12th murderer executed in U.S. in 2004

897th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

6th murderer executed in Texas in 2004

319th murderer executed in Texas since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

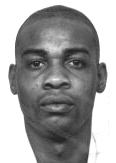

Bobby Ray Hopkins B / M / 26 - 36 |

Jennifer Westin W / F / 19 Sandi Marbut W / F / 18 |

Summary:

Between 4:00 and 5:00 a.m. on July 30, 1993, Hopkins entered the home of 18-year-old Sandi Marbut and her 19-year-old cousin Jennifer Weston. Hopkins attacked Sandi with a knife, cutting her over 40 times, and evidence of defensive wounds indicated that she struggled and fought to survive. Hopkins was also cut during the attack. When Jennifer came downstairs, Hopkins attacked her at the foot of the stairway, stabbinig her 66 times. Both girls died from the knife wounds. Later that evening, Hopkins gave a videotaped interview admitting that he went to the home and got into an argument with Sandi, who pulled a knife. During the struggle he stabbed her. A bloody footprint found at the scene matched a bloody boot taken from Hopkins. DNA testing confirmed Hopkins blood at the scene. Witnesses testified that Hopkins had been to the home two weeks earlier and was accused by Sandi of stealing money. At the time Hopkins committed the murders, he was on probation for dealing cocaine.

Citations:

Hopkins v. Cockrell, 325 F.3d 579 (5th Cir. Tex. 2003). (Habeas)

Final Meal:

None.

Final Words:

"Warden, at this time I have no statement, sir."

Internet Sources:

Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Executed Offenders (Bobby Hopkins)

Texas Department of Criminal Justice

Texas Attorney General Media Advisory

MEDIA ADVISORY - Tuesday, February 10, 2004 - Bobby Ray Hopkins Scheduled For ExecutionAustin–Attorney General Greg Abbott offers the following information about 36-year-old Bobby Ray Hopkins, who is scheduled to be executed after 6 p.m. Thursday, February 12, 2004. In 1994, Hopkins was sentenced to death for two killings in Johnson County, south of Fort Worth.

FACTS OF THE CRIME

Hopkins, a former bull rider, was convicted and sentenced to die for the brutal murders of 18-year-old Sandi Marbut and her 19-year-old cousin Jennifer Weston. The evidence presented at trial is as follows.

On the evening of July 30, 1993, Sandi and Jennifer had some friends over at their apartment, and Sandi drove the last guest home about 4:00 a.m. the next morning. Between 4:00 and 5:00 a.m., Hopkins entered the apartment. Sandi was in the downstairs living room on the couch. Hopkins attacked Sandi, stabbing and cutting her approximately forty times. The evidence of defensive wounds indicated that she struggled and fought to survive. The evidence also indicated that she was probably conscious for several minutes during the attack.

Jennifer came downstairs while Hopkins was attacking Sandi. Hopkins saw Jennifer and proceeded to attack her at the foot of the stairway. Jennifer tried to flee upstairs but was overpowered. She died at the landing at the top of the stairs after sustaining sixty-six stab wounds.

According to the police, Hopkins began to search the bedrooms for money. Hopkins entered the bathroom and tried to clean the blood off his body. He took some towels to try to stop the bleeding from his wounds. He then walked down the stairs and exited the apartment. Later that evening, Sandi’s parents found her on the living room floor and discovered Jennifer at the top of the stairs. There were blood stains and pools of blood all over the apartment.

On August 5, 1993, the police searched the area around the apartment and found two blood stained towels in a culvert between the girls’ apartment and Hopkins’ home. The towels belonged to the girls and were given to them by Sandi’s parents. The blood on the towels was consistent with Hopkins’ blood. Blood on hairs found on the towels was consistent with the blood types of Sandi, Jennifer, and Hopkins. On August 22, 1993, a knife was discovered in weeds outside of the apartment on a route between the girls’ apartment and Hopkins’ home. The blood on the knife was consistent with the blood of Hopkins, Sandi, and Jennifer.

On the evening the bodies were found, Texas Ranger George Turner questioned several bystanders at the scene and, as a result, went in search of Hopkins. Turner learned that Hopkins had been in the girls’ apartment approximately two weeks before the murders and, at that time, got in an argument with Sandi over money that was missing from her purse. Sandi thought that Hopkins had taken the money and asked him to leave and not come back.

Later that evening, Ranger Turner interviewed Hopkins and noticed that Hopkins had cuts on his hands and arms. Turner also noticed what appeared to be blood on Hopkins’ boots. Hopkins allowed Turner to take the boots. Subsequent tests showed that the blood on the boots was consistent with the blood of Jennifer, Sandi, and Hopkins. Virginia Smith, a nurse at the Johnson County Law Enforcement Center, drew blood from Hopkins and noticed fresh scratches or cuts on his hands.

Hopkins gave a videotaped interview to Captain Tony Knott of the Hobbs, New Mexico Police Department. Knott had known Hopkins when Hopkins lived in New Mexico. In the interview, Hopkins stated that he went over to Sandi’s and Jennifer’s apartment around 4 or 5 a.m. He and Sandi began to argue, Sandi got a knife, a struggle ensued, and he stabbed her. Hopkins admitted that he was cut during the altercation and bled in the apartment.

As a result of serology testing, the blood stains in the apartment were determined to be consistent with Hopkins’ blood. His blood was located in numerous areas in the apartment, including on a light switchplate in the living room, the living room wall, a sock, a bathroom rug and faucet, a shoe and a magazine in Jennifer’s bedroom, a newspaper article in Jennifer’s purse, the top of the stairway landing, and a chest drawer in Sandi’s bedroom.

The Fort Worth Crime Laboratory performed tests that showed blood matching Hopkins’ DNA profile on a sock, the bathroom rug, the living room wall, and on one of the towels. Genescreen in Dallas also performed tests that revealed blood matching Hopkins’ DNA profile on a cotton ball, a sock, and a magazine. Additional testing showed blood matching Hopkins’ DNA profile on the front door knob, the bathroom rug, the light switchplate in the living room, the bathroom, the socks, the newspaper clipping in Jennifer’s purse, and on a shoe. Further, Hopkins’ boot matched the print of a boot left in the blood on the carpet in Jennifer’s bedroom.

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

On October 1, 1993, Hopkins was indicted in the 18th Judicial District Court of Johnson County, Texas, for the capital offense of murdering Sandi Marbut and Jennifer Weston during the same criminal transaction. After Hopkins pleaded not guilty, a jury found him guilty of the capital offense on May 24, 1994. On May 25, 1994, after a separate punishment hearing, the court assessed Hopkins’ punishment at death.

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed Hopkins’ conviction and sentence in an unpublished opinion on October 1, 1997. Hopkins then filed a state application for writ of habeas corpus in the trial court. The application was denied by the Court of Criminal Appeals based on the trial court’s findings on September 16, 1998.

On June 17, 1999, Hopkins filed a federal habeas petition in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas, Dallas Division. On August 9, 2001, a magistrate issued a recommendation that Hopkins be denied habeas relief. On September 28, 2001, the district court entered an order and judgment adopting the magistrate’s findings in full and denying habeas relief. Hopkins then appealed the district court’s judgment to the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. That court affirmed the district court judgment in a published opinion on March 20, 2003. Johnson subsequently petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court for certiorari review. The Supreme Court denied the petition on October 20, 2003.

On February 10, 2004, Hopkins filed a successive habeas application in state district court in Johnson County. Court action on the application is pending.

PRIOR CRIMINAL HISTORY

At the time Hopkins committed the murders, he was on probation for delivery of a controlled substance, cocaine. Alice Finley, Hopkins’ probation officer, testified that Hopkins performed poorly on probation. Hopkins did not comply with the requirement to report monthly and once told her that he had used cocaine over the weekend. After numerous attempts to get Hopkins to report, she filed a revocation motion.

Raoul McPeters, formerly a detective with the Hobbs, New Mexico Police Department, described an incident when Hopkins and another man went up to a car, opened the driver’s door, pulled the driver out, and beat him. McPeters also had worked a shoplifting case where Hopkins had been charged with taking two kegs of beer and a bottle of whiskey. Further, McPeters and two other officers testified that Hopkins was not a peaceful or law-abiding citizen.

Sheila Lamonde, who knew Hopkins and was best friends with his former wife, Kari Williams, testified that in August, 1989, Hopkins became very upset because Kari was driving a pick-up truck and went over a bump too fast. He jumped out of the truck at a stop sign, pulled Kari out of the truck by her hair, and threw her in the back of the truck. At the next stop sign, Kari jumped out of the truck and ran away. Hopkins went after Kari, and Sheila followed. When Sheila caught up with them, Hopkins was slamming Kari’s head into a brick wall. Kari had delivered a baby by caesarean section two weeks before and still had stitches. Sheila tried to get her purse from the truck and leave, but Hopkins grabbed her by the hair and proceeded to slam her head into the concrete. Sheila had a black eye, a bloody nose, and a bloody lip as a result of Hopkins’ attack.

Kari testified that her relationship with Hopkins was violent. On July 15, 1988, Hopkins assaulted her and gave her a bloody nose. On December 1, 1988, Kari found out she was pregnant and told Hopkins, who was initially glad. However, he later became abusive and physically assaulted her by grabbing her hair and dragging her across the concrete. On September 30, 1989, Hopkins tried to grab Kari while she was in her father’s Suburban. When Kari’s friend opened the passenger door, Hopkins pulled Kari out and kicked her repeatedly. She called the police and ultimately needed medical attention. Hopkins spent twenty days in jail as a result of this incident. Last, shortly before they divorced, Hopkins called Kari and threatened to kill her and her son. Hopkins then burned her clothes and possessions in the yard in front of the house.

On July 31, 1993, in the early evening, the bodies of 18-year-old Sandi Marbut and her 19-year-old cousin Jennifer Weston were discovered by Sandi’s parents. According to Sandi’s father, the girls’ bodies were found in their apartment, which was across the street from Sandi's parents’ house. On the evening of July 30, 1993, Sandi and Jennifer had some friends over at their apartment, and Sandi drove the last guest home about 4:00 a.m. the next morning. It was alleged that between 4:00 and 5:00 a.m., Bobby Ray Hopkins entered the apartment and attacked Sandi, who was in the downstairs living room sleeping on the couch, stabbing and cutting her approximately 40 times. Jennifer came downstairs while Hopkins was attacking Sandi. Hopkins saw Jennifer and proceeded to attack her at the foot of the stairway. Jennifer apparently tried to flee upstairs but was overpowered. She died at the landing at the top of the stairs after suffering 66 stab wounds.

According to the police, Hopkins began to search the bedrooms for money. Hopkins entered the bathroom and tried to clean the blood off his body. He took some towels to try to stop the bleeding from his wounds. He then walked down the stairs and exited the apartment. Later that evening, Sandi’s father found her on the living room floor and discovered Jennifer at the top of the stairs. Texas Ranger George Turner testified that on the evening the bodies were found, July 31st, he questioned several bystanders at the scene outside the apartment and, as a result, went in search of Hopkins. Apparently, Hopkins had been in the girls’ apartment approximately two weeks before the murders. Hopkins was there with two other men and got in an argument with Sandi over money that was missing from her purse. Sandi thought Hopkins had taken the money and asked him to leave and not come back. Ranger Turner interviewed Hopkins on July 31st, and noticed that Hopkins had cuts on his hands and arms. Turner also noticed what appeared to be blood on Hopkins’ boots. Hopkins allowed Turner to take the boots.

Subsequent tests showed the blood on the boots was consistent with the blood of Jennifer, Sandi and Hopkins. On August 5, 1993, the police searched the area around the apartment and found two blood-stained towels in a culvert between the girls’ apartment and the house where Hopkins lived with his parents. The towels belonged to the girls and were given to them by Sandi’s parents. The blood on the towels was consistent with the blood of Hopkins. Blood on hairs found on the towels was consistent with the blood types of Sandi, Jennifer and Hopkins. On August 22, 1993, a knife was discovered in the weeds outside the apartment on a route between the girls’ apartment and Hopkins’ home. The blood on the knife was consistent with the blood of Hopkins, Sandi and Jennifer. Serology testing of the blood stains in the apartment indicated that the blood was consistent with Hopkins’ blood. His blood was located in numerous areas in the apartment, including on a light switch plate in the living room, the living room wall, a sock, a bathroom rug and faucet, a shoe and a magazine in Jennifer’s bedroom, a newspaper article in Jennifer’s purse, the top of the stairway landing, and one drawer of a chest in Sandi’s bedroom. DNA testing of Hopkins’ blood indicated that it was consistent with the blood found on various items throughout the apartment.

Further, Hopkins’ boot matched the footprint of a boot left in the blood on the carpet in Weston’s bedroom. In the weeks following the discovery of the bodies, while the State was developing the above evidence, Hopkins was held in isolation. Hopkins was held after being arrested pursuant to a felony probation revocation warrant alleging non-reporting and nonpayment. Apparently, it is unusual to hold such a violator in isolation. After fifteen days in isolation and eight interrogations by law enforcement officers (none of which resulted in a confession), the State called in Detective Tony Knott from New Mexico to just “talk” to Hopkins. Hopkins considered Knott a friend and apparently the two have known each other for quite some time. Knott and Hopkins were taken to a small room on August 19, 1993, which Hopkins alleges was under the guise of letting the two of them “catch-up on old times.” Prior to speaking, Knott claims to have read Hopkins his Miranda rights, though Hopkins claims not to remember this and the reading was not taped as required by Texas law. During this talk, Knott made many statements to Hopkins indicating that he wanted Hopkins to tell him about the murders and that the talk was just between the two of them.

During the course of this four-hour talk, Hopkins made incriminating statements, and Hopkins gave a videotaped interview to Knott. In this interview Hopkins stated that he went over to Sandi and Jennifer’s apartment around 4:00 or 5:00 a.m. He and Sandi began to argue, Sandi got a knife, a struggle ensued, and he ultimately stabbed her. Hopkins admitted that he was cut during the altercation and bled in the apartment. On May 13 and 14, 1994, the trial court held a Jackson v. Denno hearing to determine whether the confession should be admitted. The court found, amongst other things, that: Knott had given Hopkins the required warnings before both the first and second tapes of the interview and that Hopkins voluntarily waived those rights; Hopkins did not request an attorney prior to or during his confession; and, under the totality of the circumstances, the statement was voluntary. The trial court also determined that Hopkins desired to terminate the interview on page 203 of the transcribed statement, and ruled that any subsequent statement was inadmissible.

"Killer Bull Rider Executed for Slaying Two Women." (February 12, 2004)

HUNTSVILLE, Tex. - A former New Mexico bull rider convicted of stabbing two young women to death in their apartment more than a decade ago was executed by lethal injection Thursday night at the state prison here. Bobby Ray Hopkins, 36, became the second condemned killer in as many days to be executed in Texas. On Wednesday, Edward Lagrone, who killed three people, including a 10-year-old girl he had impregnated, was executed. Hopkins became the 319th condemned murderer executed in Texas since 1982 and the sixth so far in 2004.

Hopkins' execution was delayed for two hours while the U.S. Supreme Court considered last ditch appeals. His lawyers had asked for DNA retesting and also challenged a confession he gave to a police officer, in which Hopkins claimed he killed Sandi Marbut, 18, during a struggle with a knife. But when the high court turned thumbs down on his appeal, it was the end of the line for Hopkins. He had little to say. "Warden, at this time, I have no statement, sir," Hopkins said. The lethal dose of chemicals began at 8:11 p.m. and Hopkins was pronounced dead eight minutes later. Hopkins requested no last meal and didn't eat anything.

A Father Looks For Answers

Hopkins was sentenced to death for the 1993 murders of Marbut and her cousin, Jennifer Weston, 19. Their bodies were found in their Grandview apartment on July 31, 1993. Marbut was stabbed about 40 times. Weston was stabbed more than 60 times. The father of Sandi Marbut, Terry Marbut, told the Star-Telegram of Fort Worth that he wrote Hopkins a letter asking why he killed his daughter and Weston, but that Hopkins wrote him back saying he was innocent. "He didn't tell me anything he hadn't already put out," Marbut told the newspaper. Marbut told the newspaper that he asked Hopkins if he intended to kill the girls; if they had made him mad or if he panicked. The key evidence against Hopkins were traces of his blood found inside the apartment; the victims' blood found on his boots; and a controversial videotaped statement Hopkins gave to a New Mexico police detective brought in to interview Hopkins about the murders and trick him into confessing. Hopkins was not arrested immediately after the murders.

Police Trickery

He was held in "isolation" for 15 days on a violation of probation warrant. Hopkins had previously been convicted of a cocaine-related charge. This was unusual. A New Mexico detective who knew Hopkins from his native state was brought in to question him about the murders. Hopkins had apparently known the detective for a long period of time and the detective assured Hopkins that the conversation would be kept between the two men, according to court documents. Hopkins told the detective that he went to the apartment that morning and argued with Marbut. Marbut, he claimed, tried to stab him. During a struggle, Hopkins said he stabbed Marbut, federal court documents stated.

Caught Stealing By Victim

Hopkins had previously visited the apartment and was accused by Marbut of stealing money from her purse. Hopkins claimed he was having an affair with Marbut, court documents said. Defense lawyers say that Hopkins had agreed to talk to the detective, but the detective had promised that the conversation was "just between the two of them." The lawyers wanted the entire statement Hopkins made thrown out. However, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit thought differently. The court ruled that although the detective used trickery and deceit, there was an "overwhelming" amount of circumstantial evidence against Hopkins. In addition, the federal appeals court found that prosecutors did not rely only on the confession to pin the murders on Hopkins.

Heavy Circumstantial Evidence

Blood from the victims' was found on Hopkins boots; a boot print found in blood in Weston's bedroom matched Hopkins' footprint; Hopkins' blood was found in various locations around the apartment; Hopkins had cuts on his arms and hands; two blood-stained towels, belonging to the victims, were found in a culvert between the victims' apartment and the house where Hopkins lived with his parents. The blood on the towels was consistent with the blood of Hopkins and the victims. "In light of the overwhelming amount of circumstantial evidence present in this case, as well as the state's limited reliance on the confession at trial, we hold that any error in admitting Hopkins' confession was harmless," the federal appeals court found. The bodies of the victims were discovered by Marbut's parents. The apartment the young women lived in was across the street from the home of Marbut's parents. The women had had some friends over the apartment that night and drove the last guest home at around 4 a.m. Marbut, who was in the living room sleeping on the couch, was stabbed 40 times.

Legal Battle Fruitless

Prosecutors believe that Weston came downstairs while Marbut was being attack and then tried to flee back up the stairs. However, she was overpowered on the landing and stabbed more than 60 times. Hopkins also claimed ineffective assistance of counsel. He claimed that his trial lawyers did not present evidence that he might be mentally impaired, had previously received a serious head injury and was abusing alcohol and drugs. However, the appeals court says it routinely dismissed claims made from defendants that lawyers failed to present evidence of alcohol and drug abuse as an excuse. The court also stated that even the doctors who examined Hopkins were not sure whether he actually suffered a serious head injury. In writings posted on the Internet, Hopkins had written about his allegedly harsh treatment on Texas death row and also claimed he was innocent of the murders.

Texas Execution Information Center by David Carson.

Bobby Ray Hopkins, 36, was executed by lethal injection on 12 February 2004 in Huntsville, Texas for the murder of two women in their home.

On 31 July 1993 before dawn, Hopkins, then 26, entered the apartment of Jennifer Weston, 19, and her 18-year-old cousin, Sandi Marbut. Marbut was in the downstairs living room. Hopkins stabbed and cut her approximately 40 times. Weston came downstairs while Hopkins was attacking Marbut. Hopkins began attacking her at the foot of the stairs. Weston tried to flee by running upstairs, but she died on the top landing. She had 66 stab wounds.

Hopkins then searched the bedrooms for money. He also went into the bathroom and washed some of the blood off of himself. He also used some bathroom towels to try to stop the bleeding from his own wounds. He then exited the apartment. The girls' bodies were discovered later that day by Marbut's parents.

Texas Ranger George Turner learned from bystanders at the scene that Bobby Hopkins had been in the girls' apartment approximately two weeks earlier and, at that time, got in an argument with Marbut over money that was missing from her purse. Marbut accused Hopkins of stealing the money and asked him to leave and not come back. Later that evening, Ranger Turner interviewed Hopkins and observed cuts on his hands and arms. He also noticed blood on Hopkins' boots. The prints of Hopkins' boots were matched to a bloodstain on the apartment floor near where Weston was stabbed. Hopkins was arrested on 4 August.

About a week after the murders, police found two blood-stained towels in a culvert between the murder scene and Hopkins' home. The towels were given to Marbut by her parents, and the blood matched Hopkins' blood. Two weeks later, a blood-stained knife was discovered outside the apartment. The blood matched Hopkins and the two victims. Hopkins' blood was also found in numerous areas of the murder scene, including the inside of Marbut's chest of drawers and the inside of Weston's purse.

After holding Hopkins in isolation for 15 days and questioning him eight times, authorities brought in Tony Knott, a New Mexico detective who Hopkins considered to be a friend. After a four-hour session with Knott, Hopkins made a videotaped confession. He stated that he went to the girls' apartment at around 4:00 or 5:00 a.m. He and Sandi Marbut began to argue. Hopkins said that Marbut got a knife, a struggle ensued, and he stabbed her in self-defense.

Hopkins had previous convictions for assault, dealing cocaine, shoplifting, driving while intoxicated, and non-payment of child support. He had been in and out of jail several times and was on probation at the time of the murders. He had no prior prison record.

At his trial, Hopkins pleaded not guilty. His lawyers attempted to exclude the videotaped confession from evidence, on the grounds that Hopkins was not properly advised of his Fifth Amendment right to remain silent before making the statement. The trial judge allowed most of the confession to be admitted. A jury convicted Hopkins of capital murder in May 1994 and sentenced him to death.

On appeal, The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals ruled that the beginning part of Hopkins' confession was obtained without proper Fifth Amendment disclosure, but any incriminating statements he made were corroborated later in the confession, after he was properly informed of his rights. The TCCA affirmed the conviction and sentence in October 1997.

Hopkins maintained his innocence on an anti-death-penalty web site. He stated that investigators drew his blood, then planted the blood at the scene to frame him. He also stated that his videotaped confession was coerced. In March 2003, the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that although several aspects of Hopkins' confession were problematic - specifically, that Hopkins was not properly advised of his rights, and that Detective Knott lied to Hopkins to get him to talk - the physical and circumstantial evidence against him was overwhelming, and that "any error in admitting Hopkins' confession was harmless."

Hopkins' execution was delayed for about two hours while last-minute appeals were being considered. At his execution, when asked if he had a final statement, Hopkins replied, "Warden, at this time I have no statement, sir." He was pronounced dead at 8:19 p.m.

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

Bobby Ray Hopkins, TX - Feb. 12, 6 PM CST

The state of Texas is scheduled to execute Bobby Ray Hopkins, a black man, Feb. 12 for the 1993 stabbing deaths of two white women, Jennifer Weston and Sandi Marbut in Johnson county. The execution is scheduled for 6 p.m. CST. Mr. Hopkins maintains that he is innocent and has been outspoken regarding Texas’ horrific death-row conditions.

The two women were found dead on July 31, 1993. Police learned that Sandi Marbut had a recent disagreement with Mr. Hopkins and thus they considered him a suspect. When they talked to Mr. Hopkins, they noticed deep wounds on his hands. They asked to examine his boots, and also for a DNA sample, which he gave. Mr. Hopkins was later arrested for a parole violation and held in isolation for 15 days. He was not appointed a lawyer and refused to make a statement. The police then summoned an officer who was a friend of Mr. Hopkins. Their interview was secretly videotaped, and again no lawyer was appointed or present. Mr. Hopkins confessed to the officer, and stated that he had sustained a cut to his hand when Sandi Marbut came at him with a knife when they started to argue, that he took the knife away from her and stabbed her, and that he stabbed Jennifer Weston because she came down the stairs and witnessed him stabbing Marbut.

DNA evidence at the scene matched Mr. Hopkins’s, and blood on his boots was found to be consistent with a mixture of his and the two victims’.

The defense presented testimony from Mr. Hopkins’s mother, step-father, sister, and brother-in-law, who all shared an apartment with him, that he was home at the time of the murders. Furthermore, it is alleged that there are blood samples found at the scene that were not admitted as evidence because they did not match those of Mr. Hopkins, and that skin samples found under the victims’ fingernails were not admitted as evidence because they did not match either.

Hopkins’ supporters maintain that a man named Michael Meeks was at a party at the victims’ home that night, and threatened to kill one of the women if she did not “get back together with him.” According to Mr. Hopkins’ supporters, Mr. Meeks then proceeded upstairs and ransacked her bedroom.

Mr. Hopkins further argues that he had ineffectiveness of counsel at trial in both the verdict and the punishment phases. In the verdict phase, the defense did not present their own expert DNA testimony, and in the punishment phase certain mitigating evidence was not admitted; including evidence regarding his relatively low intelligence, a childhood head injury, and his abuse of drugs and alcohol. He was denied funds for an MRI to prove his head injury.

There are several causes of concern in Mr. Hopkins’s case. Execution is a gross human rights violation and costs money that could be better spent on actual crime prevention. Please contact Gov. Perry and urge him to declare a moratorium on executions in Texas, and commute the death sentence of Bobby Ray Hopkins.

"Convicted killer in two knife slayings executed," by Michael Graczyk. (AP Feb. 12, 2004, 8:34PM)

HUNTSVILLE -- A former bull rider from New Mexico was executed tonight for fatally slashing and stabbing two young women more than 10 years ago while he was on probation for a drug conviction. "Warden, at this time I have no statement, sir," Bobby Ray Hopkins said when asked if he had a final statement. As the lethal drugs began taking effect, he gasped and gurgled. Eight minutes later at 8:19 p.m., he was pronounced dead.

Hopkins, 36, was the sixth Texas inmate put to death this year and the second in as many nights. His execution was held up about two hours while last-minute appeals were considered.

Hopkins insisted he wasn't responsible for the slayings of Sandi Marbut, 18, and her cousin, Jennifer Weston, 19, at their apartment in Grandview in Johnson County, about 35 miles south of Fort Worth. Marbut was cut about 40 times with a dull knife, its blade blunted to about 3 inches. Weston, a cousin from Indiana, had 66 wounds. Their bodies were found July 31, 1993, by Marbut's father, who lived across the street. "Unless you've experienced it, you can't imagine it," Terry Marbut, who planned to witness the execution, told The Associated Press. "It changes your perspective on everything. It was extremely traumatic."

Hopkins' lawyers had filed motions for clemency, for a reprieve and asked in appeals that DNA evidence used at Hopkins' trial be retested. They also were questioning the legality of a confession he gave. Hopkins, from Lea County, N.M., was on probation for dealing cocaine when his name surfaced as authorities canvassed a crowd that gathered outside the home where the killings occurred. Bystanders told officers Hopkins, who was wanted for a probation violation, previously was at a party there and had argued with Sandi Marbut over $40 missing from her purse. A Texas Ranger tracked down Hopkins. A blood spot on his boot matched the blood of the victims. A bootprint from the slaying scene matched Hopkins' boot.

Hopkins was questioned eight times and held in isolation for 15 days, refusing to confess. A detective he knew from Hobbs, N.M., came to talk with him and during a four-hour interview Hopkins told how he went to the home, a struggle ensued and he stabbed Marbut. He also said he was cut in the fight. The confession became an issue in Hopkins' appeals because of questions about whether he was properly informed of his rights and whether it should have been allowed into evidence. The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, while saying it was troubled by the methods used to obtain the confession, last year characterized the error as harmless because of overwhelming circumstantial evidence against Hopkins.

His blood was found in numerous places in the apartment, including a light switch, a wall, a sock, a bathroom rug and faucet, a shoe and a magazine, a newspaper article in one of the victims' purse, the top of a stairway and a drawer in a bedroom. Hopkins accused authorities of taking vials of his blood and sprinkling the contents throughout the crime scene. Doug Allen, who was police chief in Grandview at the time, called the allegations "fairy tales." "Anyone who sat through the case down there has no doubt who the murderer was," Allen said this week.

Hopkins refused to speak with reporters while on death row, but on an anti-death penalty Web site he wrote of his innocence and "wrongful conviction." Evidence showed Marbut was sleeping downstairs and was attacked first. The commotion likely woke Weston, who came from a second floor and was confronted by her killer.

"Slain teen's dad still seeking answers," by Martha Deller. (February 12, 2004)

GRANDVIEW - For 10 1/2 years, Terry Marbut has been living with the chilling uncertainty of why his daughter and her cousin were murdered, stabbed more than 100 times, in their Grandview duplex. Two weeks ago, desperately seeking answers he believed only the killer could provide, Marbut wrote Bobby Ray Hopkins, who is scheduled to die today for the July 31, 1993, murders of Sandi Marbut, 18, and Jennifer Weston, 19. "Was it your intention to kill these girls? Did they make you mad?" Marbut recalls writing. "Or did you go in to burglarize the house and did Sandi sleeping there surprise you and you panicked?"

Hopkins replied with the same message that is posted on his Web site, saying that he was wrongly convicted, that he was the victim of a conspiracy cooked up by authorities. "He didn't tell me anything he hadn't already put out," Marbut said.

On Tuesday, the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles rejected Hopkins' bid to halt his execution. Gov. Rick Perry may still grant a 30-day reprieve, but Perry's spokeswoman said he won't make that decision until Hopkins has exhausted other legal efforts. Marbut will be at today's execution, sitting with relatives and Lisa Powell, the prosecutor who is still haunted by the case. And while Marbut hopes that Hopkins still might provide details of the deadly night, he suspects that the answers he wants will die with the man who holds them.

In 1993, the slayings seemed to touch everyone in the Johnson County town of 1,400, about 35 miles south of Fort Worth, where the school district and the lumberyard are the biggest employers. For months, gossip about the crime topped Zebra football as the hot topic at Granny's Kountry Kitchen and Neal's Convenience Store, the town's main hangouts. "I grew up in this little town in this little neighborhood, and nothing ever happened," said Marbut, who now lives in Whitney near Hillsboro. "You can't expect anything will happen like this, so I let my guard down. I made a mistake." Marbut could see his daughter's duplex across the railroad tracks from his home. If her door was open, he could see inside the living room.

On that summer day in 1993, he watched the duplex all day, thinking the teens were still sleeping after a late party or had gone to another party in Arlington. About 7 p.m., he and his then-wife, Bonni, checked on the teens. When Marbut found his daughter on the living room floor, he thought she had fallen and hit her head. "I sat beside her, trying to wake her up," he said, recounting the events calmly, almost as if they had happened to someone else. "When I realized she was dead, I wondered what had happened to Jennifer. We found her dead at the top of the stairs still in her pajamas." Marbut ran back across the tracks, yelling for his parents to call 911. Forensic experts determined that the teens had been dead 12 to 14 hours. Sandi had been stabbed 40 times, Jennifer 66 times.

When Marbut learned that Hopkins was the primary suspect, he second-guessed his reaction two weeks earlier, when Sandi had asked him for a gun. She had wanted to protect herself from Hopkins, whom she had accused of stealing money from her purse in her duplex. Hopkins had apparently tagged along with some other young people who hung out at the duplex, Marbut and police said. "I told her, 'You don't need a gun. ... Someone will get hurt,' " Marbut said. " 'I'm right across the street. I'll deal with it.' "There are a thousand what-ifs," he said. "I know I can't keep feeling guilty, but I do."

Police Chief Doug Allen was the first officer to respond to the emergency call. He asked another officer to question the gathering crowd of young people about anyone with whom the two teens had recently argued or fought. The crowd identified three possible suspects, including Hopkins. Allen sought help from Texas Ranger George Turner, who helped find Hopkins. Hopkins, who was on probation for a 1992 drug conviction, provided several vials of his blood. Turner also had him leave his boots, on which Turner noticed a small spot of blood, Allen said. Hopkins was then released. Fort Worth forensic consultant Max Courtney was brought in to gather physical evidence, and his team found a bloody boot print on the carpet near where Jennifer was stabbed. "I told Courtney, 'I know where that boot is. I took it off a suspect last night,' " Allen said. "It was a $160 Doc Martens boot with a distinct pattern. I've seen a lot of them since, but I hadn't seen any then." Four days after being questioned, Hopkins was arrested on the basis of the physical evidence. Photos of the boot print and the boot sole itself were introduced at the trial. "They lined up perfectly," Allen said.

Hopkins, 36, has declined recent interview requests, but his sister, Elizabeth Hopkins, and his niece, Ebony Davis, say the state is about to execute a man for a crime he didn't commit. They say they don't want to waste time talking about Hopkins' background or what happened to their family. "We're grieving as much as the victims' families," Davis said. "But we don't want sympathy. We're just trying to get the word out that the man is innocent."

Born in Hobbs, N.M., Hopkins was reared by his mother and stepfather, Dixie and James Wrighter. James Wrighter died in December 2002. Dixie Wrighter works as a cook at Granny's Kountry Kitchen, but she has designated daughter Elizabeth Hopkins and granddaughter Davis to speak for the family. In a Star-Telegram interview while he was jailed during the 1993 murder investigation, Bobby Hopkins said he was a mediocre student, started taking drugs in high school, had a son he rarely saw from an 18-month marriage, and made a living riding bulls and repairing cars.

Although there were other possible suspects, officers immediately went to the Wrighter home, according to Hopkins' four-page account on his Web site provided by the Canadian Anti-Death Penalty Coalition. Hopkins' Web site describes events similar to those recounted by Allen, but with a different perspective. After being arrested, he was repeatedly interviewed by officers who tried to get him to confess and was finally charged with capital murder, the Web site says. In recent interviews, Elizabeth Hopkins and Davis reiterated Bobby Hopkins' contention that police used his blood and boots to plant the evidence used to convict him. "How many pints of blood were drawn from him and how many were accounted for in court?" Davis asked. "Bobby turned himself in voluntarily, and they treated him unfairly from that day on." Allen and Powell denied that the evidence was planted.

Davis said authorities further betrayed her uncle by getting a childhood friend to coerce him into giving a statement. If the efforts to stop the execution fail, Elizabeth Hopkins said, she'll be there in the witness room to watch her brother die. "He really doesn't want his loved ones to see them murder him," she said. "But someone has got to be there for him. We're not going to let him lay there by himself while the state murders him."

Lisa Powell had been a prosecutor for five years and had tried rape and child sexual assault cases and even a capital murder case. But she said nothing prepared her for the Grandview murder scene she was called to in summer 1993. "That scene affected me like nothing has and probably nothing else ever will," she said. "It was horrible." Powell spent months preparing the case, learning to explain DNA -- genetic material unique to each individual -- to a jury in what would be Johnson County's first such case, said former state District Judge Kit Cooke, who presided at Hopkins' trial.

While Hopkins' videotaped confession was contested legally, Powell contends that overwhelming DNA evidence -- blood from Hopkins and the two victims found throughout the duplex -- convicted him. Appellate judges agreed. They ruled that parts of the confession were invalid but said the error was "harmless" and upheld the conviction. "They found Bobby's blood not just in one place in that house," Powell said. "You can trace his movements by the castoff blood from where he swung the blood. He can't really say, 'I'm not the one who did this.' I think the video confession was extremely secondary to everything else we had."

Powell left the district attorney's office in December 1994 to start her own law practice. She said she wanted more free time to start a family but was also affected by the Hopkins case. "I felt so deeply for those families," she said. "I couldn't let go of it." She will sit with Terry Marbut and his family at the execution. "I'm not fooling myself that it's going to be easy, but I want to go," Powell said. "As strange as this may sound, hopefully it will be closure for the families of the victims and for me, too." Marbut is hopeful as well.

Because Hopkins didn't use the self-addressed, stamped envelope Marbut sent, Marbut wonders if the condemned killer will write again before he dies. "That's grasping," he said, showing his frustration. "Honestly, I doubt anything else will come out of it. But I thought it was odd he held onto my envelope. I didn't ask him for an apology. I was just searching for answers that nobody knows but him."

Bobby Ray Hopkins Homepage (CCADP)

BOBBY RAY HOPKINS - A Plea For Justice From Death Row

Michael Meeks - bragging that he killed the women !

Chief of Police Doug Allen went to his house and told him if he did not shut his mouth that he would be in big trouble because he did not know what he was talking about ! ! ! When Chief Allen was questioned by my defence attorney and asked why he didn't investigate Michael Meeks, he replied and said that he felt there was not a need for him to do so. When asked if he went to Mr Meeks house to tell him to shut his mouth about killing the women, Chief Allen said that he did go to Mr Meeks house and told him to shut up or he would be in big trouble. When asked why would you go to a persons house and tell them to shut up when he is investigating a double murder ? Chief Allen replied and said he felt like Mr Meeks did not know what he was talking about, all of which is on record. (. . . Excerpt from 'Turn Of Events' by Bobby Ray Hopkins- link to page below )

Bobby's case was featured on FOX News network in June 2001

Bobby Ray Hopkins In the News 2004 Art by Bobby Ray Hopkins TURN OF EVENTS: DAY IN AND DAY OUT: A Plea For Justice From Death Row: More Writings By Bobby Ray Hopkins Letter To Friends And Supporters Involuntary Coerced Confession by Bobby Ray Hopkins

These Walls - A Writing By Bobby Ray Hopkins

Another Page In Support of Bobby Ray Hopkins

Sentenced to die because his name is Bobby? - In 1940, Bobby Hopkins' great uncle, Tommie Harris, was convicted of raping and killing a pregnant woman on the outskirts of Grandview...The victims in this case were also distant relatives of the woman murdered in 1940.

Questions In the Case (Excerpts From Hobbs Sun-Times Series ) - Very important points to consider, including lack of evidence, questions regarding integrity of evidence state claims, whether history and town prejudice may have had a hand in the suspicion falling on Bobby and on his conviction, as well as possible other suspects.

- Bobby and his friend - July 2001

TO CONTACT BOBBY RAY HOPKINS:

Bobby Ray Hopkins # 999101

The Web site of the Assocation (French Branch and Belgium Branch)

« Justice for Bobby Ray Hopkins »

On July the 31st 1993, two young white ladies (Sandy Marbut 18 years old and her cousin Jennifer Weston 19 years old) were found dead (stabbed) at their home, in Grandview (little Texas town).

On August the 4th 1993, Bobby Ray Hopkins (a 26 years old African-American) was arrested on unrelated charges.

After being incarcerated and interrogated for two weeks, Bobby finally made self-incriminating statements, during a four hour interview. This final interview was conducted by a childhood friend of Bobby's, who worked for a police agency in New-Mexico. This police officer, appearing as the first friendly face Bobby had seen since his arrest and the long ordeal of isolation and interrogation, was actually being used by the local police to gain Bobby's trust. The interview was being secretly tape-recorded by the local police. During this interview, Bobby was never assisted by an attorney.

Soon after, Bobby denied his statement, arguing that it was a COERCED CONFESSION. From then on, he never stopped claiming his innocence.

The manner in which Bobby's statement was obtained was not the only action taken during the police investigation that should be considered questionable in this case. It has been the issue most litigated, however.

Bobby has exhausted now all of his appeals :

Even though, his constitutional rights have been severely violated, the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals and the U.S Supreme Court denied Bobby's right to a new trial. According to a ruling made by the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, the incriminating statement Bobby gave to police should be considered a "coerced confession". However, the Court deemed this State misconduct to be "harmless".

Bobby Ray Hopkins has now an EXECUTION DATE

set for FEBRUARY 12TH 2004.

WE NEED YOUR HELP TO SAVE BOBBY !!!

Hopkins v. Cockrell, 325 F.3d 579 (5th Cir. Tex. 2003). (Habeas)

State prisoner who was convicted of capital murder petitioned for writ of habeas corpus. The United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas, Jorge A. Solis, J., denied the petition, and petitioner appealed. The Court of Appeals, DeMoss, Circuit Judge, held that: (1) petitioner's confession to murders was involuntary; (2) admission of the involuntary confession was harmless error; and (3) petitioner did not receive ineffective assistance of trial counsel.

Affirmed.

DeMOSS, Circuit Judge:

BACKGROUND

On July 31, 1993, in the early evening, the bodies of 18-year-old Sandi Marbut and her 19-year-old cousin Jennifer Weston were discovered by Marbut's parents. According to Marbut's father, the girls' bodies were found in their apartment, which was across the street from Marbut's parents' house.

On the evening of July 30, 1993, Marbut and Weston had some friends over at their apartment, and Marbut drove the last guest home about 4:00 a.m. the next morning. It was alleged that between 4:00 and 5:00 a.m., Bobby Ray Hopkins entered the apartment and attacked Marbut, who was in the downstairs living room sleeping on the couch, stabbing and cutting her approximately 40 times.

Weston came downstairs while Hopkins was attacking Marbut. Hopkins saw Weston and proceeded to attack her at the foot of the stairway. Weston apparently tried to flee upstairs but was overpowered. She died at the landing at the top of the stairs after suffering 66 stab wounds.

According to the police, Hopkins began to search the bedrooms for money. Hopkins entered the bathroom and tried to clean the blood off his body. He took some towels to try to stop the bleeding from his wounds. He then walked down the stairs and exited the apartment. Later that evening, Marbut's father found her on the living room floor and discovered Weston at the top of the stairs.

Texas Ranger George Turner testified that on the evening the bodies were found, July 31st, he questioned several bystanders at the scene outside the apartment and, as a result, went in search of Hopkins. Apparently, Hopkins had been in the girls' apartment approximately two weeks before the murders. Hopkins was there with two other men and got in an argument with Marbut over money that was missing from her purse. Marbut thought Hopkins had taken the money and asked him to leave and not come back.

Ranger Turner interviewed Hopkins on July 31st, and noticed that Hopkins had cuts on his hands and arms. Turner also noticed what appeared to be blood on Hopkins' boots. Hopkins allowed Turner to take the boots. Subsequent tests showed the blood on the boots was consistent with the blood of Weston, Marbut and Hopkins.

On August 5, 1993, the police searched the area around the apartment and found two blood stained towels in a culvert between the girls' apartment and the house where Hopkins lived with his parents. The towels belonged to the girls and were given to them by Marbut's parents. The blood on the towels was consistent with the blood of Hopkins. Blood on hairs found on the towels was consistent with the blood types of Marbut, Weston and Hopkins. On August 22, 1993, a knife was discovered in the weeds outside the apartment on a route between the girls' apartment and Hopkins' home. The blood on the knife was consistent with the blood of Hopkins, Marbut and Weston.

Serology testing of the blood stains in the apartment indicated that the blood was consistent with Hopkins' blood. His blood was located in numerous areas in the apartment, including on a light switch plate in the living room, the living room wall, a sock, a bathroom rug and faucet, a shoe and a magazine in Weston's bedroom, a newspaper article in Weston's purse, the top of the stairway landing, and one drawer of a chest in Marbut's bedroom. DNA testing of Hopkins' blood indicated that it was consistent with the blood found on various items throughout the apartment. Further, Hopkins' boot matched the footprint of a boot left in the blood on the carpet in Weston's bedroom.

In the weeks following the discovery of the bodies, while the State was developing the above evidence, Hopkins was held in isolation. Hopkins was held after being arrested pursuant to a felony probation revocation warrant alleging non-reporting and non-payment. Apparently, it is unusual to hold such a violator in isolation. After fifteen days in isolation and eight interrogations by law enforcement officers (none of which resulted in a confession), the State called in Detective Tony Knott from New Mexico to just "talk" to Hopkins.

Hopkins considered Knott a friend and apparently the two have known each other for quite some time. Knott and Hopkins were taken to a small room on August 19, 1993, which Hopkins alleges was under the guise of letting the two of them "catch-up on old times." Prior to speaking, Knott claims to have read Hopkins his Miranda rights, though Hopkins claims not to remember this and the reading was not taped as required by Texas law. [FN1] During this talk, Knott made many statements to Hopkins indicating that he wanted Hopkins to tell him about the murders and that the talk was just between the two of them. During the course of this four-hour talk, Hopkins made incriminating statements, and Hopkins gave a videotaped interview to Knott. In this interview Hopkins stated that he went over to Marbut's and Weston's apartment around 4:00 or 5:00 a.m. He and Marbut began to argue, Marbut got a knife, a struggle ensued, and he ultimately stabbed her. Hopkins admitted that he was cut during the altercation and bled in the apartment.

FN1. Hopkins later claimed that it wasn't until the beginning of a second tape that he was read these warnings, but he also later indicated that he was aware of the consequences of speaking to Knott.

On May 13 and 14, 1994, the trial court held a Jackson v. Denno hearing to determine whether the confession should be admitted. The court found, amongst other things, that: Knott had given Hopkins the required warnings before both the first and second tapes of the interview and that Hopkins voluntarily waived those rights; Hopkins did not request an attorney prior to or during his confession; and, under the totality of the circumstances, the statement was voluntary. The trial court also determined that Hopkins desired to terminate the interview on page 203 of the transcribed statement, and ruled that any subsequent statement was inadmissible. A jury trial was subsequently held and Hopkins was found guilty.

Hopkins challenged the admissibility of his confession on direct appeal. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals found that the trial court did err in admitting the first tape because the Miranda warnings were not on the tape as required by Texas law. However, the court found that this error was harmless because the references Hopkins made to the crime on the first tape would only raise issues of self-defense or temporary insanity and were presented or directly inferred through other evidence presented. Also, the court found that the record supported the trial court's findings that Hopkins voluntarily waived his rights on the second tape and that Hopkins' confession was neither coerced not involuntary.

Hopkins then brought this habeas action, which was filed on June 17, 1999, after the effective date of AEDPA. On September 28, 2001, the district court entered judgment denying habeas relief. Hopkins timely filed a notice of appeal, but on November 5, 2001, the district court denied Hopkins a COA. Hopkins then asked this Court to grant his application for a COA.

This Court granted Hopkins a COA on all three issues raised:

1. Whether his Fifth and Fourteenth Amendment rights to remain silent were violated by a law enforcement officer repeatedly coercing and lying to him;

2. Whether his Fifth and Fourteenth Amendment Due Process rights were violated when incriminating statements were obtained from him involuntarily; and

3. Whether his trial counsel was ineffective in representing him in violation of the Sixth Amendment.

* * *

Having carefully reviewed the parties' respective briefs and the record, we hold that the district court did not err in denying Hopkins habeas relief. Though we are troubled by the state's methods by which it obtained Hopkins' confession, ultimately, we conclude that its admission was harmless in light of the overwhelming amount of circumstantial evidence presented to the jury and the state's limited reliance on the confession. We also are unpersuaded by Hopkins' contention that his counsel was ineffective. Hopkins' counsel was operating under an objectively reasonable trial strategy in selecting the type of mitigating evidence that was presented. We therefore AFFIRM the district court's decision.

AFFIRMED.

12002 FM 350 South

Polunsky Unit - Livingston, Texas 77351 USA

Petitioner, Bobby Ray Hopkins, is currently confined on death row pursuant to a conviction of capital murder on May 25, 1994. After exhausting his state direct appeal and habeas corpus remedies, petitioner initiated a federal habeas corpus proceeding under 28 U.S.C. § 2254, which was filed on June 17, 1999, after the effective date of AEDPA. On September 28, 2001, the district court entered judgment denying habeas relief.

Hopkins asked this Court to grant a COA, raising three Constitutional issues. This Court granted Hopkins' application for a COA on all three issues.