Executed July 24, 2008 9:07 p.m. by Lethal Injection in Virginia

15th murderer executed in U.S. in 2008

1114th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

4th murderer executed in Virginia in 2008

102nd murderer executed in Virginia since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

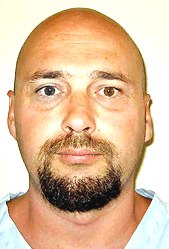

Christopher Scott Emmett W / M / 29 - 36 |

|

John F. Langley W / M / 43 |

with Lamp |

Citations:

Emmett v. Commonwealth, 264 Va. 364, 569 S.E.2d 39 (Va. 2002) (Direct Appeal).

Emmett v. Warden of Sussex I State Prison, 269 Va. 164, 609 S.E.2d 602 (Va. 2005) (Stae Habeas)

Emmett v. Johnson, --- F.3d ----, 2008 WL 2736034 (4th Cir. 2008) (Sec. 1983).

Emmett v. Kelly, 474 F.3d 154 (4th Cir. 2007) (Habeas).

Final/Special Meal:

Emmett requested a particular last meal but asked that his choices be kept private.

Final Words:

"Tell my family and friends I love them, tell the governor he just lost my vote. Y'all hurry this along, I'm dying to get out of here."

Internet Sources:

"State executes killer who challenged lethal injections," by Dena Potter. (Associated Press July 24, 2008)

JARRATT - A killer who unsuccessfully argued that Virginia's procedures for lethal injection were unconstitutional has been executed after a federal appeals court rejected his claims. Christopher Scott Emmett, 36, was pronounced dead at 9:07 p.m. Thursday. Gov. Tim Kaine declined to intervene in the execution. Emmett's final words were, "Tell my family and friends I love them, tell the governor he just lost my vote. Y'all hurry this along, I'm dying to get out of here."

Earlier this month, a divided three-judge panel of the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rejected Emmett's argument that Virginia's use of lethal injection amounts to cruel and unusual punishment because of the possibility that paralyzing and heart-stopping drugs could be administered before inmates are rendered unconscious by another drug. Emmett's lawyers asked the full court to hear his appeal, but justices voted 6-4 against taking up the issue.

Emmett's challenge was the first to require a federal appeals court to interpret a U.S. Supreme Court decision in April that upheld Kentucky's method of lethal injection and apply it to another state's procedures. The 4th Circuit panel found that Virginia's protocol for delivering the three-drug lethal cocktail was similar enough to Kentucky's that it would not cause inmates excruciating pain. Unlike Kentucky, Virginia does not allow for a second dose of sodium thiopental, which results in a deep, coma-like unconsciousness, even when a second round of the other drugs is required. Virginia also administers the three drugs more quickly than Kentucky corrections officials.

In 10 of the 70 lethal injections performed in Virginia before this year, a second dose of the last two drugs was given because the inmate did not die within a few minutes after the heart-stopping drug was administered, according to court papers. Although most inmates are pronounced dead within five minutes after the first drug is administered, the last two inmates executed in Virginia took approximately 10 minutes and 15 minutes to die, respectively. Department of Corrections officials will not confirm whether a second dose of drugs was given to those men.

Kaine stopped Emmett's execution in June 2007 so the U.S. Supreme Court would have time to consider his appeal, which it later rejected. Then in October, Emmett's execution was one of dozens halted by the Supreme Court while it considered the Kentucky lethal injection challenge.

Emmett, 36, and John Fenton Langley were sharing a room in a Danville motel in April of 2001 as part of an out-of-town roofing crew. On the night Langley was killed, he bought food and grilled for Emmett and other co-workers. They then played cards at the motel. Later as Langley slept, Emmett beat him to death with a brass lamp so he could steal Langley's wallet to buy crack cocaine

"My brother died a horrible, horrible death," said Gene Langley, 48, of Rocky Mount, N.C. "Christopher, he was a coward. ... He needs to be punished." Gene Langley and six other family members, including John Langley's adult daughter and son, plan to witness Emmett's execution. "It's not going to bring my brother back by no means in this world, but it does not allow him to live and that's what I'm after," Gene Langley said. "He didn't kill one person, he killed five — he killed a brother, he killed a son, he killed an uncle, he killed a father, and he killed a grandfather," he said.

Emmett met with immediate family members this morning, Department of Corrections spokesman Larry Traylor said.

"Emmett executed for 2001 murder," by Bill Mckelway. (Thursday, Jul 24, 2008 - 09:15 PM)

JARRATT — Christopher Scott Emmett was put to death tonight for the 2001 beating death of a co-worker in Danville. Emmett, who this afternoon dropped his appeals over the legality of lethal injections for executions, was pronounced dead at 9:07 p.m. He is the 102nd person executed in Virginia since restoration of the death penalty in 1976.

Gov. Timothy M. Kaine issued a statement less than four hours before the execution saying he would not stop it. “I find no compelling reason to set aside the sentence that was recommended by the jury, and then imposed and affirmed by the courts," Kaine said in the statement. "Accordingly, I decline to intervene.”

The 36-year-old Emmett, was sentenced to death for the April 2001 bludgeoning death of a co-worker, 43-year-old John F. Langley. Emmett beat Langley to death and stole $100 from his wallet to buy drugs. The two roofers from Roanoke Rapids, N.C. were sharing a motel room in Danville while they worked on a job near there.

Emmett’s execution came after years of arguments that Virginia’s use of lethal injection amounts to cruel and unusual punishment because of the possibility that paralyzing and heart-stopping drugs could be given before inmates are rendered unconscious by another drug. Last year Emmett gained reprieves two times within hours of his execution date.

Virginia Attorney General - Press Release.

For Release: June 13, 2007

Contact: J. Tucker Martin or David Clementson

Email: tucker.martin@oag.state.va.us or dclementson@oag.state.va.us

Phone: 804-786-2071

Statement of Attorney General Bob McDonnell on Governor’s Delay of Emmett Execution

Governor Kaine has delayed tonight’s scheduled execution of Christopher Scott Emmett for the murder of John Fenton Langley. This delay is based on a petition for certiorari filed by Emmett’s attorneys that has yet to be ruled on by the U.S. Supreme Court. Attorney General Bob McDonnell issued the following statement with regard to the Governor’s action:

“The Governor has the constitutional authority to take this action. Given the procedural posture of this case in the United States Supreme Court, and considering the interests of justice, I respect the Governor’s exercise of this authority.”

"Virginia Executes Man Who Killed Co-Worker," by Maria Glod. (Friday, July 25, 2008; Page B03)

JARRATT - Christopher S. Emmett was executed by lethal injection last night in Virginia's death chamber, seven years after he fatally bludgeoned a co-worker with a brass lamp. Emmett, 36, was pronounced dead at 9:07 p.m. at the Greensville Correctional Center in Jarratt, according to Larry Traylor, a Department of Corrections spokesman. The execution was the fourth in Virginia this year.

According to Traylor, Emmett's last words were: "Tell my family and friends I love them. Tell the governor he just lost my vote. Y'all hurry this along; I'm dying to get out of here."

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit, drawing on an April U.S. Supreme Court ruling that the three-drug protocol used in executions in Kentucky and most other states does not constitute cruel and unusual punishment, rejected Emmett's argument that Virginia's method of execution is unconstitutional. Emmett's attorneys had that prisoners might not be fully anesthetized before they are given drugs that can cause excruciating pain.

Virginia Gov. Timothy M. Kaine (D), who noted that Emmett's challenge to the state's lethal injection procedure was rejected by the courts, declined to intervene. "I find no compelling reason to set aside the sentence that was recommended by the jury, and then imposed and affirmed by the courts," Kaine said in a statement.

Emmett fatally beat his roofing company co-worker, John F. Langley, with a brass lamp in a Danville, Va., motel room in 2001. He then stole Langley's money to buy crack.

Langley's mother, Elizabeth Majors, 72, who lives in the Gasburg, Va., trailer she shared with her son, had no sympathy for Emmett's argument. She had planned to witness the execution. "Too painful for him?" said Majors, who said she carries her son's high school photo in her purse. "He didn't think about that when he took that lamp off the table and hit my son with it. I know my son had pain."

In a lethal injection procedure similar to that used in most states, Virginia administers sodium thiopental, which induces unconsciousness, followed by a drug that paralyzes the muscles and another that causes cardiac arrest. The latter two drugs can cause excruciating pain if the first drug is not administered properly. An appeals court panel found that Virginia's method is "substantially similar" to the one used in Kentucky and upheld by the Supreme Court. Virginia's method, the panel wrote in a majority opinion, does not create an "intolerable risk of severe pain."

In appeals, Emmett's attorneys said the decision marks the first time an appellate court has applied the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling to another state's execution protocol. They argued that Virginia's method differs from that used in Kentucky, noting that the state doesn't require a pause after the first drug is administered, or set out a process to ensure that an inmate is adequately sedated.

They contend that the lack of that safeguard can result in an "inhumane execution." "Of course, we're disappointed in the ruling," Matthew S. Hellman, an attorney for Emmett, said yesterday, "but we hope that Virginia's procedures will someday be improved."

Yesterday morning, Emmett met with family members, Traylor said. He requested a particular last meal but asked that his choices be kept private.

Virginia has executed 102 people since the Supreme Court reinstated capital punishment in 1976, second only to Texas.

In the early morning hours of April 27, 2001, Christopher Scott Emmett beat his sleeping coworker John Langley to death with the base of a brass motel room lamp in order to rob Langley and use his cash to buy crack cocaine.

Weldon Roofing Company employed Emmett and Langley as laborers for its roofing crews. During late April 2001, both men were assigned to a project in the City of Danville and shared a room at a local motel where the roofing crew was staying. On the evening of April 26, 2001, Emmett, Langley, Michael Darryl Pittman, and other members of the roofing crew cooked dinner on a grill at the motel, played cards, and drank beer. During the course of the evening, Langley loaned money to Emmett and Pittman, who used the money to buy crack cocaine.

At approximately 11:00 p.m. that evening, Rainey Bell, another member of the roofing crew, heard a noise he described as "bang, bang" coming from the room Emmett and Langley shared. Shortly after midnight, Emmett went to the motel office and asked the clerk to call the police, saying that he had returned to his room, "seen blood and stuff . . . and didn’t know what had took place." The police arrived at the motel at 12:46 a.m. on April 27, 2001 and accompanied Emmett back to his room. There they discovered Langley’s dead body lying face down on Langley’s bed beneath a comforter. Blood spatters were found on the sheets and headboard of Langley’s bed, on the wall behind it, and on the wall between the bathroom and Emmett’s bed. A damaged brass lamp stained with Langley’s blood was discovered beneath Langley’s bed.

In his initial statement to police, Emmett denied killing Langley. He stated that he had returned to the room and gone to bed. Emmett claimed to have discovered the blood and Langley’s body later that night when he got up to use the bathroom. Observing what appeared to be bloodstains on Emmett’s personal effects, the police took possession of Emmett’s boots and clothing with his permission. Emmett suggested that the blood might be his own because he had injured himself earlier in the week. Subsequent testing, however, revealed that Emmett’s boots and clothing were stained with Langley’s blood.

Later in the morning of April 27, Emmett voluntarily accompanied the police to the Danville police station. There he agreed to be fingerprinted and gave a sample of his blood. Emmett admitted to the police that he had been drinking and using cocaine on the previous evening. Over the course of the next several hours, Emmett related different versions of the events of the previous evening to the police. He first implicated Pittman as Langley’s murderer, but ultimately Emmett told the police that he alone had beaten Langley to death with the brass lamp. Emmett was given Miranda warnings and he gave a full, taped confession. Emmett stated that he and Pittman decided to rob Langley after Langley refused to loan them more money to buy additional cocaine. Emmett stated that he struck Langley five or six times with the brass lamp, took Langley’s wallet, and left the motel to buy cocaine.

"Based upon the amount of blood and bruising of Langley’s brain tissue at the point of impact," the medical examiner opined that "Langley was not killed immediately by the first blow from the lamp, but might have been unconscious after the first blow was struck and may have suffered ‘brain death’ prior to actual death."

At the conclusion of the guilt phase of Emmett’s trial, Emmett was convicted by a jury of the capital murder and robbery of Langley. At the separate sentencing hearing, the Commonwealth sought the death penalty based upon Virginia’s statutory aggravating factors of future dangerousness and of vileness based upon aggravated battery and depravity of mind. In support of the future dangerousness factor, the prosecutor presented Emmett’s prior criminal history, to the extent it could be determined. The prosecutor was unable to establish why Emmett was incarcerated as a juvenile. Emmett’s juvenile criminal record had been destroyed pursuant to North Carolina procedure, and defense counsel intentionally avoided opening the door to Emmett’s extensive juvenile criminal history. The history presented consisted of juvenile convictions for felonious larceny and for assault and battery arising from an incident in which Emmett, while incarcerated in a maximum-security juvenile detention facility, rushed a guard and locked him in a closet in order to escape. In addition, the prosecutor presented evidence of an adult conviction for involuntary manslaughter arising from an incident in which Emmett, while driving a van in the wrong direction and under the influence of alcohol, struck and killed a motorcyclist. Testimony was presented that the drunken Emmett was smiling after the driver was killed and told an officer "‘that there was no need to worry about the man on the motorcycle. He was already dead, and that he, (Emmett) could do nothing to help him.’"

As noted by the state court, the evidence showed that Emmett lacked remorse for this earlier violent crime and for the current case of killing a coworker. Indeed, Emmett himself confessed that he killed Langley simply because it "just seemed right at the time." Such lack of regard for a human life speaks volumes on the issue of future dangerousness and leaves little doubt of its probability. In support of the vileness factor, the prosecutor highlighted to the jury the aggravated nature of the beating that Emmett inflicted upon his victim. As noted by the state court, Emmett’s actions demonstrated both aggravated battery and depravity of mind. Specifically, "the use of a blunt object to batter the skull of the victim repeatedly and with such force that blood spatters several feet from the victim is clearly both qualitatively and quantitatively more force than the minimum necessary to kill the victim." Additionally, "the evidence established that Emmett violently attacked a co-worker with whom he had apparently enjoyed an amicable relationship. The brutality of the crime amply demonstrates the depravity of mind involved in the murder of Langley."

Virginians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty

Christopher Scott Emmett

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Date of Birth: 8/18/1971

Sex: Male

Race: White

Entered the Row: November 2, 2001.

District: Danville

Conviction: Capital murder in the commission of robbery.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Christopher Scott Emmett was convicted in October 2001 of the April 26, 2001, capital murder and robbery of his co-worker, John Langley, in Danville, Virginia. Jurors heard a taped confession in which Emmett admitted striking Langley in the head with a lamp in the motel room they were sharing. In the tape, Emmett says he killed Langley, robbed him of $100, bought and smoked crack cocaine, and then called the police to report that something had happened to his roommate.

Emmett’s court-appointed defense lawyer failed to investigate and present mitigating evidence during the penalty phase that would have detailed Emmett’s wretched life as a child. Social service records and witnesses describe Emmett’s childhood home as extremely chaotic, abusive, and neglectful. Three of Emmett’s older siblings were kidnapped from school by their biological father, who was appalled by the conditions in the home. Sadly, because Emmett was too young to be attending school, he was left behind. Emmett’s juvenile probation officer, Butch Parker, states that Emmett’s “impoverished home situation, with emotional abuse and neglect, is very typical of what we see with children who become involved with the juvenile system.”[iii] Faye White, a state social worker who visited Emmett’s childhood home, states “[t]he situation in the Emmett home was one of the worst I have seen. It was the classic, text-book case of what you hear discussed as being the environments in which adults who have serious problems have been raised.”[iv]

During trial, defense counsel failed to take even the most basic steps to investigate Emmett’s childhood. Defense counsel never requested Emmett’s mental health records from court-ordered therapy he received as a child, never requested social service records documenting efforts to remove Emmett from his childhood home, never interviewed six of Emmett’s seven siblings, any paternal relatives, or Emmett’s daughter or her mother. As a result, virtually no mitigating evidence about Emmett’s childhood was presented to the jury to avoid a death sentence. On November 2, 2001, Emmett was sentenced to death.

In April 2000, the U.S. Supreme Court in Williams v. Taylor had ruled that a Virginia lawyer’s lack of diligence in unearthing evidence of childhood neglect and limited intellect demanded the verdict be overturned and the case be sent back to trial for a new sentencing hearing. In similar fashion three years later in Wiggins v. Smith, the U.S. Supreme Court rebuked the defense attorneys for not conducting a thorough investigation as they overturned a prior death sentence and sent the case back for a new hearing.

In a 2-1 decision early this year, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit rejected Emmett’s appeal, even though the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled time and again that defense counsel must thoroughly investigate a client’s childhood for mitigating evidence in convincing juries to spare their life. In his dissent, Circuit Judge Roger Gregory sharply noted that “[c]ounsel had failed to investigate adequately Emmett’s childhood, and counsel’s inadequate investigation prejudiced the sentencing phase of Emmett’s trial.”[v]

During state habeas corpus proceedings, the Supreme Court of Virginia unanimously ruled that “it is clear that trial counsel was ineffective for failing to object to the improper and incomplete verdict forms” that were given to Emmett’s jury.iv In a second order dated March 3, 2005, the Supreme Court of Virginia unanimously reaffirmed that “the representation provided to Emmett by his trial counsel ‘fell below an objective standard of reasonableness.’ [and that ‘r]easonably competent counsel would have objected to a verdict form that did not comport with the holding in Atkins and the requirements of [Virginia] Code.”v Despite finding that Emmett had not been competently represented at trial, the Supreme Court of Virginia refused to grant a new penalty trial.

An execution date of June 13, 2007 had been set by the Danville Circuit Court but was stayed just hours before by Gov. Kaine to allow for a possible review by the US Supreme Court. On Oct. 1, 2007 that court declined review but Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and John Paul Stevens issued a statement noting that except for Gov. Kaine’s intervention the Commonwealth of Virginia had attempted to cut short the ability of the court to review Emmett’s appeal.[vi]

Mr. Emmett has a Clemency Petition before Gov. Kaine and his attorneys have appealed to the US Supreme Court the 2-1 ruling of the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals denying a challenge to Virginia’s method of execution by lethal injection. On September 25, 2007 the Court agreed to consider the constitutionality of lethal injections in the case of two Kentucky death row inmates. Baze v Rees is to be argued in 2008 with a ruling expected by next summer.[vii]

Barring a further stay of execution due to the lethal injection challenge by either the US Supreme Court or Gov. Kaine, Mr. Emmett’s execution is set for 9:00 PM on Wednesday, October 17, 2007.

This page was last updated on October 10, 2007.

Emmett v. Commonwealth, 264 Va. 364, 569 S.E.2d 39 (Va. 2002) (Direct Appeal).

Defendant was convicted following jury trial in the Circuit Court, City of Danville, Joseph W. Milam, Jr., J., of capital murder in the commission of a robbery and was sentenced to death. On mandatory review of death sentence, the Supreme Court, Lawrence L. Koontz, Jr., J., held that: (1) having waived right to appeal, defendant could not assert that death sentence was improper merely on ground that there may have been reversible errors committed at trial; (2) testimony by victim-impact witnesses and minor misstatements by prosecutor during closing argument at penalty phase did not unduly influence or prejudice jury; (3) crime scene and autopsy photographs did not unduly prejudice jury or improperly inflame jurors' passions; (4) defendant's prior inconsistent statements were relevant to show consciousness of guilt and did not unduly influence jury; (5) evidence supported aggravating factors of future dangerousness and vileness; and (6) death sentence was not disproportionate. Affirmed.

KOONTZ, Justice.

In a bifurcated trial conducted pursuant to Code § 19.2-264.3, a jury convicted Christopher Scott Emmett of the capital murder of John Fenton Langley in the commission of robbery, Code § 18.2-31(4), and fixed Emmett's punishment at death. The trial court imposed the death sentence in accordance with the jury's verdict. Code § 17.1-313(A) mandates that we review the imposition of a death sentence.FN1

FN1. Emmett was also convicted of robbery and sentenced to life imprisonment for that crime. Emmett noted an appeal of his convictions, but on February 8, 2002 he filed a motion to withdraw that appeal. Pursuant to the February 22, 2002 order of this Court, the case was returned to the trial court with instructions to determine whether Emmett's decision to waive his appeal was voluntarily and intelligently made. At a hearing on March 4, 2002, the trial court accepted Emmett's voluntary waiver of his right to appeal, finding that he fully understood the consequences of doing so. On March 8, 2002, the trial court entered an order to that effect and returned the record to this Court in order that we might conduct the mandated review of Emmett's death sentence.

BACKGROUND

Weldon Roofing Company employed Emmett and Langley as laborers for its roofing crews. During late April 2001, both men were assigned to a project in the City of Danville and shared a room at a local motel where the roofing crew was staying. On the evening of April 26, 2001, Emmett, Langley, Michael Darryl Pittman, and other members of the roofing crew cooked dinner on a grill at the motel, played cards, and drank beer. During the course of the evening, Langley loaned money to Emmett and Pittman, who used the money to buy crack cocaine.

At approximately 11:00 p.m. that evening, Rainey Bell, another member of the roofing crew, heard a noise he described as “bang, bang” coming from the room Emmett and Langley shared. Shortly after midnight, Emmett went to the motel office and asked the clerk to call the police, saying that he had returned to his room, “seen blood and stuff ... and didn't know what had took place.”

The police arrived at the motel at 12:46 a.m. on April 27, 2001 and accompanied Emmett back to his room. There they discovered Langley's dead body lying face down on Langley's bed beneath a comforter. Blood spatters were found on the sheets and headboard of Langley's bed, on the wall behind it, and on the wall between the bathroom and Emmett's bed. A damaged brass lamp stained with Langley's blood was discovered beneath Langley's bed.

In his initial statement to police, Emmett denied killing Langley. He stated that he had returned to the room and gone to bed. Emmett claimed to have discovered the blood and Langley's body later that night when he got up to use the bathroom. Observing what appeared to be bloodstains on Emmett's personal effects, the police took possession of Emmett's boots and clothing with his permission. Emmett suggested that the blood might be his own because he had injured himself earlier in the week. Subsequent testing, however, revealed that Emmett's boots and clothing were stained with Langley's blood.

Later in the morning of April 27, Emmett voluntarily accompanied the police to the Danville police station. There he agreed to be fingerprinted and gave a sample of his blood. Emmett admitted to the police that he had been drinking and using cocaine on the previous evening. Over the course of the next several hours, Emmett related different versions of the events of the previous evening to the police. He first implicated Pittman as Langley's murderer, but ultimately Emmett told the police that he alone had beaten Langley to death with the brass lamp.

Emmett was given Miranda warnings and he gave a full, taped confession. Emmett stated that he and Pittman decided to rob Langley after Langley refused to loan them more money to buy additional cocaine. Emmett stated that he struck Langley five or six times with the brass lamp, took Langley's wallet, and left the motel to buy cocaine.

PROCEEDINGS

Emmett was indicted for capital murder and robbery. In the guilt-determination phase of a bifurcated jury trial beginning on October 9, 2001, the Commonwealth presented evidence in accord with the above-recited facts. In addition, the Commonwealth presented evidence from the medical examiner that based upon the amount of blood and bruising of the victim's brain tissue at the point of impact, Langley was not killed immediately by the first blow from the lamp. The medical examiner conceded, however, that Langley might have been unconscious after the first blow was struck and may have suffered “brain death” prior to actual death.

After the jury convicted Emmett of capital murder and robbery, during the penalty-determination phase of the trial, the Commonwealth presented evidence of Emmett's prior criminal history. This evidence included an account of an instance in which, while incarcerated in a maximum-security juvenile detention facility, Emmett participated in an escape that involved a guard being “rushed” and locked in a closet. In addition, the criminal history evidence showed that while driving a vehicle under the influence of alcohol, Emmett was involved in an accident in which the driver of a motorcycle was killed in 1996. After the accident Emmett said “that there was no need to worry about the man on the motorcycle. He was already dead, and that [Emmett] could do nothing to help him.” Emmett was convicted of involuntary manslaughter.

The Commonwealth also presented extensive victim-impact testimony from members of Langley's family. Emmett objected to various statements made by the victim-impact witnesses who appeared to urge the imposition of the death penalty. The trial court sustained these objections and directed the jury to disregard the statements. Emmett presented evidence in mitigation from his mother, sister, and a family friend. Emmett's mother testified that Emmett's father had been abusive, and “he just never took care of his family.” Both Emmett's mother and sister testified that Emmett had become withdrawn in the months prior to Langley's murder. The friend described Emmett as “a caring person” who had helped her disabled husband with yard work and had assisted her in caring for her son when he was injured and unable to walk.

The jury returned its verdict imposing the death sentence based upon both the statutory aggravating factors of future dangerousness and vileness. Following consideration of a presentence report, the trial court imposed the jury's sentence of death.

DISCUSSION

As we have previously noted, Emmett has voluntarily waived his right to appeal his convictions and, thus, to have the proceedings of his trial reviewed for reversible error. The Commonwealth contends that this waiver bars Emmett from asserting that the death sentence was imposed as a result of passion, prejudice, or other arbitrary factors because certain evidence was erroneously admitted or that certain remarks by the Commonwealth's Attorney during the penalty-phase closing argument were improper and should have been stricken from the record.

We agree with the Commonwealth that, having waived his right of appeal, Emmett may not assert that his sentence of death is improper merely on the ground that there may have been reversible errors committed in his trial. We consistently adhere to the contemporaneous objection requirement of our Rule 5:25 and the further requirement of Rule 5:27 that trial error must be the subject of an assignment of error. See, e.g., Overton v. Commonwealth, 260 Va. 599, 604, 539 S.E.2d 421, 423 (2000) (applying Rule 5:25 to failure to object to victim impact testimony or introduction of photographs in Code § 17.1-313(C) review of death sentence); George v. Commonwealth, 242 Va. 264, 284, 411 S.E.2d 12, 23-24 (1991), cert. denied, 503 U.S. 973, 112 S.Ct. 1591, 118 L.Ed.2d 308 (1992) (consolidation of charges not the subject of assignment of error not considered in passion and prejudice review); see also Rule 5:17(c). Emmett's waiver of appeal implicates both of these procedural requirements for our review of potential trial errors, and we decline to create an exception to these requirements.

However, “[t]he review process mandated by Code § 17.1-313(C) cannot be waived. Rather, the purpose of the review process is to assure the fair and proper application of the death penalty statutes in this Commonwealth and to instill public confidence in the administration of justice.” Akers v. Commonwealth, 260 Va. 358, 364, 535 S.E.2d 674, 677 (2000).

The review process mandated by Code § 17.1-313(C)(1) is meaningless without the recognition that the erroneous admission of some evidence or some other error in an incident of trial might result in a prejudicial verdict. Indeed, the import of the review mandated by Code § 17.1-313(C)(1) is that a sentence of death may be imposed erroneously as the result of passion, prejudice, or other arbitrary factors even where there is, or could be, no finding of reversible error in the trial proceedings. Accordingly, in this case, while we will not consider the merits of any assertion that evidence was improperly admitted or that the Commonwealth's Attorney made improper statements, we will nonetheless consider the potential impact such evidence and statements may have had on the jury's decision to impose the death sentence.

Emmett makes several arguments in support of the contention that the sentence of death was imposed upon him as the result of passion, prejudice, or other arbitrary factors. Chiefly, he points to the emotionally charged testimony of the victim's family members and their statements that appeared to urge the imposition of the death penalty. However, each time a victim-impact witness's testimony broached this subject, Emmett objected, and the trial court instructed the jury to disregard the witness's statement. A jury is presumed to follow the instructions of the trial court. Weeks v. Angelone, 528 U.S. 225, 234, 120 S.Ct. 727, 145 L.Ed.2d 727 (2000); LeVasseur v. Commonwealth, 225 Va. 564, 589, 304 S.E.2d 644, 657 (1983), cert. denied, 464 U.S. 1063, 104 S.Ct. 744, 79 L.Ed.2d 202 (1984). Accordingly, we do not believe that this testimony unduly influenced or prejudiced the jury in its determination whether to impose the death sentence.

In further support of his assertion that his death sentence was imposed as a result of passion or prejudice, Emmett points to misstatements by the Commonwealth's Attorney during his closing argument in the penalty-determination phase of the trial to the effect that any one of the blows to the victim could have proven fatal, and a reference to Emmett's prior conduct as having occurred in a prison rather than as in a maximum-security juvenile detention facility. He further contends that the Commonwealth's Attorney intended to inflame the jurors' passions by telling them that “nobody is safe from this guy” and that Emmett is dangerous because “[h]e has nothing to lose.”

We agree that the Commonwealth's Attorney mischaracterized the medical examiner's testimony and that he inaccurately referred to the juvenile detention facility as a prison. However, these misstatements were minor and not unduly prejudicial in light of the trial court's instruction to the jury that the argument of counsel was not evidence. Reviewing the Commonwealth's Attorney's argument as a whole, we do not believe that any of the instances cited by Emmett, individually or cumulatively, created an atmosphere of passion or prejudice that influenced the jury's sentencing decision. See Burns v. Commonwealth, 261 Va. 307, 344, 541 S.E.2d 872, 896, cert. denied, 534 U.S. 1043, 122 S.Ct. 621, 151 L.Ed.2d 542 (2001).

Emmett further contends that crime scene and autopsy photographs admitted into evidence were unduly gruesome and would have inflamed the jury's passion in favor of imposing the death sentence. While undoubtedly shocking and gruesome, photographs that accurately depict the crime scene and the condition of the victim are relevant to show motive, intent, method, malice, premeditation, and the atrociousness of the crimes. Payne v. Commonwealth, 257 Va. 216, 223, 509 S.E.2d 293, 297 (1999). They also are relevant to show the likelihood of Emmett's future dangerousness. Id. Having reviewed these exhibits, we cannot say that they would have unduly prejudiced the jury or improperly inflamed the jurors' passions so as to taint their decision in favor of imposing the death sentence.

Emmett also contends that the admission of his prior inconsistent statements to the police denying responsibility for the murder and attempting to shift the blame to Pittman was unduly prejudicial. These statements were clearly relevant to show Emmett's consciousness of guilt. See Rollston v. Commonwealth, 11 Va.App. 535, 548, 399 S.E.2d 823, 831 (1991) (“A defendant's false statements are probative to show he is trying to conceal his guilt, and thus is evidence of his guilt”); see also Carter v. Commonwealth, 223 Va. 528, 532, 290 S.E.2d 865, 867 (1982) (holding that trier-of-fact need not believe a defendant's explanation of events and may infer consciousness of guilt from his false testimony). There is no indication in the record that the Commonwealth introduced these statements for any improper purpose, and we perceive nothing in the record to support the suggestion that the jury was unduly influenced by this evidence in considering whether to impose the death sentence.

Finally, Emmett asserts that the evidence was insufficient for the jury to have found that either aggravating factor necessary under Code § 19.2-264.2 to the imposition of a death sentence was present in this case and, thus, that the sentence of death must have resulted from passion, prejudice, or other arbitrary factors. There is no merit to this assertion.

With regard to the future dangerousness predicate, the Commonwealth introduced evidence of Emmett's prior participation in an escape from a maximum-security juvenile detention facility, which included an assault on a guard, and his subsequent conviction as an adult for involuntary manslaughter. The evidence also showed that Emmett lacked remorse for this earlier violent crime and for the instant killing of a co-worker. Indeed, Emmett himself confessed that he killed Langley simply because it “just seemed right at the time.” Such lack of regard for a human life speaks volumes on the issue of future dangerousness and leaves little doubt of its probability.

With regard to the statutory vileness predicate, the Commonwealth's evidence supports two of the alternative circumstances that can support a finding of vileness, i.e., aggravated battery and depravity of mind. See Goins v. Commonwealth, 251 Va. 442, 468, 470 S.E.2d 114, 131, cert. denied, 519 U.S. 887, 117 S.Ct. 222, 136 L.Ed.2d 154 (1996) (proof of any one of these statutory components will support a finding of vileness). Aggravated battery is “a battery which, qualitatively and quantitatively, is more culpable than the minimum necessary to accomplish an act of murder.” Smith v. Commonwealth, 219 Va. 455, 478, 248 S.E.2d 135, 149 (1978), cert. denied, 441 U.S. 967, 99 S.Ct. 2419, 60 L.Ed.2d 1074 (1979). The use of a blunt object to batter the skull of the victim repeatedly and with such force that blood spatters several feet from the victim is clearly both qualitatively and quantitatively more force than the minimum necessary to kill the victim.

Emmett's actions also established depravity of mind, that is, a “degree of moral turpitude and psychical debasement surpassing that inherent in the definition of ordinary legal malice and premeditation.” Id. The evidence established that Emmett violently attacked a co-worker with whom he had apparently enjoyed an amicable relationship. The brutality of the crime amply demonstrates the depravity of mind involved in the murder of Langley. Cf. Akers, 260 Va. at 364, 535 S.E.2d at 677.

Pursuant to Code § 17.1-313(C)(2) we must also determine whether Emmett's death sentence is “excessive or disproportionate to the penalty imposed in similar cases, considering both the crime and the defendant.” Emmett first notes that Code § 17.1-313(E) directs this Court to consider “such records as are available as a guide in determining whether the sentence imposed in the case under review is excessive.” He asserts that because records of unappealed capital murder convictions in which a sentence of life imprisonment was imposed are not collected for consideration during our proportionality review, the review is inadequate because the comparison base is skewed in favor of the death penalty. We have previously rejected this argument and determined that the statute does not require us to collect data from unappealed cases. Bailey v. Commonwealth, 259 Va. 723, 741-42, 529 S.E.2d 570, 580-81, cert. denied, 531 U.S. 995, 121 S.Ct. 488, 148 L.Ed.2d 460 (2000). In Bailey, we held that Code § 17.1-313(E) grants this Court the discretion to determine what records to accumulate for our review process and that, “so long as the methods employed assure that the death sentence is not disproportionate to the penalty generally imposed for comparable crimes, due process will be satisfied and the defendant's constitutional rights protected.” Id.

Emmett further contends that sentencing bodies in the Commonwealth generally have not imposed the death penalty in capital murder cases where the predicate crime was robbery. In support of this contention, Emmett asserts that a review of the 50 most recent capital murder appeals in this Court would reveal that 17 of the 26 convictions where robbery was the gradation offense resulted in life sentences. Moreover, he contends that the facts of the cases in which life sentences were imposed are comparable or similar to the facts involved in his own crime or more egregious.

Our proportionality analysis encompasses all capital murder cases presented to this Court for review and is not limited to cases selectively chosen by a defendant. “The test is not whether a jury may have declined to recommend the death penalty in a particular case but whether generally juries in this jurisdiction impose the death sentence for conduct similar to that of the defendant.” Stamper v. Commonwealth, 220 Va. 260, 283-84, 257 S.E.2d 808, 824 (1979), cert. denied, 445 U.S. 972, 100 S.Ct. 1666, 64 L.Ed.2d 249 (1980). Additionally, the question of proportionality does not turn on whether a given capital murder case “equal[s] in horror the worst possible scenario yet encountered.” Turner v. Commonwealth, 234 Va. 543, 556, 364 S.E.2d 483, 490, cert. denied, 486 U.S. 1017, 108 S.Ct. 1756, 100 L.Ed.2d 218 (1988).

“The purpose of our comparative review is to reach a reasoned judgment regarding what cases justify the imposition of the death penalty.” Orbe v. Commonwealth, 258 Va. 390, 405, 519 S.E.2d 808, 817 (1999), cert. denied, 529 U.S. 1113, 120 S.Ct. 1970, 146 L.Ed.2d 800 (2000). Although we cannot insure that “complete symmetry” exists among all death penalty cases, “our review does enable us to identify and invalidate a death sentence that is ‘excessive or disproportionate to the penalty imposed in similar cases.’ ” Id. (quoting Code § 17.1-313(C)(2)); see also Akers, 260 Va. at 365, 535 S.E.2d at 677. The purpose of performing a comparative review is not to search for proof that a defendant's death sentence is perfectly symmetrical with others, but to identify and invalidate a death sentence that is aberrant. Orbe, 258 Va. at 405, 519 S.E.2d at 817.

Emmett's assertion that a raw statistical analysis of the most recent capital murder cases reviewed by this Court involving the gradation offense of robbery compels the conclusion that a sentence of death would be inappropriate in his case represents an overly simplistic and unwarranted application of the proportionality review process. We do include consideration of the predicate gradation offense or status of the defendant or victim that elevates a murder to a capital crime in narrowing our focus to determine proportionality. However, we also take into account other factors including, but not limited to, the method of killing, the motive for the crime, the relationship between the defendant and the victim, whether there was premeditation, and the aggravating factors found by the sentencing body. In doing so, we fulfill the statutory mandate to consider “both the crime and the defendant.” By merely considering the most recent capital murder cases appealed to this Court where the gradation offense was robbery, Emmett has not based his argument on a probative selection of prior cases, but on an incidental ratio that has little or no bearing on the crime or the defendant in this case.

Having conducted the appropriate proportionality review, we find that other sentencing bodies generally impose the death penalty for comparable or similar crimes. See, e.g., Akers, 260 Va. 358, 535 S.E.2d 674; Graham v. Commonwealth, 250 Va. 79, 459 S.E.2d 97 (1995), cert. denied, 516 U.S. 997, 116 S.Ct. 535, 133 L.Ed.2d 440 (1995); Watkins v. Commonwealth, 238 Va. 341, 385 S.E.2d 50 (1989), cert. denied, 494 U.S. 1074, 110 S.Ct. 1797, 108 L.Ed.2d 798 (1990); Stout v. Commonwealth, 237 Va. 126, 376 S.E.2d 288, cert. denied, 492 U.S. 925, 109 S.Ct. 3263, 106 L.Ed.2d 609 (1989); Watkins v. Commonwealth, 229 Va. 469, 331 S.E.2d 422 (1985), cert. denied, 475 U.S. 1099, 106 S.Ct. 1503, 89 L.Ed.2d 903 (1986); Poyner v. Commonwealth, 229 Va. 401, 329 S.E.2d 815, cert. denied, 474 U.S. 865, 106 S.Ct. 189, 88 L.Ed.2d 158 (1985). Accordingly, we hold that the sentence of death imposed in this case was not disproportionate.

CONCLUSION

Having reviewed the sentence of death pursuant to Code § 17.1-313, we decline to commute that sentence. Accordingly, we will affirm the judgment of the trial court.FN2

FN2. The United States Supreme Court in Atkins v. Virginia, 536U.S. 304, ---- 122 S.Ct. 2242, 2252, 153 L.Ed.2d 335 (2002), recently held that the execution of mentally retarded persons violates the Eighth Amendment's prohibition against cruel and unusual punishments. The Court did not establish an express standard for determining when an individual would be considered mentally retarded and left to the States the task of developing appropriate ways to enforce this constitutional restriction upon executions. Atkins, 536 U.S. at ----, 122 S.Ct. at 2250. The General Assembly has not had the opportunity to address this matter following the decision in Atkins.At trial, Emmett did not assert that he is mentally retarded. Moreover, our review of the record reveals nothing that even suggests that he is mentally retarded. Emmett received a high school equivalency diploma, attended a community college, and was regularly employed during his adult life prior to committing the murder in question. Accordingly, we conclude that Emmett does not suffer from any mental retardation that would constitutionally restrict the imposition of the death sentence in this case. Affirmed

Emmett v. Warden of Sussex I State Prison, 269 Va. 164, 609 S.E.2d 602 (Va. 2005) (Stae Habeas)

Background: Following affirmance of his convictions for capital murder and robbery on direct appeal, 264 Va. 364, 569 S.E.2d 39, petitioner sought habeas relief. The Supreme Court issued order finding that defense counsel's failure to object to incomplete verdict form was deficient, but that petitioner had suffered no prejudice thereby. Warden filed petition for rehearing.

Holdings: Upon grant of petition for rehearing, the Supreme Court held that:

(1) defense counsel's failure to object to incomplete penalty phase verdict form constituted deficient performance;

(2) defense counsel's deficient performance in failing to object to incomplete penalty phase verdict form did not constitute structural error; and

(3) defense counsel's deficient performance in failing to object to incomplete penalty phase verdict form did not prejudice petitioner. Petition dismissed.

Emmett v. Kelly, 474 F.3d 154 (4th Cir. 2007) (Habeas).

Background: Following affirmance, 569 S.E.2d 39, of state conviction for capital murder and robbery and sentence of death, and exhaustion of state postconviction remedies, state prison inmate sought federal habeas relief. The United States District Court for the Western District of Virginia, Moon, J., denied petition, and inmate appealed.

Holdings: The Court of Appeals, Traxler, Circuit Judge, held that:

(1) defense attorney's performance in penalty phase was not rendered deficient by failure to interview all of defendant's siblings or to request record from court-ordered juvenile counseling;

(2) even assuming that defense attorney's actions constituted deficient performance, defendant was not prejudiced; and

(3) defense attorney also did not perform deficiently during penalty phase by failing to present expert testimony concerning defendant's cocaine/alcohol intoxication. Affirmed.

Emmett v. Johnson, --- F.3d ----, 2008 WL 2736034 (4th Cir. 2008) (Sec. 1983).

Background: Condemned inmate brought § 1983 action against state correctional officials, seeking equitable and injunctive relief for alleged violations, threatened violations, or anticipated violations of his right to be free from cruel and unusual punishment. The United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, Henry E. Hudson, J., 511 F.Supp.2d 634, granted summary judgment in favor of defendants. Inmate appealed.

Holding: The Court of Appeals, Traxler, Circuit Judge, held that state's lethal injunction protocol did not constitute cruel and unusual punishment. Affirmed.