Executed September 20, 2012 06:43 p.m. CDT by Lethal Injection in Texas

29th murderer executed in U.S. in 2012

1306th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

8th murderer executed in Texas in 2012

485th murderer executed in Texas since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(29) |

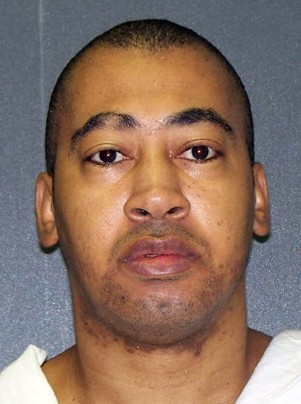

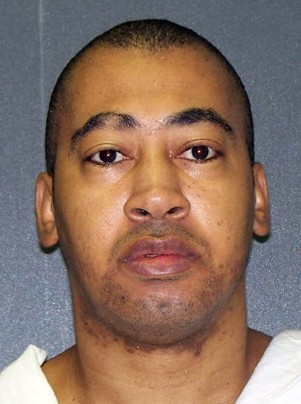

Robert Wayne Harris B / M / 28 - 40 |

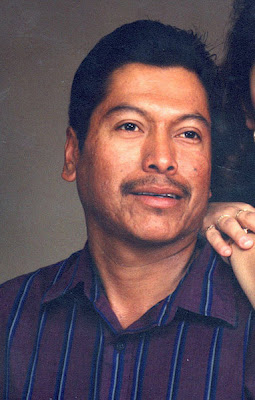

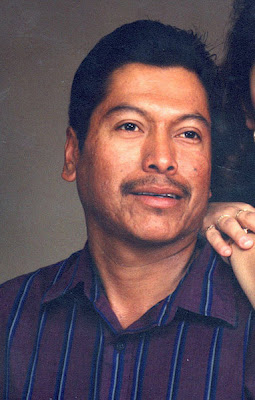

Dennis Lee W / M / 48 Agustin Villasenor H / M / 36 Rhoda Wheeler W / F / 46 Benjamin Villasenor H / M / 32 Roberto Jimenez Jr. H / M / 15 |

Harris had three previous convictions for burglary of a building. He was sentenced to five years in prison on two counts in May 1991 and eight years on a third count in June 1991. He was paroled in May 1999 and discharged in June. Harris also had a history of assault and battery and drug dealing. Testimony at Harris's punishment hearing indicated that on the day he was arrested for the car wash murders, he was planning to drive to Florida to kill an old girlfriend.

Citations:

Harris v. State, Not Reported in S.W.3d, 2003 WL 1793023 (Tex.Cr.App. 2003). (Direct Appeal)

Harris v. Thaler, 464 Fed.Appx. 301 (5th Cir. 2012). (Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

Texas no longer offers a special "last meal" to condemned inmates. Instead, the inmate is offered the same meal served to the rest of the unit.

Final/Last Words:

In his last statement, Harris expressed love and comfort to his brother and three friends who attended his execution. "I'm going home. I'm going home," he said. He did not look in the direction of the friends and relatives of his victims, who watched from another room. "Don't worry about me," he said. "I'll be alright. God bless, and the Texas Rangers, Texas Rangers."

Internet Sources:

Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Executed Offenders (Wilson)

Robert Wayne Harris

Date of Birth: 2/28/1972

DR#: 999364

Date Received: 10/6/2000

Education: 9 years

Occupation: Laborer

Date of Offense: 3/20/2000

County of Offense: Dallas

Native County: Dallas

Race: Black

Gender: Male

Hair Color: Black

Eye Color: Brown

Height: 6' 00"

Weight: 182

Prior Prison Record:

8 year sentence from Dallas County for 3 counts of burglary of a building. 5/3/1999 released on mandatory supervision. Discharged 6/27/1999.

Summary of incident: On 3/20/2000 at a car wash in Irving, Harris entered his former place of employment and began shooting co-workers. Harris had been fired three days prior to the shooting after exposing himself to two women. Five people were killed during the shooting. After the shooting, Harris fled the scene on foot.

Co-Defendants: None.

Monday, September 17, 2012

Media Advisory: Robert W. Harris scheduled for execution

DALLAS – Pursuant to a court order by the 282nd District Court in Dallas County, Robert Wayne Harris is scheduled for execution after 6 p.m. on September 20, 2012. In 2000, a Dallas County jury convicted Harris of capital murder for killing Agustin Villasenor and Rhoda Wheeler during the same criminal transaction.

FACTS OF THE CASE

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, citing the Texas Court of Criminal Appeal’s description of the facts, described the murder of Agustin Villasenor and Rhoda Wheeler as follows:

[Harris] worked at Mi-T-Fine Car Wash for ten months prior to the offense. An armored car picked up cash receipts from the car wash every day except Sunday. Therefore, [Harris] knew that on Monday morning, the safe would contain cash receipts from the weekend and the cash register would contain $200-$300 for making change. On Wednesday, March 15, 2000, [Harris engaged in sexual misconduct] in front of a female customer. The customer reported the incident to a manager, and a cashier called the police. [Harris] was arrested and fired. On Sunday, March 19[th], [Harris] spent the day with his friend, Junior Herrera, who sold cars. Herrera was driving a demonstrator car from the lot. Although [Harris] owned his own vehicle, he borrowed Herrera’s that evening. He then went to the home of friend Billy Brooks, who contacted his step-son, Deon Bell, to lend [Harris] a pistol.

On Monday, March 20[th], [Harris] returned to the car wash in the borrowed car at 7:15 a.m., before it opened for business. [Harris] forced the manager, Dennis Lee, assistant manager, Agustin Villaseñor, and cashier, Rhoda Wheeler, into the office. He instructed Wheeler to open the safe, which contained the cash receipts from the weekend. Wheeler complied and gave him the cash. [Harris] then forced all three victims to the floor and shot each of them in the back of the head at close range. He also slit Lee’s throat.

Before [Harris] could leave, three other employees arrived for work unaware of the danger. [Harris] forced them to kneel on the floor of the lobby area and shot each of them in the back of the head from close range. One of the victims survived with permanent disabilities. Shortly thereafter, a seventh employee, Jason Shields, arrived. Shields noticed the three bodies in the lobby and saw [Harris] standing near the cash register. After a brief exchange in which [Harris] claimed to have discovered the crime scene, pointed out the bodies of the other victims, and pulled a knife from a nearby bookshelf, Shields became nervous and told [Harris] he needed to step outside for fresh air. Shields hurried to a nearby doughnut shop to call authorities. [Harris] followed Shields to the doughnut shop, also spoke to the 911 operator, then fled the scene.

[Harris] returned the vehicle to Herrera and told him that he had discovered some bodies at the car wash. [Harris] then took a taxi to Brooks’s house. At Brooks’s house, [Harris] separated the money from the other objects and disposed of the metal lock boxes, a knife, a crowbar, and pieces of a cell phone in a wooded area. [Harris] purchased new clothing, checked into a motel, and sent Brooks to purchase a gold cross necklace for him. Later that afternoon, [Harris] drove to the home of another friend and remained there until the following morning, when he was arrested. Testimony also showed that [Harris] had planned to drive to Florida on Tuesday and kill an old girlfriend.

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

On April 10, 2000, Harris was indicted Harris for the murder of Agustin Villasenor and Rhoda Wheeler.

On September 29, 2000, a Dallas County jury found Harris guilty of murdering Agustin Villasenor and Rhoda Wheeler. After the jury recommended capital punishment, the court sentenced Harris to death by lethal injection.

On February 12, 2003, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed Harris’s conviction and sentence.

On October 6, 2003, the U.S. Supreme Court denied writ of certiorari.

On July 1, 2002, Harris sought a writ of habeas corpus with the state trial court.

On June 3, 2004, the trial court recommended that Harris’s application be denied.

On September 15, 2004, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals denied habeas relief.

On September 14, 2005, Harris filed a federal petition for a writ of habeas corpus.

On September 10, 2008, the district court ordered an evidentiary hearing set on retardation claim.

On November 13, 2009 the court ordered an independent evaluation of Harris.

On March 24, 2011, the district court denied Harris’s habeas petition and refused to issue a COA.

On April 21, 2011, Harris filed a motion to alter or amend the judgment in the district court.

On April 25, 2011 the district court denied Harris’s motion.

On March 15, 2012, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit denied the COA.

On August 27, 2012, Harris filed a successive petition for habeas corpus in the 282nd District Court.

PRIOR CRIMINAL HISTORY

Under Texas law, the rules of evidence prevent certain prior criminal acts from being presented to a jury during the guilt-innocence phase of the trial. However, once a defendant is found guilty, jurors are presented information about the defendant’s prior criminal conduct during the second phase of the trial – which is when they determine the defendant’s punishment.

During the penalty phase of Harris’s trial, jurors learned that Harris had previously been convicted of three burglaries and evading arrest. He had also been charged with unauthorized use of a motor vehicle. A court revoked his probation for absconding from a residential treatment program, and he spent the next eight years in prison. In prison, Harris resided mostly in administrative segregation due to several violations and aggressive behavior. He attended the Program for the Aggressive Mentally Ill Offender, but the incidents continued. The program ultimately discharged him for non-compliance. Fifteen prison personnel testified regarding Harris’s behavioral problems during his incarceration, which included setting fire to his cell, threatening to kill prison personnel, assaulting prison personnel and other inmates, dealing drugs, refusing to follow orders, and engaging in sexual misconduct.

Texas Execution Information Center by David Carson.

Robert Wayne Harris, 40, was executed by lethal injection on 20 September 2012 in Huntsville, Texas for the murder and robbery of five people at his former place of employment.

On 15 March 2000, while working at a car wash in Irving, Harris masturbated in front of a female customer. The customer reported the incident, the police were called, and Harris, then 28, was arrested and fired from the job he held for about ten months.

On Sunday, 19 March, Harris borrowed a car from his friend, Junior Herrera. He then went to the home of his friend, Billy Brooks. Brooks contacted his stepson, Deon Bell, to lend Harris a pistol.

The next morning, before the car wash opened, Harris drove there in the borrowed car. He forced manager Dennis Lee, assistant manager Augustin Villasenor, and cashier Rhoda Wheeler into the office. He instructed Wheeler to open the safe. She complied and gave him the cash. Harris then forced all three victims to the floor and shot each of them in the back of the head at close range. He also slit Lee's throat.* Before Harris could leave, three other employees arrived for work. Harris forced them to kneel on the floor of the lobby and shot each of them in the back of the head at close range. Benjamin Villasenor, 32, and Roberto Jimenez, 15, died. The third victim survived but was left permanently disabled.

A seventh employee, Jason Shields, arrived. He saw the three victims in the lobby and saw Harris standing near the cash register. Harris told Shields he just discovered the crime scene. When Shields saw Harris pull a knife from a nearby bookshelf, he said he needed to step outside for some fresh air. He ran to a nearby doughnut shop and called 9-1-1. Harris followed Shields to the doughnut shop. He spoke to the 9-1-1 operator briefly and then fled the scene.

Harris returned the vehicle to Herrera and told him he discovered some bodies at the car wash. He took a taxi to Brooks's house. There, he separated the money from other objects he was carrying, and disposed of some metal lock boxes, a knife, a crowbar, and pieces of a cell phone in a wooded area. Harris then purchased some new clothing, checked into a motel, and sent Brooks to purchase a gold cross necklace for him. Harris was arrested at the home of another friend the next morning.

Prosecutors stated that Harris made about $4,000 in the robbery. They noted that as a former employee of the car wash, he knew that an armored car picked up cash receipts from the business every day but Sunday, and therefore that there would be cash in the safe on Monday morning. He also knew that the cash register would contain $200 to $300 for making change. The defense characterized the murders as an immediate reaction to provocation, after one of his former co-workers called him a "pervert".

After his arrest, Harris also confessed to the November 1999 murder of Sandra Scott, because he believed she had taken $200 from his wallet. Harris described how he abducted and killed her, and led police to her remains. He was charged with her capital murder, but was not tried.

Harris had three previous convictions for burglary of a building. He was sentenced to five years in prison on two counts in May 1991 and eight years on a third count in June 1991. He was paroled in May 1999 and discharged in June. Harris also had a history of assault and battery and drug dealing.

Testimony at Harris's punishment hearing also indicated that on the day he was arrested for the car wash murders, he was planning to drive to Florida to kill an old girlfriend. A jury convicted Harris of the murders of Augustin Villasenor and Rhoda Wheeler in September 2000 and sentenced him to death. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the conviction and sentenced in February 2003.

In his appeals, Harris's attorneys argued that he was mentally retarded and/or mentally disabled. He underwent a court-ordered psychological examination in 2010. All of his appeals in state and federal court were denied.

Harris declined to speak with reporters while on death row. He agreed to a television interview a few weeks before his execution, but instead of meeting with the reporter, he crawled under a shelf in the visiting area and had to be removed by officers. In his last statement, Harris expressed love and comfort to his brother and three friends who attended his execution. "I'm going home. I'm going home," he said. He did not look in the direction of the friends and relatives of his victims, who watched from another room. "Don't worry about me," he said. "I'll be alright. God bless, and the Texas Rangers, Texas Rangers." The lethal injection was then started. He was pronounced dead at 6:43 p.m.

"Texas executes man who confessed to killing 5," by Michael Graczk. (Associated Press September 20, 2012)

HUNSTVILLE, Texas (AP) — An ex-convict who confessed to killing five people at a Dallas-area car wash a week after he was fired from his job there 12 years ago was executed Thursday evening. Robert Wayne Harris, 40, received lethal injection less than two hours after the U.S. Supreme Court refused appeals to halt his punishment.

Harris expressed love to his brother and three friends who were watching through a window. "I'm going home. I'm going home," Harris said. "Don't worry about me. I'll be alright. God bless, and the Texas Rangers, Texas Rangers." He snored briefly as the lethal dose of pentobarbital began, then all breathing stopped. He was pronounced dead at 6:43 p.m., making him the eighth Texas inmate executed in the nation's most active capital punishment state. Another execution is set for next week.

Harris was convicted of two of the five slayings in March 2000 at the Mi-T-Fine Car Wash in Irving. He also was charged with abducting and killing a woman months before the killing spree and led police to her remains.

Harris didn't deny the slayings, but his lawyer unsuccessfully contended in appeals he was mentally impaired and should be spared because of a Supreme Court ban on execution of mentally impaired people. Attorney Lydia Brandt also argued prosecutors improperly removed black prospective jurors from serving on his trial jury. Harris is black. Harris died "without ever having had a fair trial" on the issues, Brandt said.

Harris' brother asked to leave the death chamber before the procedure was complete. A half-dozen friends and relatives of the victims also were present, watching in another room. Harris never looked at them. Two of them hugged after it was apparent Harris was dead. They declined to speak with reporters afterward. State attorneys opposed Harris' appeals, saying IQ tests disputed the mental impairment claims and that no racial component was involved in jury selection.

Harris had served an eight-year sentence for burglary and other offenses and had been working at the car wash for about 10 months when he was fired and arrested after exposing himself to a female customer. The following Monday, he showed up before the business opened, demanded the safe be opened and then shot the manager, the assistant who had fired Harris and a cashier. Three more employees reporting to work also were shot, two of them fatally. Harris was arrested the next day.

"I remember just the vicious nature of the offense and the fact it was very well thought-out and conceived by Robert Harris," Greg Davis, the former Dallas County assistant district attorney who was the lead trial prosecutor, said this week. "Guilt is just crystal clear." Brad Lollar, one of Harris' trial lawyers, acknowledged that, and said: "Our whole aim was to get him a life sentence."

Prosecutors tried Harris specifically for two of the slayings: Agustin Villasenor, 36, of Arlington, the assistant manager whose throat also was slit, and cashier Rhoda Wheeler, 46, of Irving. Harris was charged but not tried for killing Villasenor's brother, Benjamin, 32, a seven-year employee; car wash manager Dennis Lee, 48, of Irving; and Roberto Jimenez Jr., 15, an employee from Mexico. The day after Harris confessed to the car wash bloodbath, he led police to the remains of an Irving woman, Sandra Scott, 37, who had been missing for four months. He was charged but never tried for capital murder in her death.

Court records showed Harris was 18 when he went to prison for burglary and other charges and after violating probation. He spent most of it in administrative segregation, a confinement level for troublesome inmates. Testimony at his trial showed he set fire to his cell, assaulted and threatened to kill prison staff and inmates, dealt drugs and engaged in sexual misconduct. Harris' mention of the baseball team in his last words isn't the first time a sports team has been referred to from the death chamber gurney. Several have thanked the Dallas Cowboys football team for providing them enjoyment.

"Dallas-area killer of 5 set to die," by Michael Graczyk. (Associated Press September 19, 2012)

HUNTSVILLE — Arrested and then fired for exposing himself to a customer at a Dallas-area car wash where he’d worked for 10 months, Robert Wayne Harris borrowed a car and gun from acquaintances and returned a week later just before it was to open for the day. He was arrested the next day and charged with murder after five bodies were discovered at the Mi-T-Fine Car Wash in Irving. Harris, 40, was set for execution this evening for the carnage.

The car wash manager, his assistant and a cashier already were there that Monday morning 12 years ago when Harris showed up. Court records show Harris ordered that the safe containing the weekend receipts be opened and the three people get down on the floor. Each then was fatally shot and the assistant manager, who fired Harris the previous week, also had his throat slit. Three more employees reporting for work moments later were ordered to kneel and were shot in the back of the head. Two were killed and a third survived but with permanent injuries. When yet another worker arrived, Harris told him he had just stumbled upon the bloody scene, but the man became nervous when Harris pulled a knife. He told Harris he needed to step outside, then ran to find a phone and called 911. Harris never denied his involvement in the March 2000 massacre.

A Dallas County jury convicted Harris of capital murder after 11 minutes of deliberations, then decided he should be put to death. “There wasn’t much question about the guilt,” Brad Lollar, one of Harris’ trial lawyers, recalled. “Our whole aim was to get him a life sentence.”

Prosecutors tried him specifically for two of the slayings: Agustin Villasenor, 36, of Arlington, the assistant manager who had worked about 11 years at the car wash, and cashier Rhoda Wheeler, 46, of Irving. The other slaying victims were Villasenor’s brother, Benjamin, 32, a seven-year employee; Dennis Lee, 48, of Irving, the car wash manager; and Roberto Jimenez Jr., 15, also an employee and from Mexico. “I remember looking at the crime scene photos,” Greg Davis, the lead prosecutor in the case, said this week. “I remember the floors just covered with blood. I remember just the vicious nature of the offense and that fact is was conceived by Robert Harris.”

The day after Harris confessed to the car wash bloodbath, he led police to a ditch in the weedy and littered Trinity River floodplain and the remains of an Irving woman, Sandra Scott, 37, who had been missing for four months. He was charged but never tried for capital murder in her abduction and slaying. The Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles on Tuesday rejected a clemency request from Harris.

Appeals pending before the U.S. Supreme Court argued the jury that heard the case against Harris, who is black, was unfairly selected by prosecutors who used their jury challenges to exclude potential black jurors from the panel. “Prosecutors engaged in purposeful racial discrimination,” Harris’ appellate attorney, Lydia Brandt, told the court. Davis denied the claims. State attorneys told the Supreme Court the trial record includes nothing to indicate the race of jurors or those who were not selected.

Another appeal contended Harris was mentally impaired and he should not be put to death because of a Supreme Court prohibition against executing the mentally impaired. “Harris’ case had no ‘battle of the experts’ where defense experts opined he had retardation whereas states’ experts contended he did not,” Georgette Oden, an assistant Texas attorney general, told the justices. “Even Harris’ experts did not find him to be retarded.”

Harris has declined to speak with reporters from prison, with his execution date approaching. Lollar described him as a cooperative client but “the worst stutterer I have ever seen.” Lollar speculated the speech disorder was a result of Harris, at age 8, watching his father kill his mother and then was worsened by his mental impairment. “That would affect the mind of anybody,” he said.

Court records show when Harris was 18 he was convicted of three burglaries, evading arrest and was charged with unauthorized use of a motor vehicle. His probation was revoked after he fled a treatment program and he went to prison for eight years. He spent most of his time in administrative segregation, a confinement level for troublesome inmates.

Harris would be the eighth Texas prisoner given lethal injection this year. At least 10 other condemned inmates have execution dates scheduled in the coming months in the nation’s busiest capital punishment state, including one set for next week.

"Killer Robert Wayne Harris Executed; Harris received lethal injection less than two hours after the U.S. Supreme Court refused appeals to halt his punishment," by Michael Graczyk. (Friday, Sep 21, 2012)

An ex-convict who confessed to killing five people at a Dallas-area car wash a week after he was fired from his job there 12 years ago was executed Thursday evening. Robert Wayne Harris, 40, received lethal injection less than two hours after the U.S. Supreme Court refused appeals to halt his punishment.

Harris expressed love to his brother and three friends who were watching through a window. "I'm going home. I'm going home," Harris said. "Don't worry about me. I'll be alright. God bless, and the Texas Rangers, Texas Rangers." He snored briefly as the lethal dose of pentobarbital began, then all breathing stopped. He was pronounced dead at 6:43 p.m., making him the eighth Texas inmate executed in the nation's most active capital punishment state. Another execution is set for next week.

Harris was convicted of two of the five slayings in March 2000 at the Mi-T-Fine Car Wash in Irving. He also was charged with abducting and killing a woman months before the killing spree and led police to her remains.

Harris didn't deny the slayings, but his lawyer unsuccessfully contended in appeals he was mentally impaired and should be spared because of a Supreme Court ban on execution of mentally impaired people. Attorney Lydia Brandt also argued prosecutors improperly removed black prospective jurors from serving on his trial jury. Harris is black. Harris died "without ever having had a fair trial" on the issues, Brandt said. Harris' brother asked to leave the death chamber before the procedure was complete. A half-dozen friends and relatives of the victims also were present, watching in another room.

Harris never looked at them. Two of them hugged after it was apparent Harris was dead. They declined to speak with reporters afterward.

State attorneys opposed Harris' appeals, saying IQ tests disputed the mental impairment claims and that no racial component was involved in jury selection.

Harris had served an eight-year sentence for burglary and other offenses and had been working at the car wash for about 10 months when he was fired and arrested after exposing himself to a female customer. The following Monday, he showed up before the business opened, demanded the safe be opened and then shot the manager, the assistant who had fired Harris and a cashier. Three more employees reporting to work also were shot, two of them fatally. Harris was arrested the next day. "I remember just the vicious nature of the offense and the fact it was very well thought-out and conceived by Robert Harris," Greg Davis, the former Dallas County assistant district attorney who was the lead trial prosecutor, said this week. "Guilt is just crystal clear."

Brad Lollar, one of Harris' trial lawyers, acknowledged that, and said: "Our whole aim was to get him a life sentence." Prosecutors tried Harris specifically for two of the slayings: Agustin Villasenor, 36, of Arlington, the assistant manager whose throat also was slit, and cashier Rhoda Wheeler, 46, of Irving. Harris was charged but not tried for killing Villasenor's brother, Benjamin, 32, a seven-year employee; car wash manager Dennis Lee, 48, of Irving; and Roberto Jimenez Jr., 15, an employee from Mexico.

The day after Harris confessed to the car wash bloodbath, he led police to the remains of an Irving woman, Sandra Scott, 37, who had been missing for four months. He was charged but never tried for capital murder in her death. Court records showed Harris was 18 when he went to prison for burglary and other charges and after violating probation. He spent most of it in administrative segregation, a confinement level for troublesome inmates.

Testimony at his trial showed he set fire to his cell, assaulted and threatened to kill prison staff and inmates, dealt drugs and engaged in sexual misconduct. Harris' mention of the baseball team in his last words isn't the first time a sports team has been referred to from the death chamber gurney. Several have thanked the Dallas Cowboys football team for providing them enjoyment.

Robert Wayne Harris worked at Mi-T-Fine Car Wash for ten months. An armored car picked up cash receipts from the car wash every day except Sunday. Therefore, Harris knew that on Monday morning, the safe would contain cash receipts from the weekend and the cash register would contain $200-$300 for making change.

On Wednesday, March 15, 2000, Harris masturbated in front of a female customer. The customer reported the incident to a manager, and a cashier called the police. Harris was arrested and fired. On Sunday, March 19, Harris spent the day with his friend, Junior Herrera, who sold cars. Herrera was driving a demonstrator car from the lot. Although Harris owned his own vehicle, he borrowed Herrera's that evening. He then went to the home of friend Billy Brooks, who contacted his step-son, Deon Bell, to lend Harris a pistol.

On Monday, March 20, Harris returned to the car wash in the borrowed car at 7:15 a.m., before it opened for business. Harris forced the manager, Dennis Lee, assistant manager, Augustin Villasenor, and cashier, Rhoda Wheeler, into the office. He instructed Wheeler to open the safe, which contained the cash receipts from the weekend. Wheeler complied and gave him the cash. Harris then forced all three victims to the floor and shot each of them in the back of the head at close range. He also slit Lee's throat. Before Harris could leave, three other employees arrived for work unaware of the danger. Harris forced them to kneel on the floor of the lobby area and shot each of them in the back of the head from close range. One of the victims survived with permanent disabilities.

Shortly thereafter, a seventh employee, Jason Shields, arrived. Shields noticed the three bodies in the lobby and saw Harris standing near the cash register. After a brief exchange in which Harris claimed to have discovered the crime scene, pointed out the bodies of the other victims, and pulled a knife from a nearby bookshelf, Shields became nervous and told Harris he needed to step outside for fresh air. Shields hurried to a nearby doughnut shop to call authorities. Harris followed Shields to the doughnut shop, also spoke to the 911 operator, then fled the scene.

Harris returned the vehicle to Herrera and told him that he had discovered some bodies at the car wash. Harris then took a taxi to Brooks' house. At Brooks' house, he separated the money from the other objects and disposed of the metal lock boxes, a knife, a crowbar, and pieces of a cell phone in a wooded area. Harris purchased new clothing, checked into a motel, and sent Brooks to purchase a gold cross necklace for him. Later that afternoon, Harris drove to the home of another friend and remained there until the following morning, when he was arrested.

Testimony also showed that Harris had planned to drive to Florida on Tuesday and kill an old girlfriend. Harris directed police to the body of Sandra Estes Scott, who had been missing since November 29, 1999. Harris's long history of violence and aggression reveals an escalating pattern of disrespect for the law. Between the ages of eight and fourteen, Harris attended special education classes for emotionally-disturbed children, physically confronted teachers and students, and received a diagnosis of aggressive conduct disorder. At the age of fifteen, Harris assaulted a clerk in the local mall and stole several items from his aunt's house, including a gun. After his aunt reported the burglary to police, Harris struck her on the back of the head with a hammer so forcefully that the hammer broke. Harris spent two years in the Texas Youth Commission for this incident, where again he received a diagnosis of aggressive conduct disorder. At age seventeen, Harris began dealing crack cocaine. At the age of eighteen, Harris was convicted of three burglaries, evading arrest, and charged with unauthorized use of a motor vehicle. A court revoked his probation for absconding from a residential treatment program, and he spent the next eight years in prison.

In prison, Harris resided mostly in administrative segregation due to several violations and aggressive behavior. He attended the Program for the Aggressive Mentally Ill Offender, but the incidents continued. This program ultimately discharged him for non-compliance. Fifteen prison personnel testified regarding Harris's behavioral problems during his incarceration, which included setting fire to his cell, threatening to kill prison personnel, assaulting prison personnel and other inmates, dealing drugs, refusing to follow orders, and engaging in sexual misconduct. Harris was released from prison in May 1999. That month, he began work at Mi-T-Fine Car Wash.

Within six months, he murdered Sandra Scott because he believed she had taken $200 from his wallet. Harris's psychiatrist testified that patients like Harris were difficult to control, because punishment did not frighten them, and both Harris's psychiatrist and psychologist agreed upon a diagnosis of anti-social personality disorder marked by a persistent pattern of violating the rights of others or major social norms. The facts of the instant offense and Harris's criminal history overwhelmingly signal Harris's potential for future dangerousness. Harris has spent all but eight years of his life in disciplinary programs. And yet, his release from prison ten months before the instant offense did not trigger a period of rehabilitation and resolve to remain free but rather a killing spree that culminated in the murders of at least six people. He carefully planned the execution-style murders of his fellow employees by borrowing a car and weapon, then covered his involvement by destroying or hiding physical evidence linking himself to the crime. The evidence further suggests that Harris planned to continue the killing spree.

Harris v. State, Not Reported in S.W.3d, 2003 WL 1793023 (Tex.Cr.App. 2003) (Direct Appeal)

HOLCOMB, J., delivered the opinion of a unanimous Court.

In September 2000, a Dallas County jury convicted appellant of capital murder. Tex. Penal Code Ann. § 19.03(a). Pursuant to the jury's answers to the special issues set forth in Texas Code of Criminal Procedure Article 37.071, sections 2(b) and 2(e), the trial judge sentenced appellant to death. Art. 37.071 § 2(g).FN1 Direct appeal to this Court is automatic. Art. 37.071 § 2(h). Appellant raises seventeen points of error. We will affirm.

SUFFICIENCY OF THE EVIDENCE

In appellant's seventh point of error, he contests the legal sufficiency of the evidence to support the future dangerousness issue. See Art. 37.071 § 2(b). In evaluating the sufficiency of the evidence to support the jury's answer to the future dangerousness special issue, we view the evidence in the light most favorable to the verdict and determine whether any rational trier of fact could have found beyond a reasonable doubt that there is a probability that the appellant would commit criminal acts of violence constituting a continuing threat to society. Jackson v. Virginia, 443 U.S. 307, 319, 99 S.Ct. 2781, 61 L.Ed.2d 560 (1979); Allridge v. State, 850 S.W.2d 471, 487 (Tex.Crim.App.1991), cert. denied, 510 U.S. 831, 114 S.Ct. 101, 126 L.Ed.2d 68 (1993). We have enumerated a non-exclusive list of factors that the jury may consider in determining whether a defendant constitutes a continuing threat to society:

(1) the circumstances of the capital offense, including the defendant's state of mind and whether he was acting alone or with other parties; (2) the calculated nature of the defendant's acts; (3) the forethought and deliberateness exhibited by the crime's execution; (4) the existence of a prior criminal record and the severity of the prior crimes; (5) the defendant's age and personal circumstances at the time of the offense; (6) whether the defendant was acting under duress or the domination of another at the time of the commission of the offense; (7) psychiatric evidence; and (8) character evidence. Keeton v. State, 724 S.W.2d 58, 61 (Tex.Crim.App.1987); accord Reese v. State, 33 S.W.3d 238, 245 (Tex.Crim.App.2000). In an appropriate case, the circumstances of the offense alone may warrant an affirmative answer to the future dangerousness special issue. Sonnier v. State, 913 S.W.2d 511, 517 (Tex.Crim.App.1995).

Appellant characterizes this offense as an immediate reaction to provocation which did not involve “torture, necrophilia, disfigurement, mutilation, or other traditional circumstances that would justify a death sentence without additional evidence.” He claims that he “reacted” when one of the car wash employees called him a “pervert.” Appellant fails to cite any authority for the proposition that a defendant must commit capital murder in the course of torture, necrophilia, disfigurement, or mutilation to warrant the death penalty, and the record belies his contention that he murdered five people at the car wash only in response to provocation.

Appellant worked at Mi-T-Fine Car Wash for ten months prior to the offense. An armored car picked up cash receipts from the car wash every day except Sunday. Therefore, appellant knew that on Monday morning, the safe would contain cash receipts from the weekend and the cash register would contain $200-$300 for making change. On Wednesday, March 15, 2000, appellant masturbated in front of a female customer. The customer reported the incident to a manager, and a cashier called the police. Appellant was arrested and fired.

On Sunday, March 19, appellant spent the day with his friend, Junior Herrera, who sold cars. Herrera was driving a demonstrator car from the lot. Although appellant owned his own vehicle, he borrowed Herrera's that evening. He then went to the home of friend Billy Brooks, who contacted his step-son, Deon Bell, to lend appellant a pistol.

On Monday, March 20, appellant returned to the car wash in the borrowed car at 7:15 a.m., before it opened for business. Appellant forced the manager, Dennis Lee, assistant manager, Augustin Villasenor, and cashier, Rhoda Wheeler, into the office. He instructed Wheeler to open the safe, which contained the cash receipts from the weekend. Wheeler complied and gave him the cash. Appellant then forced all three victims to the floor and shot each of them in the back of the head at close range. He also slit Lee's throat.

Before appellant could leave, three other employees arrived for work unaware of the danger. Appellant forced them to kneel on the floor of the lobby area and shot each of them in the back of the head from close range. One of the victims survived with permanent disabilities. Shortly thereafter, a seventh employee, Jason Shields, arrived. Shields noticed the three bodies in the lobby and saw appellant standing near the cash register. After a brief exchange in which appellant claimed to have discovered the crime scene, pointed out the bodies of the other victims, and pulled a knife from a nearby bookshelf, Shields became nervous and told appellant he needed to step outside for fresh air. Shields hurried to a nearby doughnut shop to call authorities. Appellant followed Shields to the doughnut shop, also spoke to the 911 operator, then fled the scene.

Appellant returned the vehicle to Herrera and told him that he had discovered some bodies at the car wash. Appellant then took a taxi to Brooks' house. At Brooks' house, he separated the money from the other objects and disposed of the metal lock boxes, a knife, a crowbar, and pieces of a cell phone in a wooded area. Appellant purchased new clothing, checked into a motel, and sent Brooks to purchase a gold cross necklace for him. Later that afternoon, appellant drove to the home of another friend and remained there until the following morning, when he was arrested. Testimony also showed that appellant had planned to drive to Florida on Tuesday and kill an old girlfriend.

Appellant's long history of violence and aggression reveals an escalating pattern of disrespect for the law. Between the ages of eight and fourteen, appellant attended special education classes for emotionally-disturbed children, physically confronted teachers and students, and received a diagnosis of aggressive conduct disorder. At the age of fifteen, appellant assaulted a clerk in the local mall and stole several items from his aunt's house, including a gun. After his aunt reported the burglary to police, appellant struck her on the back of the head with a hammer so forcefully that the hammer broke. Appellant spent two years in the Texas Youth Commission for this incident, where again he received a diagnosis of aggressive conduct disorder. At age seventeen, appellant began dealing crack cocaine.

At the age of eighteen, appellant was convicted of three burglaries, evading arrest, and charged with unauthorized use of a motor vehicle. A court revoked his probation for absconding from a residential treatment program, and he spent the next eight years in prison.

In prison, appellant resided mostly in administrative segregation due to several violations and aggressive behavior. He attended the Program for the Aggressive Mentally Ill Offender, but the incidents continued. This program ultimately discharged him for non-compliance. Fifteen prison personnel testified regarding appellant's behavioral problems during his incarceration, which included setting fire to his cell, threatening to kill prison personnel, assaulting prison personnel and other inmates, dealing drugs, refusing to follow orders, and engaging in sexual misconduct. Appellant was released from prison in May 1999. That month, he began work at Mi-T-Fine Car Wash. Within six months, he murdered Sandra Scott because he believed she had taken $200 from his wallet. Appellant's psychiatrist testified that patients like appellant were difficult to control, because punishment did not frighten them, and both appellant's psychiatrist and psychologist agreed upon a diagnosis of anti-social personality disorder marked by a persistent pattern of violating the rights of others or major social norms.

The facts of the instant offense and appellant's criminal history overwhelmingly signal appellant's potential for future dangerousness. Appellant has spent all but eight years of his life in disciplinary programs. And yet, his release from prison ten months before the instant offense did not trigger a period of rehabilitation and resolve to remain free but rather a killing spree that culminated in the murders of at least six people. He carefully planned the execution-style murders of his fellow employees by borrowing a car and weapon, then covered his involvement by destroying or hiding physical evidence linking himself to the crime. The evidence further suggests that appellant planned to continue the killing spree. We overrule point of error seven.

ABSENCE OF DEFENDANT DURING TRIAL PROCEEDINGS

In his second point of error, appellant argues that the trial court erred in conducting voir dire in his absence, violating the Sixth Amendment, Fourteenth Amendment, and Article I, section 10 of the Texas Constitution. On September 18, 2001, defense counsel waived the defendant's presence for the day, then struck three venire members, agreed to excuse two venire members, and accepted juror Semyan. On this complained-of date, appellant was undergoing psychological testing by his expert witness, Dr. J. Douglas Crowder.

While a criminal defendant has a constitutional right to be “present at all stages of the trial where his absence might frustrate the fairness of the proceedings,” Faretta v. California, 422 U.S. 806, 819 n. 15, 95 S.Ct. 2525, 45 L.Ed.2d 562 (1975), he may waive that right. See Garcia v. State, 919 S.W.2d 370, 393-94 (Tex.Crim.App.1996) (op. on rehearing) (defendant may waive Confrontation Clause-based right under Article 33.03 to attend proceeding in which court qualified and instructed ten prospective jurors). The federal courts of appeals that have squarely addressed the issue of counsel's acquiescence in conducting portions of jury voir dire outside a defendant's presence have consistently held that counsel's acquiescence forfeits any objection to that process. See United States v. Rolle, 204 F.3d 133, 138 (4th Cir.2000); United States v. Gibbs, 182 F.3d 408, 437 (6th Cir.1999); United States v. Tipton, 90 F.3d 861, 874 (4th Cir.1996), cert. denied, 520 U.S. 1253 (1997); United States v. Dioguardi, 428 F.2d 1033, 1039 (2nd Cir.), cert. denied, 400 U .S. 825 (1970). Further, if the presence of the defendant does not bear “a reasonably substantial relationship to the opportunity to defend,” no harm is shown by his absence. Adanandus v. State, 866 S.W.2d 210, 219 (Tex.Crim.App.1993), cert. denied, 510 U.S. 1215, 114 S.Ct. 1338, 127 L.Ed.2d 686 (1994). Not only did appellant waive his right to be present at voir dire, he does not contend that he suffered any harm or injury to his opportunity to defend by the voir dire decisions made on September 18, other than arguing, “[w]ithout Appellant's input, it is impossible to determine if his presence to assist counsel might have developed different actions by the attorneys during voir dire proceedings.” We overrule point of error two.

In point of error three, appellant reiterates the constitutional arguments he made in point of error two and contends that the trial court erred in conducting part of a hearing to qualify his expert in appellant's absence. Again, defense counsel waived appellant's right to be present. When a defendant voluntarily absents himself after the jury has been selected, the trial may proceed to its conclusion. Art. 33.03. An appellate court will not disturb the trial court's findings without evidence from the defendant that his absence was not voluntary. Moore v. State, 670 S.W.2d 259, 261 (Tex.Crim.App.1984).

During the punishment phase of trial, the trial court began one morning's proceedings with a hearing outside of the jury's presence to determine the admissibility of Dr. Crowder's expert testimony for the defense. Defense counsel suggested that they begin the hearing without appellant, who was expected to arrive momentarily. The trial court agreed and asked the bailiffs to “bring [appellant] out as soon as he's ready.” The record does not reflect when appellant arrived. Because appellant requested the procedure employed, we overrule point of error three. See Prystash v. State, 3 S.W.3d 522, 531 (Tex.Crim.App.1999).

VENIRE ISSUES

In point of error four, appellant alleges that the trial court erred in reversing the order in which the parties either accepted or challenged the final two venire members. After venire member Reeder's voir dire, the trial court asked him to step into the hallway, then immediately proceeded to the voir dire of the final venire member, Harper-Hayden. Following Harper-Hayden's voir dire, defense counsel challenged her for cause, which the trial court denied, then exercised a peremptory strike against her. Defense counsel also asked for “an additional challenge to strike Juror 1608, Scott Andrew Reeder,” which the trial court denied. Counsel never objected to the trial court's re-ordering of the exercise of challenges and has therefore failed to preserve error for appeal. The procedure controlling the order and the timing of the exercise of peremptory challenges is not an absolute requirement and may be waived. Busby v. State, 990 S.W.2d 263, 268 (Tex.Crim.App.1999), cert. denied, 528 U.S. 1081, 120 S.Ct. 803, 145 L.Ed.2d 676 (2000). We overrule point of error four.

In points of error eight and nine, appellant argues that the trial court erred in denying his challenges for cause of venire members Wittenback and Dulworth. He alleges that both venire members expressed a bias against requiring the State to prove everything in the indictment beyond a reasonable doubt and considering mitigating evidence if they answered the future dangerousness issue affirmatively. To preserve error on denied challenges for cause, an appellant must demonstrate on the record that: 1) he asserted a clear and specific challenge for cause; 2) he used a peremptory challenge on the complained-of venire member; 3) his peremptory challenges were exhausted; 4) his request for additional strikes was denied; and 5) an objectionable juror sat on the jury. Green v. State, 934 S.W.2d 92, 105 (Tex.Crim.App.1996), cert. denied, 520 U.S. 1200, 117 S.Ct. 1561, 137 L.Ed.2d 707 (1997). The record in this case shows that appellant exhausted his peremptory challenges and requested an additional challenge, which the trial court denied. Appellant then objected to the seating of the twelfth juror, Scott Reeder, thereby preserving any error for review on appeal.

When the trial judge errs in overruling a challenge for cause against a venire member, the defendant is harmed if he uses a peremptory strike to remove the venireperson and thereafter suffers a detriment from the loss of the strike. Demouchette v. State, 731 S.W.2d 75, 83 (Tex.Crim.App.1986), cert. denied, 482 U.S. 920, 107 S.Ct. 3197, 96 L.Ed.2d 685 (1987). Because the record reflects that appellant received no additional peremptory challenges, appellant demonstrates harm by showing that the trial court erroneously denied one of the complained-of challenges for cause. Penry v. State, 903 S.W.2d 715, 732 (Tex.Crim.App.), cert. denied, 516 U.S. 977, 116 S.Ct. 480, 133 L.Ed.2d 408 (1995); Martinez v. State, 763 S.W.2d 413, 425 (Tex.Crim.App.1988), cert. denied, 512 U.S. 1246, 114 S.Ct. 2765, 129 L.Ed.2d 879 (1994).

When reviewing a trial court's decision to grant or deny a challenge for cause, we look at the entire record to determine if there is sufficient evidence to support the court's ruling. Patrick v. State, 906 S.W.2d 481, 488 (Tex.Crim.App.1995), cert. denied, 517 U.S. 1106, 116 S.Ct. 1323, 134 L.Ed.2d 475 (1996). We give great deference to the trial court's decision because the trial judge is present to observe the demeanor of the venire member and to listen to his tone of voice. Id. We accord particular deference when the potential juror's answers are vacillating, unclear, or contradictory. King v. State, 29 S.W.3d 556, 568 (Tex.Crim.App.2000). Appellant may properly challenge any prospective juror who has a bias or prejudice against any phase of the law upon which he is entitled to rely. Art. 35.16(c)(2). The test is whether the bias or prejudice would substantially impair the prospective juror's ability to carry out his oath and instructions in accordance with the law. See, e.g., Patrick, 906 S.W.2d at 489; Hughes v. State, 878 S.W.2d 142, 148 (Tex.Crim.App.1992). Before a prospective juror can be excused for cause on this basis, however, the law must be explained to him, and he must be asked whether he can follow that law regardless of his personal views. Jones v. State, 982 S.W.2d 386, 390 (Tex.Crim.App.1998), cert. denied, 528 U.S. 985, 120 S.Ct. 444, 145 L.Ed.2d 362 (1999).

In point of error eight, appellant quotes four passages from Wittenback's voir dire in which he argues that Wittenback (1) refused to require the State to prove each element of the offense, (2) favored the imposition of the death penalty in capital murder cases, (3) refused to presume a “no” answer to the future dangerousness issue, and (4) refused to consider mitigating evidence. Wittenback ultimately professed to be able to follow the law after each of the complained-of responses.

In support of his first contention, appellant highlights a series of hypotheticals in which defense counsel asked Wittenback whether he would acquit a defendant if the State failed to prove that (1) the crime occurred entirely within Dallas County, or (2) the two killings occurred within the same criminal transaction, or (3) the defendant killed his victims only in the manner alleged in the indictment. When the State posed these same hypotheticals, Wittenback indicated that he would follow the law and find the defendant not guilty. Under defense counsel's questioning, Wittenback indicated that he would ignore the deviations from the indictment and convict appellant. After the trial court again discussed the State's burden to prove everything alleged in the indictment beyond a reasonable doubt, Wittenback professed an ability to set aside his personal feelings and follow the law.

In support of his second contention, appellant focuses on Wittenback's response to his questionnaire that “if the evidence shows the Defendant guilty of capital murder, I have no problem with the death penalty.... Yes, if a killing was involved, it should go to the death penalty.” Although Wittenback clarified that he meant a cold-blooded killing, he further indicated that if the State could prove the defendant guilty of the crimes alleged in the indictment, he would favor the death penalty. Wittenback conceded, however, that the death penalty is not appropriate for every murder. Although he favored the death penalty, he did not have enough information to say how he would vote in this case. He would base his decision on the circumstances and severity of the case.

In support of his third contention, defense counsel extrapolated Wittenback's alleged inclination to impose the death penalty to mean, “you would not be able to presume that [the defendant] wouldn't be a future danger, if you found him guilty of capital murder; is that true?”, to which Wittenback responded, “Huh-uh.” Wittenback then contrarily indicated that he would require proof that a defendant would pose a future danger and that he had difficulty answering these questions “until actually I, you know, hear the evidence on what type of man he is.” He finally responded that he did not believe that every convicted murderer is going to be a danger to society.

In support of his final contention, appellant highlights an exchange suggesting that Wittenback believed a convicted defendant should get the death penalty if the State proved that he posed a future danger, culminating in the question and answer: “if the State proves he's guilty of capital murder and they prove he's going to be a future danger, there isn't going to be anything that's going to be able to-to make you come back to a life sentence; you want him to get the death penalty and you think that's the appropriate thing to do.” Wittenback responded, “Right.” The trial court immediately clarified Wittenback's position on the special issues, and Wittenback promised to be open-minded and answer the mitigation issue according to the evidence.

Although Wittenback vacillated in each of these four lines of questioning, the phrasing of the questions which engendered the complained-of answers was often confusing. Upon clarification of each of these issues, Wittenback indicated his ability to follow the law. Because we defer to the trial court when a juror vacillates in his voir dire responses, we overrule point of error eight.

In point of error nine, appellant quotes two passages from Dulworth's voir dire that he characterizes as Dulworth (1) failing to accord the presumption of innocence, (2) shifting the burden of proof to appellant for the first special issue, and (3) refusing to consider mitigating evidence. Again, the trial court ultimately rehabilitated any challengeable responses to defense counsel's questions.

In support of his first and second contentions, encapsulated in the first passage appellant quotes, appellant cites an exchange in which Dulworth suggests that the defense would have to prove that appellant would not pose a future danger once convicted:

Q[Defense counsel]: Okay. Some people say-tell us-and, you know, people fit-I hate to pigeon-hole people because, you know, people don't just fit into one of these categories, but I find that people tend to fit in about one of three categories and, you know, it's either-some people say, “Hey, you show me someone that's killed once and I'll show you someone that may not kill again, but they're going to be a threat to society in the future. They're likely to do something that's going to be a threat to someone out there.” Okay. And another group says, “Hey, just because someone kills someone doesn't mean they're going to do anything violent again in their life,” and in the middle there's kind of a third group and that says, “Hey, you know, I'll tell you one thing, if they prove that murder case to me beyond a reasonable doubt, then, Defense you better show me that they are not going to be a threat to society, because, otherwise I'm going to find that they are.” I mean, do you fit into any of these categories? A[Dulworth]: Probably the last one, maybe. Q: Okay, in other words, you'd look to us to bring you some evidence- A: Yes. Q: -to show they wouldn't- A: Uh-huh. Q: -if the State proved its case beyond a reasonable doubt- A: Yes. Q: -and the person was guilty; is that right? A: Yes.

Before this exchange, Dulworth repeatedly stated that she would not automatically find that a convicted capital murderer would pose a future danger, stating, “You just have to kind of keep an open mind, you know.... It's just not something I could-you could answer ‘Yes' to every time.” Following the exchange, Dulworth responded to the trial court's voir dire that she understood the law and would follow it.

In support of his third contention, appellant cites a lengthy, convoluted exchange in which Dulworth expressed confusion on two occasions but admitted she would favor the death penalty if the State proved capital murder and the defendant's future dangerousness beyond a reasonable doubt. Presumably, she was foreclosing consideration of the mitigation issue. Under the judge's questioning, she testified that she would consider mitigating evidence, saying, “Yes. I'm open-minded,” and, “They could get some help or maybe they could better their life.” The trial court asked Dulworth directly if she could spare someone's life who had been found guilty and posed a future danger, to which she responded that she could be open-minded to that possibility.

Although Dulworth also vacillated in each of the complained-of exchanges, the trial court clarified the confusion and determined that Dulworth understood and could comply with the law. Because Dulworth repeatedly testified that she could render an impartial verdict notwithstanding her opinions, the trial court was within its discretion to deny appellant's challenge. We overrule point of error nine.

ADMISSION OF WRITTEN CONFESSIONS

In points of error five and six, appellant alleges that the trial court erred in admitting into evidence appellant's written confession to the instant murders and to an extraneous murder because the State failed to prove that the police officer to whom appellant made his statement admonished him under Article 38.22. He also suggests that each interaction between appellant and the police required a new set of warnings and that oral warnings are preferable to written warnings. The trial court considered these claims at a suppression hearing. “At a suppression hearing, the trial court is the sole judge of the credibility of witnesses and the weight of their testimony.” Wyatt v. State, 23 S.W.3d 18, 23 (Tex.Crim.App.2000). Therefore, we will not disturb the trial court's findings if the record supports them. See Penry, 903 S.W.2d at 744. Instead, “[w]e only consider whether the trial court properly applied the law to the facts.” Id.

The record of the hearing revealed that the officer who arrested appellant on March 21, 2000, gave him warnings at the time of arrest. Detective Spivey repeated appellant's rights at 11:25 a.m. in the police department sally-port. Spivey immediately obtained a written statement from appellant denying responsibility for the crime. Appellant signed the statement and initialed the written warnings. Shortly thereafter, Spivey interrogated appellant regarding inconsistencies in the physical evidence and appellant's first written statement which prompted appellant to write a second, incriminating statement in longhand. The police typed the second statement, and appellant signed it, initialing the warnings at the top of statement. Spivey then presented appellant to a magistrate, who again warned appellant and ensured that appellant understood his rights. Spivey and appellant returned to the interview room, and Spivey questioned appellant about property missing from the crime scene. Appellant agreed to show officers where he had deposited a duffel bag containing tools and cash boxes, directing them to a wooded area, where police later retrieved the bag.

On March 22, Spivey again interviewed appellant to clarify some questions about the instant offense. He did not repeat the warnings. During this conversation, appellant volunteered that he had murdered Sandra Scott. Spivey called in Detective Johnson, who was investigating the Scott murder. Johnson did not read or recite any warnings to appellant. Appellant led the officers to a field where he had disposed of Scott's body. Appellant confessed in a statement he wrote in longhand, which the police typed and appellant signed. Again, he initialed the warnings at the top.

Over the course of two days, appellant received oral warnings three times and written warnings three times, all of which he acknowledged verbally or with his initials. In its findings of fact and conclusions of law, the trial court found that appellant knowingly, intelligently, and voluntarily waived his constitutional and statutory rights before giving his statements. Police took the statements in compliance with Article 38.22, without threat or coercion. Appellant has failed to cite any authority to suggest that the person receiving the confession must also administer the warnings or that each new interaction requires a new set of warnings. See Allridge v. State, 762 S.W.2d 146, 157-58 (Tex.Crim.App.1988) (finding no violation of Article 38.22 when different detective interrogated defendant about unrelated offense three days later without reading warnings, knowing that defendant had previously been warned), cert. denied, 489 U.S. 1040, 109 S.Ct. 1176, 103 L.Ed.2d 238 (1989). Nor does he cite authority for his claim that oral warnings are preferable to written warnings. See Cockrell v. State, 933 S.W.2d 73, 91 (Tex.Crim.App.1996) (holding that written warnings printed on each page of defendant's confession sufficient to comply with Article 38.22), cert. denied, 520 U.S. 1173, 117 S.Ct. 1442, 137 L.Ed.2d 548 (1997). We will defer to the trial court's findings of fact and conclusions of law and overrule points of error five and six.

AUTOPSY PHOTOGRAPHS

In points of error ten and eleven, appellant contests the admission of autopsy photographs at both phases of trial as inflammatory and overly prejudicial. See State's Exhibits Nos. 100, 101, 105-108, 110-112, 114-118, 120, 121, and 146. The sixteen photographs admitted during the guilt/innocence phase depicted the entry and exit wounds suffered by the five victims at the car wash, three of the victims' full bodies on the examination table, a close-up of a slash across one victim's neck, and a close-up of the damage caused to one victim's teeth. The photo introduced at punishment depicted the decomposed remains of Sandra Scott, the victim of an extraneous offense to which appellant confessed.

The admissibility of a photograph falls within the sound discretion of the trial court. Evidence Rule 403 favors the admission of relevant evidence and carries a presumption that relevant evidence will be more probative than prejudicial. Montgomery v. State, 810 S.W.2d 372, 376 (Tex.Crim.App.1990). A reviewing court will not disturb the trial court's decision on appeal unless it falls outside the zone of reasonable disagreement. Jones v. State, 944 S.W.2d 642, 651 (Tex.Crim.App.1996). In determining whether the danger of unfair prejudice substantially outweighs the probative value of photographs, the trial court may consider the number of exhibits offered, their gruesomeness, their detail, their size, whether they are in color or in black and white, whether they are close-up, and whether the body depicted is clothed or naked. Wyatt, 23 S.W.3d at 29. A court, however, should not limit its consideration to this list, considering other means of proof and the circumstances unique to each individual case. Id. Autopsy photographs are generally admissible unless they depict mutilation of the victim caused by the autopsy itself. Rojas v. State, 986 S.W.2d 241, 249 (Tex.Crim.App.1998). Changes rendered by the autopsy process are of minor significance if the disturbing nature of the photograph is primarily due to the injuries caused by the appellant. Santellan v. State, 939 S.W.2d 155, 173 (Tex.Crim.App.1997).

The contested pictures do not depict anything to preclude their admissibility. The photos introduced during the guilt/innocence phase depict the bodies on clean gurneys, without extraneous matter adhering to them. While most of the wound photos are close-up, the full body photos do not expose the victims' breasts or genitalia. Nor do the photos duplicate one another. The photo of Sandra Scott merely corroborates appellant's confession to her murder, specifically that her body decomposed outside for several months before its discovery. We overrule points of error ten and eleven.

OTHER CLAIMS REGARDING THE DEATH PENALTY

In point of error one, appellant contends that the trial court gave an erroneous instruction in the jury charge regarding parole. The trial court instructed the jury: Under the law applicable in this case, if the defendant is sentenced to imprisonment in the institutional division of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice for life, the defendant will become eligible for release on parole, but not until the actual time served by the defendant equals 40 years, without consideration of any good conduct time. It cannot accurately be predicted how the parole laws might be applied to this defendant if the defendant is sentenced to a term of imprisonment for life because the application of those law will depend on decisions made by prison and parole authorities, but eligibility for parole does not guarantee that parole will be granted. Therefore, during your deliberations, you are not to consider the possible action of the Board of Pardons and Paroles or the Governor, or how long the defendant would be required to serve on a sentence of life imprisonment, or how the parole laws would be applied to the defendant. Such matters come within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Board of Pardons and Paroles and are no concern of yours. (Emphasis added.)

Appellant argues that in the italicized portion of the instruction, the trial court wrongly instructed the jury to disregard appellant's mandatory forty-year parole ineligibility in determining his fate, subverting the first, statutorily-required portion of the instruction, see Article 37.071, section 2(e)(2)(B), and violating Simmons v. South Carolina, 512 U.S. 154, 114 S.Ct. 2187, 129 L.Ed.2d 133 (1994). Appellant had requested the statutorily-required portion of the charge. We rejected an almost identical claim in Johnson v. State, 68 S.W.3d 644, 655-56 (Tex.Crim.App.2002) (the addendum to the statutorily-required portion of the charge did not require the jury to ignore the forty-year parole eligibility requirement but simply prevented the jury from speculating when the parole board would release a life-sentenced defendant). We overrule point of error one.

In point of error twelve, appellant alleges that the trial court erred in refusing to submit definitions of the vague terms used in the special issues. We rejected this argument in Ladd v. State, 3 S.W.3d 547, 572-73 (Tex.Crim.App.1999), cert. denied, 529 U.S. 1070, 120 S.Ct. 1680, 146 L.Ed.2d 487 (2000). We overrule point of error twelve.

In point of error thirteen, appellant argues that the Texas death penalty scheme violates the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments by requiring at least ten “no” votes for the jury to return a negative answer to the special issues. We rejected this argument in Pondexter v. State, 942 S.W.2d 577, 586 (Tex.Crim.App.1996), cert. denied, 522 U.S. 825, 118 S.Ct. 85, 139 L.Ed.2d 42 (1997). We overrule point of error thirteen.

In points of error fourteen and fifteen, appellant argues that the Texas death penalty scheme violates the Fifth, Eighth, and Fourteenth amendments and Article I, sections 13 and 19 of the Texas Constitution because of the impossibility of simultaneously restricting the jury's discretion to impose the death penalty while also allowing the jury unlimited discretion to consider all evidence militating against the imposition of the death penalty. We rejected this argument in Hughes v. State, 24 S.W.3d 833, 844 (Tex.Crim.App.), cert. denied, 531 U.S. 980, 121 S.Ct. 430, 148 L.Ed.2d 438 (2000). We overrule points of error fourteen and fifteen.

In points of error sixteen and seventeen, appellant argues that the cumulative effect of the above-enumerated violations violates the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments and Article I, section 19 of the Texas Constitution. While a number of errors may be harmful in their cumulative effect, Chamberlain v. State, 998 S.W.2d 230, 238 (Tex.Crim.App.1999), cert. denied, 528 U.S. 1082, 120 S.Ct. 805, 145 L.Ed.2d 678 (2000), appellant has not shown cumulative error here. We overrule points of error sixteen and seventeen.

We affirm the judgment of the trial court.

Harris v. Thaler, 464 Fed.Appx. 301 (5th Cir. 2012) (Habeas)

Background: Following affirmance of his capital murder conviction and death sentence, 2003 WL 1793023, and unsuccessful attempt to obtain state habeas relief, Texas death row inmate sought federal habeas relief. The United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas denied the petition, and inmate sought a certificate of appealability (COA), arguing that he could not be executed because he was mentally retarded.

Holdings: The Court of Appeals held that: (1) the lack of a live hearing in the state habeas court did not negate the presumption of correctness accorded to factual decisions made by that court; (2) neither the state nor the federal court erred in considering expert testimony that did not adjust inmate's IQ scores using Standard Error of Measurement or the Flynn Effect; (3) the district court did not err in granting inmate's motion to cancel the evidentiary hearing; and (4) reasonable jurists could not debate the district court's conclusion that inmate failed to show that he was ineligible for a death sentence. Application denied.

PER CURIAM: Pursuant to 5th Cir. R. 47.5, the court has determined that this opinion should not be published and is not precedent except under the limited circumstances set forth in 5th Cir. R. 47.5.4.

Robert Wayne Harris was convicted of capital murder following a jury trial in Texas and sentenced to death. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (CCA) affirmed his conviction and sentence on direct appeal. Harris unsuccessfully sought both state and federal habeas relief. Harris now seeks a certificate of appealability (COA) pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2253 to challenge the district court's denial of habeas relief, arguing under Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304, 122 S.Ct. 2242, 153 L.Ed.2d 335 (2002), that he cannot be executed because he is mentally retarded. We hold that reasonable jurists could not debate the district court's conclusion that Harris has failed to show that he is ineligible for a death sentence under Atkins. Accordingly, we deny his request for a COA.

I.

The CCA summarized the facts of Harris's crime in its opinion on direct appeal:

[Harris] worked at Mi–T–Fine Car Wash for ten months prior to the offense. An armored car picked up cash receipts from the car wash every day except Sunday. Therefore, [Harris] knew that on Monday morning, the safe would contain cash receipts from the weekend and the cash register would contain $200–$300 for making change. On Wednesday, March 15, 2000, [Harris] masturbated in front of a female customer. The customer reported the incident to a manager, and a cashier called the police. [Harris] was arrested and fired.

On Sunday, March 19[th], [Harris] spent the day with his friend, Junior Herrera, who sold cars. Herrera was driving a demonstrator car from the lot. Although [Harris] owned his own vehicle, he borrowed Herrera's that evening. He then went to the home of friend Billy Brooks, who contacted his step-son, Deon Bell, to lend [Harris] a pistol.

On Monday, March 20[th], [Harris] returned to the car wash in the borrowed car at 7:15 a.m., before it opened for business. [Harris] forced the manager, Dennis Lee, assistant manager, Agustin Villaseñor, and cashier, Rhoda Wheeler, into the office. He instructed Wheeler to open the safe, which contained the cash receipts from the weekend. Wheeler complied and gave him the cash. [Harris] then forced all three victims to the floor and shot each of them in the back of the head at close range. He also slit Lee's throat. Before [Harris] could leave, three other employees arrived for work unaware of the danger. [Harris] forced them to kneel on the floor of the lobby area and shot each of them in the back of the head from close range. One of the victims survived with permanent disabilities. Shortly thereafter, a seventh employee, Jason Shields, arrived. Shields noticed the three bodies in the lobby and saw [Harris] standing near the cash register. After a brief exchange in which [Harris] claimed to have discovered the crime scene, pointed out the bodies of the other victims, and pulled a knife from a nearby bookshelf, Shields became nervous and told [Harris] he needed to step outside for fresh air. Shields hurried to a nearby doughnut shop to call authorities. [Harris] followed Shields to the doughnut shop, also spoke to the 911 operator, then fled the scene.

[Harris] returned the vehicle to Herrera and told him that he had discovered some bodies at the car wash. [Harris] then took a taxi to Brooks's house. At Brooks's house, he separated the money from the other objects and disposed of the metal lock boxes, a knife, a crowbar, and pieces of a cell phone in a wooded area. [Harris] purchased new clothing, checked into a motel, and sent Brooks to purchase a gold cross necklace for him. Later that afternoon, [Harris] drove to the home of another friend and remained there until the following morning, when he was arrested. Testimony also showed that [Harris] had planned to drive to Florida on Tuesday and kill an old girlfriend. Harris v. State, Slip. Op. at *2, 2003 WL 1793023. Harris was convicted of capital murder for killing Agustin Villaseñor and Rhoda Wheeler in the same criminal transaction and sentenced to death. The CCA affirmed. Harris v. State, 2003 WL 1793023 (Tex.Crim.App.2003)(unpublished). The Supreme Court denied certiorari review. Harris v. Texas, 540 U.S. 839, 124 S.Ct. 97, 157 L.Ed.2d 71 (2003).

Harris petitioned the state court for a writ of habeas corpus, raising an Atkins claim among others. After finding that there were no factual issues requiring a hearing, the trial court entered detailed findings of fact and conclusions of law recommending that habeas relief be denied based on its review of the trial and habeas record. The trial court found that the only time Harris's IQ was tested below 70 was at the age of twenty-eight while preparing his defense to the capital murder charge, and that prior to age eighteen, Harris's IQ was tested at 71 and 80. The trial court concluded that Harris failed to present proof that he met the “significantly subaverage intellectual function” and “onset during developmental phase” prongs of the test for mental retardation. Further it made detailed and extensive findings of fact regarding Harris's adaptive function based on the records, trial proceedings, and Harris' behavior regarding the offense. The trial court concluded that Harris was not mentally retarded. The CCA expressly adopted the trial court's findings and denied Harris's application for writ of habeas corpus. Ex parte Harris, No. 59,925–01 (Tex.Crim.App. Sept. 15, 2004). Harris did not petition the Supreme Court for review of that decision.

Harris filed a federal writ application. The district court approved funds for the appointment of an investigator and for a mental retardation expert. The Director's motion for discovery of Harris's medical and school records was also granted. In August 2008, the district court granted Harris's request for an evidentiary hearing on his mental retardation claim. After the hearing date was set, it was continued at Harris's request. When Harris again requested a continuance of the hearing, the district court ordered a hearing on the issue. Following the hearing, the magistrate judge ordered Harris to submit itemized statements and a status report from the psychologist and investigator. The evidentiary hearing was reset.

Five days before the evidentiary hearing was to take place, Harris moved to cancel his evidentiary hearing and supplement the record with documentary evidence. The request was granted but Harris failed to supplement the record with any evidence. He did file an affidavit of counsel that his expert had retired and was unavailable. Harris also filed his psychologist's affidavit confirming that he did not want to testify. Harris then moved for funding to hire a different expert and for an evidentiary hearing. The magistrate judge denied the request and instead ordered the appointment of an expert to conduct an independent evaluation for the court. Dr. Andrews was appointed and submitted his report to the court.

After reviewing the record, the district court found that Harris failed to show by clear and convincing evidence that he is mentally retarded and denied Harris's petition and COA. This appeal followed.

II.

Under AEDPA, a petitioner must obtain a COA before he can appeal the district court's denial of habeas relief. See 28 U.S.C. § 2253(c); see also Miller–El v. Cockrell, 537 U.S. 322, 335–36, 123 S.Ct. 1029, 154 L.Ed.2d 931 (2003) (“[U]ntil a COA has been issued federal courts of appeals lack jurisdiction to rule on the merits of appeals from habeas petitioners.”). As the Supreme Court has explained:

The COA determination under § 2253(c) requires an overview of the claims in the habeas petition and a general assessment of their merits. We look to the District Court's application of AEDPA to petitioner's constitutional claims and ask whether that resolution was debatable among jurists of reason. This threshold inquiry does not require full consideration of the factual or legal bases adduced in support of the claims. In fact, the statute forbids it. Miller–El, 537 U.S. at 336, 123 S.Ct. 1029.

COA will be granted only if the petitioner makes “a substantial showing of the denial of a constitutional right.” 28 U.S.C. § 2253(c)(2). “A petitioner satisfies this standard by demonstrating that jurists of reason could disagree with the district court's resolution of his constitutional claims or that jurists could conclude the issues presented are adequate to deserve encouragement to proceed further.” Miller–El, 537 U.S. at 327, 123 S.Ct. 1029 (citation omitted). “The question is the debatability of the underlying constitutional claim, not the resolution of that debate.” Id. at 342, 123 S.Ct. 1029. “Indeed, a claim can be debatable even though every jurist of reason might agree, after the COA has been granted and the case has received full consideration, that petitioner will not prevail.” Id. at 338, 123 S.Ct. 1029. Moreover, “[b]ecause the present case involves the death penalty, any doubts as to whether a COA should issue must be resolved in [petitioner's] favor.” Hernandez v. Johnson, 213 F.3d 243, 248 (5th Cir.2000) (citation omitted).