50th murderer executed in U.S. in 2000

648th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

23rd murderer executed in Texas in 2000

222nd murderer executed in Texas since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

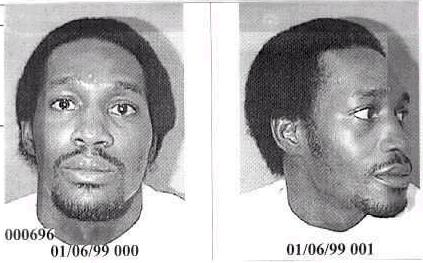

| Gary Lee Graham JUVENILE B / M / 17 - 36 |

Bobby Grant Lambert W / M / 53 |

11-09-81 | ||||||||

Summary:

During the period May 14 through May 20 of 1981, Gary Graham robbed some 13 different victims at nine different locations, in each instance leveling either a pistol or a sawed-off shotgun on the victim. Two of the victims were pistol-whipped, one being shot in the neck; a 64-year old male victim was struck with the vehicle Graham was stealing from him; and a 57-year old female victim was kidnapped and raped. A total of 19 eyewitnesses positively identified Graham as the perpetrator. Graham pled guilty to and was sentenced to 20-year concurrent prison sentences for 10 different aggravated robberies committed May 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, and 20, 1981. During the armed robbery of one victim, Richard B. Sanford, Gary Graham boasted of having killed six other people already.

On May 13, 1981, at 9:35pm, Bobby Grant Lambert was robbed and murdered in a Safeway parking lot in north Houston, Texas. Four out of the original five witnesses described the murderer as a young, thin black male, from medium height to tall. On May 27th, 17-year-old Gary Graham, a 5'9", 145 lb. black male, was positively identified as Mr. Lambert's murderer by Bernadine Skillern, the one eyewitness who clearly saw the killer's face. Five months later, Graham was convicted of the murder and sentenced to death. By the time he was executed 19 years later, Graham had secured the support and following of anti-death penalty activists who insisted that he was innocent and the death penalty was racist, including Danny Glover, Jesse Jackson, and Al Sharpton. Graham resisted and fought the guards who took him from death row and made a long, defiant final statement just before his execution.

Citations:

Graham v. Collins, 950 F.2d 1009 (5th Cir. 1992) (Habeas).

Graham v. Johnson, 94 F.3d 958 (5th Cir. 1996) (3rd Habeas).

Graham v. Johnson, 168 F.3d 762 (5th Cir. 1999) (4th Habeas).

Graham v. Texas Bd. of Pardons and Paroles, 913 S.W.2d 745 (Tex.App. 1996)

Internet Sources:

Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Executed Offenders (Gary Lee Graham)

Texas Department of Criminal Justice

Texas Attorney General News Release

June 14, 2000 - From Attorney General John Cornyn regarding the execution of Gary Graham:

"The people of Texas can be assured that Gary Graham is guilty of capital murder and that he has received the due process our American system guarantees. The incredible brutality and raw violence of Gary Graham forever will haunt the memories of Texans. The capital murder of Bobby Lambert started Gary Graham's rampage of crime in 1981. During the period May 14 through May 20 of that year, Gary Graham robbed some 13 different victims at nine different locations, in each instance leveling either a pistol or a sawed-off shotgun on the victim. Two of the victims were pistol-whipped, one being shot in the neck; a 64-year old male victim was struck with the vehicle Graham was stealing from him; and a 57-year old female victim was kidnapped and raped. "Not even Gary Graham can cast doubt on these crimes: he pleaded guilty to and was sentenced to 20-year concurrent prison sentences for 10 different aggravated robberies committed May 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, and 20, 1981. During the armed robbery of one victim, Richard B. Sanford, Gary Graham boasted of having killed six other people already.

"The only crime for which he claims to be falsely convicted is the murder of Bobby Lambert. In 1981, Gary Graham was convicted by a Harris County jury which concluded that "beyond a reasonable doubt" he was guilty of capital murder based on eyewitness testimony. Then in the sentencing phase of his trial, the jury heard evidence of Gary Graham's violent criminal history and sentenced him to death for the murder of Mr. Lambert.

"Gary Graham has repeatedly put forth the names of alleged new witnesses who either purport to provide an alibi for Graham or allege he was not the shooter. Evidence from all such witnesses that Gary Graham has produced since the trial, years afterward, has been considered by the courts and found to be not credible. "Both state and federal courts have been involved in hearing and reviewing his case. Gary Graham has had at least 20 appeals and his claims have been heard and rejected by at least 33 different judges.

"Each death penalty case in Texas receives the highest degree of scrutiny in our criminal justice system and the attention given Gary Graham's case in state and federal appellate courts, including the United States Supreme Court, demonstrates that his constitutional rights have been respected. This has been a long, extensive process with proper deliberation by the courts. "Gary Graham is not the innocent victim in this case, he is the convicted murderer. For 19 years, Graham's victims and their families have had to live with the consequences of his crimes. It is now time for them to have the closure and the justice our system provides."

On the night of May 13, 1981, Graham accosted Bobby Grant Lambert in the parking lot of a Houston, Texas, grocery store and attempted to grab his wallet. When Lambert resisted, Graham drew a pistol and shot him to death. Five months later, a jury rejected Graham's defense of mistaken identity and convicted him of capital murder. An eyewitness who identified Graham had followed him through the parking lot in her car for a short time after the murder. Lambert was killed during a crime spree the rest of which seventeen-year old Graham confessed to, including 10 other armed robberies, two shootings and a rape.

Texas Execution Information Center by David Carson

Gary Graham, 36, was executed by lethal injection on 22 June in Huntsville, Texas for the murder of a 53-year-old man outside a supermarket. On 13 May 1981, Bobby Lambert was coming out of a supermarket when an assailant reached into his pockets and shot him with a pistol as they scuffled. The robber got away with the change from a $100 bill.

Gary Graham, then 17, was arrested a week later (20 May) for the rape and robbery of a taxi driver. Lisa Blackburn said that Graham abducted her at a gas station, took her to a vacant place and repeatedly raped her. Then, they went to her house, where he took her valuables, shot up the walls, got undressed, and fell asleep. Blackburn then took Graham's gun and called police, who arrested him at the scene. Blackburn said that during the 5-hour ordeal, Graham kept saying to her "I've killed three people, and I'm going to kill you." Police linked 22 crimes that occurred from 13 to 20 May to Graham. On 16 May, Gary Spiers was robbed and shot in the thigh with a sawed-off shotgun. From a hospital bed, he identified Graham as the shooter to police. Spiers said that Graham saw he was having car trouble and offered to give him a lift, and attempted to rob him after he got in Graham's car. Graham was also identified by Greg Jones as the man who shot him in the throat and left him for dead. In all, Graham was suspected in 19 aggravated robberies -- including the shootings of Spiers and Jones and the rape of Blackburn -- two auto thefts, and Lambert's murder. He pleaded guilty to ten of the robberies.

On the night of Bobby Lambert's murder, Bernadine Skillern was sitting in her car in the parking lot. She said that when a man put a pistol to Lambert's head, she blew her horn, and the gunman turned to look at her. There was a pop, Lambert dropped his bag of groceries, and the other man fled. She followed him in her car until her screaming children made her stop. Skillern said that she got a good look at the killer for about a minute and a half. After Graham was arrested, Skillern picked his mug shot and chose him from a police lineup. She identified him at trial and has continued to do so ever since.

Graham has admitted responsibility for the other crimes, but says he did not kill Bobby Lambert and that Skillern's identification of him is mistaken. Two other eyewitnesses, though they could not identify the killer because neither saw his face, nevertheless said it could not have been Graham, because he is 5'10", while the assailant they saw was between 5'3" and 5'6". Graham also faults his attorney, who did not call the other two eyewitnesses to testify and did not cross-examine Skillern.

Most capital murder cases are decided without any eyewitnesses. A number of criminal defense attorneys have stated that they prefer when there is an eyewitness because it gives them a chance to create reasonable doubt. Harris County defense attorney Robert Morrow said, "I see there's an eyewitness and I see an opportunity." Another local defense lawyer, Floyd Freed, said, "it certainly gives me more hope at trial" if the prosecutors present an eyewitness. Death penalty cases are usually decided on confessions, physical evidence, and/or circumstantial evidence. In Graham's case, there was no confession or physical evidence, and circumstantial evidence was weak, so the prosecutors had to base most of their case on Bernadine Skillern's testimony.

At his trial, Graham gave no alibi for his whereabouts on the night Bobby Lambert was killed. His lawyer said Graham told him only that he had spent the evening with a girlfriend whose name, description, and address he could not remember. On appeal, four witnesses came forward to offer alibis for Graham, but when two of them -- one was his wife -- were called to testify before a state district judge, they contradicted themselves and each other and were deemed not credible.

Graham's case attracted national attention from the media, anti-death-penalty groups, and even Hollywood. As the date drew nearer, each side offered new evidence to support their positions. Graham's attorneys presented signed affidavits from three jurors who said they had a change of heart because they did not know about the other two eyewitnesses when they sentenced him to death. Harris County prosecutors filed an affidavit signed by the bailiff who escorted Graham from the courtroom after his death sentence, who heard him say, "Next time, I'm not going to leave any witnesses." A prosecutor filed an affidavit stating that the bailiff related the comment to him within minutes of the time it was allegedly made. Harris County District Attorney Johnny Holmes noted that Graham's case was reviewed 35 times by the courts and that his conviction was never overturned. The Supreme Court rejected Graham's appeal in May.

Graham, who called himself Shaka Sankova since 1995, was in the top 25 in Texas death row seniority and had seven prior execution dates. In January 1999, he called for violence and asked his supporters to go to Huntsville armed with AK-47 rifles to stop his execution. New Black Muslim Movement leader Quanell X urged young blacks to take out their anger against whites in wealthy neighborhoods if this execution was carried out. And recently, Graham reiterated his intention to "stop this thing by any means necessary."

Many Huntsville businesses closed early Thursday because of safety concerns. The Walker County courthouse closed at noon and city officials advised business owners to clear the area. Prison workers who live in about 30 houses near the Walls Unit, where all Texas executions are performed, were told to leave and staffers in the administrative offices were given the day off. Police set up barricades Wednesday night and set up two protest areas on opposite sides of the Walls Unit, one side for Graham's supporters and the other side for the Ku Klux Klan. At noon on Thursday, the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles denied Graham a 120-day reprieve by a 14-3 vote. The board also voted against commuting his punishment (12-5) and against a pardon (17-0). Later in the afternoon, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals and the U.S. Supreme Court, both of which had turned down Graham's appeals in the past, did so again. The Supreme Court's vote fell 5 to 4. Graham's lawyers' final move was to file a civil suit against the Texas parole board. A federal judge rejected that suit and Graham's attorneys did not appeal that ruling. The execution, scheduled for 6:00 p.m., was delayed for over two hours because of the last-minute appeals and lawsuit.

Though under Texas law the governor has the power to grant one 30-day stay of execution per prisoner, that option was not available to Governor George W. Bush because his predecessor, Ann Richards, used it on Graham in 1993. Even if that option was available to him, however, it is a given that Bush, who said he supported the execution, would not have used it. Outside the Walls Unit, a small fight broke out when some of Graham's supporters snuck into the Klan demonstration area, but a riot team from the Texas Department of Public Safety quickly moved in to stop it. After the Supreme Court's decision was announced, Graham supporters broke through police lines and six were arrested.

Graham resisted and fought the guards who took him from death row in Livingston to the Walls Unit in Huntsville Wednesday evening. He refused meals that night and on Thursday. Extra restraints were used to strap him to the gurney, where he made a long, defiant final statement in which he said he was being lynched and that the death penalty was a "holocaust for black people in America." Gary Graham, a.k.a. Shaka Sankova, was pronounced dead at 8:59 p.m.

Gary Lee Graham Last Statement

I would like to say that I did not kill Bobby Lambert. That I'm an innocent black man that is being murdered. This is a lynching that is happening in America tonight. There's overwhelming and compelling evidence of my defense that has never been heard in any court of America. What is happening here is an outrage for any civilized country to anybody anywhere to look at what's happening here is wrong.

I thank all of the people that have rallied to my cause. They've been standing in support of me. Who have finished with me. I say to Mr. Lambert's family, I did not kill Bobby Lambert. You are pursuing the execution of an innocent man.

I want to express my sincere thanks to all of ya'll. We must continue to move forward and do everything we can to outlaw legal lynching in America. We must continue to stay strong all around the world, and people must come together to stop the systematic killing of poor and innocent black people. We must continue to stand together in unity and to demand a moratorium on all executions. We must not let this murder/lynching be forgotten tonight, my brothers. We must take it to the nation. We must keep our faith. We must go forward. We recognize that many leaders have died. Malcom X, Martin Luther King, and others who stood up for what was right. They stood up for what was just. We must, you must brothers, that's why I have called you today. You must carry on that condition. What is here is just a lynching that is taking place. But they're going to keep on lynching us for the next 100 years, if you do not carry on that tradition, and that period of resistance. We will prevail. We may loose this battle, but we will win the war. This death, this lynching will be avenged. It will be avenged, it must be avenged. The people must avenge this murder. So my brothers, all of ya'll stay strong, continue to move forward.

Know that I love all of you. I love the people, I love all of you for your blessing, strength, for your courage, for your dignity, the way you have come here tonight, and the way you have protested and kept this nation together. Keep moving forward, my brothers. Slavery couldn't stop us. The lynching couldn't stop us in the south. This lynching will not stop us tonight. We will go forward. Our destiny in this country is freedom and liberation. We will gain our freedom and liberation by any means necessary. By any means necessary, we keep marching forward.

I love you, Mr. Jackson. Bianca, make sure that the state does not get my body. Make sure that we get my name as Shaka Sankofa. My name is not Gary Graham. Make sure that it is properly presented on my grave. Shaka Sankofa. I died fighting for what I believe in. I died fighting for what was just and what was right. I did not kill Bobby Lambert, and the truth is going to come out. It will be brought out. I want you to take this thing off into international court, Mr. Robert Mohammed and all ya'll. I want you, I want to get my family and take this down to international court and file a law suit. Get all the video tapes of all the beatings. They have beat me up in the back. They have beat me up at the unit over there. Get all the video tapes supporting that law suit. And make the public exposed to the genocide and this brutality world, and let the world see what is really happening here behind closed doors. Let the world see the barbarity and injustice of what is really happening here. You must get those video tapes. You must make it exposed, this injustice, to the world. You must continue to demand a moratorium on all executions. We must move forward Minister Robert Mohammed.

Ashanti Chimurenga, I love you for standing with me, my sister. You are a strong warrior queen. You will continue to be string in everything that you do. Believe in yourself, you must hold your head up, in the spirit of Winnie Mandela, in the spirit of Nelson Mandela. Ya'll must move forward. We will stop this lynching. Reverend Al Sharpton, I love you, my brother.

Bianca Jagger, I love all of you. Ya'll make sure that we continue to stand together. Reverend Jesse Jackson and know that this murder, this lynching will not be forgotten. I love you, too, my brother. This is genocide in America. This is what happens to black men when they stand up and protest for what is right and just. We refuse to compromise, we refuse to surrender the dignity for what we know is right. But we will move on, we have been strong in the past. We will continue to be strong as a people. You can kill a revolutionary, but you cannot stop the revolution. The revolution will go on. The people will carry the revolution on. You are the people that must carry that revolutionary on, in order to liberate our children from this genocide and for what is happening here in America tonight. What has happened for the last 100 or so years in America. This is the part of the genocide, this is part of the African (unintelligible), that we as black people have endured in America. But we shall overcome, we will continue with this. We will continue, we will gain our freedom and liberation, by any means necessary. Stay strong. They cannot kill us. We will move forward.

To my sons, to my daughters, all of you. I love all of you. You have been wonderful. Keep your heads up. Keep moving forward. Keep united. Maintain the love and unity in the community. And know that victory is assured. Victory for the people will be assured. We will gain our freedom and liberation in this country. We will gain it and we will do it by any means necessary. We will keep marching. March on black people. Keep your heads high. March on. All ya'll leaders. March on. Take your message to the people. Preach the moratorium for all executions. We're gonna stop, we are going to end the death penalty in this country. We are going to end it all across this world. Push forward people. And know that what ya'll are doing is right. What ya'll are doing is just. This is nothing more that pure and simple murder. This is what is happening tonight in America. Nothing more than state sanctioned murders, state sanctioned lynching, right here in America, and right here tonight. This is what is happening my brothers. Nothing less. They know I'm innocent. They've got the facts to prove it. They know I'm innocent. But they cannot acknowledge my innocence, because to do so would be to publicly admit their guilt. This is something these racist people will never do. We must remember brothers, this is what we're faced with. You must take this endeavor forward. You must stay strong. You must continue to hold your heads up, and to be there. And I love you, too, my brother. All of you who are standing with me in solidarity. We will prevail. We will keep marching. Keep marching black people, black power. Keep marching black people, black power. Keep marching black people. Keep marching black people. They are killing me tonight. They are murdering me tonight.

Shaka Sankora / Gary Graham Justice Coalition

"Contentious Texas Case Ends with Execution of Gary Graham," by Michael Graczyk. (AP)

HUNTSVILLE, Texas (AP) — Gary Graham, subject of the most contentious Texas death penalty case since Gov. George W. Bush began running for president, was executed Thursday night for a 1981 murder he said he did not commit. Graham, 36, received a lethal injection for the killing of a man in a holdup outside a Houston supermarket. The state parole board and appeals courts rejected his arguments that he was convicted on shaky evidence from a single eyewitness and that his trial lawyer did a poor job. Graham, who had vowed to “fight like hell” on the trip to the death chamber, put up a struggle. He was strapped to the gurney around his wrists and across his head — more restraints than are normally used in Texas executions.

He made a long, defiant final statement in which he reasserted his innocence, said he was being lynched and called the death penalty a holocaust for black Americans. He asked to be called Shaka Sankofa to reflect his African heritage.

“I die fighting for what I believed in,” Graham said. “The truth will come out.”

Bush said he supported the execution and pointed out that Graham's case had been reviewed by 33 state and federal judges.

“After considering all of the facts I am convinced justice is being done,” Bush said after final appeals were denied. “May God bless the victim, the family of the victim, and may God bless Mr. Graham.”

Graham's supporting witnesses included the Rev. Jesse Jackson, the Rev. Al Sharpton and Biana Jagger, representing Amnesty International. Witnesses said Jackson and Graham prayed and Graham looked at Jackson just before he died.

Also present were some of the victims of Graham's other crimes, and Bobby Hanners, the grandson of Bobby Lambert, the man he was convicted of killing.

“My heart goes out to the Graham family as they begin the grieving process. I also pray Gary Graham made peace with God. But I truly believe justice has been served,” Hanners said. Outside the Huntsville prison, hundreds of Graham supporters gathered in stifling heat and humidity near the brick building where 222 executions have now been carried out since capital punishment resumed in Texas in 1982. The total is by far the highest in the nation. When the Texas parole board, made up of 18 Bush appointees, refused to block the execution, that left the Republican governor with no options. The single 30-day reprieve a Texas governor may unilaterally give a condemned inmate was issued to Graham by Bush's predecessor in 1993. The parole board, which has spared a prisoner only once during Bush's tenure, could have granted a 120-day reprieve, a commutation to a lesser sentence, or a conditional pardon.

“I can say, unequivocally, that the board's decision not to recommend clemency was reached after a complete and unbiased review of the petition and evidence submitted,” board chairman Gerald Garrett said, hours before the execution.

The Supreme Court, a federal judge and state appeals court also turned down Graham's last-minute appeals, which delayed the execution for more than two hours.

The nation's high court turned down Graham's appeal on a 5-4 vote along its conservative-liberal ideological fault line. Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist and Justices Sandra Day O'Connor, Antonin Scalia, Anthony M. Kennedy and Clarence Thomas voted to reject the appeal. Justices John Paul Stevens, David H. Souter, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen G. Breyer voted to order the execution postponed, presumably to give the court more time to consider his appeal. Graham was convicted of killing 53-year-old Bobby Lambert in a holdup outside a Houston supermarket one night in 1981. He pleaded guilty to 10 robberies around the same time but said he was innocent of the murder.

No physical evidence tied Graham to the killing, and ballistics tests showed that the gun he had when he was arrested was not the murder weapon. But the witness who identified him, Bernadine Skillern, has never wavered.

Skillern, who was waiting in her car outside the supermarket while her daughter ran inside, saw the holdup from about 30 feet away. She said the lighting in the parking lot was adequate for her to see Graham.

“I don't feel joy and I don't feel sadness,” she said after the execution. “I only feel relief. I hope to get back to my privacy, put this incident behind me and now move on.”

Graham also argued that his lawyer during the trial, Ron Mock, should have introduced other witnesses who would say he was not the killer. But those witnesses initially told police they couldn't identify the killer, and prosecutors said they were not actual eyewitnesses. During Bush's 51/2 years in office, 133 men and two women have been executed. He said he would treat Graham's case no differently than any other he has considered. Two years ago, Bush told the parole board to review the case of serial killer Henry Lee Lucas because of questions about Lucas' conviction. His death sentence eventually was commuted to life. This month, Bush granted a condemned man a 30-day reprieve so he could pursue DNA tests. The debate over Graham's case came amid growing questions about the death penalty. Illinois Gov. George Ryan has placed a moratorium on executions, and Bush and Vice President Al Gore have been forced to address the issue as they campaign for president. Graham's case brought the loudest protests since pickax killer Karla Faye Tucker was executed in 1998, the first woman put to death in Texas since the Civil War era. “I recognize there are good people who oppose the death penalty,” Bush said. “I've heard their message and I respect their heartfelt point of view.”

The execution was witnessed by supporters that included the Rev. Jesse Jackson, the Rev. Al Sharpton and Amnesty International representative Bianca Jagger. Leading up to the execution, Graham refused meals but met for about an hour with Jackson, who said he and the inmate talked and prayed. “He was amazingly upbeat,” Jackson said. “There were no tears shed. He had a sense of inner peace. He feels he was being used as a kind of change agent to expose the system. With every passing hour ... there is mass education around the world about what is happening in Texas.” Outside the prison, eight people were arrested for breaking through police lines and a juvenile was arrested for throwing a plastic bottle at a prison administrator, who was not hurt. Other activists burned American flags. Another 150 people protested outside the governor's mansion in Austin. Protests were also held as far away as San Francisco and Northampton, Mass. In both cities, death penalty opponents were arrested for blocking traffic.

Abilene Reporter-News Online

"Civil Rights Group Wants Justice Department Review of Gary Graham Case" (August 26, 2000)

Abilene Reporter-News Online

"Executed Killer Graham Praised at Packed Memorial Service" (June 29, 2000)

Abilene Reporter-News Online

EDITORIAL - "Graham’s Execution Justified" (June 26, 2000)

Abilene Reporter-News Online

"Prosecution Plans to Ask For Execution Date for Gary Graham" (November 19, 1998)

"Gary Graham Says Texas Will Execute an Innocent Man Based on "Flimsy Evidence" (June 12, 2000)

(CNN) - In an online interview, Texas death row inmate Gary Graham tells CNN Legal Analyst Greta Van Susteren that he is innocent of the 1981 murder of Bobby Grant Lambert outside a Houston Safeway. He says his court-appointed trial lawyer failed to present a "mountain of evidence" during his two-day trial.

Graham, who is also known as Shaka Sankofa, admits to 10 aggravated robberies during the week of the murder, including shooting and seriously wounding at least one victim. But he says he is scheduled to be executed June 22 for a murder he did not commit.

Graham's life is now in the hands of Gov. George W. Bush and the Texas pardons board. According to a Bush spokesperson, Bush can accept or refuse a recommendation from the board to commute Graham's sentence or delay his execution, but if the board votes to carry out the execution, the governor "has no options" to stop it.

SAVE GARY GRAHAM! Texas Governor Bush To Execute An Innocent, Juvenile Offender."The odds and the danger that we face in our struggle for justice is great but even greater is the power of the people." -Gary Graham

Gary Graham is Innocent! Bobby Lambert was tragically murdered in a Safeway grocery store parking lot on May 13, 1981. Gary was miles away from the grocery store with at least four people when the crime occurred. Those four witnesses have all taken polygraph tests and passed, stating Gary was with them the night of the murder. He Was Convicted By A Mistaken Identification!

Eight crime scene witnesses have been identified who saw the assailant the night of Bobby Lambert's murder. Only one of them, Bernadine Skillern, later identified Mr. Graham as the assailant. None of the others identified Mr. Graham. Out of the eight eyewitnesses, Ms. Skillern had one of the poorest views of the assailant. She testified that she had a frontal view of the assailant's face for only two or three seconds, at night, from a distance of 30 to 40 feet.

Problems With The Identification: Nearly two weeks after the crime, Bernadine Skillern could not pick Gary's picture out of a photo line-up. She told the officer that "the photo of Gary Graham looked like the suspect [she] saw on the night of the offense except the complexion of the suspect [she] saw was darker and his face thinner." She said she could not say that the man in the photo was the suspect. The day after she saw Mr. Graham in a photo array, Ms. Skillern saw Mr. Graham again in a live lineup. He was the only person who had been in both a photo array and the lineup, and not surprisingly, she picked out Mr. Graham. She candidly admitted to the police that she had seen him in the photo array the night before. There Is No Physical Evidence Linking Graham To The Crime!

Weapon: Mr. Graham was arrested with a .22 caliber pistol a week after the murder. The victim of the murder, was killed with a .22 caliber pistol. The police firearms examiner determined that Mr. Graham's weapon could not have fired the fatal bullet. No Other Evidence: There are no fingerprints, ballistics or informant information linking Mr. Graham to the murder. Only the word of a single eyewitness that saw the assailant's face for two or three seconds at night from a distance.

Other Eyewitnesses Say It Was Not Gary Graham That Killed Bobby Lambert! One of the eyewitnesses was standing in the supermarket checkout line next to the killer. She undoubtedly had the best look at the person. She emphatically says that Gary Graham is the wrong man. At trial she was never asked if Gary Graham was the suspect. Eyewitness Ronald Hubbard saw the same live lineup with Bernadine Skillern and did not see the person he recalled as the assailant in the lineup. Of the six living crime scene witnesses other than Ms. Skillern, all describe the assailant as shorter than Bobby Lambert, who was 5'6". Mr. Graham was 5'9".

Mr. Graham's Trial Lawyers Thought He Was Guilty And Conducted No Pre-Trial Investigation! Graham had a court appointed lawyer, who failed to investigate his case. This lawyer has since admitted that he believed Graham was guilty and therefore did nothing to find proof otherwise. None of the other witnesses were called on to testify, and no investigation was done into the lack of physical evidence. Bush has already indicated that he would not grant clemency to Gary Graham.

Graham Has Been Close To Execution Five Times And Time Is Running Very Short! His execution has been stayed each time. Despite this, Graham still has not had a new trial in which the substantial evidence of his innocence could be introduced. The denial of a new trial at the state and federal level has been based on a Texas rule which bars court review on any evidence of innocence brought forward more than 30 days after the trial conviction. Graham's current lawyers started looking at his case 12 years after his conviction. His appeals have also been hampered by the 1996 Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, which greatly restricts federal appeals by death row inmates.

Graham's appeals are exhausted. His lawyers have filed a writ of certiorari with the U.S. Supreme Court. This writ is currently pending. If this is denied, only Governor George W. Bush and the Board of Pardons and Paroles, which he appoints, stand between Graham and state murder. A large and vocal movement is the only thing that can make a difference. We need people to get involved in activism around this case, and to do everything possible to let the state of Texas know that they can't execute an innocent man.

ProDeathPenalty.com / Justice For All

HOLLYWOOD, MURDER AND TEXAS - DEATH ROW INMATE GARY GRAHAM AND THE ANTI-DEATH PENALTY MOVEMENT: A CASE STUDY OF LIES, HALF-TRUTHS AND INTIMIDATION

"I've killed six people already; if you want to be number seven, do something stupid." ~ Gary Graham

HOW THE GARY GRAHAM CASE BECAME A WORLDWIDE CAUSE CELEBRE'

1) JUSTICE FOR ALL believes this has been the most extensive and expensive campaign ever conducted by anti-death penalty forces for any one case. Amnesty International has sponsored rallies for Graham in many cities around the world. It is our understanding that Amnesty International (USA) solicited extra funds, from their membership, for their operating budget, because of a deficit created by their work on the Graham case. We have not been able to confirm this.

2) Religious, academic and political leaders from around the world have come to Graham's aid.

3) Many media sources have eagerly fallen for this fraudulent campaign (e.g. The New Yorker, New York Times, Washington Post, Nightline, LEAR's, Village Voice, etc.), some in spite of knowledge to the contrary.

4) Presented by Texas Sen. Royce West, Danny Glover stated his belief in Graham's innocence in an appeal to a session of the 1993 Texas Legislature. For his tireless efforts against the death penalty, in general, and on behalf of Graham, in particular, Glover was awarded "Man of the Year" by the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty. Additional Hollywood stars have made public appeals on Graham's behalf: Ed Asner on "Good Morning America", Mike Farrell on "The Maury Povich Show", etc. Had they been lied to or did they just not care about the truth?

5) Graham advocate Susan Dillow has made appeals on Graham's behalf throughout the world, including a presentation to the British Parliament. As a direct result of that presentation, Member of Parliament Gerald Kaufman authored two letters on Graham's behalf and sent them to Texas Gov. Ann Richards. Those letters were co-signed by 38 additional members of Parliament.

6) Rep. John Lewis (D-GA) presented an appeal on Graham's behalf to a session of the U.S. House of Representatives in 1993.

7) Organizations such as Amnesty Intl. and individuals such as Danny Glover have earned the right to be highly respected in the civil and human rights struggles. Their dedication and contributions are recognized and admired by JFA. In viewing Graham Coalition material, it is highly probable that Glover, and maybe others, were originally lied to about this case. By the time they became aware of the lies of Graham and others, the case had become a worldwide cause celebre', thus making it difficult to back away from: The cost to the anti-death penalty movement would just be too great. There cannot be any excuse for those Graham supporters who continued their support after this fraud was exposed. Ignorance and aversion to the truth was strictly voluntary.

8) Former Texas Governor Ann Richards stated that she granted the stay of Graham's execution based on questions about the case. She would not say what those questions were, nor would she state if those questions were ever resolved. She further stated that she did not want to publicly discuss this case, fearing that she may improperly influence future decisions (Governor Richard's letters.) We find it strange that Governor Richards had no problem commenting publicly on another high profile Texas death penalty case, that of Vermont native Robert Drew. JUSTICE FOR ALL and Graham's Coalitions agree on one thing: Hollywood's involvement in Graham's case was crucial to Governor Richard's stay.

9) JFA makes sure that all known Graham supporters receive our information on this case. Conversely, those supporting Graham will not give us any of their material. Why do you think that is? Specifically, any complete investigation of this worldwide fraud should include all published material produced by Graham supporters including Amnesty Intl., NCADP, all GGC flyers, all ENDEAVOR Newspapers, all Graham Legal Defense Fund Newspapers, all films about this case, a complete NEXIS search for all articles about this case. Based upon our limited research, the amount of false and misleading information produced by Graham supporters and irresponsible journalists will be staggering.

10) The six wealthiest known supporters (?) of Graham are collectively worth over $1,000,000,000. Why are Graham's Coalitions constantly holding fund raisers in Houston (and we presume elsewhere) when 1/10 of 1% interest on $1,000,000,000 is $83,000/month or $1,000,000/year? We believe that many Graham supporters have withdrawn their support because they have learned, from JFA, that they were lied to.

11) JUSTICE FOR ALL believes that the anti-death penalty movement will have injured their credibility for years, WHEN the media fully investigates the case and the way it was orchestrated by that movement. 12) In the event that Graham's campaign is either successful in overcoming the integrity of the judicial process or he is ultimately executed, Graham's coalitions will likely continue to use their false claims. The end will always justify the means.

I. SUMMARY

On May 13, 1981, at 9:35pm, Bobby Grant Lambert was robbed and murdered in a Safeway parking lot in north Houston, Texas. Four out of the original five witnesses described the murderer as a young, thin black male, from medium height to tall. On May 27th, 17-year-old Gary Graham, a 5'9", 145 lb. black male, was positively identified as Mr. Lambert's murderer by Bernadine Skillern, the one eyewitness who clearly saw the killer's face. Five months later, Graham was convicted of the murder and sentenced to death. Graham had been previously arrested on May 20th for a crime spree that included at least 22 criminal episodes, which involved 20 armed robberies, 3 kidnappings, 1 rape, and 3 attempted murders; a crime spree which was later found to include the murder of Mr. Lambert. There are 28 known victims of this crime spree, resulting in 19 eyewitnesses who have positively identified Graham.

Twelve years later, the tireless efforts of Susan Dillow, Graham's California pen pal, and actor Danny Glover began to publicize what they originally believed to be the pending execution of an innocent man. Their efforts resulted in a worldwide campaign to free Gary Graham. There are, primarily, three reasons why this campaign has been so successful:

(1) Those initial efforts stimulated the interest of media, of additional well-meaning individuals and of anti-death penalty forces. As some of Graham's supporters began to learn the true facts of the case, their voices grew silent. Other, more high profile supporters, who have tied their reputations to Graham will not disentangle themselves from this dishonorable fraud. Are they afraid of looking even more foolish? Some, like Kenny Rogers, are honorable enough to publicly withdraw their support (2/5/94 TV Guide). Many others have quietly withdrawn.

(2) The coalition of anti-death penalty individuals and organizations will use any means necessary to achieve their goals, regardless of the guilt or fabrications involved. All of Graham's support comes from those who are either ignorant of the case facts or from those dishonorable enough to ignore the facts altogether. Orchestrated through Amnesty International and public relations firms in New York (Riptide) and Texas (Steven Hall), this campaign has invested millions of dollars, worldwide, to promote Graham's false claims. JFA believes that this has been the most extensive and expensive propaganda campaign ever conducted by anti-death penalty forces, for any one case.

(3) With no evidence of investigative journalism, some members of the worldwide media, notably Nightline, the New Yorker (8\16\93), The New York Times (Injustice in Texas, 6/3/93 and Dead Man Walking, 5/26/93), The Washington Post (5/29/93, 8/1/93 and 8/18/93) and LEAR's (3/94), have contributed to this fraud - with some intentionally disregarding known facts. (Reviews upon request.) Fortunately, the thorough investigative work of Susan Warren (Houston Chronicle The pro-Graham movement is a cynical fraud wherein lies, half-truths and intimidation have come together in an attempt to free the guilty and punish the law abiding. This movement has nothing whatsoever to do with the guilt or innocence of Gary Graham. If not for the death penalty, few people outside the immediate scope of the Graham murder case would have heard of Gary Graham. The pro-Graham movement is mounting an assault by death penalty opponents to abolish the death penalty in Texas and throughout the United States. But for most Texans, it is more than that. It is an attack on our safety.

In Gary Graham they have picked the wrong person and, clearly, the wrong case.

Note: JUSTICE FOR ALL, a criminal justice reform organization, produced this report in order to challenge a world wide fraud perpetrated by Gary Graham's Coalitions (GGC) and the anti-death penalty movement. Should you require any supporting documentation, we are at your service. JFA enthusiastically welcomes all challenges to this report.

II. THE DIRECT APPROACH: LIES AND GARY GRAHAM'S COALITIONS

INTEGRITY should be the building blocks of all just causes, particularly one involving a death row inmate whose supporters claim was wrongfully convicted. Unfortunately, Gary Graham's Coalitions ("GGC") and their many participants (including, Susan Dillow, Danny Glover, Amnesty International, The Texas Resource Center, The National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty, etc.) need to be much more careful in their statements of "fact". Each of the following paragraphs begins with GGC statements, usually followed by a bold False, indicating the falsehood of that statement, then followed by the factual information, as per the record. Most of the literature is taken directly from GGC material and/or Texas Resource Center attorneys' statements, and is not taken out of context.

FALSE CLAIM 1 - Bobby Lambert was shot in a dimly lit parking lot.

False. Bernadine Skillern, the unwavering eyewitness had no problem identifying Graham. Stated Skillern, "You can see very clearly." Other witnesses and three policemen testified that there was adequate lighting to make an identification. Wilma Amos testified that the lighting "was good." (Trial Testimony.) Furthermore, GGC often state that there were only two lights in the entire parking lot. Half-Truth, Misleading. What GGC doesn't say is that there were at least two light posts with a total of four lights and that all four lights were close to the murder scene. Two of the lights were within two parking spaces of the murder and thereby directly illuminated the murder scene (crime scene photos). Furthermore, Ms. Skillern's car was facing the murder scene from 26-37 feet away and her car's headlights further illuminated the murder scene and Graham's face. Graham, then walked within 10 feet of Ms. Skillern. (Crime scene evidence and trial testimony.)

FALSE CLAIMS 2, 3, 4 & 5

Graham was convicted and sentenced (2) to death by the questionable (3) identification of a single witness who saw the suspect for a "split second" (4) from a distance of approximately 35-44 feet. False 5. In her second viewing of mug shots (Graham's picture wasn't part of the first photo spread.) Ms. Skillern immediately picked out Graham, noting that his features, with the exception of skin tone, were the same. The shade of the skin in the photograph wouldn't allow her to make a positive identification and she stated she would need to see a live "line-up". She made an immediate, unequivocal, positive identification of Graham at the line up(F3). (Police and Trial Testimony.) Ms. Skillern testified that she saw the killer "full-face" three times, for 2 to 3 seconds, and had observed him for 60 to 90 seconds(F4), at distances ranging from a car length (10 feet) to 33 to 44 feet(F5). Graham was found guilty on the testimony of Ms. Skillern, but was sentenced to death because of the testimony of ten (10) additional Graham victims, other witnesses and the careful consideration of 12 jurors who felt that Gary Graham was a vicious killer who posed a continuing threat to society(F2). (Trial testimony and jurors statements.)

"For the people to say I'm tragically mistaken is an insult because I saw that man (Graham) and nothing will ever change that. He knows that I saw him (kill Bobby Grant Lambert) and I know that I saw him, and the Lord knows. I am not responsible for Mr. Graham's fate. He is." (Bernadine Skillern, Houston Post, August 15, 1993.)

Obviously, the jury agreed. The multi-racial jury voted 12-0, on the first ballot, for guilt in the guilt/innocence stage. The vote was 12-0 for death, on the second ballot, in the punishment phase. (10-2 on the first ballot.) All ballots were secret. (Juror Statements and Trial Records.)

FALSE CLAIMS 6, 7, 8 & 9

Four other crime scene witnesses did not identify Graham as the gunman and stated that the gunman was approximately 5'5" tall. False 6. Four out of the original five witnesses described the killer as a young, thin black male, from medium height to tall. Graham, a 17 year old black male, was 5'9", slim, 140-150 lb. Skillern stated he was 5'9" to 6', slender, 145 to 150 lbs. Dan Grady said he was tall and slim. Ron Hubbard said he was 5'5" to 5'6". Leodis Wilkerson described the killer as shorter than Lambert. Lambert was 5'9". According to GGC flyers, the killer must have been 5'8". Wilma Amos told police he was of medium height but that she couldn't remember how the killer looked. Incredibly, twelve years later, in April 1993, after speaking to The Texas Resource Center, Amos says it wasn't Graham and that the killer was 5'5". In videotaped testimony, aired at a mock(ery) trial in August, 1993, orchestrated by The Texas Resource Center, Ms. Amos stated that, "He (the killer) was no taller than me." Amos is 5'2". (The Texas Resource Center Videotape.) False 7 (see previous police statement). Amos also stated that, "...when I saw him standing there with that gun, I just closed my eyes." "...he just stopped for a second not far from the back of my car and then he took off..." (Trial and Videotape.) Amos (or Etuk) told defense investigator, Mervin West, "She thought he (Graham) had a similar build to the guy who did the shooting." (West's Affidavit) The newest witness discovery by The Texas Resource Center is Sherian Etuk who was working at the supermarket at the time of the killing. It is claimed that as of July, 1993, Etuk has looked at photographs of Graham, taken at the time of the murder, and is sure Graham was not the killer. Only one catch. At the time of the murder, Etuk's statement False 8. to police reveals that she never saw the man's face or the murder. The witnesses who could not identify Graham either did not see the killer's face, couldn't remember it, only saw a black man (the killer, an accomplice, anyone, who knows?) running through the parking lot or didn't see a gunman because they didn't see the crime. It is important to note that all of the witnesses describing the killer as of medium height to tall saw the killer standing. The other witnesses, including Hubbard, saw a black man of 5'5" to 5'7" running through the parking lot. A 5'9" running man would lose at least 4" in height due to bent ankles, knees, back and neck, which is the posture of a person in the act of running. (Trial, etc.) Hubbard originally told police he possibly could I.D. the killer. Later, at the live line-up, he told police and Graham's attorney's that he never saw the killer's face and couldn't I.D. anyone. (Police File, via GGC.) Leodis Wilkerson, who was 12 years old at the time of the shooting, witnessed Lambert's murder. His account of the crime scene, and that of two of his friends, in the car with him, was relayed to police by an adult relative. The statement was that they had seen a man running in the parking lot who they thought looked like Curley Scott, the boyfriend of Mrs. Brown's daughter. Scott, a 5'11", thin black male, was cleared of any involvement. (Graham's Legal Defense Committee Report, Winter, 1994). Half Truth, False 9 Dan Grady was unable to identify Gary. Grady couldn't identify anyone. He stated he could, maybe, I.D. the gun, but not the killer's face. (Trial). Bobby Lambert was wrongfully listed at 5'6" by the coroner. His height was correctly established at 5'9" in March 1994.

THE WILMA AMOS REVIEW

JUSTICE FOR ALL agrees with Graham supporters that Ms. Amos is the single most credible witness for Graham's defense. The following reviews the ever-changing testimony of Ms. Amos. Each point compares statements she has made regarding specific events. The comparisons are not taken out of context. 1) I never saw the gun vs. I saw the gun; 2) I went home (after the shooting) and drank a half a fifth of vodka vs. "I don't keep no vodka" vs. "I took a valium"; 3) the assailant was medium height (5'9") vs. 5'5" vs. 5'2"; 4) I saw the assailant twice vs. I saw the assailant 3 to 4 times; 5) I saw the assailant leave (the Safeway) before Bobby Grant Lambert vs. after; 6) Just as I got out of the store, I heard a shot vs. I left the store and went to my van, I saw the two men struggle and then I saw the man get shot; 7) the assailant stood 3 or 4 feet in front of my face vs. we were face to face vs. I was standing in the middle of my van and he was at the back of my van vs. I was at the front of my van and the assailant wasn't far from the end of my van; 8) the assailant stood there for a few minutes vs. a second; 9) I forgot how he (the assailant) looked vs. it is not Gary Graham; and 10) Amos doesn't remember being cross examined by defense attorney Ron Mock vs. there are over 15 pages of trial testimony, with well over 200 questions and answers involving Mock's cross examination of Amos. (Sources: Trial Testimony, Houston Press, GGC, The Texas Resource Center videotape, and Police File, via GGC.)

FALSE CLAIM 10

Two new witnesses (Malcolm and Lorna Stephens), unknown to prosecution and defense, have come forward, and said Graham was not the killer. One claims not only to have seen the actual murderer in 1982, 1983 and 1985 but also to have spoken with him. Half-Truth, Deemed unreliable. These witnesses have come up with conflicting and incredible statements, some totally contrary to the actual crime scene evidence, twelve years after the murder and after speaking with The Texas Resource Center. They both stated that they intentionally left the scene without approaching the police to give statements and now state that the man they saw could have been anyone. (review of statements and Houston Chronicle, July 4, 1993.)

FALSE CLAIM 11

Almost all the witnesses who have evidence and testimony that prove Gary Graham's claim of innocence have never been heard in a court of law or in impartial hearings. Totally false. None of those witnesses prove Graham's claims of innocence. Furthermore:

A. (1) Alibi-Witnesses: The affidavits of four purported alibi witnesses were presented in Graham's writ of habeas corpus (ineffective assistance of counsel claim) in 1987, six years after the original trial. Mr. Doug O'Brien,

Graham's appellate attorney, presented two of the four witnesses at the writ hearing in 1988, where District Judge Don Shipley deemed them not credible. Their hearing testimony was truly incredible. In order not to injure Graham's case any more, O'Brien chose not to present the two other purported alibi-witnesses, one being Loraine Johnson. Furthermore, the judge determined that no one ever came forward, prior to the original trial date, as an alibi witness, and that Graham never submitted alibi witnesses to Ron Mock or Chester Thornton, co-counsels for Graham's defense, with the exception of a girlfriend that Graham said he was with the night of the murder, a girlfriend whose name, face and address he couldn't remember. (Hearing Record and False Claims 12 & 22 and pages 8-9, Paragraph A.2.b.) Funny that Graham couldn't remember his girlfriend, Mary Brown, who later became his wife. Maybe Graham is lying? Funny that Ms. Brown didn't come forward in 1981, but later came forward in 1986 as an alibi witness. Maybe it was another girlfriend? Funny that Graham said he was alone with a girlfriend the night of the murder and now we have four (five?) people who say they were with him. Funny we have two completely different stories from Graham and the alleged alibi-witnesses.

(2) Polygraph tests orchestrated by The Texas Resource Center are daily trumpeted by Graham's backers as proof that the four alibi witnesses are telling the truth. However, the head polygrapher for Texas' Department of Public Safety and Eric Holden, President of the American Polygraph Association, both conclude that the tests are not valid and are worthless. (Houston Chronicle, July 4, 1993.)

(3) Isn't anybody curious as to why none of these alibi witnesses came forward in 1981, knowing that Graham's life was on the line. They have all stated that none of them came forward on their own, that it was Graham's grandmother that got them together so they could give alibi statements to say Graham was with them. Defense attorney Thornton tried to get Graham's family members and friends to come forward to testify on Graham's behalf in 1981! Graham's family knew Thornton because he was also Graham's juvenile attorney (KPFT, 90.1 FM, Houston). Funny, no alibi-witnesses came forward then. Three of the four alibi witnesses are Graham's relatives and when asked why they did not come forward in 1981, they say "No one asked me." One of the alibi witnesses was Graham's girlfriend, Mary Brown, who later became his wife. If a relative (or lover and future spouse) of yours was on trial for murder, and you knew that they were with you the night in question, would you wait 5 years until someone asked you to come forward? (See page 9., 2.b.)

B. Crime Scene Witnesses: Virtually all of the crime scene witnesses offered prosecution, not defense, testimony, in 1981, if they offered any thing at all. Even Doug O'Brien, Graham's 1986-88 appellate attorney, intentionally did not present any crime scene witnesses at the 1988 court hearings. He didn't call them because they had nothing to offer for the defense. Only 12 and 13 years after the murder, has some of their testimony changed enough to be of use to the defense. (See False Claims 1-10 and page 8, Paragraph A.2.a.)

"In every case they (the witnesses supporting Graham) are changing their stories, often fairly abruptly, from what they said or testified to twelve years ago..... New witnesses have materialized out of thin air....." My prediction is that as the case goes on, thrill seekers like this will continue to appear." (Gregory Curtis, Editor, Texas Monthly, October 1993.)

C. (1) Gary Graham's defense claims have been reviewed 9 times by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (the highest criminal court in Texas), 2 times by the Texas Supreme Court, 4 times by the U.S. Supreme Court and in a total of thirty-three (33) judicial or executive proceedings. (Houston Post, July 29, 1993 and subsequent events, as of 9/8/96.)

(2) a. Federal District Court Judge David Hittner ruled that all of Graham's new evidence is not sufficient to entitle him to a federal hearing and refused Graham a hearing or a stay of execution. He also stated that several of Graham's new witnesses were not credible. (Houston Post, August 16, 1993 and Houston Chronicle, August 14, 1993.)

b. After a thorough review of all the "new evidence", by himself and his staff, Texas Attorney General Dan Morales stated, "...that none of that new information is credible. There is no new evidence. Graham is stalling for time." The "new evidence" and "revised" witness statements are ""stoned-cold manufactured evidence." (Houston Chronicle, August 15, 1993, Houston Sun August 16, 1993 and The Texas Observer, August 20, 1993.)

c. On April 26, 1993 after a thorough review of the "new evidence" the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles voted: (Houston Post, August 13, 1993.); 12-5 Against a hearing on new evidence.12-1 Against recommending commutation of Graham's sentence to life.10-7 Against a stay of execution.13-0 Against a conditional pardon.The Board found that there is "no credibility to any of the alleged new information". (Houston Post, August 14, 1993.)

d. The Houston Post agrees that the new evidence is not credible. (Houston Post, August 13, 1993.)

FALSE CLAIM 12

Mervin West, a former police officer and private investigator for Gary Graham's defense lawyers in a sworn affidavit (dated 1993) swears "...we assumed Gary was guilty from the start, we did not give his case the same attention we would routinely give a case. Gary Graham gave Ron Mock a list of alibi witnesses. I did not talk to any of Gary's alibi witnesses." Half Truth and Contrary to the Evidence. The same affidavit states that West, "Recently found the 'lead sheet' from Gary's case. It had only two individuals on it." These two individuals were crime scene witnesses. There were no alibi witness names in the file. The "lead sheet" is where West kept the names of witnesses in his case investigations. "The black female was helpful even though she could not identify Gary as the shooter. She thought he (Gary) had a similar build to the guy who did the shooting." In a later affidavit, April 22, 1993, West stated, in recalling events twelve years ago, that his memory "could be faulty as hell due " to being "without oxygen for a long, long, time, resulting in some brain cell destruction and significant memory loss." "I am totally aware of the fact that I have before recalled an event one way when it in fact occurred an entirely different way, and that there are holes in my memory." (April 22, 1993 Affidavit.) West's own file notes, revealed in the first affidavit, support the prosecutor's case. West's recollections, in the first affidavit, are not only contradicted by the hard evidence in his file, but are made void by his second affidavit. Furthermore, defense attorneys Mock and Thornton both met extensively with Graham prior to the 1981 trial. They have both stated that Graham never mentioned alibi witnesses, with the exception of a girlfriend whose name, face and address Graham could not remember. (See False Claim 11 and Paragraph A.2., pages 8-9)

FALSE CLAIMS 13, 14 & 15

(Regarding the gun and ballistics report) the Prosecutors gave jurors a false impression that Gary Graham was guilty. False 13. The gun was not introduced until after Graham had been found guilty. A medical examiner testified at the trial that the victim, Bobby Lambert, was killed by a .22 caliber bullet. Later, a Houston Police officer testified that a .22 caliber pistol was recovered from Graham at the time of his arrest. Half-Truth, Misleading. The police officer did not testify until the punishment phase, after Graham had been found guilty. Yet the D.A. had in its possession a ballistics report (withheld from the defense) that concluded that the fatal bullet was not fired by Mr. Graham's gun. False 14 & 15. The defense also had a copy of the ballistics report, but did not challenge the gun issue. Had defense counsel brought it up, that would have opened the door to Graham's nine (9) other weapons and their attendant crimes and 27 additional victims, none of which or whom was introduced in the guilt/innocence stage of the trial. (Trial Testimony and Houston Chronicle, August 19, 1993.) JUSTICE FOR ALL contends the bullet was fired by Graham's gun, just not one of the 10 in his possession.

FALSE CLAIM 16

Ashanti Chimurenga, Amnesty International lawyer, has repeatedly stated that Graham victim Greg Jones (attempted murder, aggravated robbery) told Gary Graham's son, Gary, Jr., that he (Greg) wanted his father (Gary) dead. (1590 AM, Houston, Rev. Boney's radio show) Cruel, Slanderous and False. This encounter was witnessed by a dozen people and was reported in the press as follows: Greg Jones said to Gary Jr., "I don't have any ill will towards you and hope that you have a good life." Stated Jones, "(Graham's children) are just fighting for their father's life and I think they should do that." (Houston Chronicle, Oct. 2, 1993). Greg Jones personally called Rev. Boney, the Houston leader for Graham's Coalitions, and asked him to correct these false and slanderous statements. No correction was aired. Ms. Chimurenga persists. The Houston Chronicle called that brief meeting between Jones and Gary, Jr. "a gesture of peace." Note: Ms. Chimurenga has spoken to many groups on behalf of Amnesty International and GGC. Her speeches reflect much of the FALSE material from GGC and some of those speeches have been filmed.

And the question remains, "Why is it necessary for Graham and his supporters to consistently lie about the case if he is innocent?"

For the past twelve years, the only witnesses whose testimony has remained steadfast and unerring have been that of Bernadine Skillern, the ten (10) victims and witnesses who testified against Graham during the punishment phase of the trial and the additional victims of Gary Graham.

III. THE CYNICAL APPROACH:

GARY GRAHAM AND THE "ENDEAVOR"

GARY GRAHAM is a founding editor and writer for the Endeavor newspaper, an anti-death penalty, death row inmate publication, funded by Amnesty International and the National Coalition to Abolish The Death Penalty, among others. It does, however, seem to be a propaganda rag which appears to slander a witness and to lie to support Gary Graham's defense. What do Endeavor and Gary Graham have to say about the case? The Endeavor material is taken directly from the newspaper and is not taken out of context.

FALSE CLAIMS 17 & 18

Graham was convicted solely on the fabricated testimony of one witness (Bernadine Skillern) who was coerced into identifying Graham. Graham ponders: What relationship did Skillern have with Bobby Grant Lambert (the murder victim)? Did Skillern have a criminal record? If any, what kind of deals were made in exchange for her fabricated testimony? (Endeavor, Summer 1992 and Spring 1992.) Slanderous and False. Absolutely no evidence has been brought forward by either side to support any of this.

FALSE CLAIM 19

"... it was reported that (defense attorney) Mock and Skillern had been acquainted for a number of years. Perhaps that explains why Mock was reluctant to discredit Skillern's testimony..." (Endeavor, Spring 1992.) Slanderous and False. Absolutely no evidence has been brought forward by either side to support this.

FALSE CLAIMS 20 & 21

Graham wrote that he had robbed six or seven people but that, fortunately, none of those were seriously injured, physically. (Endeavor, Spring 1992.) Outrageously False. Graham pled guilty to ten aggravated robberies, wherein he attempted to murder two victims, one was shot in the neck and the other in the leg. Reportedly, the leg could not be saved. One victim, a 57 year old woman, was kidnapped and repeatedly raped. Pistol whippings and terror were common tools of Graham's trade. Eleven (11) additional cases have been cleared with the identification of Graham's involvement. In one of those cases, David Spiers became another man shot in the leg. He nearly lost his leg and his life. Both David and his fiancée positively identified Graham. It was two years before the victim could walk unaided. And, of course, Bobby Lambert was murdered. (Houston Post, 5/23/81, etc. and Police file information released as per Open Records request by the Texas Resource Center, 1993.)

FALSE CLAIM 22

Graham states that he had the four alibi witnesses sign affidavits. JFA believes that he did in fact do that. Graham further states that his two alibi witnesses who testified in the 1988 hearing, "...both attested to the fact that prior to my trial I had informed them that my state appointed lawyer (Mock) would be calling them to testify." (Endeavor, Winter 1993.) Totally False. The opposite was true. Both witnesses testified that they had never heard from Graham prior to the trial. (1988 Hearing Testimony.)

FALSE CLAIM 23

Characteristically, in the kidnap, rape and robbery case, Graham actually accuses the victim of robbing him. (Endeavor, Spring 1992.) False. Graham pled guilty to aggravated robbery in the case. After Graham passed out in her apartment, the rape victim testified to getting her money, and some of Graham's, from his wallet. She also testified that:

"When I knew he was going to rape me I told him I was 60 years old. He then hit me in the face and said 'don't lie.' He said 'I'm going to fuck you in the ears and the eyes and every place else.' He raped me until I couldn't stand it any longer and I screamed and he stopped. He then attempted anal sex. I was screaming and crying and shaking very, very hard... I was in great pain at that moment, great pain." (Trial Testimony.)

FALSE CLAIM 24

Graham further states that he knows he never killed anyone, and he simply cannot understand how or why someone would claim otherwise. (Endeavor, Spring 1992.) False. Graham told one robbery victim, Rick Sanford, that he had killed six people already and if the victim wanted to be seven to do something stupid (Trial Testimony). To the 57 year old rape victim, Lisa Blackburn, Graham stated, "I have already killed three people and I'm going to kill you. You don't mean nothing to me bitch." (Trial Testimony and CBS, Channel 11 News, Houston, 10:00pm, July 29, 1993.) In addition, to Ms. Blackburn Graham stated "I don't have nothing to lose. I don't plan to get caught. If I get caught, I burn, and I'm not getting caught." (Trial Testimony.) To one of the shooting victims, David Spiers, Graham said, after I kill you, I am going back (to your broken down car) to kill your fiancé and her parents so they can go with you to "honky hell". Before I kill your fiancé I'm going to rape her. (From David Spiers' letter.) Michael LeRoy Breazeale was arrested for attempted murder in January 1982 and was put in a cell next to Graham at the Harris County Jail. Graham told Breazeale that, not only did he shoot this guy from Arizona (Lambert), but that he enjoyed it and that he had shot other people and that we are all prey out there. Graham stated "I've already killed a tourist and I'll kill you too. You're just a tourist in jail." (Public News, Houston, July 9, 1993.) After making victim Richard Carter, Jr. kneel down and after putting a shotgun in his mouth, Graham stated, "I'll kill you, too. Blowing away another white mother fucker don't mean nothing to me." (Trail Testimony). For four (4) consecutive days after the trial, Carter received phone calls, calls he believes were from Graham, where the following was said, "I'm going to kill you when I get out. I'll hunt you down and kill you before I die". (Richard Carter Statement.) After the death sentence was imposed, court bailiff Larry Pollinger escorted Graham to a holding cell. Graham stated, "Next time, I'm not leaving any witnesses." Pollinger reported the incident the same day to Assistant Harris County District Attorney Carl Hobbs, who confirms the account. (Newsweek, August 9, 1993.) Truly, it was only providence that saved the many intended murder victims above.

DAMAGE BY THE ENDEAVOR

As the founder of and writer for the ENDEAVOR, and as the President of THE ENDEAVOR PROJECT, Graham's lies and distortions taint every story by all death penalty abolitionists, including death row inmates, who write for any publication. This seems to be of little concern to those who support the anti-death penalty movement and the ENDEAVOR.

Those participants in Graham's Coalitions and in THE ENDEAVOR PROJECT who stand by and do nothing when fraud becomes an integral part of strategy have become a source of betrayal and distrust that has an adverse affect on that movement. Those who actively participate in the lies and distortions, if allowed to continue, will cause grievous harm.

The abolitionist movement has squandered millions of dollars and man-hours on fraudulent cases. As lies, half-truths and intimidation continue to be the foundation of these worldwide causes celebre', the abolitionist movement will continue to loose credibility. It happened to the Shepherd Boy who cried wolf and it will happen to these frauds as well.

Note: The Endeavor ceased publication for most of 1994. JUSTICE FOR ALL believes that occurred because the lies finally caught up to them. In the Winter 1995 Endeavor, Graham did not mention one word about his case. Maybe Graham and his fellow Endeavor writers and editors will attempt to stop lying or, at the very least, limit their tales to half-truths.

Graham's well documented lies and distortions have been so blatant that, should Graham somehow get any opportunity to testify, his attorneys would have to advise him to keep quiet. (JUSTICE FOR ALL).

"In short, Gary Graham is a liar, a fact that should trouble those who are staking their time, effort and reputations on his claims of innocence. Even worse, his writings reveal him to be cold enough to be a killer after all." (Texas Monthly, October 1993.)

IV. INADEQUATE COUNSEL? AND THE TEXAS

CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM

Pro-Graham supporters have consistently attacked Graham's attorneys' defense and the State of Texas, both of which, they say, contributed to a terrible miscarriage of justice. Let's look at the facts.

A. Inadequate Counsel: Graham supporters have specifically targeted Ron Mock, one of Graham's 1981 attorneys. Somehow Chester Thornton, Graham's 1981 co-counsel, and Doug O'Brien, Graham's first appellate attorney, have escaped their wrath. Thornton knew Graham's family because he was also Graham's juvenile attorney. Thornton contacted Graham's family members for the trial in 1981, hoping to get them to come forward on Graham's behalf. Funny, no alibi witnesses came forward then. Thornton was equally responsible for Graham's defense. Doug O'Brien had every opportunity to present all of Graham's known alibi and crime scene witnesses at Graham's 1988 hearing. Why didn't he? See 2.a. & 2.b., below.

1) Target Mock - The GGC has made a mission of ruining Mock's reputation, to destroy him professionally, economically. Why?

a. Make Mock Capitulate - Graham supporters believe that if enough damage is done to Mock's professional, economic life, that Mock may assist them in their efforts. To a small degree that pressure may be getting to Mock. States Mock, "...when you're talking about killing somebody on the testimony of one eyewitness, it bothers me." This was the first time in 12 years that Mock publicly expressed this concern. Conversely, over the past 12 years Mock has repeatedly stated his confidence in the trial. (Houston Press Feb. 16, 1994. JFA's reviews of Houston Press articles regarding this case are available upon request.) (See False Claims 2-9.)

b. Mock's Capital Trial Record - Graham's supporters have repeatedly attacked Graham's attorneys' competence, based upon the fact that 12 of Mock's 16 capital case clients have ended up on death row. What they don't tell you is that Harris County (Houston) juries sentence murderers to death in 75% of those cases where the District Attorney's Office, the Penal Code, the crime and the evidence deem capital punishment appropriate (see Page 9, Paragraph C.) Mock's capital trial record is identical with the sentencing record of Harris County juries. Furthermore, Ron Mock is noted as consistently taking the worst of the worst cases, cases often turned down by other attorneys. Mock does, however, have a mixed reputation (Houston Press, 2/16/94) . His handling of the Graham case is under attack, however, because, 1) that is part of the agenda to free Graham and 2) Graham's supporters argue that another trial strategy would have exonerated Graham. Although that is FALSE 25 (see A.1.c. and A.2. and 3., below), it is easy propaganda fodder.

c. Ineffective Assistance of Counsel claims are almost standard in death row appeals. However, to prove this claim, Graham's new attorneys must prove that Mock's and Thornton's trial strategy (see A.3., below) was not sound strategy. Not surprisingly, in Graham's case, all state and federal courts have, so far, rejected this claim.

"That Graham's attorneys kept their client's myriad armed robberies and shootings from the jury is a fact conveniently overlooked by those so critical of the conduct of the trial." (Texas Monthly, October 1993.)

2) Lack of Investigation - Graham supporters claim that the defense's lack of investigation is what led to Graham's conviction. What did the defense team know in 1981?

a. Eyewitnesses - In 1981, Amos, Hubbard, Etuk, Wilkerson and Grady couldn't identify the killer as Graham, or as anyone else. Nor could they, or did they, say it wasn't Graham. Skillern positively identified Graham. Skillern, Grady, Amos and Wilkerson all identified the killer as a young, thin black male, from medium height to tall. Graham was 5'9", 145 lbs. Amos (or Etuk) described the killer as having a similar build to Graham. Malcolm and Lorna Stevens did not come forward until 1993. (See False Claims 6-10 and 12).

b. Alibi-Witnesses - Loraine Johnson (one of the 4-5 purported alibi witnesses) states, in 1993, that she told Mock or Thornton, at the 1981 trial, that she was an alibi-witness. Not only do Mock and Thornton both deny being told that, Doug O'Brien, Graham's appellate attorney (from 1986-88) also denies being told that. O'Brien even refused to put Ms. Johnson on the stand in the 1988 appeals hearing. Ms. Johnson curiously forgot to mention that purported 1981 conversation in her 1987 affidavit. She decided to wait twelve years before swearing to this purported incident. The purported alibi-witnesses first came forward in 1986, five years after Graham's trial. (See False Claims 11, 12, & 22.)

c. The Single Eyewitness - Because of Graham's voluminous criminal pursuits, it was mandatory that defense counsel prevent Graham's criminal rampage from entering the guilt/innocence stage of the trial. Counsel knew that Graham's only chance to avoid life imprisonment or the death penalty was to get a verdict of innocent. Therefore, defense strategy consisted of challenging the single eyewitness in an attempt to create "reasonable doubt" in the minds of the jury. This is precisely what Mock and Thornton told jurors when the trial was over (Jurors' statement). Had defense counsel allowed any testimony into the trial which opened the door to Graham's other "similar crimes", then charges of inadequate defense counsel would be justified. (See False Claims No. 20, 21 & 24, & Chapters VI & VII.) 1981 Presiding Judge Richard Trevathan, who has served in numerous murder trials as either prosecutor, judge or defense attorney, called Bernadine Skillern:

"...The most impressive and believable witness (I) had encountered in twenty (20) years of courtroom experience." (Human Events, September 4, 1993.) (See full bold paragraph on page 15.)

d. The Gun Issue - (See False Claims 13, 14 and 15).

3) The Victim: GGC have relentlessly attacked the character of Graham murder victim Bobby Lambert. They state that Lambert was the victim of a professional hit because of Lambert's alleged cons and drug activities. (GGC public access video, other publications.) LUDICROUS. Even the testimony of GGC prize witness, Wilma Amos, rebuts such an assumption. GGC further states that Lambert's roommate mysteriously disappeared and was never questioned in the murder. FALSE 26. Even one of Graham's attorneys, Robert Jones, stated that the roommate had been questioned. He was released because he was not a suspect. (Rev. Boney's radio show, KYOK 1590 AM, Houston). Ashanti Chimurenga (Amnesty International) states that Lambert's van contained illegal weapons. FALSE 27. Lambert was moving from his home in Arizona. As such, his van was full of his belongings, including 3 legal shotguns. A small amount of marijuana was found in the glove compartment. This red herring goes on and on and on.

B. Perjury and Threats Against Witnesses:

We call on the Harris County District Attorney, the Texas Attorney General and the U.S. Justice Department to investigate the ever changing testimonies of Graham's new and old witnesses and the involvement of The Texas Resource Center and other attorneys, therewith. Furthermore, such investigations should review the threats and acts of intimidation against Bernadine Skillern and the other victims/witnesses who have or would testify against Graham.

C. The Texas Criminal Justice System:

1) The Texas Death Penalty - Request JFA’s Death Penalty and Sentencing Information report.