Executed August 12, 2008 06:27 p.m. CDT by Lethal Injection in Texas

19th murderer executed in U.S. in 2008

1118th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

7th murderer executed in Texas in 2008

412th murderer executed in Texas since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

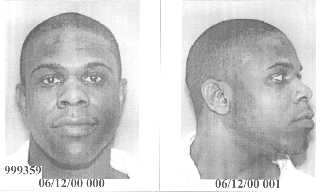

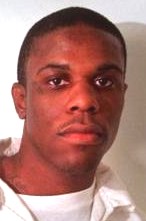

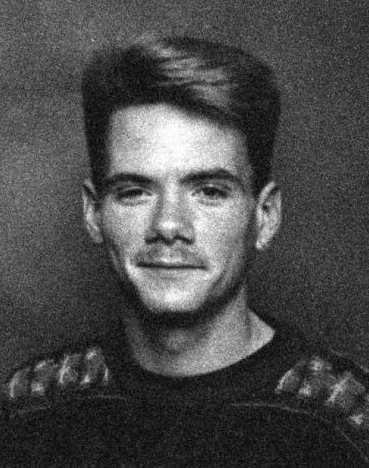

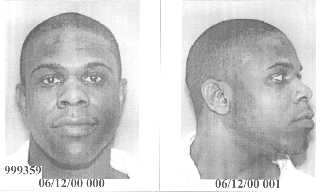

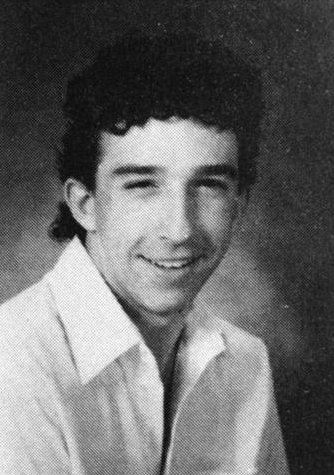

Leon David Dorsey IV B / M / 18 - 32 |

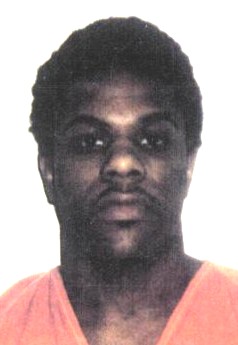

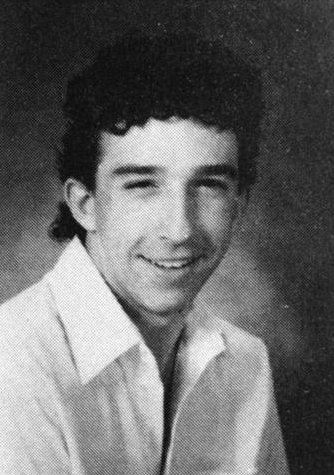

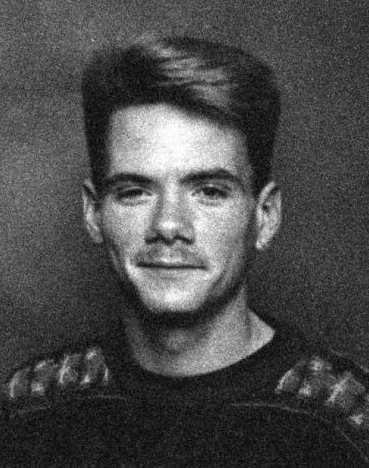

James Armstrong W / M / 26 Brad Lindsey W / M / 20 |

Five months after committing the Blockbuster murders, Dorsey killed 51 year old Hyon Suk Chon, during a convenience store robbery in Ennis, Texas. Dorsey pled guilty to the murder and was sentenced to sixty years in prison. He was in prison serving time for this murder when he confessed to the Blockbuster murders.

Citations:

Dorsey v. Quarterman, 494 F.3d 527 (5th Cir. 2007) (Habeas).

Final/Special Meal:

None.

Final Words:

“I love all y’all, I forgive all y’all, and I’ll see y’all when you get there. Do what you’re gonna do.”

Internet Sources:

Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Executed Offenders (Leon Dorsey)

Inmate: Dorsey, Leon David IVPrior Prison Record: Dorsey had no prior criminal record at the time this offense was committed. However, after this offense was committed and prior to being convicted for this offense, Dorsey committed Murder with a Deadly Weapon and Unauthorized Use of a Motor Vehicle in Ellis County (involved Dorsey and one co-defendant enter a food store, fatally shooting a 51 year old Oriental female, then fleeing the scene with an unknown amount of money). Dorsey received a 60 year sentence for that offense and was serving that sentence when he was convicted of Capital Murder and sentenced to death for the current offense.

Summary of incident: On 4/4/1994 during the night in Dallas, Dorsey entered a video store and used a 9 millimeter pistol to rob and kill a 26 year old white male employee and a 20 year old white male employee. He forced them into the back office, where he shot and killed them. He took $392 from the business.

Tuesday, August 5, 2008

Media Advisory: Leon David Dorsey Scheduled For Execution

AUSTIN – Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott offers the following information on Leon David Dorsey, who is scheduled to be executed after 6 p.m. Tuesday, August 12, 2008. In May 2000, Leon David Dorsey was convicted of capital murder and sentenced to death for the robbery and slaying of James Lloyd Armstrong at a video store in Dallas.

FACTS OF THE CRIME

Two employees at a Blockbuster Video store in Dallas were robbed and murdered around midnight on April 4, 1994. Employee James Armstrong was shot twice and employee Brad Lindsey was shot once in the back. The robber took several hundred dollars from the business. The in-store video camera recorded the crime and shows that the killer was a black male with short hair.

Later that day, Dorsey admitted committing the robbery and murders to his girlfriend and to an acquaintance. Later that week, the girlfriend reported Dorsey’s admissions to the police. At the time, police erroneously believed that Dorsey was too tall to be the killer, and he was not charged with the crime, which remained unsolved until the case was reopened in 1998. During the 1998 investigation, police sent the videotape of the robbery-murder to the F.B.I. for an analysis of the robber’s height. Based on the new estimate of the perpetrator's height and accurate information about Dorsey’s height, police questioned Dorsey again, and he confessed

CRIMINAL HISTORY AND PUNISHMENT EVIDENCE

Five months after committing the Blockbuster killings, Dorsey killed a convenience store clerk during a robbery in Ennis, Texas. Dorsey pled guilty to the murder and was sentenced to sixty years in prison.

While in prison, Dorsey attempted to stab another inmate. During an interview with the Dallas Morning News, Dorsey admitted to “possibly” killing as many as nine people, “more or less.”

At fourteen, Dorsey took a gun to school and discharged it in a classroom. At fifteen, Dorsey lived on an Air Force base and committed several property crimes, including a residential robbery, a theft from a vehicle, and a theft of some items from lockers at the base gymnasium. When police investigated and found the stolen items at Dorsey’s home, they also discovered 20 to 25 bullet holes in the basement wall of his house and numerous spent shells.

At sixteen, Dorsey fired a gun at a young couple in another car and verbally threatened to kill them.

At eighteen, five months after the double slaying at the Blockbuster store, Dorsey was arrested for unauthorized use of a motor vehicle. He was convicted, and his sentence was probated.

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

Dorsey was convicted of capital murder and sentenced to death in May 2000. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed Dorsey’s conviction and sentence on October 2, 2002. The U.S. Supreme Court denied Dorsey’s petition for writ of certiorari on June 23, 2003. Dorsey filed a petition for state writ of habeas corpus on May 6, 2002. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals adopted the trial court’s findings and denied relief on February 18, 2004. Dorsey filed his federal habeas petition on December 17, 2004. On July 31, 2006, the federal district court denied Dorsey’s petition for federal habeas relief. The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the federal district court’s denial of federal habeas relief on July 30, 2007. The U.S. Supreme Court denied Dorsey’s petition for certiorari review on February 25, 2008.

Texas Execution Information Center by David Carson.

Leon David Dorsey IV, 32, was executed by lethal injection on 12 August 2008 in Huntsville, Texas for killing two store employees during a robbery.

On 4 April 1994, Dorsey, then 18, entered a Dallas Blockbuster video store around midnight. Using a 9 millimeter pistol, Dorsey forced two employees, James Armstrong, 26, and Brad Lindsey, 20, to give him the money from the cash register. He then forced them into the back office. When Armstrong had trouble opening the safe, Dorsey shot him in the side. Lindsey was shot in the back when he tried to run away. Dorsey then shot Armstrong again. Both victims died. Dorsey stole $392 from the business. The robbery and first two gunshots were recorded on in-store video cameras, as well as a visit earlier that day when Dorsey came to check out the store.

Dorsey later admitted the crime to his girlfriend, who contacted the police. Investigators questioned Dorsey, but after they reviewed the videotape of the crime, they concluded that he was too tall to be the killer, so he was not charged.

Five months later, Dorsey killed 51-year-old Hyon Suk Chon, a female convenience store clerk, during a robbery in Ennis. He pleaded guilty to murder with a deadly weapon and was sentenced to 60 years in prison.

In 1998, while Dorsey was serving his sentence, the Dallas video store case was reopened by a cold case unit. Police sent the videotape of the crime to the Federal Bureau of Investigation for an analysis of the perpetrator's height. Based on the FBI's height estimate, police questioned Dorsey again, and he confessed.

Before his capital murder trial began, Dorsey was interviewed from death row about the murders. "They're dead," he said, "That's over and done with. I could have came in here and been, 'Oh, I'm sorry, I'm so bad.' But I don't feel like that. That's not being honest with myself." Dorsey also said that the families of his victims should treat the loss of their loved ones like losing money in a craps game, rather than dwelling on it. The interview was used at Dorsey's trial as evidence that he should be sentenced to death.

In the pre-trial interview, Dorsey, who called himself "Pistol Pete", said that when he was ten years old and in kindergarten, he stabbed a pee-wee football teammate and tried to burn down his babysitter's house. At age 14, he took a gun to school and discharged it in a classroom. At 16, he fired a gun at a couple in another car and threatened to kill them. He also had a juvenile record of property theft and unauthorized use of a motor vehicle. "I've done cut folks; I've done stabbed folks; I've killed folks," he said, "but it don't bother me."

A jury convicted Dorsey of capital murder in May 2000 and sentenced him to death. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the conviction and sentence in October 2002. All of his subsequent appeals in state and federal court were denied.

Dallas county prosecutor Jason January did not blame the police for deciding not to charge Dorsey after the first murder. He said that the technology at the time was not advanced enough. "You hate to see that," he said, "knowing that potentially if the technology had been as good when the crime was committed, someone else would not have been killed."

In his eight years on death row, Dorsey was written up at least 95 times for disciplinary infractions, including the 2004 stabbing of a corrections officer 14 times in the back with an 8½-inch shank. The officer's body armor protected him from serious injury. Authorities found another shank in Dorsey's cell less two weeks before he was executed.

Dorsey was not available for media interviews while on death row because of his disciplinary record and his threats of violence. Prison officials were prepared to use force to take him to the execution chamber, but Texas Department of Criminal Justice spokeswoman Michelle Lyons said that Dorsey did not put up a fight, and force was not used.

At his execution, Dorsey acknowledged his sister, who watched from a viewing room, but did not acknowledge the victims' witnesses. "I love y'all. I forgive y'all. See y'all when you get there," he said in his last statement. "Do what you're going to do." The lethal injection was then started. He was pronounced dead at 6:27 p.m.

"Texas executes inmate convicted of double slaying," by Michael Graczyk. (AP Aug. 12, 2008)

HUNTSVILLE, Texas — A twice-convicted killer with a history of violence that continued even after he was sent to death row was executed Tuesday for gunning down two video store workers during a 1994 robbery.

"I love all y'all. I forgive all y'all. See y'all when you get there," Leon David Dorsey IV said in his final statement. "Do what you're going to do." Dorsey, 32, acknowledged his sister when witnesses filed in but didn't direct any comments to the relatives of his victims.

He was pronounced dead at 6:27 p.m. CDT, nine minutes after the lethal drugs began to flow.

The U.S. Supreme Court earlier this year upheld his conviction and death sentence and no late appeals were filed to try to block Dorsey's lethal injection.

Prison records showed that since Dorsey arrived on death row eight years ago, he's had at least 95 disciplinary cases, including a 2004 attack where he used an 8 1/2-inch shank to stab an officer 14 times in the back. The officer's body armor prevented serious injuries. Less than two weeks ago, authorities recovered another shank from his cell. His threats of violence kept prison officials from making him available for media interviews as his execution date approached, but prison officials said he offered no resistance as he was led to the death chamber.

"He's mean," said Toby Shook, a former Dallas County assistant district attorney who prosecuted Dorsey for capital murder. He called Dorsey a "true psychopath." "He's very smart, very organized. ... He just was always headed in this direction," Shook said. "Every day he was looking to hurt someone. It was the only satisfaction he got in life."

Dorsey was already serving a 60-year prison sentence after pleading guilty to killing a woman during a convenience store robbery when a Dallas police cold case squad gathered enough evidence to tie him to the unsolved shooting deaths of James Armstrong, 26, and Brad Lindsey, 20, at a Blockbuster Video store in East Dallas where they worked.

Evidence showed Dorsey, who called himself "Pistol Pete," cased the place on Easter Sunday night in 1994, then returned after midnight to steal $392 from a cash register. Then 18, Dorsey shot the workers when Armstrong had difficulty opening a safe at gunpoint and Lindsey tried to run. Most of the crime was recorded on security cameras in the store.

"Viewing Dorsey's execution will not bring any happiness, but we've lived to see justice for James 14 years later and today we pray for Dorsey's father," Armstrong's parents, Gerald and Nanci Armstrong, said in a statement released after the execution. Nanci Armstrong said she struggled with forgiving Dorsey "but I knew that I had to forgive him."

Dorsey initially was questioned about the slayings after his girlfriend reported to police that he had admitted the shootings to her. But police initially believed he was too tall, based on images from the security tape. When the case was reopened in 1998, Dallas authorities had the tape analyzed by the FBI and determined Dorsey could have been the gunman.

The Ennis robbery, in which 51-year-old convenience store manager Hyon Suk Chon was killed, occurred five months after the video store killings. "You hate to see that, knowing that potentially if the technology had been as good when the crime was committed, someone else would not have been killed," said Jason January, who prosecuted the capital case with Shook.

Some of the evidence prosecutors used in their push for the death penalty was in an interview he gave to a reporter while he was awaiting trial. "I've done cut folks; I've done stabbed folks; I've killed folks," he told The Dallas Morning News. "But it don't bother me."

Dorsey at age 12 moved to Waxahachie to live with his grandparents after he was booted from Germany, where his mother was stationed in the Air Force. Records show when he was 14 he took a gun to school and fired it. At 16, he fired at a couple driving in a car. "He'd walk down the street with a sawed-off shotgun tied to his arm and with a coat on and then just throw it open — just to see the reaction of people," Shook said. "He's a piece of work."

Dorsey was the seventh prisoner executed this year in the nation's most active death penalty state and the first of two inmates scheduled to die this week. Two more are to die next week.

"Dorsey executed for 1994 Blockbuster murders," by Kristin Edwards. (August 12, 2008)

Leon David Dorsey, who was convicted of the April 4, 1994, shooting deaths of a 26-year-old male and a 20-year-old male at a Dallas Blockbuster video was executed Tuesday. Dorsey was pronounced dead at 6:27 p.m. after receiving a lethal injection at the Texas Department of Criminal Justice Walls Unit. Dorsey is the seventh death row inmate to be executed in Texas this year since the lethal injection has been reinstated.

According to Michelle Lyons, TDCJ public information officer, Dorsey had recently made threats to harm a correctional officer prior to his execution, but fortunately did not follow through with his threats. “Leon Dorsey was executed Tuesday without putting up a fight,” she said. “He did not have to be forcibly taken into the execution chamber, and the entire execution was carried out without incident.”

During his very brief last statement, Dorsey did not acknowledge Gerald and Nanci Armstrong or Joan Coleman, the parents of Dorsey’s two victims in the Blockbuster shootings, James Armstrong and Brad Lindsey. His only words before his last statement – “Hey, sis,” – were directed to his sister, Tameka Finklea. “I love all y’all, I forgive all y’all, and I’ll see y’all when you get there,” he said. “Do what you’re gonna do.”

While Joan Coleman did not make a formal statement following the execution, Gerald and Nancy Armstrong released a letter to the media which addressed their feelings about Dorsey’s execution. “Losing James has been and always will be painful; it doesn’t get any easier, but we’ve gotten stronger,” the letter read. “Viewing Dorsey’s execution will not bring any happiness, but we’ve lived to see justice for James 14 years later and today we pray for Dorsey’s father.”

In a segment of the letter which appears to have been written by Nanci Armstrong, more detail is offered regarding her feelings about Dorsey. “While Gerald has said it was different for him, I have struggled with forgiving Dorsey for killing our son,” she said. “Perhaps Dorsey is as evil as Charles Manson and has no remorse, but I knew that I had to forgive him. “I could do it in my head, but not in my heart.”

According to information released by the Texas Attorney General’s office, James Armstrong and Brad Lindsey were shot and killed at a Dallas Blockbuster, and the person who shot them also stole $392 from the business.

While Dorsey actually admitted committing the robbery and murders to his girlfriend and to an acquaintance, Dorsey was not immediately charged with the crime. Dorsey confessed to the 1994 murders in 1998, when new evidence led police to re-question him.

Five months after committing the Blockbuster killings, but before he had been charged with them, Dorsey killed a convenience store clerk during a robbery in Ennis, Texas. Dorsey pleaded guilty to the murder and was sentenced to 60 years in prison.

"Texas executes man for 1994 double slaying." (Tue Aug 12, 2008 8:29pm)

DALLAS (Reuters) - Texas executed a man by lethal injection on Tuesday for a 1994 double slaying during an armed robbery, the seventh convict put to death this year by America's most active death penalty state.

Leon Dorsey, 32, was condemned for the 1994 murders in Dallas of two video store employees, whom he shot to death in a robbery that netted him $392. He was serving time for another murder when he was convicted and sentenced to die in 2000 for these crimes, which at the time shocked the city of Dallas.

The Dallas Morning News said on Tuesday that Dorsey, dubbed "Pistol Pete" on the street, was one of the "meanest men on Texas' death row" with a long history of infractions including assaulting and threatening to injure prison staff.

In his last statement while strapped to the gurney in the state's death chamber in Huntsville, he said "Yeah, I love ya'll, I forgive ya'll." He had no last meal request.

Texas executes more prisoners than any other U.S. state. Dorsey was the 412th inmate put to death in Texas since 1982, when it resumed executions six years after the U.S. Supreme Court reinstated capital punishment.

Around midnight on April 4, 1994, two employees at a Blockbuster Video store in Dallas at the Casa Linda Plaza Shopping Center were robbed of only $392 and murdered. The in-store video camera recorded the crime and shows that the perpetrator was a black male with short hair. The two employees were forced into a back room, where the video shows them speaking briefly before being killed. Brad Lindsey was shot once in the back; employee James Armstrong was shot twice.

Later that day, Leon David Dorsey IV, a Waxahachie gang member, admitted committing the robbery and murders to his girlfriend, Arrietta Washington, and to an acquaintance, Antwan Hamilton. In an interview with a newspaper reporter, Dorsey stated that he had burned the jacket he had worn that night and would not disclose the location of the murder weapon. Washington braided extensions into Dorsey's hair as a disguise.

Later that week, she reported Dorsey's admissions to the police. The police interviewed Dorsey, but he denied any involvement. At the time, police erroneously believed that Dorsey was too tall to be the perpetrator, and he was not charged with the crime, which remained unsolved until the case was reopened by a veteran detective in 1998. During the 1998 investigation, police sent the videotape of the robbery-murder to the FBI for an analysis of the perpetrator's height. Based on the new estimate of the perpetrator's height and accurate information about Dorsey's height, police questioned Dorsey again, and he confessed.

While awaiting trial, Dorsey again confessed to this offense during an interview with Dallas Morning News reporter Jason Sickles. In the interview, Dorsey blamed the victims for their deaths and said they could be alive today. "But they didn't use their choice wisely," he said. Dorsey told the reporter that he feels no remorse for killing James Armstrong and Brad Lindsey. He said their families should not dwell on their deaths, comparing it to losing $1,000 in a craps game. "They're dead. That's over and done with," he said. "Why are you going to sit there and worry yourself about that? Move on. I could have came in here and been, 'Oh, I'm sorry, I'm so bad.' But I don't feel like that. That's not being honest with myself."

Dorsey told Mr. Sickles that he was drunk and high when he went to the Blockbuster in search of cash and that one of the men probably angered him, but he doesn't remember who or how. "One of them had to be bumping me or talking sh.t," he said. "One of them did, or I wouldn't have did it like that. I killed the second person because the first person fu.ked up. I had a tendency to dehumanize a person in a situation," Dorsey said. "If I was robbing you, and you studded up, I could fu.k you up and say that was business. If you cooperated, you could walk away from it easily."

A week before trial, Dorsey admitted committing the murders to a fellow inmate. Dorsey, whose nickname was "Pistol Pete", also sent a letter to another inmate, Rodrick Finley, offering him $5000 to take the blame for the murders. The police had previously suspected Finley of committing the crime. In all, Dorsey confessed to five different persons: his girlfriend, an acquaintance, the police, a news reporter, and a fellow inmate. In addition, the videotape depicted the perpetrator as a black male of medium build with short hair, wearing a multi-colored jacket. Washington and Hamilton both testified that the distinctive jacket of unusual design and colors worn by the shooter in the videotape looked just like one often worn by Dorsey before the offense. They also stated that they never saw Dorsey wear that particular jacket after the offense. Washington also testified that Dorsey wore his hair in the same style as that of the shooter at the time of the offense, but that she had altered the appearance of Dorsey's hair after the offense by adding braid extensions.

Dorsey told the reporter that he wishes he'd never opened his mouth around her. "It ain't my homeboys that turned on me," he said. "It's this b.tch that I used to put $100 shoes on her feet and take care of her kids. She better hope I never get out of this penitentiary." According to the FBI expert who analyzed the videotape, the shooter was between 5'7" tall and 6' tall. Dorsey is 5'10" tall.

Five months after the video store killings, Dorsey killed a 51-year-old Korean woman, Hyon Suk Chon, at the convenience store she managed in Ennis, south of Dallas. Dorsey and a co-defendant entered a food store, fatally shooting the woman, then fled the scene with an unknown amount of money. He was in prison serving a 60 year sentence for that slaying when he was questioned again about the double slaying and confessed.

The victims' families say Dorsey's profane explanations mean little to them now. "That is just about par for the course," said Greg Armstrong, James Armstrong's brother. "If he has no remorse about it, then he deserves the death penalty." Joan Lindsey Coleman said she has felt better this week than she has in 4 1/2 years, finally knowing who killed her son. "I'll feel even better when I watch him die," she said. "They'd better not screw this up. Now that they've got him, they'd better kill him."

During his time in prison, Dorsey has racked up almost 100 disciplinary records, including stabbing an officer 14 times with a homemade knife, or shank. The officer's flak vest saved him from serious injury. Read more of Dorsey's interview here.

UPDATE: Leon Dorsey was executed for the murders of two Blockbuster Video employees during a robbery 14 years ago in Dallas, Texas. According the TDCJ, Dorsey had recently made threats that he would harm corrections officers prior to his execution, but he did not put up any fight when taken to the execution chamber. In his final statement, Dorsey said, "I love all y'all. I forgive all y'all and I'll see y'all when you get there. Do what you're gonna do." Dorsey said, "Hey sis" when the execution witnesses filed in but he did not direct any comments to the parents of his victims who witnessed the execution.

According to the Huntsville Item, Brad Lindsey's mother Joan Coleman did not make a formal statement following the execution. James Armstrong's parents Gerald and Nancy Armstrong released a letter to the media. “Losing James has been and always will be painful; it doesn’t get any easier, but we’ve gotten stronger,” the letter read. “Viewing Dorsey’s execution will not bring any happiness, but we’ve lived to see justice for James 14 years later and today we pray for Dorsey’s father.”

In a segment of the letter which appears to have been written by Nanci Armstrong, more detail is offered regarding her feelings about Dorsey. “While Gerald has said it was different for him, I have struggled with forgiving Dorsey for killing our son,” she said. “Perhaps Dorsey is as evil as Charles Manson and has no remorse, but I knew that I had to forgive him. I could do it in my head, but not in my heart.” http://www.sonsofsam.net/2008/08/leon-david-dorsey-will-be-executed.html

"Leon David Dorsey Has Been Executed." (Tuesday, August 12, 2008)

HUNTSVILLE, Texas — Texas has executed a 32-year-old man convicted of gunning down two video store workers during a robbery 14 years ago in Dallas. The execution of Leon David Dorsey IV on Tuesday was seventh this year in the nation's most active death penalty state. Three other Texas inmates are scheduled to be executed in the next two weeks.

Dorsey pleaded guilty in 1994 to killing a woman during a convenience store robbery and was sentenced to 60 years in prison. While in prison, Dorsey was convicted in 2000 of killing 26-year-old James Armstrong and 20-year-old Brad Lindsey at an East Dallas Blockbuster Video store where they worked.

Update: Leon Dorsey was reportedly moved earlier today to a holding cell adjacent to the execution chamber. Texas Department of Criminal Justice officials report no incidents so far, despite Mr. Dorsey's vow last month to assault staff members before he is put to death. Officials will hold him in the cell until they receive final word from the state attorney general that there are no appeals pending in his case. If all goes as planned, Mr. Dorsey will die some time after 6 p.m. Stay tuned for updates.

'Meanest criminal' set to die

Huntsville - Leon David Dorsey IV, who brashly called himself "Pistol Pete" and acknowledged in an interview that killing people didn't rankle him, was set to die on Tuesday for the 1994 shooting deaths of two employees at a Dallas video store. "I've done cut folks; I've done stabbed folks; I've killed folks," he told The Dallas Morning News while awaiting trial. "But it don't bother me."

No appeals were in the courts to stop the lethal injection. which would be the seventh this year in the nation's most active capital punishment state and the first of two this week. Another two executions are scheduled for next week. "I did 21 death penalty cases either as the lead or on a team," said Toby Shook, a former Dallas County assistant district attorney. "Upon reflection, Leon Dorsey is probably No 1 as the meanest criminal I prosecuted."

Dorsey, 32, was facing capital murder charges in 1998 for the fatal shootings of James Armstrong, 26, and Brad Lindsey, 20, at the Blockbuster Video store in East Dallas where they worked when he acknowledged to a reporter in a prison interview that he committed the killings. He also suggested the families of his victims not focus on their losses, equating their grief to losing money in a craps game. "That's over and done with," he told The Dallas Morning News in 1998. "I could have came in here and been, 'Oh, I'm sorry, I'm so bad.' But I don't feel like that. That's not being honest with myself."

"Leon didn't do himself any favours in that regard," one of his trial lawyers, Doug Parks, recalled last week. 'He's a total psychopath' Prosecutors used the contents of the interview to help convince a jury he should be put to death. "He's a total psychopath," Shook said. "But the guy was honest about being a psychopath."

Prison records show since he arrived on death row eight years ago, he's had at least 95 disciplinary cases, including a 2004 attack where he used a 20cm shank to stab an officer 14 times in the back. The officer's body armour prevented serious injuries. Less than two weeks ago, authorities recovered another shank from his cell. His threats of violence kept prison officials from making him available for media interviews as his execution date approached.

"We had to convince the jury he'd be a continuing danger and he more than satisfied that in prison," Shook said. A fuzzy black-and-white image of Dorsey on a store video shows him wandering around the place Easter Sunday evening, April 3, 1994, then leaving. He returned just after midnight, robbed $300 from the cash register, then forced Armstrong and Lindsey into an office and became angry because Armstrong had trouble opening a safe. The two workers then were shot. Cameras captured most of the attack.

Kindergarten attack

Dorsey, 18 at the time, told his girlfriend and at least four others about the killings. The girlfriend went to police with the information but detectives believed Dorsey was too tall to be the robber in the photos. Five months later, he killed a 51-year-old Korean woman, Hyon Suk Chon, at the convenience store she managed in Ennis, south of Dallas.

He went to prison for that slaying. Then four years later he confessed to the video store killings when questioned again by police. In the confession, prosecutors said he gave details only the killer would know.

His first trial ended in a mistrial when one juror held out for acquittal. Defence lawyers argued Dorsey was not the man on the video images and pointed out his fingerprints were not found at the murder scene. Jurors at his second trial took three hours to convict him.

Evidence at his trial also showed he offered $5 000 to another inmate to take the fall for the slayings. Dorsey first attracted the attention of police when he was 12, when he was living with his grandparents in Waxahachie after getting kicked out of Germany where his mother was stationed in the Air Force.

He told the newspaper in 1998 he remembered stabbing a pee-wee football teammate while in kindergarten and trying to burn down his baby sitter's house when he was 10. He also had gun incidents in school and with a road-rage attack.

Dorsey v. Quarterman, 494 F.3d 527 (5th Cir. 2007) (Habeas).

Background: Following affirmance on appeal of defendant's state conviction for capital murder and imposition of the death penalty, defendant filed petition for writ of habeas corpus. The United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas, James E. Kinkeade, J., 2006 WL 2161650, denied petition. Appeal was taken.

Holdings: The Court of Appeals, W. Eugene Davis, Circuit Judge, held that:

(1) trial court's error in capital murder proceedings, if any, in denying defendant's motion for mistrial after the jury was exposed to extrinsic evidence of defendant's prior bad acts in an unedited transcript was harmless;

(2) Batson claim was procedurally barred;

(3) trial court's denial of challenge for cause of venire person was not an unreasonable determination of facts, as required for federal habeas relief;

(4) claim that two venire persons should have been excluded for cause based on their statements that they would not consider youth as a mitigating factor was procedurally barred from federal habeas review; and

(5) even if state trial court erred in denying defendant's challenges to venire persons for cause based on alleged bias, there was no constitutional violation, as required for habeas relief.Affirmed.

W. EUGENE DAVIS, Circuit Judge:

Petitioner Leon David Dorsey, IV, was convicted of capital murder in Texas and sentenced to death. The district court granted a certificate of appealability (COA) on two of Dorsey's claims. The first claim based on one or more jurors' exposure to extraneous material fails under harmless error analysis. The second claim, a Batson claim relating to juror Jerry Riley, is procedurally barred. Dorsey also seeks COA on a claim that his constitutional rights were violated by the trial court's denial of his challenge for cause against four venire persons who exhibited a bias in favor of the death penalty. Because Dorsey exercised his peremptory challenges to strike all the jurors at issue, there is no claim that the jury that heard the case was not impartial. Accordingly all requested relief is DENIED.

I. A.

The Court of Criminal Appeals summarized the relevant facts of the crime in its opinion on direct appeal:

The evidence presented at trial showed that, around midnight on April 4, 1994, two employees at a Blockbuster Video store in Dallas were robbed and murdered. The in-store video camera recorded the crime and shows that the perpetrator was a black male with short hair. Employee Brad Lindsey was shot once in the back; employee James Armstrong was shot twice. Later that day, [Dorsey] admitted committing the robbery and murders to his girlfriend, Arrietta Washington, and to an acquaintance, Antwan Hamilton. In an interview with a newspaper reporter, [Dorsey] stated that he had burned the jacket he had worn that night and would not disclose the location of the murder weapon. Washington braided extensions into [Dorsey's] hair as a disguise. Later that week, she reported [Dorsey's] admissions to the police. The police interviewed [Dorsey], but he denied any involvement. At the time, police erroneously believed that [Dorsey] was too tall to be the perpetrator, and he was not charged with the crime, which remained unsolved until the case was reopened in 1998.

During the 1998 investigation, police sent the videotape of the robbery-murder to the F.B.I. for an analysis of the perpetrator's height. Based on the new estimate of the perpetrator's height and accurate information about [Dorsey's] height, police questioned [Dorsey] again, and he confessed. While awaiting trial, [Dorsey] again confessed to this offense during an interview with Dallas Morning News reporter Jason Sickles. A week before trial, [Dorsey] admitted committing the murders to inmate Raymond Carriere. [Dorsey] also sent a letter to another inmate, Rodrick Finley, offering him $5000.00 to take the blame for the murders. The police had previously suspected Finley of committing the crime.

* * *

In the instant case, [Dorsey] confessed to five different persons: his girlfriend, an acquaintance, the police, a news reporter, and a fellow inmate. In addition, the videotape depicted the perpetrator as a black male of medium build with short hair, wearing a multi-colored jacket. Washington and Hamilton both testified that the distinctive jacket of unusual design and colors worn by the shooter in the videotape looked just like one often worn by [Dorsey] before the offense. They also stated that they never saw [Dorsey] wear that particular jacket after the offense. Washington also testified that [Dorsey] wore his hair in the same style as that of the shooter at the time of the offense, but that she had altered the appearance of [Dorsey's] hair after the offense by adding braid extensions. According to the F.B.I. expert who analyzed the videotape, the shooter was between 5'7” tall and 6' tall. [Dorsey] is 5'10” tall. Dorsey v. State, slip op. at 2-5, 2006 WL 2161650 (N.D.Tex.2006).

B.

Dorsey was convicted of capital murder for intentionally and knowingly causing the death of James Lloyd Armstrong by shooting him with a firearm in the course of committing or attempting to commit robbery. Pursuant to the jury's answers to the special punishment issues, the Criminal District Court No. 5 of Dallas County, Texas sentenced Dorsey to death. The Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed Dorsey's conviction and sentence on direct appeal in an unpublished opinion delivered on October 2, 2002. Dorsey v. State, No. 73,836 (Tex.Crim.App.2002). The United States Supreme Court denied Dorsey's petition for writ of certiorari on June 23, 2003. Dorsey v. Texas, 539 U.S. 944, 123 S.Ct. 2607, 156 L.Ed.2d 631 (2003). Dorsey filed a petition for state writ of habeas corpus on May 6, 2002. The Court of Criminal Appeals adopted the trial court's findings and conclusions and, on its own review, denied relief in an unpublished order on February 18, 2004. Ex parte Dorsey, No. 58,161-01 (Tex.Crim.App.2004).

Dorsey timely filed his federal habeas petition on December 17, 2004. The Director filed his answer on March 2, 2005. On July 31, 2006, the district court denied Dorsey's petition for federal habeas relief. Thereafter, on September 12, 2006, the district court granted Dorsey's request for a COA on two claims. Dorsey appealed the denial of habeas relief on those two certified issues. He also filed an application for COA in this Court on an additional claim alleging trial court error in the denial of his challenges for cause to four members of the venire, a claim upon which the trial court did not grant COA.

C.

Additional facts necessary to the issues will be presented in the sections that follow.

II.

The district court granted COA on the first two issues raised by Dorsey in this petition and then denied Dorsey's petition for habeas relief. In a federal habeas corpus appeal, we review factual findings for clear error and legal issues de novo. Valdez v. Cockrell, 274 F.3d 941, 946 (5th Cir.2001). Dorsey's petition is governed by the heightened standard of review provided for by the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA). Under the Act, a writ of habeas corpus should be granted only if a state court arrives at a conclusion opposite to that reached by the Supreme Court on a question of law or if the state court decides a case differently than the Supreme Court on a set of material indistinguishable facts. Williams v. Taylor, 529 U.S. 362, 413, 120 S.Ct. 1495, 146 L.Ed.2d 389 (2000). Without a direct conflict, a writ should be granted only if the state court identifies the correct governing legal principle but unreasonably applies the principle to the facts of the prisoner's case. Id.; Evans v. Cockrell, 285 F.3d 370, 374-75 (5th Cir.2002).

A.

In his first claim for relief, Dorsey contends that he was denied due process of law and his right to be free from cruel and unusual punishment by the trial court's denial of his motion for mistrial after the jury wrongly considered State's Exhibit No. 123. The exhibit consisted of a Dallas Morning News reporter's interview transcript in which Dorsey described numerous extraneous offenses, which the trial court had admitted into evidence for record purposes only.

During guilt-innocence deliberations, one of Dorsey's jurors discovered the full transcript of the interview Dorsey had given to the reporter, Jason Sickles. Sickles had interviewed Dorsey and recorded the entire conversation. The transcript was 88 pages long and contained numerous admissions of bad acts and extraneous offenses. The full transcript was admitted for record purposes as Exhibit 123. A redacted version absent the admissions, Exhibit 110, was admitted for all purposes and played for the jury.

During deliberations, in response to a jury request for “all the evidence”, all trial exhibits were provided to the jury. The full unedited version of the Sickles interview transcript was inadvertently included with the other exhibits from the trial. Approximately an hour and a half after the jury's initial request for all of the evidence, the court received a note, accompanied by the transcript labeled Exhibit 123. The note was signed by the jury foreman, Mark Pennington, and read “Should we have this? It appears to have evidence not brought out on the witness stand.”

In response to the note, the trial court conducted a hearing and interviewed each juror individually. Juror Karen Quinton stated that she was skimming Exhibit 123, but stopped at page 11. She privately notified the foreman that the exhibit referred to some prior offenses. Pennington then wrote the note to the judge outside the presence of the other ten jurors. The hearing revealed that two other jurors were aware that the exhibit contained the full transcript but did not view it. The other jurors were unaware of the exhibit. Some jurors saw Quinton and Pennington talking but did not overhear what they were saying and neither Quinton nor Pennington told the other jurors about the exhibit. Both Quinton and Pennington knew the full exhibit referred to Dorsey's prior bad acts and offenses but only Quinton saw the nature of the acts. Both agreed to follow the court's instruction to set aside any knowledge from the full transcript. Quinton, Pennington and the other two jurors who knew about the exhibit agreed that they would not consider it in their deliberations and assured the court that they would remain fair and impartial. The trial court allowed deliberations to proceed. Dorsey moved for a mistrial which was denied.

The Sixth Amendment guarantees that accused the right to a trial by an impartial jury. Parker v. Gladden, 385 U.S. 363, 364, 87 S.Ct. 468, 17 L.Ed.2d 420 (1966). A jury is initially cloaked with a presumption of impartiality. De La Rosa v. Texas, 743 F.2d 299, 306 (5th Cir.1984). However, if a jury is exposed to an outside influence, a rebuttable presumption of prejudice arises. Drew v. Collins, 964 F.2d 411, 415 (5th Cir.1992). In the context of a federal habeas review, even when there has been extrinsic influence on the jury, such error is subject to harmless error analysis. Pyles v. Johnson, 136 F.3d 986, 994 (5th Cir.1998). Because the claim is presented as a collateral attack on a final state conviction, Dorsey is not entitled to habeas relief on the claim unless the extrinsic evidence of his prior crimes “had a substantial and injurious effect or influence in determining the jury's verdict.” Id. at 995. The content of the extrinsic material, the manner in which it came to the jury's attention, and the weight of the evidence against the defendant are all relevant to the determination of the harm. United States v. Luffred, 911 F.2d 1011, 1014 (5th Cir.1990).

We agree with the district court that any error in this case was harmless. One juror was exposed to factual information about some of Dorsey's prior bad acts in the unedited transcript. Another juror knew only that the transcript contained information about prior bad acts. None of the other jurors knew about the extrinsic material. All of the jurors were questioned to insure that they would disregard the material and that they could be impartial in their deliberations. In addition, the evidence against Dorsey was overwhelming. He confessed to four different people, which confessions were corroborated by the videotape from the store showing a man matching Dorsey's description. Accordingly, the district court correctly determined that the state court's decisions on direct appeal and collateral review are not contrary to federal law.

B.

Dorsey also maintains that the trial court denied his constitutional right to equal protection under the law because the state improperly used a peremptory challenge to remove an African-American man, Jerry Riley, from the jury. The state court rejected Dorsey's Batson claim because Dorsey failed to raise the issue on direct appeal.FN1 The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals has held that record based claims not raised on direct appeal will not be considered in habeas proceedings. Ex parte Gardner, 959 S.W.2d 189, 191 (Tex.Crim.App.1996, clarified on reh'g Feb. 4, 1998). This procedural rule was firmly established by Gardner before Dorsey's appeal following his trial in 2000. This court recognizes that the Gardner rule sets forth an adequate state ground capable of barring federal habeas review. Busby v. Dretke, 359 F.3d 708, 719 (5th Cir.2004) and cases cited therein. Accordingly, the district court erred by failing to apply the procedural bar to this issue. Dorsey makes no claim of cause and prejudice and does not assert that a miscarriage of justice would result if the claim is not considered on its merits. Coleman v. Thompson, 501 U.S. 722, 750, 111 S.Ct. 2546, 115 L.Ed.2d 640 (1991). FN1. Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 106 S.Ct. 1712, 90 L.Ed.2d 69 (1986).

III.

Dorsey also seeks review of the denial of habeas relief on his claim that the trial court erred in denying his challenge for cause of four venire persons who exhibited a bias in favor of the death penalty. The district court did not grant COA on this issue. Unless a COA is granted, this court lacks jurisdiction on the appeal of this issue. 28 U.S.C. § 2253(c)(1)(A). In order for this court to grant COA, Dorsey must make a substantial showing of the denial of a constitutional right. 28 U.S.C. § 2253(c)(2); Barefoot v. Estelle, 463 U.S. 880, 893, 103 S.Ct. 3383, 77 L.Ed.2d 1090 (1983). This standard requires a showing that reasonable jurists could debate whether the petition should have been resolved in a different manner or that the issues presented were adequate to deserve encouragement to proceed further. Slack v. McDaniel, 529 U.S. 473, 484, 120 S.Ct. 1595, 146 L.Ed.2d 542 (2000). For claims that were adjudicated on the merits in state court, deference to the state court's decision is required unless the adjudication was “contrary to, or involved an unreasonable application of, clearly establish Federal law, as determined by the Supreme Court of the United States”, 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d)(1), or “was based on an unreasonable determination of the facts in light of the evidence presented in the State court proceeding.” 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d)(2). Dorsey fails to meet this standard for any of the four venire persons at issue-Merrifield, O'Keefe, Brunson and Staten.

A prospective juror's views on capital punishment do not provide a basis for removal for cause unless those views would “prevent or substantially impair the performance of his duties as a juror in accordance with his instructions and his oath.” Wainwright v. Witt, 469 U.S. 412, 424, 105 S.Ct. 844, 83 L.Ed.2d 841 (1985). The factual question whether the juror is biased and whether his answers can be believed are questions for the trial court. Id. at 423-24, 105 S.Ct. 844.

Venire person Merrifield initially indicated a bias in favor of the death penalty, saying that he would automatically assess the death penalty after a verdict of guilty. He also said that the fact that a person committed capital murder was probably enough evidence to demonstrate future dangerousness and expressed confusion about the necessity of special issue number one. The trial judge briefly explained the guilt-or-innocence phase, the evidence required to prove capital murder and how that evidence related to special issue number one on future dangerousness in the punishment phase. After this explanation which included the state's burden of proof on future dangerousness, Merrifield agreed that he could follow the law and would not automatically answer the issue “yes” unless the state met its burden beyond a reasonable doubt. He also said that he would vote for a life sentence if presented with sufficient mitigating evidence. On this record, the trial court's conclusion that Merrifield was not biased is not an unreasonable determination of the facts. 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d)(2).

Dorsey also claims that venire persons O'Keefe, Brunson and Staten were biased because they said they would not consider youth as a mitigating factors. Dorsey did not raise this claim as to juror's Brunson and Staten on direct appeal. His claims as to those two jurors were rejected as procedurally barred by the state habeas court and are barred from federal habeas review.

As to the merits, the law is clear that a defendant in a capital case is not entitled to challenge prospective jurors for cause simply because they might view the evidence the defendant offers in mitigation of a death sentence as an aggravating rather than a mitigating factor. Johnson v. Texas, 509 U.S. 350, 368, 113 S.Ct. 2658, 125 L.Ed.2d 290 (1993); Soria v. Johnson, 207 F.3d 232, 244 (5th Cir.2000).

In addition, Dorsey used peremptory challenges to remove the four venire persons from the jury. Accordingly, even if the court erred in denying his challenges for cause, there was no constitutional violation because the jurors were removed from the jury by his use of peremptory challenges and he has not alleged that the jury that sat in his capital murder trial was not impartial. Ross v. Oklahoma, 487 U.S. 81, 88, 108 S.Ct. 2273, 101 L.Ed.2d 80 (1988). COA is denied on this issue.

IV.

None of the claims raised by Dorsey are sufficient to merit habeas relief or grant of COA in his favor. For the foregoing reasons, we affirm the district court's denial of habeas relief on issues one and two. We also deny his application for COA on the remaining issue.