Executed August 14, 2012 06:14 p.m. CDT by Lethal Injection in Oklahoma

27th murderer executed in U.S. in 2012

1304th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

4th murderer executed in Oklahoma in 2012

100th murderer executed in Oklahoma since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(27) |

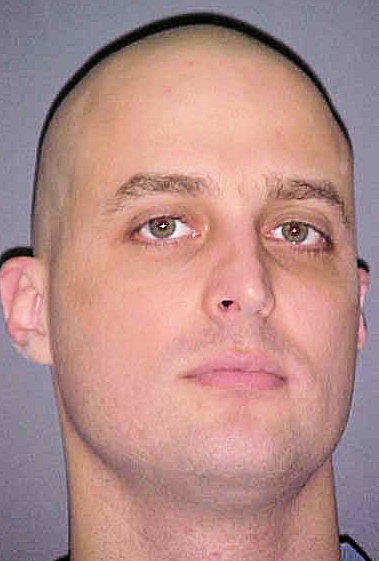

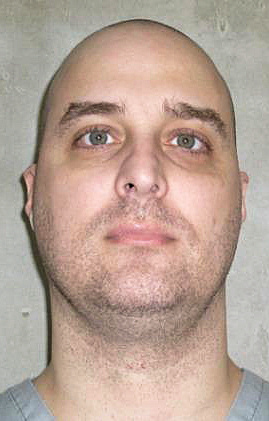

Michael Edward Hooper W / M / 21 - 39 |

Cynthia Lynn Roggy Jarman W / M / 23 Timothy Jarman W / M / 3 Tonya Jarman W / F / 5 |

Her Son Her Daughter |

10-27-04 |

Citations:

Hooper v. State, 947 P.2d 1090 (Okla.Crim. App. 1997). (Direct Appeal)

Hooper v. Turnbull, 957 P.2d 120 (Okl.Cr.App. 1998). (PCR)

Hooper v. State, 142 P.3d 463 (Okla.Crim.App. 2006). (Direct Appeal After Resentencing)

Hooper v. Mullin, 314 F.3d 1162 (10th Cir. 2002). (Habeas)

Hooper v. Workman, 446 Fed.Appx. 88 (10th Cir. 2011). (Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

A small cranberry juice, a small coffee, a small portion of blackberries, a small portion of cherries, strawberries, a peach, an apricot, a plum, a pear, an apple, a banana and an orange.

Final Words:

"I just want to thank God for such an exuberant send-off," he said as other death-row inmates banged their cell doors in a tribute to the condemned man. "Also, my family for standing by me throughout all this. I appreciate them being there for me through the hardships."Hooper did not directly speak to the victims' family members but indicated that he sought their forgiveness. "I ask that my spirit be released directly into the hands of Jesus. I'm ready to go. I love you all."

Internet Sources:

Oklahoma Department of Corrections

Inmate: MICHAEL E HOOPER

ODOC# 236125

Birth Date: 07/09/1972

Race: White

Sex: Male

Height: 6 ft. 4 in.

Weight: 175 pounds

Hair: Brown

Eyes: Grey

Convictions:

CASE# County Offense Conviction Term Start

93-601 CANA Murder First Degree 07/25/1995 DEATH Death

93-601 CANA Murder First Degree 07/25/1995 DEATH Death

93-601 CANA Murder First Degree 07/25/1995 DEATH Death

"Killer who fought execution is put to death," by Tim Talley. (Associated Press 8/15/2012 4:21 AM)

OKLAHOMA CITY - An Oklahoma death-row inmate who tried to delay his execution by challenging the state's lethal-injection method was executed Tuesday evening, just hours after the U.S. Supreme Court refused to step in. Michael Hooper, convicted of the December 1993 shooting deaths of his former girlfriend and her two young children, received a lethal dose of drugs at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester. Hooper, 40, was pronounced dead at 6:14 p.m., according to the Department of Corrections.

Hooper was sentenced to death for killing Cynthia Lynn Jarman, 23, and her two children, Tonya, 5, and Timmy, 3. Prosecutors said the victims were with Hooper in a pickup in a mowed field when he placed a 9 mm pistol under Cynthia Jarman's chin and shot her, then shot the children to prevent them from being witnesses. Each of the victims was shot twice in the head, and their bodies were buried in a shallow grave in a field northwest of Oklahoma City.

Strapped to a hospital gurney with intravenous tubes inserted into each of his arms Tuesday, Hooper spoke as his and his victims' relatives prepared to watch his execution through a window from separate rooms. "I just want to thank God for such an exuberant send-off," he said as other death-row inmates banged their cell doors in a tribute to the condemned man. "Also, my family for standing by me throughout all this. I appreciate them being there for me through the hardships."

Hooper did not directly speak to the victims' family members but indicated that he sought their forgiveness. "I ask that my spirit be released directly into the hands of Jesus. I'm ready to go," he said, then turned to family members, including his mother, brother and grandfather, and smiled as the drugs began to flow at 6:08 p.m. "I love you all," he said, then deeply exhaled and closed his eyes. Minutes later, he lay motionless.

The victims' family later issued a statement offering "our sincerest condolences" to Hooper's relatives. "This has been a long and arduous journey for all of the families," the statement said. "We hope to close this chapter in our lives."

Hooper had sued the state last month in an effort to halt his execution, claiming that Oklahoma's three-drug lethal injection protocol was unconstitutional. The lawsuit sought to force the state to have an extra dose of pentobarbital, a sedative, on hand during his execution. Pentobarbital is the first drug administered during lethal injections in Oklahoma and is used to render a condemned inmate unconscious. It's followed by vecuronium bromide, which stops the inmate's breathing, then potassium chloride to stop the heart. Hooper's attorney, Jim Drummond, had argued that if the sedative were ineffective, the remaining drugs could cause great pain in violation of the Eighth Amendment's prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

The lawsuit also noted that other states have adopted a one-drug process using a fast-acting barbiturate that supporters say causes no pain. But his request to stall the execution was rejected by a federal judge, then upheld by a federal appeals court. And the U.S. Supreme Court rejected Hooper's request without elaboration just hours before his execution.

Hooper was the fourth death-row inmate executed in Oklahoma this year. Gary Roland Welch was executed Jan. 5 for fatally stabbing Robert Dean Hardcastle, 35, in 1994 in a dispute over drugs in Miami, Okla. Timothy Stemple was executed March 15 for killing his wife, Trisha Stemple, by beating her with a baseball bat and running over her with a pickup alongside U.S. 75 near Jenks in 1996. Michael Selsor was put to death May 1 for the 1975 shooting death of Clayton Chandler, a 55-year-old Tulsa convenience store manager.

"Convicted murderer executed at OSP," by Rachel Petersen. (August 14, 2012)

McALESTER — An Oklahoma State Penitentiary death row inmate, convicted of three counts of murder, was executed this evening in the prison’s execution chamber. Michael Edward Hooper, 40, received his death sentence and was executed for the 1993 shooting murders of his ex-girlfriend, Cynthia Lynn Jarman, age 23, and her two children, Tanya Kay Jarman, age 5, and Timmy Glen Jarman, age 3.

At approximately noon today, Hooper was served his last meal: A small cranberry juice, a small coffee, a small portion of blackberries, a small portion of cherries, strawberries, a peach, an apricot, a plum, a pear, an apple, a banana and an orange.

When all witnesses were seated and able to see Hooper on the execution gurney, he turned his head and smiled at his family. OSP Acting Warden Art Lightle asked Hooper if he had any last words. “I just want to thank God for such an exuberant sendoff,” Hooper said. “Also my family for standing by me throughout all this. I appreciate them being there for me through the hardships. “I’d like to ask forgiveness for all those who need it — you know who you are. “I ask that my spirit be released directly into the hands of Jesus and I’m ready to go. “I love you all.” Hooper’s mother said, “Amen.”

And then at 6:08 p.m., Lightle then said, “Let the execution begin.” The witness room was silent as Hooper was administered the lethal injections. At 6:09 p.m., Hooper looked over at his family one last time and said, “I love you all,” as his eyes fluttered and then shut. At 6:14 p.m. the attending physician pronounced Hooper’s time of death. A clergy member, sitting next to Hooper’s mother, turned to her and said, “He’s at peace. When you have the assurance that Michael had, he was ready to go.” Witnessing the execution were 15 members of the victim’s family; Hooper’s mother, brother and two clergy representatives, four law enforcement representatives and two media witnesses, as well as employees from the Oklahoma Department of Corrections.

Hooper was the 183rd death row inmate to be executed in Oklahoma.

After the execution was complete, members of the victims’ family released a written statement: “We would like to offer our sincerest condolences to the family of Mr. Hooper. This has been a long and arduous journey for all of the families. We hope to close this chapter in our lives. Tonya, Timmy and Cindy will always be in our hearts and in our minds. They will forever be missed and loved deeply.”

"Oklahoma woman wants to witness inmate’s execution, but Corrections Department won’t let her; The stepmother of the two children murdered by Oklahoma death row inmate Michael Hooper will not get to see the condemned killer’s execution," by Andrew Knittle. (August 11, 2012)

Hooper, whose bid to delay his execution was denied by a federal judge last week, is scheduled to die by lethal injection Tuesday. The inmate was convicted of killing Cynthia Jarman, 23, and her two young children, Tonya and Timmy Jarman, in Canadian County nearly 20 years ago. The victims’ bodies were found Dec. 10, 1993, after days of searching.

Alicia Jarman, who had recently married the children’s father at the time of the murders, wants to watch Hooper die when he is executed by the state of Oklahoma. She believes doing so will bring her a sense of closure and could possibly improve her overall mental health. Justin Jones, director of the state Corrections Department, sent a letter to Jarman’s attorney in early July. The short letter indicates that Jarman would be allowed to attend Hooper’s execution. “Your request for Ms. Alicia Jarman, stepmother of the Jarman children, to attend the execution of Michael Hooper will be approved,” Jones wrote.

Lesley Smith March, director of the state attorney general’s victim services unit, said the Corrections Department decided not to allow Jarman to attend the execution after speaking with her ex-husband, James Jarman. Smith March said James Jarman “strenuously” objected to his ex-wife’s attending the execution. She said the Corrections Department decided that because Jarman wasn’t related by blood or marriage to any of the victims, she couldn’t attend. “Normally, we meet with the family during the clemency hearing,” Smith March said. “And that may have caused some of the problems in this case, because Hooper waived his clemency hearing.”

Alicia Jarman had known the children for two years before marrying their father, James Jarman. Cynthia Jarman and the children were murdered while Alicia Jarman and her new husband were on their honeymoon in Colorado. “When we got back from our honeymoon, we were going to go after custody of the children,” she said. “When we told Tonya we were getting married, on Thanksgiving, she was … very happy.”

Alicia Jarman, who was 19 at the time of the murders, said she has suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder since the violent deaths of Tonya and Timmy Jarman, who were 5 and 3 respectively. “I’m having massive stress because of not being able to go,” she said. “I’m not sleeping at night, and when I do sleep, I wake up screaming.” Alicia Jarman said her ex-husband opposes her attendance because of “back child support” he owes. The couple had a child in 1998 and divorced the same year. “He owes right around $150,000 in back child support,” Alicia Jarman said. “He’s never had anything to do with the child.”

It is the child support issue — and nothing else — that is driving James Jarman to block her attendance, she said. “Up until the last year, he had told me that he wouldn’t mind me going to the execution,” she said. “But now that I’ve pushed the contempt of court charges for him not paying the child support, he’s decided that he doesn’t want me to go.” James Jarman doesn’t deny that he owes the $150,000 in child support or that he’s never been a part of the child’s life. But he said that has nothing to do with his decision to exclude his ex-wife from the execution.

James Jarman said his ex-wife called him in 2008 and asked him if she could attend Hooper’s execution, and he told her she could. Things changed, however, and he had a change of heart. “Since that time, she’s gone to school and become a grief counselor. … She’s trying to put that on her resume,” he said. “She didn’t even allow my children to come to the wedding. … She’s never had anything to do with them whatsoever. “She’s not a part of this family; she never was. She never cared about those children.”

Alicia Jarman said simply knowing that Hooper is dead — if and when he is put to death — isn’t enough for her. Hooper, who was 21 at the time of the murders, tried to get a federal judge to delay his execution by questioning the supply of the state’s execution drug pentobarbital. The judge denied his attorney’s request for a preliminary injunction.

“You never, ever get closure from something like this — ever,” she said. “I want to watch him die, so that I can, afterwards, take a deep breath, let it out and say, ‘OK, it’s done.’ ” The murder of the young children was so traumatic, so life-changing, she said, that she pursued a career as a counselor to help others. “This has impacted every aspect of my life,” she said. “I’ve been dealing with this for half my life.”

"Oklahoma executes man who killed ex-girlfriend and her two children," by Steve Olafson. (Aug 14, 2012)

(Reuters) - A man convicted of killing his former girlfriend and her two young children in 1993 and burying them in a shallow grave was executed on Tuesday in Oklahoma after an unsuccessful last-ditch challenge to the state's three-drug execution protocol.

Michael Hooper, 39, was convicted of driving his ex-girlfriend Cynthia Jarman and her children, Timothy, 3, and Tonya, 5, to a field where he shot each of them twice in the head and then buried them in December 1993. Their bodies were found three days later. Police reports showed that Hooper and Jarman previously had been in a "physically violent relationship," the state attorney general's office said.

Hooper, who was the fourth person executed in Oklahoma this year and the 27th in the nation, was pronounced dead at 6:14 p.m. local time at the state prison in McAlester, a prison spokesman said. Hooper was first sentenced to death in 1995, but a federal appeals court overturned the sentence seven years later, ruling that his counsel had been ineffective. He waived his right to be sentenced by a jury at a new hearing. A judge re-imposed the death sentence in 2004.

Hooper had waived his right to appear before the state pardons and parole board, but last week attempted to block his execution by challenging the three-drug protocol used to execute condemned killers in Oklahoma. He had contended that the protocol used had the potential to cause great pain and was unconstitutional. A federal judge in Oklahoma City and a federal appeals court rejected his challenge. Earlier this year, Oklahoma was down to one dose of pentobarbital, one of three drugs the state uses to execute condemned inmates. It obtained 20 more doses since then, state prison spokesman Jerry Massie said.

The family members of Hooper's three victims released a statement that extended their condolences to Hooper's family. "This has been a long, arduous journey for all of the families," the statement said. "Tonya, Timmy and Cindy will always be in our hearts and our minds. They will forever be missed and loved deeply."

Hooper requested a variety of fruit along with cranberry juice and coffee for his last meal, Massie said. "I just want to thank God for such an excellent sendoff," Hooper said before the execution. "Also, my family, for standing by me throughout all this. I appreciate their being there for me through the hardships." Hooper also asked for forgiveness "for all those that need it - you know who you are." "I ask that my spirit be released directly into the hands of Jesus and I'm ready to go. I love you all."

Oklahoma Coalition to Abolish Death Penalty

Michael Edward Hooper met Cynthia Jarman in early 1992, and they dated through the summer of 1993. Their relationship was physically violent, and Hooper threatened to kill Cindy on several occasions. Cindy had called the police during their fights on more than one occasion. At one point, each had a victim's protective order against the other.

In July 1993, Cindy began dating Hooper's friend, Bill Stremlow. Hooper bought a Smith & Wesson 9mm pistol on July 15, 1993. During a traffic stop the next day the Oklahoma City Police Department [OCPD] confiscated the gun. The OCPD returned the gun on October 23, 1993, but kept the ammunition. Hooper went target shooting with friends in fields northwest of Oklahoma City the day he bought the gun and after it was returned. He took the gun when he worked out-of-state in late October and November and refused a co-worker's offer to buy it.

A day or two before the murders, Hooper showed a 9mm pistol to a neighbor. In November, three weeks before the murders, Cindy and her children began living with Stremlow. He told Cindy that Hooper was not welcome in their home. Before moving in with Stremlow, Cindy told a friend that Hooper had previously threatened to kill her if she ever lived with another man. On December 6, 1993, Cindy confided in a friend that she wanted to be with Hooper one last time and then stop seeing him.

On the morning of December 7, 1993, Cindy and her children dropped Stremlow off at work and Cindy borrowed his truck for the rest of the day. Cindy picked up her daughter, Tonya, at school at 3:30 that afternoon. At that time, Tonya's teacher saw Tonya get into Stremlow's truck next to a white man who was not Stremlow. Cindy failed to pick up Stremlow from work that evening as planned, and Stremlow never saw Cindy again. Cindy had Stremlow's only house key and he had to borrow his landlord's key to get in his house that night. Later that night, Stremlow's truck was found burning in a field in northwest Oklahoma City. The truck's windows were broken out. An accelerant had been used to set the truck on fire. Stremlow recovered the vehicle the next day.

When Stremlow returned to his house, although there were no signs of forced entry, a dresser drawer was disturbed, a Jim Beam whiskey bottle was on the dresser, and ten dollars in cash was missing. Hooper's fingerprints were later found on the Jim Beam bottle, and other evidence showed Hooper and Cindy drank that brand of whiskey. Cindy and her children were reported missing on December 9. Police attempted to interview Hooper; he failed to come to the station and denied seeing Cindy for the past six months. Hooper appeared nervous and had a fresh scratch on his arm. Also on December 9, an area rancher noticed damage to his gate leading to a northwest Oklahoma City field. Inside the field he found broken glass, tire tracks, a bloody sock and a pool of blood. After hearing the missing persons report, the rancher contacted police. The next day police searched the field and found broken glass, tire tracks, a footprint, shell casings, a child's bloody sock, a pool of blood near a tree with a freshly broken branch, a blue fiber near the tree, and a shallow grave site covered by limbs, leaves and debris. The grave appeared to be soaked with gasoline. Tonya, Timmy and Cindy were buried atop one another. Each victim had been shot twice in the head or face. There was a hole in the hood of Tonya's blue and purple jacket, and the white fiber lining protruded. A 9mm bullet pinned a white fiber to a branch on the grave. The branch appeared to have been broken from the tree near the pool of blood. The fibers were consistent with the white fibers in Tonya's jacket. Although investigators never recovered the bullets, the wounds were consistent with nine millimeter ammunition.

Police arrested Hooper and searched his parents' home. The police recovered a nine millimeter weapon Hooper had purchased several months prior to the murders. Police also recovered two shovels with soil consistent with soil from the grave site, two gas cans, and broken glass consistent with glass found in Tonya's coat and near the gate at the field. Police found a 9 mm bullet in Hooper's pocket. Police officers also seized Hooper's tennis shoes. The shoes made prints similar to those found at the murder scene, and DNA tests revealed the presence of blood consistent with Cindy's blood on the shoes. At trial, a ballistics expert testified that shell casings from the crime scene matched casings fired from Hooper's weapon. Hooper's former wife testified that Hooper was familiar with the field where the bodies were found, and that he previously had visited the field with her on several occasions.

Based on this evidence, the jury convicted Hooper of three counts of first degree murder. During the capital sentencing proceeding, the jury found two aggravating factors existed with respect to all three victims: (1) Hooper had created a great risk of death to more than one person, and (2) Hooper was a continuing threat to society. Additionally, the jury found a third aggravating factor existed with respect to Tonya Jarman: Hooper had committed the murder to avoid arrest or prosecution for the murder of Cynthia Jarman. After considering Hooper's mitigating evidence, the jury imposed the death sentence for each count.

UPDATE: It’s been almost 19 years since Barbie Jarman’s grandchildren were shot to death along with their 23-year-old mother, but she still has vivid memories of the children whom she described as so very, very precious. "The fact that they were murdered doesn’t lessen what they were to you,” Jarman said. “They still are very, very close to my heart. That doesn’t ever change.” For family members of the victims, Hooper’s execution will culminate a long journey that began with the trauma of learning about their violent deaths. “It’s not going to change what happened. But justice will be served,” said Diane Roggy, Cynthia Jarman’s mother and grandmother to her children. “The loss is still there. The pain never goes away,” said Cynthia’s sister, Renee Weber. “It will never be over, in my mind, until they close my casket,” Roggy said. Cynthia Jarman, a cosmetologist, “was just a beautiful person, full of life,” Weber said. “She was a very good mom. Timmy was a very bubbly little kid. He was just very playful,” she added. “Tonya was very smart.” The children’s uncle, Jeramy Jarman, said they “were amazing kids. These were my first experiences as an uncle. I was extremely proud. We had a lot of fun.” Jeramy Jarman said that after almost 19 years, he is ready for the case to come to an end. “This man is just an animal as far as I’m concerned."

Oklahoma Attorney General (News Release)

News Release

08/14/2012

Michael Edward Hooper - 6 p.m. Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester

Name: Michael Edward Hooper

DOB: 07/09/72

Sex: Male

Age at Date of Crime: 21

Victim(s): Cynthia Lynn Jarman, 23, Tonya Kay Jarman, 5, Timmy Glen Jarman, 3

Date of Crime: 12/07/93 (bodies discovered 12/10/93)

Date of Sentence: 07/25/95

Resentencing: 10/27/04

Crime Location: In a field near 164th and Morgan Road

Judge: Edward C. Cunningham (1st trial and re-sentencing)

Prosecuting: Cathy Stocker and Michael Gahan (1st trial and re-sentencing)

Defending: Mitchell Lee and Richard A. Krough (1st trial )

Mark Hendricksen and Julie Gardner (re-sentencing)

Circumstances Surrounding Crime:

Hooper was convicted and sentenced to death for the murders of his ex-girlfriend, Cynthia Lynn Jarman, 23, and her two children, Tonya Kay Jarman, 5, and Timmy Glen Jarman, 3, on Dec. 7, 1993. Hooper drove Jarman and her children to a field in Canadian County where he shot Jarman twice, and then shot her son, Timmy, twice in the head. Five-year-old Tonya witnessed the shootings and escaped from the truck. Hooper chased her through the woods, firing once, missing the girl. Hooper caught up with Tonya and shot her twice in the head. Police found all three bodies in a shallow grave. The victims had been missing for several days before being discovered. Police records, including domestic violence reports, show that Hooper and Jarman had previously been in a physically violent relationship.

The federal court determined Hooper’s counsel provided ineffective assistance during the punishment stage of his trial and overturned the death sentences. In a 2004 hearing, Hooper was once again sentenced to death.

Statement from Attorney General Scott Pruitt: “Michael Hooper was found guilty by a jury of his peers and given the death sentence for ending the lives of a young mom and her two innocent children,” Attorney General Scott Pruitt said. “My thoughts are with the families of Cynthia, Tonya and Timmy for what they have endured for nearly 20 years.”

Wikipedia: Oklahoma Executions

A total of 98 individuals convicted of murder have been executed by the State of Oklahoma since 1976, all by lethal injection:

1. Charles Troy Coleman 10 September 1990 John Seward

2. Robyn Leroy Parks 10 March 1992 Abdullah Ibrahim

3. Olan Randle Robinson 13 March 1992 Shiela Lovejoy, Robert Swinford

4. Thomas J. Grasso 20 March 1995 Hilda Johnson

5. Roger Dale Stafford 1 July 1995 Melvin Lorenz, Linda Lorenz, Richard Lorenz, Isaac Freeman, Louis Zacarias, Terri Horst, David Salsman, Anthony Tew, David Lindsey

6. Robert Allen Brecheen [1][2][3] 11 August 1995 Marie Stubbs

7. Benjamin Brewer 26 April 1996 Karen Joyce Stapleton

8. Steven Keith Hatch 9 August 1996 Richard Douglas, Marilyn Douglas

9. Scott Dawn Carpenter 7 May 1997 A.J. Kelley

10. Michael Edward Long 20 February 1998 Sheryl Graber, Andrew Graber

11. Stephen Edward Wood 5 August 1998 Robert B. Brigden

12. Tuan Anh Nguyen 10 December 1998 Amanda White, Joseph White

13. John Wayne Duvall 17 December 1998 Karla Duvall

14. John Walter Castro 7 January 1999 Beulah Grace, Sissons Cox, Rhonda Pappan

15. Sean Richard Sellers 4 February 1999 Paul Bellofatto, Vonda Bellofatto, Robert Bower

16. Scotty Lee Moore 3 June 1999 Alex Fernandez

17. Norman Lee Newsted 8 July 1999 Larry Buckley

18. Cornel Cooks 2 December 1999 Jennie Elva Ridling

19. Bobby Lynn Ross 9 December 1999 Steven Mahan

20. Malcolm Rent Johnson 6 January 2000 Ura Alma Thompson

21. Gary Alan Walker 13 January 2000 Eddie O. Cash, Valerie Shaw-Hartzell, Jane Hilburn, Janet Jewell, Margaret Bell Lydick, DeRonda Gay Roy

22. Michael Donald Roberts 10 February 2000 Lula Mae Brooks

23. Kelly Lamont Rogers 23 March 2000 Karen Marie Lauffenburger

24. Ronald Keith Boyd 27 April 2000 Richard Oldham Riggs

25. Charles Adrian Foster 25 May 2000 Claude Wiley

26. James Glenn Rodebeaux 1 June 2000 Nancy Rose Lee McKinney

27. Roger James Berget 8 June 2000 Rick Lee Patterson

28. William Clifford Bryson 15 June 2000 James Earl Plantz

29. Gregg Francis Braun 10 August 2000 Gwendolyn Sue Miller, Barbara Kchendorfer, Mary Rains, Pete Spurrier, Geraldine Valdez

30. George Kent Wallace 10 August 2000 William Von Eric Domer, Mark Anthony McLaughlin

31. Eddie Leroy Trice 9 January 2001 Ernestine Jones

32. Wanda Jean Allen 11 January 2001 Gloria Jean Leathers

33. Floyd Allen Medlock 16 January 2001 Katherine Ann Busch

34. Dion Athansius Smallwood 18 January 2001 Lois Frederick

35. Mark Andrew Fowler 23 January 2001 John Barrier, Rick Cast, Chumpon Chaowasin

36. Billy Ray Fox 25 January 2001

37. Loyd Winford Lafevers 30 January 2001 Addie Mae Hawley

38. Dorsie Leslie Jones, Jr. 1 February 2001 Stanley Eugene Buck, Sr.

39. Robert William Clayton 1 March 2001 Rhonda Kay Timmons

40. Ronald Dunaway Fluke 27 March 2001 Ginger Lou Fluke, Kathryn Lee Fluke, Suzanna Michelle Fluke

41. Marilyn Kay Plantz 1 May 2001 James Earl Plantz

42. Terrance Anthony James 22 May 2001 Mark Allen Berry

43. Vincent Allen Johnson 29 May 2001 Shirley Mooneyham

44. Jerald Wayne Harjo 17 July 2001 Ruther Porter

45. Jack Dale Walker 28 August 2001 Shely Deann Ellison, Donald Gary Epperson

46. Alvie James Hale, Jr. 18 October 2001 William Jeffery Perry

47. Lois Nadean Smith 4 December 2001 Cindy Baillee

48. Sahib Lateef Al-Mosawi 6 December 2001 Inaam Al-Nashi, Mohamed Al-Nashi

49. David Wayne Woodruff 21 January 2002 Roger Joel Sarfaty, Lloyd Thompson

50. John Joseph Romano 29 January 2002

51. Randall Eugene Cannon 23 July 2002 Addie Mae Hawley

52. Earl Alexander Frederick, Sr. 30 July 2002 Bradford Lee Beck

53. Jerry Lynn McCracken[10] 10 December 2002 Tyrrell Lee Boyd, Steve Allen Smith, Timothy Edward Sheets, Carol Ann McDaniels

54. Jay Wesley Neill 12 December 2002 Kay Bruno, Jerri Bowles, Joyce Mullenix, Ralph Zeller

55. Ernest Marvin Carter, Jr. 17 December 2002 Eugene Mankowski

56. Daniel Juan Revilla 16 January 2003 Mark Gomez Brad Henry

57. Bobby Joe Fields 13 February 2003 Louise J. Schem

58. Walanzo Deon Robinson 18 March 2003 Dennis Eugene Hill

59. John Michael Hooker 25 March 2003 Sylvia Stokes, Durcilla Morgan

60. Scott Allen Hain 3 April 2003 Michael William Houghton, Laura Lee Sanders

61. Don Wilson Hawkins, Jr. 8 April 2003 Linda Ann Thompson

62. Larry Kenneth Jackson 17 April 2003 Wendy Cade

63. Robert Wesley Knighton 27 May 2003 Richard Denney, Virginia Denney

64. Kenneth Chad Charm 5 June 2003 Brandy Crystian Hill

65. Lewis Eugene Gilbert II 1 July 2003 Roxanne Lynn Ruddell

66. Robert Don Duckett 8 July 2003 John E. Howard

67. Bryan Anthony Toles 22 July 2003 Juan Franceschi, Lonnie Franceschi

68. Jackie Lee Willingham 24 July 2003 Jayne Ellen Van Wey

69. Harold Loyd McElmurry III 29 July 2003 Rosa Vivien Pendley, Robert Pendley

70. Tyrone Peter Darks 13 January 2004 Sherry Goodlow

71. Norman Richard Cleary 17 February 2004 Wanda Neafus

72. David Jay Brown 9 March 2004 Eldon Lee McGuire

73. Hung Thanh Le 23 March 2004 Hai Hong Nguyen

74. Robert Leroy Bryan 8 June 2004 Mildred Inabell Bryan

75. Windel Ray Workman 26 August 2004 Amanda Hollman

76. Jimmie Ray Slaughter 15 March 2005 Melody Sue Wuertz, Jessica Rae Wuertz

77. George James Miller, Jr. 12 May 2005 Gary Kent Dodd

78. Michael Lannier Pennington 19 July 2005 Bradley Thomas Grooms

79. Kenneth Eugene Turrentine 11 August 2005 Avon Stevenson, Anita Richardson, Tina Pennington, Martise Richardson

80. Richard Alford Thornburg, Jr. 18 April 2006 Jim Poteet, Terry Shepard, Kevin Smith

81. John Albert Boltz 1 June 2006 Doug Kirby

82. Eric Allen Patton 29 August 2006 Charlene Kauer

83. James Patrick Malicoat 31 August 2006 Tessa Leadford

84. Corey Duane Hamilton 9 January 2007 Joseph Gooch, Theodore Kindley, Senaida Lara, Steven Williams

85. Jimmy Dale Bland 26 June 2007 Doyle Windle Rains

86. Frank Duane Welch 21 August 2007 Jo Talley Cooper, Debra Anne Stevens

87. Terry Lyn Short[4] 17 June 2008 Ken Yamamoto

88. Jessie Cummings 25 September 2008 Melissa Moody

89. Darwin Brown 22 January 2009 Richard Yost

90. Donald Gilson 14 May 2009 Shane Coffman

91. Michael DeLozier 9 July 2009 Orville Lewis Bullard, Paul Steven Morgan

92. Julius Ricardo Young 14 January 2010 Joyland Morgan, Kewan Morgan

93. Donald Ray Wackerly II 14 October 2010 Pan Sayakhoummane

94. John David Duty 16 December 2010 Curtis Wise

95. Billy Don Alverson 6 January 2011 Richard Kevin Yost

96. Jeffrey David Matthews 11 January 2011 Otis Earl Short Mary Fallin

97. Gary Welch 5 January 2012 Robert Dean Hardcastle

98. Timothy Shaun Stemple 15 March 2012 Trisha Stemple

99. Michael Bascum Selsor 1 May 2012 Clayton Chandler

100. Michael E. Hooper 14 August 2012 Cynthia Jarman, Timothy Jarman, Tonya Jarman

Hooper v. State, 947 P.2d 1090 (Okla.Crim. App. 1997). (Direct Appeal)

Defendant was convicted in the District Court, Canadian County, Edward C. Cunningham, J., of three counts of murder in the first degree, and was sentenced to death. Defendant appealed. The Court of Criminal Appeals, Chapel, P.J., held that: (1) police officer's affidavits were sufficient to support arrest and search warrants; (2) evidence regarding prior traffic stop of defendant was admissible; (3) defendant invited testimony concerning his violent relationship with his ex-wife; (4) evidence concerning defendant's fight with victim and his threats towards victim were admissible under state of mind exception to hearsay rule; (5) evidence was sufficient to support conviction; (6) victim impact evidence was properly admitted; (7) great risk of death to more than one person aggravating circumstance could apply to multiple murder; (8) evidence supported avoiding or preventing lawful arrest or prosecution aggravating circumstance; (9) defendant was not denied effective assistance of counsel; and (10) death sentence was appropriate. Affirmed. Lane, J., filed opinion concurring in result. Lumpkin, J., concurred in result.

CHAPEL, Presiding Judge.

Michael Edward Hooper was tried by a jury and convicted of three counts of Murder in the First Degree, in violation of 21 O.S.1991, § 701.7(A), in the District Court of Canadian County, Case No. CF–93–601. On Counts I and III the jury found Hooper knowingly created a great risk of death to more than one person and probably would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society; on Count II, that Hooper knowingly created a great risk of death to more than one person, probably would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society, and committed the murder in order to avoid or prevent a lawful arrest or prosecution. In accordance with the jury's recommendation, the Honorable Edward C. Cunningham sentenced Hooper to death on each count. Hooper has perfected his appeal of these convictions and sentences and raises sixteen propositions of error. After thorough consideration of the entire record before us on appeal including the original record, transcripts, briefs and exhibits of the parties, we find that neither reversal nor modification is required under the law and evidence. We affirm Hooper's Judgments and Sentences.

Hooper was convicted of killing his ex-girlfriend Cynthia Jarman [Cindy] and her two children, five-year-old Tonya and three-year-old Timmy. Hooper and Cindy met in 1992 and dated through the summer of 1993. On more than one occasion the couple fought and Cindy called police. At one point each had a victim's protective order against the other. Several times Hooper threatened to kill Cindy. In October or November, 1993, Cindy and her children moved in with Bill Stremlow. He told Cindy that Hooper was not welcome in their home. On December 6, 1993, Cindy told a friend she wanted to be with Hooper one last time and then stop seeing him.

Hooper bought a Smith & Wesson 9mm pistol on July 15, 1993. During a traffic stop the next day the Oklahoma City Police Department [OCPD] confiscated the gun. The OCPD returned the gun on October 23, 1993, but kept the ammunition. Hooper went target shooting with friends in fields northwest of Oklahoma City the day he bought the gun and after it was returned. He took the gun when he worked out-of-state in late October and November and refused a co-worker's offer to buy it. On December 6 or 7, 1993, Hooper showed a 9mm pistol to a neighbor.

On December 7, 1993, Cindy and her children drove Stremlow to work and borrowed his truck. Tonya got out of school at 3:30 p.m. Cindy was about fifteen minutes late to pick up Tonya; Tonya's teacher saw her get in Stremlow's truck next to a white male who was not Stremlow. Cindy failed to pick up Stremlow after work and he never saw her again; Cindy had Stremlow's only house key and he had to borrow his landlord's key to get in his house that night. Stremlow's truck was found burning in a field in northwest Oklahoma City the night of December 7. He recovered it the next day. Accelerant, probably gasoline, had been used to set the truck on fire and the windows were broken out. Stremlow returned to his house December 10; although there were no signs of forced entry, a dresser drawer was disturbed, a Jim Beam whiskey bottle was on the dresser, and ten dollars in cash was missing. Hooper's fingerprints were on the Jim Beam bottle, and other evidence showed Hooper and Cindy drank that brand of whiskey.

Cindy and her children were reported missing on December 9. Police attempted to interview Hooper; he failed to come to the station and denied seeing Cindy for the past six months. Hooper appeared nervous and had a fresh scratch on his arm. Also on December 9, an area rancher noticed damage to his gate leading to a northwest Oklahoma City field. Inside the field he found broken glass, tire tracks, a bloody sock and a pool of blood. After hearing the missing persons report, the rancher contacted police. The next day police searched the field and found broken glass, tire tracks, a footprint, shell casings, a child's bloody sock, a pool of blood near a tree with a freshly broken branch, a blue fiber near the tree, and a grave site covered by limbs, leaves and debris. The grave appeared to be soaked with gasoline. Tonya, Timmy and Cindy were buried atop one another. Each victim had been shot twice in the head. There was a hole in the hood of Tonya's blue and purple jacket, and the white fiber lining protruded. A 9mm bullet pinned a white fiber to a branch on the grave. The branch appeared to have been broken from the tree near the pool of blood.

Police arrested Hooper and searched his parents' house. They found the 9mm pistol, two shovels with soil consistent with soil from the grave site, two gas cans, and broken glass consistent with glass found in Tonya's coat and near the gate. Police found a 9mm bullet in Hooper's pocket. His shoe print was similar to the footprint at the scene and DNA evidence showed blood on Hooper's shoes was consistent with Cindy's blood. Shell casings found where Hooper went target shooting matched bullets shot from his gun and casings found at the crime scene. In the past, Hooper and his ex-wife Stefanie Duncan had regularly visited the field where the bodies were found.

PRETRIAL ISSUES

Hooper argues in his first two propositions that the affidavits supporting the arrest and search warrants were insufficient, and the evidence seized through those warrants should have been suppressed. Hooper has waived review of all but plain error. He neither challenged his arrest nor moved to suppress evidence obtained as a result of his arrest. Failure to raise a timely objection to the legality of an arrest before entering a plea waives review.FN1 Hooper also failed to move to quash the search warrant or suppress the evidence seized under the search warrant; nor did he object when that evidence was introduced at trial. On review, this Court will determine whether the magistrate had a substantial basis for concluding probable cause existed to believe Hooper committed the crimes, looking at the totality of the circumstances contained in the affidavits supporting the warrants.FN2 A review of the affidavit as a whole may give sufficient reason to consider the information in the affidavit credible.FN3 Affidavits are presumed valid. Where an affidavit is expressed in positive terms, a defendant may not go behind that language to show the officer did not have knowledge of the allegations set forth.FN4 To challenge the substance of an affidavit Hooper must establish by a preponderance of the evidence that the affiant committed perjury or acted with reckless disregard for the truth.FN5

FN1. Clayton v. State, 840 P.2d 18, 28 (Okl.Cr.1992), cert. denied, 507 U.S. 1008, 113 S.Ct. 1655, 123 L.Ed.2d 275 (1993); Raymer v. City of Tulsa, 595 P.2d 810, 812 (Okl.Cr.1984). FN2. Langham v. State, 787 P.2d 1279, 1281–82 (Okl.Cr.1990); Illinois v. Gates, 462 U.S. 213, 103 S.Ct. 2317, 76 L.Ed.2d 527 (1983). FN3. Sockey v. State, 676 P.2d 269, 270 (Okl.Cr.1984). FN4. Martin v. State, 804 P.2d 1143, 1145 (Okl.Cr.1991); Franks v. Delaware, 438 U.S. 154, 172, 98 S.Ct. 2674, 2684, 57 L.Ed.2d 667 (1978). FN5. Martin, 804 P.2d at 1145.

In Proposition I Hooper alleges the arrest warrant was defective because the facts set forth in the affidavit did not establish probable cause that he committed the crimes. On December 13, 1993, Canadian County issued a warrant for Hooper, and police arrested him at his parent's home. After the arrest, police seized Hooper's tennis shoes and a 9mm bullet found in his pocket, and photographed a scratch on Hooper's arm. The shoes were later compared to a footprint at the scene, and DNA testing determined blood on one shoe was probably Cindy's. The affidavit accompanying the warrant includes the following information: (1) Hooper was arrested on July 16, 1993 for possession of a Smith & Wesson 9mm handgun, which was released to him on October 29, 1993 (while the OCPD Property Room retained the ammunition); (2) the victims' bodies dead of multiple gunshot wounds were discovered in a grave in Canadian County on December 12, 1993, and 9mm casings and a bullet were discovered near the grave; (3) the 9mm casings matched the casings from the OCPD property room; (4) Hooper was Cindy's ex-boyfriend and had been violent towards her; (5) Hooper, in the course of the missing persons investigation, declined to speak to officers on the advice of counsel; FN6 and (6) on December 6 or 7, Hooper showed a witness a 9mm semi-automatic handgun. FN6. At trial the evidence that Hooper refused to talk on the advice of counsel was not admitted.

Hooper first claims the magistrate could not have found this affidavit sufficient because it (a) neither includes the source of the allegations in item No. 4 nor indicates that the information was within the affiant's personal knowledge; (b) does not name the interviewing officers in item No. 5; and (c) neither alleges whether an informant existed nor indicates a record of reliability. A review of the entire affidavit shows these complaints are without merit. The affidavit begins by stating “the facts known to the affiant”, and thus on its face does not indicate that an informant gave the information to Officer Presley. Officer Presley's failure to name the interviewing officers alleged to have spoken to Hooper is not fatal, since the magistrate had a basis for determining the veracity and reliability of law enforcement officers. Taken as a whole, the affidavit provides enough information to form a substantial basis for probable cause. There is no plain error here.

Hooper next complains that item No. 3 was incorrect in averring the site shell casings matched the property room casings, that the statement was reckless, and that Officer Presley knew or should have known the statement was false since the OCPD bullets had not been fired and thus had no casings to compare. Hooper does not establish that Officer Presley either committed perjury or acted with a reckless disregard for the truth. He suggests that Officer Presley must have known there could be no forensic match with the bullets in the Oklahoma City Police Department property room because those bullets had not been fired. No evidence supports this assertion. The record before us shows the casings found at the scene were compared with casings found where Hooper practiced target shooting, and, later, with a casing from a bullet the examiner fired from Hooper's gun. Hooper claims that the live rounds in the property room could not have matched any casings, because the live rounds could not have had extractor marks to compare with marks on the casings. Nothing in the record supports this assertion. Officer Presley set forth facts he believed true. At best this shows Officer Presley made a good faith mistake acting on reliable information. Hooper's assertion that Presley must have known the casings had not been matched to Hooper's gun does not establish perjury or reckless disregard. Given all the circumstances set forth in the affidavit including the veracity and basis of knowledge of the person supplying hearsay information, the magistrate had a substantial basis for concluding there was probable cause for Hooper's arrest.FN7 We find no plain error in the magistrate's failure to suppress the evidence from Hooper's arrest, and this proposition is denied. FN7. Langham, 787 P.2d at 1281.

In Proposition II Hooper argues the search warrant was defective. Officers served a search warrant at the same time Hooper was arrested, and seized items including Hooper's 9mm pistol, two shovels, gas cans, and broken glass. Oklahoma County issued the warrant with a separate affidavit from Officer Presley. Reviewing the affidavit under the totality of the circumstances test, we find the magistrate did not commit plain error.FN8 FN8. Langham, 787 P.2d at 1281.

Hooper claims a) that the affidavit does not provide indicia of reliability for either informant allegations or forensic conclusions, b) that the affidavit contains irrelevant evidence, c) that the information regarding forensic comparison was questionable, and d) that each individual charge in the warrant is insufficient to support probable cause. The affidavit initially avers that Officer Presley had personal knowledge of the facts and circumstances related through his own investigation as well as that of other officers named in the affidavit who told him their findings. This statement provides sufficient indicia of reliability and personal knowledge, as the magistrate had a basis for determining the veracity and reliability of law enforcement officers. All informants are named and their relationship to Hooper is described, so Hooper's first argument must fail.FN9 Although Hooper claims the evidence of Stremlow's house burglary is irrelevant, that evidence further connects Hooper to the victims. Hooper again argues the forensic evidence was questionable because the bullets in the OCPD property room were never fired and thus casings could not be compared. The record does not support this assertion. Presley apparently recited information given to him by reliable sources and which he believed to be true. Given the totality of circumstances in the affidavit the magistrate did not err in admitting evidence seized pursuant to the search warrant. There is no plain error and this proposition should be denied. FN9. Newton v. State, 824 P.2d 391, 393 (Okl.Cr.1991).

ISSUES RELATING TO GUILT OR INNOCENCE

In Proposition III Hooper argues the trial court improperly admitted three separate categories of evidence he claims contain other crimes or bad acts. Hooper objected to some of this evidence, preserving some issues for appeal. A defendant should be convicted, if at all, by evidence of the charged offenses, but other crimes evidence may be admissible to prove motive, opportunity, intent, preparation, plan, knowledge, identity or absence of mistake or accident.FN10 The evidence was offered to show identity, continuous possession of the murder weapon, and motive or intent. Any errors in admission of this evidence do not require reversal or modification. FN10. Burks v. State, 594 P.2d 771 (Okl.Cr.1979), overruled in part on other grounds by Jones v. State, 772 P.2d 922 (Okl.Cr.1989); 12 O.S.1991, § 2404(B).

In Subproposition A Hooper complains about admission of evidence derived from a July 16, 1993 traffic stop. Hooper bought a 9mm pistol on July 15, 1993. On July 16, Officer Reagor arrested Hooper for an invalid inspection sticker and stolen license tags. Reagor confiscated the gun, which was returned to Hooper on October 29. Cindy was with Hooper during the traffic stop and a bottle of Jim Beam was in the car. The State filed a Burks notice and offered this evidence to show identification and to prove Hooper had continuous and exclusive possession of the gun. The trial court overruled Hooper's motion in limine to prevent this evidence three times before the evidence was presented; the court ruled possession of the loaded murder weapon was relevant to intent, ownership and possession, and that the probative value of that evidence outweighed its prejudicial effect. Hooper was granted a continuing objection to Officer Reagor's testimony and all evidence of the traffic stop.

At an in camera hearing the trial court found the stop was valid, then ruled Hooper's possession of the murder weapon was relevant and the Jim Beam bottle went to identification because it corroborated other testimony that Hooper drank Jim Beam. The court held that the reason for the stop—the inspection sticker and stolen tags—and whether the whiskey bottle was open were not relevant to this case. Officer Reagor testified that he stopped Hooper and confiscated the loaded gun, that Cindy was in the car, and that there was a Jim Beam bottle.

Hooper argues this evidence interjected evidence of other crimes and bad acts and was more prejudicial than probative. He complains that the evidence was not necessary to show continuous, exclusive possession. On the contrary, the trial court correctly found that Hooper's possession of the murder weapon was relevant to the crime and necessary to complete the State's proof that Hooper possessed the gun continuously since its purchase, exclusive of the time in which it was confiscated. Hooper complains that the evidence did not establish a modus operandi or peculiar facts which would create a signature. This requirement goes specifically to other crimes evidence offered to prove knowledge and intent, and does not apply to the evidence here.FN11 Hooper claims that the evidence was not necessary to show his connection with Cindy, and the fact the loaded gun was found under her seat gave the evidence a sinister overtone. Hooper also claims the evidence of the Jim Beam bottle was irrelevant and inferred prior bad acts. Since no evidence was presented on the topic, he argues the jury must have inferred the bottle was open. We find no error in inferences apparent only to defense counsel. Hooper also argues the trial court erred in admitting the Jim Beam bottle when the State originally only offered testimony about the gun. Other evidence showed that Cindy and Hooper drank Jim Beam whiskey, that after the crimes Hooper's fingerprints were found on a Jim Beam bottle in Stremlow's house, and that Hooper was not welcome at Stremlow's house. Evidence of the Jim Beam bottle was relevant to corroborate other evidence and connect Hooper to the victims near the time of the crime. The trial court did not abuse its discretion in admitting this evidence. FN11. Blakely v. State, 841 P.2d 1156, 1159 (Okl.Cr.1992).

Hooper now complains that the jury never heard why he was stopped, inferring trial counsel erred in agreeing to establish the validity of the stop outside the presence of the jurors.FN12 He argues that no reasonable juror would believe that Hooper was stopped for an inspection sticker violation, so the omission of that evidence left a worse impression than if the evidence of the other crime had been admitted. Strictly speaking, Hooper wants this Court to rule the trial court erred in excluding evidence of other crimes. We decline; the evidence of the inspection sticker and stolen license tags was not relevant to this case. FN12. Hooper does not include this allegation in his proposition claiming ineffective assistance of trial counsel.

Hooper argues in Subproposition B that the trial court erred in admitting Stefanie Duncan's testimony about her relationship with Hooper. In the first stage Duncan, Hooper's ex-wife, testified that in 1989 she and Hooper often went to the field where the victims were found. Before Duncan's testimony Hooper objected to any evidence of bad acts, and the prosecutor stated Duncan would only testify about the location of the field. On cross-examination, Hooper brought out that the two had only been married for eight months. When he asked about the grounds for divorce Duncan replied the couple had a violent history. Hooper ceased questioning and the State declined redirect examination. Then Hooper reopened cross-examination to ask who filed for divorce. Duncan replied Hooper had filed. On redirect, Hooper objected when the State asked who in the relationship had been violent. The trial court allowed the answer, ruling that Hooper had opened the door to this testimony by implying that Duncan had been violent. Duncan testified Hooper had physically abused her and tried to kill her several times.

Hooper invited this error when he left the clear and erroneous impression that Duncan's violent behavior caused Hooper to file for divorce. Hooper is not entitled to relief from this invited error.FN13 Hooper attempts to avoid this result by characterizing Duncan's testimony as an evidentiary harpoon. Evidentiary harpoons are typically delivered by experienced police officers, and are voluntary, willful injections of other crimes calculated to prejudice the defendant and which do actually prejudice him.FN14 A witness other than an experienced police officer may occasionally deliver an evidentiary harpoon, but Duncan's evidence does not qualify. Her testimony was delivered in direct response to questioning; defense questions prompted it; and it was neither calculated to prejudice Hooper nor did it actually prejudice him given the other evidence against him. FN15 The trial court did not err in admitting this testimony.

FN13. Pierce v. State, 786 P.2d 1255, 1259 (Okl.Cr.1990). FN14. Bruner v. State, 612 P.2d 1375, 1378 (Okl.Cr.1980). Even an actual evidentiary harpoon may not be prejudicial if a defendant invites the error. Rogers v. State, 890 P.2d 959, 972 (Okl.Cr.), cert. denied, 516 U.S. 312, 116 S.Ct. 312, 133 L.Ed.2d 215 (1995). FN15. Bruner, 612 P.2d at 1378–79.

Hooper argues counsel's questions to Duncan amounted to ineffective assistance of counsel. Hooper must show counsel's performance was so deficient he did not have counsel as guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment, and his defense was prejudiced as a result of counsel's deficient performance by errors so serious as to deprive him of a fair trial with reliable results.FN16 This Court need not reach the first prong of this test as Hooper fails to meet the second prong. The record suggests counsel attempted to show Duncan was violent and biased against Hooper, a reasonable strategic decision. Hooper fails to show that counsel's questions prejudiced him. Hooper also claims that the prosecutor committed misconduct when she repeated Duncan's evidence and commented on Hooper's history and capacity for violence towards women. Hooper did not object to this comment and has waived all but plain error. There was no error as this was a reasonable comment on the evidence presented at trial. FN16. Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 687, 104 S.Ct. 2052, 2064, 80 L.Ed.2d 674, 693 (1984).

Hooper argues in Subproposition C that the trial court erred in admitting evidence that Stremlow's house was burglarized after the murders. Stremlow and Officer Harlow testified that Stremlow spent the night at home on December 7, left, and returned to his house on December 10. Although there was no forced entry, dresser drawers were disturbed, ten dollars was missing, and a Jim Beam bottle bearing Hooper's fingerprints was on the dresser. Stremlow had told Cindy not to let Hooper visit their house. Stremlow had his landlord's key. The only other house key had been on his key ring with the truck key and was missing. The State filed a second Burks notice offering this evidence to prove identity. Hooper objected vigorously to this evidence and has preserved the issue for review. The trial court ruled evidence of the burglary was relevant to show date, time and location.

Hooper argues since Stremlow spent one night at home before discovering the burglary, the bottle could not have been there before Cindy's death. He claims this evidence has no probative value and was only offered to show his bad character. While this testimony inferred Hooper committed burglary, it connected Hooper to the victims and the location. His fingerprints suggested that Hooper had been in the house, and the absence of evidence of forced entry suggested that whoever entered used the key from the truck key ring. The trial court did not err in admitting this evidence. Despite Hooper's claim, the trial court did not err in admitting evidence of the July 16, 1993 traffic stop or the burglary at Stremlow's house. Additionally, Hooper opened the door to Duncan's comments about their relationship and he is not entitled to relief on that ground. Proposition III is denied.

In Proposition IV Hooper argues the trial court erred in admitting portions of Brett Blanton's testimony. Hooper claims Blanton's comments were irrelevant under 12 O.S.1991, § 2402, and, if relevant, were more prejudicial than probative. Brett Blanton worked with Hooper during the autumn of 1993, and they shared a room when working in Illinois. Blanton testified that Hooper had a 9mm semiautomatic pistol, often went target shooting, cleaned the gun often, and slept with it nearby. Once Hooper fell asleep holding the loaded gun and Blanton had to take it away. Hooper refused Blanton's offers to buy the pistol. Hooper was granted a continuing objection to this evidence. The State offered it to show continuous and exclusive possession of the pistol and to negate the argument that Hooper might have loaned his gun to someone else who committed the murders. The trial court allowed limited testimony for that purpose. Hooper argues this could have been achieved without admitting evidence that he constantly held the gun and slept with it nearby. He suggests that, taken as a whole, Blanton's testimony showed Hooper was obsessed with his gun and that the testimony was offered to attack his character.

Relevant evidence is that which has any tendency to make more or less probable a material fact in issue.FN17 The admissibility of evidence is within the trial court's discretion and this Court will not disturb that decision absent a clear showing of abuse.FN18 Relevancy depends on the issues to be proved at trial.FN19 The State's case against Hooper was entirely circumstantial, and the State had to prove Hooper used the 9mm pistol to commit the crimes. Blanton's evidence established that Hooper possessed the gun from October 29 through November, was very attached to it, and refused to sell it. This is relevant to the issues of possession of the murder weapon and Hooper's identity as the murderer. Any inference that Hooper was obsessed with the pistol cannot have prejudiced him in light of the evidence of his violent history with Cindy and other evidence showing he was at the crime scene. Hooper has not shown that the prejudicial effect of Blanton's testimony substantially outweighs its probative value.FN20 This proposition is denied.

FN17. 12 O.S.1991, § 2401. FN18. Robedeaux v. State, 866 P.2d 417, 432 (Okl.Cr.1993), cert. denied, 513 U.S. 833, 115 S.Ct. 110, 130 L.Ed.2d 57 (1994). FN19. Hawkins v. State, 891 P.2d 586, 593 (Okl.Cr.1994), cert. denied, 516 U.S. 977, 116 S.Ct. 480, 133 L.Ed.2d 408 (1995). FN20. 12 O.S.1991, § 2403.

In Proposition XIII Hooper claims the trial court erred in admitting hearsay evidence about a previous fight with Cindy. Two police officers testified about conversations with Cindy and Hooper after the two fought on February 19, 1992. Hooper objected to this evidence and has preserved the issue for review. Any error in admission of this evidence was harmless.

Officer Abrahamson testified that Cindy reported a February 19, 1992 fight during which Hooper pulled the phone out of the wall, pushed and choked her, and threatened to kill her. Officer Abrahamson said Cindy appeared angry and upset. The trial court admitted this evidence as an excited utterance to show Cindy's state of mind.FN21 A victim's hearsay statements describing threats and beatings are admissible to show the victim's state of mind and indicate fear of a defendant.FN22 This Court has distinguished between statements describing a victim's state of mind and declarations of a defendant's previous bad acts.FN23 We have held evidence of prior threats, assaults, and battery on a victim is proper to show the victim's state of mind,FN24 but a specific description of a defendant's actions in grabbing a gun is inadmissible as a declaration of a defendant's actions.FN25 Officer Abrahamson's evidence that Cindy told her Hooper pulled the phone cord from the wall appears to be inadmissible evidence of Hooper's actions, but its admission is harmless in light of the properly admitted evidence against Hooper. Officer Abrahamson's testimony about the fight and Hooper's threats was properly admitted under the state-of-mind exception. Hooper also argues that no hearsay exception applies because this statement was offered to prove the truth of the matter asserted. The record does not support this claim. The trial court did not err in admitting this evidence.

FN21. 12 O.S.1991, § 2803(3). FN22. Long v. State, 883 P.2d 167, 173 (Okl.Cr.1994); Lamb v. State, 767 P.2d 887, 890 (Okl.Cr.1988); Moore v. State, 761 P.2d 866, 870 (1988); see also Shepard v. United States, 290 U.S. 96, 54 S.Ct. 22, 78 L.Ed. 196 (1933) (statement erroneously admitted as dying declaration not admissible for state of mind where statement did not present the victim's past or present thoughts or feelings but simply accused the defendant of murder). FN23. Moss v. State, 888 P.2d 509, 518 (Okl.Cr.1994); Moore, 761 P.2d at 870. FN24. Lamb, 767 P.2d at 890. FN25. Moore, 761 P.2d at 870.

While investigating the February 19 fight, Officer Wilson called Hooper at the telephone number listed for Hooper in the police report. A person identifying himself as Hooper returned Officer Wilson's call, and told Officer Wilson he and Cindy fought on February 19 and he pushed her and put his hands around her throat. Hooper claims Officer Wilson should not have testified about this call. He agrees this conversation was not hearsay if he made the statements,FN26 but claims it was not properly authenticated. Authentication may be proved by direct or circumstantial evidence, and is sufficient if evidence supports a finding that the matter in question is what its proponent claims it to be.FN27 A voice may be identified and authenticated if the witness's opinion is based on hearing the voice at any time under circumstances connecting it with the alleged speaker.FN28 A telephone conversation may be authenticated by evidence that a call was made to the number assigned to a particular person if circumstances including self-identification show the person answering to be the one called. FN29 Officer Wilson called Hooper's number and asked Hooper to call him. A person identifying himself as Hooper called back and discussed details of the February 19 incident which Officer Wilson had not revealed. This conversation was sufficiently authenticated, and the trial court did not err in admitting the evidence. This proposition is denied.

FN26. 12 O.S.1991, § 2801(4)(B)(1). FN27. 12 O.S.1991, § 2901(A); Hightower v. State, 672 P.2d 671, 676 (Okl.Cr.1983). FN28. 12 O.S.1991, § 2901(B)(5). FN29. 12 O.S.1991, § 2901(B)(6).

In Proposition XVI Hooper claims the State failed to produce sufficient evidence linking him to the murders. When reviewing a claim of insufficient evidence this Court will ask whether, in the light most favorable to the State, the evidence could allow any reasonable trier of fact to find all the elements of the offenses beyond a reasonable doubt.FN30 Hooper first assumes the Court has agreed with his other claims of error. He asserts that without evidence from the arrest, the search, the photographs, and other evidence of which he complains, insufficient evidence supports his conviction. As Hooper's other claims of error fail, this claim fails as well. FN30. Spuehler v. State, 709 P.2d 202 (Okl.Cr.1985); Jackson v. Virginia, 443 U.S. 307, 99 S.Ct. 2781, 61 L.Ed.2d 560 (1979).

Additionally, Hooper argues that the evidence presented at trial is insufficient. He suggests the DNA evidence was ambiguous and the physical evidence cannot be connected in time with the murders. He claims he could not have committed the crimes in the time available, and states it is impossible to connect him with the State's theory of Tonya's death (see Proposition V, infra ). Hooper is mistaken. The State's case against him was entirely circumstantial, so the evidence must exclude every reasonable hypothesis except guilt.FN31 On review, this Court will accept all reasonable inferences and credibility choices which tend to support the jury's verdict.FN32 Circumstantial evidence connecting Hooper to the murders includes:

FN31. Bryan v. State, 935 P.2d 338, 358 (Okl.Cr.1997); Mayes v. State, 887 P.2d 1288, 1301–02 (Okl.Cr.1994), cert. denied, 513 U.S. 1194, 115 S.Ct. 1260, 131 L.Ed.2d 140 (1995). FN32. Bryan, 935 P.2d at 358; Maxwell v. State, 742 P.2d 1165, 1169 (Okl.Cr.1987). **Hooper's relationship with Cindy was marked by physical violence and death threats in the two years preceding the murders; ?although Cindy left Hooper in the autumn of 1993, on December 6 she told a friend she wanted to be with Hooper one last time; **at approximately 3:45 p.m. December 7 Cindy and Tonya were seen in Stremlow's pickup with a white male other than Stremlow; **the driver and passenger windows in Stremlow's truck were broken in the field near the grave; **broken window glass on Hooper's carpet was consistent with glass in Tonya's jacket pocket; **broken window glass consistent with glass from Stremlow's truck was found near the crime scene; **Hooper's shoeprints were similar to a footprint found near the broken gate at the crime scene field; **DNA evidence showed blood on Hooper's left and right shoes was consistent with Cindy's; **the victims were buried in a single grave which was saturated with gasoline; **soil on shovels in Hooper's garage matched the composition of soil from the grave; **the grave was in a wooded area, covered with branches and debris, in a field where Hooper had been before; **on December 9 officers saw a fresh scratch on Hooper's arm; **9mm casings were found in the field, and a 9mm bullet was embedded in a branch on the grave; **the three victims were each shot twice, and the wounds were consistent with a 9mm bullet; **Hooper owned a 9mm pistol and evidence showed that either the Oklahoma City police or Hooper had exclusive possession of the pistol since its July 15, 1993, purchase; **n December 6 or 7, Hooper showed neighbors a 9mm pistol; **Hooper had a live 9mm bullet in his pocket when he was arrested; **shell casings from the scene matched casings found where Hooper practiced target shooting and also matched a bullet test-fired from Hooper's gun; **the 9mm bullet embedded in the branch on the grave was fired from Hooper's gun; **white fibers consistent with Tonya's jacket were pinned to the branch on the grave by the 9mm bullet from Hooper's gun; **the branch on the grave appeared to come from a limb near a pool of blood; **DNA evidence showed the blood pool was consistent with Cindy or Tonya; **blue fibers consistent with Tonya's jacket were near the blood pool; **a small, hot object made a hole through the outer blue fabric and white fiber lining of Tonya's hood; **after December 7, a person entered Stremlow's home without forced entry, and the only key to the home was on the truck key ring; **after December 7 Hooper's fingerprints were found on a Jim Beam bottle left on Stremlow's and Cindy's dresser.

This evidence is inconsistent with innocence and excludes every reasonable hypothesis except that of guilt. This proposition is denied.

SENTENCING ISSUES

In Proposition VII Hooper attacks the content of the victim impact evidence admitted during the second stage of trial. Cindy's sister and mother and the children's paternal grandmother testified about the effect the deaths had on their lives and the life of the children's father.FN33 They said Hooper should receive the death sentence. The testimony was in a question-and-answer format and Hooper declined cross-examination. Hooper first contends the statute is unconstitutional, then argues the victim impact evidence in his case was too emotional and did not meet the statutory requirements as interpreted by this Court. He objected generally to victim impact evidence, but did not object specifically to the testimony at trial and has waived all but plain error.FN34

FN33. Hooper does not raise as a proposition of error the paternal grandmother's qualifications as a witness under 22 O.S.Supp.1992, § 984(2). FN34. During the motions hearing, Hooper requested an in camera hearing before the evidence was admitted. In Mitchell v. State, 884 P.2d 1186, 1204 (Okl.Cr.1994), cert. denied, 516 U.S. 827, 116 S.Ct. 95, 133 L.Ed.2d 50 (1995), we held that victim impact evidence should be independently weighed before admission like any other evidence to ensure it is more probative than prejudicial. Although all parties were aware of Mitchell, the trial court denied this request and Hooper did not renew the request at trial.

Hooper admits we have held 21 O.S.Supp.1992, § 984, constitutional,FN35 but urges the Court to reconsider. In Cargle this Court rejected the argument that victim impact evidence acts as a “super” aggravating circumstance.FN36 Cargle and our subsequent decisions sufficiently limit the purpose and presentation of victim impact evidence. The statute is not overbroad on its face or as applied here.

FN35. Hain v. State, 919 P.2d 1130, 1144 (Okl.Cr.1996); Cargle v. State, 909 P.2d 806 (Okl.Cr.1995); Mitchell, 884 P.2d at 1203–1204 (admission of victim impact evidence does not violate prohibition against ex post facto laws). FN36. Cargle, 909 P.2d at 828 n. 15.

Victim impact evidence is intended to provide a “quick glimpse” of a victim's characteristics and the effect of the victim's death on survivors.FN37 Evidence should be restricted to the financial, emotional, psychological, and physical effect of the crime itself and some personal characteristics of the victim.FN38 Trial courts should beware in admitting evidence which focuses on the emotional impact of the crime to the exclusion of other factors; FN39 “the more a jury is exposed to the emotional aspects of a victim's death, the less likely their verdict will be a ‘reasoned moral response’ ”.FN40 Hooper argues the witnesses should not have been allowed to give their opinion that Hooper should be sentenced to death. This Court has recently held that victim impact witnesses may recommend a sentence.FN41 A witness's opinion “should be given as a straight-forward, concise response to a question asking what the recommendation is; or a short statement of recommendation in a written statement, without amplification.” FN42 We will review such statements with a heightened degree of scrutiny,FN43 but opinion evidence recommending a penalty is admissible under § 984.

FN37. Cargle, 909 P.2d at 828. FN38. 22 O.S.Supp.1993, § 984.; Cargle, 909 P.2d at 828. FN39. Cargle, 909 P.2d at 830. FN40. Conover v. State, 933 P.2d 904, 921 (Okl.Cr.1997) FN41. Ledbetter v. State, 933 P.2d 880, 890–91 (Okl.Cr.1997); Conover, 933 P.2d at 920–21. FN42. Ledbetter, 933 P.2d at 891. FN43. Id.; Conover, 933 P.2d at 921.

Three witnesses gave victim impact evidence. Hooper complains about Barbara Jarman's testimony. He first argues that Mrs. Jarman's statement exceeds the statutory framework of admissible evidence because it focuses on the emotional impact of the children's deaths to the exclusion of other factors. Mrs. Jarman's statement describes the emotional effect the children's deaths had on her and her son, but also describes the physical and psychological effects. Taken as a whole, the testimony is within the bounds of admissible evidence, and its focus on emotion does not so skew the presentation as to divert the jury from its duty to reach a reasoned moral response.

Hooper claims the weighing process was skewed when Mrs. Jarman repeated the State's theory of Tonya's death. Mrs. Jarman said Hooper should be sentenced to death, and said she saw Tonya running through the woods, being chased and caught, and saw someone looking into Tonya's big, beautiful brown eyes before shooting her in the face and leaving her to die. This statement was not a “straightforward concise response” and should not have been admitted. However, we cannot say its admission had such a prejudicial effect as to prevent the jury from making a reasoned moral decision whether to impose the death penalty. Hooper claims his sentence is unreliable because the prosecutor and Mrs. Jarman swayed the jury's passions by describing a scene unsupported by the evidence. The State's theory of Tonya's death was a reasonable deduction from the evidence at trial [see Proposition V, infra ]. While Mrs. Jarman's recommendation was inappropriate opinion evidence, it was not based on an inaccurate and unsupported account of the crimes. Nothing in the record suggests Mrs. Jarman or the prosecutor intended to impermissibly influence jurors and skew the weighing process.

Hooper finally argues that admission of victim impact evidence is irrelevant to the ultimate issue to be decided. The legislature has determined that victim impact evidence is both relevant and admissible. FN44 Hooper claims this Court should review the issue for more than plain error, even though he did not object to the evidence at trial. He argues that any objection to victim impact evidence would alienate the jury, and counsel had to choose between annoying the sentencer and preserving issues for appeal. The trial court instructed the jury to disregard objections and conferences at the bench, and counsel in closing asked the jury not to blame Hooper if counsel had done something the jury didn't like. Nothing in the record suggests this jury could not separate counsel's trial conduct from the issues it had to decide. FN44. 22 O.S.Supp.1993, §§ 984 et seq.

Oklahoma's statute allowing presentation of victim impact evidence is constitutional. While a small portion of the victim impact testimony was overly emotional and prejudicial, its admission did not prevent the jury from fulfilling its function and was harmless in light of the other evidence presented in the second stage of trial. This proposition is denied.

In Proposition VIII Hooper a) argues the great risk of death to more than one person aggravating circumstance is unconstitutional on its face and as construed by this court, and b) claims evidence in the record is insufficient to establish this circumstance. The jury found as to all three victims that Hooper had knowingly created a great risk of death to more than one person.FN45 Hooper claims this aggravating circumstance performs no narrowing function because it applies whenever a defendant commits multiple murders. “The fundamental question on review is whether the aggravating circumstance, as construed, genuinely narrows the class of persons eligible for the death penalty. Constitutional infirmity does not arise merely because the aggravating circumstance is not subject to mechanical application, or because a wide range of circumstances satisfies it.” FN46 Hooper argues this circumstance does not apply simply because a defendant kills more than one person at a time. He cites cases in which this Court has held the great risk of death aggravating circumstance is proved not by the death of more than one person, but by a defendant's acts which create a risk of death to another “in close proximity, in terms of time, location, and intent” to the killing. FN47 These cases do not support Hooper's argument. They imply that the aggravating circumstance is appropriate in this situation but hold that it may be appropriate where only one person is killed or where more than one person is killed but the murders are not contemporaneous. Hooper admits this Court has repeatedly held this aggravating circumstance applies where a defendant contemporaneously kills more than one person.FN48

FN45. 21 O.S.1991, § 701.12(2). FN46. Allen v. State, 923 P.2d 613, 622 (Okl.Cr.1996). FN47. Allen, 923 P.2d at 622; Snow v. State, 876 P.2d 291, 297 (Okl.Cr.1994), cert. denied, 513 U.S. 1179, 115 S.Ct. 1165, 130 L.Ed.2d 1120 (1995); Pennington v. State, 913 P.2d 1356, 1370 (Okl.Cr.1995), cert. denied, 519 U.S. 841, 117 S.Ct. 121, 136 L.Ed.2d 72 (1996). FN48. Sellers v. State, 809 P.2d 676, 691 (Okl.Cr.1991), cert. denied, 502 U.S. 912, 112 S.Ct. 310, 116 L.Ed.2d 252 (1991); Fowler v. State, 779 P.2d 580, 588 (Okl.Cr.1989), cert. denied, 494 U.S. 1060, 110 S.Ct. 1537, 108 L.Ed.2d 775 (1990); Nguyen v. State, 769 P.2d 167, 174 (Okl.Cr.1988), cert. denied, 492 U.S. 925, 109 S.Ct. 3264, 106 L.Ed.2d 609 (1989), overruled on other grounds by Green v. State, 862 P.2d 1271 (Okl.Cr.1993).

On review, this Court will consider whether, in the light most favorable to the State, the evidence is sufficient to support the alleged aggravating circumstance.FN49 Tonya and her mother were last seen together at approximately 3:45 p.m. on December 7. All three victims were found buried in a single grave, and each had suffered two gunshot wounds to the head. All three victims were in Stremlow's truck that morning, and the passenger windows on that truck appeared to be broken in the field near the grave. The jury could conclude the victims were together when they were killed. Evidence sufficiently suggests the murders were in close proximity. The aggravating circumstance of great risk of death is constitutional and supported by the evidence in this case. This proposition is denied. FN49. Valdez v. State, 900 P.2d 363, 382 (Okl.Cr.), cert. denied, 516 U.S. 967, 116 S.Ct. 425, 133 L.Ed.2d 341 (1995).

In Proposition XI Hooper argues the murder committed for the purpose of avoiding or preventing a lawful arrest or prosecution aggravating circumstance FN50 was not supported by the evidence beyond a reasonable doubt. The jury found that Tonya's murder was committed for the purpose of avoiding arrest or prosecution, on the grounds that Hooper killed Tonya because she saw him kill her mother. Hooper argues that insufficient evidence supports this finding since it appears to rely on the State's theory of Tonya's death (see Proposition V, infra ) and other speculative evidence. The avoiding arrest aggravating circumstance requires a predicate crime for which a defendant seeks to avoid arrest or prosecution, separate from the murder with which he is charged.FN51 Evidence supports a finding that Hooper shot Tonya because he sought to avoid arrest or prosecution for Cindy's murder. Cindy's murder, although contemporaneous in time and place, provides a sufficient predicate crime. This proposition of error is denied.