Executed September 25, 2012 06:43 p.m. CDT by Lethal Injection in Texas

30th murderer executed in U.S. in 2012

1307th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

9th murderer executed in Texas in 2012

486th murderer executed in Texas since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(30) |

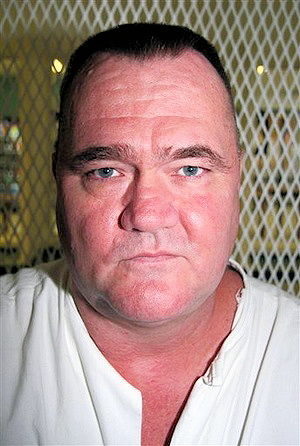

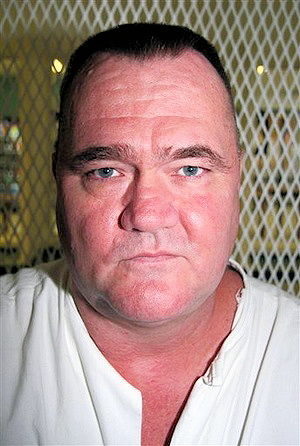

Cleve Foster W / M / 38 - 48 |

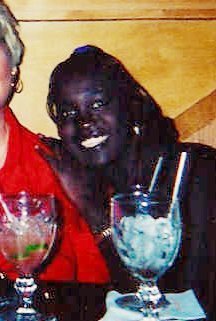

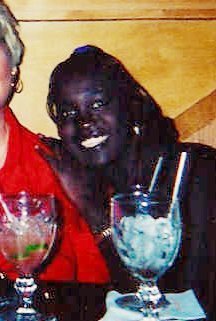

Nyanuer Gatluak "Mary" Pal B / F / 28 |

Citations:

Foster v. State, Not Reported in S.W.3d, 2006 WL 947681 (Tex.Cr.App. 1996). (Direct Appeal)

Foster v. Thaler, 369 Fed.Appx. 598 (5th Cir. 2010). (Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

Texas no longer offers a special "last meal" to condemned inmates. Instead, the inmate is offered the same meal served to the rest of the unit.

Final/Last Words:

“I love you all. I’m looking to leave this place on wings of a homesick angel. Ready to go home to meet my maker. What a friend we have in Jesus, oh my God I lay in awe cause I love you God.”In the seconds before the single lethal dose of pentobarbital began, Foster expressed love to his family and to God. "When I close my eyes, I'll be with the father," he said. "God is everything. He's my life. Tonight I'll be with him." He did not proclaim innocence or admit guilt. He did turn to relatives of his two victims, saying, "I don't know what you're going to be feeling tonight. I pray we'll all meet in heaven."

Internet Sources:

Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Executed Offenders (Foster)

Foster, Cleve

Date of Birth: 10/24/1963

DR#: 999470

Date Received: 3/1/2004

Education: 12 years

Occupation: oil field worker, construction, laborer

Date of Offense: 02/14/2002

County of Offense: Tarrant

Native County: Henderson County, KY

Race: White

Gender: Male

Hair Color: Black

Eye Color: Blue

Height: 5' 10"

Weight: 260

Prior Prison Record: None.

Summary of incident: On 2/14/2002, in Tarrant County, Texas, Foster and co-defendant Ward sexually assaulted and shot a 28 year old black female, resulting in her death. Foster and Ward then moved the body of the victim to a ditch where it was discovered by workers who were laying pipe.

Co-Defendants: Ward, Shelton Aaron

Monday, September 24, 2012

Media advisory: Cleve Foster scheduled for execution

AUSTIN – Pursuant to a court order by Criminal District Court No. 1 in Tarrant County, Cleve Foster is scheduled for execution after 6 p.m. on September 25, 2012. On February 12, 2004, a Tarrant County jury found Foster guilty of the capital murder of Nyanuer “Mary” Pal.

FACTS OF THE CRIME

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit described the murder of Ms. Pal as follows:

On February 13, 2002, Cleve Foster and Sheldon Ward met Nyanuer “Mary” Pal at Fat Albert’s, a Fort Worth bar where all three were regular customers. According to the bartender, Pal interacted primarily with Ward until the bar closed at 2:00 a.m. She then walked to the parking lot with Ward where they talked for a few minutes. Afterwards, Pal left in her car, which was followed closely by Foster and Ward driving in Foster’s truck.

Approximately eight hours later, Pal’s nude body was discovered in a ditch far off a road in Tarrant County. She had been shot in the head. A wadded-up piece of bloody duct tape lay next to her body. Her unlocked car was later found in the parking lot of the apartment complex where she lived.

The police investigation focused on Foster and Ward once police learned that they had been with Pal that night. On February 21, 2002, police searched the motel room shared by Foster and Ward. Only Foster was present. He directed the police to a dresser drawer that contained a gun Ward had purchased from a pawn shop in August 2001.

Later that day, Foster voluntarily went to the police department to give a statement and to provide a DNA sample. In his statement, Foster first denied Pal had been inside his truck. However, he then admitted that she may have leaned inside. Finally, he admitted that “they” went cruising, but that “they” brought Pal back to her vehicle at Fat Albert’s. Police also obtained a DNA sample from Ward sometime on the night of February 21, 2002.

On March 22, 2002, Foster gave another written statement to police in which he claimed: (1) he and Ward followed Pal to her apartment after meeting her at Fat Albert’s; (2) Pal voluntarily went with them to their motel room in his truck; and (3) after taking sleeping pills and drinking beer, Foster fell asleep watching television while Ward and Pal kissed.

In addition to statements, physical evidence also linked Foster and Ward to the offense. DNA tests established that bodily fluids found in Pal’s body contained DNA from both Ward and Foster. DNA testing also revealed that Pal’s blood and tissue were on the gun recovered during the motel room search. In addition, a police detective and medical examiner testified that Pal was not shot where her body was found because there was no blood splatter in the area. Since the soles of her feet indicated that she had not walked to the location where her body was found, the detective testified that he was “very comfortable” with stating that two people carried Pal’s body to that location. In support of his testimony, the detective noted that the raised-arm position of Pal’s body suggested she may have been carried by her feet and hands. In addition, the detective noted that Pal was five-seven and 130 pounds and Ward is only five-six and 140 pounds, while Foster is six feet tall and around 225 pounds.

PRIOR CRIMINAL HISTORY

Under Texas law, the rules of evidence prevent certain prior criminal acts from being presented to a jury during the guilt-innocence phase of the trial. However, once a defendant is found guilty, jurors are presented information about the defendant’s prior criminal conduct during the second phase of the trial – which is when they determine the defendant’s punishment. During the penalty phase of Foster’s trial, jurors learned that Foster was convicted of robbery in 1984. Jurors were also informed about a statement Foster made to a Fort Worth Police Department detective describing the defendant and Ward’s involvement in the 2001 murder of Rachel Urnosky.

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

On June 6, 2002, a Tarrant County grand jury indicted Foster for the offense of capital murder.

On February 12, 2004, a Tarrant County jury convicted Foster of capital murder. After the jury recommended capital punishment, the court sentenced Foster to death by lethal injection.

On April 12, 2006, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the conviction and sentence.

On January 8, 2007, the U.S. Supreme Court denied a petition for writ of certiorari.

On March 21, 2007, the high court rejected Foster’s application for state habeas relief.

On October 29, 2007, the U.S. Supreme Court denied his petition for writ of certiorari.

On December 2, 2008 The federal district court denied his application for writ of habeas corpus

On March 15, 2010, the U.S. Court of Appeals affirmed the denial of habes corpus.

On October 4, 2010, the trial court set Foster’s execution for January 11, 2011.

On December 13, 2010, the U.S. Supreme Court again denied a petition for writ of certiorari.

On December 21, 2010, Foster filed a petition for clemency with the Board of Pardons and Paroles.

On December 22, 2010, Foster filed a subsequent application seeking a state writ of habeas corpus.

On December 30, 2010, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals dismissed the application.

On January 7, 2011, the Board of Pardons and Paroles denied Foster’s clemency petition.

On January 11, 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court stayed Foster’s execution.

On January 18, 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court again rejected Foster’s petition for writ of certiorari.

On January 29, 2011, the Tarrant County trial court set Foster’s execution date for April 5, 2011.

On February 22, 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court denied the original petition for writ of habeas corpus.

On March 16, 2011, Foster filed a petition with the Board of Pardons and Paroles for clemency.

On March 29, 2011, Foster filed a petition for declaratory judgment and temporary restraining order.

On April 1, 2011, the petition was denied by the trial court after a hearing.

On April 1, 2011, sought a stay of execution to the U.S. Supreme Court.

On April 4, 2011, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals denied Foster’s request for emergency relief.

On April 5, 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court granted Foster a temporary stay of execution.

On April 5, 2011, Foster filed his petition for a rehearing with the U.S. Supreme Court.

On April 27, 2011, the Travis County district court rejected Foster’s second request injunction.

On May 31, 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court lifted its hold on Foster’s execution.

On June 17, 2011, the Tarrant County trial court set Foster’s execution date for Sept. 20, 2011.

On September 2, 2011, Foster filed a second subsequent state habeas application.

On September 12, 2011, the Court of Criminal Appeals dismissed Foster’s subsequent application.

On September 16, 2011, Foster filed a fifth petition for certiorari with the U.S. Supreme Court.

On September 20, 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court granted a stay of execution.

On March 26, 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court denied Foster’s fifth petition for certiorari.

On June 1, 2012, Foster filed a motion in the federal district court for relief from its judgment.

On June 14, 2012, the Tarrant County trial court set Foster’s execution date for September 25, 2012.

On August 13, 2012, the federal district court denied Foster’s motion for relief from its judgment.

On Sept. 17, 2012, Foster filed a petition for certiorari and motion for stay of execution.

On Sept. 21, 2012, The United States Court of Appeals denied the motion for a stay of execution.

On Sept. 23, 2012, Foster filed a motion for stay of execution in the U.S. Supreme Court.

On Sept. 25, 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court denied the motion for stay of execution.

Texas Execution Information Center by David Carson.

Cleve Foster, 48, was executed by lethal injection on 25 September 2012 in Huntsville, Texas for the rape and murder of a 28-year-old woman.

On the evening of 13 February 2002, Foster, then 38, and Sheldon Ward, 22, met Nyanuer "Mary" Pal, 28, at Fat Albert's, a Fort Worth bar where all three were regular customers. Pal danced with Ward and interacted primarily with him until the bar closed at 2:00 a.m. She then walked to the parking lot with him and talked for a few minutes. She then left in her car. Foster and Ward were seen following Pal closely in Foster's truck. According to the bartender, they were "right on her bumper".

At about 6:00 a.m., some workers who were laying pipe in a remote area of Tarrant county discovered Pal's nude body in a ditch. She had been shot in the head. A wadded-up, bloody piece of duct tape was next to her body. Pal's unlocked car was found in the parking lot of her apartment complex.

Having learned that Pal was last seen with Foster and Ward, police searched their motel room on 21 February. Only Foster was present at the time of the search. He directed the police to a dresser drawer that contained a gun Ward had purchased from a pawn shop in August 2001. The police also found various items - including three pairs of shoes, gloves, a hatchet, and a knife - soaking in cleaning fluid in a cooler in the back of Foster's truck.

Later that day, Foster voluntarily went to the police department to give a statement and a DNA sample. At first, he denied that Pal had been inside his truck. He then admitted that she may have leaned inside it. Finally, he admitted that he, Ward, and Pal went on a drive, but that he and Ward returned her to her vehicle at Fat Albert's afterward.

Police also obtained a DNA sample from Ward on 21 February. DNA tests established that the victim's vagina and anus contained semen from Foster and Ward. DNA testing also showed that Pal's blood and tissue were on the gun taken from the motel room.

On 22 March, Foster gave another written statement to police. In this account, he stated that he and Ward followed Pal to her apartment after she left Fat Albert's, but claimed that she voluntarily went with them in his truck to their motel room. Foster stated that after taking sleeping pills and drinking beer, he fell asleep watching television while Ward and Pal were kissing. At one point, he awoke to find Pal performing oral sex on him. He tried to stay awake "to enjoy it", but kept falling asleep. Foster stated that the next thing he remembered was Ward telling him he was going to take Pal home.

At Foster's trial, a police detective and the medical examiner testified that there was no blood splatter in the area where her body was found, indicating that she was shot in another location. The soles of her feet indicated that she had not walked to the location where her body was found, but had been carried. The detective testified that the position of Pal's body suggested that she may have been carried by one person holding her hands and another holding her feet. The detective also pointed out that Ward was 5-foot-6 and weighed 140 pounds, the victim was 5-foot-7 and weighed 130 pounds, and Foster was 6 feet tall and weighed 225 pounds, implying Ward could not have carried her by himself.

Under Texas law, a defendant can be found guilty of capital murder for participating in the crime, regardless of whether he or she personally caused the victim's death.

Foster had a prior conviction for robbery in 1984. He and Ward were also suspects in the rape and murder of Rachel Urnosky, a 22-year-old Fort Worth woman who was shot to death in her bed in her apartment on 18 December 2001. She was murdered with the same gun used to kill Pal. Foster told police he and Ward were at her apartment, but they left after she refused to have sex with them.

Shortly before Urnosky's murder, Foster, an army recruiter, was denied re-enlistment for giving alcohol to and having sex with underage potential recruits.

"Texas puts to death man who received three stays of execution," by By Corrie MacLaggan and Terry Baynes (Reuters Tue Sep 25, 2012 10:32pm EDT)Texas executed a man on Tuesday who had received three stays of execution from the U.S. Supreme Court because of questions about how forcefully his lawyers defended him. Cleve Foster, 48, was convicted with an accomplice in the 2002 murder and rape of Nyanuer "Mary" Pal, whose naked body was found in a ditch, according to a report by the Texas Attorney General's office.

Foster had asked the U.S. high court for a fourth stay of execution but it was denied on Tuesday. He was pronounced dead at 6:43 p.m. local time (2343 GMT) at the state penitentiary in Huntsville, Texas criminal justice spokesman Jason Clark said. The U.S. Supreme Court a year ago granted a temporary stay of execution just 2 1/2 hours before Foster was to be put to death by injection. It was the third stay from the high court for Foster, who also was granted delays in January and April 2011. Tuesday's request for a fourth stay was referred by Justice Antonin Scalia to the full court but just three of the nine justices -- Elena Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg -- said they would favor another stay.

Foster's accomplice in the murder, Shelton Ward, died of brain cancer on death row in 2010. Foster maintained in his trial that Ward acted alone and that contact between him and the victim was consensual.

The two men and Pal were regulars at Fat Albert's bar in Fort Worth when, the night before Valentine's Day in 2002, bartenders said Pal walked out with them, according to the report. Pal left in her car and the men followed closely behind in Foster's truck. Eight hours later, Pal's body was found with a gunshot wound to the head and wadded-up duct tape nearby, according to the report.

Foster is the 30th person executed in the United States this year and the ninth in Texas. In his last statement, Foster sent his love to his family and friends. "I love you, I pray one day we will all meet in heaven ...," Foster said. "Ready to go home to meet my maker." Texas has executed more than four times as many people as any other state since the death penalty was reinstated in the United States in 1976, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

"Ex-Army recruiter executed after three previous stays," by Cody Stark. (September 26, 2012)

HUNTSVILLE — A former Army recruiter who had three previous execution dates postponed by the United States Supreme Court was put to death Tuesday for the 2002 shooting death of a Fort Worth woman. Cleve Foster, 48, was pronounced dead at 6:43 p.m., 25 minutes after the lethal dose began. He acknowledged one by one his family and friends who were there to witness and talked about going “home.” “I love you all,” Foster said. “I’m looking to leave this place on wings of a homesick angel. Ready to go home to meet my maker. What a friend we have in Jesus, oh my God I lay in awe cause I love you God.”

The high court stopped Foster from being executed in January, April and September of last year for the murder of 30-year-old Mary Pal on Valentine’s Day 2002. His attorney’s argued Foster was innocent of the murder and had received inadequate legal help at his trial and early in the appeals process. But hours before his execution was carried out Tuesday, the court declined to stop the lethal injection.

Foster and a companion, Sheldon Ward, were sentenced to die for killing Pal, a Sudanese immigrant who was seen talking with the men at a Fort Worth bar hours before her body was found in a ditch off a Tarrant County road. She had been shot in the head.

Pal’s uncle, Lul Duop, said he thought America was the best county in the world when he came over from war-torn Sudan in 1992. He was happy to have Pal come live with him and his wife, but they could not escape danger. “It has been a surprise that we run from the war and come to different kind of war were an individual targets a victim for (a reason) we don’t know,” Duop said. “... We are sorry for watching Mr. Cleve Foster die, but the justice is done.”

A gun in the motel room where Foster and Ward lived was identified as the murder weapon and was matched to an earlier fatal shooting of 22-year-old Rachel Urnosky at her Fort Worth apartment. Foster and Ward were charged but never tried. Urnosky’s father, Terry Urnosky, said that it was difficult making the trip to Huntsville the three previous times for Foster’s execution dates. He said it was like “picking a scab” on an emotional wound and allowing it not to heal. He and his wife, along with Pal’s family, were hoping for an apology from Foster, but it did not come. “I feel (lethal injection) was way too easy, but it is what it is,” Terry Urnosky said. “Now we have an opportunity — both families — to heal. Justice was served — Mary’s, my daughter’s death — made right.”

Foster blamed Pal’s death on Ward, one of his recruits who became a close friend. Prosecutors said evidence showed Foster actively participated in Pal’s killing, offered no credible explanations, lied and gave contradictory stories about his sexual activities with her. The two were convicted separately, Ward as the triggerman and Foster under Texas’ law of parties, which makes participants equally culpable. Pal’s blood and tissue were found on the weapon and DNA evidence showed both men had sex with her.

At his trial, prosecutors presented evidence Pal wasn’t shot where she was found; that Ward alone couldn’t have carried her body to where it was dumped; and that since he and Foster were nearly inseparable and DNA showed both had sex with her, it was clear Foster was involved. A Tarrant County jury agreed, and both received the death sentence. Ward died in 2010 of cancer while on death row.

Foster grew up in Henderson, Ky., and spent nearly two decades in the Army. Records showed court martial proceedings were started against the sergeant first class and he was denied re-enlistment after allegations he gave alcohol to underage students as a recruiter in Fort Worth and had sex with an underage potential recruit. He’d been a civilian only a short time when the slayings occurred.

"Texas executes ex-Army recruiter after 3 reprieves," by His attorneys argued he was innocent of the 2002 slaying of Nyaneur Pal, a 30-year-old immigrant from Sudan. They also said he had deficient legal help at his trial and in early stages of his appeals and argued his case deserved a closer look.

Foster, 48, also was charged but never tried for the rape-slaying a few months earlier of another woman in Fort Worth, Rachel Urnosky.

In the seconds before the single lethal dose of pentobarbital began, Foster expressed love to his family and to God.

"When I close my eyes, I'll be with the father," he said. "God is everything. He's my life. Tonight I'll be with him."

He did not proclaim innocence or admit guilt. He did turn to relatives of his two victims, saying, "I don't know what you're going to be feeling tonight. I pray we'll all meet in heaven."

As the drugs began taking effect and while he was repeatedly saying he loved his family, he began snoring, then he stopped breathing.

Three of the nine Supreme Court justices — Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor — would have stopped the punishment, the court indicated in its brief ruling.

Last year — in January, April and September — the justices did intervene and halted his execution, once only moments before he could have been led to the death chamber.

"It's offensive to us the frivolous appeals that were thrown up at the Supreme Court last minute," said Terry Urnosky, whose 22-year-old daughter's death was blamed on Foster and a partner, Sheldon Ward. "One stay after another, just delaying the closure our families sought."

Urnosky, his wife, and Pal's uncle and aunt stood a few feet away from Foster and watched the execution through a window.

"It's like ripping off a deep scab each time, preventing the wound from being able to start healing," Urnosky said. "Now the wound can start closing."

Maurie Levin, a University of Texas law professor representing Foster, argued the Supreme Court needed to block it again in light of their ruling earlier this year in an Arizona case that said an inmate who received poor legal assistance should have his case reviewed.

Foster and Ward were sentenced to die for killing Pal, who was known as Mary Pal and was seen talking with the men at a Fort Worth bar hours before her body was found in a ditch off a Tarrant County road.

"I am as certain of Foster's guilt as I can be without having seen him do it," Ben Leonard, who prosecuted Foster in 2004, said last week.

A gun in the motel room where Foster and Ward lived was identified as the murder weapon and was matched to Rachel Urnosky's fatal shooting at her apartment.

"It wasn't the violent death that both Mary and my daughter experienced," Urnosky's father said. "I feel it was way too easy, but it is what it is."

Foster blamed Pal's slaying on Ward, one of his recruits who became a close friend. Prosecutors said evidence showed Foster actively participated in her death, offered no credible explanations, lied and gave contradictory stories about his sexual activities with her.

The two were convicted separately, Ward as the triggerman and Foster under Texas' law of parties, which makes participants equally culpable. Pal's blood and tissue were found on the weapon and DNA evidence showed both men had sex with her.

At his trial, prosecutors presented evidence Pal wasn't shot where she was found; that Ward alone couldn't have carried her body to where it was dumped; and that since he and Foster were nearly inseparable and DNA showed both had sex with her, it was clear Foster was involved. A Tarrant County jury agreed, and both received the death sentence. Ward died in 2010 of cancer while on death row.

Foster grew up in Henderson, Ky., and spent nearly two decades in the Army. Records showed court martial proceedings were started against the sergeant first class and he was denied re-enlistment after allegations he gave alcohol to underage students as a recruiter in Fort Worth and had sex with an underage potential recruit. He'd been a civilian only a short time when the slayings occurred.

"Cleve Foster Execution: Texas Inmate Says He Didn't Do It," by Michael Graczyk. (09/25/12 10:41 PM ET)

HUNTSVILLE, Texas — A former Army recruiter failed to win a fourth reprieve from the U.S. Supreme Court and was executed Tuesday evening in Texas for participating in the shooting death of a woman he and a buddy met 10 years ago at a bar.

Cleve Foster was pronounced dead at 6:43 p.m. CDT, 25 minutes after his lethal injection began and two hours after the high court refused to postpone his punishment. Three times last year the justices stopped his scheduled punishment, once when he was moments from being led to the death chamber.

His attorneys argued he was innocent of the 2002 slaying of Nyaneur Pal, a 30-year-old immigrant from Sudan. They also said he had deficient legal help at his trial and in early stages of his appeals and argued his case deserved a closer look.

Foster, 48, also was charged but never tried for the rape-slaying a few months earlier of another woman in Fort Worth, Rachel Urnosky.

In the seconds before the single lethal dose of pentobarbital began, Foster expressed love to his family and to God.

"When I close my eyes, I'll be with the father," he said. "God is everything. He's my life. Tonight I'll be with him."

He did not proclaim innocence or admit guilt. He did turn to relatives of his two victims, saying, "I don't know what you're going to be feeling tonight. I pray we'll all meet in heaven."

As the drugs began taking effect and while he was repeatedly saying he loved his family, he began snoring, then he stopped breathing.

Three of the nine Supreme Court justices – Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor – would have stopped the punishment, the court indicated in its brief ruling.

Last year – in January, April and September – the justices did intervene and halted his execution, once only moments before he could have been led to the death chamber.

"It's offensive to us the frivolous appeals that were thrown up at the Supreme Court last minute," said Terry Urnosky, whose 22-year-old daughter's death was blamed on Foster and a partner, Sheldon Ward. "One stay after another, just delaying the closure our families sought."

Urnosky, his wife, and Pal's uncle and aunt stood a few feet away from Foster and watched the execution through a window.

"It's like ripping off a deep scab each time, preventing the wound from being able to start healing," Urnosky said. "Now the wound can start closing."

Maurie Levin, a University of Texas law professor representing Foster, argued the Supreme Court needed to block it again in light of their ruling earlier this year in an Arizona case that said an inmate who received poor legal assistance should have his case reviewed.

Foster and Ward were sentenced to die for killing Pal, who was known as Mary Pal and was seen talking with the men at a Fort Worth bar hours before her body was found in a ditch off a Tarrant County road.

"I am as certain of Foster's guilt as I can be without having seen him do it," Ben Leonard, who prosecuted Foster in 2004, said last week.

A gun in the motel room where Foster and Ward lived was identified as the murder weapon and was matched to Rachel Urnosky's fatal shooting at her apartment.

"It wasn't the violent death that both Mary and my daughter experienced," Urnosky's father said. "I feel it was way too easy, but it is what it is."

Foster blamed Pal's slaying on Ward, one of his recruits who became a close friend. Prosecutors said evidence showed Foster actively participated in her death, offered no credible explanations, lied and gave contradictory stories about his sexual activities with her.

The two were convicted separately, Ward as the triggerman and Foster under Texas' law of parties, which makes participants equally culpable. Pal's blood and tissue were found on the weapon and DNA evidence showed both men had sex with her.

At his trial, prosecutors presented evidence Pal wasn't shot where she was found; that Ward alone couldn't have carried her body to where it was dumped; and that since he and Foster were nearly inseparable and DNA showed both had sex with her, it was clear Foster was involved. A Tarrant County jury agreed, and both received the death sentence. Ward died in 2010 of cancer while on death row.

Foster grew up in Henderson, Ky., and spent nearly two decades in the Army. Records showed court martial proceedings were started against the sergeant first class and he was denied re-enlistment after allegations he gave alcohol to underage students as a recruiter in Fort Worth and had sex with an underage potential recruit. He'd been a civilian only a short time when the slayings occurred.

Mary Pal was a native of Sudan and lived with her aunt and uncle in Fort Worth. She worked at River Crest Country Club. On February 13, 2002, Cleve Foster and Sheldon Ward met Nyanuer "Mary" Pal at Fat Albert's, a Fort Worth bar where all three were regular customers. According to the bartender, Pal interacted primarily with Ward until the bar closed at 2:00 a.m. She then walked to the parking lot with Ward where they talked for a few minutes. Afterwards, Pal left in her car, which was followed closely by Foster and Ward driving in Foster's truck. Approximately eight hours later, Pal's nude body was discovered in a ditch far off a road in Tarrant County. She had been shot in the head. A wadded-up piece of bloody duct tape lay next to her body. Her unlocked car was later found in the parking lot of the apartment complex where she lived.

The police investigation focused on Foster and Ward once police learned that they had been with Pal that night. On February 21, 2002, police searched the motel room shared by Foster and Ward. Only Foster was present. He directed the police to a dresser drawer that contained a gun Ward had purchased from a pawn shop in August 2001. Later that day, Foster voluntarily went to the police department to give a statement and to provide a DNA sample. In his statement, Foster first denied Pal had been inside his truck. However, he then admitted that she may have leaned inside. Finally, he admitted that "they" went cruising, but that "they" brought Pal back to her vehicle at Fat Albert's. Police also obtained a DNA sample from Ward sometime on the night of February 21, 2002.

In the early morning hours of February 22, 2002, Ward called a friend to ask if he could stay with him. Ward told the friend over the phone that he was in trouble because he killed someone. The friend arrived at the motel around 2:00 or 2:30 a.m. to pick up Ward. While in the truck, Ward told his friend that he followed a girl home from a bar, forced her into a truck at gunpoint, took her out to the country, raped her, and shot her. Ward did not mention Foster. The friend stopped the truck at a store and got the police to arrest Ward. Ward then told police that he had been drinking heavily and using cocaine the night of the offense. He claimed that he and Pal arranged to meet after Fat Albert's closed. Ward also told the police that he drove alone to Pal's apartment in Foster's truck to pick up Pal, and that he and Pal had consensual vaginal and anal sex on the front seat of Foster's truck before they drove back to the motel room where Foster was "pretty much passed out" on the bed. Ward claimed that he and Pal had consensual vaginal sex again in the motel room before they left to drive around. Ward recalled standing over Pal's body lying on the ground with a gunshot wound to her head and a gun in his hand. Ward claimed not to remember firing the gun. He told police that he stripped her body and dumped her clothes in a dumpster. Ward explained that he left a note in the motel apologizing to Foster for involving him. Ward also stated that he told his friend a few hours earlier that he had sex with a girl and killed her.

On March 22, 2002, Foster gave another written statement to police in which he claimed: (1) he and Ward followed Pal to her apartment after meeting her at Fat Albert's; (2) Pal voluntarily went with them to their motel room in his truck; (3) after taking sleeping pills and drinking beer, Foster fell asleep watching television while Ward and Pal kissed; and (4) Foster awoke to Pal performing oral sex on him. In addition to Foster's and Ward's statements, physical evidence also linked the two to the offense. DNA tests established that semen found in Pal's vagina contained Foster's DNA, and semen found in Pal's anus contained Ward's DNA. Ward may also have been a minor contributor to the semen found in Pal's vagina. DNA testing also revealed that Pal's blood and tissue were on the gun recovered during the motel room search. In addition, a police detective and medical examiner testified that Pal was not shot where her body was found because there was no blood splatter in the area. Since the soles of her feet indicated that she had not walked to the location where her body was found, the detective testified that he was "very comfortable" with stating that two people carried Pal's body to that location.

In support of his testimony, the detective noted that the raised-arm position of Pal's body suggested she may have been carried by her feet and hands. In addition, the detective noted that Pal was five-seven and 130 pounds and Ward is only five-six and 140 pounds, while Foster is six feet tall and around 225 pounds.

In February 2004, Foster was convicted of the rape and capital murder of Pal. Based on the necessary jury findings during the punishment phase, the trial court sentenced Foster to death. Sheldon Ward was also sentenced to death for Mary Pal's murder but he died of a brain tumor in prison in May 2009. The gun that was used as the murder weapon was also identified as the gun used in December 2001 to kill Rachel Urnosky, 22, at her apartment in Fort Worth. Both men were charged in Rachel's murder, but never tried. Foster told police they were both at her apartment but they left after she refused to have sex with them.

When she did not report for work at Buckle, a clothing store at a local shopping mall, her manager called police. They found the door to her apartment open and Rachel was found shot to death in her bed. Rachel was a magna cum laude graduate from Texas Tech and an officer with the Baptist Student Mission and spent her spring breaks on mission trips. She had recently gotten engaged.

Rachel's father Terry Urnosky said his wife and other three daughters were just taking life one day at a time, hoping some day they'll find new hope and the strength to continue. "She was just so cruelly and so quickly taken away it has just left a void that it can be a real struggle just to put one foot in front of the other. Her whole life she just wanted the best for people, to do anything she could possibly do to make their life a success, she was a blessing everywhere she went and she'll be so missed, so sorely missed by all of us."

The US Supreme Court granted a stay of execution to Cleve Foster in April 2011, just a few hours before he was supposed to face his punishment for the murder of Mary Pal. The court granted the stay based on claims that Foster's attorneys were ineffective. This was the second time Foster received a stay on the day of execution. Rachel Urnosky's family had traveled to Huntsville from Lubbock. "I just want it to be over," said Rachel's mother, Pam. "This is astounding to me. The irony is that my daughter didn't get such consideration. I have been so upset. Sickened. We buried her four days before Christmas. I have not done as much good as she did in her short life." She also said, "It's not about revenge," she said. "To us, it is about justice. I'm not his judge, but I know what he did, and they both had a part in it, and it happened not only once, but twice. I want him to admit he did it. Admit his guilt." "It's like our hearts just dropped to the floor," Terry Urnosky said. "The thing that hurts so much is the unfairness of it. They gave my daughter no stay of execution. In this particular case, when justice is carried out, it will be a vindication of my daughter's life. We just hope justice will be served quickly."

Foster v. State, Not Reported in S.W.3d, 2006 WL 947681 (Tex.Cr.App. 2006) (Direct Appeal)

Background: Defendant was convicted in the Criminal District Court No. 1, Tarrant County, of capital murder, and was sentenced to death. Appeal was automatic.

Holdings: The Court of Criminal Appeals, Hervey, J., held that:

(1) evidence was legally and factually sufficient to support conviction;

(2) evidence was sufficient to support penalty-phase jury's finding as to future dangerousness;

(3) evidence was sufficient to support penalty-phase jury's finding as to anti-parties special issue;

(4) warrant affidavit contained sufficient facts to establish probable cause for issuance of search warrant for defendant's motel room;

(5) defendant was not in custody for Miranda purposes at time of his tape-recorded statements to police; and

(6) prosecutor did not commit misconduct during closing arguments. Affirmed. HERVEY, J., delivered the opinion of the Court in which KELLER, P .J., MEYERS, PRICE, JOHNSON, KEASLER, HOLCOMB and COCHRAN, JJ., joined.

In February 2004, a jury convicted appellant of capital murder. Tex. Pen.Code § 19.03(a). Pursuant to the jury's answers to the special issues set forth in Texas Code of Criminal Procedure Article 37.071, sections 2(b) and 2(e), the trial court sentenced appellant to death. Art. 37.071, § 2(g). FN1 Direct appeal to this Court is automatic. Art. 37.071, § 2(h). Appellant raises eighteen points of error, many of which are challenges to the legal and factual sufficiency of the evidence. A brief summary of the facts is helpful to address these points of error. We affirm.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

The evidence shows that appellant and Sheldon Ward were close friends and were regulars at a bar named Fat Albert's located in Fort Worth. On the night of February 13, 2002, appellant and Ward were at Fat Albert's when Nyanuer “Mary” Pal, who was also a regular at Fat Albert's, arrived there at around 9:00 or 10:00 p.m. The bartender testified that the three socialized and that toward closing time Ward and Mary engaged in what the bartender called suggestive “dirty dancing.” The bartender testified that Ward had the most interaction with Mary during the evening and that at times he, but not appellant, behaved inappropriately towards her. When the bar closed at 2:00 a.m., appellant, Ward and Mary walked out together. They talked in the parking lot for a few minutes. Mary left in her car followed closely by appellant and Ward in appellant's truck, which appellant was driving. The bartender testified that appellant's truck was right on Mary's bumper, which the bartender thought was unusual. FN2 Approximately eight hours later at around 10:00 a.m., Mary's nude body was discovered in a ditch “quite a ways off the road.” Mary had been shot in the head, and there was a wadded up piece of bloody duct tape next to her body. In the early morning hours of February 15th, Mary's unlocked car, with her cell phone sitting on the front seat, was found in the parking lot of the apartment complex where she lived.

FN2. The bartender testified that there was something unusual about how appellant followed Mary out of the parking lot because one “couldn't put anything between the two bumpers.”

Q. [PROSECUTION]: You seemed to indicate that there was something unusual about the way in which [appellant] and his passenger, [Ward], followed Mary. And perhaps I missed it on my first go around. What did you find that was so unusual? You said something about almost having a wreck?

A. [BARTENDER]: Well, you couldn't have put anything between the two bumpers. Going across this road, there's an intersection, you know, that's cut out so that you can go west. There's a light there. You can't go nowhere. There's no traffic. So it was just odd that she would be going into the road and they would be right on her bumper. And it was just odd. It was odd for them to be together. It was odd for that to be happening.

Subsequent DNA testing established that semen containing appellant's DNA was found inside Mary's vagina and semen containing Ward's DNA was found insider her anus. Ward could not be excluded as a minor contributor of semen found inside Mary's vagina.

Q. [PROSECUTION]: Okay. In looking at the vaginal swab, I take it you did the same testing on that?

A. [DNA EXPERT]: I did.

Q. Can you tell the jury what the results were?

A. The profile obtained from the sperm fraction from the vaginal swab was a mixture of a major male contributor and at least one minor contributor. The major contributor, the profile was the same as [appellant]. And the minor contributor, I could not exclude [Ward].

Within a week of Mary's murder, the police investigation had focused on appellant and Ward primarily because the police learned that they were seen following Mary out of the Fat Albert's parking lot. On the evening of February 21st, the police arrived at a motel where appellant and Ward shared a room (room 117) and spoke to appellant. Ward was not there. The police found various items soaking in a cleaning fluid in a cooler in the back of appellant's truck. These items consisted of three pairs of shoes, bungee cords, black gloves, a bicycle pump, a hatchet, a sheathed knife, two slingshots, a trailer hitch, coat hangers, a brown strap, a bleach bottle, and a liquid detergent bottle. The State's DNA expert testified at trial that items soaked in cleaning fluids containing bleach could make DNA recovery almost impossible. Appellant also directed the police to a dresser drawer in the motel room that contained a gun that Ward had purchased from a pawn shop in August 2001. DNA testing established that the blood and tissue on the gun was Mary's. The police also found bloody clothes in Ward's car. The blood on these clothes was Mary's.

Appellant went to the homicide office on February 21st to provide a DNA sample. Appellant was not under arrest at this time.FN3 Appellant spoke to Detective McCaskill at the homicide office. McCaskill testified that appellant made several inconsistent statements during the February 21st interview. Appellant initially denied that Mary had been inside his truck, he later stated that she may have leaned inside it, and he ultimately stated that “they” went cruising but that “they” brought Mary back to her vehicle at Fat Albert's. McCaskill testified that he did not believe this latter statement about dropping Mary off at her vehicle at Fat Albert's after “they” went cruising because Mary's vehicle was found outside her apartment. Appellant never admitted to having vaginal sex with Mary during four separate interviews with McCaskill .FN4

FN3. Appellant was arrested for this offense in March 2002 after the DNA results came back.

FN4. In a March 22, 2002, written statement to the police, appellant claimed that Mary performed oral sex on him at the motel room. This written statement, however, was not admitted into evidence at the guilt phase of trial. It was admitted into evidence at the punishment phase. Appellant claimed in this statement that he and Ward followed Mary to her apartment complex from where she voluntarily went with them to the motel. Appellant stated:

I laid down and started watching T.V. [Ward] and [Mary] were over there kissing and making out on the bed. I wake up and I go to sleep. The next thing I remember that she is giving me a blow job. I'm doing everything I can to wake up. Because if I'm going to get fucked I want to enjoy it. I'd fall asleep and I wake up the same shit. The next thing I remember him telling me that he was going to take her home.

The police also obtained DNA samples from Ward, apparently some time on the night of February 21st. The next day, Ward decided to move from the motel room that he shared with appellant. Duane Thomas testified, as a rebuttal witness for the prosecution, that he was an acquaintance of Ward's and that Ward called him in the early morning hours of February 22nd asking if he could stay with Thomas. Thomas testified that Ward told him over the telephone that he was in trouble because he had killed someone. Ward and appellant were at the motel room when Thomas arrived there at about 2:00 or 2:30 a.m. on February 22nd to pick up Ward. Thomas testified that he waited in his truck and saw appellant help Ward gather his bags but that Ward took them out to Thomas' truck by himself. After they left, Ward told Thomas that he followed a girl home from a bar, forced her into a truck at gunpoint, took her out to the country, raped her and blew her brains out. Ward did not mention to his friend Thomas that appellant was involved in the offense or anything else that would explain the presence of appellant's DNA inside Mary's vagina.

Thomas eventually stopped at a store and “[got] the police” who arrested Ward. Detective Cheryl Johnson testified that Ward gave an audiotaped statement to the police at 7:30 a.m. on February 22nd. In this statement, Ward told the police a somewhat different story than the one he told his friend Thomas a few hours before. Ward told the police that he was drinking heavily and using cocaine on the night of the offense. He stated that he and Mary made arrangements to meet up after Fat Albert's closed. According to Ward, after Fat Albert's closed, he and appellant went back to their motel room where appellant “pretty much passed out” on the bed. Ward drove alone to Mary's apartment complex in appellant's truck and picked Mary up.FN5 Ward claimed that he and Mary had consensual vaginal and anal sex on the front seat of appellant's truck, and that they drove to the motel room where they had consensual vaginal sex. Ward and Mary left the motel and drove around “a little bit.” Ward next recalled standing over Mary's body lying on the ground with a gunshot wound to her head and the gun in his hand. Ward did not remember firing the gun. Ward stripped Mary's body and left. He said that he dumped Mary's clothes in a dumpster the location of which he could not recall. He stated that he put his bloody clothes in his car at the motel. Ward also stated that just before he moved out of the motel room on February 22nd, he left appellant a letter FN6 apologizing to him for involving him. Ward also stated that he had told Thomas a few hours before that he had sex with a girl and killed her.

FN5. Appellant told McCaskill during the February 21st interview that Ward had not driven his truck for more than two weeks. However, the murder occurred only one week prior to this date.

FN6. Ward's audiotaped statement (Defense Exhibit 3) was played to the jury during the guilt phase of trial. Ward's letter to appellant was not introduced at trial.

Detective McCaskill testified that Mary's nude body was found “quite a ways off the road” in a ditch. He testified that Mary's body did not appear to have been in the location where it was found for “more than a few hours.”

Q. [PROSECUTION]: Can you tell the jury the condition of this body that was found?

A. [MCCASKILL]: Yes, sir. She was nude. She was-she had what appeared to be a gunshot wound to the head. She had long braided hair. She did not appear to have been there for a long time. There was not a degree of deterioration or decompensation [sic] or anything that I could notice. She didn't appear to have been there probably more than a few hours.

McCaskill testified that there “was no forensic evidence found in or on [appellant's] truck that linked the victim [sic] to this crime .” He opined that it was very unlikely that “a person could shoot and kill another” and “not get something on them, and then take a body that is bloody from one location to another and dump it and not get anything on their clothing or anything in their truck.” He also testified that it was possible that only one person could have carried Mary's body where it was found even though he was “very comfortable” with saying that two people carried her body to the location where it was found.

McCaskill believed that Mary's body was carried to the location where it was found after Mary was shot elsewhere because there was no “blood splatter around the area.”

Q. [PROSECUTION]: And being at the crime scene and examining the crime scene photographs, do you have an opinion as to whether or not [Mary] was shot as she lay in that location [where she was found]?

A. [MCCASKILL]: No, sir. I don't believe that she was.

Q. Can you tell the jury why?

A. Well, we typically would have seen a lot of blood splatter around the area. Because it was what appeared to be a close contact wound, there's what's referred to as blow back. A shot that's fired from a centerfire handgun, a large-caliber handgun, has quite a bit of actual muzzle blast, and it creates-the blast itself causes quite a bit of damage which will cause flesh and bodily fluids to come back out. And we would normally see that on the area, possibly the ground around there or on her body itself. And we did not see that in this case.

The medical examiner also testified that there would have been “a profuse amount of blood” associated with Mary's gunshot wound.

Q. [PROSECUTION]: If [Mary] had been found in the place she was shot, in other words, lying on-if she had been lying on some dry leaves, dead leaves, and had also been shot there, what kind of matter or blood would you expect to find around these wounds?

A. [MEDICAL EXAMINER]: This was, in fact, a rather devastating gunshot wound, and the bullet had passed through the brain stem and blood vessels, so there would be a profuse amount of blood there, I would suspect.

Q. And would the path of the bullet have also expelled brain matter in the area or do you have an opinion about that?

A. Yes. Certainly there's a possibility but one can't say with certainty, but frequently, with an explosive gunshot wound and increasing pressures and bleeding, the blood and the brain matter frequently oozes out both from the entry gunshot wound as well as the exit gunshot wound.

The evidence also showed that Mary was five-seven and 130 pounds. Ward is roughly five-six and 140 pounds. Appellant is a big man, is roughly six feet tall and approximately 225 pounds. McCaskill testified that he believed it possible “that two people might have carried [Mary's body] out there.”

Q. [PROSECUTION]: Let me take you back to State's 24. Is there anything of significance to you about how her body was lying?

A. [MCCASKILL]: Yes, sir.

Q. Tell us what that is?

A. In particular, I considered her right arm here, and the way that she was lying with that arm up, I considered the possibility that two people might have carried her out there. One person carrying her feet, the other person carrying the arms, and they might have just dropped her in that position.

McCaskill also believed it significant that a Whataburger cup in good condition was found “no more than 30 to 40 yards” from Mary's body because appellant had stated in one of his statements to the police “that he would on occasion frequent Whataburger.”

Q. [PROSECUTION]: And if you can use a laser pointer to see if you see anything of significance to you.

A. [MCCASKILL]: Yes, sir. It's a Whataburger cup laying right there.

Q. What's significant about that?

A. Well, at the time it was taken, it appeared to me that that cup had not been out there very long. It was not weathered or faded as if it had been out there for a long time. I believed that it was at least a possibility that it could have been dropped by one of the people or the person or persons responsible. I had to at least consider that.

Q. Well, in light of the fact that [appellant], in his audiotaped statement, told you that he would on occasion frequent Whataburger?

A. Yes, sir. At the time that photograph was taken, I wasn't aware of that, but it became, I believe, important later.

Q. Do you think it's important now?

A. Yes, I do.

Q. Why is that?

A. Because of what we just talked about. They frequented Whataburger and a Whataburger cup was discarded near the body. It appeared not to have been there very long.

McCaskill also testified that appellant and Ward had a unique relationship and that appellant was kind of a mentor to Ward.

Q. [PROSECUTION]: Are you aware of the unique relationship that [appellant] shared with [Ward]?

A. [MCCASKILL]: Yes, sir.

Q. He recruited him into the Army?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Kind of a mentor to him?

A. I believe so, yes.

[DEFENSE]: Your Honor, I'm going to object to leading.

[THE COURT]: Sustained.

McCaskill also testified that Ward and appellant had been roommates in at least three different places and that they did “practically everything together.”

Q. [PROSECUTION]: Was there anything of significance to you in the relationship between [appellant] and Ward and all the different places they lived, and all the different things they've done, and that they were seen together with Mary that night and seen leaving, following her and yet [appellant] is going to admit that he was cruising with her with [Ward] in the truck as well? Anything of significance about that to you?

A. [MCCASKILL]: Yes, sir. Only to that they seemed to me that they did practically everything together.

The bartender testified that she could not think of a time when she saw appellant without Ward.

Q. [PROSECUTION]: Did you ever see one without the other?

A. [BARTENDER]: I cannot think of a time when I saw just one of them.

The bartender also testified that appellant and Ward were in Fat Albert's again on Thursday, February 14th, after Mary had been murdered.

Q. [PROSECUTION]: What about [appellant] and [Ward], did you ever see them again at Fat Albert's?

A. [THE BARTENDER]: Yes, I showed up there on Thursday to Fat Alberts and they were present.

Q. And when you say Thursday, are you meaning Valentine's Day?

A. Valentine's Day.

Q. The day after you had last seen [Mary]?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Or I guess actually the same day early morning hours?

A. Yes, sir.

SUFFICIENCY OF THE EVIDENCE

In points of error one, four, and seven, appellant complains of the trial court's failure to grant his first motion for directed verdict made at the close of the prosecution's case-in-chief on the murder, aggravated sexual assault and kidnapping elements of the offense.FN7 In points of error two, three, five, six, eight and nine, he complains that the evidence is legally and factually insufficient to prove these elements. In evaluating the legal sufficiency of the evidence, we view the evidence in the light most favorable to the verdict and then determine whether any rational trier of fact could have found the essential elements of the crime beyond a reasonable doubt. See Jackson v. Virginia, 443 U.S. 307, 316, 99 S.Ct. 2781, 61 L.Ed.2d 560, (1979). In a factual-sufficiency review, we view all of the evidence in a neutral light, and we will set aside the verdict if the evidence supporting it is too weak to support a finding of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, or, after weighing all of the evidence in support of and contrary to the verdict, the contrary evidence is strong enough that the beyond-a-reasonable-doubt standard could not have been met. See Zuniga v. State, 144 S.W.3d 477, 484–85 (Tex.Cr.App.2004).

FN7. Appellant argues for the first time on appeal that we should not consider any evidence, which would include Thomas' testimony, presented after the trial court denied this motion for instructed verdict. We have, however, held that the denial of an instructed verdict motion is a legal sufficiency challenge requiring a consideration of all the evidence. See Madden v. State, 799 S.W.2d 683, 686 (Tex.Cr.App.1990). We, therefore, decline appellant's invitation not to consider any evidence presented after the denial of appellant's motion for instructed verdict made at the close of the prosecution's case-in-chief.

A person commits the offense of capital murder if he “intentionally or knowingly causes the death of an individual” FN8 and “the person intentionally commits the murder in the course of committing or attempting to commit kidnapping, ... [or] ... aggravated sexual assault ...” Tex. Pen.Code § 19 .03(a)(2). Viewed in the light most favorable to the jury's verdict, the evidence supports a finding that, during the eight hours from when Fat Albert's closed and Mary's body was discovered, Mary was abducted from her apartment complex, sexually assaulted, murdered, and her body was moved to the location where it was found. A jury could rationally find that appellant and Ward abducted Mary from her apartment complex and sexually assaulted her. The presence of appellant's DNA in Mary's vagina, the unusual manner in which appellant followed Mary out of Fat Albert's parking lot, and Ward's statement to Thomas that Mary was forced into appellant's truck support these findings.

FN8. Tex. Pen.Code § 19.02(b)(1); see also Tex. Pen.Code § 19.03(a).

With regard to the murder, there is the evidence of appellant's and Ward's “unique relationship” and the evidence that they did “practically everything together.” There is also McCaskill's testimony that he was “very comfortable” with saying that two people were involved in moving Mary's body to the location where it was found. Additionally, appellant made several inconsistent statements to the police, particularly regarding cruising with Mary and Ward, when he initially stated she had not been in his truck, and the assertion that they returned Mary to her car at Fat Albert's when her car was found at her apartment and the bartender testified that appellant and Ward followed Mary from Fat Albert's. A jury could also infer appellant's consciousness of guilt from the evidence regarding the items in the back of appellant's truck soaking in bleach, which would make DNA analysis almost impossible. Finally, there is appellant's failure to admit to having had vaginal sex with Mary in light of the DNA evidence establishing the presence of appellant's DNA inside Mary's vagina.

On this record, a jury could rationally infer appellant's involvement in Mary's abduction, sexual assault, murder, and the disposal of her body. We, therefore, decide that the evidence is legally sufficient to support appellant's conviction.

Viewed even in a neutral light, the evidence is also factually sufficient to support the jury's verdict. The evidence discussed in our legal sufficiency review is not too weak to support a finding of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. See Zuniga, 144 S.W.3d at 484 (question to be answered in a factual-sufficiency review is: “Considering all of the evidence in a neutral light, was a jury rationally justified in finding guilt beyond a reasonable doubt?”).

We also cannot conclude that the evidence contrary to the verdict is so strong that the beyond-a-reasonable-doubt standard could not have been met. We initially note that the absence of other forensic evidence connecting appellant to Mary's murder does not constitute contrary evidence. The contrary evidence in this record primarily consists of appellant's denials and portions of Ward's somewhat conflicting statements to Thomas and to Detective Cheryl Johnson taking sole responsibility for the offense. But even under a factual-sufficiency analysis, an appellate court must still afford “due deference” to a jury's determinations, and a jury could rationally conclude that the truth was “sprinkled throughout” these statements which, considered with the other evidence outlined above, rationally establishes appellant's guilt. See Johnson v. State, 23 S.W.3d 1, 9 (Tex.Cr.App.2000) (factual-sufficiency review requires reviewing court to afford “due deference” to jury's determinations); see also Zuniga, 144 S.W.3d at 483 (factual-sufficiency standard contains various safeguards “to ensure that reviewing courts [are] deferential to the fact-finder”). In addition, the contrary evidence actually presented to the jury at the guilt phase at trial provides no innocent explanation about how appellant's DNA came to be inside Mary's vagina. Points of error one through nine are overruled.

In point of error ten, appellant claims that the evidence is legally and factually insufficient to support the jury's affirmative answers to special issues one (future dangerousness) and two (anti-parties).FN9 For special issues one and two, we apply the Jackson v. Virginia standard in determining whether the evidence is legally sufficient to support each finding. See Alldridge v. State, 850 S.W.2d 471, 487 (Tex.Cr.App.1991) cert. denied, 510 U.S. 831, 510 U.S. 831, 114 S.Ct. 101, 126 L.Ed.2d 68 (1993). We do not conduct a factual sufficiency review of the future-dangerousness special issue. McGinn v. State, 961 S.W.2d 161,169 (Tex.Cr.App.1998). However, we do conduct a factual sufficiency review of the anti-parties special issue under the Zuniga v. State standard.FN10

FN9. The anti-parties special issue required the jury to find “whether the defendant actually caused the death of the deceased or did not actually cause the death of the deceased but intended to kill the deceased or another or anticipated that a human life would be taken.” Article 37.071, § 2(b)(2).

FN10. See also Valle v. State, 109 S.W.3d 500, 504 (Tex.Cr.App.2003) (finding that the anti-parties special issue is amenable to both factual and legal sufficiency review).

We first address the future-dangerousness special issue. At the punishment phase, appellant's ex-wife testified that appellant became verbally and physically abusive when he found out that she was pregnant. She testified that appellant on several occasions hit her head against the wall during arguments, that appellant once tried to shove her out of the car while they were driving, and that appellant assaulted her in front of their son.

The prosecution presented evidence that appellant was involved in a robbery in 1984 during which appellant placed a knife to the victim's neck and that appellant participated in a murder that occurred in 2001 at the Canyons apartment complex in Fort Worth. The victim, Rachel Urnosky, was found laying on her bed with a gunshot wound to the head. The police recovered a bullet from Urnosky's pillow, which came from the gun seized from the appellant's motel room on February 21, 2002. The appellant admitted being in Urnosky's apartment with Ward for a sexual tryst, but claimed that they left when Urnosky asked them to leave.

Dr. David Self interviewed the appellant and reviewed the police files regarding Mary and Urnosky, and concluded that the appellant had a high risk for future acts of violence. Dr. Self opined that the appellant's high risk for future violence would be particularly true under the circumstances of a life sentence with no parole eligibility for forty years because the appellant would have nothing to lose by engaging in acts of violence. On this record, a jury could rationally have found that there is a probability that appellant would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society.

With regard to the anti-parties special issue, we have held that the anti-parties special issue is relevant when the jury is instructed under the law of parties. See Valle, 109 S.W.3d at 504. The record shows that appellant met Ward when he recruited Ward into the army and acted as Ward's mentor. Appellant elaborates on their relationship in his March 22, 2002, statement (see footnote 4):

In early December of last year, Sheldon let me know he wanted to know what it felt like to kill somebody. You know, he was really pissed off at Tara for taking his daughter away. That just added fuel to the fire, I reckon. Somewhere around the first week or so in December we met at Fat Alberts like we do normally. It was a custom for us to go there at least two or three times a week. He said he had that itch. He was ready to go do something. He was ready to go out and find out what it was like to take somebody's life. We went cruising around town for a while. I didn't know he had a gun, but sometimes he would have it on him and not say anything about it. We went to different apartment complexes just kind of cruising around because I figured if we cruised around, he would just lose the urge. I told him, I'm going to cruise over to the Canyons where I used to live because it was a cool place, and I wanted to see if any of my friends were still there.... I went to Fort Hood the next morning and came back about five days later. We were at the house on North Ridge and Sheldon said, I got something to show you. We were in his room and he showed me a newspaper clipping that was about a girl that had been shot, and he told me that he had his first one. He seemed happily nervous.

Appellant knew what Ward was capable of, and was with Ward the night of Urnosky's murder and the night of Mary's murder. Appellant and Ward shared a motel room and were hanging out at their usual spot, Fat Albert's, the night they met Mary. Appellant and Ward left the bar in appellant's truck following Mary. Appellant directed police to the drawer where the gun, that was linked to Mary's death, was found. The police found shoes, bungee cords and other materials soaking in cleaning fluid inside an ice chest in appellant's truck. Ward's DNA was found on the anal and vaginal swabs and appellant's DNA was found on the vaginal swab. The evidence supports a finding that appellant and Ward acted together in their endeavors or that, at least, the appellant should have anticipated Ward's conduct in shooting Mary after they sexually assaulted her. We cannot conclude that the jury's affirmative answer to the anti-parties special issue is irrational or clearly wrong and unjust. Appellant's tenth point of error is overruled.

ADMISSION OF EVIDENCE

Appellant complains in his eleventh point of error that the trial court erred in overruling his motion to suppress evidence seized pursuant to search warrants. Appellant argues that the affidavits did not establish probable cause to support the issuance of the warrants. A magistrate's decision to issue a search warrant is reviewed under a deferential standard of review. Swearingen v. State, 143 S.W.3d 808, 810–11 (Tex.Cr.App.2004); see also, Illinois v. Gates, 462 U.S. 213, 234–37, 103 S.Ct. 2317, 76 L.Ed.2d 527 (1983). The Fourth Amendment requires no more than a substantial basis for concluding that a search would uncover evidence of wrongdoing. Id. Appellant argues that even after granting the magistrate the requisite deference, it is clear from the four corners of the affidavit that it failed to contain sufficient facts to justify the issuance of a warrant.

In reviewing the affidavit, it is clear that appellant and Ward were the last people seen with Mary at Fat Albert's. Appellant and Ward followed Mary's car when they left Fat Albert's in appellant's truck. Early the next morning Mary was discovered dead. Three witnesses positively identified Ward and the appellant in a photospread. One witness provided police with a telephone number for appellant, which was traced to a motel room in appellant's name. This same witness said he played pool with appellant, Ward, and the victim that night, and that Ward stated he was going to take “Mary” home with him and alluded that he was going to have sex with her. Outside the motel room was the white pick-up truck, which Lemlin had already identified as the one driven by appellant that evening. Given this information, we find that the magistrate had a substantial basis for concluding that a search would uncover evidence of wrongdoing and that the affidavit contained sufficient facts to support the issuance of the warrant. The trial court did not err in denying appellant's motion to suppress. Appellant's eleventh point of error is overruled.

Appellant complains in his twelfth point of error that the trial court erred in overruling defense counsel's motion to suppress appellant's audio-taped statement. Appellant argues that Detective McCaskill FN11 failed to obtain any waiver from appellant before obtaining his statement. Appellant claims that the statement fails to comply with Article 38.22, § 3(a), which requires various procedural safeguards as conditions precedent to the admission of statements made as a result of custodial interrogation. The State argues that Article 38.21, § 3(a), does not apply because appellant was not in custody when he gave the statement.

FN11. Appellant's brief lists Detective Hardy as the detective who interviewed appellant. Detective Hardy was present during the interview, however, Detective McCaskill is the detective who issued the Miranda Warnings and who testified during the pretrial hearing regarding the motion to suppress and during the punishment phase when the audiotape was played for the jury. Therefore, Detective McCaskill will be referred to instead of Detective Hardy.

A trial judge is the sole trier of fact at a suppression hearing and thus evaluates witness testimony and credibility. We give great deference to the trial court's determination of historical facts while reviewing the court's application of the law de novo. Torres v. State, 182 S.W.3d 899, 902 (Tex.Cr.App.2005). We must view the evidence in the light most favorable to the trial court's ruling when the trial court does not file any findings of fact. Id. When no such findings of fact were made, we will assume that the trial court made implicit findings of fact that support its ruling, as long as the findings are supported by the record. Id.

During the pre-trial hearing on appellant's motion to suppress the audio-tape, Detective McCaskill testified in regard to appellant's interview:

Q. Where did you talk to him at the homicide office?

A. In an interview room that was located off a hallway. I didn't speak to him in the open office.

Q: Can you describe for the judge what this interview room looks like?

A: Well, it's about—without the benefit of a tape measure, it's probably about ten by ten, and there's just a desk, and then there's two chairs on either side of the desk.

Q: When you were speaking to Mr. Foster, was he handcuffed, belly-chained, have leg irons on him, or anything like that?

A: No, sir.

Q: Was he allowed to get a drink of water if he'd wanted one?

A: Yes, absolutely.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Q: Did he ever—was he allowed to go use the rest room if he wanted to?

A: If he needed to, absolutely.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Q: And when you sat down to speak to Mr. Foster in that interview room, did you Mirandize him?

A: Yes, I did.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Q: Approximately how much time did you spend talking to Mr. Foster—defendant Foster at that time, on this occasion?

A: We started at about 7:14 p.m., and we would have finished at approximately ten o'clock, or 2200, roughly. I didn't document the exact ending time but probably a little over three hours.

Q: And during that time, was the defendant under arrest?

A: No.

Q: Was he free to leave?

A: Yes.

Q: Did he ever ask to leave?

A: No, sir.

Q: When you got through talking to him, what happened? What did y'all end up doing?

A: One of the uniformed patrol officers drove him back to the Great Western Inn.

The record supports a finding that appellant was not in custody when he gave the statement. See Dowthitt v. State, 931 S.W.2d 244, 254 (Tex.Crim.App.1996). Appellant's twelfth point is overruled.

JURY ARGUMENT

In points of error thirteen through sixteen, appellant complains of improper jury argument. Permissible jury argument generally falls within four areas: (1) summations of the law; (2) reasonable deductions from the evidence; (3) responses to the defendant's argument; or (4) pleas for law enforcement. Dinkins v. State, 894 S.W.2d 330, 357 (Tex.Cr.App.1995), cert. denied, 516 U.S. 832, 116 S.Ct. 106, 133 L.Ed.2d 59 (1995). When the trial court sustains an objection and instructs the jury to disregard, but denies a defendant's motion for mistrial, the issue is whether the trial court erred in denying the mistrial. Id. We review this issue under an abuse of discretion standard. Hawkins v. State, 135 S.W.3d 72, 77 (Tex.Cr.App.2004). Only in extreme circumstances, where the prejudice is incurable, will a mistrial be required. Id. We balance the following three factors outlined in Mosley v. State to evaluate whether the trial court abused its discretion in denying a mistrial for improper jury argument: (1) the severity of the misconduct (prejudicial effect), (2) curative measures, and (3) the certainty of the punishment assessed absent the misconduct (likelihood of the same punishment being assessed).FN12 Id. Counsel is allowed wide latitude in drawing inferences from the evidence so long as the inferences drawn are reasonable, fair, legitimate, and offered in good faith. Cantu v. State, 871 S.W.2d 667, 690 (Tex.Cr.App.1992), cert. denied, 509 U.S. 926 (1993).

FN12. See Mosley v. State, 983 S.W.2d 249, 259 (Tex.Cr.App.1998) (op. on reh'g); cert. denied, 526 U.S. 1070, 119 S.Ct. 1466, 143 L.Ed.2d 550 (1999).

In his thirteenth point of error, appellant complains that the trial court erred in failing to grant a mistrial after the prosecutor told the jurors that defense counsel was advancing a theory that Mary was “nothing but a whore.” The challenged portion is as follows:

[THE STATE]: And the solicitude—and John is a sincere guy and I think he meant it. The solicitude, though, that he showed for [Mary] really flies in the face of the defensive theory, which means she is nothing but a whore.

[APPELLANT]: Objection, Your Honor.

[TRIAL COURT]: Sustained.

[APPELLANT]: I would ask for the jury to be given an instruction to disregard.

[THE COURT]: The jury will disregard the last statement by counsel. And when you're instructed to disregard, it is as if it has not happened. That means you don't discuss it and you don't talk about it, and you don't use it in your deliberations.

[APPELLANT]: We feel that an instruction is insufficient to cure the harm. We would ask for a mistrial at this time.

[TRIAL COURT]: That's denied.

[THE STATE]: They want you to believe that she had consensual sex on the same night with two men she had just met.

Here, the defensive theory was that Mary had consensual sex with appellant and Ward. Therefore, while the term “whore” was not used by the defense, they painted a picture of Mary in which the term “whore” would not be an unreasonable characterization of the defense's description of Mary. In addition, any error or prejudice from the argument was cured by the trial court's instruction to disregard. See Andujo v. State, 755 S.W.2d 138, 144 (Tex.Cr.App.1988) (any injury from improper argument is ordinarily obviated when the court instructs the jury to disregard the argument). Appellant's thirteenth point of error is overruled.

Appellant argues in his fourteenth point of error that the prosecutor misstated the testimony of a forensic DNA analyst (Connie Patton). The challenged portion of jury argument is as follows:

[THE STATE]: Remember Pat Gass, our crime scene officer who went out and picked up the weapon with Mike Carroll? He told you that he took sections from the passenger seat of the truck, and Connie, said, I got sections from the passenger's seat of the truck and [Mary] could not be excluded as a potential contributor to the blood.

[APPELLANT]: I believe that's a misstatement of the evidence, Your Honor.

[THE STATE]: And interestingly—

[TRIAL COURT]: In what way, counsel?

[THE STATE]: I'm sorry, Judge.

[APPELLANT]: I don't believe she specified blood.

[TRIAL COURT]: I am going to overrule the objection. The jury will remember the specific testimony.

Officer Pat Gass testified that he found some apparent blood on the fabric in the headliner and the seat fabric in appellant's truck, which he collected during his investigation but he did not know what was done with the evidence.

The testimony of the DNA analyst (Patton) regarding the fabric from the truck is as follows:

Q: [THE STATE]: Okay. Any of the materials that were taken from a vehicle, the truck, headliner, the seat cover, anything like that, did any of those connect back to [Mary]?

A: [PATTON]: The stain from the right front passenger seat, the profile was a mixture of at least two individuals in which neither the victim or Mr. Sheldon Ward could be excluded as a possible contributor.

Q: Okay. You know from which vehicle that was taken?

A: I do not know.

Q: Okay. Anything from the headliner of the truck?

A: Blood was not detected on that item.

The appellant points out that Patton did not know from which vehicle the seat cover came, but Officer Gass previously testified the seat cover came from the pickup truck. However, Detective McCaskill testified that no forensic evidence was retrieved from the truck. In reviewing all the testimony regarding the blood from the truck, we find that the State's jury argument is a deduction of the combined testimony of Gass and Patton, but was a misstatement of the record based on Detective McCaskill's testimony. Thus, the trial court erred when it overruled appellant's objection. However, we find the error harmless. There are three factors to consider when assessing the impact of the harm arising from jury argument error under Rule 44.2(b) of the Texas Rules of Appellate Procedure, for non-constitutional error: (1) severity of the misconduct, (the magnitude of the prejudicial effect of the prosecutor's remarks), (2) measures adopted to cure the misconduct (the efficacy of any cautionary instruction by the judge), and (3) the certainty of conviction absent the misconduct (the strength of the evidence supporting conviction).FN13