Executed June 18, 2014 07:43 p.m. EST by Lethal Injection in Florida

23rd murderer executed in U.S. in 2014

1382nd murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

6th murderer executed in Florida in 2014

87th murderer executed in Florida since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(23) |

|

John Ruthell Henry B / M / 34 - 63 |

Suzanne Henry W / F / 29 Eugene Leo Christian B / M / 5 |

Her Son |

10-18-91 |

Citations:

Henry v. State, 574 So.2d 66 (Fla. 1991). (Direct Appeal-Reversed)

Henry v. State, 649 So.2d 1366 (Fla. 1994). (Direct Appeal-After Retrial)

Henry v. State, 862 So.2d 679 (Fla. 2003). (PCR)

Henry v. Secretary, 490 F.3d 835 (11th Cir. 2007). (Habeas)

Final / Special Meal:

Refused.

Final Words:

"I can't undo what I've done. If I could, I would. I ask for your forgiveness if you can find it in your heart."

Internet Sources:

Florida Department of Corrections

DC Number: 053105Current Prison Sentence History:

12/22/1985 1ST DG MUR/PREMED. OR ATT. 10/18/1991 PASCO 8502685 DEATH SENTENCE

12/22/1985 1ST DG MUR/PREMED. OR ATT. 10/21/1992 HILLSBOROUGH 8514273 DEATH SENTENCE

Incarceration History:

05/14/1976 - 01/04/1983

04/29/1987 - 04/30/1991

10/21/1992 - Currently Incarcerated

Prior Prison History:

08/19/1975 2ND DEG.MURD,DANGEROUS ACT 03/22/1976 PASCO 15Y 0M 0D

"John Henry, Pasco man who killed wife, boy, is executed," by Jon Silman. (Wednesday, June 18, 2014 6:47pm)

STARKE — More than 25 years after her aunt and cousin were brutally murdered by John Ruthell Henry, Selena Geiger finally felt peace. "I actually feel good. I don't feel sorry for him," she said, after witnessing Henry's execution by lethal injection. "I wish it could've been different. I wish he could've died the way he killed them." The state of Florida executed Henry, 63, for the 1985 murder of his wife Suzanne Henry — Geiger's aunt — at the Florida State Prison on Wednesday night.

Henry's was the third execution in the United States in the past 24 hours. Those executions, in Georgia and Missouri, were the first since April 29, when officials stopped the execution of Clayton Lockett in Oklahoma because of issues with his veins. He writhed and shook, according to reports. He later died of a heart attack.

Henry's execution was calm. He refused a last meal and was visited by his family, who did not attend the execution. In a statement, they said they are grateful for an ending to the decades-long saga. A group of the victim's family members sat in the front row, in front of a glass window. There were 24 people in the room. Henry spent his last moments strapped to a bed and draped in a white sheet to his neck. Tubes out of a wall went into his arms. His last words were an apology: He asked for forgiveness in Jesus Christ's name and said if he could take back what he did, he would. He muttered to himself when the execution began at 7:30, which was delayed because of a last minute appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. His eyes fluttered and he yawned when the first of the three-drug cocktail took effect. A man shook him to make sure he was unconscious. The sheet stopped rising and falling around 7:34, and his face lost color.

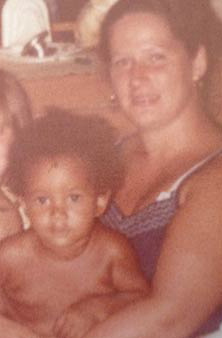

After the execution, Geiger, 38, held up a photo of Suzanne Henry and her 5-year-old son, Eugene Christian. "These are the victims," she said. "These are the ones we need to remember." Henry was convicted of three murders. In 1976, he stabbed his 28-year-old girlfriend Patricia Roddy 20 times in the front seat of a car while her children sat in the back. One child pleaded with him, saying "Daddy, Daddy, please stop hurting Mommy." He did a little over seven years in prison and seemed to improve and rehabilitate. He was a model inmate. After his release, he got back into drugs and had pending charges against him. He murdered his wife after an argument while Eugene was with them in a Zephyrhills apartment.

Henry covered the boy's face and kidnapped him, drove to Hillsborough County and bought him fried chicken. Henry smoked crack, then, with Christian sitting in his lap, he stabbed the child and left his body in a field. Henry stabbed both his wife and stepson in the neck so many times with a 5-inch paring knife that they were nearly decapitated, Geiger said.

Geiger was young when the crime happened, and she remembers the chaos of that day. She said she carries that brutality with her always. Henry stole her youth from her, she said. "You see movies and you see TV shows about bad guys but you never really know," she said. "This man showed me that true evil really exists." His apology? It means nothing to her. But her family can finally rest. "We have some closure," she said. "Justice has finally been done."

"Florida becomes the third state in 24 hours to execute an inmate," by Matt Pearce. (June 18, 2014)

Three states, three convicted killers, three executions in a row. On Wednesday, Florida became the third state in 24 hours to execute an inmate on death row, signaling that capital punishment in the U.S. was clear to continue with the Supreme Court's blessing after a botched execution in Oklahoma in April brought widespread criticism and scrutiny to the practice. John Ruthell Henry, 63, who had been sentenced to death after killing his wife and her 5-year-old son in 1985, died Wednesday evening after receiving a three-drug lethal injection at the Florida State Prison in Raiford.

His death came shortly after U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas denied Henry's appeal for a stay of execution Wednesday. Henry, who once scored 78 on an IQ test, had argued that he was too mentally disabled to be executed. Henry's own attorney of several years, Baya Harrison III, told the Los Angeles Times on Wednesday that the mental-disability claim was a bit of a stretch, given that Henry was prone to writing elaborate, "very kind-of-intelligent" letters to judges about his case. "He's killing me with these very well-written letters quoting the Constitution and things of that nature. I’m sitting here saying, 'John, for God's sake!'" Harrison told The Times in an interview before Henry's execution. "It is what it is. He’s a human being, he's entitled to say what he wants to say. I've never tried to shut him up." Harrison added: "This guy does not want to die. ... [But] frankly, I’ve done everything I can."

As with Henry's lethal injection, this week's executions of Marcus Wellons, 59, in Georgia, and of John Winfield, 46, in Missouri, came with the explicit approval of several high courts and public officials. Until Wellons, there had been no executions in the U.S. since the gruesome execution of Clayton Lockett in Oklahoma in April, which lasted more than 40 minutes after an executioner apparently failed to properly insert a needle into a vein in Lockett's groin. President Obama criticized the execution, and capital punishment opponents around the country have since cited Lockett's death in their arguments that execution secrecy laws are unconstitutional and that lethal injection drugs may be unreliable. For almost two months afterward, no executions were carried out across the U.S. and legal experts were mixed on whether the drought was the result of a newfound caution or just a coincidence in scheduling.

What became clear, however, was that capital punishment would not be coming to an end because of Lockett's death. The first of the three executions this week, in Georgia, was carried out under a high level of media scrutiny -- at least as much as scrutiny was possible, given that the state's secrecy laws protect information about where it gets its drugs and who administers them. Wellons had been sentenced to death in Georgia for the 1989 rape and murder of 15-year-old India Roberts, and the Supreme Court gave its blessing for the procedure to go ahead. The Associated Press, the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Guardian and other outlets watched (albeit not all in person) to see whether his execution would be carried out without incident, which media witnesses said it was. "Departments of corrections are aware they're under intense scrutiny now," said Fordham Law School professor and execution expert Deborah Denno. "They certainly always were. ... But I think the Lockett execution is going to continue to resonate because of the extraordinary impact the [botch] had."

An hour after Wellons was executed, John Winfield was swiftly put to death in Missouri: His procedure started at 12:01 a.m. and his death was declared at 12:10 a.m. Winfield's execution had been scheduled for 12:01 a.m., but he didn't know it was actually going to happen until several hours before, when the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals abruptly revoked a stay of execution that had been granted a week earlier. U.S. Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito later approved that decision. Winfield's attorneys had argued that state officials improperly tampered with a prison employee who planned to praise Winfield's character and stellar behavior in prison in a request for clemency from Missouri's governor. But the act that had put Winfield on death row in the first place was one that Missouri's governor, Jay Nixon, and several courts could not overlook.

Winfield was convicted of shooting three women, killing two of them -- Arthea Sanders and Shawnee Murphy -- in 1996. The third woman was permanently blinded Winfield, Nixon said in a statement that announced his denial of clemency, "showed no mercy that night on his victims. The jury in this case properly found that these heinous crimes warranted the death penalty, and my denial of clemency upholds the jury’s decision." And with his announcement, Missouri, like Georgia and Florida, was officially back in the execution business.

"Florida executes man for 1985 murder of wife and her child, David Adams (Wed Jun 18, 2014 8:22pm EDT)

(Reuters) - A man convicted of killing his wife and her 5-year-old son nearly 30 years ago was executed at Florida State Prison on Wednesday, the third person to die by injection in 24 hours in separate cases across the South. John R. Henry's death also was the third U.S. execution since a botched injection in Oklahoma in April renewed a national debate on capital punishment. Henry, 63, served eight years for manslaughter in the slaying of his common-law wife and was on parole when he committed the double murder a few days before Christmas 1985.

"John Ruthell Henry Becomes 3rd Man Executed In 24 Hours." (06/18/2014 7:59 pm EDT)

STARKE, Fla. (AP) — Florida has executed a man who fatally stabbed his wife and her young son in 1985. It is the third U.S. execution in less than 24 hours since a botched April lethal injection in Oklahoma. The governor's office says John Ruthell Henry was pronounced dead at 7:43 p.m. Wednesday.

The 63-year-old was convicted and sentenced to death for fatally stabbing his wife, Suzanne Henry. He also was convicted of fatally stabbing Suzanne Henry's 5-year-old son hours after the woman's murder. Henry previously had pleaded no contest to second-degree murder for stabbing his common-law wife, Patricia Roddy, in 1976. He served less than eight years and was released in 1983.

The U.S. Supreme Court turned down a last-second appeal by attorneys who argued Henry wasn't mentally stable enough to comprehend his death sentence.

- I can't undo what I've done. I ask for your forgiveness': Last words of killer who murdered his wife and toddler as he becomes third inmate executed in 24 hours.- John Ruthell Henry, 63, was pronounced dead at 7.43pm after being injected with three-drug cocktail.

- Henry refused a last meal and had a final visit with his family before execution Wednesday.

- The 63-year-old was convicted of stabbing to death his 29-year-old estranged wife and her 5-year-old son.

- Henry's lawyers filed last-minute appeal with the U.S. Supreme Court claiming that he is mentally ill.

By Snejana Farberov. (18:50 EST, 18 June 2014)

Florida executed tonight a convicted killer who fatally stabbed his wife and her young son in 1985. It is the third U.S. execution in less than 24 hours since a botched April lethal injection in Oklahoma. The governor's office says John Ruthell Henry, 63, was pronounced dead at 7.43pm Wednesday.

The inmate was convicted and sentenced to death for fatally stabbing his wife, 29-year-old Suzanne Henry, a few days before Christmas outside Plant City, Florida. A detective testified at his trial in 1987 that Henry stabbed Suzanne in the neck with a five-inch paring knife and then watched her die while smoking a cigarette, reported Tampa Bay Times. He also was found guilty of murdering his 5-year-old stepson, Eugene Christian, hours after the woman's murder. The toddler was stabbed in the throat five times.

Henry previously had pleaded no contest to second-degree murder for stabbing his common-law wife, Patricia Roddy, in 1976 in front of her children, one of whom begged him to stop hurting the woman. He served less than eight years and was released in 1983. Suzanne Henry's relatives told reporters she hadn't known about John Henry's previous killing when she married him after his release.

The U.S. Supreme Court turned down a last-second appeal by attorneys who argued Henry wasn't mentally stable enough to comprehend his death sentence. Just before his execution, Henry asked for forgiveness and apologized for what he'd done. 'I can't undo what I've done. If I could, I would. I ask for your forgiveness if you can find it in your heart,' he said.

The state claims anyone with an IQ of at least 70 is not mentally disabled; testing has shown Henry's IQ at 78, though his lawyers said it should be re-evaluated. A spokeswoman for the Florida Department of Corrections said Henry has turned down a last meal, and she described his demeanor as 'calm' before the execution. Earlier in the day, Henry was visited by his sister, niece and daughter, as well a Catholic spiritual adviser, said DOC spokeswoman Jessica Cary.

‘Carrying out the sentence of the death penalty is one of our most solemn duties,’ Cary told reporters. ‘[We strive to] carry it out in a dignified and humane manner.’ Henry was put to death using a combination of three drugs, beginning with midazolam to render him unconscious. After that, the condemned man was injected with vecuronium bromide and potassium chloride. John Henry has become the third man to be put to death in the U.S. since April, when officials in Oklahoma botched the lethal injection of Clayton Lockett, who ended up dying from a heart attack.

The case made international headlines and led to the postponement of nine executions nationwide. The 63-year-old Floria man's execution Wednesday was preceded by those of Georgia inmate Marcus Wellons and Missouri convicted killer John Winfiled, who were put to death Tuesday night. Neither execution had any noticeable complications, and Henry's execution Wednesday also appeared to go normally. Georgia and Missouri both use the single drug pentobarbital, a sedative, whereas Florida uses a three-drug cocktail.

Midazolam, a sedative used before surgery, has only been used in Florida since October; previously, sodium thiopental was used, but its U.S. manufacturer stopped making it and Europe banned its manufacturers from exporting it for executions. Henry's was be the 13th execution in Florida since April 2013, and the 18th since Republican Gov. Rick Scott took office in 2011. Scott on Tuesday brushed aside questions about the state's execution procedures, saying he has to 'uphold the laws of the land.' When asked directly if he had discussed with the Department of Corrections what happened in Oklahoma and whether any changes were needed in Florida, Scott would only say: 'I focus on making sure that we do things the right way here.'

During Henry's trial, prosecutors said the unemployed bricklayer went to Suzanne Henry's home three days before Christmas of 1985 to talk about buying a gift for the boy, who was Suzanne's son from a prior relationship. They fought over Henry living with another woman and he stabbed her 13 times in the neck and face. Prosecutors said Henry then took the boy and drove around for nine hours, sometimes smoking crack cocaine, before stabbing him five times in the neck. Hours later, Henry told a detective, he found himself wandering a field. He later told therapists he had killed the child to reunite him with his mother.

Henry tried to use an insanity defense for killing his wife. Psychiatrists at the trial testified that Henry had a low IQ, suffered from chronic paranoia and smoked crack. He told them he had intended to commit suicide after killing the boy but said he was unable to go through with it. In an appeal the Florida Supreme Court rejected last week, attorney Baya Harrison III wrote that Henry's 'abhorrent childhood, extensive personal and family mental health history, poor social adjustment, and lack of rational thinking and reasoning skills so impaired his adaptive functioning that he was actually performing at the level of a person with an IQ of 70.'

In May, a panel of mental health experts said Henry doesn't suffer from mental illness or an intellectual disability and that he understands "the nature and effect of the death penalty and why it is to be imposed on him," according to court records.

Following is a list of inmates executed since Florida resumed executions in 1979:

1. John Spenkelink, 30, executed May 25, 1979, for the murder of traveling companion Joe Szymankiewicz in a Tallahassee hotel room.

2. Robert Sullivan, 36, died in the electric chair Nov. 30, 1983, for the April 9, 1973, shotgun slaying of Homestead hotel-restaurant assistant manager Donald Schmidt.

3. Anthony Antone, 66, executed Jan. 26, 1984, for masterminding the Oct. 23, 1975, contract killing of Tampa private detective Richard Cloud.

4. Arthur F. Goode III, 30, executed April 5, 1984, for killing 9-year-old Jason Verdow of Cape Coral March 5, 1976.

5. James Adams, 47, died in the electric chair on May 10, 1984, for beating Fort Pierce millionaire rancher Edgar Brown to death with a fire poker during a 1973 robbery attempt.

6. Carl Shriner, 30, executed June 20, 1984, for killing 32-year-old Gainesville convenience-store clerk Judith Ann Carter, who was shot five times.

7. David L. Washington, 34, executed July 13, 1984, for the murders of three Dade County residents _ Daniel Pridgen, Katrina Birk and University of Miami student Frank Meli _ during a 10-day span in 1976.

8. Ernest John Dobbert Jr., 46, executed Sept. 7, 1984, for the 1971 killing of his 9-year-old daughter Kelly Ann in Jacksonville..

9. James Dupree Henry, 34, executed Sept. 20, 1984, for the March 23, 1974, murder of 81-year-old Orlando civil rights leader Zellie L. Riley.

10. Timothy Palmes, 37, executed in November 1984 for the Oct. 19, 1976, stabbing death of Jacksonville furniture store owner James N. Stone. He was a co-defendant with Ronald John Michael Straight, executed May 20, 1986.

11. James David Raulerson, 33, executed Jan. 30, 1985, for gunning down Jacksonville police Officer Michael Stewart on April 27, 1975.

12. Johnny Paul Witt, 42, executed March 6, 1985, for killing, sexually abusing and mutilating Jonathan Mark Kushner, the 11-year-old son of a University of South Florida professor, Oct. 28, 1973.

13. Marvin Francois, 39, executed May 29, 1985, for shooting six people July 27, 1977, in the robbery of a ``drug house'' in the Miami suburb of Carol City. He was a co-defendant with Beauford White, executed Aug. 28, 1987.

14. Daniel Morris Thomas, 37, executed April 15, 1986, for shooting University of Florida associate professor Charles Anderson, raping the man's wife as he lay dying, then shooting the family dog on New Year's Day 1976.

15. David Livingston Funchess, 39, executed April 22, 1986, for the Dec. 16, 1974, stabbing deaths of 53-year-old Anna Waldrop and 56-year-old Clayton Ragan during a holdup in a Jacksonville lounge.

16. Ronald John Michael Straight, 42, executed May 20, 1986, for the Oct. 4, 1976, murder of Jacksonville businessman James N. Stone. He was a co-defendant with Timothy Palmes, executed Jan. 30, 1985.

17. Beauford White, 41, executed Aug. 28, 1987, for his role in the July 27, 1977, shooting of eight people, six fatally, during the robbery of a small-time drug dealer's home in Carol City, a Miami suburb. He was a co-defendant with Marvin Francois, executed May 29, 1985.

18. Willie Jasper Darden, 54, executed March 15, 1988, for the September 1973 shooting of James C. Turman in Lakeland.

19. Jeffrey Joseph Daugherty, 33, executed March 15, 1988, for the March 1976 murder of hitchhiker Lavonne Patricia Sailer in Brevard County.

20. Theodore Robert Bundy, 42, executed Jan. 24, 1989, for the rape and murder of 12-year-old Kimberly Leach of Lake City at the end of a cross-country killing spree. Leach was kidnapped Feb. 9, 1978, and her body was found three months later some 32 miles west of Lake City.

21. Aubry Dennis Adams Jr., 31, executed May 4, 1989, for strangling 8-year-old Trisa Gail Thornley on Jan. 23, 1978, in Ocala.

22. Jessie Joseph Tafero, 43, executed May 4, 1990, for the February 1976 shooting deaths of Florida Highway Patrolman Phillip Black and his friend Donald Irwin, a Canadian constable from Kitchener, Ontario. Flames shot from Tafero's head during the execution.

23. Anthony Bertolotti, 38, executed July 27, 1990, for the Sept. 27, 1983, stabbing death and rape of Carol Ward in Orange County.

24. James William Hamblen, 61, executed Sept. 21, 1990, for the April 24, 1984, shooting death of Laureen Jean Edwards during a robbery at the victim's Jacksonville lingerie shop.

25. Raymond Robert Clark, 49, executed Nov. 19, 1990, for the April 27, 1977, shooting murder of scrap metal dealer David Drake in Pinellas County.

26. Roy Allen Harich, 32, executed April 24, 1991, for the June 27, 1981, sexual assault, shooting and slashing death of Carlene Kelly near Daytona Beach.

27. Bobby Marion Francis, 46, executed June 25, 1991, for the June 17, 1975, murder of drug informant Titus R. Walters in Key West.

28. Nollie Lee Martin, 43, executed May 12, 1992, for the 1977 murder of a 19-year-old George Washington University student, who was working at a Delray Beach convenience store.

29. Edward Dean Kennedy, 47, executed July 21, 1992, for the April 11, 1981, slayings of Florida Highway Patrol Trooper Howard McDermon and Floyd Cone after escaping from Union Correctional Institution.

30. Robert Dale Henderson, 48, executed April 21, 1993, for the 1982 shootings of three hitchhikers in Hernando County. He confessed to 12 murders in five states.

31. Larry Joe Johnson, 49, executed May 8, 1993, for the 1979 slaying of James Hadden, a service station attendant in small north Florida town of Lee in Madison County. Veterans groups claimed Johnson suffered from post-traumatic stress syndrome.

32. Michael Alan Durocher, 33, executed Aug. 25, 1993, for the 1983 murders of his girlfriend, Grace Reed, her daughter, Candice, and his 6-month-old son Joshua in Clay County. Durocher also convicted in two other killings.

33. Roy Allen Stewart, 38, executed April 22, 1994, for beating, raping and strangling of 77-year-old Margaret Haizlip of Perrine in Dade County on Feb. 22, 1978.

34. Bernard Bolander, 42, executed July 18, 1995, for the Dade County murders of four men, whose bodies were set afire in car trunk on Jan. 8, 1980.

35. Jerry White, 47, executed Dec. 4, 1995, for the slaying of a customer in an Orange County grocery store robbery in 1981.

36. Phillip A. Atkins, 40, executed Dec. 5, 1995, for the molestation and rape of a 6-year-old Lakeland boy in 1981.

37. John Earl Bush, 38, executed Oct. 21, 1996, for the 1982 slaying of Francis Slater, an heir to the Envinrude outboard motor fortune. Slater was working in a Stuart convenience store when she was kidnapped and murdered.

38. John Mills Jr., 41, executed Dec. 6, 1996, for the fatal shooting of Les Lawhon in Wakulla and burglarizing Lawhon's home.

39. Pedro Medina, 39, executed March 25, 1997, for the 1982 slaying of his neighbor Dorothy James, 52, in Orlando. Medina was the first Cuban who came to Florida in the Mariel boat lift to be executed in Florida. During his execution, flames burst from behind the mask over his face, delaying Florida executions for almost a year.

40. Gerald Eugene Stano, 46, executed March 23, 1998, for the slaying of Cathy Scharf, 17, of Port Orange, who disappeared Nov. 14, 1973. Stano confessed to killing 41 women.

41. Leo Alexander Jones, 47, executed March 24, 1998, for the May 23, 1981, slaying of Jacksonville police Officer Thomas Szafranski.

42. Judy Buenoano, 54, executed March 30, 1998, for the poisoning death of her husband, Air Force Sgt. James Goodyear, Sept. 16, 1971.

43. Daniel Remeta, 40, executed March 31, 1998, for the murder of Ocala convenience store clerk Mehrle Reeder in February 1985, the first of five killings in three states laid to Remeta.

44. Allen Lee ``Tiny'' Davis, 54, executed in a new electric chair on July 8, 1999, for the May 11, 1982, slayings of Jacksonville resident Nancy Weiler and her daughters, Kristina and Katherine. Bleeding from Davis' nose prompted continued examination of effectiveness of electrocution and the switch to lethal injection.

45. Terry M. Sims, 58, became the first Florida inmate to be executed by injection on Feb. 23, 2000. Sims died for the 1977 slaying of a volunteer deputy sheriff in a central Florida robbery.

46. Anthony Bryan, 40, died from lethal injection Feb. 24, 2000, for the 1983 slaying of George Wilson, 60, a night watchman abducted from his job at a seafood wholesaler in Pascagoula, Miss., and killed in Florida.

47. Bennie Demps, 49, died from lethal injection June 7, 2000, for the 1976 murder of another prison inmate, Alfred Sturgis. Demps spent 29 years on death row before he was executed.

48. Thomas Provenzano, 51, died from lethal injection on June 21, 2000, for a 1984 shooting at the Orange County courthouse in Orlando. Provenzano was sentenced to death for the murder of William ``Arnie'' Wilkerson, 60.

49. Dan Patrick Hauser, 30, died from lethal injection on Aug. 25, 2000, for the 1995 murder of Melanie Rodrigues, a waitress and dancer in Destin. Hauser dropped all his legal appeals.

50. Edward Castro, died from lethal injection on Dec. 7, 2000, for the 1987 choking and stabbing death of 56-year-old Austin Carter Scott, who was lured to Castro's efficiency apartment in Ocala by the promise of Old Milwaukee beer. Castro dropped all his appeals.

51. Robert Glock, 39 died from lethal injection on Jan. 11, 2001, for the kidnapping murder of a Sharilyn Ritchie, a teacher in Manatee County. She was kidnapped outside a Bradenton shopping mall and taken to an orange grove in Pasco County, where she was robbed and killed. Glock's co-defendant Robert Puiatti remains on death row.

52. Rigoberto Sanchez-Velasco, 43, died of lethal injection on Oct. 2, 2002, after dropping appeals from his conviction in the December 1986 rape-slaying of 11-year-old Katixa ``Kathy'' Ecenarro in Hialeah. Sanchez-Velasco also killed two fellow inmates while on death row.

53. Aileen Wuornos, 46, died from lethal injection on Oct. 9, 2002, after dropping appeals for deaths of six men along central Florida highways.

54. Linroy Bottoson, 63, died of lethal injection on Dec. 9, 2002, for the 1979 murder of Catherine Alexander, who was robbed, held captive for 83 hours, stabbed 16 times and then fatally crushed by a car.

55. Amos King, 48, executed by lethal inection for the March 18, 1977 slaying of 68-year-old Natalie Brady in her Tarpon Spring home. King was a work-release inmate in a nearby prison.

56. Newton Slawson, 48, executed by lethal injection for the April 11, 1989 slaying of four members of a Tampa family. Slawson was convicted in the shooting deaths of Gerald and Peggy Wood, who was 8 1/2 months pregnant, and their two young children, Glendon, 3, and Jennifer, 4. Slawson sliced Peggy Wood's body with a knife and pulled out her fetus, which had two gunshot wounds and multiple cuts.

57. Paul Hill, 49, executed for the July 29, 1994, shooting deaths of Dr. John Bayard Britton and his bodyguard, retired Air Force Lt. Col. James Herman Barrett, and the wounding of Barrett's wife outside the Ladies Center in Pensacola.

58. Johnny Robinson, died by lethal injection on Feb. 4, 2004, for the Aug. 12, 1985 slaying of Beverly St. George was traveling from Plant City to Virginia in August 1985 when her car broke down on Interstate 95, south of St. Augustine. He abducted her at gunpoint, took her to a cemetery, raped her and killed her.

59. John Blackwelder, 49, was executed by injection on May 26, 2004, for the calculated slaying in May 2000 of Raymond Wigley, who was serving a life term for murder. Blackwelder, who was serving a life sentence for a series of sex convictions, pleaded guilty to the slaying so he would receive the death penalty.

60. Glen Ocha, 47, was executed by injection April 5, 2005, for the October, 1999, strangulation of 28-year-old convenience store employee Carol Skjerva, who had driven him to his Osceola County home and had sex with him. He had dropped all appeals.

61. Clarence Hill 20 September 2006 lethal injection Stephen Taylor

62. Arthur Dennis Rutherford 19 October 2006 lethal injection Stella Salamon

63. Danny Rolling 25 October 2006 lethal injection Sonja Larson, Christina Powell, Christa Hoyt, Manuel R. Taboada, and Tracy Inez Paules

64. Ángel Nieves Díaz 13 December 2006 lethal injection Joseph Nagy

65. Mark Dean Schwab 1 July 2008 lethal injection Junny Rios-Martinez, Jr.

66. Richard Henyard 23 September 2008 lethal injection Jamilya and Jasmine Lewis

67. Wayne Tompkins 11 February 2009 lethal injection Lisa DeCarr

68. John Richard Marek 19 August 2009 lethal injection Adela Marie Simmons

69. Martin Grossman 16 February 2010 lethal injection Margaret Peggy Park

70. Manuel Valle 28 September 2011 lethal injection Louis Pena

71. Oba Chandler 15 November 2011 lethal injection Joan Rogers, Michelle Rogers and Christe Rogers

72. Robert Waterhouse 15 February 2012 lethal injection Deborah Kammerer

73. David Alan Gore 12 April 2012 lethal injection Lynn Elliott

74. Manuel Pardo 11 December 2012 lethal injection Mario Amador, Roberto Alfonso, Luis Robledo, Ulpiano Ledo, Michael Millot, Fara Quintero, Fara Musa, Ramon Alvero, Daisy Ricard.

75. Larry Eugene Mann 10 April 2013 lethal injection Elisa Nelson

76. Elmer Leon Carroll 29 May 2013 lethal injection Christine McGowan

77. William Edward Van Poyck 12 June 2013 lethal injection Ronald Griffis

78. John Errol Ferguson 05 August 2013 lethal injection Livingstone Stocker, Michael Miller, Henry Clayton, John Holmes, Gilbert Williams, and Charles Cesar Stinson

79. Marshall Lee Gore 01 October 2013 lethal injection Robyn Novick (also killed Susan Roark but was executed for killing Novick)

80. William Frederick Happ 15 October 2013 lethal injection Angie Crowley

81. Darius Kimbrough 12 November 2013 Lethal Injection Denise Collins

82. Thomas Knight a/k/a Askari Abdullah Muhammad 7 January 2014 lethal injection Sydney and Lillian Gans, Florida Department of Corrections officer Richard Burke

83. Juan Carlos Chavez 12 February 2014 lethal injection Samuel James Ryce

84. Paul Augustus Howell 26 February 2014 lethal injection Trooper Jimmy Fulford

85. Robert Lavern Henry 20 March 2014 lethal injection Phyllis Harris, Janet Cox Thermidor

86. Robert Eugene Hendrix 23 April 2014 Elmer Bryant Scott Jr., Michelle Scott

87. John Ruthell Henry 18 June 2014 Suzanne Henry and Eugene Christian

Suzanne Henry's body was found in her home in the Pasco County town of Zephyrhills, Florida, at 4:20 p.m. on December 23, 1985. She had been stabbed thirteen times in the throat, and her body had been covered with a rug and left near the living room couch. Her son, five-year-old Eugene Christian, was missing. Within a short period of time, the sheriff's office discovered enough evidence to arrest John Ruthell Henry for his wife's murder.

The two chief investigators in the case were Pasco County detectives Fay Wilber and William McNulty. Wilber and McNulty tracked Henry to the Twilight Motel in Zephyrhills, where he was staying in a room with Rosa Mae Thomas. He was arrested shortly after midnight. Detective Wilber read Henry his Miranda rights, and asked about Eugene Christian. Henry denied knowing his whereabouts. Henry was taken to the Pasco County Sheriff's Office in Dade City for questioning. He was placed in a conference room. One wrist was handcuffed to a chair, but he was not otherwise restrained, and he was allowed to smoke cigarettes and drink coffee. Wilber had known Henry for a number of years, so it was decided that he would question him. While Wilber went to get coffee, however, McNulty attempted to talk to Henry, "to establish a rapport." McNulty said he understood Henry had "done some time before,'' to which Henry replied, "I am not saying nothing to you. Besides, you ain't read me nothing yet." McNulty reminded Henry that Wilber had read him his rights at the motel, and then asked where Eugene Christian was. After a few moments, Wilber came back with coffee, and McNulty left. On several occasions McNulty reentered the room to observe and participate in the questioning. McNulty never related Henry's statement to Wilber because he took it to mean that Henry simply did not wish to talk to him (McNulty). Upon reentering with the coffee, Wilber read Henry his Miranda rights, and Henry agreed to talk. Wilber and Henry talked over the course of more than three hours. Even then Henry did not confess.

Ultimately, Wilber said he was going to have to leave and find Eugene without Henry's help. At this point, Henry said Eugene was in Plant City. Wilber asked if the boy was alive, and Henry said he was not. Henry said he would take police to the site, and he did so. When the body was found, it appeared that the victim had been stabbed five times in the neck. Once the body was recovered, Henry was taken back to Dade City, where, after again being informed of his Miranda rights, he made a full confession concerning both murders.

Henry related that he had gone to his estranged wife's house before noon on December 22 to discuss what Christmas present to buy Eugene. While he was there they got into an argument over his living with Rosa Thomas. After he refused to leave, she attacked him with a kitchen knife. They "tussled" and after he was cut three times on his left arm, he "freaked out," took the knife away from her, and stabbed her. He then covered her body and went into another room to get Eugene, who had been watching television. Henry said that he then took Eugene with him and drove to Plant City, in Hillsborough County. They stopped for him to buy the boy a snack and later for him to buy some cocaine, before heading back toward Zephyrhills.

When Henry thought he saw flashing lights behind him, he said he turned into an isolated area near a chicken farm because he believed police were after him. When the car got stuck in some mud, Henry and Eugene got out and walked a short distance away. They stopped and Henry smoked his cocaine while holding Eugene on his knee. He then stabbed the boy to death and considered killing himself, but could not bring himself to do it. He walked around for awhile before dropping the knife in a field. Some nine hours had passed since he killed his wife. He walked back to Zephyrhills, went to Rosa Thomas' house, and changed clothes. The two then went to the motel. Henry said he did not know why he killed Suzanne and Eugene.

For the stabbing murder of his girlfriend, Patricia Roddy, Henry was sentenced to 15 years in prison in 1976 and was paroled in 1983. Patricia was 28 years old and she and her children were in a car with Henry when he stabbed her at least 20 times, killing her while one of her children begged him to stop hurting their mother. Suzanne's family said she was not aware of Henry's previous murder conviction.

UPDATE: "I can't undo what I've done. If I could, I would. I ask for your forgiveness if you can find it in your heart," John Henry said before the execution.

Florida Commission on Capital Cases

The Commission on Capital Cases was not funded in the FY 2011-2012 General Appropriations Act, and the Commission ceased operations on June 30, 2011. This site and the Commission website are being retained to provide access to historical materials. The Commission on Capital Cases updates this information regularly. This information, however, is subject to change and may not reflect the latest status of an inmate’s case and should not be relied upon for statistical or legal purposes.

HENRY, John (B/M)

DC# 053105

DOB: 01/16/51

Date of Offense: 12/22/85

Date of Sentence:05/08/87

Date Resentenced: 10/18/91

Sixth Judicial Circuit, Pasco County Case # 85-2685

Sentencing Judge: The Honorable Ray Ulmer

Trial Attorney: Robert Focht

Attorney, Direct Appeal: A. Anne Owens – Assistant Public Defender

Attorney, Collateral Appeals: Baya Harrison – Registry

Circumstances of the Offense:

John Henry murdered Suzanne Henry on December 22, 1985. Henry was married to Suzanne, however, was living with a different woman. On the day of the murder, Henry went to the house he had shared with Suzanne in Pasco County to discuss what presents he would get for Eugene Christian, her 5-year-old child from a previous marriage. An argument ensued concerning Henry’s present living situation and resulted in Henry stabbing Suzanne with a kitchen knife numerous times in the throat. He left the Pasco County house and took Christian with him. Henry drove to Hillsborough County with the child and, approximately nine hours later, killed Christian by stabbing him repeatedly in the throat with the same knife he killed Christian’s mother. Henry was first arrested for the murder of Suzanne and, when apprehended, admitted to knowing where Christian’s body was. Henry confessed to both murders and led police to the place in Hillsborough County where they found the child’s body.

01/16/86 Indicted with one count of First-Degree Murder

Retrial Summary:

10/11/91 Defendant was found guilty by the trial jury

Appeal Summary:

Florida State Supreme Court – Direct Appeal

Florida Supreme Court – Direct Appeal (resentencing)

United States Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Certiorari

State Circuit Court – 3.850 Motion

Florida Supreme Court – 3.850 Appeal

United States District Court, Middle District – Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

United States Court of Appeals, 11th Circuit—Habeas Appeal

Factors Contributing to the Delay in Imposition of Sentence: The Direct Appeal took three years for a decision to be rendered. The second Direct Appeal, which resulted from a new trial, took four years for a decision to be rendered. The Circuit Court 3.850 motion took five years for a decision to be rendered.

Case Information:

A Direct Appeal was filed on 07/06/87. Issues that were raised included whether the trial court erred in not granting his motion for acquittal because the state failed to present sufficient evidence of premeditation; whether the trial court erred in not suppressing Henry’s confession because during the course of the investigation he told one police officer that he did not wish to speak to him; whether the trial court erred in admitting extensive testimony and documentary evidence concerning the killing of Eugene Christian. The Florida Supreme Court found most of the claims either without merit or harmless. However, the Florida Supreme Court ruled that it was unnecessary to admit the abundant information concerning Christian’s murder and therefore reversed the conviction and sentence of death on 01/03/91 remanded the case for a new trial.

A second Direct Appeal was filed on 11/18/91. Issues that were raised included whether the trial court erred by allowing certain hearsay testimony relating to the murder of Henry’s first wife, whether the trial court erred in the instructing the jury on felony murder even though the trial court found that the murder was not committed during the course of a felony, and whether the trial court erred by failing to properly consider all mitigating evidence provided by the defense. The Florida Supreme Court found all claims either harmless or without merit and affirmed the conviction and sentence of death on 12/15/94.

A Petition for Writ of Certiorari was filed with the United States Supreme Court on 05/03/95 and denied on 10/02/95.

The 3.850 Motion was filed with the circuit court on 03/31/97 and was denied on 03/21/02.

A 3.850 Appeal was filed with the Florida Supreme Court on 05/24/02 and denied on 10/09/03.

A Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus was filed with the United States District Court, Middle District on 01/29/04. On 05/24/06, the USDC denied the petition.

On 06/12/06, Henry filed a Habeas Appeal in the United States Court of Appeals, 11th Circuit, which was denied on 07/31/07.

The Commission on Capital Cases updates this information regularly. This information, however, is subject to change and may not reflect the latest status of an inmate’s case and should not be relied upon for statistical or legal purposes.

Henry v. State, 574 So.2d 66 (Fla. 1991). (Direct Appeal-Reversed)

Defendant was convicted in the Circuit Court, in and for Hillsborough County, Donald C. Evans, J., of first-degree murder and sentenced to death, and he appealed. The Supreme Court held that: (1) continued questioning of suspect after he told detective “I'm not saying nothing to you. Besides, you ain't read me nothing yet” did not violate principles of Miranda as explained in Mosley, although suspect subsequently confessed; (2) striking defense of insanity upon defendant's failure to cooperate with expert who State sought to have examine defendant was not abuse of discretion; but in second per curiam opinion held that: (3) first-degree murder conviction and death sentence for killing of defendant's estranged wife's son would be reversed, as majority of justices believed that reversible error was committed in admitting defendant's confession or in striking defense of insanity upon defendant's failure to cooperate with prosecution expert, although majority did not agree that ruling on either of those points was error. Reversed and remanded. Shaw, C.J., filed opinion concurring in part and dissenting in part, agreeing with Barkett, J., opinion in part. McDonald, J., filed opinion concurring in part and dissenting in part. Barkett, J., filed dissenting opinion in which Kogan, J., concurred.

Henry v. State, 649 So.2d 1366 (Fla. 1994). (Direct Appeal-After Retrial)

Following reversal, 574 So.2d 73, of first-degree murder conviction and death sentence, defendant was again convicted in the Circuit Court, Pasco County, Maynard F. Swanson, Jr., J., of first-degree murder of his estranged wife and sentenced to death, and he appealed. The Supreme Court held that: (1) testimony concerning defendant's murder of estranged wife's son from previous marriage was admissible; (2) transcript of testimony of witness at defendant's first murder trial was admissible under former testimony exception to hearsay rule; (3) error in admission of testimony concerning autopsy report of defendant's murder of his first wife was harmless; (4) any error in allowing jury to consider aggravating factor that murder was committed during course of felony was harmless; (5) trial court properly considered mitigating evidence presented by defense; (6) finding of aggravating circumstance that murder was especially heinous, atrocious or cruel was supported by testimony; and (7) death sentence was not disproportionate. Affirmed.

PER CURIAM.

John Ruthell Henry appeals his conviction for the first-degree murder of Suzanne Henry and his resulting sentence of death. We have jurisdiction under article V, section 3(b)(1) of the Florida Constitution.

Henry was married to Suzanne Henry but they were separated. Shortly before Christmas 1985, he returned home in Pasco County to talk with his wife. The couple began to argue and the dispute ended with Henry killing Suzanne by stabbing her repeatedly in the throat. Henry then took Eugene Christian, Suzanne's five-year-old son from a previous marriage, from the house and drove to Hillsborough County where, some nine hours later, he killed Christian by stabbing him in the throat. Henry was convicted of the first-degree murders of Suzanne Henry and Eugene Christian in separate trials and received a sentence of death for each murder. Subsequently, this Court reversed both convictions and sentences. Henry v. State, 574 So.2d 73 (Fla.1991); Henry v. State, 574 So.2d 66 (Fla.1991). Regarding the murder of Suzanne Henry, we found that the trial court erred in admitting extensive testimony and documentary evidence concerning Eugene Christian's murder. Henry, 574 So.2d at 75. On retrial, Henry was again convicted of the first-degree murder of Suzanne Henry.FN1 The jury recommended the death penalty by a vote of twelve to zero and the trial court followed the jury's recommendation. The court found two aggravating circumstances FN2 and no mitigating circumstances. This appeal followed.

FN1. On retrial for the murder of Eugene Christian, Henry was also again convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death. The subsequent appeal for that conviction and sentence is discussed in another opinion. Henry v. State, 649 So.2d 1361 (Fla.1994). FN2. The trial court found that: (1) Henry had previously been convicted of a violent felony; and (2) the murder was especially heinous, atrocious or cruel.

Henry argues that the trial court erred in allowing any testimony concerning the murder of Eugene Christian. Prior to the State's case-in-chief, defense counsel made a motion in limine to exclude any mention whatsoever of the killing of Eugene Christian. The trial court refused the defense's request to disallow any mention of Christian or his death. However, the court did prohibit the State from presenting in-depth testimony about the search for Christian's body, the autopsy photo, or the manner in which he was killed. The court also gave a limiting instruction for the jury's consideration of the evidence admitted pertaining to Christian.

During the course of the trial, reference was made to the following facts: Christian was last seen at Suzanne Henry's house on the day of her murder; Christian was missing from the house the day her body was found; Christian left Suzanne Henry's house on the day of her murder with an unknown person; Henry led police to the place where Christian's body was found; and Henry confessed to killing Christian. Henry argues that this evidence was not relevant to any material fact in issue and therefore should not have been admitted. We disagree.

The facts in question relating to Eugene Christian's murder were inextricably intertwined with facts pertaining to Suzanne Henry's murder. To try to totally separate the facts of both murders would have been unwieldy and likely have led to confusion. See Henry, 574 So.2d at 70–71; Griffin v. State, 639 So.2d 966 (Fla.1994); Tumulty v. State, 489 So.2d 150 (Fla. 4th DCA), review denied, 496 So.2d 144 (Fla.1986). As we stated in our opinion in Henry's first appeal, “[s]ome reference to the boy's killing may have been necessary to place the events in context, to describe adequately the investigation leading up to Henry's arrest and subsequent statements, and to account for the boy's absence as a witness.” Henry, 574 So.2d at 75. We find that the evidence relating to Eugene Christian's whereabouts during and after his mother's murder, as well as the fact that Henry admitted killing Christian, was indeed necessary to establish the context of events and to describe the investigation leading up to Henry's arrest for Suzanne Henry's murder and the subsequent confession. The evidence was relevant to prove Henry's presence at the scene of the murder. The evidence concerning the briar bushes where Christian's body was found refuted Henry's claim that the cuts on his arms came from Suzanne Henry's attack with a knife. The act of removing the only person present in the house where Christian was killed also tended to prove guilty knowledge. Because the facts regarding Christian were inseparable crime evidence, we find that no error was made in their admission.

Henry also raises several issues pertaining to the penalty phase of his trial. He first asserts that the trial court erred by allowing certain hearsay testimony relating to the murder of his first wife, Patricia Roddy. FN3 At the trial, the State introduced the transcript of testimony of Deborah Fuller, who had been a witness at Henry's first murder trial. At the time of the trial in the instant case, Fuller was unavailable and incarcerated in another state. Henry argues that because he had no opportunity to cross-examine Fuller in this instance, it was error to admit the transcript. He also argues that the transcript of testimony was irrelevant and highly prejudicial and therefore error pursuant to Rhodes v. State, 547 So.2d 1201 (Fla.1989). In Rhodes, we held that playing a tape recording of a prior victim, who was unavailable for cross-examination, describing her physical and emotional trauma and suffering was irrelevant, highly prejudicial and, therefore, inadmissible. Rhodes, 547 So.2d at 1205. FN3. In 1976 Henry pled guilty to second-degree murder for the stabbing death of Patricia Roddy.

The transcript of Fuller's testimony was admissible for two reasons. First, the transcript qualifies under the former testimony exception to the hearsay rule. § 90.804(2)(a), Fla.Stat. (1991). Under this exception, if a declarant is unavailable as a witness, testimony given by the declarant at another proceeding is admissible if the party against whom the testimony is now offered had an opportunity to cross-examine the declarant. Since Fuller was unavailable as a witness at the trial in this case, and Henry had an opportunity to rebut her testimony during the first trial, we find that the transcript falls within this exception. Next, this Court has specifically held that details of prior felony convictions involving the use of violence to the victim are admissible in the penalty phase of the trial. Waterhouse v. State, 596 So.2d 1008 (Fla.), cert. denied, 506 U.S. 957, 113 S.Ct. 418, 121 L.Ed.2d 341 (1992). Fuller was an eyewitness to the altercation between Henry and Roddy which led up to Roddy's murder as well as to the murder itself. Such testimony is unlike the emotionally charged hearsay testimony made by a prior victim who was unavailable for cross-examination and found inadmissible in Rhodes. Therefore, we do not find that the trial court abused its discretion in admitting the transcript.

Henry further argues that the testimony concerning the autopsy report of the Roddy murder was It was unnecessary to establish the aggravating factor of prior violent felony. We are inclined to agree with Henry on this point. Other testimony concerning the Roddy murder was more than sufficient to establish the aggravating circumstance that Henry had previously been convicted of a violent felony.FN4 See Rhodes, 547 So.2d at 1205 n. 6. However, because there is no reasonable possibility that the outcome of the trial would have been different in the absence of this error, we find it to be harmless. State v. DiGuilio, 491 So.2d 1129 (Fla.1986).

FN4. In addition to the Fuller transcript and the medical examiner's testimony, the State also introduced the testimony of Gloria Nix who was an eyewitness to Roddy's killing as well as the testimony of Leonard Harris, the police investigator who investigated the Roddy crime scene. Also, Detective Fay Wilber, who arrested Henry for Roddy's murder, testified that Henry had pled guilty and been convicted of second-degree murder.

Henry next argues that since the trial court did not find that the murder was committed during the course of a felony, the court erred in instructing the jury on this aggravating factor. We reject Henry's argument. If evidence of an aggravating factor has been presented to a jury, an instruction on the factor is required. Bowden v. State, 588 So.2d 225, 231 (Fla.1991), cert. denied, 503 U.S. 975, 112 S.Ct. 1596, 118 L.Ed.2d 311 (1992). The fact that the aggravator was not ultimately found to exist does not mean there was insufficient evidence to allow the jury to consider the factor. Id. In the instant case, testimony was presented at trial that Suzanne Henry had gold jewelry which she kept in her jewelry box or purse and that the jewelry was missing after the murder. Evidence was also presented that Henry did not have any money immediately prior to the murder, but shortly thereafter purchased cocaine. Henry's girlfriend testified that Henry had sold some jewelry to purchase the cocaine. We find that the foregoing constitutes sufficient evidence to present the issue of murder during the commission of a felony to the jury. Even if there was no basis for the aggravator, any error would be harmless because the jury was properly instructed and the trial court did not find that the circumstance existed. Sochor v. Florida, 504 U.S. 527, 112 S.Ct. 2114, 119 L.Ed.2d 326 (1992); Johnson v. Singletary, 612 So.2d 575 (Fla.), cert. denied, 508 U.S. 901, 113 S.Ct. 2049, 123 L.Ed.2d 667 (1993).

We also reject Henry's argument that the trial judge failed to properly consider all the mitigating evidence presented by the defense. The judge pointed out in the sentencing order that none of the doctors who testified at the trial believed that the statutory mental mitigating circumstances applied to Henry. Further, there is no indication that the judge failed to consider any nonstatutory mitigation brought to his attention by the defense, and the minimal evidence Henry now points to as mitigating could hardly ameliorate the enormity of his guilt. Lucas v. State, 568 So.2d 18 (Fla.1990).

Henry's argument that the evidence did not support the finding that the murder was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel also fails. Testimony shows that Henry sat on Suzanne Henry, beat her, and held her head back while he stabbed her thirteen times in the neck. Testimony also revealed that Suzanne Henry was conscious from three to five minutes after the last wound was inflicted. This Court has consistently held that the heinous, atrocious, or cruel factor applies to murders where the victim was repeatedly stabbed. Floyd v. State, 569 So.2d 1225 (Fla.1990), cert. denied, 501 U.S. 1259, 111 S.Ct. 2912, 115 L.Ed.2d 1075 (1991); Nibert v. State, 508 So.2d 1 (Fla.1987); Lusk v. State, 446 So.2d 1038 (Fla.), cert. denied, 469 U.S. 873, 105 S.Ct. 229, 83 L.Ed.2d 158 (1984). Given the facts of the case at bar, the trial court properly found this aggravating circumstance.

We also disagree with Henry's claim that his death sentence is disproportionate to his crime because of the mitigating evidence he introduced. As stated above, the trial court did not err in rejecting that evidence. Henry also argues that because the killing resulted from a domestic dispute, the death penalty is inappropriate. However, under the circumstances of this case, and in comparison with other death cases, we find Henry's death sentence to be proportionate. See, e.g., Lemon v. State, 456 So.2d 885 (Fla.1984) (defendant killed ex-girlfriend after previous conviction for similar offense), cert. denied, 469 U.S. 1230, 105 S.Ct. 1233, 84 L.Ed.2d 370 (1985); King v. State, 436 So.2d 50 (Fla.1983) (defendant killed wife who was seeking divorce, with the Court finding two aggravating and no mitigating factors) cert. denied, 466 U.S. 909, 104 S.Ct. 1690, 80 L.Ed.2d 163 (1984); Harvard v. State, 414 So.2d 1032 (Fla.1982) (defendant killed former wife and Court found two aggravating and no mitigating factors), cert. denied, 459 U.S. 1128, 103 S.Ct. 764, 74 L.Ed.2d 979 (1983).

We therefore affirm the conviction of first-degree murder and the sentence of death. It is so ordered. GRIMES, C.J., OVERTON, SHAW, KOGAN and HARDING, JJ., and McDONALD, Senior Justice, concur.

Henry v. State, 862 So.2d 679 (Fla. 2003). (PCR)

Defendant was convicted of murder and sentenced to death. He appealed, and the Supreme Court, 574 So.2d 73, reversed and remanded for new trial. On retrial, defendant was again convicted of capital murder and sentenced to death, and he appealed. The Supreme Court, 649 So.2d 1366, affirmed. Defendant then filed motion for postconviction relief. The Circuit Court, Pasco County, Maynard F. Swanson, Jr., J., denied motion after hearing, and defendant appealed. The Supreme Court held that: (1) retrial counsel's reliance on theories of self-defense and depraved mind did not constitute ineffective assistance; (2) counsel's failure to present voluntary intoxication defense did not constitute ineffective assistance; (3) counsel's decision not to present mental health mitigation evidence during sentencing did not amount to ineffective assistance; and (4) imposition of death sentence based on finding of statutory aggravating factor that defendant had prior conviction for violent felony as included in indictment complied with Ring. Affirmed. Anstead, C.J., specially concurred, with opinion.

PER CURIAM.

John Ruthell Henry appeals a circuit court order denying, after an evidentiary hearing, his motion for postconviction relief filed under Florida Rule of Criminal Procedure 3.850. We have jurisdiction. See art. V, § 3(b)(1), Fla. Const. Having considered the issues raised in the briefs and having heard oral argument in this case, we affirm the order.

I. Facts

In 1985, during a dispute over Christmas presents for his wife's son, Henry stabbed his estranged wife in the throat thirteen times. He was tried, convicted, and sentenced to death. This Court reversed and remanded for new trial. Henry v. State, 574 So.2d 73 (Fla.1991). Upon retrial, Henry was again convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death. On appeal, this Court affirmed. Henry v. State, 649 So.2d 1366 (Fla.1994), cert. denied, 515 U.S. 1148, 115 S.Ct. 2591, 132 L.Ed.2d 839 (1995). FN1. After killing his wife, Henry took her five-year old son from her Pasco County home to Hillsborough County, where he killed the child by stabbing him in the throat. On appeal, this Court reversed for new trial. Henry v. State, 574 So.2d 66 (Fla.1991). Henry was again convicted and sentenced to death on retrial, and this Court affirmed on direct appeal. Henry v. State, 649 So.2d 1361 (Fla.1994), cert. denied, 516 U.S. 830, 116 S.Ct. 101, 133 L.Ed.2d 55 (1995). That case is not part of this appeal from denial of postconviction relief from the Pasco County murder conviction.

In his postconviction motion, Henry alleged that his retrial counsel was ineffective during the guilt phase of trial for failing to present evidence of Henry's mental state at the time of the offense, and particularly for relying on the theories of self-defense and diminished capacity and not presenting the defenses of insanity or voluntary intoxication. He also contended that counsel was ineffective during the penalty phase for failing to present available mental health mitigating evidence.FN2 Several months after the evidentiary hearing, appellant filed a motion requesting the court either to take judicial notice that the United States Supreme Court had accepted jurisdiction in State v. Ring, 200 Ariz. 267, 25 P.3d 1139 (2001), rev'd, 536 U.S. 584, 122 S.Ct. 2428, 153 L.Ed.2d 556 (2002), or permit amendment of the postconviction motion with a claim that the Florida death penalty statute is unconstitutional. The court denied that motion and later denied Henry's postconviction motion. The lower court found retrial defense counsel's conduct was “reasonable and within the wide range of professional assistance required in a capital case.” FN2. Appellant also claimed that counsel was ineffective for failing to seek a change of venue, but later abandoned that claim.

On appeal Henry raises five issues: (1) and (2) that retrial counsel was ineffective during the guilt phase of trial and that appellant was prejudiced thereby; (3) and (4) that retrial counsel was ineffective during the penalty phase of trial and appellant was prejudiced thereby; and (5) that Florida's death penalty statute is unconstitutional under Ring v. Arizona, 536 U.S. 584, 122 S.Ct. 2428, 153 L.Ed.2d 556 (2002). We address each of these claims below.

II. Ineffective Assistance During the Guilt Phase

To prevail on a claim that defense counsel provided ineffective assistance, a defendant must demonstrate specific acts or omissions of counsel that are “so serious that counsel was not functioning as the ‘counsel’ guaranteed the defendant by the Sixth Amendment.” Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 687, 104 S.Ct. 2052, 80 L.Ed.2d 674 (1984). The defendant also must demonstrate prejudice by “show[ing] that there is a reasonable probability that, but for counsel's unprofessional errors, the result of the proceeding would have been different. A reasonable probability is a probability sufficient to undermine confidence in the outcome.” Id. at 694, 104 S.Ct. 2052. Ineffective assistance of counsel claims present mixed questions of law and fact subject to plenary review, and this Court independently reviews the trial court's legal conclusions, while giving deference to the trial court's factual findings. Occhicone v. State, 768 So.2d 1037, 1045 (Fla.2000).

Henry contends that retrial counsel was ineffective for relying on the theories of self-defense and diminished capacity, which were not viable, and that he was prejudiced because another viable defense was available. Each aspect of this claim fails.

A. The Self-Defense Theory

Henry first argues that no evidence supported the theory of self-defense used at trial. The record conclusively rebuts this argument. In his statement to police, Henry said he went to his estranged wife's house to discuss Christmas presents for her son. They argued, and she attacked him, cutting him three times with a kitchen knife. Henry then struggled with her and took the knife away. He “freaked out” and stabbed her thirteen times. An officer took pictures of Henry's wounds, but threw them away because they were unclear.

Henry contends that self-defense was not an available defense because he stabbed his wife many times and the police presented evidence contradicting that theory, such as the officer's testimony that the scratches on Henry's arm appeared to be made by thorns, not knives. Retrial counsel testified, and the record shows, however, that during trial he elicited evidence of the victim's violent nature and that the victim attacked Henry first. Thus, self-defense was consistent with Henry's version of events, and evidence existed to support it. In fact, counsel presented enough evidence of self-defense to justify a jury instruction on it.

Further, at the evidentiary hearing retrial counsel admitted that self-defense was an imperfect defense because of the repeated stabbing, but he stated that his defense strategy was twofold. See Lusk v. State, 498 So.2d 902, 905 (Fla.1986) (holding “trial counsel's decision to rely on self-defense here was a strategic choice which did not fall outside the acceptable range of competent choices” and stating that “[c]onsidering all the circumstances ... self-defense was arguably the only viable choice”). Counsel also argued for a depraved mind, second-degree murder conviction by emphasizing Henry's response to his wife's attack as a blinding rage. Accordingly, Henry has failed to meet the first prong of Strickland as to this part of the claim.

B. The Diminished Capacity Theory

Henry next argues that retrial counsel erroneously relied on a “diminished capacity” defense, which Florida law does not recognize. See State v. Bias, 653 So.2d 380, 382 (Fla.1995); Chestnut v. State, 538 So.2d 820, 821-25 (Fla.1989). The record conclusively rebuts this claim as well. In closing argument, retrial counsel emphasized that when Henry's wife cut him with a knife Henry “freaked out,” and counsel argued that Henry was “blinded of what happened next.” He told the jury the judge would instruct on manslaughter “and second-degree murder talking about the depraved mind, not requiring premeditation.” At the evidentiary hearing below, retrial counsel explained that he sought to show the offense to be a “mindless, non-premeditated killing,” to obtain a “depraved mind,” second-degree murder conviction. Henry's claim is based on retrial counsel's apparent misuse of the term “diminished capacity” in a written response to an inquiry from Henry's postconviction counsel. Both the trial transcript and the testimony of retrial counsel at the evidentiary hearing, however, demonstrate that counsel used a depraved mind, not a diminished capacity, defense at retrial.

C. The Lack of Premeditation Theory

Finally, Henry urges that retrial counsel failed to present the defense that Henry was incapable of forming the premeditated intent to kill Suzanne because of his abuse of crack cocaine before the murder, which exacerbated his underlying psychotic mental condition. Henry claims that such a defense was available under Gurganus v. State, 451 So.2d 817 (Fla.1984). However, we have explained that “ Gurganus simply reaffirmed the long-standing rule in Florida that evidence of voluntary intoxication is admissible in cases involving specific intent.” Chestnut, 538 So.2d at 822. As we said in State v. Bias, Gurganus stands for the principle that “it is proper for an expert to testify ‘as to the effect of a given quantity of intoxicants' on the mind of the accused when there is sufficient evidence in the record to show or support an inference of the consumption of intoxicants.” 653 So.2d at 383. Thus an expert “may need to explain why a certain quantity of intoxicants causes intoxication in the defendant whereas it would not in other individuals.” Id.

To the extent that Henry's claim can be construed as alleging that retrial counsel should have used a voluntary intoxication defense, he fails to demonstrate error. Henry failed to present any evidence that he was actually intoxicated at the time of the offense. See Rivera v. State, 717 So.2d 477, 485 n. 12 (Fla.1998); see also Linehan v. State, 476 So.2d 1262, 1264 (Fla.1985) (“We emphasize that voluntary intoxication is an affirmative defense and that the defendant must come forward with evidence of intoxication at the time of the offense sufficient to establish that he was unable to form the intent necessary to commit the crime charged.”). In fact, retrial counsel testified that a defense mental health expert advised him that the defense case was weak on the issue of specific intent, and Henry did not present any evidence that the mental health experts retrial counsel contacted-or anyone else-would have testified that Henry was intoxicated at the time of the offense with or without regard to any underlying mental condition.

We note, however, that we are unable to discern any difference between Henry's claim and the defense asserted in Easley v. State, 629 So.2d 1046 (Fla. 2d DCA 1993), of which we disapproved in Bias, 653 So.2d at 383. We held in Bias that a psychiatrist's testimony that it “was the combination of Easley's use of alcohol and drugs superimposed on her long-standing depression that rendered her incapable of formulating a specific intent to kill on the night in question,” id. (quoting Easley, 629 So.2d at 1050), was inadmissible because it “constituted evidence of the defendant's diminished capacity.” Id. Therefore, to the extent Henry argues that the inadmissible defense of diminished capacity was available, the claim fails.

The record shows that the defenses presented by retrial counsel were valid and supported by the evidence. Henry's proposed alternative theory of defense is either unsupported by the evidence (voluntary intoxication) or inadmissible (diminished capacity). Thus, Henry's entire claim amounts to no more than disagreement with retrial counsel's strategy, without offering a valid theory of his own. See Occhicone, 768 So.2d at 1048 (noting that “[c]ounsel cannot be deemed ineffective merely because current counsel disagrees with trial counsel's strategic decisions”). Because Henry has failed to establish the first prong of the Strickland standard (deficient performance of counsel), we need not address the second prong (prejudice). See Strickland, 466 U.S. at 697, 104 S.Ct. 2052 (“[T]here is no reason for a court deciding an ineffective assistance claim ... to address both components of the inquiry if the defendant makes an insufficient showing on one.”).

III. Ineffective Assistance in the Penalty Phase

Henry argues that trial counsel was ineffective for failing to present available mental health mitigation evidence during the penalty phase and that, had counsel presented such evidence, the result probably would have been different. To put this claim in context, we first review the facts in the record.

During the penalty phase of Henry's first trial for the murder of his estranged wife, a forensic psychologist and a psychiatrist (Drs. Berland and Afield) testified on Henry's behalf after conducting psychological testing, interviewing Henry and at least one family member, reading depositions, examining hospital records, and reviewing police reports. Dr. Berland testified that Henry had a low IQ (78) and was “actively psychotic” at the time of the murder. Dr. Afield testified that Henry had a severe problem with alcohol and drug abuse and suffered from long-term, very severe, chronic paranoia. He agreed that Henry was psychotic at the time of the murder, but also said that Henry could distinguish right from wrong. Both doctors testified that two statutory mitigating factors applied: Henry was substantially impaired in his ability to conform his behavior to the requirements of law, and at the time of the offense he was under the influence of an extreme emotional disturbance. Both doctors, however, testified that the cocaine and alcohol use of which Henry had told them was not the basis for their conclusions and that such drug use would only have worsened his psychotic condition.

Despite this testimony, the jury in the first trial unanimously recommended death. The court sentenced Henry to death, finding three aggravators-previous conviction of a violent felony (Henry also had stabbed his first wife to death); the murder was heinous, atrocious, and cruel (HAC); and it was cold, calculated, and premeditated (CCP). Despite the defense experts' testimony, the trial court found no mitigating factors. This Court reversed because unfairly prejudicial evidence of Henry's murder of his wife's son was admitted at trial. We noted for retrial purposes that the evidence did not support the trial court's finding of the CCP aggravator. Henry v. State, 574 So.2d 73, 74-75 (Fla.1991).

Upon retrial, Henry's new defense counsel did not present the mental health experts during the penalty phase. Instead, he presented Henry's girlfriend (Rosa Mae Thomas), with whom he was living at the time of the murder, and her daughter. Henry's girlfriend testified that Henry's estranged wife came to her home on several occasions and argued with Henry. On one occasion, she physically attacked Henry. Police officers arrested her after first having to pull her off him. Thomas was aware of Henry's problems with drugs and alcohol, but said that he was a loving man and a good provider and that they never argued. Thomas's daughter testified that life was pleasant while Henry lived with them, and she was never afraid of him, even though she knew he had killed his first wife. She also described the arguments between Henry and his wife when she came to their home and his wife's violence, to which Henry never responded. She was also aware that Henry smoked crack cocaine while he lived with them.

The jury in the second trial unanimously recommended death, and the court sentenced Henry to death. Henry v. State, 649 So.2d 1366, 1367 (Fla.1994). The court found two aggravating factors-a previous violent felony conviction (killing his first wife) and HAC-and no mitigating circumstances. Id. at 1367 n. 2.

At the evidentiary hearing on Henry's claim, Dr. Mosman, a forensic psychologist, testified to the mitigating evidence he said was available at the time of trial from his review of the records of the previous mental health experts and other records and from his conversation with Dr. Berland. He opined that the mental health experts should have testified at retrial. Retrial counsel then testified that when he undertook Henry's representation, he obtained and familiarized himself with all the files from the previous trial, including the mental health examinations, reports, depositions, and trial transcripts. He also spoke with the mental health experts. He was aware of the mental health evidence presented in both the prior Pasco County trial and in the prior Hillsborough County trial (for the child's murder), and the result in that case.FN3 He was aware of Henry's difficult childhood, his long-time substance abuse, and the problems and violence in his marriage. Counsel specifically chose not to present mental health mitigation through experts because he believed their testimony at the first trial was more devastating than helpful, especially Dr. Afield's testimony that Henry was a very dangerous man. He found that the prosecutor succeeded in essentially turning these witnesses against Henry and said that their testimony was a two-edged sword. He decided instead to present evidence that Henry was a nonviolent, peaceful individual through testimony of people who actually lived in a home with Henry and did not feel threatened by him, and to try to establish some mental-health mitigation through these witnesses and cross-examination.

FN3. In the first trial in the Hillsborough County Case, the jury recommended death by a vote of 10-2, and the court sentenced Henry accordingly. 574 So.2d at 69. The court found four aggravating factors: (1) previous second-degree murder conviction (Henry's murder of his first wife); (2) the killing was committed in the course of a kidnaping; (3) the killing was committed to avoid or prevent arrest or escape custody; and (4) CCP. Based on Drs. Berland and Afield's testimony, the trial court found two statutory mitigating factors: that Henry was under the influence of extreme mental or emotional disturbance and his capacity to appreciate the criminality of his conduct or conform it to the requirements of law was substantially impaired.

We have stated that defense counsel's reasonable, strategic decisions do not constitute ineffective assistance if alternative courses have been considered and rejected. State v. Bolender, 503 So.2d 1247, 1250 (Fla.1987). A reasonable, strategic decision is based on informed judgment. See Wiggins v. Smith, 539 U.S. 510, ----, 123 S.Ct. 2527, 2538, 156 L.Ed.2d 471 (2003) (finding counsel's decision “to abandon their [mitigation] investigation at an unreasonable juncture ma[de] a fully informed decision with respect to sentencing strategy impossible”). Accordingly, we determine not whether counsel should have presented mental health mitigation but whether counsel's decision not to present such evidence was a reasonably informed, professional judgment. See id. at 2536 (where petitioner claimed counsel were constitutionally ineffective for failing to investigate and present mitigating evidence, stating “our principal concern ... is not whether counsel should have presented a mitigation case” but “whether the investigation supporting counsel's decision not to introduce mitigating evidence ... was itself reasonable.”).FN4 The evidence from the evidentiary hearing demonstrates that retrial counsel knew about the mental health testimony available through Drs. Berland and Afield, but concluded that their testimony was likely to do more harm than good. He decided instead to try to humanize Henry through testimony that Henry was a peaceful man through people who actually knew and lived with Henry. Retrial counsel's decision was a reasonable strategy after full consideration of the alternative. See Rutherford v. State, 727 So.2d 216, 223 (Fla.1998) (finding no error where retrial counsel was aware of mental mitigation “but made a strategic decision under the circumstances ... to instead focus on the ‘humanization’ of Rutherford through lay testimony”); Haliburton v. Singletary, 691 So.2d 466, 471 (Fla.1997) (finding no deficient performance in counsel's decision to humanize the defendant rather than use mental health testimony because the expert would say that the defendant was “dangerous” and likely would kill again); Bryan v. Dugger, 641 So.2d 61, 64 (Fla.1994) (finding counsel not ineffective for choosing a mitigation strategy of “humanization” and not calling a mental health expert).

FN4. In Wiggins, the Court emphasized that “ Strickland does not require counsel to investigate every conceivable line of mitigating evidence no matter how unlikely the effort would be to assist the defendant at sentencing”; neither does it “require defense counsel to present mitigating evidence at sentencing in every case.” Wiggins, 123 S.Ct. at 2541.

In addition, retrial counsel had the advantage of knowing that the strategy Henry proposes failed at the first trial, where despite the mental health mitigation testimony of the two defense experts, the trial court found no mitigation, and the jury unanimously recommended death. Even considering that the first jury had received a prejudicial amount of information about the murder of the child in the guilt phase and that this Court found the CCP aggravator inapplicable for purposes of retrial, retrial counsel felt that the fact that the first trial court did not find any mitigating factors was telling. FN5. Counsel was further aware that the mental-health mitigation was presented during the penalty phase of Henry's first Hillsborough County trial, and even though the trial court found some mitigating factors, the jury recommended, and the trial court sentenced Henry to, death. 574 So.2d at 67, 69.