Executed August 5, 2013 06:17 p.m. EST by Lethal Injection in Florida

23rd murderer executed in U.S. in 2013

1343rd murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

4th murderer executed in Florida in 2013

78th murderer executed in Florida since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(23) |

|

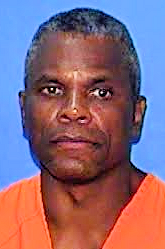

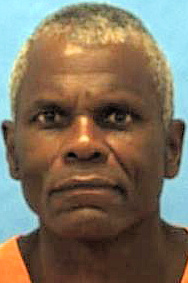

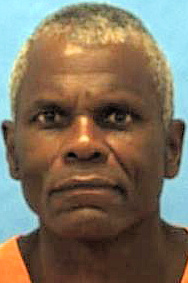

John Errol Ferguson B / M / 29 - 55 |

Brian Glenfeldt W / M / 17 Belinda Worley W / F / 17 Livingston Stocker W / M / 33 Michael Miller W / M / 24 Henry Clayton W / M / 35 John Holmes W / M / 26 Gilbert Williams W / M / 37 Charles Cesar Stinson W / M / 35 |

01-08-78 07-27-77 07-27-77 07-27-77 07-27-77 07-27-77 07-27-77 |

05-27-83 05-25-78 05-27-83 |

Accomplice White was convicted on all counts and was sentenced to death despite a jury's recommendation for life. He was executed on in 1987. Accomplice Francois was convicted on all counts and was also sentenced to death. He was executed in 1985. Accomplice Adolphus Archie, who drove the car used to drop off and pick up the shooters, pled guilty to Second-Degree Murder and was sentenced to twenty years imprisonment.

Brian Glenfeld and Belinda Worley, both 17 years old, were last seen around 9:00 p.m. on Sunday, 01/08/78. The two were supposed to meet friends at an ice cream parlor, but their bodies were discovered the next morning in a wooded area. Glenfeld’s body was behind the wheel of a car, with gunshot wounds to his chest, arm, and head. Worley’s body was found in a nearby dense growth, where she had been raped and then shot in the head. Several pieces of Worley’s jewelry were missing and cash was missing from Glenfeld’s wallet. Three months later, Ferguson was arrested at his apartment pursuant to a warrant for unlawful flight to avoid prosecution. At the time of the arrest, Ferguson was under indictment for the six murders that occurred in 1977. After a consent search of the apartment, in which a gun was recovered that was similar to the gun used to kill Glenfeld and Worley, Ferguson admitted to shooting the couple.

Citations:

Ferguson v. State, 417 So.2d 631 (Fla. App. 1982). (Glenfeld/Worley Direct Appeal)

Ferguson v. State, 417 So.2d 639 (Fla. App. 1982). (6 Murders Direct Appeal)

Ferguson v. State, 474 So.2d 208 (Fla. App. 1985). (After Resentencing - Direct Appeal)

Ferguson v. State, 593 So.2d 508 (Fla. App. 1992). (6 Murders - PCR)

Ferguson v. State, 112 So.3d 1154 (Fla. 2012). (Sanity)

VFerguson v. Secretary for Dept. of Corrections, 580 F.3d 1183 (11th Cir. 2009). (Habeas)

Final / Special Meal:

Ferguson chose to eat the same food other prisoners were being served as his final meal: A meat and vegetable patty, white bread, stewed tomatoes, potato salad, carrots and iced tea.

Final Words:

"I just want everyone to know that I am the prince of God and will rise again."

Internet Sources:

Florida Department of Corrections

DC Number: 015110Current Prison Sentence History:

Offense Date, Offense, Sentence Date, County, Case No., Prison Sentence Length

07/27/1977 1ST DG MUR/PREMED. OR ATT. 05/25/1978 MIAMI-DADE 7728650 DEATH SENTENCE

Incarceration History:

05/31/1978 to 08/05/2013

When John Errol Ferguson was 21 years old, he stole a deputy’s gun and was about to shoot when the deputy fished another gun from his boot, shooting Ferguson four times — including a round to the head. In 1975, Ferguson was diagnosed as homicidal and dangerous by court psychiatrists when he was acquitted of six robberies and two assault charges on a plea of insanity. A court-appointed psychiatrist said he was "dangerous to himself and others, homicidal and should not be released under any circumstances." He was was sent to the Florida mental hospital, from which he later escaped.

In May of 1977, police found an elderly couple from St. Petersburg — in town for a funeral — shot to death at Miami’s Gold Dust motel. The couple had been tied up, robbed, brutally beaten and shot, execution-style.

On 27 July 1977, Ferguson, posing as a Florida Power and Light employee, was let into a home by Margaret Wooden on a ruse to check the electrical outlets. After looking in several rooms, Ferguson drew a gun, then bound and blindfolded Margaret. Ferguson let two men, Marvin Francois and Beauford White, into the home to continue searching for drugs and money. Two hours later, the owner of the home, Livingston Stocker, and five friends returned home and were bound, blindfolded, and searched by Ferguson, Francois, and White. The seven bound and blindfolded people were then moved from the living room to a bedroom. Later, Wooden’s boyfriend, Michael Miller, entered the house and was bound, blindfolded, and searched. Miller and Wooden were moved to another bedroom together and the other six men were moved to the living room. At some point in the evening, Marvin Francois’ mask fell off and his face was revealed to the others. Wooden heard shots coming from the living room, where Francois was shooting the men. Ferguson placed a pillow over Wooden’s head and then shot her. Not fatally wounded, Wooden saw Miller being shot and heard Ferguson run from the room. She managed to escape and ran to a neighbor's house to call the police. When the police arrived, they found six dead bodies, all of which had their hands tied behind their back and had been shot in the back of the head. Johnnie Hall survived a shotgun blast to the head and testified regarding the execution of the other men in the living room.

Ferguson was also convicted of attempted murder in the robbery of another couple at a lover's lane. On October 30, he shot and wounded two teenagers when they refused to unlock the car door. The couple drove off, wounded but alive. The next day, he raped a woman. He was also suspected but not charged with the brutal robbery slaying of an elderly St. Petersburg couple at a Miami motel on Biscayne Boulevard. They were in town to attend a funeral. The same gun was used in that crime.

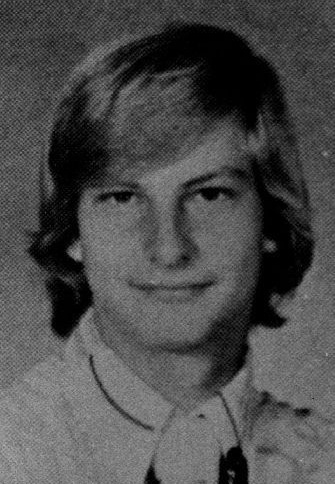

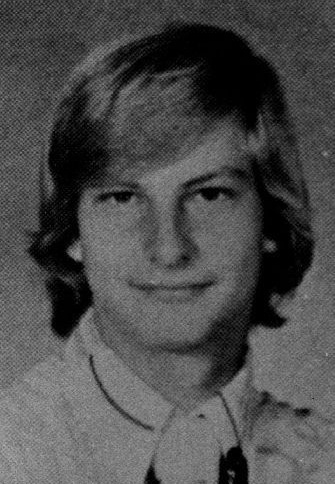

On the evening of 8 January 1978, Brian Glenfeldt and Belinda Worley, both seventeen, left a Youth-for-Christ meeting in Hialeah, Florida. They were supposed to meet friends at an ice cream parlor, but never arrived. The next morning, two passersby discovered their bodies in a nearby wooded area. Glenfeldt had been killed by a bullet to the head and also had been shot in the chest and arm. Worley was found several hundred yards away under a dense growth. All of her clothes, except for her jeans, were next to her body, and she had been shot in the back of the head. An autopsy revealed that she had been raped. At trial, there was testimony that she had been wearing jewelry, but none was found with the bodies. The cash from Glenfeldt’s wallet, which was found in Worley’s purse near her body, also had been removed.

On 5 April 1978, police arrested Ferguson at his apartment pursuant to a warrant for unlawful flight to avoid prosecution in connection with the Carol City murders. At the time of his arrest, police found in his possession a .357 magnum, which was capable of firing .38 caliber bullets, the same kind used to kill Glenfeldt and Worley. The gun was registered to Stocker, one of the victims in the Carol City murders. At some point after Ferguson’s arrest, he confessed to killing “the two kids,” i.e., Glenfeldt and Worley.

Ferguson, White, and Francois were indicted together as coconspirators, but each was tried separately. White was convicted on all counts of the indictment. The jury recommended life imprisonment, but the judge sentenced him to death. White was executed on 08/28/87. Francois was convicted on all counts of the indictment. The jury recommended death sentences, and he was sentenced to death. Francois was executed on 05/29/85. Adolphus Archie, who drove the car used to drop off and pick up the shooters, pled guilty to Second-Degree Murder and was sentenced to twenty years imprisonment.

"Florida executes mass murderer said by lawyers to be mentally ill," by David Adams. (MIAMI | Mon Aug 5, 2013 7:49pm EDT)

(Reuters) - A Florida man who has spent 35 years on death row for killing eight people was executed on Monday despite a last-minute appeal by lawyers claiming he was insane.

John Errol Ferguson, 65, who was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death in 1978 for a pair of killing sprees, was pronounced dead at 6:17 p.m. EDT from lethal injection, said Misty Cash, a spokeswoman for the Florida Department of Corrections.

Hours before his execution, the U.S. Supreme Court denied Ferguson a stay of execution. The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) filed an amicus brief last week, along with three Florida mental health organizations, asking the top court to halt the execution, arguing Ferguson had a long history of severe mental illness.

The brief argued Ferguson's execution would violate the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution requiring an individual to have a rational understanding of why he is being put to death and the effect of the death penalty.

"Mr. Ferguson is insane and incompetent for execution by any measure," his attorney, Christopher Handman, said in a statement after the court's decision on Monday.

"He has a fixed delusion that he is the 'Prince of God' who cannot be killed and will rise up after his execution to fight alongside Jesus and save America from a communist plot," Handman said. He has no rational understanding of the reason for his execution or the effect the death penalty will have upon him."

In his last statement, Ferguson uttered, "I just want everyone to know, I am the 'Prince of God' and I will rise again," Cash said.

In July 1977, Ferguson fatally shot six people execution-style during a drug-related home robbery in a northern Miami suburb. Six months later, he killed two teenagers after they left a church meeting.

State psychiatrists and other medical professionals have diagnosed Ferguson as a paranoid schizophrenic with a long history of mental illness, according to his defense team.

Courts, however, have repeatedly rejected claims he was too mentally ill to be executed.

Florida Governor Rick Scott signed Ferguson's death warrant in September, but a few weeks later delayed the execution while a team of physicians met to decide whether Ferguson was mentally competent.

After a 90-minute examination and brief consultation a panel of psychiatrists determined that Ferguson was sane. A state circuit judge agreed in a ruling.

The U.S. 11th Circuit Court of Appeals in May rejected his appeal, ruling that Ferguson was mentally competent.

"That most people would characterize Ferguson's Prince-of-God belief, in the vernacular, as 'crazy' does not mean that someone who holds that belief is not competent to be executed," the appeals court found.

"Miami killer John Errol Ferguson executed," by David Ovalle. (Monday, 08.05.13)

STARKE -- After a life of bloodshed on the streets of Miami-Dade, then 35 years lingering on Death Row, Miami murderer John Errol Ferguson’s eyes darted to the execution supervisor looming over him.

“I just want everyone to know that I am the Prince of God and I will rise again,” Ferguson mumbled.

Then, the jowly and grayed 65-year-old rustled his feet underneath the white sheet of the gurney, lifted his head and peered intently at the witness window of the death chamber. At 6:01 p.m. Monday, the lethal drugs pumped through his veins, his head rested down, his mouth gasped and life slowly and quietly slipped away.

Ferguson, a killer of eight and at one time responsible for the largest mass slaughter in Miami-Dade history, was pronounced dead 6:17 p.m.

His execution caps a legacy of violence dating back to 1977, as well as a high-profile legal fight over whether Ferguson’s longtime schizophrenia and stated belief that he is the “Prince of God” made his execution a cruel and unusual punishment.

Michael Worley, whose 17-year-old sister Belinda Worley was raped and shot to death in 1978, said he believed Ferguson’s insanity was “fabricated and coached” even until the end.

“Thank goodness justice finally prevailed and he was finally executed,” Worley told the Miami Herald on Monday night. “I think he got off easy compared to what he did to the victims.”

Ferguson’s lawyers, who witnessed Monday’s execution, had fought for years to spare Ferguson, saying the man had a 40-year history of mental illness dating back to well before the murders.

Lawyer Christopher Handman criticized the U.S. Supreme Court, which on Monday afternoon denied a last-minute appeal to stay the execution.

“He has a fixed delusion that he is the ‘Prince of God’ who cannot be killed and will rise up after his execution to fight alongside Jesus and save America from a communist plot,” Handman said. “He has no rational understanding of the reason for his execution or the effect the death penalty will have upon him.”

Ferguson was the fifth Florida Death Row inmate to be executed since December.

In May, Gov. Rick Scott also signed a death warrant for Miami killer Marshall Lee Gore, but his execution has twice been stayed as his lawyers seek to halt it based on claims he, too, is mentally ill and should not executed. In recent months, Scott has accelerated the pace of death warrants.

Ferguson was one of the state’s longest serving Death Row inmates.

Prosecutors convicted Ferguson of the July 1977 shotgun murders of six people in Carol City during a home-invasion robbery. At the time, it was considered the worst mass murder in Miami-Dade history.

The dead: Livingstone Stocker, 33; Michael Miller, 24; Henry Clayton, 35; John Holmes, 26; Gilbert Williams, 37, and Charles Cesar Stinson, 35. Two survived: Johnnie Hall, 45, and Margaret Wooden, 24.

Ferguson was also convicted separately of murdering Worley and Glenfeldt, both 17-year-old Hialeah High students, in January 1978. The two had gone for ice cream, then parked at a field known as a popular lover’s lane.

Police said Ferguson tried robbing the couple, shooting Glenfeldt behind the wheel of his mother’s 1974 Pontiac LeMans, while Worley’s body was discovered a quarter-mile away; she had been raped and shot.

Michael Worley, who was 13 when his sister was killed, choked up when remembering her Monday night: “She was a good girl. I looked up to her. She had a lot of plans for life and she didn’t get a chance to see them through. He took it away from her.” Worley, who now lives in Broward County, did not attended the execution of his sister’s killer.

Ferguson was also convicted of attempted murder in the robbery of another couple at a lover’s lane. And he was a suspect, but never charged, with the robbery and killing of an elderly couple at a Miami motel.

Monday’s execution date came 10 months after Ferguson was originally slated to die by lethal injection at Florida State Prison in Starke.

After months of legal wrangling, the U.S. 11th Circuit Court of Appeals in May rejected his appeal, upholding a trial judge’s ruling that Ferguson was competent to be executed.

“That most people would characterize Ferguson’s Prince-of-God belief, in the vernacular, as ‘crazy’ does not mean that someone who holds that belief is not competent to be executed,” according to the federal appeals court’s 65-page opinion.

His lawyers insisted that the state courts and the federal appeals court applied the wrong legal standard, set by the U.S. Supreme Court years ago, in determining Ferguson’s competency.

The federal appeals court’s ruling set the stage for Monday’s new execution date.

Just hours before he was killed, Ferguson dined on standard inmate fare: a meat patty with white bread, steamed tomatoes, potato salad, diced carrots and iced tea.

The convicted killer also met with two of his attorneys, Handman and Patricia Brannon, as well as a spiritual advisor: Sister Marina Aranzabal, according to a corrections spokeswoman.

Several unidentified relatives of the dead sat in the front-row of the death chamber, which has a one-way window facing Ferguson.

In the stuffy and eerie silence, the relatives sat stone-faced until a mocha-colored curtain rose to reveal Ferguson, strapped into the gurney, IVs discretely inserted into veins on each arm.

They sat stone faced but clearly apprehensive. One woman clasped her hands, prayer-like, resting them just below her nose as she watched. Next to her, a man cupped his mouth and chin, tapping his fingers on his lips.

As the minutes ticked away, the drugs took effect.

At 6:17 p.m., a doctor walked in, slid Ferguson’s eyelids up with his fingers and shined a flashlight into his pupils. No response. A stethoscope confirmed: Ferguson was dead.

"After 30 years on Death Row, Miami mass killer executed," by David Ovalle. (6:39 p.m. EDT, August 5, 2013)

The Miami Herald — John Errol Ferguson, 65, was executed Monday evening after serving three decades on Florida’s death row for eight Miami-Dade murders in 1977 and 1978, the Miami Herald reported.

His last words were unintelligible to witnesses; he was declared dead at 6:17 p.m.

"John Errol Ferguson, convicted mass murderer, executed in Florida. (August 5, 2013 4:36 PM, Updated 8:00 p.m. ET)

(CBS/AP) STARKE, Fla. - John Errol Ferguson, a mass murderer from Miami-Dade County, was executed by lethal injection at Florida State Prison 6 p.m. ET Monday.

The 65-year-old was convicted of killing eight people in South Florida in two separate incidents in the 1970s..

Ferguson made a brief final statement before 25 witnesses before his execution.

"I just want everyone to know that I am the prince of God and will rise again," he said calmly, according to The Associated Press.

In the first incident, Ferguson gained entry into a Carol City home on July 27, 1977, by posing as a utility employee. He then bound and blindfolded Margaret Wooden, the woman who let him in, and also let two accomplices into the home. In time, seven more people - Henry Clayton, Johnnie Hall, Randolph Holmes, Michael Miller, Charles Stinson, Livingston Stocker and Gilbert Williams - came to the house and were bound and blindfolded.

Ferguson placed a pillow over Wooden's head and shot her, but she survived. The other seven men were shot execution-style in the back of the head. Hall survived a shotgun blast to the head, but the rest of the men died. Both of Ferguson's accomplices were executed in the 1980s.

While under indictment for the Carol City murders, Ferguson murdered two Hialeah teenagers who were on their way to a church meeting in 1978. Posing as a police officer, Ferguson confronted Brian Glenfeldt and Belinda Worley, both 17 years old. Ferguson shot Glenfeldt in the back of the head, the chest and the arm. Ferguson then took Worley into the woods, raped her and shot her in the back of the head. Ferguson also took the teenagers' money and jewelry.

Gov. Rick Scott initially signed Ferguson's death warrant last fall, scheduling him to die Oct. 16, 2012. But appeals at the state and federal level kept the execution from going forward. Ferguson's lawyers have filed numerous appeals in several courts. They contend their client is mentally ill and has suffered from schizophrenia since he was a teen. Ferguson's lawyers say several psychiatrists have ruled over the years that Ferguson is mentally ill. Most of those evaluations came when Ferguson was in a state mental hospital in the 1970s. If Ferguson's execution is carried out, he will be the fifth death row inmate in Florida to be executed since December, the Miami Herald reports.

Following is a list of inmates executed since Florida resumed executions in 1979:

1. John Spenkelink, 30, executed May 25, 1979, for the murder of traveling companion Joe Szymankiewicz in a Tallahassee hotel room.

2. Robert Sullivan, 36, died in the electric chair Nov. 30, 1983, for the April 9, 1973, shotgun slaying of Homestead hotel-restaurant assistant manager Donald Schmidt.

3. Anthony Antone, 66, executed Jan. 26, 1984, for masterminding the Oct. 23, 1975, contract killing of Tampa private detective Richard Cloud.

4. Arthur F. Goode III, 30, executed April 5, 1984, for killing 9-year-old Jason Verdow of Cape Coral March 5, 1976.

5. James Adams, 47, died in the electric chair on May 10, 1984, for beating Fort Pierce millionaire rancher Edgar Brown to death with a fire poker during a 1973 robbery attempt.

6. Carl Shriner, 30, executed June 20, 1984, for killing 32-year-old Gainesville convenience-store clerk Judith Ann Carter, who was shot five times.

7. David L. Washington, 34, executed July 13, 1984, for the murders of three Dade County residents _ Daniel Pridgen, Katrina Birk and University of Miami student Frank Meli _ during a 10-day span in 1976.

8. Ernest John Dobbert Jr., 46, executed Sept. 7, 1984, for the 1971 killing of his 9-year-old daughter Kelly Ann in Jacksonville..

9. James Dupree Henry, 34, executed Sept. 20, 1984, for the March 23, 1974, murder of 81-year-old Orlando civil rights leader Zellie L. Riley.

10. Timothy Palmes, 37, executed in November 1984 for the Oct. 19, 1976, stabbing death of Jacksonville furniture store owner James N. Stone. He was a co-defendant with Ronald John Michael Straight, executed May 20, 1986.

11. James David Raulerson, 33, executed Jan. 30, 1985, for gunning down Jacksonville police Officer Michael Stewart on April 27, 1975.

12. Johnny Paul Witt, 42, executed March 6, 1985, for killing, sexually abusing and mutilating Jonathan Mark Kushner, the 11-year-old son of a University of South Florida professor, Oct. 28, 1973.

13. Marvin Francois, 39, executed May 29, 1985, for shooting six people July 27, 1977, in the robbery of a ``drug house'' in the Miami suburb of Carol City. He was a co-defendant with Beauford White, executed Aug. 28, 1987.

14. Daniel Morris Thomas, 37, executed April 15, 1986, for shooting University of Florida associate professor Charles Anderson, raping the man's wife as he lay dying, then shooting the family dog on New Year's Day 1976.

15. David Livingston Funchess, 39, executed April 22, 1986, for the Dec. 16, 1974, stabbing deaths of 53-year-old Anna Waldrop and 56-year-old Clayton Ragan during a holdup in a Jacksonville lounge.

16. Ronald John Michael Straight, 42, executed May 20, 1986, for the Oct. 4, 1976, murder of Jacksonville businessman James N. Stone. He was a co-defendant with Timothy Palmes, executed Jan. 30, 1985.

17. Beauford White, 41, executed Aug. 28, 1987, for his role in the July 27, 1977, shooting of eight people, six fatally, during the robbery of a small-time drug dealer's home in Carol City, a Miami suburb. He was a co-defendant with Marvin Francois, executed May 29, 1985.

18. Willie Jasper Darden, 54, executed March 15, 1988, for the September 1973 shooting of James C. Turman in Lakeland.

19. Jeffrey Joseph Daugherty, 33, executed March 15, 1988, for the March 1976 murder of hitchhiker Lavonne Patricia Sailer in Brevard County.

20. Theodore Robert Bundy, 42, executed Jan. 24, 1989, for the rape and murder of 12-year-old Kimberly Leach of Lake City at the end of a cross-country killing spree. Leach was kidnapped Feb. 9, 1978, and her body was found three months later some 32 miles west of Lake City.

21. Aubry Dennis Adams Jr., 31, executed May 4, 1989, for strangling 8-year-old Trisa Gail Thornley on Jan. 23, 1978, in Ocala.

22. Jessie Joseph Tafero, 43, executed May 4, 1990, for the February 1976 shooting deaths of Florida Highway Patrolman Phillip Black and his friend Donald Irwin, a Canadian constable from Kitchener, Ontario. Flames shot from Tafero's head during the execution.

23. Anthony Bertolotti, 38, executed July 27, 1990, for the Sept. 27, 1983, stabbing death and rape of Carol Ward in Orange County.

24. James William Hamblen, 61, executed Sept. 21, 1990, for the April 24, 1984, shooting death of Laureen Jean Edwards during a robbery at the victim's Jacksonville lingerie shop.

25. Raymond Robert Clark, 49, executed Nov. 19, 1990, for the April 27, 1977, shooting murder of scrap metal dealer David Drake in Pinellas County.

26. Roy Allen Harich, 32, executed April 24, 1991, for the June 27, 1981, sexual assault, shooting and slashing death of Carlene Kelly near Daytona Beach.

27. Bobby Marion Francis, 46, executed June 25, 1991, for the June 17, 1975, murder of drug informant Titus R. Walters in Key West.

28. Nollie Lee Martin, 43, executed May 12, 1992, for the 1977 murder of a 19-year-old George Washington University student, who was working at a Delray Beach convenience store.

29. Edward Dean Kennedy, 47, executed July 21, 1992, for the April 11, 1981, slayings of Florida Highway Patrol Trooper Howard McDermon and Floyd Cone after escaping from Union Correctional Institution.

30. Robert Dale Henderson, 48, executed April 21, 1993, for the 1982 shootings of three hitchhikers in Hernando County. He confessed to 12 murders in five states.

31. Larry Joe Johnson, 49, executed May 8, 1993, for the 1979 slaying of James Hadden, a service station attendant in small north Florida town of Lee in Madison County. Veterans groups claimed Johnson suffered from post-traumatic stress syndrome.

32. Michael Alan Durocher, 33, executed Aug. 25, 1993, for the 1983 murders of his girlfriend, Grace Reed, her daughter, Candice, and his 6-month-old son Joshua in Clay County. Durocher also convicted in two other killings.

33. Roy Allen Stewart, 38, executed April 22, 1994, for beating, raping and strangling of 77-year-old Margaret Haizlip of Perrine in Dade County on Feb. 22, 1978.

34. Bernard Bolander, 42, executed July 18, 1995, for the Dade County murders of four men, whose bodies were set afire in car trunk on Jan. 8, 1980.

35. Jerry White, 47, executed Dec. 4, 1995, for the slaying of a customer in an Orange County grocery store robbery in 1981.

36. Phillip A. Atkins, 40, executed Dec. 5, 1995, for the molestation and rape of a 6-year-old Lakeland boy in 1981.

37. John Earl Bush, 38, executed Oct. 21, 1996, for the 1982 slaying of Francis Slater, an heir to the Envinrude outboard motor fortune. Slater was working in a Stuart convenience store when she was kidnapped and murdered.

38. John Mills Jr., 41, executed Dec. 6, 1996, for the fatal shooting of Les Lawhon in Wakulla and burglarizing Lawhon's home.

39. Pedro Medina, 39, executed March 25, 1997, for the 1982 slaying of his neighbor Dorothy James, 52, in Orlando. Medina was the first Cuban who came to Florida in the Mariel boat lift to be executed in Florida. During his execution, flames burst from behind the mask over his face, delaying Florida executions for almost a year.

40. Gerald Eugene Stano, 46, executed March 23, 1998, for the slaying of Cathy Scharf, 17, of Port Orange, who disappeared Nov. 14, 1973. Stano confessed to killing 41 women.

41. Leo Alexander Jones, 47, executed March 24, 1998, for the May 23, 1981, slaying of Jacksonville police Officer Thomas Szafranski.

42. Judy Buenoano, 54, executed March 30, 1998, for the poisoning death of her husband, Air Force Sgt. James Goodyear, Sept. 16, 1971.

43. Daniel Remeta, 40, executed March 31, 1998, for the murder of Ocala convenience store clerk Mehrle Reeder in February 1985, the first of five killings in three states laid to Remeta.

44. Allen Lee ``Tiny'' Davis, 54, executed in a new electric chair on July 8, 1999, for the May 11, 1982, slayings of Jacksonville resident Nancy Weiler and her daughters, Kristina and Katherine. Bleeding from Davis' nose prompted continued examination of effectiveness of electrocution and the switch to lethal injection.

45. Terry M. Sims, 58, became the first Florida inmate to be executed by injection on Feb. 23, 2000. Sims died for the 1977 slaying of a volunteer deputy sheriff in a central Florida robbery.

46. Anthony Bryan, 40, died from lethal injection Feb. 24, 2000, for the 1983 slaying of George Wilson, 60, a night watchman abducted from his job at a seafood wholesaler in Pascagoula, Miss., and killed in Florida.

47. Bennie Demps, 49, died from lethal injection June 7, 2000, for the 1976 murder of another prison inmate, Alfred Sturgis. Demps spent 29 years on death row before he was executed.

48. Thomas Provenzano, 51, died from lethal injection on June 21, 2000, for a 1984 shooting at the Orange County courthouse in Orlando. Provenzano was sentenced to death for the murder of William ``Arnie'' Wilkerson, 60.

49. Dan Patrick Hauser, 30, died from lethal injection on Aug. 25, 2000, for the 1995 murder of Melanie Rodrigues, a waitress and dancer in Destin. Hauser dropped all his legal appeals.

50. Edward Castro, died from lethal injection on Dec. 7, 2000, for the 1987 choking and stabbing death of 56-year-old Austin Carter Scott, who was lured to Castro's efficiency apartment in Ocala by the promise of Old Milwaukee beer. Castro dropped all his appeals.

51. Robert Glock, 39 died from lethal injection on Jan. 11, 2001, for the kidnapping murder of a Sharilyn Ritchie, a teacher in Manatee County. She was kidnapped outside a Bradenton shopping mall and taken to an orange grove in Pasco County, where she was robbed and killed. Glock's co-defendant Robert Puiatti remains on death row.

52. Rigoberto Sanchez-Velasco, 43, died of lethal injection on Oct. 2, 2002, after dropping appeals from his conviction in the December 1986 rape-slaying of 11-year-old Katixa ``Kathy'' Ecenarro in Hialeah. Sanchez-Velasco also killed two fellow inmates while on death row.

53. Aileen Wuornos, 46, died from lethal injection on Oct. 9, 2002, after dropping appeals for deaths of six men along central Florida highways.

54. Linroy Bottoson, 63, died of lethal injection on Dec. 9, 2002, for the 1979 murder of Catherine Alexander, who was robbed, held captive for 83 hours, stabbed 16 times and then fatally crushed by a car.

55. Amos King, 48, executed by lethal inection for the March 18, 1977 slaying of 68-year-old Natalie Brady in her Tarpon Spring home. King was a work-release inmate in a nearby prison.

56. Newton Slawson, 48, executed by lethal injection for the April 11, 1989 slaying of four members of a Tampa family. Slawson was convicted in the shooting deaths of Gerald and Peggy Wood, who was 8 1/2 months pregnant, and their two young children, Glendon, 3, and Jennifer, 4. Slawson sliced Peggy Wood's body with a knife and pulled out her fetus, which had two gunshot wounds and multiple cuts.

57. Paul Hill, 49, executed for the July 29, 1994, shooting deaths of Dr. John Bayard Britton and his bodyguard, retired Air Force Lt. Col. James Herman Barrett, and the wounding of Barrett's wife outside the Ladies Center in Pensacola.

58. Johnny Robinson, died by lethal injection on Feb. 4, 2004, for the Aug. 12, 1985 slaying of Beverly St. George was traveling from Plant City to Virginia in August 1985 when her car broke down on Interstate 95, south of St. Augustine. He abducted her at gunpoint, took her to a cemetery, raped her and killed her.

59. John Blackwelder, 49, was executed by injection on May 26, 2004, for the calculated slaying in May 2000 of Raymond Wigley, who was serving a life term for murder. Blackwelder, who was serving a life sentence for a series of sex convictions, pleaded guilty to the slaying so he would receive the death penalty.

60. Glen Ocha, 47, was executed by injection April 5, 2005, for the October, 1999, strangulation of 28-year-old convenience store employee Carol Skjerva, who had driven him to his Osceola County home and had sex with him. He had dropped all appeals.

61. Clarence Hill 20 September 2006 lethal injection Stephen Taylor

62. Arthur Dennis Rutherford 19 October 2006 lethal injection Stella Salamon

63. Danny Rolling 25 October 2006 lethal injection Sonja Larson, Christina Powell, Christa Hoyt, Manuel R. Taboada, and Tracy Inez Paules

64. Ángel Nieves Díaz 13 December 2006 lethal injection Joseph Nagy

65. Mark Dean Schwab 1 July 2008 lethal injection Junny Rios-Martinez, Jr.

66. Richard Henyard 23 September 2008 lethal injection Jamilya and Jasmine Lewis

67. Wayne Tompkins 11 February 2009 lethal injection Lisa DeCarr

68. John Richard Marek 19 August 2009 lethal injection Adela Marie Simmons

69. Martin Grossman 16 February 2010 lethal injection Margaret Peggy Park

70. Manuel Valle 28 September 2011 lethal injection Louis Pena

71. Oba Chandler 15 November 2011 lethal injection Joan Rogers, Michelle Rogers and Christe Rogers

72. Robert Waterhouse 15 February 2012 lethal injection Deborah Kammerer

73. David Alan Gore 12 April 2012 lethal injection Lynn Elliott

74. Manuel Pardo 11 December 2012 lethal injection Mario Amador, Roberto Alfonso, Luis Robledo, Ulpiano Ledo, Michael Millot, Fara Quintero, Fara Musa, Ramon Alvero, Daisy Ricard.

75. Larry Eugene Mann 10 April 2013 lethal injection Elisa Nelson

76. Elmer Leon Carroll 29 May 2013 lethal injection Christine McGowan

77. William Edward Van Poyck 12 June 2013 lethal injection Ronald Griffis

78. John Errol Ferguson 05 August 2013 lethal injection Livingstone Stocker, Michael Miller, Henry Clayton, John Holmes, Gilbert Williams, and Charles Cesar Stinson

Florida Commission on Capital Cases

Inmate: Ferguson, John Errol

Eleventh Judicial Circuit, Dade County Case #s: 77-28650-D & 78-05428

Case # 77-28650-D

Circumstances of Offense: On 07/27/77, John Ferguson, posing as a Florida Power and Light employee, was let into a home by Margaret Wooden to check the electrical outlets. After looking in several rooms, Ferguson drew a gun, then bound and blindfolded Wooden. Ferguson let two men, Marvin Francois and Beauford White, into the home to continue searching for drugs and money. Two hours later, the owner of the home, Livingston Stocker, and five friends returned home and were bound, blindfolded, and searched by Ferguson, Francois, and White. The seven bound and blindfolded people were then moved from the living room to a bedroom.

Later, Wooden’s boyfriend, Michael Miller, entered the house and was bound, blindfolded, and searched. Miller and Wooden were moved to another bedroom together and the other six men were moved to the living room. At some point in the evening, Marvin Francois’ mask fell off and his face was revealed to the others. Wooden heard shots coming from the living room, where Francois was shooting the men. Ferguson placed a pillow over Wooden’s head and then shot her. Not fatally wounded, Wooden saw Miller being shot and heard Ferguson run from the room.

When the police arrived, they found six dead bodies, all of which had their hands tied behind their back and had been shot in the back of the head. Johnnie Hall survived a shotgun blast to the head and testified regarding the execution of the other men in the living room.

Codefendant Information: Ferguson, White, and Francois were indicted together as coconspirators, but each was tried separately. White was convicted on all counts of the indictment. The jury recommended life imprisonment, but the judge sentenced him to death. White was executed on 08/28/87. Francois was convicted on all counts of the indictment. The jury recommended death sentences, and he was sentenced to death. Francois was executed on 05/29/85. Adolphus Archie, who drove the car used to drop off and pick up the shooters, pled guilty to Second-Degree Murder and was sentenced to twenty years imprisonment.

Trial Summary:

09/15/77 Indicted as follows: Counts I – VI First-Degree Murder, Count VII Attempted First-Degree Murder, Count VIII Attempted First-Degree Murder, Counts IX – XI Armed Robbery.

05/24/78 Jury returned acquitted verdict on Count XII

05/25/78 Jury returned guilty verdicts on Counts I – XI of the indictment

Jury recommended death sentences by a majority vote

Sentenced as follows: Counts I – VI First-Degree Murder – Death, Count VII - Attempted First-Degree Murder – 30 years, Count VIII - Attempted First-Degree Murder – 30 years, Counts IX – XI - Armed Robbery – Life imprisonment

Case # 78-05428

Circumstances of Offense: Brian Glenfeld and Belinda Worley, both seventeen years old, were last seen around 9:00 p.m. on Sunday, 01/08/78. The two were supposed to meet friends at an ice cream parlor, but their bodies were discovered the next morning in a wooded area. Glenfeld’s body was behind the wheel of a car, with gunshot wounds to his chest, arm, and head. Worley’s body was found in a nearby dense growth, where she had been raped and then shot in the head. Several pieces of Worley’s jewelry were missing and cash was missing from Glenfeld’s wallet.

On 04/05/78, John Ferguson was arrested at his apartment pursuant to a warrant for unlawful flight to avoid prosecution. At the time of the arrest, Ferguson was under indictment for the six murders that occurred on 07/27/77 (case # 77-28650-D). After a consent search of the apartment, in which a gun was recovered that was similar to the gun used to kill Glenfeld and Worley, Ferguson admitted to shooting the couple.

Trial Summary:

04/13/78 Indicted as follows: Count I First-Degree Murder, Count II First-Degree Murder, Count III Armed Sexual Battery, Count IV Armed Robbery, Count V Armed Robbery, Count VI Unlawful Possession of a Firearm While Engaged in a Criminal Offense, Count VII Possession of a Firearm by a Felon, Count VIII Possession of a Firearm by a Felon.

10/07/78 Jury returned guilty verdicts on all counts of the indictment (Count V was reduced to Attempted Armed Robbery by the jury)

Jury recommended death sentences by a majority vote

Sentenced as follows: Count I First-Degree Murder – Death, Count II First-Degree Murder – Death, Count III Armed Sexual Battery – Life Imprisonment, Count IV Armed Robbery – Life Imprisonment, Count V Armed Robbery – 15 year, Count VI Unlawful Possession of a Firearm While Engaged in a Criminal Offense – 15 years, Count VII Possession of a Firearm by a Felon – 15 years, Count VIII Possession of a Firearm by a Felon – 15 years

Prior Incarceration History in the State of Florida:

At the time of each of the murders, Ferguson was on probation, having already served an eighteen month prison sentence for a 1976 conviction for Resisting a Police Officer with Violence. Ferguson’s prior criminal history also included a 1971 Robbery conviction and a 1965 Assault with Intent to Rape conviction, for which Ferguson was sentenced to ten years imprisonment.

Appeal Summary:

Florida Supreme Court – Direct Appeal (Case# 77-28650-D)

Florida Supreme Court – Direct Appeal (Case# 78-05428)

Florida Supreme Court – Direct Appeal (Consolidated)

Circuit Court – 3.850 Motion

Florida Supreme Court – 3.850 Motion Appeal

Florida Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

U.S. District Court, Southern District – Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

Circuit Court – 3.850 Motion

Florida Supreme Court – 3.850 Motion Appeal

U.S. Court of Appeals, 11th Circuit – Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus Appeal

U.S. Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Clemency Hearing: 03/10/87 Clemency hearing held (denied)

Factors Contributing to the Delay in Imposition of Sentence: The delay in this case appears to arise from the resentencing of Ferguson and from the pending Federal Habeas Petition that was filed on 03/20/95.

Case Information:

Ferguson filed a Direct Appeal (FSC# 55,137; CC# 77-28650-D) with the Florida Supreme Court on 09/25/78, citing the following errors: unconstitutionality of the death penalty, failure to provide written statements of support for the death penalty in the case, improper prosecutorial comments during closing arguments, and admission of prejudicial statements about Ferguson’s prior incarceration. On 07/15/82, the FSC affirmed the convictions, but vacated the death sentences and remanded to the trial court for a new sentencing hearing, finding that the trial court improperly weighed the aggravating and mitigating circumstances in the case.

Ferguson filed a Direct Appeal (FSC# 55,498; CC# 78-05428) with the Florida Supreme Court on 11/13/78, citing the following errors: unconstitutionality of the death penalty, failure to suppress evidence, admission of evidence of the other murders, and improper prosecutorial comments during closing arguments. On 07/15/82, the FSC affirmed the convictions, but vacated the death sentences and remanded to the trial court for a new sentencing hearing, finding that the trial court improperly weighed the mitigating circumstances in the case.

Ferguson was resentenced to death on 05/27/83.

Ferguson filed a Direct Appeal with the Florida Supreme Court on 10/10/83, citing the following errors: failure to allow an evidentiary hearing during resentencing; improper finding of the cold, calculated, and premeditated murder aggravating circumstance; and consideration of evidence not in the trial record. On 06/27/85, the FSC affirmed the death sentence.

Ferguson filed a 3.850 Motion with the Circuit Court on 10/15/87, which was denied on 06/19/90.

Ferguson filed a 3.850 Motion Appeal with the Florida Supreme Court on 08/10/90, citing ineffective assistance of counsel and improper jury instructions regarding non-statutory mitigating evidence. On 02/06/92, the FSC affirmed the denial of the 3.850 Motion.

Ferguson filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus with the Florida Supreme Court on 10/01/92, citing the following errors: a different sentencing judge upon resentencing; vague jury instructions regarding the heinous, atrocious, or cruel murder aggravating circumstances; failure to grant a defense motion to stop giving Ferguson anti-psychotic drugs; and ineffective assistance of appellate counsel. The FSC denied the Petition on 12/09/93.

Ferguson filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus with the U.S. District Court, Southern District on 03/20/95. On 05/15/00, the USDC administratively closed the case pending resolution of state proceedings. On 08/07/01, the case was reopened, and on 11/02/01, Ferguson filed a supplemental brief with the court. On 09/26/03, Ferguson amended the Petition. The petition was denied on 05/19/05.

Ferguson filed a 3.850 Motion with the Circuit Court on 07/10/99, which was denied on 08/18/99.

Ferguson filed a 3.850 Motion Appeal with the Florida Supreme Court on 01/27/00, citing eleven issues, most of which focused on claims of ineffective assistance of counsel and withholding of evidence by the State. On 05/10/01, the FSC affirmed the denial of the 3.850 Motion.

Ferguson filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus Appeal with the U.S. Court of Appeals, 11th Circuit on 06/17/05. The District Courts denial of the Petition was affirmed by the U.S. Court of Appeals on 08/26/09.

Ferguson filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari with the U.S. Supreme Court on 03/31/10. The petition was denied on 06/01/10.

Ferguson v. State, 417 So.2d 631 (Fla. App. 1982). (Direct Appeal)

Defendant was convicted in the Circuit Court, Dade County, Richard S. Fuller, J., of first-degree murder, involuntary sexual battery, robbery, attempted robbery, unlawful possession of a firearm while engaged in a criminal offense and possession of a firearm by a convicted felon and sentenced to death, and he appealed. The Supreme Court, Adkins, J., held that: (1) the Florida death penalty statutes are constitutional; (2) statements made by the defendant after he knowingly and voluntarily waived his right to have counsel present were admissible; (3) evidence supported the conclusion that the woman who had been living in the defendant's apartment had the authority to consent to a warrantless search; (4) evidence supported determinations that the defendant was sane at the time of the offense and that he was competent to stand trial; (5) testimony that the defendant had been present at the scene of a separate multiple-murder incident was admissible as being relevant to identity; (6) the defendant was not a “person under sentence of imprisonment” at the time of the offense as that term is used in the aggravating circumstance; and (7) the sentencing judge applied the wrong standard in determining the presence or absence of two mitigating circumstances related to emotional distress. Judgment of conviction affirmed; death sentence vacated and cause remanded. Sundberg, J., concurred in the result only. Boyd, J., concurred in part and dissented in part with an opinion.

ADKINS, Justice.

Appellant, John Errol Ferguson, was found guilty on two counts of first-degree murder, one count of involuntary sexual battery, one count of robbery, one count of attempted robbery, one count of unlawful possession of a firearm while engaged in a criminal offense, and one count of possession of a firearm by a convicted felon. He now appeals his convictions on the above and the resulting sentences of death and imprisonment. We have jurisdiction. Art. V, § 3(b)(1), Fla.Const.

Brian Glenfeld and Belinda Worley were last seen leaving a Youth for Christ meeting around 9:00 p. m. on Sunday, January 8, 1978. The two seventeen-year-olds were supposed to meet friends at an ice cream parlor. The next morning their bodies were discovered in a wooded area by two passersby.

Brian's body was behind the wheel of the car. He'd been shot in the chest and arm. A bullet to the head had killed him. Belinda's body was several hundred yards away in a dense growth. All she had on were her jeans; her other clothes were next to her body. She'd been shot in the back of the head. An autopsy indicated she'd been raped.

Brian's father testified that Belinda was wearing two rings, a gold bracelet and a pair of earrings when she and Brian left on Sunday evening. None of the jewelry was found with the bodies. Belinda's earlobe was torn where an earring had been taken. Brian's empty wallet was found in Belinda's purse near her body. His father had seen both the wallet and some cash in Brian's possession the previous evening.

On April 5, 1978, the defendant was arrested at his apartment pursuant to a warrant for unlawful flight to avoid prosecution; he was under indictment for another multiple-murder, the so-called Carol City murders. The defendant was read his Miranda rights each time he was questioned. He signed a consent to search form and allowed the officers to search the apartment. His roommate, Virginia Polk, also consented to the search. After the search, which produced probable evidence in another robbery, the defendant confessed to killing the “two kids.” At the time of his arrest he had in his possession a .357 magnum capable of firing .38 caliber bullets like those which killed Brian and Belinda.

The gun was registered to Livingston Stocker, a victim of the Carol City murders. Margaret Wooden, a survivor of that incident, testified that the defendant had been in Stocker's Carol City house on July 27, 1977, the night he was murdered. The defendant was convicted on two counts of first degree murder. The jury recommended the death penalty and the judge concurred in imposing the death sentence.

We reject the constitutional challenges to the death penalty. It is neither cruel and unusual punishment, Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153, 96 S.Ct. 2909, 49 L.Ed.2d 859 (1976), nor a violation of due process or equal protection. Proffitt v. Florida, 428 U.S. 242, 96 S.Ct. 2960, 49 L.Ed.2d 918 (1976).

The trial court denied defendant's pre-trial motions to suppress statements made on April 5, 1978, the day of his arrest. Evidence at the suppression hearing showed that defendant was represented by counsel as of about 3:00 p. m. the day he was taken into custody. Defendant's attorney visited his client and claimed that he advised the officers involved that he didn't want anyone talking to his client unless he was present. This was contradicted by the state's evidence and the trial court found that such communication did not take place. The defendant was questioned at least twice after this and admitted the crimes without his attorney being present.

The trial judge in the case before us specifically found that the defendant knowingly and voluntarily waived his Fifth Amendment right. Witt v. State, 342 So.2d 497 (Fla.), cert. denied, 434 U.S. 935, 98 S.Ct. 422, 54 L.Ed.2d 294 (1977). The waiver is effective even though the defendant is represented by counsel and the officers are aware of that fact. United States v. Brown, 569 F.2d 236 (5th Cir. 1978); United States v. Vasquez, 476 F.2d 730 (5th Cir. 1973). The defendant in this case was questioned by three different officers investigating three separate incidents. Each time he was approached, the defendant was advised of his rights and clearly consented to talking without an attorney. When he finally did ask to speak with his lawyer, all questions ceased. Michigan v. Moseley, 423 U.S. 96, 96 S.Ct. 321, 46 L.Ed.2d 313 (1975). The statements were properly admitted into evidence.

The trial court also admitted physical evidence taken from defendant's apartment on the day of his arrest. The detective who searched the apartment did so after obtaining consent from a woman who had been living with the defendant. The test for a valid third-party consent to a warrantless search is whether the third party has joint control of the premises. United States v. Matlock, 415 U.S. 164, 98 S.Ct. 218, 54 L.Ed.2d 152 (1974); Silva v. State, 344 So.2d 559 (Fla.1977). In this instance the entire living space, including closets, of the one-bedroom apartment had been shared by the defendant with the third party. At the suppression hearing there was conflicting evidence as to whether the woman had ceased to reside in the apartment a few days earlier. The trial court resolved this question against the defendant, finding that the third party had joint access and control at the time she gave permission. There is nothing in the record to overcome the presumption of correctness with which that finding reaches this Court. State v. Nova, 361 So.2d 411 (Fla.1978).

Having found a valid third-party consent, we need not reach the validity of the defendant's consent in signing a consent to search form. The evidence obtained at the apartment was not taken in violation of defendant's constitutional rights.

Yet another pre-trial motion was denied by the trial court; this alleged that the defendant was insane at the time of the offense and incompetent to stand trial at all times thereafter. The Florida standard for sanity at the time of the offense is the ability to distinguish right and wrong. Witt v. State; Wheeler v. State, 344 So.2d 244 (Fla.1977), cert. denied, 440 U.S. 924 (1979). The test for competency to stand trial is whether a defendant has sufficient present ability to consult with and aid his attorney in the preparation of a defense with a reasonable degree of understanding. Although the medical evidence was conflicting, there was adequate testimony to support the trial judge's finding that defendant was competent to stand trial.

Byrd v. State, 297 So.2d 22 (Fla.1974); Fowler v. State, 255 So.2d 513 (Fla.1971), later appeal, 263 So.2d 202 (Fla.1972). Defendant's sanity at the time of the offense was a factual issue determined adversely to him by the jury's verdict. The evidence is sufficient to sustain this finding by the jury.

During the trial, Margaret Wooden was allowed to testify over defendant's objection that the defendant had been present at the scene of the Carol City murders. The trial court properly denied the defense motion for a mistrial since this evidence tended to establish the defendant's identity as perpetrator of the crime. Dean v. State, 277 So.2d 13 (Fla.1973); Ashley v. State, 265 So.2d 685 (Fla.1972); Williams v. State, 110 So.2d 654 (Fla.1959). One of the crucial pieces of evidence in this case was the .357 magnum revolver found in defendant's possession upon his arrest. Since nearly four months had elapsed between the date of the crime and the date of arrest, the point at which defendant obtained possession of the weapon was obviously important to the state's case. Another witness testified he'd been present in Stocker's house on July 27, 1977, when a similar .357 magnum was taken from the bedroom. Margaret Wooden was the only person who could place the defendant in Stocker's house on that date, some five and one-half months prior to the day the two teenagers were killed. Review of the testimony shows that both the court and the prosecutor made every effort to avoid prejudicing the defendant by referring to the Carol City homicides. The record supports the admission of the evidence as relevant to identity.

The defendant also contends that the prosecutor improperly commented in closing argument on the defendant's failure to testify:

[S]o there is a lot of reasons why that glitter was on that blue shirt and you'll also remember John Ferguson said, excuse me, Virginia Polk said that John Ferguson washed the clothes....

Taken in context, the prosecutor obviously said the defendant's name when he meant to say Virginia Polk. He immediately corrected the error. This is not an example of resort to improper methods to obtain convictions as suggested by the defendant. Rolle v. State, 268 So.2d 541 (Fla. 3d DCA 1972). The trial court acted within its discretion in denying the defendant's motion for mistrial. Johnsen v. State, 332 So.2d 69 (Fla.1976).

At the close of the state's case the defendant moved for a judgment of acquittal on the two counts of robbery. The court denied the motions and the jury found defendant guilty of robbery of Brian and attempted robbery of Belinda. In circumstantial evidence cases the evidence must not only be consistent with guilt but also be inconsistent with any reasonable hypothesis of innocence. Davis v. State, 90 So.2d 629 (Fla.1956). The crux of the matter is that all the state could show was that the victims had valuables on their persons before they were killed and that the jewelry was missing when the bodies were discovered. The defense argues that since the bodies were in the wooded area overnight, anyone passing by could have stolen the money and jewelry. We agree with the state that this is not a reasonable hypothesis of innocence: there was evidence that the jewelry was taken with some degree of violence; it rained very hard that night; and the bodies were found just a few hours after sunrise. See People v. Hubler, 102 Cal.App.2d 689, 228 P.2d 37 (2d Dist. 1951).

The defendant's final point on appeal concerns the actual execution of the death sentence. Essentially he argues that he has a First Amendment right to have his execution televised. We need not reach the merits of this argument inasmuch as the claim is not properly before this Court. The execution of the death sentence is regulated by statute and carried out by the Department of Corrections, a part of the executive branch of government. § 922.10 and . 11, Fla.Stat. (Supp.1978). The defendant raised this issue in a post trial motion before the trial court. Other than specifically described post trial motions, there is no jurisdictional basis for that court to act in this cause after the imposition of sentence. See, e.g., Fla.R.Crim.P. 3.700; 3.810; and 3.850.

The trial court made written findings of fact in support of the death sentence. The finding, as an aggravating circumstance, that the defendant was under a sentence of imprisonment at the time that he committed the crimes for which he was sentenced is improper. At the time of the murders, defendant was serving a two-year period of probation which followed an eighteen-month period of incarceration. He was not confined in prison at the time, nor was he supposed to be. In Peek v. State, 395 So.2d 492 (Fla.1981), cert. denied, 451 U.S. 964, 101 S.Ct. 2036, 68 L.Ed.2d 342 (1981), we held that:

Persons who are under an order of probation and are not at the time of the commission of the capital offense incarcerated or escapees from incarceration do not fall within the phrase “person under sentence of imprisonment” as set forth in section 921.141(5)(a).

Id. at 499. Thus defendant was not a “person under sentence of imprisonment.”

Our negation of said aggravating circumstance would not, however, change the result of this case in the absence of mitigating circumstances. In such cases, a reversal of the death sentence is not necessarily required, as any error that occurred in the consideration of the inapplicable aggravating circumstances was harmless. See Shriner v. State, 386 So.2d 525 (Fla.1980), cert. denied, 449 U.S. 1103, 101 S.Ct. 899, 66 L.Ed.2d 829 (1981); Dobbert v. State, 375 So.2d 1069 (Fla.1979), cert. denied, 447 U.S. 912, 101 S.Ct. 3000, 64 L.Ed.2d 862 (1980).

The trial court also found that the defendant had previously been convicted of three felonies involving the use of threat or violence to some person and that the crime was committed in the commission of a robbery and for the purpose of avoiding or preventing a lawful arrest. In support of the latter, the court observed:

It is obvious that the execution style of terminating the lives of the two victims was the result of a thoughtful plan to make certain that there would be no witnesses to the robberies and/or the involuntary sexual battery committed. This conduct is reflective of a well thought out plan to make certain that this defendant would not be discovered or his identity ever revealed.

The final finding in aggravation was that the crime was especially heinous, atrocious, and cruel:

The facts reveal that the two victims were seated in an automobile and while seated therein a gunshot was fired through the window striking Brian Glenfeld in the arm and chest area. A significant amount of bleeding followed and this victim's blood was found throughout many areas of the front of the automobile as well as on the clothing of Belinda Worley. Following the shooting, the female victim ran many hundreds of feet from the car in an attempt to allude [sic] the defendant and was finally overtaken in some rather dense overgrowth and trees. She was subjected to many physical abuses by this defendant, including but not limited to, sexual penetration of her vagina and anus. The discovery of embedded dirt in her fingers, on her torso both front and back and in many areas within her mouth and the findings of hemorrhaging around her vagina and anal cavity would indicate that she put up a significant struggle and suffered substantially during the perpetration of these indignities upon her body. Expert testimony indicates that she was a virgin at the time of the occur[r]ence of this crime. The position of her body and the location of the wounds on her head would indicate that she was in a kneeling position at the time she was shot through the top of the head. She was left in a partially nude condition in the area where the crime was committed to be thereafter fed upon by insects and other predators. Physical evidence would substantiate that following the attack upon Belinda Worley the defendant went back to the car and shot Brian Glenfeld through the head. See § 921.141(5), Fla.Stat. (1977).

The only possible mitigating circumstance involved the defendant's mental state and his ability to appreciate the criminality of his conduct. § 921.141(6)(b) and (f), Fla.Stat. (1977). In rejecting this as a mitigating factor the trial court said:

At the time of an appearance before the Court on another matter wherein a plea of not guilty by reason of insanity was entered the Court appointed three disinterested psychiatrists; Drs., Harry Graff, Charles Mutter and Albert Jaslow. Subsequent thereto, Dr. Norman Reichenberg was also appointed to do psychological testing.

This defendant has a history of mental disorder and has been previously committed to The State Hospital. His mental disorder has been the subject of more than one diagnosis. He was found competent prior to his sentencing in The Criminal Division of the Circuit Court of the Eleventh Judicial Circuit in and for Dade County, Florida, in 1976, and thereafter concluded his period of incarceration in The State Prison System and was placed on probation. Following the filing of the reports by the referenced physicians and in a pre-trial conference, counsel represented the defendant in the other pending matter indicating that he was not going to present the issue of insanity in that case. This Court thereafter specifically found that the defendant was competent to stand trial, to understand the seriousness of the charges and able to assist his counsel in his defense. During the trial of the other matter which took place in May, 1978, the defendant aided his counsel and participated in his own defense. During the course of that trial he made some observations about people in the courtroom and these observations were minimally disruptive. His comments at that time were consistent with a person diagnosed as a sociopath.

Communications by the defendant to the Court following adjudication in the other matter relating to his treatment in the jail and his inability to have confidence in his Court appointed counsel to represent him in the instant case caused this Court to hold a hearing which ultimately led to the release of prior counsel and appointment of an attorney requested by the defendant who had represented him or members of his family in other matters. Upon the appointment of the new counsel, Michael Hacker, Esquire, additional physicians were retained by the defendant and a plea of not guilty by reason of insanity was filed in the instant case. A hearing was duly called to determine not only the defendant's competency to be tried on the instant case but also a test of his competency at the time of the commission of the crimes in the other matter and at the trial of the other matter. Testimony was taken from at least seven professional witnesses, all with generally conflicting opinions and/or evidence upon which opinions were reached. This Court determined that the defendant was competent to aid counsel at the time of the trial of the instant case, was competent at the trial of the last case, was competent at the commission of the crimes in the instant case and at the times of the commission of the crimes in the other matter. The Court specifically held that the defendant knew the difference between right and wrong and was able to recognize the criminality of his conduct and to make a voluntary and intelligent choice as to his conduct based upon knowledge of the consequences thereof.

The defendant has been diagnosed as suffering from a number of mental disorders: a basic paranoia schizophrenia psychotic process; Ganser syndrome; malingering, and a behavior characteristic commonly referred to as sociopathic. This defendant's conduct from crime through trial is indicative of an individual who has an absolute understanding of the events and the consequences thereof. There is nothing that would indicate that this defendant did not recognize the criminality of his conduct at the time of the commission of the subject offenses. The evidence requires the finding that this defendant was sane at the time of the commission of the instant offense consistent with the standards of the M'Naghten Rule and therefore this mitigating circumstance is not applicable. (Emphasis supplied.)

Apparently the judge applied the wrong standard in determining the presence or absence of the two mitigating circumstances related to emotional disturbance, so we have no alternative but to return this case to the trial judge for resentencing. As we stated in Mines v. State, 390 So.2d 332, 337 (Fla.1980), cert. denied, 447 U.S. 1, 101 S.Ct. 1994, 64 L.Ed.2d 681 (1981):

Under the provisions of section 921.141(6), Florida Statutes (1975), there are two mitigating circumstances relating to a defendant's mental condition which should be considered before the imposition of a death sentence: “(b) The capital felony was committed while the defendant was under the influence of extreme mental or emotional disturbance”; and “(f) The capacity of the defendant to appreciate the criminality of his conduct or to conform his conduct to the requirements of law was substantially impaired.” From the record it is clear that the trial court properly concluded that the appellant was sane, and the defense of not guilty by reason of insanity was inappropriate. The finding of sanity, however, does not eliminate consideration of the statutory mitigating factors concerning mental condition.

The sentencing judge here, just as in Mines ; misconceived the standard to be applied in assessing the existence of mitigating factors (b) and (f). From reading his sentencing order we can draw no other conclusion but that the judge applied the test for insanity. He even referred to the “M'Naghten Rule” which is the traditional rule in this state for determination of sanity at the time of the offense. It is clear from Mines that the classic insanity test is not the appropriate standard for judging the applicability of mitigating circumstances under section 921.141(6), Florida Statutes.

In the absence of any mitigating factors, the death sentence would be held appropriate on review. Other execution style murders have warranted imposition of the ultimate penalty. See Jackson v. State, 359 So.2d 1190 (Fla.1978), cert. denied, 439 U.S. 1102, 99 S.Ct. 881, 59 L.Ed.2d 63 (1979); Gibson v. State, 351 So.2d 948 (Fla.1977), cert. denied, 435 U.S. 1004, 98 S.Ct. 1661, 56 L.Ed.2d 93 (1978); and Sullivan v. State, 303 So.2d 632 (Fla.1974), cert. denied, 428 U.S. 911, 96 S.Ct. 3226, 49 L.Ed.2d 1220 (1976). Evidence of mental or emotional distress does not necessarily outweigh a heinous, atrocious or cruel crime. Foster v. State, 369 So.2d 928 (Fla.), cert. denied, 444 U.S. 885, 100 S.Ct. 178, 62 L.Ed.2d 116 (1979).

However, in our review capacity we must be able to ascertain whether the trial judge properly considered and weighed these mitigating factors. Their existence would not as a matter of law, invalidate a death sentence, for a trial judge in exercising a reasoned judgment could find that a death sentence is appropriate. It is improper for us, in our review capacity, to make such a judgment.

The judgment of conviction is affirmed. The death sentence is vacated and the cause is remanded to the trial court for the purpose of determining an appropriate sentence. An additional sentence advisory verdict by a jury is not required.

ALDERMAN, C. J., and OVERTON and McDONALD, JJ., concur. SUNDBERG, J., concurs in result only. BOYD, J., concurs in part and dissents in part with an opinion.

BOYD, Justice, concurring in part and dissenting in part.

I would affirm the convictions and would also affirm the death penalty.

Ferguson v. State, 417 So.2d 639 (Fla. App. 1982). (Direct Appeal)

Defendant was convicted in the Circuit Court, Dade County, Richard S. Fuller, J., of six counts of murder in the first degree, two counts of attempted murder in the first degree, and three counts of robbery with firearm and sentenced to death and imprisonment. Direct appeal was taken. The Supreme Court, Adkins, J., held that: (1) the death penalty statutes are constitutional; (2) the prosecutor's allegedly improper comment that defendant was asking the jury to find a scapegoat for his guilt and put the blame on someone else who was already found guilty did not amount to reversible error; (3) testimony of a witness concerning prior imprisonment of the defendant was not so prejudicial as to warrant a reversal; (4) the findings as to two of the aggravating circumstances were improper; and (5) the trial court applied an improper standard in assessing the existence of mitigating factors of the defendant's mental state and his ability to appreciate the criminality of his conduct. Conviction affirmed; death sentence vacated and cause remanded. Sundberg, J., concurred in the result only. Boyd, J., concurred in part and dissented in part with an opinion.

ADKINS, Justice.

This is a direct appeal from an order adjudging the appellant guilty of six counts of murder in the first degree, two counts of attempted murder in the first degree, and three counts of robbery with a firearm, and imposing sentences of death and imprisonment. We have jurisdiction. Art. V, § 3(b)(1), Fla.Const.

On July 27, 1977, at approximately 8:15 p. m. the defendant, posing as an employee of the power company, requested permission from Margaret Wooden to enter her Carol City home and check the electrical outlets. After gaining entry and checking several rooms, the defendant drew a gun and tied and blindfolded Miss Wooden. He then let two men into the house who joined the defendant in searching for drugs and money.

Some two hours later, the owner of the house, Livingston Stocker, and five friends returned home. The defendant, who identified himself to Miss Wooden as “Lucky,” and his cohorts tied, blindfolded and searched the six men. All seven victims were then moved from the living room to the northeast bedroom.

Shortly thereafter, Miss Wooden's boyfriend, Miller, entered the house. He too was bound and searched. Then he and Miss Wooden were moved to her bedroom and the other six victims returned to the living room.

At some point one intruder's mask fell, revealing his face to the others. Miller and Wooden were kneeling on the floor with their upper bodies lying across the bed. Wooden heard shots from the living room then saw a pillow coming toward her head. She was shot. She saw Miller get shot then heard the defendant run out of the room. She managed to get out and run to a neighbor's house to call the police.

When the police arrived they found six dead bodies. All had been shot in the back of the head, their hands tied behind their backs. One of the victims, Johnnie Hall, had survived a shotgun blast to the back of his head. He testified to the methodical execution of the other men.

On September 15, 1977, the defendant and three co-defendants were indicted for the offense. Adolphus Archie, the “wheelman”, was allowed to plead guilty to second degree murder and a twenty-year concurrent sentence on all counts in exchange for testimony at trial. He testified he'd dropped the defendant, Marvin Francois, and Beauford White in the Carol City area to “rip off” a drug house. He didn't see the actual shooting but later saw unfamiliar weapons and jewelry in Beauford's and Francois' possession.

The defendant was tried alone and convicted on all counts. After an advisory sentencing hearing the jury recommended death. The judge followed that recommendation.

Four issues are raised on appeal. One is patently without merit. The death penalty in Florida as prescribed in section 921.141, Florida Statutes (1977), has been upheld repeatedly against arguments that it constitutes cruel and unusual punishment or violates the constitutional guaranties of equal protection and due process. See Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153, 96 S.Ct. 2909, 49 L.Ed.2d 859 (1976); Proffitt v. Florida, 428 U.S. 242, 96 S.Ct. 2960, 49 L.Ed.2d 918 (1976); Spinkellink v. Wainwright, 578 F.2d 582 (5th Cir. 1978).

A second issue raised by defendant was that the trial court had failed to provide written findings in support of the sentence of death. § 921.141(3), Fla.Stat. (1977). Inasmuch as the supplemental record includes the trial judge's written findings this issue is now moot.

The third issue involves the following allegedly improper comment by the prosecution in closing argument: “[N]ot only did [defense counsel] ask you to find a scapegoat for Mr. Ferguson's guilt, he puts the blame on someone else who has already been found guilty, Marvin Francois.” A victim had identified Francois as an accomplice and the wheelman also implicated Francois. The defendant thus argues that the above comment said to the jury, if Francois is guilty then, ipso facto, defendant must be guilty.

There are several reasons we decline to find reversible error in this comment. First, the only objection made to the comment was a general one, followed by a motion for a mistrial. It is well settled that objections must be made with sufficient specificity to apprise the trial court of the potential error and to preserve the point for appellate review. Castor v. State, 365 So.2d 701 (Fla.1978); Clark v. State, 363 So.2d 331 (Fla.1978). The desirability and need for specified grounds also apply to motions for mistrials. A mistrial is a device used to halt the proceedings when the error is so prejudicial and fundamental that the expenditure of further time and expense would be wasteful if not futile. Johnsen v. State, 332 So.2d 69 (Fla.1976). Even if the comment is objectionable on some obvious ground, the proper procedure is to request an instruction from the court that the jury disregard the remarks. A motion for mistrial is addressed to the sound discretion of the trial judge and “the power to declare a mistrial and discharge the jury should be exercised with great care and should be done only in cases of absolute necessity.” Salvatore v. State of Florida, 366 So.2d 745, 750 (Fla.1978), cert. denied, 444 U.S. 885, 100 S.Ct. 177, 62 L.Ed.2d 115 (citations omitted). Even if the general objection and request for a mistrial properly preserved this point for appellate review, we find that the trial judge correctly denied the motion. The comment was made on rebuttal in response to the theory presented by the defense during its closing argument that Francois and White had committed the crime and the defendant had never even been in the house, but had been misidentified by the victims. The prosecutor's comment fell within the bounds of a “fair reply” which is permissible in this instance. See Brown v. State, 367 So.2d 616 (Fla.1979). Viewed in this context, the comment on Francois' guilt was not sufficiently prejudicial to warrant a mistrial in this case. Cf. Thomas v. State, 202 So.2d 883 (Fla. 3d DCA 1967) (prosecutor told jury of accomplice's conviction during voir dire and again during trial); and Moore v. State, 186 So.2d 56 (Fla. 3d DCA 1966) (judge announced co-defendant's guilty plea to jury as explanation for recess during trial). The fact that a jury hears of an accomplice's guilt does not necessarily constitute reversible error. See, e.g., Sanders v. State, 241 So.2d 430 (Fla. 3d DCA 1970); Walters v. State, 217 So.2d 615 (Fla. 2d DCA 1969); Vitiello v. State, 167 So.2d 629 (Fla. 3d DCA 1964); Grisette v. State, 152 So.2d 498 (Fla. 1st DCA 1963).

Defendant's final point on appeal concerns the testimony of Adolphus Archie, the “wheelman” who was allowed to plead to second degree murder for testifying. On direct examination Archie stated that the defendant knew Joe Swain (the person who allegedly orchestrated the killings) because “the first time ... my first time in prison, all three of us was together.” A general objection was overruled and a motion for mistrial denied. Initially, we reiterate our emphasis on the importance of stating specific grounds for objections and motions for mistrials. Also, especially in an instance such as this, a curative instruction should be requested. The defendant now contends that a prior imprisonment was irrelevant to his guilt or innocence in this case; the only result would be to show the defendant's “bad character.” Such remarks may be erroneously admitted yet not be so prejudicial as to require reversal. Darden v. State, 329 So.2d 287 (Fla.1976), cert. denied, 429 U.S. 1036, 97 S.Ct. 729, 50 L.Ed.2d 747 (1977); Thomas v. State, 326 So.2d 413 (Fla.1975). In Smith v. State, 365 So.2d 405 (Fla. 3d DCA 1978), the court noted that any prejudice arising from the admission of testimony indicating defendant's prior incarceration could have been corrected by an instruction to the jury to disregard the testimony. The court held that in the absence of a defense request for such an instruction, the trial court properly denied the motion for a mistrial. Our review of this record persuades us that the admission of Archie's testimony in this matter was not so prejudicial as to warrant a reversal. See Clark v. State, 363 So.2d 331 (Fla.1978).

The defendant in this case has not specifically attacked the sufficiency of the evidence supporting the conviction. It is nonetheless our duty to review the entire record. Tibbs v. State, 337 So.2d 788 (Fla.1978). It is abundantly clear that the evidence was sufficient and we therefore uphold the conviction.

We have also conducted an independent review of the sentencing proceedings and trial court's findings in aggravation and mitigation. Harvard v. State, 375 So.2d 833 (Fla.1977). That court found:

In support of this determination, the Court makes the following Findings of Fact relative to aggravating circumstances, consistent with Section 921.141(5) Florida Statutes.

(a) The crime for which the defendant was sentenced was committed while the defendant was under sentence of imprisonment. He had been convicted in The Circuit Court of the Eleventh Judicial Circuit in Case No. 76-4822, On September 16, 1976, of resisting an officer with violence and had been sentenced to The State Penitentiary for eighteen months to be followed by two years of probation. The sentence in the 76-4822 case had not been terminated and the case was still open. By stipulation the evidence in the subject case was adopted in the Probation Violation case and the probation was revoked by this Court on May 25, 1978.

(b) At the time of the crime for which this defendant was sentenced he had previously been convicted of three felonies involving the use or threat of violence to some person;

1. Eleventh Judicial Circuit No. Cr. 2237, Assault with Intent to Commit Rape, October 15, 1965, Judge Harold R. Vann, sentence ten years.

2. Eleventh Judicial Circuit Case No. 69-9963, Robbery, February 22, 1971, Judge Alto Adams.

3. Eleventh Judicial Circuit Case No. 76-4822, resisting officer with violence to his person. Eighteen months State Prison, followed by two years probation. September 16, 1976, Judge Alan R. Schwartz.