Executed June 25, 2013 06:25 p.m. CDT by Lethal Injection in Oklahoma

17th murderer executed in U.S. in 2013

1337th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

3rd murderer executed in Oklahoma in 2013

105th murderer executed in Oklahoma since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(17) |

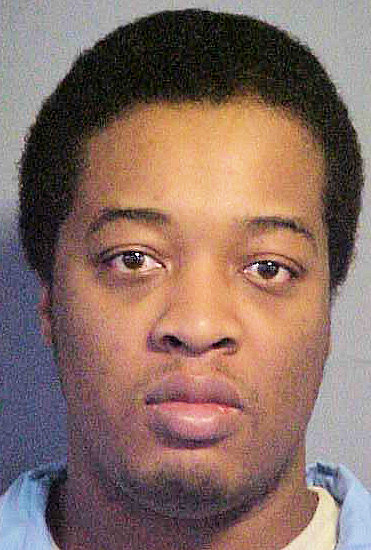

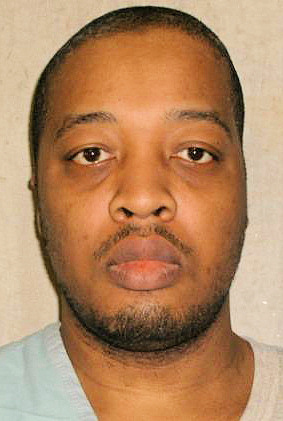

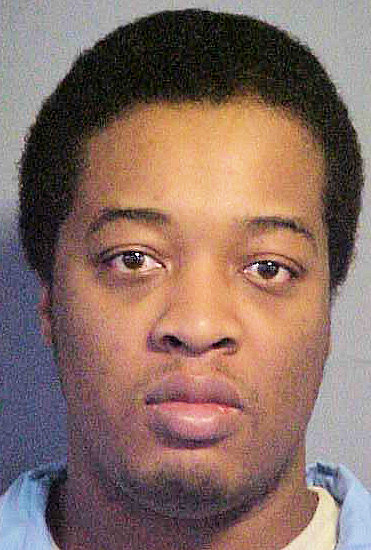

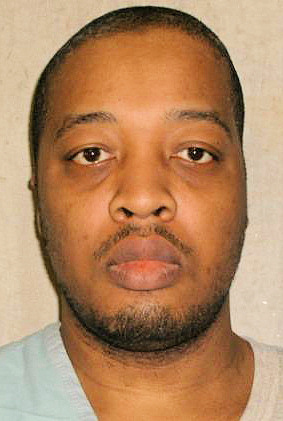

Brian Darrell Davis B / M / 27 - 39 |

Josephine "Jody" Haley Sanford B / F / 52 |

Citations:

Davis v. State, 103 P.3d 70 (Okla.Crim. App. 2004). (Direct Appeal)

Davis v. State, 123 P.3d 243 (Okla.Crim. App. 2005). (PCR)

Davis v. Workman, 695 F.3d 1060 (10th Cir. 2012). (Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

Davis requested no special last meal for his execution day. He ate what the other offenders at OSP had for dinner: BBQ bologna, bread, rice, cookies and lemonade.

Final Words:

“First I would like to say I would like to give the glory to God.” Davis then began quoting biblical scripture. “I shall not die, but live,” he said. “His word is will and let His will be done. I give God the last word — Psalm 119: 17 and 18.” Davis then quoted more scripture and finished his last statement when he said, “Thank you.”

Internet Sources:

Oklahoma Department of Corrections

Inmate: BRIAN D DAVIS

ODOC# 230936

Birth Date: 05/10/1974

Race: Black

Sex: Male

Height: 5 ft. 10 in.

Weight: 210 pounds

Hair: Black

Eyes: Brown

Convictions:

CASE# County Offense Conviction Term Start

93-436 KAY Rape In The 2nd Degree 04/20/1995 7Y 0M 0D Probation 04/20/1995 04/19/1997

93-436 KAY Rape In The 2nd Degree 04/20/1995 7Y 0M 0D Probation 04/20/1995 04/19/1997

94-315 KAY Unlawful Poss Of Cds, Cocaine 04/20/1995 7Y 0M 0D Probation 04/20/1995 04/19/1997

2001-733 KAY Murder In The First Degree 03/07/2003 DEATH Death 03/17/2003

2001-733 KAY First Degree Rape 03/07/2003 100Y Incarceration 03/17/2003 07/14/2087

Death Penalty Information

The current death penalty law was enacted in 1977 by the Oklahoma Legislature. The method to carry out the execution is by lethal injection. The original death penalty law in Oklahoma called for executions to be carried out by electrocution. In 1972 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional the death penalty as it was then administered.

Oklahoma has executed a total of 176 men and 3 women between 1915 and 2011 at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary. Eighty-two were executed by electrocution, one by hanging (a federal prisoner) and 96 by lethal injection. The last execution by electrocution took place in 1966. The first execution by lethal injection in Oklahoma occurred on September 10, 1990, when Charles Troy Coleman, convicted in 1979 of Murder 1st Degree in Muskogee County was executed.

Execution Process

Method of Execution: Lethal Injection

Drugs used:

Sodium Thiopental or Pentobarbital - causes unconsciousness

Vecuronium Bromide - stops respiration

Potassium Chloride - stops heart

Two intravenous lines are inserted, one in each arm. The drugs are injected by hand held syringes simultaneously into the two intravenous lines. The sequence is in the order that the drugs are listed above. Three executioners are utilized, with each one injecting one of the drugs.

"OSP death row inmate executed Tuesday, by Rachel Petersen. (Tue Jun 25, 2013, 07:17 PM CDT)

McALESTER — A death row inmate at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary was executed Tuesday evening in the prison’s death chamber. Brian Darrell Davis, 38, had requested no special last meal for his execution day. He ate what the other offenders at OSP had for dinner, said OSP Warden’s Assistant Terry Crenshaw. “BBQ bologna, bread, rice, cookies and lemonade.”

Witnessing the execution were three media representatives, one of Davis’s attorneys, Kay County Sheriff Everette Vanhoesen and an Oklahoma Department of Corrections representative. The execution procedures began at 6:19 p.m. and OSP Warden Anita Trammell asked Davis if he would like to say any last words. “Yes, I would,” Davis said. “First I would like to say I would like to give the glory to God.” Davis then began quoting biblical scripture. “I shall not die, but live,” he said. “His word is will and let His will be done. I give God the last word — Psalm 119: 17 and 18.” Davis then quoted more scripture and finished his last statement when he said, “Thank you.” At 6:20 p.m., Trammell said, “Let the execution begin.” At 6:21 p.m., Davis’s breathing became labored. His body shuttered and his eyes closed. At 6:25 p.m. an attending physician pronounced Davis’s time of death.

Earlier this month, the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board voted 4-1 to recommend granting clemency to Davis. Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt released a statement on June 7 in which he denounced the board’s clemency vote and Oklahoma Gov. Mary Fallin denied the recommendation, saying that Davis is to be executed as scheduled. “This convicted murderer lured his estranged girlfriend’s mother to his apartment and then brutally raped her, broke her jaw, stabbed her six times, puncturing her abdomen, and left her for dead while he drove around in her van,” Pruitt said. “He does not deserve our pity or clemency, and it is incomprehensible that four members of the pardon and parole board would usurp the judgment of a jury and deny this family justice.”

Of the last 11 death row inmates set for execution in Oklahoma, the board voted to recommend clemency only one other time, for Garry Thomas Allen. As with Davis, Fallin did not approve the board’s recommendation and Allen was executed Nov. 6, 2012. Davis is the second death row inmate set for execution this month. James Lewis DeRosa, 36, was put to death via lethal injection on June 18. The board did not recommend clemency for DeRosa. Both DeRosa and Davis opted to make no last meal requests. In fact, both offenders made no requests at all, Crenshaw said. This includes last meal requests as well as requests for visitors on execution day. Crenshaw said the fact that the two inmates chose to make no last meal requests is quite out of the ordinary. Davis and DeRosa were cell mates, Crenshaw said.

On April 15, the U.S. Supreme Court denied Davis’s final appeal and Pruitt requested an execution date be set. Davis was convicted of the Nov. 4, 2001, rape and murder of 52-year-old Josephine “Jody” Sanford. “In January 2003, Davis was found guilty by a jury for the November 2001 first-degree murder and rape of his girlfriend’s mother, Jody Sanford, 52, of Ponca City,” Pruitt said in a press release. “He was sentenced to death for the murder and 100 years for rape.”

According to court records, Davis returned home in the early morning hours of Nov. 4, 2001, after socializing with friends at a local club. When he arrived home, he found that his girlfriend, Stacey Sanford, and their 3-year-old daughter were missing. Davis called Jody Sanford, Stacey Sanford’s mother, to ask if she knew where his girlfriend and daughter were, court records state. “When Jody could not locate her daughter and granddaughter, she went to Stacey’s and Davis’s apartment.” Davis made several conflicting statements regarding what happened while Jody Sanford was in his home. According to court records, he changed his story multiple times and told different stories to his girlfriend, to police and to the jury at his trial. Court records indicate that Davis did admit to having sex with and stabbing Jody Sanford.

When Stacey Sanford arrived home shortly after 9 a.m., she found her mother’s body. “Stacey (Sanford) immediately called 911 and local police arrived to investigate,” court records state. “Meanwhile, Davis had been involved in a single-car accident while driving Jody’s van near the Salt Fork River Bridge. Davis was seriously injured after he was ejected from the van through the front windshield. Davis was transported to a local hospital for treatment.” Because Davis had a blood alcohol level of .09 percent, he was placed under arrest for driving under the influence and was later transferred to a regional hospital in Wichita, Kan., for treatment for injuries he sustained in the car accident. According to Pruitt, Jody Sanford had been beaten and stabbed six times and DNA evidence showed Davis had raped her. Davis had been in custody with the Oklahoma Department of Corrections since March 17, 2003.

"Okla. executes man in death of girlfriend's mother." (Modified: June 25, 2013 at 8:10 pm)

McALESTER, Okla. (AP) — A man convicted of raping and killing his girlfriend's mother in 2001 was executed in Oklahoma Tuesday, despite a recommendation by the state's pardon and parole board to commute his death sentence after he apologized. Brian Darrell Davis, 39, received a lethal injection Tuesday at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester. Davis was the third inmate to be executed by Oklahoma this year and the second in as many weeks.

Davis recited a biblical-themed statement that included Psalms and scripture-based references. "I shall not die but live. His word is will, and let his will be done," Davis said. "I give God the last word. Thank you." Moments later, Davis looked up at the ceiling as the lethal drug was injected. His eyes slowly closed and his left shoulder began to twitch. He was pronounced dead at 6:25 p.m. CDT, five minutes after the injection was administered. Neither family members of the victim nor Davis came to watch the execution. Prison officials said it was likely Davis would be buried in a pauper's cemetery near the prison — known by inmates as Peckerwood Hill — because Davis did not fill out paperwork on who would claim his body.

The state's parole board had suggested to Gov. Mary Fallin that she cut Davis' sentence to life without parole. Fallin rejected the recommendation, with spokesman Aaron Cooper saying the governor reviewed Davis' file and was "satisfied that justice is being served."

A Kay County jury convicted Davis in 2003 of first-degree murder and first-degree rape in the death of his girlfriend's mother, Josephine Sanford, 52. Davis was sentenced to death on the murder conviction and 100 years in prison for rape. The victim's daughter, Stacey Sanford, discovered her mother dead in November 2001 in the Ponca City apartment she shared with Davis. Prosecutors said Josephine Sanford had six stab wounds, a broken jaw and marks around her neck. DNA evidence showed Davis had sex with the victim.

Davis went to the parole board this month, took responsibility for the death and apologized. He said the sexual contact was consensual and that a fight broke out after he remarked about its quality. "I was rude at the end," Davis said, appearing before the panel by video. "We were mad at each other after my comment. And one thing led to another. It just happened so quick." The board voted 4-1 in favor of clemency, prompting Attorney General Scott Pruitt to say the board was usurping the jury that convicted Davis and that the inmate deserved to die for a brutal crime.

Davis' defense attorney, Jack Fisher, said as the execution date approached that justice was not being served. "By the end of the clemency hearing, four of the five board members were convinced that justice could only be served by a sentence of life without parole," Fisher said. "Why Gov. Fallin would substitute her judgment for four members of the board is a mystery to me."

Death penalty opponents, who rallied Monday at the state Capitol to urge Fallin to show mercy, argued that Davis deserved life in prison, not death, after he showed remorse. They also suggested that since Davis, who is black, was convicted by an all-white jury in Kay County that it wasn't truly a jury of his peers and there could have been bias. "Our governor is in a position to make a wrong right," said Garland Pruitt, president of the Oklahoma City chapter of the NAACP. "Wrongs can be righted, hearts can be changed, but it takes those in office to help make those changes take place."

Last week, the state executed James Lewis DeRosa, 36, for his part in the brutal killings of a LeFlore County ranch couple in 2000.

"Rapist and murderer executed by injection in Oklahoma." (9:11 p.m. EDT June 25, 2013)

TULSA, Oklahoma (AP) — A man convicted of raping and murdering his girlfriend's mother in 2001 was put to death on Tuesday, despite a recommendation by Oklahoma's pardon and parole board to commute his death sentence after he apologized. Brian Darrell Davis, 39, received a lethal injection Tuesday at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester. Davis was the third inmate to be executed by Oklahoma this year and the second in as many weeks.

Davis read a biblical-themed statement that included psalms and scripture-based references. "I shall not die but live. His word is will, and let His will be done," Davis said. "I give God the last word. Thank you." Moments later, Davis looked up at the ceiling as the lethal drug was injected. His eyes slowly closed and his left shoulder began to twitch as the lethal drug took effect. Davis was pronounced dead at 6:25 p.m., five minutes after the lethal drug was administered.

The state's parole board had suggested to Gov. Mary Fallin that she cut Davis' sentence to life without parole. Fallin rejected the board recommendation, with spokesman Aaron Cooper saying the governor reviewed Davis' file and was "satisfied that justice is being served in this case."

A jury convicted Davis in 2003 of first-degree murder and first-degree rape in the death of his girlfriend's mother, Josephine Sanford, 52. Davis was sentenced to death on the murder conviction and 100 years in prison for rape. The victim's daughter, Stacey Sanford, discovered her mother dead in November 2001 in the Ponca City apartment she shared with Davis. Prosecutors said Josephine Sanford had six stab wounds, a broken jaw and marks around her neck. DNA evidence showed Davis had sex with the victim.

Davis went to the parole board this month, took responsibility for the victim's death and apologized. He said the sexual contact was consensual and that a fight broke out after he remarked about its quality. "I was rude at the end," Davis said, appearing before the panel by video. "We were mad at each other after my comment. And one thing led to another. It just happened so quick." The board voted 4-1 in favor of clemency, prompting Attorney General Scott Pruitt to say the board was usurping the jury that convicted Davis and that the inmate deserved to die for a brutal crime. Davis' defense attorney, Jack Fisher, said as the execution date approached that justice was not being served. "By the end of the clemency hearing, four of the five board members were convinced that justice could only be served by a sentence of life without parole," Fisher said. "Why Governor Fallin would substitute her judgment for four members of the board is a mystery to me."

Death penalty opponents, who rallied Monday at the state Capitol to urge Fallin to show mercy, argued that Davis deserved life in prison, not death, after he showed remorse. They also suggested that since Davis, who is black, was convicted by an all-white jury in Kay County that it wasn't truly a jury of his peers and there could have been bias. "Our governor is in a position to make a wrong right," said Garland Pruitt, president of the Oklahoma City chapter of the NAACP. "Wrongs can be righted, hearts can be changed, but it takes those in office to help make those changes take place." Last week, the state executed James Lewis DeRosa, 36, for his part in the brutal killings of a LeFlore County ranch couple in 2000.

"Oklahoma executes man for killing girlfriend's mother," by Heide Brandes. (OKLAHOMA CITY | Tue Jun 25, 2013 9:56pm EDT)

(Reuters) - Oklahoma executed a man on Tuesday convicted of raping and stabbing his girlfriend's mother to death during a late night fight in 2001, a state corrections department spokesman said. Brian Darrell Davis, 38, was pronounced dead at 6:25 p.m. CDT (7.25 p.m. EDT) after a lethal injection at a state prison in McAlester, said Jerry Massie, a spokesman for the Oklahoma Department of Corrections. He was the second Oklahoma inmate executed in two weeks and the third in 2013. Davis was also the 17th person to be executed in the United States this year, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

Asked if he would like to say any last words, Massie said that Davis replied, "Yes, I would. First I'd like to say that I give the glory to God." He then quoted several Bible verses and added, "I shall not die but live. His word is my will and I let his will be done. I give God the last word." Davis did not request a last meal, according to Massie.

Davis was convicted of stabbing Josephine "Jody" Sanford, 52, to death after raping her at the apartment he shared with her daughter, Stacey Sanford. Davis said he returned home from a club early that morning and discovered his live-in girlfriend Stacey and their 3-year-old daughter were gone. Davis said he and Jody Sanford then had consensual sex, argued and fought, and he admitted to stabbing her. Authorities said she had six stab wounds and a broken jaw. Davis said Sanford had attacked him and he never intended to kill her. However, jurors found the killing to be especially heinous, atrocious or cruel and Davis was sentenced to death.

On June 13, Oklahoma Governor Mary Fallin denied Davis' request for clemency, rejecting a parole board recommendation that his sentence be commuted to life without parole.

Oklahoma Coalition to Abolish Death Penalty

In the early morning hours of November 4, 2001, Brian Davis returned home after socializing with some friends at a local club, only to find his girlfriend, Stacey Sanford, and their three-year-old daughter missing. He telephoned Josephine “Jody” Sanford, Stacey’s mother, to ask if she had seen or knew of their whereabouts. Jody told Davis that she did not know where they were. Ten to fifteen minutes later, Davis again telephoned Jody and asked her to go and find them. When Jody could not locate her daughter and granddaughter, she went to Stacey’s and Davis’s apartment.

Davis made several conflicting statements about the events that followed once Jody arrived, including a different version during his trial testimony. However, with the exception of his first statement where he claimed to have no memory of what had happened, Davis admitted in his other statements that he fatally stabbed Jody. Jody’s body was discovered shortly after 9:00 a.m. when her daughter Stacey returned home. Stacey immediately called 911 and local police arrived to investigate. Meanwhile, Davis had been involved in a single-car accident while driving Jody’s van near the Salt Fork River Bridge. Davis was seriously injured after he was ejected from the van through the front windshield. Davis was transported to a local hospital for treatment. Because there was an odor of alcohol about him, Davis was placed under arrest and his blood alcohol level was tested and registered .09%.

Later on, Davis was transported to a Wichita hospital for further care. Detective Donald Bohon interviewed Davis around 5:49 p.m. that afternoon. In his first statement, Davis was able to recount his activities at the club the night before, but could not remember who drove him home. He recalled that Stacey and his daughter were not at home when he arrived and he remembered telephoning Jody. He could remember Jody being in the living room with him, but after that moment, he could not recall anything until he woke up in the field after the accident.

Two days later, Detectives Bohon and Bob Stieber interviewed Davis again. Initially, Davis repeated the story he had previously told Detective Bohon. As Stieber questioned Davis, his memory improved. He remembered Jody talking to him about religion and his commitment to Stacey. An angry Davis told Jody that there would be no commitment and the two argued. Davis claimed that Jody stood up while she continued her lecture and that he then stood up, got angry, accused her of being in his face and told her to “back up,” pushing her backwards. Davis claimed Jody grabbed a knife and cut him on his thumb. Davis then hit Jody on the chin (apparently causing the fracture to her jawbone) and tried to grab the knife, getting cut in the process. Davis said he got the knife from Jody and told her to get back, stabbing her in the stomach. He stated that he and Jody began to wrestle down the hallway and that he stabbed Jody in the leg. Once in the bedroom, Davis told Jody to stop and he put the knife down. Jody asked Davis to let her go to which he agreed, but then Jody ran towards the knife. He grabbed the knife first and stabbed Jody on the left side. She then told Davis that she could not breathe and Davis told her to lie down on the bed. Davis said he tried to wrap her up tightly in the bedspread so she would not bleed to death. He claimed he heard her stop breathing, but then fell asleep. When he awoke, he panicked and fled in Jody’s van so he could think about what to do. Shortly thereafter, the crash occurred.

When Stieber confronted him with physical evidence showing Jody was strangled/choked, Davis conceded that he may have choked her while they were wrestling. However, he adamantly denied having consensual or non-consensual sex with her. Davis told his girlfriend Stacey three different versions of what happened that morning. At first, he told her that he believed her mother was an intruder and that he instinctively fought with her to protect his family home. Several months later, he told Stacey that her mother came to their apartment and that the two of them argued because Davis believed Jody was lying about her knowledge of Stacey’s whereabouts. He claimed he pushed Jody and Jody went to the kitchen and retrieved a knife. Davis said that he got his thumb cut when he tried to take the knife from Jody, and that once he got the knife, he stabbed Jody once in the stomach. The argument continued and the two of them ended up in the bedroom where Jody said let’s end this and Davis put the knife down. He claimed that she grabbed the knife as she walked towards the door and that he took it from her and stabbed her again.

Two to three months later after DNA tests showed that Davis’ semen was found in Jody’s vagina, Stacey confronted Davis and he told her a third version of what had happened. In this third version, he said that Jody came to their apartment upset about her husband’s infidelity. He claimed that he tried to comfort her and they ended up having consensual intercourse. After their sexual encounter, Davis said he was lying on the floor in the front room while Jody was in the kitchen and that all of a sudden he was struck in the back of the head with some object. He did not elaborate on the details of the stabbing, indicating that the events unfolded from there.

At trial, Davis testified that Jody came to his apartment after she could not locate Stacey and talked to him about his need to commit to her. Davis claimed he responded by making a remark about Jody’s husband’s level of commitment and his rumored infidelity. He said that Jody became emotional and acknowledged that she knew about her husband’s affair. Davis said he felt badly about his remark and got up and sat beside Jody and tried to comfort her. He claimed that Jody kissed him and that they ended up going back to the bedroom and having sex on the bedroom floor for fifteen to twenty minutes. Afterwards Davis got up and stumbled between the hallway and bedroom. He said that Jody was saying something about the time and he said that the sex was not worth his time and that he understood why Jody’s husband was having an affair. He claimed that an angry Jody then hit him in the back of the head with a lotion dispenser, stunning him. As Jody walked by Davis, Davis got up and chased her down the hallway, tackling her and biting her ankle. Jody kicked Davis in the mouth and ran to the kitchen and grabbed a knife. Davis then ran to the living room and grabbed the Play Station II. Davis asked Jody “what the hell are you doing?” and hit her in the face. Davis said Jody “came back with a defensive position” and that he used the Play Station II as a shield. Now angrier, Davis hit Jody again and tossed the Play Station II into a nearby chair. He backed her down the hallway while she swung the knife wildly, cutting Davis on his arm. Davis went into the bathroom for a towel and Jody retreated to the bedroom. He said that when he exited the bathroom he saw Jody in the bedroom doorway and that he ran at her, grabbed her, pulled her down and hit her in the face two to three times. As they were fighting, Davis pushed Jody’s head against the wall and struck her until she finally relinquished the knife. Jody retreated into the bedroom and asked Davis to let her go. Davis claimed he told Jody to go and put the knife on the nightstand. He said that when Jody walked by, she grabbed the knife, which angered him because he believed the fight was over. He then grabbed her shirt, pulled her towards him and put his arm around her neck squeezing as tightly as he could until she dropped the knife. He said that he grabbed the knife, that he was angry and that he stabbed Jody in the back. Jody then “swung back,” struck him in the groin and he fell to one knee. He claimed Jody continued to hit him and that he stabbed her several times as he tried to fend off her attack. He maintained that he never intended to kill Jody.

Oklahoma Attorney General (News Release)

News Release - Brian Darrell Davis Execution Set for June

05/02/2013

OKLAHOMA CITY – The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals Thursday set June 25 as the execution date for Kay County death row inmate Brian Darrell Davis, 38. Davis was found guilty by a jury in January 2003 for the November 2001 first-degree murder and rape of his girlfriend’s mother, Jody Sanford, 52, of Ponca City. He was sentenced to death for the murder and 100 years for rape.

In November 2001, Davis was living with his girlfriend, Stacey Sanford. They had ended the relationship, but he refused to move out. The night of the murder, Stacey stayed at a hotel after Davis had been drinking. Davis called Stacey’s parents looking for her and Jody Sanford became concerned. Unable to locate her daughter, Jody Sanford went to Stacey's apartment. While at the apartment, there was an altercation between Davis and Jody Sanford. The next morning, Stacey found her mother’s body. She had been beaten and stabbed six times. DNA evidence also showed Jody Sanford had been raped.

The execution date was requested by Attorney General Scott Pruitt on April 15 after the U.S. Supreme Court denied the final appeal for Davis.

06/13/2013

Attorney General Pruitt Applauds Governor’s Decision to Deny Clemency for Brian Darrell Davis

“I appreciate the Governor’s consideration of this case, and thank her for her decision to bring justice for this family and deny clemency for Brian Darrell Davis,” Attorney General Scott Pruitt said. “Given the brutality of this crime, he does not deserve clemency and now must face the punishment determined by judge and jury.”

Wikipedia: Oklahoma Executions

A total of 103 individuals convicted of murder have been executed by the State of Oklahoma since 1976, all by lethal injection:

1. Charles Troy Coleman 10 September 1990 John Seward

2. Robyn Leroy Parks 10 March 1992 Abdullah Ibrahim

3. Olan Randle Robinson 13 March 1992 Shiela Lovejoy, Robert Swinford

4. Thomas J. Grasso 20 March 1995 Hilda Johnson

5. Roger Dale Stafford 1 July 1995 Melvin Lorenz, Linda Lorenz, Richard Lorenz, Isaac Freeman, Louis Zacarias, Terri Horst, David Salsman, Anthony Tew, David Lindsey

6. Robert Allen Brecheen [1][2][3] 11 August 1995 Marie Stubbs

7. Benjamin Brewer 26 April 1996 Karen Joyce Stapleton

8. Steven Keith Hatch 9 August 1996 Richard Douglas, Marilyn Douglas

9. Scott Dawn Carpenter 7 May 1997 A.J. Kelley

10. Michael Edward Long 20 February 1998 Sheryl Graber, Andrew Graber

11. Stephen Edward Wood 5 August 1998 Robert B. Brigden

12. Tuan Anh Nguyen 10 December 1998 Amanda White, Joseph White

13. John Wayne Duvall 17 December 1998 Karla Duvall

14. John Walter Castro 7 January 1999 Beulah Grace, Sissons Cox, Rhonda Pappan

15. Sean Richard Sellers 4 February 1999 Paul Bellofatto, Vonda Bellofatto, Robert Bower

16. Scotty Lee Moore 3 June 1999 Alex Fernandez

17. Norman Lee Newsted 8 July 1999 Larry Buckley

18. Cornel Cooks 2 December 1999 Jennie Elva Ridling

19. Bobby Lynn Ross 9 December 1999 Steven Mahan

20. Malcolm Rent Johnson 6 January 2000 Ura Alma Thompson

21. Gary Alan Walker 13 January 2000 Eddie O. Cash, Valerie Shaw-Hartzell, Jane Hilburn, Janet Jewell, Margaret Bell Lydick, DeRonda Gay Roy

22. Michael Donald Roberts 10 February 2000 Lula Mae Brooks

23. Kelly Lamont Rogers 23 March 2000 Karen Marie Lauffenburger

24. Ronald Keith Boyd 27 April 2000 Richard Oldham Riggs

25. Charles Adrian Foster 25 May 2000 Claude Wiley

26. James Glenn Rodebeaux 1 June 2000 Nancy Rose Lee McKinney

27. Roger James Berget 8 June 2000 Rick Lee Patterson

28. William Clifford Bryson 15 June 2000 James Earl Plantz

29. Gregg Francis Braun 10 August 2000 Gwendolyn Sue Miller, Barbara Kchendorfer, Mary Rains, Pete Spurrier, Geraldine Valdez

30. George Kent Wallace 10 August 2000 William Von Eric Domer, Mark Anthony McLaughlin

31. Eddie Leroy Trice 9 January 2001 Ernestine Jones

32. Wanda Jean Allen 11 January 2001 Gloria Jean Leathers

33. Floyd Allen Medlock 16 January 2001 Katherine Ann Busch

34. Dion Athansius Smallwood 18 January 2001 Lois Frederick

35. Mark Andrew Fowler 23 January 2001 John Barrier, Rick Cast, Chumpon Chaowasin

36. Billy Ray Fox 25 January 2001

37. Loyd Winford Lafevers 30 January 2001 Addie Mae Hawley

38. Dorsie Leslie Jones, Jr. 1 February 2001 Stanley Eugene Buck, Sr.

39. Robert William Clayton 1 March 2001 Rhonda Kay Timmons

40. Ronald Dunaway Fluke 27 March 2001 Ginger Lou Fluke, Kathryn Lee Fluke, Suzanna Michelle Fluke

41. Marilyn Kay Plantz 1 May 2001 James Earl Plantz

42. Terrance Anthony James 22 May 2001 Mark Allen Berry

43. Vincent Allen Johnson 29 May 2001 Shirley Mooneyham

44. Jerald Wayne Harjo 17 July 2001 Ruther Porter

45. Jack Dale Walker 28 August 2001 Shely Deann Ellison, Donald Gary Epperson

46. Alvie James Hale, Jr. 18 October 2001 William Jeffery Perry

47. Lois Nadean Smith 4 December 2001 Cindy Baillee

48. Sahib Lateef Al-Mosawi 6 December 2001 Inaam Al-Nashi, Mohamed Al-Nashi

49. David Wayne Woodruff 21 January 2002 Roger Joel Sarfaty, Lloyd Thompson

50. John Joseph Romano 29 January 2002

51. Randall Eugene Cannon 23 July 2002 Addie Mae Hawley

52. Earl Alexander Frederick, Sr. 30 July 2002 Bradford Lee Beck

53. Jerry Lynn McCracken[10] 10 December 2002 Tyrrell Lee Boyd, Steve Allen Smith, Timothy Edward Sheets, Carol Ann McDaniels

54. Jay Wesley Neill 12 December 2002 Kay Bruno, Jerri Bowles, Joyce Mullenix, Ralph Zeller

55. Ernest Marvin Carter, Jr. 17 December 2002 Eugene Mankowski

56. Daniel Juan Revilla 16 January 2003 Mark Gomez Brad Henry

57. Bobby Joe Fields 13 February 2003 Louise J. Schem

58. Walanzo Deon Robinson 18 March 2003 Dennis Eugene Hill

59. John Michael Hooker 25 March 2003 Sylvia Stokes, Durcilla Morgan

60. Scott Allen Hain 3 April 2003 Michael William Houghton, Laura Lee Sanders

61. Don Wilson Hawkins, Jr. 8 April 2003 Linda Ann Thompson

62. Larry Kenneth Jackson 17 April 2003 Wendy Cade

63. Robert Wesley Knighton 27 May 2003 Richard Denney, Virginia Denney

64. Kenneth Chad Charm 5 June 2003 Brandy Crystian Hill

65. Lewis Eugene Gilbert II 1 July 2003 Roxanne Lynn Ruddell

66. Robert Don Duckett 8 July 2003 John E. Howard

67. Bryan Anthony Toles 22 July 2003 Juan Franceschi, Lonnie Franceschi

68. Jackie Lee Willingham 24 July 2003 Jayne Ellen Van Wey

69. Harold Loyd McElmurry III 29 July 2003 Rosa Vivien Pendley, Robert Pendley

70. Tyrone Peter Darks 13 January 2004 Sherry Goodlow

71. Norman Richard Cleary 17 February 2004 Wanda Neafus

72. David Jay Brown 9 March 2004 Eldon Lee McGuire

73. Hung Thanh Le 23 March 2004 Hai Hong Nguyen

74. Robert Leroy Bryan 8 June 2004 Mildred Inabell Bryan

75. Windel Ray Workman 26 August 2004 Amanda Hollman

76. Jimmie Ray Slaughter 15 March 2005 Melody Sue Wuertz, Jessica Rae Wuertz

77. George James Miller, Jr. 12 May 2005 Gary Kent Dodd

78. Michael Lannier Pennington 19 July 2005 Bradley Thomas Grooms

79. Kenneth Eugene Turrentine 11 August 2005 Avon Stevenson, Anita Richardson, Tina Pennington, Martise Richardson

80. Richard Alford Thornburg, Jr. 18 April 2006 Jim Poteet, Terry Shepard, Kevin Smith

81. John Albert Boltz 1 June 2006 Doug Kirby

82. Eric Allen Patton 29 August 2006 Charlene Kauer

83. James Patrick Malicoat 31 August 2006 Tessa Leadford

84. Corey Duane Hamilton 9 January 2007 Joseph Gooch, Theodore Kindley, Senaida Lara, Steven Williams

85. Jimmy Dale Bland 26 June 2007 Doyle Windle Rains

86. Frank Duane Welch 21 August 2007 Jo Talley Cooper, Debra Anne Stevens

87. Terry Lyn Short[4] 17 June 2008 Ken Yamamoto

88. Jessie Cummings 25 September 2008 Melissa Moody

89. Darwin Brown 22 January 2009 Richard Yost

90. Donald Gilson 14 May 2009 Shane Coffman

91. Michael DeLozier 9 July 2009 Orville Lewis Bullard, Paul Steven Morgan

92. Julius Ricardo Young 14 January 2010 Joyland Morgan, Kewan Morgan

93. Donald Ray Wackerly II 14 October 2010 Pan Sayakhoummane

94. John David Duty 16 December 2010 Curtis Wise

95. Billy Don Alverson 6 January 2011 Richard Kevin Yost

96. Jeffrey David Matthews 11 January 2011 Otis Earl Short Mary Fallin

97. Gary Welch 5 January 2012 Robert Dean Hardcastle

98. Timothy Shaun Stemple 15 March 2012 Trisha Stemple

99. Michael Bascum Selsor 1 May 2012 Clayton Chandler

100. Michael E. Hooper 14 August 2012 Cynthia Jarman, Timothy Jarman, Tonya Jarman

101. Garry T. Allen 06 November 2012 Gail Titsworth

102. George Ochoa 04 December 2012 Francisco Morales, Maria Yanez

103. Steven Ray Thacker 12 March 2013 Laci Dawn Hill

104. James L. DeRosa 18 June 2013 Curtis and Gloria Plummer

105. Brian Darrell Davis 25 June 2013 Jody Sanford

Davis v. State, 103 P.3d 70 (Okla.Crim. App. 2004). (Direct Appeal)

Background: Defendant was convicted by jury in the District Court, Kay County, Leslie D. Page, Associate District Judge, of one count of first degree malice murder and one count of first degree rape. Defendant appealed.

Holdings: The Court of Criminal Appeals, Strubhar, J., held that: (1) trial court did not abuse its discretion in allowing rebuttal testimony of witnesses; (2) sufficient evidence proved beyond a reasonable doubt that defendant intended to kill victim, as required to support conviction; (3) trial court did not abuse its discretion in limiting defendant's questioning of witnesses; (4) sufficient evidence supported trial court's finding that defendant's waiver of rights and subsequent statements were voluntary and therefore admissible; and (5) sufficient evidence supported jury's finding that victim's murder was especially heinous, atrocious or cruel. Affirmed.

STRUBHAR, Judge.

¶ 1 Brian Darrell Davis, Appellant, was tried by jury in the District Court of Kay County, Case No. CF–2001–733, where he was convicted of one count of First Degree Malice Murder and one count of First Degree Rape, After Former Conviction of Two Felonies. The jury set punishment at death for the murder after finding the murder was especially heinous, atrocious or cruel FN1 and one hundred (100) years imprisonment for the rape. The Honorable Leslie D. Page, who presided at trial, sentenced Davis accordingly. From this Judgment and Sentence, he appeals.FN2 FN1. 21 O.S.2001, § 701.12(4). FN2. Davis' Petition in Error was filed in this Court on March 26, 2003. Appellant's brief was filed March 5, 2004, and the State's brief was filed July 9, 2004. The case was submitted to the Court on July 15, 2004. Oral argument was held October 26, 2004.

FACTS

¶ 2 In the early morning hours of November 4, 2001, Davis returned home after socializing with some friends at a local club, only to find his girlfriend, Stacey Sanford, and their three-year-old daughter missing. He telephoned Josephine “Jody” Sanford, Stacey's mother, to ask if she had seen or knew of their whereabouts. Jody told Davis that she did not know where they were. Ten to fifteen minutes later, Davis again telephoned Jody and asked her to go and find them. When Jody could not locate her daughter and granddaughter, she went to Stacey's and Davis's apartment.

¶ 3 Davis made several conflicting statements about the events that followed once Jody arrived, including a different version during his trial testimony. However, with the exception of his first statement where he claimed to have no memory of what had happened, Davis admitted in his other statements that he fatally stabbed Jody. Jody's body was discovered shortly after 9:00 a.m. when her daughter Stacey returned home. Stacey immediately called 911 and local police arrived to investigate.

¶ 4 Meanwhile, Davis had been involved in a single-car accident while driving Jody's van near the Salt Fork River Bridge. Davis was seriously injured after he was ejected from the van through the front windshield. Davis was transported to a local hospital for treatment. Because there was an odor of alcohol about him, Davis was placed under arrest and his blood alcohol level was tested and registered .09%. Later on, Davis was transported to a Witchita hospital for further care.

¶ 5 Detective Donald Bohon interviewed Davis around 5:49 p.m. that afternoon. In his first statement, Davis was able to recount his activities at the club the night before, but could not remember who drove him home. He recalled that Stacey and his daughter were not at home when he arrived and he remembered telephoning Jody. He could remember Jody being in the living room with him, but after that moment, he could not recall anything until he woke up in the field after the accident.

¶ 6 Two days later, Detectives Bohon and Bob Stieber interviewed Davis again. Initially, Davis repeated the story he had previously told Detective Bohon. As Stieber questioned Davis, his memory improved. He remembered Jody talking to him about religion and his commitment to Stacey. An angry Davis told Jody that there would be no commitment and the two argued. Davis claimed that Jody stood up while she continued her lecture and that he then stood up, got angry, accused her of being in his face and told her to “back up,” pushing her backwards. Davis claimed Jody grabbed a knife and cut him on his thumb. Davis then hit Jody on the chin (apparently causing the fracture to her jawbone) and tried to grab the knife, getting cut in the process. Davis said he got the knife from Jody and told her to get back, stabbing her in the stomach. He stated that he and Jody began to wrestle down the hallway and that he stabbed Jody in the leg. Once in the bedroom, Davis told Jody to stop and he put the knife down. Jody asked Davis to let her go to which he agreed, but then Jody ran towards the knife. He grabbed the knife first and stabbed Jody on the left side. She then told Davis that she could not breathe and Davis told her to lie down on the bed. Davis said he tried to wrap her up tightly in the bedspread so she would not bleed to death. He claimed he heard her stop breathing, but then fell asleep. When he awoke, he panicked and fled in Jody's van so he could think about what to do. Shortly thereafter, the crash occurred. When Stieber confronted him with physical evidence showing Jody was strangled/choked, Davis conceded that he may have choked her while they were wrestling. However, he adamantly denied having consensual or non-consensual sex with her.

¶ 7 Davis told his girlfriend, Stacey Sanford, three different versions of what happened that morning. At first, he told her that he believed her mother was an intruder and that he instinctively fought with her to protect his family home. Several months later, he told Stacey that her mother came to their apartment and that the two of them argued because Davis believed Jody was lying about her knowledge of Stacey's whereabouts. He claimed he pushed Jody and Jody went to the kitchen and retrieved a knife. Davis said that he got his thumb cut when he tried to take the knife from Jody, and that once he got the knife, he stabbed Jody once in the stomach. The argument continued and the two of them ended up in the bedroom where Jody said let's end this and Davis put the knife down. He claimed that she grabbed the knife as she walked towards the door and that he took it from her and stabbed her again.

¶ 8 Two to three months later after DNA tests showed that Davis' semen was found in Jody's vagina, Stacey confronted Davis and he told her a third version of what had happened. In this third version, he said that Jody came to their apartment upset about her husband's infidelity. He claimed that he tried to comfort her and they ended up having consensual intercourse. After their sexual encounter, Davis said he was lying on the floor in the front room while Jody was in the kitchen and that all of a sudden he was struck in the back of the head with some object. He did not elaborate on the details of the stabbing, indicating that the events unfolded from there.

¶ 9 At trial, Davis testified that Jody came to his apartment after she could not locate Stacey and talked to him about his need to commit to her. Davis claimed he responded by making a remark about Jody's husband's level of commitment and his rumored infidelity. He said that Jody became emotional and acknowledged that she knew about her husband's affair. Davis said he felt badly about his remark and got up and sat beside Jody and tried to comfort her. He claimed that Jody kissed him and that they ended up going back to the bedroom and having sex on the bedroom floor for fifteen to twenty minutes. Afterwards Davis got up and stumbled between the hallway and bedroom. He said that Jody was saying something about the time and he said that the sex was not worth his time and that he understood why Jody's husband was having an affair. He claimed that an angry Jody then hit him in the back of the head with a lotion dispenser, stunning him. As Jody walked by Davis, Davis got up and chased her down the hallway, tackling her and biting her ankle. Jody kicked Davis in the mouth and ran to the kitchen and grabbed a knife. Davis then ran to the living room and grabbed the Play Station II. Davis asked Jody “what the hell are you doing?” and hit her in the face. Davis said Jody “came back with a defensive position” and that he used the Play Station II as a shield. Now angrier, Davis hit Jody again and tossed the Play Station II into a nearby chair. He backed her down the hallway while she swung the knife wildly, cutting Davis on his arm. Davis went into the bathroom for a towel and Jody retreated to the bedroom. He said that when he exited the bathroom he saw Jody in the bedroom doorway and that he ran at her, grabbed her, pulled her down and hit her in the face two to three times. As they were fighting, Davis pushed Jody's head against the wall and struck her until she finally relinquished the knife. Jody retreated into the bedroom and asked Davis to let her go. Davis claimed he told Jody to go and put the knife on the nightstand. He said that when Jody walked by, she grabbed the knife, which angered him because he believed the fight was over. He then grabbed her shirt, pulled her towards him and put his arm around her neck squeezing as tightly as he could until she dropped the knife. He said that he grabbed the knife, that he was angry and that he stabbed Jody in the back. Jody then “swung back,” struck him in the groin and he fell to one knee. He claimed Jody continued to hit him and that he stabbed her several times as he tried to fend off her attack. He maintained that he never intended to kill her. Other facts will be discussed as they become relevant to the propositions of error raised for review.

¶ 10 In his first proposition of error, Davis claims the trial court abused its discretion in allowing the testimony of State's witnesses, William Parr and Russell Busby, in rebuttal because their identity had not been disclosed during pre-trial discovery. He maintains the Oklahoma Criminal Discovery Code FN3 (hereinafter “Code”) abrogated the common law “no notice” rule regarding rebuttal witnesses and requires disclosure and endorsement of all known or reasonably anticipated witnesses, including rebuttal witnesses. Accordingly, Davis maintains admission of Parr's and Busby's testimony was error.FN4 Because Davis objected to these witnesses on this basis, this claim has been preserved for review. FN3. 22 O.S.Supp.2002, § 2002. FN4. The record shows the State called five witnesses in rebuttal at the close of the defense's case-in-chief, three of which were endorsed as potential witnesses and are not the subject of this claim. Parr testified that he knew the victim for over ten years and that she had a peaceable character. Busby testified that he was qualified to conduct crime scene reconstruction and blood stain interpretation. Busby then gave his opinions about the crime scene, specifically contradicting certain portions of Davis' trial testimony.

¶ 11 Title 22 O.S.2002, § 2002(A)(1)(a) requires the State to disclose upon the defense's request “the names and addresses of witnesses which the State intends to call at trial, together with their relevant, written or recorded statement, if any, or if none, significant summaries of any oral statement.” Davis maintains that because the Code does not specifically exclude rebuttal witnesses from the State's compulsory disclosure duty and compels the defense to make known to the State the witnesses the defense intends to call at trial, § 2002(A)(1)(a) should be construed to require the State to include potential rebuttal witnesses in its endorsements and discovery materials to effectuate meaningful reciprocal discovery.

¶ 12 We have yet to consider the exact question presented, i.e., whether the Code has changed the common law rule and now requires the State to disclose the names and addresses of its rebuttal witnesses. To date, the Code's “intends to call at trial” language has been interpreted by this Court to include only those witnesses the State intends to call or reasonably anticipates calling in its case-in-chief to prove its case and to refute any known or anticipated defenses. In Short v. State, 1999 OK CR 15, 980 P.2d 1081, cert. denied, 528 U.S. 1085, 120 S.Ct. 811, 145 L.Ed.2d 683 (2000), the defendant sought to present a witness in his case-in-chief for whom no notice had been given under the Code. Short argued on appeal that the witness was a rebuttal witness for whom no notice was required as the witness was being offered to rebut testimony presented during the State's case-in-chief. Short, 1999 OK CR 15, ¶ 24, 980 P.2d at 1094. We found the witness was not a true rebuttal witness in the legal sense, noting every defense witness is a “rebuttal” witness to the State's case. Short, 1999 OK CR 15, ¶ 25, 980 P.2d at 1094. In so holding, we affirmed our position concerning notice of rebuttal witnesses, stating that “under usual trial proceedings, rebuttal is an opportunity for the State to present witnesses, for whom no notice is required, to rebut the defense case-in-chief.” Id. (emphasis added) Thus, the Short Court found no modification by the enactment of the Code of the long-standing rule that the State is not required to endorse rebuttal witnesses.

¶ 13 This same position was taken in Thornburg v. State, 1999 OK CR 32, ¶ 27, 985 P.2d 1234, 1245, cert. denied, 529 U.S. 1113, 120 S.Ct. 1970, 146 L.Ed.2d 800 (2000) (post-Code case) and Cheney v. State, 1995 OK CR 72, ¶ 70, 909 P.2d 74, 91 (a case tried after this Court's promulgation of almost identical discovery rules in Allen v. District Court of Washington County), when this Court held trial counsel was not ineffective in failing to object to rebuttal testimony based on lack of notice or surprise because the State is not required to endorse its rebuttal witnesses.

¶ 14 We take this opportunity to clarify this Court's position on the issue of the notice required under the Code. There is nothing in the Code that explicitly rejects or revokes the long-established rule that the State need not give notice of its rebuttal witnesses. That said, we emphasize this Court's condemnation of parties who are not forthcoming with their respective discovery obligations. The purpose of our reciprocal discovery code is to provide for the adequate exchange of information to facilitate informed pleas, to expedite trials, to minimize surprises/trial by ambush, to afford the parties the opportunity for effective cross-examination and to meet the requirements of due process. After all, the true purpose of a criminal trial is the ascertainment of the facts. We interpret the phrase “witnesses the State intends to call at trial” to mean a person or persons whom the State reasonably anticipates it is likely to call at trial, including those witnesses, especially experts, whose testimony is known or anticipated both prior to and after receipt of the defense's discovery materials.

¶ 15 No notice, however, is required for rebuttal witnesses. We recognize that a trial is not a scripted proceeding; rather, it is a process that ebbs and flows. Every lawyer and trial judge knows that during the trial process, things change and the best laid strategies and expectations may quickly become unsuitable: witnesses who have been interviewed vacillate or change their statements; events that did not loom large at preliminary hearing or throughout the pretrial proceedings may in reality become a focal point at trial. Thus, there must be some flexibility.

¶ 16 To ensure fairness, our trial courts are vested with the responsibility to determine whether proposed rebuttal witnesses are truly being offered to rebut evidence presented by the defense during its case-in-chief which could not be reasonably anticipated. If the so-called rebuttal witness is not a bona fide rebuttal witness, but rather a witness who could and should have been called in the State's case-in-chief and for whom no notice was given, the trial court should exclude the witness's testimony upon proper objection. If the rebuttal witness is offered to rebut specific evidence presented by the defense, the trial court should admit the testimony. We acknowledge there are conceivable circumstances where a failure to name a witness might be found to be a willful act designed to circumvent discovery rules. However, our existing rules as outlined above resolve the issue as well as the concerns raised by Davis of the nefarious prosecutor who deliberately withholds the names of witnesses the State intends to call at trial by labeling these witnesses as rebuttal witnesses in an attempt to hide significant parts of the State's case and to ambush the defense. Moreover, any unfairness that results from a lack of notice of a true rebuttal witness can usually be remedied by a continuance. We have held that if an unendorsed witness' testimony will require a defendant to produce additional evidence or other rebuttal witnesses, the defendant is entitled to a continuance of sufficient time to prepare to defend against the rebuttal testimony. Griffin v. State, 1971 OK CR 492, ¶ 12, 490 P.2d 1387, 1389. Here, Davis did not request any continuance.

¶ 17 We must now decide if the trial court properly admitted Parr's and Busby's testimony in rebuttal. The State called both Parr and Busby specifically to rebut claims Davis made during his trial testimony of which the State had no notice and in which Davis repudiated his prior statements and gave yet a sixth version of the events that happened between Jody and him. At trial, Davis testified that Jody started the altercation by hitting him in the head with the lotion dispenser after he made disparaging remarks about her sexual performance. He portrayed Jody as the aggressor throughout much of the fight to support his self-defense and mutual combat theories. Such testimony made Parr's testimony of Jody's peaceable character relevant and admissible. Likewise, Busby's testimony was relevant to refute Davis' claims made for the first time during his trial testimony concerning the manner and locations of the knife attack that were different than his pre-trial statements. Based on this record, we find that the trial court did not abuse its discretion in allowing the rebuttal testimony of Parr and Busby. Therefore, no relief is required.

¶ 18 In his second proposition of error, Davis contends upholding and allowing the continuation of the long-standing “no notice” rule in modern criminal discovery violates a capital defendant's Sixth, Eighth and Fourteenth Amendment rights. According to Davis, it is unfair to allow the State to label an expert witness as a rebuttal witness when the expert's testimony can be reasonably expected or anticipated from the defense's disclosure duties under the Code. We agree that the State should disclose witnesses whose testimony is known or anticipated after the State receives the defense's discovery materials. However, that is not the situation presented in this case.

¶ 19 Davis notes in several instances in his brief that the defense is not required under the Code to give notice of the defendant's own anticipated testimony if he chooses to testify. Here, the State had not been given any notice or indication prior to trial that Davis would testify.FN5 Nor did the defense reveal which, if any, of his prior statements he would advocate at trial or whether he would present a different version of the fateful events as he did. Under these circumstances, the State could not reasonably anticipate what rebuttal evidence would be relevant until Davis testified. FN5. The record shows the prosecutor did not engage Busby to conduct any crime scene reconstruction/investigation until the second day of trial when defense counsel announced during voir dire that Davis would testify.

¶ 20 Interestingly, Davis maintains the State knew or should have reasonably anticipated that it would call a crime scene reconstructionist because Davis had made statements about the location and circumstances of the knife attack from the beginning. Yet, he claims unfair surprise by this same witness whose necessity should have been so obvious to the prosecution. He maintains that the defense was unprepared to refute Busby's qualifications and conclusions due to the lack of notice of such a potential rebuttal witness. We find this assertion somewhat disingenuous. The defense was well aware of the State's right to present rebuttal evidence and the very real possibility the State would attempt to rebut Davis' trial testimony. Had Davis not taken the stand or changed his story, Busby's testimony would have been inadmissible in rebuttal. Davis has no legitimate constitutional claim that his rights were violated when it was he who elected to take the stand and offer yet another version of the events that attempted to account for the State's evidence, but that the State could ultimately discredit in rebuttal. Based on this record, we find that Davis' constitutional rights were not violated by the lack of notice of Busby's testimony.

¶ 21 Davis claims in his third proposition that his first-degree murder conviction must be reversed because the trial evidence was insufficient to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that he intended to kill Jody Sanford. Davis relies on his trial testimony to argue the evidence showed that the parties engaged in mutual combat, that it was Sanford who introduced the knife into the fight and that, at most, he is guilty of heat of passion manslaughter.

¶ 22 In reviewing sufficiency challenges, we review the direct and circumstantial evidence, crediting all inferences that could have been drawn in the State's favor, to determine if any rational trier of fact could have found the essential elements of the charged crime beyond a reasonable doubt. Black v. State, 2001 OK CR 5, ¶ 34, 21 P.3d 1047, 1062, cert. denied, 534 U.S. 1004, 122 S.Ct. 483, 151 L.Ed.2d 396 (2001); Spuehler v. State, 1985 OK CR 132, ¶ 7, 709 P.2d 202, 203–04. “Pieces of evidence must be viewed not in isolation but in conjunction, and we must affirm the conviction so long as, from the inferences reasonably drawn from the record as a whole, the jury might fairly have concluded the defendant was guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.” Matthews v. State, 2002 OK CR 16, ¶ 35, 45 P.3d 907, 919–20, cert. denied, 537 U.S. 1074, 123 S.Ct. 665, 154 L.Ed.2d 570 (2002).

¶ 23 To prove malice aforethought murder, the State must show the defendant acted with a deliberate intention to take the life of the victim without justification. Black, 2001 OK CR 5, ¶ 35, 21 P.3d at 1062. This intent may be formed instantly before committing the homicidal act. 21 O.S.2001, § 703. The law infers a design to effect death from the fact of killing unless the circumstances raise a reasonable doubt that such design existed. 21 O.S.2001, § 702. When direct evidence of a person's intent is lacking, jurors must rely on circumstantial evidence to ascertain the person's intent at the time of the homicidal act. Black, 2001 OK CR 5, ¶ 35, 21 P.3d at 1062.

¶ 24 The record shows Davis received jury instructions on the lesser-related offense of first-degree heat of passion manslaughter and the defenses of self-defense and voluntary intoxication. The jury heard the evidence, including Davis' trial testimony, and rejected his claim that he was engaged in mutual combat and that he stabbed Sanford in a heat of passion. The jury's verdict is supported by the record. All of Davis' accounts of his encounter with Sanford that early morning were discredited in some form or fashion. At trial, Davis repudiated his five statements made prior to trial, claiming he had lied to spare/protect the Sanford family as well as his own family. He testified his trial version was the truth. However, Russell Busby, the crime scene reconstructionist, testified that the blood patterns in the back bedroom were inconsistent with Davis' trial version of the events that Sanford was standing in the back bedroom while she was being stabbed. The jury was free to consider the fact that Davis changed his story to fit the facts as he learned them in evaluating his credibility. The fact that Davis' statements and his trial testimony were inconsistent with each other and with the physical evidence was a relevant consideration in determining his truthfulness and ultimately his guilt. See McElmurry v. State, 2002 OK CR 40, ¶ 42, 60 P.3d 4, 19.

¶ 25 The uncontroverted evidence showed Davis called Sanford in the early morning hours of November 4th looking for Stacey and his daughter. Despite being told they were not there, he called again within fifteen minutes and thereafter Sanford left her home and ended up at Davis' apartment. Later that morning, Sanford was found dead, half-naked, bruised and stabbed multiple times. Around the same time, Davis was involved in a serious accident that occurred as he was driving Sanford's van some nine miles away from his apartment. The jury could easily have concluded the events unfolded more like Davis described in his second statement in which Davis admitted getting mad at Sanford after she lectured him on commitment and church. He started the fight with Sanford because he felt she was in his “face” and that she was not being truthful about Stacey's whereabouts. This statement provided the plausible motive in this case. The jury had legitimate reasons to disbelieve Davis' claims that he never intended to kill Sanford in light of the severity of her stab wounds and other injuries and his inconsistent stories about the events. Based on this record, we find the evidence was sufficient to sustain the verdict.

¶ 26 In his fourth proposition, Davis claims the trial court committed reversible error when it refused the uniform instructions he requested on the definition of circumstantial evidence and the need for circumstantial evidence to exclude reasonable theories of innocence. The record shows these instructions were not discussed during the instruction conference. Rather, defense counsel requested them just before the jury retired to deliberate and the trial court denied the request.

¶ 27 “An instruction on circumstantial evidence is only required when the State's evidence consists of entirely circumstantial evidence.” Wade v. State, 1992 OK CR 2, ¶ 19, 825 P.2d 1357, 1362. When the State relies on both direct and circumstantial evidence for its proof, the jury need not be specially instructed of circumstantial proof. Roubideaux v. State, 1985 OK CR 105, ¶ 24, 707 P.2d 35, 39. Here, the State's case was not entirely circumstantial as there was direct evidence Davis killed Sanford. Simply because one of the elements is proved by circumstantial evidence does not make the case an entirely circumstantial case. A review of the record shows the instructions given correctly stated the applicable law and included all of Davis' theories of defense. Accordingly, we find the trial court did not abuse its discretion in denying Davis' late request for these circumstantial evidence instructions.

¶ 28 In his fifth proposition of error, Davis claims the trial court abused its discretion when it prohibited him from questioning Tom Sanford, Stacey Sanford and Raymond Pollard, about Tom Sanford's alleged extra-marital affair, arguing such evidence was relevant to Jody Sanford's state of mind that fateful morning and would have supported his claim that the sexual encounter between them was consensual. He maintains the trial court's ruling denied him his constitutional right to confront witnesses against him and his right to compulsory process.

¶ 29 Before calling Tom Sanford to testify, the State moved in limine to prohibit the defense from questioning him about whether or not he had engaged in an extra-marital affair. The State argued that Tom Sanford's participation in any extra-marital affair was not relevant to the case. The defense argued it had the right to address the subject since the State had presented evidence of it through Stacey Sanford FN6 and such evidence was relevant to Jody Sanford's state of mind to show whether she would have given consent to have sex with Davis. The State responded that it had not offered evidence that an affair had actually taken place, only that Davis had told Stacey that her mother was upset about an affair. The trial court ruled that evidence of an actual affair was not relevant, but even if it were, the prejudicial effect outweighed any probative value it might have had. FN6. Stacey had earlier testified about Davis' third statement to her in which he admitted, after being confronted with DNA evidence, to having sex with her mother before he killed her. Davis told Stacey that her mother was upset about her husband cheating on her and that Davis' attempts to comfort her led to consensual sexual intercourse.

¶ 30 It is well established that the scope of cross-examination and the admission of evidence lie in the sound discretion of the trial court, whose rulings will not be disturbed unless that discretion is clearly abused, resulting in manifest prejudice to the accused. Williams v. State, 2001 OK CR 9, ¶ 94, 22 P.3d 702, 724, cert. denied, 534 U.S. 1092, 122 S.Ct. 836, 151 L.Ed.2d 716 (2002); Reeves v. State, 1991 OK CR 101, ¶ 30, 818 P.2d 495, 501. There is no such abuse of discretion in the present case. Whether Jody Sanford had heard a rumor of an affair and whether she believed it as true would not have been rendered more or less probable by the admission of evidence indicating whether or not Tom Sanford had actually engaged in an extra-marital affair. The issue was Jody Sanford's existing state-of-mind to which Davis testified. Davis repeated his claim under oath that Sanford was upset about her husband's alleged affair in support of his claim that they had consensual sex. Therefore, evidence from Sanford that he actually engaged in an affair was not relevant to the issues in controversy.

¶ 31 The same is true for Raymond Pollard and Stacey Sanford. The defense sought to question Pollard in its case-in-chief about seeing Tom Sanford in the company of a woman, not his wife. Such evidence was irrelevant to the issue of consent or Sanford's state of mind at the time of her death. Likewise, the defense wanted to ask Stacey if she had heard the rumors Davis had heard about her father being involved in an extra-marital affair and whether she knew if her mother had heard or knew of the rumors. Defense counsel did not indicate that he had any knowledge to support an offer of proof that Stacey knew her mother was aware of any alleged affair and was affected by it in the days before her death. Based on this record, it cannot be said the trial court abused its discretion in limiting defense counsel's questioning of these witnesses. Accordingly, we find this claim has no merit.

¶ 32 In his sixth proposition of error, Davis contends the introduction of his statements to Detective Bohon and Detective Stieber violated his Fifth Amendment rights because the State failed to prove by a preponderance of the evidence that he knowingly and voluntarily waived his right to remain silent/privilege against self-incrimination. He also claims, as he did below, that his statement was not voluntary within the meaning of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment due to the coercive police tactics utilized in obtaining the statement from a person in his condition.

¶ 33 Voluntariness of a confession is judged from the totality of the circumstances, including the characteristics of the accused and the details of the interrogation. Van White v. State, 1999 OK CR 10, ¶ 45, 990 P.2d 253, 267; Lewis v. State, 1998 OK CR 24, ¶ 34, 970 P.2d 1158, 1170, cert. denied, 528 U.S. 892, 120 S.Ct. 218, 145 L.Ed.2d 183 (1999). See also Moran v. Burbine, 475 U.S. 412, 421, 106 S.Ct. 1135, 1141, 89 L.Ed.2d 410, 421 (1986). For a waiver of rights to be effective, the State must show by a preponderance of the evidence that the waiver was the product of a free and deliberate choice rather than intimidation, coercion, or deception and that the waiver was made with a full awareness both of the nature of the right being abandoned and the consequences of the decision to abandon it. Lewis, 1998 OK CR 24, ¶ 34, 970 P.2d 1158, 1170; Smith v. State, 1996 OK CR 50, ¶ 16, 932 P.2d 521, 529, cert. denied, 521 U.S. 1124, 117 S.Ct. 2522, 138 L.Ed.2d 1023 (1997).

¶ 34 The trial court held a Jackson v. DennoFN7 hearing to consider Davis' objection that his waiver of rights and subsequent statement were involuntary. It found, after considering the totality of the circumstances, that the question of the voluntariness of Davis' waiver was a fact question to be resolved by the jury and that a finding of involuntariness as a matter of law was not justified. This Court will not reverse a trial court's ruling where the trial court's decision to admit a statement is supported by competent evidence of the voluntary nature of the statement. Bryan v. State, 1997 OK CR 15, ¶ 17, 935 P.2d 338, 352, cert. denied, 522 U.S. 957, 118 S.Ct. 383, 139 L.Ed.2d 299 (1997). FN7. Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368, 84 S.Ct. 1774, 12 L.Ed.2d 908 (1964) established a defendant's right to an in camera hearing on the voluntariness of his confession.

¶ 35 The evidence supports the trial court's finding that Davis' waiver of rights and subsequent statements were voluntary and therefore admissible. At the Jackson v. Denno hearing, the State presented the testimony of both Detectives Bohon and Stieber. The State also provided the court with transcripts of both interviews. Detective Bohon testified that before he interviewed Davis the first time on November 4th, he consulted hospital medical staff about what, if any, medications Davis had been or was taking and the best time to speak with him to ensure Davis would be coherent and free from the influence of any medications. Bohon testified that prior to any questioning, he read Davis his Miranda warning from the standard printed sheet, including the two waiver questions. Bohon said that Davis responded affirmatively when asked if he understood his rights and appeared to do so. Davis then agreed to tell Bohon what he could remember. Bohon testified that during the interview Davis was conscious and did not appear to be under the influence of any type of drug or alcohol. His speech was not slurred and he gave understandable and reasonable responses to the questions posed. Furthermore, Davis appeared oriented to time and place. Bohon did not threaten, force, pressure or promise Davis anything in order to get him to make a statement. Bohon characterized the conversation as “cordial” and “pretty open.” A review of the transcript confirms Bohon's testimony.

¶ 36 Detectives Bohon and Stieber followed the same protocol when they interviewed Davis on November 6th. Bohon again conferred with hospital medical staff about Davis' medication regimen and its effects on him so Davis would be lucid and clear-headed during anticipated questioning. Prior to any questioning, Stieber read to Davis the Miranda warning from his Miranda card and asked Davis if he understood his rights and wanted to talk with him. Davis said that he understood his rights and that he would answer what he could. At no time during the interview did Davis indicate that he wanted to terminate the interview or consult a lawyer. Davis appeared to understand all questions asked and gave appropriate responses to the questions posed. The specificity of detail Davis was able to provide and the back and forth nature of the interview demonstrated that he was fully alert and comprehended what others said to him, thereby supplying strong evidence that he understood his rights as presented to him as well.

¶ 37 In addition, a review of both interviews shows that Davis' statements were not extracted or coerced by the exertion of improper influence. This is especially true of Davis' first statement since he did not confess and claimed he had no memory of what had happened. The record does reveal that during the second interview in which Davis ultimately confessed, Stieber did use phrases like “cold blooded killer” and “cold blooded bastard” to spur Davis to provide details of the events that culminated in Sanford's death. The comments complained of were not coercive in nature; the detectives neither threatened Davis nor implied promises of benefits or leniency. Rather, the detectives explained to Davis that the evidence showed that he was responsible for Sanford's death, leaving them to conclude that he either planned it and carried it out making him a cold blooded killer or that some unplanned fight erupted and Sanford was stabbed and killed. Only Davis could provide the answer and they encouraged him to do so. After reviewing the totality of the circumstances, we find the trial court did not err in its ruling. Accordingly, no relief is required.

¶ 38 In his seventh proposition of error, Davis contends the trial evidence was insufficient to support the jury's finding that Sanford's murder was especially heinous, atrocious or cruel. Acknowledging Sanford's injuries, he maintains that these wounds were inflicted either entirely or in large measure under circumstances of mutual combat and that the aggravating circumstance only applies to those acts which occur after the intent to kill is formed. Davis submits that because we cannot know at what moment the intent to kill was formed under the evidence presented, we must find the evidence of this aggravating circumstance insufficient. We disagree.

¶ 39 This Court upholds a jury's finding of this aggravating circumstance when it is supported by proof of conscious serious physical abuse or torture prior to death; evidence that a victim was conscious and aware of the attack supports a finding of torture. Black, 2001 OK CR 5, ¶ 79, 21 P.3d at 1074. As discussed in Proposition 3, supra, the evidence was sufficient for a rational jury to conclude that Davis intentionally killed Sanford, his statements notwithstanding. The jury rejected Davis' self defense and mutual combat theories. There was evidence of a struggle during which Davis stabbed Sanford six times penetrating vital organs. She later died from the blood loss associated with these wounds. Davis also beat Sanford, broke her jaw and attempted to choke her as evidenced by the petechiae in her eyes. Sanford was found naked from the waist down and her shirt and bra were pushed up over her breasts. She had a bite mark on her ankle and a possible bite mark on her thigh. Davis' sperm was found in her vagina and the jury concluded Davis raped Sanford at some point during the attack. In his many statements, Davis never claimed Sanford was unconscious until sometime after she had been stabbed. Evidence of such an assault and rape on a 52–year–old woman standing 4'11? by a young man standing 5'10? weighing 245 lbs. accompanied by Sanford's injuries would allow a rational jury to conclude that Davis intended to kill Sanford when he stabbed her six times and that he inflicted trauma causing conscious serious physical abuse or torture prior to Sanford's death. Therefore, we find the evidence, when viewed in the light most favorable to the State, was sufficient to find beyond a reasonable doubt that Sanford's murder was especially heinous, atrocious or cruel. Black, 2001 OK CR 5, ¶ 79, 21 P.3d at 1074.

¶ 40 In his eighth proposition of error, Davis claims he was denied a fair trial by the admission of prejudicial, irrelevant and privileged marital communications consisting of statements both oral and written he made to Stacey Sanford while awaiting trial. The record shows that Davis did not object to much of the evidence about which he now complains and that the trial court overruled the objections he did make, finding Davis had not proved the existence of a common law marriage.

¶ 41 The marital privilege, set forth at 12 O.S.2001, § 2504, applies equally to common law and ceremonial marriages. Blake v. State, 1988 OK CR 272, ¶ 4, 765 P.2d 1224, 1225 (quoting K. McKinney, Privileges, 32 Okla.L.Rev. 307, 326 (1979)). However, before an accused can take advantage of the marital privilege to exclude evidence, he or she must first prove, by clear and convincing evidence, the existence of a valid marriage. Blake, 1988 OK CR 272, ¶ 4, 765 P.2d at 1225. To establish a valid common law marriage, there must be evidence of an actual mutual agreement between the spouses to be husband and wife, a permanent relationship, an exclusive relationship—proved by cohabitation as man and wife, and the parties to the marriage must hold themselves out publicly as man and wife. Id.

¶ 42 Although Stacey Sanford and Davis lived and had children together, Stacey Sanford described her relationship with Davis as boyfriend and girlfriend. She testified that it was Davis who told her parents she was pregnant with their second child because she was afraid her parents would be angry with her for getting pregnant again without her and Davis being married. She further testified that Davis had talked with her mother about marrying her. In his November 6th interview with detectives, Davis told them Sanford came to his apartment and started lecturing him about the need for Davis and Stacey to commit. He and Stacey were having some problems at that time, but Davis said they were working things out and were “going to get married and all of that.” At trial, Davis described Stacey as his fiancé and mother of his children. When asked if the two of them had held each other out as husband and wife, Davis stated “[j]ust as—as far as engagement, that's about it, common law married.” Later in his testimony, Davis testified that he and Stacey were having problems and that they had been engaged in the past, but were not at the time of Sanford's death. The foregoing testimony presented at trial was insufficient to establish the elements of a valid common law marriage by clear and convincing evidence. Accordingly, we find the trial court did not err in allowing evidence of Davis' statements to Stacey Stanford at trial over Davis' marital privilege objection.

¶ 43 In addition, Davis' claim that the evidence was irrelevant and unduly prejudicial is without merit. Davis' pre-trial statements explaining the events of that morning to Stacey and his letters to her urging her to stand by him were unquestionably relevant to the issues in dispute and to Davis' credibility. Such evidence was not unfairly prejudicial. Accordingly, we find the trial court did not abuse its discretion in admitting the complained-of evidence. Williams, 2001 OK CR 9, ¶ 94, 22 P.3d at 724.

¶ 44 In his final proposition of error, Davis claims his death sentence should be vacated or modified because the aggravating circumstances were not charged in an information or indictment, were not subjected to adversarial testing at a preliminary hearing, and were therefore not determined to probably exist by a neutral and detached magistrate. Thus, Davis claims the District Court never acquired jurisdiction over the aggravating circumstances.

¶ 45 Davis relies upon the United States Supreme Court's holdings in Ring v. Arizona, 536 U.S. 584, 122 S.Ct. 2428, 153 L.Ed.2d 556 (2002) and Apprendi v. New Jersey, 530 U.S. 466, 120 S.Ct. 2348, 147 L.Ed.2d 435 (2000). Under these cases and the Supreme Court's interpretation of them in Sattazahn v. Pennsylvania, 537 U.S. 101, 123 S.Ct. 732, 154 L.Ed.2d 588 (2003), Davis maintains aggravating circumstances “operate as the functional equivalent of an element of a greater offense.” See Ring, 536 U.S. at 609, 122 S.Ct. at 2443, quoting from Apprendi, 530 U.S. at 494, n. 19, 120 S.Ct. 2348. Thus, Davis contends, aggravating circumstances-as the functional equivalent of an element of a greater offense-must be charged in an indictment or information and then be presented and established at a preliminary hearing for a death sentence to be constitutionally sound.