32nd murderer executed in U.S. in 2011

1266th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Virginia in 2011

109th murderer executed in Virginia since 1976

Executed August 18, 2011 9:14 p.m. by Lethal Injection in Virginia

32nd murderer executed in U.S. in 2011

1266th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Virginia in 2011

109th murderer executed in Virginia since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(32) |

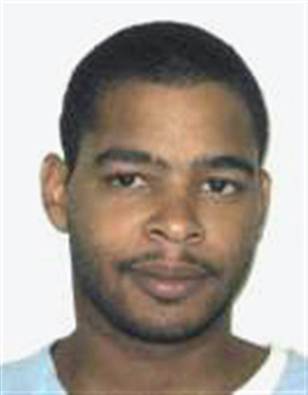

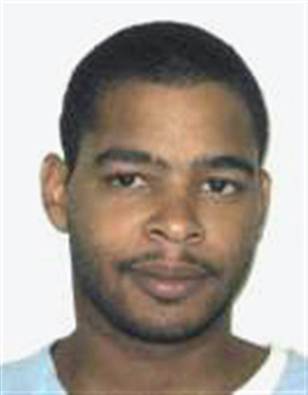

Jerry Terrell Jackson B / M / 20 - 30 |

|

Ruth Phillips W / F / 88 |

Citations:

Jackson v. Commonwealth, 267 Va. 178, 590 S.E.2d 520 (Va. 2004).(Direct Appeal)

Jackson v. Kelly, ____F.3d ____, WL 1534571(4th Cir. 2011). (Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

Confidential upon request.

Final Words:

None.

Internet Sources:

"Jerry Jackson executed by injection," by Peter Dujardin. (Saturday, August 20, 2011 5:32 AM EDT0

JARRATT — Jerry Terrell Jackson was put to death by lethal injection at 9:14 p.m. on Thursday at a state prison north of Emporia. Jackson, 30, who grew up in James City County, was convicted nine years ago for the 2001 rape and murder of an 88-year-old Ruth Phillips, a Williamsburg widow. Jackson thus became the 109th person executed by the state of Virginia since a nationwide moratorium on capital punishment ended in 1976. Jackson made no final statement.

At about 4 p.m. Thursday afternoon, the U.S. Supreme Court turned down his petition for a stay of execution, with two justices on the nine-member court — Ruth Ginsburg and Sonia Sotamayor — the lone members voting for the stay. His death brings the end of a nine years of legal battles after a 12-member jury in Williamsburg-James City County Circuit Court unanimously voted that Jackson be sentenced to die. Jackson's attorneys had contended the jury that issued that verdict never got a chance to hear the full extent of the severe and pervasive abuse Jackson suffered as a boy at the hands of his biological father and step-father.

In 2010, U.S. District Judge Leonie Brinkema granted Jackson a new sentencing hearing. She held a two-day hearing in 2008, gathering witness testimony on the abuse from Jackson's brother and sister. She found the testimony vivid, credible and powerful, and determined that his original trial attorneys were deficient in not having them testify. But Brinkema's ruling was reversed in April by the U.S. Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, clearing the way for the execution. Last Friday, Gov. Bob McDonnell on Friday denied Jackson's appeal for clemency, saying he could find "no compelling reason" to intervene.

Earlier in the day on Thursday, Jackson's family met with with a "contact visit," meaning they were allowed to touch and hug him during the stay. "He did visit with his family," said Larry Traylor, a spokesman with the Department of Corrections. "He also visited with his clergy and with his attorneys." Traylor didn't identify the family members or say how many were in attendance.

No members of Ruth Phillips' family were in attendance at the execution, Traylor said. The victim's son, Dick Phillips, of Williamsburg, had earlier told the Daily Press that he would not attend the execution. Though he supported the execution, he said he had no interest in seeing anyone die. The Greensville Correctional Center is a state prison in Jarrett, Va., about 13 miles north of Emporia off of Interstate 95.

Three large white passenger vans carrying the witnesses to the execution — including attorneys, press, clergy and others — went onto the facility grounds at 8:15 p.m. Outside the prison, it was a pleasant 731-degree night, with a gray and pink sky overhead after the sun set. Unlike with some executions that generate lots of media interest, this one was a quiet affair. There were few protestors outside, in their prescribed place on a grassy hill, on the street leading into the state prison.

"Jackson Executed for Rape, Murder of Williamsburg Woman," by Sam Thrift. (Friday, August 19, 2011)

Jerry Terrell Jackson was executed by lethal injection Thursday night at the Greensville Correctional Center in Jarratt. A Williamsburg-James City County Circuit Court jury convicted Jackson in 2002 for the rape and murder of 88-year-old Ruth Phillips, who was killed in her Williamsburg home in 2001. Jackson, who was raised in James City County, was 20 at the time. He was also convicted of burglary, robbery and petit larceny.

Maj. Steve Rubino of the James City County Police Department said on Aug. 16, 2001, Jackson broke into Phillips’ apartment, located in the Rolling Meadow Apartment Complex off Longhill Road, with the intent to steal. Phillips was asleep in her bed when she woke up to Jackson rifling through her purse. Jackson smothered Phillips with a pillow while he raped her, then stole $60 and her car.

Phillips' son, concerned because his mother didn't answer her phone and she was expected at church, discovered her body the next day. Rubino said a fingerprint from papers in Phillips' purse linked Jackson to the crime, along with DNA from hairs that were found on and around her body.

Jackson's attorneys had been hoping for an intervention that would stop the execution. They filed a petition for clemency on July 29, requesting Gov. Bob McDonnell commute the sentence of death to a sentence of life without the possibility of parole. McDonnell declined to intervene last week. Thursday afternoon, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected Jackson's appeal.

After Jackson's execution, Attorney General Ken Cuccinelli issued a statement, which said in part, "The just sentence of death has now been carried out. Our thoughts and prayers remain with the family and friends of Ruth Phillips."

"Rapist and killer of Williamsburg widow put to death," by Dena Porter. (AP August 19, 2011)

JARRATT - A man who raped and suffocated an 88-year-old widow has become Virginia's first inmate executed using a revised, three-drug cocktail. Jerry Terrell Jackson, 30, was pronounced dead at 9:14 p.m. Thursday at Greensville Correctional Center. He was sentenced to death for the 2001 rape and murder of seamstress Ruth Phillips in her Williamsburg apartment.

Asked whether he had any final words, Jackson shook his head and said "no" under his breath. As he waited for the drugs to be administered, he tapped his foot as he lay strapped to a stainless steel gurney. The execution team took about 15 minutes to insert two intravenous lines, one into each arm. Within four minutes of the lines being inserted, he was pronounced dead.

Richard Phillips, who found his mother dead on Aug. 26, 2001, said the execution was long overdue. Neither Phillips nor other members of Phillips' family witnessed the execution. Ruth Phillips, a widow for 30 years, followed her son to Virginia from New Hampshire in the late 1990s. She worked as a seamstress making slip covers and draperies until her death. Richard Phillips said he had wanted her to move close to him so that she would be safe. Authorities say Jackson broke into her apartment. When she awoke and found him rummaging through her purse, she offered him anything if he would leave. Instead, he put a pillow over her face and raped her. Jackson then fled in her car and used the $60 he stole from her apartment to buy marijuana.

"I'm sorry Mrs. Phillips lost her life due to something that I done," Jackson had said recently. "I'm sorry to Mr. Phillips that he hurt so much. I'm sorry that he lost his mother."

Like other states, Virginia recently replaced sodium thiopental with pentobarbital after a nationwide shortage of the sedative, which is administered before two other drugs that stop the inmate's breathing and heart. Attorneys in some states have contested the use of pentobarbital, but federal courts have ruled that the change is not significant enough to stop executions. Pentobarbital has been used in two dozen executions this year, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

Jackson nearly got a reprieve last year when U.S. District Judge Leonie Brinkema allowed a two-day evidentiary hearing in which Jackson's brother and sister testified about the abuse he suffered at the hands of his father and stepfather while growing up. Brinkema ordered that Jackson at the time should receive a new sentencing hearing, saying the testimony "painted a graphic picture of an unwarranted, continuous, sadistic course of conduct that terrorized and dehumanized Jackson throughout his childhood." But earlier this year, a federal appeals court overturned that ruling on a technicality.

In a telephone interview with The Associated Press last Friday, Jackson talked about the abuse, which began with a broken arm when he was 19 months old and continued with sexual abuse and beatings with a fist, belt and once a two-by-four for more than a decade. Jackson acknowledged killing Phillips. Even though he said it's not an excuse for what he did, Jackson said he doesn't think it would have happened if he could have escaped the abuse as a child. "I don't think I would have ended up this way," he said.

"Va. man executed for raping, killing an elderly woman." (Associated Press August 19, 3:16 AM)

JARRATT, Va. — A man who raped and suffocated an 88-year-old woman was executed, becoming Virginia’s first inmate to be given a lethal injection using a revised three-drug cocktail. Jerry Terrell Jackson, 30, was pronounced dead at 9:14 p.m. Thursday at Greensville Correctional Center. Asked if he had any final words, Jackson shook his head and said “no” under his breath. As he waited for the drugs to be administered, he tapped his foot as he lay strapped to a stainless steel gurney. The execution team took about 15 minutes to insert two intravenous lines, one into each arm. Within four minutes of the lines being inserted, he was pronounced dead.

Jackson was sentenced to death for the 2001 rape and murder of seamstress Ruth Phillips in her Williamsburg apartment.

Like other states, Virginia recently replaced sodium thiopental with pentobarbital after a nationwide shortage of the sedative, which is administered before two other drugs that stop the inmate’s breathing and heart. Attorneys in some states have contested the use of pentobarbital, but federal courts have ruled the change is not significant enough to stop executions. Pentobarbital has been used in two dozen executions this year, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

Richard Phillips, who found his mother dead on Aug. 26, 2001, said the execution was long overdue. Neither Phillips nor other members of the victim’s family witnessed the execution. Ruth Phillips, a widow for 30 years, followed her son to Virginia from New Hampshire in the late 1990s. She worked as a seamstress making slip covers and draperies up until her death. Richard Phillips said he had wanted her to move close to him so she would be safe. Authorities say Jackson broke into her apartment. When she awoke and found him rummaging through her purse, she offered him anything if he would leave. Instead, he put a pillow over her face and raped her, according to authorities. They said Jackson then fled in her car and used the $60 he stole from her apartment to buy marijuana.

“I’m sorry Mrs. Phillips lost her life due to something that I done,” Jackson had said recently. “I’m sorry to Mr. Philips that he hurt so much. I’m sorry that he lost his mother.”

Jackson nearly got a reprieve last year when U.S. District Judge Leonie Brinkema allowed a two-day evidentiary hearing in which Jackson’s brother and sister testified about the abuse he suffered at the hands of his father and stepfather while growing up. Brinkema ordered that Jackson at the time should receive a new sentencing hearing, saying the testimony “painted a graphic picture of an unwarranted, continuous, sadistic course of conduct that terrorized and dehumanized Jackson throughout his childhood.” But earlier this year, a federal appeals court overturned that ruling on a technicality. Recently, Jackson’s attorneys had argued jurors should get a chance to hear those graphic details of childhood abuse.

That argument was not enough to sway Gov. Bob McDonnell, who denied a request to commute Jackson’s sentence to life in prison last week. The U.S. Supreme Court denied a request earlier in the day Thursday to block the execution.

In a telephone interview with The Associated Press last Friday, Jackson talked about the abuse, which began with a broken arm when he was 19 months old and continued with sexual abuse and beatings with a fist, belt and once a two-by-four for more than a decade. Jackson acknowledged killing Phillips. Although he said it wasn’t an excuse for what he did, Jackson said he didn’t think it would have happened if he could have escaped the abuse as a child. “I don’t think I would have ended up this way,” he said. “I don’t think I would be on death row.”

The Rev. Christine Payden-Travers, who has written to and visited with Jackson for several years, called him a loyal and caring friend to many people. She was with Jackson until he was taken into the death chamber. She then witnessed the execution, holding her Bible, sometimes shutting her eyes and appearing to mouth a prayer. She had called up until the final hours for Jackson’s life to be spared. Payden-Travers and Jackson’s attorney declined to comment after the execution.

Jackson had followed news reports about the use of pentobarbital, including a recent Georgia execution in which there was some evidence the inmate suffered when the drug was used. He said he was concerned about its use. Department of Corrections spokesman Larry Traylor said the execution team had trained on the amended protocol using the new drug, read to “carry out the order of execution in a professional and constitutional manner.”

"Jackson executed for 2001 slaying in Williamsburg," by Frank Green. (August 19, 2011 - 6:46 AM)

JARRATT -- Jerry Terrell Jackson was executed by injection Thursday night for the rape and murder of an 88-year-old Williamsburg woman he suffocated with a pillow and robbed of $60. Jackson, 30, was pronounced dead at 9:14 p.m., said officials at the Greensville Correctional Center where Virginia executions are carried out. Asked if he had any last words, Jackson shook his head, indicating no.

It was the first execution in Virginia using the sedative pentobarbital as the first of three drugs administered in lethal injections. Virginia and most states traditionally used another drug that is no longer available. Larry Traylor, spokesman for the Virginia Department of Corrections, said there were no complications.

Jackson was escorted into the execution chamber by execution team members at 8:53 p.m. He was quickly ushered onto the gurney and strapped in. At 8:55 p.m., curtains were closed, blocking the view of witnesses while an IV line was inserted in each of his arms. After the curtains reopened, Jackson declined to make a last statement and the first of three chemicals started flowing. His chest moved as he breathed, his right toe appeared to tap and he moved his head a bit, but the movements quickly ceased. He was pronounced dead by a doctor who was remotely monitoring his heartbeat.

Jackson was sentenced to death for the slaying of Ruth Phillips in August 2001. Jackson broke into her apartment, where she lived alone, assaulted her and fled with her automobile. Her partially clothed body was discovered by her son, Richard Phillips, who went to check on her when she failed to attend church and did not answer her phone.

Jackson's lawyers did not contest his guilt but challenged his death sentence in unsuccessful appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court and Gov. Bob McDonnell. They said Jackson's trial lawyers failed to interview and present testimony from Jackson's brother and sister about the physical, psychological and sexual abuse Jackson suffered as a child. They argued that the testimony could have persuaded at least one juror to vote for a sentence of life without parole instead of death.

The Virginia Attorney General's Office, however, countered that the jury heard a great deal of evidence about the abuse suffered by Jackson and that testimony from his brother and sister would only have been cumulative.

McDonnell turned down Jackson's request for clemency last week, and the U.S. Supreme Court rejected his appeal Thursday afternoon.

Traylor said Jackson spent his last day in part by visiting with family members. No surviving family members of Ruth Phillips witnessed the execution. Jackson's was the 109th execution carried out in Virginia since the U.S. Supreme Court allowed the death penalty to resume in 1976. His death leaves Virginia's death-row population at 10.

On Sunday, August 26, 2001, 88–year–old Ruth Phillips did not show up to church. Concerned by her absence, Mrs. Phillips's son tried reaching her by telephone. When there was no answer, he went to her Williamsburg, Virginia, apartment to check on her. After letting himself in, he found his mother's body “lying ‘twisted and exposed’ on a bed in her bedroom.” As he later described it, her “leg was twisted around, and her pubic region was exposed; her breast was exposed; and her nightgown was up around her neck.” Mrs. Phillips's autopsy showed that she had died of asphyxia, which “occurs when the brain is without a supply of oxygen for four to six minutes.” The autopsy also found a bruise on her nose and lacerations on the exterior and interior of her vagina.

A crime scene investigator recovered a hair from Mrs. Phillips's chest and another from the bed underneath her stomach; more hairs were found in the vicinity of her left thigh. Forensic analysis revealed that several of the hairs were pubic hair that was inconsistent with samples taken from Mrs. Phillips. These hairs were later found “to be consistent with Jerry Jackson's DNA to the exclusion of 99.998% of the population with a 95% degree of confidence.”

In December 2001, investigators conducted a videotaped interview with Jackson. After waiving his Miranda rights, he “admitted entering Mrs. Phillips' apartment, searching through and taking money out of her purse.” Jackson claimed he did not know Mrs. Phillips was home when he flipped on the light and began to sift through her purse. As a result, he was “scared” when Mrs. Phillips, who had been lying in bed, exclaimed: “What do you want? I'll give you whatever, just get out.” Jackson acknowledged that when he realized Mrs. Phillips had seen him, “he held a pillow over her face for two or three minutes and tried to make her ‘pass out’ so she could not identify him” and further “admitted that he inserted his penis into her vagina while he was holding the pillow over her face.” Jackson added that after exiting through a back window, he drove away in Mrs. Phillips's car, which he ultimately abandoned. He also reported that he used the sixty dollars he stole from Mrs. Phillips's purse to buy marijuana. Jackson repeatedly insisted that he had not intended to kill Mrs. Phillips.

A Virginia grand jury indicted Jackson in March 2002 and charged him, inter alia, with two counts of capital murder for the premeditated killing of Phillips in the commission of rape or attempted rape and in the commission of robbery or attempted robbery. Jackson's trial was bifurcated into a guilt and a penalty phase. During the guilt phase, Jackson retreated from his earlier statement to law enforcement, testifying that he had confessed to investigators because he believed “that was what [they] wanted to hear” and that an accomplice had in fact smothered Phillips. Jackson further “denied having any knowledge about who raped Mrs. Phillips or about how his pubic hairs got on her body.”

The jury found Jackson guilty of both capital counts and of various other state crimes. Following penalty-phase proceedings—which we discuss in greater detail below—the jury found a “probability that [Jackson] would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society” and recommended a death sentence on both capital counts. In April 2003 the state circuit court accepted the jury's recommendation and imposed a death sentence.

"Virginia executes man who raped, killed elderly woman," by Matthew Ward. (Thu, Aug 18 2011)

CHESAPEAKE, Va (Reuters) - A man convicted of raping and killing an elderly Virginia woman was executed by lethal injection on Thursday, the first inmate put to death in that state this year, the attorney general's office said. Jerry Terrell Jackson, 30, was executed at the Greensville Correctional Center, south of the state capital, Richmond. "Tonight, the death sentence of Jerry Jackson was carried out by the Commonwealth of Virginia for the brutal rape and murder of Ruth Phillips," Virginia's Attorney General Ken Cuccinelli said in a statement.

Jackson, on death row since 2003, entered the Williamsburg apartment of 88-year-old Phillips on August 26, 2001. He told police he did not know Phillips was home. But she was lying in bed at the time and confronted Jackson. She told him to take what he wanted and leave, but he held a pillow against her face until she stopped screaming, raping her at the same time.

Jackson was pronounced dead at 9:14 p.m., Corrections spokesman Larry Traylor said. Jackson was the first inmate to be put to death in Virginia this year, and the first ever in that state to be executed with a drug mixture that included pentobarbital, a sedative. Jackson was the 32nd person executed in the United States this year.

After killing Phillips, Jackson left the apartment through a back window with $60. He stole Phillips' car and used the money to purchase marijuana. Phillips' body was found by her son after she did not attend church or answer her telephone. A fingerprint on a piece of paper inside a wallet next to Phillips' bed and DNA from hair found on and around her body implicated Jackson, and a jury found him guilty of capital murder.

Jackson met with family members, his spiritual advisor and attorneys today, Traylor said, and the inmate requested a last meal but asked for details to remain private. Jackson made no final statement, he added.

Traylor said there were no complications with the execution. Virginia, like other states, switched to using pentobarbital instead of sodium thiopental in its lethal injection regime after the sole U.S. supplier of sodium thiopental recently ceased production. The Supreme Court earlier on Thursday denied an appeal to stay the execution.

Virginians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty

Name: Jerry Jackson DOB: 7-22-81 Race: B Venue: Williamsburg Crime: Murder, Rape, Robbery Inmate Number: 319080 Date Entered: 4-3-03

1 Frank Coppola August 10, 1982 electric chair Muriel Hatchell

2 Linwood Earl Briley October 12, 1984 electric chair John Gallaher

3 James Dyral Briley April 18, 1985 electric chair Judy Barton and Harvey Barton

4 Morris Mason June 25, 1985 electric chair Margaret Hand

5 Michael Marnell Smith July 31, 1986 electric chair Audrey Jean Weiler

6 Richard Lee Whitlley] July 6, 1987 electric chair Phoebe Parsons

7 Earl Clanton, Jr.[2][3] April 14, 1988 electric chair Wilhemina Smith

8 Alton Waye[4][5] August 30, 1989 electric chair Laverne Marshall

9 Richard T. Boggs[6][7] July 19, 1990 electric chair Treeby Shaw

10 Wilbert Lee Evans[8] October 17, 1990 electric chair sheriff deputy William Truesdale

11 Buddy Earl Justus[9] December 13, 1990[1] electric chair Ida Mae Moses

12 Albert Jay Clozza[10][11] July 24, 1991[2] electric chair Patricia Ann Bolton

13 Derick Lynn Peterson August 22, 1991 electric chair Howard Kauffman

14 Roger Keith Coleman[12] May 20, 1992 electric chair Wanda Fay McCoy

15 Edward B. Fitzgerald, Sr.[13][14] July 23, 1992 electric chair Patricia Cubbage

16 Willie Leroy Jones[15] September 11, 1992 electric chair Graham Adkins and Myra Adkins

17 Timothy Dale Bunch[16] December 10, 1992 electric chair Su Cha Thomas

18 Charles Sylvester Stamper[17][18][19] January 19, 1993 electric chair Franklin Cooley, Agnes Hicks, and Stephen Staples

19 Syvasky L. Poyner[20][21] March 18, 1993 electric chair Joyce Baldwin, Louise Paulett, Chestine Brooks, Vicki Ripple, and Carolyn Hedrick

20 Andrew J. Chabrol[22][23] June 17, 1993 electric chair Lisa Harrington

21 Joe Louis Wise, Sr.[24] September 14, 1993 electric chair William Ricketson

22 David Mark Pruett[25][26] December 16, 1993 electric chair Wilma Harvey and Debra McInnis

23 Johnny Watkins, Jr.[27] March 3, 1994 electric chair Betty Barker and Carl Buchanan

24 Timothy Wilson Spencer[28] April 27, 1994 electric chair Susan Tucker, Debbie Davis, Susan Hellams, and Diane Cho

25 Dana Ray Edmonds January 24, 1995 lethal injection John Elliot

26 Willie Lloyd Turner May 26, 1995 lethal injection W. Jack Smith, Jr.

27 Dennis Wayne Stockton September 27, 1995 lethal injection Kenneth Arnde and Ronnie Lee Tate

28 Mickey Wayne Davidson October 19, 1995 lethal injection Doris Davidson, Mamie Clatterbuck, and Tammy Clatterbuck

29 Herman Charles Barnes November 13, 1995 lethal injection Clyde Jenkins and Mohammed Afifi

30 Walter Milton Correll, Jr.[29] January 4, 1996 lethal injection Charles W. Bousman, Jr.

31 Richard Townes, Jr.[30] January 23, 1996 lethal injection Virginia Goebel

32 Joseph John Savino III[31] July 17, 1996 lethal injection Thomas McWalters

33 Ronald B. Bennett[32] November 21, 1996 lethal injection Anne Keller Vaden

34 Gregory Warren Beaver December 4, 1996 lethal injection state trooper Leo Whitt

35 Larry Allen Stout December 10, 1996 lethal injection Jacqueline Kooshian

36 Lem Davis Tuggle, Jr. December 12, 1996 lethal injection Jessie Geneva Havens

37 Ronald Lee Hoke December 16, 1996 lethal injection Virginia Stell

38 Michael Carl George February 6, 1997 lethal injection Alexander Sztanko

39 Coleman Wayne Gray February 26, 1997 lethal injection Richard McClelland

40 Roy Bruce Smith July 17, 1997 lethal injection Manassas police officer John Conner

41 Joseph Roger O'Dell III July 23, 1997 lethal injection Helen Schartner

42 Carlton Jerome Pope August 19, 1997 lethal injection Cynthia Gray

43 Mario Benjamin Murphy September 17, 1997 lethal injection James Radcliff

44 Dawud Majid Mu'Min November 13, 1997 lethal injection Gladys Nopwasky

45 Michael Charles Satcher December 9, 1997 lethal injection Ann Borghesani

46 Thomas H. Beavers, Jr. December 11, 1997 lethal injection Marguerite Lowery

47 Tony Albert Mackall February 10, 1998 lethal injection Mary Elizabeth Dahn

48 Douglas McArthur Buchanan, Jr. March 18, 1998 lethal injection Douglas Buchanan, Sr., Donald Buchanan, J.J. Buchanan, and Geraldine Buchanan

49 Ronald L. Watkins March 25, 1998 lethal injection William McCauley

50 Angel Francisco Breard[33] April 14, 1998 lethal injection Ruth Dickie

51 Dennis Wayne Eaton June 18, 1998 lethal injection state trooper Jerry Hines, Walter Custer, Jr., Ripley Marston, Sr., and Judith MacDonald

52 Danny Lee King July 23, 1998 lethal injection Carolyn Rogers

53 Lance Antonio Chandler, Jr. August 20, 1998 lethal injection Billy Dix

54 Johnile L. DuBois August 31, 1998 lethal injection Philip Council

55 Kenneth Manual Stewart, Jr. September 23, 1998 electric chair Cynthia Stewart and Jonathan Stewart

56 Dwayne Allen Wright October 14, 1998 lethal injection Saba Tekle

57 Ronald Lee Fitzgerald October 21, 1998 lethal injection Coy H. White and Hugh Morrison

58 Kenneth Wilson November 17, 1998 lethal injection Jacqueline Stephens

59 Kevin Wayne Cardwell December 3, 1998 lethal injection Anthony Brown

60 Mark Arlo Sheppard January 20, 1999 lethal injection Richard Rosenbluth and Rebecca Rosenbluth

61 Tony Leslie Fry February 4, 1999 lethal injection Leland A. Jacobs

62 George Adrian Quesinberry, Jr.[34] March 9, 1999 lethal injection Thomas L. Haynes

63 David Lee Fisher March 25, 1999 lethal injection David William Wilkey

64 Carl Hamilton Chichester April 13, 1999 lethal injection Timothy Rigney

65 Arthur Ray Jenkins III April 20, 1999 lethal injection Floyd Jenkins and Lee H. Brinklow

66 Eric Christopher Payne April 28, 1999 lethal injection Ruth Parham and Sally Fazio

67 Ronald Dale Yeatts April 29, 1999 lethal injection Ruby Meeks Dodson

68 Tommy David Strickler July 21, 1999 lethal injection Leann Whitlock

69 Marlon DeWayne Williams August 17, 1999 lethal injection Helen Bedsole

70 Everett Lee Mueller September 16, 1999 lethal injection Charity Powers

71 Jason Matthew Joseph October 19, 1999 lethal injection Jeffrey Anderson

72 Thomas Lee Royal, Jr. November 9, 1999 lethal injection Hampton police officer Kenny Wallace

73 Andre L. Graham December 9, 1999 lethal injection Sheryl Stack, Richard Rosenbluth, and Rebecca Rosenbluth

74 Douglas Christopher Thomas January 10, 2000 lethal injection James Baxter Wiseman and Kathy J. Wiseman

75 Steve Edward Roach January 13, 2000 lethal injection Mary Ann Hughes

76 Lonnie Weeks, Jr. March 16, 2000 lethal injection state trooper Jose M. Cavazos

77 Michael David Clagett July 6, 2000 electric chair Lam Van Son, Wendell G. Parish, Jr., Karen Sue Rounds, and Abdelaziz Gren

78 Russell William Burket August 30, 2000 lethal injection Katherine Tafelski and Ashley Tafelski

79 Derek Rocco Barnabei September 14, 2000 lethal injection Sarah Wisnosky

80 Bobby Lee Ramdass October 10, 2000 lethal injection Mohammed Kayani

81 Christopher Cornelius Goins December 6, 2000 lethal injection Robert Jones, Nicole Jones, David Jones, Daphne Jones, and James Randolph

82 Thomas Wayne Akers March 1, 2001 lethal injection Wesley Brant Smith

83 Christopher James Beck October 18, 2001 lethal injection Florence Marie Marks, David Kaplan, and William Miller

84 James Earl Patterson March 13, 2002 lethal injection Joyce Snead Aldridge

85 Daniel Lee Zirkle April 2, 2002 lethal injection Christina Zirkle and Jessica Shiflett

86 Walter Mickens, Jr. June 12, 2002 lethal injection Timothy Jason Hall

87 Mir Aimal Kasi November 14, 2002 lethal injection Frank Darling and Lansing Bennett

88 Earl Conrad Bramblett April 9, 2003 electric chair Blaine Hodges, Teresa Hodges, Winter Hodges, and Anah Hodges

89 Bobby Wayne Swisher July 22, 2003 lethal injection Dawn McNees Snyder

90 Brian Lee Cherrix March 18, 2004 lethal injection Tessa Van Hart

91 Dennis Mitchell Orbe March 31, 2004 lethal injection Richard Burnett

92 Mark Wesley Bailey July 22, 2004 lethal injection Katherine Bailey and Nathan Bailey

93 James Bryant Hudson August 18, 2004 lethal injection Stanley Cole, Walter Cole, and Patsy Cole

94 James Edward Reid September 9, 2004 lethal injection Annie Mae Lester

95 Dexter Lee Vinson April 27, 2006 lethal injection Angela Felton

96 Brandon Wayne Hedrick July 20, 2006 electric chair Lisa Yvonne Crider

97 Michael William Lenz July 27, 2006 lethal injection inmate Brent H. Parker

98 John Yancey Schmitt November 9, 2006 lethal injection Earl Shelton Dunning

99 Kevin Green May 27, 2008 lethal injection Patricia L. Vaughan

100 Robert Yarbrough June 25, 2008 lethal injection Cyril Hugh Hamby

101 Kent Jermaine Jackson July 10, 2008 lethal injection Beulah Mae Kaiser

102 Christopher Scott Emmett July 24, 2008 lethal injection John Fenton Langley

103 Edward Nathaniel Bell February 19, 2009 lethal injection Winchester police officer Ricky Timbrook

104 John Allen Muhammad November 10, 2009[3] lethal injection Dean Harold Meyers

105 Larry Bill Elliott November 17, 2009 electric chair Dana Thrall and Robert Finch

106 Paul Warner Powell March 18, 2010 electric chair Stacie Reed

107 Darick Walker May 20, 2010 lethal injection Stanley Beale and Clarence Elwood Threat

108 Teresa Lewis September 23, 2010 lethal injection Julian Clifton Lewis and Charles J. Lewis

109 Jerry Terrell Jackson August 18, 2011 lethal injection Ruth Phillips

Jackson v. Commonwealth, 267 Va. 178, 590 S.E.2d 520 (Va. 2004) (Direct Appeal).

Background: Defendant was convicted in a jury trial in the Circuit Court, James City County, Samuel Taylor Powell, III, J., of murder, rape, burglary, robbery, and petit larceny, and sentenced to death. Defendant appealed.

Holdings: The Supreme Court, Cynthia D. Kinser, J., held that: (1) defendant's confession to police was admissible; (2) prospective juror, who stated that defendant would have to present some evidence, was not required to be struck; (3) prospective juror, who stated in response to confusing questions that he would automatically impose the death penalty, was not required to be struck; (4) prospective juror, who initially stated that she would not be able to consider all mitigating factors in deciding to impose death, was not required to be struck; (5) defendant was not prejudiced by alleged juror misconduct in speaking about case to one another prior to close of evidence; (6) trial court did not abuse discretion in allowing jury to read transcript of video taped confession; (7) photographs of victim's face and vaginal area were admissible; (8) evidence was sufficient to support jury's finding of premeditation; and (9) death sentence was not excessive. Affirmed.

OPINION BY JUSTICE CYNTHIA D. KINSER.

A jury convicted Jerry Terrell Jackson of two counts of capital murder for the premeditated killing of Ruth W. Phillips in the commission of rape or attempted rape, and in the commission of robbery or attempted robbery in violation of Code §§ 18.2–31(5) and –31(4), respectively. The jury also convicted Jackson of statutory burglary, in violation of Code § 18.2–90; robbery, in violation of Code § 18.2–58; rape, in violation of Code § 18.2–61; and petit larceny, in violation of Code § 18.9–96. At the conclusion of the penalty phase of a bifurcated trial, the jury fixed Jackson's punishment at death on each of the capital murder convictions, finding “that there is probability that he would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing serious threat to society.” The jury also fixed punishment of two life sentences for the rape and the robbery convictions, a 20–year sentence for the burglary conviction, and a 12–month sentence for the petit larceny conviction. The circuit court sentenced Jackson in accordance with the jury's verdict.FN1 FN1. The circuit court also imposed fines in the total amount of $102,500 as fixed by the jury.

Jackson appealed his non-capital convictions to the Court of Appeals pursuant to Code § 17.1–406(A). We certified that appeal (Record No. 031518) to this Court under the provisions of Code § 17.1–409 for consolidation with the defendant's appeal of his capital murder convictions (Record No. 031517) and the sentence review mandated by Code § 17.1–313. After considering Jackson's assignments of error and conducting our sentence review, we find no error in the circuit court's judgments and will affirm Jackson's convictions and the imposition of the death penalty.

I. FACTS

A. GUILT PHASE

Around 7 p.m., on Sunday, August 26, 2001, Richard Phillips discovered the body of his 88–year–old mother, Ruth Phillips, lying “twisted and exposed” on a bed in her bedroom. Phillips explained that his mother's “leg was twisted around, and her pubic region was exposed[; h]er breast was exposed[; and h]er nightgown was up around her neck.” Mrs. Phillips lived alone in an apartment located in Williamsburg, and her son had become concerned about her well-being that day because she had not attended church and was not answering her telephone. After finding his mother's body, Phillips went outside and used a cellular telephone to call the “911” emergency number. While waiting for emergency personnel to arrive, he noticed that the screen on a bathroom window in the apartment had been removed.

A subsequent autopsy of Mrs. Phillips' body revealed a contusion on her nose and some hemorrhaging of minute blood vessels in her cheeks and eyes. There were also two lacerations to her vagina, one on the exterior area and the other one on the interior area. The medical examiner who performed the autopsy opined that the cause of death was asphyxia. Death by asphyxia, according to the medical examiner, occurs when the brain is without a supply of oxygen for four to six minutes although unconsciousness may come about within 15 to 30 seconds. An investigator with the James City County Police Department, Jeff Vellines, went to Mrs. Phillips' apartment and collected several items of physical evidence. He found a window screen, mirror case, and cosmetic items outside the apartment near the master bathroom window. Inside, Vellines discovered a black pocketbook lying on the floor next to Mrs. Phillips' bed, and a brown wallet underneath the pocketbook. The wallet did not contain any money. However, a white square piece of paper found in the wallet contained one latent fingerprint of value for identification purposes. That fingerprint was later compared with the fingerprints of the defendant and found to be “one and the same.”

Another investigator at the crime scene recovered a hair from Mrs. Phillips chest area and another hair on the bed below the stomach area. During the autopsy of Mrs. Phillips' body, additional hairs were collected from her left thigh area. Microscopic examination of those hairs by a forensic scientist revealed that one of the hairs recovered from Mrs. Phillips' thigh area and the other two hairs were pubic hairs, but they were not consistent with samples of Mrs. Phillips' pubic hair. These same three hairs along with samples of the defendant's blood and hair were later subjected to mitochondrial DNA analysis. According to the forensic scientist who performed the testing, Jackson could not be excluded as the source of the hairs found on Mrs. Phillips' body and bed. The “mtDNA sequence data” of each of those hairs matched the “corresponding mtDNA sequence of the blood” taken from the defendant.

In December 2001, Vellines and Eric Peterson, also an investigator with the James City County Police Department, interviewed Jackson in the James City County Law Enforcement Center. After waiving his Miranda rights, Jackson admitted entering Mrs. Phillips' apartment, searching through and taking money out of her purse, and then exiting through a back window. Jackson stated that he did not know that Mrs. Phillips was at home, and that, when he turned on the light and was going through her purse, Mrs. Phillips, who was lying in bed, confronted him and stated, “What do you want? I'll give you whatever, just get out.” In the defendant's words, “[I]t just scared me and I covered her up [.]” Jackson acknowledged that he held a pillow over her face for two or three minutes and tried to make her “pass out” so she could not identify him. Jackson stated that, when Mrs. Phillips stopped screaming, that was his “cue that she [had] passed out.” He also admitted that he inserted his penis into her vagina while he was holding the pillow over her face. Continuing, Jackson stated that he took Mrs. Phillips' automobile when he left her apartment and drove it to another apartment complex, where he abandoned the vehicle with the keys lying on top of it. He also used $60 that he had taken from her purse to purchase marijuana. Throughout the interview, Jackson denied that anyone else was with him during this incident and insisted that he did not mean to kill Mrs. Phillips.

At trial, Jackson testified to a different version of the events that supposedly transpired at Mrs. Phillips' apartment.FN2 The defendant claimed that, on the day in question, he had been playing basketball until around midnight at the apartment complex where Mrs. Phillips lived. Jackson stated that, as he was leaving, he came in contact with Alex Meekins and Jasper Meekins. Jackson decided to participate in their plan to break into Mrs. Phillips' apartment. According to Jackson, Alex entered the apartment through a window and then let Jasper and the defendant in through the front door. While Jackson was looking through Mrs. Phillips' purse, she woke up and asked what was going on. Jackson testified that the following events then took place in Mrs. Phillips' bedroom: FN2. Jackson also testified at a hearing on a motion to suppress his confession. His testimony at that hearing also differed from his statement to the police.

Jasper Meekins, he put the pillow over her face and smothered her. While he was smothering her, I think she was struggling, but I told him at the end when I heard some sound, she was gurgling, I told him to stop. I pushed him off. As we were leaving, I pulled her nightgown down. I put the blanket over her, and I picked the pillow up initially and I didn't like what I saw, so I put the pillow back. Jackson explained that he confessed to Peterson because he thought that was what Peterson wanted to hear, and because he just wanted to “get out of there as fast as [he] could.” Jackson also explained that he never told the investigators about Jasper's and Alex's participation in the crime because he was “scared for [his] family on the streets” and had concerns about being a “snitch.” At trial, Jackson denied raping or killing Mrs. Phillips. He also denied having any knowledge about who raped Mrs. Phillips or about how his pubic hairs got on her body.FN3 FN3. A mitochondrial DNA analysis of blood taken from Alex Meekins showed that his mtDNA sequence did not correspond to the mtDNA sequence of the three hairs recovered from Mrs. Phillips' body.

B. SENTENCING PHASE

During the sentencing phase of the bifurcated trial, the Commonwealth introduced into evidence 18 orders showing Jackson's convictions or adjudications of delinquency for such offenses as grand larceny, petit larceny, trespassing, drug possession, receiving stolen property, contempt of court, identity fraud, statutory burglary, credit card theft, and obtaining money under false pretenses. The jury also heard evidence from two correctional officers about two incidents involving the defendant while he was incarcerated. In the first incident, Jackson refused to obey the orders of a correctional officer, and that refusal led to a scuffle with several officers as they attempted to remove Jackson's hand cuffs. The other incident involved an altercation between the defendant and another inmate.

In mitigation of the offenses, Jackson presented evidence about his adjustment and behavioral problems when he was a youth. In 1993, he was diagnosed with an “adjustment disorder with depressed mood and attention deficit, hyperactivity disorder.” Jackson was evaluated again in 1996 because he was having behavioral problems at home and was not doing well in school. Jackson expressed resentment toward his stepfather and acted out his negative feelings by behaving aggressively. However, testing indicated that Jackson had average intellectual functioning. During his school years, Jackson took medication for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, but his mother reported to Jackson's pediatrician that her son continued to have behavioral problems at school, including fights. The defendant was eventually placed in a special school for students who cannot be controlled in a regular classroom setting. There was also evidence that the defendant suffered physical abuse as a child. FN4 FN4. We will summarize additional facts and proceedings as necessary to address specific issues.

II. ANALYSIS

A. DISMISSAL OF INDICTMENTS

Jackson assigns error to the circuit court's refusal to dismiss the capital murder indictments on the basis that Code § 19.2–264.4(B) is unconstitutional. The defendant raised this claim in a pre-trial motion and supporting memorandum. The circuit court denied the motion. Jackson now argues that Code § 19.2–264.4(B) contains “a relaxed evidentiary standard that leads to inherently unreliable determinations of aggravating factors and unreliable death sentences.” Citing the decisions in Ring v. Arizona, 536 U.S. 584, 122 S.Ct. 2428, 153 L.Ed.2d 556 (2002), Apprendi v. New Jersey, 530 U.S. 466, 120 S.Ct. 2348, 147 L.Ed.2d 435 (2000), and In re Winship, 397 U.S. 358, 90 S.Ct. 1068, 25 L.Ed.2d 368 (1970), Jackson also seems to suggest that, in Virginia, the aggravating factors of future dangerousness and vileness are not decided by a jury based on proof of those factors beyond a reasonable doubt.FN5 We find no merit in the defendant's arguments. FN5. Any argument about the vileness aggravating factor is irrelevant because Jackson's sentence of death was predicated on the jury's finding of future dangerousness.

First, before the sentence of death may be imposed, the Commonwealth must prove at least one of the statutory aggravating factors beyond a reasonable doubt. Code § 19.2–264.4(C). Pursuant to Code § 19.2–264.3, a jury makes that determination, unless a jury trial is waived. Code § 19.2–257. Thus, to the extent Jackson suggests otherwise, he is incorrect. [1] [2] Next, Code § 19.2–264.4(B) does not contain a relaxed evidentiary standard or produce unreliable determinations of aggravating factors. Evidence relevant to sentencing in the penalty phase of a capital murder trial is admissible, “subject to the rules of evidence governing admissibility.” Id. We have held that this statute does not permit admission of irrelevant evidence. See Powell v. Commonwealth, 267 Va. 107, 121, 590 S.E.2d 537, 546 (2004) (decided this day); Remington v. Commonwealth, 262 Va. 333, 357, 551 S.E.2d 620, 634–35 (2001). Presentence reports from probation officers are specifically not admissible. Id. And, in Virginia, hearsay evidence also is not admissible during a penalty phase proceeding. Lovitt v. Warden, 266 Va. 216, 259, 585 S.E.2d 801, 826 (2003).

Finally, we note that, although the defendant argues that the full procedural safeguards employed during the guilt phase of a capital murder trial must also be provided in the penalty phase, he never identifies what procedural safeguards were missing in his penalty phase proceeding. He also fails to enunciate what unreliable information was admitted into evidence during the penalty phase of his trial as a result of the supposed relaxed evidentiary standard. In other words, Jackson's complaints about the provisions of Code § 19.2–264.4(B) are merely hypothetical in nature. Thus, we conclude that the circuit court did not err in refusing to dismiss the indictments.

B. SUPPRESSION OF DEFENDANT'S STATEMENT

Jackson filed a pre-trial motion to suppress the statement that he made to the police investigators. After hearing evidence and argument of counsel, the circuit court denied the motion, finding that Jackson's statement was voluntary and not the product of any psychological or physical coercion.

The defendant assigns error to the court's decision and argues that, “[b]ased on the totality of the circumstances, [his] will was overcome, his capacity for self-determination was critically impaired and his confession was not the product of a free and unconstrained choice.” Jackson claims that the investigators who questioned him engaged in trickery and deceit because of statements such as, “I will work with you ... I will be with you, thick and thin, boy ... I will be in your corner” and “I'm here for you.” As further evidence that his will was overborne, Jackson points to his repeated denials of culpability during the first part of the interrogation, his initial confession to a different crime, and his lack of knowledge that the crime for which he was being interrogated carried a possible sentence of death. In accordance with his testimony at the suppression hearing, Jackson claims that he simply told the investigator what the investigator wanted to hear so that he, the defendant, would be free to go.

We find no merit in Jackson's arguments. The circuit court found, and we agree, that there was no evidence of any promises of leniency, any force, any threats, any intimidation, any coercion, or any deprivation of the defendant's physical or mental needs. Such “subsidiary factual determinations are entitled to a presumption of correctness.” Swann v. Commonwealth, 247 Va. 222, 231, 441 S.E.2d 195, 202 (1994). The court also noted that the defendant had a reported IQ score of 100 and an educational level sufficient to read and write. Furthermore, Jackson signed a waiver of his Miranda rights at the beginning of the interview. And, he obviously understood the implications of making statements to the police because he had been charged with crimes on two previous occasions after confessing to those crimes.

A defendant's waiver of Miranda rights is valid if made knowingly, voluntarily, and intelligently. Id.; Jenkins v. Commonwealth, 244 Va. 445, 453, 423 S.E.2d 360, 366 (1992). “The test for voluntariness is whether the statement is the ‘product of an essentially free and unconstrained choice by its maker,’ or whether the maker's will ‘has been overborne and his capacity for self-determination critically impaired.’ ” Id. at 453–54, 423 S.E.2d at 366 (quoting Culombe v. Connecticut, 367 U.S. 568, 602, 81 S.Ct. 1860, 6 L.Ed.2d 1037 (1961)). When determining whether a defendant's statement was voluntarily given, we examine the totality of the circumstances, which include the defendant's background and experience as well as the conduct of the police in obtaining the waiver of Miranda rights and confession. Swann, 247 Va. at 231, 441 S.E.2d at 202; Correll v. Commonwealth, 232 Va. 454, 464, 352 S.E.2d 352, 357 (1987). Using these principles, we conclude that the defendant's statement was made knowingly, intelligently, and voluntarily. Thus, the circuit court did not err in admitting Jackson's incriminating statement.

C. JURY SELECTION

The defendant assigns error to the circuit court's failure to strike three prospective jurors for cause. An accused has a constitutional right to be tried by an impartial jury. See U.S. Const. amends. VI and XIV; Va. Const. art. I, § 8. By statute, a trial court is required to excuse any prospective juror who cannot “stand indifferent in the cause.” Code § 8.01–358. However, [b]ecause the trial judge has the opportunity, which we lack, to observe and evaluate the apparent sincerity, conscientiousness, intelligence, and demeanor of prospective jurors first hand, the trial court's exercise of judicial discretion in deciding challenges for cause will be not disturbed on appeal, unless manifest error appears in the record. Pope v. Commonwealth, 234 Va. 114, 123–24, 360 S.E.2d 352, 358 (1987) (citing Calhoun v. Commonwealth, 226 Va. 256, 258–59, 307 S.E.2d 896, 898 (1983)); accord Bell v. Commonwealth, 264 Va. 172, 191, 563 S.E.2d 695, 709 (2002); Green v. Commonwealth, 262 Va. 105, 115–16, 546 S.E.2d 446, 451 (2001); Stewart v. Commonwealth, 245 Va. 222, 234, 427 S.E.2d 394, 402 (1993). Thus, on appellate review, we defer to the trial court's decision whether to retain or exclude prospective jurors. Vinson v. Commonwealth, 258 Va. 459, 467, 522 S.E.2d 170, 176 (1999). Guided by these principles, we will now review the voir dire of the three jurors that the defendant claims should have been struck for cause. In doing so, we consider the prospective juror's entire voir dire, not just isolated portions. Id.; Mackall v. Commonwealth, 236 Va. 240, 252, 372 S.E.2d 759, 767 (1988).

(1) Juror Reinsberg - The defendant moved the circuit court to excuse this prospective juror because, among other reasons, she indicated at one point during her voir dire that she would probably require the defense to put on evidence during the trial. However, her overall responses to voir dire questions relevant to this particular issue reveal that she could “stand indifferent to the cause” and would not require the defendant to present evidence to establish his innocence:

[DEFENSE COUNSEL]: Do you have any feelings about the case from what you have read in the Gazette or from what you may have read in the Daily Press earlier? MS. REINSBERG: The seriousness of it. [DEFENSE COUNSEL]: Other than the seriousness? MS. REINSBERG: The charges. [DEFENSE COUNSEL]: Would you require the defense to put on evidence to change your mind or influence your decision considering what you have read? MS. REINSBERG: Probably. THE COURT: Let me ask, what do you mean by that? MS. REINSBERG: From what we have read, I don't know, I was thinking the newspaper— THE COURT: Is accurate? MS. REINSBERG: Is accurate, so I would—I would want to know, it was accurate or inaccurate. Sometimes certain parts can be made up. That shouldn't be. [DEFENSE COUNSEL]: May I go on? Considering that response, have you formed an opinion of some sort as to the guilt or innocence of the Defendant if you are going to require us to put on evidence? MS. REINSBERG: No. [DEFENSE COUNSEL]: That's based on what you have seen or read? MS. REINSBERG: (Nods head.) Just the one article. [DEFENSE COUNSEL]: Have you formed an opinion on what you have heard, the facts of what you have read, have you formed an opinion as to what punishment Mr. Jackson should receive as a result of what you— MS. REINSBERG: No. [DEFENSE COUNSEL]: You said that you would probably require us to put on some evidence. Tell us what you would be looking for from the defense. MS. REINSBERG: Well, were there other people involved, for one. * * * [COMMONWEALTH'S ATTORNEY]: Judge, just a couple [of] follow-up questions if I may. Ms. Reinsberg, one of the questions [defense counsel] asked you involved a response in which you said you would want to hear if other people were involved. Understanding that you read the newspaper, correct? MS. REINSBERG: Right. [COMMONWEALTH'S ATTORNEY]: That was Saturday's Gazette? MS. REINSBERG: Right. [COMMONWEALTH'S ATTORNEY]: Are you willing to put aside any opinions or thoughts you have regarding that newspaper article and judge this case based on the facts presented during the course of the trial? MS. REINSBERG: Definitely. [COMMONWEALTH'S ATTORNEY]: And are you going to hold the Commonwealth; that is, myself and Mr. McGinty, in our case to the proper burden of we have to prove the case beyond a reasonable doubt? MS. REINSBERG: Uh-huh. [COMMONWEALTH'S ATTORNEY]: And you understand that at sentencing, if the jury has convicted the Defendant of capital murder, that the burden is on us to prove certain things beyond a reasonable doubt— MS. REINSBERG: Right. [COMMONWEALTH'S ATTORNEY]:—before you can impose the death penalty? MS. REINSBERG: Right, I understand. [COMMONWEALTH'S ATTORNEY]: Are you open-minded to both the death penalty and life in prison? MS. REINSBERG: Definitely. [COMMONWEALTH'S ATTORNEY]: Do you agree with the concept that the Defendant does not have to present any evidence at trial? MS. REINSBERG: Right. [COMMONWEALTH'S ATTORNEY]: In fact, the Defendant doesn't have to present any evidence at sentencing? MS. REINSBERG: Right. [COMMONWEALTH'S ATTORNEY]: Are you willing to follow that principle of law? MS. REINSBERG: Yes.

The voir dire of prospective juror Reinsburg demonstrates that the circuit court correctly concluded that this juror understood both the Commonwealth's burden of proof and the fact that the defendant did not have to present any evidence. As we have previously stated, “[t]he real test is whether jurors can disabuse their minds of their natural curiosity and decide the case on the evidence submitted and the law as propounded in the court's instructions.” Townes v. Commonwealth, 234 Va. 307, 329, 362 S.E.2d 650, 662 (1987); accord Eaton v. Commonwealth, 240 Va. 236, 247, 397 S.E.2d 385, 392 (1990). Prospective juror Reinsberg satisfied this test. Thus, we find no manifest error in the circuit court's decision refusing to strike this juror for cause.

(2) Juror Baffer - Relying on the following series of questions, Jackson claims that the circuit court erred in refusing to strike prospective juror Baffer for cause:

[DEFENSE ATTORNEY]: Do you hold the belief that death is the appropriate punishment for a person who commits a murder, rape and/or robbery unless he can convince you otherwise? MR. BAFFER: Yes. [DEFENSE ATTORNEY]: Why is that? MR. BAFFER: Because I believe in the State of Virginia, the Penal Code in the—it's prescribed. * * * [DEFENSE ATTORNEY]: You were asked an “automatic” question by the Commonwealth. Would you automatically vote to impose the death penalty on a person you determine beyond a reasonable doubt constituted a continuing serious threat to society? MR. BAFFER: Yes. This isolated portion of juror Baffer's voir dire is misleading because this prospective juror, when asked by the Commonwealth whether he would automatically impose the death penalty if the defendant were found guilty of capital murder, answered “No.” The circuit court then engaged in the following exchange with prospective juror Baffer: THE COURT: Mr. Baffer, let me ask you one question. [Defense counsel] asked you a question. He said that if you found beyond a reasonable doubt that a consideration of the Defendant's history and background there is a probability that he would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing serious threat to society, he asked you if you found that, would you always vote to impose the death penalty, and you said yes. Is that your understanding of what the law in Virginia is? MR. BAFFER: I'm not sure what the law of Virginia is on that. You said automatically impose the death penalty? THE COURT: If you found—you convicted the Defendant of capital murder and then you made a second finding, go to the second phase where evidence is presented regarding the possible sentence. You have two possible sentences, life in prison or death, and the Court would instruct you that before you could impose the death penalty, you must find beyond a reasonable doubt that after consideration of the Defendant's history and background, there is a probability that he would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing serious threat to society, you made that finding, is it your understanding that you must then impose the death penalty? MR. BAFFER: I don't know that I must impose. I mean, get him out of society. Life without parole removes him from society. THE COURT: That's correct. MR. BAFFER: If he would pose a danger, that would be adequate that he doesn't come back into society. THE COURT: What would be adequate, life without parole? MR. BAFFER: That would be adequate too, life without parole. THE COURT: The question [defense counsel] asked you is if you found that this future danger existed, would you automatically vote to impose the death penalty? MR. BAFFER: No, I would say no to that, if the alternative is he got life without parole, that would be adequate. THE COURT: Well, that is your alternative. You only have two choices. If the Defendant is found guilty of capital murder, you have two choices: One is the death sentence; the other is life in prison without parole. They are your only two options, and if you were to find the Defendant guilty of capital murder, and if you found the condition of future dangerousness existed, could you consider both? MR. BAFFER: I could consider both. THE COURT: Would you automatically impose the death penalty if you found future dangerousness existed? MR. BAFFER: No, if he was removed from society.

As stated previously, we must consider this juror's entire voir dire. See Vinson, 258 Va. at 467, 522 S.E.2d at 176. Upon doing so, it is clear that, while prospective juror Baffer stated at one point, in response to confusing questions by defense counsel, that he would automatically impose the death penalty, he subsequently clarified his position and stated that he would follow the court's instructions and consider both sentencing alternatives. We have held that it is improper to ask prospective jurors speculative questions regarding whether they would automatically impose the death penalty in certain hypothetical situations without reference to a juror's ability to consider the evidence and follow the court's instructions. Schmitt v. Commonwealth, 262 Va. 127, 141, 547 S.E.2d 186, 196 (2001). Thus, we conclude that the circuit court ruled properly in seating this juror.

(3) Juror Berube - [12] Jackson moved to strike prospective juror Berube on the basis that she answered “No” to one question asking whether she would be able to consider all mitigating factors in making her decision whether to impose a life sentence without parole or the death penalty. However, the answer to this one isolated question does not accurately portray this juror's positive assertions during voir dire that she would follow the court's instructions and consider all mitigating evidence when making her sentencing decision. Furthermore, when overruling the defendant's motion to strike this juror, the circuit court noted that juror Berube had given careful thought to her answers and that she did not initially understand what mitigating factors are. Thus, we conclude that the circuit court did not err in finding that this juror would be fair and impartial.

D. JUROR MISCONDUCT

During a recess on the third day of trial, the jurors asked whether they could discuss among themselves the evidence and testimony that had already been presented. The parties and the circuit court agreed that the jurors should not do so until after the close of all the evidence and the jury's deliberations began. When the jury returned to the courtroom after the recess, the court instructed the jurors that they should deliberate and discuss the evidence only after all the evidence had been introduced. The court further admonished the jurors to keep an open mind and to refrain from deciding any issue until the case was submitted to them for their deliberations. [13] The defendant did not object to those instructions or ask for a mistrial at that time. Thus, to the extent that Jackson now argues that the court should have granted a mistrial as soon as it learned of the jury's question, which suggested, in Jackson's view, that the jury had already been discussing the case, such a claim was not preserved for appeal. See Rule 5:25. Jackson filed a post-trial motion for a new trial and/or an evidentiary hearing based on allegations that the jury had discussed his guilt or innocence prior to the close of all the evidence. In support of the motion, the defendant submitted an affidavit from alternate juror Picataggi. In the affidavit, Picataggi stated that she had “witnessed and heard discussion of this case, and its outcome, among the jurors before the close of evidence and in direct violation of the instructions of the court.”

At a hearing on Jackson's motion, defense counsel advised the court that he had contacted all the jurors after the conclusion of the trial because of his concerns about the jury's question on the third day of trial. Counsel also told the court that this alternate juror agreed to speak with him but that many of the jurors would not do so or stated that such alleged discussions among the jurors did not occur before the close of the evidence. Defense counsel asked the court to summons all the jurors to an evidentiary hearing and to question them individually about what, if any, discussions occurred before the jury retired to deliberate. The court decided to summons only alternate juror Picataggi to a hearing for the purpose of questioning her about the allegations stated in her affidavit.

At that hearing, Picataggi explained, in response to questions from the court, that she had heard three discussions, two in the jury room and one at a local restaurant where the jury had gone for lunch. She acknowledged that no third person, such as the restaurant owner or a waitress, participated in any of those discussions, either by comments to the jury or by comments from any of the jurors. Picataggi could not recall whether any discussions ensued after the jurors asked the court during a recess whether they could discuss the evidence they had already heard. Picataggi also could not remember exact words used, but she described a discussion in regard to the testimony of the detective and [the defense counsel's] questioning him in regard to the videotape and that was discussed among the jurors in that—well, they didn't particularly like the way that he was questioning the detective, but that ultimately he got to the truth or to the bottom of it.

However, she admitted that at no time did any juror come to a conclusion about Jackson's guilt or innocence. During cross-examination by the defendant, Picataggi indicated that the discussions concerned things that had happened in the courtroom and matters that had been presented there, and were not necessarily limited to comments about the lawyers' styles of questioning.

After hearing Picataggi's testimony, the circuit court denied the defendant's motion for further investigation and for a new trial. The court concluded that the jurors' comments addressed the cross-examination of investigator Peterson and defense counsel's techniques of attacking that witness's credibility. The court found “no probable misconduct and clearly no prejudice” to the defendant.

On appeal, Jackson argues that the evidence of jurors' discussions “establishes a probability of prejudice and brings into question the fairness of the trial.” The defendant also asserts that the comment that “he got to the truth or to the bottom of it” went to the issue of guilt or innocence. At a minimum, the circuit court, according to Jackson, should have conducted an evidentiary hearing at which all the jurors should have been questioned. We do not agree with the defendant's position.

In Virginia, we strictly adhere “ ‘to the general rule that the testimony of jurors should not be received to impeach their verdict, especially on the ground of their own misconduct.’ ” Jenkins, 244 Va. at 460, 423 S.E.2d at 370 (quoting Caterpillar Tractor Co. v. Hulvey, 233 Va. 77, 82, 353 S.E.2d 747, 750 (1987)). We have also generally “ ‘limited findings of prejudicial juror misconduct to activities of jurors that occur outside the jury room.’ ” Id. (quoting Caterpillar Tractor Co., 233 Va. at 83, 353 S.E.2d at 751.) For example, in Haddad v. Commonwealth, 229 Va. 325, 330–331, 329 S.E.2d 17, 20 (1985), evidence showing juror misconduct in the form of expressing an opinion to third persons during trial proceedings was sufficient to establish a probability of prejudice to the accused.

Applying this same probability of prejudice standard, we find that Jackson failed to carry his burden to establish such prejudice. See id. Upon reviewing Picataggi's affidavit, the circuit court properly convened an evidentiary hearing to investigate further her allegations of juror misconduct. See Kearns v. Hall, 197 Va. 736, 743, 91 S.E.2d 648, 653 (1956) (when allegations of jury misconduct are sufficient to indicate the verdict was affected thereby, a trial court has a duty to investigate and determine whether, as a matter of fact, the jury did engage in misconduct). The evidence presented at that hearing amply supported the court's conclusions that there was probably no misconduct and clearly no prejudice to the defendant.

At best, Picataggi could only recall juror discussions regarding defense counsel's techniques of cross-examination and the comment “he ... got to the bottom of it.” She could not remember any other specific comments by the jurors, or whether any juror discussions about the evidence transpired after the court instructed them not to do so in response to the jury's question. And, Picataggi admitted that no juror expressed an opinion about Jackson's guilt or innocence. That fact distinguishes this case from Haddad. Thus, we conclude that neither a new trial nor any further investigation by the circuit court was warranted. We said many years ago that “[i]f gossip of [jurors] among themselves, or surmise, is to be the basis of new trials there would be no end to litigation.” Margiotta v. Aycock, 162 Va. 557, 568, 174 S.E. 831, 835 (1934). That statement remains true today.

E. VIDEO–TAPED CONFESSION AND TRANSCRIPT

Jackson asserts that the circuit court erred in allowing the jury to use a transcript of his video-taped confession while the video was played during the trial, in overruling his motion for a mistrial because of problems that occurred while watching the video tape and using the transcript, and in allowing the jury to review the video-taped confession during their deliberations. We find no merit to any of these claims.

The circuit court directed that a transcript of the video tape be prepared because portions of the video tape were inaudible and the court concluded that it would be helpful for the jurors to have the transcript while they were viewing the video tape. At trial, Jackson claimed the transcript was not accurate and thus objected to the jury's use of it. The circuit court disagreed and found that the transcript was as accurate as it could be and that it was incomplete because some portions of the video tape were inaudible. Before the jurors watched the video tape, the court instructed them that the transcript was “merely a guide ... [and was] not evidence.” The court further instructed that the evidence was the tape itself and the audio portion of it, and that the transcript would be retrieved after the video tape was played and could not be taken into the jury room during deliberations. Finally, the court told the jury that, although there would be places in the transcript stating that the video tape was inaudible, it was, nevertheless, the jury's “responsibility to listen to the tape and determine what, in fact, [was] being said.” The court reminded the jurors of these instructions when they finished viewing the video tape.

“A court may, in its discretion, permit the jury to refer to a transcript, the accuracy of which is established, as an aid to understanding a recording.” Fisher v. Commonwealth, 236 Va. 403, 413, 374 S.E.2d 46, 52 (1988); accord Burns v. Commonwealth, 261 Va. 307, 330, 541 S.E.2d 872, 888 (2001). Although Jackson argues on appeal that the transcript was inaccurate, he points only to the fact that some words were missing because the video tape was inaudible at certain points, that the transcript was incorrectly paginated, and that one page was missing. However, those problems did not render the transcript inaccurate. In light of the lengthy instructions that the circuit court gave the jurors regarding the purpose of the transcript and their use of it, we are persuaded that the court did not abuse its discretion in allowing the jury to use the transcript of the defendant's video-taped confession. See id. (trial court did not abuse its discretion by allowing jury to use transcript that was not complete).

During the playing of the video tape, it was discovered that the pages in one juror's transcript were partially out of order. After that problem was corrected, the court directed the Commonwealth to rewind the video tape approximately two minutes. Subsequently, it was discovered that the jurors' transcripts were missing one page. Playing of the video tape was momentarily stopped while that problem was corrected. Because of these problems and Jackson's assertion that the jurors rarely looked up from the transcript and thus did not watch the video tape, he moved for a mistrial at the conclusion of the playing of his video-taped confession. The circuit court overruled the motion, finding that the jurors had paid close attention to both the video tape and the transcript. The court also noted that the amount of the video tape that was replayed was minimal and that all the problems with the transcripts were quickly corrected. The court did not err in overruling the motion for a mistrial.

Finally, Jackson claims that undue emphasis was placed on his confession and investigator Peterson's testimony regarding his interrogation of the defendant because the jury was allowed to take the video tape into the jury room during deliberations. However, Code § 8.01–381 provides that “[e]xhibits may, by leave of court, be” carried into the jury room. “Exhibits requested by the jury shall be sent to the jury room or may otherwise be made available to the jury.” Id. Thus, any exhibit introduced into evidence, including a defendant's written or recorded statement, is available to jurors during their deliberations. See Pugliese v. Commonwealth, 16 Va.App. 82, 90, 428 S.E.2d 16, 23 (1993). That jurors may put emphasis on certain evidence, perhaps a particular exhibit or testimony of a certain witness, is simply part of what they do when weighing and considering the evidence. Id. Thus, the court did not abuse its discretion in allowing the jury to take the video tape into the jury room during deliberations.

F. PHOTOGRAPHS

Jackson first challenges the circuit court's ruling allowing the Commonwealth to use an “in-life” photograph of the victim. Mrs. Phillips' son identified the photograph during his direct examination, FN6 and the Commonwealth displayed the photograph during its closing argument in the guilt phase of the trial for approximately seven seconds. The court did not allow the jury to take the photograph into the jury room. The defendant claims that the photograph had no probative value and was used to arouse the sympathies of the jury. FN6. The circuit court noted for the record that the “in-life” photograph of Mrs. Phillips was displayed in the Commonwealth's case-in-chief for approximately 15 to 20 seconds but that it was not passed to the jury.

We conclude that the circuit court did not abuse its discretion in allowing the use of the “in-life” photograph of Mrs. Phillips. See Bennett v. Commonwealth, 236 Va. 448, 471, 374 S.E.2d 303, 317 (1988) (no abuse of trial court's discretion to admit photograph showing victim one month before she died). The photograph was displayed only twice for brief periods of time. Additionally, the photograph was not given to the jury or taken into the jury room during deliberations. The defendant also claims that the circuit court erred in admitting into evidence photographs of Mrs. Phillips taken during the autopsy. He specifically challenges the admission of duplicate photographs of Mrs. Phillips' face and an enlarged photograph of her vaginal area. The defendant asserts that any probative value of these photographs was outweighed by their prejudicial and inflammatory effect upon the jury.

Although Jackson does not identify the challenged photographs by exhibit number, we assume that he is complaining about two photographs of Mrs. Phillips' face, Commonwealth Exhibit Numbers 47 and 48; and the enlarged photograph of her vaginal area, Commonwealth Exhibit Number 51. These are the photographs to which the defendant objected at trial. The Commonwealth introduced each of these during the medical examiner's testimony. Number 47 depicted the front of Mrs. Phillips' face, and number 48 was a side view. Number 51 showed a laceration in the rear portion of her vaginal area. Each photograph depicted different injuries suffered by Mrs. Phillips.

We agree with the circuit court's conclusion that the two facial photographs were “not shocking” or “gruesome” and that Number 51 was simply “part of the facts of this particular case.” Thus, the court did not abuse its discretion in admitting these photographs. The photographs were relevant to the issues of premeditation, intent, and malice. See Gray v. Commonwealth, 233 Va. 313, 342, 356 S.E.2d 157, 173 (1987); Stockton v. Commonwealth, 227 Va. 124, 144, 314 S.E.2d 371, 384 (1984). And, contrary to the defendant's argument, any prejudicial effect of the photographs did not outweigh their probative value.

G. USE OF PILLOW FOR DEMONSTRATIVE PURPOSES

During closing argument, the Commonwealth used a pillow to demonstrate the length of time that Jackson held the pillow over Mrs. Phillips' face. The Commonwealth asked the jury how such an act could not be indicative of a specific intent to kill. The defendant objected on the basis that the Commonwealth was not using the actual pillow found at the crime scene and that the demonstration would incite and inflame the jury. The circuit court overruled the objection but directed the Commonwealth to tell the jury that the pillow was “not the actual size and shape of the pillow used” to suffocate Mrs. Phillips and that the Commonwealth was using a pillow only for demonstrative purposes.

“Admission of items of demonstrative evidence to illustrate testimonial evidence is ... a matter within the sound discretion of a trial court.” Mackall, 236 Va. at 254, 372 S.E.2d at 768. We conclude that the circuit court did not abuse its discretion. As directed by the court, the Commonwealth instructed the jury that the pillow was not the actual pillow found at the crime scene and that it was being used for demonstrative purposes. Furthermore, the court also told the jury that the pillow was not the one found on Mrs. Phillips' bed. Finally, the Commonwealth's demonstration did not distort the evidence concerning the manner of Mrs. Phillips' death.

H. AUTOPSY REPORT

Jackson asserts that the circuit court erred in admitting the autopsy report into evidence and allowing that report to be given to the jury. When the defendant objected to the introduction of the report, the court indicated that it would redact any opinion expressed by the medical examiner in the report. Although Jackson asserts on brief that the report was admitted into evidence during the medical examiner's testimony, that factual statement is not accurate. The defendant cross-examined the medical examiner about his report, but at no point during his testimony was the autopsy report admitted into evidence. The report is not marked as an exhibit and is only stamped as having been filed in both the General District Court and the Circuit Court of the City of Williamsburg and County of James City.

Although Code § 19.2–188 provides that “[r]eports of investigations made by the Chief Medical Examiner, his assistants or medical examiners ... shall be received as evidence in any court or other proceeding,” the autopsy report concerning Mrs. Phillips was not admitted into evidence in this case. Thus, this claim has no merit.FN7 FN7. In Fitzgerald v. Commonwealth, 223 Va. 615, 630, 292 S.E.2d 798, 806–07 (1982), we held that the Commonwealth was not required to elect between introducing an autopsy report or a medical examiner's t