instructed them on their duty to consider both aggravating and mitigating circumstances in accordance with statutory law on the subject.

Taking all of the foregoing in context, there is no possibility that the sentencing jury was led to believe that responsibility for determining the appropriateness of a death sentence rested not with them or suggested in any way that they might shift their sense of responsibility to an appellate court. Neither the opening statement nor the closing argument contained any such message to the jury. We find considerable ambiguity in the inference made by the Attorney General that the United States Supreme Court had decided there ought to be a death penalty. But, in the light of the balance of his statement, we do not find that remark to fail the scrutiny of the capital sentencing determination required under the Eighth Amendment.

The defendant's application for appeal includes twenty-six issues. The majority of these were considered on direct appeal FN5 and, therefore, have been previously determined. Others have been waived by failure to present them at trial or on direct appeal. T.C.A. § 40-30-112. We have granted the application to consider the intermediate appellate court's treatment of the issues. We now find that they were properly reviewed, considered and dealt with appropriately. FN5. State v. Johnson, supra.

The judgment of the Court of Criminal Appeals reversing the trial court and remanding for a new sentencing hearing is reversed. The judgment of the trial court is reinstated and affirmed. In all other respects, the judgment of the Court of Criminal Appeals is affirmed. Costs are assessed against the defendant. FONES, COOPER and HARBISON, JJ., concur. DROWOTA, C.J., files separate concurring opinion.

APPENDIX

OPENING STATEMENT OF STATE'S COUNSEL

THE COURT: All right, are there any opening statements? MR. SHRIVER: Yes, if Your Honor please. May it please the Court, and ladies and gentlemen, you have found Cecil Johnson guilty of murder in the first degree. As we explained when we were questioning you, when you were picked, this is a two part process. Now your job is to decide what his punishment should be on those charges, the three, three sentences of, or the three charges of murder in the first degree. Now the, I think the first thing you need to keep in mind is that the debate here is not whether there ought to be a death penalty. That has already been decided. The United States Supreme Court has decided that, The Tennessee State Legislature which represents the people, and therefore the collective judgment of the people in Tennessee and in Davidson County, the Tennessee State Legislature has said there is a death penalty available as a punishment for murder in the first degree. So you are not debating whether there ought to be a death penalty in general. Your issue today is whether Cecil Johnson should experience the death penalty. Now in order to arrive at that and we asked you, if you will recall on the voir dire and the Judge will explain to you and I am satisfied the defense will, you also have the option of life imprisonment on those three murders. Those are your two options. That is all you have got to debate. You can, you can vote to him executed-now incidentally it is not you doing that. You are representing the reflective judgment, as I have already said, of the people of Tennessee and of the Supreme Court. Or you can sentence him to life in prison. In order to arrive at that judgment, you have to weigh certain things.