1st murderer executed in U.S. in 2013

1321st murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Virginia in 2013

110th murderer executed in Virginia since 1976

Executed January 16, 2013 9:08 p.m. by Electric Chair in Virginia

1st murderer executed in U.S. in 2013

1321st murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Virginia in 2013

110th murderer executed in Virginia since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(1) |

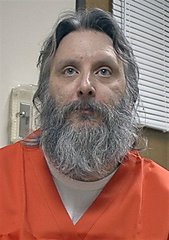

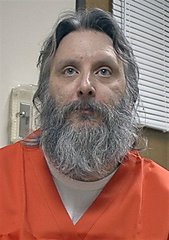

Robert Charles Gleason Jr. W / M / 39 - 42 |

|

Harvey Gray Watson Jr. W / M / 63 Aaron Alexander Cooper W / M / 26 |

07-28-10 |

Strangulation With Towel |

Cellmate |

Citations:

Gleason v. Commonwealth, 726 S.E.2d 351 (Va. 2012). (Direct Appeal)

Gleason v. Pearson, Slip Copy, 2013 WL 139478 (W.D.Va. 2013). (Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

Confidential upon request.

Final Words:

“Well, I hope Percy ain’t going to wet the sponge. Put me on the highway to Jackson and call my Irish buddies. Pog mo thoin. God bless." In Irish Gaelic, the phrase “Pog mo thoin,” is translated as "Kiss my ass."

Internet Sources:

"Va. inmate executed for killing 2 fellow prisoners," by Dena Potter. (Associated Press January 17, 2013)

JARRATT - A man who strangled his prison cell mate and made good on a vow to continue killing if he wasn't executed was put to death Wednesday in Virginia's electric chair. Robert Gleason Jr., 42, was pronounced dead at 9:08 p.m. at Greensville Correctional Center. He became the first inmate executed in the United States this year and the first to choose death by electrocution since 2010. In Virginia and nine other states, death row inmates are allowed to choose between electrocution and lethal injection.

Gleason was serving life in prison for the 2007 fatal shooting of a man when he became frustrated with prison officials because they wouldn't move out his new, mentally disturbed cell mate. Gleason hog-tied, beat and strangled 63-year-old Harvey Watson Jr. in May 2009 and remained with the inmate's body for more than 15 hours before the crime was discovered. "Someone needs to stop it," he told The Associated Press after Watson's death. "The only way to stop me is put me on death row."

While awaiting sentencing at a highly secure prison for the state's most dangerous inmates, Gleason strangled 26-year-old Aaron Cooper through wire fencing that separated their individual cages in a recreation yard in July 2010. As officers tried to resuscitate Cooper - video surveillance shows he had been choked on and off for nearly an hour - Gleason told them "you're going to have to pump a lot harder than that."

Gleason subsequently said in phone interviews that he deserved to die for what he did. "The death part don't bother me. This has been a long time coming," he said in one of the many interviews from death row. Gleason said he only requested death to keep a promise to a loved one that he wouldn't kill again. He said doing so would allow him to teach his children, including two young sons, what could happen if they followed in his footsteps. "I wasn't there as a father, and I'm hoping that I can do one last good thing," he said previously. "Hopefully, this is a good thing."

Gleason had fought last-minute attempts by attorneys to block the scheduled execution. The lawyers had argued that he was not competent to waive his appeals and that more than a year spent in solitary confinement on death row had exacerbated his condition. Two mental health evaluations done before Gleason was sentenced in 2011 said he was depressed and impulsive but competent to make decisions in his case. Late Wednesday, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected a request for a stay.

Use of the electric chair remains rare in Virginia. Since inmates were given the option in 1995, only six of the 85 inmates executed have chosen electrocution over lethal injection. Cooper's mother, Kim Strickland, had made plans to witness the execution. She has sued the prison system over her son's death and said she hopes Gleason's family can have closure. "May God have mercy on his soul," Strickland said before the execution. "I've been praying and will continue to pray that his family can heal from this ordeal."

Watson's sister, Barbara McLeod, said she had "mixed feelings" about the execution but "didn't want him to be able to kill more people." She, nor anyone else from Watson's family, witnessed the execution.

Gleason did not visit with family before his execution. Inmate's families are not allowed to witness executions in Virginia. Some protested outside the prison on Wednesday, saying Gleason's threats to continue killing should not be a reason to justify execution. Despite Gleason's crimes and his insistence on being executed, "the state should not kill its own citizens under any circumstances," said Stephen Northup, Virginians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty's executive director.

"Va. executes convicted killer who sought death penalty," by Justin Jouvenal. (January 16, 2013)

A convicted murderer who killed two fellow inmates while serving a life sentence and vowed to keep on killing unless he was put to death was executed Wednesday night in Virginia. Robert Gleason Jr., 42, originally of Lowell, Mass., was pronounced dead at 9:08 p.m. at Greensville Correctional Center in Jarratt, the Associated Press reported.

He was the first death row inmate since 2010 in Virginia to choose death by the electric chair instead of lethal injection. There were no complications. He also was the first inmate to be executed in more than a year. He had one visitor Wednesday: a spiritual adviser.

Earlier Wednesday, the Richmond-based U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit denied a request by Gleason’s former attorneys to determine whether he was competent to waive his right to federal appeals. Gov. Robert F. McDonnell (R) announced last week that he would not intervene in the execution. Gleason’s attorneys also appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which declined to block the execution. “This is a bizarre case where the death penalty is actually the sole motivator for the killing,” said John Sheldon, one of the attorneys.

In court documents, the attorneys wrote there was “significant evidence” of mental illness in Gleason’s history, including prolonged bouts of depression and multiple suicide attempts. Wise County prosecutors declined to comment on the case before the execution, but they wrote in court filings that the trial court had found that Gleason voluntarily and intelligently waived his appeals and had actively sought the death penalty.

Gleason pleaded guilty to strangling his cellmate, Harvey Watson, with a bedsheet at the Wallens Ridge State Prison in 2009, saying under oath that he timed it to coincide with the anniversary of the killing for which he was sent to prison in the first place, according to court documents. Gleason later told the court that he “already had a few [other] inmates lined up, just in case I didn’t get the death penalty, that I was gonna take out.”

In 2010, he strangled another inmate through a wire fence in a recreation pen at the Red Onion State Prison, a “supermax” facility, according to court records. Prosecutors said he mocked the prison staff as they tried to revive Aaron Cooper. Gleason also pleaded guilty to that slaying and was sentenced to death in both killings. Gleason was given a life sentence for the slaying of Mike Jamerson in Virginia’s Amherst County in 2007. Prosecutors said he carried out that killing to cover up his involvement in a drug gang.

Virginia Department of Corrections officials said Wednesday that Gleason requested a final meal but asked that officials not tell the media what it was. As of late afternoon, officials said, he had received no visitors. Members of the victims’ families attended the execution. Gleason was the 110th person put to death in Virginia since the death penalty was reinstated in 1976 and the first since Jerry Jackson was executed in August 2011.

Virginians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty planned to hold a vigil outside the prison for Gleason and his victims. “Gleason’s case demonstrates the folly of capital punishment,” said Stephen Northup, the executive director of the group. “If we didn’t have a death penalty, he wouldn’t have killed these men.’’

"Va. man who killed two inmates is executed," by Frank Green. (11:26 pm, Wed Jan 16, 2013)

JARRATT - Robert Charles Gleason Jr., who strangled two fellow prison inmates, died in Virginia's electric chair Wednesday night, unapologetic to the end. Gleason, 42, was pronounced dead at 9:08 p.m. at the Greensville Correctional Center. Asked if he had a last statement, he said among other things, "Put me on the highway going to Jackson and call my Irish buddies. ... God bless."

He was sentenced to death for the brutal slayings of Harvey Gray Watson Jr., 63, his cellmate at Wallens Ridge State Prison in 2009, and Aaron Alexander Cooper, 26, at Red Onion State Prison in 2010. Both men were strangled. Watson was tied up, taunted, beaten and had a sock stuffed in his mouth. Cooper was repeatedly strangled and allowed to catch his breath before he finally died.

Family members of at least one of the victims witnessed the execution from a private viewing area. Authorities keep the identities and number of such witnesses confidential. Of the 110 people executed in Virginia since executions resumed in 1982, he was just the second to die for killing an inmate. Gleason was serving life for a murder in Amherst County in 2007 when he killed Watson and Cooper.

Gleason refused to appeal his death sentences and told lawyers not to oppose his execution. Gleason told The Associated Press that execution was the only way to stop him from killing. In a brief filed with the Virginia Supreme Court last year, the Virginia Attorney General's Office wrote that Gleason was, "an unrepentant murderer, has no regard for human life and will continue to kill." "Killing to him is no different than 'going to the fridge to get a beer' or 'tying a shoe,' " wrote officials, quoting Gleason himself. Gleason, said authorities, "repeatedly made clear that he would continue to kill unless he received a death sentence."

In affirming the death sentences, the Virginia Supreme Court noted that when Gleason pleaded guilty to Cooper's slaying, he claimed he deliberately targeted him as a favor to another inmate to be released soon and who would owe him a favor on the outside. Larry Traylor, spokesman for the Virginia Department of Corrections, said Gleason's only visitor Wednesday was his spiritual adviser.

Death row inmates in Virginia have had the option to choose execution by lethal injection or the electric chair since 1995. Gleason was the seventh to opt for the chair while 79 have died by injection. At 8:55 p.m., Gleason was led into the death chamber surrounded by execution team members who held his heavily tattooed arms. He was quickly strapped into the wooden electric chair at his chest, arms and ankles. He smiled, winked and nodded at times toward his spiritual adviser sitting in the witness area. The adviser, Tim "Bam Bam" Spradling of the Richmond Outreach Center, said he believed Gleason was indicating all was well and he was ready.

After making his last statement, a wide leather strap - that covered his eyes and mouth but with a hole for his nose - was placed over his face and secured to the back of the chair. A brine-soaked sea sponge was attached to his right calf and a metal cap holding another brine-soaked sponge was strapped to the top of his head. Power cables were then connected to the head and leg. A key on the wall was turned to activate the system, and an execution team member watching the chair from a one-way window pressed the execution button.

The first cycle of electricity - approximately 1,800 volts at 7½ amps - lasted 30 seconds followed by 60 seconds at 250 volts at 1½ amps. His body tensed and his skin turned pink when the first cycle began. After a brief pause, a second 90-second cycle was conducted. After five minutes, a physician put a stethoscope to Gleason's chest just below a tattooed skull and failed to detect a heartbeat.

A psychiatric evaluation of Gleason in 2010 found that he had a history of substance abuse, depression and other problems but concluded that he was not suicidal and was competent to stand trial. Gleason was a native of Lowell, Mass., not far from Boston, and was an accomplished tattoo artist in Colonial Heights.

He wasn't a stone-cold killer with a dysfunctional personality to everyone. To Patrick Hoffman, 24, of Colonial Heights, Gleason was an extraordinary tattoo artist, friend and something of a father figure. Hoffman said he had known Gleason since he was a teenager, had some tattoos from him and worked in his second shop, Mom's Tattoo Parlor, from 2006 to 2007. "I knew him as Bobby, a lot of people called him Bobby," he said. "The Bobby Gleason I knew - he was a genuine nice guy, all-around good person," Hoffman said. "He was never, ever aggressive that I ever saw ... and he was a great artist." He added: "I had heard in 2007 that he had gotten involved in a shooting. It was mind-blowing. No one could believe it."

Former lawyers fought an eleventh-hour effort to have Gleason re-evaluated for competency but were given a final turn-down by the U.S. Supreme Court Wednesday. Gov. Bob McDonnell said last week that he would not intervene.

"Robert Gleason got death the way he wanted it," by Michael L. Owens. (Updated: 11:22 am, Fri Jan 18, 2013)

JARRATT, Va. –– Robert C. Gleason Jr. died with fists partially clenched and smoke rising from his body. He was faceless Wednesday night, the throes of death hidden behind a thick, black mask that allowed enough space only for his nose to poke through. Death came on his own terms: He sought execution for a pair of murders in two Southwest Virginia prisons and asked for the electric chair.

There was the customary, last-minute flurry of appeals rejected by the governor and the U.S. Supreme Court. But those weren’t his appeals. Instead, they were filed by a team of capital defense attorneys arguing Gleason’s mental incompetence and hoping for the chance to represent him. And Gleason, like the governor and federal judges, rejected their help to the very end. His last words in the execution chamber at the Greensville Correctional Center in Jarratt, Va., were cryptic. “Well, I hope Percy ain’t going to wet the sponge. Put me on the highway to Jackson and call my Irish buddies. Pog mo thoin. God bless,” he said. The translation of the Irish Gaelic wording is “kiss my a--.”

Death took roughly eight minutes from the time the condemned man entered the chamber. The execution, taking place on the other side of a two-way window, was like a play that began with Gleason taking a few steps into a cinderblock room and ended with someone mumbling a “time of death.” It culminated with someone drawing a blue curtain across the witness room window and a prison official telling the witnesses it was time to leave.

Gleason died violently as more than 1,000 volts of electricity jolted his body in a pair of 90-second cycles. He smiled to the room full of witnesses as soon as he stepped into the execution chamber and winked at his spiritual advisor, who was sitting in the crowd. He gave a thumbs up as he sat in the chair. Gleason wore flip-flops, a blue shirt and dark blue pants with the right pant leg cut off at the knee. A skullcap was placed on his head and a brine-soaked sea sponge was strapped to his right tattoo-covered calf. A pair of cables snaked up along the electric chair to the top of the skullcap and along the ground onto the floor to his calves.

A guard stood with a red phone in his hand that was a direct line to the governor’s office. But there would be no intervention. At 9 p.m., a man with the phone nodded for the executioner to begin. One man turned a key in a wall to activate the system and another man in an adjacent room started the electrocution. Gleason’s body spasmed with each series of jolts, smoke rising from the mask. The jolts were administered at 9:03, and after five long minutes of silence a doctor in a white coat entered from a side room, put a stethoscope to his tattooed chest and then nodded that he was dead. He then pronounced the time of death as 9:08 p.m.

Sitting in another room to view the execution was Kim Strickland, the mother of the last victim, Aaron Alexander Cooper. “May God have mercy on his soul,” she said Monday of her son’s killer. “I have been and will be praying for his family throughout this ordeal.” In a letter sent to her, Gleason described Cooper’s death and noted that he was holding on to the mother’s address. “Everyone will be O.K. if I get the death penalty,” he wrote. Strickland, fearing his reach beyond prison walls, has moved several times since her son died and remains on the run. “A very reliable source told me I was not safe and I have moved four or five times,” she testified during a 2011 sentencing hearing. “I have no sense of home anymore.” Now penniless, she lives out of her car and shelters.

Amy Taylor, the mother of one of Gleason’s children, said she will miss him. “He will always be remembered by those who truly knew him as a very fun, loving, compassionate person who cared more for those he loved than he ever did for himself,” she said. Gleason spent his last two hours with his spiritual advisor, Tim “Bam Bam” Spradling, a former biker buddy who now preaches at a Richmond church. “We talked about how my life went one way and his went in the opposite direction,” Spradling said. In those last hours, Gleason cried for his victims and asked God for forgiveness, he added.

No one seems to know the real reason Gleason demanded execution. In court, he said it was to teach younger relatives that murder comes with severe consequences. Yet, a case worker’s report from 2011 suggests that Gleason had a mental history filled with feelings of paranoia, anxiety and depression, ultimately leading to exhaustion and a need to escape. Life in prison, according to the report, would simply be too intolerable.

Initially, Gleason earned life in prison without parole for shooting to death truck driver Michael Kent Jamerson on May 8, 2007, to cover up the tracks of a methamphetamine ring already eyed by federal investigators. Gleason, during his 2011 sentencing hearing, said they had stopped by a wooded area in Amherst County and he pulled a pistol from Jamerson’s own belt, told him to get right with God, and began shooting. A turkey hunter found Jamerson’s body the next day. A Liberty University student fishing along the bank of the James River, about three miles from the body, found the gun several days later.

Two years later, Gleason ended up in a cell with 63-year-old Harvey Gray Watson Jr. at Wallens Ridge State Prison in Big Stone Gap. Watson was serving a 100-year sentence for killing a man and wounding two others when he fired a shotgun into his neighbor’s Lynchburg home in 1983. The older inmate was mentally impaired and known for such antics as singing nonsensical tunes throughout the night and drinking his own urine. Gleason tired of him after about a week and tied him up, beat and strangled him on May 8, 2009 – the two-year anniversary of Jamerson’s murder. Guards didn’t notice the body in the cell for 15 hours. Soon after that, Gleason threatened to kill again unless given the death penalty.

Then, on July 28, 2010, he strangled convicted carjacker Aaron Alexander Cooper, 26, in the recreation yard of the supermax security Red Onion State Prison near Pound. It was done with ripped apart strips of braided bed sheet threaded through the chain link fence separating the two inmates.

"With execution over, prosecutor free to discuss dealings with Robert Gleason Jr., by Michael L. Owens. (Updated: 6:44 pm, Mon Jan 21, 2013)

Threats and curses are part of the daily grind for Commonwealth's Attorney Ron Elkins. As the man tasked with prosecuting Wise County’s bad guys, he has learned to view angry letters and seething taunts with a grain of salt. But the envelope received in 2010 with the word “BOOM!!!” penciled on the back and “See You In Hell!!!” scripted on the letter inside was much different than all the other mail sent by jail inmates. It was from multiple-murderer Robert C. Gleason Jr., 42, who was executed Wednesday in Virginia’s electric chair. “With him, it was definitely something that worried me,” Elkins said. “I didn’t worry for me as much as I worried for my family.”

Elkins had to remain silent about dealing with Gleason, who was convicted of shooting a man to death and executed for strangling two inmates once in prison – as the case dragged on. With the execution carried out and the case over, however, the prosecutor can talk about the man with a knack for getting personal information about prison guards, potential jurors and victims’ families and then using it to taunt them. “I think he was one of the most intellectual people I’ve been with and one of the most manipulative human beings I’d ever seen in my life,” Elkins said.

Gleason was an award-winning tattoo artist, a member of the biker gang Hell’s Angels and in court said he was a former hit man responsible for several deaths. “I would not be surprised if he were involved with or implicated in other murders,” Elkins said. Tim “Bam Bam” Spradling, a former biker buddy of Gleason’s who has since become a Richmond-area preacher, believes more bodies might lurk in the man’s past. “He was the guy everyone called to take care of problems,” Spradling said in an interview late Wednesday. Spradling was the last person to talk to Gleason before his execution and said they reminisced about old times and talked about forgiveness in the last two hours.

Gleason’s death-penalty case posed a few legal hurdles, mainly because he represented himself in court. He also sought the same thing as Elkins – execution. It was the small things, the prosecutor said, that proved to be time consuming. For example, the prison did not allow Gleason to have any court documents with staples sent to him. And every face-to-face visit came with a pat down by prison guards. “It really complicates things when the opposing counsel is in a maximum-security prison,” Elkins said.

Gleason was serving a life sentence at Wallens Ridge State Prison in Big Stone Gap in 2009, when he beat and strangled a mentally disturbed Harvey Gray Watson Jr., 63, when his antics became irritating. After threatening to kill again unless given the death penalty, Gleason followed through a year later when he strangled inmate Aaron A. Cooper, 26, through an adjoining cage in the recreation yard of the supermax security Red Onion State Prison near Pound.

It was Gleason’s mentality that posed one of the case’s biggest challenges. “Gleason always had a sense of ethics about him that you and I don’t possess but that to him it was very serious,” Elkins said. The rules: never talk about Gleason’s family and don’t say anything that could be perceived as a lie or a trick. Any infraction resulted in threats. “We just made sure we were straight with him and told him what was going on,” Elkins said.

When it was time for Gleason's moment in the death chamber of Greensville Correctional Center in Jarratt, Elkins thought he had to be there. “There is no greater punishment. There is no worse thing you can do to somebody,” the prosecutor said. “It’s an enormous weight to carry around on your shoulders.” So, Elkins watched as Gleason’s body turned pink and convulsed from more than 1,000 volts of electricity. “My first thought is that it was much more humane than what he did to people,” Elkins said.

"Convicted Murderer Robert Gleason, Killer of 2 Fellow Inmates, Wants the Dealth Penalty," by Cory Zurowski. (Monday, August 16, 2010 at 7:00 am)

Robert Gleason Jr. loathed his new cellmate, Harvey Gray Watson Jr. He told officials at Wallens Ridge State Prison in Virginia as much. Gleason also told counselors and correctional officers that if they didn't move Watson, bad shit was going to go down. They didn't listen... For a solid week in the early days of May 2009, the 63-year-old Watson -- serving a 100-year sentence for killing a man and wounding two others with a 10-gauge shotgun in 1983 -- became an obnoxious fuck to Gleason's uneventful, incarcerated existence.

Watson, who suffered from mild mental impairment, spent almost every minute of every day with Gleason locked up in an eight-by-ten-foot cell, singing verses from the song "Dixie" at all hours, hollering expletives and jerking off. During eating hours and rec time, other inmates would egg Watson on to drink his own urine and spoiled milk in exchange for cigarettes. Gleason couldn't take it. Despite his pleas to have Watson shipped off to another cell, prison officials scoffed. Going onto the eighth day of their shared existence, Gleason knew the time had come: "That day I knew I was going to kill him. Wallens Ridge forced my hand."

The witching hour came when bed checks were over and lights were out at the facility. It was sometime past midnight. Gleason tied Watson's hands and arms to his torso using fragments of bed sheets. He also fashioned a gag using a pair of socks. Gleason soon removed the gag and lit a cigarette for Watson. He told him to enjoy it as it would be his last. Watson spit on Gleason's face when the smoke was removed. Gleason responded by hopping on Watson's back, beating him, and ultimately strangling him to death. Gleason covered the corpse with a bed sheet to make it look like Watson was sleeping. Officials wouldn't discover the murdered man's body until almost dinnertime the following day.

In the aftermath of Watson's strangulation death, Gleason -- already serving a life term for killing another man -- told The Associated Press: "I murdered that man [Watson] cold-bloodedly. I planned it, and I'm gonna do it again. Someone needs to stop it. The only way to stop me is to put me on death row." Now, a year and change later, Gleason is still not getting his wish of being introduced to capital punishment granted, so he decided to sending prison officials another reminder.

Late last month at the maximum security Red Onion State Prison -- Gleason's new home -- in southwestern Virginia, 26-year-old inmate Aaron Alexander Cooper was found strangled to death in the recreation yard. According to Wise County Commonwealth's Attorney Ron Elkins, Gleason was at the very least "involved" in the murder. It is more likely, though, the facts will bare out that Cooper died at the hands of Gleason. Authorities believe Cooper was strangled with a towel, piece of clothing or bed sheet that was somehow put through the chain link fence separating each inmate.

In two weeks Gleason is scheduled to be sentenced for murdering Watson last year. Attorney Elkins has said he will wait until that sentencing before he decides what course to take regarding Gleason's involvement in his latest killing.

On May 8, 2007, Robert Charles Gleason, Jr. fatally shot Michael Kent Jamerson to death off of Virginia 130 in westerm Amherst County, Virginia. A turkey hunter found his body in a wooded area. He was shot four times; twice to the head and twice to the body. The murder weapon was found on the banks of the James River by a college student who was fishing there. Gleason was part of a methamphetamine drug ring and believed that Jamerson was going to cooperate with the government against the ring. At trial, Gleason burst out with a string of profanities, denouncing the court and was removed. Shortly thereafter, he told the judge he wanted to just "get this over with today" and pled guilty to the murder.

Two years to the day after the Jamerson murder, Harvey Watson was murdered at Wallens Ridge State Prison. His cellmate, Gleason, was serving a life plus three years sentence for the Jamerson murder and was charged with the "willful, deliberate, and premeditated killing of any person by a prisoner confined in a state or local correctional facility," a capital offense. On December 21, 2010, following an evaluation to confirm his competency, Gleason pled guilty to the murder of Watson in the Circuit Court of Wise County. Gleason confessed under oath, stating that he planned the murder to occur on the two-year anniversary of a previous homicide that he had committed. In 1983, Gleason admitted to binding Watson with torn bed sheets, beating him, taunting him about his impending death, shoving a urine sponge in his face and a sock in his mouth, and finally strangling him with fabric from the sheet. According to Gleason, he concealed the body in his cell for fifteen hours, making excuses for Watson's failure to emerge. Gleason further stated that he planned, once rigor mortis had passed, to dispose of the body in the garbage that was circulated to pick up food trays. Gleason was unsuccessful in disposing of the body before Watson was discovered by prison personnel. Throughout the circuit court proceedings, Gleason consistently repeated that he had no remorse. Rather, knowing that the premeditated murder of an inmate and more than one murder within a three-year period was punishable by the death penalty in Virginia, he commented to the court that he "already had a few other inmates lined up, just in case I didn't get the death penalty, that I was gonna take out." Following Watson's death, Gleason had been moved to solitary confinement in Virginia's "supermax" Red Onion Prison.

On July 28, 2010, Gleason was in a solitary recreation pen that shared a common wire fence with that of Aaron Cooper. Gleason asked Cooper to try on a "religious necklace" that Gleason was making. Gleason proceeded to strangle Cooper through the wire fence, repeatedly choking Cooper "'til he turned purple," waiting "until his color came back, then going back again" until Cooper finally expired. Gleason described himself laughing at the reaction of the other inmates. He then watched and mocked the prison staff attempting to revive Cooper. Cooper was serving a 34 year sentence for carjacking and robbery. Gleason was charged in the capital murder of Cooper for "the willful, deliberate, and premeditated killing of more than one person within a three-year period." On April 22, 2011, Gleason pled guilty to the murder of Cooper. He informed the court that he had deliberately targeted Cooper so as to make a point to the prosecutor and as a favor to another inmate who was to be released soon, so that the inmate would owe Gleason, and Gleason would then have someone outside the prison to do his bidding. After accepting both guilty pleas, the court conducted a multi-day joint sentencing proceeding, considering evidence and argument by counsel and Gleason. The court also reviewed a pre-sentence report, Gleason having waived a post-sentence report. The court fixed Gleason's sentences at death, finding the aggravating factors of both vileness and future dangerousness in both cases beyond a reasonable doubt, and concluding that these factors were not outweighed by mitigating facts.

Virginians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty

Name: Robert C. Gleason DOB: 1970 Race: W Venue: Wise Crime: Murder - Two Counts Inmate Number: 388580 Date Entered: 8-31-11

1 Frank Coppola August 10, 1982 electric chair Muriel Hatchell

2 Linwood Earl Briley October 12, 1984 electric chair John Gallaher

3 James Dyral Briley April 18, 1985 electric chair Judy Barton and Harvey Barton

4 Morris Mason June 25, 1985 electric chair Margaret Hand

5 Michael Marnell Smith July 31, 1986 electric chair Audrey Jean Weiler

6 Richard Lee Whitlley] July 6, 1987 electric chair Phoebe Parsons

7 Earl Clanton, Jr.[2][3] April 14, 1988 electric chair Wilhemina Smith

8 Alton Waye[4][5] August 30, 1989 electric chair Laverne Marshall

9 Richard T. Boggs[6][7] July 19, 1990 electric chair Treeby Shaw

10 Wilbert Lee Evans[8] October 17, 1990 electric chair sheriff deputy William Truesdale

11 Buddy Earl Justus[9] December 13, 1990[1] electric chair Ida Mae Moses

12 Albert Jay Clozza[10][11] July 24, 1991[2] electric chair Patricia Ann Bolton

13 Derick Lynn Peterson August 22, 1991 electric chair Howard Kauffman

14 Roger Keith Coleman[12] May 20, 1992 electric chair Wanda Fay McCoy

15 Edward B. Fitzgerald, Sr.[13][14] July 23, 1992 electric chair Patricia Cubbage

16 Willie Leroy Jones[15] September 11, 1992 electric chair Graham Adkins and Myra Adkins

17 Timothy Dale Bunch[16] December 10, 1992 electric chair Su Cha Thomas

18 Charles Sylvester Stamper[17][18][19] January 19, 1993 electric chair Franklin Cooley, Agnes Hicks, and Stephen Staples

19 Syvasky L. Poyner[20][21] March 18, 1993 electric chair Joyce Baldwin, Louise Paulett, Chestine Brooks, Vicki Ripple, and Carolyn Hedrick

20 Andrew J. Chabrol[22][23] June 17, 1993 electric chair Lisa Harrington

21 Joe Louis Wise, Sr.[24] September 14, 1993 electric chair William Ricketson

22 David Mark Pruett[25][26] December 16, 1993 electric chair Wilma Harvey and Debra McInnis

23 Johnny Watkins, Jr.[27] March 3, 1994 electric chair Betty Barker and Carl Buchanan

24 Timothy Wilson Spencer[28] April 27, 1994 electric chair Susan Tucker, Debbie Davis, Susan Hellams, and Diane Cho

25 Dana Ray Edmonds January 24, 1995 lethal injection John Elliot

26 Willie Lloyd Turner May 26, 1995 lethal injection W. Jack Smith, Jr.

27 Dennis Wayne Stockton September 27, 1995 lethal injection Kenneth Arnde and Ronnie Lee Tate

28 Mickey Wayne Davidson October 19, 1995 lethal injection Doris Davidson, Mamie Clatterbuck, and Tammy Clatterbuck

29 Herman Charles Barnes November 13, 1995 lethal injection Clyde Jenkins and Mohammed Afifi

30 Walter Milton Correll, Jr.[29] January 4, 1996 lethal injection Charles W. Bousman, Jr.

31 Richard Townes, Jr.[30] January 23, 1996 lethal injection Virginia Goebel

32 Joseph John Savino III[31] July 17, 1996 lethal injection Thomas McWalters

33 Ronald B. Bennett[32] November 21, 1996 lethal injection Anne Keller Vaden

34 Gregory Warren Beaver December 4, 1996 lethal injection state trooper Leo Whitt

35 Larry Allen Stout December 10, 1996 lethal injection Jacqueline Kooshian

36 Lem Davis Tuggle, Jr. December 12, 1996 lethal injection Jessie Geneva Havens

37 Ronald Lee Hoke December 16, 1996 lethal injection Virginia Stell

38 Michael Carl George February 6, 1997 lethal injection Alexander Sztanko

39 Coleman Wayne Gray February 26, 1997 lethal injection Richard McClelland

40 Roy Bruce Smith July 17, 1997 lethal injection Manassas police officer John Conner

41 Joseph Roger O'Dell III July 23, 1997 lethal injection Helen Schartner

42 Carlton Jerome Pope August 19, 1997 lethal injection Cynthia Gray

43 Mario Benjamin Murphy September 17, 1997 lethal injection James Radcliff

44 Dawud Majid Mu'Min November 13, 1997 lethal injection Gladys Nopwasky

45 Michael Charles Satcher December 9, 1997 lethal injection Ann Borghesani

46 Thomas H. Beavers, Jr. December 11, 1997 lethal injection Marguerite Lowery

47 Tony Albert Mackall February 10, 1998 lethal injection Mary Elizabeth Dahn

48 Douglas McArthur Buchanan, Jr. March 18, 1998 lethal injection Douglas Buchanan, Sr., Donald Buchanan, J.J. Buchanan, and Geraldine Buchanan

49 Ronald L. Watkins March 25, 1998 lethal injection William McCauley

50 Angel Francisco Breard[33] April 14, 1998 lethal injection Ruth Dickie

51 Dennis Wayne Eaton June 18, 1998 lethal injection state trooper Jerry Hines, Walter Custer, Jr., Ripley Marston, Sr., and Judith MacDonald

52 Danny Lee King July 23, 1998 lethal injection Carolyn Rogers

53 Lance Antonio Chandler, Jr. August 20, 1998 lethal injection Billy Dix

54 Johnile L. DuBois August 31, 1998 lethal injection Philip Council

55 Kenneth Manual Stewart, Jr. September 23, 1998 electric chair Cynthia Stewart and Jonathan Stewart

56 Dwayne Allen Wright October 14, 1998 lethal injection Saba Tekle

57 Ronald Lee Fitzgerald October 21, 1998 lethal injection Coy H. White and Hugh Morrison

58 Kenneth Wilson November 17, 1998 lethal injection Jacqueline Stephens

59 Kevin Wayne Cardwell December 3, 1998 lethal injection Anthony Brown

60 Mark Arlo Sheppard January 20, 1999 lethal injection Richard Rosenbluth and Rebecca Rosenbluth

61 Tony Leslie Fry February 4, 1999 lethal injection Leland A. Jacobs

62 George Adrian Quesinberry, Jr.[34] March 9, 1999 lethal injection Thomas L. Haynes

63 David Lee Fisher March 25, 1999 lethal injection David William Wilkey

64 Carl Hamilton Chichester April 13, 1999 lethal injection Timothy Rigney

65 Arthur Ray Jenkins III April 20, 1999 lethal injection Floyd Jenkins and Lee H. Brinklow

66 Eric Christopher Payne April 28, 1999 lethal injection Ruth Parham and Sally Fazio

67 Ronald Dale Yeatts April 29, 1999 lethal injection Ruby Meeks Dodson

68 Tommy David Strickler July 21, 1999 lethal injection Leann Whitlock

69 Marlon DeWayne Williams August 17, 1999 lethal injection Helen Bedsole

70 Everett Lee Mueller September 16, 1999 lethal injection Charity Powers

71 Jason Matthew Joseph October 19, 1999 lethal injection Jeffrey Anderson

72 Thomas Lee Royal, Jr. November 9, 1999 lethal injection Hampton police officer Kenny Wallace

73 Andre L. Graham December 9, 1999 lethal injection Sheryl Stack, Richard Rosenbluth, and Rebecca Rosenbluth

74 Douglas Christopher Thomas January 10, 2000 lethal injection James Baxter Wiseman and Kathy J. Wiseman

75 Steve Edward Roach January 13, 2000 lethal injection Mary Ann Hughes

76 Lonnie Weeks, Jr. March 16, 2000 lethal injection state trooper Jose M. Cavazos

77 Michael David Clagett July 6, 2000 electric chair Lam Van Son, Wendell G. Parish, Jr., Karen Sue Rounds, and Abdelaziz Gren

78 Russell William Burket August 30, 2000 lethal injection Katherine Tafelski and Ashley Tafelski

79 Derek Rocco Barnabei September 14, 2000 lethal injection Sarah Wisnosky

80 Bobby Lee Ramdass October 10, 2000 lethal injection Mohammed Kayani

81 Christopher Cornelius Goins December 6, 2000 lethal injection Robert Jones, Nicole Jones, David Jones, Daphne Jones, and James Randolph

82 Thomas Wayne Akers March 1, 2001 lethal injection Wesley Brant Smith

83 Christopher James Beck October 18, 2001 lethal injection Florence Marie Marks, David Kaplan, and William Miller

84 James Earl Patterson March 13, 2002 lethal injection Joyce Snead Aldridge

85 Daniel Lee Zirkle April 2, 2002 lethal injection Christina Zirkle and Jessica Shiflett

86 Walter Mickens, Jr. June 12, 2002 lethal injection Timothy Jason Hall

87 Mir Aimal Kasi November 14, 2002 lethal injection Frank Darling and Lansing Bennett

88 Earl Conrad Bramblett April 9, 2003 electric chair Blaine Hodges, Teresa Hodges, Winter Hodges, and Anah Hodges

89 Bobby Wayne Swisher July 22, 2003 lethal injection Dawn McNees Snyder

90 Brian Lee Cherrix March 18, 2004 lethal injection Tessa Van Hart

91 Dennis Mitchell Orbe March 31, 2004 lethal injection Richard Burnett

92 Mark Wesley Bailey July 22, 2004 lethal injection Katherine Bailey and Nathan Bailey

93 James Bryant Hudson August 18, 2004 lethal injection Stanley Cole, Walter Cole, and Patsy Cole

94 James Edward Reid September 9, 2004 lethal injection Annie Mae Lester

95 Dexter Lee Vinson April 27, 2006 lethal injection Angela Felton

96 Brandon Wayne Hedrick July 20, 2006 electric chair Lisa Yvonne Crider

97 Michael William Lenz July 27, 2006 lethal injection inmate Brent H. Parker

98 John Yancey Schmitt November 9, 2006 lethal injection Earl Shelton Dunning

99 Kevin Green May 27, 2008 lethal injection Patricia L. Vaughan

100 Robert Yarbrough June 25, 2008 lethal injection Cyril Hugh Hamby

101 Kent Jermaine Jackson July 10, 2008 lethal injection Beulah Mae Kaiser

102 Christopher Scott Emmett July 24, 2008 lethal injection John Fenton Langley

103 Edward Nathaniel Bell February 19, 2009 lethal injection Winchester police officer Ricky Timbrook

104 John Allen Muhammad November 10, 2009[3] lethal injection Dean Harold Meyers

105 Larry Bill Elliott November 17, 2009 electric chair Dana Thrall and Robert Finch

106 Paul Warner Powell March 18, 2010 electric chair Stacie Reed

107 Darick Walker May 20, 2010 lethal injection Stanley Beale and Clarence Elwood Threat

108 Teresa Lewis September 23, 2010 lethal injection Julian Clifton Lewis and Charles J. Lewis

109 Jerry Terrell Jackson August 18, 2011 lethal injection Ruth Phillips

110 Robert Charles Gleason Jr. January 16, 2013 electric chair Harvey Gray Watson Jr. Aaron Alexander Cooper

Gleason v. Commonwealth, 726 S.E.2d 351 (Va. 2012). (Direct Appeal)

Background: In two separate cases, defendant was convicted on guilty pleas in the Circuit Court, Wise County, John C. Kilgore, J., of two counts of capital murder of prison inmates, and he was sentenced to death in both cases. Defendant waived appeal as of right.

Holdings: On consolidated review, the Supreme Court, Leroy F. Millette, Jr., held that: (1) death sentences were not imposed under influence of passion, prejudice or any other arbitrary factor, and (2) death sentences were not excessive or disproportionate to sentences imposed in other capital murder cases involving killing of inmates or murders committed within period of three years. Affirmed.

Opinion by Justice LEROY F. MILLETTE, JR.

Robert Charles Gleason, Jr., received two death sentences following pleas of guilty to capital murder in the killings of Harvey Grey Watson and Aaron Cooper. Although Gleason has waived his appeals of right, Code § 17.1–313 mandates that we review the death sentences. In this review, we consider whether the sentences were imposed “under the influence of passion, prejudice or any other arbitrary factor” and whether the sentences are “excessive or disproportionate to the penalty imposed in similar cases, considering both the crime and the defendant.” Code § 17.1–313(C).

I. Background

On May 8, 2009, Harvey Watson was murdered at Wallens Ridge State Prison. His cellmate, Robert Gleason, was charged with the “willful, deliberate, and premeditated killing of any person by a prisoner confined in a state or local correctional facility,” a capital offense under Code § 18.2–31(3). On December 21, 2010, following an evaluation to confirm his competency, Gleason pled guilty to the murder of Watson in the Circuit Court of Wise County. Gleason confessed under oath, stating that he planned the murder to occur on the two-year anniversary of a previous homicide that he had committed.

Gleason admitted to binding Watson with torn bed sheets, beating him, taunting him about his impending death, shoving a urine sponge in his face and a sock in his mouth, and finally strangling him with fabric from the sheet. According to Gleason, he concealed the body in his cell for fifteen hours, making excuses for Watson's failure to emerge. Gleason further stated that he planned, once rigor mortis had passed, to dispose of the body in the garbage that was circulated to pick up food trays. Gleason was unsuccessful in disposing of the body before Watson was discovered by prison personnel.

Throughout the circuit court proceedings, Gleason consistently repeated that he had no remorse. Rather, knowing that the premeditated murder of an inmate and more than one murder within a three-year period was punishable by the death penalty in Virginia, he commented to the court that he “already had a few [other] inmates lined up, just in case I didn't get the death penalty, that I was gonna take out.”

Following Watson's death, Gleason had been moved to solitary confinement in Virginia's “supermax” Red Onion Prison. On July 28, 2010, Gleason was in a solitary recreation pen that shared a common wire fence with that of Aaron Cooper. Gleason asked Cooper to try on a “religious necklace” that Gleason was making. Gleason proceeded to strangle Cooper through the wire fence, repeatedly choking Cooper “ ‘til he turned purple,” waiting “until his color came back, then [going] back again” until Cooper finally expired. Gleason described himself laughing at the reaction of the other inmates. He then watched and mocked the prison staff attempting to revive Cooper.

Gleason was charged in the capital murder of Cooper under Code § 18.2–31(8) for “[t]he willful, deliberate, and premeditated killing of more than one person within a three-year period.” On April 22, 2011, Gleason pled guilty to the murder of Cooper. He informed the court that he had deliberately targeted Cooper so as to make a point to the prosecutor and as a favor to another inmate who was to be released soon, so that the inmate would owe Gleason, and Gleason would then have someone outside the prison to do his bidding.

After accepting both guilty pleas, the court conducted a multi-day joint sentencing proceeding, considering evidence and argument by counsel and Gleason. The court also reviewed a pre-sentence report, Gleason having waived a post-sentence report. The court fixed Gleason's sentences at death, finding the aggravating factors of both vileness and future dangerousness in both cases beyond a reasonable doubt, and concluding that these factors were not outweighed by mitigating facts. Although Gleason was found competent to waive appeal and did so, we must proceed with the required statutory review.

II. Statutory Review

A. Passion, Prejudice, or Other Arbitrary Factors

We first consider whether the death sentences were imposed “under the influence of passion, prejudice or any other arbitrary factor.” Code § 17.1–313(C)(1). We find no evidence to suggest that this was the case. Counsel for Gleason have conceded that they cannot point to any evidence in the record that would indicate that the circuit court was influenced by passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor. The circuit court, hearing the case without a jury, was meticulous in ensuring that Gleason was competent, and the record makes clear that Gleason consistently had advice from stand-by counsel throughout the proceedings. The court took great pains to explain to Gleason the procedure, the law, and his rights. Gleason was permitted to change his plea in the Watson case from not guilty to guilty to not guilty, and back again to guilty. The court granted each of Gleason's requests for a continuance, appointed every expert he requested, and granted all accommodations within its power to grant.

The circuit court also explicitly stated that, while Gleason had asked the court to consider a variety of reasons why Gleason should be sentenced to death on either or both charges, “the only things that I am allowed to consider and the only things that I have considered throughout this case, regardless of what testimony has been offered or regardless of what opinions have been given, are the statutory factors that a fact-finder in Virginia [may] appropriate[ly] consider”: whether the Commonwealth has proved vileness or future dangerousness in either of the two cases beyond a reasonable doubt, as well as whether mitigating facts outweigh these proofs. Gleason points to no portion of the record that suggests that the sentences were issued as a result of passion or prejudice, or that they were arbitrary in any way. Our review of the record likewise has revealed no such bias.

B. Proportionality Review

The statutory mandate against excessive or disproportionate sentencing in Code § 17.1–313(C) is not to “ ‘[e]nsure complete symmetry among all death penalty cases,’ ” but rather “ ‘to determine if a sentence of death is aberrant.’ ” Prieto v. Commonwealth, 283 Va. 149, 188–89, 721 S.E.2d 484, 507–08 (2012) (alteration in original) (quoting Porter v. Commonwealth, 276 Va. 203, 267, 661 S.E.2d 415, 448 (2008), cert. denied, 556 U.S. 1189 (2009)). The two crimes share several features relevant to our review. The murders were both clearly premeditated and accomplished by means of ligature strangulation, a very deliberate and personal method of killing. They both involved taunting or torture indicative of a particularly high level of cruelty: Watson was tied up, beaten, taunted, given his last cigarette and then had a urine sponge stuffed in his face, while Cooper was repeatedly strangled and permitted to catch his breath before he was killed.

We are required by Code § 17.1–313(C) to consider not only the crime itself but the defendant. In both instances, Gleason was dispassionate after the killing: Watson's body remained in his cell with him for fifteen hours as he plotted attempts to hide the body, and Gleason mocked officers attempting to revive Cooper. Gleason was very clear to the court that he had “no remorse for it, zero.” Gleason presented witnesses testifying to the fact that, even from prison, he was a danger to both the prison population and the population at large. He has shown from his actions that he is capable of orchestrating a murder in Virginia's most secure prison. He himself stated to the court: “You guys can lock me 24/7, take everything out of my cell.... Sooner or later, I'm gonna be the nice little man, and get out there” and kill again.

In the course of this review, we have considered similar cases for which a death sentence was imposed involving capital murders committed by inmates. See, e.g., Remington v. Commonwealth, 262 Va. 333, 551 S.E.2d 620 (2001), cert. denied, 535 U.S. 1062, 122 S.Ct. 1928, 152 L.Ed.2d 834 (2002), Lenz v. Commonwealth, 261 Va. 451, 544 S.E.2d 299, cert. denied, 534 U.S. 1003, 122 S.Ct. 481, 151 L.Ed.2d 395 (2001), Payne v. Commonwealth, 233 Va. 460, 357 S.E.2d 500, cert. denied, 484 U.S. 933, 108 S.Ct. 308, 98 L.Ed.2d 267 (1987). We have also considered similar cases for which a death sentence was imposed for more than one murder within three years. See, e.g., Andrews v. Commonwealth, 280 Va. 231, 699 S.E.2d 237 (2010), cert. denied, ––– U.S. ––––, 131 S.Ct. 2999, 180 L.Ed.2d 827 (2011) (death penalty vacated on other grounds by our Court); Muhammad v. Commonwealth, 269 Va. 451, 619 S.E.2d 16 (2005), cert. denied, 547 U.S. 1136, 126 S.Ct. 2035, 164 L.Ed.2d 794 (2006); Walker v. Commonwealth, 258 Va. 54, 515 S.E.2d 565 (1999), cert. denied, 528 U.S. 1125, 120 S.Ct. 955, 145 L.Ed.2d 829 (2000). We have additionally reviewed similar cases in which, after a finding of both aggravating factors of future dangerousness and vileness, a death sentence was imposed for a willful, deliberate, and premeditated killing by means of ligature strangulation. See, e.g., Bramblett v. Commonwealth, 257 Va. 263, 513 S.E.2d 400, cert. denied, 528 U.S. 952, 120 S.Ct. 376, 145 L.Ed.2d 293 (1999); Spencer v. Commonwealth, 240 Va. 78, 393 S.E.2d 609 (1990), cert. denied, 498 U.S. 908, 111 S.Ct. 281, 112 L.Ed.2d 235 (1990); Spencer v. Commonwealth, 238 Va. 563, 385 S.E.2d 850 (1989), cert. denied, 493 U.S. 1093, 110 S.Ct. 1171, 107 L.Ed.2d 1073 (1990); Spencer v. Commonwealth, 238 Va. 295, 384 S.E.2d 785 (1989), cert. denied, 493 U.S. 1093, 110 S.Ct. 1171, 107 L.Ed.2d 1073 (1990); Spencer v. Commonwealth, 238 Va. 275, 384 S.E.2d 775 (1989), cert. denied, 493 U.S. 1036, 110 S.Ct. 759, 107 L.Ed.2d 775 (1990); Clanton v. Commonwealth, 223 Va. 41, 286 S.E.2d 172 (1982). Finally, we have reviewed capital murder cases in which life imprisonment was imposed rather than the death penalty. After reviewing these cases and Gleason's actions as admitted to under oath before the circuit court, we are convinced that Gleason's death sentences are neither excessive nor disproportionate.

III. Conclusion

In sum, we determine that the death sentences were not imposed under the influence of passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor and are not excessive or disproportionate. Accordingly, we will affirm the judgments of the circuit court. Record No. 111956— Affirmed. Record No. 111957— Affirmed.

Gleason v. Pearson, Slip Copy, 2013 WL 139478 (W.D.Va. 2013). (Habeas)

GLEN E. CONRAD, Chief Judge.

Robert Charles Gleason, Jr. is scheduled to be executed on January 16, 2013 for murdering Harvey Watson, his cellmate at Wallens Ridge State Prison, and for murdering Aaron Cooper, a fellow inmate at Red Onion State Prison. Gleason has plainly and clearly expressed his desire to forgo any challenges to his death sentences, and he has steadfastly rejected legal assistance to spare his life. Contrary to Gleason's directives, Jonathan Sheldon and Joseph Flood, Gleason's appointed state habeas counsel, commenced proceedings in this court by filing a motion for appointment of counsel.FN1 Citing 18 U.S.C. § 3599 and McFarland v. Scott, 512 U.S. 849 (1994), the movants' initial filing requests an order appointing themselves and another attorney to represent Gleason in any federal habeas corpus proceedings under 28 U.S.C. § 2254. Following oral argument on January 4, 2013, the movants were given the opportunity to submit additional evidence in support of the motion. The movants have now filed a motion to determine competency, in which they request that the court enter a stay of execution, conduct an evidentiary hearing regarding Gleason's competence to waive further review, and appoint them for the purpose of adjudicating the competency issue. The movants have also filed a motion for discovery. For the reasons set forth below, the motions will be denied. FN1. The court will hereinafter refer to Sheldon and Flood as “the movants.”

Background

In affirming Gleason's sentences of death on direct appeal, the Supreme Court of Virginia provided the following summary of Gleason's crimes: On May 8, 2009, Harvey Watson was murdered at Wallens Ridge State Prison. His cellmate, Robert Gleason, was charged with the “willful, deliberate, and premeditated killing of any person by a prisoner confined in a state or local correctional facility,” a capital offense under Code § 18.2–31(3). On December 21, 2010, following an evaluation to confirm his competency, Gleason pled guilty to the murder of Watson in the Circuit Court of Wise County. Gleason confessed under oath, stating that he planned the murder to occur on the two-year anniversary of a previous homicide that he had committed.

Gleason admitted to binding Watson with torn bed sheets, beating him, taunting him about his impending death, shoving a urine sponge in his face and a sock in his mouth, and finally strangling him with fabric from the sheet. According to Gleason, he concealed the body in his cell for fifteen hours, making excuses for Watson's failure to emerge. Gleason further stated that he planned, once rigor mortis had passed, to dispose of the body in the garbage that was circulated to pick up food trays. Gleason was unsuccessful in disposing of the body before Watson was discovered by prison personnel. Throughout the circuit court proceedings, Gleason consistently repeated that he had no remorse. Rather, knowing that the premeditated murder of an inmate and more than one murder within a three-year period was punishable by the death penalty in Virginia, he commented to the court that he “already had a few [other] inmates lined up, just in case I didn't get the death penalty, that I was gonna take out.”

Following Watson's death, Gleason had been moved to solitary confinement in Virginia's “supermax” Red Onion Prison. On July 28, 2010, Gleason was in a solitary recreation pen that shared a common wire fence with that of Aaron Cooper. Gleason asked Cooper to try on a “religious necklace” that Gleason was making. Gleason proceeded to strangle Cooper through the wire fence, repeatedly choking Cooper “til he turned purple,” waiting “until his color came back, then [going] back again” until Cooper finally expired. Gleason described himself laughing at the reaction of the other inmates. He then watched and mocked the prison staff attempting to revive Cooper.

Gleason was charged in the capital murder of Cooper under Code § 18.2–31(8) for “[t]he willful, deliberate, and premeditated killing of more than one person within a three-year period.” On April 22, 2011, Gleason pled guilty to the murder of Cooper. He informed the court that he had deliberately targeted Cooper so as to make a point to the prosecutor and as a favor to another inmate who was to be released soon, so that the inmate would owe Gleason, and Gleason would then have someone outside the prison to do his bidding. Gleason v. Commonwealth, 726 S.E.2d 351, 352–53 (Va.2012).

After accepting Gleason's pleas of guilty to the capital murder charges, the Circuit Court of Wise County conducted a joint, multi-day sentencing hearing. Gleason represented himself at the hearing with the assistance of stand-by counsel. On September 6, 2011, after considering the evidence and argument presented by counsel and Gleason, the Circuit Court sentenced Gleason to death for both murders, finding that the aggravating factors of vileness and future dangerousness had been proven beyond a reasonable doubt.

While his cases were before the Circuit Court, Gleason filed a document expressing his desire to “waive[ ] all right of appeal in all of these cases and specifically and emphatically request[ing] that no one, attorney or otherwise, file any appeal[s] on his behalf in any of these cases.” (Joint Appendix at 244.) FN2 Leigh D. Hagan, Ph.D., the psychologist appointed to evaluate Gleason on the defense's motion prior to sentencing, was also appointed to determine whether Gleason possessed the capacity to waive his right to appeal his death sentences. FN2. The court will hereinafter refer to the joint appendix filed on direct appeal as “J.A.”

On September 19, 2011, the Circuit Court conducted a hearing on the matter. After questioning Gleason and receiving testimony and a written report from Dr. Hagan, the Circuit Court granted Gleason's motion to waive his right to appeal. The Circuit Court found that Gleason was competent to make a decision regarding whether or not to exercise his right to appeal; that he possessed the adequate level of intelligence to make the decision; that he was not suffering from a mental illness that would render him unable to make an informed decision; that he had the capacity to make reasoned choices; and that his decision was made knowingly, voluntarily, and intelligently. (J.A. 1605–06.)

The Circuit Court entered an amended final sentencing order on September 19, 2011. Despite Gleason's waiver of his right to appeal the death sentences, the Virginia Supreme Court was required to review the sentences under Virginia Code § 17.1–313. On June 7, 2012, after briefing and oral argument, the Supreme Court upheld the death sentences, finding that they “were not imposed under the influence of passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor and are not excessive or disproportionate.” Gleason v. Commonwealth, 726 S.E.2d 351, 354 (Va.2012). Gleason did not seek a rehearing or petition the United States Supreme Court for certiorari. After Gleason's death sentences were affirmed on direct appeal, the movants were appointed to represent Gleason during the course of any state habeas proceedings, pursuant to the mandatory appointment provision set forth in Virginia Code § 19.2–163.7. Gleason ultimately forbade the filing of a state habeas petition, and no petition was filed on his behalf.

On October 3, 2012, the movants filed in the Virginia Supreme Court a “motion to establish jurisdiction prior to filing a petition for writ of habeas corpus.” (Docket No. 4–8.) The movants stated that Gleason was refusing to permit the filing of a habeas petition. They requested the Supreme Court to establish which court would have jurisdiction to determine whether Gleason was competent to waive habeas review. The Attorney General of Virginia filed a brief in opposition to the motion, arguing that Gleason had not requested the relief sought, and that the movants were attempting to intervene against Gleason's wishes without standing to do so. The Supreme Court denied the motion in a summary order entered on October 17, 2012.

The Instant Motions

On December 20, 2012, the movants initiated proceedings in this court by filing a motion for appointment of counsel, in which they expressed concerns regarding Gleason's competence. Following the filing of a brief in opposition by the respondent, the movants argued their motion on January 4, 2013. During that proceeding, the court also received argument by Katherine Burnett, the Senior Assistant Attorney General representing the respondent, as well as a statement by Gleason. When given the opportunity to address the court, Gleason plainly and clearly stated that he wants to maintain his current execution date, that he does not want to pursue federal habeas corpus relief, and that he does not want the movants or any other attorney to attempt to pursue such relief on his behalf. Gleason confirmed that he has spoken to family members, friends, and officers about his decisions. Gleason emphasized that he has hurt people, that he deserves the punishment imposed for his crimes, and that there is no valid reason to delay his execution. When questioned by the court regarding what he wants to occur, Gleason responded as follows: “I don't want an attorney. I want to let the January 16th [execution] day go as is.” (Docket No. 14 at 22.)

Following the proceeding, the movants requested that the court delay its ruling on the motion for appointment of counsel, pending the submission of additional evidence regarding Gleason's alleged incompetence. The court ultimately granted the request and gave the movants until 5:00 p.m. on January 9, 2013 to submit any additional evidence in support of the motion for appointment of counsel. Minutes before the deadline set forth in the court's order, the movants filed a motion to determine Gleason's competency to waive proceedings. Shortly after the deadline, the movants filed a memorandum in support of the second motion, along with a number of exhibits. The exhibits include, among other submissions, declarations from the movants and other attorneys; a declaration from Eileen P. Ryan, D.O., a psychiatrist who evaluated Gleason's competency to stand trial in March of 2010 in connection with the first capital murder case; records from Gleason's July 1998 admission to John Umstead Hospital in Butner, North Carolina following an overdose; and prison records indicating that Gleason was placed on “hunger strike protocol” in June of 2012 after missing several consecutive meals.

On January 10, 2013 at 1:46 p.m., the movants filed a motion for discovery. Emphasizing that their motion for appointment of counsel under 18 U.S.C. § 3599 is currently pending, the movants request an order directing Sussex I State Prison to disclose Gleason's medical and psychiatric records, and directing the Attorney General of Virginia to disclose “any and all of its communications” with Gleason. (Docket No. 26 at 1.)

Discussion

Federal courts are courts of limited jurisdiction. “They are not generalized overseers of the state court systems, not even in death penalty cases.” West v. Bell, 242 F.3d 338, 341 (6th Cir.2001). Although death row inmates can invoke the jurisdiction of the federal courts by filing a petition for writ of habeas corpus under § 2254, Gleason has elected not to do so.

Under existing United States Supreme Court precedent, a third party, or “next friend,” may challenge the validity of a death sentence imposed on a capital defendant who has elected to forgo further review only if the third party has standing to do so. See Whitmore v. Arkansas, 495 U.S. 149, 162–64 (1990); Demosthenes v.. Baal, 495 U.S. 731, 734–35 (1990). The “burden is on the ‘next friend’ clearly to establish the propriety of his status and thereby justify the jurisdiction of the court.” Whitmore, 495 U.S. at 164. A prerequisite to “next friend” standing is “a showing by the proposed ‘next friend’ that the real party in interest is unable to litigate his own cause due to mental incapacity, lack of access to court, or other similar disability.” Id. at 165. In attempting to meet this requirement, the “usual explanation” proffered by a party seeking next friend standing is an inmate's mental incompetency. Sanchez–Velasco v. Sec'y of the Dep't of Corr., 287 F.3d 1015, 1029 (11th Cir.2002).

In this case, the movants have not expressly sought to obtain next friend standing. Instead, they seek to be appointed as counsel, to stay Gleason's execution, to obtain discovery, and to have an evidentiary hearing on Gleason's competence, so that they can, apparently, attempt to establish standing to file a petition for writ of habeas corpus on Gleason's behalf. As the respondent has emphasized, however, there is no authority for the process proposed by the movants. Neither 18 U.S.C. § 3599 (requiring the appointment of counsel for an indigent death row inmate who wishes to file a habeas corpus petition), nor McFarland v. Scott, 512 U.S. 849, 859 (1994) (concluding that “a capital defendant may invoke the right to a counseled habeas corpus proceeding by filing a motion requesting the appointment of habeas counsel, and that a district court has jurisdiction to enter a stay of execution where necessary to give effect to that statutory right”), mandate the appointment of counsel or a stay of execution, regardless of an inmate's wishes. See West, 242 F.3d at 341 (holding that “ McFarland applies, at most, to a prisoner's seeking counsel to file a habeas, or, perhaps a qualified next friend seeking time to prepare a habeas petition) (emphasis added). Instead, to intervene against an inmate's wishes, the requirements of Whitmore must be met. Id . In this case, the court is convinced that the movants have failed to establish their entitlement to proceed under this precedent.

The Circuit Court of Wise County considered Gleason's mental capacity on multiple occasions, and was “meticulous” in ensuring that Gleason was competent to stand trial; that he had the ability to knowingly and voluntarily plead guilty to both charges of capital murder; and that he was capable of representing himself at sentencing with the assistance of stand-by counsel. Gleason, 726 S.E.2d at 353. Likewise, following an evidentiary hearing and the submission of an additional competency evaluation by Dr. Hagan, the Circuit Court found that Gleason had the capacity to decide whether or not to exercise his right to appeal, and that Gleason's decision to waive this right was made knowingly, voluntarily, and intelligently.

The Circuit Court's findings, and the ultimate decision that Gleason was competent to waive further challenges to his convictions and death sentences, are factual in nature and are entitled to a presumption of correctness under Demosthenes v. Baal, supra, and 28 U.S.C. § 2254(e)(1). See Demosthenes, 495 U.S. at 735 (concluding that a state court's competency determination is entitled to a presumption of correctness on federal habeas review); 28 U.S.C. § 2254(e)(1) (providing that “[i]n a proceeding instituted by an application for a writ of habeas corpus by a person in custody pursuant to the judgment of a State court, a determination of a factual issue made by a State court shall be presumed to be correct”); see also Daughtry v. Polk, 190 F. App'x 262, 275 (4th Cir.2006) (“Whether a defendant is competent is a question of fact. We also must accord the state court's determination that Daughtry was competent ... a presumption of correctness under 28 U.S.C. § 2254(e)(1).”); Sanchez–Velasco, 287 F.3d at 1030 (“The district court failed to give the state courts' determination that Sanchez–Velasco was mentally competent to decide for himself whether to pursue further challenges to his conviction and death sentence the presumption of correctness it was entitled to under Demosthenes ”): Akers v. Angelone, 147 F.Supp.2d 447, 449 (W.D.Va.2001) (holding that a state court's competency determination was entitled to deference). This presumption of correctness “can be overcome only if the party challenging the inmate's mental competency comes forward with evidence that clearly and convincingly establishes incompetency.” Sanchez–Velasco, 287 F.3d at 1030; see also U.S.C. § 2254(e)(1).

In their 38–page memorandum filed on January 9, 2013, the movants make no specific reference to the presumption of correctness afforded to a state court's competency determination. Instead, relying on a declaration from Dr. Ryan, the movants emphasize that “[a]ny competency determination, by its nature, is temporal,” and that the Circuit Court's most recent competency determination was made over a year ago. (Docket No. 23 at 5, n. 1.) While the court recognizes that this is more time than had elapsed between the state court findings and the filing of the federal habeas corpus petition in Demosthenes, it is not so much time as to eliminate the presumption of correctness to which the Circuit Court's factual findings, and its ultimate competency determination, are entitled. See Sanchez–Velasco, 287 F.3d at 1030–31 (holding that “the district court should have accepted as correct the state court's finding,” made over two years earlier, “that Sanchez–Velasco is mentally competent to decide his legal fate”); Akers, 147 F.Supp.2d at 450–51 (applying the presumption of correctness to the state court's competency determinations, which were made nearly a year before an attorney attempted to file a federal habeas petition on the death row inmate's behalf).

The movants also argue that that there are “serious reasons” to doubt the validity of the Circuit Court's competency findings, and that “[t]his court should therefore conduct proceedings sufficient to determine [Gleason's] competency to assist counsel and waive post-conviction review, including an evidentiary hearing.” (Docket No. 23 at 5.) Having considered the evidence proffered by the movants and the relevant case law, the court is unable to agree. “In the face of a state court determination that the real party in interest inmate is mentally competent, in order to be entitled to a federal evidentiary hearing on the issue[,] a would-be next friend must proffer evidence that does one of two things.” Sanchez–Velasco, 287 F.3d at 1030. Specifically, “[t]he proffered evidence either must clearly and convincingly establish that the state court finding was erroneous when made, or it must show that even though the state court finding was correct when made[,] the mental condition of the inmate has deteriorated to the point that he is no longer mentally competent.” Id. Applying this standard, the court concludes that the movants have failed to proffer sufficient evidence to overcome the presumption of correctness afforded to the Circuit Court's competency findings, and that there is no valid basis for further inquiry into the issue of Gleason's competence.

The Circuit Court's determination that Gleason was competent to waive the right to appeal his sentences of death was based, at least in part, on the testimony and written opinions of Dr. Hagan, who was specifically appointed to evaluate Gleason's capacity in this regard. While the movants now challenge the validity of Dr. Hagan's most recent competency report from August of 2011, the court finds the movants' arguments unpersuasive. Aside from arguing, in a conclusory fashion, that “Dr. Hagan unreasonably relied almost exclusively on Mr. Gleason's self-report to find him competent,” (Docket No. 23 at 17), the movants' only other challenge to the validity of Dr. Hagan's report is that it makes no mention of Gleason's admission to John Umstead Hospital in 1998, following an overdose. Even assuming, however, that Dr. Hagan did not consider these hospital records, the movants have failed to demonstrate that the records would have altered Dr. Hagan's opinion that Gleason was competent to waive further review, or that the Circuit Court's competency determination was based on clear error.FN3 See Demosthenes, 495 U.S. at 736–37 (holding that evidence of a death row inmate's prior suicide attempts did not provide meaningful evidence of incompetency, and that the district court correctly denied a motion for further evidentiary hearing on the inmate's competence to waive his right to proceed); Dennis v. Butko, 378 F.3d 880, 892 (9th Cir.2004) (“[E]vidence of suicidal ideation or attempts to commit suicide in the past is insufficient to demonstrate incompetency.”). FN3. The court must note that the hospital records were among the documents reviewed by Dr. Ryan in March of 2010, when she determined that Gleason was competent to stand trial. (J.A. 1694.)

The movants' January 9, 2013 memorandum also purports to outline “current evidence of [Gleason's] incompetence.” (Docket No. 23 at 26.) This evidence, however, consists solely of declarations from the movants and other attorneys opining that Gleason's mental capacity has declined in more recent months, as well as the prison records indicating that Gleason was placed on hunger strike protocol after missing meals. While the movants have ample experience defending capital cases, they are not mental health experts, and the court is convinced that neither their declarations, nor the prison records, provide credible evidence that Gleason's mental capacity has “deteriorated to the point that he is no longer mentally competent.” Sanchez–Velasco, 287 F.3d at 1030; see also Akers, 147 F.Supp.2d at 451 (dismissing a habeas petition filed by an attorney against the wishes of a death row inmate, where the attorney offered “no credible evidence that [the inmate's] mental condition [had] changed” since the state court's competency findings were made); Smith v. Armontrout, 865 F.2d 1502, 1506 (8th Cir.1988) (holding “that the new allegations of fact made by the next friends, even when supplemented by the three new psychiatric affidavits,” did not warrant a new evidentiary hearing on a death row inmate's competence); Evans v. McCotter, 805 F.3d 1210, 1214 (5th Cir.1986) (holding that an affidavit from a death row inmate's sister, which stated that the inmate's mental condition had worsened, was insufficient to overcome the state court's sanity determination, or otherwise warrant an evidentiary hearing in federal court).

Sheldon's declaration also indicates that he spoke to Gleason by telephone on January 8, 2013. According to the declaration, Sheldon asked Gleason “whether he wanted the execution stopped or whether he wanted to die.” (Docket No. 23–1 at 2.) In response, Gleason noted that he had “never said [he] wanted to die.” ( Id.) While the movants reference Gleason's response in their January 9, 2013 memorandum, they wisely refrain from suggesting that Gleason now wishes to pursue federal habeas relief. Succinctly stated, the fact that a death row inmate does not “want to die” does not mean that he wishes to pursue a legal challenge to his sentence of death or seek to stay his execution. As set forth above, Gleason plainly and clearly stated in court on January 4, 2013 that he wishes to maintain his current execution date, and that he does not want the movants or any other attorney to intervene on his behalf.

Conclusion

In sum, the evidence presented by the movants, either standing alone or when considered in combination with other submissions, does not clearly and convincingly establish that the Circuit Court's competency findings were clearly erroneous. Likewise, the movants have failed to proffer sufficient evidence to establish that Gleason's condition has deteriorated to the point that he is no longer competent to waive further review. Accordingly, “no adequate basis exists for the exercise of federal power” in this matter, Demosthenes, 495 U.S. at 737, and the pending motions must be denied. The Clerk is directed to send certified copies of this memorandum opinion and the accompanying order to Gleason and all counsel of record.